The Renegade

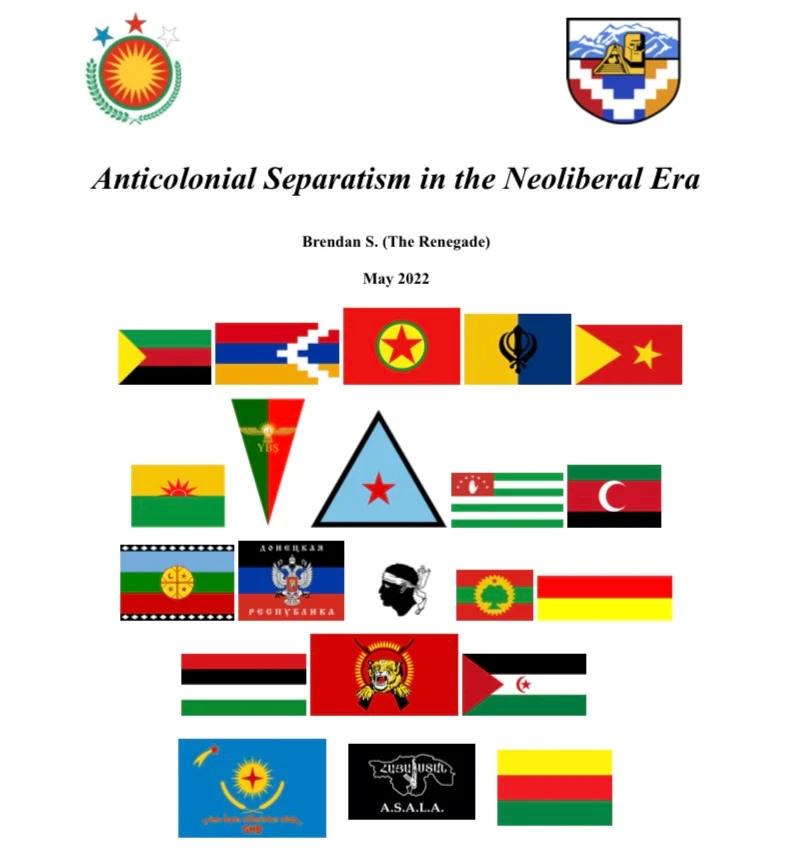

Anticolonial Separatism in the Neoliberal Era

Paramilitaries and Information Warfare

US State (and Corporate) Co-Optation

Framework of the Rojava Revolution

Flaws in the Democratic Confederalist Structure

Framework of the Artsakh Resistance

Political Structure of Artsakh

Rise of the Artsakh Defense Army

Fall of the Artsakh Defense Army

Addressing Human Rights Abuses

Armenian and Artsakhi Perspectives

Effects of Neoliberalism and the State

Navigating the Tide of Interference

Potential Problems in the Research

Abstract

In an era of concentrated capital, concentrated power, and deteriorating political conditions, separatism has yielded itself as a vehicle for marginalized populations to uplift themselves. Amid a wavering liberal international order, this thesis serves to provide a better understanding of how populations free themselves, and what challenges they face in doing so. From the question of what impacts the capability of separatist movements to secede in the neoliberal era, I argue that state coercion, state co-optation, and internal dynamics of a movement impact this capability to secede. I compare separatist movements with internally decentralized characteristics to those with internally centralized characteristics in how they respond to mutual challenges. The cases of decentralized Rojava in the Levant and centralized Artsakh in the Caucasus are closely observed and contrasted as movements that have resisted intersecting problems in the neoliberal era. I find answers to the question of why Artsakh collapsed while Rojava has not. Late-stage statism is also included in this thesis as a new theoretical approach to describe the pattern of an increasingly authoritarian international system.

Introduction

Since the 1970s, a wave of separatist movements has emerged across the international system in response to increasingly authoritarian governments, influxes of foreign corporations, and other problems imposed on marginalized populations. This wave has been described by some as an “ethnic explosion” which “blasted across the world” with marginalized populations mobilizing to free themselves from a deteriorating political environment, leading to the emergence of anticolonial separatist movements such as the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, Khalistan Liberation Force, Tigray People’s Liberation Front, and many others (Chandhoke, 2006, p. 1). This description of the “ethnic explosion” remains consistent, as many active separatist movements today either began mobilizing or resumed their armed struggle in this nascent stage of the neoliberal era. While these groups often differ in ideology, a common characteristic is their anticolonial tendencies, that is, an emphasis on resisting foreign control and subjugation (Dei & Asgharzadeh, 2001). A key distinction in their methods of resistance can be observed between movements that are centralized and movements that are decentralized (Graeber, 2007).

With some states perceiving these movements as exploitable proxy forces and other states perceiving them as threats to their power structures, states have attempted to coerce and co-opt anticolonial separatist movements in a myriad of ways. In some cases, backer states attempt to form a dependency by flooding the movement with aid or controlling it as a proxy, often reshaping its internal principles to accommodate this dependence (Heibach, 2021). Occupying states, on the other hand, attempt to diminish these movements into submission by enticing their represented population with increased political representation and dividing the population politically (Jesse & Williams, 2010).

How movements respond to these problems often determines their capability to accomplish secession. To examine the dynamic of recent anticolonial separatist movements, my thesis asks, what factors impact the capability of anticolonial separatist movements to secede in the neoliberal era? I argue that state coercion and co-optation along with the internal dynamics of a movement impact its capability to secede in the neoliberal era, and that decentralization leads to fewer challenges in seceding. I will look at how various movements have resisted problems imposed on them in attaining or failing to attain secession, as well as ideological frameworks that affect the sustainability of a movement.

Scholars, and certainly separatists themselves, have contributed to the discussion of how movements secede and the conditions that determine their fate in the neoliberal era. Looking at state involvement in a movement, some find dependence on state backers to affect the movement negatively by diminishing its original principles, as seen in the Southern Movement of Yemen (Heibach, 2021). Others point out that dependence on state backers can affect a movement positively, particularly in movements that are resisting oppression in post-Soviet regions (Aksenyonok, 2007). The theoretical debate of decentralization versus centralization is also a central point of conversation as it pertains to the function of anticolonial separatist movements.

I will compare decentralized movements to centralized movements and analyze how they have responded to various challenges. In looking at a decentralized movement, I will examine the Rojava revolution, as this is a prominent case of anticolonial separatism in the neoliberal era that displays a decentralized method of resistance. In observing a centralized movement, I will examine the Artsakh resistance, as this shows a movement operating from a different model of centralization that is more susceptible to challenges in the factors discussed. I will compare and contrast how these differing examples of separatist resistance interact with factors discussed in the literature review, and to what extent they have succeeded or failed at attaining secession.

Literature Review

Conceptualizing Separatism

For the purpose of this thesis, I contend that movements which are separatist in nature intend to create a separation of power from existing political structures, and that this can include autonomy within a state. Some scholars, such as Don Doyle (2010), suggest that movements seeking autonomy within a state are not separatist but rather reformist. Contrary to this assertion, autonomy within a state still counts as separation of power from an existing political structure. This debate is rooted in how one perceives the threshold for secession, or separation of power. Though separatism is most commonly associated with separation from a state, the term has also been argued by some scholars as pertaining to religious institutions as well (Bumsted, 1967). In this thesis, I refer particularly to separatist movements that wish to separate power from a state.

Furthermore, I contend that separatism and secessionism are interchangeable terms. This interpretation has also been contested. John Wood (1981) and Aleksandar Pavković (2015) assert that secessionism explicitly denotes separation from a state with the aim of creating a new one, whereas separatism more broadly advocates for reduced central authority over a population or territory. However, they agree with the interpretation that separatism can include autonomy within a state, and can be broadly applied to numerous forms of power separation. Separatist movements are therefore distinct from other forms of rebellion in that they aim to form a separate political structure, not necessarily replace an active government. The premises for separation are often characterized by a group’s differing ethnic, religious, or political values from that of a state’s ruling class. The act of secession is thus defined in this thesis as the creation of political autonomy separate from an existing state or institution’s power structures.

