Various Authors

Post-anarchism Today

Editorial — Post-anarchism Today

Voluntary Servitude Reconsidered: Radical Politics and the Problem of Self-Domination

Psychoanalysis and Passionate Attachments

Conclusion: A Politics of Refusal

Postanarchism from a Marxist Perspective

The Place of Marxism within Postanarchism

Post-Structuralism and Marxism

Power and Subjectivity in Marxism

Constructivism and the Future Anterior of Radical Politics

I. Post-structuralist Anarchism’s

II. The Post-anarchism of Deleuze, Guattari, and the Zapatistas

A Multi-centered Strategy of Political Diagnosis

A Prefigurative Strategy of Political Transformation

A Participatory Strategy of Organizing Institutions

Do Black Bloc Participants See It This Way?

Anarchist Meditations, or: Three Wild Interstices of Anarchism and Philosophy

Third Wild Style: Psychogeography

Toward an Anarchist Film Theory: Reflections on the Politics of Cinema

I. The Politics of Film Theory: From Humanism to CulturalStudies

III. Toward an Anarchist Film Theory

Adrian Blackwell’s Anarchitecture: The Anarchist Tension

Deny Anarchic Spaces and Places: An Anarchist Critique of Mosaic-Statist Metageography

Metageography: Making Space Conceivable

1. Metagragraphy (Instrument): Functions

2. Metageography (Environment): Components

Metageography and Power & Dominion: The Mosaic-Statist Metageography

Denying Anarchic/ist Space and Places

1. Historical and Geographical Scope of Anarchic/ist Spaces and Places

2. Relevance of Anarchic/ist Spaces and Places

3. Delimitation and Organization of Anarchic/ist Spaces and Places

4. The Domination of Anarchic/ist Spaces and Places

Some Conclusions: A Necessary Construction of Anarchic Metageographies

1. (Critical) Reform of Mosaic-Statist Metageography

2. Construction of Antiauthoritarian Metageographies

Can Franks’ Practical Anarchism Avoid Moral Relativism?

1. Social Practices and the Rejection of Moral Universalism

The Body of the Condemned Sally: Paths to Queering anarca-Islam

The Difference Between Two Logics

Parching, She Drank the Inky Dust of Law — Sweet Honey in Her Mouth

Editorial — Post-anarchism Today

Lewis Call{1}

Welcome to Post-anarchism Today. This is certainly not USA Today, et ce n’est certainement pas Aujourd’hui en France. Indeed, it is a refreshing antidote to all such discourses of modern state capitalism. During its short but colourful existence, post-anarchism has always been libertarian and socialist in its basic philosophical outlook: that’s the anarchism part. But post-@ has also maintained its independence from modern rationalism and modern concepts of subjectivity: that’s the post- part. As I survey post-anarchism today, I find to my surprise and delight that both parts are stronger than ever. It’s now clear that post-@ is a part of anarchism, not something that stands against it. It’s equally clear that post-@ has changed anarchism in some interesting and important ways.

I speak of post-anarchism today because I believe that we are living through a post-anarchist moment. I know, I know: the owl of Minerva flies only at dusk, so how can I claim to understand the moment I’m living in? But one of the many great things about post-@ is that it means we can be done, finally, with Hegel. Minerva’s owl needs to get a job. We need a new bird, faster, more intuitive, more open source: something more like the Linux penguin. Things happen faster than they used to, and the rate of change is accelerating. Our ability to comment on these things must also accelerate. Thus I maintain that we may, in fact, study our own political and intellectual environment. Indeed, I feel that we must do this, or risk being overtaken by events. Post-anarchism waits for no one.

When I speak of post-anarchism today, I also imply that there was post-anarchism yesterday. Here I invoke the peculiar, powerful alchemy of the historian: I declare that there is an object of study called post-anarchism, and that this object already has a history. An outrageously brief narrative of that history might go something like this: post-@ was born in the mid-1980s, in Hakim Bey’s ‘Temporary Autonomous Zone’. Throughout the 90s it grew and prospered in that era’s distributed, rhizomatic networks, the Internet and the World Wide Web. Post-@ went to school in the pages of journals like Britain’s Anarchist Studies and Turkey’s Siyahi. Todd May gave it a philosophy. Saul Newman gave it a name and an interest in psychology. I encouraged post-@ to take an interest in popular culture (and vice versa). Richard J.F. Day introduced post-@ to the newest social movements: the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Thoughtful critics like Benjamin Franks developed intriguing critiques of postanarchism (Franks, 2007). Duane Rousselle and Süreyyya Evren gave post-@ a Reader. And now, here we are! Using this crazy little thing called post-anarchism to inaugurate a bold new journal, one which promises to examine the cultural environment of our postmodern age through an anarchist lens!

But wait just a minute. May, Day, Newman and Call sounds more like a law firm than a revolution. Indeed, early post-@ was justly criticized as another ivory tower phenomenon for white, male, bourgeois intellectuals. Luckily, post-anarchism today is nothing like that. It’s transnational, transethnic and transgender. It speaks in popular and populist voices, not just on the pages of academic journals like this one. Post-anarchism today is a viral collection of networked discourses which need nothing more in common than their belief that we can achieve a better world if we say goodbye to our dear old friend the rational Cartesian self, and embrace instead the play of symbol and desire. All the kids are doing it these days: the Black Bloc, the queers, the culture jammers, the anti-colonialists. Post-anarchism today is a set of discourses which speaks to a large, flexible, free-wheeling coalition of anarchist groups: activists, academics and artists, perverts, post-structuralists and peasants. As Foucault once said, ‘don’t ask who we are and don’t expect us to remain the same’. We are the whatever-singularity that lurks behind a black kerchief. We might look like Subcommander Marcos, or Guy Fawkes, or your weirdo history professor. We are everybody and we are nobody. We can’t be stopped, because we don’t even exist.

When I review the brief but exciting history of post-anarchism in this way, it suddenly seems that post-@ might possess everything it needs to constitute not merely a moment, but an actual movement. Franks (2007) has suggested that such a movement might be emerging. In the past I have hesitated to agree. After all, one doesn’t like to be accused of overblown, breathless revolutionary rhetoric. But the existence of this journal, Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies, has convinced me that the time to hesitate is through. A decade into the third millennium, post-anarchism has become a selfrealizing desire, a kind of Deleuzian desiring machine. According to the Deleuzian theories which inform most of the essays in this volume, such machines actually produce reality (Deleuze, 1983). Like all good desiring machines, post-@ operates by multiplicity. In these pages, scholars of many different nationalities, languages, ethnicities, genders, sexualities and theoretical perspectives have come together to talk about post-anarchism, its promise, its potential, its problems. This journal contains thoughtful, passionate defences of post-anarchism, and equally insightful, equally passionate critiques of it. Some of the essays in this volume are not particularly postanarchist in their outlook or method, yet even these share certain concerns with post-@: concerns, for example, about architecture, territories, the organization of space. These essays follow lines of flight which sometimes intersect with post-anarchism, and these points of intersection are rich with potential.

At least four of the articles in this issue occupy the terrain of anarchist political philosophy, which suggests that post-@ has by no means abandoned the central concerns of traditional anarchism. Saul Newman’s essay examines one of the most serious obstacles to any anarchist revolution: self-domination, or the desire we feel for our own domination. Drawing on the radical psychoanalytic tradition, Newman argues compellingly that any effective anarchist politics must directly address our psychic dependence on power. Newman’s critical project is vitally important, in that it motivates us to seek strategies by which we may overcome our complicity with political and economic power. Thus I have argued, for example, that the practices of BDSM or “kink” might satisfy our need for power without reproducing statist or capitalist power structures (Call, 2011b).

Thomas Swann’s essay extends an intriguing debate about moral universalism. Post-@ undeniably includes a dramatic critique of such universalism. Benjamin Franks (2008) has responded to this critique by deploying a “practical anarchism,” but Swann suggests that such an anarchism must either appeal to universalism or risk collapsing into moral relativism. Franks and his colleagues may yet find a third way, but Swann’s critique provides the important service of identifying the current limits of practical anarchism.

Thomas Nail’s remarkable essay argues that, having already established itself as a valid political philosophy, post-@ must now find a way to engage with the actual post-capitalist and post-statist society which is already coming into existence before our very eyes! Nail interprets Zapatismo as another kind of Deleuzian machine, the “abstract machine.” This machine is a self-initiating political arrangement which requires no preconditions other than itself. As Nail convincingly argues, such machines indicate that the post-anarchist revolution has already happened.

Simon Choat performs the extremely valuable task of reinterpreting post-anarchism from a Marxist perspective. As he correctly points out, early post-@ was theoretically fragmented. May, Newman and I all had different names for this thing we now call postanarchism. Newman recognized the importance of Lacanian psychoanalysis, while I, at first, did not. (I have since tried to correct that oversight; cf., Call, 2011a.) Choat demonstrates that opposition to Marxism was fundamental to the original articulation of post-anarchism. But he also shows the danger of such opposition. It may be that there is a kind of anti-essentialist Marxism which is compatible with post-structuralism and therefore with post-anarchism as well. So while Choat is right to say that ten years ago I feared the colonizing tendencies of Marxist theory, I don’t fear Marxism any more. Post-anarchism today is too mature and too strong to be threatened by Marxism, and we should welcome theoretical allies wherever we can find them.

