Lisa McGirr

The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti

A Global History

On May 1, 1927, in the port city of Tampico, Mexico, a thousand workers gathered at the American consulate. Blocking the street in front of the building, they listened as local union officials and radicals took turns stepping onto a tin garbage can to shout fiery speeches. Their denunciations of American imperialism, the power of Wall Street, and the injustices of capital drew cheers from the gathered crowd. But it was their remarks about the fate of two Italian anarchists in the United States, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, that aroused the “greatest enthusiasm,” in the words of an American consular official who observed the event. The speakers called Sacco and Vanzetti their “compatriots” and “their brothers.” They urged American officials to heed the voice of “labor the world over” and release the men from their death sentences.[1]

Between 1921 and 1927, as Sacco and Vanzetti’s trial and appeals progressed, scenes like the one in Tampico were replayed again and again throughout Latin America and Europe. Over those six years, the Sacco and Vanzetti case developed from a local robbery and murder trial into a global event. Building on earlier networks, solidarities, and identities and impelled forward by a short-lived but powerful sense of transnational worker solidarity, the movement in the men’s favor crystallized in a unique moment of international collective mobilization. Although the world would never again witness an international, worker-led protest of comparable scope, the movement to save Sacco and Vanzetti highlighted the everdenser transnational networks that continued to shape social movements throughout the twentieth century.[2]

The “travesty of justice” protested by Mexican, French, Argentine, Australian, and German workers, among others, originated in events that took place just outside Boston in 1920. On April 15, the payroll of the Slater and Morrill Shoe Company in South Braintree, Massachusetts, was stolen and the paymaster and a guard murdered. Acting on a hunch that the crime was the work of local anarchists, a veteran police officer, Michael Stewart, arrested two obscure radicals and charged them with robbery and murder. The arrest of the two—Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti—coming at a time of heightened political repression in the United States, attracted the attention of leftist sympathizers. When a Dedham, Massachusetts, jury declared the two men guilty of murder on July 14, 1921, anarchists and radicals in the United States and abroad moved into action. The trial, in their eyes, had been a mockery of justice: No money was found linking the two convicted men to the crime. There was no physical evidence against Vanzetti. Both men provided alibis, and scores of witnesses testified on their behalf. Prosecution witnesses made contradictory and weak statements. From the district attorney’s opening remarks calling on the “good men and true” of Norfolk County to “stand together” to the presiding judge’s closing instructions to the jury saluting “patriotism” and “supreme American loyalty,” the court had seemed to attach as much significance to the defendants’ status as immigrants and their views as radicals as to their culpability.[3] The apparent unfairness of the trial and its negative outcome galvanized Sacco and Vanzetti’s supporters to call for a retrial. In Boston, New York, and Chicago, and, more suprisingly, in Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Marseilles, Casablanca, and Caracas, workers organized vigils and rallies to express their solidarity with Sacco and Vanzetti. In Venezuela, according to the American minister there, “practically all the lower classes regarded them as martyrs.” One old servant of a well-to-do family, he recounted, had even “arranged a newspaper picture of Sacco and Vanzetti surrounded by burning candles and was praying for them before it.” The storms of protest that raged in Europe and Latin America led the conservative French newspaper Le Figaro to ask direly, “to what kind of folly is the world witness?” The editor of the New York–based Nation magazine declared shortly before their execution, “Talk about the solidarity of the human race! When has there been a more striking example of the solidarity of great masses of people than this?”[4]

No one has charted the global nature of the mobilization in support of Sacco and Vanzetti or has adequately explained their international prominence. Instead, shelves of books have focused on the legal aspects of their trial, delineated its domestic ramifications, and rehashed the question of guilt and innocence. That focus has been predominant in the literature in no small part because the question of guilt or innocence has proved so difficult to resolve. The biased trial proceedings and the use of faulty evidence make assertions of either man’s guilt difficult to sustain, but neither has their innocence been firmly established. Ballistics evidence points to Sacco’s gun as the murder weapon, and statements made by Sacco’s lawyer Fred Moore after he left the case and the anarchist Carlo Tresca shortly before his death point to Sacco’s guilt. Some argue that the ballistics evidence was the result of a “frame-up” and that bitterness and anger led Tresca and Moore to reformulate their opinions years after the trial. Even those who argue for Sacco’s guilt assert that Vanzetti was probably innocent. There is continued room for more than a “reasonable doubt.”[5]

The focus on the guilt or innocence of Sacco and Vanzetti has caused us to neglect the vast international movement in their support. Other miscarriages of justice and other efforts to repress radical movements failed to attract such outcry. So why Sacco and Vanzetti? A closer look at this moment of international mobilization not only reveals a fascinating and important story but also brings a fresh perspective on the global connections of the United States. As important, the distinctive angle of vision necessary to tell this story promises to reveal dimensions of history in the 1920s that transcend individual nation-states.

In recent years, scholars have called for U.S. historians to embed American history in a global context. Historians have revealed identities, networks, and processes that extend beyond the nation-state. Such studies, focusing on economic ideas, policy makers, social elites, and institutions, have neglected transnational social movements. By revisiting the history of the Sacco and Vanzetti case, this essay reveals an important moment of transnational movement building. Although it was preceded by earlier transnational mobilizations in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—from abolitionism to woman suffrage—the “passion” of Sacco and Vanzetti brought the popular masses for the first time to the forefront of international protest. Never before had global radical institutions and global mass communications played such a central role in collective popular mobilization. The international social movement around Sacco and Vanzetti also highlights transformations in the dynamics of global radicalism and of class. Only by moving beyond individual nations can we understand what dynamics were not “French,” “American,” or “Argentine,” but part of broader trends with repercussions in many countries. It is such trends that the history of the social movement in support of Sacco and Vanzetti reveals.[6]

This essay looks at the international history of the 1920s from a distinctive angle. The first of its three parts traces the setting of global radicalism, in particular, the ethnic dimensions of the international mobilization and the culture of the Left necessary to make the men household words in far-flung places. The essay argues that the case resonated so widely and deeply because of the new visibility and vocality of the masses after World War I.[7] Second, the essay explores how a mobilization around a single case grew into a broad popular front movement. Here I emphasize the role of intellectuals and their transnational connections. I contend that the location of the trial in the United States at a time of heightened concerns with rising American power is fundamental to understanding its resonance. Third, the essay examines memorialization of the case in the wake of the men’s execution, which determined the meanings of “Sacco and Vanzetti” in the 1920s and beyond.

The notoriety of the Sacco and Vanzetti case must be situated in the history of labor internationalism. Since the founding of the First International in 1864, radical worker politics had been internationalist in theory and practice. Anarchists, Communists, and socialists, while hostile to one another, shared a vision of worker solidarity that sought to transcend national allegiances in order to support comrades in faraway lands. Sacco and Vanzetti’s global presence points to a moment when radical labor movements in Europe, Latin America, and North America had built on the massive European migrations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to forge transnational communities, networks, and identities.[8]

The position of the United States as the quintessential capitalist nation, moreover, encouraged radicals around the globe to take an interest in the American labor movement. As Friedrich Engels wrote in 1886 regarding the rise and fall of the Knights of Labor, “Nowhere in the whole world do [capitalists] come out so shamelessly and tyrannically as over there.” The radical international labor movement had mobilized in solidarity to aid victims of “class warfare” in the United States—from the Haymarket affair in 1886 to the effort to win clemency for Tom Mooney and Warren Billings, two radicals tried and sentenced for murder after a bomb was thrown during a preparedness day parade in San Francisco in 1916.[9]

Proletarian internationalism, like nationalism, was defined by an imagined community, with the universal working class as its starting point. The global labor movement spoke an emotional language; such terms as “brother” and “brotherhood” encouraged members to think of their ties as akin to consanguinity. In a time of massive migration when universal suffrage had only recently been won in many countries, appeals to that alternative sense of community resonated among many workers.[10]

