London, 1949

Scanning by Charlatan Stew recollectionbooks.com

Various Authors

Marie Louise Berneri 1918–1949. A Tribute

Marie Louise Berneri Memorial Committee

From a French Comrade. S. Parane, Paris

From a letter to her companion. Paris, 19th March, 1936 (in French)

To her companion. Paris, 4th October, 1936 (in Italian)

3. Her Contribution to Freedom Press

From a Spanish Refugee. Manuel Salgado, London

A Visit to Glasgow (1945, letter to her companion in prison)

A Tribute from George Woodcock (writing from Vancouver)

From an American Jewish Paper, Freie Arbeiter Stimme (New York), 8 July, 1949

From a Mexican Paper, Solidaridad Obrera (Mexico City), 1 May, 1949

From a South American Paper, Boletin Informativo (Buenos Aires), July, 1949

From Sweden, I.W.M.A. Press Service (Stockholm), 8 June, 1949

* * * * *

Marie Louise Berneri Memorial Committee

The Committee exists to perpetuate the name of Marie Louise Berneri. Besides the present volume, we shall be editing a selection of her writings for publication in 1950, as well as arranging with her publishers for a special edition of A Journey through Utopia to be made available to her friends and comrades. At a later date we shall publish a full-length biography of Marie Louise.

We propose also to publish a series of volumes of works, some of which have been out of print for many years, whilst many will be available for the first time in the English language, which had a deep influence on Marie Louise’s life and work, and which she had often expressed the hope of seeing one day published in this country.

This, then, will be our memorial to Marie Louise Berneri. It can only be realised, however, with the material support of those who loved her as a friend or who shared her hopes for a happier world.

— November, 1949, Marie Louise Berneri Memorial Committee, 27, Red Lion Street, London, W.C.1.

In Memory of M.L.B. (poem)

Into the silence of the sun

Risen in dust the rose is gone,

The blood that burned along the briar

Branches invisibly on the air.

Flame into flame’s petal

Her grief extends our grief,

Over the ashy heat-ways

A green glance from a leaf

Shivers the settled trees.

A child walks in her grace

The light glows on his face,

Where the great rose has burned away

Within the terrible silence of the day.— Louis Adeane

1. Introduction

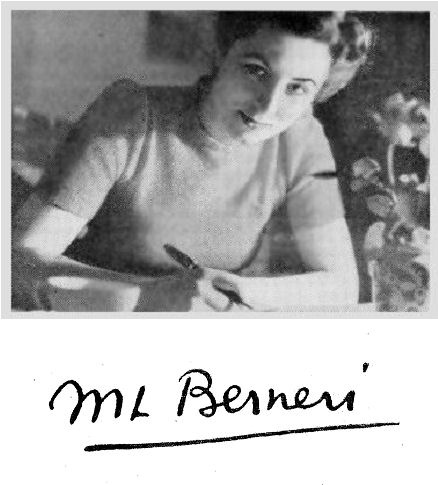

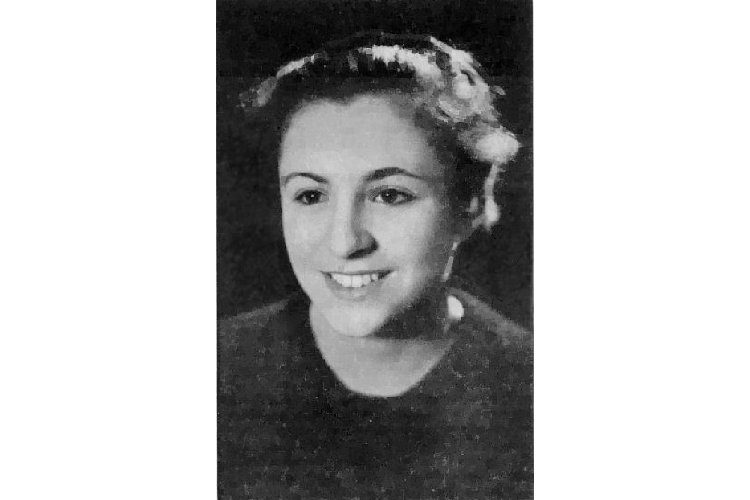

This brochure appears too soon after the sudden death of our friend and comrade Marie Louise Berneri to be complete, or even objective. When it will have been possible to collect her writings in a volume, to read her letters, and to recollect through her family and friends the incidents and details which make up the personality of an individual — then it will be possible to do justice to the very human being and comrade that Marie Louise has been to many of us in different parts of the world.

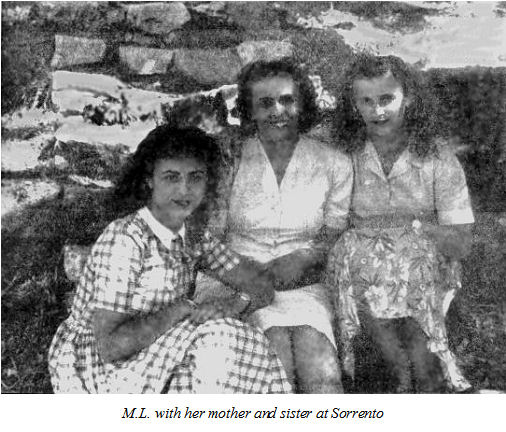

But this is a long task, and for this reason our Committee has compiled the present brochure, though we are painfully aware of its inadequacies. We feel, nevertheless, that the articles and the photographs will be welcomed by Marie Louise’s comrades and friends, and it will serve as an introduction to those who did not know her personally, or who were only vaguely aware of her name through her writings.

Marie Louise Berneri’s too short life can be divided broadly into three phases. The first, her childhood up to the age of 13, the second from 13 to 19, spent in Paris, and the third, the last twelve years of her life spent in this country.

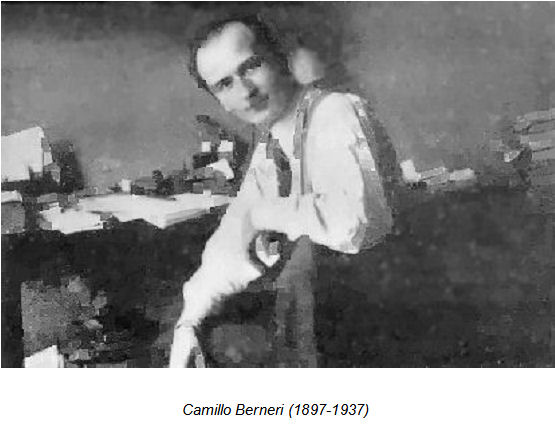

Of the first period nothing has been written in these pages. It is a contribution to the story of her life which will have to be made by those closest to her during that period — her family. And only when time has brought calm and serenity to them once again can we hope for recollections of M.L.’s childhood. And it must be written — for hers was an unusual childhood, a short childhood, if with that word one associates the carefree life of a child with its feeling of security and happiness provided by the parents and small circle of family and friends. Up to 1922 — that is, up to the age of four, Marie Louise’s life was spent with her family in Arezzo and in Florence. But that year saw the first police night raid on their house in the via Alessandro Volta, and the sight of her father Camillo Berneri being arrested by the police. It was the beginning of her family’s odyssey to escape the hatred and persecution of the fascist secret police.

At first their peregrinations were in Italy. The following is an extract from a letter from her mother, Giovanna Berneri: “...in November 1925 we arrived in Camerino, having already had to leave many other towns. On the occasion of the first attentat against Mussolini by Zaniboni, Camillo arrives home in haste, accompanied by one of his pupils. He is quite calm but his clothes and hat are in disorder. He had been confronted by a large group of fascists and beaten up, and they had followed him home. We hear their insolent songs in the street. We bolt the door and windows and with bated breath await events. Marie Louise is there with all of us. Neither she nor her sister cry; they are as outwardly calm as us. They are already two grown-up people ...” They are accustomed to such scenes. “They are present at searches, they listen to our conversations with friends and comrades as well as with casual acquaintances or people of whom we have doubts, and they understand how they have to behave and be careful when they speak. I cannot recall ever having to say to them: ‘You must not talk of this or that matter’ — and yet in these encounters with the police, the fascists, and neighbours (who were also fascists), they never committed a single indiscretion.” And in August 1926 came the escape over the frontier at Ventimiglia into France, by Giovanna and her two children. Marie Louise was then eight years old. They had no passports, no luggage.