I am especially happy to see that this issue contains a couple of queer interventions. Mohamed Jean Veneuse offers a groundbreaking account of transsexual politics in the Islamic world. Veneuse makes it clear that the figure of the transsexual can radically destabilize essentialist concepts of gender; what’s more, Veneuse identifies the benefits which this destabilization might offer to anarchism. The rejection of fixed identities and binary concepts of gender suggests that gender might be better understood as a project of becoming. By viewing gender more as a verb than a noun, we avoid the authoritarianism of stable subject positions. This project has clear affinities with post-@.

Meanwhile, Edward Avery-Natale offers a very different kind of queer anarchism. Avery-Natale shows how Black Bloc anarchists who might normally identify themselves as straight can temporarily and tactically embrace a queer subject position. This suggests that “queer” has become much more than a sexuality. “Queer” now names a subject position so flexible that it threatens to reveal the emptiness of subjectivity itself. Subjectivity then collapses into what AveryNatale, following Giorgio Agamben, calls the “whatever-singularity.” Queerness here refers to the negation of identity itself. Again, this project is entirely compatible with post-@. Post-anarchism shares with the “queer” Black Bloc the goal of destroying not just capital and the state, but the “anarchist subject” as such. In the words of Alan Moore’s anarchist freedom fighter V, “Let us raise a toast to all our bombers, all our bastards, most unlovely and most unforgivable. Let’s drink their health [...] then meet with them no more” (Moore & Lloyd, 1990: 248).

