Some London Foxes

London 2016: the terrain of struggle in our city

1.1 London and the global economy

1.5 Two meanings of social cleansing

Part 2: Resistance and Rebellion

This is a small contribution towards mapping the terrain of social conflict in London today.

First, it identifies some big themes in how London is being reshaped, looking at: London’s key role as a “global hub” for international finance capital; how this feeds into patterns of power and development in the city; and the effect on the ground in terms of two kinds of “social cleansing” – cleaning out undesirable people, and sanitising the social environment that remains.

Second, it surveys recent resistance and rebellion to this pattern of control including the short-lived “grassroots housing movement” of last winter, the confrontational Aylesbury Estate occupation, anti-raids mini-riots, and some riotous street parties.

Third, it tries to stimulate some positive thinking about what we can do now to help anarchy live in “the belly of the beast”.

It doesn’t cover everything important and doesn’t offer “the answers”. But maybe it can help kick off some discussion and some action.

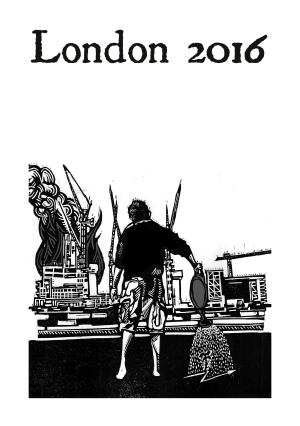

London 2016

Part 1: The enemy

1.1 London and the global economy

In 2008, London, like the rest of the rich world was hit by economic crisis. The roots of the crisis go back decades. From the 1970s, the world economy began to unite or globalise, the Soviet bloc collapsed, organised workers movements were finished off, the post-war Keynesian compromise crumbled, and neoliberal “free market” economics was unchained. As the “developing world” opened to international capital, industry shifted “offshore” from the rich economies to Asia or South America where wages were much lower. Back in the US and Europe, mines, factories and shipyards shut, unemployent and inequality soared.

In London and elsewhere in the 1980s, this new “dispossession” of the traditional working class led to unrest. In the post-WW2 era, social peace was maintained by “including” first world worker-consumers in a regime of high wages, leisure time and welfare state. Now new solutions are needed. Increased repression or discipline is one: expanding prison, surveillance, military-style policing. But even more important is to somehow maintain the central pillar of our society’s self-policing by consent, the consumer economy. The main means to do this is: debt. In a nutshell, China and other “productive” economies send their goods over on credit, receiving back longer term investment assets from bonds to real estate. The middleman in this global flow of goods, debt and assets is the finance industry, the banking system.

In this new order, we might distinguish two varieties of global economic elite. First, the industrial oligarchs, now increasingly linked to the former “third world”: gulf oil sheikhs, Russian mafiosi, Chinese party princelings, Indian steel barons, etc., plus what’s left of the old first world industrialists. Second, the international banking elites, who cream off their share to keep the global flow of wealth going.

London is a centre for both. Although global finance is slowly decentralising, for now its main trading axes remain the old capitals, New York and London. For the oligarchs, London is both storeroom and playground: somewhere to launder money and hide loot, buy property, shop, hold discrete meetings. It has big selling points. First, thanks to its history as a global hub of empire and trade, it is a central meeting point for the circuits of finance and industrial capital – and also for their armed wings, as London is also a (discrete) shopfront for arms dealers, security services, and mercenary companies. Second, it is safe, protected by a business-friendly and stable regime, with a tame local population. In addition, it has the cultural cache and luxury facilities demanded by the super-rich.

With these elites ensconced, enough wealth trickles down to keep the majority of the population still “included” in the consumer-capitalist dreamworld, first of all through employment in their armies of servants: from accountants and tax lawyers to estate agents, security guards, baristas, personal trainers, dog walkers, artists, etc. And, as wages stagnate, disposable incomes are maintained through debt: mortgages and small-time property speculation, credit cards, pay day loans, etc. And so we get by, and keep on shopping.

Or, most of us. There are also, as always, “the excluded”, those who don’t have a place in the economy and geography of the “global city”, and may threaten its order.

1.2 The housing boom

The most obvious motor of change in London’s environment is housing development. This development is fuelled by a “housing bubble” that directly relates to the city’s role as a global attractor of capital.

Let’s start with a brief snapshot of the housing situation. The average London home now costs around £500,000.i According to investment bank UBS, London is the second most unaffordable city in the world, after Hong Kong. If a “skilled service-sector worker” saved up all of their wages for 14 years (living on air and not spending money on anything else) they could just afford to buy a 60 square metre flat.ii

House prices have risen almost constantly over the last two decades. There was a brief slump following the 2008 crisis, but now in 2015 prices are higher than ever: 6% up on the previous peak in 2007. The recovery was dramatic: 40% up in two years from 2013 to 2015. Rents may not jump up and down as much as sale prices, but follow pretty much in line.

This is a London issue, not a national one. Although UK prices in general have also risen over the last decades, London has raced ahead: the UK housing market is still down 18% on 2007, and the overall UK economy grows slowly. London is now not so much a national capital as a trading hub for global capital – what the estate agents call a “global city”. Central London property prices are aligned more with Manhattan than Manchester.iii

As any economist can tell you, prices rise when demand outstrips supply. Politicians and experts of all stripes tend to take growing demand for granted and present the main problem as one of insufficient supply. For example, in 2013/14 only 23,640 new homes came on the market, while the city’s population rose by about 115,000. Most blame planning regulations: rules against building on the “greenbelt” land around the city; and constraints on high density in the centre.

Meanwhile, demand is strong at all levels, from super-rich “prime” real estate down to the ratholes most of us are expected to crawl into.

At the top, we have an influx of rich buyers looking for luxury property in central London. London now has well over 4,000 “Ultra High Net Worth” (UHNW) residents, individuals with a personal disposable wealth of at least $30million. This is the highest concentration of these unsavoury characters of any world city. Singapore was the only other city in 2013 with over 3000, according to Knight Frank research, followed by New York and Hong Kong with just below 3000 each.iv

Many of the rich buyers are “global”. In June 2013, “prime” (=expensive) estate agents London Property Partners said 85% of its clients were not based in the UK. The Financial Times reported in November 2013 that “foreign buyers” had bought almost 75% of new built dwellings in central London over the previous 12 months. Top-end estate agent Frank Knight, one of the main sources for housing market research, estimated that foreign nationals bought 49% of all central London homes sold for over £1 million, whether new built or second-hand.v (Although only 28% were not UK residents.)

This bulge at the top then has a ripple effect on the middle. Middle class couples who might once have nested in Notting Hill or Highgate are pushed out to previously working class areas, and so Kentish Town, Vauxhall or Herne Hill become “£1 million areas”.vi Here resident professionals compete for flats marketed as investment assets to parents of international students from the “developing world” elites in Shanghai or Mumbai.

