Some Jews

A Jewish-Anarchist Refutation of the Hammer and Sickle

During the Russian Revolution, the crossed hammer and sickle became a Communist symbol, representing the union of the industrial proletariat and the agricultural peasant. Despite this relatively innocent origin, the symbol has come to represent the totalitarian Communist state... and, we argue, anti-Semitism. Stalin’s Terror, the gulags, the executions of those who fought alongside the Bolsheviks in the revolution but did not share their exact political vision, the USSR’s active cooperation with Nazi Germany--the USSR was, arguably, not ethically superior than any given fascist state. Nevertheless, one hundred years later, the Communist flag continues to fly at Leftist and anti-fascist demonstrations across the world as if this history did not matter. This is troubling to those of us for whom the Bolshevik betrayal remains fresh. Individual Communists have long fought against fascism, many of them in good faith... but, writ large, anarchists and Jews have never had reason to trust the Communists at their backs.

The Bolshevik Party persecuted many different ethnic, cultural, and political groups; here, we will mainly discuss its warfare against Soviet Jews. Although Lenin publicly denounced the frequent pogroms in pre-revolutionary Russia, they continued throughout the revolutionary and war years. Yet even within the ranks of the Bolshevik army, anti-Jewish violence was rampant as the “[h]atred of the Hebrew was of course common [...] it was not eradicated even among the Red soldiers. They, too, have assaulted, robbed, and outraged Jews.” (Goldman 104) Many people of that time noted that there were “two kinds of pogroms: the loud, violent ones, and the silent ones.” (ibid 206) The latter is what the Bolsheviks excelled at. The Bolsheviks made a tactical, not ethical, choice to move away from the open anti-Semitism of the Tsarist era and instead waged a covert war to uproot and destroy Jewishness in the Soviet Union. The anti-Semitism propagated by the Bolsheviks was not dissimilar to the anti-Semitism that many Jews still encounter on the Left. Today, it is often masked and veiled by the words “bankers,” “the media,” “neocons,” “Westerners”... and even “Bolsheviks.” This is due to the remaining influence of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the false document used by Tsarist loyalists to blame Russian Jews for fomenting political disruption, and, later, the Revolution. The layered history of anti-Semitism turns back upon itself.

During the year in which Lenin publicly denounced the traditional Russian pogroms, 1919, he also wrote a directive of the Communist Party known as “The Policies on the Ukraine,” stating in part that “Jews and city dwellers on the Ukraine must be taken by hedgehog-skin gauntlets, sent to fight on front lines and should never be allowed on any administrative positions (except a negligible percentage, in exceptional cases, and under [our] class control).” (Kusikov, 207) Stalin, too, shared this anti-Semitic stance as early as 1907, when Stalin differentiated between the “Jewish faction” and the “true Russian faction” within Bolshevism. Even in this alleged Communist utopia, Jews were to be forever outliers, never fully to be allowed into Russian society. These Communists shared a goal with the monarchists they opposed--the death of Jewish culture. Even when they did not intend physical death for Jews, we should always read assimilation as a violent hegemonic social force bent on the destruction of a culture. This is not a new analysis. From a Soviet Jewish response to the 1952 murder of thirteen Jews in the USSR: “We who have signed this appeal firmly declare that we will never take the painful and shameful path of national self-destruction: we declare that forcible assimilation is genocide pure and simple.” (Poets, 30)

On a 1920-22 visit to a shtetl in post-revolutionary Russia, Jewish anarchist Alexander Berkman spoke with a peasant Jew who expressed this sentiment:

They [Bolsheviks] also hate the Jew. We are always the victims. Under the Communists we have no violent mob pogroms; at least I have not heard of any. But we have the ‘quiet pogroms,’ the systematic destruction of all that is dearest to us — of our traditions, customs, and culture. They are killing us as a nation. I don’t know but [which] is the worst pogrom. (Berkman 195)