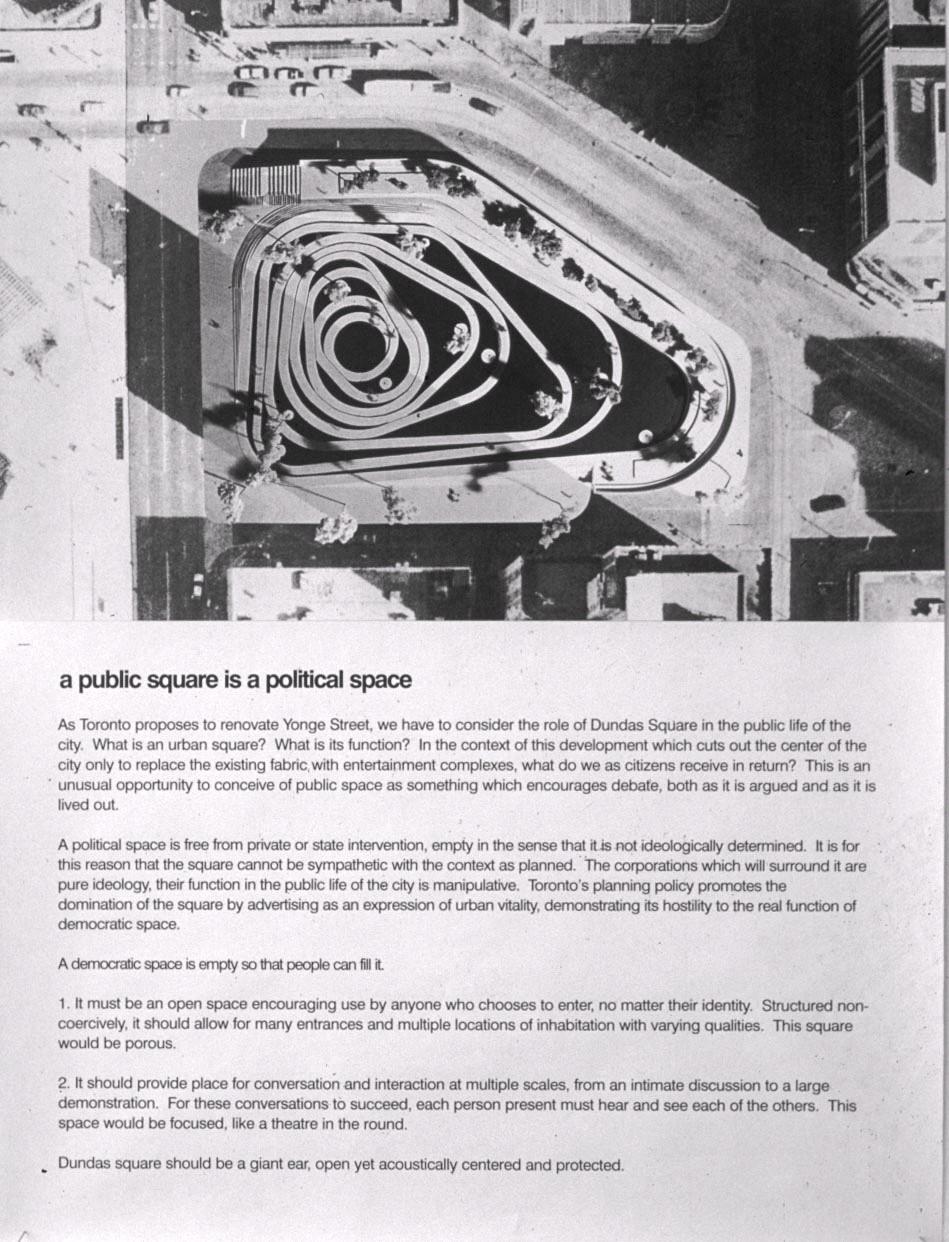

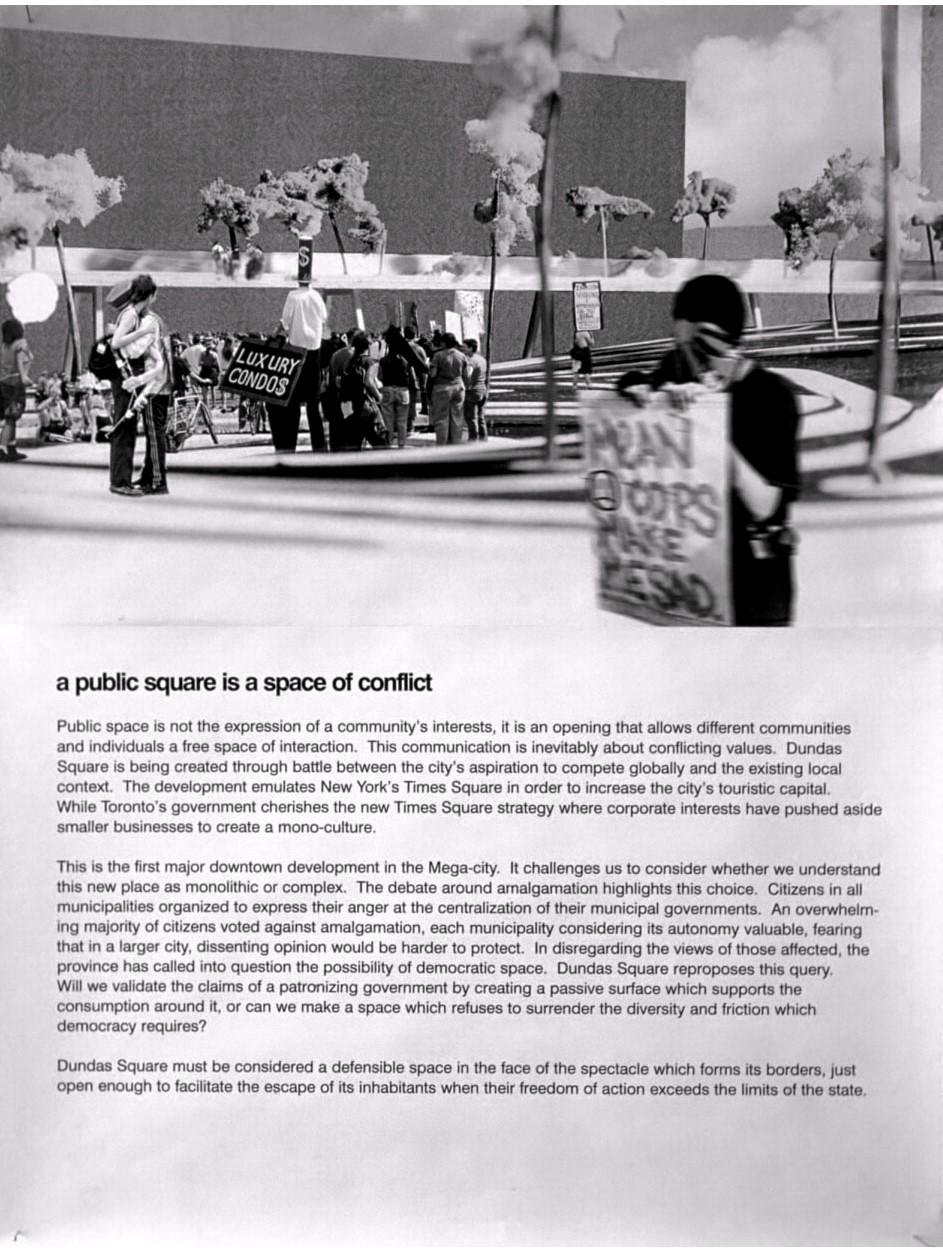

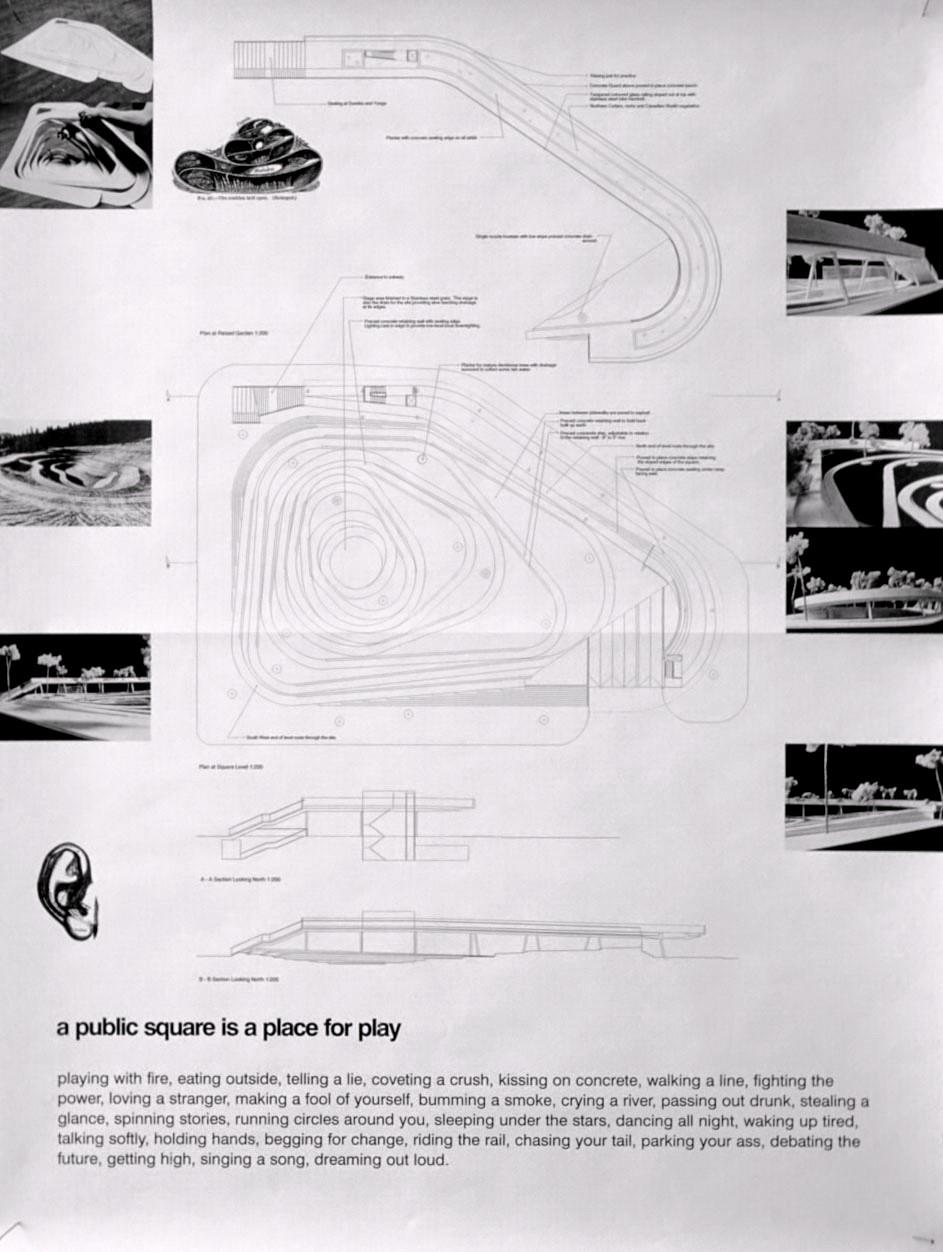

In the long run, the interdisciplinary focus of Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies may well turn out to be its strong suit. I am delighted to see that this inaugural issue contains both anarchist architectural theory and anarchist film criticism. Alan Antliff gives us a fascinating study of Adrian Blackwell’s “anarchitecture.” Blackwell’s architecture attempts to engineer a radical perspective shift which might render static power relations more open and fluid. The result, as Antliff compellingly argues, is a unique form of anarchist architecture which refuses to remain trapped within the cultural logic of capitalism.

Meanwhile, Nathan Jun offers a very ambitious anarchist film theory, one which undertakes to reveal the “liberatory potential of film.” Echoing (once again) Gilles Deleuze, Jun argues that a “genuinely nomadic cinema” is not only possible but inevitable, and that such a cinema will emerge at the juncture between producer and consumer, while blurring the distinction between the two. One need only look at the viral proliferation of quality amateur video productions on YouTube and other sites for evidence that this is already happening.

That just leaves three wild essays, one of which contains within itself (in proper fractal fashion) “Three Wild Interstices of Anarchism and Philosophy.” Alejandro de Acosta suggests that anarchism “has never been incorporated into or as an academic discipline” — though I would hasten to add, it’s certainly not for lack of trying. De Acosta makes anarchism’s apparent theoretical weakness into a virtue, arguing that anarchism really matters not as a body of abstract theory, but as a set of concrete social practices. De Acosta offers provocative examples of these practices: the meditative affirmations of the “utopians,” a speculative anthropology of geographical spaces, and a Situationist psychogeography.

These last two “wild styles” dovetail nicely with the concerns of Xavier Oliveras González, who gives us a dramatic critique of statist metageography, and simultaneously suggests an alternative. Oliveras shows the power of the high-level assumptions we make about geographic space and the ways in which it can be organized. Whoever controls metageography controls the territories it defines, and so far the state has controlled these things. But anarchist geographers like Kropotkin have been critiquing this statist metageography for over a century now. As Oliveras demonstrates, it is now possible, at last, for us to imagine a metageography which will be liberated from statist assumptions.

Finally, Erick Heroux offers us a very useful “PostAnarchia Repertoire.” Heroux thinks through the implications of today’s postmodern networks. These networks feature extensive cooperating techniques which directly implement the anarchist principle of mutual aid. Shareware, freeware and open source software represent clear alternatives to the economic logic of capitalism. Like Thomas Nail, Heroux suggests that we are no longer anticipating a future postanarchist revolution. Rather, we are studying the emergence of “an actual postanarchist society.”

So this is post-anarchism today. We offer no more visions, no more predictions, no more half-baked utopian dreams. Post-anarchism today describes the world we actually live in. It offers innovative, effective strategies for us to understand that world and engage with it. For a philosophy that was built, in part, on the renunciation of reality, post-anarchism has become surprisingly real. So use it and re-use it. Apply it and deny it. Revise it and recycle it. Let it speak to you, my fellow anarchists, and make it listen to you. Post-anarchism may not be here to stay, but it is here now, and anarchism is richer for that.

References

Call, Lewis. (2011a) “Buffy the Postanarchist Vampire Slayer.” In Postanarchism: A Reader (Duane Rousselle & Süreyyya Evren, Eds.). London: Pluto Press.

—— (2011b) “Structures of Desire: Postanarchist Kink in the Speculative Fiction of Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany.” In Anarchism and Sexuality: Ethics, Relationships and Power (Jamie Heckert & Richard Cleminson, Eds.). New York: Routledge.

Deleuze, Gilles & Felix Guattari. (1983) Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. (R. Hurley et al., Trans.) Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Franks, Benjamin. (2007) “Postanarchism: A Critical Assessment.” Journal of Political Ideologies (12)2: 127–45.

—— (2008) “Postanarchism and Meta-Ethics.” Anarchist Studies (16)2: 135–53.

Moore, Alan & David Lloyd. (1990) V for Vendetta. New York: DC Comics.

PostAnarchia Repertoire

Erick Heroux{2}

Abstract

“PostAnarchia Repertoire” is a set of discrete propositions about postanarchism. These can be read either as stand-alone units in any order, or also as a linear development that unfolds from beginning to end. The essay attempts to articulate the implied principles, themes, and concepts from across a range of contemporary postanarchist writing. Themes here include: transversality across acentric and polycentric networks; the tension between the three revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and solidarity; the potential consequences of taking equality seriously; how the anarchist criticism of representation has been complicated by the paradoxes of deconstruction; the necessity of dissensus and the appeal of paralogy and the dialogical; and finally why a polythetic definition of anarchism is more suitable than an essentialist definition.