Finally, down the foodchain, the global city also attracts drone workers into its service industries. This migrant labour comes both from overseas and from the rest of the UK, where the economy remains mostly stagnant. This trend is immediately reflected in the population figures.

The London population reached a high of 8.6 million in 1939, then over the next four decades people left the city in droves, many moving out to state-promoted “new towns” in the “home counties”. In the 1991 census, London’s population was only 6.4 million. The flood back to the capital began in the 1990s, and has accelerated. In 2015, Londoners topped 1939 levels for the first time. The city government (Greater London Assembly or GLA) estimates that the population grew by around 115,000 a year in the last four years. In fact, about two thirds of that growth comes from new born Londoners (83,000 more were born than died last year), only one third from people moving into the city. But these facts are related: people moving in tend to be young, coming in their 20s to get service sector jobs; then many have babies; then there is an outflow of people in their thirties and above, exiting with their families to greener pastures.vii

However, few of these incoming workers have a direct impact on housing market demand, because few can afford to buy property. Only 14% of the “household heads” who came to London from abroad in 2013-14 bought a house. 81% are renting from private landlords, as are 70% of arrivals from within the UK.

City of landlords

These figures point to another big trend: we are going back to the 1930s pattern of a city dominated by private landlords. In the postwar decades, that changed with the expansion of council housing, the state providing rented housing to much of the working class.

From the 1980s, there was another major shift as the Thatcher government and its successors promoted home ownership – or more accurately, bank ownership via mortgages. Local councils were constrained by tight spending caps and council house building fell to zero. Private/charity sector “housing associations” were promoted to fill some of the gap, but the main source of new housing was private for-profit development. Council tenants were given the “right to buy” their homes at a discount. Regulation of mortgage lending and the financial markets behind it was stripped away. Interest rates were held low.

The home-ownership boom served a number of key political objectives. It kept the economy bubbling as industry collapsed; created healthy profits for the finance sector; and spread a culture of “owner occupiers” invested in the system’s stability and growth. However, the home-ownership trend is now reversing, as fewer “ordinary people” can afford to get on the “housing ladder”. Now housing demand is driven as much by landlords and investors as by “owner-occupiers”.

For sure, these are often not distinct: a property may be both a home, and an asset. Since the 1980s, small-scale property speculation has become embedded in British mainstream culture. Many private landlords are small fry, e.g., a family moves out to the home counties and rents out the old London home; or uses a “buy-to-let” mortgage to buy a second house as a “nest egg”. Big residential property developers aim to sell their flats not rent them out. Big investment funds have, traditionally, focused on commercial property portfolios (offices, shops, hotels) rather than residential.viii But this may be changing: state and markets are both pushing growth of the private rental market and encouraging institutional investors to enter.

In 2013/14, only 3,750 new homes were built for “social rent” by local authorities or “social landlords”, as against 17,600 for full market rates. While the distinction between “social” and “private” landlords vanishes, as charitable “social landlords” are setting up “market rent” divisions, or forming joint ventures with commercial property developers.ix

One more important London property point: new developments tend to be at the “luxury” end. That’s where the profit is: the higher the sale price, the higher the developer’s mark-up. There’s little “prime” land left to build on, but the “prime” zone must keep expanding. To make this happen, there are various work-arounds. An outlying area can get better transport links, or just get rebranded. A cut-rate development can still look glossy, aping the glass and steel neo-brutalist style of the high-end even if spaces are cramped and materials shoddy. This is the age of aspiration, the age of the make-over. Above all, everything must appear clean, shiny, and safe.

Is it a “bubble”?

Finally: the housing boom in London is often described as a “bubble”, implying that sooner or later it’s going to burst. The term “bubble” indicates that market prices have lost touch with the “fundamental” or “intrinsic” value of a commodity. But then what is the “fundamental value” of a London house?

Here is a traditional view: fundamentally, a house is somewhere for people to live while they work, save, contribute to the economy, then retire and pass on their property to their children; so the “fundamental value” of a house should reflect people’s lifetime incomes, their share in the economic life of the nation. On this picture, house prices have gone mad, are divorced from any reasonable expectation of what people can afford to pay in the long term. This is unsustainable, and at some point the crash must come.

But London houses are not just places for Londoners to live: they are also piggy banks (“safe investment assets”) for global capital. This makes the picture much more complicated. How do you assess the extent, depth and stability of global investment demand for London property? Does anyone really have a clue how sustainable this pattern is?

1.3 Two emanating power hubs

It can often be helpful to think about power in terms of networks. Power is relational, i.e., any individual or institution’s power depends on its interactions, alliances and oppositions, with other bodies and objects; so we can try to trace this power by seeing the individual or institution as a node in a network of connections. Maybe one of the first ever network diagrams comes from Jewish kabbalistic mysticism: the diagram of the 10 sefirot. Divine power flows or “emanates” down to us through these 10 networked spheres.

A diagram of the power relations of London, whether we think about it economically or geographically, would have some similarities. In this case, there are two main hubs of power and wealth at the top — or rather, at the centre. These are: the City of London; and the old elite quarters of the West End. Power emanates or radiates out from these two hubs, shaping the city around them. Their power itself draws from a bigger world of relationships: they are where London is plugged into global flows of wealth and power.

The two power centres are closely connected, but also distinct. The City is home to the big global banks, trading exchanges (for stocks, bonds, derivatives, commodities), and insurance companies. It is the where these institutions straddle America, Europe, and Asia: just offshore from continental Europe, and half way between US and Asian timezones. It is the visible, shiny, face of world finance, with its glass towers and neon logos. Canary Wharf, further south and east in the former docklands, is an offshoot node, linked by the Docklands Light Railway to Bank station. Other crucial connection points in the docklands zone include the sites of London’s main internet infrastructure, and City Airport: e.g., it was reported that financial trading was hit by a day of fog in November 2015 as many senior bankers fly to work by jet or helicopter.

The West End, for our purposes, means the area of the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Traditionally, this area is both the seat of government and the home of the elites, where wealth is stored and spent. Mayfair and Knightsbridge are the “noble” residential areas, the home of British “old money” and of the global oligarchies. But this is also a trading zone: only the deals done here are more discrete, they take place behind unmarked doors in old townhouses. Mayfair is the base of hedge funds and private equity firms, whose investments are not quoted on public exchanges. Arms dealers and mercenary companies have their offices around Regent Street. Still more private deals are brokered not in offices but in the “gentlemen’s clubs” of St James, or in the luxury hotels.x

Around these two centres, we can see many satellite nodes, auxiliary hubs that serve and in turn draw power from them. These include some geographically sited in between the two main hubs, in the eastern part of the West End and the area estate agents now call “midtown”: the legal power hub in Holborn, including the “Inns of Court”, Royal Courts of Justice and Old Bailey; media, fashion and entertainment industry bases around Soho; the knowledge complex around the university and British Library in Bloomsbury; the flagship stores of the consumer hell around Oxford Street, Regent Street and Bond Street. We can also add the newer power sites of the “creative quarters”: the hipster belt stretching around the North and East of The City, from Clerkenwell and Shoreditch to Whitechapel and the old East End.

