Richard Parry

The Bonnot Gang

The Story Of The French Illegalists

1. From illegality to illegalism

Collapse of the Romainville commune

Accidental death of an anarchist

Science on the side of the Proletariat

10. Kings of the road (part two)

A letter from Lorulot to Armand about Kibalchich's conduct at the trial

A letter from Victor Kibalchich about his conduct at the trial

ON THE EVE of World War One a number of young anarchists came together in Paris determined to settle scores with bourgeois society. Their exploits were to become legendary.

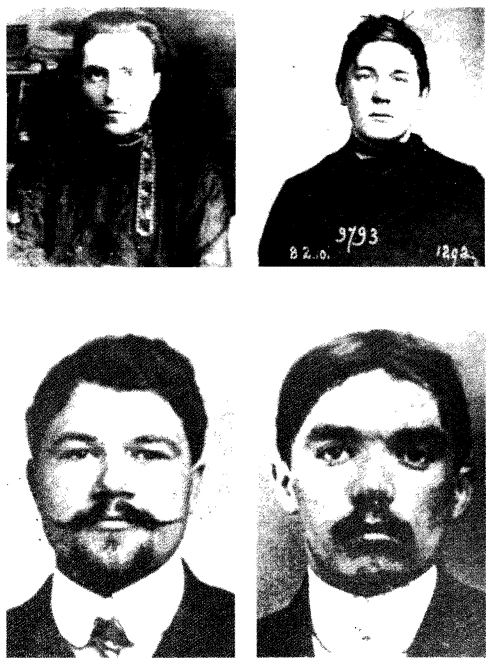

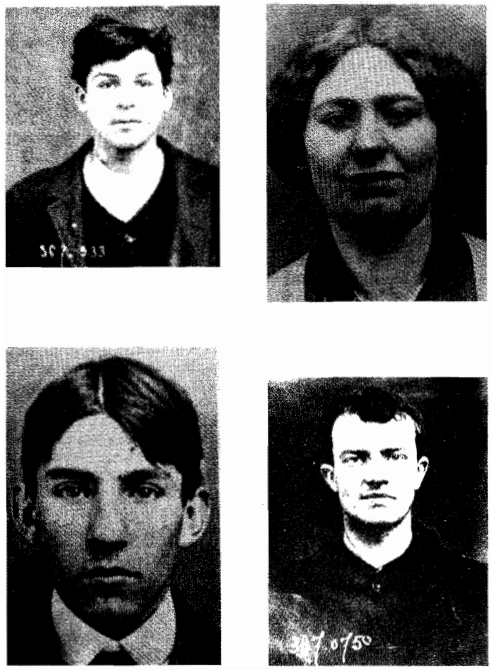

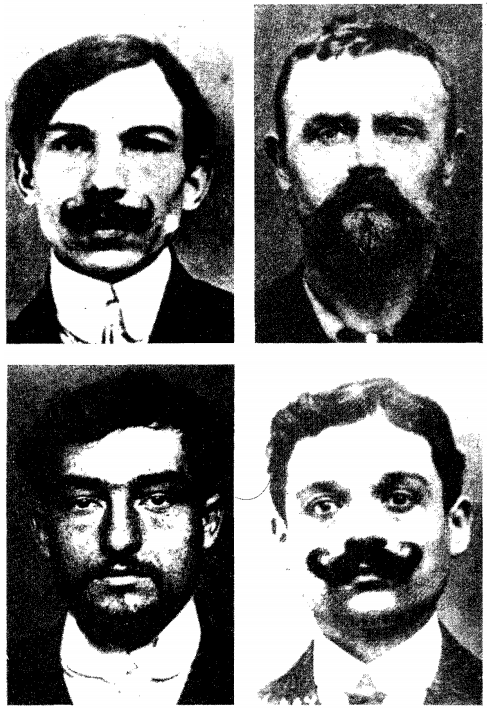

The French press dubbed them 'The Bonnot Gang' after the oldest 'member', Jules Bonnot, a thirty-one year-old mechanic and professional crook who had recently arrived from Lyon. The other main characters, Octave Garnier, Raymond Callemin, René Valet, Elie Monier and André Soudy were all in their very early twenties. A host of other comrades (i.e. those of an anarchist persuasion) played roles that were relevant to the main story, and I apologize in advance for the plethora of names with which the narrative abounds.

The so-called 'gang', however, had neither a name nor leaders, although it seems that Bonnot and Garnier played the principal motivating roles. They were not a close-knit criminal band in the classical style, but rather a union of egoists associated for a common purpose. Amongst comrades they were known as 'illegalists', which signified more than the simple fact that they carried out illegal acts.

Illegal activity has always been part of the anarchist tradition, especially in France, and so the story begins with a brief sketch of the theory and practice of illegality within the movement before the turn of the century. The illegalists in this study, however, differed from the activists of previous years in that they had a quite different conception of the purpose of illegal activity.

As anarchist individualists, they came from a milieu whose most important theoretical inspiration was undoubtedly Max Stirner — whose work The Ego and Its Own remains the most powerful negation of the State, and affirmation of the individual, to date. Young anarchists took up Stirner's ideas with relish, and the hybrid 'anarchist-individualism' was born as a new and vigorous current within the anarchist movement.

In Paris, this milieu was centred on the weekly paper l'anarchie and the Causeries Populaires (regular discussion groups meeting in several different locations in and around the capital each week), both of which were founded by Albert Libertad and his associates. It was here that 'illegalism' found fertile soil and took root, such that the subsequent history of the illegalists is closely bound up with the history of l'anarchie.

One of the editors of this weekly was Victor Kibalchich, later to be better known as Victor Serge, the pro-Bolshevik writer and opponent of Stalinism. At the time of this story, however, he was not just a close associate of several 'illegalists' but was also one of the most outspoken of the anarchist-individualists, and editor of l'anarchie to boot. As such, his early career as a revolutionary is a central thread in the story of the Bonnot Gang, although this period of his life was glossed over by Serge himself and has been subsequently ignored by contemporary political writers who wish to keep him as 'their own'. It therefore seems more fitting for the purposes of this narrative to use his nom de plume, Le Rétif, or his real name, Kibalchich, rather than 'Serge', a pseudonym he did not adopt until five years after he found himself fighting for his life as a defendant in the mass trial of 1913.

Despite their sanguinary exploits, the 'Bonnot Gang' remain as much a chapter in the history of anarchism as the activities of Ravachol in France or the Durruti Column in Spain. To push their story to one side, or to treat it as a 'dark side' of anarchism to be glossed over or ignored, is to be unfaithful to the history of anarchism as a whole. On the other hand, however, those who would glamorize or make heroes of the illegalists are failing to see that they were not at all extraordinary people or anarchist supermen. What is remarkable about them is that although as young sons of toil their lives could easily have led to the slavery of the factory or the trenches, they chose not to resign themselves to such a fate.

This book is not a novel; the novelist's approach certainly adds dramatic tension and vigour, but I would not like to be guilty of spurious characterizations. In any case, I certainly could not have done better than Malcolm Menzies' book En Exil Chez Les Hommes (unfortunately only available in French) and so have written what I hope will pass as a 'history'.

Here, the question of 'historical truth' rears its ugly head: some of the story remains very obscure for several reasons. To begin with, none of the surviving participants admitted their guilt, at least until after the end of the subsequent mass trial. It was part of the anarchist code never to admit to anything or give information to the authorities. Equally, it was almost a duty to help other comrades in need, and if this meant perjury to save them from bourgeois justice, then so be it. Hence the difficulty in knowing who was telling 'the truth'. Those who afterwards wrote short 'memoirs' often glamorized or ridiculed persons or events, partly to satisfy their own egos and partly at the behest of gutter-press sub-editors.

In the trial itself there were over two hundred witnesses, mainly anarchists for the defence, and presumably law-abiding citizens for the prosecution. Much evidence from the latter was contradictory. While most were probably telling the truth as far as they could remember, others had told an inaccurate version so many times that either they believed it themselves, or, under police pressure, they found it too late and too embarrassing to withdraw it. A few were certainly motivated either by private, or a sense of social, revenge.

Then of course there was the evidence of the police who, it was revealed during the course of the trial, had pressurized witnesses and fabricated evidence in order to make the case appear neat and tidy and secure easy convictions. Some policemen in their reports either lied to conceal their blunders, or exaggerated the importance of their role in order to promote their careers.

Lastly, there was the press, that guardian of bourgeois morality, though not averse to sniping at the police, depending on which administration was in power. Some newspapers gave space to the auto-bandits almost daily for six months, yet they were usually forced to rely on police reports which often withheld news or supplied deliberate misinformation. This, coupled with that normal journalistic practice of creating stories out of nothing, meant that many articles which appeared were confused, exaggerated or fictitious.

