Thomas Schmidinger

The Battle for the Mountain of the Kurds

Self-Determination and Ethnic Cleansing in the Afrin Region of Rojava

Foreword to the English Edition

Afrin and the “Mountain of the Kurds”

Jewish, Alawite, and Shiite Neighbors

Hurrians, Hittites, and Assyrians

Rule of the Mendî under the Ayyubids and Mamluks

Afrin under the French Protectorate

Afrin as Part of Independent Syria

Syrian Troop Withdrawal in 2012

Democratic Confederalism in the Canton of Afrin

Safe Haven for the Internally Displaced

Development of the Canton of Afrin from 2012 to 2018

Autonomy with Difficult Neighbors

The Battle against the Islamic State and the Race with Turkey

Kurdish Enclaves in the Afrin Area

The War in Afrin and the Kurdish Opposition

EU Refugee Policy and the War against Afrin

Ethnic Cleansing: Arabization and Turkmenization

The Attack on the City of Afrin

The Battle for the Last Rural Areas

The Situation in the Province Şehba and at the Çiyayê Lêlûn

Afrin after the Turkish Conquest

Hêvî Îbrahîm Mustefa, Prime Minister of the Canton of Afrin (July 30, 2014)

Silêman Ceefer, Foreign Minister of the Canton of Afrin (February 2, 2015)

Fatme Lekto, Minister for Women of the Canton of Afrin (February 2, 2015)

Ebdo Îbrahîm, Minister of Defense of the Canton of Afrin (February 2, 2015)

Kamal Sido, Middle East Consultant of the Society for Threatened Peoples (March 11, 2018)

Foreword to the English Edition

Even though I’m extremely happy that this book has met with so much interest and that there is now an English translation, since the German first edition there have been quite a few ominous developments in the region.

Since the conquest of the city and region of Afrin by Turkey and its allies, the news has been very bad. There is no access whatsoever for independent media or scholars, which makes verifying news from Afrin extremely difficult. Nevertheless, I have done my best to update this history of Afrin and to give a brief description of the events that followed Turkey’s conquest of the region. A book can never be totally up-to-date, but I wanted to at least touch on the direction events have taken since March 18, 2018. The goal of this book is not just to inform the international public about how much history and culture is being destroyed but also to jolt it awake and remind it of its responsibility to the people of and from Afrin. Now that more than two hundred thousand people have been expelled from Afrin, this is an increasingly pressing responsibility.

Vienna, November 1, 2018

Preface: The Battle for Afrin

Let me begin with a curious paradox. Reading mainstream press, academic monographs, and leftist reports on the Middle East leaves American readers with a distinct feeling of despair. Journalists speak of the absence of democracy and modern political forms. Yet, in the middle of this region, there is a political space known to Kurds as Rojava, where democracy has been developed to an almost unprecedented degree. One could argue that democratic confederalism in Rojava is actually a more developed form of democracy than systems of representative governance that are mistakenly referred to as democracy. However strange this inclusive system of council-based, bottom-up governing practices might appear to a well-educated academic, there is little doubt that direct democratic forms and cooperative techniques developed in the stateless democracy in Syrian Rojava are a politically and sociologically remarkable example of egalitarian politics. Orientalist scholars often remind us of the grim reality of the “clash of civilizations,” with the Middle East serving as a paradigmatic case. However, the democratic federation of Rojava is home to a “democratic nation” developed to promote the peaceful coexistence of multiple ethnicities.

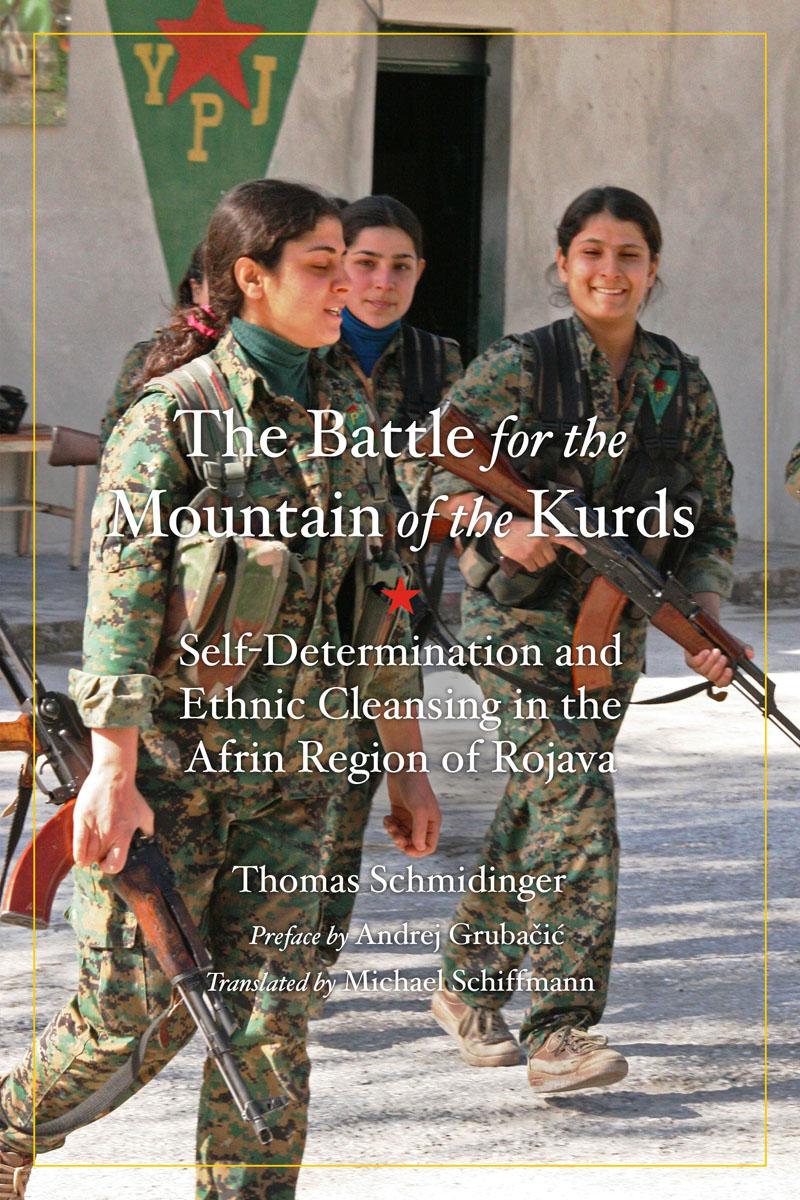

Humanitarian activists campaign tirelessly against the subjugation of women in the Middle East, but surprisingly there is a curious absence of reports on Rojava, whose constitution rests on three pillars: direct democracy, ecology, and liberation of women. A colleague from the Rojava University recently referred to women as the first colony. This is why any project of emancipation has to start with the history of male domination. In European press, there is an occasional mention of the remarkable courage of Kurdish women’s militia, the YPJ, but these sensationalized accounts omit the existence of the refined body of thought commonly referred to as “jinology,” a scholarly study of women’s liberation in Mesopotamia.

Political theorists speak eloquently of post-fascism and neofascism, and everyone is understandably shocked by the gruesome violence of the Islamic State, but few mention the antifascist struggle waged by the Syrian Kurds and the international brigades of European volunteers. Leftist activists bemoan the political status quo and the absence of alternatives to the rising right-wing populism, yet in Kurdish Syria a genuinely revolutionary society is being built and improvised from below and developed and sustained in the incredibly challenging circumstances of war.

Lastly, ecologists and environmentalists who speak about the need for an environmental justice movement, of the urgent need to transform the state of “indecisive agitation” into a viable political project, are largely unaware of the social ecology of Kurdish Rojava and its intricate system of ecological councils, networks, and anti-extractivist projects.

How can we explain this paradox? Certainly, a lack of reliable information is one explanation. There is almost too much to pay attention to in the tragic recent history of Syria (and Turkey). However, I suspect that there is something else going on, as well. The silence and unease that is palpable in various comments about the Kurdish struggle have more to do with the nature of the Kurdish revolutionary project: a form of political and intellectual organization that stands in stark opposition to liberal certainties, orientalist prejudices, and leftist revolutionary designs. Perhaps the language of clash of civilizations is not entirely misplaced.

What is the philosophy behind the Rojava revolution and the new chapter in the Kurdish liberation project? We could describe it as a confrontation between two versions of modernity. The Kurdish liberation movement speaks of a “democratic modernity” that opposes “capitalist modernity.” Democratic modernity as an integral organization of democratic nation, democratic communalism, and ecology. The cornerstone of this organization is a vision of a multiethnic nation detached from a dominant ethnicity. The defining element of democratic modernity, conceived of as an entirely different civilization, not just an alternative to the capitalist accumulation and the law of value, is one that requires a completely new definition of the concept of nation: as an organization of life detached from the state, a democratic nation as the “right of society to construct itself.” It is a consociation based on free agreement and plural identity. As a democratic organization of collective life, it is not based on homeland and market but on freedom and solidarity. In opposition to nation-statism, the democratic nation detaches itself from the nation-state, a core institution of capitalist modernity.