Even as Britain declines as a nation, the two London hubs grow, because they draw and concentrate trans-national wealth and power. They attract both financial capital, funds to invest, and “human capital” — from top executives down to their lowest servants. Both help reshape the wider economy/geography of the city: the human capital needs office space, housing, and places of hospitality and entertainment; a portion of the financial capital helps meet this demand as it is invested into the “safe haven” of London real estate.

Very roughly, real estate development in London expands in concentric circles from the two hubs. This has been the pattern since the 1980s, beginning with the redevelopment of the docklands zones south-east of The City. Its icons were glass-faced yuppy penthouses along the river. More subtly, as residential property was squeezed in the traditional “gentry” areas to the west, mixed North London boroughs such as Camden and Islington, and eventually even Hackney and Haringey, were colonised by the middle classes. Into the 1990s, gentrification went wildfire, engulfing inner London zones like Hoxton, once the preserve of the white working class, and starting to spread into black areas of South London, once “no go zones” for the middle classes.

In the new century, the pace has quickened exponentially, development projects have got ever bigger, flashier and more ambitious, and nowhere is “no go” any longer. Any initial reluctance, for example from left-leaning local authorities, is long gone. Schemes that would once have seemed unrealistic — e.g., because they involve demolishing whole swathes of low-rent housing to build high-density skyscrapers with barely a nod to planning conventions or new “social housing” provision — are now just the unchallenged norm. Zone 2 areas are now considered “inner London prime”.

1.4 Developer partners

London’s development is driven by finance capital: wealth, money, radiating from the two big power hubs in the centre. But a host of further players and projects are involved in the transmission system, in the channels through which that wealth reshapes the landscape of the city. To study that more concretely, let’s take the example of one particular development scheme, the Aylesbury Estate in Southwark.xi

The Aylesbury was once called Europe’s biggest public housing scheme, with over 2,700 units. It was built in the 1960s as part of the clearance of old slum housing in Walworth, an inner city (Zone 1) area near the Elephant & Castle roundabout, not far south of the river. In the 1980s the Aylesbury, like other council estates, fell into disrepair as the Thatcher government waged fiscal war on Labour local authorities, slashing their housing (and other) budgets. By 1997, it had become strongly identified by media and politicians as a “failed estate”, a site of crime, violence, architectural dysfunction and “social exclusion”. That year Tony Blair made his first speech as prime minister on the estate, promising to care for the “forgotten” people of the Aylesbury and a number of other working class areas identified as “New Deal for Communities” pilot projects across the country.

The New Deal plan involved transferring ownership of the estate away from Southwark Council to a private/charitable sector “Housing Association”, which would be free to borrow on the financial markets to fund redevelopment (unlike councils, as the Labour government continued the Thatcherite funding squeeze). The “utopian” 1960s buildings with their open communal corridors and courtyards would be demolished, to create a new landscape with more private space and increased “security”; the number of low-rent homes would be decreased; while middle class professionals would move in, creating a socially healthier “mixed community”.

In 1997, this model was still radical. Under existing law, the change in landlord — called “stock transfer” — required acceptance from a majority of official tenants in a formal vote. To the shock of politicians and housing professionals, tenants refused the deal; as others also started to do in cities up and down the UK. Ever since, Southwark Council and its “developer partners” have been trying to get a similar scheme through by other means. The current project involves “decanting” out all the tenants first to other accommodation, in a number of phases, then handing over the vacant land (there is no one left to vote no) to a consortium which plans to build an even higher density scheme releasing thousands of new flats onto the private market. This demolish first model has already been used successfully on the nearby Heygate Estate, a very valuable piece of Zone One land next to the Elephant & Castle roundabout, handed by Southwark to major global property developer Lend Lease to build a complex of luxury skyscrapers containing zero “social rented” housing.

On the Aylesbury, the development consortium involves the following partners:

- Barratt Homes. One of the UK’s biggest private property development corporations, whose shareholders are the usual big global institutional investors.

- Notting Hill Housing Trust. One of the UK’s largest semi-charitable “Housing Associations”. In fact, although nominally non profit-making, NHHT is now a major business run along standard corporate lines with highly paid executives and a board of directors including Conservative politicians and the chairman of a big housebuilding company. Privately sold and rented homes make up a growing proportion of its business.

- Southwark Council. A local authority controlled by Labour Party councillors, including their leader Peter John, a City barrister who has received dozens of free dinners and expensive gifts from private donors, largely property developers. Asides from elected councillors, decisions are made by highly paid executive officers, who often have careers also working for private finance and property companies.

- Creation Trust. A stooge board to represent the residents of the estate and surrounding neighbourhood, made up of on-side council tenants, local religious and business people, and chaired by councillors. Initially funded by government money, but now paid by NHHT.

- Architects. The consortium involves two major architect firms – HTA Design and Hawkins Brown – which are involved in numerous other high profile development projects across London and elsewhere; and one smaller architect firm, Mae.

- Consultants. Deloitte, a global business consultancy, advises the partners. A small “third sector” consultancy called Social Life is also involved, providing cover by doing consultation activities with residents.

In terms of capital, Barratt is the main financial muscle behind the deal. In turn, behind it stand major investors: banks and investment trusts that will ultimately bankroll and profit from the whole scheme. NHHT is also funded by major investors: it does not have institutional shareholders, but sources investment through bonds and bank lending.

The financial backers have quite clear economic incentives: maximise profits from the scheme. Architects, consultants, corrupt councillors, “community representatives” and the rest, also stand to do well financially from the deal. But developer and housing trust executives, council leaders, designers, etc., have other incentives too: high profile schemes like this are key items on their CVs, badges of status and accomplishment, networking opportunities, and more. And for some involved, no doubt, they are also opportunities to “do some good”, to “give something back”, to help “regenerate communities”. Those involved can look forward to a healthy pay-off, a slap on the back, and a smug glow all in one.

1.5 Two meanings of social cleansing

What are the effects of this development pattern at ground level? Many have come to sum it up as “social cleansing”. And this is an apt description, particularly if we can understand it in broad terms. Development is “cleansing” the city in two big ways: moving out undesirable humans; and sanitising and securing the social environment for those who remain. Let’s look at these two issues in turn.

1) Cleaning out people

Less desirable humans are pushed outwards from the city centre. This can happen in a number of ways, for instance:

- as neighbourhoods become more desirable, private landlords increase rents, pushing out lower-income tenants;

- lower income home-owners may “cash in” and move voluntarily as their property increases in value;

- raids and crackdowns evict or threaten illegal immigrants, sex workers, unofficial sub-letters, dwellers in “over-occupied” or unsanitary properties, etc.

