Various Authors

Rulerless: The Inaugural Issue

The Community by Maheshwar Sinha

An Impartial Account of Where Bombs & Bullets are Alms for a Palmer

From the Water to the Walls of Guantanamo Bay

boy with a pot of golden clams by Martins Deep

Togetherness by Maheshwar Sinha

Herself: A Stranger Within by Heartless Widget

On Learning Coronation Spoons are a Thing

Poems From the Plague Year, Number Six:

Unquiet Summer

The Community by Maheshwar Sinha

Maheshwar Sinha is a self-taught artist from Ranchi, Jharkhand, India. Nature attracts him because it’s infinite and wild, containing neverending layers of meaning. His paintings have been published all across India and the world. He also writes short stories and novels in Hindi and English which have been extensively published.

Anarchy

by John Henry Mackay

Ever reviled, accursed, ne’er understood,

Thou art the grisly terror of our age.

“Wreck of all order,” cry the multitude,

“Art thou, and war and murder’s endless rage.”

O, let them cry. To them that ne’er have striven

The truth that lies behind a word to find,

To them the word’s right meaning was not given.

They shall continue blind among the blind.

But thou, O word, so clear, so strong, so pure,

Thou sayest all which I for goal have taken.

I give thee to the future! Thine secure

When each at least unto himself shall waken.

Comes it in sunshine? In the tempest’s thrill?

I cannot tell—but it the earth shall see!

I am an Anarchist! Wherefore I will

Not rule, and also ruled I will not be!

1888

A Letter From the Editor

Considering I’m a writer, I always seem to have an astounding lack of ability to come up with what to say in response to amazing events happening to or around me. What I can say is that when I was given the idea for an anarchist poetry magazine in early 2021 (which of course soon expanded into the idea for an anarchist poetry, short fiction, and visual art magazine), I had no idea that just a few months later I would be putting together 25 incredible literary and artistic works into an issue to be released at the start of August that same year.

What you are about to read is the culmination of 21 people’s hard work and effort. I adore every one of these anarchic, anti-capitalist, anti-colonialist pieces, and I believe they flow together seamlessly, in the anarchistic way: simultaneously as a collective and as individuals. Whether they cover the devastating effects of war, the joy of knowing that existence is temporary, or the possibilities of what is yet to come, they all invoke feelings of wonder, mystery, terror, love, death, and above all, life. In the world of The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin, the anarchist revolutionary Laia Asieo Odo wrote of “the Analogy,” a comparison between a society and a body, with individuals as cells. All those who have had a hand in the creation of this magazine are working to fulfill their cellular function, their self-determined life purpose.

I sincerely hope you enjoy this issue and read the whole thing through in order. Every featured writer and artist is amazing at what they do, and they all deserve as much love, support, and comradely solidarity as we can give.

Byron López Ellington

Founder and Editor

[Frontmatter]

What is Anarchism?

Anarchism is not chaos. It is not bombs and death. It is community, love, peace, and compassionate rebellion.

Anarchism is a set of political philosophies which advocate the abolition of all social hierarchy in favor of self-organization and self-management, both on the individual and communal levels. These liberated people would organize on a wider scale through federation and free association.

Anarchists believe that though humanity has the tendency to control and dominate, our tendency for cooperation and fairness is stronger. When separated from systems that encourage domination, people prefer to live in harmony.

Donate

We are committed to paying all contributors and keeping Rulerless free to read online, but that’s only possible with YOUR help! Small magazines, especially radical ones, always struggle. However, you are not obligated to do anything.

Donors get rewards at certain donation tiers — learn more, and find our donation links, here.

Letters

Send a response to any of the works in this issue and we may include it in the next! Please email letters to editors@rulerless.org with the subject line Response to [Piece or Contributor Name]. We reserve the right to edit letters before publishing them.

Copyright Information

While we are anarchists and therefore are against the concepts of copyright and intellectual property, the former is unfortunately the only reliable method of protecting one’s work against plagiarism in the present society, and as such we have decided not to revoke our contributors’ copyright. However, some may have revoked their own copyright or applied additional licenses to their work. In that case, the following statement may be rendered fully or partially null.

All works © 2021 by their respective creators.

Masthead

Editor

Byron López Ellington is a mestizo anarchist-communist writer and high schooler from so-called Texas. He founded Rulerless in February 2021 after realizing that there was no modern anarchist magazine with a focus on the literary arts in the English-speaking world. He is published or forthcoming in various literary magazines. You can find him at byronlopezellington.com and on Twitter @byronymous.

Thank you to Maya DelCanto-Ellington for her help with editing.

Onymous Donors

Special thanks to Maya DelCanto-Ellington, Byron Jerome Ellington, Joaquin Del Canto, Robert Evans, Ruth Reinhart, P.B. Gomez, Jerry Webberman, Neon, Steve the Great, Janessa Frykas, Tyler Mellander, D. Campbell, Sables, and Josh!

Donating does not affect your chances of being published in any way, shape, or form.

100% of profits from the first two issues of Rulerless will be donated to the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund.

New York’s Finest

BY P.B. GOMEZ

“Mr. Holmes?”

The sudden sound of his surname dragged James out of his head and into the present moment. He wasn’t sure how long he had been lost in thought. James hadn’t been processing anything for quite a while. While the judge had gone through his courtroom procedure, James had been thinking about the night of the protest. An echo of the energy and rage of the crowd still lingered with James, inspiring and heartbreaking all at once. That feeling was discordant with the atmosphere of the courtroom, a place sterilized of human emotion.

“I’m sorry, could you repeat that?” James asked.

The judge sighed and inhaled deeply, his eyes never lifting from a stack of court documents. “Mr. Holmes, do you understand the charges against you?”

“Yes.”

The judge’s gaze darted up from his bench. Staring intensely at James, he removed his reading glasses and leaned forward in his chair.

“Yes, Your Honor.”

Attempted murder of a police officer, it was a serious offense. James was facing the possibility of multiple decades in prison. He admitted that he was at the protest but denied being the man they were looking for. James was arrested a few weeks after the incident occured. It was swift and merciless. He remembered the utter terror of being thrown into a police SUV. He could recall nearly every word from the frantic conversation with his father through the phone at the NYPD precinct.

James’s case had been the subject of a lot of controversy. There were petitions on James’s behalf, money raised for his legal defense, but resources were spread thin. A lot of protestors were in legal trouble. James had spent the last few months on Rikers. His bail had been set far too high for anybody to have posted it.

The trial began. All of the major non-profits had refused to take up James’s case so he was instead represented by a young attorney from a small legal aid program based in the Bronx. She was only a few years out of the law program at Syracuse and while James thought that she was kind and seemed genuinely invested in his cause, her anxiety was palpable. They both knew she was out of her league going against New York City’s goliathan legal system. The judge was quick to overrule her objections and sustain those of the prosecution.

Representing the prosecution was a rising star in the District Attorney’s Office, a cum laude graduate of Columbia Law School who had won several high profile cases against illicit gambling rings in Queens. He was a firm prosecutor of the city’s strict gun control ordinance and a staunch ally of the NYPD. It was obvious he had political ambitions for the state legislature. When he called James to the stand, his questioning was direct and clinical, mostly focused on the facts of the day. When did James travel to the protest, why was he there, where was he, etcetera.

“Were you with anyone on the night of the incident?”

James thought about Naomi and worried for her. He didn’t blame her for not visiting him in jail or for not coming to the trial. She was keeping a low profile and James knew it was better that way. A mutual friend had kept him updated when they visited James in jail. Already Naomi was getting death threats online, and black cars with tinted windows often sat outside her apartment for hours at a time. She was an activist under a lot of scrutiny; willingly involving herself in this case was dangerous.

“No, I went to the protest alone.”

Then the prosecutor began to ask about the incident itself. His voice changed, questions came much more rapidly, each punctuated with accusatory hostility. There was a subtle shift in his body language. The prosecutor faced the witness booth, but he was no longer speaking to James. He was professing his conviction for all to hear, imparting adamantine disbelief in James’s innocence.

“Mr. Holmes, did you engage in violence at the protest?”

“No.” James believed this. What he had done was not violent, he was acting against violence.

“Did you assault an officer of the NYPD?”

“No.” James believed this, but he knew the law would disagree.

The prosecutor nodded. “I have no further questions for Mr. Holmes.”