Sacco and Vanzetti identified wholeheartedly with that community, as part of a network of anarchists stretching from Switzerland, France, and Italy to Uruguay and Argentina. While the growing strength of syndicalism and socialism and the founding of the Third International in 1919 signified the declining influence of anarchism, some radicals continued to subscribe to the antistatist and individualist doctrines set out by such theorists as Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. Sacco and Vanzetti were among them. After migrating to the United States in 1908 from Italy, the two young men had become committed to the ideals of “direct action.” They belonged to the secretive, ultramilitant circle of Italian anarchists around Luigi Galleani, whom Vanzetti once acknowledged as their “master,” a charismatic man who romanticized violence as a legitimate response to injustice.[11]

While the Galleanistas’ emphasis on the “propaganda of the deed” placed them on the extreme end of the left-wing political spectrum, their strong identification with global proletarian solidarity was at the core of radical worker politics. Anarchists, syndicalists, socialists, and Communists shared it. The movement to rescue Sacco and Vanzetti could mushroom because of those dense international connections. Galleani, whom Sacco and Vanzetti had met when he lived in the United States from 1901 to 1919, had lived in Italy, France, Switzerland, England, Egypt, the United States, and Canada. Although both Sacco and Vanzetti had resided in the United States for most of their adult lives, they had spent a year in Mexico with a group of Galleanista militants in 1917. They returned to the United States, but some of their companions moved to Italy and others to South America; they thus had personal connections with anarchist militants beyond the borders of the United States. Throughout their long years of imprisonment, they deepened these contacts, writing to anarchist compatriots in places such as France and Argentina, requesting aid, receiving news of the worldwide activities on their behalf, and pressing for further mobilization. Sacco and Vanzetti’s political and mental world was framed as much by the far-flung international community of anarchists and radical “masses” as by the local communities in which they lived and the Gruppo Autonomo, the Italian anarchist organization in Boston of which they were part.[12]

The international contacts of this close-knit circle of Galleanistas spread the first news of their arrest and conviction, but the Galleanistas’ emphasis on the propaganda of the deed and their distrust of institutions, including labor unions, made their brand of internationalism far too antiorganizational to support a broad social movement. A broader group of radicals who took up the men’s cause had the institutional connections to do that. In the United States Carlo Tresca, an iconoclastic radical, quickly contacted his leftist allies asking for their help. Tresca brought in Fred Moore, a radical lawyer who, with the local Boston attorneys Jeremiah and Thomas McAnarney, was initially in charge of the men’s defense. Fred Moore earlier had been one of the legal team that won acquittal for the syndicalists Arturo Giovannitti and Joseph Ettor, who were tried for murder in connection with the 1912 “Bread and Roses” strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Moore devoted his energies not only to pursuing courtroom strategies but also to building a movement of labor solidarity.[13] He corresponded with union leaders, socialists, and Communists in the United States and abroad, tapping the connections he had developed through his years in labor circles. His experiences during the trial of Giovannitti and Ettor had made him keenly aware of the possibilities of international solidarity.[14]

To build a movement, Moore first worked to link the cause of Sacco and Vanzetti with that of organized labor, viewing the case as “the pivot around which class struggle in America is to swing.” Given Sacco and Vanzetti’s marginal involvement with unions, Moore knew his attempts were tenuous, and, in letters to close allies, he worried about convincing labor leaders. He hoped to use the international labor movement to overcome the “standpatism” of the American Federation of Labor and prod it to take a stand on the case. He wrote to his friends in Italian labor circles, asking them to persuade the Italian “Federation of Labor” (that is, the Confederazione Generale del Lavoro) to issue a statement supporting the two men. One friend, a new member of the Italian parliament, replied, “My Dear Comrade Moore, ... I am willing to work with the best of my forces.” Moore also sent the young journalist Eugene Lyons of the New York–based Workers Defense League to Europe to spread word about the case. Moore and Sacco and Vanzetti’s supporters more broadly had far greater success with central organizations of labor outside the United States than domestically. The American Federation of Labor passed resolutions in 1922 and in 1924 in favor of the two men but provided little other tangible support. Local and state federations of labor more often gave support, and rank-and-file workers at times expressed their solidarity generously: A meeting of unemployed silk workers in New York City in 1922, for example, raised over seventy dollars. Such support, however, came largely from the ranks of the immigrant and unskilled; the mass of skilled native-born workers remained indifferent.[15]

Moore and close allies such as Elizabeth Gurley Flynn also appealed to radical organizations. They met a receptive audience in the tiny Communist organizations just forming in the United States. In 1921 the Communist Workers Party of America called for a campaign of solidarity. The recently founded Executive Committee of the Communist International in Moscow picked up on this call and appealed for a worldwide campaign of solidarity in the fall of 1921. The Russian Revolution had just unleashed radical political imaginations in countries throughout the world. Now supporters of the newly emerged “worker state,” through newborn Communist parties, took up the banner of Sacco and Vanzetti as victims of “bourgeois class warfare” whose plight might also bolster support for the parties.[16]

The Sacco and Vanzetti case, then, gained visibility in part because it took place at a transitional moment in radical politics. In the 1920s anarchism, a significant current of radical politics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was declining and its supporters were seeking a new lease on their political life. The Communist parties had just been founded. Both groups vied to strengthen their causes by championing Sacco and Vanzetti. In the first weeks of October 1921, demonstrations took place in London, Rome, and Paris. In Le Havre, France, on October 10, 1921, brilliant red posters throughout the city declared the verdict unjust. In the following weeks the American consulate in Marseilles received police protection because of the “quite formidable” demonstrations in front of it, according to an American consular official. By the end of the month, three thousand organized workers marched in the streets of Santiago, Chile, condemning the “capitalist governments of the world and demanding the liberation of the Italians Sacco and Vanzetti,” and in Basel, Switzerland, according to the consular official there, protesters outside the U.S. consulate “made speeches and threatened him with death.” In the Netherlands, early in November, the Hague Trade Committee, the Communist party and the Revolutionary Socialist Women’s League met to protest the death sentence, which they linked to the “life and death of revolutionary workers of all countries.”[17]

Protests sometimes led to violence. In Paris on October 20, 1921, the American ambassador, Myron Herrick, was sent a mail bomb. Shortly thereafter, during a meeting at the Salle Wagram in Paris, some protesters threw a bomb at the police. Over the following weeks, numerous American government targets were bombed. On October 31, 1921, in Portugal, a bomb ripped through the U.S. embassy in Lisbon. An explosion damaged the American embassy in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the next day. In Switzerland the front of the American Consulate in Zurich was blown out, and on November 8 a bomb damaged the American consulate at Marseilles. While the bombings hardened a segment of public opinion against the two men, they also brought the Sacco and Vanzetti case prominently onto the international stage. One radical wrote to defense lawyer Fred Moore about the dual consequences of the bombings, “I can appreciate the difficult position you were placed in by the Paris happening. However, a byproduct of that event is far greater international interest than before.”[18]

While international interest spread from Chile to New Zealand, in a number of countries—Italy, France, Argentina, and Mexico particularly—political mobilization deepened. Those countries had powerful radical movements strongly influenced by anarchism and anarcho-syndicalism. All of them had just witnessed the birth of rapidly growing Communist parties, often founded with the support of former anarchists, that became the leading champions of the men’s cause.

