Osvaldo Bayer

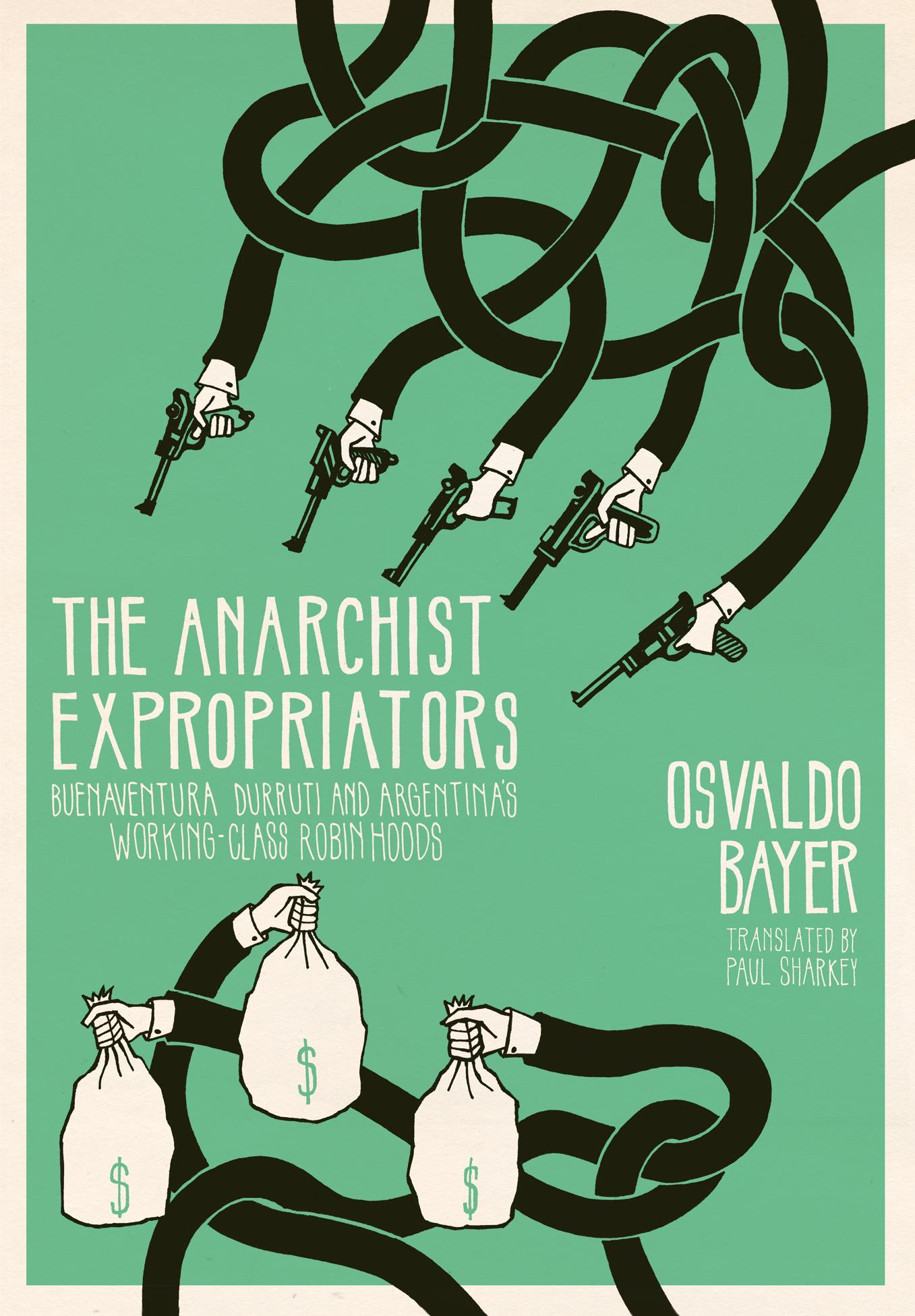

The Anarchist Expropriators

Buenaventura Durruti and Argentina’s Working-Class Robin Hoods

Introduction

It’s a chastening thought that Osvaldo Bayer wrote this book nearly forty years ago and his work still challenges us, as anarchists, with ideas, arguments, and problems that are still as relevant today as they were in 1975 or, indeed, as when the actions of this narrative were originally carried out.

Much of Bayer’s work belongs to the first wave of modern anarchist historiography that was, and still is, concerned with excavating anarchism’s stories; research that began to challenge our ideas as to what anarchism is and had been. Some of those early pioneering works include those by James J. Martin (1953) and Voline (first English translations in 1954 and 1955) as well as the works of Antonio Tellez (1974 in English), Bill Fishman (1975), Hal Sears (1977), and Paul Avrich (1978).[1] These authors, together with Bayer and others, made the 1970s an exciting time for anarchist research. “The Anarchist Expropriators” was first published in 1975 as “Los Anarquistas Expropriados y Otros Ensayos” and is here published in its first English translation. It appeared shortly after what we consider to be Bayer’s greatest work, the four volume “La Patagonia Rebelde” (1972–1975), soon to be published in one volume as “Rebellion in Patagonia” by AK Press. A later work, “Simón Radowitzky and the People’s Justice” (1991), was recently published by Elephant Editions. Bayer and some of the other writers mentioned here were lucky enough to know some of the relatives and comrades of those who feature in their work, and this knowledge informs their narratives with a richness and immediacy that later histories often lack.

The Anarchist Expropriators is a companion piece to Bayer’s earlier work “Severino Di Giovanni: El Idealista de la Violencia” (1970), which was translated into English as Anarchism and Violence by Elephant Editions in 1985. The main protagonist of that work, Severino Di Giovanni, is glimpsed only occasionally in this volume, which in essence concentrates on other groups of anarchists carrying out acts of expropriation and revenge both alongside Di Giovanni and his comrades and after Di Giovanni’s execution on February 1, 1931. It presents us with additional information on the Argentinian anarchist expropriation movement that peaked during the twenties and thirties. Vicious infighting between anarchists, ruthless state opposition, bad luck, and its own ineptness destroyed this complex, challenging, and provocative movement, and Bayer attempts to show how that happened. Like Anarchism and Violence, the book is short on analysis but long on action. Events hurtle along at breathtaking speed and, by the final page, we are left breathless (and a little confused as to what has just happened!).

It is best not to read this book as a portrayal of the romantic outsiders who cannot fit into society and take a principled stand against all the everyday hypocrisies they see in anarchists and the rest of the world—the Stirnerite individualists going out guns blazing, proudly proclaiming their identity in a world that constantly attempts to suffocate them. Undoubtedly there are traces of that, but the people here are a little different from Di Giovanni and others who featured in Bayer’s earlier work. You won’t find in these pages the heightened language, the passionate hyperbole, the tragic hero set against the world. Men such as Miguel Arcangel Roscigna and Juan Antonio Moran seem much more hardheaded and pragmatic. In different circumstances, they could have been the 1936 version of Durruti who survived his own expropriation career and, during the period covered by this volume, was no different from these men. Indeed Durruti thought so highly of Roscigna and his activities that he wanted him to come to Spain and help with the anarchist struggle there.

Argentinian anarchism in the twenties and thirties was a product of brutal state repression against a movement that, in the early part of the twentieth century, was a force to be reckoned with.[2] This repression, exemplified by the events of 1st May 1909, the Social Defense Law of 1910, and the Tragic Week of 1919, together with a constant, brutal day-to-day treatment at the hands of the police and other agencies, reflected the concern anarchism engendered in the authorities. Reacting to these and other factors, such as the popularity of syndicalism among the working class, some anarchists began to analyze and reflect on what they believed and where they thought these beliefs should take the movement. Spurred on by the events of the Russian revolution, writers such as Lopez Arango and Abad de Santillán, for instance, were teasing out the relationship between syndicalism and anarchism in the labor movement, discussing the nature of trade unions, and the intricacies of class as the “lodestar” of anarchism as they attempted to rebuild a movement that would bring about the world they desired. The primary vehicle for this discussion was La Protesta, the paper they edited.

All this is well and good, but there were still profound differences in the movement and, as is so often the case, this slice of anarchist history reverberates with internecine quarrels—quarrels that became bitter and bloody but, in themselves, are reminiscent of similar quarrels in other countries and at other times. In essence, they revolved around those constant and exhausting questions of what anarchism is and the best way to practice it and bring about anarchy. Bayer is careful to try to delineate the complexities of these differences and provides us with a useful guide to understanding them.