The years that followed were hard for all political refugees in France. Difficulties with the police, the difficulty of finding work without identity papers. And in this atmosphere, hearing conversations in which arrests and deportations figured prominently, writing to their father in prison, and observing their mother’s struggle for survival — this was the “childhood” background of Marie Louise and her younger sister Giliane. In a letter to her father, written when she was twelve years old, she says:

“We had a picnic in the fields. As we were playing, I felt full of remorse for enjoying myself whilst you are in prison.”

Nearly twenty years later (November 1945), in her last letter to her companion before his release from prison, we find this paragraph, moving in its simplicity, re-evoking that turbulent childhood:

“...I like to dream I will travel, go to some warm climate. When I tell you about it I don’t want to be reminded about practical difficulties or ‘obligations’, there are too many of those things in everyday life. I will tell you something I never told you before, I think. One evening, it was before the war, we were walking home down Charlotte Street. It had been snowing and I felt suddenly very happy and I told you we would go to the winter sports together. You told me something about being extravagant and I suddenly felt very unhappy, my dream broken like a toy. Please don’t break my toys because I love them and need them. At Neill’s school they would say I haven’t lived my childhood through and they would be quite right. I didn’t have an unhappy childhood and I was less oppressed by the family than most children. But it wasn’t a carefree childhood. Grandmother used to tell me all her troubles and others I could see and feel all around me. I seemed to have ‘obligations’ from when I was very young, so now I like to be able to forget about them sometimes. I hope this does not sound too much like self-pity because you know I am fundamentally very pleased with life...”

The second phase of her life, from the age of 13 to 19 was a period in which one observed an ever-growing social consciousness and cultural and emotional development. This period saw an increased realisation of all the unhappiness of the life of the political refugee in France, a realisation of the brutality of the ruling class, with the frequent arrests, imprisonment, and deportation of her father in France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany, affecting her intimately. It was the period of the growth of that intellectual curiosity and keen critical sense which we were to witness later in all her work for the Freedom Press, and which distinguished her at school, at the university and in the anarchist group. It was the period both of great hope and disillusionment in the Spanish revolution of 1936, culminating for her in the brutal assassination of her father by Communist gunmen in the May risings in Barcelona in 1937.

The effect of her father’s death was the greater since she had been undergoing a strong influence of his ideas. Of this influence Giovanna Berneri writes: “I think that Camillo discovered his paternity in regard to Marie Louise, only during the last years of his life, and it is not by chance that his last message of 3–4 May should have been addressed to Marie Louise. She gathered that message, made it hers, and must have felt the immense joy of prolonging her father’s life in that way. But his tragic end marked her life ...” That last message is reproduced in this brochure. It reveals in the form of answers to questions Marie Louise put to her father, some of her problems and interests at that time. It also contains that noble ending which gives us an insight into the personality of Camillo Berneri. And to understand fully the character of Marie Louise, we will have to know more about her father, of his thought and his works.

In the present brochure there is only one contribution by a French comrade, S. Parane, who worked closely with Marie Louise during those years and who remained in correspondence with her to the end of her life. But there exist a considerable number of letters, (including more than 500 to her companion from which we have included three short extracts), a few articles, and many friends with recollections of that period.

The third phase, from September 1937, when she arrived in London, to her death on April 13, 1949, is a further development of the second period with the added responsibilities of an active role in the building up of an anarchist newspaper in this country, coupled with the practical burdens of running a publishing organisation. They were responsibilities to which she gave all her intelligence, originality and enthusiasm. And what success Freedom Press has had during these years is in a large measure due to her inspiration. The other landmarks of this period were for her, the arrival of the Spanish refugees in this country, the war period, culminating in her arrest with three other comrades, for sedition, and the preparation of her volume on Utopias, the research for which brought with it many ideas for further work. And, of course, in this period Marie Louise attained womanhood, with its joys and sorrows. (She could not always conceal the tragedy of her confinement at the beginning of 1949.)

The brochure deals with this third period at some length, including the Freedom Press Group’s appraisal of Marie Louise Berneri’s contribution to its work, a tribute by one of the Spanish refugees and by other comrades who worked with her. But the collection of her writings during this period will, as we have already pointed out, give a vivid picture of her thought, her vision, and the wide scope of her interests. We think it will also reveal the seriousness and thoroughness with which Marie Louise shouldered her responsibilities as an anarchist writer and revolutionary journalist. The volume on Utopias, A Journey Through Utopia, to be published in Spring 1950, her first full-scale work of research, will add to the reputation she had been gaining in the international anarchist movement as one of the most promising thinkers of the younger generation.

In perpetuating the name of Marie Louise Berneri, the Memorial Committee will avoid sentimentality and exaggeration. She was a human being with both the qualities and frailties of human beings. It is the person as we knew her, and not some saint of the imagination, which we wish to remember and about whom we wish that those who come after us shall know. As a person she emotionally enriched the lives of many; as a revolutionary writer she dealt with problems and topics that concern all who aspire to a richer and fuller life. Marie Louise Berneri achieved in her short life what we all at some time or other aspire to do: as well as taking something from society we seek to give something in return.

Marie Louise’s activities extended the effective life and influence of Camillo Berneri. May we not, as our tribute, attempt to fulfill the same function for her?

2. Letters (1936–1937)

From a French Comrade. S. Parane, Paris

In those difficult pre-war and war-time days, Marie Louise appeared as an element of stability, a symbol of equilibrium. Revolutionary circles seem to contain bewildered individuals who seek contentment by way of feverish activity in the bosom of social movements through the prodigal expenditure of energies which are not given play in the economic circumstances of daily life. It is probable that the difficulties of propaganda work, are to be explained precisely in the mistrust of the average man who, though easily reached by arguments, is jarred by the modes of expression, and the representatives, of extreme schools of thought by reason of their pathological characteristics.

By contrast, Marie Louise, in her calm and serenity, seemed detached from purely personal problems and free from subconscious motives, leading her individual life without letting it interfere with her theoretical, propagandist or social activities.

She grew up in an environment of political exiles, an atmosphere both dramatic and sordid, heavy with individual and social problems, divided by polemics, struck by the lightning blows of deportation and arrest. Her father wandering from country to country and yet managing to work for the movement, her mother had her hands full bringing up the children. Studies, meetings, visits from comrades and family friends, the work of earning the daily bread, papers to be circulated, correspondence to be dealt with, bills to pay, accounts to make up, solidarity to be given to comrades, contact to be kept up with the outside world. In this hectic atmosphere, rich with all sorts of human experience, Marie Louise grew from infancy to womanhood. Her soft, childlike voice, which she always retained, contrasting with her gracious womanly demeanour, evoked her continual exploration of things and people, with no problems that could not be solved, no contradictions that could not be unravelled by study, analysis and comprehension.

Throughout her life she retained this facility, the result of continual though seemingly effortless labour, for understanding people and events without hate or passion, without excluding her own likes and aversions, but putting them into their objective place. It is not possible to divide her life into its individual, family, public or social aspects. Hers was an integral, total existence.

When the Spanish Revolution came, when the barriers were down and the word-mongers were swept away by the tide of inescapable and burning realities, Marie Louise kept her eyes open. Like her father, she distinguished, with no illusions, between propaganda and actual achievements, she kept a human contact with the grandiose or pathetic efforts of a tortured people.

