Rasmus Hästbacka

How Can Syndicalism Grow?

Notes From Sweden

Successful examples and personal conversations

How can we promote organizing?

Courses during paid working hours

A labor union can either invest time, effort and resources into growing or shrink and disappear. Below, Rasmus Hästbacka of the Swedish SAC discusses forward-looking investments, based on current experiments in the country. The article has been translated from the Swedish magazine Syndikalisten #2/2025 and adapted for a wider audience.

Syndicalism emerged as a global movement in the 1800s. At the turn of the century, it was primarily syndicalist unions – not so called “labor parties” – that rallied workers around the world.

But in time, syndicalist unions were eliminated – by corporatist alliances (between State, Capital and servile unions), by the competition from “labor parties” and, not to forget, by brutal repression from totalitarian and liberal regimes. The last great flame of syndicalism was extinguished in the Spanish Revolution of 1936–39.

After the Second World War, the Central Organization of Workers in Sweden (SAC) was one of the few surviving syndicalist unions. SAC has shrunk from over 30 thousand members in the 1930s to just over 3 thousand today. In 1935, SAC consisted of 726 Local chapters (LS). Today there are only 20 Locals.

Three questions

After more than 20 years as an active member, I want to give my best tips for growing. However, it is not enough to ask: How can we increase the number of members? We must also ask How do we become more active members? and How do we increase our power in the workplace? It is through the power in workplaces that we can change society and ultimately abolish capitalism.

My answer to all three questions is: invest in workplace organizing! By workplace organizing (or just organizing), I mean that workers build and use their collective strength. Organizing is not the same as recruiting members, but organizing can promote recruitment. Organizing can also generate more and more engaged workers, which in turn renders more power in the workplace.

Successful examples and personal conversations

Historically, there are two types of activities that have made Swedish syndicalism grow, as far as I know. One type is, as said, workplace organizing. The other type is negotiations for migrant workers, which the Stockholm Local of SAC has demonstrated in recent years.

In Sweden, migrants are to a large extent subject to brutal and criminal employers. These employers are constantly violating laws and collective agreements. Union disputes over individual grievances often yield good results. This attracts even more migrants to the Stockholm Local of SAC.

However, organizing and negotiations do not automatically render more members. We have to boast of our successful examples. This can be done on the internet and cultural events, in the streets and squares, but mainly in workplaces – especially through personal conversations. The most important act of recruitment is probably that syndicalists ask co-workers: Aren’t you gonna join our union?

Here, I will not dive into the negotiations of the Stockholm Local. Instead, I will take a broader approach to organizing.

The art of organizing

Before I suggest how we can boost organizing and recruitment, I want to be clear about what organizing means. Organizing can be said to consist of three dimensions: 1) building a formal organization, 2) developing a union movement, and 3) mobilizing collective struggle and bargaining.

The formal organization can be a syndicalist section in the workplace, a syndicate in a particular industry or a Local (LS) that crosses all industries. The section is a local job branch. Many sections in the same industry form a syndicate i.e. an industrial branch. LS encompasses all sections and industrial branches in an area.

Furthermore, it’s possible to formalize a cross-union group. By this I mean a group of co-workers who meet regularly regardless of their union affiliations. If the group adopts bylaws and elects a board, the group becomes a union under Swedish law.

The second dimension of organizing – to develop a movement on the job – is about cultivating community and activity among workers. The third dimension – to mobilize – means that workers exert collective pressure on their employer for collective demands. Pressure includes not only strikes but a rich flora of methods.

An organizing method

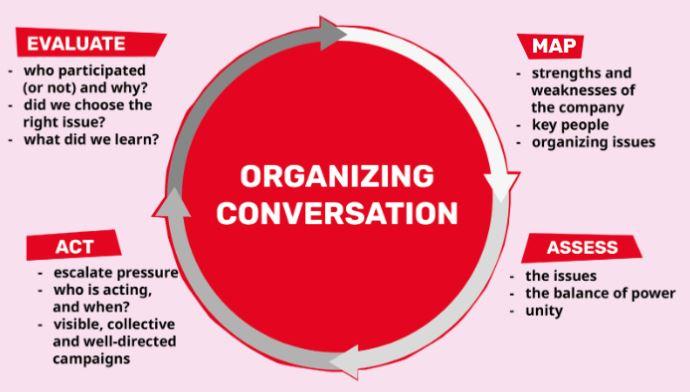

In SAC’s courses, members learn a method in four phases. The common thread through all phases is one-on-one conversations i.e. talking and above all listening to co-workers. The method is inspired by the Labor Notes book Secrets of a Successful Organizer. In SAC’s courses, the method is illustrated as an organizing wheel.