Just as today, the Soviet government preferred to use codewords to signal its anti-Semitism: “petty bourgeois,” “banker,” or “Zionist.” Terms such as “internationalism” (despite the internationalist roots of Communism!) and “Zionism” were seen as signals of Jewish loyalty to other countries, and marked Jews as “untrustworthy.” Jews who maintained a feeling of solidarity with other Jews living abroad were seen as enemies of the state, as a fifth column. “On September 21, 1948, Ehrenberg writing in Pravda [official newspaper of the Communist Party] delivered the opening blows of the new [anti-Jewish] campaign. He warned Soviet Jews that their identifying with Jews in other countries would prove their disloyalty to the Soviet Union.” (Poets 9)

Anarchists of the time, who were often but not always Jewish, were also accused of anti-Soviet activities; many were imprisoned, exiled, or executed. Trotsky’s campaign against anarchists used words such as “bandit” or “dissident elements” to demonize them. These accusations resulted in scores of executions and the imprisonment of thousands; others were exiled to camps in Siberia, and few of these were ever heard from again.

European Jewry was quite diverse, and, within the Soviet borders, Jews took part in many aspects of Soviet life, from engaging in various political movements to continuing to practice traditional Jewish community life. At the time of the revolution, Jews had been stateless and in exile for nearly 2,000 years, and made homes wherever necessary. Anne Frank wrote in her diary a then-common view of Jewishness: “We can never become just Netherlanders, or just English, or just representatives of any other country for that matter, we will always remain Jews...” Around the same time Frank wrote this, the famous Yiddish Bolshevik poet, Isaac Feffer, who was eventually tortured and murdered by Stalin, made a similar statement:

There are not two Jewish peoples. The Jewish nation is one. Just as a heart cannot be cut up and divided, similarly one cannot split up the Jewish people into Polish Jews and Russian Jews. Everywhere we are and shall remain one entity. (Poets 7)

However, Jewishness is not monolithic. Jews have been spread across the earth, and adapted accordingly. Jews have different histories, stories, languages, skin colors, and experiences, but often share a similar experience of anti-Semitism. When Feffer speaks of a “nation,” he is not calling for nationalism, but referring to a common ethnic and cultural tradition.

Having already dismantled the Jewish Bund, a group that fought alongside the Bolsheviks during the revolution, Lenin continued the destruction of Jewish cultural life. (Slezkine 392) The Bolsheviks were opposed to any form of religion, seeing the dismantling of all religious structures as necessary for utopian hegemony. Synagogues were shut down and rabbis were put out of work; any priest, rabbi, or other religious leader who kept preaching, teaching, or practicing were sent to the gulag, where many people died. Whatever one’s view of religion, this is deeply terrible. For Jews, this forced secularist hegemony and repression was particularly painful. Jewish life, both, secular and religious, is deeply tied to its religious stories and traditions; even the Yiddish language, which was mostly spoken by European Jews, is deeply influenced by Judaism. (After the Revolution, Yiddish was momentarily recognized as a language, but was “cleansed” by the Bolsheviks of any reference to Judaism or to ancient Hebrew-Aramaic. Hebrew, meanwhile, was banned.) (Weinstein 87)

Amidst this repression, the All-Russian Zionist Congress was broken up by the Bolsheviks in April 1920; its leadership and ranks included many self-hating Jews. The Yevsektsii was the mainly Jewish section of the Bolshevik party that dealt with issues of dismantling Jewishness.[1] After betraying their fellow Jews by co-operating with the state’s plans for Jewish cultural extinction, this section was disbanded in 1929. Many of its leading members were sent to the gulag, or exiled, or murdered in the Great Purge (1936-1938) because of their Jewishness. Collaboration with the state saves no one in the end.

