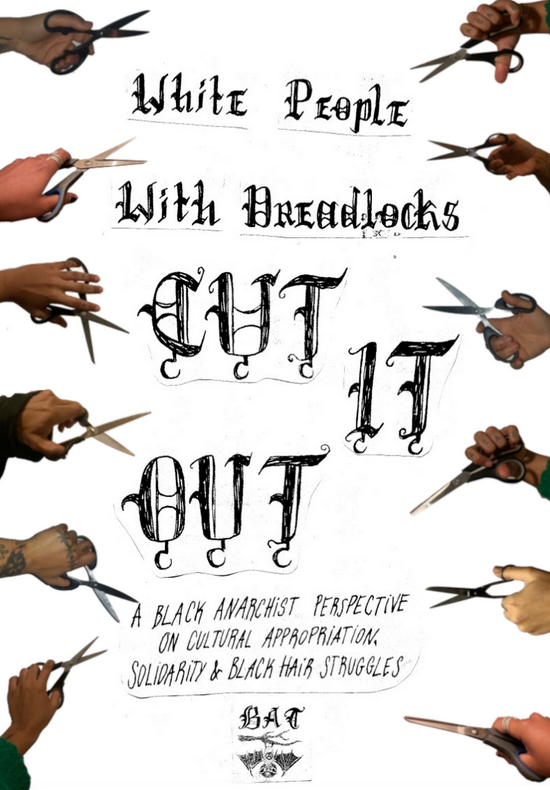

BAT (BIPOC Anarchist Team)

White People with Dreadlocks, Cut it Out

A Black Anarchist Perspective on Cultural Appropriation, Solidarity and Black Hair Struggles

Personal Insights into Black Hair’s Pain and Joys

Camila Quiñonezv – she/her — 20

Jazz – they/she – 25 – Amsterdam

Flo – They/Them – 23 — Amsterdam

Cultural Appropriation and the power dynamics entangled in hair

Myths and history of non-black people’s matted hairstyles: Celts, Vikings, Minoans and more.

Caucasian Corner: Parable of a white person who cut their locs

About BAT

BAT (BIPOC Anarchist Team) is a brand new collective of anarchists of color based in Amsterdam. We started the group to give ourselves a space to meet and organize freely without the pressure of operating within the predominantly white scene. As a new organization we have held fundraisers and community building events so that we can find each other in this vast sea of white people. We hope to continue to build community together and to work on anti-racist initiatives that have not had enough attention in other anarchist spaces.

Intro

We find ourselves at a pivotal moment in the history of black liberation. The 2020 Black Lives Matter movement repositioned and brought back mainstream attention to the hardships black people have to endure. As black folks, we are fighting to maintain this momentum and to hold the attention of white folks as allies. The deaths of our black siblings tear at our hearts, and the obvious injustices that brought these martyrs to their passing often get simplified. Some bad cops, a couple of evil racist politicians and the rise of neo-nazism are easy to blame. The nuances of racism more often get overlooked, as to white people that lack the POC experience, they might seem insignificant, or too complex to have a strong opinion on. a potent form of microaggressions endured by black people lie in our curls and the ways in which we style them. Many find cultural appropriation an exaggeration, a nit-picky point only few POC hold onto due to the bitter feelings they hold towards the white race. But if we look more deeply into the issue, we can observe how the appropriation of black hairstyles actually has very real ties to the more obvious pains we have historically endured. Locs and other black hairstyles have intimate relations to our past of slavery and our forceful displacement from our home continent. It can hurt when this meaning gets commodified and made fashionable by white folks.

This zine aims to clarify some of the reasons why many black people find it uncomfortable to see how non-black people appropriate hairstyles common in our culture. To set the tone we will first look at some personal, vulnerable insights into a couple of black people’s hair journeys. Here we will find exemplified both the struggles and empowerment weaved into our fuzzy crowns. Then, I will give an explanation of cultural appropriation and how it operates more specifically in the appropriation of black hairstyles. To give more background to this, two brief historical accounts will follow: that of black hair, and that of the alleged matted hairstyles present in non-black cultures. We will observe that contrary to the popular notion that ‘dreadlocks existed in pretty much, like, every ancient culture’, there is actually very minimal evidence for its existence in white cultures, with the exception of the Polish plait. Finally, a white comrade who used to have dreadlocks wrote a short explanation of what convinced him to change his hairstyle.