In other words, I have had to select my material and make a judicious melange from conflicting sources. In the good old tradition of liberal historiography the story that follows is very much my own.

Richard Parry

London, 1986

1. From illegality to illegalism

"Property is theft. Property is liberty."

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-65)

Making a virtue of necessity

ALMOST ALL the illegalists who were associated with the Bonnot Gang were born in the late 1880s or early '90s, into a society completely torn by class division. Above all, it was the suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871 that had consolidated the climate of mutual hatred between the workers and the bourgeoisie. The Commune, a minimal attempt at social-democracy by workers and impoverished petit-bourgeois, was drowned in the blood of thirty thousand people by an army acting on the instructions of a ruling class infuriated at this challenge to their monopoly of power. The bloody repression of the Commune marked the birth of the Third Republic and served as a constant reminder to workers that they could expect nothing from this 'New Order' except the most brutal repression.

The memory of these tragic events of 1871 left a rich legacy in class-hatred, one with which French anarchists identified and which they hoped to exploit. With revolutionary organizations outlawed, and all forms of working class political activity banned, anarchists and trade-unionists were forced to operate in ways that were clandestine or outrightly illegal. As such modes of behaviour became the accepted norm, anarchists acquired a taste for illegality which lingered on into the 1900s when the Bonnot Gang came of age.

The 1870s were lean years for revolutionaries, and it was not until the 1880s that French anarchism really took off. The amnesty granted to deported Communards in 1880 signaled the return of thousands of hardened revolutionaries from exile in New Caledonia. A strong and fresh impetus was given to the revolutionary movement and “Paris quivered with excitement”, according to one police observer. Within a couple of years there were an estimated forty anarchist groups in France with two thousand five hundred active members, including perhaps five hundred in Paris and in Bonnot's town of Lyon. Within a decade, the anarchist press was selling over ten thousand papers a week. Anarchist groups adopted names such as 'Hate', 'Dynamite', 'The Sword', 'Viper', 'The Panther of Batignolles' and 'The Terror of La Ciotat' as an indication of their aggressive stance towards bourgeois society. At the same time, anarchist theory was made more acceptable by proposing the 'commune' as the practical base for the organization of the new society, as opposed to the 'collective'; 'need' became the new criterion for the distribution of goods and services, which were to be freely available to all, regardless of the work each person had done; anarcho-communism was born.

All anarchist activity and propaganda was centred on the class struggle, which was especially bitter and violent up to the mid-1890s. A miners' strike in Montceau provoked the burning and pillage of religious schools and chapels, and ended in the dynamiting of churches and managers' houses. Many other strikes involved violent clashes with police or troops and occasionally coalesced into riots and looting. The anarchist belief in violent direct action, formulated in the policy of 'propaganda by the deed' (rather than by the word), reflected the particular bitterness of these struggles. Propaganda by deed was translated into action in three forms: insurrection, assassination, and bombing. The insurrectionary method, which had proved something of a fiasco in Spain and Italy in the 1870s, was not tried out in France. Instead, assassination became the principal weapon of revenge against the bourgeoisie and the figureheads of the State. The first wave of attempted assassinations was directed against political leaders throughout Europe: in the five years from 1878 there were attempts on the lives of the German Kaiser, the Kings of Spain and Italy, and the French Prime Minister. The killing of the Russian Emperor, Alexander II, by the 'People's Will' was, however, the only successful revolutionary execution of a reigning monarch.

There was a hiatus of ten years until the next batch of attempts on heads of State; in 1894 the French Prime Minister was stabbed to death, and the next decade saw the spectacular demise of a Spanish Prime Minister, an Italian King, an Austrian Empress and a President of the United States. In France, the gap between these two waves of political assassinations was marked by attempts on the lives of upholders of the ruling order in a more general sense. This time the victims were employers who had given workers the sack, a wealthy doctor, a priest, and brokers in the Paris Stock Exchange. The bourgeoisie began to be more than a little concerned when the anarchist 'propagandists by deed' began to use dynamite: in 1892 over one thousand explosions were reported in Europe. In Paris, bombs exploded in the Chamber of Deputies, a police station, an army barracks, a bourgeois café, a judge's house, and the residence of the Public Prosecutor.

It was ordinary workers rather than 'professional' activists who carried out these acts of propaganda, although such desperate measures were habitually praised in the columns of the anarchist press. The 'terrorists' of the early 1890s were mainly poor working class men—a cabinetmaker, a dyer, a shoemaker, for example—unable to get any work, often with a family to support, bitter at the injustice they had suffered, and sympathetic to anarchism. This was one aspect of the world into which most of the illegalists were born; Bonnot was in his mid-teens when the spectacular bombings took place, causing a panic among the bourgeoisie not to be repeated until he himself became France's 'Public Enemy Number One'.

As the anarchist desire for the abolition of the State was translated onto an immediate, practical level through individual acts of assassination and bombing, so the wish for the 'expropriation of the expropriators' was reduced to individual acts of 're-appropriation' of bourgeois property. This was the theory of la reprise individuelle, whose most celebrated practitioners were Clément Duval and Marius Jacob; the infamous Ravachol, who went to the guillotine in 1894 singing the scandalous anticlerical song Père Duchesne, was known more for his bombings than his burglaries.

Clément Duval, twice wounded in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, spent four of the following ten years in hospital, and was rendered permanently unfit for his trade as an iron worker. He was imprisoned for a year after having been caught stealing eighty francs from his employer, in order to buy desperately-needed food and medicine for his family. On his release he threw in his lot with the hardened working class anarchists of 'The Panther of Batignolles' and began a short-lived life of crime. In October 1886 he set fire to the mansion of a wealthy Parisian socialite, having first burgled it of fifteen thousand francs, but he was caught two weeks later, despite wounding a policeman in the course of the arrest. In court, the Judge refused to allow him to read his written defence, so he posted it to Révolte: "Theft exists only through the exploitation of man by man, that is to say in the existence of all those who parasitically live off the productive class...when Society refuses you the right to exist, you must take it...the policeman arrested me in the name of the Law, I struck him in the name of Liberty". The death sentence was later commuted to hard labour for life on Devil's Island, French Guiana.[1]

If Duval worked alone, the next anarchist burglars of note were leaders of gangs which got successively larger until the veritable federation of burglars organized by Marius Jacob. Vittorio Pini, an anarchist shoemaker on the run from the Italian authorities, began a series of burglaries with four other comrades in and around Paris that netted over half a million francs. They stole almost exclusively to support hard-up comrades or prisoners and to subsidize the anarchist press in France and Italy.

Ortiz ostensibly dropped out of anarchist politics in order to begin a career as a professional burglar, with a gang of ten others. He too donated funds to the cause, but not as strictly as Pini had done. He and his men were the only ones convicted at the notorious 'Trial of the Thirty' in 1894; the nineteen anarchist propagandists went free.

Alexandre Marius Jacob was really in a class of his own. At thirteen he was working on a pirate ship in the Indian Ocean. At sixteen he was a known anarchist in prison for manufacturing explosives. At seventeen he pulled off a remarkable theft from a jewellers by posing as a policeman. And by the age of twenty he was successfully burgling churches, aristocratic residences and bourgeois mansions all along the south coast of France. In 1900, aged twenty-one, he escaped from prison after feigning madness, and went into hiding in Sète. Here, he concluded that his previous criminal efforts had been amateur, and decided to set up a properly organized anarchist gang to finance both the movement and themselves; they adopted the name of 'Les Travailleurs de la Nuit' (The Night Workers).

Uniforms were acquired for the purpose of disguise, and research done into safe-breaking techniques, in order that the correct special tools and equipment be obtained. A list of potential targets was drawn up from 'Who's Who'-type books which gave the names and addresses of the rich. Then they set to work. They had no particular base, their field of operations being France itself; some of their more lucrative burglaries were the cathedral at Tours, an Admiral's mansion in Cherbourg, a Judge's house at Le Mans and a jewellery factory in rue Quincampoix, Paris. Jacob checked out the cathedral of Notre Dame and the home of the Bayeaux Tapestry, but decided to cross them off his list. He left notes signed 'Attila' condemning owners for their excessive wealth, and occasionally set fire to mansions that he'd burgled. As the group expanded from its original dozen members, some comrades went off to form autonomous gangs, so that a sort of federation was set up involving anything up to a hundred members, but the composition became less and less anarchist.