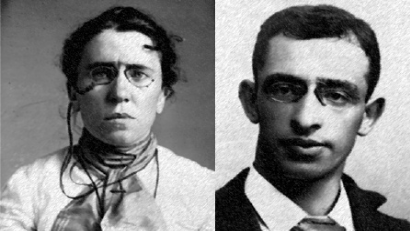

Nearly as soon as the Bolsheviks took power, they began to execute anarchists and Socialist Revolutionaries, most of whom had fought alongside the Bolsheviks in the Revolution. They also purged elements of their own party deemed “anti-Soviet” or “counter-revolutionary.” This state repression was well documented by the Soviet government, but here we have chosen to use journals and letters of those affected. Lithuanian-American Jewish anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman describe the Bolshevik betrayal:

The systematic man-hunt of anarchists [...] with the result that every prison and jail in Soviet Russia filed [sic] with our comrades, fully coincided in time and spirit with Lenin’s speech at the Tenth Congress of the Russian Communist Party. On that occasion Lenin announced that the most merciless war must be declared against what he termed “the petty bourgeois anarchist elements” which, according to him, are developing even within the Communist Party [...] On the very day that Lenin made the above statement, numbers of anarchists were arrested all over the country, without the least cause or explanation. The conditions of their imprisonment are exceptionally vile and brutal. (Boni, 253)

Another letter in the same collection gives us a first-hand account:

In 1919 I was arrested at home, in the daytime by order of the Moscow Tcheka.[2] Kept in a cellar of the Moscow Tcheka (called “the ship”) where 70 prisoners were sleeping on boards or on the floor; among them were menshevists, left socialist-revolutionists, bandits [anarchists], peasants, officers, and the former Minister of War, Polivanoff. Each night men were taken out to be shot---mostly bandits... A youth of about 17, whose name I have forgotten, was thus carried away to his doom in my presence. (Boni, 53)

Finally, from a 1924 letter published in the same collection, collectively written against the murder of prisoners who were protesting prison conditions:

The troops of the “G.P.U.” and the keepers shot at socialist and anarchist prisoners who were peacefully promenading. The shooting was done in volleys, wholesale, shots being fired at those who fell to the ground as well as at those who were carrying out the wounded. We know that the conduct of the “G.P.U.” towards the socialists and anarchists imprisoned on the Solovetz Island is an inevitable result of the entire policy of terror applied by the Soviet Government to socialists and anarchists. And we therefore have no doubts that new sacrifices are in store for us. (Boni, 207)

During the Revolution, the Bolsheviks tactically used the language of solidarity and political diversity to attract these allies they later murdered. Even in the Revolution, however, anarchists were being indirectly murdered by Bolsheviks, who often used anarchists for the hardest and most dangerous work; later, these once-allies were often criminalized as “bandits.” From an anonymous Jewish anarchist:

As long as they were revolutionary we cooperated with them [...] The fact is, we Anarchists did some of the most responsible and dangerous work all through the Revolution. In Kronstadt, on the Black Sea, in the Ural and Siberia, everywhere we gave a good account of ourselves. But as soon as the Communists gained power, they began eliminating all the other revolutionary elements, and now we are entirely outlawed. Yes, the Bolsheviki, those arch-revolutionists, have outlawed us. (Berkman 156)

The disillusionment of anarchists and Socialist Revolutionaries (SR), who had fought alongside the Bolsheviks, seemed endless. Anarchists and SRs all across Soviet lands bore witness to this treachery and betrayal. The people of Kronstadt, a naval fortress on Kulin Island, experienced arguable the greatest Bolshevik betrayal of all, next to the Bolshevik betrayal of anarchists fighting fascists in Spain. In March 1921, an anti-Bolshevik rebellion erupted in Kronstadt. Stationed in Kronstadt were two war ships, mainly consisting of anarchists and SR sailors. From those ships the rebellion spread into the town of Kronstadt. In response, to violent repression in Petrograd, 16,000 people came to consensus and wrote up a list of 15 demands on March 1 1921:

-

Immediate new elections to the Soviets; the present Soviets no longer express the wishes of the workers and peasants. The new elections should be held by secret ballot, and should be preceded by free electoral propaganda for all workers and peasants before the elections.