Before we proceed, let’s define what we understand under the term ‘dreadlocks’. There are various alleged origins of the word, such as that the bloodied and dirtied locs of enslaved people packed like cattle into ships were deemed ‘dreadful’ by the colonizers. Black people themselves usually refer to their ‘dreadlocks’ simply as ‘locs’, whereas white people are the most likely to use the term dreadlock or ‘dreads’. Therefore, when referring to black people I will be using the term ‘locs’, and for white people ‘dreadlocks’ or as ‘matted hair’. Now, let’s define what actually are locs.

Locs are a protective hairstyle which rely on curly hair for their structure. Black folks achieve them in different ways with a variety of looks, some examples of which include freeform, sister locs and Florida wicks. Whilst the focus of this zine is on locs, its argumentation holds for the appropriation of all hairstyles traditionally affiliated with black people, such as box braids, cornrows and bantu knots.

In this zine, I will be using a mix of ‘white people’ and ‘non-black people’ when referring to those that preferably should not be wearing their hair in locs. As will be detailed in the historical overview, there are some other oppressed cultures with a history of matted hairstyles which in my opinion are exempt from condemnation.

For context, this zine (except where mentioned otherwise) is written by black folks who are living in the Netherlands and are involved in the Dutch Anarchist scene. Through conversations with black comrades from other majority white countries, we have heard that our experiences strongly resonate and that these struggles seem to be a general problem for black people organizing for their liberation in majority white countries.

Personal Insights into Black Hair’s Pain and Joys

Camila Quiñonezv – she/her — 20

For me, the moment where I felt like I really needed to embrace my natural hair was when I was 11 years old. Before that, I had relaxed my hair a few times and I blow dried (and sometimes straightened) it every time I washed it so you can imagine how damaged my hair was. But this one time, for some reason, my mom didn’t have the time to blow dry my hair so I just went out with my hair the way it came out of the shower, but such a big part of my hair was super straight and dead. My roots were curly but the rest of the stands were straight. It was such a weird and bad sight and it was also hard to style, so me and my mom figured the straight part had to be cut off and that’s what we did. After that I never relaxed my hair and just wore my hair in an afro or in twists and it has been that way until today!

Anon

I was 17 and went to school in a class where a white girl had dreadlocks. When I mentioned I’m thinking of getting them too, my friend told me “I don’t think you need dreadlocks, you already look exotic enough”.

Jazz – they/she – 25 – Amsterdam

I don’t remember a time in my life before having relaxed hair. And let me tell you, it is not a relaxing experience. Harmful chemicals are mixed together by my mother or aunt in the kitchen (in the salons when we could afford it) and then carefully applied to your hair, usually just to the scalp as a touch-up. The process looks a lot like bleaching your hair. The result is that my hair, which grows naturally thick and kinky, was thinned out and weakened. It was easier then to blow dry and straighten, or in some cases hot combed (a hot comb was an older-school method, but essentially was a heavy metal comb placed over a stove or fire to heat it up and comb the hair with). Then, after hours of going through this process, my hair was finally straight. But it never looked quite right. It was so damaged and never grew to even reach my shoulders. And it didn’t blow in the wind like hair normally does. It was bone dry and stiff. Plus the Florida humidity caused it to puff up by the end of every school day, leading to ridicule from both my black and my white classmates.

All-in-all this was not a good experience. But it was all I ever knew. And in a way it was what I wanted. I wanted the bone-straight, long flowing hair that white people had. Why wouldn’t I, when everything I was told and shown as a child said to me, “long straight hair good, short curly hair bad!”

When I moved to Louisiana, things changed. I saw so many more Black girls rocking their natural hair in different ways. In protective styles like braids and twists and wigs. And they were so proud! How could they not be proud? Their hair was so beautiful. Without the damaging chemicals from relaxers and the damaging heat of hot combs and hair dryers, their hair grew so big. It defied gravity, and all my previously held beliefs about what I was allowed to do with my hair. So when I was 15 I went natural. I had all this dead, damaged hair that needed to be cut off so that’s what I did. Even my mother did not approve, calling my hair “messy” and “ugly,” but I didn’t care. Well I pretended not to cry but going natural was actually very hard both emotionally and in figuring out how to take care of my hair. There were some days I would cry and feel like giving up. But I stuck with it.