She joined a little group of French militants which published a short-lived review Revision, where systematically, even if, with a certain lack of documentation, these young libertarians endeavoured to surmount the crisis in the movement caused by the “governmentalism” which had been awakened in certain romantic anarchists by the technical problems which they faced. From this group, puzzled, uncertain and riddled with doubts, there emerged turncoats, romanticists, mystics, and some active revolutionaries. Marie Louise was in the latter category, linked with the militants of the working class syndicalist minority which was lucid but impotent and understood with only their little tracts and internationalist banners firmly held aloft to oppose it, that the prospect of war dominated the whole social horizon.

The War came, mobilising all the energies of those whom we sought to convince and frustrating all those whose activities were devoted to social progress, flinging them to the four winds of underground activity. Starting from scratch in England, Marie Louise, with her understanding strengthened by experience, attached herself to the reborn English anarchist movement.

Her first letters from London, were not enthusiastic — the situation did not permit any enthusiasm. In the development of libertarian movements the aftermaths of old feuds are very often serious obstacles. But Marie Louise’s physical and intellectual health was to prove that recovery was possible and that mental vitality was an effective weapon.

Throughout those years of exile, in situations where any acceptable future seemed remote, where military communiques took the place of news from the forgotten social front, Marie Louise’s letters, though even she was plunged into a dark battle against what the great majority of revolutionaries accepted as inevitable, these letters maintained one’s spirit in the struggle. Not by a ridiculous and unreasoning faith nor a struggle which is only a pose, but through a sense of realities, of perspectives, of tomorrows which are in the making and of which we might be the builders, alone among those others who blindly or consciously prepared for a future of new wars and revived hatreds.

In Mexico as in Egypt, in Chile as in Australia, were people, isolated, driven to despair by men and events, who found a solid support in those short messages which — in spite of the censor’s scissors and necessary precautions — led one to believe that the international anarchist movement was forcing its tiny roots into the hard soil of Britain. And Reuters despatches, interspersed with teleprinting errors and the regulation “stops” informed some of those who held fast, that the trial of the English anarchists for propaganda in the armed forces had begun and there were therefore still, as always, rebels and visionaries in the world.

Marie Louise, after her smiling and conscientious labours, her great compassion for those who suffer and who falter although everything is really so simple and logical, will, even in death remain for us a living example that the tragic farce of life is not overwhelming; that Man, with neither god nor master, returning to his origins of dust and ashes, can leave to his fellows a noble heritage so long as he has the calm determination to seek the truth ... and the courage to act upon it.

From a letter to her companion. Paris, 19th March, 1936 (in French)

“...Tuesday morning, instead of going to school, I ‘played truant’. You know, I had a good reason. I wanted to go to St. Anne (a mental hospital). Imagine, they were going to attempt to cure a hysterical woman. It is very rare nowadays to see hysterical paralysis (there’s one case every two or three years), so I absolutely had to go.

“I was rather affected by it. The patient was a young girl, of about my age, she often had crises of hysteria and one morning she became paralysed on the right side. She could barely move. The doctor made her lie on the couch and started the treatment which consists in activating the nervous system by electricity. It hurt me to see this girl contorting under the effect of the pain, and I was furious to see the young people laughing because she was half undressed ... However, after about half an hour she could move her arms and her legs and the doctor made her run and jump ... isn’t it wonderful? Unfortunately, the reason for this miracle cannot be explained. The young girl was not ill from an organic point of view, and a strong emotion permitted her to move her limbs once more ...

“I have been to a meeting of a group started by some anti-fascist students. It isn’t very interesting, but it is so rare that such an initiative is taken, that one should support it. I had a long discussion with some communists who profess to be pacifists but are ready to march against Hitler. I had a whole group opposed to me, but I think I discussed well in spite of that. When I say ‘well’, I mean that I did my best, for I fully realised that every minute I lacked precision and information, and further, lacked that ‘advantage’ of being able to quote Marx, Lenin, or Stalin at every turn ...”

To her companion. Paris, 4th October, 1936 (in Italian)

“...Two important events have occurred: firstly, Mother has returned from Spain, and secondly, I have succeeded in finding someone who wants lessons. Further, I have been rather worried these past few days because G. told Me that Father would like to have me with him, and so my idea of going to Spain obsessed me and at night I could not sleep thinking that here I was, taking things quietly, without trying to do anything. Well, we have agreed with G. that if there is a mission of confidence to be carried out, he will send me. I have a passport so I don’t risk being arrested, and I can reach Barcelona much more quickly. But I won’t stay there, because from what Mother tells me, I can’t be of use.

“I am so pleased to have found these lessons, five hours a week of cramming for a girl of_ eleven, for which I will receive 200 francs a month ...

“Mother has brought back from Spain an article by my father which is an appeal to intellectuals in all countries to prevent fascism from triumphing in Spain. I translated it into French this afternoon and tomorrow will try to place it with one or two newspapers.

“I have also written a short appeal to doctors and hope to send it to the Libertaire. Imagine, they are so short of medical men that they are obliged to keep on the fascist doctors. Tomorrow I shall go and see a Doctor R. who will be able to give me more exact information. By the way, I forgot to tell you that that nurse has accepted with enthusiasm the idea of giving us a course in nursing.

“Forgive me, my dear, for having written three pages which have little to do with our love, but I so long to have you near me to talk of these things, to ask your advice and to do something together. I was saying to G. this morning, you are really a comrade to me, you are the person with whom I will always carry on the struggle, who will help me and whom I will always try to help.

“At present my heart is so perturbed by what is happening in Spain that I cannot feel like thinking of happy days of loving. I don’t know whether you will understand, my dear, because, though deeply affected by Spain, you are not living in the atmosphere that exists here. It is the only topic of conversation; then there are the comrades I see who have been there, and Mother speaks of nothing else since her return. I was so hoping that she would come back full of optimism. Instead she cried on the journey back, and I found her very discouraged...”

A letter from her father

The letter reproduced below was written in Barcelona by Camillo Berneri to his daughter Marie Louise on the night of 3–4 May, 1937.

A few hours later, Camillo Berneri was arrested by men wearing red armlets.

The following day, Camillo Berneri’s body, riddled by machine-gun bullets, was picked up in the Rambla by members of the Red Cross.

“I don’t think one should worry too much because various anarchists express different tendencies on a tactical problem such as whether preference should be given to the C.G.T. or the C.G.T.S.R. [the French Trade Union and Revolutionary syndicalist organisations respectively]. The only advice one need give is to beg the speakers to bear in mind that, far from discussing the matter amongst themselves, they are arguing in the presence of people who must be won over to the movement and its ideas. If they show tact and common sense, all will be well. You’ll never find two representatives of the movement who see things in the same light: all you do is to think things out for yourself. Of course, one must be acquainted with anarchist thought in its most important doctrinal formulations; there are some authors, Proudhon, for instance, who pack more ideas in a chapter than F. could produce in ten years; the argument that theories must conform to facts and derive from them is both true and false; it all depends on the manner and the extent to which it is applied.

“The evolution of humanity towards sympathy is a basic concept in socialist anarchism. Kropotkin was not exaggerating when he drew on the natural sciences for examples which prove very little inasmuch as they are connected with eminently biological instincts, rather than with sentiments in the true meaning of the word. He often confused a semi-organic herd instinct with conscious solidarity. His Ethics show an advance, but just the same the concept of solidarity remains in his exposition somewhat ingenuous.

“I too consider that the criminal exists as a pathological phenomenon and not as a human type (as a moral species) but I have the impression anarchists tend to over-simplify the problem enormously and arbitrarily. I intend dealing with this subject and you must give me your opinion.

“As you know, I am collecting material on industrial psychology. We’re planning an “Anarchist University” (no less) and I may prepare a course of lectures on this subject about which I know something having attended at the Centre for Experimental Psychology in Florence. I’m pretty well acquainted with the main types of apparatus and also, broadly speaking, with the methods used in such research.