The first phase of the wheel is to map the workplace. Then organizers look for concrete issues to rally co-workers around. The second phase is to assess which issue is best to start with. It’s about choosing the issue that has the greatest potential to push the frontline forward.

The second phase is also about assessing what is called the balance of pressure or balance of power. The central question is: How hard do workers have to push the employer for their demands to be accepted?

In the second or no later than the third phase, an action plan is made. The plan needs to be anchored among as many employees as possible. The plan must state who does what and in what order. The third phase is to put the action plan into practice. In the fourth phase, the struggle and results are evaluated.

When workers have finished the fourth phase, they start the next turn of the wheel. They find new issues to gather around or push the same issues even further. In each phase, good opportunities to recruit more members can arise.

As said, this method is inspired by a Labor Notes handbook. In addition, SAC has produced short colorful guides to organizing here.

How can we promote organizing?

Now I will describe how our union can operate in places where there are a lot of sections and industrial branches linked to the Local (LS). Then I will suggest what can be done when LS is the primary meeting point in the locality.

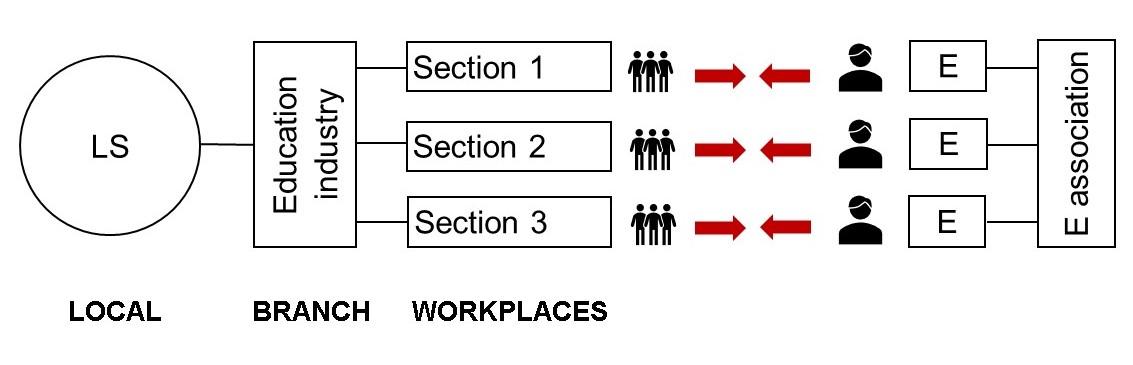

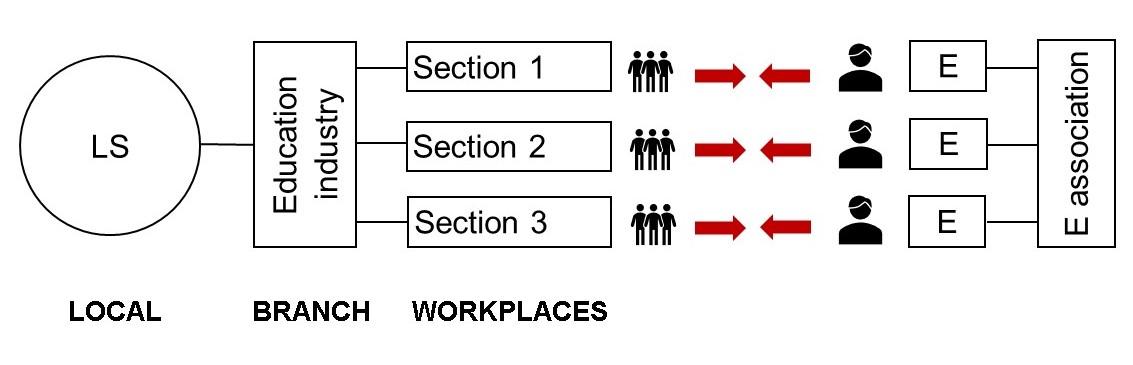

Our ambition as syndicalists is that members should belong to a section at work. Our ambition is also that all sections should cooperate through industrial branches, while LS coordinates all branches. This can be illustrated as the next image.

You see an LS, an industrial branch, sections and the members versus employers and their associations. I have chosen a branch in the education industry as an example. The idea is to build a united front in each industry, while LS functions as a platform for solidarity across industries. The industrial branch of education can then support branches in other industries and vice versa, for example through solidarity strikes.

At present, this is not the state of our union. Instead, we have some sections, but often without industrial branches, and some industrial branches, but often without sections. In several localities, only LS exists. So, how can members benefit from LS? And how can members benefit from starting an industrial branch without sections?

