Georges Fontenis

The Revolutionary Message of the ‘Friends of Durruti’

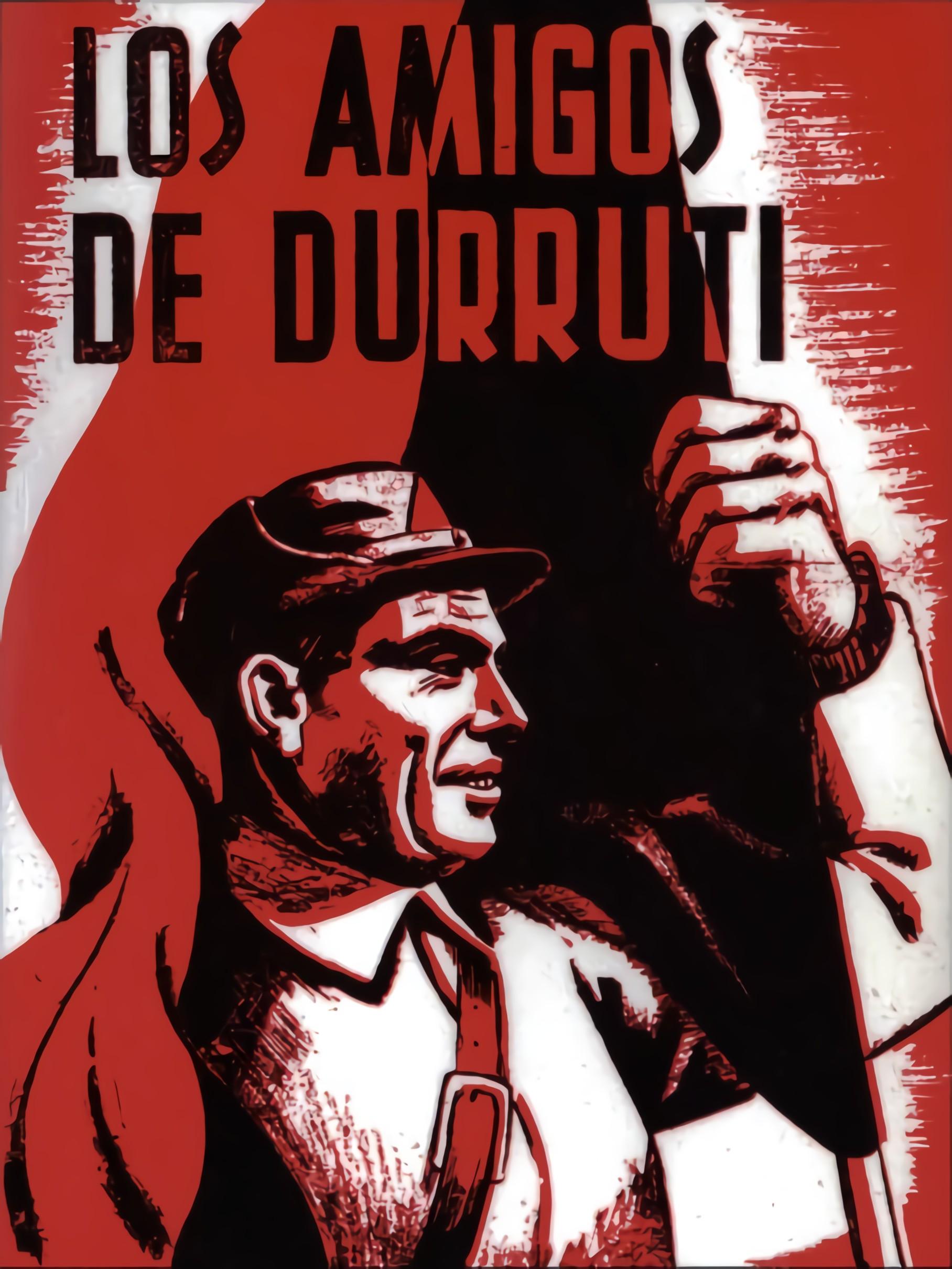

Alternative Libertaire pamphlet translated from French by Chekov Feeney

Note from the translator Chekov Feeney

Preface to the 1st Edition (1983) by Daniel Guerin

Introduction to the writings of the Friends of Durruti by George Fontenis

The Anti-Fascist Camp in the Spanish Revolution

The Bourgeois Republic and the Revolutionaries

The CNT Prepares for Revolution

The Government’s First Offensive

Towards Open Collaboration with the Government

The ‘Friends of Durruti’ and the ‘People’s Friend’

Who Were the Friends of Durruti?

Denunciation of Ministerialism

The Steps of the Counter-Revolution

The Petit-Bourgeois and the Revolution.

Revolutionary Theory and Programme

Foreword by Andrew Flood

The Spanish anarchist organization ‘The Friends of Durruti’ was formed by members of the CNT in 1937 in opposition to the collaboration of the CNT leadership in the government of Republican Spain. The first heavily censored issue of their paper ‘Friend of the People’ appeared just after the Maydays in Barcelona, sections of it are reproduced for the first time in English in this pamphlet. The Mayday defence of the revolution in Barcelona was crushed at the cost of 500 lives, including the disappearance, torture and murder of key anarchist organisers by the Stalinists. The Friends of Durruti outlined an alternative path for Spanish anarchists, one intended to not only protect but to expand the revolution and bring it to victory.

This is the English translation of a study of ‘The Friends of Durruti’ published in 1983 by the French libertarian communist George Fontenis. It traces the path and political weaknesses that led the CNT into collaboration at the cost of standing aside as the revolution was suppressed and the emergence of the Friends of Durruti in reaction to this. Its primary importance is that in reproducing large tracts from their newspaper it allows the Friends of Durruti to speak for themselves. This stands in stark contract to the approach of those who have tried to speak for them in order to conscript them to various ideologies today, some of which they would certainly have rejected out of hand.

The translator, Chekov Feeney, provided the following note when the translation was first published online in 2000. This reproduction of that translation was prepared to mark the 75th anniversary of the outbreak of the Spanish Revolution in 2011.

Andrew Flood

2011

Note from the translator Chekov Feeney

The introduction is not credited and the publishing details are a little bit difficult to discern since there are AL (Alternative Libertaire) stickers on top of the original publishing information. What I can say is that it is the second edition, published editions “L” and/or AGORA 2000, PO box 177, 75267 Paris Cedex 20 and/or Le Fil Du Temps.

There is a note on the inside cover that says that the present edition is part of the collective work of Alternative Libertaire.

No date is given for this edition.

The title in French is (as it appears on the cover) le message revolutionnaire des “Amis de Durruti” (Espagne 1937) Texte et traductions de Georges Fontenis Avant-Propos de Daniel Guerin.

Preface to the 1st Edition (1983) by Daniel Guerin

George Fontenis’ study seems useful to me, indeed I would go so far as to say it is valuable, not only as it teaches a better understanding of the Spanish Revolution of 1936–7 but it also provides a more extensive interpretation of the notion of libertarian communism itself. When using this phrase ‘libertarian communism’ it is certainly worthwhile to clearly distinguish it from two other versions which are endowed with the same name. To be specific; firstly the utopia, propagated by Kropotkin and his disciples, of a terrestrial paradise without money where, thanks to the abundance of resources, each and every person would be able to draw freely from the stockpile.

Secondly the infantile idyll of a jumble of ‘free communes’, at the heart of the Spanish CNT before 1936, which arose from the thinking of Isaac Puente. This soft dream left Spanish anarcho-syndicalism extremely ill-prepared for the harsh realities of revolution and civil war on the eve of Franco’s putsch. Fontenis, although he does highlight certain positive aspects of the congress of Saragossa of 1936, seems to me to err on the side of those who appear removed from reality.

In the first part of his study, the author traces with precision the degeneration, the successive capitulations of the anarchist leaders of the CNT-FAI. However, perhaps he does not penetrate to the heart of the problem with sufficient conviction. To be precise, was traditional anarchism, idealistic and prone to splits, not destined to fail as soon as it found itself confronted by an implacable social struggle, for which it was not in the least way prepared?