“A Marxist is a follower of the central doctrines of Marx; a Marxist too is he who considers Marx as having condensed, systematised and renewed ideas in the field of sociology, thus giving socialism a truly scientific character, finally, a Marxist is a person who considers himself such, in other words, who is aware of the affinities between his own thinking (or rather in the general trend of his thoughts) and that of Marx.

“My dear Maria Luisa, don’t be humiliated because your ideas are not very clear on all this (and how much of this there is). The trouble is one can’t be clear about it; as long as you realise you don’t know and are afraid you don’t understand, there’s nothing to worry about. It shows one isn’t a fool. On the other hand, you’ll come to realise many things were not understood because there was nothing to understand and that others were not worth understanding.

“I wish I could be near you in your formative years. What a fine cultural union that would make. I wish I could impart to you all I am surely aware of: not very much, but the fruit of forty years of life, strengthened by a certain critical sense and an unflagging curiosity.

“Tonight all is quiet and I hope the crisis will be solved without further conflict. Here too, how much harm the Communists are doing! It’s getting on for two o’clock and I’m turning in. Tonight the house is on the ‘qui vive’. I have volunteered to stay up so that the others could get some sleep; they all laughed and said I wouldn’t even hear the guns, but afterwards, one by one, they went off to bed and I am watching over all of them, working for those who will follow. This is the only thing which is wholly fine. More absolute than love, more true than reality itself, What would man be without this sense of duty, without being moved at the thought of his oneness with those who have been, with the unknown men of the past and with those who are to come? There are times when I think this messianic feeling is nothing more than a form of escape, a seeking and a striving for equilibrium and order, which, were it lacking, would plunge us into confusion and despair. Be that as it may, it is certain that the most intense feelings are the most human.

“One can lose one’s illusions about everyone and everything, but not about what is affirmed by conscience. If it were possible for me to save Bilbao with my life, I would not hesitate a moment. No one can deprive me of this conviction, not even the most captious of philosophers. And this is enough for me to feel a man, to console me whenever I am unworthy of myself, of the esteem of my finest comrades, of the love of those whom I most value and cherish.

“Whenever conscience is involved, reason leads me to no decision. The ultima ratio, what really decides the issue, is style: this is not my style — for me that is the last word.

“The solemnity of what I have written above must sound faintly ridiculous to anyone not living here. But some day perhaps, if I can speak to you of these months, you will understand.”

After her Father’s Death

(From a letter to her companion. Paris, 16th August, 1937, in Italian).

“How many things there are to be done. And here I am, unable to escape from this sort of “engourdissement”. At bottom I believe I don’t want to escape because I should feel even more, the pain of my father’s death, and of all that is happening. So I try not to think. It is not a very courageous stand. I should face up to everything, but really I haven’t the courage. A veil has been drawn over my life. I hope that when we are together again I shall succeed in tearing it away. My dear, I so much want to bring much more strength and light into your life.”

3. Her Contribution to Freedom Press

Freedom Press Group

At the time of her death, when she was 31, Marie Louise Berneri had already won for herself’ a high place among present-day theoreticians of the anarchist movement, and exerted an influence usually attained only by much older comrades.

This influence was the product not only of her mastery of a number of subjects, but also of her exceptional personal qualities, which lent to her writings, her public speaking and her private conversation a special distinction that drew immediate attention. These qualities caused her opinions to be regarded with respect also in circles which do not share her social and political views. Her personal beauty reflected her serene and generous nature, and made her an outstanding figure at any gathering.

Her loss to the anarchist movement cannot be measured, for it is not simply that of an outstanding militant; lost also is all that she would have accomplished in the future, in the growing maturity of her powers. And the world in general is also the poorer, for such rare and exceptional individuals enrich human life and make of the world a better place.

M.L.B.’s character and personality had a compelling effect upon those who came in contact with her, communicating a confidence in human nature and in life simply by her bearing and her approach to problems. She herself was quite unconscious of this, for the modesty which was so natural to her always made her underestimate her own influence over others.

This influence was not limited to the circles reached by Freedom and its predecessors. Many writers and intellectuals — for example, those who met her through a common interest in the problems of the Spanish struggle — found themselves profoundly stimulated by her ideas, her exceptional powers in discussion, and her vitality. M.L.B. was not content to confine herself to the literary work of anarchist publishing, being quite unsparing of herself in the routine work of the movement — office work, correspondence, street selling, contacting potential sympathisers, lecturing to the movement’s meetings and to outside organizations. She was at the centre of all_ the manifold activities which go to make up a movement’s life. Her general grasp of international affairs was informed by a profound internationalism of feeling, her sympathies being with the oppressed peoples of the world, and she was utterly incapable of that narrowness of outlook that is called patriotism.

Marie Louise Berneri was a member of a distinguished anarchist family which has influenced the movement directly in Italy, Spain, France and the English-speaking countries. Her father, Camillo Berneri, was a leading theoretician of the Italian movement and an outstandingly original thinker. He was assassinated by the Communists during their counter-revolutionary putsch in Barcelona during the May Days of 1937, when at the height of his powers. Her mother and sister are prominent in the movements in Italy and France respectively.

Born at Arezzo in 1918, she went in early childhood into exile from Italy when her father refused to accept the demands laid upon the teaching profession by the Fascists. In 1936 immediately after the outbreak of the Spanish Revolution her father went to Spain. After a short period of active fighting on the Aragon front he took up residence in Barcelona in order to edit the paper Guerra di Classe, the most far-seeing and clear-sighted revolutionary anarchist paper to come out of the Spanish revolution. Marie Louise Berneri went to Barcelona for a short visit in the autumn of 1936, and kept up a close correspondence with her father. After his death she came to live in England.

Her interests were not confined to general political matters. Although her university studies in psychology were interrupted by her departure for England, she remained a keen observer of human individuals and their motives, among her special interests being child psychology. And, as always, her great qualities informed her discussion of them. When she spoke on Reich’s work and the sexuality of children to an Easter Conference of the Progressive League some years ago, many of her hearers spoke afterwards of the remarkable impression this young and beautiful woman made by her calm and penetrating discussion of matters which the majority even of intellectuals fear to think about. And all this with a charm and level-headedness which disarmed hostile criticism.

Throughout the war she was continually beset with anxiety for friends and relatives in occupied territories, some of them in fascist prisons and concentration camps. Only those who were closest to her understood the depth of feeling which lay behind her serene bearing. With the same courage she bore tragedy in her own life.

M.L.B. was an inspiring and greatly loved comrade. But for the present we must leave more personal accounts to others and concern ourselves with her work as a militant in the anarchist movement. Her spirit infused every activity undertaken by the Freedom Press since 1936. Her influence was ubiquitous, and her personality coloured all our work. Here we can only try to speak of her contribution in general terms.

Her work for the anarchist movement in Britain began before she came to live here. Before the first issue of Spain and the World came out in December, 1936, she had discussed every aspect of its launching with her companion and her father, had collected funds to cover the first five issues, and had made the necessary contacts among comrades able to send information and articles. After 1937, when she came to live in London, she took an active part in the production of each issue, even down to dispatching and street selling. She always retained a delight in seeing the whole production through from start to finish, and in 1945, writes to her companion, then in prison: “I am writing from the Press as I am waiting for the second forme to go on the machine. I like being here, rushing up and down, seeing the paper take shape. I think this issue is good and more lively than the last one ...”

As well as the editorial work for Spain and the World, there was the Spain and the World colony of orphan children at Llansa, in Gerona. For these 20 children, later increased to 40, she collected funds and clothing. Manuel Salgado speaks in another article of her work for the Spanish comrades who came to Britain after the collapse of Madrid in 1939. Later on, in 1945, when over a hundred Spaniards who had spent the war in the German forced labour brigades in France, were brought to England and treated as enemy prisoners-of war, she not only visited them and organized relief parcels for them, but effectively brought their condition and the injustice of their detention to the knowledge of circles in a position to exert pressure on the government. In due course, and, in no small measure as a result of her work on their behalf, they were released either to stay in this country or to go back to France.