The basic political format of a democratic nation is democratic confederalism with democratic autonomy; an expression of a democratic nation, conceptualized as a pluricultural model of communal self-governance and democratic socialism. Democracy is understood to be a practice and process of stateless self-governance: the power of horizontally networked communities to govern themselves. The Kurdish liberation movement opposes the idea of a territorially bounded nation-state and linear progress that defined the liberal utopia. Capitalist modernity was built on this peculiar cultural construct of a state of nature, with an assumed inevitability of progress that blurred imperialism/colonialism abroad and representative democracy at home. Democratic modernity as a “collective expression of liberated life” stands in stark civilizational opposition to the capitalist trinity of patriarchal nation-state, capitalism, and industrialism.

This is the system that was, for all its shortcomings, implemented in the Afrin region, as detailed in this timely new book. Thomas Schmidinger, one of the few genuine experts on the topic of Kurdish politics, exposes many of the contradictions of a democratic autonomy under construction, while all the same remaining cautiously optimistic about its successful implementation. While Afrin was not a model of an ideal revolutionary society, it certainly contained a germ of a stateless democracy within the context of a democratic autonomy. This well-organized and illuminating account of the Afrin war includes an authoritative history of the region known as the “Mountain of the Kurds.” As far as I am aware, this is the first book in English on the topic of Turkish invasion against the Rojava Kurds. However, the timing is far from its only contribution. Schmidinger gives a comprehensive and objective account of the events that transformed this “island of peace” and multiethnic “mini-Syria” into an occupied territory emptied of its residents. The book artfully combines interviews and documentary material (in my opinion, the most valuable part of the book), relevant secondary accounts, and shrewd analysis that maintains a delicate balance between condemnation of Turkey and the European Union and of the “romantic dreams of European coffeehouse revolutionaries.” The result is rigorous and competent book by a scholar and activist in critical solidarity with the Kurdish liberation project. This critical position allowed the author to focus on his immediate task: a documented analysis of the Turkish offensive against Afrin and the Mountain of Kurds.

On March 6, 2018, the Turkish troops and their jihadi allies began their advance toward Afrin. Beginning on March 10, Turkish forces bombarded the homes of civilians, who at that point were resisting leaving the besieged town. Interviews with the civilians led the author to conclude that the Kurdish defense units known as the YPG and YPJ did not prevent civilians from leaving the town. The bloodiest day of the invasion was certainly March 16, when indiscriminate bombardment took the lives of at least forty-seven civilians, including the wounded in the Afrin hospital. The YPG and YPJ speedily withdrew from the city on March 18. Although he presents a number of possible explanations for this surprising move, the author believes that the real aim was to enable the safe retreat of the civilians. He maintains that the decision to withdraw from the city “probably did prevent an even worse bloodbath, while allowing the refugees to flee.”

The relatively stable border between the YPG/YPJ and the Turkish army (and its jihadist allies) reemerged on April of 2018. The entire Kurdish region of Afrin, with some exceptions in the east of the city, is now under the Turkish occupation. In these occupied areas, plundering and violence, including forced conversions of civilians, is taking place, although exact figures are impossible to ascertain. The United Nations estimates that up to seventy thousand civilians remain in Afrin, which is occupied by Islamist militias that enforce strict dress codes, while saluting the Turkish flag and decorating the schools in the region with pictures of Erdogan.

Why did the Turkish regime invade Afrin? The author suggests three principal reasons: destruction of the project of democratic autonomy, ethnic cleansing of the Kurdish population, and the EU-sponsored relocation of refugees from Syria. This plan is premised on the conscious and calculated intention of mobilizing “future ethnic conflicts.”

The greatest contribution of this excellent book is arguably the careful and detailed exposure of European complicity in the Turkish operations against Afrin. To give but one example, the German state has not ceased to export military equipment, including combat tanks, to Turkey (as high as 4.4 million pounds during the first weeks of the war; 98 million pounds in 2016). Exporting conflict goes hand in hand with importing Turkish politics and cracking down on Kurdish protests. Kurdish demonstrations are prohibited in Germany, home to a large Kurdish population, in an alleged effort to prevent the “importation of the conflict.”

To be sure, the most important part of the German and European assistance to the Turkish army resides in the European refugee policy. As the author makes clear, the cornerstone of the so-called refugee deal was the Action Plan for the Limitation of Immigration via Turkey, and later, in 2016, the new EU-Turkey agreement. Under the provisions of this document, Turkey will receive almost six billion euros to keep the refugees in Turkey, far away from Europe. As European authorities were undoubtedly aware, almost four million additional people in Turkey was bound to create a host of social and economic problems for Turkey itself. This contributed to Turkey’s decision to conquer Afrin: “In doing so the Turkish regime is not just concerned with domestic political power objectives and the destruction of de facto Kurdish autonomy but also with the repatriation of the refugees to Syria.” This anti-refugee policy, which amounts to “erecting a defense wall against refugees,” should resonate with those American readers concerned with Donald Trump’s xenophobic, authoritarian populism.

Repatriation and the “readmission of refugees” was one of the many propaganda lies of this terrible war. As Thomas Schmidinger makes abundantly clear, there were no refugees from Afrin in Turkey. The narrative was as consistent as it was false: allegedly Afrin was home to an Arab majority and a Turkmen minority, with Kurds making up only 35 percent of the population. The predictable result of the war is ethnic cleansing. Turkish forces, aided by their jihadist allies, have successfully expelled the civilian population, “creating room for the Turkish government resettlement program.” Giving the land “back to its rightful owners,” another oft-repeated propaganda slogan, in reality means Arabization and Turkmenization of the region and the destruction of its Kurdish character. Turkish NATO partners and Russia are united in tacit approval of this genocide. The much-vaunted “return of refugees” basically meant filling the houses of expelled civilians with Arab and Turkmen settlers from East Ghouta, as part of a larger project of Arabization and Turkmenization of the region. As I write this preface, more than two hundred thousand people have been expelled from Afrin.

This competent book is a welcome introduction to the history of Afrin. It is conceived of as a research tool, a compass to help us both to navigate the labyrinth of information about bellicose Turkish politics in the region and to illuminate the contradictions inherent in the Kurdish revolutionary project. More specifically, the book seeks to bring to light the obscured events of the Afrin war, as well as the contradictions of a moment that marked a historical turning point for people in the Afrin region.

Andrej Grubačić

Introduction

When I visited the autonomous canton of Afrin in 2015, what I found was a truly beautiful landscape and a tranquil people who, even though they were living under difficult conditions, were finding a way to live and were above all pleased to have overcome the dictatorship of the Arab nationalists, at least for the time being. The hopes of the ordinary people were not always as far-reaching as those of the political functionaries. Many of them just wanted a peaceful life alongside their Arab and Turkish neighbors.

That compared to the other regions of Syria Afrin was an island of peace was made clear by the fact that people from all over Syria had sought and found refuge there. Afrin became a sort of mini-Syria. It is not that there weren’t any conflicts or political problems. Afrin was no idyll, and I cherish the region too much to take the opportunity to project the romantic dreams of European coffeehouse revolutionaries onto it. But the people of the Kurd Dagh, the “Mountain of the Kurds,” as this region has been called for centuries, deserve a peaceful future, a future that the Turkish military attack that began on January 20, 2018, is meant to destroy.

The task of this book is to tell their story, to arouse its readers, and to make at least a small contribution to opposing the injustice done to the people there while I was writing this book and the Austrian publisher of the German edition was working as quickly as possible to publish it. Even though this book is based on a very long familiarity with and involvement in the region, it is, nonetheless, a “quick shot,” in the sense that I wrote it in just a few weeks, and the publisher got it onto the market very shortly thereafter. The price of working at that pace is that this book can only be rudimentary. It tells a story of the region but certainly also omits many facts and anecdotes that would have enriched the narrative.

Since the beginning of 2017, I have been trying to return to Afrin for further field research, but since 2015, shortly after my first stretch of field research, the path through A’zaz (which had already been difficult enough to traverse) has been ruled by various Islamist groups and has become just as impenetrable as the green border, which Turkey had turned into an imposing barrier. My only option would be to travel through government areas, but I have never acquired the necessary visa. As a result, I have been limited to communicating from far afield with acquaintances, friends, and political functionaries in the region, thus following events in Afrin from a distance. I have incorporated whatever I was able to take in through that process into this book to the best of my ability. I hope that the result will provide readers who haven’t visited the region with an impression of what is being destroyed at this very moment.