Italy’s militant antistatist currents, deep class rifts, and strong localism had generated a vibrant anarchist movement, which since the late nineteenth century had been rocked by periodic bursts of insurrection and violence. A wave of labor unrest in the early postwar years culminated in September 1920 when workers seized industrial plants in Turin and Milan. While Italy’s biennio rosso (two red years) ended in late 1920, violent clashes between the radical Left and Benito Mussolini’s shock troops took their place, ending with Mussolini’s ascent to power in 1922. Italy was not only home to powerful militant left currents—from socialist to anarchist—but also Sacco and Vanzetti’s native land, amplifying the case’s resonance there. Errico Malatesta, Italy’s preeminent anarchist, and his newspaper, Umanità Nova, propelled Sacco and Vanzetti’s cause forward. Radicals from the United States also spread the word of the men’s situation throughout Italy. Eugene Lyons, carrying a letter of introduction from Fred Moore, placed articles about the case in leftist newspapers and helped set up an Italian organization to coordinate efforts with the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee in Boston. “I have little doubt,” Lyons reported to Moore, “but that a nationwide agitation for the two boys is in the making.” In the year following Sacco and Vanzetti’s trial and conviction, meetings in support of the two were held “all over Italy,” according to the American consulate in Florence. Meetings emphasized that the men were condemned because they were labor agitators and Italian immigrants. In 1925 the U.S. embassy in Rome received petitions with thousands of signatures protesting the verdict. By 1927 the American ambassador in Rome reported to the State Department “that public opinion here was almost universally against their execution.” The Fascists’ rise to power in 1922 kept demonstrations and protests rare; those that took place were swiftly crushed. While Mussolini allowed some public expression of support for the two men in newspaper articles and eventually worked behind the scenes for clemency, American government officials in Italy were grateful to the Fascist police and government for containing protest. As H. P. Starrett of the American consulate in Genoa put it, the “lack of incidents in Genoa is due not to indifference but to the strictness of the discipline enforced by the fascist government. If it had not been for the very careful measures taken by the authorities no one doubts but that the public here would have expressed its mind in no uncertain manner. It is to be hoped that this discipline will continue until the people have forgotten the case.”[19]

In France, where the government was not willing to resort to such repressive measures, protest flourished. As in Italy, anarchism had deep roots in France. Since the late nineteenth century, violence had periodically flared up. As anarchists competed with syndicalists, socialists, and Communists, the leading anarchist newspaper in the 1920s, Le Libértaire, kept up a drumbeat of news concerning the case. Indeed, Sacco and Vanzetti were a major preoccupation of the French anarchists in the 1920s. The organized labor movement, deeply influenced by anarcho-syndicalist currents, aided the anarchists in their efforts. The Conféderation Générale du Travail (cgt), born of these tendencies, served as one institutional force for solidarity with Sacco and Vanzetti. The birth of the Communist party in 1920 provided yet another champion. Even though these organizations often clashed on strategy, they formed an impressive base from which to mobilize. The French Communist party took the lead in mobilizing in solidarity with the two men. The case served as one of the only issues around which the Communists were able to build a successful popular front during the decade.[20]

While Sacco and Vanzetti’s conviction caught the attention of French and Italian workers, workers elsewhere in Europe remained on the margins of the developing international protest. Germany, for example, boasted a powerful organized labor movement, but in the first years of the case, Social Democrats there held themselves aloof from the men’s cause. They were wary of naming two militant anarchists working-class heroes and preoccupied with their own factional struggles against militant Communists and anarchists. By the mid-1920s, however, when the case gained increased attention, even moderate socialists throughout Europe joined in the outcry. The Swiss Socialist newspaper Le Droit du Peuple introduced its readers to the case in 1925 in an ambivalent tone: “A painful and curious affair is beginning ... to agitate public opinion in Europe ....We must save the innocents no matter who they are.... If we could become impassioned by a permanent army captain” (referring to the unjust conviction of the French officer Alfred Dreyfus for espionage and the campaign that ultimately vindicated him), “we must [be] even more so when it comes to two militant workers, no matter what their tendency or their affiliations.” After the Massachusetts Supreme Court refused to grant the men a retrial in April 1926, even the German Social Democrats became part of the popular front around the case, labeling the men’s death sentence “judicial murder.”[21]

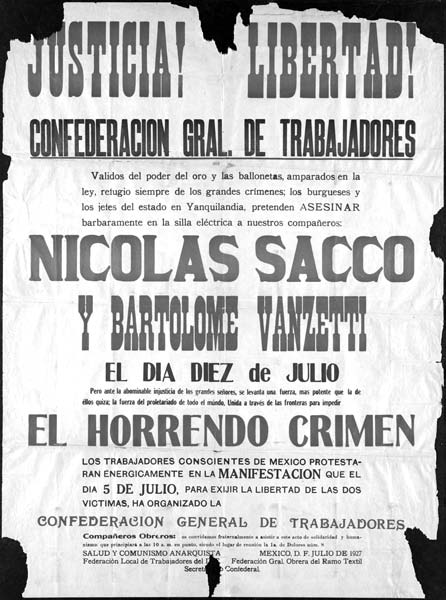

As in Europe, Communists and anarchists took the lead in championing the men’s cause in Argentina and Mexico. In Mexico anarchism had formed a dominant current of left politics. Indeed, Mexican anarchism had provided a hospitable temporary home for Sacco, Vanzetti, and their Galleanista companions, who had gathered in Monterey a few years earlier. With the founding of the Mexican Communist party in 1920, anarchists suddenly found a strong competitor for the allegiance of radical workers. While the Mexican Communist party struggled to dominate, and differentiate itself from, the largely anarcho-syndicalist radical milieu from which it sprang, the Sacco-Vanzetti issue provided one point of unity with the country’s anarchists. The Mexican Communist party boasted a membership of only a few hundred in the early 1920s; by the end of the decade it had become the most successful of the Latin American Communist parties. Embracing agrarianism clearly played a major role in its success, but championing Sacco and Vanzetti’s cause helped the party appeal to some anarchists. In addition, Mexican working-class resentment against the country’s Yankee neighbor ran high, particularly in the wake of the Mexican Revolution. The sympathetic left-leaning revolutionary government, plus a highly organized syndicalist labor movement, helped build protest against the treatment of Sacco and Vanzetti. News about the case spread quickly, aided by North American radicals who had published detailed accounts by 1921 and by the Spanish-language paper of the Industrial Workers of the World (iww), Solidaridad. Mexican radicals mobilized early and powerfully in support of Sacco and Vanzetti. By 1921 the U.S. consulates in Veracruz, Tampico, Mérida, and Guaymas were already confronting demonstrations and protest. The Syndicate of Truck Drivers of the Port of Veracruz raged with a virulence rarely matched elsewhere: “Free Sacco and Vanzetti or the proletarian world will rip out your guts. We do not ask pity.... If you are implacable we also will be implacable. An eye for an eye! ... The law of retaliation will be served if our brothers are not freed.”[22]

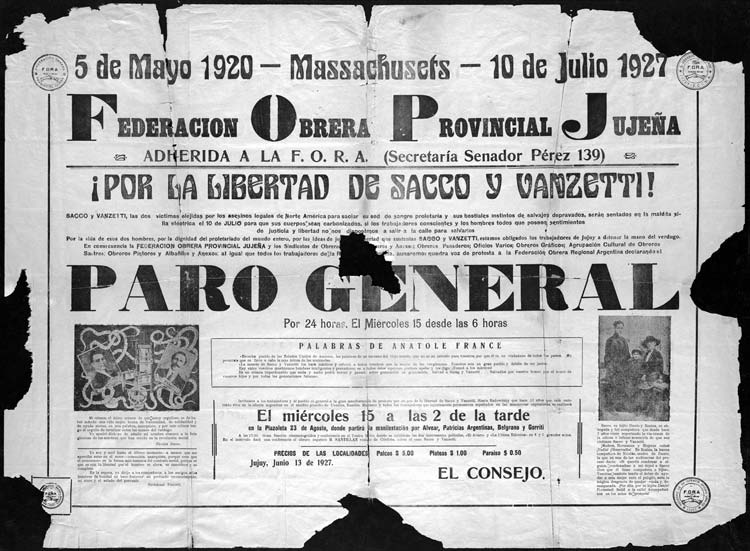

Radicals in Argentina also took up Sacco and Vanzetti’s cause wholeheartedly, but there anarchists—not the Communist party—took the lead. As a result, anarchism revived there, at least temporarily. In the South American nation, much to the consternation of the ruling elite, anarchism had proved attractive to the immigrant workers who constituted most of the country’s working class in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The organized labor movement led by the Federación Obrera Regional Argentina (fora) was deeply influenced by anarcho-syndicalist currents. By 1921, however, its power was waning. State repression that reached its height in 1919 contributed, but the labor movement was also turning away from confrontational tactics because of the increasing integration of workers into Argentine society, as populist politicians fostered cross-class appeals. By the 1920s anarchist calls for direct action by workers to overthrow capitalism and anarchist belief in irreconcilable class conflict were losing their hold on the loyalties of workers.[23] Anarchist newspapers railed against the working class as a “Republica de serviles,” “a meek beast of burden [that] has lost even the simplest notion of dignity.” The Sacco-Vanzetti case infused fresh life into the movement; discouraged anarchists had found a new mission. For well over a year, the sole preoccupation of Argentine radicals was the liberation of Sacco and Vanzetti. Anarchists may have seen the cause as capable of mobilizing their social base, but its broad resonance among Argentina’s masses expressed less a revived faith in anarchism than an attachment to working-class and ethnic identity at a shifting moment in worker politics. While calls for general strikes during the early 1920s inspired only tepid responses, by 1927 masses of workers did march, strike, and riot to express their solidarity with Sacco and Vanzetti, who had become working-class heroes. One American businessman described “conditions” in the country at the time as “intolerable.”[24]