The first piece of evidence was footage from the officer’s bodycam. James shifted in his chair to hide his anger. They had cut the footage so that the jury wouldn’t see the thick mist of pepper spray the officer had unleashed on the crowd a few minutes earlier, or the relentless barrage of rubber bullets fired at the backs of fleeing protestors.

All that was shown from the prosecution’s edit was a figure coming from the left side view of the camera, rushing at the officer before the camera malfunctioned in the struggle and the footage stopped. The prosecutor went back and paused on the moment with the clearest image of the attacker: a tall man with dark jeans and a t-shirt with a distinctive graphic. His face was concealed by a black bandana adorned with white geometric shapes and a red, flat-brimmed baseball hat.

“Mr. Holmes claims the man we see is not him. However, our evidence indicates Mr. Holmes matches every known characteristic of this suspect.” The prosecutor stopped for a moment. The thick coat of gel in his raven hair had weakened and a small strand of hair, a crack in his polish, fell forward on to his forehead. He gritted his teeth, exhaling deeply as he quickly stroked it back into place. “Mr. Holmes is the man we see attacking the officer, beyond any reasonable chance of coincidence,” he said, before returning to his table.

The onslaught of evidence came soon after. Key were the articles of clothing that the suspect wore in the footage. Although James had disposed of almost everything he brought to the protests, investigators had been able to link almost everything to him. They acquired deleted pictures from James’s phone and found him frequently wearing the same red hat as the suspect, an unusual color for Yankees’ branding. They had surveillance footage of him purchasing a black bandana with a similar pattern at a local bodega a few days before the incident. A single sock, the only thing James had neglected to throw away, was collected and analyzed, confirming James had been in contact with tear gas recently.

Most damning of all was the t-shirt, a black and white collage of police brutality victims over the years. It was how the police were able to track down James. Investigators found the artist who sold the shirt on their website, a tiny vendor who specialized in social justice pieces. Scouring through her transaction records, they discovered the shirt had been sold to 197 people in New York City: only 79 of which were men, only 52 were of the same ethnicity as the suspect, and only 12 had a similar height, weight, and approximate age. Half of these men had confirmed alibis, and only James’s cellphone had marked his location within a mile of the incident on the night of the attack.

Confident in his identification of James, the prosecutor was determined to establish his intent. More than a simple assault, he claimed James had every intention of fatally harming the officer. He highlighted a number of social media posts and text messages which demonstrated James’s disdain for law enforcement. More importantly, the prosecutor had procured another view of the incident.

Waiting as long as the law would let them, the District Attorney’s Office revealed, just before the trial began, that they had acquired footage from a nearby CCTV camera which showed not only another angle of the attack, but the suspect in the moments leading up to it. The prosecutor claimed it demonstrated how the attack was unprompted, premeditated, and unrestrained. He dimmed the lights and turned on the projector, straightening his jacket as it hummed to life.

The video showed the suspect standing on the sidewalk as the officer stood in the street, firing rubber bullets at targets off-screen. The suspect glanced down the street, presumably gauging how long it would take for the officer’s backup to catch up. Suddenly he charged, kicking the officer in the side before lunging for the weapon. After a brief struggle, more riot officers arrived, batons at the ready, and the suspect fled into the crowd. Even as all eyes in the courtroom focused on the prosecutor’s dissection of the suspect’s body language, James was transfixed on the image of the officer he had attacked.

It stood upon four legs, a headless body protected by thick sheets of dark blue polymer. Two vertical rows of sensors and cameras designated its face. Agile, motorized muscles were constantly in motion to keep its balance. On both sides of its body were small tanks of pepper spray, nearly empty by that point in the night. It carried a rectangular device upon its back, an automated 40mm grenade launcher loaded with rubber bullets, tear gas canisters, and flashbangs.

“We saw Mr. Holmes viciously rip away the officer’s service weapon, causing significant damage to the chassis. Now we see him clawing for the officer’s power source. That is a deliberate, directed attack that, if successful, would have easily destroyed Unit-1114. Mr. Holmes has clearly taken the time to learn enough about the officer’s design to know exactly how to inflict catastrophic damage.”

James watched the video of himself attacking the thing, a mechanical automaton to which the state had given life. The Law Enforcement Protection Act of 2029 had mandated that robotic units in service with law enforcement agencies were to be given the same legal status as human officers. No other robot had been given this level of personhood, just those who inflicted violence in the name of law and order. James still didn’t know what had happened that night, why he had done what he did. He knew he was putting himself at tremendous risk. He knew that even if he had been successful in destroying the thing, it would have made no difference. Protestors would still be brutalized, the wrongfully dead would not be returned to life. In that moment, however, something had stirred in James and the immense gravity of it all fell upon him suddenly. He was overcome with an indigent, sorrowful rage. He felt compelled to act, do something, no matter how irrational.

James looked upon the faces of the jury and wondered what they thought of all this. They were a diverse enough group, although none were from New York City (the judge wouldn’t let locals anywhere near the case). So many potential jurors had been thrown out, these were the select few candidates who were either good enough at hiding their biases or genuinely apathetic towards the whole thing. They sat in silence and listened to the prosecutor deliver his final condemnation of James, betraying nothing with their solemn, exhausted faces. Soon they would retire into the jury room and deliberate. Despite the fact that they held absolute control over his fate, James couldn’t help but feel a modicum of pity for them. They were trapped just like he was, beholden to a great machine that fabricated retribution and called it justice. Lost in this cold, mechanical labyrinth, James resigned himself.

P.B. Gomez (he/him) is a Mexican-American activist and writer. He is the founder of the Latino Rifle Association, which aims to provide politically progressive self-defense education to Latino communities. He begins law school this fall and plans to become a civil rights attorney. He shares his thoughts on Twitter, @MestizoLeftist.

The Rockets’ Red Glare

BY ANDRE F. PELTIER

O, the wild charge they made!”

—Alfred Tennyson, “The Charge of the Light Brigade”

to liberate Kuwait or Kuwaiti oil fields,

the United States dropped 15,237 tons of bombs

on the enemy. Of course, some of them

landed on friends, on hospitals, on schools,

but who’s counting? When war breaks out,

even when the war, like all wars,

is built upon lies, we allow for some civilian

casualties. These colors don’t run

after all, and we can’t expect

the Pentagon to deign to care.

We can’t ask the forces of freedom

to bend for a few children, a few invalids.

There was oil on the line. Death haunted

those bunkers in Amiriyah. His shadow

hid behind the refineries of Basra,

of Kharanj. Those Kurdish refugees

were forgotten. Just like the refugees

from Syria twenty years later.

Just like the lost children of Jordan,

of Palestine. Just like those brave children

who returned to Waycross, Lubbock,

Bakersfield to have children of their own

and to suffer the effects of the phantom

syndrome of the Gulf. You can’t make an omelet

without breaking some eggs though.

The children of these children, born with

kidney problems and a strong sense

of displaced emptiness.

Remember when we placed plows on the tanks

and ran over the Hussain Line? Death be

not proud unless you are in the service

of oil-lust. In that case, stand and salute.

Stand and be counted in service to your nation.

Know, too, that you will stand and be counted again.

We have our needs, our desires. We are thirsty

for crude oil and the crude matter of war.

When we wave our flag, we ride to victory

on the backs of those 400.

Andre F. Peltier is a Lecturer III at Eastern Michigan University where he has taught African American Literature, Afrofuturism, Science Fiction, Poetry, and Composition since 1998. He lives in Ypsilanti, Michigan, with his family. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in various literary journals and magazines. Twitter: @aandrefpeltier.

