Proletarios Revolucionarios

The Self-Abolition of the Proletariat As the End of the Capitalist World

(or why the current revolt doesn’t transform into revolution)

The fundamental contradiction of the current proletarian revolt

The self-alienation and self-destruction of the proletariat as a class of Capital

A revolutionary “pessimistic” postscript in times of coronavirus

1. Amadeo Bordiga (Activism — Italy, 1952)

2. Camatte — Collu (On Organization — France-Italy, 1972)

3. Francesco Santini (Apocalypse and Survival Italy, 1994)

10.2 Two opposed points of view on organization.

16. The activity of the Centro d’iniziativa Luca Rossi

5. Gilles Dauvé (Militancy in the 21st Century — France, 2014)

The self-abolition of the proletariat as the end of the capitalist world (or why the current revolt doesn’t transform into revolution)

“Exploitation, which is necessary to sustain the economy, has in the generalized installation of capital, managed historically to overcome the attacks of the proletariat, since they have never put its central components into question” […]

If it were but merely a question of explaining the facts in a very pedagogical way, the day after tomorrow the old world would be left in the dust, but this is not so, the exploited feel comfortable in their chains because they are entrapped in the mercantile social relations that hide their exploitation under the veil of democratic reconciliation or of nihilistic resignation, two poles of the same ideological center.”

— Anarquia & Communismo n.11

Santiago, Chile Winter 2018

“Yet at the same time, the proletariat only exists when it becomes conscious of its condition and struggles for its liberation, that is, its self-abolition, by attacking the social relations and institutions that keep it dominated and through the affirmation of its truly human interests, neither defined nor mediated by mercantile necessities”

— Ya No Hay Vuelta Atrás (Now There’s No Turning Back) n.2

Santiago, Chile February 2020

The fundamental contradiction of the current proletarian revolt

The revolt is breaking out all over the world, but all over the world the revolution is missing. Why? What follows is a tentative but forceful response.

The current-day reason is that this society of classes is coming out of a historical counterrevolutionary period (since approximately the 1980’s) and entering a historical period of ascension and intensification of the worldwide proletarian struggle against worldwide Capital-State (2008–2013 and 2019–202?). Which, at the same time, recently is starting to alter the correlation of forces and the conditions for a possible revolutionary situation, in view of the fact that the proletarian revolt has caused the bourgeoisie and their governments to tremble, but it still hasn’t defeated them nor sent them to the dustbin of history. As the comrades of Grupo Barbaria say, this is a “hinge period” which must be seen not as a photograph but as a film that contains flows (revolts), and ebbs (returns to normalcy), new flows and a open finale. A historical period which transits between the counterrevolution and a possible revolutionary situation at a global level; for which, nevertheless, there is still a long way to go.

The structural reason, or the one in the backdrop, is that the proletariat is still not a revolutionary class, despite the fact that today the capitalist crisis is more widespread and serious than ever before, and that the current global wave of revolts of the exploited and oppressed is a embryo and a milestone heading forward towards the global revolt, or at least its necessity and possibility. With a greater or lesser grade of organizational autonomy and of street violence, the proletarian class today is fighting against the capitalist order almost everywhere, but this is not sufficient: in the end, the proletariat is revolutionary or it is nothing, and it’s only revolutionary when it struggles, not for “a life that is just and dignified” as the working class, but to cease to be it. Yes, the proletariat is only revolutionary when it struggles to cease being the proletariat, that is, when it fights for its self-abolition. Of this there are certain symptoms and elements in some current struggles (e.g. struggles not for more work and more State but for another life, although they appear to be “suicidal” struggles) but still there’s a long way to go, because in their majority the proletarians continue to reproduce themselves as the class of labor and, therefore, as the class of Capital, and they continue to negotiate with the State about their demands in that reproduction. At the moment, then, the working class flows and ebbs between being an exploited class and being a revolutionary class. This is the fundamental contradiction, still unresolved, of the proletarian revolt today and, therefore, the principal reason for which it doesn’t transform into social revolution.

At the same time this happens because, in this era of real and total subsumption (integration and subordination) of work and life into Capital, Capital and the proletariat reciprocally imply each other — as the comrades of Endnotes say, — they mutually reproduce “24/7,” sometimes they identify with each other and other times they are in direct confrontation. A class relation in which, of course, the proletarian social pole is that which suffers all this human alienation as an exploited and oppressed class, and therefore once and awhile it rebels against such a condition. To which the Capital-State responds with repression and, above all, with co-opting and recuperation of the proletarian struggles into its logics, mechanisms, institutions, ideologies and discourses. Because if it doesn’t do so, it would seriously compromise its own existence. Like so then, from the point of view of the revolutionary and dialectical materialist, in the current historical cycle of class struggle the abolition of Capital necessarily implies the abolition of the proletariat and vice-versa.

Indeed, because in the end it’s not a matter of taking pride in being a proletarian and fighting for a “proletarian society,” and even less for a “proletarian State.” Alienation can’t be destroyed through alienated means, that’s to say with the arms of the system itself (as it is believed by the partisans of the “transition period,” meaning the so-called “socialism” of State capitalism, whatever the “path” may be), since that is “giving more power to Power.” On the contrary, it’s a matter of assuming the fact of being a proletarian as a condition that is socially and historically imposed, as the modern slavery from which one must liberate themself collectively and radically. It’s a matter of ceasing to be an exploited and oppressed class once and for all, eliminating the conditions that make the existence of social classes possible. Given that the proletariat condenses all forms of exploitation and oppression within itself, at the same time as all forms of resistance and of radical alternative, Capital, the State and all forms of exploitation and oppression would be abolished (sex/gender, “race,” nationality, etc.) This is the social revolution. And without a doubt this will not be a magical occurrence that happens over night in a pure and perfect manner, but a historical and contradictory process which nevertheless will have this consistent foundation or will not be.

Yet at the moment that is not what’s happening because, in spite of being in revolt in many countries, the proletariat in their majority continue to struggle to reproduce their “life” as the working class and not to put an end to their slavery, waged and citizenized. (I say in their majority, because there also exist proletarian minorities that agitate against work, the class society and the State, but that unfortunately don’t have a greater social impact.)