Fast forward to 2020 and I had a good 7 years of wearing my natural hair under my belt. I had the coolest afro in the world, and it grew so big and reached up to the sky like a flower does, and I painted it with fun colors all the time. But I wanted to try something different, something BIG. I wanted to see how my hair would look in locs. They’re kind of free form. My best friend had given me platinum blonde box braids, and when I took the braids out I left my hair in those little sections and never brushed it again. Eventually it loc’d up (and in the sections that my best friend had put in, how sweet!). I have never been happier with my hair. I love whipping it around when I dance and I love the looks in the eyes of little black girls on the street when they see me living my best life in my long colorful locs. People stare extra hard when I have them tied up in a messy bun, with different locs shooting off into different directions. I like to think they are staring in awe.

El – 16 – Arnhem, Netherlands

Hi! I’m El, I’m Dutch, Nigerian, and Ghanaian. Here’s my story about learning to embrace my natural hair in a Eurocentric society.

As a child, my parents allowed me to style my hair freely, giving me a sense of freedom. I never thought much about how I appeared to others back then.

Looking back, I faced negative reactions from family members who thought my natural hair looked “messy” or “unpresentable.”

While I grew up, I further realized I looked different from those around me. People would often stop me in the street to touch my hair, making me feel like a living petting zoo. This, as well as backhanded compliments and other microaggressions made me always wear my hair in a tight bun due to insecurity in primary school.

In high school, I began experimenting with various hairstyles, occasionally straightening my hair to “fit in.”

However, this resulted in damaged hair and the painful realization that I couldn’t change my identity.

I found interest in drawing and music, particularly punk and grunge. The punk community felt more accepting of “different” people. Artists like Poly Styrene from X-Ray Spex, who rocked her natural hair, inspired me to embrace myself.

As I delved deeper into punk and listened to bands like Bad Brains, Rage Against the Machine, X-Ray Spex, Nirvana, and Bikini Kill (advocates of intersectional feminism), I think I picked up not really giving a shit about other people’s opinions on my appearance anymore.

I now love my hair and see it as an extension to be able to express myself.

I often wear braids for convenience at work and sometimes wear my Afro, a choice my younger self would find surprising.

Through representation and accepting friends, I’ve learned to cherish my hair and couldn’t imagine myself without it.

Thanks for listening to my story:) Kisses!

Flo – They/Them – 23 — Amsterdam

When I was a little kid, I remember wanting to be white so badly that I told a white peer when I was 5 that I wish I could get injections all over my body if that would make my skin white. My envy of black kids that got their hair relaxed was great, my jealousy of other white kids’ hair even greater. I was told my hair was messy, that I should wash it more to get it untangled.

At 8 years old, I went to Benin, where my mothers side of the family is from. Here, my aunties braided my hair. It was an exciting but scary experience for me, and I couldn’t feel completely comfortable in them when I returned to the Netherlands. After my swimming cap broke due to its inability to hold my new head of hair, I asked my mom to take the braids out for me.

In my early teens, I consistently wore my hair in a tight ponytail in the nape of my neck. My pubescent social anxiety told me to keep my head down and my hair unnoticeable. When I got a little more comfortable, and the urge to adopt an alternative style won from my shyness, I started wearing my hair loose. Still, I felt immense frustration at the discrepancy between the hair tutorials for punk styles I looked at online and the working material I had on my head. This is a vulnerable piece for me to write, though the vulnerability I feel whilst discussing my struggles with my curly hair is matched at least equally by the nakedness I feel through my public admission that I was googling punk and rock chick hairstyles as an awkward tween.

Anyway, around the time I started experimenting with style I shaved my head, and whilst growing it out dyed it many colors. When it was long enough, I asked my mother to give me box braids again. Browsing the internet and seeing beautiful black people with graceful braids inspired me, and this time I loved my braids. When they grew out and it was time for a new set, my mom refused doing it for me as she didn’t agree with my color choice (lol), so I went to youtube and learnt from the black hair community how to do my own hair and how to care for it.

