Bibliography of books and articles was omitted for this upload.

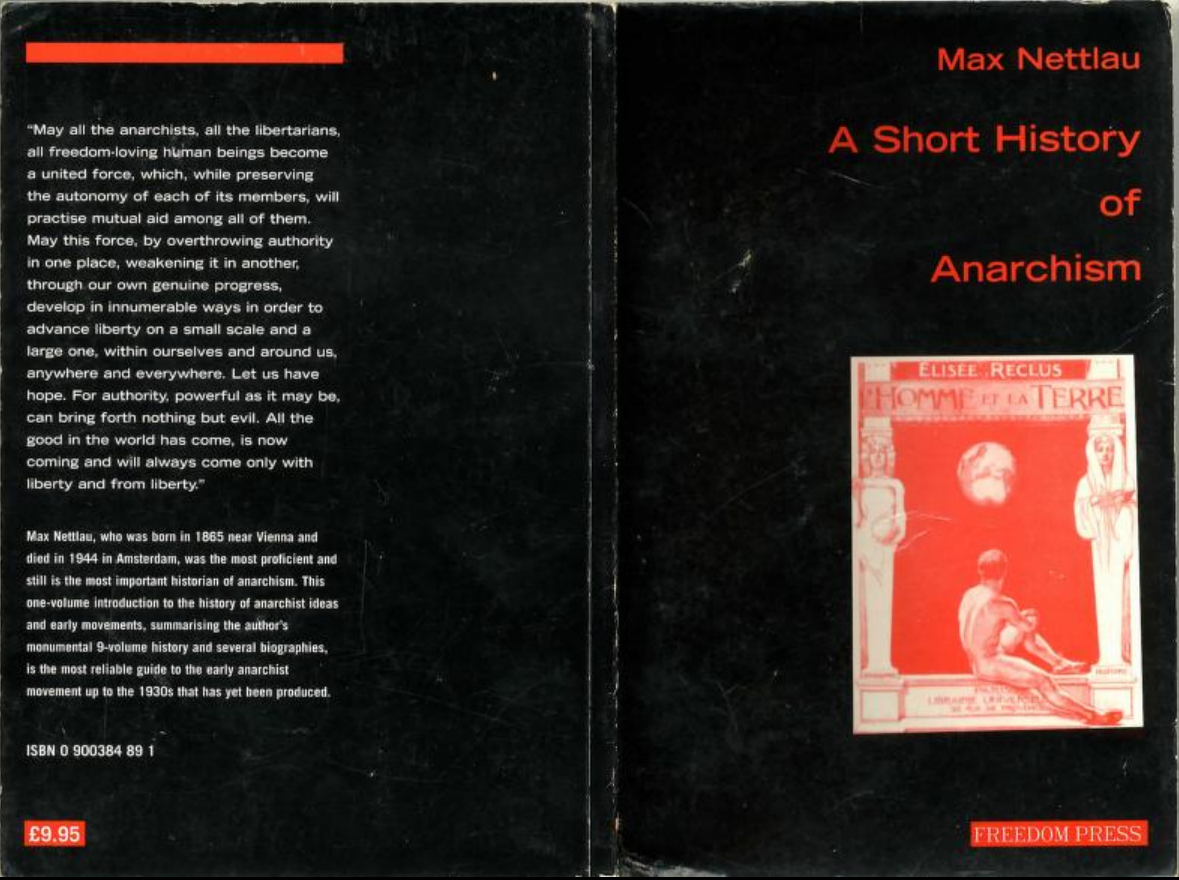

Max Nettlau

A Short History of Anarchism

1. Liberty and anarchism: its earliest manifestations and libertarian ideas up to 1789.

4. Proudhon and Proudhonism in different countries, in particular in France, Spain and Germany.

5. Anarchist ideas in Germany from Max Stirner to Eugen Dühring and Gustav Landauer.

10. The anti-authoritarian International until 1877. The origins of anarcho-communism in 1876-1880.

12. Italy: Anarchist communism, and its interpretation by Malatesta and Merlino.

15. Anarchist and syndicalist movements in the Netherlands and in the Scandinavian countries.

16. Other countries: Russia and the East; Africa; Australia; Latin America.

Preface

This English translation of Max Nettlau's Spanish text of 1932-34 was made by the late Ida Pilat Isca, and its publication was financed by a donation from the late Valerio Isca. The translation was first edited by David Poole and Carol Saunders, and later revised and compared with the original. Much of the production work was done by Stephanie Cloete.

Bibliographical references have been completed where appropriate and integrated into appendices following the text. Biographical and other information has also been integrated into the index.

Heiner M. Becker

Introduction

Max Nettlau 1865 – 1944

The person

Max Nettlau was an anarchist for more than sixty years, and for some fifty years he took an important part in the anarchist movement, as a writer, chronicler, historian, often argumentative critic and active supporter. And still, strange as it may sound, he is virtually unknown not only to ‘the outer world’, but also to many anarchists. This is all the more surprising, for not only was he the pioneer in the field of the historiography of anarchism (and in anarchist historiography!, if there is such thing), but even more so because fifty years after his death, in many of the fields he wrote about, he has still not been superseded by later writers.

Max Heinrich Hermann Reinhardt Nettlau was born on 30 April 1865 in Neuwaldegg, then a suburb but now a district of Vienna. His parents were both Prussians; his father Heinrich Hermann Reinhard Nettlau (29 Dec. 1830 Schlodien, Prussia — 6 March 1892 Neuwaldegg) came to Austria as Court Gardener to the Princess Schwarzenberg in January 1858. He met his wife Agnes Kast (11 May 1843 Potsdam —25 May 1898 Potsdam) during a visit in Prussia in 1862 and they married in July 1864. Max was their first child, followed by one other son, Ernst, born in December 1866, who was after a few years discovered to be mentally retarded. As may be gathered from the discretion with which Nettlau usually avoided this subject, it seems to have been the only dark cloud in an otherwise unusually happy and harmonious childhood. For Nettlau appears to have been often somewhat jealous of his brother, who soon got more attention and care than he — though Ernst was already in 1872 committed to professional care. But in many ways Nettlau remained withdrawn and rather solitary, enjoying the magnificent gardens of the Palace in Neuwaldegg, for which his father was responsible, and playing on his own, in the company of a few animals, especially birds, plants and trees. His outlook on the world always remained deeply influenced by these early experiences: comparison with the life of plants, trees and animals, to what he regarded as a truly natural environment, very often provided the standards against which he measured political phenomena. It was here also that he developed his idea of an ideal society and an ideal life, of a natural life, of Anarchy: a world which grows and regulates itself on its own and in which one should interfere as little as possible, lest the results would become some caricature like the unnatural and artificial French Palace gardens.

The first years of his life were also the time when Bismarck prepared, not least at the expense of Austria, by wars and annexations, the foundation of the German empire (which in Austria, but also by many in Germany!, was regarded as a Prussian empire). Though he was then too young to notice what was happening, Nettlau must in his first ‘conscious’ years have been constantly confronted with these political events and their consequences. It is in many ways significant that like his parents he kept his Prussian (then German) nationality all his life, and always refused to apply for Austrian citizenship — though for most of his life he would have described himself as a Viennese Internationalist.

The education he received from his parents, especially his father, seems to have been unusually liberal, generous and free-minded; as Nettlau always recalled, virtually no reproaches were ever made, and certainly no beating or other physical punishment. Thanks to his father also, he liked reading from very early on; having no religious education at home, and a liking for Greek and other mythologies, he decided, when confronted at school with Christian religion, that a world with so many competing gods couldn’t make sense, and that it was therefore probable that there were none. His father’s tales and recollections, especially about and around the revolutions of 1848/49, impressed him deeply, and this and the reading of Heine and Börne made him an adherent of “radical-revolutionary republican, always federalist opinions, yet untinged by socialism” early in life.

Digesting Heine and Börne and being confronted, in the late 1870s, with reports of the activities of Russian revolutionaries — which were received and commented on by the press outside Russia with much sympathy — he began from about 1880 to regard himself as a socialist: always “antistatist and federalist (that is, as libertarian as possible), libertarian-communist (free and unforced solidary work by all, and consuming as one liked) and, in view of the resistance by the beati possedentes [the ‘haves’], revolutionary (individually and collectively)”. He soon discovered that this coincided with anarchist communism, and from about 1881/1882 he regarded himself as a communist anarchist.