Jacob escaped arrest in Orleans by shooting a policeman, but they caught up with him again at Abbéville. He was taken into custody after a brief shoot-out which left one policeman dead and another wounded. Under pressure, one man informed on the whole gang, in such detail that investigations took two years to complete, and the charges ran to a hundred and sixty-one pages. At the Assizes of Amiens in 1905, he was accused of no less than a hundred and fifty-six burglaries; outside, an infantry battalion surrounded the court, and some jurors, afraid of anarchist reprisals, didn't turn up. He was sentenced to forced labour for life and packed off to Devil's Island, where the Governor labelled him as the most dangerous prisoner ever.[2]

All these leading anarchist burglars donated sums to the cause and defended their actions by saying that they had a 'right' to steal; it was a question not of gain or profit, but of principle. The 'natural right' to a free existence was denied to workers through the bourgeoisie's monopoly ownership of the means of production; as the· workers continued to create wealth, so the bourgeoisie continued to appropriate this wealth, a state of affairs maintained ultimately only by force, but legitimized. It was the immoral bourgeois who was the real thief, both in history and in the present; the anarchist 're-appropriation' was 'superior in morality', it was part of a rightful restitution of wealth robbed from the working class, done with moral conviction and good intent to further 'The Cause'. As La Révolte commented: "Pini never conducted himself as a professional thief. He was a man of very few needs, living simply, poorly even, with austerity; that Pini stole for propaganda purposes has been denied by no-one".

Anarchist arguments in favour of la reprise individuelle had a long history. L'Action Révolutionnaire asked its readers to steal from pawn shops, bureaux de change and post offices, and from bankers, lawyers, Jews (!) and rentiers[3] in order to finance the paper. Ça Ira suggested that its readers set an example by applying themselves immediately to relieving the rich of their fortunes. Le Libertaire thought that the thief, the crook and the counterfeiter, in permanent revolt against the established order of things, "were the only ones conscious of their social role". In 1905, a contemporary wrote of Père Peinard, the most scurrilous of the anarchist papers, with the widest working class readership:

"With no display of philosophy (which is not to say that it had none) it played openly upon the appetites, prejudices, and rancours of the proletariat. Without reserve or disguise, it incited to theft, counterfeiting, the repudiation of taxes and rents, killing and arson. It counselled the immediate assassination of deputies, senators, judges, priests and army officers. It advised unemployed working men to take food for themselves and their families wherever it was to be found, to help themselves to shoes at the shoe shop when the spring rains wet their feet, and to overcoats at the clothier's when the winter winds nipped them. It urged employed working men to put their tyrannical employers out of the way, and to appropriate their factories; farm labourers and vineyard workers to take possession of the farms and vineyards, and turn the landlords and vineyard owners into fertilizing phosphates; miners to seize the mines and to offer picks to shareholders in case they showed a willingness to work like their brother men, otherwise to dump them into the disused shafts; conscripts to emigrate rather than perform their military service, and soldiers to desert or shoot their officers. It glorified poachers and other deliberate breakers of the law. It recounted the exploits of olden-time brigands and outlaws, and exhorted contemporaries to follow their example."

Alongside this shining example of proletarian propaganda came the more 'intellectual' approach of the anarchist theoretician. Elisée Reclus put 'forward the logical argument for the reprise individuelle:

"The community of workers, have they the right to take back all the products of their labour? Yes, a thousand times yes. This re-appropriation is the revolution, without which everything still is to be done.

A group of workers, have they the right to a partial re-appropriation of the collective produce? Without a doubt. When the revolution can't be made in its entirety, it must be made at least to the best of its ability.

The isolated individual, has he a right to a personal re-appropriation of his part of the collective property? How can it be doubted? The collective property being appropriated by a few, why shouldn't it be taken back in detail, when it can't be taken back as a whole? He has the absolute right to take it—to steal, as it's said in the vernacular. It would be well in this regard that the new morality show itself, that it enter into the spirit and habit."

Men of 'high principle and exemplary life' such as Elisée Reclus and Sébastien Faure were so carried away by their convictions on the immorality of property, that they were ready to condone virtually any kind of theft on purely theoretical grounds, but the abstract theoretical arguments put forward by these intellectuals were unconnected to their own daily practice.

Nevertheless, in the Trial of the Thirty in 1894, Faure, Grave, Pouget and Paul Reclus and others were charged jointly with the Ortiz gang with criminal conspiracy. The propagandists went free and the burglars went to jail, but for Jean Grave at least, it was a salutary experience and he determined henceforth to play no part in propounding theories of the validity of theft. The paper that he launched the following year called Temps Nouveaux was soberly written and gained a wide audience in 'fashionable' circles sympathetic to anarchism. Grave saw in crime a corruption that would make people unsuited for the high ideals of a free society. He objected in particular to the type of professional crook who, rather than being a threat to the system, was the mirror-image of the policeman, recognizing the same social conventions, with similar minds and instincts, respectful of authority. But, “if the act of stealing is to assume a character of revindication or of protest against the defective organization of Society, it must be performed openly, without any subterfuge”. Grave anticipated the rather obvious objection:

"'But', retort the defenders of theft, 'the individual who acts openly will deprive himself thus of the possibility of continuing. He will lose thereby his liberty, since he will at once be arrested, tried and condemned'.

Granted, but if the individual who steals in the name of the right to revolt resorts to ruse, he does nothing more nor less than the first thief that comes along, who steals to live without embarrassing himself with' theories."

In fact, a new generation of anarchists, spurred on by the 'individualist' ideas of Max Stirner, were to take as their point of departure exactly what Jean Grave objected to, that the rebel who secretly stole was no more than an ordinary thief. The developing theory of 'illegalism' had no moral basis, recognizing only the reality of 'might' in place of a theory of 'right'. Illegal acts were to be done simply to satisfy one's desires, not for the greater glory of some external 'ideal'. The illegalists were to make a theory of theft without the embarrassment of theoretical justifications.

Saint Max

With the dawn of the twentieth century a new current arose within French anarchism: self-conscious anarchist-individualism. The main intellectual base for this new departure was the rediscovery of the works of the much maligned and neglected philosopher, Max Stirner. Karl Marx himself had not underestimated the radical nature of Stirner's challenge, and in The German Ideology, directed a most vicious polemic against him and his affirmation of 'egoism'. But Stirner's book, The Ego and Its Own, although causing a great stir at the time, was soon forgotten. In France interest was only reawakened around the turn of the century due to a conjunction of two main factors: the current fad for all things German (rather ironic considering the relative proximity of the First World War), and the keen interest in individualist philosophy amongst artists, intellectuals and the well-read, urban middle classes in general.

One indigenous bourgeois individualist was Maurice Barrès, who wrote an acclaimed trilogy entitled Le Culte de Moi, in which, having observed that, "our malaise comes from our living in a social order inspired by the dead", depicted a new type of man who, in satisfying his ego, would help turn humanity into "a beautiful forest". Despite such apparent sentimentality, his individualism was based upon the privileged material position of the bourgeoisie, whose self-realization was only made possible by the subjugation of the desires of the masses. Barrès ended up in later years as an anti-semitic, Christian nationalist.

Individualism gained more radical currency through Henrik Ibsen, the Norwegian writer, who produced critiques of contemporary morality in dramatic form. He developed the theme of the strong individual standing alone against both the tyranny of the State, and the narrow-minded oppressive moralism of the masses. Ibsen's appeal lay in the fact that personal longing for independence existed at all levels of society, so anybody, regardless of their class origin, could identify with the individual who was opposed to the mass. But Ibsen's individualism addressed moral questions rather than economic ones.

In the fad for all things German, Friedrich Nietzsche was the most fashionable of the writers-cum-philosophers. He railed against the prevailing culture and ethos of his time, and especially against attitudes of conformity, resignation or resentment; he willed the creation of the 'Superman', who would break through the constraints of bourgeois morality and the artificiality of social conventions towards a rediscovered humanity of more primitive virtues. For the record, he was neither a nationalist nor an anti-semite. Nietzsche regarded Stirner as one of the unrecognized seminal minds of the nineteenth century, a recommendation which, coupled with the aforementioned vogue for German philosophy, resulted in fin de siècle publication of extracts of his work in Le Mercure, and in the symbolists' 'organ of literary anarchism', Entretiens politiques et litteraires.[4] In 1900, the year of Nietzsche's death, the libertarian publisher, Stock, printed the first complete French translation of Stirner-'s work, entitled L'Unique et sa Propriete.