We do not lack communication. On the contrary, we have too much of it. We lack creation. We lack resistance to the present. The creation of concepts in itself calls for a future form, for a new earth and people that do not yet exist [...] This people and this earth will not be found in our democracies. Democracies are majorities, but a becoming is by its nature that which always eludes the majority

— Deleuze & Guattari

How did we get so sad? The 20th century is the story of failed revolutions against both capitalism and empire; that is, of the communist and anticolonialist revolts. Instead, capitalism has never been so widely embraced and embracing, meanwhile the empire re-insinuates itself in neocolonial exploitation and postcolonial nationalist regimes that grotesquely abuse their own citizens. The century was a trap. When it wasn’t fascist violence that destroyed anarchism as in Spain, then it was totalitarian violence. When it wasn’t colonial violence, then it was postcolonial violence. When it wasn’t nationalism, then it was terrorism. When it wasn’t overt violence, it was an even more insidious, because covert, form of control: an economic and technical control of populations and of individuals that was difficult to name, much less to resist. We are sad because we were seduced and abandoned, forlorn lovers of humanity. This last century was not one of conspiracy, though many conspiracies succeeded. The only conspiracies allowed to succeed were those that conformed to and furthered the total drift into global capital. In an era of economic hierarchy, only the violence of the economy is permitted.

Past, present, future. Anarchism, it is often said, has passed. It was a 19th century ideology that found expression in a few bombs and assassins, the “propagandists of the deed.” Its fullest communal expression was in Spain before the fascists violently overthrew the Republic in that ultimate prelude to WWII. Hence, all anarchism has is a past, a hopeless cause in a mature world of democratic states. So goes the managed folklore. Nevertheless, an awkward present throws in with a certain return of anarchism, the “new anarchists”, the “black blocs”, the intentional communities, the temporary autonomous zones, the experimental social centers, the resurgence of publishing anarchist anthologies, classics, rereadings, and the startling reappearance of the symbol of anarchy everywhere: asserting that true order grows from anarchic liberty. It is no small irony, historic irony, that the status quo system of welfare state plus capitalism is the only one to have announced its own lack of a futurity: this has been called the “end of history” and “the end of ideology”. The present is the ultimate attainment of human abilities, the wisest compromise is conveniently located nearby: the status quo turns out to be unsurpassable, an eternal present that would be useless to oppose, since all competing alternatives have failed. Yet like an uncanny ghost, anarchism then reappears to announce that reports of its demise are premature. On the contrary, it now is reinvented as “post-contemporary theory”, calling attention to a “coming community” (Agamben) a “democracy to come” (Derrida) a “people that do not yet exist” (Deleuze & Guattari) in a paradoxically “unavowable community” (Blanchot) in which the rising “multitude” consists not of identities but instead of “singularities” (Hardt & Negri). These theories of libertarian communalism do not name themselves as anarchist — or at least only obliquely as can easily be shown in particular allusions and footnotes. But they everywhere reanimate the supposedly dead anarchist themes and rearticulate an older lexicon in neologisms for new emerging conditions. Postanarchism, therefore, asserts its future; while welfare state consumerism never tires of asserting its eternal present without any future development, in complete denial of history.

The people to come, those evoked by the great visionary artists, poets, philosophers — and here I refer to the likes of Blake, Whitman and Nietzsche — will not be clones of the proletarians, or preservations of beleaguered working class culture, or back to the severed roots of native tribes, or any essentialist identity (or foundationalist identification) whether masculine or feminine, black or white, true or false. These contemporary stylizations of radical imagery are rejected in postanarchist theory (and indeed essentialism was most often rejected in classical anarchism too). Instead, the new accent in all postanarchism is on neither preserving nor returning, but rather on becoming. The pure image of authentic proletarians or aboriginals or precolonial subalterns is now transformed and opened up to future “becoming minor”. Neither majority nor purity; but of vital concern here is the endlessly open process of becoming different from what one already was, creating a singularity rather than being an individual, branching outward rather than digging for roots. Singularities are unique clusters formed of both pre-individual elements and trans-individual elements, making up their own spaces and times. Nevertheless, what is affirmed and carried forth from the various marxisms, anti-colonialisms, and classical anarchism is what Deleuze and Guattari have listed as the source of the people to come: “an oppressed, bastard, lower, anarchical, nomadic, and irremediably minor race”.

Where are we today? Caught like pawns between the two dominant and dominating institutions that have competed with each other and cooperated with each other for access to our domination: the State and the Corporation. Our political alternative will not be to take over and become the corporation, nor the state. But rather to sidestep these institutions by way of decentralization, which undercuts both. Both of these dominating institutions operate as hierarchies. More and more they also appear to operate like networks, a diffuse power that seeps into the fabric of society itself as “governmentality” or a “biopower” that subjects us not through discipline or conformity to norms, but rather through suffusing its model of our supposed “interests” deeply and seductively into our own dreams and desires. This network power collapses the boundaries between public and private, between work and play, between home economics and the Economy. But this power, insidiously effective, is merely a contingent strategy, a screen that maintains the quite obvious hierarchies that it supports. Our alternative operation is networks too, but networks that are not screens but rather redistributions of power. Who speaks, who can be heard, who can see, who can be seen, who can decide, what is allowed to be decided upon — all of these are redistributed in genuine networks.

Networks. All kinds of networks for different purposes, using different kinds of connectivity. Oddly, network studies have shown that not every node on a network is equally decentered. Networks are potentially acentric, but in fact they evolve as polycentric: where some nodes are much more used and useful than others. The completely acentric interconnectivity is virtual, is available to be enacted; however in practice, most interconnections go through a smaller number of major hubs. The larger number of other nodes become relatively marginal, even though they are still connected to every other node, and are still potentially capable of becoming more “central”. The result is a hybrid of hierarchy and equality: both/and yet neither/nor vertical and horizontal: something in between. A new concept is called for. A diagonal, or better, transversal interaction. Networks instantiate the hybridity and the equality and the liberty and the mutual interconnectedness and the dialogical polyphony of the key postanarchist transvaluation of all values. The coming community is networked and it arrives through networked structures, and it enacts a network: polycentric when it wants to be, and yet always already decentered or acentric if wants to be. The network both enables and results from the self-organizing system of singularities in mutual connectedness.

Multinational conferences, held to official fanfare in cities named Kyoto, Seattle, Genoa, Copenhagen, etc., have repeatedly shown the failure of elite managers to come to any viable agreement about how best to partition the spoils, how to preserve privileges, how to guarantee the sustainability of capitalism, how to make power seem appealing, in sum how to save the status quo from its own poisons. This remarkable series of failures has been met by an equally remarkable series of forgettings in the muddle minded media. Whether amnesia or a wilful malice, the result has been that only an inspired group of protesters has called for an awakening from this stupor, albeit protesters usually depicted while being kicked and sprayed by the various national guards of the world, now indistinguishably attired in the uniforms of the stormtroopers from Star Wars. (The new Empire is not subtle in its symbolism.) The official negotiations attempt to preserve the status quo while making deals to cover the contradictions between nationalisms and global governance. It is only the protesters who have been able to propose an alternative to these failed negotiations: an alternative world to the business as usual model of globalization. The most acute analysis shows that another world is not only possible, but that another world is necessary. This necessary alternative is aligned with the principles of postanarchist governance.

Anarchism inspired and is inspired by that old revolutionary trinity of equality, liberty, and solidarity (I prefer this latter term to the patriarchal “brotherhood” of fraternity). Anarchism is never fully realized, but is the political ideal to be worked toward continually, more democratic than “democracy” as currently established in systems of state representation. As an ideal, it is never fully present but always a potential to bring out the best in forms of free sociality. Even amid our current States, it is anarchistic practices that thrive between the cracks of failing systems. Anarchism as a theory and praxis has been the most faithful to the old ideal trinity, and has worked to evolve practices of everyday life that cultivate a viable community — one that can negotiate the very real tensions between the three: when equality violates liberty or vice-versa; or where liberty violates solidarity, and so forth. Anarchism at its best was never just about “freedom” nor about “equality” nor about “mutual aid” in and of themselves, but rather about affirming all three despite the tensions. Acknowledging that the tension will always remain between these three revolutionary ideals, and affirming this tension as productive and valuable, is the revolutionary tense of postanarchism.

Classical anarchism radically rejected representation, that is, representatives who speak in place of others. Poststructuralist theory adds a few layers of critique to this. Postanarchism will continue to read the anarchist rejection with/through/against the poststructuralist complication of representation. The issue of representation will never be settled once and for all, as we discover that language itself is representation, and as such cannot simply be discarded, but only seen through as a construct even as it is necessarily employed. There is no pregiven natural presence that guarantees the ultimate truth of a re-presence of representation; nevertheless this also implies that all we have in terms of meaning are representations. Presence we can assume is indeed there, but the meaningfulness of this or that meaning is always a re-presentation. And representations have consequences. So far, this is Derrida in a nutshell, and begins with his point that there is no transcendental signifier, yet signification is always already underway in an interminable system of differences, where each difference that makes a meaningful difference can only do so in this very relational distinction to all the adjacent differences — which are themselves not present and not presences, but rather also relational differences. This will be a postanarchist topic, inexorably corrosive of all naturalist assumptions about identity and the proper place of my property. Representations are always de-naturalized, non-natural. Even mimesis as the direct mirroring of nature has proved to be historical instead of natural, as the history of the arts and sciences has shown. Collingwood’s history of The Idea of Nature, alongside Auerbach’s study of Mimesis in the history of literary representation come to mind as decisive illustrations of my theme: “nature” is given diverse meanings, the representation of nature slides over a range of equivocations, connotations, contradictions, modes, epistemes, genres, and does this ad infinitum. The consequence is a range of diverse meanings.