But there is still a little more that we may need to consider. Personality clashes and questions of ownership of resources had a deleterious effect on theory and practice. The execution of one of La Protesta’s editors, Lopez Arango, probably by Di Giovanni, in October 1929 is chilling. This though was not the first time that violence had occurred within Argentinian anarchism. We should remember that, in August 1924, gunmen from La Protesta raided the anarchist paper Pampa Libre leaving one dead and three wounded. These were not simply intellectual and practical differences between comrades, but ones that were visceral, deeply felt, and with deadly consequences. Such tensions brought about some kind of fractured dialectic between the realities of the world outside the movement and the antagonisms within it. The results were not edifying.

Understanding the development of these tensions is not easy from this distance. One senses that much of the antagonism on the part of those around La Antorcha (presented in this volume as essentially La Protesta’s most constant critic) who had broken away from La Protesta in 1921, consisted of a number of factors. A major concern was the printing press and resources that La Protesta owned: who gave the present editors the right to own them and why weren’t these resources shared across the movement? Secondly, and just as importantly, was the fact that La Protesta saw itself as THE PAPER of the Argentinian anarchist movement (with the backing of the FORA) while La Antorcha saw itself as ONE of the papers of a much more diverse anarchist movement than the one with which those around La Protesta identified. The editors of La Antorcha certainly did not offer whole-hearted support to the expropriators, but it did support expropriator anarchists who were imprisoned (unlike La Protesta who saw them as “anarcho-bandits”). It also condemned La Protesta’s habit of naming or slandering those who had committed expropriations (La Protesta, for instance, described Di Giovanni as a “fascist agent”), calling the editors police informers. Hence the question of violence may not have been quite as central as Bayer suggests in driving the antagonism between the two papers. All this, remember, occurred between groups of people, many of whom had worked together in previous years, and indeed would in future ones.

A feature of the Argentinian movement was its internationalism. Italian, German, Spanish, and Russian anarchists regularly traveled in and out of the country, providing the movement with both a richness of ideas and strategies, as well as all the practical realities that internationalism actually meant—not so much a theory, more a way of life. The French anarchist Gaston Leval was associated with La Antorcha, while Abad de Santillan, one of the editors of La Protesta, was in Berlin between 1922 and 1926 working with the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA) as the Argentine Regional Workers’ Federation (FORA) delegate, and this is reflected in the pages of the various newspapers. La Protesta regularly sent assistance back to Italian anarchists both before and after the rise of Italian fascism, while many articles from the strong Italian anarchist community in Argentina were aimed at those anarchists trapped in Italy or in exile, as well as attacking Italian fascists in Argentina. Meanwhile, La Antorcha published writings on the situation for anarchists in Russia as well as in Italy and other countries.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the struggle against fascism resonated within the Argentinian anarchist movement. The struggle against the death sentence placed on Sacco and Vanzetti was equally important and influential. Di Giovanni and others were in regular contact with the American, Italian-language paper L’Adunata dei Refrattari throughout the campaign and, after the executions, Sacco’s companion wrote to Di Giovanni thanking him and his comrades for their efforts on behalf of the two men; efforts that had included bombings as well as other more sedate propaganda activities.

This internationalism took an interesting turn in early August 1925 with the arrival of members of the Spanish “Los Solidarios” group, who were on the run from Europe and fresh from robbing a bank in Santiago, Chile. By October 1925 they had commenced activities in Buenos Aires and, by January 1926, had help and support from Argentinian comrades there. The Los Solidarios members (Ascaso, Durruti, and Jover) were robbing banks, metro stations, and tram depots to raise funds to support revolutionary activity in Spain—and quite probably in Argentina too. During their time in the country, they became close to Roscigna and others who would be active in the fight to prevent the deportation of the three Spaniards from France to Argentina (they had left the country in spring 1926), where they were wanted for killing a policeman and a bank employee during the course of their robberies. It was a fight that La Protesta described as “not qualifying for the description of anarchist.” It was a statement that only added to the tension between the various anarchist tendencies.

Roscigna belonged to part of the anarchist movement that insisted on maintaining what they felt was an ideological purity; there could be no joint front with communists against fascism or in support of Sacco and Vanzetti, for example. In Russia, these communists had been responsible for the murder, execution, and imprisonment of countless anarchists. To work with them in any way would betray the memory of these dead, and would dilute anarchism into some type of pragmatic convenience. How could people know what anarchism was unless it remained pure? An anarchist movement could not be built on joint and popular fronts. Rather Roscigna and others favored a sort of permanent confrontationalism, a constant war against capitalism and the state where anarchism would make no compromise. In 1924, the FORA had expelled those around La Antorcha and other anarchist papers from the “Comite Pro Presos y Deportados” (Prisoners and Deported Solidarity Group), and in response these papers had called for direct aid to anarchist prisoners, their families, and the families of those deported. For Roscigna and his comrades, the aim was not just getting funds to anarchist prisoners but to get them out of prison—and that would take time and money. To that end, he also became fascinated by the possibilities counterfeiting offered. In a sense his move to expropriation was a logical one, re-enforced by those from Spain who were engaged in the same strategy, who came from a similar social background as himself and possessed the moral purity he felt essential in order to describe oneself as anarchist.

Moran, the other major protagonist of Bayer’s work, showed a similar pragmatism. Twice General Secretary of the powerful Maritime Workers Federation, Moran fought a constant running battle against scab labor and intimidation. It was a battle he felt could not be won by conventional means, and he was part of the group who decided to execute Major Rosasco, the man spearheading attacks on anarchists, labor radicals, and others. The statement of those who carried out the execution ended with the words “these proletarian fighters have shown, by executing Rosasco, how we may be rid of the dictatorship, root and branch.” Like the Spanish action groups, Moran shared the belief that, sometimes, extreme measures were the only defense available to unions and organizations. One had to fight fire with fire or be destroyed.

Of course it is never that simple, never that straightforward. It’s easy for us to create patterns that were not there or lose sight of the nuances that have become hidden over the years. We can’t be certain why people do what they do or how events around them shaped their actions. We can say, though, to see the necessity of using arms to obtain funds does not necessarily mean that those who arrived at this position were any good at it in practice. Los Solidarios gained hardly any money from some of their efforts, while the Spanish anarchist group around Pere Boadas—a member of “The Nameless Ones” and not Los Solidarios as Bayer suggests—were murderously inept in their raid on the Messina Bureau de Change at the Plaza de la Independence on the afternoon of October 25th, 1928. Their arrest led to other raids being undertaken to fund their escape (which succeeded) and, eventually, their actions would lead to more arrests.

As time went on, more of the groups were arrested, which resulted in more energy spent on working out how to free the imprisoned comrades. The groups began to live in a world of their own—always a danger in work of this sort, and especially so as the popular support base erodes. As part of his everyday work, Moran may have been able to chat with people who weren’t taking part in actions and, by doing so, he was able to temper his actions with realism. It became harder for others who, perhaps, grew more contemptuous of those who did not share their commitment and found it hard to know who to trust. The movement, if that is what it was, became more and more concerned with revenge on individual policemen as their comrades were killed and imprisoned. It became a small world of attack and counter attack with the protagonists known to each other, and everyone else relegated to onlookers. For the members of Los Solidarios there was always the organization in Spain; for the Argentinian anarchist expropriators there eventually was just themselves.

Of course the tension with the various strands in the anarchist movement increased as the actions continued and state repression grew worse. None of the tendencies appeared to understand the position of the others. Indeed one senses that they were determined not to! For those around La Protesta the most important work that anarchists could do was to create a movement; to bring numbers of the working class and others to their cause; to hold meetings, talk to people, produce newspapers, and pamphlets that would build an educated, mass movement that could sweep the dirt of capitalism away. In their opinion, those in the action groups actively prevented this from happening. They put anarchism on the defensive, created a false impression of what anarchism was, and alienated everyone. If they did that, if they prevented the movement’s growth, they were, objectively, assets of the state.

Looking at it now from the hindsight of ninety or so years it all becomes horribly poignant. There seems to be no common ground between the antagonists and, yet again, anarchist history gets bogged down in its own quarrels and vendettas. However we read and interpret Bayer’s work, it is a challenge to discover anything positive. Thoughtful attempts to define the ideas of anarchism and its possibilities as carried out by Santillan etc. on one hand, versus a frustration with theory and a logical move to expropriation, often characterized by exemplary bravery and courage, on the other.