Young anarchists, in particular, quickly developed a fascination for the book, and it rapidly became the 'Bible' of anarcho-individualism. Stirner's polemic was much more extreme than the well-worn ideas that had until then made up the stuff of revolutionary ideology. Anarchist thinkers had tended, like Proudhon, to conceive of some absolute moral criterion to which people must subordinate their desires, in the name of 'Reason' or 'Justice'; or, like Kropotkin, they had assumed some innate urge which, once Authority was overthrown, would induce people to cooperate naturally in a society governed by invisible laws of mutual aid. The 'anarchism' of Tolstoy and Godwin was also thoroughly grounded in moralism, a throw-back to their Christian backgrounds of, respectively, Russian Orthodoxy and English Dissent. Even anarcho-syndicalists such as Jean Grave had a 'revolutionary morality' which viewed the class struggle as a 'Just War'.

Stirner saw all 'morality' as an ideological justification for the repression of individuals; he opposed those revolutionaries who wished to set up a new morality in place of the old, as this 'would still result in the triumph of the collectivity over the individual and lay the basis for another despotic State. He denied that there was any real existence in concepts such as 'Natural Law', 'Common Humanity', 'Reason', 'Justice' or 'The People'; more than being simply absurd platitudes (which he derisively labelled 'sacred concepts'), they were some of a whole gamut of abstract ideas which unfortunately dominated the thinking of most individuals: "Every higher essence, such as 'Truth', 'Mankind' and so on, is an essence OVER us". Stirner perceived the repressive nature of ideologies, even so-called 'revolutionary' ones; he believed that all these 'sacred concepts' manufactured by the intellect actually resulted in practical despotism.

For Stirner the real force of life resided in the will of each individual, and this 'Ego', "the unbridled I", could not come to real self-fulfillment and self-realization so long as the State continued to exist. Each individual was unique, with a uniqueness that should be cultivated: the Egoist's own needs and desires provided the sole rule of conduct. Differences with other individuals were to be recognized and accepted, and conscious egoists could combine with others into "unions of egoists", free to unite or separate as they pleased, rather than being held together in a Party under the weight of some ideological discipline. Certain conflicts of the will might have to be settled by force, as they were already in present society, but these should be done without the need for moral justification.

Stirner saw desire as the prime motivating force of the will: "My intercourse with the world consists in my enjoying it...my satisfaction decides about my relation to men, and I do not renounce, from an excess of humility, even the power over life and death…I no longer humble myself before any power". The realization of individual desires was to be the basis for the elimination of the State, for what was the State ultimately but the alienated power of the mass of individuals? If people re-appropriated their power, habitually surrendered to the State, then established society would start to disintegrate.

In the struggle against the State, which every conscious egoist would be forced to engage in, Stirner distinguished between a 'Revolution', which aimed at setting up an immutable new social order, and 'rebellion' or insurrection, a continuous state of permanent revolution, which set "no glittering hopes on 'institutions"'. Stirner's rebellion was not so much a political or social act, but an egoistic one.

Furthermore, in this battle with the State, Stirner felt that, "an ego who is his own cannot desist from being a criminal", but this did not mean that a moral justification for crime, was necessary. Discussing Proudhon's famous dictum "Property is theft", he asks why, "put the fault on others as if they were robbing us, while we ourselves do bear the fault in leaving the others unrobbed? The poor are to blame for there being rich men...". He suggested that Proudhon should have phrased himself as follows: "There are some things that only belong to a few, and to which we others will from now on lay claim or siege. Let us take them, for one only comes into property by taking, and the property of which for the present we are still deprived came to the proprietors likewise only by taking. It can be utilized better if it is in the hands of us all than if the few control. Let us therefore associate ourselves for the purpose of this robbery". He summed up: "To what property am I entitled? To every property to which I empower myself...I do not demand any 'Right', therefore I need not recognize any either. What I can get by force, I get by force, and what I can not get by force I have no right to, nor do I give myself airs or consolations with my imprescriptable 'Right'...Liberty belongs to him who takes it".

Stirner proposed 'expropriation' not as the 'legitimate' response of a victim of society, but as a way of self-realization: "Pauperism can be removed only when I as an ego realize value from myself, when I give my own self value, and make my price myself. I must rise in revolt to rise in this world". Yet he seemed unsure as to whether a rebellious crime should be glorified or superseded: "In crime the egoist has hitherto asserted himself and mocked the sacred; the break with the sacred, or rather of the sacred may become general. A revolution never returns, but a mighty, reckless, shameless, conscienceless, proud CRIME, does it not rumble in distant thunder, and do you not see how the sky grows presciently silent and gloomy?". Elsewhere, in his less poetic moments, Stirner was more pensive: "Talk with the so-called criminal as with an egoist, and he will be ashamed, not that he transgressed against your laws, but that he considered your laws worth evading, your goods worth desiring; he will be ashamed that he did not despise you and yours altogether, that he was too little an egoist". These seemingly contradictory attitudes were later to be keenly felt by some of the illegalists.

The Ego and Its Own was a startling work, written from a point of view that might be called 'radical subjectivity', a work of an all-consuming passion best summed up in the egoist's battlecry: "Take hold and take what you require! With this the war of all against all is declared. I alone decide what I will have!".

If socialists continually ignored the question of individual desires and the subjective element of revolt, then it must be said that Stirner made little effort to direct his attention to basic socio-economic questions and the need for a collective struggle of the dispossessed, which would realize each individual's desires. He saw 'the masses' as "full of police sentiments through and through", and reduced the social question of how to eliminate the State and class society, to an individual one to be resolved by any means. Still, he had at last made it possible for rebels to admit that their revolt was being made primarily for their own self-realization: there was no need to justify it with reference to an abstract idea. Those who claimed to be acting in the name of 'The People' were often sentimental butchers. Stirner stripped away the dead weight of ideology and located the revolution where it always had been — in the hearts and minds of individuals.

The force and vigour of Stirner's ideas appealed to many anarchistic spirits determined to live the revolution there and then. The long association of French anarchism with theoretical voluntarism and practical illegality, sympathy for working class criminality, and hostility to bourgeois morals and socialist politics, meant that Stirner's ideas were easily accessible to many anarchists not yet blinded by an ideologically 'pure' anarchism. In contrast to the latter, the new generation of anarchists felt it necessary to call themselves 'anarchist-individualists', although they saw themselves as upholding the banner of anarchism pure and simple.

This milieu, which emerged after 1900, and which was largely Libertad's creation, was one that had already assimilated Stirner's basic ideas into the body of its theory by the time of the Bonnot Gang. It is quite possible that none of the gang had ever actually read The Ego and Its Own, but their actions and Stirner's theories were to have striking similarities.

2. A new beginning

“Do with it what you will and can, that is your affair and does not trouble me. You will perhaps have only trouble, combat and death from it, very few will draw joy from it.”

Max Stirner (1806-56)

on his book The Ego and Its Own

Libertad

AROUND THE TURN of the century, anarchist-individualist propaganda was centred on Sébastien Faure's weekly journal Le Libertaire — still in existence today as the organ of the 'Fédération Anarchiste'. This gave space to individualist ideas and was critical of syndicalism. One anarchist who worked for the paper was Albert Joseph, habitually known as 'Libertad', who founded the milieu within which illegalism was to flourish.

Libertad was brought up in an orphan school, the abandoned son of a local Prefect and an unknown woman, and went to secondary school in Bordeaux. A job was found for him, but he was soon dismissed and sent back to the Childrens' Home from which he absconded and took to the road as a trimardeur or tramp. This probably brought him his first contact with anarchists, as tramps often lodged at anarchist-run labour exchanges — the Bourses du Travail, where they might be given popular revolutionary songsheets to sell on their travels at two centimes apiece. Some tramps would have been unemployed workers on the viaticum (that is, given journey money and supplied with coupons for free meals and lodging in the hope that they would find work). Many of them would have been workers sacked for syndicalist or revolutionary opinions. Some tramps lived parasitically off the Bourses du Travail, while others were more devoted to spreading anarchist propaganda on their travels around France and neighbouring countries such as Switzerland and Belgium. Many had decided to refuse regular waged work (or had it refused for them) and lived hand-to-mouth, doing part-time work, selling cheap trinkets at local markets and doing the odd bit of thieving.

Libertad made his way north from Bordeaux and arrived in Paris in 1897 at the age of twenty-two. Marked down for his anarchist opinions, he had already been under surveillance for three years — over the next ten his police record was to accumulate paper to a thickness of three inches.

In the capital he stayed on the premises of Le Libertaire and worked on the paper for several years alongside Charles Malato and, occasionally, the syndicalists Pelloutier and Delesalle; he also collaborated on the pro-Dreyfusard daily Le Journal du Peuple launched by Sébastien Faure and Emile Pouget. He was not yet of the individualist persuasion, although it was probably here that he encountered individualist ideas.