Because it was not mainly infidelity to principles, human weakness, inexperience or naivety among the leaders, which led them astray, but rather it was a congenital incapacity to evade the traps of the rulers (which they put up with since they weren’t able to write them off with a stroke of a pen). As a consequence they were destined to get bogged down in ministerialism, to take shelter under the treacherous wing of ‘antifascist’ bourgeois democracy and finally to let themselves be dragged along by the Stalinist counter-revolution.

On the other hand, they were damned well prepared for economic self-management of agriculture, and to a lesser extent, industry. These, together with libertarian collectivisation remain a model for future revolution and saved the honour of anarchism. One might express regret that Fontenis’ study is only able to skim the surface of this glorious episode of the Spanish revolution. He would surely be justified in retorting that it is no less absent from the writings which he analyses.

The merit of these texts lies elsewhere, in the political domain. They reveal an unjustifiably obscure aspect of the Iberian libertarian avant-garde, the brief rise of the ‘Friends of Durruti’, named in memory of the legendary Durruti, who fell on the front on the 20th of November 1936. They emerged from the lessons drawn, a little late, from the cruel defeat of May 1937 in Barcelona. Just as in France Babouvism was the delayed fruit of the severe repressions of germinal and prairial 1795, the lucidity of these libertarian communists was inspired by the tragedy of May in Catalonia.

Throughout the few editions of their short-lived paper, ‘The friend of the people’ which Fontenis has passionately scrutinised and translated, we see these militants refusing, as was advocated by the reformist anarchists as much as by the Stalinists, to wait until the war has been won to carry out the revolution and affirming that one couldn’t be dissociated from the other. They proclaim that it is possible to battle against the fascist enemy without in the least renouncing libertarian ideals. They denounce the asphyxiation engendered by the machinery of state. And finally they affirm that without a revolutionary theory, revolutions cannot come from below, and that the revolution of 19 July 1936 failed for want of a program derived from such a theory.

Georges Fontenis, in his efforts to realise such a libertarian communist program, wrote this in 1954 in France and updated it in July 1971 at Marseille at the constitutive congress of the Organisation Communiste Libertaire (OCL), which I took part in. I will finish by specifying that, today, I find myself at his sides in the UTCL (Union des Traivailleurs Communistes Liberataires), which sets itself in the tradition bequeathed by the First International, that is to say anti-authoritarian.

Introduction to the writings of the Friends of Durruti by George Fontenis

Barcelona, May 1937. The first issue of ‘The People’s Friend’, the organ of the Friends of Durruti, appeared. The police repression of the Republican state had just crashed against the fighters of the barricades who had responded to the Stalinist provocations by retaking the road of revolution. But while the combatants of the revolution were taking the fight to the forces of repression of the Catalan Generalitat and of the central state, the anarchist ‘leaders’ of the CNT-FAI, having become ministers of the bourgeois government, asked the victors of the barricades to lay down their arms, to have faith in their ‘leaders’ to settle the conflict and to reunite the anti-Franco forces.

The result wasn’t long in coming: thousands of the barricade fighters found themselves in prison, and the censorship of the press became more brutal than ever. The first issue of ‘Friend of the People’ was ferociously censored. But at last it appeared and went on to try to be the rallying point for all those who, while struggling against Franco, didn’t want to forget the tasks of the revolution. Precisely those tasks which gave meaning to the war against the military and their allies.

The ‘Friends of Durruti’, and more generally the Spanish libertarian workers, were to fail. Why? And what really was their battle? After almost half a century since these events, nothing of substance has yet appeared in response to these questions. The leaders of the ‘official’ anarchist movement, still preoccupied with hiding the weaknesses and the inconsistencies, blurring the responsibility, avoiding the fundamental theoretical problems, avoid discussion or are satisfied with a few reluctant confessions and regrets. But we still await a profound auto-criticism, a rigorous analysis of the events. Everything has been done to extinguish the most radical critiques, in particular those of the ‘Friends of Durruti’, and to try to write them out of history.

However they, the ‘Friends of Durruti’, have supplied more than an outline of such a vigorous analysis and they did it in the heart of the battle itself.

This is why it seems to us to be indispensable to publish their principal writings, still unpublished in France. To contribute to the debate which we wish to clarify, we add here a brief study of the evolution of the libertarian movement and of the Spanish revolution and also, necessarily, the commentaries that the texts and the facts inspire in the comrades who pursue the struggle for libertarian communism today.

Having said that, our work is not a history of the Spanish revolution which, in our eyes, remains to be written. We have furthermore deliberately left aside the immense episode of economic and social achievements, collectivisations and socialisations, except insofar as they impinge upon our study. These are well covered by the works of Gaston Leval and Frank Mintz, cited in the bibliography. We have only attempted to examine, from a revolutionary point of view, the period from spring to summer 1937. A period which we believe was decisive.

The Anti-Fascist Camp in the Spanish Revolution

It is absolutely necessary — the Friends of Durruti tried to point out — to find a path which allows revolutionaries, without compromising and without falling into an unprincipled anti-fascist front, to have a practical strategy of struggle which unifies the proletarian forces against the violent blows of the reaction, militarism and fascism. One understands why the Friends of Durruti, should have given such importance to the so-called choice ‘war or revolution’

But, before addressing the events and their analysis, we must lay out, as briefly as possible, the composition of the forces present on the “antifascist” side, in order to assist the journey of the non-expert reader across what one author has called the “Spanish Labyrinth”. The bibliography which we give will allow one to find fuller information.

Spain and Catalonia

The pressure of regional autonomies in Spain, whose unity was imposed by the central government, goes back far. It carries on today, on the institutional level (There exists in various regions, administrations which enjoy limited autonomy), or as subversive action (which is the case in the Basque country). In the 1930’s it barely existed outside two regions which were otherwise the most economically developed, Catalonia and the Basque country. The Republic had granted them their own institutions. In Catalonia, a region which was to be in the forefront of the revolution, there was a regional power: the government of the Generalidad of Catalonia, a regional parliament, and forces of public order: the guards of the Generalidad (Mozos de escuadra). The parties and organisations often had a singular composition here, as we shall see.

The Catalan Parties

In Catalonia there existed organisations without any institutional or historic links with the parties and groups which were found throughout the rest of Spain. We mention the most important.

-

The “Catalan Left” (La Esquarra Catalana) controlled the Generalidad. It was a party of workers, intellectuals, but mostly elements of the “left-wing” petite Bourgeois. It was the party of Companys, the president of the Generalidad.

-

The union of rabassaires (sharecroppers, agricultural small holders) was of a similar leaning.

-

The party of the Catalan state (l’Estat Catala) was openly separatist, its nationalism leaned towards fascism.

The Federalist Republicans

The federalist spirit appeared in Spain during the 19th century, as a strong current within Republicanism. A certain number of these Republicans saw themselves as being very close to the federalist ideas of the anti-authoritarian wing of the 1st International. The federalist Republicans recruited mainly from the liberal petite bourgeoisie and in certain peasant circles.

In 1936, in the Madrid parliament (the Cortes), there was an astonishing parliamentary extreme left. It was made up of federalist republicans. There was among them, notably, lawyers who defended anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist activists in court. These liberals didn’t at all want to overturn the basis of bourgeois society but they had radical rhetoric, reasonably close to the declarations of the revolutionaries. The CNT treated them delicately and even supported them, despite it being anti-parliament.

The Left and the Extreme Left

The socialist party (socialist workers party of Spain) was a reformist party, composed mainly of petite bourgeois intellectuals and bureaucrats. However, it contained a working class base grouped in a Union organisation, the General Union of Workers (UGT) in so far as the paths of the party and the unions were interlinked. A good example: the socialist leader Largo Caballero, who was to be, for a long time, a pure reformist and repressive minister — was secretary general of the UGT. The leaders of the UGT openly fought the syndicalists of the CNT, however there was, among the rank and file, in many circumstances, a desire for unity of the working class.

The communists were divided and few, their Stalinism was excessive. Their influence grew quickly during the revolution. We shall see why. In Catalonia, the Stalinist party took the name of PSUC, united socialist party of Catalonia, born from the fusion of the small communist party and a socialist Catalan party.