My mirror, my self. There is no essential guarantee that an authentic subject will give the true representation of that position from that position. Self-representations are just as susceptible to self-deception as are representations of the Other, and the Other’s representations of myself. Misrecognition is sometimes a projection of one’s disowned characteristics onto some other, as in Jung’s metaphor of “the shadow”; but also to misrecognize is a mirror experience. That is, to see yourself and yet not to see at all what others see when they see you. A dramatic example of the mirror as misrecognition, literalized too much no doubt, is in the Taiwanese film Yi-yi (translated as A One and a One) by the late director Edward Yang. In the film, a little boy snaps dozens of photographs of persons “behind their backs” so to speak — literally photos of their backs. The boy then presents these photos to each person as an uncanny gift. Late in the film, he is asked about this peculiar hobby. Speaking like a true artist, the boy’s answer is both precocious and yet innocent; he explains that he wants people to see a side of themselves that they normally cannot see. We don’t know what we look like to others from behind. The boy’s representations are the Other’s point of view, unavailable in the mirror. This too explains the creepiness of the famous painting by the Surrealist, Magritte, in which a man stares into a mirror and is stunned to find that he can only see his backside, but in a typically surrealist reversal, not his face. The wit here is in the implication that the real situation in everyday normality is simply a reversal of this maddening blind-spot. So likewise, cinema has the potential, sometimes fulfilled, to represent ourselves better than we have been able to see ourselves without this apparatus and without this Other perspective.

We must be suspicious of representation, even against it — but the paradox, probably the aporia, is that we cannot exist without representation. Anarchism was right to take sides against representation, and it should be emphasized that this is still important. In politics, equality and representation are in a contradictory tension, as too are liberty and representation. We must reaffirm the principle of open participation in decision making, especially enabling those who will be most affected by a decision to have the most participation in making that decision. Nevertheless, the issue of representation remains unresolved. Every representation is partial at best, distorted, perverse — including self-representation. We do not always give the best or rather only representations of ourselves. Representation itself is indeed a vexing problem — above all for anarchism — in that it isn’t a psychological or aesthetic phenomenon merely, as my allusions so far have suggested, but also an enormous political problem. I propose that we experiment in thinking further about these problems of representation by bringing in the notion of equality, from behind so to speak, to supplement the notions of individual liberty and solidarity. My emphasis on equality may seem oddly perplexing, unless you have read Rancière, who I am nominating as a postanarchist, in my representation. “Equality” is the keyword to his many works, and is the principle by which Rancière proposes to rethink democracy, education, art practice, literary interpretation, and so on. He has insisted several times that equality is not an ontological claim, nor it any kind of normative, biological, or essentialist assertion. This is a political principle, not ontological. Instead, egalité is a theoretical hypothesis to be tested: What if we, regrettably for the first time, began to take seriously the principle of equality in as many situations as possible. What if for instance, we assumed that students really are equal to their teachers — just as a thought experiment and then perhaps as praxis. We might be surprised, as Rancière’s book on the 18th-century educator, Jacotot, shows us (The Ignorant Schoolmaster). The political and pragmatic assumption of equality can lead to classroom experiences where this equality is manifested, that is, where students can teach themselves just as much as the teacher.

What if we assume that the reader is equal to the writer? What if the viewer is equal to the artist? What if everyone had in principle the same fundamental capacity to understand, to speak, to interpret? Representation, thence, would nevertheless remain problematic, but it would become, as if for the first time in history, a game of equals. Your representation of me, let us assume at the start of this game, is equal to my representation. One’s representation of one’s selfinterest is equal to, not always better than, the other’s representation of that interest. Both enter the game or contest as assumed equals, vying for attention. Again: this is not a claim about truth or eternity or reality or ontology. Being none of those, it is a political claim to think and to practice democracy. There shall be no hierarchy, and not even an overturned hierarchy in which the free individual is the monarch of his castle. Instead, we live together in a world of inevitable conflicts and competing representations. The merit of any claim informing our decision will be based on other criteria but not on the origin of that argument, whether from the subject or from the other.

Consensus or dissensus? What I have argued so far does not propose that all opinions are equal, as is sometimes said by college sophomores. Equality is a political strategy, not pure relativism. Dissenting opinions, however, are now presumed to have equal capacity and equal rights to expression as are those by established experts. Dissensus is affirmed, neither as a noble end, nor as a means to some other end such as consensus, but rather more immediately as a necessity that follows upon equality in a world of alterity. A better name here is dialogue — and not simply any old dialogue, but following Bakhtin, “the dialogical,” a logic of polyphony that includes dissonance. Moreover, in postmodern science this dissensus-as-polyphony becomes what Lyotard called “paralogy” — in which scientific models and paradigms pursue paradoxes and proliferate a broad array of theories, approaches, objects; branching out and away with innovative modes of representation, multiple epistemologies and discourses. Lyotard saw the value of dissensus not only for avant-garde scientific knowledge, but also for justice. In a world of alterity, of proliferating identities, of fluid subjectivities, of incommensurable worldviews, then how are we to arrive at justice. Which language game ought to decide this? Which epistemology ought to dominate? Lyotard and Bakhtin agree with the anarchist approach to this problem: none ought to dominate. Incommensurabilty is not the problem; domination is the problem. The problem that modernity bequeathed to us is the hegemony of a single way of thinking, of talking about truth, goodness, and beauty. The monolithic monologue of technocracy, mass production, mass media, disenchantment, Weber’s iron cage of rationality and materialism, the reduction of peoples to homo economicus delimited as a competitive self-interest, and so forth. But within this all-too-familiar modernity was a potential postmodern opening outward, sometimes activated as an oppositional modernism. The upshot is that Lyotard points out how today we could make all information equally available, and then let the games begin. The monological condition of postmodernity bears the seeds of an alternative postmodernism, a dialogical anarchism manifested on the Internet — that vast virtual world without a State, comprised of cooperating techniques and shareware, of free content freely contributed by anyone equally. The Internet is the clearest manifestation of spontaneous cooperation cutting across nations, above and beneath nations, a manifestation of the dialogical and of dissensus. The net and its world wide web do not so much prefigure a postanarchist community to come, but rather is today the planetary communicational commons of an actual postanarchist society.

How does postmodern dissensus avoid the still serious charge of careless relativism? To assume in principle the equality of potential is not to conclude in haste that this potential is automatically realized, much less that everyone’s opinion is “equally correct” or even “equally incorrect”. Although this latter negation is very tempting, it too misses the mark badly. Let us assume more precisely that everyone has the equal potential to arrive at a better view or fuller view — you and me, experts and novices, minorities and majorities, host and guest, male and female, both Kant and Hegel, Darwin and Kropotkin, Marx and Bakunin, and at the far limits of our ability to imagine even Sarah Palin and Osama bin Laden have after all is said and done, the same potential to develop an adequate representation of themselves and others. This is very far from the careless claim that all of these representations are equally true, good, or beautiful. Neither are they equally false, bad, and ugly. Again this is a great temptation that must be overcome. The principle of a politics of equal representations necessarily affirms also the value of dissensus. To the degree that this is an uncomfortable or disappointing conclusion reflects the degree of one’s mistrust in equality itself. Alternately, to the degree that this becomes acceptable, personally and politically, is the degree of trust in postanarchism.

Polythetic set: or, how to define anarchism? As a tradition, anarchism was never simply one thing. It too has a history of disagreements and even sectarian splits and at least varying emphases on any number of issues. Certainly anarchism is against domination — but then some anarchists believe in god or in the benefit of parental authority over their children. Others do not. Certainly anarchism is anti-State. Still, some anarchists argue that since transnational corporations are in many cases more powerful than the State, it would then behoove us to modulate this anti-state position to be more practically tactical in approaching social crises where the State can regulate and ameliorate some of the abusive practices of capitalism. The main tradition of anarchism was anti-capitalist and even communal. Yet some anarchists support free enterprise and even individualism. Most are modernist, but some are primitivist. Some anarchists are pacifist, while others practised “propaganda by the deed” with Molotov cocktails and more. Among the latter, some believe that violence is only to be applied against property but not against persons, while others traditionally practised assassination. Some anarchists believe in gradual reform, others in sudden revolution, while others reject both reform and revolution in favour of rebuilding the social fabric from an outside position, or perhaps inside out with alternative services, groups, and practices. These many differences are extensive and perennial, despite the occasional attempt to gather an ecumenical all-embracing “Anarchism without Adjectives” as Fernando Tarrida del Mármol called for in Cuba and also Voltairine de Cleyre in America in the late 19th century. Postanarchism obviously re-attaches an adjective. This adjective upsets some anarchists. Nevertheless, it is the noun “anarchism” not the adjective that has traditionally required this or that modifier: individualist, social, syndicalist, green, libertarian, communal, activist, pacifist, nonwestern, and so forth. I propose to think this controversial issue of definition by way of the scientific approach called “polythetic classification”. A polythetic definition is not monothetic, as in Aristotle’s approach to defining a category by its properties, which must be both necessary and sufficient. There is no monothetic definition of anarchism, since some of the aspects above are necessary but not sufficient, while others might seem sufficient, but they are not necessary. Rather than disciplining the tradition of anarchism to make it fit an essentialist definition, I suppose we could use an anarchist approach to definition, one that is non-essentialist, more inclusive, and that deflates authority. Polythetic classification appears helpful, and it is used rigorously in several branches of biology. The approach is not difficult. One notes a set of characteristics or qualities that pertain, in our case to anarchism. We then agree that so long as something has a certain number of those qualities, probably most of the qualities though not all, then it is by definition anarchism. But the set of qualities are all equal in a specific manner: none is necessary in itself. Any might be absent, but the definition would still apply if most of the characteristics applied — in any possible combination. Rather than an anarchism without adjectives, this is an anarchism with many possible adjectives.