In 1900 Libertad found work with a regular publishing company as a proofreader (still a favourite job among Parisian anarchists, due to the high pay and flexible hours) and stayed there until 1905, joining the Union. In the same year, after speaking at a public meeting in Nanterre just outside Paris, he met Paraf-Javal and in October of 1902 they set up the Causeries Populaires at 22 rue du Chevalier de la Barre in Montmartre, just behind the Sacré Coeur. The location was somewhat appropriate, as this street was the old rue des Rosiers where two generals had been shot by Communards in 1871. The Sacré Coeur itself had been built, quite deliberately, on the site of the old artillery park where the insurrection had begun; MacMahon, the Marshal in charge of the repression, had specifically ordered its construction, "in expiation for the crimes of the Commune". The basilica was still incomplete, however, when the Causeries Populaires were founded.

The church was meant to stand evermore as a psychological and material expression of the victory of the bourgeoisie. Dominating Paris, atop the working class neighbourhood of Montmartre, it was seen even by the esteemed novelist Emile Zola as "a declaration of war" and as a "citadel of the absurd". As a Christian church, it proclaimed the continued reign of suffering, both ideologically and in reality, and demanded resignation to that suffering.

Libertad had already had dealings with the place. Hungry, he had gone to receive Christian charity in the form of food doled out to the poor each evening, but first had to listen to the sermon. After suffering in silence for several minutes he could finally bear it no longer and sprang to his feet to denounce the priest's hypocrisy. A tumultuous scene ensued and Libertad was carted away and sentenced to two months' prison for insulting public morals.

Rapidly he accumulated further convictions — for vagrancy, insulting behaviour and shouting, "Down with the Army!", the latter deemed more serious than disturbing the Pax Dei, as he received three months in prison.

Now in his late twenties, bearded but already balding, Libertad began a dynamic proselytization in Montmartre that was an extraordinarily powerful affirmation of anarchist individualism. Crippled in one leg, he carried two walking sticks (which he wielded very skilfully in fights) and habitually wore sandals and a large loose-fitting typographer's black shirt. One comrade said of him that he was a one-man demonstration, a latent riot; he was quickly a popular figure throughout Paris. His style of propaganda was summed up by Victor Serge as follows: "Don't wait for the revolution. Those who promise revolution are frauds just like the others. Make your own revolution by being free men and living in comradeship". His absolute commandment and rule of life was, "Let the old world go to blazes!". He had children to whom he refused to give state registration. "The State? Don't know it. The name? I don't give a damn, they'll pick one that suits them. The law? To the devil with it!" He sung the praises of anarchy as a liberating force, which people could find inside themselves.

Every Monday evening a causerie or discussion took place in the best room of the rue du Chevalier de la Barre. It was a gloomy ground-floor room decorated in the 'modern style' with flower-patterned wallpaper; comrades would sit on the old decrepit benches or chairs pilfered from the local squares and bistros, the speaker (if there was one) would lean against an old rickety table while others would be flicking through the books and pamphlets piled up on a counter at the back of the room.[5]

By 1904, the causeries were proving successful enough in the working class quarters of the XVIIIth, XIVth and XIth arrondissements, in Courbevoie and the Quartier Latin, to enable a bookshop to be opened in the rue Dumeril and an annexe in the rue d'Angouleme in the XIth arrondissement.

Libertad's erstwhile cooperation with the syndicalist militants was now coming to an end. In 1903 he and Paraf-Javal had formed the Antimilitarist League in association with some leading syndicalists, but this alliance fell apart during the Amsterdam Congress of the International Antimilitarist Association (AIA) in June 1904. Libertad and Paraf-Javal saw desertion or draft-dodging as the best antimilitarist strategy, believing that if anarchists stayed in the army awaiting a revolutionary situation, they would very quickly all end up in military prisons or the African disciplinary battalions. The Congress, however, saw such a strategy as too individualistic, preferring soldiers to remain disaffected within their units so as to make the army as a whole less reliable. Despite the mutiny of the 17th Line Regiment in 1907 (when the Government rather stupidly sent local troops in to suppress the revolt by vineyard workers who were no more than their own kith and kin) the individualist strategy was probably more realistic, especially given the figures for the number of men rotting in the African hard labour prisons.

As a result, Libertad and Paraf-Javal left the Antimilitarist League and stepped up anti-syndicalist propaganda. A whole series of articles appeared that year in Le Libertaire against participation in elections, unions and cooperatives: all participation in power structures, even 'alternative' ones, was seen to reinforce the hierarchical system of power as a whole.

Paraf-Javal put forward the individualist argument in an article entitled 'What is a Union?', and answered his question as follows: "It is a grouping whereby the downtrodden masses class themselves by trade in order to try and make the relations between the bosses and workers less intolerable. From the two propositions, one conclusion: where they don't succeed, then the union's task is useless, and where they do then the union's work is harmful, because a group of men will have made their situation less intolerable and will consequently have made present society more durable". Further pamphlets rolled off the presses: What I mean by Anarchic Individualism, Anarchist Individualism in Practice, pamphlets on Max Stirner, and Hans Ryner's Little Individualist Handbook. Libertad, however, was less a writer than an orator, preferring to intervene verbally.

In January 1905 the veteran Communard, Louise Michel, died in Marseille, and the AIA called a meeting in Paris to organize a spectacular 'revolutionary' funeral. Libertad went along, but his attitude clashed with that of the militants. He told them that the whole ceremony was ridiculous, just as ridiculous as calling a woman well into her seventies 'the Red Virgin' — "She lost her virginity long ago", he proclaimed. The crowd became hostile and he withdrew, muttering, "You're all idiots". The funeral went ahead as planned, with tens of thousands lining the route and in the procession. The city was swamped with police and regular army units, and many bourgeois apparently fled fearing that revolution was imminent; some Catholics even locked themselves in their churches ready to defend themselves against the crowd. Despite police provocations, including the banning of songs and unauthorized flags, there were very few 'incidents'; by contrast, in Russia, the same day was to go down in history as 'Bloody Sunday' — the start of the 1905 Revolution.

The Causeries Populaires now had a regular audience, but it was still of minimal size, and the only hope of reaching a wider public lay in publishing a regular paper that could continue in print the discussions of the ideas of Stirner, Nietzsche, Bakunin, Georges Sorel (the theorist of revolutionary syndicalism) and others, as well as arguing for a new revolutionary practice based on the self-realization of the individual.

Libertad and his two lovers, the schoolteacher sisters Anna and Amandine Mahé, and Paraf-Javal, now put their combined energies into founding an anarchist-individualist weekly, so they wouldn't have to rely on Le Libertaire to voice their opinions. The first issue of l'anarchie appeared on 13th April 1905, and continued to appear every Thursday, without interruption, until it was suppressed with all the other revolutionary papers at the outbreak of war in 1914. Its title harked back to the first paper ever to adopt the anarchist label: Anselm Bellegarrigue's L'Anarchie: journal d'Ordre, of which only two issue's were produced (in 1850). His slogan had been, "I deny everything, I affirm only myself'. Libertad ended his first article with the battle-cry, "Resignation is death. Revolt is life".

There was a print run of 4000, although perhaps only half that number were sold (at ten centimes a copy, like the other anarchist papers); readership figures are unknown. Financially it was maintained by voluntary donations to supplement the small income from street and bookshop sales; it probably also benefited from the occasional reprise individuelle — thefts carried out by comrades. The main contributors besides Libertad, Paraf-Javal and the Mahé sisters were René Hemme (aka 'Mauricius' or 'Vandamme'), André Roulot (aka 'Lorulot'), Juin-Lucien Ernest (aka 'Armand'), and Jeanne Morand (one of another pair of sisters with whom Libertad had intimate relations). Anna Mahé was the nominal manageress of the paper.

L'anarchie declared itself against resignation and conformity to the existing state of affairs, and particularly opposed vices, habits and prejudices such as work, marriage, military service, voting, smoking tobacco, drinking alcohol and the eating of meat. It exalted l'endehors, the outsider, and the hors-la-loi, outlaws. According to Lorulot its purpose was to work sincerely for 'individual regeneration' and the 'revolution of the self. L'anarchie's view of society was essentially as follows: firstly there were not two opposed classes, bourgeois and proletarian, but only individuals (although there were those who were for, and those who were against, society as it was presently constituted). The Master and the Slave were equally part of the system and mutually dependent, but the Rebel or Révolté could come originally from either category: their propaganda was addressed to anybody prepared to rise in revolt against existing society.