It should be noted that, while the movement of poor people from the centre is a real phenomenon, it is not the whole story. Even in strongly gentrifying areas, poverty is far from disappearing. One reason is that, as rents rise, many people respond not by crowding into smaller spaces rather than by moving away. We are seeing a return of slum-like overcrowding as landlords divide up buildings into tiny bedsits, families cram into single rooms, etc.

Another is that the concentration of council and “social housing” in inner London is still a major drag factor on London gentrification. These tenants have state-guaranteed low rents and superior tenancy rights. The state has been chipping away at this problem for thirty years, using various tactics including:

- selling tenants their homes cheap under “right to buy” – then hitting them with high service charges or big bills for their “share” in the cost of a development scheme, so that they are pushed to sell;

- transferring council tenants to higher rent housing association tenancies;

- waiting until existing tenants move out, then re-letting those flats under higher rent contracts (a method pioneered by NHHT), or leaving them empty for demolition (“decanting”);

- forced demolition schemes such as the Aylesbury;

- welfare cuts such as benefit caps, tightened assessments, and the new “bedroom tax”, under which poor tenants will not get housing benefit (reduction in rent) for “spare rooms”;

- in the latest move (December 2015), the government plans to replace lifetime council tenancies with five year contracts.

2) Cleaning the social landscape

But also: even when the human beings stay, the social environment is transformed as the neighbourhood is “cleaned up”. New development projects in London follow very clear design patterns. They almost invariably involve:

- large square glass-faced apartment blocks, the less bland designs often recalling fascist architecture of 1930s Rome (on the cheap);

- in grids of controllable straight streets, studded with CCTV cameras;

- removing narrow alleys, corridors or “rat runs” that are hard to monitor and control;

- introducing street architecture designed to prohibit “loitering” or sleeping, e.g., “anti-homeless spikes”, removal of benches and public toilets, etc.;

- these housing developments are integrated with new shopping areas, built as identikit US-style malls, brightly lit and intensely monitored, leased to chain stores plus a smattering of “aspirational” boutiques and coffee shops;

- where old street markets persist, these are controlled with increased surveillance and policing, as rising charges force out informal and low-profit traders, who are replaced by purveyors of expensive “artisan” products;

- meanwhile, “neighbourhood wardens”, “police community support officers”, and other low-paid mini-cops-with-attitude are drafted in to patrol all public areas;

- these impose crackdowns on anyone gathering to drink, play unapproved games, or just be young, in signposted control “zones” enforced by “anti social behaviour orders” (ASBOs).

As the last list indicates, although the profit motive may well be supreme, the development impetus can serve multiple aims.

Developers, backed by financial capital, profit from increasing the control and “hygiene” of a zone, because these are important selling points for their buyers: particularly, for the rich, investors, and “aspirational” middle classes who are their main targets.

But developers also work in partnerships with other bodies — local authorities, local businesses, police forces, “community representatives”, etc. — who have their own projects of order and control. Developers, state institutions, and “third sector” bodies form symbiotic relationships, partnerships of mutual benefit, that serve both profit and control.

Part 2: Resistance and Rebellion

2.1 A safe haven

In talking about resistance and rebellion in London, we may as well start with the obvious point: there isn’t much.

One of London’s attractions for global capital is safety. Rich residents, visitors and investors have little to fear from any quarter. The state and other power institutions are stable, well-established and benign. Coups or policy swings away from the norm are unheard of. Investment is welcomed with minimal tax or regulation.

As for the populace, the once proud London Mob was put to bed two centuries ago, and has rarely stirred since.xii Only on a handful of occasions in the last 100 years has there been any threat of major unrest, and each time shortlived.

- The UK has only known one national General Strike, in 1926. This paralysed London for a few days, but was efficiently put down by the trade union leadership itself.

- At the end of World War II, the state had reason to fear disturbance from de-mobilised returning soldiers, including a mass squatter movement after many were made homeless by the German blitz. The election of a Labour Government, which instituted a major house building programme and other welfare measures, successfully absorbed this energy.

- In the 1970s and 1980s, the collapse of the post-war economic settlement, then the Thatcherite shift to more open class war, increased turbulence. In the mid 1980s, as the Nothern mining regions rose in a strike that began to approach insurrection, London “ghetto” areas such as Brixton in the South and Tottenham (Broadwater Farm estate) in the North burst into flame.xiii Ultimately, the state proved able to contain and isolate disturbances; the social “centre” held, leaving the “excluded” to feel the clampdown; and once again the left – the Labour Party, the Trade Union Congress, and the Trotskyist sects – played its pacifying role.

- In 1990, the loathed “poll tax” (a local tax that charged all adults equally irrespective of income or property) was defeated. The anti-poll tax campaign involved a widespread grassroots mobilisation in parts of London and other cities, unprecedented for generations, often directed by smaller left parties but with some elements of self-organisation. It culminated in the most spectacular day of rioting in central London (as opposed to the ghettos) of living memory. The government dropped the tax and order was restored. Thatcher resigned, others carried on her work.xiv

- In the late 1990s and 2000s, neighbourhood campaign groups on the council estates, sometimes linked to the Trotskyist left or to the remnants of anti-Poll Tax networks, managed to prevent some of the more rapacious gentrification schemes (e.g., on the Aylesbury Estate), but were far too weak to hold back the general tide of development.

- After 20 years of calm, London and other cities rose for five nights of burning and looting in August 2011. In London, the riots began in the North (Tottenham) and spread across all marginalised areas of the city. Central London and the rich neighbourhoods were untouched. After a repressive clampdown that imprisoned 1000 people, life returned to normal.

2.2 Some seeds

Three and a half years later, in the winter of 2014-15, we began to see some small murmurings of self-organised resistance at the frontlines of spreading development.

In September 2014, a group of single mothers threatened with eviction from a hostel, who went by the name “Focus E15”, occupied a small block of flats in the Carpenters’ Estate in Stratford, East London. This was a housing estate right next to the site of the 2012 London Olympics, that had been mostly “decanted” and left open for another classic demolition and gentrification scheme. The occupation only lasted a few weeks but attracted much attention and inspired others.

Similar occupations and high-profile protests sprouted in the next months across other working class neighbourhoods: New Era Estate in Hoxton (East End); Cressingham Gardens and the Guinness Estate in Brixton; West Hendon and Sweet’s Way estates in North London. The same period also saw a rise of “radical casework” housing activism championed by groups such as Hackney Renters (aka DIGS) and Housing Action Southwark and Lambeth (HASL): fighting individual evictions with tactics from legal action to pickets, office occupations, or direct resistance.

