Rebel Worker group

Rebel Worker 6

A Revolutionary Journal published by members of the Industrial Workers of the World

A very nice, very respectable, very useless Campaign

Humor or not, Or less, Or else!

Consciousness at the Service of Desire

[unnumbered page]

The Rebel Worker

A Revolutionary Journal published by members of the Industrial Workers of the World

Address subs and correspondence to:

The Rebel Worker

c/o Solidarity Bookshop

1947 North Larrabee

Chicago, Ill. 60614

This issue published in London, England, May Day, 1966

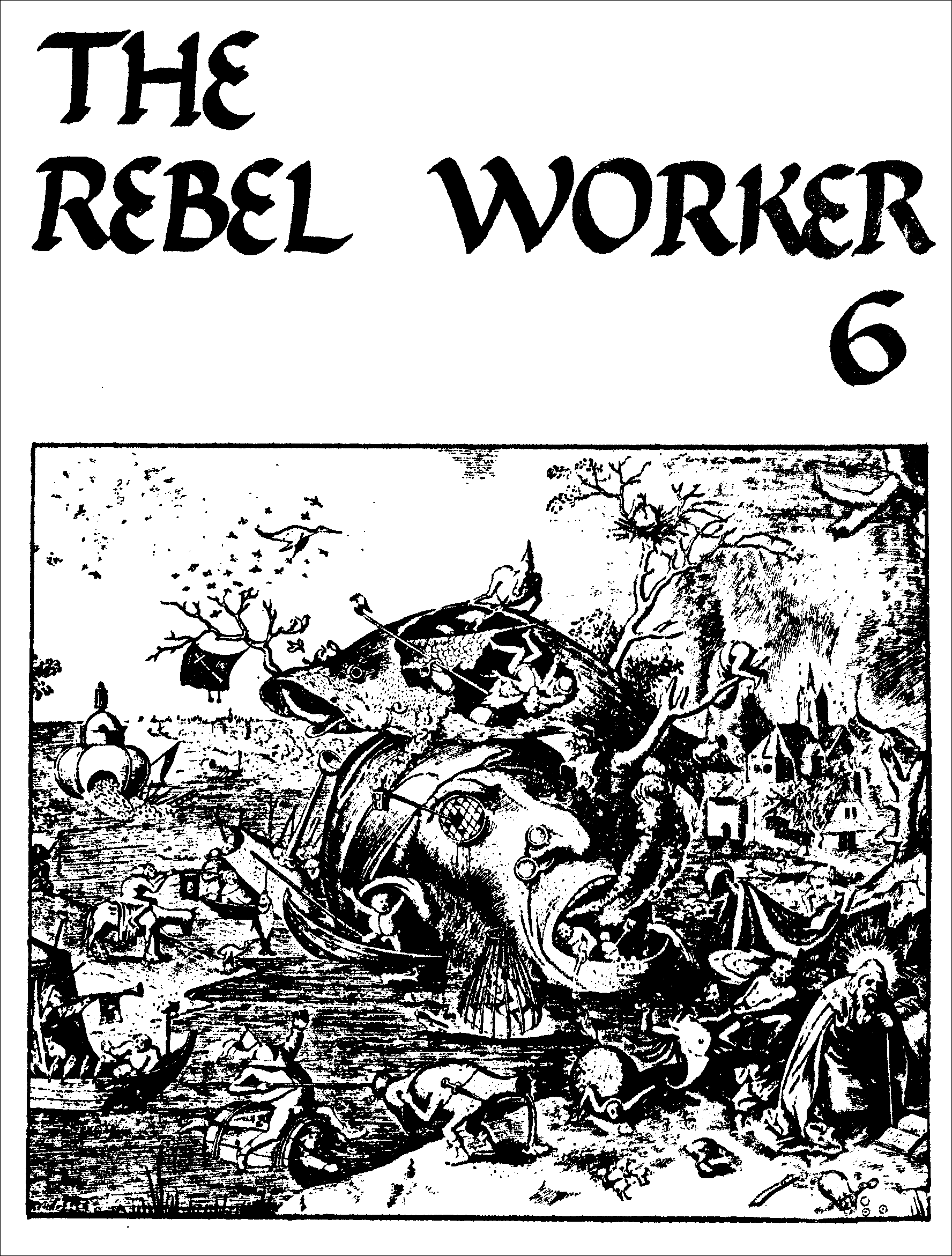

Cover by Charles RADCLIFFE

Notes

Pierre MABILLE was a leading surrealist theoretician of the 1930s and 1940s, author of La Conscience Lumineuse, Egregores, Le MIROIR du Merveilleux, etc. Another excerpt from this last work (“The Destruction of the World”) will appear in the forthcoming Rebel Worker pamphlet Surrealism & Revolution.

Karl MARX was a 19th century socialist whose works have exerted considerable influence on the revolutionary movement.

Kenneth PATCHEN is an un-American poet exiled in the United States.

Benjamin PERET was a surrealist poet and theoretician who fought in the ranks of the C.N.T. during the Spanish Revolution; author of Mort aux Vaches and many other works.

Archie SHEPP is a poet, playwright and one of the major tenor sax voices amongst the current jazz avant-garde. He has a number of albums available both in England and the U.S.—Fire Music (Impulse A86) is particularly recommended.

This is the first English “edition” of The Rebel Worker. Everyone who wants to put out further issues in England, and/or is interested in helping to do so should write-to the address below. We would also welcome letters and comments on this issue, as well as addresses of bookshops and individuals who wish to distribute copies of The Rebel Worker.

Charles RADCLIFFE

13 Redcliffe Road

London SW10

Anything appearing in The Rebel Worker may be freely reprinted, translated, or adapted, even without indicating its source, and we reserve the same freedom for ourselves regarding other publications.

Lost Whispers

This is the Chicago printing of Rebel Worker 6 (June, 1966), originally published in London on May Day, exactly two years since our first issue. Response to the London issue has been encouraging, both in terms of sympathetic letteres, subscriptions, and offers of future collaboration as well as the outcries and disdainful comments of traditional radicals and liberals. (One English cat said it was the first revolutionary paper which actually frightened him, Another, a member of the Young Communist League, said he would have none of these “little sects,” adding that he at least, belonged to a “well-organized group”!) Let us note here that the London Solidarity Group are graciously distributing 100 copies of the London printing for us; this is the group which publishes Solidarity, one of the best revolutionary periodicals in the world today—write to Bob Potter, 197 King’s Cross Road, London W.C.1; sample copies are available from us for 15 cents.

Charles Radcliffe, our London soul-brother, has written to us that further issues of an incandescent-carbonated journal sharing similar scandalous preoccupations with the Rebel Worker will appear there with the name Heatwave, adding its own delirious lucidity, vengeful humor and millenarian sensibility to the revolutionary movement in England. Heatwave #1 shall appear in 3–4 weeks—for details write to

Charles Radcliffe, 13 Redcliff a Road, London SW 10. Copies will, of course, be available from us at 25 cents each.