The syndicats or unions were seen simply as capitalist organizations which defended workers as workers; thus keeping them in a social role which it should have been the anarchist aim to destroy. To invest them with value only so long as they were workers had nothing to do with their own realization as individuals. The syndicalists were seen as unwitting tools of capitalism, whose practical reformism was only kept going by the myth of 'The Revolution', an ideology which furnished the unions with militants for their present-day battles. Only Georges Sorel had been shrewd enough to accept that the idea of 'The Revolution' was indeed a myth. But not only was such a myth necessary, it was in fact the whole essence of socialism, without which the struggle for the working class might collapse into despair. For Sorel, the present-day struggle was everything, and in this he had something in common with the politics of l'anarchie, though he was a believer in the mass rather than in the individual.

Sorel's realism was seen by the anarchist-individualists as further evidence of the bankruptcy of syndicalism; especially nauseating to them was the dry academic moralizing of Jean Grave, the 'Anarchist Pope', in Temps Nouveaux, while the Mayday celebrations were regarded contemptuously, as nothing more than theatrical role-playing, mirroring the absurdity of the bourgeoisie's 14th of July (Bastille Day): it changed nothing.

The individualists' ideal was to live their lives as neither exploiter nor exploited — but how to do that in a society divided in this way? Their answer was for people to take direct action through the reprise individuelle, or in slang, la reprise au tas — taking back the whole heap.

A good part of 1906 was spent campaigning against the elections. Previously Libertad had stood as the 'abstentionist' candidate in the XIth arrondissement, but this time they relied on 'interventions', posters and the paper. At one large socialist gathering in Nanterre the Socialist Deputy (MP) was almost thrown out of the window: many of the interventions by the anarchists ended up in fighting.

However, trouble was also brewing internally: Libertad and Paraf-Javal had argued, and the latter had taken control of the bookshop in rue Duméril, setting up a ' Scientific Studies Group' which announced itself for a 'reasoned social organization obtained by scientific camaraderie, methodically and logically obtained outside all coercion'. What this actually meant was not quite clear, except that Paraf-Javal was obsessed with science and logic, synonymous as they were in those times with the idea of 'Progress'. In February 1907 a police report noted that the two groups had fallen out and foresaw trouble in the future; the police were not to be disappointed.

For the time being, however, there was only trouble with the authorities. On Mayday Libertad, Jeanne Morand and another comrade called Millet were arrested for evading fares on the Metro and assaulting a ticket collector and a policeman; Millet was also charged with carrying a knuckleduster. Libertad spent a month in prison, but within two weeks of his release there was more serious trouble when it was decided to hold a Sunday evening causerie en plein air. It was a warm summer night and soon a reported two hundred people had gathered in the rue de la Barre on the heights of Montmartre. Some local traders complained about the noise and obstruction, and the police ordered the crowd to disperse. The anarchists refused and when police reinforcements were called, a pitched battle ensued leaving several wounded. The street was left littered with broken chairs, bottles and the usual strange debris of a crowd suddenly dispersed.

After that affair things seem to have remained comparatively quiet for the next year, until the summer season of interventions got under way. Syndicalist meetings were often the target this time, and the anarchist-individualists were definitely persona non grata. On one occasion, Libertad asked for the right to speak, but was refused and told that his group was not welcome. Fights broke out with the stewards and lasted for half an hour, until finally Libertad's group stormed onto the platform and sent the syndicalists fleeing; the meeting broke up in disorder without Libertad being heard.

The conflict between Paraf-Javal's group of 'scientists' and the Causeries Populaires comrades now came to a head. Paraf-Javal was already angry that his pamphlets were being sold at causeries and were not being paid for, when one of Libertad's group, Henri Martin (alias 'Japonet'), Amandine Mahé's new lover, stole some money from the bookstall at a meeting of the 'Scientific Studies Group'. At a subsequent meeting a brawl ensued between partisans of the two groups in which knives, knuckledusters and spiked wristbands were used. After this incident Paraf-Javal would only go out armed with a revolver and a dagger, but he preferred to stay at home writing a diatribe against Libertad's group. The pamphlet Evolution of a group under a bad influence was greeted with anger and derision by anarchists everywhere, and effectively isolated his small clique. At the rue de la Barre, however, Libertad was also on his own, having fallen out with both the Mahé sisters, Jeanne Morand and Henri Martin. The DeBlasius brothers, who ran the print shop, had also had enough of the rue de la Barre, and at the instigation of Paraf-Javal they departed with some of the printing material and most of the pamphlets.

Just over two weeks later, on 29th September 1908, a detective of the Third Brigade included in his report the following: "...a few days ago there was a fight between a well-known comrade, 'Bernard', and Libertad inside the Causeries Populaires in the rue de la Barre. Libertad gave Bernard a serious blow to the head, and, covered in blood, the latter ran out towards rue Ramey. During the fight, one of the Mahé sisters kicked Libertad in the stomach to try and put a stop to it". A week later he was taken seriously ill to the nearby hospital of Lariboisière, and eventually died in the early hours of the morning of 12th November. There were rumours that he had died at the hands of the police on the steps of Montmartre, or that his death was due to 'natural causes', but it seems (and this is substantiated by a later editor of l'anarchie) that the true cause was that kick in the stomach by his one-time lover.

He had fallen out with his erstwhile comrades to such an extent that they refused to view the body or claim it for burial. After the statutory seventy-two hours it was taken to the Ecole de Clamart medical school to be used in the furtherance of scientific research.

City of thieves

By the end of 1908, l'anarchie was becoming the only anarchist paper which positively promoted crime, and the theory of 'illegalism'. This theory differed from the reprise individuelle, not just due to its connection with the anarchist-individualist current, but because the illegalists stole not simply for the greater advancement of 'the cause', but for their own advancement, according to Stirner's line of argument. Or at least so they said: in practice, successful illegalism probably helped support the weekly paper and comrades who were in dire financial need. Yet there was not necessarily a contradiction here, for, as part of the movement, their own self-realization was reflected in the self-realization of other comrades: an egoistic gesture in revolutionary terms should also be an altruistic one.

Lorulot had already encouraged illegality because it involved "minimal risks and satisfactory returns", while Armand suggested that it was unimportant whether a comrade earned his living legally or illegally, but important that he live to his own profit and advantage. Illegalism was viewed favourably by many individualists in the Causeries Populaires milieu, not least because they engaged in petty-crime, or benefited from the crimes of others, like much of the populace of working class Montmartre. As Victor Serge later recalled: "One of the peculiar features of working class Paris at this time was that it bordered extensively on the underworld, that is on the vast world of fly-by-nights, outcasts, paupers and criminals. There were few essential differences between the young worker or artisan from the old central districts and the ponce from the alleys around Les Halles. A chauffeur or mechanic with any wits about him would pilfer all he could from the boss as a matter of course, out of class-consciousness...".

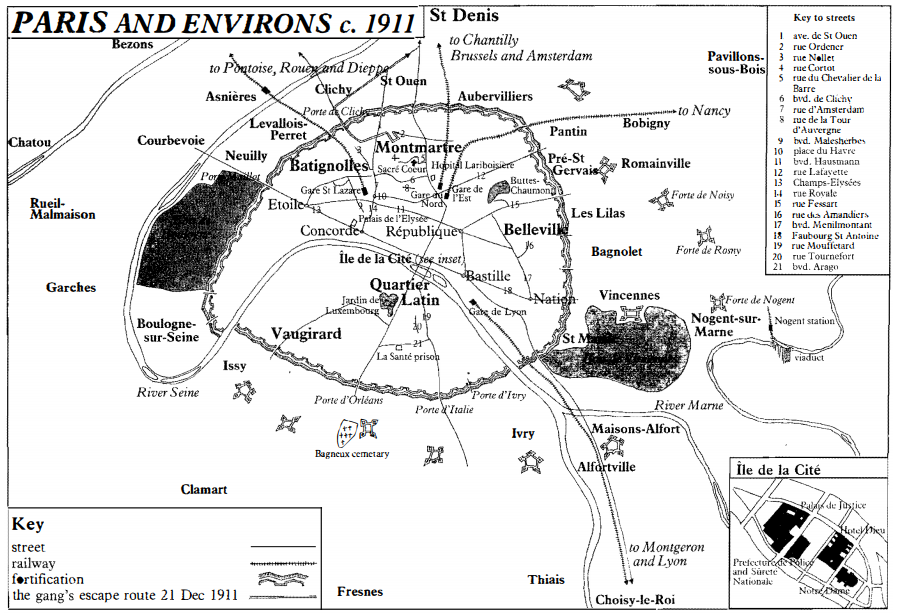

In fact there were neighbourhoods in Paris more or less recognized as 'criminal', with their own traditions and way of life — principally the northern outskirts of the city; Pantin, St-Ouen, Aubervilliers and Clichy. A large number of Parisian criminals made their living from the thousands of tourists who, in the wake of the Great Exhibition of 1900, flocked to see the glittering capital of European civilization. There were plenty of professional beggars and pickpockets, as well as thousands of part-time prostitutes on the boulevards and in the brasseries — working class women forced to service 'gentlemen' in order to make ends meet. There were also professional loan sharks, confidence tricksters, forgers, counterfeiters, and even some specializing in dog or bicycle theft.