And they don’t do it just because of ideological alienation or “lack of class consciousness,” but because of the material necessity of survival: selling their labor force in the current precarious conditions and at whatever price in order to be able to cover their basic needs, trying to valorize their commodity-labor power in the work market as much formal as informal (or in the market of goods and services, in the case of self-management and barter), to struggle to subsume their life even more to Capital, reproduce and bear its social relations and its forms of living. The capitalist class relationship is in crisis, but it remains standing. The working class today is more precarious and miserable than ever before, but it continues to be a working class.

If indeed Capital can no longer maintain so much surplus or excess population which its own historical development has produced all over the world, but rather it gets rid of them by means of wars, pandemics, famines, etc., just as it also tends to generate new class conflicts, principally on part of the workers against the increase in exploitation and the pauperization or the so-called “austerity measures” taken as much by the left and the right; at the same time, the capitalist counterrevolution has still not been defeated by the proletariat on the socioeconomic and everyday terrain, and therefore, not on the political and organizational terrain, despite the ideological illusions that the different leftists create in this respect.

For example currently in Chile, a country in which, on one hand, despite the community soup kitchens and other practices of solidarity between proletarians, the revolt doesn’t provide a livelihood, or not for a long awhile. The majority of the people have to work (formally and informally) in order to eat, pay the rent, education, health care, basic services, telephone and internet, etc.; that’s to say, they must reproduce the capitalist relationships of production, circulation and consumption.

And on the other hand, in spite of the existence of the autonomous territorial assemblies, their major demand is the “constituent assembly”; meaning that, instead of taking power over their own life in order to change it radically and in every aspect, the majority of our class would again delegate it to the bourgeois-democratic State. But above all, because in their majority the proletarians continue reproducing the capitalist relationships of alienation, oppression, exploitation, competition and atomization amongst themselves, including in the the assemblies, the barricades and the territorial recuperations. And although the revolt in Chile is the most advanced at an international level at the moment, it is not therefore “the revolution to commence” as the comrades of the blog “Vamos Hacia la Vida” say, but rather it is a revolt that is being defeated by its own limits and obstacles, regardless of the organizational autonomy and the street violence which still manifests in it. As the comrades of the Círculo de Comunistas Esotéricos say, “The revolution has been postponed, but the larval possibility of assuming it has been implanted. It’s necessary to continue nourishing its possibilities as one waters a plant, as one suckles an infant, as bonds of affection are built: constantly, daily. The battle in these moments has been lost, but only partially. There are inroads that are necessary to maintain. Just as there are setbacks that need to be evaluated” And as another comrade from there, of the blog “Antiforma” says, paraphrasing Vaneigem: “those that speak of revolution and class struggle without referring to the destruction of the social and biopsychic fabric that could sustain a decisive change, speak with a corpse in their mouth.” Nevertheless, whatever happens in the next months in this country (especially , after the plebiscite which was announced for April 2020 but temporarily suspended due to the coronavirus), it will be a milestone in the transition — or not — of a possibly revolutionary historical period on a global level, which without a doubt leaves revolutionaries everywhere with multiple and valuable lessons.

For such reasons the thing is that, in this era and all over the world, the proletariat oscillates between being a class which is exploited and oppressed by Capital-State and being a class that is revolutionary or self-abolishing. It fluctuates between the one and the other, with or without consciousness of what it is doing and what it can do. This is — and it’s worth reiterating — the fundamental ambiguity, paradox or contradiction of the current day proletarian revolt that is still unresolved , and therefore, the principal reason for which it doesn’t transform into a social revolution.

Indeed, the revolt is not a revolution. The intermittent re-emergence of the worldwide proletariat, and its autonomous and violent actions against the forces of repression (of which spectacle and illusion are also made, e.g. the romanticizing of “the front line”), are not a revolution. But “the socialist transition State” and “rank-and-file workers’ self management” aren’t revolution either (they never were). The key to the social revolution is the self-abolition of the proletariat, which goes hand-in-hand with the abolition of value, because these are the roots or the foundations of capitalism, understood as the social dictatorship of value valorizing itself at the cost of a proletarianized humanity and of nature.

The self-alienation and self-destruction of the proletariat as a class of Capital

On the contrary, when they don’t fight against the capitalist conditionsand class relationships, when they don’t fight in an autonomous and conscious way to produce the conditions and the weapons (practical and theoretical) of their own liberation, the proletariat is a class of Capital and for Capital, because it is Capital that produces and reproduces it daily and in every sense, as much objectively or materially as subjectively and spiritually. Not only producing and reproducing economic value and surplus value, but also cultural value and surplus value, ideological and psychological — that is, producing and reproducing human alienation in all its levels and forms, upon the basis of the the fundamental and transversal alienation of the capitalist society: commodity fetishism, meaning the objectification, commodification and monetary valorization of human relations. — Not only by means of wage slavery and voluntary servitude — that is, being a citizenry disciplined by work/consumption and fragmented into thousands of particular identities; — but, above all, when the proletarians don’t recognize or assume themselves and among themselves to be as such, when they disregard and isolate themselves and neither act in solidarity nor mutual aid, when they compete, cheat, snitch, defraud, exploit, dominate, violate in every possible form and even kill each other (in all of these, without a doubt the women, children, homosexuals, blacks and indigenous bear the brunt of it).

In summary, the problem is the reproduction of capitalist social relations and of power in everyday life, principally within the proletariat itself, not only because of how the proletarian men and women relate with the exploiting and ruling class, but because of how they relate amongst the oppressed themselves in order to reproduce themselves as such, being, as they are, the majority of the society. And the thing is that, throughout majority of historical time (there are exceptions: revolts and revolutions) and in every part of the world, the proletariat has passed it by self-alienating and self-destructing as humanity to the benefit of Capital (of commodity fetishism, of value, of the money-god for which they work) and of all the forms of exploitation/oppression that are subsumed within its mode of social production reproduction (patriarchy, racism, nationalism, etc.) instead of directing all the subversive aspect of their misery, rage, and violence against it; and above all, instead of fighting to reappropriate their own lives and live them in real freedom and community.

Now, as Marx said, a society doesn’t ever disappear before all of its productive forces and forms of living (and of dying) are developed, or before the material conditions for new and superior social relations there already exist at its bosom. Therefore, the bourgeois society will not disappear until the proletariat neither can nor want to live under the capitalist mode of production and of living, and therefore begin to produce for themselves, by need and by desire, anarchic and communist social relations and forms of living, which can only be developed freely and fully by means of the social revolution, in the heat of the class antagonism and the reproduction of daily life. It is there, in the real and practical social struggles where the proletarians do this, where the seed of revolution, of communism and anarchy, can be found.