The Trotskyists made up only a few groups whose activity was primarily in the field of theory. Their best-known militant Andreas Nin, joined the POUM. It is incorrect to see this ‘Workers Party of Marxist Unity’ as being Trotskyist. It was, from 1935 on, the guise of the block of communists, essentially Catalan workers and peasants, who had broken with Moscow. It was a party which exercised a certain influence, notably in Barcelona, but it was ceaselessly buffeted between support for the Catalan nationalists and internationalism, between electoralism and the fact that a certain number of its members were in the CNT, between the denunciations of the rulers in Moscow and its proclaimed admiration for Stalin’s regime. In Trotskyist jargon, it was a “Centrist” workers party.

The Libertarian Movement

Let’s pass on now to the National Confederation of labour. Without going into the details of its history we have to further elaborate on this CNT of which the “Friends of Durruti” were members. It was founded in 1910, by the workers and libertarian groups which had persisted as inheritors of the Spanish federation of the 1st international. It was inspired by French revolutionary syndicalism, thus at its inception it adopted the form of organisation and struggle of the trade union, but it defined its final objective as being anarchist communism. It saw the union as the fundamental structure towards the realisation of this goal. It was a mass anarcho-syndicalist organisation whose membership came close to 1 million in 1936. Its history is extremely complex, having passed through numerous conflicts. It contained two fundamental currents which were often opposed. One was purely anarcho-syndicalist and considered that the CNT was the only organisation needed and regarded the existence of organised anarchist groups, outside the CNT, as superfluous or even troubling.

On the other side was the current, inspired by the activists, which saw themselves as being primarily revolutionary anarchists and only then members of a syndicalist confederation where they had the mission of combating every reformist tendency. The conflict escalated when, in 1927, the anarchist groups, until then weakly tied together in a very loose federation, formed the famous FAI (Federation of Iberian anarchists) along with some Portuguese groups. We now arrive at the problem of relations between the mass organisation and the organisation of the avant-garde. Even though the relations between the FAI and the CNT weren’t relations of straightforward domination, you could find militant anarchists who were opposed to the FAI and who condemned “the FAI dictatorship”.

In fact while a certain number of the CNT officers were members of the FAI, properly speaking this didn’t amount to a dictatorship, rather a dominant ideological influence. The conflict reached a head in 1931, at the CNT congress held in Madrid. It set the activists who proposed a realistic analysis and very considered approach against those activists who wanted to launch the revolutionary uprisings immediately. The former drew up a manifesto, receiving 30 signatures (they were called the “Trente” and their tendency was called “Trentisme”). In the manifesto they denounced the superficial analysis, the simplistic and catastrophic conception of revolution, the cult of violence for its own sake, which seemed to them to be characteristic of the militants of the FAI.[1]

Certainly, it was far from being true that all the members of the FAI were hooligans. However, it is true that adventurist revolutionary attempts had been attempted and were to be attempted in the period that followed, at the instigation, or with the support of some groups of the FAI. These attempts were doomed to failure and resulted in fierce repression. To cut a long story short, the “trentistes” who called themselves prudent, but not any less revolutionary for this, counted in their number some activists who were incontestably inclined towards reformism. One of their leaders, Angel Pestana went on to found the “Syndicalist party” and would become a deputy in the Cortes.

The activists and the unions which rallied to the manifesto of the thirty were expelled from the Confederation and constituted the “unions of opposition”. Their influence in some regions was far from negligible. So much so that they were re-admitted into the CNT five years later at the congress of Zaragozza.

We will soon see ministers whose origin was “trentiste” and even militants of the FAI or intransigents who had battled against “Trentism”, like Garcia Oliver and Federical Montseny, in the Madrid central government and that of the Generalidad of Catalonia, in Barcelona. Also in September 1937, Pestana joined the CNT.[2]

If we want to give a brief but relatively complete overview of the currents which were present in the Spanish libertarian movement, we can distinguish:

-

A small revisionist “fringe” which ended up in the syndicalist party alongside Pestana.

-

A “trentist” current, which saw itself as revolutionary but realistic which included a certain Juan Peiro. It had fought for the creation of Federations of industries in the CNT and had denounced the adventurist practices of some groups of the FAI.

-

A traditionalist component consisting of many union officers who didn’t always see the utility of a specific organisation bringing together anarchist groups (sometimes they even combated its existence). These militants considered themselves anarchist but for them anarchist groups should simply be centres of thought and general propaganda. This point of view is currently very popular among anarcho-syndicalists.[3]

Consequently, it was far from being the case that the FAI included all the anarchists for whom the trade-union wasn’t the answer to all the problems. Furthermore one must distinguish the working class FAI-ists, primarily anarcho-syndicalists like Garcia Oliver and Durruti, from the anarchists from intellectual backgrounds like Federica Montseny.

The Libertarian Youth who defended the purity of the “acrate”[4] ideal and played a large part in the cultural and educational fields especially in Catalonia. On this point it should be stated that the Spanish libertarian movement in its entirety was very concerned with spreading literacy and education (from which came the creation of numerous modern schools, inspired by the teachings of Fracisco Ferrer, and the proliferation of “atheneums” a kind of popular university which were very active).

The “Friends of Durruti”, all members of the CNT, most also members of the FAI, formed a specific current from 1937.

From July 1936 on the links between the CNT and the FAI became so close that the two emblems appeared together more often than not (People spoke of the “CNT-FAI”). There was even a “libertarian movement” consisting of the three branches: CNT, FAI, FIJL (Iberian federation of libertarian youth). But in the midst of the difficulties of the war we will see an opposition emerge between the direction of the CNT, sacrificing all to the ideology of “resistance to the extreme” and submitting to the instructions of the Negrin government, and the FAI committee for the peninsula which made a late effort to save its honour by denouncing the advance of the counter-revolution.

To finish with this rapid overview, it would be useful to note that the FAI, founded in the beginning by practically underground “affinity groups”, was at all stages on the margins of the law and was numerically confined with about 30,000 members in July 1936. From then on it was active in public, and in July 1937 it transformed itself into a Federation of local and district groups, considerably more open to membership than the affinity groups, although the decision-making powers of the committees increased. Thus the specific organisation, “la specifica” as the Spaniards said, became a party in the modern style, aiming to become a “specific mass organisation”. Without doubt we can consider that the affinity groups were no longer the same with the advent of the period which began in July 1936, but on the other hand how could they not see the poverty and the confusion of their theoretic base which consisted of a declaration of principles of a mere few lines?[5]

The Bourgeois Republic and the Revolutionaries

The Republic of 14 April 1931

The bourgeois republic which came to power in 1931, replacing the monarchy was very conservative. The support of the socialists didn’t affect this character. The socialist minister of labour, Largo Caballero, was even to be seen participating in the repression of the strikes and insurrections which rose in the face of the incapacity of the new regime to produce even the most basic of changes. The toll of the first two years of the republican power was harsh: 400 dead, 3,000 wounded, 9,000 arrested, 160 deported, 160 seizures of workers newspapers.... and 4 seizures of right-wing newspapers.[6] We can understand why the parliamentary elections of 1933 ended with the defeat of the left: the workers didn’t vote. The socialists went from having 116 deputies in 1931 to having 60.

The most important working class force, the CNT, had declared an “electoral strike” in order to bring about the social revolution. It effectively produced a revolutionary movement on the 8th of December 1933. In various regions, in many villages and towns, the masses declared libertarian communism. The repression was brutal. The overtly reactionary government went on to face a powerful insurrection, that of Asturias, in October 1934 where socialists, communists and anarchists fought side by side. The quashing of the insurrection was a veritable bloodbath, accompanied by the severe use of torture and the imprisonment of 30,000 workers, of whom a significant proportion were members of the CNT.

The Popular Front

It is understandable that the abstentionist campaign was weaker for the elections of 1936; in fact the CNT allowed its members to cast their votes for the parties of the left, combined under the banner of the “popular front”, with the idea that a victory of the left would empty the prisons. It was effective; the right was beaten and the political prisoners were freed....

The agitation within the army was growing. It was already evident before the elections, to such an extent that two days before the poll, the national committee of the CNT had issued a manifesto calling for mobilisation against a threatened military coup d’état: “The proletariat on war footing, against the fascist and monarchist conspiracy!” What was the new popular front government to do? It gambled on passivity, and went as far as to deny all danger, it even praised the loyalty of the military chiefs.