Parisian workers, if not part of this 'underworld', were usually sympathetic to it and naturally hostile to the police, and not averse to a bit of thieving themselves; the public in general had an almost ambivalent attitude to crime.

The anarchist viewpoint that was sympathetic to crime was probably received more favourably by working class people than Jean Grave's moral sermonizing that all crime was essentially bourgeois. One of the most popular working class heroes of the time was the anarchist Ravachol, who had declared that, "To die of hunger is cowardly and degrading. I preferred to turn thief, counterfeiter, murderer...". If working class people were sympathetic to such a figure it was because they understood where he was coming from.

The hostility of employers to workers who expressed unsound opinions, or who were denounced to them by the police as 'anarchists' or 'troublemakers', meant that many hundreds of workers found it extremely difficult to find work, and were virtually forced into criminality. Under Capitalism, where a worker's only power is his or her labour power, which must be sold in order to survive, what can someone do when the employers refuse to buy, consequently denying the right to live? The illegalists answered this question through a reversal of perspective: through the physical power that is all a worker possesses, the means of survival have to be seized directly, without exchange, and, if necessary, by force.

The cross-over in Paris between the working class, the underworld and revolutionary politics, was a similar sort of phenomenon to the situation in Czarist Russia, but there, politics was much more firmly rooted in illegality. Paris, long a haven for Russian refugees, sheltered upwards of twenty-five thousand exiles, of whom the police estimated that no less than fifteen hundred were 'terrorists' and five hundred and fifty of them anarchists or maximalists. The French Intelligence services tried to keep a close watch on the latter category, especially in their plans for 'expropriations' and also because they had links with French revolutionaries and Indian nationalists, whom they aided in the study and manufacture of pyrotechnics. The Social-Revolutionary 'Maximalists' were well known for their advocacy of a wider application of 'terrorism' including the incendiarism and pillage of estates, as well as individual assassinations. They also carried out expropriations at home and abroad: one, discussed in rue St Jacques by Divinogorsky and a comrade, was planned for a branch of the Crédit Lyonnais in Paris, but was rejected in favour of an attack on a bank in Montreux in Switzerland. In this bungled operation in 1907 four people were killed and both revolutionaries arrested.

A more spectacular action took place in the same year, carried out by members of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party. Led by Semyonovich Ter-Petrossian, an attack on the State Bank in Tbilisi (Georgia) netted three hundred and forty thousand kopeks, but it was mainly in large-denomination bills, and revolutionaries were caught in Paris trying to exchange them. Also around this time, members of the Polish Socialist Party, led by Pilsudski, were conducting raids on tax offices, ambushing Treasury vans, and assassinating Governors and policemen. The experience, often violent and clandestine, of the Russian revolutionaries was communicated by refugees to those western revolutionaries who were most sympathetic to both ideas and action — the anarchists above all.

But if the Bolsheviks, for instance, engaged in expropriations, this was far from illegalism; such expropriations were done for 'the Cause' (in this case the Party) and the comrades responsible only received fifty kopeks a day to live on. Bolshevik illegality was simply a necessary tactic at the time for building the Party.

Nevertheless, the effect of armed expropriations, assassinations (the head of the Russian Secret Service, the Okhrana, was executed in a Paris hotel room in 1908) and bomb explosions (usually accidental, as in the Bois de Vincennes in 1906 and the Bois de Boulogne in 1908) provided anarchists with inspiration, and something to admire and sympathize with. Above all, the Russian Revolution of 1905 sent revolutionaries into a state of great excitement, and the syndicalist leaders in particular determined to face up to their responsibilities as the vanguard of the working class.

State of emergency

By 1906 the Republican Bloc had successfully beaten off the challenge to its power of the extreme right-wing, a struggle which had lasted for ten years and which had been crystallized in the Dreyfus affair. Essentially, it was a show-down between the more 'progressive' capitalists who sought to usher France into the era of mass-production, and the backward, pro-monarchical forces of the Catholic church and army, who still harked after the feudal traditionalism of the Ancien Régime. It was a struggle that French Capitalism as a whole could not afford to lose, and, needless to say, clerical militarism was routed, the State took control of mass-education, and the 'Radicals' were at last left free to deal with the working class.

The CGT had largely stayed out of this fight between what they had correctly analyzed as 'rival factions of the bourgeoisie', although many anarchists were prepared to give grudging support to the 'Dreyfusards'. In 1906 the CGT emphasized their independence in the 'Charter of Amiens' which announced their autonomy from the parties of both Right and Left, and called for a general strike on 1st May in demand of an eight-hour working day.

This was the first ever general strike in France, but only two hundred thousand workers responded — a fraction of the industrial workforce, of whom only seven per cent were CGT members. Nevertheless, the 'Radical' Prime Minister Clemenceau (an ex-syndicalist) declared a state of emergency, arrested the CGT leaders, Pouget, Griffeulhes and Yvetot, and proceeded to turn Paris into an armed camp: sixty thousand troops were mobilized to patrol the streets.

Faced with blatant repression by the Government, and a lack of mass support, the strikers returned to work, but over a million days were lost that year, the highest ever. It was the crest of the revolutionary syndicalist wave, although the CGT continued to expand, doubling its membership to six hundred thousand by 1912.

The 'Radical' Bourgeoisie, now dominant in the offices of the State, went on the offensive: not only was industrial action by 'civil servants' outlawed (a category which included teachers and railway and postal workers) but troops were sent in to break virtually every strike, with the result that dozens of workers were killed and hundreds wounded. A bitter strike by miners in the Nord was crushed in 1906. The protracted struggle of the vineyard workers of the Midi was finally overwhelmed in 1907, despite the mutiny of a whole regiment of troops sent in to break the strike. The strike of the Nantes dockers collapsed the same year. In 1908, striking quarry-workers were shot at Draveil and cut down by dragoons at Villeneuve-St Georges; at the same time, electricians plunged Paris into darkness in the hope of winning their dispute, but were forced back to work just like the construction workers. The textile workers were defeated the following year, and an attempted strike by postal workers ended up as a fiasco, with the CGT leadership imprisoned again. Aided by this fortunate absence of the anarchist 'old guard', and pointing to the series of defeats as evidence of bad management, the reformists, led by Léon Jouhaux captured the leadership at the end of the year.

Nevertheless, with the numerical strength of the CGT still growing, the employers attempted to vaccinate their workers against the syndicalist virus by recruiting them to company or Catholic-run unions — the 'Yellow' or 'Green' unions as they were known — or tried to bargain with more receptive union leaders on a local basis. Meanwhile the Government introduced social legislation, in the form of pension laws, which meant. that workers had more to lose if they got the sack. As strikes became shorter in duration, involving fewer workers, strikers increasingly used 'hit-squad' tactics as a way of out-manoeuvring the police and army and directly damaging the employers. But workers' living standards as a whole continued to decline, despite the appearance of abundance given to Paris by the new era of mass-production, and more workers were pushed into 'marginal' and criminal activities in order to survive. Only one other legal resource was left to the working class by the bourgeois State: electoral politics. It was no surprise that as the number of working class defeats multiplied, so the socialist vote steadily increased.

But one group of proletarians, at least, was not prepared simply to resign itself to this dominant atmosphere of defeatism. Instead they invested their struggle with an even greater fury — rather than be exploited they would refuse waged work, rather than be forced into poverty they would steal, rather than vote they would riot, rather than 'make propaganda' in the army they would refuse to do military service altogether, rather than complain about their situation they would take immediate direct action to improve it. These were the sort of attitudes expressed by the new generation of rebels who had responded to the theory and practice of anarchist-individualism. For if Libertad's propaganda had helped create a climate of defiance, it had also reflected a general mood.

3. The rebels

"He who has no means of subsistence, has no duty to acknowledge or respect other people's property, considering that the principles of the social covenant have been violated to his prejudice."