When Spain was finally crushed by Franco’s victory, disillusionment and the imminence of another world war reduced support for Revolt! (as Spain and the World had been renamed) and the paper ceased publication after June 3rd, 1939. Many comrades and former supporters seemed to disappear, but M.L.B. was always seeking ways and means to start a new paper, and a small group of comrades issued the first issue of War Commentary in November of the same year.

It is not easy to recapture the spirit of those days of gloom and despondency. The complete destruction of the hopes raised in 1936 was enough to extinguish the enthusiasm of most of the comrades; but for M.L.B., although her emotional commitment to the cause of the Spanish Revolution was of the deepest, the situation simply called for the continuation of the work of the movement in the changed circumstances. It was not that her temperament was particularly optimistic, though she was buoyant enough; her resolution in continuing to give expression to the ideals of anarchism sprang from a certain steadfastness, a quality which was like a sheet-anchor to her comrades in critical times.

The full command of language she achieved later also made it easy to forget that in those early days she possessed only an imperfect knowledge of English. Yet in the summer of 1940 she conducted the most exhaustive discussions with two English comrades on the history of the Spanish Revolution, and the fruits of this discussion were then embodied in a course of ten lectures given to a small study circle first at Enfield and later in central London. Though the numbers of sympathisers who attended these lectures were small, yet she spared no pains in preparing the material. The anarchist movement had to be built up again, and she went to work wherever the smallest opening showed itself. Later on, in 1941, when the shop in Red Lion Passage had been destroyed by fire, and the Freedom Press offices moved to 27, Belsize Road, she initiated the weekly lectures which have continued almost without interruption ever since. In the discussions which followed these lectures her contribution would always make sure that the specifically anarchist attitude to the subject was fully displayed, and she would unerringly put her finger on the fundamental questions.

She was never satisfied, nevertheless, with presenting a “party line”, but always adopted an independent and critical attitude. This is well shown in an editorial article in Revolt! of 25th March, 1939, which was jointly signed by herself and V.R. It discussed the reports in the Spanish anarchist press on the events in Central Spain when the Communists were finally eliminated from the government. M.L.B. and V.R. could not regard this as a triumph, for it came too late; the Communists should have been rendered powerless two years before, during the May Days in Barcelona in 1937.

“Thus, viewed in this light,” they wrote, “we cannot consider the final elimination of the Communists as a victory for our comrades. Rather must we admit that their whole attitude (the C.N.T. more than the F.A.I.) in refusing to make public in Spain and the world at large the nefarious work being carried on by the Communists and other counter-revolutionary elements in general, for fear of breaking up the anti-fascist front, was a serious tactical mistake, partly responsible for the tragic situation in Spain.”

M.L. applied her critical intelligence not merely to events in which the international anarchist movement played a part, but also to the work of our own group and to herself as well.

The following extract is taken from a letter written in 1941 to a comrade who was an outstandingly able outdoor speaker. It shows M.L.B.’s fairness and objectivity, and her sense of purpose; but here we are concerned to stress the frankness of her critical approach.

“We are not going to build up a movement on obscure ideas. We shall have fewer ideas perhaps, but each of us will understand them perfectly and be able to explain them to others.

“In order to defend your position you take the example of Bakunin, Emma Goldman, Malatesta — all mystics according to you. But take the example of Malatesta ... Have you ever read his Talk Between Two Workers or other dialogues? They are luminously clear. He explains anarchism without mixing it with 19th century philosophy, God, Faith or Knowledge. He knew that if he started introducing metaphysical discussions the workers would not have understood him. No doubt he desired some time to write about these problems, but he had the courage to mutilate his knowledge in order to be understood by the masses. The same applies to Kropotkin. He could have written books bigger than those of Marx around his theories but he had the courage to write penny pamphlets expressing his ideas in the most bare and simple form. He says himself somewhere that he needed a lot of courage to do that work, he envied the Marxist and bourgeois theoreticians who were not limited by those considerations in their work. But at least he succeeded in being understood by the most illiterate workers and peasants.

“You, comrade, want to put all your knowledge, all the ideas you have and all the original thoughts which come into your head in your speeches and articles. You have not learned the modesty, the spirit of sacrifice which must animate the propagandist. We must go to the people ... but do you believe that the nihilists went to the people with the ideas they had just taken from the books of Hegel? You must go to the people with simple, clear ideas. You refuse to make that sacrifice, you think it would mutilate you, you do not see it would make you stronger and more efficient.”

This extract also illustrates M.L.B.’s views on the form in which mass propaganda should be cast — views straight-forward enough, indeed, but a glance at progressive propaganda will show how often simplicity is forgotten. It should not, however, be inferred that she advised any kind of vulgarization of ideas for mass consumption. Indeed, the whole spirit of the above letter implies the opposite — the need to express ideas simply instead of in a recondite manner. This is very different from mere sloganizing.

Her spirit of mutual criticism combined with mutual respect helped to develop to the full both the individual qualities of each member of the group, and also the ability to work together in common with complete identification of the individual with the aims of the group. Glancing through the files of War Commentary, one is struck by the number of articles to which it is impossible to assign a particular authorship. They were produced after joint discussion, a comrade being delegated to prepare the final script. M.L.’s work extends far beyond the articles over her initials, for she provided an inexhaustible fund of ideas, enriching and fructifying the writing of many comrades on the editorial board. Her hand is thus present in many an unsigned editorial or anarchist commentary. It says much for her influence that our group has developed and worked with such complete harmony and integration.

Since 1936 it has been necessary to build up the anarchist movement in Britain again from the beginning, and the method of building up has therefore borne the imprint of M.L.’s organisational ideas. She hoped eventually to see a numerically strong movement; but she also knew well that weakness is concealed in mere numbers without a clear grasp of anarchist conceptions or resolute character. For M.L.B. the term “comrade” did not simply mean one who shared the intellectual conceptions of anarchism: it meant someone who also commands respect as a man or woman, who is devoted not merely to the ideas but to the cause of anarchism, and expressed that devotion in work for the movement. For her, the term “comrade’ was also a compliment and a mark of friendship.

It follows from such conceptions that a movement could only be built up by working in common, by the development of mutual respect and trust. Nothing distressed M.L. more than a failure to maintain this trustfulness between comrades in the movement, for she saw in mere mechanical relationships the seeds of dissension and future weakness which become manifest at just those critical moments when steadfastness and solidarity are most needed. Such a method of building a movement must inevitably be slow; but it creates a solid and enduring structure. It requires laborious propaganda and unremitting work: and it must be able to survive innumerable disappointments, for many are tried in the balance and found wanting. But it derives solace from the good comrades who are gained for the cause of anarchism; and strength from the friendship and comradeship born of common struggle. The tributes to her in this brochure bear abundant testimony to that.

M.L. provided for the rest of us (and indeed for all whose contact with her was more than superficial) the soundest foundation for the movement in her love for the anarchist ideal and philosophy. How moving are these lines about the Russian anarchist, Voline, who died a few months after they were written (May 24, 1945): “Last night when I came home I found a letter from Voline. He had been gravely ill and was writing from hospital. He described to me the work he had to do and the sufferings he had gone through and I felt sad after reading his letter, sad and ashamed too because during the day I felt a bit fed up and started thinking I should enjoy myself instead of working (you know the mood one gets into sometimes) and then I get Voline’s letter and I see that, in spite of all the privations he has endured, his first thought is to get better and to go out to carry on with his good work.”