The CNT Prepares for Revolution

The CNT met on the 1st of May 1936, at the congress of Zaragozza. It tried, despite speeches which were not immune from naivety, to define various aspects of its programme, libertarian communism. It set the conditions for the unavoidable alliance with the UGT in potentially revolutionary circumstances. It specified its position, constructive and critical at the same time, towards the projects of land reform. Under the title “defence of the revolution” the congress addressed the problem of revolutionary power and armed struggle.

Certainly, it was then impossible to predict exactly how the potential revolution would come to pass, however the foundations of a politics which was truly a break with the capitalist and statist order were set out: the seizure of economic power on every level, the role of Spain in terms of the international revolution, the abolition of the permanent army, the need to arm the people and to keep the arms under the control of the communes, the role of the “Confederal defence forces” and the efficient organisation of the military forces on the national scale, the crucial importance of propaganda with regard to the proletariat of other countries.

Let us not forget the general spirit which presided during these debates: in the resolution which concerned the alliance with the UGT, it was specified that “every kind of collaboration, political or parliamentary” with the bourgeois regime must be rejected.

It is worthwhile to recall all this before looking at the attitude of the CNT two months later, as it was in July that the military uprising occurred.

July 1936

In effect events unrolled very quickly. From the start of the parliament the deputies of the right in the Cortes issued declarations of civil war. On the 11th of July, the Phalange[7] seized the radio transmitter in Valencia. The president of the council was warned of the potential uprising of the generals but he refused to take those measures that he could. On the 17th of July, the army took power in Morocco; the massacre of workers and of left-wing personalities started... and the Madrid government declared that it was in control of the situation. Seville fell into the hands of the military. Finally the government of Casares Quiroga ceased issuing reassuring declarations but only so that it could pass the baton to a government of reconciliation, presided over by Martinez Barrio, with the ministry of war offered to General Mola who refused it and declared himself in open rebellion.

On the morning of July 19th, the paper of the CNT, Solidaridad Obrera, came out, severely censured by the republican government, but the appeal of the Catalan regional committee, a call to arms and for a general strike, escaped the censors.

The same regional committee and the local federation of Barcelona Unions demanded that the Generalidad of Catalonia and the civil governor should distribute arms to the popular forces; in vain. However, the militants of the CNT seized the arms stored in the ships in the port. The authorities ordered the forces of public order to take them back but only a tiny amount were recovered. In Madrid, the national committee of the CNT called for a revolutionary general strike over the radio and requested the activists to guard the union offices with arms.

On the 19th and 20th of July the Barcelona barracks were taken by the popular forces and the CNT and FAI activists, who constituted the principal element of these forces, were the uncontested masters of the social and economic life of Catalonia. In Madrid, from the 20th on, the comrades of the CNT, aided by groups of assault guards and by the Socialist youth, made themselves masters of the situation. Elsewhere the struggle was confused, thus in Valencia, due to the procrastination of the government it took 15 days for the military to be defeated.

Wherever it could, the Madrid government made the situation worse: its civil governors and the delegate juntas which it created hurried to end the strikes, to suppress the peoples’ executive committees which had risen. Thus it allowed the enemy time to rally, to reinforce its front at Teruel, to consolidate at Zaragozza and in Asturias, to become master of Andalucia. However on the 19th of July, the military uprising could be considered to have failed on the most rich, populous and developed two thirds of the territory.

The Masses and the Leaders

It was Barcelona which was going to arbitrate the future of a revolution for which the military uprising was the trigger. What were the CNT and the FAI going to make of the immense power which they had just acquired?

During an initial meeting, Companys, president of the Catalan Generalidad, gave a carte blanche to the representatives of the leading bodies of the CNT. What else could he do since his government had lost all credibility? In fact he was to manoeuvre: he proposed the creation of a committee of antifascist militias but published a decree which tried to transform the militias into a police force under the command of the Generalitat.

The representatives of the CNT forced the recognition of a committee of militias made up of delegates from various organisations, but the CNT was only to have an equal representation as the UGT, which was in the minority in Catalonia. It also gave a place to the bourgeois Catalan organisations. Without doubt it was necessary to take forces outside the CNT into account. But in what manner were they to be taken into account? In effect this was to put the government of the Generalitat back into the saddle by giving numerical strength to the conservative forces.

This political line was ratified by the representatives at the regional plenum of local and cantonal organisations of the CNT and FAI on the 23rd of July.

A stupefying false dilemma obscured the debate from the start: “either libertarian communism which is equivalent to anarchist dictatorship or democracy, that is to say collaboration”. According to José Peirats (who doesn’t cite his sources) Garcia Oliver was its architect. Oliver claims, on the contrary, that he was one of the only militants who took the side of the revolution (everything for everyone) and he accuses Federica Montseny and Santillan of having carried the majority at the plenum against the dangers of ‘anarchist dictatorship’. Nevertheless both G. Oliver and F. Monstseny would soon find themselves collaborating within the government.

How do we explain that the vast majority of the CNT and the FAI rallied, it is true more in resignation than with enthusiasm, to the side of collaboration in the midst of state bodies? We shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that the Spanish anarchist movement, while it was predominantly working class, was not immune from some of the weaknesses of the international anarchist movement of the period. Bourgeois idealism, ill-defined humanism, the substitution of hollow philosophical talks for solid political reflection, individualism and dilettantism were common especially among the intellectuals who were sometimes closer to radical liberalism than to revolutionary syndicalism.

It suffices to read a few of their magazines and pamphlets to be convinced of this. The Congress of Zaragozza was, to a certain extent, a reflection of this situation. It was certainly forced to give a hearing to libertarian communism, but the problem of political power was never clearly posed. Thus there were taboo subjects in the libertarian organisations and the idea of power of the masses as opposed to the state power, a vital, fundamental question, was still surrounded by an embarrassed silence.

Too often the phrase “acrate” and the affirmation of “anarchist purity” took the place of deep consideration. Therefore it’s not as surprising as one would imagine, that the mass of activists were caught napping and accepted the crude assimilation of working class power in the streets and factories, in place of a state or party power, or ‘anarchist dictatorship’. We will come back to this.

For a while, the collaboration in state power wasn’t very evident. Without doubt to save face and to quieten the worries of a certain number of activists, the committee of militias didn’t really take on the appearance of a government and remained autonomous to a certain extent, although it had been officially created by a decree of the government of the Generalitat and was merely a congregation of the leaders of the various organisations rather than a body emanating from rank and file committees.

But what is remarkable is the breach which, little by little, was to become established between the politics of the rank and file organisations and those of the committees at the top. Thus the union sections at the bottom took the measures of seizing businesses, workers control and even collectivisation. At the same time as these workers’ demands were being carried out, the committees were publishing communiqués insisting on the necessity of returning to work and increasing production while refraining from giving any revolutionary advice with regard to the running of large companies. 2 examples: the communiqué of the Barcelona local Federation of Unions on July 28th and the manifesto of the peninsular committee of the FAI on the 26th which were a collection of romantic, even delirious, declarations extolling the heroism of the workers, appealing for a “new era”, but without even the least mention of political power or socialisation.

The constructive revolutionary drive (with the de facto alliance of the CNT and UGT) rose from the people, from the unions and from their activists, while the committees followed a course of moderation.[8] These committees of “officials” were also to find themselves confronted with criticism which was aimed at the organisations which they represented. The criticisms were sometimes well-founded: there were some abusive or unwarranted seizures of goods, arbitrary arrests by groups of individuals without mandate and even summary executions.

We will go on to see how an attempt was made to sort out the problem of what one might call “revolutionary security”, but one thing that we can see immediately is that the committees at the top were going to fall into the trap which the central government and that of Catalonia were setting: blackmail by foreign goods and by crude terrorism were used, even by the committee of militias and the higher ranks of the organisations.