From Autumn 1882 he studied philology in Berlin. He soon became interested in comparative Indo-European philology, and concentrated on “the darkest branches of this group of languages, the Celtic languages, with a special preference for the Cymric (the Welsh)”. Working on his doctoral dissertation, he went to London for the first time in October 1885 and immediately joined the Socialist League (the only organisation he ever joined). He always regarded the League as the ‘ideal’ political organisation, with its concentration on education and the progressive development of political consciousness. Living at the time just off Tottenham Court Road, he registered at the Bloomsbury branch, then more and more the centre of Marxist intrigues against the anti-parliamentarian policy of the League; he claimed later that it was this “workshop in practical Marxism” that facilitated his understanding of the Marxist intrigues in the First International.

Early in 1887 he finished his dissertation: Studies on the Cymric grammar, and published its first part.[1] He continued to work in the field, expecting to embark eventually on an academic career, and therefore continued to spend regularly longer periods in London and other places in the United Kingdom, to use Celtic manuscripts and other pertinent materials. He continued also to take part in the Socialist League, in London, but also, during a longer visit in the Spring of 1888, in Dublin (where he met for the first time the later notorious police spy Coulon). At that time he also published his first political and historical articles, in the paper of the Socialist League, The Commonweal. The very first was on Karl Marx, to commemorate the fifth anniversary of his death (10 March 1888, signed Y Y); others were usually International Notes or historical notes for the Revolutionary Calendar.

In July 1889 he attended the Founding Congress of the so-called Second International, the International Socialist Congress in Paris, as delegate of the Norwich branch of the Socialist League (as “Netlow”, thanks to a misunderstanding of William Morris). He began also in these years more regularly to interview old militants in the English and other revolutionary movements, and to discuss political matters with them, and usually took shorthand notes either at the time or immediately afterwards. He was particularly close to Samuel Mainwaring (14 Dec. 1841 Neath (S. Wales) — 29 Sept. 1907 London), one of the founders of the Socialist League, whom he had originally met to obtain information about the Welsh language and whom he always regarded as one of his best friends, and to the Belgian anarchist Victor Dave (25 January 1847 Alost, Belgium — 31 October 1922 Paris), a member of the First International and former friend of John Most.

At the Conference of the Socialist League in May 1890 he was elected a member of its Council (he resigned in September when he had to return to Vienna); and between May and August 1890 he edited and financed The Anarchist Labour Leaf, a little four-page-sheet, of which four numbers were published and distributed gratis. It consisted entirely of articles by Nettlau and Henry Davis, who up till then had been one of the most active anarchist-communists in the Socialist League — mostly in the East End. Davis soon changed colours and declared himself an Individualist, which prompted Nettlau’s first contribution to Freedom (“Communism and Anarchy”, May 1891; signed N). He also wrote his first longer and more substantial historical articles — “Joseph Déjacque — a predecessor of communist Anarchism” (published in John Most’s Freiheit, 25 January — 25 February 1890), and “The Historical Development of Anarchism” (Freiheit, 19 April — 17 May 1890, reprinted as a pamphlet), the nucleus of his later historical works, and the first results of his studies on Bakunin, “Notes for a Biography of Bakunin” (Freiheit, January-April 1891). These already showed, as he later stressed, what subjects would be his preferences as a historian: the forgotten predecessors (Déjacque), biographies (Bakunin), and the overall view (history of an entire movement). Other long articles concerned the Austrian labour movement, German Social Democracy, “scientific socialism”, and anarchist communism.

On 6 March 1892 his father suddenly died, and Nettlau discovered to his great surprise that his father had left his family a small fortune, accumulated thanks to a number of “fortunate speculations”. He found himself unexpectedly in a position where he no longer needed to prepare himself for an academic career, and could concentrate on what had become more and more important, the study of the history of socialism in general, of anarchism and of Bakunin in particular. He saw from nearby that in a few years many of the older militants of all the radical movements of the mid- and later nineteenth century had died or were about to die, and that their sometimes magnificent collections of books, documents etc. were dispersed or disappeared (not to mention their recollections which he had already started to record from the late 1880s). He therefore decided that it was “more important” to save what could be saved in this field, instead of “using old manuscripts in libraries in Wales and Ireland”, and gave up his Celtic studies. (He had started to collect anarchist materials, but on a much more modest scale, in the late 1880s, and had bought and saved the archive of the Socialist League, which its secretary Frank Kitz had torn up and prepared for destruction).

From then on he travelled extensively to meet and interview survivors of Bakunin’s circle (and of other revolutionary movements), and he spent a considerable part of each year in London, where he not only collected what he could find and obtain around some of the Working Men’s clubs, but also for a while took an active part in the life of the anarchist movement. He was a member of the London Socialist League (which continued the Socialist League for a while), and of its successor, the Commonweal group. He wrote their declaration of principles, Why we are anarchists,[2] and a little later he wrote at the request of the remnants of the group and some other comrades An Anarchist Manifesto, approved of and occasionally corrected by Kropotkin, also published anonymously.[3]

On 28 February 1895 his brother Ernst died, and he found — as he was administering his father’s estate — that he could increase his monthly allowance and spend more on collecting. After the merging of the Commonweal and Freedom Groups in April/May 1895, like most he joined the Freedom Group, and when The Torch was closed down, he and another German and good friend of Kropotkin, Bernhard Kampffmeyer (25 June 1867 Berlin — 21 Oct. 1942 Berg.-Gladbach), provided the means to acquire the press and printing equipment of the Torch for Freedom and ‘the movement’ and guaranteed half the rent for its premises at 127 Ossulston Street (Spring 1896).

In Spring and early Summer 1896, he prepared with Joseph Presburg (‘Perry’) the anarchist participation at (and possible alternatives to) the International Socialist Congress in London, July 1896; they also organised (with Malatesta) the anarchist meetings after the expected exclusion of the anarchists. He and Presburg were also in 1897 the “Spanish Atrocity Committee”, Nettlau doing all necessary translations, duplicating the circular letters on the machine he had acquired for the publication of his biography of Bakunin, and writing nearly all articles on the subject for Freedom, the Labour Leader, and other papers.[4]

In the Spring of 1896 he wrote his Bibliographie de l’Anarchie, published in Spring 1897. Between 1896 and 1900 he wrote and “autocopied” in 50 copies his huge biography of Bakunin; he continued to work on Bakunin intensively for the next few years, and was allowed to use the Bakunin papers which his family in Naples possessed (they were destroyed at the end of the Second World War). He also received, on the initiative of Élisée Reclus, the bulk of Bakunin’s political papers and manuscripts, for his collection and for safekeeping. At about the same time, James Guillaume —who had refused to help Nettlau with his work on Bakunin — destroyed most of what he had left of Bakunin’s letters and manuscripts (including what he had received so far from Nettlau’s biography of Bakunin), partly in a fit of depression, but partly also to suppress information he did not wish to become known. This concerned in the first place everything concerning the break between Bakunin and his formerly most intimate friends around Guillaume, in particular the manuscript of Bakunin’s Mémoire de justification — of which, however, Bakunin had a copy made before turning over the manuscript to his former friends, a copy that Nettlau found and could use, and years later also published. Nettlau summarised and reproduced his discoveries in four unpublished volumes of supplements to the Biography, which James Guillaume was the only other person to use, in preparing L’Internationale, his partial recollections and history of the First International.

On 5 December 1899 he read to the Freedom Discussion Group a paper which always remained one of his pet productions — Responsibility and Solidarity in the Labour Struggle.[5] From 1900 on he regularly spent several months every year in Paris (which he had avoided until then), to collect publications in the bookstalls on the Quais, but also to collect material for his next major project, a history of Buonarroti and the secret societies of the early 19th century — a subject he had chosen after being impressed by Bakunin’s fascination with and involvement in secret societies. He continued the work for several years and wrote an unfinished manuscript, which however is no longer preserved with his papers. He finally abandoned the subject, disgusted with what he saw as inevitable in all these secret bodies, a pitiless authoritarianism without any hint of understanding and tolerance.