As I was finishing this book, hundreds of thousands of civilians were fleeing from Afrin. At this point, the international community, which allowed this massacre to unfold and, in part, even enabled it through its arms deliveries to Turkey, bears a lasting responsibility. Despite its conquest by the Turkish army and the Islamist militia allied with it, the history of Afrin is not yet at an end. It is, of course, incumbent upon the readers of this book to remind their own states of their responsibilities.

Afrin and the “Mountain of the Kurds”

The region of Afrin in the northwest of Syria is also called Kurd Dagh, an older Ottoman name meaning “Mountain of the Kurds.” It is also used in Arabic (Ğabal al-Ākrād) and Kurdish (Çiyayê Kurmênc in the local dialect). In Turkish, Kurd Dagh was distorted into Kurt Dağı in order to turn the “Mountain of the Kurds” into the Mountain of the Wolves (Kurt). Next to the Ğabal al-Anṣārīya (Mountain of the Nusayrians) and the Ğabal ad-Durūz (Mountain of the Druze), the Ğabal al-Ākrād is one of the three “ethnic mountain regions” of Syria where minorities had settled and, in part, retreated: the Druze religious minorities on the Ğabal ad-Durūz, the Alevi, who are also called Nusayrians, on the Ğabal al-Anṣārīya, and, of course, the Kurdish ethnic minority on the Ğabal al-Ākrād.

Until the partition of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, the northern areas that are today under Turkish rule were also regarded as a part of the Kurd Dagh. In Syria, the southern and central part of the “Mountain of the Kurds” became the region of Afrin. Qermîleq, the most western village in the region, directly at the border with Turkey, is only thirty-eight kilometers [twenty-three and a half miles][1] away from the Mediterranean Sea. Until the Turkish annexation of the Antakya/Hatay region between Afrin and the Mediterranean in 1938–1939, these villages in the west were more oriented toward Antakya and the Mediterranean ports than toward Aleppo. The larger part of the region, however, belonged to the sphere of influence of the Kurdish town of Kilis, which today is part of Turkey, and from which the “Mountain of the Kurds” was cut off when the new borders were demarcated after World War I.

The region of Afrin (Kurdish: Efrîn) is known for its olive orchards, said to contain a total of twenty-three million trees. Fruit and vegetables are also grown in the villages of this soft hilly landscape.

Altogether, the region comprises about 2,050 square kilometers [1,275 square miles]. Even though the whole Kurdish-speaking region around today’s city of Afrin is frequently called Kurd Dagh, the Kurd Dagh in the narrower geographical sense is actually only the massif in the west and the northwest of the region that extends into Turkish territory on both sides. This Kurd Dagh is a low mountain range with many gentle hills that rise to between 700 to 1,200 meters [2,300 to 3,900 feet] above the sea level. The actual Kurd Dagh, the high plateau of the Ğabal Sim‘ān (Kurdish: Çiyayê Lêlûn) in the southeast that rises up to 876 meters [2,874 feet] and the Ğabal Barsa further to the north that is 848 meters [2,782 feet] high, encompasses the fertile plain of the Afrin River, a plain called Cûmê in Kurdish. This plain borders the 149 kilometer [93 mile] Afrin River, which issues into the Orontes (Arabic: Nahr al-Asi), in the Turkish province of Hatay. This river irrigates a plain that is the site of intense agricultural use, with the town of Afrin, which was built in the 1920s, at its northern end.

The hills of the actual Kurd Dagh have also been used agriculturally for thousands of years. Even though the climate is generally dry, the winter rain, which reaches an average volume of more than sixty mm [two and a half inches] in December and January, allows for the growth of fruit and vegetables.

But by far the most important agricultural product of Afrin is olives. The whole region is planted with millions of olive trees, some of which date back to the time of the Romans and testify to the fact that growing olives already characterized the region two thousand years ago. The high-quality olives and olive oil from Afrin were famous across the Levant and were the most important ingredient in the famous Aleppo soap.

Until the Turkish attack in January 2018, Afrin was one of the quietest regions in Syria. Up until then, the self-administration established in 2012 had succeeded in keeping the civil war away from the local population. Therefore, Afrin also became a haven for those expelled from other parts of Syria. But now, Afrin and the “Mountain of the Kurds” are in danger of being destroyed by the war. Already there are strong hints that Turkey and its allies not only want to occupy the region but also hope to expel the local population and settle Arab refugees from Syria there to enhance their control and create a buffer zone for Turkey.

Population and Language

Serious up-to-date data on the population of Afrin are impossible to get. Therefore, we can only guess that at the beginning of the Syrian civil war, three hundred to four hundred thousand people lived in the Afrin (Kurdish: Efrîn) region, of whom more than 98 percent had Kurdish as their mother tongue.

Since the Middle Ages at least, but possibly also in pre-Christian times, the region was characterized by Kurdish tribes (Kurdish: Eşiret) and by the beginning of the French protectorate was regarded as a coherent Kurdish settlement area. The Kurd Dagh was inhabited by five different Eşiret: the Amikan, Biyan, Sheikan, Shikakan, and Cums. The smaller tribes of the Robariya, Kharzan, and Kastiyan, among whom the Muslim Robariya exerted a kind of protectorate over the villages of the Êzîdî in the region, were much weaker.[2] Since the latter also spoke Kurdish, we can safely assume that almost the entire population was Kurdish-speaking by the beginning of the twentieth century. Thus, Afrin formed a region that was both ethnically and linguistically far more homogeneous than, for example, the Kurdish-dominated regions further to the east, where there were large Armenian minorities in the cities, where Aramaic-speaking regions alternated with Kurdish regions, and where Arab tribes had already been living before the Syrian regime’s deliberate settlement of Arabs. Apart from the small Armenian community and the small number of Arabs from the Emirati and Bobeni tribes, there was scarcely any other group present.

The Dūmī, however, are one small minority that is still present in the region. They are related to the European Roma and occupy a position in the Middle East similar to that of the Roma in Europe. Most Dūmī still speak their own language, Domari or Nawari, as well as at least one or two other languages, usually Kurdish and Arabic. The Dūmī of Afrin as a rule also speak Kurdish. Because of cultural and social similarities, they are often regarded as a subgroup or “branch” of the Roma.[3] Some linguists, however, advance the thesis of an earlier autonomous migration of the Dūmī from India to the Middle East and trace the relationship of the languages back to earlier commonalities in India.[4] Alongside Turkish and Arabic loanwords, we also find Kurdish loanwords in the Dūmī language,[5] which is evidence of a long cohabitation with the speakers of these languages in the region.

Apart from their own language, the Dūmī of Afrin generally use Arabic or Kurdish. Since most of them have never had any official education, they are only rarely able to read or write these languages. The civil war has made the migrations of this group much harder. Since 2012, many of them have become semi-sedentary inhabitants of squalid huts or tents at the outer limits of Kurdish cities.

The Büd, a Kurdish-speaking group that came to Afrin from Besni, near Adıyaman (Kurdish: Semsûr) in today’s Turkey, after the Sheikh Said uprising in 1925, have a similar status. The group refers to itself as “nomadic” (Kurdish: Koçer) but is referred to by outsiders as either Büd or Ghorbat (Kurdish for “gypsies”). Until recently, this group still lived in tents and wandered from village to village within the Kurd Dagh region, often crossing the Syrian-Turkish border in the process. In an interview with Kamal Sido of the Society for Threatened Peoples, a Büd woman explained: “For many years, we have regularly crossed the Syrian-Turkish border. For us, this border simply doesn’t exist, and therefore, many of us speak Turkish really well.”[6] The members of the group speak their own dialect and marry primarily among themselves. Many of them previously worked as basket makers and wandering dentists.

The number of Kurds living in the region at the beginning of the civil war can only be estimated but couldn’t have been higher than four hundred thousand. But by 2018 about two hundred to three hundred thousand people expelled from other parts of Syria had been added to the region’s population. At the same time, tens of thousands of people fled to Europe. But still, one can safely say that in 2018, compared to the population at the beginning of the civil war, a significant number of additional people lived in the region of Afrin. Among the new inhabitants are Kurds from Aleppo and other parts of Syria, as well as Arabs and members of other population groups in the country. Altogether, the region comprises 366 villages and settlements. The only real urban center is the town of Afrin (Kurdish: Efrîn), which according to the 2001 census had 43,434 recognized inhabitants, a number that had approximately doubled by the start of the civil war. Together with the displaced persons living in the city, the population of Afrin may have grown to around one hundred thousand before the Turkish attack in 2018.