Certainly it was necessary to guard against any provocations and it is true that war ships of foreign powers had arrived in the port of Barcelona. The Catalan regional committee went so far as to give a list of 87 English firms which were to be respected at all costs. But the republican state shamelessly exploited a few isolated acts of excess and the threat of foreign squadrons to move the situation in the direction of normalisation under governmental authority. However, the governments of Madrid and Barcelona weren’t going to achieve their aim without problems.

In effect, beside the committee of militias which kept a revolutionary appearance, “popular patrols”, 700 men divided into 11 units, were created to take care of revolutionary security. On this occasion the CNT respected the balance of forces between the organisations.

The government of the Generalidad went along with it but it knew that this was an embryonic armed popular force and it would decree the dissolution of the patrols as soon as it was able to. For their part, the rank and file organisations pursued the work of socialisation and a Council of the Catalan economy was created by a decree on August 13th.

The Government’s First Offensive

At the beginning of August, the central government decreed the mobilisation of classes 33, 34 and 35. In Barcelona, the youth who were in these classes came out into the streets and refused to go to barracks. They held demonstrations crying “down with the army, long live the popular militias”. A number of these men were already members of the militias and were preparing themselves to leave for the front.

This time the regional committee of the CNT, the groups of the FAI and the newspaper Solaridad Obrera were on the side of those who refused militarisation. In this a reasonable reaction of the bottom against the plans emanating from governmental spheres can be observed and this was a massive popular reaction.

However, a compromise solution was to prevail under the aegis of the committee of militias and the council of defence: the youth went to barracks, but under the authority of the council of militias. The CNT and the FAI approved. It seemed that the most important thing had been conserved despite the concessions. While the career soldiers of various levels would be utilised in the technical field, the command would be assumed by councils of worker-soldiers, composed of elected soldiers and delegates from the organisations and parties.

But lets not forget that a ‘council of defence’ had just been created, at the heart of the government of the Generalitat, which had military authority over Catalonia. We will describe what this council of defence amounted to, but we should note that the initial buzz of opposition arising from the mobilised youth had tremendous energy: during an immense rally which was held in Barcelona on the 10th of August, the various orators of the CNT and FAI reaffirmed the importance that the people should not be disarmed under any pretext.

The general impression which emerges from this first period is an impression of ambiguity. The revolutionary values seemed to have been defended intransigently while at the same time concrete measures had been taken which went towards the abandonment of the radical line of social and political transformation. Here is another example of this. At the same time as the CNT and the FAI were refusing popular disarmament, they were creating with their partners a committee of accord which gave a great position to the UGT (which was only beginning to develop in Catalonia) and to the PSUC which declared itself to be “the party of revolutionary order, in the sense of respect for private property” and which was to drain the petite-bourgeois forces in the course of becoming a significant party.

Incontestably the creation of a committee of accord illustrates the politics of the leaders and is itself already a sign of an abandonment of real revolutionary politics. Having said that, in the context of the chosen direction, it is difficult to understand how the CNT and FAI accepted only having as many representatives on the committee of accord as did the UGT and the PSUC. This would come to weigh heavily in the course of the months to come.

Towards Open Collaboration with the Government

In Madrid, at the start of September, the government of Giral was replaced by the government of Largo Caballero who bemoaned the non-participation of the CNT. Two months later, on the 30th of October, Largo Caballero revealed, in an interview with the Daily Express, reproduced in all the papers, the desire of the CNT to share the responsibilities of government.

Meanwhile, on the 3rd of September, issue 41 of the CNT-FAI information bulletin had published a violently anti-statist article, but in mid September the national plenum of the regional organisations proclaimed the necessity of participation in “a national body equipped to assume functions of leadership” this body being a “national council of defence” composed of 5 delegates of the CNT, 5 from the UGT and 4 “republicans”, under the presidency of Largo Caballero.

Certainly, the replacement of the ancient institutions by regional councils of defence, in a way that was called federalist was declared, but everything, including the representation of the organisations in the councils, was decided by the leaders of these organisations, and did not rise out of popular assemblies and their delegates. It was a real party power which was put in place. Public power was going to be wielded by Largo Caballero and his ministers who were modestly called “councillors”.

In fact, the leaders of the CNT wished to join the government but had to save face and quieten the worries of their militants found it difficult to accept the open abandonment of their sworn principles.

On the 30th of September, a meeting of the national plenum of regional organisations of the CNT ratified participation, or rather according to its own wording, acceded to the insistent demand for the creation of a national council of defence.

In between time, on the 27th of September, the entrance of the CNT representatives into the government of the Generalidad, taking the title “council of defence” was announced, causing the dissolution of the committee of militias. Thus the situation of dual power had passed. The struggle against “uncontrollables” was to get more intense, and the necessity of strong discipline was to be reaffirmed. Durruti’s ambiguous phrase “we renounce all except victory” was used as cover for the operation, turning it into a warning against the counter-revolution, while Durruti was at the same time declaring to the Madrid press: “We, on the other hand, carry on the war and the revolution at the same time”.

How had the CNT and FAI been able to come to this? How were their leading committees able to get a mandate for such a fundamental change? Had the problems posed by the war and by the revolution really been truly addressed?

The documents of the epoch are silent. Nothing was treated in-depth; analysis had been replaced by speeches and declarations.

If in the international anarchist movement, discussion was alive, even heated,[9] apparently in Spain there was resignation.

Birth of an Opposition

In reality the situation was more complex than it appeared. One must take account of two important objective factors: on one hand many militants were at the front, they were at war and political problems were not at the top of their lists since they were fighting in particularly difficult conditions and with armaments which were often worse than deficient.

On the other hand many of the comrades in the rear were consciously advancing their affairs: the socialisations and collectivisations were going full steam ahead. The popular militias and the popular patrols appeared at least partially like the embryo of a real popular, anti-bourgeois power. Both groups were to be surprised by the evolution of events; the ever harsher retaking of governmental power, the elimination of popular bodies or attempts at establishing dual power.

Nevertheless the forces opposed to the politics of the officer corp and struggles for the maintenance of the base of a workers power, could be observed. In the militias at the front resistance to militarisation remained alive and the advances of socialisation and collectivisation were to be maintained despite the decisions of the government.

And then, on the purely political front, resistance nevertheless showed itself. It was often shouted down, hidden by the speeches of the leaders, it was sometimes alive and clear in meetings, especially visible in the press: Ruta, the organ of the Catalan libertarian youth, which was to be a paper of opposition right up to the end of the war, the review Acracia from Lérida, the daily Nosotros from Valencia supported by the “iron column”.

A weakness which was not to be surmounted until the spring of 1937 by the Friends of Durruti was that the opposition remained on the level of “acrate” purism, rather than on the level of the necessary analysis of the underlying problems.

Another weakness was the dispersion, the lack of cohesion, of co-ordination. The opposition wasn’t made up of a tendency which would struggle to be able to express themselves in the Confederate press. And this isolation was such that most militants, especially those who were at the front, didn’t even know that there was an opposition.

What’s more the opposition was trapped by the blackmail for antifascist unity, by the necessity to disguise disagreements in the face of the enemy.

The committees at the top didn’t hold back from using underhand manoeuvres like the speedy convocation of a plenum for which the mass assemblies wouldn’t have time to prepare, or incomplete agendas which allowed them to propose important points, unannounced, at the last moment.[10] Finally the cult of the leader, the charismatic power of the decision maker was at play in the libertarian organisations, like in every grouping.

To sum up, under the cover of the magic phrases, federalism and autonomy, the leaders hung on to power within the CNT and the FAI. We would have to wait until the government and the forces which supported it went violently on the offensive against the revolutionary sectors to see at last the rising of an opposition which attempted to address fundamental problems, “Los Amigos de Durruti”.

Up until then reasonable reactions were certainly seen but they were improvised and lacked political content. As in mid October ’36 the CNT-FAI column, “the iron column”, was to leave the Teruel front for a brief incursion in the rear. It was intended to denounce parasitism and the forces of repression, to demand the disarmament and dissolution of the civil guard, the sending of the armed troops in the service of the state to the front, the destruction of institutional files and archives and the seizure of funds and precious metals for the purchase of arms, etc. That “cleansing” incursion in the rear saw much blood spilled during the battles with the forces of repression.