Most of his time and energy in the years up to the First World War were dedicated to collecting and travelling; but he conducted, from 1900 until 1907, the only long-term relationship with a woman he had in his life. (His extreme need for discretion was such that he mentioned her existence only to a couple of female comrades, but with one exception to none of his male friends, who learned about her only after she died in 1907.) Otherwise he frequented prostitutes, from the early 1880s to the early 1940s, and in his later memoirs repeatedly expressed his gratitude for all the good they did him.

In all those years Freedom was the only paper to which he contributed regularly (from 1896 to 1914, and then again from 1919/1920 onwards), and in whose production he also participated in more practical ways, when he was in London. During this period he wrote most of the International Notes, all the Reviews of the Year (usually published in the January number), historical and general articles, obituaries, and many reviews, and he wrote for Freedom some of his most controversial articles (he was repeatedly asked to produce a provocative piece, to bring a too complacent movement to life again).

From its foundation in 1911, he also contributed regularly (including some of his most important historical articles) to the Archiv für die Geschichte des Sozialismus und der Arbeiterbewegung, which remains one of the most substantial journals on the history of socialism and the labour movement in general.[6]

At the end of 1912 he threatened to resign from the Freedom Group, when Alfred Marsh, the editor, suppressed an article by Varlaam Cherkezov on the situation in the Balkans, replying to Kropotkin and attacking the imperialist policy of Russia and incidentally Kropotkin’s Russian nationalism (Cherkezov was Georgian). He was finally persuaded to remain in the group and asked to explain some of the controversial issues in an article in Freedom, “The War in the Balkans” Jan. 1913).

The outbreak of the First World War found Nettlau in Vienna, where he remained during the following years. He took the side of Austria and Germany, it seems, mostly out of a violent opposition to Kropotkin and certain other comrades, but also, as he tried to explain to the only comrade with whom he remained in correspondence during these years, out of a sense of fairness. He suffered progressively from the more and more virulent nationalism or, as he saw it, even anti-German racism, especially in radical circles and on the left, which, he thought, had lost all sense of proportion and was not just uninformed but deeply unjust. He wrote later: “N. protested and was consequently regarded as a patriot, like in that Winter of 1912/13, when he refused to join in the glorification of the Balkan Allies, the new ‘Crusaders’ (...) There was no greater Russian patriot than Kropotkin, no greater Georgian patriot than Cherkezov, no greater Dutch and French patriot than Cornelissen, no greater American patriot than Emma Goldman, and he got along with all of them; he just refused always to understand why other countries should live, while Austria-Hungary and Turkey had to be dismantled.”[7]

Some of these feelings find an expression or at least an echo in the present book:

Marx, as attested by his writings published at that time and correspondence published later, was as anti-German as Bakunin, and he did all he could to foment a British war against Russia and Germany. He was in complete agreement, at the General Council in 1871-72, with the Blanquists, who were French patriots par excellence. Those among the German socialists who were in contact with the International were all Francophiles. Conciliatory manifestos were published by both parties. Nothing in the International could cause any offence to the French. But the very fact that a race considered superior (Latin) had been beaten by a race considered inferior (barbarians) was intolerable to passionate spirits. Their racial attitudes cannot be ascribed to a later interpretation... (Chapter 10, p.129).

It was also a question of fairness and justice to take a side in a situation, where both sides were more similar to each other than either admitted, and where none had more right than the other to the claim to be “progressive”. Basically his attitude remained as balanced as before, when it came really to evaluate the situation:

But I would wish that one should speak as a historian, as a critic and not as a fanaticized continuator of the hatreds of the past, sowing new hatreds. After all — what is more international than cruelty and wickedness? The English burnt Jeanne d’Arc, the French burnt the Palatinate, the Germans bombarded Strasbourg, and so forth. The history of the past is nothing but the oppression of the weak by the strong, and the history of our time is its worthy continuation; one is used to it to such an extent, that nobody pays attention any longer to the people murdered all around us. All parties, even the most advanced ones, do just the same; if they can, they kill their adversaries, by a revolutionary tribunal or by direct assassination; and if not that, then there are still the different forms and degrees of polemic. In this situation, either one closes one’s eyes before the crimes of one’s own country and fights all ‘the others, as pure and simple nationalists; — or one admits that on the whole everything is balanced, that people and parties are all the same if not in the good they do, then certainly in the evil they do, and one fights (apart from the crime of the hour, of course) the common source of evil, authority and all its forms, the State, the thirst for power, fanaticism in all its forms.[8]

The end of the war found him destitute and starving, having lost virtually all his money in the vicissitudes of the war and being on the side of the losers. He survived in the end only thanks to food parcels that occasionally reached him from friends in Switzerland, England (T. H. Keell), and America, and from Quakers and Quaker organisations in America — which (combined with the personal contact with some of these) made him for the first time somewhat more lenient towards religious people and some religious environments.

He now had to write for a living, and first could do so only for the Christian Science Monitor (reports on the situation in Vienna), until some anarchist papers were in a position to pay for articles and books (Der Syndikalist in Berlin, La Protesta in Buenos Aires, and Freie Arbeiter Stimme in New York in particular). For the rest of his life, he did virtually nothing else but writing — as he informed one of the friends who supported him:

Until today I wrote few letters, as I finished the manuscript only yesterday (...) it’s the history of the ideas 1880-1886 and should be called: Anarchists and Socialrevolutionaries... 1880-1886. But there is no prospect of it being published. I am tired, but have always to go on writing — articles — letters — then again the next book on the years 1886 to 1894, or rather the book-manuscript, the solitary book, just for me.[9]

The conditions under which he produced all this work were at first incredibly difficult, because he was separated from most of his own collections (including many of his earlier notes and excerpts), which were kept in store in London and Paris — and which were inaccessible to him also, because they were threatened by sequestration as property of an ‘enemy’ and loser. This changed somewhat from the mid-1920s onwards, when (on the invitation of friends who also paid the expenses) he could travel to Berlin and then to Zürich and Geneva again, where he could use the libraries and collections of friends (Rocker, Jacques Gross, Fritz Brupbacher) and of public institutions (including the Social Democratic Party archives in Berlin with the papers of Marx and Engels); and then in particular from 1928 to 1936, when he was invited to Spain by the Montseny-Urales family, and spent longer and longer periods there to use the rich collections of the Biblioteca Arús in Barcelona, of Soledad Gustavo, and of other anarchist collectors. In 1935 he sold his collection to the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, and concentrated in the final years before 1940 on helping to classify and catalogue his (and other) collections. He wrote less for the movement and its papers and started to transcribe his daily notes from the 1880s and 1890s and to write his definitive memoirs (he had previously written several other, shorter versions). From 1938 he lived continuously in Amsterdam, apart from a visit in Switzerland, and witnessed not only the annexation of Austria by Germany under the leadership of an Austrian-born naturalised German, but also the invasion of the Netherlands and the seizure of the Institute including the bulk of his collection. In 1940 he began to write the last version of his memoirs, some 6,000 pages carrying the story into the 1930s, but still not complete. The last pages, written in the last weeks of his life, chronicle mostly the progressive defeats of the German army. He died rather suddenly in Amsterdam on 23 July 1944 of cancer of the stomach.

Nettlau began as an ardent and rather intolerant anarchist communist; from the second half of the 1890s this progressively changed, not least through his experiences and observations in the anarchist movement in London and then Paris (he always kept aloof from the movement in Germany and Austria), and he developed his own brand of an open-minded “anarchism without adjectives”, which should tolerate also all the different forms of economic solutions in a future society, whether communism, collectivism, or mutualism, or whatever— everyone should have his right to his own corner and from there come to terms and agreements with others. Apart from his personal experiences as a participant and observer, he saw the nefarious consequences of sectarianism more and more also as a historian. In the 1920s, when he studied more anarchist publications than ever before, with the need to understand, analyse and evaluate the development of the movement and the progress or the decay of its ideas, he realised more clearly than before the sheer practical necessity of a basic tolerance and openness for the survival of the anarchist ideas:

Everywhere, the group which believed itself more advanced fought those anarchists it considered less advanced, and isolation grew, even among these same anarchists — a phenomenon that had nothing to do with either the libertarian idea or with solidarity but was the outcome of sheer arbitrariness and egocentrism. There was no question of the revolutionary ardour of these groups; we can only point out that by their posture of rigid intolerance they succeeded in narrowing their own sphere of action and their influence. (...) One and the other, the tactic of indulgence and the tactic of carping criticism, encouraged the growth of amorphousness and the tendency toward atomization which I have just discussed above. And since these ideas were considered more libertarian, and there was a desire to impose them upon others, they turned into authoritarian concepts, tending to make anarchism into a law; the advocates of these ideas not only despised those who did not share their opinions but fought them fanatically. (Chapter 11, pp. 150-151)

As a historian, Nettlau opposed all philosophical explanations of historical developments following preconceived theories, historical, political, religious or whatever.