Yet there are matters that should concern us here. The ending is unbearable with the murder of Moran and the others. Just as painful, if not more so, is the escape attempt of the anarchist prisoners in Caseros. With no hope of outside help, essentially abandoned, they still made their attempt. Expropriators some of them may have been, but to abandon them? Surely no “correct” anarchist line is worth the abandonment of those who also profess anarchism. We may have the right answer (even if we haven’t the mass movement to celebrate the fact) but comradeship, in anarchism, has to sometimes cross the boundaries between those who agree with every word you say and those who question your methods and practices in the most profound way possible. As a comrade in La Antorcha wrote, “the expropriators were always better than those who repressed them” and it appears that some forgot this.

Some of the survivors of this story appear again in Spain during the revolution. Some played important roles, others less so. All were fighting fascism and attempting to create the most profound revolution we have, so far, known. Abad de Santillan was working hand-in-hand with Spanish anarchists who had been members of action groups and, at times, expropriators. Circumstances change and, when you think you are winning, all is forgiven. As we said earlier, the qualities of a Roscigna, or a Moran, could have blossomed in Barcelona before the May Days of 1937 and if we want to admire a Durruti or Ascaso for how they made their lives (“mistakes” and all) in trying to help construct a new world, perhaps the anarchist expropriators are worthy of a similar respect. Let’s see where that takes us.

— Kate Sharpley Library

Chronology of Events

June 18, 1897.

The first issue of La Protesta Humana is published. In 1903 it becomes La Protesta.

March 25–26, 1901.

FOA (Argentine Workers Federation) is formed with approximately ten thousand members. It is syndicalist in nature and rejects party political involvement.

1905.

At its Fifth Congress, FOA becomes the FORA (Argentine Regional Workers’ Federation) with a commitment to anarchist communism.

May 1, 1909.

A cavalry detachment under the overall command of Ramon Falcon, Chief of Police, opens fire on a demonstration in Plaza Lorea. Several demonstrators are killed and many wounded. An ensuing General strike last nine days with over two-thousand arrests.

November 13, 1909.

Eighteen-year-old Ukrainian anarchist Simon Radowitzky throws a bomb at Falcon’s car, killing both Falcon and Falcon’s secretary. Due to his age, he will be sentenced to indefinite imprisonment.

Martial law is declared and remains until January 1910. The offices and printing press of La Protesta are destroyed during this period.

April, 1915.

9th Congress of FORA reverses their support for anarchist communism. A minority of members break away and form FORA V, remaining committed to anarchist communism. This is the FORA that appears in this book. The majority become FORA 1X.

December, 1918.

A strike breaks out at the Vasena metal works in Buenos Aires.

January 2–14, 1919.

Events take place that will become known as La Semana Trajica (The Tragic Week).

January 7, 1919.

Strikers attempted to stop a shipment of materials from leaving the plant. The police open fire, killing five workers and wounding many.

January 9, 1919.

Violence breaks out between police and mourners at the funeral of the five workers killed outside the Vasena plant. The two FORAs call for a General Strike.

January 10, 1919 onwards.

The right-wing Argentine Patriotic League attack the Russian Jewish areas of Buenos Aires.

January 12, 1919.

The 9th Congress FORA decide to call off the General Strike.

January 14, 1919.

Police raid the offices of La Protesta and smash its printing press.

January 20, 1919.

The strike is called off. Over the course of the Tragic Week, fifty thousand would be imprisoned and many workers killed.

May 19, 1919.

The first politically motivated armed robbery in Argentina takes place as the manager of a bureau de change is targeted. It is a failure with no money taken and a policeman killed. The robbers are captured.

1921.

The newspaper La Antorcha breaks away from La Protesta and will run until 1932.

1920–1922.

A series of strikes, general strikes, and insurrections take place among the rural workers of Patagonia. In 1921, hundreds of striking workers (some of whom had surrendered) were summarily executed by the 10th Cavalry under the command of Colonel Hector Varela.

January 27, 1923.

Colonel Hector Varela is killed by the Tolstoyan anarchist Kurt Wilckens in response to the killings of workers in Patagonia.

June 16, 1923.

Kurt Wilckens is murdered in prison by a member of the right-wing Patriotic League, aided by the connivance of prison officials.

August 4, 1924.

Gunmen from La Protesta and FORA wreck the presses of anarchist newspaper Pampa Libre. One person is killed, several are injured.

September, 1924.

FORA advises its members to boycott the anarchist newspaper La Antorcha.

June 9, 1925.

Three members of the Spanish action group Los Solidarios (Ascaso, Durruti, and Jover) arrive in Valparaiso, Chile.

July 11, 1925.

Los Solidarios rob the Bank of Chile in Santiago

Early August 1925.

The group moves on to Buenos Aires.

August 1925.

Culmine, the paper of Di Giovanni and the Renzo Novatore group, appears as a monthly journal.

October 18, 1925.

An armed raid by Los Solidarios on Las Meras tram depot nets very little money.

November 17, 1925.

Los Solidarios raid on Primera Junta metro station results in the death of a policeman and little money taken.

January 19, 1926.

Roscigna and others are involved in the robbery of a provincial bank in San Martin. Substantial money is taken with one employee killed and one wounded.

February 1926–April 1928.

Culmine appears as a weekly.

April 30, 1926.

Ascaso and Durruti arrive in France. Jover arrives soon after them.

December 1926.

Of the protests and campaign to resist the extradition of Ascaso, Durruti, and Jover from France to Argentina, La Protesta writes “they do not qualify for the description anarchist.”

April, 1927.

Extradition of Ascaso, Durruti, and Jover from France to Argentina is confirmed.

July, 1927.

The time limit for extradition runs out and Ascaso, Durruti, and Jover are released in Paris and immediately extradited to Belgium.

October 1, 1927.

Raid on Rawson Hospital is coordinated by Roscigna to gain funds for anarchist prisoners. A policeman is killed during the raid and Roscigna and others flee to Uruguay. The proceeds from the raid are used to make counterfeit money.

August 11–16, 1928.

Tenth Congress of FORA is held—the last major congress of the federation for fifty years.

October 20, 1928.

Pere Boadas, a member of the Spanish action group The Nameless Ones leads a raid on a bureau de change in the Cambio Messina in Montivideo. Boadas had been sent to Argentina to encourage Roscigna to come to Spain and work with the anarchists there. The raid is carried out against Roscigna’s advice, and three people are killed (a business man, a shoeshine boy, and a taxi driver).

November 9, 1928.

Boadas and others are arrested.

May 20, 1929.

FORA stages a twenty-four-hour strike in solidarity with the “Free Radowitzky” campaign.

October 25, 1929.

Someone (Di Giovanni?) assassinates Emilio Lopez Arango, an editor of La Protesta.

April 13, 1930.

Radowitzky reprieved and expelled to Uruguay.

October 2, 1930.

Roscigna and Di Giovanni rob a sanitary services wage clerk, taking 286,000 pesos. The money is used to fund the escape of Boadas et al. in March the following year.

January 29, 1931.

Di Giovanni and Scarfo are arrested.

February 1, 1931.

Di Giovanni is executed by firing squad.

February 2, 1931.

Paulino Scarfo is executed by firing squad.

March 18, 1931.

In an escape plan engineered by Roscigna and Gino Gatti, an Italian anarchist, Boadas and three others from the Cambio Messina raid are sprung from prison through as carefully constructed tunnel. Three anarchist members of the Bakers Union also are freed.

March 27, 1931.

Roscigna and others are arrested.

June 12, 1931.

Juan Antonio Moran and others shoot and kill Major Rosasco in retaliation for his ill treatment of prisoners, including the use of torture.

July 11, 1931.

Pere Boadas is arrested. He is released in 1953.

September 6, 1931.

The era of military government begins. The worker’s movement is attacked, newspapers are shut down, and trade unions and political and cultural organizations are banned. Anarchists are imprisoned or deported.

September 1932.

Martial law is lifted. La Antorcha and La Protesta and various unions bring out the joint manifesto Eighteen Months of Military Terror.

June 28, 1933.

Juan Antonio Moran is captured.

August 11, 1933.

Juan del Piano, the last of the expropriators at large, is killed by the police.

October 7, 1933.

Anarchist prisoners in Caseros make an escape attempt. It fails. Three guards and one anarchist are killed.

May 10, 1935.

Juan Antonio Moran is released for lack of evidence, and is kidnapped outside the prison.

May 12, 1935.

Juan Antonio Moran’s body is found. He had been shot in the head.

December 31, 1936.

Miguel Arcangel Roscigna and three others are released from prison in Uruguay, and handed over to the Argentinian police. Roscigna and two others disappear while in police custody. Their bodies are never recovered.