The Iron Column published a manifesto explaining its concerns that the combatants should not be betrayed in the rear and they expressed their political choice clearly: “We fight to make the social revolution a reality”. Whatever may be one’s view on the adventurist or inconsequential aspect of this affair, one can only be struck by the feeling of the militia members that they should not be toys of the institutions of government and bourgeois parties, to be “refashioned” by the high politics of the rulers, the will of these men to fight, on the condition that they do it not for any republic whatsoever but for the revolution. We will soon see more reactions of this type.

The Repression Increases

It is precisely from the moment that the CNT-FAI participated in the government, that the repression was given free reign. It is certain that the participation was experienced as a setback by the militants, including those who supported it, and as a sign of weakness by their adversaries, extremely happy to ensnare the principal revolutionary force in the web of laws and decrees, and within governmental “solidarity”.

The central government left the threatened city of Madrid and retreated to Valencia. Madrid was then governed by a delegate junta of defence, of which the president, General Miaja, had as a first duty to replace the checkpoints and watch guards of the militias with security units and assault guards. Clashes occurred, CNT activists were found assassinated.

The repression also took an insidious track. The bank of Spain possessed a vast treasure of gold as well as large cash deposits in England and in the bank of France. The policy of non-intervention allowed Great Britain and France to refuse the use of these deposits but Stalin’s Russia was to receive the Spanish gold in exchange for arms and supplies.

The Russian arms only reached the sectors controlled by the communist party. The organ of this party, Mundo Obrero, pretended to be outraged by the inactivity of the Aragon front, which was mainly held by confederal divisions which didn’t receive arms, while the well-armed Stalinist units watched in the rear. Thus, little by little, a campaign of slander was set in motion, of which the CNT was not the only victim.

The POUM was the first target. The conflict between the POUM and the PSUC precipitated a crisis of government in Catalonia. A new government was installed, hypocritically composed of “social categories” and not of parties. Thus the representatives of the unions (CNT and UGT), of the Catalan left representing the petite bourgeoisie and the rabassaires (small peasants) were to be found in it, while the POUM was excluded. This didn’t shame the CNT which described the new government as apolitical! During this period the Stalinists had organised demonstrations against the lack of vitals until the arrival of Russian ships which brought the “gift of the Russian workers” to the proletariat of Barcelona, paid for by Spanish gold.[11]

The number of incidents was to increase: assassinated comrades, suspended newspapers, and detentions in the special prisons of the Stalinist agents where prisoners were tortured. The Cheka was moving in... Meanwhile on the 21st of January 1937 the committee of accord, set up on the 11th of August (see above), appealed once again for fraternity, with the signature of the CNT, FAI, UGT and PSUC.

Otherwise, with much reticence in the confederal columns, militarisation of the militias went ahead. The higher committees of the CNT went to the front to convince the militia members that this militarisation, which tended towards the revival of the old military reasoning, was well-founded. Some militia members left the columns but in the end, even the Iron Column accepted the new regulations.

The Stalinist provocations went on and a crisis was to be provoked in Barcelona by a decree of the 4th of March 1937 from the councillor of public order ordering the disbandment of the popular patrols and of various armed bodies; the disarmament of the popular forces for the benefit of the state force.

The confederal and anarchist activists arose against their representatives in the Catalan government. The federation of anarchist groups of Barcelona, the regional committee of the CNT, the workers and soldiers’ councils, demanded the annulation of the decree.

Companys, the president of the Generalidad, tried many legal formulas to resolve the crisis. A new government was formed on the 26th of April with 4 representatives of the CNT, but nothing was resolved.

May 1937

At the end of April and the start of May elements of the police disarmed some militants of the CNT and arrested them. On the 2nd of May, at 3 in the afternoon, large contingents of the state forces, under the command of the general commissioner of public order, launched a surprise attack on the telephone exchange. They could only get as far as the ground floor and the confederal militants in the working class areas were alerted.

Against the state forces (assault guards, national republican guard — ex. civil guard, security service, guard of the Generalitat), the PSUC and the Catalan separatists, were ranged the popular forces CNT-FAI, libertarian youth, POUM, popular patrols, benefiting from the technical assistance of the confederal committees of defence. The barricades were raised and the battle was at least as fierce as that of July 19th 1936 the mastery of the town. was at stake.

The confederal ministers of the Generalitat hoped to obtain the annulation of the orders which had been given to the state forces and the sacking of their colleagues who had abused their positions. But the other parties didn’t want to give way. The attitude of president Companys was equivocal and he opposed any sanctions against the perpetrators.

A general strike was launched. The popular forces made themselves masters of the outlying areas and the majority of the centre. The barracks were taken and the government’s resistance weakened despite the superior arms of the PSUC and Catalan state.

On the 4th of May, the popular forces were already, to a large extent, victorious[12]

But the upper committees appealed for the weapons to be laid down whether they be held by the commanders of the provoking forces or by the regional committees of the CNT weapons. Garcia Oliver, a minister in the central government, was sent by that committee to find a solution, by appealing to anti-fascist unity. It certainly seems that the Catalanists, the communists of the Generalitat and the president himself wouldn’t have been disposed to take heed of the doings of Garcia Oliver and his friends, but the anti-aircraft guns of Montjuch were in the hands of the CNT-FAI and the cannons were ready to fire at the presidential palace.

On the 5th of May, the Catalan government resigned en masse. The confederal forces didn’t dare to carry the matter to its conclusion owing to the calls for a truce and a cease-fire. But the malcontent towards the committees grew. It was thus that the “Friends of Durruti” appeared, whose pamphlet condemning the attitude of conciliation was disowned by the confederal committees in a communiqué circulated on the night of the 5th to 6th of May.

A manifesto signed by the CNT and UGT of Barcelona was broadcast on the radio. It appealed for a return to calm ...Meanwhile the police forces made attempts to improve their positions and units of the navy entered the port. The central government took public order into its hands and sent a large contingent of assault guards to Catalonia.

The appeals for calm of Garcia Oliver and Mariano Vasquez[13] were not heeded. Federica Montseny, the envoy from the central government, having miraculously escaped the enemies gunfire, managed to get to Companys and provisionally removed him from his duties in the name of the government. It seems that Companys had been awaiting the arrival of the British squadron which was in effect sailing towards Barcelona.

The CNT and the FAI, on the night of May 6th made new propositions for an end to the conflict but the fighting went on. However, during the morning of the 7th, calm seemed to fall and forces of the government entered central Barcelona, forces which guards of confederal origin had joined when it was composed, and of which the commandant was himself and old militia man of the “Terra y Libertad” column.

The regional committee of the CNT considered the “tragic incident” to be over. But there were 500 dead and 1000 people wounded. The intervening armistice was accompanied by the promise of the release of prisoners on both sides. The confederals carried out this promise while the government and the Chekists kept their prisoners and even carried out new arrests. In fact, in the Chekist prisons, many prisoners were executed and up till the 11th of May many mutilated bodies were found.

The events of May 1937 had repercussions in the whole region, so much so that confederal columns and those of the POUM remained to prevent the Stalinist elements of the 21st division from heading towards Barcelona.

We wouldn’t be able to conclude this brief outline of events without entering into evidence the assassination, on the 5th of May, of the Italian anarchist militants, Cammillo Berneri and Barbieri.[14] Berneri, wrongly presented as the leader[15] of the “Friends of Durruti” by the communists, was, as he writes himself, in a “centrist” position. However his denunciations of Stalinist crimes and his sharp and cutting criticisms of government policy (including the CNT ministers) were hitting the mark.

The governmental and Stalinist repression was not to stop with the armistice. The disbandment of the popular patrols, ordered in the decree of March the 4th was to be carried out. The campaigns against the CNT were to continue and there was also to be the monstrous case of the POUM.

But now we shall let the “Friends of Durruti” do the talking.

The ‘Friends of Durruti’ and the ‘People’s Friend’

Who Were the Friends of Durruti?

We saw, in part one, that opposition began to show itself against the lawyers who were, to a greater or lesser extent, accustomed to ministerial collaboration. Notably the Catalan Libertarian youth had declared their refusal to “become accomplices by staying silent” and they had even added “we are ready to return to illegal existence if necessary...”