I find now as always [so he wrote in 1929] that the historian can do little other than to interpret the sources in the most thorough and scrupulous manner, to elucidate them in every way possible, and to try to bridge the gaps by careful hypotheses ... the one-sided hunt for motives, economical or ideal, can only falsify the result beforehand. What then seem to be results are always only what such a researcher, from his personal standpoint, puts into a matter alien to him and the true nature of which nobody can reconstruct except when the sources are very good.[10]

He saw the need to study and learn from history — and the unwillingness to do so, with consequences he regretted deeply, to the point of a resigned pessimism that anarchism, the idea dearest of all to him, had alienated itself from the mass of the people instead of approaching them, and through the fault of the well-intentioned militants themselves (though he blamed no less the natural laziness of the majority of the people):

There was an absence of tradition, or rather, what pertained to the past was considered obsolete and unworthy of attention. The dominant trend, in theory, was to go all the way to anarchism and communism; in practice, it stood for non-organization and for a free life. With it came a great fervour for propaganda, and (...) many, captivated by this atmosphere of a completely free life, flocked to the groups, which grew and became numerous. Few among them understood that these impatient spirits who were so easily drawn into the groups were, after all, few in number, and that even if a large circle of people thirsting for a free, unfettered life had been formed by the anarchists, it would have been at the cost of a great isolation from the people themselves, who watched the spectacle but took good care not to participate. Worse still, the people let themselves be beguiled by the authoritarian socialists, who demanded no intellectual or revolutionary effort from them — only their votes, that is, a surrender into the hands of new masters. Thus the hopes nourished during the International, and still entertained by the libertarians in the movements of that period, (...) came to naught (...) A fine flowering did exist in isolated groups but there was no real contact with the interests of the people.

There was certainly no lack of effort exerted to come closer to the people but anarchism probably assumed larger proportions and vitality without contact with practical questions; it had full liberty for the exercise of pure criticism and of individual expression, and, from that vantage point, it was a unique period. There was a profusion of blossoming but little concern for the fruit that should issue from the flower; a decade of idealistic and aesthetic but non-utilitarian presentation of our ideas. It left its imprint upon the spirit of the world, and its last rays still cast their light upon us. To me it made manifest the fact that anarchism is human enlightenment, the great light by which humanity seeks to find its way out of the darkness of authoritarianism; it is not merely the economic solution for the misery of the exploited people. (Chap. 11, pp. 158-159)

Bakunin had just before his death expressed the wish to write an ethics for the revolutionary movement, and Kropotkin did work on his Ethics until the very end (without finishing it); Nettlau found himself driven to the same conclusions, and shared these ironically with another old comrade, the Dutch-French revolutionary socialist and syndicalist Christiaan Cornelissen:

And you have become the author of an Ethics. Hats off? — Naughty as I am, I am saying: it is there that you should have begun 50 years ago, and so should all of us! — To argue economically without ethics has served us nothing. Economy is the art of profit, whether we are capitalist or socialist. It’s the art of cutting your neighbour’s throat — you sell 10% cheaper than he does, and he will be ruined. You promise 10% more of socialist promises, and he will be yours and will give up his old socialist prophet. That’s what the history of these 50 years of economics comes to. Profit and laziness are the great aims — and the famous modern sociocrats promise laziness, spoliation, bossocracy: if one follows our way of labour and effort, they do the opposite and the masses are for them. If one asks an ordinary individual whether he wants to study, to make some effort, or whether he wants to be a dog that does not think, is told what to do and doesn’t need to worry about anything, he will prefer to be a dog — and he will abdicate humanity like the (...) voters (...), — That’s where the preponderance of the economical without ethics has led to in socialism. Therefore if you have realised this, I am happy.[11]

1. Liberty and anarchism: its earliest manifestations and libertarian ideas up to 1789.

The history of anarchist ideas is inseparable from the history of all progressive developments and aspirations towards liberty. It therefore starts from the earliest favourable historic moment when men first evolved the concept of a free life as preached by anarchists — a goal to be attained only by a complete break from authoritarian bonds and by the simultaneous growth and wide expansion of the social feelings of solidarity, reciprocity, generosity and other expressions of human co-operation.

This concept of a life of freedom has been manifested in various ways in the personal and collective life of individuals and groups, beginning with the family. Without it a human community would no longer be possible. At the same time, ever since the humanisation of the animals who constitute the human species, authority — tradition, custom, law, arbitrary rule, and so on — placed its iron grip upon a great many human interrelationships (this probably goes back to a still more remote stage of animalism). Hence humanity’s march towards progress, which surely goes on through the ages, has been and still is a continuous struggle to shake off authoritarian chains and restraints.

This struggle takes on such diverse forms, and the conflict has been so cruel and arduous, that few people have yet attained a true understanding of the anarchist idea. Even those who fought for limited freedoms have had only a rare and inadequate grasp of its essence. In fact, they often tried to reconcile their newly-won liberties with the maintenance of old restraints, either by themselves hovering on the brink of authoritarianism or by believing that authority would be useful in holding and defending their new gains. In modern times such men have supported constitutional or democratic liberty; that is, liberty under governmental control. Moreover, on the social plane, this ambiguity generated social statism — a socialism imposed by authoritarian methods and hence lacking in the very qualities, which, according to anarchist thinking, give it its true vitality — solidarity, reciprocity, generosity, which can flourish only in a free world.

In ancient times the reign of authoritarianism was general, and the uncertain, confused efforts to fight it (aiming for liberty through the use of authority) were rare though continuous. Therefore the anarchist concept, even in its partial and incomplete aspect, made an appearance very seldom, not only because it needed favourable conditions for its growth, but also because it was cruelly persecuted and crushed by violent means, or wasted, rendered defenceless and dissipated by routine. Nevertheless if, even in the midst of tribal turmoil, an individual could achieve a private life that was relatively respected, it was not due to economic causes alone. It was rather the first step on the road from tutelage to emancipation, and the men of ancient times took this path, inspired by feelings similar to those we later find in the anti-statism of modern men. Disobedience, distrust of tyranny and rebellion led many courageous men to forge for themselves an independence which they could defend and for which they were willing to die. Other men succeeded in circumventing authority through their intelligence or through some special gifts or skills. And if, at a certain stage, men passed from non-property (general accessibility of goods) and from collective property (ownership by the tribe or by the inhabitants of a region) to private property, they must have been impelled not merely by the greed for possessions, but also by the need and the will to secure a certain independence for themselves.

Even if there were thinkers of a pure anarchist type in Antiquity, they are unknown to us. The characteristic fact remains, however, that all mythologies have preserved records of revolts, even of never-ending struggles led by rebels against the most powerful deities. There were the Titans who assailed Olympus, Prometheus who defied Zeus, the dark forces that, in Nordic mythology, brought about the ‘Twilight of the Gods’. And there was the Devil — that rebel Lucifer whom Bakunin held in such respect — who, in Christian mythology, never yields and keeps on fighting in each individual soul against the good God. If the priesthood, which manipulated these tendentious stories in its own interest, did not suppress such accounts, despite their being so dangerous to the idea of the omnipotence of their gods, it was because the episodes recounted in them were so deeply rooted in the soul of the people that they did not dare to do so. All they could do was distort the facts and vilify the rebel protagonists. Later they fabricated fantastic interpretations aimed at intimidating the believers. This is particularly true of the Christian mythology, with its story of Original Sin, the Fall of man, his redemption and the Last Judgement, which amounts to the consecration and justification of man’s enslavement, confirms the prerogative of the priest as mediator, and postpones judgement day to the very last moment imaginable, the end of the world. We may conclude that, if there had not been audacious rebels and intelligent heretics, the priesthood would not have taken all this trouble.