From France to Argentina, the mobilization around Sacco and Vanzetti can be seen as the tail end of a militant form of class conflict that had been significant in workers’ political action in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The men’s executions marked the death of such radicalism. Worker action and organized left politics had led to growing concessions to workers either through social democratic movements or, as in Italy, corporatist politics. The case also served as a lightning rod for a new cross-class ideology, crystallizing in countries such as France, Germany, Argentina, and the United States, that emphasized the social integration of workers and their enfranchisement as citizens.[25]

The case spoke to both those currents and linked them in one mobilization. The global movement aroused by the Sacco and Vanzetti case both demonstrated a new visibility of the popular masses on the international stage and suggested workers’ increasing integration within nation-states. The case also precipitated a growing concern about the rise of American power after World War I. In Buenos Aires, Argentina, Paris, London, and Milan, workers rallied to Sacco and Vanzetti in the wake of the popular insurrections and explosive worker uprisings of 1917–1919, unleashing their fury at “Yankee injustice.” In so doing, they forged a cross-class mobilization with elites and intellectuals.

If the currents of global radicalism, newly vocal masses, and a shared international working-class identity explain the resonance of the case in its early years, a deepening Italian nationalism was also crucial. Sacco and Vanzetti’s identity as Italian immigrants and their experience of being outsiders and targets of prejudice resonated within the large and far-flung Italian diaspora of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Not surprisingly, support for the two men was strong in their home country, where supporters appealed to the men’s status as “fellow countrymen” and argued that their conviction was due to widespread prejudice against Italians in the United States. In parliament, for example, Leonardo Mucci, a Socialist delegate, linked the case to Americans’ poor treatment of Italian immigrants, expressed most recently in the campaign for immigration restriction. He called on Italians to “show your teeth to America.” Before the Fascist takeover, the Italian foreign minister ordered Rolando Ricci, the Italian ambassador to the United States, to “take every possible step toward the [American] government to secure a pardon for our nationals Sacco and Vanzetti.” Even the preeminent Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta appealed to nationalism, remarking that in addition “to being anarchists, [Sacco and Vanzetti] are also Italians: They belong to a rejected and despised people who can be murdered without concern. Will the patriots of Italy allow that?” Mussolini declared he would not. At a meeting in Milan in 1921, he called on the minister of foreign affairs to “take action to prevent these ... innocent men from being condemned ... merely because they belong to the Italian race and the Italian nation.” After the Fascists took power in 1922, crushing the socialist, Communist, and anarchist opposition, Mussolini spoke more cautiously, fearful both of alienating American officials and of letting the case become a powerful rallying symbol for the anarchists. Still, he worked privately through the Italian ambassador to the United States, who told an Italian newspaper in 1926 that he sought Sacco and Vanzetti’s release “because they were Italians and because they were innocent.” In 1927 Mussolini told American officials that he feared execution of the two men “would provide the pretext for a vast and continuous subversive agitation throughout the world,” and he pleaded with the officials for clemency.[26]

Not just in Italy, but throughout the Italian diaspora, ethnic solidarity contributed to support for the two men. In the early twentieth century, Italians were the preeminent workers of the world. As Donna Gabaccia has revealed, “overall, no other people migrated in so many directions and in such impressive numbers—relatively and absolutely—as from Italy.” Italians flocked to France, the United States, Canada, Argentina, and Brazil, connecting the old country to their new worlds. For such Italian workers, transnationalism was a way of life. The Sacco and Vanzetti case linked their Italian ethnic identities to their broader status as workers of the world. One pamphlet in France noted that “before they were internationalists, Vanzetti like Sacco were Italians. They intensely love their brothers thrown into the new world.” In France it was also argued that widespread American hostility marked people of their nationality for poor treatment.[27]

In such places as France and Argentina, ethnic identity and traditions of workingclass radicalism were often inextricably linked. Since the 1890s Italian emigrants had been heading to France in great numbers, and they had shaped the labor movement in France’s Italian colonies, such as Marseilles. In the 1920s, with doors to the United States closed, France became the number one destination for Italian emigrants. Many radical workers, threatened with violence and repression in Mussolini’s Italy, moved across the border. There were nearly 1 million Italian immigrants in France by 1927. And Italians were, according to police reports, the most political and the most receptive to labor and left politics of all immigrant groups. Organizations such as the syndicalist cgt and the Communist-led Conféderation Générale du Travail Unitaire (cgtu) attracted many Italian members for whom ethnic and class identities often meshed: By 1930 in Paris alone there were 6,000 Italian members of the cgt. Nationwide the cgtu had 12,000 Italian members, and the French Communist Party (pcf) between 5,000 and 10,000. According to one scholar, “Italian immigrants represented in certain regions the proletarian base of the party.” The Communist party newspaper, L’Humanité, at times printed notices for meetings in support of Sacco and Vanzetti in Italian and often announced that “Italian speakers” would be at the podium.[28]

The fusion of working-class and ethnic identities also undergirded the powerful currents of protest in Argentina. By 1914 nearly one-third of Argentina’s population of 8 million was foreign-born, and many were from Italy. In Buenos Aires, about 20 percent of the population was Italian-born. And in the city of Rosario, as late as 1926, foreign-born immigrants, Italians foremost, accounted for 45 percent of the population. Italians were also influential in shaping the anarchist currents that had dominated the Argentine labor movement since the late nineteenth century. Even in the 1920s, La Protesta, a widely circulated anarchist daily, experimented with Italian-language sections and printed notices for meetings in solidarity with Sacco and Vanzetti in Italian. In announcing meetings for Sacco and Vanzetti, other anarchist papers sometimes stated that Italian speakers would be present. Moreover, Italian immigration to Argentina in the 1920s, just as in France, took on an increasingly politicized cast, as dissidents escaping Mussolini’s Italy made their way across the south Atlantic Ocean. One of Sacco and Vanzetti’s greatest champions was the immigrant Severino Di Giovanni, who landed in Argentina in 1923. He opened a workers’ library, founded the newspaper El Culmine, and eventually turned to a campaign of violence to rescue Sacco and Vanzetti and to inspire revolutionary insurrection. Di Giovanni was most likely responsible for bombing the American embassy, a statue of George Washington, a Ford Motor Company office, and two U.S. banks operating in Buenos Aires.[29]

While urban terrorists such as Di Giovanni and the larger Italian anarchist community were the most steadfast champions of Sacco and Vanzetti, other Italians rallied behind the men for other reasons. Italian nationalism in the 1920s brought together seemingly unlikely bedfellows. Conservative Italians in the diaspora sought to make the case one about nationalism, not radicalism. Indeed, Italians—whether anarchists or Fascists—were united on one point: Sacco and Vanzetti’s plight was due, in no small part, to their status as Italian immigrants. As a result, many Italian immigrants, from Buenos Aires to New York, could rally behind Sacco and Vanzetti while simultaneously exalting Mussolini.[30]

In the United States the Order Sons of Italy in America—urged on by conservative Italian American prominenti, including Fascists, who had formed the Comitato Pro SaccoVanzetti—swung behind the defense. Luigi Barzini, the editor of an Italian daily in New York and a Mussolini supporter, threw his newspaper behind the men, noting that “whatever ideas Sacco and Vanzetti have are unimportant.” He urged the creation of an Italian American “united front” in favor of the two. The committee he organized arranged a benefit opera performed by singers from the Metropolitan Opera Company of New York and attended by prominent Italians as well as labor leaders.[31]