Throughout the war, whether she was in the editorial chair or had temporarily relinquished it to other comrades, she was the principal theoretical influence behind War Commentary, and afterwards Freedom. (And to say this is by no means to belittle the work of other comrades.) In 1945, she was one of the four anarchists associated with War Commentary who were arrested and charged with sedition. In the event, she was acquitted on a technical point of law, and did not go into the witness box. But she had wished to defend herself, and only agreed to this more passive role on the insistence of comrades. They pointed out that it would be madness for all the defendants to go to prison when technical grounds would free her. With George Woodcock, she was more than equal to carrying the main burden of continuing the paper until her comrades were released from prison.

To her work for the paper she brought a wide knowledge and insight into affairs, while her visits to Spain and her long and deep concern for the problems of the Spanish Revolution had given to her revolutionary views an actual and practical quality which was of immense service to editorial discussions. Her sense of humour — and of scorn — is revealed in the excerpts from the capitalist (and often, too, from the radical) press which for five years she collected as a regular feature in “Through the Press.” As an editor she always insisted on high standards — not always easy to attain in a struggling minority paper. On many occasions she would herself sit up through half the night preparing material for publication rather than take the easier course of passing inferior articles which were to hand.

In addition, she maintained an extensive correspondence with comrades in Europe, Mexico and South America, throughout the war; and this she extended greatly in the post-war period.

It is natural that we should look for those aspects of M.L.B. and her work which, besides the image that her friends will always carry, will survive. Of her writings, the most important is her Journey Through Utopia which is shortly to be published, and which illustrates her thorough and comprehensive approach.

We are fortunate in having this work, written in the last year of her life, during the calm of her pregnancy, when the beauty of her character, and her face, seemed enhanced by her sense of biological fulfillment. She did not regret those months even after their tragic sequel (for her baby was born dead) and nor should we.

She was the author of what is probably the most influential of recent Freedom Press publications, Workers in Stalin’s Russia, published at a time when it was not yet a popular role to expose the Russian system, and which ran to two printings, totalling ten thousand copies. It is not a political book in the ordinary sense, but an attempt to sift out from the mass of conflicting and often suspect evidence, the truth about the situation of the Russian people, and to assess it from the standpoint of human values. Always an indefatigable student of Russia, she brought to her study exceptional intellectual integrity and penetration, and the book amply illustrates her humane and ethical outlook. As with her knowledge of Spain, she kept a strictly critical standpoint, and never permitted the demands of propaganda to warp her judgment. This quality lends a special authority to her work. As she said in her introduction:

“The destruction of a mirage is an unpopular task. The man in a desert who is trying to convince his exhausted companion that the coveted oasis he sees in the distance is only a dream is likely to be answered with curses ...

“But if the illusions about the happiness of the Russian people must be crushed, the belief in the need and the right to happiness and justice for mankind must remain.”

The greater part of her written work is to be found in the innumerable articles, editorials and reviews, and in her articles in the foreign press and letters abroad. This work may have been hasty, or fragmentary, but was never superficial. Her knowledge and her integral conception of anarchism prevented that, and she brought the same qualities of generosity and sincerity, which gave her such charm as a person, to her work as a revolutionary journalist. It is as impossible to conceive of her indulging in polemical exaggerations or substituting slogans for reasoning as it is to think of her displaying a lack of honesty in her personal relationship.

Her attributes as a writer are typified in two essays in the magazine Now. They take the form of reviews of Reich’s The Function of the Orgasm and Brenan’s The Spanish Labyrinth, but she contributed so much of herself to her book reviews that they stand in their own right. Her long discussion of Reich’s work, the earliest appreciation it received in this country, ends thus:

“...To the sophisticated, to the lover of psycho-analytic subtleties, his clarity, his common sense, his direct approach may appear too simple. To those who do not seek intellectual exercise, but means of saving mankind from the destruction it seems to be approaching, this book will be an individual source of help and encouragement. To anarchists the fundamental belief in human nature, in complete freedom from the authority of the family, the Church and the State will be familiar, but the scientific arguments put forward to back this belief will form an indispensable addition to their theoretical knowledge.”

Around her examination of Brenan’s book she wove a picture of the history and struggles of the Spanish people which is full of human feeling and understanding. She disagreed with the author’s conclusions but she summed up his work in these words:

“Brenan, who lived so long in Spain, seems to have been influenced by its communal institutions, and has written his book in the spirit of the craftsmen of the Middle Ages. Like them he has produced his chef-d’oeuvre which is the test of his love for his art and his respect for his fellow men for whom the book is written. The Spanish Labyrinth has been created with that painstaking and disinterested love which characterises all lasting works.”

The qualities she admired in this work are strikingly revealed in her own writings.

During the last few months of her life she had projected a book on the unpublished writings of Sacco and Vanzetti, which she had hoped to issue both in England and America, and also in Italian. She had, too, begun work together with George Woodcock on the translation of Bakunin, and was preparing for publication her father’s notes on sexual questions. She had also started to collect material for a study of the Marquis de Sade.

The conflict between the desire to express one’s own potentialities and the urge to play a part in effecting social change is neither so simply nor so inevitably concluded as is sometimes suggested. For the apathetic or for the narrowly fanatical it does not exist, but for these who, like Marie Louise are so richly endowed by nature and by parentage, it may present a terrible dilemma. There are some who, while accepting much from our common heritage, offer so little to it, and some who, in their devotion to causes, have extinguished themselves. It may be argued either that he who develops his own attributes to the full, regardless of the world in which he lives, has by that very act enriched society, or on the other hand, that he “that loseth his life shall find it”, but neither of these is wholly true. The ultimate dissatisfaction of the ruthless individualist and the frustration of the completely selfless propagandist spring from the same root — the inability to balance the needs of the person as such, and as a member of society. Marie Louise was able to achieve this balance. Her serenity and repose were the outward signs of this inner poise. She was not unconscious of the struggle between the continual demands of the movement with which she was so closely associated, and the need for creative self-expression, a need that in a nature like hers must have been very strong, but her life was a witness to the success with which she resolved this conflict.

For her friends and comrades the sense of loss is overwhelming. It is impossible to convey an adequate impression of her influence on the intellectual and personal development of the members of the Freedom Press Group, and there are many others who owe her a similar debt that can never be repaid. We are conscious of the inadequacy of these cold lines to convey an impression of the part M.L.B. played in our group’s life. Yet her warm, vivid and truthful personality remains as a part of each one of us.

From a Spanish Refugee. Manuel Salgado, London

What I was reading seemed unbelievable. I re-read it many times to convince myself that it was true. In a few lines, full of suffering, her companion informed me of the sad news. The reading of the letter left me prostrate; what I had just read seemed unbelievable.

I knew Marie Louise Berneri in the year 1939, a year of sad memories for the Spanish revolutionaries and for libertarian ideas throughout the world, for in that year the torch had been dimmed that since 1936 had lighted up Spain. On April 4th, a group of us, mainly from the central zone of Spain, arrived in this country. We were morally and physically destroyed. To relate the vicissitudes of our journey would be long and out of place. Within a few days a comrade, whose name I forget, came to take us to the Freedom Press group’s premises at 21, Frith Street, and it was there that I first saw Marie Louise who received us with unbounded happiness. She appeared even younger than her years (and she was very young) and to her one applied that eulogy made by Angel Samblacat many years ago in España Nueva of our great fighter, Libertad Rodefias, when he called her “the pale virgin of the red rite”. That was apparent to us from the first moment at seeing with what devotion — for that is the word — most of the comrades there listened to her.

From the very beginning she was at our disposal, and moved heaven and earth so that those of us who were still at the Salvation Army hostel should leave that place, and in fact, a number of us went to live at Frith Street.