In those ancient times, the struggle for existence and mutual aid were no doubt inextricably bound together. What is mutual aid but a collective struggle for existence, since it protects the entire community against dangers that might overwhelm an isolated individual? What is the struggle for existence but the act of an individual who brings together a great number of forces or skills and thus prevails over another who gathers a smaller number? Progress was made by autonomous and free associations created in a social environment which was relatively secure and of an advanced character. The great Oriental despotisms did not permit of true intellectual progress. The Greek world, on the other hand, where free local autonomies existed, saw the first flowering of free thought that we have known. Greek philosophy was able, in the course of centuries, to reach out to Hindu and Chinese thought. It particularly created independent work of its own, which the Romans, with all their great desire to drink deep of the sources of Greek civilisation, were incapable of understanding and continuing. It remained equally closed to the unenlightened world of the medieval millennium.

What goes under the name of philosophy was, in those early days, a complex of considerations, independent as far as possible of religious tradition, though formulated by individuals immersed in that tradition. These were reflections drawn from more direct observation, some of them based upon experience. They included, for instance, speculations concerning the origin and essence of worlds and things (cosmogony), the conduct of the individual and his highest aspirations (morals), the collective civic and social conduct (social politics). It also dealt with the ideals of a more perfect world in the future, and the means to attain it (a philosophic ideal which is actually a utopia, bringing together these thinkers’ analyses of the past and present, and the trend of further evolution as they observed it and judged auspicious for the future).

Religions had originated earlier, in much the same manner, though under generally more primitive conditions, and the theocracy of the priesthood and the despotism of kings and chiefs were parallel with that stage. The population of the Greek territories, on the mainland and the islands, kept apart from the despotism of neighbouring countries and created a type of civic life, of autonomous groups and federations, which nourished small centres of culture. It also produced philosophers who, rising above their traditional role, sought to be of use to their small native republics and dreamed of progress and general well-being (without, be it said, daring or attempting to fight the slavery in their midst, which goes to show how difficult it is to rise above one’s own environment).

This period witnessed the development of an apparently more modern type of government and of politics, which replaced the Asiatic type of despotism and completely arbitrary rule without, however, supplanting it entirely. It was a type of progress similar to that of the French Revolution and to that of the 19th century, in relation to the absolutism of the 18th century. Just as that later period gave rise to ideas of a pure socialism and to anarchist concepts, so, alongside the great number of Greek philosophers and statesmen of a moderate and conservative tendency, there were bold thinkers, some of whom in those early days arrived at the ideas of State socialism, and some at anarchist principles. These were no doubt a small minority, but they left their mark and cannot be ignored by history, although the rivalries of the schools, the persecutions and the indifference of ages of ignorance caused their writings to disappear. In fact, where their work did survive it was preserved in extracts in the texts of better-known writers.

These small republics, exposed to constant danger, and themselves ambitious and aggressive, had a lively concern for civic life and patriotism. They were rent by factional strife, demagogy and the thirst for power, which laid the groundwork for the development of a rigid communism. This provoked in many men an aversion to democracy, which expressed itself in the desire for a government by the wisest men, the sages, the elders, such as Plato had dreamed of. And simultaneously came an aversion from the State, the desire to do away with it, as professed by Aristippus, as expressed in the libertarian ideas of Antiphones, and more strongly in the great work of Zeno of Citium (336-264 BC), founder of the Stoic school, which excluded all external compulsion and proclaimed the individual’s moral impulse as the sole and sufficient guide for individual and communal action. It was the first clear call of human liberty, conscious of its own maturity and released from authoritarian bonds.

However, just as religions transfer men’s aspirations for justice and equality to a fictitious ‘heaven’, so the philosophers and sundry jurists of those days transmuted the ideal of a truly just and equitable law, based upon promises and formulated by Zeno and the Stoics, into the so-called ‘natural law’, which, like its counterpart ideal concept of religion — ‘natural religion’ — cast a feeble glow through many centuries of cruelty and ignorance until its light rekindled man’s spirit and inspired it with the desire to bring these abstract ideals into realisation. This was the first great service rendered by the libertarian idea to man; its ideal, diametrically opposed to the ideal of the supreme and definitive reign of authority, has been gradually absorbed during the past two thousand years.

We can well understand why authority — the State, property, the Church — opposed the spread of these ideas. It is a well-known fact that the Roman Republic, the Roman Empire and the Rome of the Popes, up to the 15th century, imposed an absolute intellectual fascism upon the Western world, complemented by the Oriental despotism reborn among the Byzantines and the Turks, and Russian Tsarism (now virtually continuing under Russian Bolshevism). Until the 15th century and even later (Servetus, Bruno, Vanini) free thought was forbidden under pain of death; all communication among some learned men and their disciples was carried on under cover, perhaps in the intimate circles of some secret societies. Free thought never saw the light of day except when, merged with the fanaticism and mysticism of a religious sect, it felt itself consecrated and fearlessly and joyfully accepted death. The original records of such events were carefully destroyed and we have nothing left to us but the voices of those who denounced, those who maligned, and, often, those who had executed the victims. Thus Carpocrates of the Gnostic school in Egypt, in the 2nd century AD, preached a life of free communism and also quoted from the New Testament (Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians, 6:18), ‘But if ye be led by the Spirit, ye are not under the law’, a statement which seemed to lend itself to the idea of a life outside the State, without law or master.

The last six centuries of the Middle Ages were the era of the struggles of local communities (cities and small regions), anxious to federate, as well as of large territories which united to form the great modern States, as political and economic units. If the smaller units were centres of civilisation and, as such, could have prospered through their own productive labour, through federations useful to their interests and the superiority of their wealth over poor agricultural communities and less fortunate cities, their complete success would merely have enhanced their advantages at the expense of the continual poverty of less well-off units. Was it more important for some free cities, such as Florence, Venice, Genoa, Augsburg, Nuremberg, Bremen, Ghent, Bruges and others to grow rich, or for the entire regions surrounding them to gain well-being, education and other benefits? History, up to 1919 at least, decided in favour of the great economic units, and, in consequence, the small communities were reduced and decayed.

Authoritarianism and the desire for expansion and domination were present in both the small and the large units, and liberty was a word equally exploited by both. The smaller units broke the power of the cities and their alliances (leagues); the larger attacked the power of the kings and their States.

Nonetheless, in this situation, too, it was the cities that often supported independent thinking and scientific research, and granted temporary asylum to dissidents and heretics driven from other places by persecution. It was particularly the Roman municipalities situated along the highways of commercial traffic, as well as the many other prosperous cities, which became the centres of this intellectual independence. From Valencia and Barcelona to North Italy and Tuscany, to Alsace, Switzerland, South Germany and Bohemia, through Paris to the mouth of the Rhine, up to Flanders and the Netherlands and the German coast (the Hanseatic cities), was a territory studded with centres of localised liberty. And then came the wars of the Emperors in Italy, the crusade against the Albigenses and the centralisation of France by the kings (especially Louis XI), the Castilian supremacy in Spain, the struggle of the States against the cities in the South of Germany, and in North Germany the struggles of the Dukes of Burgundy, and so on, which culminated in the supremacy of the great States.

Among the Christian sects the one to be particularly remembered is the ‘Brothers and Sisters of the Free Spirit’, who practised unlimited communism among themselves. Their tradition, probably originating in France and destroyed by persecutions, survived chiefly in Holland and in Flanders; the ‘Klompdraggers’ of the 14th century and the followers of Eligius Praystinck, the so-called ‘libertines’ of Antwerp in the 16th century (the ‘loists’ seem to have derived their origin from that sect). In Bohemia, after the Hussites, Peter Chelčický preached a type of moral and social conduct which anticipates the teachings of Tolstoy. And here we find again sects of so-called ‘Direct Libertines’, particularly the ‘Adamites’. Some of their writings are known to have survived, especially those of Chelčický (whose moderate followers were later known as the ‘Moravian Brothers’). But so far as the more advanced sects are concerned, all we have is the horrendous libels of their zealous persecutors and it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine to what extent their defiance of the States and laws was a conscious anti-authoritarian act, since they claimed they were authorised to act by the word of God, who thus remained their supreme lord.