While the rise of nativism in the United States in the 1920s and widespread hostility to migrants from southern Europe contributed to this effort to forge an Italian united front, even in Buenos Aires, where ideological lines were far more starkly drawn and Italians more integrated, Italians from across the political spectrum supported the two men. In 1927, when the American Chamber of Commerce sought to place paid advertisements in both L’Italia del Popolo and La Patria degli Italiani (as it did in many other Argentine newspapers) detailing the history of the case to counter “erroneous understandings” and “deep misperceptions” about “American procedure in criminal cases,” they were refused. Chamber members were not surprised that the socialist L’Italia del Popolo would turn them down, but they were much astonished that La Patria degli Italiani, “a very serious paper,” should do so. And, on the eve of the execution, the General Federation of the Italian Societies of the Argentine Republic cabled Massachusetts governor Alvan Fuller, imploring him to save Sacco and Vanzetti from death. The Italian nationalist sentiment supporting the two men was diverse. For left-leaning Italian anarchists, it was an ethnic affinity that firmly rejected loyalty to the Italian state. Indeed, the case offered a means for antifascist Italians to build an alternative nationalism.[32]

If nationalism helped build support for Sacco and Vanzetti across class and political lines, so did a broad quasi-racial and cultural identity. In terms picked up from popular 1920s pseudoscientific discourse, Sacco and Vanzetti were identified as “Latin” in contrast to their “Yankee persecutors.” The French grouped themselves with the Italians, identifying both as part of “la grande famille Latine.” One French defender of Sacco and Vanzetti wrote that “the revolt of these two men against the mechanical monster was born first of all of a sentimental Latinism.” In Argentina, even anarchist papers such as La Protesta, not given to ethnic or geographic characterizations of peoples, remarked on Yankee plutocracy as a distinctive “Northern” characteristic that contrasted with the habits of “the people of the South.”[33]

In some countries the combination of ethnic and class identities fueled a potent movement and accounted for its incredible resonance. Where strong anarcho-syndicalist currents, traditions of left radicalism, and large Italian diaspora communities intersected, the cause unleashed a tremendous reaction, which then echoed in other countries. Protest begot more protest. By 1924 officials at American consulates in countries as diverse as China, Paraguay, Germany, Sweden, Norway, and England wrote to their superiors reporting demonstrations protesting the convictions of the two men. Yet the extent of interest the case sparked varied in different regions of the world. While the agitation led embassy officials elsewhere to refer to the “Sacco and Vanzetti crisis,” the American consul in Java requested to be taken off the list of embassies and consulates receiving cablegrams about the case, since there was “no interest in that case whatever, either one way or the other, in this country.”[34]

The movement spread as widely across the globe as it did as a result of another great development of the age: mass communications. Turn-of-the-century revolutions in print and communications technology enabled far-flung communities to follow the twists and turns of the case. International telegraphic communication had enabled elites to stay abreast of global developments in the last third of the nineteenth century, but now the communications revolution had filtered down to the working classes. Labor and radical movements in much of the world had established their own newspapers and were publishing their own books and pamphlets. The democratization of access to knowledge facilitated transnational collective mobilization. Hundreds of thousands of workers followed the case closely, in the final months daily. In France they read Le Libértaire; in Germany, Rote Fahne and Vorwärts; in Argentina, La Protesta. Jose Marinero, a member of the Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Committee, reported for the Argentine audience direct from Boston. For years La Protesta devoted several of its weekly and biweekly supplements exclusively to the case. Dozens of smaller Argentine newspapers, from Bahía Blanca’s Brazo y Cerebro to the Buenos Aires–based La Antorcha and El Libertario, also gave much attention to the case.[35]

Sacco and Vanzetti entered the pages of those newspapers as workers in the West were becoming increasingly literate, thanks to the spread of mass education and labor unions’ successful struggle for more leisure time. Working-class culture in the 1920s in countries such as Argentina, France, Germany, the United States, and England was increasingly a reading culture. In Argentina a vibrant popular culture centered on libraries and books flourished. Some libraries served as institutional spaces for organizing in favor of Sacco and Vanzetti. Similar popular libraries sprouted in France and Germany. New publishers catering to working-class audiences sprang up. Workers developed an intimate knowledge of the case not only from newspapers but also from pamphlets and cheap pocket books.[36] For working-class audiences, the ordeal of the two Italian immigrants since their arrest, the details of their lives, their hopes and dreams, and their pleas for aid became the drama of two working-class heroes. The anarchist press, especially, revealed the men as flesh and blood militants. Workers read reprinted versions of Sacco and Vanzetti’s letters and cards to family and friends. When the protagonists called for more mobilization to save their lives, it was a direct appeal.[37]

Not surprisingly, Sacco and Vanzetti’s story varied depending on who was communicating it, how, and why. Radicals and conservatives sometimes circulated completely different tales about Sacco and Vanzetti and their politics. Le Figaro in France and El Excélsior in Mexico, both conservative newspapers, cast the two men as “Communists” for whom the Communists would perforce agitate. The international Communist parties portrayed them as respected and well-known revolutionaries. As one poster plastered throughout the city of Le Havre in October 1921 explained, Sacco and Vanzetti “were militant revolutionaries ... carrying on an active and successful propaganda in America in favor of their beloved ideals of social renovation. Gifted with exceptional intelligence ... they soon attracted to their generous doctrines thousands of admirers.... Unfortunately, as is always the case in such circumstances, they drew upon themselves numerous and serious troubles.”[38]

Not only were the men mythologized in a misleading way, but the facts of the case were sometimes distorted. Communists in different parts of the world developed their own “truths” about the case. Words attributed to Webster Thayer, the presiding judge in the case, for example, were translated in a similarly distorted manner in several countries. Thayer was quoted in France, Germany, and the Netherlands, and very likely elsewhere, as having said that even if the two men “did not participate materially in the crime with which they are charged, they are morally guilty ... because they are enemies of existing institutions, because they are anarchists ... and that is a crime in itself.” While those words may have crystallized Judge Thayer’s sentiments, there is no written record that he ever uttered them. Their origins are difficult to trace, but they seem to lie in Communist party literature.[39] Yet they soon became a part of the lore of the case still remembered today. As that example suggests, stories told about the case at times strayed far from the facts and responded to local circumstances and the audience they were intended for. In China and Sweden, for example, radicals emphasized issues of police and government corruption. Speakers at meetings about the case in both places claimed that Sacco and Vanzetti had “certain documents” that might compromise police authorities, which explained their “persecution.” Many stories suggested that the judge or the jury had been bribed and that the government had offered a reward for the arrest of those involved in the holdup. Although untrue, those tales heightened the case for outrage. No doubt the details resonated because audiences found them plausible.[40]

While Communist party literature tended to turn the two men into revolutionary leaders, alternate representations, equally sympathetic to their cause and equally false, portrayed Sacco and Vanzetti as simple workingmen caught in the wheels of an unjust legal system. In the United States, for example, as Fred Moore sought to link the two men to organized labor, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, an American radical closely involved with the cause, objected. As she wrote to Moore, “being unknown, they had no labor enemies.... The simple cry ‘Save Sacco and Vanzetti,’ has power ... it is a dynamic slogan. For heaven’s sake, don’t lose it in a mass of other issues. Europe ... respond[ed] to the human appeal and simple pathos of Sacco and Vanzetti. Their very obscurity and helplessness made them powerful.”[41] Gurley Flynn’s words, written in 1921, proved prescient. As the two men became malleable symbols for different groups drawn to the case, the plight of the simple “fish peddler” and “shoemaker” became the dominant rallying point for the civil libertarians, intellectuals, writers, and artists who eventually became Sacco and Vanzetti’s leading champions. The discourse increasingly emphasized the “simple pathos” of Sacco and Vanzetti. By 1926, after the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts upheld their conviction, the mobilization had transcended its original social base. The global drama concerning Sacco and Vanzetti moved into its second act.