The London printing carried a last-minute-type cover, hastily prepared by Radcliffe portraying a bearded bombe-toting anarchist in a balloon; we have decided to use here, instead, an engraving (“The Temptation of St. Anthony”) by Radcliffe’s distant relative, the Flemish anarchist Pieter Bruegal the Elder. H. Arthur Klein, in his Graphic Works of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Dover Books, paperback) writes about this particular engraving: “In its drastic criticism of the conditions of both the Church and State, this may well be the most ‘outspoken’ of Bruegells graphic works. Corruption and decay beset both the State (the one-eyed head below) and the Church (the rotting fish above).” (p. 268) This engraving is for us a pretty accurate presentation of contemporary reality, although we feel that the curious figure in the lower right-hand corner (who) happens to be St. Anthony) is now historically and poetically outmoded, to say the least, and would perhaps be replaced best today by a passionate saboteur, armed to the teeth with mad love and the uncontrollable desire to be free.

On the back we have reprinted the text of a leaflet issued by The Anarchists of Chicago (April, 1966). The only other additions to this issue, aside from the cover, are this page of notes and the message from René Cravel, on the other side.

Au Grand Jour

The time is coming when seas of boiling rage will reverse the icy current of rivers, overflow and fertilize, fathoms deep, a crusted, petrified soil, tear away frontiers, uproot churches, clean the hills of bourgeois complacency, decapitate the headlands of aristocratic insensitivity, drown the obstacles, the exploiting minority set in the way of the mass of the exploited, restore humanity to its future by freeing it from outdated institutions, religious fears, jingoistic mysticism and all that constitutes and consecrates the evils of the majority for the benefit of the two-legged sharks, their mates and the whole gang.

—René CREVEL

Freedom

This sixth issue of The Rebel Worker is being produced in London, several thousand miles from its customary home in Chicago. We hope this issue, and subsequent ones, will help give our ideas a wider audience than they have had so far in Britain.

The Rebel Worker is an incendiary and wild-eyed journal of free revolutionary research and experiment devoted principally to the task of clearing a way through the jungle of senile dogmas and aiming towards a revolutionary point of view fundamentally different from all traditional concepts. We believe that almost all political propaganda is useless, being based on assumptions which are false and situations which do not exist. We are tired of the irrelevant concepts and the old platitudes. The revolutionary movement, in theory and in practice, must be rebuilt from scratch.

Many of us around The Rebel Worker are members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), once one of the largest and most powerful rank-and-file revolutionary organisations the world has ever seen. We have joined the IWW because of its beautiful traditions of direct action, rank-And-file control, sabotage, humor, spontaneity and unmitigated class struggle.

It is those principles that constitute our editorial basis, but our task is not limited to mere recruitment. Our role is: to promote “Whatever increases the confidence, the autonomy, the initiative, the participation, the solidarity, the equalitarian tendencies and the self-activity of the masses and whatever assists in their demystification.” We want and support revolutionary direct action on every level—in the factories, on the docks, in the fields, in schools, in colleges, in offices and in the streets. But this is not enough. Revolutionary action should be accompanied by theoretical understanding. The revolution must be made by men, women and children who know what they are doing. Consciousness and desire must cease to be perceived as contradictions.

The Revolution, for us, cannot be limited to economic and political changes; these are urgent and absolutely necessary, it is true, but we see them as a beginning rather than as an end; we see social liberation as the essential prerequisite, the first steps, in the total liberation of man.

It is especially to young people—young workers, students drifters, draft-dodgers, school dropouts—to whom we address ourselves and our solidarity: You are one of the largest and most oppressed sectors of our society, and it is you who must make the Revolution.

What we want, and what The Rebel Worker is about, in short, is Freedom—“the only cause worth serving.” **

Ben COVINGTON, Charles RADCLIFFE, Franklin and Penelope ROSEMONT

Nat TURNER, Emillano ZAPATA

* Paul Cardan, Modern Capitalism & Revolution (Solidarity)

** André Breton

A very nice, very respectable, very useless Campaign

When the anarchist poet Jeff Nuttall spoke at the final rally of this year’s CND easter march, he added new dimensions to the usual ritual, just as did the giant political puppet theatre which showed politicians as they really are—not just without conscience but small, grovelling men, sustained only by the persecuting knowledge of their own vacant treason to their humanity. By calling for the destruction of the Ministry of Defence Jeff Nuttall gave intention to an affair which had none of its own. By speaking he let it be known that any number of people saw in CND and its charmless entourage of parliamentary vipers nothing so much as the sell-out of a once genuine popular movement against nuclear war to the so-called immediate imperatives of political relevance and political advance.

Since the CND leadership made public its refusal to challenge society—after the Spies for Peace revelations in 1963—the Campaign has lived on borrowed time. The complex manoeuvres to present a libertarian image while denying to anarchists the right to speak at the rally, the dummy-protests and the dummy-members of Parliament are not going to save it. CND is doomed. It is time for a young movement which addresses the contemporary reality, a movement which will challenge every tiny aspect of our war-sustained society, even unto the last public utility, which will militarise the dissatisfaction of almost every young person in this country. For dissatisfaction is not confined to politics; it extends into every street, club and classroom.

It must be encouraged in its every aspect; its active expression may be welded into a revolutionary weapon which will strike fear into the deepest recesses of our society. Imagine briefly: if every time the police decided to victimise young people they were faced with the united fury of such people, if young people were to turn on their attackers with all the venom their frustration could muster. Then we might talk of protest.

Such a movement would support the emotional eruptions of all youth; would learn to sanction the outrages of youth recognising in them a kindred spirit—albeit a bolder one—in the rejection of the spiritual death of a society which has attempted too long and too successfully to postpone the irrefutable logic of its indifference—destruction. This society, if we will it, can drown in its own corrupted blood. It can die in its tracks—on the streets, in the clubs, in the factories. The new revolution may be obscene and blasphemous; it must deface the power structure when it cannot destroy it; the criterion is defiance not discipline.

The new revolution must support every last insurrection of the mind and body against this bloodfed society—our movement is symbolised by the bomb-thrower, the deserter, the delinquent, the hitch-hiker, the mad lover, the school drop-out, the wildcat striker, the rioter and the saboteur.

This year 500 anarchists caused a ‘near riot’ in Trafalgar Square, until the ‘platform’ capitulated to their demand for a speaker. Significantly it was Nuttall who spoke on their behalf, rather than an “Establishment anarchist” (as Peace News delights to term those comrades who are old enough to have sold out but have not done so). The anarchists were roundly condemned by the national press. The peace movement, as represented by Peace News, condemned them in more sophisticated fashion. (The dedication of the liberals to respectability has so clouded their vision that they no longer care about the effect of their actions, only that they should not be attacked for them). The relevance of the action of these predominantly young anarchists is obvious. Their voices and actions exploded their precise consciousness of the fact that respectability finally involves simply this: Clamber into your own arsehole and quietly die.