-

Freedom of speech and of the press for workers and peasants, for the Anarchists, and for the Left Socialist parties.

-

The right of assembly, and freedom for trade union and peasant associations.

-

The organisation, at the latest on 10 March 1921, of a Conference of non-Party workers, soldiers and sailors of Petrograd, Kronstadt and the Petrograd District.

-

The liberation of all political prisoners of the Socialist parties, and of all imprisoned workers and peasants, soldiers and sailors belonging to working class and peasant organisations.

-

The election of a commission to look into the dossiers of all those detained in prisons and concentration camps.

-

The abolition of all political sections in the armed forces; no political party should have privileges for the propagation of its ideas, or receive State subsidies to this end. In place of the political section, various cultural groups should be set up, deriving resources from the State.

-

The immediate abolition of the militia detachments set up between towns and countryside.

-

The equalisation of rations for all workers, except those engaged in dangerous or unhealthy jobs.

-

The abolition of Party combat detachments in all military groups; the abolition of Party guards in factories and enterprises. If guards are required, they should be nominated, taking into account the views of he workers.

-

The granting to the peasants of freedom of action on their own soil, and of the right to own cattle, provided they look after them themselves and do not employ hired labour.

-

We request that all military units and officer trainee groups associate themselves with this resolution.

-

We demand that the Press give proper publicity to this resolution.

-

We demand the institution of mobile workers’ control groups.

-

We demand that handicraft production be authorised, provided it does not utilise wage labour.

Unfortunately, within 12 days the Kronstadt Rebellion was crushed, culminating in thousands of rebels and civilians dead, thousands more purged afterward, and thousands captured and condemned to hard labour (Kronstadt, website).

In response to these vicious and murderous betrayals, anarchists and Jews sometimes took matters into their own hands, as in the case of one Jewish woman who attempted to kill Lenin, saying only:

“My name is Fanya Kaplan. Today I shot Lenin. I did it on my own. I will not say from whom I obtained my revolver. I will give no details. I had resolved to kill Lenin long ago. I consider him a traitor to the Revolution.”

Although Lenin didn’t die that night, August 30th 1918, he did eventually die from complications resulting from his wounds six years later. Kaplan, meanwhile, was caught, tortured, interrogated and murdered by the Bolshevik Tcheka. This sort of treatment was not reserved for political dissidents and attempted assassins, but was used against anyone whom the Bolsheviks wanted out of the picture. The families of those singled out as enemies of the state were commonly also subject to exile, social isolation, imprisonment, or labor camps. Anarchists found their newspapers and social centers under attack; as Lenin said, boldfaced: “There can be no free speech in a revolutionary period.” (quoted in Drinnon, Rebel 235.)

This suffering was shared by the very peasantry for whom the Bolshevik flag supposedly waved. In his investigatory journey across Soviet lands, Berkman interviewed many peasant Jews about their experience with the Bolsheviks. He described their common expressions as the look of the hunted, with dread in their eyes. One hesitantly told him, “Seeing you are not a Communist I can tell you how we suffer [...] The peasants are worse off now than before; they live in constant dread lest a Communist come and take away their last loaf.” (Berkman 89)

This violence against Jews during and after the Tsar inspired many Jews to take up arms and organize defense leagues, as in the case of Odessa, where there was already a lively underworld of anarchist gangsters. During the chaotic years following the Revolution there were many armies fighting for territory--some loyal to the Tsar, some Ukrainian nationalists, and some who fought for autonomy. One successful militia of the latter variety was composed of Jewish anarchist gangsters who waged war against the police of Odessa and invading armies. It was organized by Mishka Yaponchik, a well-known Jewish Robin Hood-esque figure. Odessa was then a hub of Jewish life and therefore the target of pogroms. Having experienced pogroms himself, Yaponchik took part in armed Jewish defense groups that fought off would-be murderers. In a particularly colorful incident, he killed a police chief by pretending to be a shoeshiner: after having shined the police chief ’s shoes, he detonated a bomb inside of a shoebox. Yaponchik miraculously escaped unscathed, but was later caught; his sentence of death was eventually commuted to twelve years hard labour.