— Kate Sharpley Library

The Anarchist Expropriators

Opposed, vilified, even by other libertarian currents, the anarchist “expropriator” movement, as its supporters described themselves—otherwise, illegalist anarchism—was in vogue in Argentina in the 1920s and 1930s.

Recollecting and writing their story is certainly not the same as claiming it for one’s own. Offering an objective explanation of how society developed just three or four decades ago is not just a difficult undertaking but, above all, it’s a risky one. Precisely because of the confusion between objectivity and partisanship.

Who, for example, would question the tale of Robin Hood, which every child has read? Now Robin Hood took from the rich and gave to the poor—and “taking,” robbing, and expropriating are all synonyms. But at several centuries’ distance, Robin Hood looks like an attractive personality, maybe because his life is the stuff of legend, or because it is merely the product of the imagination. But the anarchist expropriators are not products of the imagination. They existed—and how! Not that they were all Robin Hoods, any more than they were all Scarlet Pimpernels.[3] They were intractable when it came to defending their lives, because they knew that one false move or the slightest sign of weakness meant they would be executed in the street or in front of a firing squad. In a way, they were urban guerrillas, but they could not rely on any foreign power for funds and weapons, and there was nowhere to seek asylum when things got too hot. They lived from day to day, without any breaks. They were interesting figures who attacked society (“bourgeois” society) with bombs and revolvers, while their newspapers were violent in their criticism of the Bolshevik dictatorship, invoking the name of the gleaming, immanent Golden Fleece: Freedom.

“We cannot own them as ours,” we were told by one of the last great anarchist intellectuals, Diego Abad de Santillán. True, but we cannot ignore them either. In Argentina, the anarchist expropriator movement was very significant—even more so, perhaps, than in Spain—even though it survived for only fifteen years. It embraced a motley crew of academics, workers, and a few outright criminals who made up a very distinct rogues’ gallery.

The first politically motivated armed robbery in Argentina took place on May 19, 1919. Given the time and the setting, only Russians could have been behind it. (Society was living through the whirlwind of the Maximalist revolution in Petrograd and Moscow.) The Argentinian anarchists’ ranks included a numbers of Slavs, whose names echoed through the gunfire outside trade union premises or after bomb outrages. Radowitzky, Karaschin, and Romanoff had disturbed the blithe existence of the porteños.[4] So whenever the newspapers named the perpetrators of this first political outrage, their readership must have nodded and exclaimed: How could it have been otherwise? It could only have been Russians!

Everything about that first outrage was singular, starting with its protagonists. This simple narrative cannot convey the atmosphere of conspiracy, the nihilistic mysticism and religious embracing of a destiny of suffering, which awaited the two political desperadoes when they shattered the tranquility of the Chacarita district with their gunfire in the late afternoon in May 1919. These were characters worthy of a Dostoyevsky novel or maybe the melancholy ironies of Chekhov.

The outrage—a sign of the times this—began on a tram. Fear reigned in Buenos Aires. President Hipólito Yrigoyen[5] had lost control of the situation over recent weeks and it had all culminated in the massacre at the Vasena workshops, and the proletariat had not forgiven that.[6] El Peludo[7] was to be confronted by 367 strikes that year—two more strikes that the year has days. And while anarchist intellectuals kept arguing with one another about the society of the future, when there would be no more governments, the anarcho-individualists were bent on direct action and burning trams or blowing up bakeries.

By that point, the left had already experienced one split that had repercussions upon trade union life in Argentina: one strand of anarchism had gone over to the Russian revolution, which is to say, to the Maximalists (Bolsheviks). The other strand though, the majority anarcho-communist strand, was as critical of capitalism as of Lenin’s government, having the view that these were two forms of the same phenomenon of dictatorship.

The arguments between the two were vitriolic. The more “pragmatic” anarchists—who backed the Russian revolution—argued their case in the columns of Bandera Roja, while the die-hard anarcho-communists damned them as opportunists and traitors in La Protesta, El Libertario, and Tribuna Proletaria.

The two protagonists of the May 1919 outrage were drawn from the ranks of the anarchist faction that supported the Russian revolution. These were no “opportunists,” merely Russians who sought to finance the launch of a Russian-language newspaper as a way to explain to their countrymen, who had also settled in Argentina, just what was happening in distant “mother” Russia.

The Perazzos were a couple who were doing quite nicely, thank you. They had a currency exchange at 347 Rivadavia Street, in the building that had formerly housed the Chamber of Commerce. They closed the exchange at 7:00pm every day, and went home to the Chacarita district on the No. 13 tram, which they caught in the city center and which dropped them off just a few meters from their home. Pedro A. Perazzo normally carried a briefcase.

For a few days early in May, Señora Perazzo noticed the unusual eyes of two strangers watching her through the exchange’s plate glass window. One of the men was quite fair-haired with a Polish look to him, whereas the other one’s eyes were dark and twinkling. She brought this to her husband’s attention but he dismissed it as of no consequence. On May 19, the Perazzos left the bureau at 7:30pm, and caught the usual No. 13 tram homeward. Señor Perazzo had his briefcase with him.

En route, his wife felt unsettled; she was sure that the passenger sitting behind them was the Polish-looking stranger who had been watching incessantly lately. She told her husband, who reassured her but was actually also on the alert, for he had noticed something: the tram was being tailed by a car that had drawn up close behind several times, and one of the passengers had been sneaking a look in their direction.

As they arrived at their stop, Perazzo was more at ease. There, at the junction of Jorge Newbery and Lemos streets, there was plenty of light and traffic. Two tram routes passed that way and only fifty meters separated them from busy Triunvirato Street.

Just as he was climbing down from the tram, his wife suddenly tugged at his jacket sleeve and froze. The “Pole” had disembarked too. The tram carried on along its route. The mysterious car drew to a halt and the dark-eyed man got out.

Next the “Pole” produced a revolver and hurled himself on Perazzo, while his wife fled, screaming. Perazzo was so stunned that he clung to his briefcase. The “Pole” tried to wrest it from his grip but when that failed, he lost his cool and started shooting all over the place.

At that point, the No. 87 tram arrived on the scene, with two policemen on the platform. Seeing the scene in front of them and hearing the gunshots, the policemen drew their guns and took aim at the car and at the fair-haired man who had finally managed to get the briefcase.

His accomplice in the car called to him, but he didn’t hear and was so on edge that he ran off on foot while continuing to shoot in every direction. One bullet struck the tram-driver in the chest and he slumped to the floor.[8] Another bullet hit one of the policemen in the foot.

Unable to help their comrade, the dark-eyed man and the driver of the mystery car made their escape. The gunman, with the other policeman in pursuit, raced down Lemos Street, and then turned north down the unasphalted, pitch dark Leones Street. He reached Fraga Street, but he was jinxed: no. 225 Fraga Street was the home of two policemen, who, having heard gunfire, had come out with their guns. Spotting the malefactor—who had dumped the briefcase on the corner—they took cover behind some trees and emptied their weapons in his direction. One of their bullets shattered his left arm. Infuriated, he advanced towards the policeman hiding behind the tree, fired one lethal shot into his chest—his last bullet—and took shelter in a coal depot. The coalman, whom curiosity had drawn out on to the street for a closer look, was struck in the eye by one of the policemen’s bullets.

Out of ammunition and wounded, the malefactor took cover behind some flowerpots and ferns. There, he collapsed from exhaustion and was arrested.

It had all gone wrong: a real “farce.” One policeman dead, the coalman and the malefactor both seriously wounded—and the latter bleeding profusely—and the Perazzos and another policeman slightly injured. All for nothing.

Who were the malefactors? That was something that would surprise the police in the course of their enquiries, which would be slow and complicated, in spite of the vengeful zeal invested in them.

The unknown offender was treated before being subjected to questioning, which must not, of course, have been unduly gentle. He was tall, beefy, pale-complexioned, with short chestnut-brown hair and Slavic features. His clothing was modest but clean. He had papers in the name of Juan Konovesuk, born in (Russian) Bessarabia on January 27, 1883. Later his real name came to light: he was Andrei Babby, a White Russian naturalized Austrian, born in Bukovina on the border of the two empires. He was thirty years old and had been a resident of Argentina for the past six years. He was a bookkeeper.