Apart from Afrin, there are a few additional small-town centers that are important as regional market cities, including Cindirês in the south, Mabeta in the center, and the cities of Reco and Şiyê in the west.

The Kurds of Afrin speak Kurmancî, which is the most widespread form of Kurdish, and which is also spoken in the rest of Syrian Kurdistan, in most parts of Turkish Kurdistan, and in the northern areas of Iraqi Kurdistan and Iranian Kurdistan. But Efrînî, the dialect of Afrin, has some peculiar features in its grammar and pronunciation.

To the south and to the east of Afrin, there are additional Kurdish settlements representing mixed-language enclaves, where Arabic and Turkmen, as Turkish is called in Syria, are also spoken. The small town Til Eren (Arabic: Tal Aran), with its 17,700 inhabitants, and the nearby town of Tal Hasil/Tal Hasel, about ten kilometers [six miles] to the southeast of Aleppo, also have Kurdish majorities, as do the Sheikh Maqsood (Kurdish: Şêxmeqsûd) urban quarter in Aleppo and a number of villages in the districts A’zaz, al-Bab, and Jarābulus.

Religious Communities

Muslims

Today the overwhelming majority of the Kurds in Afrin are Sunni Muslims, even though many of them only converted to Islam in the twentieth century and have Êzîdî roots. The Sunni Muslims of Afrin belong to the Ḥanafī school of law, or school of thought (maḏhab), which distinguishes them religiously from most other Kurds.

The majority of Sunni Kurds in Syria, Iraq, Turkey, and Iran belong to the Shafi’i school of law, or school of thought. Today, this doctrine of Sunni Islam, which can be traced back to Muḥammad ibn Idrīs aš-Šāfi‘ī (776–820), is primarily present in Egypt, East Africa, the former South Yemen and Dhofar (Oman), Indonesia, Malaysia, and among the Sunni Kurds but not among Sunni Arabs in Syria or the Turks in Turkey. The prevalence of the Shafi’i school of law in Syria and Egypt goes back to Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf bin Aiyūb ad-Dawīnī, the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, who became famous in Europe as Saladin, liberated Jerusalem from the crusaders in 1187, and was himself a Shafi’i Kurd. While the Ottomans would later show a preference for the Ḥanafī school of law and help to bring about the latter’s breakthrough in the Arab cities of Syria, many Kurdish tribes have remained Shafi’i to this day. But Afrin is located at the periphery of Kurdistan, in the far west of the Kurdish linguistic area. The region belongs to the narrower sphere of influence of the city of Aleppo. In the twentieth century, the tribes had already ceased to play an important role, and the late conversion of many Kurds from the Êzîdî religion to Islam thus took place under the influence of Ḥanafī Sunnis from Aleppo and not as a result of the pressure of Shafi’i Kurds. Regardless of the minutiae of these processes, the fact is that today the Kurds of Afrin are the only Ḥanafī Kurds in Syria.

As in many rural regions of Syria and Kurdistan, here too Sunni Islam is strongly influenced by Sufi brotherhoods and local cults of the saints. Thus, at the ancient archaeological site of Cyrrhus (Κύρρος), near the village Dêrsiwanê, a hexagonal Roman mausoleum from the third and fourth centuries after Christ is venerated as the Tomb of the Nani Huri (prophet Huri). The mausoleum is an important regional pilgrimage site connected to a fourteenth-century mosque and a group of trees where pilgrims hang pieces of cloth inscribed with their personal wishes. In addition, on the northern exterior wall of the mosque there are also a few shallow recesses into which pilgrims can insert small pebbles. If these remain in place, this is a sign that a wish connected with this act will be fulfilled without requiring any sacrifice in return. And finally, a protective handprint made from the blood of sacrificial animals (the Hand of Fatima) is left on the wall.[7]

But this is far from the only sanctuary frequented by local Muslims. Several tombs of saints that are simultaneously used as meeting places for Sufi brotherhoods (Zāwiya), such as the Zāwiya of Sheikh Rashid located a few kilometers [a couple of miles] northeast of the city of Afrin or that of Sheikh Mahmud Husayn (who only died in 2000), are important local pilgrim sites.

Besides the Sufi brotherhoods of the Naqshbandīya—or, rather, the Khalidi current of the Naqshbandīya going back to Mewlana Xalidê Kurdî/Mewlana Khâlid-i Baghdâdî[8]—and the Qādirīya, both of which are widespread in all of Kurdistan, the brotherhood of the Rifa’iyya is also popular in Afrin. Beginning in the fifteenth century, this Sufi brotherhood founded by Ahmad ibn ’Ali ar-Rifa’i during the twelfth century was replaced by the Qādirīya in most parts of Kurdistan. But in Afrin, the followers of the sheikh, who is buried near the Iraqi Tal Afar, are relatively numerous to this day.

The emergence of new groups of Sufis in Afrin is by no means only a matter of the past. In his field research in the region, the social and cultural anthropologist Paulo Pinto observed that the last decades saw the development of new Sufi communities that are not necessarily in the tradition of a particular Sufi brotherhood, but, rather, gather around some charismatic sheikh.[9] When the sheikh dies, his tomb becomes the center of the new community.

Êzîdî

The south and the east of Afrin form the largest contiguous settlement area of the Êzîdî (in English, Yezidis or Yazidis) in Syria. The Turkish historian Birgül Acıkıyıldız, who specializes in the Êzîdî and the Ottoman Empire, believes that the presence of the Êzîdî in the region dates back to the twelfth century.[10] On the other hand, in his investigations among the Êzîdî in Syria and Iraq in the 1930s, the French Orientalist and Kurdologist Roger Lescot arrived at the conclusion that the first Êzîdî only settled in the region of Afrin in the thirteenth century.[11]

We know for sure that there must have been a strong presence of the Êzîdî in today’s region of Afrin by the fifteenth century, because the important Kurdish poet, prince, and historiographer Sharaf ud-Dīn Khān al-Bitlīsī mentions their presence in his classical source on Kurdish historiography the Sharafnāma, which first appeared in 1597.[12]

In the past, the Êzîdî represented a distinctly larger part of the population of the region than today, but they were in a dependent relationship with the Muslim Kurdish tribes in the region. Thus, the inhabitants of the Êzîdî villages were subordinate to the Muslim tribe of the Robariya.[13]

The Êzîdî religion is an autonomous monotheist religion that draws from several Middle East religious sources. The Êzîdî believe in a God for whom they use the Kurdish word for “God,” which is also used by Kurdish Muslims, Christians, and Jews, namely, Xwedê. This God, however, is very abstract and normally interacts with humans only via mediating angels, particularly the Peacock Angel (Kurdish: Tawûsê Melek).

The Êzîdî religion as we know it today was shaped by Islamic and possibly also Christian, Jewish, and Manichean influences on a Western Iranian religion. One controversial point is how to assess the relationship of the Êzîdî religion to other Iranian religious orientations, particularly to Zoroastrianism. Today Philip Kreyenbroek, who is probably the most renowned Iranist to focus on the Êzîdî religion, writes that research regarding the relationship between Êzîdism and both Zoroastrianism and Yarsanism (a current that is equally widespread in Kurdistan) indicates that even though Êzîdism and Yarsanism “are related to Zoroastrianism, they do not directly stem from it. Rather, important elements of this religion go back to a very old Western Iranian tradition that also played a role in the emergence of Roman Mithraism, which one could thus call ‘proto-Mithraism.’”[14]

The persecution of the Êzîdî is based on a misunderstanding handed down through the centuries, according to which they are devil worshippers. Apart from God, this religion, which in its present form goes back to the Sufi-Sheikh Adī ibn Musāfir (Kurdish: Şêx Adî), who lived in the twelfth century and came from Lebanon, venerates the Peacock Angel, who is regarded as the first and most faithful angel of God. Because the Peacock Angel was particularly reverent in his faith in God, he also kept God’s first commandment, namely, to venerate nobody but God. Therefore, after God made Adam, Tawûsê Melek refused the order to prostrate himself before the newly created human being. He was thus tested by God and passed, a narrative that starkly contradicts the Christian and Islamic idea of hell, in which this angel was punished and then transformed into the devil. Unlike these two religions, the Êzîdî have no concept of hell as a place of eternal condemnation. For the Êzîdî, God is almighty to such an extent that there can be no second force that represents personified evil. Nonetheless, the similarity of the story of the Peacock Angel to that of the Islamic and the Christian devil, who refused to bow down before humans out of arrogance, was used for centuries to insinuate that the Êzîdî were “devil worshippers,” an absurdity when you consider that this kind of personified evil doesn’t even exist in the Êzîdî worldview.[15]

A further accusation Muslims have often leveled at the Êzîdî is that, as opposed to Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians, they are not a religion of the book,[16] suggesting that this religious minority has no claim to the protection classical Islamic law affords to the “religions of the book.” And, indeed, the Êzîdî religion could even be called anti-literate, given that the essence of the religion and its songs, the Qewel, are always handed down orally. Muslims who understand the Islamic tradition such that their tolerance is extended only to the religions of the book pose a genuine problem for the Êzîdî. In response, a myth has developed among many Êzîdî that a Holy Book of the Êzîdî, the Meshaf-ı Reş (the Black Book), actually exists but has disappeared.[17] During my field research in Syria, I was even approached by Êzîdî sheikhs who claimed that this book had been stolen by Austrians and was now in a museum in Vienna, and who asked me whether I could not take steps toward having the book returned to the Êzîdî. In reality, however, there is no such book in any Austrian museum or in the Austrian National Library.