An Impartial Account of Where Bombs & Bullets are Alms for a Palmer

BY NWUGURU CHIDIEBERE SULLIVAN

of a shanty — a penitentiary for censured memories

& I came back unannounced to the

embrace of dyed torsos swollen with amnesia.

this is exactly what you get when every river/

every country you served your body to

as a token of loyalty purges it out in

return as a hefty carcass ladened with the

weight of memories provoked into a riot.

while these arms of mine were busy unclogging barebones

from the clasp of cobwebs on my entrance

my eyes waned to make room for such

lofty awe — an unclassified stripped tolerance

or a way of trying to establish familiarity

across every place that used to know

me.

this spot scented so much of forgetfulness until

I ambushed an unshared history &

snapshot every scene where brittle

bombs & bullets break through boys

in an incessant pursuit of a tavern

where it can freely breathe in a coup

like a Kenyan athlete clinching an

Olympic medal.

is this what the aftermath of war looks like? — a

barrel of barrenness slinging knuckles to

a vulture’s head or should I embark on

another crusade to establish an isotope of

everything we were before these thorny terms

sent us on a guilt trip across the Atlantic — a

journey that vacated our relics as a badly cultured broth

or should I apply for a loaned justice

with my life in the line as collateral?

now every place every place we tucked our names

before this wind swept off our feet pronounces us

as friendly foreigners.

everything everything we used to know

slithers away from our grip.

but if one’s country speaks at all of the

reassurance

of peace

of unity

of solace

of justice

then this place will be: no home. no home

Nwuguru Chidiebere Sullivan is a keen writer from Ebonyi State, Nigeria. He is a final year Medical Laboratory Science student and a Forward Prize nominee. He has works published or forthcoming in The Shore, Tilted House, B’K Mag, Juven Press, Rabid Oak, Wondrous Lit Mag, and several other publications. He can be reached on Twitter @wordpottersull1.

voice behind by Martins Deep

Martins Deep (he/him) is an emerging African poet, artist, and photographer, and currently a student of Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria. He has works in FIYAH, Agbowo Magazine, Barren Magazine, Stanchion Literary Magazine, and Typehouse Literary Magazine. He tweets @martinsdeep1.

From the Water to the Walls of Guantanamo Bay

BY BEN RIDDLE

as you are made to watch.

in desperation, maybe they are

reaching out to anyone

who will listen.

God white just so they could write

lies in legislation across

His skin—

by the poor, by the oppressed

just so He can answer

no—

like exposés, news reports,

like election promises

hoping to erode

while men cower under crosses,

clocks, while some are made

to not quite stand

the power of other men.

The flags do not

wait at half mast for

rather they watch like

surveillance cameras

pretending none of the walls

as you are made to watch.

Ben Riddle has been writing and performing for almost ten years now. His work has been published in Europe, Australia and the United States, and he has played stages on both sides of Australia, as well as internationally. These days, he mostly writes in his room, and mutters under his breath on buses.

Ozoemena

BY NWUGURU CHIDIEBERE SULLIVAN

our soul swells up with mutilated memories when a child

bears Ozoemena. such a name carries a harmless attempt to

exorcise a broken body that perches periodically on different wombs.

my grandmother said it’s also a way of shunning the memories

digging wounds into our heart of the country that served

panting pellets to her citizens & named them rebels for seeking

freedom. such pellets ended up cutting off the branches of

our family trees & denied us the pride of our pedigree; the very

last thing that sounded like a viable certificate to us. they convinced

us that living was too heavy until we attempted carrying the

dead bodies of our kinsmen away from vultures—we noticed that

death comes with extra weight. they coerced us to breathe

freely while lying close to bare corpses as if to say: death like birth

admires nudity. they brought crusade upon us & called it patriotism.

when one’s country is the mighty giant that plays hoax & war

with the throat of the armless men, the knees remember how dear

it is to the ground & what is a country if not this penitentiary we were

emptied into. //Ozoemena:

that’s how

we rebuke evil with the language it understands most. //Ozoemena:

that’s how

I pray whenever I remember the teary tales of how my country crumbled

a crescent orange sun with burning smoke & ignored the sky when it

petitioned for the repose of its loneliest occupant. till today, the sky

still wakes up with half of the yellow sun & bleeds Biafra as if to say:

this history still smells like a freshly dug sepulchre.

boy with a pot of golden clams by Martins Deep

History at Scale is Terror

BY MARGARET KILLJOY

like seraphs around our lord

Cutting, breaking, laughing, killing

Voices cry dissonant in the night

All our deeds lit by the cold moon

We don’t remember names

Just years of screaming

Centuries of pain

You can’t see the candles on the mantle

Hear the voices singing their discordant joy

You can’t see dawn, feel flesh

You can’t see us grow old in laughter

Pass bottles, touch hands

Not our lives, one by one

Not joy, broken by dawn

Swarming with six wings around our lord

And say don’t look at the fire at the smoke

At the screaming at the terror

Don’t look at the movement of life to death writ large

Don’t look at the bones that break from skin

Look at us, instead

Look at what we’ve done, who we’ve been, who we’ll be

One by one

Look at us one by one

Margaret Killjoy is a transfeminine author, musician, and podcaster living in the Appalachian mountains. She is the author of the Danielle Cain series of novellas and is the host of the community and individual preparedness podcast Live Like the World is Dying. She can be found on Twitter @magpiekilljoy.

Togetherness by Maheshwar Sinha

Ungrateful

BY BEN SONG

I am not a desperate soul, grateful just to have made it to the shining shores of the imperial core

I am not grateful for whites-only jobs

I am not grateful for a whites-only house

The imperial core is mine

And so too are all its problems

So too are all its sins

Ben Song is an anarchist activist from Dallas, Texas. He is a martial artist, SRA member, and Marine Corps veteran. He currently organizes with Dallas Food Not Bombs, Dallas Houseless Committee, and Fight for Black Lives. Ben teaches activists self defense, provides protest security, organizes, serves, and builds.

Confluence of Epochs

BY OLLY NZE

Hearts in my arms, ash in my mouth,

An echoing silence in my wake

watching steel wrought leviathans

pump fumes into the lungs of my children

did you hear me

It is now you come,

unfettered and in perfusion,

in answer to social media blackout

and highstreet boycotts.

And not even for your favour,

Fickle, fierce,

Would I pen another elegy for my heart.

Olly Nze is a queer writer living in Lagos, Nigeria. When he isn’t trying to navigate the madness of the city or tending to his cacti, he writes decent poetry and acceptable prose to keep himself sane. He has been published in The Audacity, and is the managing editor for the quarterly lit mag Second Skin Mag.

Herself: A Stranger Within by Heartless Widget

Heartless Widget is a visual artist based in the Midsouth. They are interested in the expression of human emotion in art and have been recognized by the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards, among others.

The Nomadic Birds

BY LISWINDIO APENDICAESAR

sweeping through a town scenery

so hastily, so rashly, and yet vibrate

like a melodious echo, or crashing

waves, filling the wintry air. I take

the signs—of the changing season,

of the departure, a farewell that will

be forgotten as life goes on. will

they all arrive at their destination,

where the warm sky welcomes them

with supper and concord? I wonder.

will they be reunited, after scattered

along the journey, or give up to

the frazzle and hopelessness

knowing the distance and incertitude?

before me a passage of time, hindered

by a mountain range, obscured by the

ripples on the river of a thousand miles.

I’m overwhelmed by the mere thought

of how injurious the path they must

be through.

because seasons won’t stop changing,

even there, and soon they’ll realize

it’s futile to escape the force of fate.

we all are tricked by a flowery dream,

or greener grassland on the other side.

and the struggle they deliberately choose

will betray them, turn into an icy road

failing the promised orchard.

never know how to lie a sweet sorrow.

the birds fly so high and so far,

gambling on the magnetic pole

like a premonition, absurd faith.

I pray upon the dusk, begging

for their safe trip: a salvation.

Liswindio Apendicaesar is a Indonesian writer and translator. He is a member of the editorial board of Pawon Literary Bulletin, and member of Intersastra’s translator team since 2019. His pieces have been published or are forthcoming in Voice and Verse Poetry Magazine, Oyez Review, The Thing Itself, etc.

On Learning Coronation Spoons are a Thing

BY J.V. SUMPTER

but where’s the coronation pan?

with plots, and yet she’s undercooked

of nations slaughtered by her fathers.

from queens that cannot spill new blood.

J.V. Sumpter is an assistant editor for Kelsay Books, Thera Books, and freelance clients. She has a BFA from the University of Evansville and recent publications in Selcouth Station, The New Welsh Review, Not Deer Magazine, Flyover Country, and Southchild Lit. Visit her Twitter @JVSReads.

Poems From the Plague Year, Number Six:

Unquiet Summer

BY PETER S. GOLDFINCH

Fire rising in the plague year’s crested nights

Lit from within—gold, orange, blue, and brilliant

The summer of cicadas swelling to answer the scream—

The scream of rebar twisting in the fever of that burning precinct

The scream of stuck pigs in their riot gear

Bricks, bottles, gas masks, and beatings

Of roaring crowds, milk-and-water eyes

Of midnight rivers marching black and fire-red—

Smoke pillars ascending as the shadow of the old world’s grotesqueries

loomed tremendous over twenty thousand hills

As the spreading plague passed from door to door

The year they expelled us in our millions from our homes

The year of hunger

The year of taut muscles, of holding our breaths

Waiting to see if those jackboots in their striding numbers

Could withstand the pressure of the mighty water

The mighty fire

Peter S. Goldfinch is a pseudonym for a neurodivergent ace anarchist debt peon and IWW member working on a PhD in a useless discipline. They believe a better world is possible. Unfortunately they are not a very interesting person outside of anarcho-clichéism, so they don’t have much to say about themselves.