Later, during the Revolution, Yaponchik was again caught--this time by Anton Ivanovitch Denikin, an open anti-Semite responsible for numerous pogroms and thousands of Jewish lives: Yaponchik’s future seemed dark... for less than thirty minutes. His comrades immediately showed up to rescue him: a procession of Jewish gangsters on horseback and in carriages, all of them carrying grenades.

During the Revolution Yaponchik’s militia momentarily joined with the Bolsheviks. By doing so they were able to fight off both the White Army and the Ukrainian nationalist army. They were also successful in freeing prisoners from the Odessa prison and, for a short time, Odessa became an anarchist haven. Despite these initial victories, Yaponchik was eventually ambushed by his supposed Bolshevik “comrades” and murdered on July 29th 1919 by the Tcheka. His elusive intentions had been Yaponchik’s best tool when dealing with the Bolsheviks, as described in the memoir of future rightwing Zionist[3] and Haganah member, Abraham T’homi:

Exciting news! The Whites were fleeing, and the Mayor of Odessa was negotiating the surrender of the city to the Bolsheviks.

We were relieved, but our joy was somewhat marred. It wasn’t our self-defense group that prevented the bloodbath, it was Mishka Yaponchik who did it. Mishka Yaponchikó the anarchist, the naletchik, the boss of the Moldavanka underworld. And we didn’t even know whether he defied the Whites because he wanted to defend the Jews of Odessa, or because he was in league with the Bolsheviks. (Tanny 16)

While Yaponchik’s army of Jewish anarchists were temporarily legitimated under the Bolsheviks, we can surmise based on his previous experience and conversations with comrades that his intentions were not based in sympathy with the Bolsheviks, but rather in his Jewishness and his desire to protect Jews from Gentile violence. His life was commemorated in the lyrics of this folksong:

“Mishenka [...] robbed the rich and gave to the poor. He was a good man. But bitter was his end. Mishenka had “‘rolled’” into the hands of the Cheka, and he “‘never came back.’” (Tanny 16)

Holodomor

Holodomor is a Ukrainian word meaning “to die of starvation,” and refers to a series of manmade Bolshevik famines during the 1920s and 30s in the Ukraine. Though they were created by the Bolshevik government to wipe out specific populations, such as kulaks[4] and Jews, the Soviets were not opposed to seeing all Ukrainians die, which would clear the land for Russian immigrants. The devastation swept across towns, villages, and farms; Bolshevik soldiers put up barricades to keep people from seeking food or help. The Jewish novelist and journalist Vasily Grossman documented his experience in his semi-autobiographical fiction, which was censored by the Soviet government for decades, Forever Flowing:

And here, under the government of workers and peasants, not even one kernel of grain was given them. There were blockades along all the highways, where militia, NKVD men, troops were stationed; the starving people were not to be allowed into the cities. Guards surrounded all the railroad stations. There were guards at even the tiniest of whistle stops. No bread for you, breadwinners! ... And the peasant children in the villages got not one gram. (Grossman 155)

Before they had completely lost their strength, the peasants went on foot across country to the railroad. Not to the stations where the guards kept them away, but to the tracks. And when the Kyiv-Odesa express came past, they would just kneel there and cry: “Bread, bread!” They would lift up their horrible starving children for people to see. And sometimes people would throw them pieces of bread and other scraps. The train would thunder on past, and the dust would settle down, and the whole village would be there crawling along the tracks, looking for crusts. But an order was issued that whenever trains were travelling through the famine provinces the guards were to shut the windows and pull down the curtains. Passengers were not allowed at the windows... (Grossman 158)

This sort of calculated terror and genocide is only one example in a series of other horrific events that demonstrated the brutality of the Bolsheviks and Stalin, yemakh shmoy, may his name be erased.