As Endnotes and other comrades like Kurz explain well, the revolutions of the 19th and 20th centuries, despite their elements and tendencies of a communist and anarchic character (e.g. rejection of work and of the State, of mercantile exchange and of democracy) didn’t dynamite the roots and fundamental categories of capitalism, but rather they developed, modernized and spread them throughout the world from the opposition, not only through the counterrevolutionary (re)action of the worldwide bourgeoisie, but also thanks to the worker-union, peasant and popular movement and its leftist vanguards that took bourgeois state power or, in the absence of that, managed to make the state concede economic, political and social reforms in terms of welfare, development and nationalism. It’s needless to say here, but anyway just in case, what existed in Russia, China, Yugoslavia, Cuba, etc. was not communism but State capitalism with other administrators and other headings. For their part, the anarchist and autonomist experiences of self-management (from Barcelona in 1936 to Chiapas and Rojava today in the 21st century) didn’t manage to break away from and overcome the social and impersonal dictatorship of value, money, the commodity and work, and that’s to say capitalism, either.

In short, all the past revolutions failed to realize the fundamental objective of the communist revolution: the abolition of class society, beginning with the proletariat itself, which is the principal producer and product of capitalist social relations.

Today we know that, despite such revolutionary elements and tendencies, it wasn’t due to causes pertaining to the ideological-political — meaning program and party — and military — meaning arms and the use of violence — but rather quite precisely material and historical causes — namely: a transition from formal subsumption to the real subsumption of work into Capital, a surge and crisis of the workers’ movement as opposition to/developer of capitalism, new cycles of crisis/restructuring and of class struggles, — which determined that communism would not be realized in past eras and that it really hadn’t been possible yet until today or from now on to realize it. And this is not “to justify the leninist and stagist theory of statist and capitalist development of productive forces,” as a comrade of the ICG says. It’s “applying historical materialism to historical materialism itself,” as Korsch said; in this case, the historical materialist conception of communist revolution. Furthermore in the communizing perspective leninism is also openly criticized as a counterrevolutionary force, and communism is understood as a real global-historical movement that, due to the causes that have been mentioned, still has not been able to transform into a new society.

Then, how could it be possible — even inevitable — that the current historical and international cycle of capitalist crisis/restructuring and of class struggle could be pushing the proletariat towards the worldwide communist revolution, in the same time that it is pushing towards extinction? Because the technological progress of the multinational companies, with the aim of competing and obtaining more profits and power, has turned them in their majority into a superfluous or excess population (surplus proletariat) which becomes more and more difficult to guarantee under this system, not only the production of commodities and of surplus value, but the reproduction of their very life in every aspect. The contradiction of capital, sooner or later fatal, is that it almost completely devalues its principal source of value and of wealth: the collective labor force, the working class. The fact that today there exists so much technology (as to reduce human labor to the necessary minimum) and so many foods (as much to feed more than the existing world population), but at the same time there is neither as much work, nor money, nor stability, nor housing, nor uncontaminated environment, nor health, nor anything, for the majority of the population, creates malaise and social protest. In which the proletariat, which is so precaritized today, has fought not only for work and for another kind of government, or not only for more money, more things and better services, but also against the State-Capital, with or without consciousness that it had done so. Producing communities of struggle and of life not mediated by competition, money or authority, that’s to say where new social relations are experimented with that subvert the capitalist social relations — another world inside of and against the bowels of this world —, but that last only as long as such struggles last… like everything in these “liquid” and “diffused” times.

It’s no coincidence then, that this era of crisis and social revolts be, at the same time, the era of the labor reserve army or of the workers who are unemployed, underemployed and impoverished, composed in a considerable percentage by youth with higher education, internet access and “social networks,” and with experience in massive rebellions and even in insurrections and “communes.” But up until there and no more, because the revolt is not the revolution. Capitalism remains standing. And this, at the same time, is because the proletariat is the living contradiction which today fluctuates between self-alienation/self-destruction and self-emancipation/self-abolition through its revolts and returns to normality.

The revolution is the positive resolution of this movement in contradiction: the revolution is the radical self-suppression/self-overcoming of the proletariat and, therefore, of Capital, not because of ideology but because of concrete vital necessity, that is to say when the proletariat feels and assumes in social practice the necessity to produce communism and anarchy in order to live, no more and no less, Meanwhile, capitalism, with the plasticity which has always characterized it, will continue to dialectically recycle the assaults of the proletariat to its own favor. And its leftist organizations will continue reproducing Capital and the State, although they think and say the opposite (see below).

All of this — and not “the lack of a party” nor “the lack of a program” — is what materially and historically explains why the proletariat, despite being the social majority numerically, has still not destroyed once and for all this system of alienation, exploitation, misery and death which is ruled over by the bourgeoisie, who are numerically the social minority. This is the response to the question that many proletarians have made sometimes or often, above all in this era of real and total subsumption of humanity into Capital.

Indeed, the problem is not only the “perverse” bourgeoisie and the “damned” capitalist system, but that, through subsumption, the proletariat itself IS the capitalist system: let’s be realist and honest, our class is not, nor must it be seen as “victim,” “saint,” nor “heroine,” in this history: the majority of the time and all over the place it keeps on self-alienating and self-destructing as humanity, reproducing the capitalist relationships of exploitation and oppression. But also, as an exploited and oppressed class, the proletariat has been and can be the revolutionary class, not necessarily but potentially, depending on what it does or doesn’t do in the class struggle to negate and suppress its own current condition, to transform the capitalist social relations into communist social relations.

Because it’s humanly comprehensible and assertable that our class becomes fed-up and attacks such a subhuman condition of being an exploitable and disposable commodity-thing. Because, dialectically speaking, within its self-alienation pulsates the possibility of its self-abolition, given that the de-alienation runs the same route as the alienation (from the economic alienation to the religious and ideological alienation). Its self-abolition, then, necessarily implies its self-liberation (“the emancipation of the workers will be the task of the workers themselves” or it will not happen), and its self-liberation necessarily implies its radical self-critique as a class. Because the self-critique allows it to learn the lessons of its defeats for present and future battles; that’s to say, because self-critique is the key to self-liberation, just as the “revolution within the revolution” is the key to the revolution. and above all because, as Camatte said “currently, either the proletariat prefigures the communist society and realizes the [revolutionary] theory, or it continues to be what society already is.”