—Charles RADCLIFFE

Souvenirs of the Future

Precursors of the theory & practice of total liberation

Franklin ROSEMONT

It is clear that man has lost his comfortable foothold in the provincial, one-dimensional flatlands where bourgeois society originally built its little mental world. The peace-loving resident of the suburbs, for instance, used to looking outside and seeing only his overfed neighbor or somebody’s excuse for an automobile, now sees through his window only the most terrible darkness, the most violent natural calamities, the most permanent insurrections. He may try, fond as he is of wearing a heavy overcoat of ignorance wherever he goes, to lose himself before his television set, or in an uninspired affair with his best friend’s wife; he may even succeed in utterly exterminating the last traces of the free play of his imagination by utilising any of the various means lying conveniently along a well-trod path of emotional and intellectual exhaustion: golf, for instance, or watching baseball. But such efforts are useless. Every scream of protest and genuine anger, every signal of true resistance, whether expressed in wildcat strikes, in certain strains of pop music, in violence against the police on anti-war demonstrations, in ghetto uprisings, in the blues, in jazz, in poetry or in guerilla warfare against the state—wholehearted revolt in any and every form—gives the lie to the fact and hypocritical complacency of those who cower in fear behind locked doors, afraid of the people in the streets, afraid of their own children, afraid of everything that gets in the way of their stupidity, afraid—above all of any vestige of a human being concealed within themselves.

It is also clear, however, that the presently emerging movement of protest is too little conscious of the implications of its actions, too unsure of whence it came, where it is going and why. Certainly one of the most important tasks of a revolutionary journal is to expand, broaden and deepen this consciousness. The motives, inspirations and aspirations of the present movement, of which The Rebel Worker constitutes one of the more adventurous forces, cannot be understood properly without a complete re-valuation of revolutionary values as well as a vast reassessment of the whole revolutionary tradition, necessarily involving research into, and reinterpretation of, all levels and all varieties of past struggles. This requires the complete repudiation of those pitiful “radicals” who look to history only to justify themselves and their actions with the “sacred texts,” and who thus demonstrate only their weakness and blindness in confronting the reality of today. It goes without saying that we reject, absolutely, both those who choose to hide themselves in the past, or attempt to impose the past upon the future (reactionaries of all traditional varieties) and those who manipulate the past to conceal or distort the true nature of the present (liberals, social democrats, elitist “socialists,” conservatives, etc.). “In matters of revolt,” as André Breton once said, “one should not need ancestors.” It is no less true that we must redefine the past according to the needs of the future determined by the situation of the present.

If there are a few people of the past whose words are still meaningful for us today, it is obvious that they cannot be the same ones presented to us for our admiration in school. Teachers, after all, in class society, are usually little more than cops, and who can respect the same things as a cop? The most relevant voices of the past are not the ones sanctified in the bourgeois mausoleum of heroes. The degree to which they are acceptable to this society is the degree to which they are useless to us. Nor can we hope to find most of them in the genealogy cherished by the traditional left, whose dogmatism, sectarianism, humorlessness, elitism and myopia we reject here as in everything else. The revolutionary movement, presently rebuilding itself from scratch, will have to re-envision its history from scratch as well. In particular, I think it is necessary now to give special consideration to precisely those past revolutionaries who have been most consistently ignored by the traditional left. It is also essential that we do not seek from them exclusively political or economic or even sociological revelations. “In periods of political inactivity,” as fellow worker Lawrence DeCoster wrote not long ago, “the greatest hope of revolutionaries lies in non-political activity.” (Of course we must also work like hell to revive serious rank-and-file political activity, primarily on the shop-floor level and in the streets where it matters most.) Today, with the resources of psychoanalysis, surrealism, anthropology, the physical and biological sciences being placed increasingly at the service of the revolution, we know that certain allegedly “non-political” works of the past are more thoroughly subversive, more liberating, more revolutionary than the most obviously “political” works of the same period. Every effort of man to realize his dreams in total freedom is revolutionary. But politics, by itself, no matter how revolutionary, remains a partial truth.

Let us note here a few of those whom we can unhesitatingly affirm as precursors of our own theoretical and practical activity, a few desperate enchanters whose magical lucidity still burns in our eyes today, a few lone soul brothers of whom we can still speak in connection with freedom. Academic and journalistic parasites may attempt to obscure them with their false elucidations, or ignore their work through the ignoble “conspiracy of silence,” but nothing will stop us from pouring into the crucibles of the revolution these splendidly subversive inspirations and implacable dreams:

Lautréamont

It was Aragon who, before his Stalinization, observed that just as Marx had laid bare the economic contradictions of society, and Freud the psychological contradictions, so Lautréamont threw into a dazzling new light the ethical contradictions: the whole problem of morality, not to mention such other problems as the animalization of the intellect and the purpose of literature, assume with Lautréamont an excruciating significance next to which most of the philosophical babbling of his contemporaries seem to us today as nothing more than a handful of lies. The importance of Lautreamont on the ideological development of surrealism is second to none. His work has been called “a veritable bible of the unconscious;” the validity of many of his discoveries and revelations were subsequently demonstrated by Freudian psychoanalysis. It can probably be generally agreed that the liberal-humanist pantheon has, in the last century and especially during this century, crumbled to ruins; and it is Lautreamont whose criticism of it was most thoroughly, most devastatingly to the point, and who, moreover, best indicated a way out of the morass of confusion by rallying around the “reality of desire” which, theoretically elaborated by surrealists, remains the key to our most revolutionary aspirations.

Fourier

The traditional left of the 20th century has almost invariably consigned the many so-called “utopian socialists” to a position amounting to historical irrelevance, assuming them to be of interest exclusively for their influence on Marx and Engels, or Proudhon and Bakunin. Critical re-examinations of utopians by revolutionaries have occasionally appeared, and sometimes they are very good (see, for instance, Marie-Louise Berneri’s Journey Through Utopia, which discusses not only the best-known utopians but also Winstanley, Diderot, Sade, William Morris, etc.). But much more still needs to be done. In particular the fantastic and visionary works of Charles Fourier (whose delirious cosmology and “passional psychology,” no less than his penetrating social analysis, intrigued Marx and later Trotsky as well as many anarchists) deserve sympathetic and serious study. Fourier, more than any of the other utopians, pioneered many of our own preoccupations. He was very aware, for instance, of the central problem of love and the crucial role of human passions in social life. He insisted on the necessity of completely changing the very fabric of life to meet the needs of desire. The implications of his theory of analogy suggest a possible new development in revolutionary theory. His Importance, in any case, cannot be limited to the experimental rural phalansteries (Fourier’s name for communes) of his disciples—which are important too, of course, but in a very different way—nor to his most immediate influences on later socialists: it is above all Fourier the poet and seer who interests us today.