Anticolonialism

Following the suggested interpretation of George Dei and Alireza Asghardzadeh (2001): movements that are anticolonial in nature are those that, in their original principles, intend to resist oppression and control from foreign and external power structures. As described by Yatana Yamahata (2019), anticolonial movements should be “understood as a continuous political and epistemic project that extends beyond national liberation. They challenge the coloniality of power as well as shift the state-centric focus of decolonisation” (p. 4). The concept of anticolonialism can scarcely be discussed without the concept of decolonization as well. According to Dei and Asghardzadeh (2001), anticolonialism utilizes decolonization as a vehicle to expel colonial tendences in a given society, both social and political. Helen Tiffin (1995) argues that decolonization is a “process, not arrival; it invokes an on-going dialectic between hegemonic centrist systems and peripheral subversion of them” (p. 95). That is, anticolonialism includes objection to hegemonic structures that are attempting to colonize a population with its own social and cultural norms.

This interpretation challenges the traditional idea of colonialism, which strictly involves the migration of settlers into a colony. This traditional interpretation is employed by David McCullough (2015) for example, indicating colonialism to be a practice by settlers who “risked the dangers of settling new lands for reasons of faith” (p. 403). The interpretation of colonialism followed in this thesis is not strictly one of settler-colonialism, but one of social colonialism as well. As described by social ecologist thinker Cynthia Radding (1997), colonialism is a process that encompasses “social stratification along ethnic, class, gender, and income lines” imposed by the administering hegemonic power. It is a system that entails a myriad of social repercussions beyond the simple migration of colonists (Radding, 1997, p. 1). Thus, anticolonialism is the objection and resistance to these social repercussions of colonialism.

Lastly, I contend that anticolonial movements can be distinguished from extremist movements in that extremist movements are coercive in nature, attempting to forcefully subjugate or assimilate populations on the basis of an enforced hegemony, while anticolonial movements are not coercive in nature. Anticolonial movements may participate in isolated acts of coercion, but these acts are not supported by their official principles. Coercive extremist movements, as suggested by progressive thinkers such as Aijaz Ahmad (2008) and Geoff Eley (2016) of Socialist Register, may commonly fall under the label of “fascism.” This includes clerical fascism in movements like ISIS and al-Qaeda, which intend to destroy all secular influence by force, or social fascism of vanguard movements like the Sendero Luminoso of Peru, which intentionally massacred peasant populations to extend its power. Since the term “terrorism” is highly subjective and often abused for state narratives, I will not be using it to describe extremist movements.

Neoliberalism

At its foundations, many economists associate the neoliberal era with a transition from “Fordism” to a “post-Fordism” in the world economy. Mass production has become a global phenomenon where corporations and monopolies now have unprecedented international powers compared to the age of Fordism, where corporate power was more limited and trade barriers more prevalent (Miller, 2018). The philosophy of neoliberalism, which advocates oligopoly, decreased trade barriers, and rapid corporate expansion at the expense of labor rights, became a mainstream political doctrine in the nation-state system around the time of the 1973 Chilean coup that brought Western-backed neoliberal dictator Augusto Pinochet to power in Chile (Miller, 2018). The doctrine subsequently became a globalized policy during the Reagan and Thatcher administrations in the 1980s, definitively replacing the remnants of Fordism. This phenomenon is weaponized by states against marginalized populations and their separatist movements, with common state tactics including information warfare, state integration of the military-industrial complex, increased armament production, and commodification of weapons technology (Miller, 2018).

Within the topic of neoliberalism there is an extensive discussion on late-stage capitalism: the idea that capital becomes increasingly concentrated into the hands of fewer people over time and cannot sustain itself as a medium of human interaction (Targ, 2006)(Peck and Theodore, 2019). In conflicts involving separatism, one may find late-stage statism to run concurrent with the idea of late-stage capitalism. Thinkers such as David Graeber (2007), Harry Targ (2006), Jamie Peck and Nik Theodore (2019) theorize that UN-recognized nation-states grow increasingly authoritarian and autocratic as political power simultaneously shrinks into fewer and fewer structures. Like the capital which has developed them, these nation-states struggle to sustain themselves as legitimate mediums of human interaction. Growing exponentially illegitimate to populations marginalized by their power structures, nation-states and their megapoles resort to coercion and co-optation to suppress these populations (Targ, 2006)(Peck and Theodore, 2019). One can find examples of this in both cases studies observed in this thesis. Since there is not yet a term coined to describe this phenomenon, I describe it here as late-stage statism.

State Involvement

Coercion

States will often pursue separatist movements militarily in “counterinsurgency,” which military sciences scholar David Ucko (2012) defines as the “totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces” (p. 68). Counterinsurgency is a major doctrine discussed among military sciences communities in their approach to coercing separatist movements. Some counterinsurgency scholars go as far as advocating for aggression against civilian populations to contain separatist movements, which are often thrust into the ambiguous and dehumanizing “insurgent” label. Neoconservative-aligned military sciences scholar Daniel Levine (2009) maintains that “coercive measures aimed at population control are part of mainstream counterinsurgency strategy” and that restriction of civilian freedoms is “backed up with the threat of force” (p. 5).

Disarmament is also a common objective when it comes to state strategy in coercing separatist movements. Subcomandante Marcos (1998), a commander of the anticolonial Zapatistas movement in Mexico, points out in one of his dispatches that the Mexican state has ignored cartel and rogue paramilitary violence to focus on disarming his movement and prevent it from seceding.

Paramilitaries and Information Warfare

In the neoliberal era, state-backed paramilitary forces have emerged as an increasingly common instrument to suppress separatism. States will often arm domestic proxy forces so that conventional militaries and police forces do not have to confront the separatists directly. In one example, Ricardo Dominguez (2015) elucidates how the Mexican state has armed corporate paramilitary forces to combat Zapatista presence in Mexico. When disarmament of the Zapatistas failed, a state-backed paramilitary called Máscara Roja was armed with the purpose of combating the Zapatistas. Máscara Roja subsequently committed the Acteal massacre of 1997, slaughtering dozens of supposed Zapatista sympathizers (Dominguez, 2015).

This pattern of arming nonstate actors to coerce separatist movements has been widely observed across the nation-state system. In arming unregulated paramilitary forces, states coerce separatist movements by terrorizing local populations without having to take direct blame for it. As Frank Bovenkerk and Yücel Yeşilgöz (2004) illustrate, the Grey Wolves of Turkey, for example, have been armed by the Turkish state to suppress the Kurdistan Workers’ Party. This arming of the unregulated Grey Wolves paramilitary has, in turn, led to numerous massacres of civilian populations in Kurdistan. With the intentions of the state in this matter, however, it can be argued that regulation or lack of regulation for the paramilitaries may not make an ethical difference (Bovenkerk and Yeşilgöz, 2004).

Emma Sinclair-Webb (2013) indicates in her analysis of the Kuşkonar and Koçağılı massacres of 1994 that states have abused information warfare to carry out false flag narratives as well, blaming the separatist movement for actions it did not commit. When this false flag narrative is accepted among the general population, the movement is then confronted with a struggle of information warfare. This is particularly the case with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which has been subjected to a Turkish propaganda machine widely perceived as legitimate among the engaged Turkish population. Information warfare contributes substantially to the normative conflict between a separatist movement and its state adversaries, the state often making an intensive effort to disseminate and internationalize coercive norms.

The Megapole

The concept of the megapole is a key characteristic of the neoliberal era in its coercive response to separatism. Coined by Subcomandante Marcos (1997), a megapole is an alliance between the state and corporate sector intended to coerce (or co-opt) populations into submission via “destruction/depopulation” and subsequently “reconstruction/reorganization” to plant state and corporate authority in a region by force (p. 567). Indigenous populations are often most impacted by this neoliberal practice from the Mapuches of Chile to the Montagnards of Vietnam, subjected to renewed settler-colonialism in the wake of corporate expansionism. Subcomandante Marcos explains that “Megapoles reproduce themselves all over the planet,” being a natural tendency of hegemonies in the nation-state system. All megapoles are entwined with the global capitalist system in one way or another. Marcos knows best that his movement, the Zapatistas, has not only had to resist coercion from the Western megapole in the wake of NAFTA but also the co-optive incentives of dependence on Eastern megapoles such as those seen in the Belt and Road Initiative.