In spite of hour after hour of questioning, the police could get nothing out of him except a far-fetched story. Babby told how he had been sitting on a bench in a square, jobless, when a sinister-looking, bushy-mustached individual, known as “José the German,” had invited him to have lunch with him and offered him a “simple job” that paid a few pesos. All he had to do was follow a couple (the Perazzos) on the tram and snatch a briefcase from the man when they got off. Babby said that he was afraid to refuse and that, once on board the tram, he had seen “José the German” following in a car and looking menacingly at him in order to make sure he did his part. Babby claimed that this was all the information he could give about this mystery man.

Each day, the porteños read the reports of the attack and about the investigation’s progress. The newspapers carried lengthy reports on Babby’s statements, and indulged themselves in speculation about “José the German.” So much so that a sort of psychosis developed, wherein everybody thought they knew someone who looked that suspicious. Because of this, the police received dozens of denunciations, emanating mostly from prostitutes and café owners.

Unconvinced by Babby’s story, the police conducted enquiries in all the German restaurants. But the owners and waiters were quite embarrassed about their answers, because their German clientele included lots of men who actually wore a mustache like the Kaiser’s—although Wilhelm II had by then lost the war and his throne—and fitted the description.

The police received an anonymous tip about Andrei Babby’s address; he had a room at 1970 Corrientes Street. On being questioned, the concierge stated that Babby shared it with a certain teacher, one Germán Boris Wladimirovich. The police asked to speak to him, but he had packed his bags on May 19.

The room was searched. From a photograph, Señora Perazzo identified Boris Wladimirovich as the dark-eyed man who had been watching her through the exchange’s window and who got out of the car when Babby had snatched the briefcase from her husband.

The police, sensing that Boris Wladimirovich was the brains of the operation, jumped into action. They asked about his associates, and came up with the Caplán brothers, who readily admitted that they knew him. They said that he and Babby were anarchists and that Wladimirovich was very friendly with a member of staff at the La Plata astronomical observatory, where he was wont to visit, being an enthusiastic student of the stars.

At the observatory there was a real find: two of Boris Wladimirovich’s suitcases filled with anarchist publications, books, letters, and essays. Boris’s friend on the staff, who had no idea of what his friend had been mixed up in, told detectives that he did not know where Boris was, but that a Ukrainian from Berisso—one Juan Matrichenko—might be able to help them there. The police traced Matrichenko and intimated to him how worried they had been because, they claimed, they feared that Boris had been kidnapped. The quick-witted Matrichenko quickly reassured them, stating that he had recommended Boris to a friend in San Ignacio in Misiones province. Moreover, driver Luis Chelli had to know the date when he set off because Wladimirovich was always calling upon his services. Two birds with one stone! After searching the driver’s home, detectives telegraphed their information to the police in Posadas. They discovered anarchist materials in Chelli’s room and the Perazzos identified Chelli as the driver of the vehicle involved in the attack. It was all becoming clear now.

Wladimirovich was arrested in San Ignacio. The police found it odd that a man such as him should have turned to crime. He had the air of an academic, an intellectual about him: affable manners, an intelligent look in his eye, a face marked by a sort of inner suffering. His capture caused such a sensation that the governor of Misiones, Doctor Barreiro no less, had himself driven to the police station and spent hours conversing with the anarchist. And when the police contingent arrived from Buenos Aires, headed by Inspector Foppiano, the governor himself decided to make the long train journey to bring the prisoner back to the capital.

Before they set out, the police and provincial authorities had themselves photographed for posterity. They all sat in unnatural poses in front of Boris Wladimirovich. The Nietzschean-looking prisoner looks as if he has nothing to do with all this rigmarole, while the eminent officials are staring stiffly at the camera.

Meanwhile, police had checked out Wladimirovich’s identity. He was a forty-three-year-old Russian widower and writer. La Prensa had additional details for its readership: “Boris Wladimirovich has an interesting personality. He is a doctor, biologist, painter, and had a certain profile among Russia’s progressives. According to police files, he is alleged to be Montenegrin and a draughtsman, but he is in fact Russian and descended from a family of the nobility.” At the age of twenty-nine, Boris had renounced his inheritance in order to marry a revolutionary working woman. It was known that he had squandered his personal fortune in pursuit of his ideals.

He was a doctor and biologist but had never practiced, except for a brief period as a teacher in Zurich, Switzerland. Doctor Barreiro had been able to savor a few of his scientific theses while they were traveling companions.

Boris had been a Social Democrat and had taken part in the socialist Congress in Geneva in 1904 as a Russian delegate. It was there that he had his first falling-out with Lenin, although he admired the man’s intellect. As for Trotsky’s positions, he preferred not to comment.

The police pressed ahead with their inquiries: Boris was the author of a number of published works, including three sociological treatises. He spoke German perfectly as well as French and Russian, and had a command of most of the tongues and dialects in use in his mother country. And he spoke Spanish relatively well. His hobby was painting: indeed he had left twenty-four canvasses behind in Buenos Aires, one of them a self-portrait. Finally, he had given lectures on anarchism in Berisso, Zárate, and in the capital.

But why had this man, an active member of the European revolutionary movement, come to Argentina?

Little by little, more details emerged. His wife’s death and the awful failure of the 1905 Russian revolution had destroyed his morale. Melancholy by nature, he sought consolation in vodka, a drink that he had had a fondness for since a heart attack. He had given his home in Geneva to his co-religionists and had moved to Paris, where he decided to go on a long journey in search of rest and to recuperate from his depression. One of his friends, whose brother had some property in Santa Fe province, urged him to spend some time in Argentina. Wladimirovich arrived in 1909 and frequented Russian labor circles. After some time staying with his friend’s brother, he moved to Chaco, where he spent four and a half years. He lived on what little money he had left and devoted himself to studying the region, roving from Paraná to Santiago del Estero, and exploring the Patiño marshes in particular. He lived frugally, although his taste for vodka had become more and more pronounced. In Tucumán, he had learned the news of the First World War’s having erupted and had decided to return to Buenos Aires. The official mouthpiece of the Patriotic League La Razón stated: “he was received with open arms in Buenos Aires by the progressives who, in spite of his lengthy absence, could not forget his libertarian activity on behalf of his mother country. Indeed that very absence added to his prestige. He resumed his propaganda, giving lectures, and expounding upon his ideas with conviction before workers’ circles. He would mount the rostrum, and the size of his audience scarcely mattered to him. When the riots erupted in 1919, Boris traveled down to La Chacarita to set up a revolutionary committee with a solid basis, but he came upon a gang of people who refused to abide by any program or who were incapable of doing so: all they were fit for was lashing out blindly. He was tremendously disheartened.”

After the Tragic Week, Boris focused on the danger constituted by Carlés’s young disciples who were threatening to kill “all Russians.” In fact, “Hunt down the Russian” was a catch-phrase of those younger members of the upper and middle bourgeoisie in Buenos Aires, who had enlisted either in the Civic Guard or in the Argentine Patriotic League. During the week of bloodshed that January, they also carried out iniquitous and criminal outrages in the Jewish districts, because a Jewish person is often referred to as “the Russian” in Argentina. A few hotheads, carried away by what they believed was some sort of divine mandate, even went so far as to urge a “massacre of Russians.”

Boris thought his ideas through. It was, he thought, his duty to enlighten his countrymen who had settled in Argentina, particularly with regard to the implications of the October revolution, which, he argued, would usher in undiluted human freedom. Because of that, he became truly obsessed with the notion of publishing a newspaper. He regarded it as essential that he have a newspaper at his disposal because, as some journalists reported a few weeks later (after he was released from isolation), “Those who leave Russia for Argentina are the dregs of the people, above all the Jews, who, taken all in all, represent an incoherent mass incapable of establishing a serious revolutionary program, much less putting a grand theory into practice.”

But it takes money to launch a newspaper, and there were only two possible options: either organize a venture of some consequence, or, more modestly, depend upon the meager involvement of workers of Russian origin and an intellectual who would go without food for a few days in order to save money towards the printing costs of the first issue.

Given his background, Boris was not used to small beer and subsistence living. He lived from day to day, getting money from the sale of some painting or from language lessons, and did not hesitate to treat himself to a fancy restaurant meal when he was flush with money. Thus he frequented the “Marina Keller,” a German restaurant on 25 de Mayo Street, where the prevailing atmosphere was quintessentially European and where there was genuine Russian vodka to be had. Boris revealed his plans to the Chelli, an anarchist driver who often left him at home in his room when the vodka had robbed him of any sense of direction. Chelli was a man of action who had also taken part in the week of strikes in January. It was Chelli who had all the information about the Perazzos.

Wladimirovich could also call upon Babby, his roommate, an anarchist whose admiration for him was such that he stood ready to sacrifice his very life for his maestro.