Depending on the number of qualities or aspects of anarchism one would include in this polythetic set, the possible permutations would be either few or many, delimited and strict, or extensive and lax. Here again we encounter one of the open secrets of deconstruction: on the one hand, definitions are not set in stone, while on the other hand, they are not meaningless. Definitions do things in the real world even though they are not given as commandments on Mount Sinai. Definitions frequently slide as if slippery to our cognitive grasp. We ourselves frequently equivocate in discussion, not to mention the way definitions change in debates among the multitude. The representation of anarchism itself should be an anarchist representation, as it will have consequences. Even if we put a term under erasure in our discussion (Derrida used the Latin sous rature), even when we cross out an essentialist definition, it continues to function in a way, so that we are forced to mark its consequences for our thought. Or, it continues to be necessary even as we acknowledge that it is inaccurate. So for example, the signifier “race” might be marked as unhappily as race because even though it has been deconstructed (in effect showing that its social construction is not fundamentally grounded in any biological signified but is rather based on binary oppositions and hierarchical social formations), still the inadequate term continues to be necessary even if only in some newly distanced manner. In contemporary science, “race” is a very loose polythetic category. There is no monothetic definition for race at the level of DNA, since the necessary and/or sufficient genes don’t correspond to any social definition. Instead there is a surprising range of variation in clusters that are more polythetic. No one today really believes in race as a reified thing-in-itself, some essentialist noumenon, and yet race continues to operate with genuine consequences: sometimes as self-affirmation for ethnic groups (or what Gayatri Spivak calls “strategic essentialism”) and other times used to oppress those groups. Sometimes race is used to identify actual clusters of genetics that make a real difference in the medical treatment of disease, but always polythetically. The clusters tend to be much smaller specific populations inside of the larger groups we have learned to think of as “racial”.

In terms of the problem at hand, my suggestion is that a polythetic definition of anarchism is consonant with what anarchism aims at. This slippery yet consequential sensibility about “anarchism” itself is partly what is meant by the signifier “postanarchism”. And it should be of further interest to anarchists that this approach is itself faithful to an post-anarchist epistemology, wherein most of the set of characteristics that variously define anarchism are now retroactively shown to be applicable to an epistemology: how do we know, and how do we adequately represent our reality? Well, without authoritarianism, domination, or monologue; but with liberty, equality, and solidarity. In sum, with genuine respect for the dialogical principle, for participation, for the equality of potential, for innovation, proliferation, dissensus, paralogy, polycentrism, transversality of connections, and openness to the sharing of information by all, from all, to all, without limits. With this as our repertoire, let the games commence.

Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies

“Post-Anarchism today”

2010.1

Voluntary Servitude Reconsidered: Radical Politics and the Problem of Self-Domination

Saul Newman{3}

Abstract

In this paper I investigate the problem of voluntary servitude — first elaborated by Etienne de la Boëtie — and explore its implications for radical political theory today. The desire for one’s own domination has proved a major hindrance to projects of human liberation such as revolutionary Marxism and anarchism, necessitating new understandings of subjectivity and revolutionary desire. Central here, as I show, are micro-political and ethical projects of interrogating one’s own subjective attachment to power and authority — projects elaborated, in different ways, by thinkers as diverse as Max Stirner, Gustav Landauer and Michel Foucault. I argue that the question of voluntary servitude must be taken more seriously by political theory, and that an engagement with this problem brings to the surface a countersovereign tradition in politics in which the central concern is not the legitimacy of political power, but rather the possibilities for new practices of freedom.

Introduction

In this paper I will explore the genealogy of a certain countersovereign political discourse, one that starts with the question ‘why do we obey?’ This question, initially posed by the philosopher Etienne de la Boëtie in his investigations on tyranny and our voluntary servitude to it, starts from the opposite position to the problematic of sovereignty staked out by Bodin and Hobbes. Moreover, it remains a central and unresolved problem in radical political thought which works necessarily within the ethical horizon of emancipation from political power. I suggest that encountering the problem of voluntary servitude necessitates an exploration of new forms of subjectivity, ethics and political practices through which our subjective bonds to power are interrogated; and I explore these possibilities through the revolutionary tradition of anarchism, as well as through an engagement with psychoanalytic theory. My contention here is that we cannot counter the problem of voluntary servitude without a critique of idealization and identification, and here I turn to thinkers like Max Stirner, Gustav Landauer and Michel Foucault, all of whom, in different ways, develop a micropolitics and ethics of freedom which aims at undoing the bonds between the subject and power.

The Powerlessness of Power

The question posed by Etienne De La Boëtie in the middle of the sixteenth century in Discours de la servitude volontaire, ou Le Contr’Un, remains with us today and can still be considered a fundamental political question:

My sole aim on this occasion is to discover how it can happen that a vast number of individuals, of towns, cities and nations can allow one man to tyrannize them, a man who has no power except the power they themselves give him, who could do them no harm were they not willing to suffer harm, and who could never wrong them were they not more ready to endure it than to stand in his way (Etienne De La Boëtie, 1988).

La Boëtie explores the subjective bond which ties us to the power that dominates us, which enthrals and seduces us, blinds us and mesmerizes us. The essential lesson here is that the power cannot rely on coercion, but in reality rests on our power. Our active acquiescence to power at the same time constitutes this power. For La Boëtie, then, in order to resist the tyrant, all we need do is turn our backs on him, withdraw our active support from him and perceive, through the illusory spell that power manages to cast over us — an illusion that we participate in — his weakness and vulnerability. Servitude, then, is a condition of our own making — it is entirely voluntary; and all it takes to untie us from this condition is the desire to no longer be subjugated, the will to be free.

This problem of voluntary servitude is the exact opposite of that raised by Hobbes a century later. Whereas for La Boëtie, it is unnatural for us to be subjected to absolute power, for Hobbes it is unnatural for us to live in any other condition; the anarchy of the state of nature, for Hobbes, is precisely an unnatural and unbearable situation. La Boëtie’s problematic of self-domination thus inverts a whole tradition of political theory based on legitimizing the sovereign — a tradition that is still very much with us today. La Boëtie starts from the opposite position, which is that of the primacy of liberty, self-determination and the natural bonds of family and companionship, as opposed to the unnatural, artificial bonds of political domination. Liberty is something which must be protected not so much against those who wish to impose their will on us, but against our own temptation to relinquish our liberty, to be dazzled by authority, to barter away our liberty in return for wealth, positions, favours, and so on. What must be explained, then, is the pathological bond to power which displaces the natural desire for liberty and the free bonds that exist between people.

Boëtie’s explanations for voluntary servitude are not entirely adequate or convincing, however: he attributes it to a kind of denaturing, whereby free men become effeminate and cowardly, thus allowing another to dominate them. Nevertheless, he raises, I think, one of the fundamental questions for politics — and especially for radical politics — namely, why do people at some level desire their own domination? This question inaugurates a counter-sovereign political theory, a libertarian line of investigation which is taken up by a number of thinkers. Wilhelm Reich, for instance, in his Freudo-Marxist analysis of the mass psychology of fascism, pointed to a desire for domination and authority which could not be adequately explained through the Marxist category of ideological false consciousness (Reich, 1980). Pierre Clastres, the anthropologist of liberty, saw the value of La Boëtie in showing us the possibility that domination is not inevitable; that voluntary servitude resulted from a misfortune of history (or pre-history), a certain fall from grace, a lapse from the condition of primitive freedom and statelessness into a society divided between dominators and the dominated. Here, man occupies the condition of the unnameable (neither man nor animal): so alienated is he from his natural freedom, that he freely chooses, desires, servitude — a desire which was entirely unknown in primitive societies (Clastres, 1994: 93–104). Following on from Clastres’ account, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari explored the emergence of the state, and the way in which it relies not so much, or not entirely, on violent domination and capture, but rather on the self-domination of the subject at the level of his or her desire — a repression which is itself desired. The state acts to channel the subject’s desire through authoritarian and hierarchical structures of thought and modes of individualization.[1]

Moreover, the Situationist Raoul Vanegeim showed, in an analysis that bears many a striking likeness to La Boëtie’s, that our obedience is bought and sustained by minor compensations, a little bit of power as a psychological pay-off for the humiliation of our own domination:

Slaves are not willing slaves for long if they are not compensated for their submission by a shred of power: all subjection entails the right to a measure of power, and there is no such thing as power that does not embody a degree of submissions. That is why some agree so readily to be governed (Vanegeim, 1994: 132).