The group to which she and her companion belonged, edited the fortnightly paper Spain and the World, in the columns of which she defended our cause with enthusiasm. From the first day of our change of abode she became our interpreter and constant companion in our long walks through the streets of London. All her interest was centred on our explaining in detail the ins and outs of our struggle and why many of our problems were solved in a particular way which often she could not understand. She found it difficult, for instance, to comprehend the reasons of our acceptance of militarization, a measure which meant the acceptance of a discipline and a class differentiation which in the long run would corrupt the revolutionary feeling which our army had to maintain in order to achieve the realisation of our ideals. She wanted to learn in detail all about Collectivisation, which seemed to her to be our most revolutionary achievement. She also wanted a full explanation of all that happened so as to make deductions and draw conclusions. We tried to do all this and to convince her of the absolute necessity of accepting a number of measures. We were, however, hardly ever in agreement in our interpretation of events, but she was full of that tolerance which must be a basic principle for whoever calls himself an anarchist; she listened with a smile on her lips and tried to convince us of what she called our heresies against anarchist ideas. And all this she did without recourse to violent language.

There was an episode in our war about which she asked no questions, and about which all of us, without previous arrangement among ourselves, kept silent. I refer to the incidents in May, 1937, which were provoked by the communists and during which the lackeys of Moscow assassinated her father, the dear comrade Camillo Berneri. We knew how painful it would be for her to speak of this period and we always avoided it, and she appreciated our silence.

Though not completely sharing our point of view, she helped us within the limits of her strength and encouraged us in the campaign our group launched against our detractors in France. But all this was not enough for her, since she realised that this would in no way benefit our ideal, and she pressed us to do something more effective on behalf of those who had remained in Franco’s jails, and something more positive, but to do this someone would have to go to Spain to make contact with the comrades. This was an undertaking full of risks, but Marie Louise, without hesitating one moment, offered herself to act as liaison with the comrades over there. We had a great struggle to dissuade her and to make her understand that both her name and that of her companion were too well known to the Italian police, and that she was bound to end up in prison, and that would be a useless sacrifice. She gave in only when she had been able to arrange with a close friend of hers, without political affiliations and therefore with more chances of success, to make the journey. And in fact this plan succeeded.

Meanwhile, the world war broke out and once more she put to the test her anarchist convictions; from the very beginning she declared herself against the war and she worked indefatigably in every way that might forward the ideals of anarchism and without considering the risks involved. We tried to convince her that though war was a bad thing it would have the positive value of destroying world fascism. She was indignant when she heard such reasoning and only excused it because of our position as exiles who thought that an allied victory would make it possible for us to return to our people.

It only remains for me to ask the comrades who shared with her those days of struggle, not to mourn for her, but to follow her example. For that will be the best memory we shall retain of Marie Louise Berneri, of our Mari-Luisa.

A Visit to Glasgow (1945, letter to her companion in prison)

June 22, 1945

“I returned yesterday from Glasgow and felt like writing to you straight away to tell you all about my trip. In my last letter I told you that I felt a bit nervous about going up there but all my fears were unjustified. I think the visit was a success and it certainly gave me a lot of encouragement. What stands out most is the friendliness of our comrades which was really wonderful. They did not want to let me go and Jimmy used all kinds of philosophical arguments to prove to me that if I were free, if I believed in our ideals, etc., I would not worry about going back to work but would stay up there for a while ...

“I had the chance during this visit of seeing some of the surroundings which I had never seen before. One Sunday morning we went to Clydebank.

“I never imagined it could be beautiful. I thought it would be drab, smoky and black; instead the shipyards and factories are surrounded by green patches, the cranes look beautiful against the sky and the ships as usual filled me with joy and the desire to go away, far away. On one side of the road (or boulevard as they call it here, pronouncing the word in an indescribable way) are the factories and shipyards; on the other, the country with beautiful trees, hills and rocks dotted with cows and horses grazing. It is strange to see industry and the country so close together, in fact only separated by the width of a road.

“After our walk, during which we sang Wobbly songs, we all went to lunch at Jessie’s house ... From there we went to Maxwell Street where Eddie and Jimmy are now holding meetings on Sundays. It is a new pitch but in spite of that there was a big crowd which became bigger and bigger until it reached the tramway lines ... But I was quite nervous thinking of the meeting in the evening particularly as the comrades told me that they did not expect a too well attended meeting as there were several rival ones at the same time, including an Anglo-Soviet friendship rally with the Glasgow Orpheus Choir as chief attraction. However, there was no need to have worried, for the meeting was well attended. In fact there were practically as many people as at the previous one even though we had no “names” among the speakers.... After the meeting we met all the comrades together and had a discussion till about 2 in the morning (they never seem to go to bed in Glasgow). Parts of the discussion were a bit unpleasant as they revealed fundamental differences in outlook, but on the whole the atmosphere was friendly and the conclusion arrived at was that although we differed on certain points there was no reason why we should not be working together.

“On Monday morning we went to an open air meeting and they persuaded me to speak. As you know, I have never done outdoor speaking before, and it was rather strange. When I think of it I wonder how I was able to get on that little stool and talk at all. They all told me that I had done very well, but the comrades are so kind that I don’t know whether there is any truth in it. However, they asked me to talk at another open air meeting the next day and like a good girl I did! The only pleasant thing about speaking is that you feel terribly relieved when you have finished; it’s like passing examinations except that you don’t have to wait for the results.

“Another high spot of the trip was a visit to Edinburgh, which is a lovely city. We had fun hitch-hiking there and back and I shall never forget the view of the Castle which dominates the city and gives it a continental air unlike any other town I have seen in Britain. Compared with Glasgow, Edinburgh is obviously a bourgeois town yet a few yards from the Castle are terrible slums, not the ordinary small, miserable looking houses one sees in the East End of London or in mining districts but very old high stone houses which must have been built centuries ago. They reminded me of the slums in Naples. I wish one could obtain good photographs of them to illustrate John’s pamphlet on Ill-Health.

“The next day we went to Loch Lomond which is really wonderful. But I am no good at descriptions. We must go there together, that’s all! ...”

A Tribute from George Woodcock (writing from Vancouver)

Like all who knew her intimately, as a friend and a comrade, I was grieved beyond description to hear, belatedly and in a distant country, of the death of Marie Louise Berneri.

I first met her in the old Freedom Bookshop in Red Lion Passage, in the early days of 1941. At the time I was a somewhat vague libertarian, with the flimsiest of anarchist ideas. I had become interested in anarchism during the Spanish civil war, had read Kropotkin and Read, and, when the war came, found that resistance to it led me naturally and logically into a full rejection of the state and its authority. But up to this time my evolution had been personal and I had only just become aware of the existence of a group of people who were concerned with the propagation of libertarian ideas.

I remember on this first occasion being impressed in more than one way by Marie Louise. Her beauty, seen for the first time, was almost startlingly impressive; later one found it so natural a part of her whole personality that one tended to take it for granted, though never to become unaware of it, for though her beauty became more mature as she grew older, it changed rather than diminished, and was always irradiated by the vitality of her character. Her manner on this first meeting was earnest, rather solemn, and a little shy, though she expressed her opinions with a very uncompromising candour. Her English at that time was still imperfect, and the strong and pleasant French accent was more pronounced than in later years. With her earnestness, there was evident also a certain youthfulness in her manner, which later became more manifest when one saw the lighter sides of her nature; it was a manifestation of simplicity rather than of juvenility.

I was much impressed at the time by the acute intelligence with which Marie Louise discussed the general theoretical questions I raised, and later in the same year, on returning to London from the country, I re-established contact with her and with the Freedom Press Group now, since the air raid which destroyed the Red Lion Passage shop, installed at Belsize Road. During the subsequent months of discussion and work together my ideas became clarified, and the direction of my development as a writer was determined in those days by the intellectual influence of Marie Louise more than that of any other individual. If I have contributed anything of significance to anarchist thought or writing, it has been due mostly to her.

I know that in saying this I should incur her displeasure, for despite or perhaps because of her intelligence and the rare honesty and directness of her thought, Marie Louise was a person of extreme modesty about her own qualities, and tended to under-estimate the influence she wielded in giving form and strength to the ideas of many people who encountered her personally.