Three Arrows by Viroraptor

Viro is a young native Vietnamese communist anarchist from Saigon. He got familiarized with anarchist thought while abroad and is committed to trying to popularize it among the progressive youth of his homeland through illustrations.

Estallido Social

BY DAVID SALAZAR

As the curfew lessens we head to the city

and see the spray paint that will not get

cleaned off because no one cares that much;

Chile despertó / ni una menos / ACAB

the circled red A in every other corner—

stop corruption, bring down the establishment

as the government only responds with tear gas.

You try to tell a leadership they’re leaking pus

and they will only put a bandage over it,

the sickness still lethal even when wrapped in gauze.

but will it fundamentally alter anything?

Will the people elected into writing a new foundation

manage to acquiesce into something stable?

when two grow in its place we still try to hack away at it.

Protests will spring up once again, the governed

ever so furious, and the government will act shocked.

We gave you everything you asked for, they say,

as they maim and kill and blind the righteous.

What more could you possibly want?

each circle carefully composed, each A scribbled on top.

We want a world where people who ask for more

aren’t punished with tear gas and bullets to the eye.

If the mere concept of our nation has to come down for that,

then so be it.

David Salazar (he/xe/she) is a teenage writer from Chile. He is a writer at Ogma Magazine and Ice Lolly Review. Xe has been published in various magazines and you can find xir on Twitter at @smalllredboy and on his website, davidvsalazar.weebly.com.

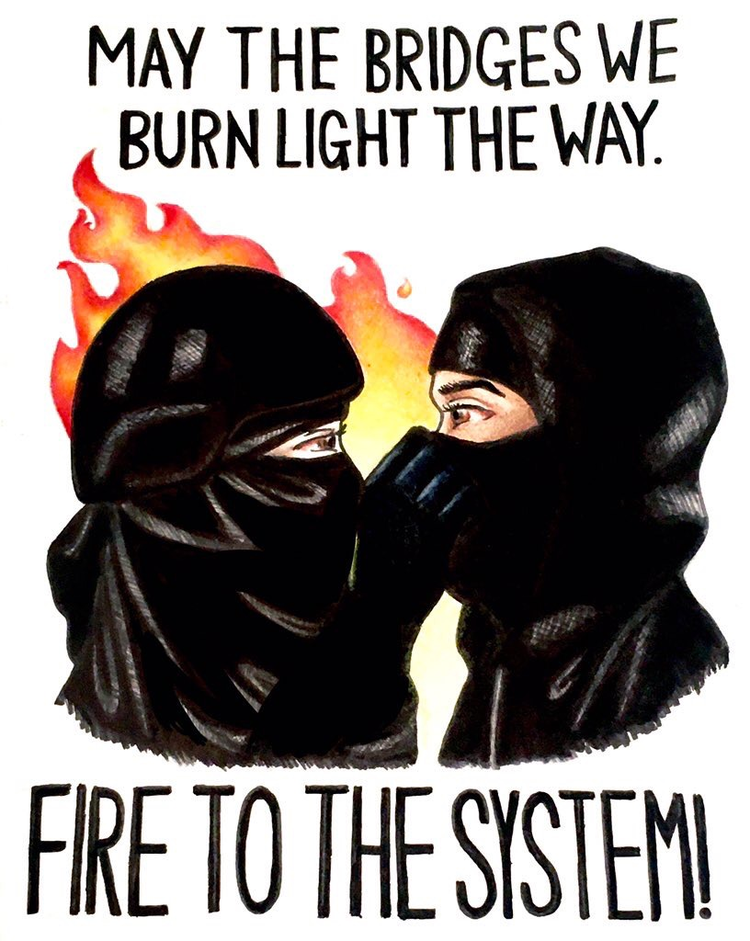

Fire to the System by Antifa Artist

Based in the Pacific Northwest, Antifa Artist is a queer disabled anarchist artist looking to radicalize and support communities through their artwork. They mostly focus on general themes of antifascism, Black liberation, and queer liberation. More of their artwork can be found at @antifa_artist on Instagram and Twitter.

Attack & Dethrone

BY FULGARA ETAOIN

Comes from faith in those above

They claim your siblings sinners

Unworthy of your tears

Will you let them strike us down?

That they allow us to object?

Where words have weight

They turn their backs

Only fire spurs action

Rides triumphant to our aid?

The devil is as awful as any angel

Offering only the same with a genteel smile

A slower quieter strangulation

Our bones become their bricks

Our blood for their mortar

Burn down their charnel palaces!

Tear down their ivory statues!

Cast aside its angels!

Raze heaven down to hell,

Where they can see their justice burn!

Don’t allow saints the lie of innocence,

Drown them in the blood on their hands!

Fulgara Etaoin is a trans woman, poet, and anarchist from the southern US.

A Shepherd With No Flock

BY JUSTIN(E) NORTON-KERTSON

Through labor and community,

Where all share in the joy and strife

Through famine and prosperity.

Where valued peace and unity

Are so much more than just mere talk,

Where privilege lacks impunity

The shepherd wanders with no flock.

Another world is possible

That’s not deeply rooted in greed.

The ocean’s not uncrossable,

An economy based on need,

Where one person’s wealth cannot exceed

What’s good for the whole block,

Authority there has no need,

The shepherd wanders with no flock.

Other people see it too,

The valley where ancestors bled

To create the world anew.

The lumpen wake to their debut,

Power over others mocked.

A revolutionary view,

The shepherd wanders with no flock.

A new world where we all can thrive,

with a foundation built on rock.

A place where birthright is deprived

The shepherd wanders with no flock.

Justin(e) Norton-Kertson is a queer/multigender author, poet, photographer, musician, and organizer. She currently lives in rural Oregon with his partner, cats, puppy, goats, and rabbits. They can be found on Twitter @jankwrites.

Give Me Summer

BY MARGARET KILLJOY

Stone worn till the name is gone

Or buried unmarked

Or scattered to the spring

Is it good that every bit of us fades in the sunlight

And those who remember us die

Can we rest if we are not forgotten

Do we live like shouts in a canyon

I want to be that statue, swallowed by the sand

Mighty, weeping

I want to rest in darkness

Dreamless, sleeping

Not now

I want to live like summer, fire and bright

I want to burn like forests, waking, running

I want tremors, I want trembling

Give me summer

Fire and bright

They are not stone

Let all living hold the sun the in their hands

And burn with it, fire and bright

Ode to the Spire

BY TIMI SANNI

about a spire, how it shoots upward,

like a sword in brave hands, like an

incarnate of Babel looking at God in

the face and daring Him. Such great

bravery within such thin, long body

that I imagine that God laughs and

sends down lightning to anoint its

silver tip. A certain grace must keep

one above such lofty heights. Look

at the long shadows of fear, draped

in sentient shades of darkness, here,

pulling at it, crown and length and

root. O how stubborn, how strong-

headed must you be to stand, like

true justice while the dank sickness

& deadweight of the world tries, with

every cursed touch of theirs, to pull

you down to rust. I want to stand

strong and true, like a spire, my head

in the clouds —oblivious to every

dark plot even as the deep, wild earth

turns in its scheming wake. If this

is what it means to be steadfast, I

want the doubting world beneath

my feet, and a steel rod for a spine.

Timi Sanni writes from Lagos, Nigeria. An NF2W poetry and fiction scholar, his work appears or is forthcoming in various journals and magazines. He is a reader for CRAFT Literary and Liminal Transit Review. He won the SprinNG Poetry Contest and Fitrah Review Short Story Prize in 2020. Find him on twitter @timisanni. Find him on twitter @timisanni.

THE DEVIL LIVES HERE

BY MARGARET KILLJOY

The devil lives at the bottom of Gossett’s Gorge. All us kids know it, which means all the parents must too, because they were kids once themselves. Knowing where the devil lives doesn’t seem like the kind of thing you’d ever forget.