Nowadays, I absolutely love my hair and its versatility. I just needed to look beyond punky hairstyle youtube tutorials and find my community. I adore sharing knowledge with black friends about hair braiding techniques, where the best black beauty stores are (which are steadily disappearing from Amsterdam’s center) and what our hair care routines are. Though compliments from white people about my hair are flattering, too often what follows the compliment is the awkward request to touch my hair, or what is it made of and is that your real hair?? It can be tiring, but I believe through education and respect, people I barely know will stop asking if they can touch my hair and understand that if you admire something you do not need to own it or touch it.

Cultural Appropriation and the power dynamics entangled in hair

At the core of this debate resides the controversial concept of cultural appropriation. What exactly is it, and how does it differ from appreciation? The key to understanding the difference between appreciation and appropriation lies in the existing power structures underlying the cultural exchange. A good rule of thumb is to investigate whether the person enjoying something from another culture would receive the same backlash as a person from this culture. Another good indication is whether this cultural item or practice holds a high cultural or spiritual value within its culture. If a certain clothing item for example is reserved only for those who have undergone a certain rite of passage, an outsider wearing it just because they like the way it looks strips it of its meaning and commodifies it.

As for the backlash argument, this plays a big part in the appropriation of locs and other black hairstyles. As black folks living in a white supremacist society, we are told from a young age that our hair is strange, unruly and unprofessional. Being black in a white society, it is often an awkward and alienating experience to have differently textured hair from many of your peers, and ridicule from white kids is unfortunately a common memory we have of the playgrounds we were supposed to be safe and comfortable in. Later in life, we may be told off in high school for our hair being too ‘messy’. Eventually, work place discrimination and racist biases at job interviews often target our hair for not being seen as professional-looking. For white folks, their hair is represented everywhere, most mainstream products are marketed towards them and bullying a white person for their hair is much less common. Their hair is also rarely remarked as unprofessional when it is in its natural state.

For white people, choosing to matt your hair into dreadlocks is a fashion statement, a choice one can make out of many hairstyles. For us as black people, it is a protective hairstyle which can help us connect to a part of ourselves that may have been hard to accept. For many Black hair textures it is almost the default way it grows out. As will be elaborated on later, the suppression of black hair was a tool for enslavers to control black people and strip them of their humanity and self-expression. During the civil rights movement, our people sought to reclaim and embrace our natural hair again after a long period wherein straightened hair for black people was the norm. Dangerous scalp burning chemicals were used as an attempt to fit in within white culture, which luckily became less popular after groups like the Black Panthers and the Black Power Movement reminded us that black is beautiful, and that we should not be ashamed of our natural hair.

There is much emotion tied into our curls, and whether we loc it, braid it or let it loose, we are all trying to accept our natural hair within a society which punishes and shames us for it. A stinging example of the double standard around dreadlocks can be observed in 2015, when white fashion blogger Giuliana Rancic commented that the locs Zendaya was wearing at the Oscars looked like they ‘smelled like patchouli and weed’. The same year, Rancic praised Kylie Jenner’s dreadlocks, complimenting the ‘edgy’ look.

This leads us to another problematic stigma entangled with dreadlocks: their edge points. This is a problem especially prevalent in the anarchist and punk scenes. For some reason, there are many more white people with dreadlocks within our spaces. An explanation for this can be that since it is a hairstyle black people have been getting oppressed for having, it carries a rebellious connotation. Black people in the global North are by their very existence countercultural as we constitute a minority. The stigmatization of locs and other protective hairstyles on black people is what gives it its cool points when worn by white people.

Some white people also like wearing their hair in dreadlocks because of its attachment to the rastafarian movement and reggae music, which promotes ideas that resonate with a lot of people, like loving your neighbors and living as one with the Earth, and ignoring the powers that be. But rastafarianism is an Afro-Caribbean response to colonialism and wearing their natural hair in locs is an expression of defiance against a white supremacist culture that has disconnected them from their roots in Africa and their connection to the Earth. It is a social and political statement and it is deeply connected to their race.

Another potential explanation, which I derive from conversations I’ve had with white people with dreadlocks, is that it is meant to be a form of solidarity. Unfortunately, for many black folks, this solidarity is illegitimate as these white people wearing dreadlocks are still enjoying their privilege, and the hairstyle has different connotations in society when they wear them. There are many ways to “be in solidarity” with Black people, such as supporting Black radical organizations and fighting for things that will actually materially help Black people have easier lives, like reparations. As a European who benefits from the legacy of colonialism and slavery, and modern-day imperialism, you can even participate in mutual aid with the Black people you know. Our lives are hard, buy us a beer. That’s solidarity, not playing dress-up with your hair while still benefiting from white privilege.