In the spring[16] of 1937 a grouping of opposition militants began to come out in public under the name of the “Amigos de Durruti” and before the May days, they wrote in a leaflet:[17]

“The revolutionary and anarchist spirit of the 19th of July has lost its focus... The CNT and FAI who, during the early July days, best embodied the revolutionary direction and potential energy of the streets, today find themselves in a weakened position since they failed to trust in themselves during the days evoked above. We accepted collaboration, as minor partners, while we were by far the major force on the streets. We reinforced the representatives of the decrepit, counter-revolutionary petit bourgeois.

In no way can we tolerate the adjournment of the revolution until the end of the military conflict.

The glorious workers’ militias... are facing the danger of being transformed into a regular army which doesn’t offer the least safeguard to the working class.”

In this leaflet, the Friends of Durruti draw attention to the threat that the ‘public order’ project for Catalonia was posing.

The project was postponed but was to raise its head again. It aimed to replace the revolutionary forces in the rear with a repressive body, “neutral, amorphous, capitulating in the face of the counter revolution”. Prophetically, the Friends of Durruti added that “if such plans come to hold sway, it will not be long before we once again fill the prisons.” During the May Days they published a leaflet and a manifesto which were warmly received by the workers. Here are the contents of the leaflet (written in the midst of the action, the style is sober).

CNT-FAI, ‘Friends of Durruti’ grouping:

Workers, let us not abandon the streets. A revolutionary junta. Execution of the guilty. Disarming of the armed bodies. Socialisation of the economy. Dissolution of the political parties who have attacked the working class. We salute our comrades of the POUM (Workers party of Marxist unity) who have been at our sides in the streets. Long live the social revolution!

But who made up the “Friends of Durruti”? They called themselves an ‘agrupacion’, that is to say, not a group, but more a grouping, a rallying. They were all CNT activists, many were also members of the militias who had not agreed with militarisation, some had even left the militias when militarisation had been put in place. Others were members of the popular patrols. A good number of them were still at the front in the predominantly confederal units which had emerged from the ‘iron column’, the ‘Durruti column’ and others. But after the May days they were slandered, treated as ‘uncontrollables’, as ‘provocateurs’, even as Stalinist agents by the leadership of the CNT and FAI, or as fascist agents by the Stalinists and their allies.

It should be added that the officials of the libertarian movement were to voluntarily classify them as Trotskyists, due to their courageous defence of the POUM and its activists. The Trotskyists, extremely happy with this godsend, tried to give some credence to the rumour. Recently, issue 10 of cahiers Leon Trotski (published by the institution of the same name which is made up of various groups of the Trotskyist persuasion) published a study by F.M. Aranda on the “Friends of Durruti”. The author laboriously attempts to demonstrate the collaboration between these militants and the Trotskyists of the period. What is the truth of the matter?

The sole established fact, out of all the alleged secret agreements, is the relations between a few of the Friends of Durruti and one, yes one single Trotskyist activist, as it happens the German Hans Davis Freund, known by the pseudonym Moulin. Nothing is said about the nature of these relations, none of the names of the members of the “Friends of Durruti” in question is specified... But this seems sufficient to this ‘historian’ to speak of a “close association”! On page 83 of the same issue of the same publication, Pierre Brouff recalls, more honestly, that the “Friends of Durruti” “rejected a meeting to plan common activities”...the file is thus extremely thin.

As for the defence of the POUM, this would appear logical. The Stalinists wanted to destroy the POUM, which opposed their hegemony and defended the victims of the Moscow show-trials. Not being able to directly take on the CNT-FAI, the Stalinists blocked every alliance which was independent of them (for example the collaboration between the libertarian youth and the POUM’s youth wing). We have seen that the leaders of the CNT-FAI accepted the expulsion of the POUM from the government but that in May 1937, the libertarian workers fought side-by-side with those of the POUM.

Having said this, it should be pointed out that the politics of the POUM leadership was as disastrous as that of the CNT-FAI.

In fact, the myth of the Trotskyism of the Friends of Durruti came from the libertarian movement and the Trotskyists tried to give the myth a significance which it never had. They took advantage of the fact that the anarchist leaders, rejecting all rigorous analysis coming from their own ranks, were trying to discredit the “Friends of Durruti” and were assisting in their repression. In a milieu where the worst insult was to be labelled a ‘Marxist’, this also allowed them to avoid dealing with their urgent problems and their proper responsibilities.

In any case, the “Friends of Durruti”, who went on to publish a newspaper instead of leaflets as their mouthpiece, were to stridently stand their ground, proclaiming their adherence to revolutionary anarchism despite the disavowals and slanders that the highest circles of the official libertarian movement never failed to hurl at them. This paper EL Amigo del Pueblo, the people’s friend, was published from July to September 1937, in eight issues. In the first issue, on page 4, two long articles throw light on the attachment of the Friends of Durruti to the libertarian movement. We read, in an article entitled:

Introducing ourselves. Why we are publishing, what do we want, where are we going?

We have appeared publicly without in the least wanting to engage in personal squabbles. Our aims are loftier. The success of our aspirations is measured in days of triumph and passion for our ideas and desires.

We feel a pure love for the National Confederation of Labour and for the Anarchist Federation of Iberia. But this very attachment which we profess for these organisations which is of the same substance as our worries, incites us to confront certain insinuations which we judge as wicked and unwarranted.

The following issue included on page 3, in large type:

The association of the Friends of Durruti is made up of CNT and FAI activists. Only syndical assemblies can expel us from the Confederal organisation. Meetings of local and cantonal delegates do not have the power to expel comrades. We challenge the committees to put the question of the ‘Friends of Durruti’ to the assemblies, where the sovereignty of the organisation resides.

The attachment of the Friends of Durruti to the organisations of the libertarian movement went as far as an attempted reconciliation as we can read in the communiqué in large type on the bottom of the front page of the third issue:

Respecting the agreement reached during the plenum of groups of the FAI, and hoping that the committees of the CNT and FAI will do the same, we are making a correction to the suggestion of treason which appeared in the manifesto that came out during the May days.

We repeat what we declared during the plenum, that we didn’t attribute a sense of bad faith and negligence to the word ‘treason’. It is with that interpretation in mind that we reconsider the use of the word ‘treason’ in the hope that the committees will also rectify the suggestion of ‘agents-provocateurs’ which they have hurled at us.

We have been the first to set the record straight. We are waiting for the committees to follow the example shown here, in the very near future.

The story of this attempted compromise is again taken up in detail in issue 5, published on the 20th of July, of which most of page 3 is taken up with a solemn appeal. We see, in this text entitled “The grouping of Friends of Durruti to the workers”, how the conflict between the Friends of Durruti and the official organs of the CNT and FAI had been played out.

How, after positions had been taken in the aftermath of the May Days, despite the promises, the syndical assemblies had not been convoked to discuss the issues and how the committees had taken the decision to expel the members of the Friends of Durruti, despite the fact that the Libertarian youth and many activists were opposed to the measure. The expulsions, having been confirmed by a national plenum bringing together the regional organisations (the Andalusian regional organisation opposed the decision), were in fact rarely carried out in the unions.

The appeal to the workers which finished with cries of “long live the social revolution, long live libertarian communism” and pointed out the sympathetic mood encountered by the Friends of Durruti, was to be scarcely heard.

However, the various issues of Amigo del Pueblo contained news of significant subscriptions, of new members, of the formation of new branches, either in confederal units or in localities in Catalonia (Sans, Tarrassa or Sabadell for example).

But in a short on page 2 of issue 3, and in a large banner on the bottom of page 3 of the same issue, we learn that the Barcelona local federation of the Libertarian Youth and the Youth defence committees had informed the regional committees of the CNT and FAI of their agreement with the Friends of Durruti’s interpretation of the May days. But the grouping’s influence was to remain almost exclusively limited to Catalonia and most of the combatants in the predominantly libertarian units never even knew of their existence.[18] They lacked the means of publicising themselves; Repression both overt and hidden, exercised by the government and CNT committees was to triumph quickly.

Issue 4 of Amigo del Pueblo contained news of the arrest of Jaime Balius,[19] the chief editor of the publication, and the closure by the police of their office on No. 1 Ramblas de la Flores. The following issues were partly given over to the denouncing the escalating repression and the difficulties of publishing the paper. On September 21st 1937, the last issue, number 8, left the presses.