The background of this myth is that in 1913 the Austrian Orientalist Maximilian Bittner published a book titled The Holy Books of the Êzîdî or Devil Worshippers with the Austrian Academy of the Sciences.[18] The authenticity of book, which is barely a hundred pages long and is based on writings that had been bought from local Christians, remains controversial to this day.[19] Be that as it may, among the Êzîdî of the Middle East, these writings could certainly not have had the importance that the Quran has for the Muslims or that the Bible has for Jews and Christians, since there are no original copies of this “Holy Scripture” extant. The longing for an authentic Holy Scripture reflects the wish to be accepted as a religion of the book by their Muslim neighbors and to acquire the protection that would follow from this.

Most of the Êzîdî villages in the region are located to the west and south of the city of Afrin. In the north, Qestelê and Qitmê are among the most important. To southwest of Afrin, there is another larger Êzîdî village, Feqîra. But the main area of settlement lies in the southeast of the Kurd Dagh, and includes the villages Beradê, Bircê Hêdrê, Basûfanê, and Kîmarê.

This is one of the reasons for the particularly difficult situation of the Êzîdî, whose villages became a target of attack for the Jabhat al-Nusra in 2012 and for the Hai’at Tahrir ash-Sham since 2017. In the north, most Êzîdî villages are located between the town of Afrin and the town of A’zaz, which was conquered by the Islamic State, Jabhat al-Nusra, and other opposition groups on September 18, 2013. This frequently places the approximately twenty Êzîdî villages in the region (the exact number depends on the counting method) directly at the front line of rival Arab and jihadist opposition groups.

Until 2018, the Êzîdî had been safe in the regions of Afrin under the control of the Kurds, but in the neighboring regions under the rule of pro-Turkish militia the picture has been quite different. On June 12, 2017, the Êzîdî inhabitants of the small village Elî Qîno in the northwest of A’zar were expelled. The village is located to the west of the barricade that the Yekîneyên Parastina Gel/Yekîneyên Parastina Jin (YPG/YPJ) had erected at the border of the area under their control and was under the de facto control of pro-Turkish rebels. On that day, a Monday, the Êzîdî population was given one hour to leave their homes. Most of the inhabitants fled to Afrin, and their houses were confiscated by pro-Turkish rebels.[20]

In today’s Syria, this minority is under enormous pressure, but it also suffers as a result of the internal conflict between a current close to the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê/Partiya Yekîtîya Demokrat (PKK/PYD)[21] that is not only trying to reconfigure the Êzîdî religion as a variety of Zoroastrianism but also to reform it and the traditional Êzîdî who regard this very “Zoroastrianization” as an attack on their religion. Extremely strict marriage rules and the rigid social system, both of which are no longer accepted by some of the younger Êzîdî, are also a source of conflict.

Êzîdî society is divided into three groups that each have different social and religious functions: the simple faithful, the Murid, are only allowed to marry other simple faithful people; members of the Sheikh group, only other members their group; and the priests, or Pîr, only other Pîr. Among the older Êzîdî, the strict marriage rules that only allow for marriage within one’s own group are still unquestioned. When I asked about this, an older member of the Pîr group from the village of Feqîra responded: “This is not open to debate. The marriage rules are a central part of our identity. All Êzîdî must stick to them.”[22]

The religious identity crisis of many Êzîdî also has to do with the fact that the Êzîdî, particularly those of the Kurd Dagh region, have extremely limited access to the Êzîdî religious centers in today’s Iraq, have few religious scholars, and, unlike the Êzîdî in the Ğabal Sinjar (Kurdish: Şingal) or in the Şexan region near their religious shrine in Lalish (Laliş), have been much more thoroughly integrated into the Sunni population. In the 1930s, Lescot described the Êzîdî in the Kurd Dagh region as a group that was hardly distinguishable from its compatriots.[23] The orientation of these Êzîdî toward a form of Êzîdîsm that the PKK has declared to be a variety of Zoroastrianism is also based on this far-reaching loss of old religious customs. In a way, it is the reinvention or new invention of a religion whose members in the Kurd Dagh, even though they still form a separate group, have for the most part already forgotten their religious traditions. Distinct from other regions of Kurdistan, the Êzîdî in Afrin were called Zawaştrî, that is Zoroastrians, even before the ascension of the PYD to power, although Zoroaster and his teachings actually didn’t play a significant role at the time.

The form of the Êzîdî shrines (Ziyaret) in Afrin is different from that of the shrines in their religious centers in Iraq. The shrines are not characterized by the typical pointed conical roofs but are either simple flat-roofed buildings or are adorned with a cupola. For example, the Malak Adî shrine, which possibly refers back to Şêx Adî from Laliş, like many Islamic tombs in the region, only has a dome. The same is true for the shrine of Sheikh Barakat and other important Ziyaret. Only some of the newer Ziyaret have the pointed conical rooves typical for the Êzîdî in Iraq.

Unlike many other religious minorities in Syria, the Êzîdî have never been an officially recognized religious community. Even though the secular authoritarian Ba’ath regime has occasionally offered protection to Christians, Druze, or Alawi, it has not done so for the Êzîdî. It was only after the withdrawal of the Syrian regime from the Kurdish areas that Êzîdî were able to organize themselves. Since then, new Êzîdî umbrella organizations have loudly raised their voices and have gotten involved in shaping the future of the region.

On February 15, 2013, the Êzîdî organized their first local councils in the Hasaka region, which is not in Afrin but in the Cizîrê. This was supported by the new Kurdish administration, and additional villages in various parts of the Cizîrê soon followed suit.[24] These associations formed the Association of the Êzîdî of West Kurdistan and Syria (Komela Êzdiyên Rojavayê Kurdistanê û Sûriye, KÊRKS), an umbrella organization close to the PKK. The Council of the Êzîdî of Syria (Encûmena Êzdiyên Sûriyê, EÊS) and the Union of the Êzîdî of Syria (Hevbendiya Êzîdiyên Suriyê, HÊS) emerged as rivals. While the HÊS has clearly had a rapprochement with both the PYD and the KÊRKS in the last two years, the EÊS still maintains its strict opposition to the PYD.

These three associations also represent very different concepts of identity. While the EÊS bases itself on traditional Êzîdî, who see the Êzîdî religion as an autonomous religious community, the KÊRKS pursues the Zoroastrian interpretation of the Êzîdî religion described above. This became clear in 2014 when the most important Êzîdî center in Afrin, the KÊRKS-affiliated Mala Êzîdîya in Afrin City, erected a life-size statue of Zoroaster in front of the building, an event that caused quite a stir, and not just among the traditional Êzîdî in Afrin but also internationally among Êzîdî organizations abroad. The HÊS is located somewhere between these two positions. Politically it is now close to the PYD, but as a splinter from the Council of the Êzîdî of Syria it still advocates a rather traditional concept of Êzîdî identity that doesn’t see the Êzîdî religion as a variant of Zoroastrianism.

The Alevi

The Alevi are primarily concentrated in the small town of Mabeta and a few hamlets in the area that are all part to the subdistrict (nāḥiyah) of Mabeta. At the last census, in 2004, which did not address religious affiliation, the subdistrict had more than eleven thousand inhabitants, not all of whom, however, were Alevi. The number of Alevi is probably somewhere between five thousand and ten thousand. They are genuine Alevi, a form of Shiite heterodoxy that is also widespread among Turkish-, Zaza-, and Kurmancî-speaking Turkish citizens, but not among the Alawites, who are widespread in Syria or among the Arab-speaking minority of Hatay or the Çukurova in Turkey. The Alawites represent a different religious current that, beyond a loose connection with Shiite Islam, doesn’t have much to do with the Anatolian Alevi or the Alevi of Mabeta.