Between 1926 and 1927 middle-class citizens and intellectuals in Europe and Latin America joined what had become a popular front mobilization. The prejudiced climate in which the trial took place, the deep animosity toward anarchists and foreigners expressed by the judge and the foreman of the jury, and the shaky and contradictory prosecution evidence—all created strong doubts that the men had received a fair trial. With request after request for a retrial falling on deaf ears, prominent intellectuals and political figures such as Felix Frankfurter began to condemn the verdict as a judicial outrage. By early 1927 an increasingly broad swath of “respectable opinion” around the world had become deeply critical of the American system of justice and the “deafness” of U.S. government officials to international opinion. For such women and men, not Sacco and Vanzetti, but American justice was on trial. The case was called the “American Dreyfus” affair, referring to the infamous trial of Alfred Dreyfus, a French army officer accused and convicted of treason in late nineteenth-century France in a blatant case of anti-Semitism that drew international attention. As one Danish newspaper, the Nationaltidende, put it, “Exactly like the trial against the since pardoned French artillery Captain ... the Sacco and Vanzetti trial has in the course of a similar period developed slowly from an American affair into an international affair.” Some argued that Sacco and Vanzetti’s plight presented an even more obvious injustice than that of Alfred Dreyfus. Another Copenhagen newspaper remarked, “Just because Dreyfus was innocent, Sacco and Vanzetti need not be so.... But there are far more positive, tangible and strong reasons to believe in a judicial fallacy ... now than there was for a long time during the Dreyfus case.” Such parallels were drawn again and again and became a shorthand way of saying the case was another great miscarriage of justice. With historical hindsight, the differences between the two cases, particularly the dynamic role of the labor movement in the mobilization to save Sacco and Vanzetti, are at least as great as their similarities. But the parallels were not without foundation. Both trials drew enormous international attention. While the question of guilt or innocence was more easily resolved in favor of Dreyfus than of Sacco and Vanzetti, both trials were marked by prejudice and unfair treatment of the defendants. Most of all, intellectuals helped make both cases causes célèbres.[42]

From the beginning, defense lawyer Fred Moore had hoped to mobilize liberal elite supporters. In 1921 Moore urged Gurley Flynn to contact American Civil Liberties Union leader Roger Baldwin, saying he himself would contact Frankfurter. He also urged the journalist Upton Sinclair to visit Vanzetti in prison. Deeply moved, Sinclair published an account that painted Vanzetti with a halo of innocence around him, declaring him “simple and genuine, open minded as a child.” As liberals and intellectuals came to their defense, the men’s militant politics were defanged, and they were recast as “philosophical” anarchists. Sinclair offered, as he put it, his “testimony” in the court of public opinion: “this humble working man is precisely what he pretends to be, an idealist and apostle of a new social order. I should consider him just about as likely a person to be guilty of highway robbery and murder as I myself should be.” Making Vanzetti a palatable protagonist for middle-class audiences, Sinclair noted that Vanzetti “possess[ed] that innate refinement which makes good manners without need of teaching. He has devoted his life to the service of his fellow wageworkers.” Sinclair’s views were shared by intellectuals in other countries, some of whom had already begun speaking out in favor of the two men.[43]

Moore and those close to him expressed continual disappointment with the tepid support they mustered from liberals in the first years of the case. Moore’s close associate Selma Maximon, working to drum up support in Chicago, lamented that “no one is going to the public platform for these two boys except a handful of ultra radicals.... We need every ounce of energy of the liberals.”[44] Only after William G. Thompson, a prominent Boston lawyer, replaced Moore on the defense team in 1924 did liberals and intellectuals come increasingly to the fore. As appeal after appeal failed and the possibility of execution seemed ever more real, the case took on the dimensions of high moral drama. Just as the Dreyfus case had influenced a generation of intellectuals in France in the late nineteenth century, the Sacco and Vanzetti case contributed to a budding social conscience among a generation of artists and writers in the United States whose experiences of war had turned them toward pessimism and disillusion. These American elites were affected by the transnational currents that swirled around the case and themselves influenced its global visibility. And like radicals and labor activists, American intellectuals of the 1920s were embedded in transnational networks.[45]

Writers and artists during the 1920s embraced cosmopolitan identities with a vengeance, renouncing the nativist, puritanical impulses in American culture at that time. American writers and artists frustrated with the United States, including Malcolm Cowley, Katherine Anne Porter, Ben Shahn, John Dos Passos, and Ernest Hemingway, left for long sojourns in such places as Spain, Mexico, and France. Expatriation was considered “a method of liberation from the Philistinism of the 1920s.”[46] Some moved to Europe; others to Latin America. Abroad, such American artists and writers interacted with political radicals of all stripes, from anarchists to Communists. Their experiences made them see the world and at times the case through different eyes. When they returned from abroad, the case deepened their new social commitments and magnified their concerns about the deep rifts in American life and their hopes to rectify them.

Porter, a writer who became deeply involved in their campaign, wrote years later that her attention was first drawn to the case during the years she spent in Mexico in the early 1920s: “On each return to New York, I would follow again the strange history of the Italian emigrants Nicolo Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.” Shahn, who studied in Europe in the 1920s and whose art was profoundly shaped by the case, recalled years later the demonstrations he witnessed in support of the two men in Paris. At the time Dos Passos was the best-known of the writers involved with the case. He had lived in both Spain and Mexico, where he encountered anarchism and developed his sympathy for it. He saw the men as anarchists and believed that was the basis for their persecution. The case, as the critic Alfred Kazin remarked, transformed “his persistently romantic obsession with the poet’s struggle against the world into a use of the class struggle as his base in art.” Malcolm Cowley, who lived in France in the 1920s, wrote that the case taught his generation of intellectuals the need for “united political action ... the intellectuals had learned that they were powerless by themselves and that they could not accomplish anything unless they made an alliance with the working class.”[47]

The involvement of intellectuals and writers such as Sinclair, Dos Passos, and Frankfurter in the defense of Sacco and Vanzetti brought the movement a respectability and visibility previously unobtainable. Transnational connections were thus a two-way street: American intellectuals were influenced by currents of radical politics abroad, and they introduced new foreign audiences to the case. Newspapers across the world, for example, discussed Frankfurter’s criticisms of the case, and his book on it provided the facts and analysis for innumerable pamphlets and histories published around the world. Pleas for the two men written by Frankfurter, Dos Passos, Sinclair, Anatole France, and Hans Ryner were reprinted throughout Latin America and Europe. Extremely prominent individuals joined the chorus: Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Thomas Mann, Kurt Tucholsky, H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, and Diego Rivera. Some spoke out against the death sentence; others actively organized protests.[48]

The case contributed to an increasing turn toward social action among American intellectuals, a commitment that deepened in the depression years.[49] Yet, the response to the case suggests that many intellectuals were conflicted about this newfound social activism. European and American intellectuals of their generation were deeply influenced by the disillusionment that resulted from World War I. That disillusionment expressed itself in the literary themes of passionate individualism and fierce independence, a yearning to escape the safety and tedium of bourgeois society, and a heroization of living outside the law. In France, in particular, anarchist thought was in vogue in intellectual and literary circles. In Sacco and Vanzetti, writers and artists already dismayed with a world they saw as bent on destroying individuality found two strident individualists who faced execution because of their militancy and rejection of bourgeois norms. The two men, then, became symbols of the struggle for the survival of individualism in a period of anxiety and frustration over its possible loss. Here, perhaps, social commitment might serve to rescue individualism.[50]

Discourse about the case expressed anxiety not only over the survival of individualism in the modern world but also over the heightened power of the United States in the wake of World War I. That the trial took place in the United States, the new world center of business and capital, is critical to understanding its international influence. Hundreds of injustices of equal weight had occurred in other parts of the world, but Latin America’s long-standing resentment of the power and influence of the United States and Europe’s growing concerns about the increasing power of Uncle Sam meant that this injustice stood out. Through critiques of the mens’ plight, intellectuals hoped that the “de-Godding of America,” as one German journal put it, would begin.[51]