I would have told you I wasn’t afraid of the devil, but I would have been lying, and the proof of it was that I’d never spent the night at the devil’s shack overlooking the gorge. I’d never crawled down that rope ladder, the spindly one that’s all fucked up and threadbare that goes right out over the edge. I’d never seen no one else stay the night or climb down either, and probably I would have gotten old like my parents without having ever done it. I would have, until Penny moved here to Mountain Springs. Until her stupid tagalong brother got taken. It wasn’t my fault.

I was fourteen years old in 1994. Kurt Cobain had just died and not one of us believed it was suicide. A grunge girl moved from the city to the house next door on my country road, and she had the right flannel, the right jeans, and a Mudhoney shirt. I’d never even heard of Mudhoney, but I was sure they were about to become my new favorite band. She was a year older than me, she never smiled, she never brushed her hair, and she was perfect in every way. Assuming she liked girls.

Her parents called her Samantha, and her middle school brat of a brother Chris called her Sam, but she told me her name was Penny and I wasn’t going to argue with a girl like her about something so meaningless as a name.

If you show another kid the ropes around here, you gotta mean it literally. You gotta show em the Three Trees up on Spineback, which are fat doug firs as old as God that’ve got rope bridges strung between. You gotta tell em how every two years or something, some kid falls to their death, usually drunk, usually kids from out of town. Every time it happens there’s a big fuss and someone takes the ropes down. Every time, the ropes go back up, and no one is sure who puts them up. You gotta show them the knots, because they’re weird knots, knots like no one else really knows how to tie, overly-elaborate. You gotta call them devil’s knots, too, if you want to sound spooky.

After you dare them to climb up after you into the Three Trees, you gotta take em to Sandy Creek. Nothing spooky about it, it’s just that there’s this squat old willow with a rope swing that’s been there for a hundred years but you can swing out into the widest, deepest, best part of the creek and it’s half the reason it’s alright to live in Mountain Springs.

Only then, after they’ve seen what’s good in town, do you take em to the devil’s shack. No one ever dies at the devil’s shack, you can assure your guests. No one ever dies there because no one ever stays the night, and no one ever climbs down that ladder. It’s the safest place in town if you respect that it’s evil.

The devil’s shack is just a little carriage house, like a big garage, and a single room adjacent. It’s all timber-framed and wood-paneled and it ain’t insulated for nothing, but I guess the devil doesn’t need to keep warm because the devil makes things warm.

I showed Penny the ropes. Chris came along, because of course he did. That’s what brats do. It’s no more right to be mad at a brat for tagalong than it’s right to be mad at a squirrel for stupid or a devil for death. Chris climbed the Three Trees, and he swung into Sandy Creek, and he kept being there when I wanted to talk to Penny about important stuff like if there was a grunge scene in Portland or, you know, her opinions on the current popularity of bisexuality among teenage girls.

The thing is, I saw Penny and I saw my chance at a perfect summer. Maybe a perfect life, but I couldn’t think that far ahead. I saw her and I riding our bikes down every trail on Spineback and finding every secluded glade. I saw her dark blue eyes and her messy brown hair close to my face. I saw us making pinkie swears that escalated to bloodsworn pacts. I saw us stealing a car and getting away with it. Hell, I saw us running away to Portland. Or staying in Mountain Springs. I didn’t care.

I’m telling you all this because I know how it sounds, because you probably saw the news reports about Chris. Maybe with everything else I’m telling you, you’re going to reach some unkind conclusions about me. Yes, it’s true, I wasn’t upset when Chris wasn’t there all the sudden. But for fuck’s sake, I was a fourteen-year-old girl in love. That kind of shit takes over your brain and makes its own decisions.

When we rode our bikes up the overgrown road to the devil’s shack, and we passed that rusted out little water tower with the old gold spraypaint that says “the devil lives here,” I started saying “devil take you” under my breath. Everyone knows if you say it a hundred times in less than a minute, the devil will do it, he’ll take whoever you’re thinking about. I didn’t even get to forty, though, because I’m not a monster. Nothing that happened was my fault.

“What is this place?” Penny asked, running forward. I couldn’t blame her, it’s a beautiful sight. The carriage house was nothing special, just old, but the one-room shack had the sharpest-peaked ceiling you’ll ever see, and no windows, and it’s right up against the cliff, and it just looks like magic.

“I told you,” I answered. “It’s the devil’s shack.”

“You said the devil lives at the bottom of the gorge,” she said as we went inside. The door was off its hinges again. Every couple of years, someone came by and fixed the place up. Probably some local dad just looking to scare the kids, maybe the same person who put up those rope bridges. But the devil’s shack got trashed pretty quick every time, since, you know, teenagers were around.

There was no back wall, just a ten-foot opening out over Gossett’s Gorge. Wind kicked in through the gap and it hit the cracks in the rafters just right for it to whistle. I was glad—the whistling roof is one of the coolest parts of the shack, but it wasn’t every day you’d get so lucky as to hear it.

“The devil lives at the bottom of the gorge,” I agreed. “This is like his emergency backup spot, in case the gorge gets flooded or an angel comes looking for him down there. I guess.”

“You can’t believe that,” Chris said. He almost never spoke when I was around, because I think he resented me as much as I resented him.

“Of course I believe it,” I said. I didn’t know if I was telling the truth or not. I’m not sure that anyone recounting fables or legends or laws believe they’re telling the truth, they just say the things they’ve heard because that makes them true. “If you don’t believe me, you can climb down there and prove it yourself.”

Chris looked suspiciously at the rope ladder. It really was a deathtrap, with or without the ghost story. In places, it was as thin as yarn. Other spots looked burned. Some of the rope rungs were ripped off entirely. The ladder didn’t even go all the way to the bottom of the gorge, just down maybe eighty feet before disappearing into a tiny patch of scrawny trees.

He looked back at me, then at his sister, then back at me. A grin cracked across his face, and damn fool kid did it. One second he was standing there, the next he wasn’t.

“Chris!” Penny shouted, down into the echo of the gorge.

“Riss!” the gorge shouted back.

I knew right then and there that I was more scared of not impressing Penny than I was of death or ghost stories. So I looked at her and I grinned the same dumb way that dumb Chris had dumb grinned.

I got on that rope ladder and started down. It took all my concentration to keep from panicking. A gust of wind moved me and the ladder several feet, and I clenched my teeth and my fists and kept climbing.

The cliff wasn’t completely vertical, thankfully, and in spots it was more like I was scrambling down a hill than just clinging for dear life.

I reached the end of the ladder, but there was no sign of Chris. Not in the trees, nor on the one-foot ledge they grew out of.

“I don’t see him!” I shouted up. Penny was already on her way down.

That’s when I noticed the cave.

Caves never have the kind of entrances you’d think they would. All the caves I’ve ever found or seen in the coastal range of Oregon were exposed to the world only by tiny little cracks and slivers and holes in the stone.

“Chris!” I shouted into the darkness. My voice echoed, a long ways back.

Penny landed beside me.

That’s when we heard the scream. Clear as a summer lake, we heard the scream. Loud as a waterfall, we heard the scream.

“Chris!” Penny shouted, then crawled into the darkness on her hands and knees.

I counted down from three to work up my nerve, but it didn’t work. I counted down from ten. At one, I crawled in after.

For a hundred feet or more we sloshed and slogged through mud and darkness on our hands and knees. Once my eyes adjusted, I saw the pale yellow flicker of firelight ahead and pretty quick I reached this place inside myself that was beyond fear. Like, anything could be ahead of us and it wasn’t going to be good but somehow crawling forward felt like the only possible option.

A sharp rock caught my shoulder, tore my favorite Nirvana shirt and my skin, and I kept crawling.

After a hundred feet or a million years we came out into a big open cave room. Three lanterns in a triangle on a natural shelf—an altar, I knew it without question—cast shadows more markedly than they cast light, and the whole room danced with fire and darkness.

No one was there.

Empty bottles were there, and empty cans of food, and the walls were painted up in teen graffiti, and a bare mattress sat on the ground inexplicably enough. All that was usual for every strange nook and cranny teenagers can sneak into to drink and fuck. There were other things, though, worse things. Inexplicable things. The skin of some animal nailed to a piece of plywood, rotting in a corner. A hunk of human hair, red and gray, stuck to the wall with some kind of paste. A wind chime of bones. Large bones. Horse, cow, deer, human, I couldn’t have told you. A wand, a raw chunk of quartz held to a stick with pine tar.