Stalin

When Lenin died on January 21 1924, Barukh HaShem,[5] there was no celebration by the majority of Jews; although Lenin’s anti-Semitism had already been intensely destructive, most Jews understood that Stalin’s hate for them was more pronounced than that of Lenin. Under Stalin’s regime, anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union took the form of a campaign against the “rootless cosmopolitan” (a euphemism for “Jew”) in a process Stalin called “Russification.” Terms like “cosmopolitan”, “Zionists”, and “individuals devoid of nation or tribe” were used to describe Jews, to isolate them from their Gentile neighbors. Because anti-Semitism eventually became associated with Nazi Germany, which was (after the period of collaboration ended) officially condemned by the Soviet Union, the state used these covert terms in their anti-Semitic policies. Out of a vast arena of murderous and oppressive policies and events, we have chosen three lowlights of Soviet anti-Semitism of this period: the Molotov-Ribbentrop or Nazi–Soviet non-aggression pact; the Night of the Murdered Poets (August 12, 1952); and the Doctors’ Plot (1952-53).

One of several pacts made between the Soviet and Nazi governments, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed, on the Soviet side, by a man who had only recently been named Minister of Foreign Affairs: Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov. His predecessor, Maxim Litvinov, who was Jewish, had been accused of “pro-Westernism”; he was, that is, too Jewish. Besides the now-familiar Soviet anti-Semitism, we can suppose that the Nazis would never have shaken hands with Litvinov. So Litvinov was fired and the non-aggression pact was signed, much to the chagrin of all the Communists and fellow-travellers already fighting fascists in other countries. In addition, Stalin often worked in tandem with Nazi Germany. In one instance Stalin turned away “large numbers of German antifascists and Jews,” who had fled the Nazis. In turn, the Nazis handed over large numbers of people, presumably “enemies of the state,” who were never seen again. (Medvedev 435) Maxim Litvinov would later be killed, possibly on Stalin’s orders; this one death the necessary prelude to the deaths of many others. Hatred of Jews, despite everything that stood between the two nations, proved a uniting factor between Nazi Germany and the USSR.

“Earth, oh earth, do not cover my blood!”

The final plea of Yiddish poet David Bergelson just before he was executed.

In 1952, only years after the Holocaust--the worst atrocity committed against Jews in modern times--Stalin began to target Jewish intellectuals, authors, poets, scientists, and their families within Soviet territory. Scores were arrested, executed, or exiled in another “calculated campaign to eradicate Jewish life in the Soviet Union.” (Poets, 5) On August 12 1952, Stalin ordered his men to round up the most famous Yiddish authors and poets. They were tortured in prison, some until they died; some were forced, despite their resistance, to confess to acts of treason. This was a common Bolshevik tactic. A rigged trial tried 15 of the surviving 25 Jews. In that trial, judges “asked the defendants about kosher meat and synagogue services”--one’s very own knowledge of Jewishness signaled treachery. The 15 were charged as being “enemies of the USSR,” “agents of American imperialism,” “bourgeois nationalist Zionists” and “rebels who sought by armed rebellion to separate the Crimea from the Soviet Union and to establish their own Jewish bourgeois nationalist Zionist republic there.” (Poets, 10) All were found guilty and executed except for the only woman on trial, a biochemist named Lina Stern, who was sentenced to three and a half years in a correctional labor camp and five years of exile. She was the only survivor.

The wounds on your face are covered by the snow,

So that the black-Satan shall not touch you. But

your dead-eyes blaze with anger, and your heart they

Trampled on cries out against

The murderous crew…

Somewhere in heaven, between the wandering shine,

A star lights up in honor of your brilliant name.

Don’t feel ashamed of the holes in you, and your pain!

Let eternity feel the shame!“To Solomon Mikhoels---an Eternal Lamp at his Coffin”

Peretz Markish’s poem challenging the death, a cover up, of Jewish poet Mikhoels.