Co-Optation

While many separatist movements are faced with the challenge of external coercion by force from states, many are also faced with the erosion of their perceived legitimacy as a result of state co-optation. That is, when disgruntled populations are “transformed into supporters of the status quo” (p. 42) as a result of states satisfying the elite of that population, whether this be via bribery, political power, or social status (Jesse & Williams, 2010). The elite then disseminate this satisfaction to the population, causing armed dissent to be ostracized into an out-group of “radicalism” or “extremism” juxtaposed by a legitimized “moderate” bloc. The purpose of state co-optation is not necessarily to defeat separatist movements with hard power, but to diminish them with soft power.

Anti-separatist Max Boot (2013) argues that separatist movements are successfully contained in this manner, but with the help of extensive military involvement. Boot (2013) contends that state militaries must not focus “on chasing guerrillas, but on securing the local population” (p. 112). When this occurs in unison with state policy, he argues, separatist movements are effectively diminished. In other words, Boot believes that separatist movements cannot truly be dismantled without concerted state and military efforts to “win hearts and minds” as a co-optation strategy with the disaffected population (Boot, 2013, p. 112).

Federalization

Neera Chandhoke (2006), also in favor of containing separatism, proposes instead that federalization has acted as an effective deterrent. In federalization, the dissatisfied population is granted some form of representation in the political chambers of the state. Chandhoke (2006) concludes that providing dissatisfied groups with engagement in collective action erodes demands for sovereignty. The elite are co-opted, and in a manner that distracts the population in question from their own armed struggle, diverting their attention to state political chambers. However, Chandhoke (2006) warns that when a state centralizes, demands for sovereignty increase as the state’s hegemony absorbs regional decision-making. Using the Indian state as an example, with the absorption of regional governments under state administration, separatist movements in Kashmir, Punjab, and Assam have become more active as ethnic voices are denied in the political process (Chandhoke, 2006). This has been particularly prevalent during the Narendra Modi administration.

Dependence on Backers

Some scholars find that a movement’s dependence on a backing state or institution can affect it detrimentally. In one example, the Southern Movement of Yemen has become so dependent on support from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) that it “answer[s] directly to the Emirates,” its decision-making largely replaced by the backing government (Ardemagni, 2017, p. 2). As Eleonara Ardemagni (2017) points out, with the voices of local populations largely nullified in the administering process, the movement loses its legitimacy. The presence of foreign influence has also led to general discontent among local populations (Ardemagni, 2017). Jens Heibach (2021) suggests one of the purposes of UAE backing is to “usurp the Southern Movement’s secessionist demands,” manipulating its interests to best accommodate Emirati power in Yemen meanwhile diminishing the movement’s organic interests (p. 6).

Other scholars suggest that dependence on backers has been of considerable importance to separatist movements, particularly in the Russian sphere. Adding to the “ethnic explosion” of the 1970s and 1980s, the collapse of the Soviet Union injected yet another array of separatist movements into the international system. The Russian Federation has since been widely observed backing many of these separatist movements to secure its regional influence. Alexander Aksenyonok (2007) suggests that without Russian backing, ethnic groups like the Abkhaz are doomed to perpetual marginalization in UN-recognized nation-states. Following the collapse of the USSR, “unitary states were introduced by brute force” leading to “Smoldering interethnic conflicts flar[ing] up with new intensity when the central governments abolished the broad privileges that had been enjoyed by ethnic minorities…in a federal state” (Aksenyonok, 2007, ¶ 25). From this lens, it is argued that state backing of separatist movements is justified when it ensures the rights of marginalized ethnic groups.

Russian backing, Arsene Saparov (2014) argues, acts as a mechanism of conflict resolution for the Russian state, as the autonomy of these ethnic groups diminishes the responsibility of neighboring states to suppress their separatist movements. From this lens, dependence on a powerful backer is mutually beneficial for both the separatists and the occupying state. This relationship with the backer is not always cordial, however. Pål Kolstø (2019) argues that in spite of Russian dependence, Abkhazia has presented its autonomy by voicing dissent with various Russian policies. Though walking a thin line between Russian dependence and total collapse, Abkhazian civil society and government are not always compliant with the Russian Federation when it comes to making their autonomy clear.

Internal Dynamics

The internal dynamics and framework of a movement are fundamental in determining its capability to resist collapse and attain secession. In the neoliberal era, a dichotomy between decentralized and centralized movements comprises the bulk of all active anticolonial separatist movements. The way in which movements conduct and administer themselves often determines their longevity, and subsequently their fate. Decentralized movements generally have power distributed in a web of social bodies within the movement. This can take the form of a confederal system where local and regional councils are more powerful than the central governing body, as seen in the Rojava and Zapatista movements respectively (Dirik, 2018). Centralized movements, on the other hand, generally harness concentrated decision-making power in the hands of a small elite. This is often manifested in the form of a vanguard, or centralized party which operates a heavily hierarchic top-down command system beginning with the elite (Vanaik, 1986)(Kautsky, 1997).

Decentralization

Proponents of decentralized separatist models often argue that decentralization creates more elasticity and fluidity in a movement, preventing it from collapsing easily. In anticolonial movements, this line of thought usually follows indigenous, libertarian socialist, and anarchist models, but can also include interpretations of Marxism (Kautsky, 1997). Subcomandante Marcos (2003), a commander of the decentralized Zapatista movement of Chiapas, Mexico, proudly exclaimed in a letter to Basque separatists: “I shit on all the revolutionary vanguards of this planet.” Here Marcos separates the Zapatista model from the failed Marxist-Leninist movements of the 20th century which had collapsed upon the onset of the neoliberal era and the fall of the Soviet Union. Marcos (1998) explains how his movement, the Zapatistas, have been able to adapt to the neoliberal era by confronting it with decentralized power, taking a strictly anti-corporate and anti-colonial stance collectively, with the power of each community balanced equally in the movement.

Libertarian socialist thinker Naomi Klein (2002) adds that movements with less hierarchy are less isolated and more accessible to international solidarity. The success of the decentralized Zapatistas in creating autonomy in Chiapas in spite of coercion from state and corporate actors, she notes, “could not be written off as a narrow ‘ethnic’ or ‘local’ struggle” and instead “it was universal” (Klein, 2002, p. 4). Klein notes, “The traditional institutions that once organized citizens into neat, structured groups are all in decline: unions, religions, political parties” (p. 7). The broader phenomenon of decentralized anticolonial organization emerging organically “is not a movement for a single global government but a vision for an increasingly connected international network of very local initiatives, each built on direct democracy” she continues (Klein, 2002, p. 12).

This form of decentralized administration is also followed by the Rojava revolution in the Levant, which I will look closely at as a case study. Kurdish activist Dilar Dirik suggests that without this decentralized model of “stateless democracy,” the Rojava revolution would be unsustainable and vulnerable to collapse (Dirik, 2018). This lack of hierarchy, Dirik (2018) argues, has led to the movement’s success in keeping its power separated.

Decentralized separatist models are certainly not without critique, however. In fact, they have been criticized in the Marxist tradition for at least 150 years. During the formation of decentralized international models in the 19th century by Mikhail Bakunin and other decentralist members of the International Workingmen’s Association, Friedrich Engels (1872) notably adopted a hardline stance against decentralized rebellion of any kind, arguably exceeding any of Marx’s critiques. In his 1872 piece “On Authority,” Engels angrily insists that decentralists either “don’t know what they’re talking about, in which case they are creating nothing but confusion; or they do know, and in that case they are betraying the movement of the proletariat. In either case they serve the reaction” (Engels, 1872, ¶ 14). Since Marx’s and Engel’s expulsion of libertarian socialists and anarchists from the International Workingmen’s Association in September of that year, many Marxist thinkers have inherited this antagonizing approach to decentralization, particularly in Marxism-Leninism. This 150-year-old debate remains one of the most divisive in the Marxist tradition to this day. It is notably Eurocentric and tends to neglect decentralized indigenous models of resistance such as those seen in Kurdistan and Chiapas.