This includes and implicates principally its organizations, parties, movements, collectives, groupuscules, sects or “rackets” of the left (marxist-leninist and postmodern) and of the ultra-left (radical communists and anarchists), because these also reproduce the capitalist relations, logics, dynamics, practices and behaviors. Principally, by means of their multiform political and ego competition to be the self-proclaimed vanguard that takes power over the State “when the historical moment arrives,” for some, or that self-manages Capital “from below and to the left” for “everyone” in daily life, for “others.” It’s all the same, because all these different leftist organizations are, due to their practices and their relations, just another gear in this generalized mercantile society of atomization, competition, spectacle and ideology (ideology understood as the deformed consciousness of the reality that, as such a real factor, at the same time exerts a real deforming action, in the words of Debord). Products and agents of the ideological-political and identitarian market, these leftist organizations are the caricaturesque and miserable spectacle of the struggle for revolution… ad nauseam. They are capitalism with an “anticapitalist” appearance.

Above all in moments of post-revolt or of a return to normalcy, like for example the leftist organizations in Ecuador after the revolt of October 2019 (in which we participated spontaneously as thousands of proletarians “without a party”), or like what happened also in Brazil after the revolt of June 2013… and in general all over the world, before and after the current wave of revolts.

Still so, the problem is not only the reformist or left-wing of Capital and its multiple divisions and competitions. The problem isn’t per se the ideology or the organizations either. The problem is how the proletariat itself and its proletarian minorities reproduce capitalism in daily life, in practice, despite how their ideology and discourse say the opposite.

The self-abolition of the proletariat as the key to the communist revolution and communism as a real and contradictory movement

Nevertheless, the only way to combat, destroy and really overcome all this shit is the autonomous and revolutionary struggle of proletarianized humanity, including its radical minorities. As well as the everyday and anonymous forms of resistance and solidarity between the oppressed or the nobodies “without a party.” Indeed, it is in the dialectic contradiction itself where the possibility of revolution can be found, understood as a negation and overcoming of the negation. This contradiction really exists and it IS the proletariat: an exploited class and a revolutionary class. Because the same vital energy that reproduces this system of death can be used to combat it, destroy it and overcome it. Starting by questioning, revolutionizing, and abolishing itself and by extension all other social classes, towards the aim of reappropriating human life itself, in the heat of, and only in the heat of, the class struggle. Assuming in practice that the struggle against Capital necessarily implies the struggle against its class condition itself. That might sound “suicidal” but, on the contrary, it’s liberating from the chains of wage slavery and of all oppression and alienation. Because, as the comrade Federico Corriente says, “today there’s no other horizon than that of the catastrophic reproduction of Capital and the inevitable and uncertain leap “into the void” that is paramount for putting an end to it, that will happen through the assault of the proletariat against the contradictions of its own reproduction.”

In fact, the only power which must be of interest to proletarians — because they possess it, at least potentially — is the power to self-eliminate as such and to so eliminate the capitalist and statist class relationship. As the comrades of Les Amis du Potlach said, “the revolution will be proletarian for those that realize it and anti-proletarian through its content” That is what the historical and revolutionary materialist dialectic really consists of, no more and no less: in assuming that the proletariat and the class struggle are a fundamental or substantial part of Capital, with the aim of struggling to cease be so and thus — and only thus — to render the classes and such a “systematic dialectic” itself abolished. This, and not anything else, is the proletarian revolution, the communist revolution. Obviously assuming it and doing it (the concrete) is a million times more complicated than understanding it and saying it (the abstract). And in spite of the current proletarian revolts, there is still a long way to go towards that, for the reasons expressed in the first part of this work.

In the sense that it’s still necessary to pass through many more crisis, struggles, insurrections, civil wars, pandemics, tragedies, counterrevolutions and defeats so that the proletariat finally manages — or not — to assume that human and historical necessity for the revolution, to become conscious of their revolutionary power, to act as a revolutionary subject and to make the social revolution, the key of which — and it’s worth insisting upon — is the self-abolition of the proletariat (the bourgeoisie will no longer have someone to exploit and oppress), which is intrinsic to the abolition of value (human relations will return to being human, since they will no longer be mediated by commodity-things or by money), and the transformation of the capitalist and authoritarian social relations into communistic and anarchic ones in every aspect. Not because of any ideology or politics, but because it will be a material question of life or death, in account of the current capitalist catastrophe which, in the future, will be increasingly worse. All of this, in increasingly more accelerated and violent times.

Yes: abolishing the proletariat in order to abolish capitalism must be — and really has always been — the objective and the principal measure of the communist or communizing revolution, in practice and, therefore, in the theory and revolutionary strategy.

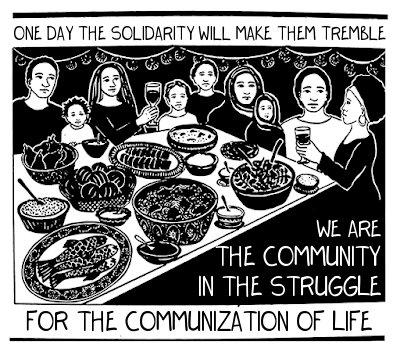

And meanwhile? And meanwhile, as it has been said: the autonomous and revolutionary struggle of proletarianized humanity, class antagonism and solidarity as much within counterrevolutionary everyday life (or in the non-revolutionary class struggle) as in the revolts and insurrections (or in the revolutionary class struggle), and above all the creation and development of new social relations and forms of life that break with and overcome the capitalist relations. Because it’s not only a matter of reappropriating and having clear the historical and invariant program of the communist revolution, and of fighting to impose such a program upon the class enemy by means of revolutionary power. It’s not just a matter of fighting for and making the revolution, it’s a matter of BEING the revolution. As the comrades of the Invisible Committee had said well, “the question is not only the struggle for communism, but the communism that is experienced in the revolution itself.” Therefore, the only “meanwhile” or the only “transition” to communism is communism itself, understood as a real and historical social movement that fights to destroy the capitalist society in order to transform into a new society without classes or States.