Interrogated by a police team from Posadas, Wladimirovich admitted to being the instigator and sole author of the attack. When the police allowed him to talk to Babby, he told his confederate to drop the story about “José the German” because he had already confessed.

Quite unintentionally, Boris posed a legal problem.[9] His case proved so interesting that, while he was being held in isolation, the Interior Minister and several parliamentary supporters of Yrigoyen eager to get to know him better visited him. As the minister left the prison, he told the media that “the prisoner responded with serenity to the many questions put to him.” All of which left the investigating magistrate seething with indignation. He was against the high-ranking official and the deputies’ visit, and raised objections, reminding them that the accused was being held in isolation and therefore denied visitors.

Argentine judges at the time were particularly severe with anarchists and with simple strikers. For example, one employee of the Gath and Chaves company was sentenced to two years in prison for having issued a call for a strike outside a store. Workers were sentenced to eight and ten years in prison for thumping a scab. And they weren’t sent to some sort of ladies’ finishing school: the shadow of penal servitude in Ushuaia hung over any who departed from society’s prescribed norms. Although he was the president, Hipólito Yrigoyen never meddled with the internal regimen of institutions, which thus enjoyed utter impunity: this was as true of the army (as evident in the Tragic Week), as of the police (in their hinting at subversion), and the Argentine Patriotic League (a particularly thuggish para-military organization ardent in its defense of the rights of property (and run by Manuel Carlés, Admiral Domecq García, and doctors Mariano Gabastou and Alfredo Grondona), operating as a de facto defensive/offensive organization.

So we can imagine the fate that awaited the failed expropriators. Especially Babby, the cop-killer. The Jockey Club wasted no time in launching a subscription for the family of “the police victim of an anti-Argentinian gang,” and raised 2,010 pesos on the very first day. (This was 1919, remember!)

La Razón challenged Wladimirovich’s story about the money from the attack being destined to finance a newspaper. According to La Razón, his aim had been to buy the materials for bomb making. For its part, Crítica described them as bandits reminiscent of the “Bonnot gang,” the French anarchists who attacked banks in France and Belgium at the turn of the century.

Before the court, the prosecuting counsel, Doctor Costa, asked for the death penalty for Babby, fifteen years for Wladimirovich, and two years for Chelli.

After the convicts had spent many a long month in solitary confinement in La Penitenciaria,[10] the judge, Martínez, reduced Babby’s sentence to twenty-five years in prison, Wladimirovich’s to ten years, and Chelli’s to one year. On appeal, the prosecution asked that the original sentences be reinstated, but the judges, taking things even further, passed death sentences not just on Babby but on Wladimirovich as well.

This sentencing was hotly debated. The anarchist newspapers stated that this was a case of “class vengeance” on the part of the bench. Legal circles were shocked by the sentences: Babby’s was regarded as fair in that he had fired at police officers and killed one of them, but Wladimirovich had not used any weapons. Based on what he said, this was the line taken by the trial judge: “Every criminal must answer before the court for his misdeeds and their consequences. This is why Wladimirovich cannot be charged with acts for which Babby bears the responsibility—the killing of officer Santillán and the wounding of officer Varela—insofar as there was neither connivance between them nor any complicity on the part of Boris Wladimirovich.”

By contrast, the appeal court put forward the following argument: “The court would like to point out that the accused fostered a conspiracy, a criminal association punishable under Article 25 of the Penal Code. Although not a direct participant in the murder of Officer Santillán, Boris Wladimirovich shares in the responsibility for it, for the law’s view is that there is implicit solidarity in the crimes of conspirators and it deals likewise with accomplices and perpetrators.” As for the reduction of the “sentence requested by the prosecutor, the court would like to point out that the application of the law falls within its remit, both in cases where the accused presents an appeal and in those where the prosecution decides against that, and thus in no instance may the court’s powers be restricted.” Ricardo Seeber, Daniel J. Frías, Sotero F. Vázquez, Octavio González Roura, and Francisco Ramos Mejía endorsed the sentences, but two appeal court judges, Eduardo Newton and Jorge H. Frías, dissented and voted to confirm the court’s original sentencing. It was this discord that enabled Babby and Boris to cheat death, because the court was obliged to declare that: “Given that it may not impose the death penalty upon the accused, insofar as Article 11 of the Code of Criminal Procedure requires unanimity of the court, the court sentences Andrei Babby and Boris Wladimirovich to life imprisonment.”

When Boris was told his sentence, he remarked, without the slightest affectation: “The life of a propagandist of ideas such as myself is at the mercy of such contingencies. Now and in the future. I am well aware that I shall not see my ideas succeed, but others will sooner or later take up the baton.”

But the life of the erstwhile biology teacher from Geneva did not include any provision for a future. A few months later he was deported to remote Ushuaia, hand-cuffed with a squad of common criminal prisoners. Though he had risked banishment to Siberia in the past, it probably never occurred to him that he might some day wind up in such a desolate region, such a ghastly penitentiary, and in such a distant land.

In prison, his health, which hadn’t been good to begin with, deteriorated rapidly. His end was near, and it was hastened by poor food, cold, and the beatings that were the daily fare of those dark days in the penitentiary. Despite this, people who met Boris in Ushuaia reported that he continued to peddle his ideas among the inmates, and before he died he instigated a feat that brought his strange face back to the newspapers (La Razón described his appearance as “queer, sinister, and Gothic”). He was the “brains” behind the anarchists’ revenge on Pérez Millán, a Patriotic League member who had killed Kurt Wilckens in a bloody incident after the killing of 1,500 in Patagonia.[11] For his own protection and in order to spare him from the sentence such an offence would have merited, Pérez Millán was passed off as insane and was sent to the insane asylum in Vieytes Street. Revolted by Wilckens’s killing and having discovered that Pérez Millán had been committed as insane to the Vieytes asylum, Boris Wladimirovich set about faking a nervous breakdown of his own, degenerating into complete madness in Ushuaia. He knew that mental cases from Ushuaia were transferred to the criminal cells in the Vieytes asylum, and contrived to ensure that this was the case with himself. Once he’d arrived at the Vieytes asylum, however, he was taken to a different wing from Pérez Millán, who enjoyed privileged treatment in a special little wing. Thanks to the Buenos Aires anarchists, Boris got hold of a revolver and passed it to Lucich, an inmate who enjoyed free access to all areas. With his powers of persuasion, Boris convinced Lucich to avenge Wilckens by killing Pérez Millán, which Lucich duly did. For the anarchists, this revenge was a question of honor—so much so that those in the know about Boris’s part in Pérez Millán’s death hailed the one-time Russian aristocrat as a hero of their movement.

Boris’s involvement triggered further maltreatment, which quickly brought about his death. In his later years, both of Boris’s legs were paralyzed, and he had to crawl if he wanted to leave his cell: a character from Dostoyevsky who met a Dostoyevskian end, like someone out of The Insulted and Humiliated or The House of the Dead.

This singular initial eruption of expropriator anarchism in Argentina triggered a long debate that lingered through the entire period when anarchism was active in the country: should there be support for those who resort to “expropriation” or crime in order to support the ideological movement? Or should they be repudiated as discreditable to the libertarian struggle? The intellectuals (mainly those around La Protesta) and the anarcho-syndicalists (from the 9th Congress FORA) were strictly opposed to political crime as well as to violence when the latter relied upon recourse to bombs and outrages against individuals. By contrast, the activist groups that advocated “direct action” (the mouthpiece for which was La Antorcha from 1921 onwards) and the non-aligned trade union bodies offered moral support to any act, no matter how illegal, directed against “the bourgeois.” Furthermore, from 1921 and 1922 onwards, the few anarchists who backed the Russian revolution were well and truly let down by it. The slaughter of black flag supporters by the red-flagged commissars of the new socialist republic—built upon the ruins of the tsarist empire—the deportations and imprisonment of anarchist ideologues who had flooded into Moscow from all corners of the world, had turned the mighty phalanx of working-class anarchism and its thinkers against Lenin and his supporters.

In Argentina, all genuinely anarchist publications lashed the Communist regime and the capitalist regime alike: They were two identical dictatorships, they wrote, different in terms of the ruling classes involved, but they both robbed the people of its freedom. The only contacts between Communists and anarchists in Buenos Aires came through the Italian Anti-Fascist Committee made up of exiles of every persuasion to be found in the Italian peninsula. It embraced liberals, socialists, anarchists, and Communists, and together they organized meetings addressed by a speaker from each tendency, which caused grave disagreements to break out between the anarchists. Many of them argued that they could not share a platform with the persecutors of their Russian colleagues.