In Latin America, both elites and the lower classes complained of the arrogance of Yankee power, and hostility to the United States reached a new high point when the United States reoccupied Nicaragua in 1926. The case of Sacco and Vanzetti heightened those sentiments; according to American capitalists in Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina, it was “inflaming public opinion ... to the great detriment of American business interests and ... endangering innocent lives.”[52] In Europe, the United States’ postwar replacement of Great Britain as the world’s major economic power heightened scrutiny of American claims to be bringing freedom and democracy to the world. The Sacco and Vanzetti case raised concerns about American intolerance, prejudice, and disregard for civil liberties, not to mention calling attention to the faults and inefficiences of its justice system. By 1927 the American legal system had become the target of European critics representing both ends of the political spectrum: Conservatives questioned why it took so long to carry out a sentence imposed by a court of law. Many others condemned the death sentence per se. By the eve of the execution, there was virtually unanimous accord in many countries that the Massachusetts authorities should grant clemency to the two men, given the doubts about their guilt.[53] Yet the framing of such criticisms of the United States was more complex than the reductionist term “anti-Americanism” might imply. As one newspaper in Denmark, the Politiken, put it in August 1927, “If it were only in Russia or some other barbaric country that such a judicial murder were committed for political reasons. But America, the United States of America! If such a thing happens there, the wholesome sense of justice of mankind will feel deeply wounded.” And as another Danish newspaper, the Ekstrabladet, proclaimed, “America, which formerly was the country of liberty, has begun a new role: that of reaction ... which is preparing to assume world hegemony.”[54]

By 1927 not only radical publications, but the mainstream mass media charted, and spread news of, the case. The U.S. embassies circulated detailed reports on what newspapers around the world were saying about the case, noting with disgust and concern the widespread criticisms of the American legal system they were hearing. U.S. embassy officials in Norway remarked that “the bourgeois press and a deploringly large number of non-radical citizens express doubt as to [Sacco and Vanzetti’s] guilt.” In Latin America the negative press attention led representatives of American business interests there to write letters to the United Press, Associated Press, and the International News Service in the United States, complaining that the dispatches published regarding the Sacco-Vanzetti case “are almost entirely Anti-American.” In Copenhagen embassy officials remarked that “all shades of political opinion, some moderate, others in highly inflammatory language” rejected the sentence of Sacco and Vanzetti. In Uruguay, according to a U.S. legation official, the press followed the trial to “an almost unbelievable extent,” with Communist and conservative newspapers agreeing that Sacco and Vanzetti should not be executed.[55]

In August 1927, after Governor Fuller of Massachusetts refused to grant clemency, a tidal wave of outrage and indignation swept Europe and Latin America. In Germany that summer, demonstrations in Hamburg, Berlin, and Leipzig turned violent and bloody. A wide spectrum of the press in Berlin, the German capital, expressed doubt that justice had been done, with Social Democrats declaring the sentence “Justizmord” (judicial murder). Influential politicians such as Paul Löbe, president of the Reichstag, joined the loud chorus of dissent. In France a massive demonstration was held in the Bois de Vincennes on the outskirts of Paris on August 8, with between twenty-five and seventy-five thousand participants waving banners and demanding clemency for the two men. In neighboring Switzerland mobs attacked the American consulate. In Denmark U.S. embassy officials escaped mob violence, according to the American ambassador, only because the “forces of police” protected them. In Latin America hostility toward the powerful neighbor to the North rose to critical levels. On the eve of the execution, Sacco and Vanzetti sympathizers mobilized from Mexico to Argentina, staging general strikes in Guadalajara, Mexico, and Montevideo, Uruguay. Embassy officials reported that in Guadalajara on August 10, “all stores were closed, all means of transportation stopped, and no private automobiles were allowed in the streets.” At the request of American consular officials, Mexican troops patrolled the section of the city where Americans lived. In Montevideo shops were closed, newspapers suspended publication, and each streetcar carried an armed soldier. U.S. embassy officials remarked on the “excited state of public feeling against us in connection with this trial which has spread to all classes in this country.” In Mexico City movie theaters interrupted their showings for a half hour to protest the men’s fate. “Whether one likes it or not,” wrote the Parisian Journal des Débats in August 1927, “the fate of Sacco and Vanzetti has assumed international importance.” In Munich the cover of a weekly magazine depicted an agitated crowd with a caption remarking on the “storms” of protest that raged in Germany and throughout Europe.[56]

For the State Department, the agitation was deeply worrisome. The early mobilization in Mexico led embassy officials to distribute a circular letter “containing a true explanation of the Sacco-Vanzetti case.” And as early as 1922, State Department officials in Washington, D.C., remarked that “in view of the many inaccurate reports which have appeared in the foreign press regarding the cases of Messrs. Sacco and Vanzetti, the Department has deemed it advisable to obtain from the authorities of Massachusetts a brief statement of the facts of the cases as brought out upon the trial of the two men.” They closely followed decisions in the case, notifying embassies and consulates when decisions might be handed down so their staffs could prepare for the expected threats and acts of violence and protest. Finally, the department reached the point where simple notification was not enough, and by 1926 officials there appealed to the Massachusetts authorities for advance warning: “we should inform our various missions by telegraph not only that the men have been sentenced because that news will go all around the world promptly enough, but ... we should be able to inform them in absolute confidence two or three days in advance in order that proper precautions can be taken to protect them before it is too late.” The efforts in the United States were mirrored by consulates abroad. In Argentina embassy officials published an extensive updated history of the case, which it released to newspapers with the request that they reprint it to correct against “misperceptions.” American businessmen in Buenos Aires, to ensure widespread dissemination of the embassy’s summary, took out advertisements in newspapers reprinting it in full.[57]

U.S. officials were deeply aware of, and concerned by, the agitation about the case. Governor Fuller’s decision to postpone the execution after his refusal to grant clemency was a response not only to last-minute appeals by lawyers, but to the vast global reaction. But the agitation seemed to have the unintended consequence of hardening officials’ positions. William E. Borah, chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, expressed the view of many officials: “It would be a national humiliation, a shameless, cowardly compromise of national courage, to pay the slightest attention to foreign protest... . The foreign interference is an impudent and willful challenge to our sense of decency and dignity and ought to be dealt with accordingly.” A. Lawrence Lowell, president of Harvard University and a member of the advisory commission convened by Governor Fuller to review the case and consider clemency, wrote to Fuller shortly after the execution, commending him for his decision to carry it out. Fuller, he wrote, was “absolutely right in refusing a commutation ... which would have kept the agitation for a pardon open indefinitely.” Still, he called on the governor to commission an extensive report, hoping it would be of “great value ... for its influence upon foreigners who have gotten a wholly distorted idea of the case.”[58]

The global history did not end with the execution of the two men. It continued well into the 1930s, emerged again powerfully in the 1960s, and is still with us today. The struggle over the legacy of Sacco and Vanzetti began as soon as the two men met their fate in the electric chair on August 23, 1927. With the sentence carried out, they were now elevated to the status of martyrs. Immediate protests expressed outrage and sought to memorialize the two men. In Mexico City the Mexican Confederation of Labor called for a one-hour cessation of work on the morning of August 24. Streetcars halted, buses were parked across the principal streets of the city, and traffic was paralyzed. In Sydney, Australia, ten thousand protesters demonstrated in the streets. In London’s Hyde Park, similar crowds gathered. In Paris, despite a downpour of rain, bands of demonstrators battled with police: Stones and bricks were thrown, store windows broken, and cars along the route of the march overturned. More than a hundred police were injured and some two hundred demonstrators arrested. Then the protests and demonstrations stopped, and the case assumed a new life as the subject of films, novels, plays, and poetry throughout the world. The curtain rose on the third act of this global history.[59]