Centralization

Marxist-Leninist thinker Achin Vanaik (1986) argues that centralization in a movement is critical to opposing centralized institutions of oppression, particularly hegemonic states. “The bourgeois state is the vanguard organisation of bourgeois society, the most important bulwark defending the domain of ruling class oppression and exploitation,” he asserts, “Just as the bourgeois state must centralise the understandings and experiences of various segments of the oppressor classes the better to defend them, so too the revolutionary party must centralise the understandings and experiences of the various components of the oppressed and exploited classes the better to defend them” (p. 1640). This argument has been widely adopted by Marxist-Leninist thinkers in their approach to separatist movements, following the top-down model of centralized vanguards. Vanaik backs up his defense of vanguardism, in this sense, by alluding to the many Marxist-Leninist revolutions of the 20th century that successfully separated power from the “bourgeois state” (Vanaik, 1986).

Jayadeva Uyangoda (2005) discusses the centralized Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and its response to the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. He asserts that the hyper-centralized LTTE structure was able to enact disaster relief efforts far more effectively than the Sri Lankan state, which suffered from corruption and an ineffective bureaucracy. Because of its centralized efficiency, “the LTTE could immediately deploy its cadres and volunteers in the rescue and relief operations,” which in turn saved thousands of lives (pp. 10–11). The LTTE’s model of “humanitarian intervention from above,” Uyangoda argues, was so effective that it made the Sri Lankan state appear completely incapable of responding to disasters (Uyangoda, 2005). This use of centralization to provide efficient humanitarian and medical care can strengthen centralized movements and improve their legitimacy.

Stephen Day (2010) suggests that centralization in the Southern Movement of Yemen has helped it remain unified. The Yemeni state has been unable to divide southern tribes and pit them against one another because of their mutual loyalty to the top-down Southern Movement. Though now heavily influenced by the UAE, the Southern Movement was built from the foundations of the highly centralized state of South Yemen, which sustained sovereignty from 1967 to 1990. South Yemen “criminalized acts of tribal revenge, imposing law and order through an assertion of state power ” while “sheikhs lost their influence in society” (p. 7). With these centralized acts, a common cohesion and national unity was consolidated among the southern tribes. This unity through centralization, so to speak, is part of how the Southern Movement has been able to sustain its power among the southern tribes of Yemen to this day (Day, 2010). A similar dynamic can be observed in the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, which was recently able to separate its power from the Ethiopian state through a system of democratic centralism.

The centralist stance is heavily contested by decentralist separatist perspectives. Many point out that centralized movements have failed to withstand the neoliberal era, and have collapsed under the pressure of liberal institutionalism. The late anarchist thinker David Graeber (2007) points out how it has become increasingly rare for centralized vanguards to sustain “an alliance between a society’s least alienated and its most oppressed,” mentioning the contradictions between the centralized movement’s elite class and its general membership (ch. 9). The hierarchy of centralized movements has become increasingly perceived as ineffective and even a threat to human rights among critical theory thinkers. John Kautsky (1997), alluding to the many purges and massacres committed within centralized movements of the 20th century, notes that the vanguard relies on “mass persuasion, mass regimentation and mass terror” to attain and sustain power (p. 379). Kautsky echoes the sentiment of his grandfather Karl Kautsky, a renowned anti-Bolshevik Marxist thinker.

Lenin (1917) asserted in The State and Revolution that the “democratic republic is the best possible political shell for capitalism,” while insisting that the proletarian state is at the opposite end of this binary. Kurdish revolutionary Abdullah Ocalan (2012) counters this idea by asserting that the state in itself is a shell of capitalism, and thus any movement attempting to achieve a state of its own will inevitably succumb to capitalism or collapse altogether, as seen with the Soviet Union. Ocalan contends that no matter how much a centralized statist movement wants to run away from capitalism, it will never be capable of separating itself unless it dismantles hierarchy beginning at the community level (Ocalan, 2012).

Centralization relies on vertical (top-down) structures, while decentralization relies on horizontal (bottom-up) structures. This discussion also intersects with the concept of conventionality. Armies and militaries of UN-recognized nation-states are near universally centralized top-down structures, a model normalized in recent centuries to the degree it has been deemed the “conventional” or “regular” military model (Kilcullen, 2019). This model is juxtaposed by “unconventional,” “irregular,” “asymmetric,” or “guerilla” actors, which are often structured asymmetrically or horizontally in a manner that attempts to subvert larger conventional forces with fewer resources at their disposal. Conventional forces are almost universally centralized whereas unconventional forces are sometimes decentralized. These terms are accompanied by “conventional warfare” when two conventional forces wage war, and “unconventional warfare” when an unconventional actor is involved (Kilcullen, 2019). Conventional militaries often struggle to confront unconventional forces on the battlefield with conventional tactics. Some separatist movements which begin unconventional attempt to transition to conventionality once a separation of power has been attained. This can be seen in the case of Artsakh.

The Discussion

In sum, scholars and separatists alike have many contradicting ideas as to what impacts the capability of a movement to secede in the neoliberal era. Beginning with the meaning of separatism itself and anticolonial tendencies within the separatist umbrella, there exists no universal consensus on this sensitive topic. Some find state coercion and counterinsurgency to be an important determinant, coupled with information warfare and corporate alliances as symptoms of the neoliberal era. Others find state co-optation to be a strong deterrent of separatist power and influence. Regarding the internal dynamics and ideological framework of a movement, debate is largely split between the concepts of centralization and decentralization. Marxist and neo-Marxist thinkers predominate this debate on internal dynamics when it pertains to anticolonial movements.

Methodology

I will now address my argument that state coercion and co-optation impact the capability of an anticolonial separatist movement to secede in the neoliberal era as well as a movement’s internal dynamics and ideological framework, with decentralized movements possessing a greater capability to secede. To address my argument, I will analyze one example of a decentralized movement and one example of a centralized movement in how they relate to the factors discussed, then compare and contrast how these movements have interacted with these factors.

I will look at the Rojava revolution, a decentralized movement attempting to create sovereignty in Northern Syria. I chose the Rojava revolution because it is a recent example of a largely successful anticolonial separatist movement which has achieved a significant degree of power separation, with its success largely owed to its internal renewability. I will illustrate how the movement has been able to adapt to state coercion while resisting co-optation, and discuss how its internal characteristics have structured the movement’s integrity. Attempts from foreign corporations to infiltrate the economy of Rojava will be examined, as they correlate with Western attempts to co-opt Rojava alongside an increasingly corporatized neoliberal era.

I will also look at the Artsakh resistance, a centralized movement attempting to create sovereignty in the disputed region of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh). I chose this movement because it is a recent example of a movement that has been directly impacted by many of the factors discussed and consequently faltered. I will address how overdependence on the Armenian state, conventionalization of its armed forces, internal rigidity, and other factors have contributed to the collapse of the Artsakh resistance. The increasingly authoritarian nature of the Azerbaijani state will also be briefly discussed in how this relates to its coercion of Artsakh, as this pertains to the temporal dynamics of the neoliberal era at large. I will relay how the factors discussed have impacted the movement’s status and observe how much the movement has achieved in its objective of secession, along with how much it has changed with the factors in mind.

Lastly, I will compare and contrast these movements in how they have been capable or incapable of achieving secession. Some questions considered will be: What are some mutual factors that can be observed in both the Rojava revolution and Artsakh resistance? How has Rojava survived multiple invasions while Artsakh collapsed after one invasion? What have been the determinant factors leading to the success or failure of the movements in achieving secession? This comparison will aid my argument and conclusion, displaying how state involvement and internal dynamics have heavily impacted both movements in their capability to secede, the decentralized movement generally reacting positively to the factors discussed and the centralized movement generally reacting negatively.