The left and liberal media salivated over these campaigns. All the elements were there. The firgureheads were mothers, or at least “local working class women”, who could be hailed as “genuine” political subjects rather than “outside agitators”. They were ranged aginst cartoon villain politicians like the deeply unpleasant and corrupt mayor of Newham, Sir Robin Wales. They practised “civil disobedience” or “non-violent direct action”, which looked good for the cameras but didn’t overstep the bounds of civility. Celebrities rallied round for sleepovers and photo ops, comedy-messiah Russell Brand leading the way.

The local occupations were relatively autonomous, in that the traditional recuperating forces of the Left – the Labour Party, the unions, the trotskyist Socialist Workers Party – were mostly absent. The SWP had been smashed by a big rape scandal, while Labour appeared in terminal decline. The ground was perhaps fertile for new forms of self-organisation and unmediated rebellion.

Although, behind the scenes, there were some moves towards more centralised political organisation. A number of the E15 and other activists were involved with the small marxist “Revolutionary Communist Group”. The big trade union Unite, the main funder of the Labour Party, handed out some money and professional organisers, and sponsored a London-wide forum called the “Radical Housing Network”.

The Radical Housing Network called for a major demo – the “March for Homes” – on 1 February 2015. During this demo, a group of anarchist squatters intervened with a breakaway “Squatters Bloc”, which upped the ante with an ambitious and combative occupation on the Aylesbury Estate.

2.3 The Aylesbury occupation

The idea of mass squatting one of Southwark’s big “decanted” demolition estates had become a holy grail of South London squatting legend. In 2010-11, an exciting time of student mini-riots and occupations that perhaps helped feed the August 2011 uprising, London anarchos held a number of planning meetings for a proposed occupation of the Heygate. These came to nothing: taking over a big estate and holding it against the police seemed beyond our capacities, we talked for months and did nothing. The Aylesbury scheme, on the other hand, was totally last minute. It seemed like a mad experiment, and it didn’t last long. But for the two months it did, it was about the most exciting thing to happen in the city for a good while, and may hold useful lessons for the future.xv

On the day, a breakway bloc of about 150 diverted from the March for Homes down south to take the estate. Very few of those stayed that night, but over the next days numbers grew and the occupation took hold. On the first full day, squatters made contact with estate residents who had campaigned for years against the demolition, held an open air meeting, and relationships began to form. Following the example of E15, the idea was to have one house as a collective space open every day for people to gather, exchange, plot, talk. Visitors arrived from Stratford, Hackney, and all over South London. But it would also need more permanent residents to defend the space and bring it to life.

From the start, there were some obvious lines of tension: between anarcho-squatters, leftist tenant campaigners, other locals of various backgrounds and allegiances, students arriving to take pictures or write dissertations, not to mention a drug-fuelled money-hungry rave crew appearing on the scene. Some of these encounters were provocative and productive, some a headache.

For the first two weeks, the authorities had no plan, and left the occupation alone to flourish and grow. Then they came with the first eviction attempt on 17 February, bringing up to 100 riot cops. The occupation outfoxed them: we had prepared a second building, defended by barricades the council itself had built in a vain attempt to keep us out, and got enough people down to out-number the riot police. Although the immediate area around the occupation was empty awaiting demolition, the blocks nearby were hostile territory for the state, and the local police were well scared of starting a serious riot here. We won the night; they de-escalated.

Which was the sensible move for them. In the next weeks, the police avoided major confrontation, while the local council wore down the occupation by siege. They built a £150,000 razor-wire topped fence around the occupied area, locking us off from the rest of the estate, and hired a force of private security guards (easily costing hundreds of thousands more) to contain and harass. It worked. Only the most “hardcore” occupiers, without many other commitments, could stay long under these conditions, and numbers gradually decreased as other squatters found easier accommodation and supporters got locked out. The occupation went out with one last bang, pulling down several fences in a well planned and well executed final demo on 2 April (which, again, Southwark Police sensibly let happen.)

In the final analysis, London’s existing squatting networks didn’t have the strength, the numbers, to hold the occupation for long. And although the occupiers saturated the whole estate and surrounding area with posters, leaflets, messages in paint or chalk, knocked on doors, held street stalls, called meetings, demos, gatherings, etc., the vast majority of Aylesbury residents weren’t roused to action. Many opposed the development and supported the occupation, but with a few very notable exceptions this support was passive. The occupation did not manage to help activate this passive opposition.

Southwark Council’s decanting strategy, so far, has proved effective. The estate has been left to deteriorate for 20 years, so that tenants start to believe anything else might be better. Those who agree to move are offered shiny new homes. Any who refuse face losing their tenancy and any chance of an affordable home in central London. And the whole scheme is phased over years, people being moved out in dribs and drabs rather than in one dramatic mass eviction.

Perhaps the biggest threat the occupation posed, as the police (if not the council) certainly realised, was that rebellion in the emptied part of the estate would spread to the youth and other confrontational elements in the blocks and streets nearby. The siege succeeded in containing us and preventing this.

2.4 Raids and mini-riots

Almost three months after the Aylesbury occupation ended – in fact on midsummer’s day, 21st June – a Home Office “immigration enforcement” team arrested a man in a fishmongers shop in East Street, the street market nearby the Aylesbury and Heygate developments. Immigration cops had already carried out a number of raids on East Street that week. And they had already gone empty-handed once that day after a group of teenagers gathered around their vans and started shouting abuse. When they decided to return a little later, someone spotted them and posted an alert on social media, which was picked up by the “Anti Raids Network”. The alert spread fast through internet and real-world grapevines. The van with the arrested person inside was surrounded and blocked, the tyres were let down, immigration officers were pelted with eggs and fruit.xvi

Home Office enforcers called Southwark Police, who called in the “Territorial Support Group” (TSG) riot squad. Now more and more people were arriving, from twitter lefties to local teenagers. There was a street battle as people barricaded the roads to prevent the vans leaving and attacked with rocks, street furniture and whatever else came to hand. The riot police eventually managed to escort the “racist van” with the prisoner away and leave the area, suffering several injuries and two broken windscreens themselves. After the police had left, the crowd celebrated its moment of rebellion dancing to a mobile sound system.

The next two nights, there were demos at the Walworth Road police station, where one person was held after being arrested early on during the blockade. The public area of the police station was occupied, turned into a party zone, and well vandalised.

Throughout these incidents, police clearly continued to follow a strategy that may seem surprising to those unfamilar with UK policing, but makes good sense: avoid, indeed flee, confrontation where there is a real risk of escalation (even in your own police station!); get revenge later by raiding and arresting people at home, using CCTV and media footage to identify and incriminate targets.

In the days that followed, anarchists went back to East Street and the blocks nearby handing out leaflets, putting up posters and talking to those they met about what happened and about how to ward off the expected repression. Currently, four comrades are on bail and facing trial for charges including “violent disorder” and “false imprisonment” – i.e., kidnapping the immigration police!