The Alevi depart from the practice of faith of Sunni Islam and of the orthodox Twelver Shia in many ways. They don’t pray in mosques but hold their religious celebrations, which they call Cem, in Cem houses. While the Sunni and Shia practice ritual prayer, the Alevi worship God through songs, the recitation of poems and Quranic passages, and ritual dance (Semah), and men and women pray and celebrate together. The Alevi regard neither the five pillars of Islam nor the sharia as binding. Compared to the Sunni and Shia mainstream, in Alevism laws and orthopraxis play a subordinate role. As a form of Islam persecuted and driven underground for centuries, Alevism must basically be seen as a popular religion that has spawned only a very few theologists and scribes. Alevi religiosity was not handed down through Quran schools and scholarly writings but through families, poems, and songs.

The center of the Alevi philosophy is the interaction between humans themselves and between humans and God, and certain pantheist ideas have also become part of Alevism. The faithful strongly recognize God in their fellow human beings.

The frequent characterization of the faith by secular Alevi intellectuals as a sort of “liberal Islam” must be qualified. Just as in Sunni and Shia Islam, there are both stricter and less strict readings and interpretations of the faith among the Alevi, but Alevi communities are generally like the others in traditionally regarding adherence to strict social rules as the educational goal. A violation of these rules can lead to the exclusion from a Cem celebration, or even from the community itself. These social rules are summarized by three commandments:

-

Control your hands: don’t kill, steal, or do violence to anyone.

-

Control your tongue: don’t swear, lie, or badmouth others.

-

Control your loins: faithfulness, monogamy, no extramarital sex.[25]

In matters of community organization, the Alevi are strictly divided into two groups whose membership is determined by descent. “Both practice endogamy, because their relationship is thought of as one between parents and their children. It follows that marriages between the two groups are seen as incest.”[26]

In and around Mabeta, there are close to a dozen Alevi shrines whose names generally end with “Dada” (Dede): Yagmur Dada, Aslan Dada, Ali Dada, and Maryam Dada. As among the Anatolian Alevi, the clerics of the Syrian-Kurdish Alevi are also called Dede or Dada.

Even though there are no historical records about the immigration of the ancestors of the Alevi of Afrin, it seems reasonable to assume an immigration from the Alevi areas of Kurdistan, which are today part of Turkey. Some of the Alevi of Mabeta only arrived in the region in the twentieth century. In 1938, the Alevi of Mabeta took in refugees from the Dersim massacre. Eighty years later, their descendants are once again fleeing from the Turkish army.

Even after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the Alevi of Mabeta remained in contact with the Alevi in Turkey, and religious relationships with the Anatolian Alevi were never cut off.

Just like the Êzîdî, the Alevi only began to create formal organizations in 2012. The most important of these is the Center of the Alevi of Mabeta (Navenda Elewiyan ya Navçeya Mabeta) in the small town of the same name.

Like numerous Êzîdî, many Alevi also supported the secular political system established in Afrin since 2012, with Hêvî Îbrahîm Mustefa, an Alevi from Afrin, serving as prime minister of the region.

Christians

There was a historical presence of Christians in Afrin, but it has nothing to do with the Christian community in Afrin today. Early Christian ruins testify to the fact that the region of Afrin, like the neighboring Antioch (which is now part of Turkey), is part of the core lands of early Christianity. The most important of these buildings is probably the Qal‘at Sim‘ān (Simon’s Fortress), which is located at the border between Afrin and the areas to the south of the region held by Sunni rebel groups. This is a large Byzantine monastery, erected where, according to legend, Symeon Stylites the Elder (389–459) is believed to have lived atop a pillar for several decades. This began the trend of the “pillar saints” in Syria, which remains an allegory in contemporary usage. Even in the twentieth century, artists, including the Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel in his film Simon in the Desert (Simón del desierto), have addressed the topic.

In the Byzantine era, there was a large monastery here whose ruins are still among the most important tourist attractions in Syria. Since the beginning of the Syrian civil war, it has been at the front line between the YPG/YPJ and the Sunni rebel organizations. The shifts in control of the front line have likely led to the ruins being damaged.

In the case of today’s city of Cindirês, we know of a diocese at the time of the Council of Nicaea in the year 325.

The mountains near the ancient town of Cyrrhus in the north of Afrin, where Muslims venerate the tomb of the prophet Huri, are believed to be where the monk Maron, whom both the Maronite and Roman-Catholic Churchs see as a founding father, was active. His alleged grave is near the village Beradê (Arabic: Brad) in the south of the region of Afrin, northeast of Qal‘at Sim‘ān. There are several church and monastery ruins in the area, among them the historically significant Great Chapel of Julianos. Until the start of the civil war, Maronite Christians from the Lebanon made the pilgrimage to the Tomb of Maron in Beradê: in 2008, on the occasion of the sixteen hundredth anniversary of the death of Saint Maron, later Lebanese president Michel Aoun was one of the prominent pilgrims. The years before the civil war even saw the construction of a small new church, and, in 2010, a statue of Saint Maron from Lebanon was placed in it. But the church only served Maronite pilgrims for a short while, since there has not been any Maronite community here for quite a while. There is no continuity between the early Christian communities of the region and later Christian communities. Under Islamic rule, the early Christians, who spoke Greek and Aramaic, either migrated to the larger urban centers or, over the years, converted to Islam. There are, however, no detailed reports about any of this.

It is well known that after the genocide against the Armenians in 1915, survivors settled in Afrin. There was an Armenian-Apostolic church and an Armenian school in the town of Afrin. But the sparse data seem to indicate that the Armenian community was never very large. In the 1958–1959 school year, only fifty students attended the school, which was run by no more than two teachers.[27]

In 1927, the Armenian liquor producer Sarkis Kiwanian began to produce Arak in Afrin, and at the start of the civil war, this most reputed Syrian anise liquor was still produced there.

In a 2015 interview with Kamal Sido of the Society for Threatened People, one of the last Armenians of Afrin shared memories of the community that existed until the 1960s and had approximately one hundred members.[28] In the second half of the 1960s, most of them emigrated to the U.S., Armenia, or Aleppo. The church fell into ruins, and the property on which it stood was sold. Finally, the ruins were removed to make way for a new building. When Kamal Sido conducted his interview with the then fifty-eight-year-old Aruth Kevork in 2015, the latter explained that his family was the last remaining Armenian family in Afrin. In 2018, the editor of the Armenian newspaper Kantsasar, which is published in Aleppo, Zarmig Chilaposhyan-Poghigian, claimed that there were still three Armenian families in Afrin.[29] This “increase” can possibly be explained by the flight of Armenian families from other regions in war-torn Syria. At any rate, since the late 1960s, there has been no actual Armenian community in Afrin, only individual Armenian families.

However, this does not mean that Christianity has entirely disappeared from Afrin. In 2012, with the new Evangelical Church of the Good Shepherd (Şivane Qanç), a Christian community of Kurdish converts emerged in Afrin. This community originated in Aleppo but migrated to Afrin when the war in Aleppo started. By 2018, this Kurdish Christian community had increased to a total of three hundred families. Apart from the city of Afrin, churches were also built in the small cities of Cindirês and Reco, but these communities are much smaller, and most of the Christians of the region of Afrin live in the city of Afrin. Following the Turkish invasion of the region, members of the Christian communities of Cindirês and Reco fled to the city of Afrin. It is impossible to know whether the church buildings they left behind survived the Turkish army’s bombardment, which did severe damage, particularly in the city center of Cindirês. Most of the Christians from these two communities who had to flee found a provisional haven in the Church of Afrin, until they had to flee once more following the conquest of Afrin.

While converts face severe problems in many Islamic communities, in secular Afrin the conversion to Christianity is relatively unproblematic. The rise in conversions to Christianity since 2015 seems to have to do in part with an oppositional stance against the jihadist militias, particularly the Islamic State, but probably also represents a form of “cultural conversion.” The middle and upper strata of society in particular want to “Europeanize,” in an effort to stand apart from their Islamic surroundings. They frequently see Christianity as “modern” and “secular,” while they regard Islam as “backward” and “fanatical.” These perceptions of both the self and other seem to play an important role in the conversion to Christianity. It is interesting that these Kurds do not convert to one of the traditional Syrian churches but to an actively proselytizing Evangelical Church community under a charismatic pastor of Kurdish origin named Diyar. Pastor Diyar has raised his voice against the Turkish attacks on Afrin several times since they began and has articulated his fear that a Turkish victory could prove particularly dangerous for Christians in Afrin. “If these gangs enter Afrin, before all, they will kill Christians,” a Kurdish news agency quoted him saying in early February 2018.[30]

Jewish, Alawite, and Shiite Neighbors

Unlike Cizîrê, where there was a Jewish community in Qamişlo well into the twenty-first century, and where there is still a synagogue, no Jewish community ever existed in modern Afrin. But in the Turkish town of Kilis located directly at today’s national border, there was once a synagogue, and its ruins survived and served an Arabic-speaking Jewish community until the twentieth century.[31] Furthermore, the nearby metropolis of Aleppo was one of the most important centers of Jewish life in Syria. West of Afrin, in the town of Antakya (the former Antioch), which has been part of Turkey since 1939, there is still a small Jewish community with an intact synagogue. At this point, the community only consists of a few more than a dozen faithful, but it is the only remaining Jewish community of the three that once surrounded the “Mountain of the Kurds.” These communities, in Aleppo, Kilis, and Antakya, used Arabic as their everyday language and were oriented toward the region’s urban centers. Though there might have been individual Jews who lived in between these communities temporarily, acting as business contacts between Kurds and Jews in these three urban centers, which were in turn important for the Afrin region, at least following the Islamization of the region, there has been no known settlement of Jews in the region of Afrin.