Rojava

Contextualizing Rojava

Rojava (meaning “west” or “land where the sun sets” in Kurdish) also known as Gozarto in Assyrian, is a region within the UN-recognized borders of Syria that has broken off from the Syrian state and maintained its autonomy since 2013. The region is often referred to as “Northern Syria” given that its territory comprises most Syrian-claimed land north of the Euphrates River. Rojava’s governing administration is officially called the “Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria,” although many non-Arab inhabitants do not claim the region to be Syrian. One may notice Kurdish inhabitants sometimes calling the region “Syrian-occupied Kurdistan” and Assyrian inhabitants calling it “Syrian-occupied Gozarto” given the fact it is still recognized as part of Syria to the international system (Kurdistanipeople, 2020)(Hosseini, 2016). Regardless of the semantics one prefers, Rojava lays at a crossroads of social and political metamorphosis in West Asia. A homeland of numerous ethnic groups and communities that have been marginalized by states and empires alike, many find the autonomous region to act as an oasis of refuge and egalitarianism, complemented by its stateless direct democratic political structures. This oasis did not emerge out of nowhere, however. Tens of thousands of Rojava’s inhabitants and dozens of foreign volunteers have been martyred while creating this oasis in a resistance known as the Rojava revolution (RIC, 2020a).

The foundations of the Rojava revolution can be traced back to the establishment of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in 1978 by Kurdish revolutionary Abdullah Ocalan. In response to the Turkish state’s authoritarian and discriminatory policies against the Kurdish people, Ocalan formed the first major revolutionary movement in Kurdistan aimed at liberating the Kurdish nation from the nation-states imposed on it. In 1984, the PKK took up arms and mobilized against the Turkish state, hoping to achieve a separation of power. The movement would soon expand into Iraqi-occupied Kurdistan, Iranian-occupied Kurdistan, and Syrian-occupied Kurdistan, becoming a legitimate regional power with millions of members and supporters (Ocalan, 2017).

Though the PKK began as a centralized vanguard with Marxist-Leninist tendencies, it would take an ideological U-turn following Ocalan’s arrest in 1999. Influenced by libertarian socialist thinkers such as Murray Bookchin, Ocalan removed his emphasis on the creation of a Kurdish nation-state, instead emphasizing the liberation of all marginalized communities in West Asia. This abrupt change of pace led the movement into a period of internal dialogue and restructuring. In 2011, Ocalan published his keystone piece Democratic Confederalism, where he called for the movement’s unitary structures to be entirely discarded and replaced by a decentralized web of councils under a stateless and decentralized political system known as Democratic Confederalism. Women’s liberation became a centrifugal doctrine upon this restructuring, and intersectional dialogue led the movement to question its original objective of simply replacing occupying states with another state (Ocalan, 2012)(Hosseini, 2016). With the exception of hardline Marxist-Leninists, many followers of Ocalan approved of the movement’s transition, and his new model would soon become a widely respected international blueprint via the Rojava revolution.

Just south of the UN-recognized Turkish border, the Rojava revolution was born out of this internal dialogue and fundamental transition to decentralization in the PKK, coinciding with a conflagration of grievances against the Syrian state in the early 2010s. The model of Democratic Confederalism materialized in Rojava largely due to the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM) and its predecessors, a progressive coalition in Rojava influenced by Ocalan and the PKK. After decades of Baathist rule, Syria’s marginalized communities were looking to put an end to Arab hegemony, which had been fused into the state following the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement and 1923 Lausanne Treaty that created Syria’s modern borders. Beginning in 1962, hundreds of thousands of non-Arabs were stripped of their citizenship and subjected to ethnic cleansing policies that hoped to create an “Arab belt” in their ancestral homeland (RIC, 2020a). Syria’s colonial legacy led the state into an authoritarian spiral under the Assad dynasty. Many in the marginalized Yazidi, Armenian, Circassian, Assyrian, and Kurdish communities of Rojava found TEV-DEM to be the most suitable candidate for the desired abolition of Syrian statism, calling for a complete subversion and overhaul of the Syrian power structures.

TEV-DEM embraced the PKK’s ideological transition and adopted the new model of Democratic Confederalism. The movement was given its first opportunity to implement this model in the wake of the Arab Spring. Upon the onset of the Syrian Civil War in mid-2012, the Syrian Arab Army withdrew from the north to confront rebelling militias of the Free Syrian Army to the south and west. This allowed TEV-DEM to secure autonomy in the north with a confederation of councils, communes, and cooperatives (Hosseini, 2016). The following year, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) declared its separation of power from the Syrian state representing one collective Rojava free of colonial structures, and constructed the first complete governing model of Democratic Confederalism. Rojava has since faced an invasion from ISIS and three invasions from the Turkish state and its allied militias, compounded by sporadic fighting with the Syrian state. Rojava has also resisted attempted co-optation from the US and other actors (RIC, 2020b). Despite losing part of its territory in the process, the decentralized administration of Rojava remains completely intact and has not been altered. The region is defended by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which is a coalition of progressive militias led by the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ).

The Rojava revolution is a separatist movement in that it aims to separate its power from the Syrian state, and it has achieved this. Rojava was born out of resistance to the oppressive colonial structures of the Syrian and Turkish states, forging its political model around ensuring colonial structures are never present in the region again. Thus, Rojava is anticolonial in every connotation of the term. The movement has also resisted many components of the neoliberal era that shall be discussed, such as corporate opportunism, drone warfare, information warfare, and the megapoles which drive them.

State Coercion of Rojava

It is without question that the Rojava revolution has been afflicted with an onslaught of state coercion intending to limit its capability to remain seceded and autonomous. Though ISIS has coerced Rojava to a significant degree, it will not be included in this section since ISIS is not a nation-state nor is it internationally recognized. The UN-recognized nation-states of Syria and Turkey will be observed here in their coercion of Rojava and intent to extinguish its separation of power, as well as their crimes against Rojava’s population.

Syrian State Coercion

Beginning with the Syrian state, the Baathist power structure of Syria under the Assad dynasty hopes to expand its megapole into Rojava after losing occupation of the region in 2012. Though an unstable ceasefire has been in effect between Syria and Rojava since August 2015, it has been made clear that the Syrian state finds Rojava’s separation of power illegitimate (AJ, 2015). Military force has been used against Rojava by both the Syrian Arab Army and its allied paramilitaries, backed with support from the Russian megapole and military-industrial complex.

The Syrian state has armed paramilitary actors to coerce Rojava, such as the National Defense Forces (NDF). Two major battles have occurred between the NDF and SDF in the city of Hasakah after the paramilitary attempted to expand its occupation in Rojava, the first in August 2016 and the second in January 2022. Both occasions resulted in loss of territory for the NDF. Battles and skirmishes have also occurred in Deir ez-Zor region, particularly around Khsham (The Renegade, 2021). Syrian state backing of the NDF and its direct support from the Syrian Arab Army have proven problematic for Rojava, though not as dire a threat as the Turkish state.

Information warfare is also a key piece of the Syrian state’s coercion

of Rojava. Antagonization of Rojava disseminated largely through the

state-run Syrian Arab News Agency

(SANA) can be observed, describing the Syrian Democratic Forces as “Kurd

militants” and frequently spreading claims accusing Rojava of crimes

there is no evidence for (SANA, 2020). The Syrian Ministry of

Information has developed and expanded its operations significantly

throughout the neoliberal era to accommodate social media and digital

information, especially during the Syrian Civil War. The Syrian state’s

information warfare has seen productive results regarding international

support bases, drawing in newfound support from many authoritarian

communities on the left and right alike. A network of front agencies

oversee the international dissemination of pro-Assad information, all

connected to a transnational organization calling itself the “Syrian

Solidarity Movement” (Davis, 2019). In this sense, globalization in the

neoliberal era has allowed the Syrian state to further internationalize

its efforts in information warfare.

Turkish State Coercion

Since the attempted 2016 coup in Turkey, the Turkish state has reached its authoritarian zenith in the era of late-stage statism and neoliberalism. A Justice and Development Party ruling class led by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has become determined to consolidate its power and externalize Turkey’s domestic issues. In this process, the Turkish military-industrial complex has become further entwined with the government, resulting in a highly imperialist megapole. This megapole happens to be a NATO power with a military backed by Western tax money.