Thus the Friends of Durruti were unable to be the rallying point for the anarchist opposition, spread thinly in the Confederal masses and at the front. But at least they were able to leave a legacy to the proletariat, a collection of analyses and programmatic proposals which must be taken into account.

El Amigo del Pueblo

It is in this publication,[20] which has already been cited that we find the core of the programme and analysis of the Friends of Durruti. We possess copies (photo-copied) of the 8 issues of this paper, which appeared between July and the end of September 1937.

Without doubt, everything is found here, but since we are materially obliged to make a selection, we have concentrated on the more profound articles and been more restrained with regard to the polemic and apologetic articles. However something must be said about the latter due to their frequency and repetitively. This doggedness is significant, as is the style employed which is likely to surprise today’s readers.

It should be stated, even if this is less and less true, that anarchist literature (with reference to the press more than theoretical texts) makes intensive use of romantic-revolutionary lyricism. One can find long incantory passages, appealing as much to the memory of ancient Rome, as to the French revolution. What’s more, Spain has a penchant for excessively epic concoctions[21] and the language lends itself to soaring, passionate. But it certainly wouldn’t be sufficient to see this as merely the desire of the activists to express their exalted sentiments.

It represents the last flames of an epoch. Spain of 1936 was one of the last homes of the insurrectional storm which Europe had experienced during the previous century. To get back to essential matters, the fundamental problems, we have therefore selected articles and grouped them together under a certain number of topics. Each topic is indicated by a sub heading and makes reference to published articles.

Why Durruti?

Before addressing the substantial questions, there is a question which our readers certainly have the right to ask and which should certainly be answered: why the reference to Durruti?

Along with Francisco Ascaso, who was equally venerated by El Amigo del Pueblo, Buenaventura Durruti was the most popular revolutionary in 1936 Spain. Ascaso fell on the 19th of July 1936 at the head of the CNT-FAI combatants during the assault of the Atarazanas barracks. Durruti left Barcelona for the Aragon front with a column of militiamen. He then made for Madrid which was under imminent threat from the fascists. On the 20th of November he was fatally wounded in circumstances which remain obscure. His life was a series of adventures and his death on the Madrid front turned him into a legend.

To learn about the episodes of his life as much as about the circumstances of his death, Abel Paz’ book must be consulted (see the bibliography). Equally, to complement and correct it, Garcia Oliver’s book, cited above, reveals the less laudable aspects of Durruti’s personality. One point deserves clarification; Durruti, Ascaso and the whole ‘Solidarios’ affinity group would have been thought of as ‘anarcho-Bolsheviks’ by certain Spanish anarchists in the ‘20s.

They were partisans of a revolutionary alliance with other forces of the left, since strictly anarchist insurrections would have been doomed to failure. They talked of a conquest of ‘power’, after ‘the old machinery of state had been destroyed’. Such a point of view has nothing in common with ‘governmental participation’, contrary to Cesar M. Lorenzo’s claims in his book Spanish anarchists and government. Furthermore, between that old period and 1936 Durruti had evolved.

Who can say what orientation he would have had if death hadn’t come so soon? All we know is that he wanted to mobilise all energy to defeat fascism and that he had expressed his indignation and contempt for the indifference and negligence in the rear. A declaration made just before his death (and reproduced on page 4 of issue 3 of Amigo del Pueblo) condemns “the plots the internal struggles” and demands that the leaders be “sincere and construct an efficient economy to allow the running of a modern war”. He asks for the “effective mobilisation of all the workers in the rear”. He expresses reservations about the need for militarisation and affirms the efficiency of discipline at the front.

It is not certain that he would have followed, to a full extent, the decisions of the activists who were to find themselves in radical opposition to the leadership of the CNT and FAI in 1937. However, one can still understand why those activists should have chosen him as a symbol of a stern struggle without concessions.

The first page of issue 1 of Amigo del Pueblo reveals a lot. It is in colour and contains only a proclamation and slogans around a portrait of Durruti holding the flag of the CNT, the “bandera roji-negra”. Here is the essential parts of that proclamation, the tone of which is fully in the spirit of that revolutionary lyricism, which was inseparable from Spanish anarchism.

Envelloped in the folds of the red and black flag, our proletariat rose to the surface with an ardent desire for absolute liberation.

One man bestrode those sublime days. Buenaventura Durruti rooted himself in the heart of the multitudes. He fought for the workers, he died for them. His immortal past is inextricably linked to that red and black flag which gallantly floated in the majestic July dawn. On his coffin we have discharged him of his burden, in taking it upon our shoulders. With this flag held aloft, we will fall or we will overcome. There is no middle ground: to vanquish or to die.

The bottom of the page declares, in very large type:

Are we provocateurs? Are we the same old thing? Durruti is our guide! His flag is ours! Long live the FAI! Long live the CNT!

The determination to attach themselves to the memory of Durruti (and at the same time to reply to the accusation of being ‘provocateurs’ or ‘irresponsibles’) is evident in all of the following issues.

Can we talk of a cult of personality here?

And does Amigo del Pueblo answer this question?

The second issue of the paper is more given over to Francicso Ascano and indeed the two men are inseparable with regards to the esteem in which they are held by our Spanish comrades, as they were inseparable in the events which marked out their lives. But issue 3, under the heading “let us imitate the people’s heroes”, declares on page 2:

...we are mindful of our position as iconoclasts. However, Buenaventura Durruti would have been outraged by those who audaciously falsify his positions and ideas. Without lyricism or opportunism he would have unambiguously fought against the expanding schemes which are letting us lose the July revolution.

It must be understood that to imitate Durruti means neither to hesitate nor to weaken. It means that we ponder the experience of the July movement and, after analysing it, we decide that the counter-revolution will not carry the day when faced with our conception of responsibility.

Issue 5 takes up the issue again, in a more general sense. But this article, printed on page 4 in the ‘ideas’ section and entitled “no idols, no arbitrary decisions” is clearly an opinion piece, addressing those outside the Friends of Durruti.

One part of this article takes up the defence of the Friends of Durruti (the grouping is described as an “anarchist institution, created in the lingering glory which a dead leader[22] left beyond his grave”. It supports the righteousness of their fight against “the traditional centralism of every government and variety of state” and against the “incongruous” centralism of the supposed anarchists who had decreed the expulsion of the Friends of Durruti from the workers’ movement. The other part of the article deals with “the hero” and declares: “we are opposed to all types of idolatry or personal cult...” Further on, with reference to Durruti, it says:

he obtained the hero’s glory by virtue of his character and sentiments, not for his ideas. And, as regards his perfect idealism, there are other people among the anonymous masses who are not considered to be symbols and who could perhaps surpass our hero

The following issue (no 6, 12 August 1937) comes back to the question under the heading “Los Caudillos.”[23] But the ‘Caudillism’ which is denounced is that of the parties which reigns in the highest spheres of the CNT and FAI. It is the Caudillism of those who have been built up by the press and orators. It is a different matter when it concerns the “hero”.

Have we not said a thousand times that it is up to the people to choose their men and that if the people wish to give superior consideration to one than to others, that it is they who must decide? What is not acceptable is that ‘caudillos’ should be fabricated with ink and quill.

A caudillo fell in front of Madrid. Buenaventura Durruti obtained the esteem of the popular will because he acted as the people wished him to.

(...) Buenaventura Durruti was a caudillo. But he didn’t become one through petty flattery. He attained that state through the course of his life, on the street and battlefield, while those others who aspire to be caudillos were hanging out in the halls of grand hotels alongside elegant tourists

This is all that we can discover in the guise of a self-critique! Otherwise, this matter was not addressed again in the last issues of Amigo del Pueblo.

Denunciation of Ministerialism

We have seen, in the first part of our study, that a significant number of anarchist and confederal activists protested against the spirit of concession which guided the committees at the summit of the organisations.

However the advocates of governmental collaboration weren’t always cursory.[24] Thus Diego Abad de Santillan stated subtly that the necessary revolution would be carried out by the masses and that the government was merely a good instrument for waging the war.