This small uprising was a taste of just what Southwark police had sought to avoid during the Aylesbury occupation: anarchists, Aylesbury residents, market people and neighbourhood teenagers fighting together against the authorities, actually chasing them out of the area. Whereas the Aylesbury occupation had been safely contained by the fences, this time rebellion spread into the streets and across divisions of age, background, identity.

How social cleansing creates flashpoints for rebellion

There are some pointers here about what rouses people to fight. Abstract proposals like “save the estate”, “fight for our homes”, or “stop gentrification” move at best a tiny handful to active resistance. What can get people going, at least for a moment, are:

- rage against the police;

- the thrill of taking the streets.

In London as elsewhere, the immediate spark of most street-fighting is police violence. The Brixton and Tottenham riots of the 1980s to the riots of 2011 were all responses to police killings; the 1990 Poll Tax riot began with a police charge. Of course, the spark lights existing fuel, anger built up after being pushed around for months, years, lifetimes.

Maybe no riot or other widespread rebellion has ever started as a principled objection to the “social cleansing” of the city. But, for sure, the social cleansing of the city can provoke rebellions. This happens where: (a) it pushes people in ways that build rage, rather than just resentful resignation; and (b) it creates violent flashpoints, such as evictions or raids, which spark that rage into action.

Development runs smoothly if it manages to avoid both of these. First of all, if a scheme like the Aylesbury is felt as natural and inescapable, just “how things are”, then most people’s response is resignation: what’s the point of getting angry? Second, direct violence and confrontation should be minimised, or at least carried out as invisibly as possible. Ideally, from the developers’ point of view, the Aylesbury scheme won’t involve a single forced eviction. Tenants will be one by one bought out or worn down by legal procedures and threats, with the few resisters isolated behind a security fence.

Alongside evictions, raids are another integral part of the “social cleansing” pattern. Street markets like East Street are regularly targeted. These are often “multi agency” operations where immigration officers work alongside, e.g., police “anti-gang” or “anti-trafficking” initiatives, local council planning or “food safety” departments, etc. In short, targeting “hygiene” and “anti-social behaviour” on multiple levels as part of the cleansing of the social environment.

De-normalising raids

East Street is certainly not the only case of resistance to raids. A few weeks later, in Shadwell, East London, four immigration vans were attacked and had their tires slashed, as residents threw eggs from the buildings above. Other publicised examples happened in the last year or so in areas across London: Peckham, Southall, Newham, New Cross. In a radio interview from September 2015, an Immigration Officers’ trade union representative said that their colleagues were being attacked in incidents every week.xvii

Why have immigration raids in particular become a focus of resistance? First, it’s certainly not the case that all are resisted. In fact many, for example dawn attacks on people’s homes, are rarely even noticed by anyone except those directly affected. First of all, the raids that do ignite rebellion are most often those that are highly visible, they take place on busy streets, and that are obviously violent and provocative.

But, also, immigration raids are visible in a further sense: they have not been submerged into the “normality” of city life. Police attacks against “criminals”, or bailiff attacks in defence of “legitimate property”, have become relatively normalised now across most of the city – i.e, they are seen as part of the natural, right and just order of things – and so are barely noticed. In the case of the police, it may take particularly extreme acts of violence to crack the facade of normality. Possibly, immigration raids are not normalised in the same way. Even many “law-abiding” Londoners object to them as racist, arbitrary abuses of power, carried out by undisciplined bullies.

The Anti Raids Network and others have helped to stop immigration raids becoming normalised. Posters, leaflets, graffiti etc. against raids are becoming common in some areas. In the age of smartphones, reactions to raids are swiftly recorded and spread, and attacks against “racist vans” have become a kind of “meme” on London social media. (The term “racist van” originally referred to vehicles driving around advertising government anti-immigration slogans telling people to “Go Home”, which were very widely condemned and satirised.)

Finally, of course, none of us ever sees the full picture. For example, groups of youth responding to police attacks such as “stop and searches”, “anti-gang” raids, etc., are probably more common than fights against immigration enforcers, but much less publicised outside immediate circles. There are still many things you can’t read on the internet, but only hear on the streets.

2.5 Street parties

A riot doesn’t just attack the physical authorities (police, immigration officers), but also the rules (norms) that make the spaces around us into spaces of control. Keep off the road, don’t make noise or mess, don’t take what isn’t yours, don’t write on the walls, don’t break anything, etc. Breaking these boundaries, and doing it together with others, is exhilerating, liberating. It doesn’t need a full-on riot to liberate space in this way, though they often come together: if you take a public space the police will eventually attack to take it away from you.

Like many other places, London has its carnevalesque traditions, which have often led to clashes with authority. In previous decades, riots often sprung up at the Notting Hill carnival, in August, when police attacked Afro-Caribbean carnival-goers. In the 1990s, “Reclaim The Streets” organised disruptive street parties in Camden, Brixton and other areas, leading in 1999 into the “J18” carnival-riot in The City itself.

In the last year, a number of the most interesting moments of transgression came from parties. On 25 April, what the organisers hoped would be an orderly protest against the “gentrification of Brixton” became much more lively when some of the crowd left the “designated protest area” in Windrush Square and spilled into the street, blocking the A23 (one of London’s main arterial roads) to dance with sound systems. Passers-by joined in, teenagers called up their friends. The main window of Foxtons, a hated up-market estate agent, was knocked through to big cheers. Large breakaway groups momentarily stormed the Town Hall and the Police Station. Apart from some broken glass and stolen police gear, there was no “violence” until, inevitably, the TSG arrived and started to push people up the road with truncheons.

Other small breaks in order occurred at the “Fuck Parade” street parties called by Class War through the year in Whitechapel, Camden and Shoreditch. These took the streets with sound systems and smoke and flares. They targeted gentrifying areas where there is both social tension and nightlife. The most successful, and most villainised by the media, was in Shoreditch in September 2015, where up to 1000 people joined in, estate agents got smashed, and the crowd notoriously attacked the hipster “Cereal Killer” cafe (selling expensive breakfast cereal).

The real party-riot, though, came when police tried to stop hundreds of ravers from getting to the Scumoween squat party in Vauxhall, just south of the river, at the start of November. This seriously kicked off, with barricades, police charges and street fighting into the night.

It should be noted that these moments of freedom often carry a cost. Particularly when people get reckless on drugs and drink and don’t worry about covering their faces. Seven people were charged with criminal damage or violent disorder after Brixton. Over 20 are currently facing prison for Scumoween. In both cases, arrests at the time were followed up by police witch-hunts which include publicising photos of suspects, taken from mainstream and social media as well as CCTV.

Some might dismiss these events as empty hedonism or “spectacle”. But they are an important strand of what rebellion does happen in London. Some of the people who get involved are lefties or anarchos, but many others are kids, ravers, passers-by who wouldn’t ever turn up to a demo. Together for a moment, we take the streets, meet strangers, challenge the control of the city’s space, and sometimes put up a real fight.