The Kurds of Afrin were also in neighborly contact with other religious communities. In Antakya and the region around it, which until 1938 was still part of the French protectorate of Syria and has been part of Turkey since 1939, there were many Arabic-speaking Alawites, members of a Shiite heterodoxy that should not be confused with the Alevi, and whose members also live in Syria, specifically, in the coastal mountains of the Ğabal al-Anṣārīya. The Syrian ruling Assad family is part of this religious minority. Under Hafiz al-Assad, the father of the current president, many Alawites gained important posts in the military, the secret services, and the police force, which has contributed to the confessionalism of the conflicts in Syria since 2001.

In the southwest, Afrin abuts the small Arabic-speaking towns of Nubl, with a population of twenty-one thousand, and az-Zahrā’, with thirteen thousand inhabitants, whose majority belongs to the Twelver Shia variety of Islam, the current of that religion that is the state religion in Iran and the majority religion in Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Bahrein. Because of the confessionalism of the conflict, the populations in Nubl and az-Zahrā’ remained loyal to the regime. Both cities have been continuously held by militias loyal to Damascus, even though from 2012 to 2016 they were only an enclave within an area held by oppositional forces. For the Shiites in Nubl and az-Zahrā’, the Kurds in Afrin became important mediators. From July 2012 to February 2016, Afrin was the only way out for the Shiites living there. Now Nubl and az-Zahrā’ function as the escape hatch for Kurds from Afrin who are fleeing the attacks by Turkey and its allies.

History

Early History

The oldest archaeological discoveries in the region of Afrin are to be found in the cave of Dederiyeh in the south of today’s canton of Afrin, about sixty meters [196 feet] above the bottom of the Wadi Dederiyeh valley. In 1987, human and animal bones were excavated, and the human bones have been associated with at least seventeen different individuals belonging to the Neanderthal genus. In August 1993, an archaeological research group under the direction of Takeru Akazawa discovered the almost complete skeleton of a child that was more than fifty thousand years old. Like this first one, a second child skeleton found in 1997–1998 showed signs of ritual burial.[32]

The Dederiyeh findings not only belong to the oldest human findings in the Middle East but also to the first indications that fifty thousand years ago the Neanderthals were carrying out ritual burials and possibly even had a spiritual conception of an afterlife. However, most of the bone findings were remnants from hunting quarry. They could be assigned to wild sheep and goats, gazelles, wild boars, deer, and aurochs, each appearing in different layers and thus giving the archaeologists important information about the diet and hunting habits of the earlier inhabitants of the region. They also provide information about climatic changes: apparently, dry steppe phases are followed by moister periods, with forests and forest dwellers, including wild boars and aurochs, being hunted.

The Neanderthal findings in the cave at the Wadi Dederiyeh are, along with the findings in the cave of Shanidar in Iraqi Kurdistan, the findings in Ksar Akil in Lebanon, the Behistun cave in Iran, and several findings in Israel, the only findings of Neanderthals in the Middle East and are thus among the oldest archaeological sites in the region testifying to human settlement.

The hills of Afrin belong to the region that that the U.S. archaeologist James Henry Breasted described as the “fertile crescent” at the beginning of the twentieth century. He was referring to the area north of the Syrian desert, in which, thanks to the winter rain, the Neolithic Revolution took place from the twelfth millennium BC on, turning hunter-gathers into tillers of the soil and breeders of cattle. Here people domesticated goats, sheep, and then cattle and pigs and began to cultivate barley, single-grain wheat, and emmer. And it was here that the first permanent human settlements and cities emerged.

Hurrians, Hittites, and Assyrians

Since around 3400 BC, at least the west of the Kurd Dagh region has been part of the sphere of influence of Alalakh, a Bronze Age city on the plain of Amuq in the Antakya/Hatay region, where the trade routes to Anatolia from Aleppo, Mesopotamia, and Palestine converged, and which today is part of Turkey. Even though the political history of this kingdom can as of yet be reconstructed only with difficulty because of the lack of sources, we can assume that the region of the Kurd Dagh was part of the narrower sphere of influence of this trading state.

The Hurrians were present in northern Mesopotamia by the end of the third millennium BC and started to expand to the west in 1800 BC, reaching the north of Syria and advancing into Israel in the process. In the fifteenth century BC, today’s region of Afrin fell under the influence of the Mittani Empire in the north of Mesopotamia, which ruled over a mixed population of Hurrians, Assyrians, Hittites, and Amorites until the mid-fourteenth century BC. Under the Great King Šuppiluliuma I, northwestern Syria was finally integrated into the Hittite Empire. The most important Hittite archaeological site in Afrin is Tal Ain Dara, where there have been findings dating back to the thirteenth century BC. Even after the Hittites, the city continued to play a key role, and it contains, among other things, a temple of the Mesopotamian goddess Ištar, who was venerated as the goddess of war and sexuality. Findings at this site date back to the Hellenistic time. On January 26, 2018, Tal Ain Dara, one of the archaeological sites with more than just regional importance, was attacked by the Turkish Air Force. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, 60 percent of the excavations were destroyed.[33] The Turkish military at first denied these accusations and claimed that it never attacked historical sites or buildings. But BBC film recordings made using a drone confirm the far-reaching destruction of the historical temple site.

For many Kurds from Afrin, the early settlement of the region from the north is of great significance for their national identity and represents an opportunity to dissociate themselves from the Arabs from the south. Even though there are no unequivocal indications of a historical continuity between the Anatolian population groups and today’s Kurds, in the twentieth century and in a region with increasingly ethnic and confessional conflict the reference to historical empires and population groups has become increasingly important. Different from many other Kurds who, citing the Russian Orientalist Vladimir Fedorovich Minorsky, trace their origins back to the Medes, among the Kurds in Afrin there is a tendency to refer back to the Hurrians, whose language is different from Kurdish and is not Indo-European but also does not belong to the Semitic language family shared by Assyrians and Arabs.

East of the Kurdish region of Afrin, near Tal Rifaat, in an area conquered by the SDF in 2016, is the site of what was probably once the most important town in Arpad, one of the central cities of the ninth century BC Aramaic Empire, Bit Agusi, a town that is also mentioned in three books of the Hebrew Bible.[34] Even though the connection of Arpad to Tal Rifaat is not confirmed with any certainty, it is reasonably clear that Afrin was also a part of this small Aramaic state. Between the ninth and the seventh centuries BC, the region was part of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and after the latter’s destruction by the Medes and Babylonians, Syria was absorbed into the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which was finally conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire in 539 BC.

Hellenism and Roman Empire

The conquest of the Achaemenid Empire by Alexander the Great, who was able to take over today’s Syria following the battle of Issus in the years 332 and 331 BC, was the beginning of the integration of Syria into the Hellenistic world. Under the rule of Alexander’s successors, the Seleucids, cultural influences from the Greek and Persian sphere mixed with the influence of the Aramaic-language populations of the Middle East, laying the foundation for a cultural development that continued under Roman rule. Some authors, such as the Syrian Kurdologist Ismet Chérif Vanly, place the immigration of Kurdish tribes into the Kurd Dagh region at this early date, tying it to the mercenaries employed by the Seleucids.[35]

Finally, the slow decline of the Seleucids in the second century BC led to the occupation of the region by the Armenian king Tigranes II (Tigranes the Great) in 83 BC, but he was expelled by the Romans in 69 BC. The Romans once again installed a Seleucid ruler as their vassal, before declaring Syria a Roman province in 63 BC. The seat of the procurator of the Roman province of Syria was the city of Antioch, which became one of the most important towns of the East Roman Empire and was located only twenty-five kilometers [fifteen miles] from the Kurd Dagh, where olives were already being grown at that time.