Of course, not all black people are uncomfortable with white and non-black people wearing locs. We are not an absolutely unified, homogenous group of people and we hold different political beliefs. However, for myself and many of my black comrades, it demonstrates a lack of real solidarity and feels like a spit in the face for all the pain and discrimination we have faced simply for existing and wearing our natural hair in protective styles that tie us to our culture. It hurts especially when coming from white people claiming to be anti-racist, as their supposed anti-racism excludes our voices and the needs we are vocalizing. It is incredibly hard and frustrating to be an anarchist in overwhelmingly white spaces, where the conversations are often about us but rarely with us. This zine is a cry for understanding, an attempt to explain why an aspect of the anarchist scene works as a barrier for some black folks to join it. If we wish for our anarchism to be an intersectional one, we must listen to the oppressed that we claim to help, and do our best to accommodate their needs. Especially when it is as simple as choosing a hairstyle.

A common (often coming from anarchists) argument for white people being allowed to wear dreadlocks is that it is their body, their choice. Black people cannot go around policing people for the way they choose to express themselves, for the way they wish to wear their hair. And whilst yes, it is true that we can not force anybody to change how they wish to represent themselves, we can however explain why it is hurting us and why it is detrimental to our struggle. We cannot force white folks to cut their dreadlocks, but we can explain the racism inherent in it. Everybody is free to do as they wish, to say what they want. However, some of us are more free in this white capitalist patriarchal society than others, and especially when you claim to be fighting oppression, it contradicts your goals to ignore the voices of the marginalized people you are claiming to help. Just because “it’s a free country” and “you can wear your hair however you want,” doesn’t mean it’s not racist.

a Brief History of Black Hair

It is incredibly hard to determine which culture exactly was the first to wear locs. Ultimately, it is also not the most important question to answer in this debate, as what is more important is the context that has been entwined into black hairstyles historically, and how those continue to shape their perception in our current day society.

Egyptians (3150BC) are often claimed to be the first culture known to wear their hair in locs. We can see this in Egyptian paintings, but more tellingly so, evidence is found in wigs that were worn by Egyptians which featured locced hair. Wigs commonly reflected styles worn with people’s actual hair, so the found wigs make for quite a compelling case.

In many African tribes , hairstyles connote social status, family background, spirituality, tribe, class and much more. For example, the Yoruba (mainly located in modern day Nigeria, Togo and Benin) have lore detailing how a child born with hair that easily locs holds much power. The Maasai (Kenya & Tanzania) reserve locs for warriors, and use natural roots to dye them red to protect their hair from the sun. They also used their red locs as an intimidation tactic against British colonizers, and it has been rumored that the British imperials finding the locs ‘dreadful’ might be the origin of the word ‘dreadlock’. The myriad of ways to wear black hair is historically laden with meaning, and it continues to be so as the horrors of slavery transported our people to the West.

Enslaved people kept using their hair as cultural indicators. Whilst often enslaved people would have their hair shaved off before being put on ships, and sometimes again afterwards, those that kept it or regrew it cherished this part of themselves connecting them to the continent that was their home before being forcefully removed from it. Their hair was one of the only ways in which they could have authority over their own bodies, and in which they could still express themselves despite the rigorous exploitation of their bodies. Enslaved people used their hair also for practical reasons, for example braiding rice into it for emergency situations or when attempting to escape plantations. Enslavers often punished enslaved people by shaving their heads, or forced them to wear headscarves. A common reason for this was white women being jealous of the (forceful, non-consensual and aggressive) sexual attention enslaved women would get from white men.

Hair straightening emerged as a popular and common hairstyle among black folks in the early 1900’s, often burning scalps in the process to attempt to adhere to white beauty standards. Besides beauty standards, it was often necessary to ‘tame’ black hair in order to be able to find work at all and to be taken slightly more seriously by white people. Straightening black hair decreased in popularity due to the civil rights movement, with groups like the Black Panthers advocating for an embrace of natural hair, giving the fro a comeback. More visibility of black celebrities from the 60’s onward also slowly regenerated many black people’s motivation to wear their natural hair. Bob Marley spearheaded the general culture’s perception of locs, identifying them with the Rastafarian movement who wore their locs as spiritual signifiers.