Stories about the life and death of the two working-class heroes fed the demands of the world’s burgeoning throng of working-class moviegoers. Movies produced in Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and Russia dramatized the case. One handbill in Argentina advertised the film Sacco y Vanzetti as revealing “all the struggles, the ideals, and the deep sufferings of seven years of slow death, the most sensational, tragic, and heroic story witnessed in centuries.” It noted that “women should see this film”; the sufferings of Rosa Sacco “would bring tears to [the eyes of] all women of the world.” In Copenhagen sensationalist advertisements billed a film on Sacco and Vanzetti as a story of “a judicial murder ... A criminal Film in Six Great Acts.” The movies were shown in such far-flung places as Montevideo and Morocco, much to the consternation of American embassy officials, who protested the showings as a “gratuitous and premeditated effort to stir up hate against the United States.” Claiming that the films represented a direct attack on the judicial procedure of a friendly nation, embassy officials requested that they be withdrawn, at times successfully.[60] Other forms of working-class culture also provided ways to protest and remember the case. A tango—the dance created by the Argentine working class in the 1920s—was entitled “Sacco y Vanzetti.” Composed by J. M. LaCarte, it spoke of the “two Italians in a sad jail cell ... crying their pain and affliction.” Entrepreneurs with radical sympathies also used the two men’s fame to appeal to working-class consumers. In Argentina a Sacco and Vanzetti brand cigarette was sold. The American ambassador to Argentina was so concerned about their sale and that of other “articles of commerce” that carried the names of “two convicted criminals in the United States” that he protested to the Argentine Ministry of Foreign Affairs requesting their prohibition. Sympathizers of the two men in Argentina also sought, unsuccessfully, to transform public spaces into sites of collective remembrance. Proposals were made by city council members in Buenos Aires to change the name of the street Estados Unidos to Nicolas Sacco and that of Nueva York to Bartolomé Vanzetti.[61]

More commonly, the two men were remembered on the stage, in poems, in songs, and in novels with their story retold in different ways for different audiences at different times. The first wave of such art burst onto the scene in the wake of the men’s execution and continued into the 1930s. While much of this material was produced in the United States, it was often translated and published elsewhere—such as Eugene Lyons’s history of the case and the 1928 play by Maxwell Anderson and Harold Hickerson, Gods of the Lightning, which was produced in Berlin in 1930 and Madrid in 1931. Other plays were written abroad, for example, Pierre Yrondy’s French production, Sept ans d’agonie. Radical newspapers and journals that had kept up a parade of information when the men were alive now memorialized them in anniversary supplements and printed histories of the case. Even pulp material intended for working-class audiences retold the story from Madrid to Havana to Buenos Aires. The writings of Bartolomeo Vanzetti, particularly his autobiography, were translated into several languages. The writer Ba Jin, who had exchanged letters with Vanzetti when the Italian was in prison, translated the autobiography into Chinese. He was deeply touched by the case and referred to it in his first novel, Meiwang, published in 1929. Ba Jin referred to Vanzetti as his “mentor.” “I never met him, but I love him and he loves me.” This first wave of cultural production, as Ba Jin’s words attest—plays, novels, poetry, and art—heroized the two men and secured their place for posterity as working-class martyrs whose deaths symbolized injustice and sounded a call to social action.[62]

The second wave of cultural production arose in the 1960s, a time of heightened social conflict in many places. For those questioning their societies’ perceived failures to live up to democratic ideals, the case highlighted that failure in the past and linked a burgeoning social movement to a longer history of struggle. The men’s story stood in for a broader history of social injustice and called for a renewal of “international solidarity.” The social movements of the 1960s—from the student movement to feminism and the New Left—were international. Ideas, people, and organizations spilled across national borders to redress social injustice in their home countries and globally. Participants in those mobilizations looked to moments of such solidarity in the past for inspiration. Publishers not only reissued accounts of the case by, for example, Upton Sinclair and Eugene Lyons, but Italian, French, and German playwrights retold the story. Plays produced in one country were often translated and performed in another. In a play by Armand Gatti, produced in France in the early 1960s, the international presence of the case was taken as the central theme: The trial of the two men was reconstructed through the eyes of women and men in five urban settings—Boston, Lyons, Hamburg, Turin, and New Orleans. Sacco and Vanzetti came alive again not only in plays but also through music. Joan Baez’s “Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti,” written by Ennio Morricone, shared the title of Woody Guthrie’s earlier homage to the two men. It linked their martyrdom to “racial hatred” “and the simple fact” of being “poor.” It became known to an international audience through the release of Giuliano Montaldo’s film Sacco e Vanzetti in 1971. Songwriters abroad joined the chorus. One of France’s best-known singers, Georges Moustaki, translated Baez’s homage and released it as “La marche de Sacco et Vanzetti.” In Germany the political songwriter Franz Josef Degenhardt introduced a new generation to the two men with powerful lyrics in three languages that sought to inspire left mobilization by commemorating Sacco and Vanzetti’s legacy and martyrdom.[63]

Even today, Sacco and Vanzetti have not been forgotten. Their names label streets in towns and cities in France, Italy, and the former Soviet Union. Since 1988, the Museum of Modern Art in Frankfurt has had a Sacco and Vanzetti “reading room,” created by the Iranian-born artist Siah Armajani as a tribute to the men’s “dedication to the rights of working people and to the goal of universal education.” In Argentina in 1991, Sacco y Vanzetti, a play by Mauricio Kartun, premiered in the Metropolitan Theater in Buenos Aires. Versions of the play have since been performed in the Argentine interior, in Montevideo, and in Rome. New plays, from Louis Lippa’s Sacco and Vanzetti: A Vaudeville to Anton Coppola’s opera Sacco and Vanzetti, which premiered at the St. Petersburg, Florida, opera house in March 2001, retell the story. In these dramatizations, the details of the case have been lost as it has been transformed into a grand symbol of the struggle of the weak, the poor, and the working class for social and economic justice and of political minorities for tolerance.[64]

Given that in eighty years historians have failed to come to a consensus on the guilt or innocence of Sacco and Vanzetti, it might seem odd that they have achieved global status as working-class martyrs. After all, the twentieth century has witnessed its share of innocent women and men persecuted and executed by repressive states because they held unpopular political opinions. Yet, in the context of the historical moment and contingencies that brought the two Italians to prominence, their staying power makes sense. The Sacco and Vanzetti case coincided with the birth of the new era of mass communications that transformed the world into an ever more connected place. That made the two anarchists household names in many parts of the world. Moreover, the confrontation took place as the dynamics of global radicalism were being reworked, allowing the case to serve as a cause for different groups in their efforts to revive or build new radical movements. It also took place at a time when class relations were being altered in Europe and Latin America. As a result, it became a unifying cause that brought together workers and middle-class citizens who shared a concern over issues of political tolerance, discrimination, and social justice—in effect building an early version of the Popular Front. These factors contributed to unleashing the global passion of Sacco and Vanzetti.

But it was the location of the trial in the United States and the position of the United States as a world power that above all explain the case’s resonance. The United States government since World War I had declared itself a beacon light of freedom and democracy, a positive force for a better world. From the perspective of those outside the United States—both for those who embraced that promise and for those who found it barren—flagrant violation of justice in the United States was rightly an international concern. It was, as they saw it, not only their right but their duty as citizens in a world of deepening United States influence to be concerned with the corruption of American justice. While Sen. William Borah in 1927 indignantly declared foreign intervention “impudent,” such intervention was read differently by many in the United States and by the vast majority of those looking from the outside in. Despite the deaf ears of United States officials to the international outcry, its legitimacy was obvious to millions of citizens of the world: A country claiming global influence—partly based on universal values of democracy and freedom—is the rightful subject of international criticism when free institutions and democratic values appear to fail. In a world ever more shaped by the United States, that holds true as much today as it did in the 1920s.

Lisa McGirr is Dunwalke Associate Professor of American History in the Department of History at Harvard University.

All translations, unless otherwise noted, are by the author.

I would like to thank Thomas Bender, Stefano Luconi, Nelson Lichtenstein, Michael Topp, and the anonymous referees for the Journal of American History for their careful reading of the manuscript and valuable suggestions. I would also like to thank Gabriel Ferro for excellent research assistance and Di Yin Lu for Chinese-language translation.

[1] “Demonstration of Radical Elements,” American Consulate, Mexico, to Secretary of State, memo, May 2, 1927, file number 311.6521 Sa1 446, Records of the Department of State, rg 59 (National Archives, College Park, Md.); “Speeches delivered before Consulate by radical groups,” memo, May 2, 1927, ibid.

[2] I use the words “global” and “international” interchangeably. I use “transnational” for connections between people and movements of ideas across national boundaries. For the theoretical premises of a concept of “transnationalism,” see Linda G. Basch, Nina Glick Schiller, and Cristina Szanton Blanc, Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States (Amsterdam, 1994), 21−49, 225−66.