The Middle Ages could not produce a rational and thoroughgoing libertarianism. It was only the rediscovery of Greek and Roman paganism, the humanism of the Renaissance, which provided many scholars with the means for comparison and criticism. They viewed various mythologies as being as ‘perfect’ as the Christian mythology, and some of them, suspended between total belief and total disbelief, discarded all belief. The title of a brief treatise of unknown origin, De tribus impostoribus (The Three Imposters: Moses, Christ and Muhammad) clearly points up this tendency. Then a French monk, François Rabelais, wrote the liberating words, ‘Do what thou wilt’, while a young lawyer, Étienne de La Boëtie left us his famous Discours de la servitude volontaire (Discourse of Voluntary Servitude).

This bit of historical research will teach us to be modest in our expectations. It would be quite easy to come across glowing paeans to freedom, to the heroism of tyrannicides and other rebels, to popular revolts, and so on, but very difficult to find an understanding of the evil inherent in authoritarianism and a complete faith in liberty. The words of the thinkers we have quoted here may be considered merely the earliest intellectual and moral attempts of humanity to advance without tutelary gods and constricting chains. (It seems to be little, but it is a ‘little’ that cannot be set aside and forgotten.) Confronting the ‘three imposters’, there finally arose science, the free mind, a deepened search for truth, experimental observation and true experience. L’Abbaye de Thélème (The Abbey of Thelema — neither the first nor last happy isle of the imagination), as well as the authoritarian, statist utopias (notably those of Thomas More and Tommaso Campanella), which mirrored the great new centralised States, revealed aspirations toward an idyllic, innocent, peaceful life, full of mutual respect and affirmation of the need of liberty for the human race — all this in the centuries (the 16th, 17th and 18th) crowded with wars of conquest, religion, commerce, diplomacy and ruthless overseas colonisation carried on through the subjugation of new continents.

Even ‘voluntary servitude’ at times took steps to put an end to itself, as in the struggle of the Netherlands, and the fight against the royal power of the Stuarts in the 16th and 17th centuries, as well as the revolutionary war of the North American colonies against England in the 18th century, up to the emancipation of Latin America in the early part of the 19th century. Thus rebellion made its entry into political and social life, along with the spirit of voluntary association, as manifested in the projects and attempts at industrial co-operation in Europe, already in existence in the 17th century, and in the practical development of more or less autonomous and self-governing organisations in North America, both before and after its separation from England. The later centuries of the Middle Ages had already witnessed central Switzerland successfully defying the German Empire, the great peasant rebellions and the violent declarations of local independence in various regions of the Iberian peninsula. Paris stood firm against the power of the kings on many occasions up to the 17th century, and again in 1789.

We know that this libertarian ferment was still too limited, and that the rebels of yesterday became enthralled by a new authoritarianism on the morrow. It was still possible to have people murdered in the name of this or that religion, especially if the masses were inflamed with religious zeal intensified through the Reformation or fell under the whip and the spur of the Jesuits. Besides, Europe at that time lived under bureaucracy, the police power, the permanent armies, the aristocracy and the courts of the princes, as well as under the subtle domination of the powers of commerce and finance. Few were the men who could envisage libertarian solutions and discuss them in their Utopias. Such was Gabriel Foigny, in Les Aventures de Jacques Sadeur dans la découverte et le voyage de la Terre Australe (Adventures of Jacques Sadeur in the Discovery of and the Voyage to the Austral Land) (1676). Others employed the fiction of savages who were ignorant of the refined life of police States, as for instance Nicolas Gueudeville in his Entretiens entre un sauvage et le Baron Hontan (Conversations between a Savage and the Baron of Hontan) (1704), or Diderot in his famous Supplément au Voyage de Bougainville (Supplement to the Voyage of Bougainville).

There was an attempt at direct action, to recover freedom after the fall of the British monarchy in 1649, led by Gerrard Winstanley (the Digger). There were projects of voluntary socialism by means of associations, put forward by the Dutchman P. C. Plockboy (1658), John Bellers (1695) and the Scot Robert Wallace (1761), also in France by Restif de la Bretonne.

There were keen thinkers who dissected statism, among them Edmund Burke, in his Vindication of Natural Society, while Diderot was familiar with thinking which led to truly anarchist conclusions. There were some isolated writers who attacked law and authority, such as William Harris in Rhode Island, United States, in the 17th century, also Mathias Knutsen, in Holstein, in the same century, and Dom Deschamps, a Benedictine monk in France, in the 18th century, who left a manuscript which has been known since its discovery in 1865. Also A. F. Doni, Montesquieu (the Troglodytes), G. F. Rebmann (1794), Dulaurens (1766, in several parts of his Compère Mathieu), depict small countries and happy retreats without property and without laws. A few decades before the French Revolution Sylvain Maréchal proposed a type of anarchism which was set forth with great clarity, in the form of a fabled Arcadian era of happiness, in his L’Age d’Or recueil de contes pastoraux par le Berger Sylvain (Golden Age, Collection of Pastoral Tales by the Shepherd Sylvain), (1782) and in his Livre échappé au déluge ou Psaumes nouvellement découverts (Book which escaped the Deluge, or Psalms Recently Discovered) (1784). Maréchal also produced one of the strongest pieces of propaganda on behalf of atheism and in his Apologues Modernes à l’usage d’un Dauphin (Modern Apologues, to be used by a Dauphin) (1788) pictured the life of kings exiled to a desert island where they ended up exterminating each other, and sketched the outlines of a general strike whereby the producers, who constitute three-quarters of the population, create a free society. During the French Revolution, Maréchal was impressed and fascinated by revolutionary terrorism, yet could not help writing, in the Manifeste des Egaux (Manifesto of the Equals) of the followers of Babeuf, the following words: ‘Begone, odious differences between rulers and the ruled.’ These words were later completely repudiated by the accused authoritarian socialists and by Buonarroti himself, during their trials.

By the end of the 18th century anarchist ideas are also clearly expressed in the works of Lessing who was known as ‘the German Diderot’. The philosophers Fichte and Krause, as well as Wilhelm von Humboldt (1792 — brother of Alexander), favoured libertarianism in some of their works. Likewise, in England, the young British poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his friends in the period of his ‘Pantisocracy’. An early application of these ideas is found in educational reform as interpreted in the 17th century by Jan Amos Comenius, stimulated by J. J. Rousseau, under the influence of all the humanitarian and egalitarian ideas of the 18th century, and particularly diffused in Switzerland (Pestalozzi) and in Germany, where even Goethe contributed enthusiastically. Society without authority was recognised as the ultimate goal in the most intimate circles of the German ‘Illuminati’ (Weishaupt). The Bavarian, Franz Baader, was deeply impressed by Godwin’s Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, which appeared in a German translation (the first part only) in Würzburg in 1803. Even the German scientist and revolutionary, Georg Forster, read Godwin’s book in Paris some months before his death in January 1794, without having been able to give public expression of his opinion of this work, which had so fascinated him (letter of 23 July 1793).

These are only short extracts from the main arguments which I have advanced in Der Vorfrühling der Anarchie (1925; pp. 5-66). I would need a few more months of research in the British Museum to complete the work by consulting Spanish, Italian, Dutch and Scandinavian texts. I have unearthed much material in French, English and German publications. It seems to me that what still remains to be studied would necessarily be abundant and interesting, but not of prime importance.

The sources here quoted are not numerous but they are quite adequate. Everybody knows Rabelais; through Montaigne one can always get at La Boëtie. Gabriel Foigny’s utopia was well known; it was reprinted and translated many times. Burke’s youthful tour de force gained great popularity, and Sylvain Maréchal was amply discussed. Diderot and Lessing were classics.