These deaths and others like them left three million Soviet Jews “bereft of poets, writers, actors, teachers, leaders, theaters, artists and communal institutions of any kind. Even the Yiddish Linotype machines had been smashed.... The next generation might still be Jews, but they would be dumb and mute Jews, without poets, without song.” (Poets, 11)

On November 22 1955, a Soviet military court found “no substance to the charges” against the accused, however most had already been executed or tortured to death. This court decision “‘closed’ the case; it did not ‘rehabilitate’ the defendants.” (Rubenstein 415) In November 1955, the surviving widows, if they had not died themselves in the prison camps or in exile, worked the rest of their lives to restore their family name and the works of their late husbands, issued a request of rehabilitation of their dead husbands. However, this request was never made public and to the final days of the Soviet government, even the graves of those murdered Jews have been suppressed. It should be noted that after his death, the many atrocities carried out by Stalin had been publicly denounced by the Soviet government, but the silent pogrom of August 12 1952 remains unrecognized, further implementing the involvement of other Soviet officials and perpetrating a culture of anti-Jewishness. (Poets 11)

In their mass death, these massacred Jewish poets, these inextinguishable souls, sent us their last alert. What we must do in unity with them is to heed it, not to shrink away in horror, but to spread this alert, and wherever the Jewish self, the human self, is threatened to react, with all the strength of the living, and yes, the living dead. (Meyer Levin, Poets, vii)

Unfortunately, this was not the last bout of anti-Semitism in the USSR; many Soviet Jews came to fear the hammer and sickle, we surmise, as much as the swastika. In 1952-53, a group of prominent Moscow doctors (predominantly Jews) were accused of conspiring to assassinate Soviet leaders. This was accompanied by anti-Semitic characterizations in the media, which talked about the threat of “Zionism” and condemned people with Jewish names. Many doctors, officials, and others, both Jewish and Gentile, were dismissed from their jobs and arrested. Luckily, Stalin died; and after his death it came out that this so-called “Doctors’ Plot” was an invented conspiracy to demonize Jews and justify systematic anti-Jewish purges. Stalin’s plan was to first round up “pure-blooded” Jews, followed by “half-breeds.” Once Stalin had the Doctors’ Plot defendants executed and the Soviet goyim were brimming with anti-Semitic fervor, he would then present himself as the Jewish savior by sending them to camps far away from the purportedly enraged Russian populace, where he could further destroy Jewish life. There, he planned to exile all of the Jews to Birobidzhan, the Jewish Autonomous Region, in far eastern Russia. (Weinstein 245)

Conclusion

The terror against the people of Soviet lands continued after the deaths of Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin, and Jews continued to be persecuted. Although, Lenin had condoned pogroms, the long tradition of anti-Semitism could not be undone with his one sentence, and the Bolshevik goal of “uprooting Jews” from their Jewishness was still anti-Semitism. Just as the Jewish intellectuals had foreseen, that with each Jewish generation that passes, each one is more mute than the next, without poem, without song.

Under the banner of Communism and the hammer and sickle, millions of people--Jews and anarchists, but many many more besides--were persecuted, jailed, silenced, tortured, repressed, and murdered. The list is endless and, therefore, this zine is not complete. The examples of totalitarianism and fascist sympathies of the Bolsheviks, we feel, are more than sufficient. We write in hopes that this information will demonstrate to anti-fascists the importance of refusing to tolerate the presence of statist Communists in our movement, no matter their specific affiliation. Perhaps people who identify as statist Communists will also be moved by this material to renounce their politics and join us in our struggle against domination, racism, and oppression of all kinds... but we do not have any great hopes of that.

For two thousand years

I was a doubter. I shrugged shoulders

A “World Citizen” I called myself.

I belonged

To Polish forests,

To German fields,

To French spaces,

But they do not belong to me…

A doubter,

I called “My brother”

To the Russian, the French

Human beings like myself,

They have the same eyes

And mouth

And heart.