LS promotes organizing

Activities in LS can suitably revolve around the organizing wheel. LS can appoint an education committee or a person on the local board who arranges courses about organizing. At the LS member meetings, anyone who is keen to organize their workplace and recruit colleagues can take on the role of organizer.

At regular meetings, members can share how far they have come in the organizing wheel and get help moving to the next phase. If members are unable to attend physical meetings, it is possible to arrange digital meetings.

If LS meetings have little time to deal with the participants’ workplaces, it might be good to shorten the agenda. Purely individual grievances can be delegated to the LS board or a special bargaining committee. By “purely individual grievances” I mean cases which co-workers can’t be rallied around. It is also possible to remove points from the agenda that aren’t related to workplaces.

Organizing tutors

The task of LS is to enhance the forming of sections, cross-union groups and industrial branches. To succeed, it is important to have what we call organizing tutors or just tutors. They are elected to positions of trust to support organizers in their workplaces. An older term for tutor is the word LS organizer.

If organizers and tutors find it difficult to keep up with their assignments, during working hours or in their spare time, it’s important that the union sets aside money to pay them. Organizers and tutors can, for example, work with union issues one day a week and do their regular jobs four days a week. Paid comrades should not serve passive members, primarily, but increase the number of active members. Paid work should enhance members’ non-paid engagement.

If it’s difficult to find motivated organizers and tutors, LS can try to pay a part-time nomination committee that telephones the membership. A District of SAC, that is a group of LS, can also invest in joint tutors.

Courses during paid working hours

Another investment is to offer members courses during paid working hours, i.e. members take one or more days off and the union compensates them for lost income. Another way to promote active and knowledgeable members is to make the union introduction course mandatory. LS annual meeting can decide that everyone who wants union support at work should take the basic course.

If we are to organize successfully, we might be forced to prioritize pretty hard. It’s about directing LS limited resources to certain workplaces or a certain industry for a period of time. For driven syndicalists, it’s important to look for good organizing opportunities. Such occasions arise in meetings with other members but also through outreach activities addressing non-members.

Industrial branches boost organizing

In an industrial branch that has not yet formed sections, the activities can likewise revolve around the organizing wheel. At meetings, members can help each other to map their workplaces and find the best organizing issues, assess the pressure needed to win, make action plans, act collectively and evaluate.

The branch then becomes a forum for anyone who wants to start sections and cross-union groups at their own jobs or support other members who want to do so. The branch also becomes a forum for anyone who wants to recruit more members.

Build sections

In order for the industrial branch to succeed in building sections, it may be wise not to give the branch a mandate to handle purely individual grievances. If individual grievances arise, it can be handled by the negotiators in LS. If LS solves individual problems, then the industrial branch can focus on organizing to solve collective problems. Thus, the branch can also build sections.

These are not sacred principles, but it’s a rule of thumb based on solid experience. If industrial branches pursue individual grievances, it’s easy to spend all meeting time on it. Even if a branch has several paid representatives, it’s easy for the representatives’ time to be consumed by individual cases. A general tip is therefore not to give the industrial branch a mandate to pursue individual cases.

As sections are formed within the industrial branch, the sections can bargain for each workplace. Then the industrial branch can be given a mandate to bargain on issues that affect several workplaces. In this way, each section can use its collective strength when the section bargains, while the branch can use the collective strength that comes from several sections cooperating against the employer side.

Recruiting by negotiating

Another way of looking at industrial branches is – on the contrary – to give the branch a mandate to pursue individual cases as a strategy for recruiting members. The branch of construction workers within the Stockholm Local has shown that it’s possible (at least possible to recruit many migrants). Our comrades in Stockholm have also become adept at so-called extraction blockades in the form of protests outside workplaces. It remains to be seen whether the ongoing recruitment in Stockholm leads to more organizing inside workplaces.

How can SAC encourage organizing?

SAC is primarily based on local non-paid work. To some extent, we pay union officials for a limited time. All paid members receive the same pay at worker wage level. Paid members do not have the authority to make crucial decisions within SAC. They instead implement decisions made by non-paid members. This is a barrier against union bureaucracy and tycoons.

We, who are paid officials at the central level, have the task of supporting all local organizing tutors. We offer all LS, industrial branches and sections resources in the form of training, advice, digital tools, written material and money.

However, central officials cannot take over the local union business and run it on behalf of sections, industrial branches and LS. We can encourage self-organization. Helping people to self-organize is at the heart of our support.

The best recruiter of new members is probably not me, as a central official, but you as a local organizer.

Rasmus Hästbacka

Member of the Umeå Local of SAC

Central coordinator of SAC

More articles by Hästbacka here