What caught my eye and held it, though, was a painting on the altar. It was on canvas, crudely stretched, and it was beautiful and to me it looked ancient. In an expert hand, someone had painted sixteen figures in a forest of fir. I counted them. Sixteen figures, most in shadows, some in light, all caught in religious ecstasy. The men were nude, the women were clothed, and one clothed figure bore a mouth full of fangs. All of them were dancing like how when people at a winery dance on the grapes, and they were covered to their shins and thighs in dark red juice but they were just tramping on the ground in the forest. Like the earth itself was giving up blood.

I stared and stared at that woman, with her mouth full of teeth. She looked like me. Not exactly like me. Just enough. Red hair. Freckles. Weird nose, weak chin, bright eyes. She had broader shoulders than me, though, and a higher forehead, and gray in her hair, and of course that mouth full of fangs.

Penny was screaming, frantic, searching for her brother, and I was staring at… look I have no way of proving this, I have no way of convincing you I’m telling the truth… I was staring at my father’s mother’s grandmother.

“Hold my belt,” Penny said, breaking my trance. I looked up wide eyed and confused. Penny had one of the three lanterns in her hand, and she’d pulled off the belt from her jeans, had one end wrapped around her fist.

“What?” I asked.

“There’re other passages. Only one’s big enough for anyone to get through I think. Chris has to be there. What if he fell, in the dark. Oh God. What if he fell in the dark. But it’s slippery, and it goes downhill, I don’t want to slip. You hold me here and I think I can get far enough to peer around the corner.”

Caves don’t make sense. I can’t say “corner of the room” because it wasn’t really a room and it didn’t really have a corner, but I walked to the corner of the room and braced myself against the wall and held onto Penny’s belt and she slipped down a passageway with a devil’s lantern. A moment later, I helped haul her back up.

“It’s just… more. More cave. I don’t know. What if he fell in the dark?”

She started mumbling, then. Just over and over. What if he fell in the dark.

And I couldn’t tell her he didn’t, because looking around the room, fell in the dark was about the best case scenario. I saw him buried in the earth so that cultists or witches or demons could tramp on the soil and his blood would bubble up onto their shins and thighs.

“We’ll go for help,” I said.

Penny nodded, numb, and we crawled back out of that cave together without Chris. I should have been worrying about Chris, or maybe I should have been worrying about Penny, but I was thinking about my great great great and her gray red hair and her teeth and the blood of the earth all splashed around and her teeth and I was thinking about her teeth.

It wasn’t two hours later before we got back there with help. Firefighters, mostly, with some cops trying to boss them around but too afraid to climb down the cliff. It was only two hours later before the cave was crawling with firefighters and four hours before a helicopter was cruising as low as it could in the gorge searching the river and its banks. As the sun set, our neighbors started combing the woods. By the next day professional cave rescue people, I don’t know what you call that job, they declared the cave clear, and some other people started dredging the river.

They didn’t find nothing in the woods but John the Hermit—people call him a bum but he’s a hermit and he only comes into town on Christmas eve on his bicycle to buy supplies and when he does he leaves dried flowers at every doorstep for ten miles in every direction. They arrested him.

They didn’t put cuffs on him, but they arrested him all the same, and he looked at the sheriff and he smiled big and said “the devil take you” as they put him in the car. In the end they didn’t charge him for Chris but I guess he put up a fuss at the station when they tried to put him in cage. Resisting arrest, assaulting an officer, obstruction of justice, and his defense in court was telling the judge “the devil take you” and that’s the last anyone saw John the Hermit, and we’re all the poorer without the flowers.

They didn’t find nothing in the river but trash and bones, and they were human bones, but they were old, from the twenties or thirties maybe. They weren’t Chris, so maybe human bones in the river would have been news some other month but we forgot about those bones soon off.

The real thing though, the real weird thing that fucked up my head and didn’t do my sense of reality any good was that they didn’t find anything in the cave, either. Anything. No lanterns, no wind chimes, no mattress. No graffiti. No painting. No Chris.

They took me and Penny to the doctor and they split us up and made us each tell our story to him over and over again until neither one of us had it straight and so some of the details didn’t line up, and I think if my Mom hadn’t come in screaming he would have put us both up in padded rooms.

The doctor was from out of town, an expert. His skin was as white as the moon, his hair whiter than the sun reflecting off the water. He was so white you could see the veins under his skin and somehow they looked white too. His teeth were white, his clothes were white, the office he was working out of was white, and he was fucking terrifying. He held power over me so casually, threatened me so casually.

For nights after, I thought about that doctor’s office as much as I thought about that cave. Two places where I almost lost my mind. Two places where I was standing on the edge like Penny standing at that passageway, trying not to fall, clinging to the belt for her life. In the cave at least she’d had me; in the doctor’s office it was just me and that man looking at each other, him trying to decide what was real and what wasn’t and whether I belonged in a padded room or whether my head and my memories were prison enough.

That’s how I wrote about it, anyway, in my journal. I liked to call them song lyrics but let’s be real it was poetry and shitty poetry at that, but let’s be real it was just me trying to get those things out of my head.

What if Chris fell in the dark?

Penny wasn’t allowed to see me, after that.

The doctor wouldn’t let me on the search teams, said I wasn’t healthy enough. He wanted me inside. I didn’t see why his opinion should have any bearing on the matter, but my mom apparently did, so I wasn’t on a search team.

My mom was working from home that summer, writing handwritten thank you letters on the behalf of politicians. Her and I weren’t real close but I spent a couple days helping her cook dinner and fix things around the house and the property and just kind of living in her shadow because I didn’t want to be alone.

“Where’s grandma from?” I asked my mom while she was changing the oil on the station wagon and I was holding the flashlight. “I mean, dad’s mom.”

See, I’d never met my dad’s mom before. She died of leukemia before I was born.

“Chicago,” she said.

“That’s where she was born? Where were her parents from?” I asked.

“Ohio.”

“Before that?”

“Mostly Scottish I think.”

“But did they ever live out here?”

“No, of course not.”

I knew if I dug too much further she’d start asking why I was asking, and I wasn’t going to talk to her about the painting, because I didn’t want to get locked up. I had to be careful. It was awful, not trusting my mom. But that doctor. What if she told the doctor.

It didn’t make sense. The painting, the cultists, Chris disappearing. None of it, nothing, made sense.

What if I fell in the dark?

The third night after it happened, I was lying in bed praying to the devil. “Please give him back,” I was saying. Everyone knows if you say it a hundred times in less than a minute, he has to do it. Problem is, he does it on his own timeline. And in his own way.

I decided to cover all my bases, so I prayed to the devil, and I prayed to God, and I went back and forth with both until I wasn’t always sure which I was doing.

I was praying to the devil though when the pebbles hit my window, and I went to look out and there was Penny in the side yard like sneaking out at night wasn’t a big deal, like there wasn’t a devil out there stealing children or a cop out there stealing hermits or a doctor out there threatening to steal us from each other and our families. She waved me down.

I popped out the window screen as quiet as I could and crossed over into the pine just outside. I love a pine tree, because they’re built like ladders. Sticky ladders.

“Hey,” I whispered when I reached the ground.

“Let’s go,” she said. She handed me a flashlight.

I didn’t ask where. I knew where. We got on bikes and took off, only turning on our lights when we were safely away from where our parents might see.

“Have you been having nightmares?” she asked.

“Yeah,” I said, even though I hadn’t. I don’t even know why admitting to nightmares would have been impressive, but I found myself saying it anyway. “Well, no. I haven’t been sleeping well enough to dream.”

“I’ve been having nightmares,” she said.

“What are they?”

“It’s Chris. He’s down there still. He fell, in the dark. In my dreams, he’s drinking from a little stream, and he’s eating moss and crickets, and he’s scared.”

“What about the graffiti, and the bones, and the painting?” I asked. “I… hate to say it but I think he got kidnapped. I think a cult was living down there, and they snuck out while we were getting help, and they cleaned it all up. It’s the only thing that makes sense.”

“Maybe we didn’t see all that stuff,” Penny said. “Maybe the doctor was right.”

I skidded my bike to a halt. Penny stopped too, looking back at me, confused.

“That doctor is not right. Not about what happened to us. Not about anything.”

Penny was crying. She came over. We walked our bikes to the side of the road and sat down, and she put her head onto my shoulder, and she cried a little more.

“Okay,” she said.

“We’ve got to believe ourselves,” I said. “We saw what we saw. They’re telling us we didn’t because they don’t want it to be true. Because it doesn’t make sense. But it was there.”