With the partition of the province of Syria, the hilly land of Afrin became part of the province Syria Phoenice. It continued to be the hinterland of the capital Antioch, which at the time was, along with Alexandria and Constantinople, the most important city of the eastern Mediterranean area. But the region around Antioch also became one of the earliest centers of Christianity in the Roman Empire. It is said that the first Christian community around Paul, Barnabas, and Petrus gathered in the Grotto of St. Peter in the northeast of Antioch, which has survived as a cave church until today. According to the Acts of the Apostles, Antioch was the place where non-Jews converted to Christianity for the first time,[36] as well as where the followers of Jesus began to call themselves “Christians” (Greek: Christianoi) for the first time.[37]

Christian and Islamic Rule

It was not just Antioch that belonged to the earliest Christian centers, the same was also true of its general surroundings. Thus, the hilly lands of the Kurd Dagh were already a key Christian refuge in the first centuries AD.

The region of Afrin is home to several archaeologically valuable early Christian ruins, among them the city of Cyrrhus, north of Afrin, the ruins of the monastery of St. Simon, and another site near Beradê in the south. As a part of the region that predominantly hosted Christian churches that were regarded as heretical and were in part persecuted by the imperial church after the ecclesiastical schisms at the Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, in 431 and 451, respectively, it was relatively easy for seventh-century Muslims to integrate the population—which nonetheless remained predominantly Christian for quite some time—into the Islamic Empire after the conquest of Syria under the caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar.

Under the rule of Caliph Umar, the region of Afrin was annexed to the Islamic Empire in 637. That was the year that a cavalry under the prophet’s companion Abū ‘Ubayda ‘Āmir b. ‘Abd Allāh b. al-Jarrāh of the Quraishiti clan of the Banū l-Hārith conquered the villages on the Cûmê plane, after which the town of Cyrrhus submitted to the Muslims without resistance following an agreement between the military leader and a priest in Cyrrhus.[38]

In the late eleventh century, today’s region of Afrin became part of the Antioch princedom created by the crusaders. The European crusaders used the former St. Simon monastery in the south of the region as a crusader castle for their—ultimately unsuccessful—attacks on Aleppo. However, more than a hundred years before the end of the princedom of Antioch in 1268, the region of Afrin had already been conquered by the Turkmen dynasty of the Zengids, under the leadership of ‘Imād ad-Dīn Zangī, who succeeded in seizing large swathes of Mesopotamia and Aleppo after the fall of Mosul in 1128.[39]

After the victory of Saladin, a Kurdish prince from what is now central Iraq, over the Zengids near the Horns of Hama in April 1175 and his conquest of A’zaz in June 1176, the Kurd Dagh region fell under his influence. In 1187, he would finally liberate Jerusalem, after which he founded the dynasty of the Ayyubids, which remained in power until the mid-thirteenth century. It was, however, only in May 1182 that Saladin was able to conquer Aleppo after a short siege, thus securing his power in the north of Syria, including the region of Afrin.

Rule of the Mendî under the Ayyubids and Mamluks

Given the lack of written sources, it is impossible to know with any certainty when Kurds started to settle Afrin. It is, however, clear that many Kurdish warriors came to Syria in the wake of Saladin, leading to the emergence of entire Kurdish neighborhoods in Aleppo and Damascus. It makes sense to also see the settlement of the Kurd Dagh by Kurdish tribes in this light, particularly because the retreat of the crusaders led to the emigration of a part of the Christian population in the region, and because the region had been very thinly settled under the rule of the crusaders. While some authors date the Kurdish immigration into the region as early as the time of the Seleucids in the second and third centuries BC,[40] the defeat of the crusaders and the establishment of the rule of Saladin is probably the latest possible point for the Kurdish immigration into today’s region of Afrin. It would also be a fair assumption that the partially depopulated former border regions that had been characterized for decades by the shifting front line separating crusaders and Muslims were again settled by Kurdish followers of Saladin, or that there was at least an additional influx. At any rate, by the late Middle Ages at the latest the hill land of Afrin was almost certainly characterized by a pronounced presence of the Kurds.

Under the Ayyubids, the Kurd Dagh region formed part of the princedom of the Mendî, which is also called the princedom of Kilis and A’zaz.[41] In the Sharafnāma, a chronicle of princes created by the Kurdish poet and historian Sharaf ud-Dīn Khān al-Bitlīsī in 1597, the claim is made that the dynasty of the Mendî was founded by two brothers, Şemsedîn and Behdîn, who had supposedly come to the region from Colemêrg (Turkish: Hakkari). The center of this Kurdish dynasty was the border town Kilis, which is now located in Turkey. But apart from today’s Afrin, the dynasty also ruled over the linguistically mixed regions further to the east around A’zaz, where there are Arab, Kurdish, and Turkmen villages to this very day. The Kurdish Mendî ruled over a religiously and linguistically diverse population that consisted of Muslims, Christians, Êzîdî, Alevi, and Jews who spoke Arabic, Kurdish, Armenian, and Turkish. At least parts of the tribe of the Mendî were Êzîdî.

This dynasty even outlasted the Mongol invasions. Thirteenth-and fourteenth-century records indicate that there were repeated conflicts between the region’s Muslim Mendî and the Êzîdî. Finally, the local Êzîdî sheikhs allied themselves with the Burji Mamluks then ruling in Egypt, a Circassian Mamluk dynasty that had taken power in Cairo in 1382. But the Mendî were still able to carry on as the local rulers in the region.

Even though Qasim Beğ, who at the time of Selim I was the local ruler of the Mendî and was thus also in control of the Kurd Dagh, allied himself with the rapidly expanding Ottoman rule, he was soon murdered on the orders of Selim.[42] His successor, Canpolat Beğ, who ruled from 1516 to his death in 1572, and whose rule is testified to by a mosque and Sufi-Tekke in Kilis, which was built by and named after him and exists to this day,[43] was able to safeguard the rule of his family in the Ottoman controlled region, ensuring that the Mendî remained the local rulers and the leading political force in the region, even under Ottoman rule.

Afrin in the Ottoman Empire

Beginning in 1516, after the defeat of the Burji Mamluks at the hands of the Ottomans, Syria became part of the Ottoman Empire. But here, at the fringes of the Empire, there was no uniform penetration of the territory by the new rulers. The Empire was primarily present in the towns and along the most important traffic routes, while peripheral areas increasingly assumed an independent existence under local rulers. Thus, in the sixteenth century, Druze emirs in today’s Lebanon acted in an increasingly autonomous fashion, with many of the areas settled by Kurds being autonomous princedoms or tribal areas only loosely connected to the center of the empire. In the Kurd Dagh region, the Mendî remained in power as Kurdish local princes under Ottoman suzerainty. Canpolat Beğ secured the influence of his dynasty until his death in 1572. In 1603, his successor Hussein defended Kilis and Aleppo against an uprising of the Janissaries, the elite Ottoman troops, and was rewarded for this with the office of Governor of Aleppo, although he would be executed shortly thereafter, in 1605.[44] In response to this, there was an uprising led by his nephew Ali Canpolat, who is often called Canpolatoğlu (son of Canpolat) in Turkish sources, who tried to establish independent rule in the region around Aleppo and Kilis, as well as in the Kurd Dagh. He managed to capture Aleppo but was ultimately defeated in 1607 and executed in 1611.[45] With Ali Canpolat, the last local ruler of Kilis from the Mendî dynasty died.

His descendants emigrated to today’s Lebanon and became an important noble family among the local Druze. The Jumblatts, who gave birth to the two most important Lebanese Druze politicians of the twentieth century, Kamal and Walid Jumblatt, are descendants of Canpolat Beğ. The family’s Kurdish descent is still known today both by Kurds and in Lebanon itself.

After the end of Mendî rule, their territory was integrated into the Eyâlet Aleppo, which had been in existence since 1534. With this, today’s region of Afrin came under the direct administration of an Ottoman province. In 1620, a Kurd from the Rubari lineage of the tribe of the Barwari was appointed as the local ruler of Kilis. After his dismissal or death, his descendants settled down in a castle in Basûtê, twelve kilometers [seven and a half miles] to the south of today’s city of Afrin, and ruled the Afrin River valley, with its fertile plain.[46]

In 1736, the clan of the Genc displaced the Rubari from Basûtê and established their rule over the Afrin valley, the heart of the region. In 1742, the family of Haj Omar from the tribe of the Raşwan assumed control over the Afrin valley, and eventually over Kilis until the Ottomans reintegrated the region into their own administrative system in a more direct fashion in 1866, incorporating it into the Vilâyet Aleppo, which had been founded in 1864 during the Tanzimat Reforms. Within the Vilâyet, Afrin formed a part of the Kaza of Kilis,[47] which in turn was part of the Sanjak of Aleppo.