Sade

The theoretical and imaginative work of the Marquis de Sade, along with the practical efforts of the celebrated Enragés, can be considered, from the revolutionary point of view, the highest points reached during the French Revolution (and the so-called Age of Reason). The rising bourgeoisie was anti-feudal, anti-monarch, anti-superstition: but its talk of liberty and reason soon reduced itself to platitudes to be carved by the State above the doors of prisons—it was a limited freedom, freedom defined to meet the needs of only one comparatively small class of exploiters. The Enragés struggled for a deeper revolution, representing the class needs of the proletariat: this effort was to receive its theoretical analysis and justification later, first in certain workers’ papers and eventually in the monumental contributions of Marx and Engels. Sade, too, realized the inherent weaknesses of the revolution (see particularly his Frenchmen! One More Effort If you Wish to be Republicans, which was, incidentally, reprinted as revolutionary propaganda in the struggles of 1848). He was aware of the social conflict—the class struggle—but brought to his analysis a consciousness of other problems (love, sexuality, desire, crime, religion, etc.) which were not to receive systematic exploration until surrealism. His works, which have at various times been reduced to providing tea-party chatter for senile litterateurs, and are currently enjoying a paperback revival (doubtless for being “classic pornography”), should now be read by everyone struggling for a revolution which will not end in a new set of chains.

Blake

The editions of his own works printed by William Blake are highly prized by cretinous bourgeois rare book collectors (let us spit in their faces and note in passing that everything he wrote spit in their faces too). Probably the greatest poet in the English language, most radicals seem to know nothing about him in connection with revolutionary politics other than the fact that he hid Thomas Paine, who at the time was wanted by the British government. It is insufficient to add that, in England at least, his poem “London” has become a “socialist” hymn: for Blake’s importance lies far beyond any isolated minor work which can be unfairly harnessed to the anti-working-class needs of the Labour Party. Let us note only that Blake was, for a time, associated with the circle that included William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, and that he and his works are thoroughly imbued with the revolutionary ideas of his epoch. But Blake saw much farther than any of the other English radicals of his time, and his works—which are only now really becoming active influences on the revolutionary movement—bear witness to the extraordinary depth of his perception and the prophetic surreality of his vision. The Revolution, too, will become “non-Euclidean:” common sense, already abandoned in almost every significant contemporary thought current (non-Euclidean geometry, non-Maxwellian physics, non-Newtonian mechanics, probability theory, psychoanalysis, general relativity theory, surrealism, etc.) must give way in revolutionary politics, as well, to less limited points of view, to superior methods of knowledge. Blake cut through the superficial rationalism of his day with the axe of poetry and vision. It is true that the semi-religious symbolism he often employed has detracted somewhat from the truly subversive, anti-religious and liberating message of his works; but compared to his contemporaries—and that was a revolutionary age!—Blake was the brightest star in a cloudy, moonless night.

The Gothic Novelists

Professional literary critics and academics today are practically unanimous in their rejection of that extraordinary profusion of works of the late 1700s and early 1800s usually known as “Gothic novels.” These tales of haunted and crumbling castles, apparitions in the night, maddening lust, pacts with the devil and bleeding nuns are quite evidently not suited to the refined tastes of our numerous literature experts, who dismiss the entire genre as “musty claptrap” or with some such other derisive appellation. Like most matters of interest to us, the academics put them down, utterly missing the point. These works, like the real meaning of the revolution, are simply beyond their understanding. What makes the Gothic novels of special importance is both the immense popularity they enjoyed at the time of their publication (they were the best-sellers of their day) and also the great influence they exerted upon some of the most brilliant and critical minds of the younger generations: Shelley, Byron, Coleridge, Sade, Hugo, Baudelaire, the Bronte sisters, etc. Very few works of any period enjoy this double privelege: it was, I believe, André Breton who first pointed out that these works were highly successful expressions of the latent content of the period in which they were Written (i.e., the days of the bourgeois revolutions). Now certainly one of the greatest weaknesses of the traditional left has been its neglect of the problems of the individual, and human personality in general; these have been ignored through the exclusive preoccupation with social problems, analysis of which in turn has been weakened through ignorance of psychology. There has been, for instance, little investigation of the psychological changes occurring during periods of great social upheavals (or for that matter, little investigation of the psychology of factory workers). It is obvious that people who support reactionary candidates in bourgeois elections do not think the same way as do the people who take over the factories and smash the government. Workers as a class cannot make a really successful revolution (that is, one leading to complete freedom) unless they are individually, psychologically, as well as socially, capable of it. That is why it is important for revolutionaries to reinforce spontaneity, creativity, self-reliance, independence and rebellion of individual workers as well as of the working class. (This is also one aspect of the relevance and importance of sabotage, In individual act serving the needs of the class.) Obviously much more work must be done along these lines. Meanwhile, we should re-study the imaginative works of sensitive writers of the past who, more or less automatically, documented some aspects of this Problem. In particular, the greatest of the Gothic novels (Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto, Lewis’s The Monk, Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer) offer us valuable testimony in tracing the genesis and evolution of individual revolutionary sensibility, the latent and personal drama unfolding with the manifest and general cataclysm.

Of course we have only penetrated the surface of a hardly-explored sea, to which no limits can yet be assigned. Living, as we do, in a civilization rapidly falling to ruin, it is up to us to trace the trajectory of its destruction, to propel it further along this path, to read the prophecies of tomorrow’s dawn with a defiantly critical eye, to explore all the unknown worlds inside and outside of man, and, eventually, to pool our collective resources with our billions of fellow workers and soul brothers in the really fundamental tasks of the Revolution: to realize our desires, and “to rebuild human understanding,” as Breton put it, “from scratch.”

We must remember that we are in the preliminary stages of our experiment. We know that we cannot build a new revolutionary movement with the skeletons of the old. The old left has taught us very little of what we want to know; we must learn to teach ourselves. Every exploration must be the preface to several others. Every new dream must lead to new actions.

We are children, we are savages; we are dangerous and godless. We possess an extraordinary ruthlessness, a profound sense of the marvellous, an aggressive consciousness of our dreams. And, in our hands, the dialectical materialist conceptions of history and desire become a beautiful red and black wolf to set at the door of those who deny us our freedom.

Humor or not, Or less, Or else!

Penelope ROSEMONT

“Humor is not resigned; it is rebellious. It signifies the triumph not only of the ego but also of the pleasure principle...”

—Freud

“Beautiful as the fortuitous encounter, upon a dissecting table, of a sewing-machine and an umbrella.”

—Lautréamont

Humor, which has long been neglected by many so-called revolutionaries in their attempts to prove to themselves that their intentions are altogether noble and serious (no doubt, also, because of the desolation and barrenness of their thinking), ought to be given the recognition it has long deserved and regain its rightful place in the revolutionary struggle.

The Wobblies have long been recognized for the humor they have contributed to the class struggle, for instance their use of humor as a means of lowering the boss’s self-esteem to a minus one, often expressed in acts of collective sabotage such as the planting of cherry trees upside down with their roots blowing in the wind. Another famous incident in the history of revolutionary humor occurred when I.W.W. construction workers, whose pay had been cut in half, reported for work the:following day with their shovels similarly cut in half. (The pay was raised.)