Unlike the Syrian state, the Turkish state is direct, forceful, and overt in its attempts to coerce Rojava, making heavy use of counterinsurgency in its strategy to eliminate Rojava’s autonomy and replace it with Turkish occupation. The Turkish state has brutally enforced population control in its three invasions of Rojava: the invasion of northern Aleppo region in 2016, invasion of Afrin 2018, and invasion of Serekaniye in 2019 (RIC, 2020a)(RIC, 2020b). This counterinsurgency operation has been brutal and devastating to the entire region, and may even classify as genocide. Aggression against civilians has proven a major component of the Turkish state’s plan to subjugate Rojava’s population under the guise of counterinsurgency. The Turkish state has also directed its megapole toward Rojava, evidently fixated on destroying the region.

(Trigger warning: sexual violence) According to data collected by the Missing Afrin Women Project between January 2018 and June 2021, 170 women were confirmed kidnapped by Turkish forces and SNA proxy militias, dozens of these women forced into sex slavery and many of them minors (Missing Afrin Women Project, 2021). Given heavily enforced censorship under Turkish occupation, the actual number is likely much higher. Mass rape and kidnappings have continued following this collection of data, and some estimates put the figure at over 1,000 victims (Bianet, 2021). During the invasion of Afrin, some estimates convey that 80% of olive trees grown by Kurdish farmers were either burned or stolen by Turkish forces and relocated to Turkey, eliminating the livelihoods of the farmers while leading them and their families into starvation (ANF, 2018). According to Saleh Ibo, a representative of the Afrin Agricultural Council in 2018:

“The most beautiful canton in Northern Syria used to be Afrin, it was known for it. It was a rich canton with its nature, culture and economy. That is why the invading Turkish state targeted Afrin quite deliberately… The invading Turkish state targeted Afrin’s forest areas in April in particular. Many trees, including olive trees, were burned. The invaders first stole 20 tonnes of Afrin’s wheat and took it to Turkey in front of the whole world to see. They bought from a very limited group of people. We as the Agricultural Council did a study that shows that the Turkish state bought produce from Afrin at 25% of what would have been an acceptable market price. Farmers and producers can’t survive like this. But they confiscated most of the wheat illegitimately in any case” (ANF, 2018).

These crimes against Rojava’s population were exacerbated around the Turkish state’s second invasion in 2019, which targeted the cities of Serekaniye and Gire Spi. Prior to the invasion, the Turkish state had committed mass arson on Rojava’s crop fields, wiping out multiple seasons of crop yields and rendering the land fallow from Raqqa to Hasakah regions. In committing this egregious crime against humanity, the Turkish state attempted to weaken Rojava by starving its population and sending it into a period of severe famine. This act of state arson was corroborated by a video captured at the border showing a Turkish soldier deliberately setting a field on fire (Pressenza, 2019).

Despite sending Rojava into famine, the Turkish state failed to defeat the SDF and was forced to halt its offensive in November 2019. It did not stop coercing Rojava, however. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the Turkish state then weaponized water against the people of Rojava by shutting down Alouk Water Station near Serekaniye, cutting off water access to nearly 500,000 people. This left a large portion of Rojava along with its medical facilities without water, resulting in a sudden lack of resources to combat Covid. A spike in Covid along with a worsening famine across Rojava followed, killing many people (HRW, 2020). The Turkish state’s deliberate destruction of Rojava’s basic life necessities, intended to send the Kurdish, Yazidi, Assyrian, and Armenian populations into famine, has been described by many as an act of genocide. Deliberate widespread destruction of sacred historical sites by Turkish forces and allies has been cited in this discussion of genocide as well (NPA, 2021).

The Turkish state has armed many paramilitary groups to complement its aggression against the population of Rojava. In 2017, the Turkish state founded the Syrian National Army (SNA) to aggregate its coalition of proxy militias. The Turkish state has exported units of the SNA abroad to fight as a proxy force, primarily to Libya and Azerbaijan. Presence of Turkish-backed mercenary militias abroad has added complications to peace processes and stalled negotiations, especially in Libya. Turkish state-backed paramilitary efforts against Rojava do not end at the SNA, however. Turkish National Intelligence Organization-backed armed cells have been discovered and captured within the territory of Rojava (ANHA, 2020).

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and artificial intelligence are military characteristics of the neoliberal era which have added a major source of revenue and power for military-industrial complexes across the world, the Turkish state one of the most prominent examples of this. Since the introduction of the Bayraktar drone family in 2005, drones have become the centerpiece of the Turkish military-industrial complex at the expense of Rojava’s population and many other communities in the Global South who have been the recipients of Turkish drone attacks, from Tigray to Artsakh. Since the Turkish state’s first invasion of Rojava in 2016, Bayraktar drones have killed hundreds of civilians in Rojava and probably thousands across the world, though the ever-increasing number may never be known (Feroz, 2016). The Turkish state is able to use drones as a method of population control in areas it does not occupy militarily, striking fear into civilian populations through artificial aerial terror.

Normatively, the Turkish state bears a neo-Ottoman education system which indoctrinates its students with anti-Kurdish and anti-Armenian curriculum, sharing many of the same characteristics of the Azerbaijani state’s system. Supported by a media network of state-sponsored channels of information, Turkish education widely desensitizes the population to state crimes, and is particularly problematic due to the Turkish state’s expanding regional power.

Thus, information warfare is a fundamental component of the Turkish state’s coercion in Rojava. Many attacks which occur in Turkish-occupied territory are immediately blamed on the SDF and PKK without any investigation, even when they are later found to be committed by ISIS or a result of infighting within the SNA. Kurds, Yazidis, Assyrians, Armenians, and all of Rojava’s communities are frequently described as “terrorists” by the Turkish state, fueling severely racist and violent currents of Turkish nationalism which span across not only Anatolia but also the Turkish diaspora internationally (Baghdassarian and Zadah, 2021). Misinformation is often abused as a device to divert international attention from Turkish war crimes.

Being a NATO member, the Turkish state’s claims are often perceived as more credible than Rojava’s, creating a perpetual funnel of misinformation to Western states, human rights organizations, and even the UN. The Turkish invasions were endorsed by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenburg, who did not condemn the Turkish state but rather condemned dissent within NATO against the Turkish state’s actions. Stoltenburg stated in 2018 during the invasion of Afrin: “All nations have the right to defend themselves…Turkey is one of the NATO nations that suffers most from terrorism” (Daily Sabah, 2018). He stated in 2019 during the invasion of Serekaniye: “Turkey is important for NATO…We have used, as NATO allies, the global coalition, all of us have used infrastructure in Turkey, bases in Turkey in our operations to defeat Daesh (ISIS). And that’s exactly one of the reasons why I’m concerned about what is going on now. Because we risk undermining the unity we need in the fight against Daesh” (Reuters, 2019) In these statements, Stoltenburg diverts attention from the unilateral nature of the Turkish invasion, instead falsely claiming it to be a matter of Turkish national security against terrorism and a matter of collective security. With this, Stoltenburg aligns with Turkish state information warfare to keep the Turkish state’s image permissible within NATO. In April 2021, the Biden administration renewed a $5 million bounty on PKK leaders, also exhibiting its alignment with Turkish state information warfare (US Dept. of State, 2021).

State Co-Optation of Rojava

Syrian State Co-Optation

In the midst of late-stage statism, the Syrian state has also reached its peak of authoritarianism, which manifested in the Syrian Civil War. The Syrian state does not dedicate much effort to securing the “hearts and minds” of Rojava’s population because it has antagonized them both in policy and military force for decades. Resentment toward the Syrian state in the region accumulated and festered over decades of repression, culminating in the 2004 Qamishli massacre. Legitimacy of the Syrian state is particularly scarce north of the Euphrates River, being the most marginalized region. With this in mind, the Syrian state has prevented itself from securing sympathy from most of Rojava’s population.

Syrian forces have been present in various pockets of Rojava and along the Turkish border as part of an agreement made during the 2019 invasion of Serekaniye. The agreement allows the Syrian Arab Army into some regions, but not any new Syrian state administration, keeping Rojava’s autonomy unscathed. The Syrian state practices what has been dubbed “hamburger trick diplomacy,” where relations are dropped once the Syrian state has extracted the most out of these relations it can, metaphorically resembling a trick where the meat of a hamburger is attached to a string then removed so that a customer receives only the bun (McKay, 2018). Many Rojavayîs have demonstrated their distrust for the Syrian state, its manipulation of crises to expand power, and drawing of the Russian military into Rojava (Rudaw, 2020).