It was the Italian anarchists most against collaboration with the Communists within the Anti-Fascist Committee who became the two leading figures of expropriator anarchism in Argentina: Miguel Arcángel Roscigna and Severino Di Giovanni.

The Communist mouthpiece El Internacional denounced every bomb outrage and every attack and robbery carried out by the anarchists from the “expropriator” faction.

On May 2, 1921, there was an attack on a customs post in Buenos Aires. The raiders got away with a considerable amount of money for those days—620,000 pesetas—but because of a blunder by their driver, Modesto Armeñanzas, the perpetrators were soon found. All but three of them fell into police hands. In the course of their raid, a customs officer had been killed. Of the eleven culprits, three were professional criminals, while the rest were workers who had never broken the law before. Contrary to what certain newspapers may have argued, none of them was an anarchist, although the raid had reignited the controversy among anarchists themselves regarding approval or disapproval of any crime committed against the “bourgeoisie.”

Within a few days, Rodolfo González Pacheco entered the fray when he wrote in an editorial entitled “Robbers” in La Antorcha:

Since it has been demonstrated that property is theft, the only robbers in these parts are the property owners. But what remains to be seen is if those who rob them are not of the same ilk as those they rob, and do not have a true robbers’ mentality, the same penchant for acquisition. Let us state that we have no prejudice regarding either of them. Especially as such a prejudice would protect the former even more than they are protected already. Because the former shriek: “Stop, thief!” just the way they shout “Fatherland and Order!”, their sole aim is to conceal all their thieving behind all this verbal brouhaha. Just like the highwayman who fires a shot to strike terror, and exploits the chance to strip you of your belongings.

No, no, and no. What is happening, in reality? What is the robber’s object? To seize wealth, or at any rate to avoid the toil and the slavery that flow from it. In order to escape enslavement, he gambles his freedom and generally loses it, in that the bourgeoisie are experts in this little game and, really, it is they who deal the cards. Should some petty thief succeed in this game, he becomes rich, a property-owner—which is to say, a big thief.

But for all that, and although they may all be thieves, we are more on the side of the outlaws than of the others, more on the side of the petty thieves than the big ones, more with the customs post raiders than with Yrigoyen and his ministers. May their example prosper!

The expropriator (or illegalist) anarchist group in Argentina arose from the necessity of organizing self-defense. For it was not just the army that cracked down on anarchist activities (Tragic Week, the farm laborers’ strike in Patagonia, the dock strike in 1921, etc.) nor just the police (who specialized in combating agitators, arresting ring-leaders, monitoring and breaking up meetings, breaking strikes). There was also, and above all, the nation-wide activity of the Argentine Patriotic League under Carlés’s leadership. In those days, not a week passed without some bloody confrontation between anarchist workers and members of the Organization for the Defense of Property, operating under the aegis of the Patriotic League.

The Patriotic League was not merely powerful in the capital, but it was powerful in the interior as well. There, under Carlés’s leadership, the landowners and their sons formed themselves into armed phalanxes and underwent military training so they would be prepared to defend themselves against the persistent agitation of the farmworkers. Clashes were inevitable and the one in Gualeguaychú on May 1, 1921 ended in out and out tragedy.

That day, the Patriotic League held a massive demonstration—to counter the workers’ planned celebration—with a huge procession of mounted gauchos, representatives of the region’s Catholic schools, fifty-meter-long Argentinian flags, young girls scattering flowers before the League’s burly young men… This demonstration reached its peak with the arrival of Carlés. In frock coat and bowler hat, he climbed out of a biplane that had brought him from Buenos Aires.

Once this High Mass of patriotic display had ended, the gaucho cavalry, under the command of the rancher Francisco Morrogh Bernard, made for the central square in Gualeguaychú where the labor rally was in progress and where both a red and a black flag were flying. At the sight of those emblems, Carlés’s men’s patriotic blood boiled over. They pounced on the ramshackle proletarian platform and on the three thousand participants. It was carnage. At first, it was believed that five workers and died and thirty-three were seriously wounded. The anarchist press tripled these figures, while the official press minimized them. La Prensa tried to explain the episode away by arguing that “95% of the victims were not Argentinians. So one can imagine what sort of labor gathering had taken place, during which anarchists must have violently assailed our nation’s symbols. Only 20 to 30 members of the Patriotic League were involved in the incident. Initially, probably in haste, the police claimed that the workers were not armed.”

The following day, two carloads of youths from the Patriotic League attacked the premises of the Drivers’ Union in the capital. Two anarchist workers were killed: the Canovi brothers. And three or four days later there was a gunfight at the docks—where the dockers had gone on strike—during which an anarchist worker and a member of the Patriotic League lost their lives.

The violence was escalating, and in their publications the anarchists called for armed resistance to any League attacks and went so far as to advocate “attacking it on its home ground” if necessary.

In the 1920s, it was increasingly difficult to secure a peaceable society. Anarchists bragged about carrying guns—and it’s true that they were not shy about using them. One need only cite the Jacinto Aráuz incident where, for the first time in history, a gunfight erupted inside a police station between anarchists and the police. In that case, the farmworkers in the area were living in fear because their rights were being trampled, and anyone who dared protest was replaced by imported labor. The local police inspector could think of no better solution than to invite all parties concerned to the station “for discussions and to come to an agreement.” Some workers took up the invitation—among them several delegates influenced by Bakunin’s theories—and on their arrival, they were invited to go on through to the station yard, which they were startled to find ringed by armed policemen. There was still no sign of the inspector, and two sergeants began to call the workers one at a time, steering them down a corridor before disarming them and handing them over to other police. They were then made to lie down on the ground and were beaten with clubs. A pretty drastic way of resolving a labor dispute.

But the anarchists who were still in out in the yard and who were assuredly no choirboys themselves opened fire even though they were surrounded. It was a real bloodbath with fatalities on both sides.

From that day forth, Jacinto Aráuz became a symbol for all Argentinian workers. It was, so to speak, an application of the old proverb “what’s good for the goose is good for the gander.”

Of course, certain anarchists overdid things a bit by always carrying a gun everywhere they went. As it happened, their own publications were moved to openly offer them advice, as in this announcement of a picnic outing to Rosario, carried by La Antorcha: “To Rosario, big family picnic to benefit political prisoners, to Castellanos Island on the River Paraná. Gentlemen $1.20, Ladies 50¢, Children free. Note. Let it be known that the sub-prefecturate will be checking passengers before they board, so carrying weapons on one’s person is not recommended.”

Or indeed this insertion on the front page of La Protesta: “Concerning the Sunday picnic: as is, alas, the custom during La Protesta-organized picnic outings, shots have been fired into the woods on Maciel Island in the course of the day and particularly as night fell. This is very dangerous and has panicked some families along on the picnic, which should be a pleasant gathering by anarchists in a spirit of open comradeship. We have had complaints from several participants in the picnic, and even from a fisherman living on the island. All were almost hit by a stray bullet during one of these many shooting sessions. Comrades must avoid firing revolver shots into the woods and impress upon trigger-happy amateurs the danger they are posing. They display utter lack of know-how with these dangerous games, and it is incumbent upon anarchists to oversee the proper progress of our activities and, above all, the safety of all who demonstrate their trust in us by taking part in them. Consequently we urge comrades not to shoot during our picnics and to prevent any participants who may not have read this notice from indulging in the game.”

It would appear that this friendly gunfire was a well-established practice, for the newspaper concerned carried the notice for several days in a row.

There were countless instances of clashes between workers of differing persuasions in the workplace; of workers’ acts of revolt against foremen or employers, which then degenerated; of wage earners taking on the police and members of the Patriotic League. Let us cite, for example, the case of Pedro Espelocín—who later became an active member of the anarchist expropriator movement—who killed a foreman caught in the act of mistreating a child. There is a long list of political prisoners sentenced for crimes connected with social and political strife, and these ranged from simply striking to homicide. The Social Prisoners’ and Deportees’ Defense Committee, maintained by the modest contributions from anarchist workers, was unable to fully meet its remit, which was paying the defense counsel fees and the trial expenses of the accused, and also looking after their families. But this commission did not have only a passive role that might be summarized as raising funds, much as some sort of Salvation Army or society of patronesses might: there was also its secret brief to help prisoners escape. To that end, it mobilized all sorts of resources, including sending “trusted comrades” on missions, circling prisons for (sometimes) months on end so as to gather comprehensive intelligence, renting houses, getting hold of getaway cars, bribing jailers and court ushers and even the clerks to do what they could about sentencing.