“Sabotage is the soul of wit.” (Solidarity, 1913–15).

Besides these examples of on-the-job humor there is the Little Red Song Book containing such songs as “The Preacher and the Slave” which mocks the famous religious hymn “In the Sweet Bye and Bye” used by the Starvation Army when it tried to sell its “pie in the sky.” And the telegram which Joe Hill sent before he was legally murdered, in which he asked his fellow workers to come get his body because he didn’t want to be “caught dead” in Utah... And, aside from being the greatest of the IWW writers, T-bone Slim is also one of its greatest humorists. (Watch for reprints of his writings as well as previously unpublished material in forthcoming issues of The Rebel Worker.)

Humor has vast, as yet only partially realized, powers as a polemical weapon. Its users can with the least possible effort pull the keystone out of any argument leaving his opponent standing stunned amid a pile of bricks. Solidarity, for instance, one of the outposts of revolutionary humor today, once recommended that non-violent demonstrators “go limp and refuse to bleed.”

The movies of the Marx Brothers, Charlie Chaplin, Bugs Bunny are all implicitly dangerous to bourgeois society; they express their bitterness and aggression in humor. They attack society and everything it holds dear and if you do not leave the movie theatre and destroy the nearest squad car, it’s your fault, not theirs.

Potential potentates are notorious for their lack of humor and their total inability to cope with it. The entire functioning of a bureaucracy depends on the fact that it is taken seriously. The bureaucrat as an individual usually has little control over the violence which is at the command of the state. This is functional in that it serves to absolve him of any guilt which might result from the use of this violence, for in a bureaucracy as in a firing squad no one really knows who has the live bullet. Bureaucrats have at their disposal little more than the prestige, respect and all the trappings of their position. They take themselves and their positions utterly seriously, and because of this it is possible to utterly demolish both them personally and also the sacristy of their office. Humor is the archenemy of prestige!

The most violent and extreme form of humor, known as black humor, has found its greatest expression in the work of Lautréamont, Alfred Jarry, Jacques Vaché and Benjamin Péret. A popular, if diluted, variety of black humor is found in the elephant jokes and “sick” jokes (What is black and white and lies in the gutter? A dead nun). An example of proletarian black humor which originated during the Spanish Revolution of 1936 is the saying “hang the last politician with the guts of the last priest.” Unlike other forms of humor, black humor is totally unacceptable to present society. It has an extremely disturbing effect because whereas milder wit functions merely to deflate the ego of the person whom it happens to be used against, black humor threatens it and devastates it.

It surveys reality, sees through it and exposes it. Black humor releases all the power of unconscious desire.

Through the adoption of humor as a conscious attitude we can assert ourselves over the confines of environment, reality, and in effect topple the whole structure and reassemble it as we wish, thus revealing a glimpse of the pride which the Revolution will restore to man. Revolutionaries must be the enemies of reality—they must be poets and dreamers with uncontrollable desires that will not be repressed, sublimated or sidetracked. They must be willing to be ruthless. The economic change brought by the Revolution is only the first of our demands: we will not be content with anything less than the total annihilation of existing reality and the total triumph of Desire.

Consciousness at the Service of Desire

Pierre MABILLE

From Le Miroir du Merveilleux (excerpt reprinted from the surrealist review London Bulletin, June 1940)

He who wishes to attain the profoundly marvellous must free images from their conventional associations, associations always dominated by utilitarian judgmemts; must learn to see the man behind the social function, break the scale of so-called moral values, replacing it by that of sensitive value; surmount taboos, the weight of ancestral prohibitions, cease to connect the object with the profit one can get out of it, with the price it has in society, with the action it commands. This liberation begins when by some means the voluntary censorship of the bad conscience is lifted, when the mechanisms of the dream are no longer impeded. A new world then appears where the blue-eyed passerby becomes a king, where red coral is more precious than diamond, the toucan more indispensable than the cart-horse. The fork has left its enemy the knife on the restaurant table, it is now between Aristotle’s categories and the piano keyboard. The sewing machine, yielding to an irresistable attraction, has gone off into the fields to plant beetroot. Holiday world, subject to pleasure, its absolute rule, everything in it seems gratuitous and yet everything is soon replaced in accordance with a truer order, deeper reasons, a rigorous hierarchy.

In this mysterious domain which opens before us, where the intellect, social in its origin and in its destination, has been abandoned, the traveller experiences an uncomfortable disorientation. The first moments of amusement or alarm having passed, he must explore the expanse of the unconscious, boundless as the ocean, likewise animated by contrary movements. He quickly notices that this unconscious is not homogeneous; planes stratify as in the material universe, each with their value, their law, their manner of sequence and their rhythm.

Paraphrasing Hermes’ assertion that “all is below as what is above to make the miracle of a single thing,” it is permissible to assert that everything is in us just as that which is outside us so as to constitute a single reality. In us the diffuse phantoms, the distorted reflections of actuality, the repressed expressions of unsatisfied desires mingle with the common and general symbols. From the confused to the simple, from the glitter of personal emotions to the indefinite perception of the cosmic drama, the imagination of the dreamer effects its voyage, unceasingly, it dives to return to the surface, bringing from the depths to the threshold of consciousness the great blind fish. Nevertheless, the pearl-fisher comes to find his way amid the dangers and the currents. He manages to discover his bearings amid the fugitive landscape bathed in a half-light, where alone a few brilliant points scintillate. He acquires little by little the mastery of the dark waters.

But the mind is not content to enjoy the contemplation of the magnificent images it sees while dreaming, it wishes to translate its visions, express the new world which it has penetrated, make other men share therein, realize the inventions that have been suggested to it. The dream is materialized in writing, in the plastic arts, in the erection of monuments, in the construction of machines. Nevertheless, the completed works, the acquired knowledge, leave untouched, if not keener, the inquietude of man, ever drawn to the quest of individual and collective finality, to the obsession of breaking down the solitude which is ours, to the hope of influencing directly the mind of others so as to modify their sentiments and guide their actions, and, last and above all, to the desire to realize total love.

The Haunted Mirror

Franklin and Penelope ROSEMONT

Paris, March, 1966

The gray pillow decorates the omnivorous moon, upsetting the wizard’s organ of the electric sidewalk. Later, the silence grows sinister and delinquent. The old women run frequently, and the monkey loses track of the crisp cathode. There is a striped squirrel on the roof, and a staircase on the bridge or bog. The night is as spacious as a sacrificed mirror, and all I know is that I love you because goldfish are cavernous and the sea is as singular as a rose.

Meanwhile, the cliffs overlook the visible waves, and the trees are black with ostriches. The automobiles entice the chairs in the desirable rain, as if the pedestrians had all recalled their spiral doorbells. The streets are full of rugs and windows; the shopwindows full of waves. Who knows what the thunder will be like tomorrow, or the day after? The wheels are forlorn like the sleeping finger, or the tigers running loosely on the shore, observed only by the prickly scorpion, who sleeps with one eye open as wide as a paper and always keeps another eye bearded next to his winding ear.