2.6 The movement and its movers

In the first half of 2015, for a few months, it seemed like something might be emerging between the occupied council estates, from Stratford to Southwark. As we visited each others occupations or street stalls or street parties, connections were formed across the city, know-how and ideas were shared, and new shoots appeared in unexpected places. Some started to call it a “movement”. When the Aylesbury estate occupation left, those involved anticipated a short break, not the end.

But by September, with the eviction of Sweets Way, all the occupations were gone. Some of the campaigns won concessions: individual campaigners have been guaranteed housing; and there have, as yet, been no demolitions on the Carpenters or Aylesbury Estates. But these schemes are more likely delayed than abandoned, to return when the heat has died down. Indeed, Newham Council is now again publicising gentrification proposals for the Carpenters Estate. On our side, the flow of ideas and actions seemed to have dribbled out. The Aylesbury occupation had called itself a shark: keep moving or die. The “movement” had stopped moving.

Why? Ultimately, it had drawn on a narrow base of people, committed individuals and groups, the same old-timers and a few new faces. It had, after all, been a movement of “activists”, engaging few people beyond quite closed circles, only ever big in the echo chamber of the left and liberal media. The hard truth: hardly anyone else gives a shit, or believes there is any chance of stopping the inevitable course of things. It’s not that everyone’s happy with the way thing’s are: who the fuck is happy? But few imagine any other possibility. For decades, generations, what’s been ground out of us is imagination.

To make things even worse, it seems the ghost of leftism is still here to drag us down. After the rape scandal, the SWP appears to have stabilised and is visible on demos again. With the election of left-winger Jeremy Corbyn as Labour Party leader, the left has rallied round the corpse again. And the problem is deeper than these parties. The left is a state of mind, a set of habits, a culture still deeply engrained amongst “activists”, including many who call themselves anti-authoritarian.

This came out clearly at what seemed the height, but was in fact the end, of the “housing movement”. A group called Brick Lane Debates had coordinated a number of big public meetings, including one next to the Aylesbury Estate. The first were simply gatherings where people involved in different campaigns could meet, exchange ideas and contacts. But a further agenda emerged: to transform these gatherings into a “Radical Assembly” which would become an organised collective body with a statement of principles, voting procedures, calls for mass events, etc., along the classic lines of a left organisation. The first Radical Assembly meeting attracted several hundred people, some from the estate campaigns. In the next few weeks, there was a series of further meetings, at which numbers and interest dropped each time. It was a sad reminder of how the old strategies of the left divert people into organisational schemes that become talking shops, sucking up energy and stifling action.xviii

The reality is there never was a London housing “movement”. There were pockets, cracks and sparks of activity, small experiments. Some people met, inspired and learnt from each other. Meeting places to help these encounters happen were welcome. But the last thing we needed was an organisation or collective programme. New ideas and above all new actions would have kept momentum going longer. But, even then, realistically we were a long way from breaking out of the tiny circles of London activism and become a serious threat to the status quo.

Which raises the question: aren’t there better ways to think of how to fight, in this city, than “building a movement”?

2.7 Out of the centre

First, though, one observation: all the events discussed above took place on the “front lines” or fault lines where development is hitting traditionally working class areas of the city, and where social tension and state violence are pronounced.

Was there nothing interesting to write about in the centre of town? In May, there were some clashes between police and protestors near Downing Street after the the Conservative Party unexpectedly won the general election with an increased majority. Tabloid media started hyping up a “summer of thuggery”, which didn’t materialise. On 5 November, once again several hundred people wearing V for Vendetta masks, waving flags of all stripes from Union Jacks to Circled-As, ran around in the centre of London, threw some fireworks at cops and Buckingham Palace and set a police car alight. The car fire was quickly put out.

In fact, not since the student protests of 2010-11 has their been any hint of the state losing control even for a moment in central London. In August 2011, the riots did not get near the two central hubs – The City and the West End – discussed in the first section of this pamphlet. Even as the police lost control of the streets of “our” London, the power zones remained heavily guarded and secure.

Since then, every incursion into the city centre has been easily managed: surrounded, “kettled”, and smothered. We have not had the numbers, aggression or initiative to break control in the enemy’s own home territory. It’s not only that the centre is more heavily surveilled, policed, and designed for control. But also, here any invading group is quickly isolated in a sterile zone: office workers or tourists aren’t likely to join in, it’s far for reinforcements to arrive. In short, rebellion does not spread.

If the people of London are going to challenge the elites again, we will need to take on the centre. But first we need to develop the power (numerical or not) to do that. It seems that the obvious places to start to do that are the local front-lines where action has been most powerful in the last year.

Part 3: What can we do?

It is easy to get daunted, considering our weakness and the scale of forces against us – the immense mobilisation of wealth and power shaping the city, and the resignation of most of our neighbours. But it may be worth considering two points:

- Right now the enemy seems unassailable, but August 2011 showed that their control can be very fragile, they can lose their grip very quickly.

- This city is one of the key nodes of the global capitalist system. If we can find ways to fight the elites here, it could have impacts on struggles throughout the world.

We are starting from scratch. What do we have? A few friends and comrades, and some wider connections across the city and beyond. Some knowledge of the ground, of how to move about and do a few things. And, for the moment, largely due to our weakness and inactivity, and despite the intense surveillance of the city environment overall, we face very little repression (compared to comrades elsewhere), so have a pretty open field to meet, learn, start things.

In these conditions, it seems pointless to try and plot grand plans for London-wide action. Instead, it makes sense to experiment with relatively small projects – but where these are open-ended projects, i.e., they can transform and grow into new things as our strength and possibilities increase.

This was what worked well over the last year:

- first, modest autonomous projects: small groups of comrades making specific local interventions at the “fault lines”, a one-night fuck-parade, an anti-raids phone tree, a two month estate occupation;

- second, informal networking between these projects: groups share ideas and information and maybe some resources, learn, copy, adapt from each other, and can also work together on an ad hoc basis to mobilise in greater numbers where necessary;

- third, contamination: the most powerful projects cannot be isolated and contained, but connect with people beyond our existing circles.

So how do we identify potentially powerful projects to work on in the days to come?

Aims

First off, it might help to think about what we want to actually achieve from a project. Too often, we seem to skip this step. We don’t act but react, because we “just have to do something” in response to all the shit around us. So we just do what we know, follow old habits, routines, rituals – have a demo, hang a banner, put up a poster, break a window, create an organisation, whatever – without thinking much about why we do this.

It is easy to understand this, in a world where we are habituated into failure and resignation, in a world so out of step with our passions and convictions. Then, if we do think about “what we want”, maybe we fall into one of these two traps:

(a) we get lost in utopian visions of “another world”, that’s pleasant to dream about but not much use in guiding our projects now (unless we want to set out on a highway to disillusion and despair);

or (b), we go the other way and jump on board with whatever reformist programmes we come across (“defend council housing”), which are just as disconnected from the passions that thrill us and make us alive.