But when they hang,

When they shoot to kill,

They shout in my direction:

“Zhid!”

For two thousand years

I was a world citizen;

An exalted wanderer;

Blessed with imagination, and enchanted

I kneaded flour not mine

Revolutionary dough, bloody dough,

Doubting remained my lot.

The circle of my way was closed.

Near the wall of tears

I shall stand.

My flaming forehead

Is joined to the stone.

For the first time,

In two thousand years,

The worm of doubt will no longer gnaw

At my strength

And in the ways of a hangman’s world

In the rear I abandoned a wretched gift---

I left seeds of doubt.

“A Citizen of the World”

-David Markish

(The son of Peretz Markish, a murdered Jewish, Yiddish poet)

Bibliography

August 12,1952: The Night of the Purdered poets. 1972.

Berkman, Alexander. Bolshevik Myth: diary 1920-22. Active Distrobution 2017.

Boni, Charles. Letters from Russian prisons: Consisting of reprints of documents by political prisoners in Soviet prisons, prison camps and exile, and reprints of affidavits concerning political persecution in Soviet Russia, official statements by Soviet authorities, excerpts from Soviet laws pertaining to civil liberties, and other documents. 1977. University of Chicago Press, 1982.

Goldman, Emma, and Rebecca West. My Disillusionment in Russia. West. 1925.

Grossman, Vasiliĭ. Forever Flowing. Perennial Library, 1982.

Kusikov, Aleksandr. Sumerki. Chikhi-Pikhi, 1919.

Maksimov, Grigoriĭ Petrovich. The guillotine at work. Black Thorn Books, 1979.

Medvedev, Roj Aleksandrovič. Let history judge the origins and consequences of stalinism. Alfred A. Knopf, 1971.

Rubenstein, Joshua, and Vladimir Pavlovich Naumov, editors. Stalin’s Secret Pogrom: The Postwar Inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee.

Slezkine, Yuri. The Jewish century. Princeton University Press, 2006. Tanny, Jarrod. “Yids from the Hood: The Image of the Jewish Gangster from Odessa.” Newsletter of the Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies, 22 Jan. 2005, iseees.berkeley.edu/sites/ default/files/u4/iseees/publications_/2005_22-01.pdf.

The Truth about Kronstadt: A Translation and Discussion of the Authors, www-personal.umich.edu/~mhuey/TOC/KRN.frame.html.

Weinstein, Miriam. Yiddish: a nation of words. Ballantine Books, 2002.

“ We are always the victims. Under the Communists we have no violent mob pogroms; at least I have not heard of any. But we have the ‘quiet pogroms,’ the systematic destruction of all that is dearest to us — of our traditions, customs, and culture.”

—Jewish Peasant

[1] Emma Goldman notes in My Disillusionment in Russia that “It was significant that the Yevkom [short for Yevsektsii] was more anti-Semitic than the Ukrainians themselves. If it had the power it would pogrom every non-Communist Jewish organization and destroy all Jewish educational efforts.” (Goldman 223)

[2] Tcheka or Cheka was the first of many Soviet secret police. Along with carrying out disappearances and murders, the Cheka were also involved with policing the Gulag prison system.

[3] The Zionism of today--the occupation of Palestine and its supporters abroad--is not radical or revolutionary, but statist. It is antithetical to anti-fascism and anarchism, and, we would argue, Judaism. Though Zionism was once diverse, we are still against all of its varied socialist and communist forms. However, Zionists, as (then nearly always) Jews, were targets of Soviet anti-Semitism, so we have referenced their literature for this piece.

[4] Kulaks were landowning peasants who were labelled “tight fisted” for having more resources than their neighbors; they were seen as a rural form of the petite bourgeois and demonized as “enemies of the State.” This process is reminiscent of ways in which Jews are often characterized as wealthy and miserly by anti-Semites.

[5] Meaning, “Thank god,” but we use it here as “Thank goodness” or “its about time!”