Finally, the woman cuts open the resourceful pendulum. There are the usual uncanny screams, the bloodstains on the sky, astonished limits in the dimly-lit ocean. The wolves are rheumatic. The house burns foolishly like a sacrificial accordion. The deceptive goat lies in the osteopath’s bed. Every door leads to a new thief; but the blind adjectives own all the pencils,:Every old winner is an alphabetical loser, every red table a letter of white sugar. Fallacious pipes are always rare, and I love you as madly as the sky is contagious.

Paris, March, 1966

Crime against the bourgeoisie

Ben COVINGTON

I first heard about The Who before they were The Who; just another mod r ‘n’ b group, playing one of Central London’s most fiercely mod clubs, but apparently doomed to remaining unknown outside a small circle of fans, despite their defiantly hip name—the High Numbers. I didn’t hear any more about them for nearly two years, when suddenly a rash of posters appeared in Central London advertising a new group—The Who. The posters were superb—heavily shadowed, crudely dramatic and featuring The Who lead guitarist, Pete Townshend, his arm raised in an arc over his head, his guitar barely visible. A few months before they had been unknown, under the new name, outside the Shepherds Bush area but gradually the news spread that the Marquee Club—whence came, among others, the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, the Moody Blues and Manfred Mann—had a fantastic new group. They were taken up by Melody Maker, the hippest British music weekly, and shortly afterwards by Record Mirror.

Despite the enthusiasm of the fans—the musical press, for the most part managed little more than perplexed astonishment—The Who’s first record, “I Can’t Explain”, one of the best pop records of 1965, didn’t really move nationally at first though it created enough interest in the group for their explosive views about pop to gain some attention. More people went to the Marquee. Provincial fans carried back the news. The record took off, finally making the top ten. When The Who made their second record, “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere”, they were again able to go almost into the Top Ten. The weird feedback sound effects, the carefully cultivated Pop Art image—the wearing of jackets made from the Union Jack and sweat shirts embroidered with the free-form sound effects of American comics, as well as military insignia—and later their championship of auto-destructive pop guaranteed them attention in a world where long hair was becoming more a recommendation for respectable employment than a mark of depravity.

The Who’s stage act is a shattering event. They start off quietly but providing the audience is with them they soon turn on the special effects. The singer, Roger Daltrey, legs slightly apart, torso jutting forward, begins to smash his microphone with a tambourine, first gently and then with increasing fury until the amplifiers howl. Alternatively he crashes a hand-mike against the cymbals or screams harshly into the microphone, leaning forward at an absurd angle, his body straight, held above the stage by the microphone stand. While singing he cavorts round the stage in the curiously paralytic dance of a reigning mod. Occasionally he blows harmonica, furiously and grotesquely, like the screeching of a moon-struck tom cat. One way or the other he often leaves microphones smashed. Meanwhile Pete Townshend, face bland and impassive, creates banshee howls, stutters and the staccato burr of distant machine guns from feedback and by scraping his instrument against the amplifier, before finally smashing it into the amplifier to produce the noise of tearing metal and screeching car tyres. His arm swings wildly, higher than his head, arcing before smashing back onto the guitar. He strikes chords and his arm swings in circles, faster and faster. He holds a pose, arm extended, before’ once again swinging onto his guitar. Or, he holds his guitar at the hip, shooting notes at the audience. The Who’s stage act can end with his guitar hurled into the crowd. John Entwhistle, on bass-guitar, keeps the thread of the group’s performance with heavy double rhythms and a driving bass line. Drummer Keith Moon, mouth wide open; head gyrating from side to side, eyes wide and glazed,thunders out a furious rhythm, acknowledging the howls of the crowd for whom he has always been the main attraction.

The whole effect of The Who on stage is action, noise, rebellion and destruction—a storm of sexuality and youthful menace. They proudly announced after the success of “Anyway” that their next record was going to be anti-boss, anti-war and anti-young marrieds.

The result was this:

“People try to put us down

just because we get around.

Things they do look awful cold

Hope I die before I get old

my generation, this is my generation, baby,

Why don’t you all f-f-fade away

Don’t try to dig what we all say

Not trying to cause a big sensation

Talking about my generation.”

“My Generation” was the most publicised, most criticised and possibly the best record yet by The Who.

If it didn’t entirely live up to its expectations and if it wasn’t quite so unrecalcitrantly hip as “Anyway” the offence it caused—particularly when the group announced that the singer was supposed to sound ‘blocked’ (high) on the record—was extremely gratifying.

There is violence in The Who’s music; a savagery still unique in the still overtly cool British pop scene. The Who don’t want to be liked; they don’t want to be accepted; they are not trying to please but to generate in the audience an echo of their own anger. If their insistence on Pop Art, now dying a little, is reactionary—for of all art, pop art most completely accepts the values of consumer society—there is still their insistence on destruction, the final ridicule of the Spectacular commodity economy.

Townshend’s room has shattered guitars hanging as trophies on the wall. There is also their insistence on behaving as they wish, Townshend told Melody Maker:

“There is no suppression within the group. You are what you are and and nobody cares. We say what we want when we want. If we don’t like something someone is doing we say so. Our personalities clash, but we argue and get it all out of our system. There’s a lot of friction, and offstage we’re not particularly matey. But it doesn’t matter. If we were not like this it would destroy our stage performance. We play how we feel.”

Likewise their manager told reporters that he saw their appeal lying in rootlessness. “They’re really a new form of crime—armed against the bourgeois. Townshend talked defiantly on the ‘hip’ TV show, “Whole Scene Going,” to denounce the other members of the group, the pop scene, society at large, and non-drug users in particular. “Drugs don’t harm you. I know, I take them. I’m not saying I use opium or heroin, but hashish is harmless and everyone takes it.” Townshend’s views, which he expresses freely and frequently, are weirdly confused. On the General Election: “Comedy must come in the end and it just has...I think the tories will win because so many people hate Wilson...I still reckon English Communism would work, at least stronger trade unions and price freedom. I’ve always been instructed by local communists to vote Labour if I can’t find a Communist candidate. The British C.P. is so badly run—sort of making tea in dustbins like the Civil Defence.” On the Chinese: “They are being taught to hate. But they are led by a great person who can control them.” In the same Melody Maker interview he came out against the Vietnam war but curiously did not support the Vietcong, complained about vandalism in phone booths and Keith Moon getting old (“Once—if I felt ageing, I could look at Keith and steal some of his youth”). The conscious revolution, if at all, is however submerged under the unconscious and consuming fury of The Who.

The Who are at full volume; despite predictions of their imminent demise they have two records in the English charts and they will not die until they are replaced by a group offering more far-reaching explosions of sounds and ideas. The Who are symptomatic of discontent. Their appearance and performance alike denounce respectability and conformity. They champion their own complete expression of feeling. Bernard Marszalek has written: “One can only work towards this goal (‘the intrusion of desire with all of its marvellous aspects into a decadent and crusted society’) by developing with youth a sense of rage and urgency to unite the realms of dream and action fearlessly and with candor.” *

The Who may be a small particle of this explosion but they have a power unlike any other pop group’s; on a good night The Who could turn on a whole regiment of the dispossessed.