“I’ll believe you if you believe me,” Penny said.

“What do you need me to believe?” I asked.

“Chris is still alive.”

“Okay,” I said. “Okay. I’ll believe you.”

“I believe you too,” she said.

“I almost wish you didn’t.”

The moon was waning but large and we cast moonshadows across the road, and we sat like that for awhile before we kept biking to the devil’s shack.

The ladder was gone, but Penny had rope and we climbed down to the cave. We crawled in, and with flashlights and rope we searched more and more of the cave. Nothing. No one. Some soot, though, above the altar, was enough for me to believe myself. We’d seen what we’d seen.

On the altar in the first room, Penny left water and a peanut butter and jelly and potato chip sandwich. It didn’t make sense, but I didn’t argue. We crawled out of the cave, and we climbed back up to the devil’s shack, where you’re not supposed to go at night.

We stood in the shack and looked out over the gorge, and I didn’t know what the devil was and I didn’t know where he lived but maybe he lived in the gorge or maybe no one did.

We got back on our bikes and made it home just as birds started calling out, and I saw my dad leave the house and get to his truck on his way to work, his headlights cutting the rising fog of the morning. I scrambled up the pine and crawled into bed, every bit of me sore and cut and covered in mud and sap.

We went back the next night, and in the room, the main room with the altar and everything, only the crust remained of the sandwich.

“He’s alive,” Penny declared, and this time I didn’t have to work at it to believe her. “He hates the crust.”

“If we tell our parents,” I said.

“They won’t believe us,” Penny agreed. “Right to the padded room.”

“What do we do?”

“We find him,” Penny said.

We didn’t find him that night, though we spent hours in the cave. I crawled into bed at dawn.

Two weeks passed that way. Every night the sandwich was eaten. Penny left notes, each one taken. Penny left a pen and paper, but no message was ever written for us. We searched every inch of the cave we could reach. There were a few cracks too narrow even for us scattered around the place. There was a hole, the devil’s hole, that I could probably have fit down that went down and down and down but there was nowhere good to tie a rope.

We talked about spending the day in the cave, but our parents would notice us missing, freak out, send authorities, and we’d get dragged off to an institution without ever having found him.

Finally, on our fifteenth trip—we marked tallies on the paper we left—Penny told me her parents were going to have a funeral. In Portland. They were giving up and moving. Tomorrow.

“We have to tell your parents,” I said. “It doesn’t matter if we get locked up, if they find him.”

“No,” Penny said. “We have to find him.”

This time, she brought rock pitons and more rope. She’d shoplifted it all from the adventure sports store the next town over. She’d hitchhiked there. Fuck, she was perfect.

We made our way to the devil’s hole. Penny wouldn’t fit, so she helped me into a harness. She hammered pitons into cracks in the wall, and the noise was louder than anything had a right to be, each strike like a gunshot. She tied the rope to it, and that probably wasn’t enough to keep me safe.

“Ready?” she asked.

I nodded, and lowered myself into the hole. Head first, I decided. Fuck it. Better to see what’s coming.

It was like crawling vertically, in parts. Other parts I slid as Penny fed more rope. I went down. And down. And down.

The white noise of water rose up from below me. The hole went to the bottom of the gorge, I was certain.

I went down and down and then my flashlight caught a crystalline wall and the world exploded into light and suddenly my head broke free into a huge open chamber over a river. I braced myself as best I could, then gave one tug on the rope. One tug for stop, two for bring me up.

Crystals covered the walls, or maybe the walls themselves were crystals, or the entire world, entire universe, was those crystals, and there were facets to everything and everything caught the light. Everything shone.

There was a ledge jutting out from the wall, down close to the river, and there was the painting, and there was the hair, and there were bones and skins and crystals. No one was there, but I saw figures everywhere I looked.

I’d barely slept for weeks, my mind was torn apart by trauma, and peering into that room I had an epiphany, or I broke, or the devil broke me.

While I watched the water and the light and God or the devil flowed through the chamber I watched three people emerge, wading in the water. None of them were Chris. Two women and a man. Teenagers, maybe five years older than me. One had a Slayer shirt, and they were fifty feet below me and they had lanterns, one each, and they were laughing. I couldn’t hear them over the water but I could see their faces and they were laughing and they were passing a bottle and one held the crystal wand aloft. They waved at me, and they passed through the chamber, up the river the other side.

Two tugs, and Penny lifted me up, which took longer than I’d been alive. My head swam with thought and non-thought.

I tried to describe what I’d seen to Penny, but once she heard I hadn’t seen Chris she stopped listening, like I’d knocked the wind out of her.

We made it back to the first room, and she went somberly to the altar to leave the night’s sandwich.

Someone had written “The Three Trees” on the paper, while we’d been there.

Penny grabbed the paper, folded it, and put it in her pocket. She turned to me, her eyes alight. “Chris’s handwriting,” she said. “I used to copy it when I did his homework for him.”

I was still reeling from the room at the bottom of the devil’s hole and the world was upside down from where it had been and all the sudden I realized it wasn’t about me. None of this was about me. It wasn’t about impressing Penny. It wasn’t even about Penny, not really. It was about Chris. It was about finding that kid and making sure he didn’t die and making sure there were so many more years in front of him where he could talk his big sister into doing his homework and there were so many years of eating sandwiches and just living life not in a fucking cave in the bottom of Gosset’s Gorge and just…

“We have to find him,” I said, and for the first time I really meant it, not for my sake not even for Penny’s sake.

“No shit,” she said.

We made it out of the cave and up to our bikes but the sun was already on its way over the mountains.

“Shit,” Penny said. “My parents said we were gonna leave at dawn.”

“They’ll know you’re gone.”

“This is the first place they’ll look,” she said.

We got to our bikes and started up the trail but it wasn’t long before we heard people coming from in front of us and we ducked into the trees.

Penny’s parents, and that sheriff, the one who’d stolen John the Hermit, the only person I’d ever seen actually steal a person with my own eyes.

We waited breathless for them to pass then hurried to the road. It was an hour on bike to the Three Trees, and we got there in forty-five. The sun was over the mountains now, filtered through the forest. The ropes hung like they always hung, knotted strange, down from the boughs of the trees.

I hurried up the rope, and Penny came after.

There was the tagalong, sitting calm as death on the platform, covered with mud and pine, whistling a dissonant tune.

“Chris,” Penny said.

He didn’t stop whistling, and Penny sat down next to him.

“Chris,” Penny said. He didn’t respond.

She freaked out. I didn’t blame her. “Chris,” she shouted, pounding his chest with her fists.

I sat across from him, and I looked into his eyes, and they caught light like crystals.

“I saw the devil’s chamber,” I said. “It’s beautiful.”

Chris looked at me, and stopped whistling.

“Did you see the devil’s maidens? The three?” He asked.

“Penny thought you fell,” I said, instead of answering, “in the dark. But you didn’t, did you?”

“I was rescued,” he said.

“By the maidens.”

“By the maidens,” he agreed. “They took me to the chamber and I saw the light and I heard the water and I went under the water. I learned the truth. The devil isn’t real, and we are his maidens, and for as long as there’s been a world there’s been the devil.”

“The painting?” I asked.

“As long as there’s been a world there’s been a devil, as long as there’s been a devil there’s been his maidens. We are, each of us, the devil’s maidens. A million names, a million meanings, a million cultures, but a devil, a devil, a world, a world, a maiden, a maiden, and blood.”

I nodded.

“Is that what you’ll be?” I asked. “A servant to the devil?”

“Yes,” he answered. He looked at me. “Will you?”

When he asked me, I felt like I was still dangling in that room of light. I’d never felt more real, more connected to everything, to my body, to death, than I had in that moment.

“Yes. I will be the devil’s maiden.”

“Will you tie the knots that hold the trees?” he asked.

“I will.”

“Will you fix the door that holds us warm?” he asked.

“I will.”

“Will you guard the room that sings of the river and light?” he asked.

“I will.”

“For all time?” he asked.

“No,” I answered.

“No?”

“Look at me, Chris,” I said. Chris looked at me. “I will be the devil’s maiden, same as you, same as those three, but that’s not all I’ll be. I’ll be myself, too.”

“You’re allowed to do that?” He was suddenly a child again.

“We’re allowed to do anything we want,” I told him. “The devil isn’t real. God isn’t real. The world is real, and we are real, and we can serve anything we’d like. We can serve God, the devil, the earth, ourselves, each other.”