Nonetheless, the Syrian state has occasionally shown signs of willingness to negotiate with Rojava. Negotiations for Syrian-recognized autonomy for Rojava reached a high point in 2015, but have since been stalled. Syrian state policy on Rojava became particularly inconsistent following the resignation of Syrian State Minister for National Reconciliation Affairs Ali Haidar in 2018 (Belewi, 2015)(Rudaw, 2022). Federalization has been on the table for the Syrian peace process, although this becomes complicated with Rojava’s insistence on autonomy and the Turkish state’s insistence on excluding Rojava from any Syrian peace process. The Russian state has advocated for including Rojava in the Syrian peace process, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov stating that the “experience of Iraqi Kurds should be passed on to Syria,” alluding to the federalized autonomy of the Kurdistan Regional Government within the Iraqi state (Rudaw, 2022). The Syrian state has remained reluctant, however, satisfied with Rojava’s complete exclusion from the Syrian Constitutional Committee.

Russian State Co-Optation

The Russian state has taken advantage of its alliance with the Syrian state to have a military presence in Rojava, being a party in many agreements made between Rojava and the Syrian state. The Russian state has been the most important ally to the Syrian state under the Assad dynasty for decades, but particularly since the beginning of the Syrian Civil War.

With clear consent from NATO on the Turkish invasions and US policy yielding to this consent, Rojava has been forced to gravitate away from its military partnership with the US Coalition in the direction of Russian backing. That said, relations between President Putin and the Rojava administration have waxed and waned depending on convenience to Russian state interests. Putin believes the territorial integrity of Syria should be respected under the unitary Assad regime. Nonetheless, he has demonstrated favorability of Rojavayî autonomy over Turkish occupation in his foreign policy (Rudaw, 2022).

In October 2019, the Russian state agreed to conduct joint-patrols with the Turkish military in the wake of the US withdrawal from the border, yielding a deterrence mechanism for further Turkish encroachment and helping end of the Turkish invasion of Serekaniye. In October 2021, the Russian state effectively established a no-fly zone over Rojava by repositioning a squadron to Qamishli Airport (Newdick, 2021). The Russian Armed Forces have frequently mediated ceasefire negotiations following clashes between the SDF and Syrian forces north of the Euphrates. Though this mediation cannot alleviate the ideological tension between Rojava and Syria, it has led to swift de-escalation of armed confrontation on numerous occasions. With the Russian state now a normalized mediator in tensions between the Syrian state and Rojava, it can be argued that the Russian state has co-opted Rojava diplomatically to the extent its mediation is deemed legitimate to the Autonomous Administration.

The Russian state’s presence in Rojava comes with many layers of nuance. Though the Russian state acts unilaterally in its support of the Syrian state, its interests in countering Turkish power have intersected with Rojava’s interests just enough to not have an antagonizational relationship. Nonetheless, many residents of Rojava have expressed their dissatisfaction with the Russian state’s presence by confronting patrols and protesting, finding the Russian state to be manipulative and opportunistic (Rudaw, 2020). In one noteworthy example in December 2020, citizens of Ain Diwar village in Hasakah region confronted a Russian patrol. A man stated to the Russians: “Throughout Syrian history, your presence has been for your own benefit.” One woman said to the Russian Army translator: “We are the people of this area. How much money have you received?” to which the translator responded, “I get a lot.” The woman replied, “We get honor…You should respect yourselves and go back to your country” (Rudaw, 2020).

Though the Russian state has indirectly backed Rojava through its agreements with the Syrian state, the Russian state does not enjoy nearly as much legitimacy in Rojava as it does in Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Donetsk, and other separatist regions it has backed. Mutual interests in deterring the Turkish state create a mutually beneficial relationship with the Russian state, but also one that enables an unwelcome Russian military-industrial complex driven megapole in the region. In the words of SDF commander Mazloum Abdi: “If we have to choose between compromise and genocide, we will choose our people” (Abdi, 2019). Enabling of Russian military presence in Rojava is certainly a compromise, but one that may be necessary to prevent genocide at the hands of the Turkish state.

US State (and Corporate) Co-Optation

In 2014, the Autonomous Administration accepted a military partnership with the Pentagon and a coalition of Western militaries to help defeat ISIS, a partnership which continues today consisting of training, arms supply, and logistics. The Autonomous Administration has maintained its separation from the US Coalition at an arm’s length so to speak, refusing Western encroachment on the economy or civil society and keeping the partnership limited solely to military backing. In October 2019, the US Coalition encouraged the SDF to disarm and demilitarize its northern borders following a supposed ceasefire agreement with the Turkish state. This immediately led to the Turkish invasion of Serekaniye and subsequent heinous crimes against humanity committed in it. In this sense, the US abused co-optation to subtly coerce Rojava simultaneously through disarmament, favoring its NATO ally in the Turkish state over the livelihoods of millions. The US has also subtly coerced Rojava by arming the Turkish military with vehicles and weapons, which have subsequently been used against Rojava. US-made and US taxpayer-funded bombs are found frequently falling on the soil of Rojava, killing workers, children, and families completely uninvolved in the conflict. The US arming of the Turkish military and withdrawal of US forces have been widely perceived as a major backstab to the people of Rojava and the Autonomous Administration (The Renegade, 2022).

Unlike the Russian megapole in Rojava which is limited to its military-industrial complex, the US has attempted to expand its megapole in Rojava to include Western corporations and extraction of natural resources. “I like oil. We’re keeping the oil,” President Trump told the press in November 2019 after his agreement to allow the Turkish state to invade Rojava. (Global News, 2019). In April 2020, Delaware-based oil firm Delta Crescent LLC was granted a one-year sanctions waiver to “advise and assist” oil production in Rojava, a waiver which remained untouched by the Biden-appointed US Department of the Treasury until its expiration (Rosen, 2021). Delta Crescent LLC then infiltrated Rojava without full consent of the Autonomous Administration, only a few officials within it. Tasked with refining oil from Rojava’s oil fields and exporting it, Delta Crescent LLC failed to gain local support and its operation crashed in the face of resentment from Rojava’s population, only able to hire a meager total of 10 employees. The Autonomous Administration dismissed the corporation as soon as its sanctions waiver expired. A worker from Qamishli named Ahmed Saeed commented on the development: “They will pump oil and steal it amid this famine. They will not work in the interest of the country…Nobody understands them, the Americans. They have been here for years, what has changed? When the Americans go somewhere, they work for their own interests, not the people’s” (Rosen, 2021).

Weaponizing corporations for foreign-direct investment amid crises to extract from local economies is a common neoliberal characteristic of US foreign policy which has been observed most extensively since the Reagan administration. Though attempted infiltration of Rojava’s economy was initiated under the Trump administration, policy between the Trump and Biden administrations on Rojava remained largely unchanged. Both administrations enabled attempts to occupy the oil sector and failed to do so because of both the population’s and Autonomous Administration’s refusal to feed the US megapole (The Renegade, 2022).

With these facets of co-optation in mind, the US Coalition presence in Rojava is likewise met with wariness from Rojava’s population due to its display of opportunistic co-optation and betrayal. Protests have been organized against the presence of US forces, often involving stone or potato-throwing and blocking of patrols (AP, 2019). Mazloum Abdi’s words of “If we have to choose between compromise and genocide, we will choose our people” most certainly apply to Rojava’s military partnership with the US Coalition as well, a compromise seen as a military necessity to expedite the collapse of ISIS, but not one that can ever damage Rojava’s self-sufficiency (Abdi, 2019). Firat, a former fighter in the SDF who fought ISIS, believes ISIS would have been defeated by the SDF without US military backing, and that it “just would have taken longer” (Firat, 2020–2021). This sentiment has been echoed by many in the SDF.

I asked a member of Asayish (Rojava’s security force) who shall be called Mahmoud: Do you believe Rojava is overdependent on any of its backers or allies, from the US to the PKK?