Indeed, because communism is not the utopia or the ideal to implant in an uncertain and indefinitely postponed future ad infinitum. As Marx said “communism is the real movement that abolishes the current state of things,” the premises of which can only be realized on the global-historical plane. It is the real movement of the proletariat tired of being so that destroys and overcomes the capitalist world, not because of ideology but because of material necessity and for freedom (freedom understood as consciousness acting out of necessity. Certainly, as Marx also said, a mass communist consciousness can only be produced through participation in a revolution or mass transformation of the material and spiritual conditions of existence.):

This movement has reemerged in the last decade and is once again “a spectre that haunts the world” and which frightens the worldwide bourgeoisie. Communism is “a corpse that doesn’t cease to be born” it is a real, living movement, that threatens the basis of the capitalist system itself, but which still hasn’t killed and buried it, due to its own limits and internal contradictions (see below).

But communism is not an ensemble of measures that are applied after the taking of power, as the leninists believe. It’s a movement that already exists, but not as a mode of production (there can’t be a communist island within capitalist society, as the self-managerialists believe), but as a tendency towards the community and the solidarity that can’t be realized in this society, the key of which lies precisely in the practices of solidarity and of community among proletarians while they struggle for their own lives against the capitalist system until being able to abolish it and overcome it, knowing or not what they are doing. Above all in situations of crisis and of extreme necessity:”In extrema necessitate, omnia sunt communia”: “in extreme necessity, everything is for everyone.”

Communism is not an ideal or a program to realize; it already exists, not as an established society, but as a seed, a task, an effort and a tension for preparing the new society. As Dauvé says “communism is the movement that tends towards abolishing the conditions of existence determined by wage labor, and it effectively abolishes them through revolution.”

Metaphorically speaking, communism is the fetus and the revolution is the birth of the new world. This is communization.

When it is real, the revolutionary movement is not pure and perfect but impure, imperfect, limited and contradictory. Hence, what really makes it revolutionary is assuming, sustaining and tensing that internal contradiction in order to eradicate and overcome it; concretely, eradicate and overcome the reproduction of the capitalist social relations at its heart along with the rest of the society. In other words, the revolutionary movement or the real community of struggle of the proletariat is the living contradiction and, at the same time, the conscious, voluntary and impassioned “tension” (in the sense that comrade Bonanno gives it) to eliminate and overcome this imposed contradiction; that is, by creating revolutionary situations, relations and subjectivities — communitarian and libertarian — that manage to confront, strike, debilitate, crack, destroy and overcome capitalism in the concrete life of concrete individuals, so much that it constitutes another form of being and living in this world.

One step forward in this real and anonymous proletarian movement is worth more than a dozen programs and “rackets” or groupuscles of the left and ultra-left.

Only then does the real community of struggle prefigure or anticipate the real human community. Only then exists the coherence between revolutionary ends and means (one of the lessons of the historical anarchist movement). And that is to make and to be the revolution understood as communization.

None of this is either pure or perfect, but it is impure, imperfect, limited, contradictory, as it was said: there exists a tension, rupture and leap or change more or less permanent — or rather intermittent — within it, as a real and living movement. In effect, the real anticapitalist movement is the one in which the deeds subvert and overcome the capitalist conditions of existence and its own internal contradictions determined by such conditions. Where direct action, the abolition of private property, solidarity, gratuity, horizontality in the taking of decisions that affect everyone’s lives, are facts and not only words and ideas. I’m thinking of Exarchia (Greece) and the Mapuche territories (Araucanía), just to mention a few current and concrete examples. There exist the seeds and the tendencies of communism and revolution today.

So, a period of communization instead of a “period of transition.” This means that communization will not occur overnight, nor through the existence of a mass class consciousness (incarnated and directed by “the party”) nor through the existence of many “self-managed communes” (capitalism with an assembleary and self-managed appearance), but by means of a process or a contradictory and historical-concrete cycle of capitalist crisis/restructuring and of real and international class struggle that, at the same time, is a result, critical balance and surpassing synthesis of all the past cycles of struggle (since the birth of capitalism up until then).

Concretely, the current historical cycle, in which the proletariat, at the same time that it is totally subsumed to Capital, resumes its class struggle against it and, therefore, against their own condition as an exploited and oppressed class, in order to so reappropriate their own lives. Which is inseparable, lastly, from the struggle to communize all the conditions and material and immaterial means of existence.

In effect “the communist production of communism,” as the comrades of Théorie Communiste say, can only be realized at the heart of the real class struggles and, more specifically, at the heart of the autonomous struggles of and within the proletariat itself in order to out a stop to the catastrophic capitalist progress in course and therefore defend nothing more and nothing less than Life, by material and concrete necessity, and also because of the acting and emergent consciousness of such a necessity. Tensing, breaking and overcoming its own limits as a class of and for Capital. Questioning, negating and overcoming their own condition as a social class determined and divided by work and money. Resisting, advancing and leaping from their defensive self-organization towards their positive self-abolition as such. Taking immediate communist measures to this effect.

Immediate communist measures? Yes, because the current historical-material conditions, these being the high level of capitalist progress and of catastrophe in every aspect of social life, as well as the existing communist practices in some current proletarian struggles, not only make it possible but urgent to take immediate communist measures. Furthermore, as Jappe says, this is the only revolutionary or “radical realism” that is possible today, while all kinds of reformism of the “period of socialist transition” type not only were, are, and will be counterrevolutionary by being capitalist and statist, but also because it’s objectively impossible in this era. In effect, given that the current crisis of Capital is the crisis of labor, of value and of the class relationship, the revolution not only must consist of abolishing private property, meaning expropriating from the bourgeoisie by force and communizing the means of production and the consumer goods: it must consist — and in reality it always has consisted — in abolishing wage labor, the division of labor, money, mercantile exchange, value, businesses; and, in turn, in generalizing the minimal necessary labor, the gratuity of things and the collective and individual making of decisions, in order to so abolish all the social classes and all forms of state power over the real community of freely associated individuals that must be formed in order to produce and reproduce their own lives according to their real human needs. As a banner recently unfurled on a balcony of an italian city says: “Work less. Everyone work. Produce what’s necessary. Redistribute everything.” All of this, in concrete local territories and with real international ties. Also, inseparable from that, are those communist measures that eliminate all forms of segmentation, privilege and oppression based upon sex/gender, “race” and nationality. And if it’s possible to speak and write about all that, it’s because there exist practices in some current anti-system revolts and movements that already prefigure or anticipate them as real seeds and tendencies.