Unfortunately, hair straightening and internalized shame of black hair textures persists. Black kids continue to struggle with the hair that demarcates their roots, but luckily, an increase of visibility and representation of black characters and people in media slowly aids in softening the difficult process for black folks to embrace their hair. There is hope for the black children of the future to deal less with schoolyard bullying and to freely enjoy the curls that grace their heads.

Myths and history of non-black people’s matted hairstyles: Celts, Vikings, Minoans and more.

There are a few historical occurrences of matted hairstyles in non-black cultures, often ones which had trade routes with Africa. Some of these include the Tibetan Buddhists, Hindus and ancient Hebrew Nazarites.

As for white cultures with historical proof of matted hairstyles, there circulate many myths. One of these which is commonly argued to have had ‘dreadlocks’ are the Minoans. However, there is little proof for this, as the evidence pointed towards is depictions of them in art they made. This is flimsy evidence, as the artistic depictions of their hair can also easily be interpreted as braids or simply as a way of representing hair.

The Celts are also often referenced by white people defending their dreadlocks. This myth most likely originated from a quote by a Roman who mentioned they had ‘hair like snakes’. However, there are no actual primary sources for this within the documentations that we do have of the Romans discussing the Celts. Something fun that they did do with their hair: The Gauls, a Celtic tribe, were known to use the mineral limestone to bleach, fluff up and stiffen their hair, resulting in a hairstyle reminiscent of the classic 80’s d-beat cut

The Irish were known to have a hairstyle called Glibbes. The myth that Glibbes were a matted style comes from Edmund Spencer (1596) as he said the Irish believed their Glibbes would protect them from battle, however he never says their hair is matted but rather describes it as a ‘thick bush of hair’.

Now for the most notorious alleged white dreadlock havers: the Vikings. The most problematic contradiction to them having matted hair is the fact that there are many sources detailing how the vikings combed their hair daily, something which is impossible to do with matted hair. Ahmad Ibn Fadlan wrote in the 10th century that he observed the Vikings washing and combing their hair daily in basins of water (in: ‘Account of the lands of the Turks, the Khazars, the Rus, the Saqaliba and the Bashkhirs’). In 1214 John of Wallingford also describes how the Danish ‘were wont after the fashion of their country, to comb their hair everyday’. Again, as with the Minoans, artistic depictions of vikings are claimed to be showing dreadlocks. And once more we can problematize this by arguing that they can be said to represent loose hair strands or braids. You simply can not be combing matted hair daily.

The only white culture which has historical evidence of a matted hairstyle comes from Poland. The Polish Plait was a style intertwined with folkloric belief. The idea behind it was that hair tangles and gets matted when sickness was leaving the body or when somebody was cursed by supernatural forces. It was believed that cutting off the hair would worsen illness or anger the paranormal deities. In the 17th and 18th century, the style became stigmatized due to anti-polish and anti semitic (a derogatory term for the hairstyle was the ‘Jewish Plait’) sentiments. As this is a part of Polish heritage, it is understandable that some Polish folks might want to wear it as a way to connect with their culture. The Polish plait however looks very different from other ‘dreadlock’ styles, as it is a singular matted strand rather than a headful of locs.

From this overview of white cultures mistakenly being said to have had matted hairstyles, we can see how only in Poland there is historical evidence for this. Even then, the Polish plait looks very different from how many white people wear their ‘dreadlocks’ nowadays. In more recent history, we can observe how white people on a larger scale started wearing locs around the 70’s. Possibly this was due to increasing visibility of black celebrities such as Bob Marley in the 70’s, Whoopi Goldberg in the 80’s and Lenny Kravitz and Lauryn Hill in the 90’s. Within the punk scene more specifically, around the 80’s bands like Amebix, some of whose white members wore their hair matted, can be theorized to have aided in the popularization of matted hair within the (crust) punk scene.

Caucasian Corner: Parable of a white person who cut their locs

I’ve cut off my dreadlocks because someone asked me to.