In consequence, all their concepts which were profoundly anti-authoritarian, their critique and rejection of the idea of government, their attempts to reduce and even deny the role of authority in education, in the relationship of the sexes, in religious life, in public life — all this did not pass unnoticed in the advanced circles of the 18th century. And it can be said that, as a supreme ideal, it was opposed only by the reactionaries, while moderate thinkers considered it forever unattainable. Through the ideas of natural law and natural religion, and the materialistic concepts of Holbach (Système de la Nature, 1770) and La Mettrie which were broadcast and diffused through the channels of steadily growing and highly organised secret societies, all the humanitarian cosmopolites of the century were orientated intellectually towards a minimum of government, if not its total absence. Herder, Condorcet, Mary Wollstonecraft, and even —a little later — the young Shelley, all felt that the trend of the future was toward the humanisation of humanity and that this would inevitably render government superfluous.

Such was the situation on the eve of the French Revolution, when everybody was still unaware of all the forces for good and evil that a decisive blow at the old regime would set in motion. They lived surrounded by insolent exploiters of authority and all their age-old victims, but those forward-looking people desired the greatest liberty. They were people of discernment and they had high hopes, The long night of authority was about to come to an end.

2. William Godwin; the Illuminati; Robert Owen and William Thompson; Fourier and some of his followers.

A great revolution occurs when the river of evolution suddenly changes its course and bursts its banks in violent turbulence beyond the control of its navigators, who are cast adrift or drowned. But their work is carried on, under changed conditions, by their successors. Even those who manage to survive one phase of the revolution also perish or undergo a transformation, so that, when the storm has blown over, hardly anyone can exert a vital and wholesome influence on the new stage of evolution. In other words, revolution, like war, destroys, consumes or changes those who take part in it. It transforms them into authoritarians, whatever their previous bent may have been, and leaves them ill-prepared, after their revolutionary experience, to defend the cause of freedom.

Only those who have remained faithful to the revolution, those who have learned a new lesson from the faults committed by authority, and those who possess a revolutionary spirit of exceptional force, emerge unscathed from a revolution — Elisée Reclus, Louise Michel and Bakunin had these three qualities — whereas almost all the rest are weighed down by the fatal burden of authoritarianism, which is still inseparable from great popular upheavals.

Thus, after an initial period of a few months (1789 in France, 1917 in Russia) authoritarianism took the upper hand, and those 45 or more years before 1789 — the brilliant era of the Encyclopedists with their liberal and at times libertarian critique of the ideas and institutions of the past — were as nothing. And that century of political and social struggles in Russia up to 1917, was rendered vain and fruitless by the ensuing bitter clashes among conflicting interests for the conquest of power, that is, for the dictatorship.

This phenomenon can be neither denied or minimised. It is rooted in the enormous influence which authority exerts upon the human mind, and in the vast interests which are at stake when privilege and monopoly are threatened. Then it becomes a life-and-death struggle, and such a struggle, in an authoritarian world, is fought with the deadliest weapons.

In the early months of 1789, when the States General held their meetings in France, and again after 14 July, when the Bastille was taken, there were hours and days of high exultation, of generous, warm solidarity, and the entire world shared that joy. But in those very moments the counter-revolution was already plotting, and throughout the following period it conducted its relentless defence, openly or under cover. That is why the vanguard of the revolution, with all the general good will on its behalf, all the high and generous expressions of popular support, made very few gains after 14 July. The opposition accomplished everything, in those revolutionary days, through powerful thrusts expertly led by trained militants, and by seizing control of the entire government apparatus reinforced at that time in the interior of the country by the central dictatorship of the Committees and the local dictatorship of the Sections. Having secured a firm hold on the interior regimes, it established its centre of gravity in the armies. From one of these armies issued the dictatorship of its leader, Napoléon Bonaparte; then followed his coup d’état of the 18th Brumaire, his Consulate and his Empire — his dictatorship over the European continent.

The aristocracy was promptly converted into the ‘White Army’ of the émigrés. The peasants, seeking protection against the return of feudalism, allied themselves with the most authoritarian and militarily powerful government. The bureaucracy grew rich from the hunger of the masses or from provisions destined for the wars. Workers and artisans in the cities found themselves cheated on all sides, reduced to silence by harsh governments, delivered into the hands of a flourishing bourgeoisie and snatched by armies that were always greedy for human fodder.

Unsurprisingly, in this situation, the ultra-authoritarian communism of Babeuf and Buonarroti came to the fore in 1796, while during the most advanced period of revolution, from 1792 to 1794, socialist aspirations merged with the demands of more radical popular groups, those of Jacques Roux, Leclerc, Jean Varlet, Rose Lacombe and others. The Enragés, the most determined Hébertists, Chaumette, Momoro and also Anacharsis Cloots were men filled with a spirit of self-sacrifice, convinced advocates of direct popular action, and exasperated with the new revolutionary bureaucracy. It can be said of them only that they were good revolutionaries, although we do not know whether they had libertarian ideas, and Sylvain Maréchal had nothing to say on the subject. Buonarroti, however, inspired by the genuine socialism of Morelly (Morelly, Code de la Nature, 1755), saw in Robespierre the man who could bring about social justice. Thus all the socialists either allied themselves with the Reign of Terror or demanded that it be carried to an even greater degree. And the government either accepted and even solicited their adherence or sent to the guillotine and destroyed those among them who were too undisciplined. Jacques Roux and later Darthé killed themselves before the Tribunal; Varlet, Babeuf and others were executed.

The death sentence did not spare even those who held less advanced views than the men in power. Danton and Camille Desmoulins, as well as the Girondists, were condemned to death, while Condorcet escaped the guillotine only by committing suicide in prison. To dare to doubt the absolute centralisation, to be suspected of sympathy for federalism, meant death.

It has become traditional to consider it as an act of heroism on the part of revolutionaries to decree innumerable death sentences by the guillotine for their erstwhile comrades. From what we know of events in Russia over 15 years, we no longer believe in the heroism of certain men who could maintain their supremacy only through the ferocious suppression of those who did not recognise their omnipotence. It is a mode of action inherent in all authoritarian systems; it was practised by the Napoléons and Mussolinis with the same ferocity as by the Robespierres and the Lenins.

Thus after 1789 the libertarian idea declined in France. A spark of ultra-moderate and socially conservative liberalism lingered on in a few men who, thanks to their considerable personal means, were able to remain aloof from State careers — men whom Napoléon contemptuously dubbed ‘ideologues’. They reappeared on the political scene in 1814, and, after 1830, ended up by merging into the prosperous bourgeoisie of the reign of Louis Philippe.

In other European countries, beginning in 1792, the idea of expansion through armed revolution found some enthusiastic supporters, particularly in Italy, Belgium, Holland, Germany (in Mainz), Geneva and so on. But these wars of liberation, which created short-lived republics, soon came to be considered as simple wars of conquest, and national resentment in Spain, Austria, Germany and other countries grew to such an extent that Napoléon turned, in the eyes of nearly everyone, from a hero into a tyrant, and his fall in 1814 and 1815 was greeted with general relief.

We do not propose to discuss here the beneficial results of the French Revolution. We can only point out that, as the Russian system of government of the past 15 years has brought nothing of value to the cause of anarchism in our days, so it can be said that the French Revolution accomplished very little for the libertarian cause of that period. This libertarian cause was in the ascendant during the second half of the 18th century; authority was discredited and in a state of moral decay. Nevertheless the conflicts of power and of vested interests in the Assembly of 1789 put the old and new authorities in direct confrontation with each other so that, from then on, it became necessary to be either a reactionary or an ardent advocate of Republican, Consular, Imperial authority. To continue supporting constitutional or republican authority has always meant, from 1789 to this day, to support authoritarianism, even if it assumed the form of a syndicalist dictatorship.

‘Anarchism’ had to make a fresh start around 1840, with Proudhon, and then again, 40 years later, around 1880. In 1789 liberty lost its impetus in France and in all other nations of Europe; it was a great break in a fine flowering only just begun. What followed was a jumble of liberty and authority — the system of constitutional or republican majority rule, a lifeless spectacle filled with liberals in fair weather and conservatives in foul, incapable of standing up against the assaults of the massive reaction of our time; a spectacle filled with individuals who seem to have been steadily deteriorating in quality from 1789 to our day, individuals who inspire no sympathy and create no illusions. The shaky statism of the old regime was replaced by a severe and meticulous statism, the old militarism by the militarism of popular armies and compulsory conscription. Literature, philosophy and the arts exalted the State and the fatherland, which, under the old system, had been subjected, for a span of over fifty years, to a rigorous critique. Religious disbelief in those years was no longer in fashion, since authority is always religious and, when the need arises, makes a cult of religion, using the schools, the press and the barracks for its own purposes.