A current and concrete example of an immediate communist measure; the looting of supermarkets in the south of Italy, one of the countries most afflicted by the “coronavirus crisis,” which was done by proletarians who are already in precarious situations and now desperate, given that, as they themselves say, “the problem is immediate, the children have to eat.” Why is it an immediate communist measure? Because, despite it not directly affecting the sphere of production (as on the other hand the recent wildcat strikes in the same country have indeed done), it eliminates by the deed the sacrosanct private property, the commodity, wage labor and money, and satisfies the common and basic needs of the proletarians and their families. The spontaneous, autonomous and anonymous networks of solidarity and mutual aid among proletarians, which have been created in these precise moments everywhere, are also a concrete communist practice. How can these kinds of measures be sustained over time an space? That’s another subject. On the other hand, it’s also possible to consider as an immediate communist measure the call for a “universal rent strike” (to not pay rent and to occupy empty homes for people that are homeless) from many countries of the world (Spain, France, Sweden, United Kingdom, USA, Canada, Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, etc.).

On the other hand, the other possible meanwhile is that the proletariat in their majority continue working (including police and military work, and that of “telework”), buying, consuming, contaminating, voting, studying, facebooking, tweeting, watching netflix, eating “junk food,” going out to party, listening to reggaetón and getting drunk on the weekends, drugging themselves to the veins, going to the bordello, to the stadium, to the concert and the tavern… or to the church, and being nationalist, xenophobic, macho and violent (including fascist) towards other proletarians but not towards the bourgeois and their uniformed guard-dogs; or looking for work and dying of hunger, from depression or of cancer; or going delinquent to later rot in jail; or going “crazy” to later rot in the asylum; or falling into social paranoia, consumerism and individualism in the supermarkets and everywhere else, when there are pandemic situations (e.g. coronavirus), health emergency, austerity measures and massive disinformation/idiocy; or — what seems to be the opposite but is not — joining up to be militants in the ranks of their left/ultra-left organizations, believing that they are “fighting for the revolution” and “being coherent” by that, when in reality they are only participating in capitalist political competition between proletarians, a competition that only differs in the form and level of violence from other non-political forms of fratricidal war (gangs, mafias, etc.) at the same time that such political sects have a similarity to religious sects in their dogmatic way of seeing the world and by treating their peers like sheep and soldiers for their war against “the enemy” and for “the cause.”

To sum it up, the other possible meanwhile is alienated survival and, in the long-term, suicide; that’s to say, that the proletariat continue self-alienating and self-destructing in a million ways to the point of becoming extinct as humanity, not before devastating the planet, clearly, under the yoke of the capitalist Leviathan (businesses and States).

Communism or extinction

Therefore, the current and inexorable dilemma for humanity is: communism or extinction, revolution or death. But the revolution doesn’t only take place at exceptional moments in history. The revolution itself is an eruptive and decisive exception in the history of the class struggle and the capitalist social normality. But it’s not a fate or destiny but a possibility. It’s not inevitable but rather it’s contingent: it can as much as can’t happen. It depends on what the proletariat does or doesn’t do in respect. Because capitalism will not die by itself or peacefully.

The revolution is not an occurrence which happens overnight, instilling paradise on Earth either, but rather it’s a historical process, concrete, contradictory and even chaotic, that contains flows and ebbs, advances and retreats, ruptures and leaps, times of stagancy and new leaps. It’s a process of social transformation of a radical and total character which has always been, and above all at these heights of history, necessary and urgent, because it’s the only way that proletarianized humanity — which is the majority of humanity — can cease to self-alienate and self-destruct as humans, and at the same time to cease to destroy non-human nature.

Yes: communization is the only revolutionary exit from the crisis of capitalism or, which is the same thing, the only radical solution for the civilizatorian crisis, because it’s the only way to guarantee the reproduction of Life, or as Flores Magón would say, for its “regeneration” or reinvention.

It’s necessary to produce, then, that exception or historical eruption that is the revolution, no more and no less than for vital necessity. It must be gestated and born. Communism is the fetus and the revolution is the birth of the new world. But, as it has already been said, this depends on what the proletariat does or doesn’t do in order to transform the current social conditions and their own life, their own collective being and the ecosystem.

In the case that our class doesn’t fight for the total revolution until the end, the counterrevolution will continue to reign and the capitalist or dystopian catastrophe in course (systematic economic crisis, cutting-edge technology/”artificial intelligence,” massive unemployment and poverty, devastation of nature/ecological crisis, pandemics, wars, suicides, etc.) will finally end up making us as a species extinct. Perhaps there are only a few generations left before that. And the countdown increasingly accelerates.

Therefore, the current worldwide capitalist crisis and the current worldwide wave of proletarian revolts constitute possibly the last historical chance to finally start the irrevocable process of the global communist revolution, of the abolition or the overcoming of the society of classes and fetishes… or to perish.

Exaggerated? Apocalyptic? We’re already living in the capitalist apocalypse that is the the current crisis of civilization! The dystopian future is now! Our historical cycle of crisis and struggles will possibly be the cycle of 2019–2049…

Communism or extinction!

The self-abolition of the proletariat is the end of the capitalist world!

Proletarians of the world: Let’s self-organize in order to cease to be proletarians!

A proletarian fed-up with being one

Quito, Ecuador

February-April, 2020

A revolutionary “pessimistic” postscript in times of coronavirus

“The outbreak of the new strain of coronavirus (COVID-19), which has wrought havoc in China since the end of last year, has surged over borders and impacted the rest of the world, and with it, the imminent economic crisis has but further advanced. The world economy is in full-on crisis, the administrators of power are pending on immense financial relief, the bourgeoisie are beginning to close factories and lay off employees using the lucky pretext of the “quarantine” as excuse. The disaster is immanent. Nevertheless, it’s important to know that the monetary losses don’t signify the fall of the capitalist system. Capitalism will seek at every moment to restructure itself on the basis of austerity measures imposed on proletarians in order to palliate all the catastrophic consequences that it will bring along with it. And this is due to the fact that the “blows” that capitalism has been dealt due to these phenomena are simply losses in its rate of profit, but those losses don’t at all change its structure or its essence, meaning the social relations that allow it to remain standing: the commodity, value, the market, exploitation and wage labor. In fact, it’s in these structures that capitalism most reaffirms its necessities: sacrificing millions of human beings to the favor of economic interests, making the polarization between classes sharpen and revealing more forcefully in what position the dominant class is to be found, who will use all the efforts in their reach in order to preserve this state of things.