“You served me,” Chris said. “For these past two weeks, you served me.”

“Penny did,” I said. “I served her. No, I served myself. I should have been serving her, or you, but it’s all the same, too.”

Penny put her arm around her brother, and he collapsed into her, crying. Whatever spell had held him was broken.

“I want to go home,” he whispered.

“Then we’ll go home,” Penny said.

I didn’t see Penny for three days after that. The reunion was kind of all-consuming for her family. But on the fourth day, late in the evening, she met me at my front door, and she had sleeping bags.

“Tell your parents you and I are going camping,” she said.

“I don’t know if my mom will let me,” I said.

“Okay, then don’t tell them,” she answered.

“Mom, I’m going camping with Penny! Be back tomorrow!” I shouted, then Penny grabbed my hand and the two of us took off running before my mom could stop us.

If she really wanted, she could have found us. She could have figured out where we were going. We went to the devil’s shack.

This time, Chris didn’t come with us.

We went to the devil’s shack, and the rafters were whistling. They were whistling that dissonant tune Chris had been singing.

“What are we doing here?” I asked.

“We’re going to meet the maidens,” Penny said. “And thank them for taking care of my brother.”

“What do you mean?”

“I talked to Chris more,” Penny said. “He really had fallen, in the dark. That was the scream we heard. The maidens, they rescued him. Washed his wounds, kept him fed and warm. Brainwashed him a little yeah sure, but they saved his life, and they let him go, too.”

“Oh,” I said.

“Besides,” Penny said, “I think you promised to work with them.”

“Well, maybe a little,” I agreed.

She kissed me on the cheek.

“You’re a charming enough maiden,” she said.

“Tell me,” I asked, once we laid our sleeping bags on the floor of the Devil’s Shack, the one place one must never, ever sleep, “what’s your opinion on the current popularity of bisexuality among teenaged girls?”

fierro by Alba Esc Santos

Alba Esc Santos is a non-binary Latinx mixed-media artist. Sometimes they feel like an artist and sometimes they don’t. Alba’s work is motivated by many attempts to steal from life those moments where the established mode of being has yet to extend its tendrils; in that gray is where you can find them.

Contributor Bios

Alba Esc Santos is a non-binary Latinx mixed-media artist. Sometimes they feel like an artist and sometimes they don’t. Alba’s work is motivated by many attempts to steal from life those moments where the established mode of being has yet to extend its tendrils; in that gray is where you can find them.

Credits: fierro

Andre F. Peltier is a Lecturer III at Eastern Michigan University where he has taught African American Literature, Afrofuturism, Science Fiction, Poetry, and Composition since 1998. He lives in Ypsilanti, Michigan, with his family. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in various literary journals and magazines. Twitter: @aandrefpeltier.

Credits: “The Rockets’ Red Glare”

Based in the Pacific Northwest, Antifa Artist is a queer disabled anarchist artist looking to radicalize and support communities through their artwork. They mostly focus on general themes of antifascism, Black liberation, and queer liberation. More of their artwork can be found at @antifa_artist on Instagram and Twitter.

Credits: Fire to the System

Ben Riddle has been writing and performing for almost ten years now. His work has been published in Europe, Australia, and the United States, and he has played stages on both sides of Australia, as well as internationally. These days, he mostly writes in his room, and mutters under his breath on buses.

Credits: “From the Water to the Walls of Guantanamo Bay”

Ben Song is an anarchist activist from Dallas, Texas. He is a martial artist, SRA member, and Marine Corps veteran. He currently organizes with Dallas Food Not Bombs, Dallas Houseless Committee, and Fight for Black Lives. Ben teaches activists self defense, provides protest security, organizes, serves, and builds.

Credits: “Ungrateful”

David Salazar (he/xe/she) is a teenage writer from Chile. He is a writer at Ogma Magazine and Ice Lolly Review. Xe has been published in various magazines and you can find xir on Twitter at @smalllredboy and on his website, https://davidvsalazar.weebly.com.

Credits: “Estallido Social”

Fulgara Etaoin is a trans woman, poet, and anarchist from the southern US.

Credits: “Attack & Dethrone”

Heartless Widget is an artist from Memphis, Tennessee. He is interested in the anatomy of the face and its implication on human relation. His work has been recognized by the National Scholastic Art and Writing Awards and has been exhibited at the Memphis International Airport, Brooks Museum of Art, and more.

Credits: Herself: A Stranger Within

J.V. Sumpter is an assistant editor for Kelsay Books, Thera Books, and freelance clients. She has a BFA from the University of Evansville and recent publications in Selcouth Station, The New Welsh Review, Not Deer Magazine, Flyover Country, and Southchild Lit. Visit her Twitter @JVSReads.

Credits: “On Learning Coronation Spoons Are a Thing”

Justin(e) Norton-Kertson is a queer/multigender author, poet, photographer, musician, and organizer. She currently lives in rural Oregon with his partner, cats, puppy, goats, and rabbits. They can be found on Twitter @countryjim13.

Credits: “A Shepherd with No Flock”

Liswindio Apendicaesar is a Indonesian writer and translator. He is a member of the editorial board of Pawon Literary Bulletin, and member of Intersastra’s translator team since 2019. His pieces have been published or are forthcoming in Voice and Verse Poetry Magazine, Oyez Review, The Thing Itself, etc.

Credits: “The Nomadic Birds”

Maheshwar Sinha is a self-taught artist from Ranchi, Jharkhand, India. Nature attracts him because it’s infinite and wild, containing neverending layers of meaning. His paintings have been published all across India and the world. He also writes short stories and novels in Hindi and English which have been extensively published.

Credits: The Community and Togetherness

Margaret Killjoy is a transfeminine author, musician, and podcaster living in the Appalachian mountains. She is the author of the Danielle Cain series of novellas and is the host of the community and individual preparedness podcast Live Like the World Is Dying. She can be found on Twitter @magpiekilljoy.

Credits: “History at Scale is Terror,” “Give Me Summer,” and “The Devil Lives Here”

Martins Deep (he/him) is an emerging African poet, artist, and photographer, and currently a student of Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria. He has works in FIYAH, Agbowo Magazine, Barren Magazine, Stanchion Literary Magazine, and Typehouse Literary Magazine. He tweets @martinsdeep1.

Credits: voice behind and boy with a pot of golden clams

Nwuguru Chidiebere Sullivan is a keen writer from Ebonyi State, Nigeria. He is a final year Medical Laboratory Science student and a Forward Prize nominee. He has works published or forthcoming in The Shore, Tilted House, B’K Mag, Juven Press, Rabid Oak, Wondrous Lit Mag, and several other publications. He can be reached on Twitter @wordpottersull1.

Credits: “An Impartial Account of Where Bombs & Bullets Are Alms for A Palmer” and “Ozoemena”

Olly Nze is a queer writer living in Lagos, Nigeria. When he isn’t trying to navigate the madness of the city or tending to his cacti, he writes decent poetry and acceptable prose to keep himself sane. He has been published in The Audacity, and is the managing editor for the quarterly lit mag Second Skin Mag.

Credits: “Untitled”

P.B. Gomez (he/him) is a Mexican-American activist and writer. He is the founder of the Latino Rifle Association, which aims to provide politically progressive self-defense education to Latino communities. He begins law school this fall and plans to become a civil rights attorney. He shares his thoughts on Twitter, @MestizoLeftist.

Credits: “New York’s Finest”

Peter S. Goldfinch is a pseudonym for a neurodivergent ace anarchist debt peon and IWW member working on a PhD in a useless discipline. They believe a better world is possible. Unfortunately they are not a very interesting person outside of anarcho-clichéism, so they don’t have much to say about themselves.

Credits: “Poems from the Plague Year, Number Six: Unquiet Summer”

Timi Sanni writes from Lagos, Nigeria. An NF2W poetry and fiction scholar, his work appears or is forthcoming in various journals and magazines. He is a reader for CRAFT Literary and Liminal Transit Review. He won the SprinNG Poetry Contest and Fitrah Review Short Story Prize in 2020. Find him on Twitter @timisanni.

Credits: “Ode to the Spire”

Viroraptor is a young native Vietnamese communist anarchist from Saigon. He got familiarized with anarchist thought while abroad and is committed to trying to popularize it among the progressive youth of his homeland through illustrations.

Credits: Three Arrows

“We live in capitalism; its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.”

—Ursula K. Le Guin