Another Politics...?

The problem of self-domination shows us that the connection between politics and subjectification must be more thoroughly investigated. To create new forms of politics — which is the fundamental theoretical task today — requires new forms of subjectivity, new modes of subjectivisation. Moreover, to counter voluntary servitude will involve new political strategies, indeed a different understanding of politics itself. Quite rightly, La Boëtie recognizes the potential for domination in any democracy: the democratic leader, elected by the people, becomes intoxicated with his own power and teeters increasingly towards tyranny. Indeed, we can see modern democracy itself as an instance of voluntary servitude on a mass scale. It is not so much that we participate in an illusion whereby we are deceived by elites into thinking we have a genuine say in decision-making. It is rather that democracy itself has encouraged a mass contentment with powerlessness and a general love of submission.

As an alternative, La Boëtie asserts the idea of a free republic. However, I would suggest that the inverse of voluntary servitude is not a free republic, but another form of politics entirely. Free republics have a domination of their own, not only in their laws, but in the rule of the rich and propertied classes over the poor. Rather, when we consider alternative forms of politics, when we think about ways of enacting and maximizing the possibilities of non-domination, I think we ought to consider the politics of anarchism — which is a politics of anti-politics, a politics which seeks the abolition of the structures of political power and authority enshrined in the state.

Anarchism, this most heretical of radical political philosophies, has led for a long time a marginalized existence. This is due in part to its heterodox nature, to the way it cannot be encompassed within a single system of ideas or body of thought, but rather refers to a diverse ensemble of ideas, philosophical approaches, revolutionary practices and historical movements and identities. However, what makes a reconsideration of anarchist thought essential here is that out of all the radical traditions, it is the one that is most sensitive to the dangers of political power, to the potential for authoritarianism and domination contained within any political arrangement or institution. In this sense, it is particularly wary of the bonds through which people are tied to power. That is why, unlike the MarxistLeninists, anarchists insisted that the state must be abolished in the first stages of the revolution: if, on the other hand, state power was seized by a vanguard and used — under the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ — to revolutionize society, it will, rather than eventually ‘withering away’, expand in size and power, engendering new class contradictions and antagonisms. To imagine, in other words, that the state was a kind of neutral mechanism that could be used as a tool of liberation if the right class controlled it, was, according to the classical anarchists of the nineteenth century, engaged as they were in major debates with Marx, a pure fantasy that ignored the inextricable logic of state domination and the temptations and lures of political power. That was why the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin insisted that the state must be examined as a specific structure of power which could not be reduced to the interests of a particular class. It was — in its very essence — dominating: “And there are those who, like us, see in the State, not only its actual form and in all forms of domination that it might assume, but in its very essence, an obstacle to the social revolution” (Kropotkin, 1943). The power of the state, moreover, perpetuates itself through the subjective bond that it forms with those who attempt to control it, through the corrupting influence it has on them. In the words of another anarchist, Mikhail Bakunin, “We of course are all sincere socialists and revolutionists and still, were we to be endowed with power [...] we would not be where we are now” (Bakunin, 1953: 249).

This uncompromising critique of political power, and the conviction that freedom cannot be conceived within the framework of the state, is what distinguishes anarchism from other political philosophies. It contrasts with liberalism, which is in reality a politics of security, where the state becomes necessary to protect individual liberty from the liberty of others: indeed, the current securitization of the state through the permanent state of exception reveals the true face of liberalism. It differs also in this respect from socialism, which sees the state as essential for making society more equal, and whose terminal decline can be witnessed in the sad fate of social democratic parties today with their authoritarian centralism, their law and order fetishes and their utter complicity with global neoliberalism. Furthermore, anarchism is to be distinguished from revolutionary Leninism, which now represents a completely defunct model of radical politics. What defines anarchism, then, is the refusal of state power, even of the revolutionary strategy of seizing state power. Instead, the focus of anarchism is on self-emancipation and autonomy, something which cannot be achieved through parliamentary democratic channels or through revolutionary vanguards, but rather through the development of alternative practices and relationships based on free association, equal liberty and voluntary cooperation.

It is because of its alterity or exteriority to other state-centred modes of politics that anarchism has been largely overshadowed within the radical political tradition. Yet, I would argue that currently we are in a kind of anarchist moment politically. What I mean is that with the eclipse of the socialist state project and revolutionary Leninism, and with the devolving of liberal democracy into a narrow politics of security, that radical politics today tends to situate itself increasingly outside the state. Contemporary radical activism seems to reflect certain anarchist orientations in its emphasis on decentralized networks and direct action, rather than party leadership and political representation. There is a kind of disengagement from state power, a desire to think and act beyond its structures, in the direction of greater autonomy. These tendencies are becoming more pronounced with the current economic crisis, something which is pointing to the very limits of capitalism itself, and certainly to the end of the neoliberal economic model. The answer to the failings of neoliberalism is not more state intervention. It is ludicrous to talk about the return of the regulatory state: the state in fact never went away under neoliberalism, and the whole ideology of economic ‘libertarianism’ concealed a much more intensive deployment of state power in the domain of security, and in the regulation, disciplining and surveillance of social life. It is clear, moreover, that the state will not help us in this current situation; there is no point looking to it for protection. Indeed, what is emerging is a kind of disengagement from the state; the coming insurrections will challenge the hegemony of the state, which we see increasingly governing through the logic of exception.

Moreover, the relevance of anarchism is also reflected at a theoretical level. Many of themes and preoccupations of contemporary continental thinkers for instance — the idea of non-state, non-party and post-class forms of politics, the coming of the multitudes and so on — seem to invoke an anarchist politics. Indeed, this is particularly evident in the search for a new political subject: the multitudes of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, the people for Ernesto Laclau, the excluded part-of-no-part for Jacques Rancière, the figure of the militant for Alain Badiou; all this reflects an attempt to think about new modes of subjectification which are perhaps broader and less constraining than the category of the proletariat as politically constituted through the Marxist-Leninist vanguard. A similar approach to political subjectivity was proposed by the anarchists in the nineteenth century, who claimed that the Marxist notion of the revolutionary class was exclusivist, and who sought to include the peasantry and lumpenroletariat as revolutionary identities.[2] In my view, anarchism is the ‘missing link’ in contemporary continental political thought — a spectral presence which is never really acknowledged.[3]

The Anarchist Subject

Anarchism is a politics and ethics in which power is continually interrogated in the name of human freedom, and in which human existence is posited in the absence of authority. However, this raises the question of whether there is an anarchist subject as such. Here I would like to reconsider anarchism through the problem of voluntary servitude. While the classical anarchists were not unaware of the desires for power that lay at the heart of the human subject — which is why they were so keen to abolish the structures of power which would incite these desires — the problem of self-domination, the desire for one’s own domination, remains insufficiently theorized in anarchism.[4] For the anarchists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries — such as William Godwin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin — conditioned as they were by the rationalist discourses of Enlightenment humanism, the human subject naturally desired freedom; thus the revolution against state power was part of the rational narrative of human emancipation. The external and artificial constraints of state power would be thrown off, so that man’s essential rational and moral properties could be expressed and society could be in harmony with itself. There is a kind of Manichean opposition that is presupposed in classical anarchist thought, between human society which is governed by natural laws, and political power and man-made law, embodied in the state, which is artificial, irrational and a constraint on the free development of social forces. There is, furthermore, an innate sociability in man — a natural tendency, as Kropotkin saw it, towards mutual aid and cooperation — which was distorted by the state, but which, if allowed to flourish, would produce a social harmony in which the state would become unnecessary (cf., Kropotkin, 2007).

While the idea of a society without a state, without sovereignty and law is desirable, and indeed the ultimate horizon of radical politics, and while there can be no doubt that political and legal authority is an oppressive encumbrance on social life and human existence generally, what tends to be obscured in this ontological separation between the subject and power is the problem of voluntary servitude — which points to the more troubling complicity between the subject and the power that dominates him. To take this into account, to explain the desire for self-domination and to develop strategies — ethical and political strategies — to counter it, would be to propose an anarchist theory of subjectivity, or at least a more developed one than can be found in classical anarchist thought. It would also imply a move beyond some of the essentialist and rationalist categories of classical anarchism, a move that elsewhere I have referred to as postanarchism (Newman, 2010). This is not to suggest that the classical anarchists were necessarily naïve about human nature or politics; rather that its humanism and rationalism resulted in a kind of blind-spot around the question of desire, whose dark, convoluted, self-destructive and irrational nature would be revealed later by psychoanalysis.