[…]

The ever-more contradictions heightened contradictions of this mode of production (crisis, war, pandemics, environmental destruction, pauperization, militarization), which exasperate our conditions of survival, won’t clear the way either mechanically or messianically for the end of capitalism. Or better said, such conditions, although they will be fundamental, won’t suffice. Because for capitalism to reach its end, it’s imperative for there to be a social force, antagonistic and revolutionary that manages to direct the destructive and subversive character towards something completely different from what we know and experience now.

If we want it or not, we can’t let a question as important as the revolution to drift aimlessly, to leave it to luck. It’s necessary to experience the resolution of this problem on the basis of the organization of tasks that can go on to present themselves, that’s to say, the grouping for the appropriation and defense of the most immediate necessities (not paying debts, rent, or taxes), but also, the rupture from all the dreams and mirages that carry us to manage the save miseries behind another facade.

[…]

It’s not necessary to wait for the dystopia or the hollywoodesque scenes of apocalypse, because these are already materially manifesting in different parts of the globe, and in fact they greatly surpass any attempt at representation by cinematic fiction.

The current pandemic of COVID-19 is one more stage in the degradation to which this society of commodity production brings us.

A stage before which it is reaffirmed that the true future only hangs from two strings:

Communist revolution or to perish in the twilight!”

Contra la Contra n.3

Collapse of the capitalist system? A few notes on current events.

Mexico City

March 2020

On activism, theory, the individual and revolutionary organization. An imaginary debate between a few comrades

This text, composed for the most part of key fragments from texts by other historical and international comrades on the themes proposed, is the continuation or second part of my text “The self-abolition of the proleariat as the end of the capitalist world (or why the current revolt doesn’t transform into revolution,” and it’s a tentative and provisional response to the question “So what should we do then?”

1. Amadeo Bordiga (Activism — Italy, 1952)

[from: <libcom.org/library/activism-amadeo-bordiga>]

Activism is an illness of the workers movement that requires continuous treatment.

Activism always claims to possess the correct understanding of the circumstances of political struggle, and that it is “equal to the situation,” but it is incapable of engaging in a realistic evaluation of the relations of force, enormously exaggerating the possibilities of the subjective factors of the class struggle.

It is therefore natural that those affected by activism react to this criticism by accusing their adversaries of underestimating the subjective factors of the class struggle and of reducing historical determinism to that automatic mechanism which is also the target of the usual bourgeois critique of Marxism. That is why we said, in Point 2 of Part IV of our “Fundamental Theses of the Party”:

“… [t]he capitalist mode of production expands and prevails in all countries, under its technical and social aspects, in a more or less continuous way. The alternatives of the clashing class forces are instead connected to the events of the general historical struggle, to the contrast that already existed when bourgeoisie [began to] rule [over] the feudal and precapitalistic classes, and to the evolutionary political process of the two historical rival classes, bourgeoisie and proletariat; being such a process marked by victories and defeats, by errors of tactical and strategical method.”

This amounts to saying that we maintain that the stage of the resumption of the revolutionary workers movement does not coincide only with the impulses from the contradictions of the material, economic and social development of bourgeois society, which can experience periods of extremely serious crises, of violent conflicts, of political collapse, without the workers movement as a result being radicalized and adopting extreme revolutionary positions. That is, there is no automatic mechanism in the field of the relations between the capitalist economy and the revolutionary proletarian party. […]

The indefatigable and assiduous labor of defense waged on behalf of the doctrinal and critical patrimony of the movement, the everyday tasks of immunization of the movement against the poisons of revisionism, the systematic explanation, in the light of Marxism, of the most recent forms of organization of capitalist production, the unmasking of the attempts on the part of opportunism to present such “innovations” as anti-capitalist measures, etc., all of this is struggle, the struggle against the class enemy, the struggle to educate the revolutionary vanguard, it is, if you prefer, an active struggle that is nonetheless not activism. […]

The resumption of the revolutionary movement is still nowhere in sight because the bourgeoisie, putting into practice bold reforms in the organization of production and of the State (State Capitalism, totalitarianism, etc.), has delivered a shattering and disorienting blow, sowing doubt and confusion, not against the theoretical and critical foundations of Marxism, which remain intact and unaffected, but rather against the capacity of the proletarian vanguards to apply those Marxist principles precisely in the interpretation of the current stage of bourgeois development.

In such conditions of theoretical disorientation, is the labor of restoring Marxism against opportunist distortions merely a theoretical task?

No, it is the substantial and committed active struggle against the class enemy.

2. Camatte — Collu (On Organization — France-Italy, 1972)

[from: <marxists.org/archive/camatte/capcom/on-org.htm>]

At the present time the proletariat either prefigures communist society and realizes communist theory or it remains part of existing society. […]

Today, now that the apparent community-in-the-sky of politic constituted by parliaments and their parties has been effaced by capital’s development, the “organizations” that claim to be proletarian are simply gangs or cliques which, through the mediation of the state, play the same role as all the other groups that are directly in the service of capital. This is the groupuscule phase. In Marx’s time the supersession of the sects was to be found in the unity of the workers’ movement. Today, the parties, these groupuscules, manifest not merely a lack of unity but the absence of class struggle. They argue over the remains of the proletariat. They theorize about the proletariat in the immediate reality and oppose themselves to its movement. In this sense they realize the stabilization requirements of capital. The proletariat, therefore, instead of having to supersede them, needs to destroy them.

The critique of capital ought to be, therefore, a critique of the racket in all its forms, of capital as social organism; capital becomes the real life of the individual and his mode of being with others […] The theory which criticizes the racket cannot reproduce it. The consequence of this is refusal of all group life; it’s either this or the illusion of community.[…]

Today the party can only be the historic party. Any formal movement is the reproduction of this society, and the proletariat is essentially outside of it. A group can in no way pretend to realize community without taking the place of the proletariat, which alone can do it.[…]

The revolutionary must not identify himself with a group but recognize himself in a theory that does not depend on a group or on a review, because it is the expression of an existing class struggle. This is actually the correct sense in which anonymity is posed rather than as the negation of the individual (which capitalist society itself brings about). Accord, therefore, is around a work that is in process and needs to be developed. This is why theoretical knowledge and the desire for theoretical development are absolutely necessary if the professor-student relation — another form of the mind-matter, leader-mass contradiction — is not to be repeated and revive the practice of following.[…]

It is necessary to return to Marx’s attitude toward all groups in order to understand why the break with the gang practice ought to be made:

-

refuse to reconstitute a group, even an informal one (cf. The Marx-Engels correspondence, various works on the revolution of 1848, and pamphlets such as “The Great Men of Exile,” 1852).