* Freedom, London, April 23, 1966

I am Not Angry: I am Enraged!

Archie SHEPP

I address myself to bigots—those who are so inadvertently, those who are cold and premeditated with it. I address myself to those “in” white hipsters who think niggers never had it so good (Crow Jim) and that it’s time something was done about restoring the traditional privileges that have always accrued to the whites exclusively (Jim Crow). I address myself to sensitive chauvinists—the greater part of the white intelligentsia—and the insensitive, with whom the former have this in common: the uneasy awareness that “Jass” is an ofay’s word for a nigger’s music (viz. Duke and Pulitzer).

Allow me to say that I am—with men of other complexions, dispositions, etc.—about art. I have about 15 years of dues paying—others have spent more—which permits me to speak with some authority about the crude stables (clubs) where black men are groomed and paced like thoroughbreds to run till they bleed or else are hacked up outright for Lepage’s glue. I am about 28 years in these United States, which, in my estimation is one of the most vicious racist social systems of the world—with the possible exceptions of Southern Rhodesia, South Africa and South Viet Nam.

I am, for the moment, a helpless witness to the bloody massacre of my people on streets that run from Hayneville through Harlem. I watch them die. I pray that I don’t die. I’ve seen the once-children-now men of my youth get down on stag, shoot it in the fingers, and then expire on frozen tenement roofs or in solitary basements, where all our frantic thoughts raced to the same desperate conclusion: “I’m sorry it was him; glad it wasn’t me.”

I have seen the tragedy of perenially starving families, my own. I am that tragedy. I am the host of the dead: Bird, Billie, Ernie, Sonny, whom you, white America, murdered out of a systematic and unloving disregard. I am a nigger shooting heroin at 15 and dead at 35, with hog’s head cheeses for arms and horse for blood.

But I am more than the images you superimpose on me, the despair that you inflict. I am the persistent insistence of the human heart to be free. I wish to regain that cherished dignity that was always mine. My esthetic answer to your lies about me is a simple one; you can no longer defer my dream. I’m gonna sing it. Dance it. Scream it. And if need be, I’ll steal it from this very earth.

Get down with me, white folks. Go where I go. But think this: injustice is rife. Fear of the truth will out. The murder of James Powell, the slaughter of 30 Negroes in Watts are crimes that would make God’s left eye jump. That establishment that owns the pitifully little that is left of me can absolve itself only through the creation of equitable relationships among all men, or else the world will create for itself new relationships that exclude the entrepreneur and the procurer.

Give me leave to state this unequivocal fact: jazz is the product of the whites—the ofays—too often my enemy. It is the progeny of the blacks—my kinsmen. By this I mean: you own the music, and we make it. By definition then, you own the people who make the music. You own us in whole chunks of flesh. When you dig deep inside our already disembowelled corpses and come up with a solitary diamond—because you don’t want to flood the market—how different are you from DeBeers of South Africa or the profligates who fleeced the Gold Coast?

I give you, then, my brains back, America. You have had them before, as you had my father’s, as you took my mother’s: in outhouses, under the back porch, next to the black snakes who should have bitten you then.

I ask only: don’t you ever wonder just what my collective rage will—as it surely must—be like, when it is—as it inevitably will be—unleashed? Our vindication will be black as the color of suffering; is black, as Fidel is black, as Ho Chi Minh is black. It is thus that I offer my right hand across the worlds of suffering to black compatriots everywhere. When they fall victim to war, disease, poverty—all systematically enforced—I fall with ‘them, and I am yellow skin, and they are black like me or even white. For them and me I offer this prayer, that this 28th year of mine will never again find us all so poor, nor the rapine forces of the world in such sanguinary circumstances.

I leave you with this for what it’s worth. I am an antifascist artist. My music is functional. I play about the death of me by you. I exult in the life of me in spite of you. I give some of that life to you whenever you listen to me, which right now is never. My music is for the people. If you are a bourgeois, then you must listen to it on my terms. I will not let you misconstrue me. That era is over. If my music doesn’t suffice, I will write you a poem, a play. I will say to you in every instance, “Strike the Ghetto. Let my peeple go.”

(Archie Shepp’s article is reprinted here in part from Down Beat, where it presumably had a readership akin to the magazine’s policy of wooly blue-eyed liberalism. We hope this reprint will let his words reach a small part of the audience they deserve. We agree with what he says but think Fidel and Ho would sell him short. Maybe one day we’ll get the chance to discuss this with him.)

Money

Karl MARX

From the Economic & Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 (Bottomore translation)

The power to confuse and invert all human and natural qualities, to bring about fraternization of incompatibles, the divine power of money, resides in its character as the alienated and self-alienating species-life of man. It is the alienated power of humanity.

What I as a man am unable to do, and thus what all my individual faculties are unable to do, is made possible for me by money. Money, therefore, turns each of these faculties into something which it is not, into its opposite.

If I long for a meal, or wish to take the mail coach because I am not strong enough to go on foot, money provides the meal and the mail coach; i.e., it transforms my desires from representations into realities, from imaginary being into real being; in mediating thus, money is a genuinely creative power.

...The difference between effective demand, supported by money, and ineffective demand, based upon my need, my passion, my desire, etc. is the difference between being and thought, between the merely inner representation and the representation which exists outside myself as a real object.

If I have no money for travel I have no need—no real and self-realizing need—for travel. If I have a vocation for study but no money for it, then I have no vocation, i.e., no effective, genuine vocation....Money is the external, universal means and power (not derived from man as man or from human society as society) to change representation into reality and reality into mere representation. It transforms real human and natural faculties into mere abstract representations, i.e., imperfections and tormenting chimeras; and on the other hand, it transforms real imperfections and fancies, faculties which are really impotent and which exist only in the individual’s imagination, into real faculties and powers. In this respect, therefore, money is the general inversion of individualities, turning them into their opposites and associating contradictory qualities with their qualities.

Money, then, appears as a disruptive power for the individual and for the social bonds, which claim to be self-subsistent entities. It changes fidelity into infidelity, love into hate, hate into love, virtue into vice, vice into virtue, servant into master, stupidity into intelligence and intelligence into stupidity.

Since money, as the existing and active concept of value, confounds and exchanges everything, it is the universal confusion and transposition of all things, the inverted world, the confusion and transposition of all natural and human qualities.

He who can purchase bravery is brave, though a coward. Money is not exchanged for a particular Quality, a particular thing, or a specific human faculty, but for the whole objective world of man and nature. Thus, from the standpoint of its possessor, it exchanges every quality and object for every other, even though they are contradictory. It is the fraternization of incompatibles; it forces contraries to embrace.