Psychoanalysis and Passionate Attachments

So it is important to explore the subjective bond to power at the level of the psyche.[5] A psychological dependency on power, which was explored by Freudo-Marxists such as Marcuse and Reich[6], meant that the possibilities of emancipatory politics are at times compromised by hidden authoritarian desires; that there was always a risk of authoritarian and hierarchical practices and institutions emerging in post-revolutionary societies. The central place of the subject — in politics, philosophy — is not abandoned here but complicated. Radical political projects, for instance, have to contend with the ambiguities of human desire, with irrational social behaviour, with violent and aggressive drives, and even with unconscious desires for authority and domination.

This is not to suggest that psychoanalysis is necessarily politically or socially conservative. On the contrary, I would maintain that central to psychoanalysis is a libertarian ethos by which the subject seeks to gain a greater autonomy, and where the subject is encouraged, through the rules of ‘free association’, to speak the truth of the unconscious.[7] To insist on the ‘dark side’ of the human psyche — its dependence on power, its identification with authoritarian figures, its aggressive impulses — can serve as a warning to any revolutionary project which seeks to transcend political authority. This was really the same question that was posed by Jacques Lacan in response to the radicalism of May ’68: “the revolutionary aspiration has only a single possible outcome — of ending up as the master’s discourse. This is what experience has proved. What you aspire to as revolutionaries is a master. You will get one” (Lacan, 2007: 207). What Lacan is hinting at with this rather ominous prognostication — one that could be superficially, although, in my view, incorrectly, interpreted as politically conservative — is the hidden link, even dependency, between the revolutionary subject and authority; and the way that movements of resistance and even revolution may actually sustain the symbolic efficiency of the state, reaffirming or reinventing the position of authority.

Psychoanalysis by no means discounts the possibility of human emancipation, sociability and voluntary cooperation: indeed, it points to conflicting tendencies in the subject between aggressive desires for power and domination, and the desire for freedom and harmonious co-existence. As Judith Butler contends, moreover, the psyche — as a dimension of the subject that is not reducible to discourse and power, and which exceeds it — is something that can explain not only our passionate attachments to power and (referring to Foucault) to the modes of subjectification and regulatory behaviours that power imposes on us, but also our resistance to them (Butler, 1997: 86).

Ego Identification

One of the insights of psychoanalysis, something that was revealed, for instance, in Freud’s study of the psychodynamics of groups, was the role of identification in constituting hierarchical and authoritarian relationships. In the relationship between the member of the group and the figure of the Leader, there is a process of identification, akin to love, in which the individual both idealizes and identifies with the Leader as an ‘ideal type’, to the point where this object of devotion comes to supplant the individual’s ego ideal (Freud, 1955). It is this idealization that constitutes the subjective bond not only between the individual and the Leader of the group, but also with other members of the group. Idealization thus becomes a way of understanding voluntary submission to the will of authoritarian leaders.

However, we also need to understand the place of idealization in politics in a broader sense, and it is here that, I would argue, the thinking of the Young Hegelian philosopher, Max Stirner, becomes important. Stirner’s critique of Ludwig Feuerbach’s humanism allows us to engage with this problem of self-domination. Stirner shows that the Feuerbachian project of replacing God with Man — of reversing the subject and predicate so that the human becomes the measure of the divine rather than the divine the human (Feuerbach, 1957) — has only reaffirmed religious authority and hierarchy rather than displacing it. Feuerbach’s ‘humanist insurrection’ has thus only succeeded in creating a new religion — Humanism — which Stirner connects with a certain self-enslavement. The individual ego is now split between itself and an idealized form of itself now enshrined in the idea of human essence — an ideal which is at the same time outside the individual, becoming an abstract moral and rational spectre by which he measures himself and to which he subordinates himself. As Stirner declares: “Man, your head is haunted [...] You imagine great things, and depict to yourself a whole world of gods that has an existence for you, a spirit-realm to which you suppose yourself to be called, an ideal that beckons to you” (Stirner, 1995: 43).

For Stirner, the subordination of the self to these abstract ideals (‘fixed ideas’) has political implications. Humanism and rationalism become in his analysis the discursive thresholds through which the desire of the individual is bound to the state. This occurs through identification with state-defined roles of citizenship, for instance. Moreover, for Stirner, in a line of thought that closely parallels La Boëtie’s, the state itself is an ideological abstraction which only exists because we allow it to exist, because we abdicate our own power over ourselves to what he called the ‘ruling principle’. In other words, it is the idea of the state, of sovereignty, that dominates us. The state’s power is in reality based on our power, and it is only because the individual has not recognized this power, because he humbles himself before an external political authority, that the state continues to exist. As Stirner correctly surmised, the state cannot function only through repression and coercion; rather, the state relies on us allowing it to dominate us. Stirner wants to show that ideological apparatuses are not only concerned with economic or political questions — they are also rooted in psychological needs. The dominance of the state, Stirner suggests, depends on our willingness to let it dominate us:

What do your laws amount to if no one obeys them? What your orders, if nobody lets himself be ordered? [...] The state is not thinkable without lordship [Herrschaft] and servitude [Knechtschaft] (subjection); [...] He who, to hold his own, must count on the absence of the will in others is a thing made by these others, as the master is a thing made by the servant. If submissiveness ceased it would be all over with lordship (Stirner, 1995: 174–5).

Stirner was ruthlessly and relentlessly criticized by Marx and Engels as ‘Saint Max’ in The German Ideology: they accused him of the worst kind of idealism, of ignoring the economic and class relations that form the material basis of the state, and thus allowing the state to be simply wished out of existence. However, what is missed in this critique is the value of Stirner’s analysis in highlighting the subjective bond of voluntary servitude that sustains state power. It is not that he is saying that the state does not exist in a material sense, but that its existence is sustained and supplemented through a psychic attachment and dependency on its power, as well as the acknowledgement and idealization of its authority. Any critique of the state which ignores this dimension of subjective idealization is bound to perpetuate its power. The state must first be overcome as an idea before it can be overcome in reality; or, more precisely, these are two sides of the same process.

The importance of Stirner’s analysis — which broadly fits into the anarchist tradition, although breaks with its humanist essentialism in important ways[8] — lies in exploring this voluntary self-subjection that forms the other side of politics, and which radical politics must find strategies to counter. For Stirner, the individual can only free him or herself from voluntary servitude if he abandons all essential identities and sees himself as a radically self-creating void:

I on my part start from a presupposition in presupposing myself; but my presupposition does not struggle for its perfection like ‘Man struggling for his perfection’, but only serves me to enjoy it and consume it [...] I do not presuppose myself, because I am every moment just positing or creating myself (Stirner, 1995: 150).

While Stirner’s approach is focused on the idea of the individual’s self-liberation — from essences, fixed identities — he does raise the possibility of collective politics with his notion of the ‘union of egoists’, although in my view this is insufficiently developed. The breaking of the bonds of voluntary servitude cannot be a purely individual enterprise. Indeed, as La Boëtie suggests, it always implies a collective politics, a collective rejection of tyrannical power by the people. I am not suggesting that Stirner provides us with a complete or viable theory of political and ethical action. However, the importance of Stirner’s thought lies in the invention of a micropolitics, an emphasis on the myriad ways we are bound to power at the level of our subjectivity, and the ways we can free ourselves from this. It is here that we should pay close attention to his distinction between the Revolution and the insurrection:

Revolution and insurrection must not be looked upon as synonymous. The former consists in an overturning of conditions, of the established condition or status, the state or society, and is accordingly a political or social act; the latter has indeed for its unavoidable consequence a transformation of circumstances, yet does not start from it but from men’s discontent with themselves, is not an armed rising but a rising of individuals, a getting up without regard to the arrangements that spring from it. The Revolution aimed at new arrangements; insurrection leads us no longer to let ourselves be arranged, but to arrange ourselves, and sets no glittering hopes on ‘institutions’. It is not a fight against the established, since, if it prospers, the established collapses of itself; it is only a working forth of me out of the established (Italics are Stirner’s; Stirner, 1995: 279–80).

We can take from this that radical politics must not only be aimed at overturning established institutions like the state, but also at attacking the much more problematic relation through which the subject is enthralled to and dependent upon power. The insurrection is therefore not only against external oppression, but, more fundamentally, against the self’s internalized repression. It thus involves a transformation of the subject, a micro-politics and ethics which is aimed at increasing one’s autonomy from power.

Here we can also draw upon the spiritual anarchism of Gustav Landauer, who argued that there can be no political revolution — and no possibility of socialism — without at the same time a transformation in the subjectivity of people, a certain renewal of the spirit and the will to develop new relationships with others. Existing relationships between people only reproduce and reaffirm state authority — indeed the state itself is a certain relationship, a certain mode of behaviour and interaction, a certain imprint on our subjectivity and consciousness (and I would argue on our unconscious) and therefore it can only be transcended through a spiritual transformation of relationships. As Landauer says, “we destroy it by contracting other relationships, by behaving differently” (in Martin Buber, 1996: 47).

A Micro-Politics of Liberty