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814)

MANY OF THE principal characters involved with the Bonnot Gang (but not Bonnot himself) spent some time in Belgium in the couple of years prior to 1911, although some of them only became acquainted later, in Paris. Nevertheless, the Belgian experience was a formative one, during which they learned the ground rules of clandestinity and illegality. However, if these rebels served their apprenticeship in Belgium, their practice was to be firmly centred on Paris.

Brussels

Towards the end of August 1909, a nineteen year-old future editor of l'anarchie arrived in the French capital from Brussels. His name was Victor-Napoleon Lvovich Kibalchich, to become better known as Victor Serge, the pro-Bolshevik revolutionary and critic of Stalinism. At this time though he was the fiery young anarchist who wrote for the Brussels anarchist weekly Le Révolté (The Rebel) under the pseudonym Le Rétif — 'the Restless One'.

He had been born in the winter of 1889 into a poor Russian refugee family living in exile in Verviers in Belgium. While still very young he had his first major initiation into the ways of Capitalism: his brother Raoul died of hunger because the family did not have enough money for food. His father was a university lecturer who decorated their rooms with portraits of executed revolutionaries. Victor's earliest memories were of adult conversations about "...trials, executions, escapes, and Siberian highways, with great ideas incessantly argued over, and with the latest books about these ideas". Idealism and self-sacrifice were the reigning values of his parents' milieu, and, although Victor was determined to abandon self-sacrifice as a positive virtue, he never could nor would abandon the revolutionary idealism of the Russians.

His earliest childhood friend was Raymond Callemin, born in Brussels in 1890, whose French father was a drunkard and an "old socialist disgusted with socialism" who patched shoes from morning till night. He disowned his son for keeping bad company. Together, Victor and Raymond read Zola's Paris and Louis Blanc's History of the French Revolution and joined the 'Socialist Young Guards'. Neither of them went to school or college because, as Victor put it, "learning was life itself". After some French deserters brought them a "whiff of the aggressive trade unionism of the anarcho-syndicalists" they became revolted with electoral politics and abandoned socialism, as it did not demand that harmony between deeds and words, the personal and the political, that anarchism appeared to demand: "Anarchism swept us away completely because it both demanded everything of us and offered everything to us". Absolute liberty was at the same time a revolutionary method for the individual and a revolutionary goal for everyone, to be realized immediately. This was both the greatness and weakness of anarchism as each individual's method could be argued as valid due to the 'truth' invested in its extrapolated conclusion.

After reading Kropotkin's To the Young People, Victor and Raymond decided to go and stay at a communitarian colony at Stockel in the forest of Soignes just south of Brussels. Over the gate hung the slogan from Rabelais: "Do what thou wilt". The colony had been founded by Emile Chapelier, an ex-miner and ex-con; here they met a cobbler, a painter, some primers, gardeners and tramps, a Swiss plasterer, an ex-officer from Russia converted to Tolstoyan anarchism, and Sokolov, a chemist from Odessa, the latter shortly to become infamous. The two teenage comrades quickly read their way through the series of pamphlets published by the French syndicalist confederation, the CGT; subjects covered included The Crime of Obedience, The Immorality of Marriage, Planned Procreation, The New Society and antimilitarist literature. For serious entertainment they read novels by Anatole France and poetry by the Belgian Emile Verhaeren or the Parisian Jehan Rictus, the latter famous for his Soliloquys of the Poor and use of the hard-style slang spoken on the streets.

The colony moved to Boitsfort, and here Victor Kibalchich learnt to proofread, edit, set-up and print their irregular four-page journal, Communiste. One day a newcomer arrived, having been unable to find work due to his known anarchist sympathies. Edouard Carouy, born in 1883 at Montignies-les-Lens, had had a hard childhood, both his parents having died when he was only three years old. He had spent many years apprenticed to a metal-turner in Brussels, and had subsequently worked in Malines, St Nicholas and the Dutch port of Terneuzen, where he'd pilfered from the docks. He too decided to make the colony his home.

In 1908, aged eighteen, Victor wrote his first article for the September issue (no 18) of Le Révolté, which/ was the old Communiste transformed; the format remained a small, four-page newsheet however. It was subtitled 'Organ of Anarchist Propaganda — appearing at least once a month' — later changed to twice a month.

Although the back page was devoted to the 'Mouvement Social', the paper was hostile to trade-unionism, the more so as the Belgian unions were mainly controlled by the Socialist Party. There were numerous occasions of anarchists being expelled from unions and being prevented from speaking at meetings. The conviction that theory and practice be unified in each individual's life led to Le Révolté adopting an approach very similar to that of l'anarchie; they sometimes printed reports from Paris, and shed a tear for the passing away of Libertad in their obituary.

Victor Kibalchich, alias Le Rétif, wrote many articles for the paper, including some that make interesting reading in the light of his subsequent involvement with the 'Bonnot Gang'.

In February 1909, under the title 'Anarchist-Bandits', he praised "our audacious comrades who fell at Tottingham [sic]" and expressed "much admiration for their unequalled bravery", which proved that "anarchists don't surrender". The comrades in question were Paul 'Elephant' Hefeld and Jacob Lepidus,[6] both sailors from Riga in Latvia, who belonged to a cell of the clandestine revolutionary network called 'Leesma' or ' Flame'.

They had carried out a wages snatch on a Tottenham (North London) engineering factory, and in the course of a chase lasting for several miles had shot almost two dozen of their pursuers, three of whom died, one being a boy of ten. The two men committed suicide, but not before successfully passing on their haul to a waiting accomplice who was never caught.

Le Rétif continued his article: "Reader, I detect on your lips a sentimental objection: But those poor twenty-two people shot by your comrades were innocent. Haven't you any remorse? — No! Because those who pursued them could only have been 'honest' citizens, believers in the State and Authority; oppressed perhaps, but oppressed people who, by their criminal inertia, perpetuate oppression: Enemies! For us the enemy is whoever impedes us from living. We are the ones under attack, and we defend ourselves".

In the next issue a reader protested against the article, saying that there was nothing anarchist about the reprise individuelle and that anarchists couldn't be thieves from above or below. Victor Kibalchich disagreed.

Not long afterwards a bomb was found in Brussels and claimed by the self-styled 'International Anarchist Group' to have been the work of their chemist. It had been destined for the ex-Minister of Justice, responsible for numerous expulsions of foreign refugees; the group also declared that it had recently carried out an expropriation of three thousand francs.[7] All this bravado led to the undoing of one of their members. Police in Ghent raided the house of twenty-two year-old Abraham Hartenstein, who was none other than Sokolov, the Odessa chemist from the old libertarian community of Stockel. At the sight of police uniforms he reacted as he would have done in Czarist Russia, he drew his revolver and shot two policemen dead. But he did not escape arrest.

Victor Kibalchich probably had a hand in drafting the statement printed in Révolté by the 'Brussels Revolutionary Group', which lashed out at the 'honest' anarchists who criticized Sokolov on the grounds that the situation in Belgium bore no relation to that in Russia. The BRG was defiant and supported Sokolov unconditionally, declaring that "anarchists do not surrender...we are in permanent insurrection!". Sokolov was sentenced to life imprisonment. As no further word was heard from the so-called 'International Anarchist Group' it could be inferred that its existence was in fact Sokolov's own creation, in the tradition of Bakunin's 'World Revolutionary Alliance'; anarchists sometimes show a surprising propensity for creating organizations.

During the summer of 1909, Kibalchich went to work in Armentières, just inside the French border, as a photographic assistant; he found lodgings in a small mining village outside Lille. One evening in July he attended an anarchist meeting in Lille and struck up a conversation with Mauricius who'd come from Paris, and was at the time the principal speaker on the Causeries Populaires circuit. Victor was evidently attracted by Mauricius' companion and apparently whispered to him: "Who's that skinny little bird with you?".

Henriette Maîtrejean, née Anna Estorgues, was better known as 'Rirette'; born in Tulle (Corrèze) in central France, she had come to Paris in 1905 in the company of her anarchist husband Louis whom she'd married at seventeen, a year after her conversion to anarchism. One day at the Sorbonne university, when she was nineteen, she met a 'scientific anarchist' whom she found more stimulating than her rather down-to-earth husband, the 'anarchist worker', and she began to while away her time with him in the Luxembourg Gardens. Although now only twenty-two years old she already had two young children, Maud and Chinette, but she still had the looks of a girl in her teens. The 'scientific anarchist' in question was in fact Mauricius. During the course of the meeting in Lille, Victor argued against her, but far from impressing her, only made her think "What a poser!".