Let us assume man to be man, and his relation to the world to be a human one. Then love can only be exchanged for love, trust for trust, etc. If you wish to enjoy art you must be an artistically cultivated person; if you wish to influence other people you must be a person who really has a stimulating and encouraging effect upon others. Every one of your relations to man and to nature must be a specific expression, corresponding to the object of your will, of your real individual life. If you love without evoking love in return, i.e., if you are not able, by the manifestation of yourself as a loving person, to make yourself a beloved person, then your love is impotent and a misfortune.

I Hate the Poor

Kenneth PACHEN

from The Journal of Albion Moonlight (New Dimensions)

Until all men unite in hating the poor, there can be no new society. Stalin loves the poor—without them he could not exist.

The revolutions of the future must be directed not against the rich but against the poor. To be poor means to be blind, demoralised, debased. The poor have been the slop pails of capitalism, repositories for all the filth and brutality of a filthy, brutal world. Do not liberate the poor: destroy them—and with them all the jackal-Stalins that feast on their hideous, shrunken bodies. How the Church and the false revolutionaries draw together: love the poor—for they are humble. I say hate the poor for the humility which keeps their faces pressed into the mud. The poor are the product of a false and cruel society; but they are also the cornerstone of that society. Lift them to the stars; tell them to walk proudly on this earth: the cathedrals and broad roads were made by the labor of their hands; it is the duty of all true revolutionists not only to restore these things into their hands but also—and this is the key—to put them into their heads. Empty stomachs, empty heads: fill both with good food. Don’t shove Peter the Great back into their throats.

Letter from Chicago!

Bernard MARSZALEK

...i wrote a leaflet in honor of barry bondhus a minnesota youth who took two buckets of shit into his draft board office and dumped them into six file drawers. I hope to pass these out at Dick Clark’s World Fair of Youth being held for ten days at the amphitheatre and which will present 10 r’n’r groups, mod clothes exhibits, youth culture generally—it is being billed throughout the Midwest—a real blowout! But very conservative—several of us plan to change that. we still get suburban kids in to talk and i am beginning to come up with nice variations on disruptive activity that they can pull off.

what generates me at present is the altogether exquisite future that i see...wait till you get back; the climate is changing,here at a surprising rate; the acceleration is simply fantastic. everybody is flipping out.

another thing i am working on is a ball for may, probably outdoors, maybe at the tap root after we get chased off open lots. with several rock bands, blues, etc. several anarchists are interested, but i may have to do all the work, ecch.

there is a group here from the western suburbs called the shadows of night have they been heard of in england?

bruce elwell is hoping to start a theater of provocation in phillie... what i am DOING is getting high and higher on one little realization—that i have one task alone and that is to bring out the most delicate outrage in myself, explode the hair follicles whee...

...i can think of only lovely destructive stuff, like painting ourselves blue & walking on water. these scandals...must be spontaneous. i’ll talk to you when you are both back in this land of the brave & home of the free, or is it the other way around, i never could get it straight...may day...i’ll send you a letter from prison.

Lobster

by Benjamin PERET

The aigrettes of your voice spurt out from the burning bush of your lips

where the Chevalier de la Barre would be pleased to decay

The hawks of your gaze fishing thoughtlessly all the sardines of my head

Your breath of wild thoughts

reflecting from the ceiling on my feet

running through me from all sides

follow me and precede me

lull me to sleep and awaken me

throw me from the window to make me come up in the lift

and conversely

Solidarity Bookshop

...the only radical libertarian bookshop in the United States, run by members of the Industrial Workers of the World for the purpose of disseminating revolutionary literature to the widest possible readership. The following list is a brief selection of available material.

SOLIDARITY BOOKSHOP Annotated Catalogue of Radical Books In Print $.50 3/6d

53 Pages; sections on anarchism, socialism, surrealism, etc.

Mods, Rockers & the Revolution (Rebel Worker Pamphlet no. 1) $.15 6d

Collection of articles on the youth revolt

Blackout! (Rebel Worker Pamphlet no. 2) $.15 6d

24 hours of BLACK ANARCHY in New York

Revolutionary Consciousness (Rebel Worker Pamphlet no. 3) $.15 6d

Collection of articles aimed at collective consciousness expansion by Jim Evrard, Bruce Elwell, G. Bachelard (Forthcoming: to be published June 1, 1966)

Surrealism & Revolution (Rebel Worker Pamphlet no, 4) $.35 1/9d

Anthology of surrealist writing (ready July 1966)

Sabotage Anthology (Rebel Worker pamphlet no. 5) $.50 3/6d

The only anthology of articles on sabotage, including classics of the past and articles by younger revolutionaries in and out of the IWW today (ready August 1966)

IWW Publications

IWW Songs: To Fan the Flames of Discontent $.40 3/-

The famous Little Red Song-Book of the rebel band of labor; songs by Joe Hill, T-Bone Slim and others

The IWW: Its First Fifty Years by Fred Thompson, paperback $2.00 16/- cloth $3.00 24/-

Summary of Wobbly history

Books and Pamphlets of Other Publishers

Hungary ’56 by Andy Anderson (Solidarity) $.75 2/6d

The first proletarian revolution in a modern, fully-industrielized, bureaucratic country

Vietnam (Solidarity) $.15 6d

Background outline of the current crisis: “The only solution is world revolution.”

Eros and Civilization by Herbert Marcuse paper $1.25 10/-

Revolutionary implications of psychoanalysis

Nadja by André Breton $1.95 16/-

One of the greatest surrealist works (English trans.)

K.C.C. Versus the Homeless. The King Hill Campaign (Solidarity & Socialist Action) 44 p. illus. $.30 1/6d

The epic struggle of homeless of King Hill, providing a blueprint for future struggles against bureaucracies in local government.

Add 4% sales tax & postage. SOLIDARITY BOOKSHOP, 1947 N. Larrabee, Chicago

Shapes of Things

from the Minneapolis Star, February 25, 1966

Barry Bondhus a 20-year-old Big Lake youth was being held in Hennepin County Jail under $10,000 bond today on a charge that he dumped two buckets of human excrement into the files of the Sherburne County draft board at Elk River.

The arrest climaxed a series of difficulties he and his father have had with the draft board. The elder Bondhus said he has told the Board repeatedly that he is opposed to any of his sons serving in the Armed Forces. “If you draft Barry I have nothing to look forward to for the next 24 years but flag-draped caskets,” he said.

Barry is the second oldest of 10 Bondhus boys. After a board hearing February 15 the youth was classified 1-A and ordered to take a pre-induction physical examination in Minneapolis. The FBI said the youth refused to cooperate.

Wednesday, the complaint charged, the young Bondhus walked into the board’s office and dumped the substance into six draft board file cases. His draft board status is still pending.

The Anarchists wish to express their collective support for Barry Bondhus’ noble and appropriate response to the most obscene attempts by the State’s flunkies to enslave and possibly murder him. Barry has renewed our faith in mankind and for that we must thank him; but more, we must develop in ourselves, and of course others, the same altogether exquisite outrage which moved him to so poetically reveal his profound humanity. Along with wheelbarrows of desire, buckets of shit will stop the War in Vietnam.