Mahmoud replied:

“Rojava in her current government, what it would take to get to the shape it is now without the PKK seed and the US air support and coverage—I don’t think the issue has become related to Kurdistan or the Kurds, it is related to a Kurdish party. If the Kurds abandon it (Rojava), they will be killed and displaced whether by the regime or the Turks. So the PKK is not a supporter but a founder, and the US can be shaped as a friend with benefits” (Mahmoud, 2022).

I found this description of the US as a “friend with benefits” to be comical yet precise. The US Coalition is a military partner for selective military tasks, but not political ones, and certainly not ones that infiltrate the social psyche of Rojava. From Mahmoud’s standpoint, the military partnership is necessary so that less Kurds die, but it does not mean that Rojava has become controlled by or dependent on the partnership (Mahmoud, 2022).

Framework of the Rojava Revolution

Having survived numerous brutal onslaughts of coercion from very powerful state and nonstate actors that would render most regional societies collapsed, one must question where the structural resolve of Rojava derives from. In Democratic Confederalism, the political structure of Rojava, social balance is emphasized, with no power structure given power to coerce another, but every power structure free to determine its own actions with direct engagement from the community it represents. In the words of Ocalan: “Democratic Confederalism is open towards other political groups and factions. It is flexible, multicultural, anti-monopolistic, and consensus-oriented. Ecology and feminism are central pillars” (Ocalan, 2017). Simultaneously, a social forcefield of autonomous councils and assemblies spawned by the democratic confederation resists external aggression and colonialism, whether this comes from foreign corporations, megapoles, or militaries.

Political Structure of Rojava

Municipal councils generally include a defense, economics, free society, civil society, justice, political, and women’s council. Similar councils are found at the canton (regional) level. Most councils (excluding all-women or all-men councils) guarantee at least 40% representation of women and at least 40% men, the co-chair seats also requiring one man and one woman. In areas where the ethnic makeup is heterogeneous, seats and councils are generally reserved for each population. The confederal Autonomous Administration includes four main chambers: Municipal Councils, Executive Council, Legislative Assembly, and Syrian Democratic Council (Ayboga et al., 2016)(SYPG, 2018). These four chambers are subservient to the municipal and regional councils, municipal councils collectively being one of the four main chambers of the Autonomous Administration. In other words, legislations made in the Autonomous Administration must be passed by these councils in order to go into effect. Councils may choose to accept or deny legislation from the Autonomous Administration, but are mutually bound to a confederal social charter of various egalitarian doctrines and laws (Ayboga et al., 2016). This horizontal structure ensures lack of social schism in Rojava, ensuring there is no distraction from the common front against coercive (and co-optive) actors. The Syrian Democratic Council acts as a diplomatic and representative body for the many political parties of Rojava. Though it is mostly concerned with the political and international relations of Rojava, it also has the power to appoint members of the Executive Council when elections have been postponed.

A network of media cooperatives serves to combat information warfare from coercive actors and provide an information channel for news on the ground that is often ignored by mainstream media. Rojava Information Center, Syrian Democratic Times, SDF Press, and many other outlets form a collective voice for Rojava, one that has gained the attention of many internationalists across the world and made the movement less isolated (RIC, 2020a). Grassroots media constructed by independent journalists in Rojava serves as an alternative to profit-driven mainstream media such as CNN or Fox News, which operate around Western megapole spheres of consensus. In Rojava, this media network has enabled the internationalization of the Rojava revolution and contributed significantly to its internationalist tendencies.

Military councils are detached from civil councils in order to ensure a separation of the military from civil society. This allows increased efficiency in the military councils while also preventing them from infiltrating civil political bodies. Accountability of the military is ensured both by civil and military councils and also by the confederation at large. In the defensive dimension, a subterranean tunnel system has been created, hampering the effectiveness of Turkish drones and artillery (Ayboga et al., 2016). Owing at least in part to its horizontal structure, the SDF has been able to hold off the Turkish state despite its intentions to annex the entirety of Rojava. A decentralized and unconventional guerrilla force has thrice been able to stop NATO’s second largest military from annihilating Rojava.

Disaster Relief

Though decentralized, disaster response has been highly efficient in Rojava. During the famine-spawning fires of 2019, disaster committees were able to rapidly dispatch volunteer firefighter teams, decreasing the damage done to infrastructure and saving many lives. Agricultural councils then swiftly enacted efforts to replant lost crops while ecological councils led efforts to reforest natural areas. During the Turkish state-induced dysfunction of Alouk Water Station, Rojava’s water committees worked together to redirect water input and import drinking water to prevent further humanitarian disaster. This action saved Rojava’s population. In the midst of the subsequent famine and Covid spread, health assemblies were able to reorganize medical infrastructure and expand services such as Heyva Sor a Kurdistanê (Kurdish Red Crescent). The presence of specialized disaster committees and assemblies has proven very beneficial for Rojava, no competition between private interests and no corporate meddling leading to loss of life (Ayboga et al., 2016)(Pressenza, 2019)(TRISE, 2020).

Tekmîl and Hevaltî

In military and civil assemblies alike, a community discussion process called Tekmîl (meaning “report” in Kurdish) is an important piece of connectivity, honesty, and cohesion in the community. In Tekmîl, each participant “gives critiques and self-critiques without any response from the other participants,” and sessions can be called by any member at any time, according to former SDF fighter and commune member Philip Argeș O’Keeffe (O’Keeffe, p. 1, 2018). This may sound like a simple activity, but it is highly significant to the social structure of Democratic Confederalism. Tekmîl is driven by a doctrine called Hevaltî. In the words of O’Keeffe: “Hevaltî roughly translates to friendship or comradeship. It is the idea that we work together, we help each other, we share everything from the tangible to the intangible not because we expect something in return but simply because we are comrades, that we are humans living, struggling and experiencing life together, that we are sharing the same purpose of trying to advance the collective wellbeing. It is the idea that we can trust and believe in each other and that we need not fear ulterior intention” (O’Keeffe, 2018). Tekmîl and Hevaltî both guarantee that no grievance goes unheard, and that collective decision-making is fluid while bound to no unilateral interests. Chairs and co-chairs of a given council are held accountable by the group they represent in this process. Aggregately this creates an ever-flexible social engine of civil and military society across Rojava.

Women’s Participation

Women’s participation is integral to the Democratic Confederalist structure. Unlike in Western states, feminism is not a contested idea constantly battling patriarchal structures of capitalism to become normalized, it is a codified norm of Rojava which has been interwoven into society at large. According to one Rojavayî citizen by the name of Xelîl: “We are embarrassed when we speak about 5,000 years of patriarchy. We should have raised our voice, we should have risen up. Dominant history writing belittles the Neolithic society and calls it primitive, but thousands of years ago, community was more ethical and centered around women. And now look what happened to the same geography” (Dirik, 2018, p. 233). The transition from Syrian state occupation to the Autonomous Administration saw a massive improvement in women’s rights and representation due to a feminist doctrine in Rojava known as “Jineology” or “women’s science.” According to one woman from Rojava: “A lot of husbands would not let women go out and would force them to stay in the house to take care of the children. Now everything has changed” (Argentieri, 2016). This is not to say patriarchy has been completely wiped out in Rojava, however. Sexual repression and internalized patriarchy in women’s structures have been cited as causes for concern, showing that the power of internal dialogue in the movement may have its limits (Gudim, 2021).

By empowering women and placing them at the helm of the revolution as well as its direction, the Rojava revolution enjoys the feminine power of half its population, a power which has rarely been accessed in centralized revolutionary movements to the same degree. The civil activation of as many social facets of Rojava as possible has allowed for its maximal power as a separatist movement, and this is largely owed to its decentralized Democratic Confederalist structure.

Flaws in the Democratic Confederalist Structure

Rojava’s political model does not come with perfection, however, having some notable weak spots. Occasional lack of organization and consensus can sometimes lead to vulnerability. Delta Crescent LLC’s exploitation of a few officials in the Autonomous Administration to occupy Rojava’s oil sector, for instance, shows that there may not be an effective mechanism of consensus in place at the confederal level. Though corruption is scarce in Rojava due to its tight systems of accountability, there is still some room for officials to act unilaterally, especially at the confederal level.