My name is Tom and I’m an activist and anarchist, moving around in anarchist circles and spaces. I organize mainly in the field of animal rights. Many years ago I wanted to be a stereotypical crust punk dandy; my long hair was starting to mat and looking up to some of the beautiful looking scene stars, I decided to mullet up and make dreads of the rest. Yes, I’m susceptible to subcultural standards. Dreads have been synonymous with crust punk since forever, and at the time they were the de facto standard for traveling punks. It’s as if they were meant to signal to each other: “I’m cool, I’ve been around.”

I can’t recall the exact moment, but around 2015, discussions about cultural appropriation, particularly problematizing the act of white individuals wearing dreads, came to my attention. Unable to exactly recall my reaction, I do think I dismissed the criticism at first, even though I did feel a vague sense of responsibility, because the criticism was directly about my behavior. Around the same time the house I lived in had a house guest, who is a person of color. The dinner table conversations I had with them went deep into antiracism and anticolonialism. One of the bigger takeaways was about the attitude of white activists in the antiracist struggle. We talked about the exclusive nature of white activist scenes and about the refusal to form thorough alliances with marginalized groups.

The point being was that true antiracism should be in support of the struggle that people of color endure in this white supremacist society. In the best-case scenario, they can appear exclusive, resembling white boys’ clubs entrenched in the habit of dominating space during demonstrations aimed at confronting outspoken Nazis. In the worst-case scenario, so-called “radical anti-racist groups” may perceive themselves as beyond criticism due to a perceived righteousness. Regardless, a colonial and racist mindset persists in both cases. I was never aware that this was seen as an obstacle for true alliance.

I was also asked to rid myself of my dreadlocks during these conversations. Not a small demand, it felt like. They were a part of my identity and they had cost time to get to this point, so I didn’t cut them off at first. Around this time the guest left the house but the gnawing request never left my thoughts. It wasn’t just the request though; it was a different perspective on a struggle that I never fully understood or will understand. But at least I had a better understanding of my position in this struggle as a so-called ally, or the prerequisites of being one. I really needed to ask myself a more accurate question: What are the conditions for me to contribute to this struggle?

For a lot of reasons this question is really tough, and I feel it should be tough. It should be a question that provokes reflection and change of attitude. But for one part it was really easy. A condition was already pointed out to me. I should cut off my dreads. So I did. In doing so, it’s important to note that I don’t see myself as a hero in this situation. I recognized a mistake and I did something about it. I should acknowledge that making this mistake in the first place was not something that could put me in any position deserving a back pat.

But why was it a mistake? Without explaining the idea of cultural appropriation, because I think that this idea is quite known by this point. People far better qualified than me have explained this many times. The mistake I want to point out the most is the inability of white people to listen to people of color. If you have a goal, no matter in which field, and the group affected the most by the outcome is completely ignored in the process, you’re doing something wrong. If you call yourself anti-racist and you’re dismissing critique by the exact group you want to ally with, you’re sabotaging the alliance. Even if you have a hard time understanding the criticism, even if you can not agree with the criticism, it’s tactically flawed to be stubborn. Here’s a rhetoric that most stubborn radicals are comfortable with: stubbornness is a comfy white privilege.

Conclusion

By now, I truly hope that it has become clear to whoever reads this and needed to learn this, just how much pain and oppression is tied to black people’s hairstyles. We have had to fight to be allowed to wear our hair in the styles native to our African ancestors, and our struggle continues. The double standards in the white supremacist society we live in imply very different consequences for black people wearing locs and white people appropriating them. Contrary to popular belief, there is very little historical evidence of matted hairstyles being a facet of white culture. Please stop saying you wear dreadlocks because of the vikings.

If you are a white person reading this, take this as a reminder to use your white privilege and to speak up to other white people who are practicing cultural appropriation. Give this zine to white people with dreadlocks that you know. Stop normalizing the appropriation of black hairstyles. Even if you are not wearing dreadlocks yourself, associating with white people with dreadlocks and remaining silent marks your complicity. Participate in the conversation, for we are tired and it is often draining for us black folks to have it. We want to feel welcome in anarchist spaces, we want to organize with white people in a comfortable way.

Hopefully, if you are a white person with dreadlocks who has read this zine, you will have learned some things about what you have on your head. The absolute best outcome would be for you to get a different hairstyle which is not tied to black people’s struggles and pain. Especially if you consider yourself anti-racist, your hairstyle is contradicting your claims of solidarity. Listen to us, for we too often have been silenced.