The man in charge of it all was the secretary of the Prisoners’ and Deportees’ Defense Committee —Miguel Arcángel Roscigna, an anarchist metalworkers’ leader. While the ideologues of La Protesta and La Antorcha were pointing out in their columns that prisoners’ freedom ought to be secured only by means of strikes or by mobilizing the masses of the people, Roscigna was a man of action sufficiently cunning to thwart the plans of the police and courts. He was a cerebral, cool, scheming sort. But when action was called for, he was the one who took the bull by the horns, not just by leading, but also by springing into action. He had demonstrated this already in the Radowitzky case: he had patiently and adroitly made overtures so that he might be appointed a prison guard in Ushuaia. There he was to prepare everything in fine detail so that this time the escape attempt would not fail. Just as everything was in place, a blabbermouth at the congress of the Argentine Union of Trade Unions, made up of socialist and trade unionist leaders, hell-bent upon doing the anarchists damage, disclosed that Roscigna was ‘working as a “dog” in Ushuaia prison’ (“dog” being the affectionate nickname that anarchists used for prison guards and policemen). Inquiries were made, and the police discovered that Roscigna was indeed on Tierra del Fuego. He was immediately sacked and driven from the prison. Before he vanished and lest all his trouble should have been for nothing, Roscigna torched the prison governor’s home.

Later it was Roscigna who orchestrated the initial escape of the baker Ramón Silveyra who had been sentenced to twenty years in prison. And laid the groundwork for Silveyra’s second breakout. Those two genuinely sensational events demonstrated his real flair as organizer—a flair that he later demonstrated in the preparation of sensational attacks and in direct action operations.

The relentless war being waged between the two anarchists factions, the protestistas and the antochistas, the right- and left-wings of the movement, became so frenzied that the Defense Committee split into two factions, each championing its own prisoners. The factions close to La Protesta and the 5th Congress FORA would support only anarchist prisoners of conscience, whereas the one close to La Antorcha was to leap to the defense of all prisoners accused of criminal offenses (which is to say, the anarchist expropriators). And that is what happened in the highly controversial case of the Viedma prisoners.

In 1923, in the Río Negro region, a mail coach was attacked, just like in the Wild West. The territorial police arrested five anarchist farm laborers not too far from the scene as they were collecting firewood for an asado.[12] Under atrocious torture, they confessed to the attack. One of them, Casiano Ruggerone, was driven mad as a result of the torture and died a few months later in the asylum in Vieytes. The other four were sentenced to a total of eighty-three years in prison. Andrés Gómez got twenty-five years, as did Manuel Viegas and Manuel Álvarez, whilst Esteban Hernando got eight years.

The faction close to La Antorcha waged a protracted campaign to have the case reviewed. La Protesta, having shown itself lukewarm in their defense wrote in its columns that the Viedma prisoners “are ordinary offenders who have nothing to do with anarchist propaganda and anarchist ideas.” This inflamed the polemic within the movement, a polemic that was to linger for as long as anarchism played a role of any significance in Argentine labor life. Moreover, it has been a constantly recurring theme in anarchism: since Proudhon and passing through Bakunin, Reclus, Malatesta, Armand, Gori, Fabbri, Treni, Abad de Santillán. How many have queried whether all means are legitimate in the making of the revolution, or whether anarchists should cling to the image of pure and irreproachable figures who make the revolution by preaching a humanistic ideal?!

Little by little, events brought the two schools of thought into grave paradoxes, in, say, the Sacco-Vanzetti affair—a case of injustice that, in terms of the worldwide labor mobilization it provoked, had a greater impact than the Dreyfus Affair in its day.[13]

What happened to Sacco and Vanzetti? Almost the same thing that happened to the Viedma prisoners, except that in the latter case, what we today would describe as “public opinion” was not a factor. By contrast, Vanzetti and his Italian anarchist comrades in the United States managed to make masterly use of popular opinion over more than seven years of a worldwide popular agitation, which will probably never be equaled. In the United States itself, the agitation was on a scale ten times that of the agitation that would subsequently lead to the end of the Vietnam War.

In the Sacco-Vanzetti case, there was unanimity between everyone, individualist anarchists, anarcho-communists, anarchist expropriators and devotees of violence, social democrats, Communists, liberals, the Pope, and even the fascists who “endorsed the judge’s decision to suspend the death sentences on the accused.”[14]

Once arrested—fifteen days after the Braintree hold-up and the killing of two cashiers—Sacco and Vanzetti said that they had been indirectly implicated in the raid. Their confessions had been made on the advice of their lawyer who believed that this would save them from deportation to Italy, which would also be their immediate fate should they confess to being anarchists. To put it another way, in their case there was none of the physical torture used on the Viedma prisoners, but rather pressure and mental torment: either they accepted the legal niceties or they would be extradited. And despite support from all over the world this was an interminable bluff that they were fated to lose after seven long years.

The courts disgraced themselves by sentencing Sacco and Vanzetti to the electric chair. At no point were the US judges able to demonstrate with clarity that the two Italians were guilty. There were only legally worthless and inconclusive suggestions and testimony. It goes without saying that what tipped the scales, above all else, in the sentencing was the fact that the accused were anarchists. It was the same in the Viedma prisoners’ case. As for Sacco and Vanzetti’s guilt or innocence, we will never be able to pronounce on that with certainty. On the other hand, there is no denying that they were members of a pro-direct-action group. L’Adunata dei Refrattari was the mouthpiece of the New York Italian anarchists, to whom we are largely indebted for the launching of the mammoth worldwide campaign that sounded the alarm. This was a newspaper unambiguous in its support for direct action. So much so that a few years later it would support Severino Di Giovanni and his colleagues who were to be either ignored or damned in Argentina. The last word on the Sacco-Vanzetti case might well be that delivered by the journalist and writer Francis Russell in his painstaking investigation entitled Tragedy in Dedham (published in 1962 and hailed as a serious study by the entire European press). Francis Russell reckons—and James Joll shares this view—that Sacco was a dyed-in-the-wool “expropriator” and went in for that sort of thing as a means of raising funds for the cause. And the likelihood is that he and Vanzetti—who was always welcoming towards the persecuted, without asking whether they were expropriators or not—were framed because they were dangerous agitators.

But there was nevertheless a hiccup in the support that anarchists gave Sacco and Vanzetti. Should they be defended as innocents or because they were anarchists? And, if they actually were guilty of hold-ups designed to finance propaganda or to help prisoners and strikers, would they have had the same championship from the columns of the “official journals” of Argentinian anarchists? The same dilemma recurred with Buenaventura Durruti’s exploits in Argentina.

On October 18, 1925, three persons slipped “movie-style,” as La Prensa put it, into the Las Heras tram depot in Anglo, smack dab in the middle of the Palermo district. One of them wore a mask. The cashiers had just finished counting the money from ticket sales. “Hands up!” the shout rang out in a strong Spanish accent before the money was demanded. The stammering employees explained that the cash was already in the safe. The key was demanded, to no avail, as the manager had left and taken it with him. The raiders conferred with one another and withdrew. As they slipped past the cash-desk, they grabbed a small bag that a guard had just set down. It held 38 pesos, in ten-centavo coins. Waiting outside, was an accomplice and, a little further off, a car was waiting. They vanished without a trace.

The man who had just spearheaded this fruitless raid, which netted only 38 pesos in small change (which was obviously a disappointing result for the raiders who had acted with mathematical precision, but overlooked one tiny detail), was none other than Buenaventura Durruti. The same Durruti who, eleven years later, became the most legendary personality of the Spanish Civil War, the unchallenged leader of the Spanish anarchists and libertarians from around the world who came to defend the Republic against the Francoist rebels. Durruti, commander of a column of the same name, who came from Aragon to rescue Madrid, and who, with his three-thousand poorly trained militians, defeated an entire disciplined army complete with staff officers and uniformed generals who had made a study of tactics, strategy, and command.

This gunman with his 380 ten-centavo coins was the man who, after he perished in the “University City” in Madrid, had the most grandiose funeral ever bestowed upon any workers’ leader in Spain. James Joll said:

Durruti’s death robbed the anarchists of one of their most celebrated and ruthless heroes. His funeral, held in Barcelona, was the last great anarchist show of strength, drawing two hundred thousand militants who paraded through the streets of the city. One would have thought one was at the demonstration played out in Moscow fourteen years earlier when the funeral of Kropotkin offered the Russian anarchists their last chance of a public show of strength, before the Communists wiped them out.