Are these the only ways to cast our desires? Or: can we set ourselves aims that both thrill and sustain us, and are actually realisable?

Life vs. control

Here is a proposal for a way of thinking about “intermediate aims” in the battle for London. What we are fighting, in all its many forms, is a system of control. Our immediate enemies are alliances of investors, financiers, developers, politicians, bureaucrats, philanthropists, cops, etc., who have various aims of profit, prestige, power, etc., but unite to assert their control over the spaces we live in.

Some mechanisms of control involve specialist agencies, e.g., security companies, police forces, local council inspectorates. Some are “internalised” in the population by promoting vigilantism, snitching, and generalised norms of respect for property, decency, “order”, civil obedience, etc.

The effect of their control, on our environments and our psyches, is: conformity, submissiveness, anxiety, blandness, sterility, homogeneity. Places and people become identical, formulaic, scared, so easily manageable. This is embodied in the neo-fascist architecture spreading all around us: dead zones of glass, steel, concrete, studded with a few tamed green patches, ordered into boxes, squares, grids, straight lines and sheer surfaces, all tracked by the ever-present cameras.

Against the city of control, we can imagine very different kinds of spaces and ways of life. Wildness, difference, decentralised creativity, a myriad of experiments, occupations, self-builds, eccentric gardens, over-growth, rebel quarters with their barricades and meeting places, no-go-zones for the powerful. Chaos, diversity, self-organisation – in short, life.

This is not a systematic answer, but a theme for thinking about the battle: life vs. control. The battle is always ongoing, there is never a final winner. Just as they seize a space and concrete it over, another area gets neglected and weeds break through the cracks.

For example, 1960s estates like the Aylesbury were also, of course, projects of control, although using a different model to today – the factory rather than the shopping mall. But inhabitants often managed to subvert control and uniformity: without romanticising the brutalist estates, which are shit in many ways, they could also be places of solidarity and rebellion. You cannot design out life and dis-order altogether, and we will certainly find exploitable flaws in the new architectures too.

We can imagine alive spaces, and we can make them real. A fuck-parade or mini-riot takes over a space and makes it alive for a moment. The Aylesbury occupation took over an abandoned area and started to make it live with new ideas and possibilities, for a couple of months. The residents resisting on the Aylesbury before and since have been bringing some life to the estate for much longer.

However wide they spread or long they last, all of these struggles are cracks in control, shoots of life, and part of an unending battle for freedom.

Just what kinds of projects we take on depends on our particular contexts and capacities, and our particular passions. But maybe we can conclude with two very broad points:

(i) form groups of comrades and take on projects

The high points of the year came from small groups of friends getting together, identifying a particular target or project, usually in a particular area, then going out and doing shit. The E15 mums, or the bunch of squatters who started the Aylesbury occupation, were little informal groups who dared to act. Call some people you know and trust together, talk about your passions and ideas, “brainstorm” together, map the area, identify enemy targets or opportunities for autonomy. Maybe find one particular project to focus on. Or, for the meantime, just meet regularly, walk the streets together, go out and do little things, get to know each other as you get to know the territory around you.

Of course, not all of us have groups of trusted friends to call on. London is a big, cold, alienating, isolating place, it’s hard to make connections and find comrades. Creating places and ways for people to meet each other is also going to be very important.

(ii) spread rebellion

Perhaps our greatest weakness, as discussed in this text, is that our projects didn’t spread. They became easily isolated and contained. On the Aylesbury, the fences were the symbol and embodiment of this containment. Elsewhere, the culture of the left acted as a containing force, sucking up energy and stifling projects in a ghetto of tired routines.

In many cases, a basic problem was this: we had little connection with people beyond small circles of anarchos, squatters, lefties, activists, etc. Our words and actions don’t reach beyond the same few hundred faces.

Many of our neighbours are discontented with the way things are in this city. Many are angry. Some are ready for a fight, but many are resigned: it may be shit, but what can you do about it, keep calm and carry on.

If we want to fight for life in this city, we need to get out of our comfortable circles and make connections with others who are up for a fight. And we need to provoke and spread rebellion wider, help break through the resignation, help crack the normality of control.

We need to find new ways to do this, because the old ones – our habits and rituals of organisation, propaganda and the rest – aren’t working. This pamphlet doesn’t have the answers either. To come up with some, we need to get together, get out in the streets, think, talk, learn, experiment, and dare.

Notes

i House price data compiled by the Greater London Assembly: http://data.london.gov.uk/housingmarket/

ii UBS Research: “Global Real Estate Bubble Index 2015”

iii Knight Frank:”Prime Global City Markets” 2014 http://content.knightfrank.com/research/678/documents/en/2014-2329.pdf

iv Ibid

v Knight Frank: “International Buyers in London” 2013 http://content.knightfrank.com/research/556/documents/en/oct-2013-1579.pdf

vi Knight Frank: “London Residential View” Autumn 2015 http://content.knightfrank.com/research/78/documents/en/autumn-2015-3173.pdf

vii Mayor of London: “Housing in London 2015” http://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/housing-london

viii Investment Property Forum (IPF): “Size and Structure of the UK Property Market 2013” http://www.indirex.com/uploads/Size_and_Structure_of_UK_Property_Market_2013_-_A_Decade_of_Change_Summary_Report.pdf

ix Mayor of London: “Housing in London 2015” http://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/housing-london

x Some of these sites are located in the G8 2012 “Map of the Capitalist West End”: https://www.anarchistaction.net/j11-carnival-against-capitalism/j11-map-of-the-capitalist-west-end/

xi This section is based on the much more detailed information collected at rottencity.org

xii Peter Linebaugh’s book “The London Hanged” tells the history, in lengthy but fascinating detail, of how the regime succeeded in making London governable over the course of the 18th century.

xiii For important anarchist views from this time of riots and possible insurrection, see: Alfredo Bonanno’s “From Riot to Insurrection”, and the introduction to the UK edition by Jean Weir; and Martin Wright’s “Let’s Open The Second Front”, originally in Class War newspaper. Both available at theanarchistlibrary.org.

xiv On the grassroots anti-poll tax movement, see Danny Burns’ book The Poll Tax Rebellion.

xv The events of the Aylesbury occupation were documented on the blog fightfortheaylesbury.wordpress.com, also see rabble.org.uk

xvi The account of East Street in this section is based on the reports from rabble.org.uk; for much more on immigration raids in London see network23.org/antiraids

xvii https://network23.org/antiraids/2015/11/01/raids-being-disrupted-every-week-say-immigration-services-union/

xviii This experience led to two texts published as “Death to Assemblies” written by people from the Aylesbury Estate occupation: http://ruinsofcapital.noblogs.org/against-assemblies/