For more than six years I worked with her in close collaboration on work connected with Freedom Press and on other literary endeavours. I have never met elsewhere, and I cannot hope to meet again, a person with whom it was so easy or pleasant to work, for her intellectual clarity and her high sense of reality were invaluable in the intellectually perilous work of editing a paper devoted to social propaganda. Nobody could assess more clearly the essential nature of a political situation or resolve more thoroughly and honestly one’s doubts. She was always ready with ideas, and had a true journalistic flair for following the news of the day- and grasping its socially important points. Many of the articles we published during our periods of work together were the result of a very harmonious co-operation. For editorials particularly, the basic idea more often than not came from Marie Louise. We would work out a skeleton plan together, on which I would immediately type an article, which we would then amend until it seemed completely satisfactory to both of us.

Marie Louise was never a facile writer; she thought deeply and could discuss matters with great coherence, but the work of setting her ideas down on paper was always laborious. This, it is true, was in part due to her dislike of anything slovenly or superficial, and when she did write her work was always distinguished by an extreme thoroughness. In this she applied to her own work the same severe standards of criticism as she always showed in her editorial work.

I am glad to think that I was, in some sense, the initiator of her major book, a treatise on Utopias which will be published next year. When the work was mooted by the Porcupine Press, with whom I was then associated as literary adviser, I suggested Marie Louise as a likely author. The result of her work was far better than any of us expected, for, instead of producing a mere introductory volume to the subject, Marie Louise completed, less than six months before her death, an exhaustive study of some hundreds of Utopian sketches. To the best of my knowledge, it will be the most thorough work of its kind, and should certainly establish a reputation for her as an important sociological writer; it is a tragedy for the world of social thought that the rich promise shown in this book will never reach its full fruition.

As the years went on, Marie Louise became conscious, like the rest of us, of the great complexity of the issues which faced the struggle for a free world. She realised the essential superficiality of many of the old romantic and optimistic assumptions of anarchism, and saw that the evolution towards the fulfillment of libertarian ideas was one which must take place on a much more complex foundation than the simple basis of economic struggle, and must embrace life in its varied aspects rather than in any limited range like that envisaged by the more sectarian syndicalists. While she never accepted any extreme “change of heart” theory, she was very conscious of the general effect of social conditioning upon wide masses of the people, and the difficulties it laid in the way of their enlightenment. For this reason, she became steadily more conscious of the need to concentrate closely on psychology and education. Long before her death, she had rejected any unrealistic optimism about the future. She realised the comparative slightness of the forces at present working for libertarian ideals, and she certainly did not rely, emotionally or intellectually, on a feeling of the certainty of “anarchy in our time”. But that made her more rather than less insistent on the need to propagate libertarian ideas, and she rightly pointed to the fact that, while the anarchist movement had never attained its full aims, and had gone through many vicissitudes of fortune, it had always provided a point of concentration for the heterogeneous forces working towards freedom, and had affected the mental climate of our age in a circle far exceeding that of declared anarchists. With her innate realism, she felt that even this limited achievement was worth the struggle and helped on the more or less long road towards eventual liberation. If she had abandoned optimism, she had that much more important quality for a revolutionary, a genuine and burning faith in her ideal, and I hope I shall not be misunderstood when I say that, in the sense used by Read in The Philosophy of Anarchism, Marie Louise was one of the few genuinely religious people I have met.

Yet she had none of the exclusive intolerance of the fanatic, nor was it in her warm nature to convert her work into the self-torture of an ascetic discipline. Whatever Marie Louise did was done with her whole personality, and in fulfillment of her nature, and involved no morbid self-sacrifice.

In addition to the propagation of anarchist ideas which was the main purpose of her life, and to which she brought that vein of realism associated with the great Italian thinkers, Malatesta and her father, Camillo Berneri, Marie Louise was a person of wide cultural and intellectual appreciation. Her interest in and knowledge of psychology were wide, and she had a deep appreciation of painting and literature. It was a regret that she often expressed to me, that she found it impossible to write creatively, yet her influence was nevertheless creative, for she had a sound critical sense, and her praise of one’s work was something to be treasured, since it was based on a fundamentally honest attitude that rejected all sham. To share a literary aesthetic experience with her was always a pleasure, and I can still remember vividly the most invigorating discussions on a remarkably wide range of writers and painters.

As a friend, Marie Louise is irreplaceable. She always tried, to the best of her ability, to understand the problems of those with whom she came into contact, and her nature had a warm gentleness and generosity which made her always solicitous for the welfare of those for whom she felt respect or affection. In her attitude towards others there was a directness which, indeed, sometimes led her into great unhappiness. For, although she was greatly interested in people, the essential simplicity of her own nature was an obstacle in understanding those of more complex and tortuous characters. Hence, she often showed a certain lack of prevision in her attitude towards people, which often led her to misunderstand their motives and behave without that elaborate tact which a more worldly-wise person would have adopted. Thus, by her very candour and honesty, she herself often helped to provoke the most unjustified enmities.

The recurrent tragedies and anxieties of her own life she bore with a serene fortitude which made her reluctant to allow them to impinge on the concern of others. Her feelings were deep and easily hurt, yet I can remember only two occasions on which she allowed them to break forth in a really demonstrative way, and those were when she had been subjected to the grossest of injustice by people who had formerly been her trusted friends and comrades.

The last occasion on which I saw her, a fortnight before her death and just before my own departure from England, she seemed far more alive and full of confidence than at any time since the beginning of the mental depression caused by the death of her child. We spent a long time discussing our plans for work in the near future. Marie Louise talked about her book of unpublished Sacco and Vanzetti papers, a collected edition of her father’s essays which she hoped to prepare, an essay on the revolutionary tendencies of de Sade on which she had done some preparatory work. But most of our discussion was on a scheme which had already been thought of a year before. Marie Louise had a remarkably clear and photographic memory of her childhood, and a very vivid way of talking about it. I had always found these reminiscences extremely fascinating, and had thought that they contained the material for a quite unique book on the experiences and impressions of a child in the society of political refugees between the wars. At this meeting, Marie Louise told me she had been thinking a great deal about this idea, and we agreed each to write about our childhoods in the form of letters across the Atlantic, which could be kept and placed together into books when we met again. It is against this background of rich and never-to-be-fulfilled schemes that I now see Marie Louise’s death, and realise the promise of which we have been deprived. And, remembering her gentle friendliness, I realise, with an intensity which the passage of months does not seem to diminish, what so many of us have lost in the enrichment she gave to our personal lives.

For her vivid and lovable personality, Marie Louise will live to the end of their lives in the minds of those who knew her intimately, and for whom her death now seems to mark the end of an epoch.

4. Press Tributes

From an American Jewish Paper, Freie Arbeiter Stimme (New York), 8 July, 1949

As our readers already know, Marie-Louise Berneri died in London three months ago. She was the daughter of our comrade, Camillo Berneri, who was murdered by the Bolsheviks in Barcelona in 1937. She played a leading role in the newly-revived anarchist movement in England. She was gifted with a rare grace and great beauty with which was combined exceptional intellectual capacity as a speaker, writer and research worker. Her sudden tragic death at so early an age was a great blow to the anarchist movement in England and in the world of those who knew her and loved her as no other woman who dedicated her life to the movement has been loved since the time of Voltairine de Cleyre. A special issue of Freedom (London 5/28/49) is devoted to generous appreciations of her life and work by many Englishmen and foreigners in the freedom movement who are sorrowing about her death, and the wound it has caused which will not for a long time be healed. The article we publish here represents some thoughts of hers on Utopias of the nineteenth century from the book which she finished before her sudden tragic death. That book will appear towards the end of the year from The Porcupine Press. This mere fragment which was published in Freedom shows how interesting, serious and spiritually-minded is her attitude towards that great and hitherto uncovered subject of social Utopianism ...

From a Mexican Paper, Solidaridad Obrera (Mexico City), 1 May, 1949