That entire period, from 1789 to 1815, was poor in intellectual growth; there was, instead, a large output of works contributing to the life of the State — roadworks, buildings, all equipment essential to administrative purposes — the army, large-scale communications, standardisation of the metric system, and so on.

It was only in England that the first work of a libertarian character appeared in February 1793, under the title of An Enquiry concerning Political Justice and its Influence on General Virtue and Happiness (the second edition had Morals and Happiness in place of General Virtue and Happiness).

The author of this work, William Godwin, stated in his preface, dated 7 January 1793, how he had become convinced, about 1791, through the political writings of Jonathan Swift and of the Roman historians, that the monarchy was a system of government which was fundamentally corrupt. At about that time he had read Holbach’s Système de la Nature and the writings of Rousseau and Helvétius. He had conceived some of the ideas for his book much earlier but had only arrived at the desirability of a government simple to the highest degree (as he described his anarchist ideal) thanks to ideas suggested by the French Revolution. To that event he owed his determination to proceed with this work. He wrote it between 1789 and 1792, at a time when British public opinion had not yet been aroused against the French Revolution (this happened after his book was published). It is well known that only the high cost of the two volumes prevented them from being seized and condemned, since they were obviously not books destined for popular propaganda.

On considering the moral state of individuals and the role of the government, Godwin comes to the conclusion that the influence of governments on men is, and can only be, deleterious, disastrous. ‘May it not happen’, he states in his guarded but pregnant prose (2nd edition, vol. I, p. 5), ‘that the grand moral evils that exist in the world, the calamities by which we are so grievously oppressed, are to be traced to its defects in their source, and that their removal is only to be expected from its correction? May it not be found, that the attempt to alter the morals of mankind singly and in detail is an enormous and futile undertaking; and that it will then only be effectually and decisively performed, when, by regenerating their political institutions, we shall change their motives and produce a revolution in the influences that act upon them?’

Godwin also proposes to demonstrate the extent to which government renders men unhappy, and how this affects their moral development. He seeks to set forth the conditions of ‘political justice’, that is, a state of social justice, that would be best fitted to render men sociable (moral) and happy. The results he arrives at are certain conditions regarding property, public life and so on, which grant to the individual greater liberty, accessibility to the same means of existence, as well as that degree of social life and individual life which best suits him. All this to be attained voluntarily, at once, or gradually, through education, discussion and persuasion, but definitely not through the use of authoritarian tactics from the top down. This is the road he would chart for mankind’s future revolutions. He sent his book to the National Convention of France; it was passed on to the refugee German scholar Georg Forster, who read it with enthusiasm but died a few months later without having had a chance to publicly express his opinion of it.

On reading Political Justice even at this time, one becomes aware of temperate anti-governmentalism, well argued logically, while statism is demolished to the ground. For over 50 years this book served as a textbook for serious study by radicals and by many British socialists, and British socialism owes its great independence from statism to Godwin’s work. It was the influence of Mazzini’s ideas, the bourgeois outlook of Professor Huxley, the electoral ambitions and the professionalism of trade union leaders, which led, toward the middle of the 19th century, to a weakening of Godwin’s influence. However, his teachings came to life once more in poetry; they fascinated the young Shelley and speak to us again in his verse.

As for Godwin himself, his career was shattered on publication of this book. Although the work was not confiscated or prosecuted, nationalist and anti-socialist propaganda, going under the name of Anti-Jacobin’, at that time and for many years thereafter concentrated its attacks upon him and his ideas, which were strongly anticonformist on questions of religion, marriage and so on. Although he was convinced of the justice of his ideas, Godwin, lacking strength of character and sufficient courage, adopted a more moderate tone in the second edition, and took good care not to give his further writings the strongly independent cast which characterised his Political Justice in 1793. In a word, Godwin was intimidated; he never regained a position of challenge, though he never openly repudiated his ideas. This turn of events probably contributed to the fact that his ideas, though emphatically libertarian, did not have direct popular appeal. Another reason for their scant popularity, however, may have been that the English populace, suffering under the harsh persecution of the courts, was drawn to the terrorist tactics and authoritarian socialism which came from France, from the Convention and from Babeuf. The misery of labour in the new factories, the open harassment of workers’ associations, the insolence of the ruling aristocracy, turned the people on the road to authoritarianism and away from the libertarian course which could at least have prevented the replacement of the authority of one group by that of another.

Godwin shows his familiarity with the various critiques of property from Plato to Mably, and makes special references to a book by Robert Wallace (Various Prospects of Mankind, Nature and Providence — 1761) and to An Essay on the Right of Property in Land published some 12 years before his own work ‘by an ingenious inhabitant of North Britain’ [William Ogilvie]. There also existed at that time a movement of a clearly socialist character, led by Thomas Spence, who began to expound his theories in 1775. But there had been no authoritarian socialist theory presented to the public at large, or Godwin would have examined it. He merely confined himself to saying that ‘the systems presented by Plato and others are full of imperfections’, and concluded by pointing out the value of the arguments against property, which, he said, left their mark in spite of the imperfections of the systems. He also said that ‘the real great authoritarian systems were those of Crete (Minos), Sparta (Lycurgus), Peru (the Incas) and Paraguay (the Jesuit Missions)’ (Vol. II, p. 452, note).

About 12 years before publication of Godwin’s book, Professor Adam Weishaupt wrote his Anrede an die neu aufzunehmenden Ill[uminati] dirigentes, an address to be read at the reception of new administrators before the secret society of the so-called ‘Illuminati’, which was founded in Bavaria and had spread throughout the German-speaking countries. As a result of persecutions carried on from 1784, this text, along with many other documents, had been confiscated. It was made public by order of the Bavarian government in 1787.

In this discourse the author first returns to the life without constraints led by primitive man. He then goes on to show how, with the growth of the population, society was organised originally for useful and defensive purposes; how society later degenerated into kingdoms and States, with the resulting subjugation of humanity (‘... nationalism took the place of love for one’s neighbours’). His tightly woven argument concludes with an evolutionary phase which will bring people into mutual relationships that will be more meaningful than those of States: ‘Nature has wrested people from savagery and brought them together in States. From the States we are now entering upon a new stage, more consciously chosen. New associations are being formed, in accordance with our own wishes, whereby we shall again return to our original point of departure’ (that is, to a life of freedom, but on a higher plane than our primitive condition) (Adam Weishaupt, Anrede an die neu aufzunehmenden Ill[uminati] dirigentes, p. 61). The States, which represent a transitional stage and are the source of all evil, are thus doomed to disappear and people will regroup themselves in a more reasonable manner. This, in a nutshell, is what Godwin was later to proclaim. Even the steps for bringing about the abolition of the States are fundamentally the same: wise education and persuasion, and to those Weishaupt also adds secret action, of which, however, no mention is made in this address but which was described and sustained in other documents of the ‘Illuminati’.

On this subject Weishaupt says:

These methods are the secret schools of knowledge, which at all times have been the archives (repositories) of nature and of human rights. With the use of these means humanity will lift itself from fallen conditions and the national States will disappear from the face of the earth without violence. Humanity will some day come to be a family, and the world will become a dwelling-place for more rational people. Each father of a family will be its priest and absolute master, just as Abraham and the patriarchs had been, and reason will be the only law for humanity. (Anrede ..., p. 80-81).

Apart from his antiquated style, and the references to religious tradition — characteristics of most of the secret societies and employed as protective colouration — Weishaupt’s reasoning as regards the condemnation of statism is as clear and conclusive as Godwin’s. His methods of persuasion and action resemble those of Bakunin in his Fraternité Internationale (International Brotherhood) and the Alliance (International Alliance of Social Democracy), which were to be at the very core of the great public socialist movements.