-

maintain a network of personal contacts with people having realized (or in the process of doing so) the highest degree of theoretical knowledge: antifollowerism, antipedagogy; the party in its historical sense is not a school.

Marx’s activity was always that of revealing the real movement that leads to communism and of defending the gains of the proletariat in its struggle against capital. Hence, Marx’s position in 1871 in revealing the “impossible action” of the Paris Commune or declaring that the First International was not the child of either a theory or a sect. It is necessary to do the same now.[…]

It follows from this that it is also necessary to develop a critique of the Italian communist left’s conception of “program.” That this notion of “communist program” has never been sufficiently clarified is demonstrated by the fact that, at a certain point, the Martov-Lenin debate resurfaced at the heart of the left. The polemic was already the result of the fact that Marx’s conception of revolutionary theory had been destroyed, and it reflected a complete separation between the concepts of theory and practice. For the proletariat, in Marx’s sense, the class struggle is simultaneously production and radicalization of consciousness. The critique of capital expresses a consciousness already produced by the class struggle and anticipates its future. For Marx and Engels, proletarian movement = theory = communism.[…]

Actually, the problem of consciousness coming from the outside did not exist for Marx. [Kautsky-Lenin] There wasn’t any question of the development of militants, of activism or of academicism. Likewise, the problematic of the self-education of the masses, in the sense of the council communists (false disciples of R. Luxemburg and authentic disciples of pedagogic reformism) did not arise for Marx. R. Luxemburg’s theory of the class movement, which from the start of the struggle finds within itself the conditions for its radicalization, is closest to Marx’s position (cf. her position on the “creativity of the masses,” beyond its immediate existence).[…]

Once we had rejected the group method, to outline “concretely” how to be revolutionaries, our rejection of the small group could have been interpreted as a return to a more or less Stirnerian individualism. [and as “a new theory of consciousness coming from the outside through the detour of an elitist theory of the development of the revolutionary movement] As if the only guarantee from now on was going to be the subjectivity cultivated by each individual revolutionary! Not at all. It was necessary to publicly reject a certain perception of social reality and the practice connected with it, since they were a point of departure for the process of racketization. If we therefore withdrew totally from the groupuscule movement, it was to be able simultaneously to enter into liaison with other revolutionaries who had made an analogous break. Now there is a direct production of revolutionaries who supersede almost immediately the point we were at when we had to make our break. Thus, there is a potential “union” that would be considered if we were not to carry the break with the political point of view to the depths of our individual consciousnesses. Since the essence of politics is fundamentally representation, each group is forever trying to project an impressive image on the social screen. The groups are always explaining how they represent themselves in order to be recognized by certain people as the vanguard for representing others, the class. […]

All political representation is a screen and therefore an obstacle to a fusion of forces. […]

In the vast movement of rebellion against capital, revolutionaries are going to adopt a definite behavior — which will not be acquired all at once — compatible with the decisive and determinative struggle against capital.

We can preview the content of such an “organization.” It will combine the aspiration to human community and to individual affirmation, which is the distinguishing feature of the current revolutionary phase. It will aim toward the reconciliation of man with nature, the communist revolution being also a revolt of nature (i.e., against capital; moreover, it is only through a new relation with nature) that we will be able to survive, and avert the second of the two alternatives we face today: communism or the destruction of the human species.

In order to better understand this becoming organizational, so as to facilitate it without inhibiting whatever it may be, it is important to reject all old forms and to enter, without a priori principles, the vast movement of our liberation, which develops on a world scale. It is necessary to eliminate anything that could be an obstacle to the revolutionary movement. In given circumstances and in the course of specific actions, the revolutionary current will be structured and will structure itself not only passively, spontaneously, but by always directing the effort toward how to realize the true Gemeinwesen (human essence) and the social man, which implies the reconciliation of men with nature (Camatte, 1972).

3. Francesco Santini (Apocalypse and Survival Italy, 1994)

[from: <libcom.org/library/apocalypse-survival-reflections-giorgio-cesaranos-book-critica-dell%E2%80%99utopia-capitale-expe> — See also the pdf edition published by Malcontent Editions]

10.2 Two opposed points of view on organization.

In 1971 Comontism took shape and the group that had formed based on the positions of Invariance [the journal directed by Camatte] dissolved. It must be mentioned that both tendencies had diametrically opposed attitudes towards the “question of organization.” One of these attitudes was in fact that of Cesarano and a large part of the current. The idea of Comontism instead whimsically identified its own members (largely veterans of the similar Organizzazione Consigliare di Torino) with the historical party of the proletariat, or, even better, with the “human community.”

On this basis, it created an organization with branches in several Italian cities (see Maelström, No. 2), which erased any distinction between theoretical and practical activity, between public life and private life, between individual and organization. Comontism thus attempted to breathe life into a concrete communism, characterized by:

-

The collectivization of all resources for survival;

-

A “total” way of living together;

-

The constant practice of the “critique of everyday life” in order not to yield to the pressure imposed by society in the form of family, social milieu, legal relations, etc.

The immediatist illusion of the group caused it to overlook one fundamental fact: that between capitalism—that is, between personal relations dominated by valorization—and communism, there is a revolution that, according to Marx, serves among other things to “get rid of all the old shit.” For Comontism the Gemeinwesen [human community] had to be put into practice here and now: it was all about the passage to communism of twenty or thirty persons, communizing all relations all at once: this idea would lead inevitably and immediately to the production of an ideology: immediatism was rapidly followed by the elaboration of a whole set of “theoretical” corollaries.

In retrospect, we have to sympathize with Comontism: it was a group of courageous individuals who always stayed at their posts at the revolutionary front, bravely confronting harsh repression and fighting against various Maoist-workerist splinter groups that had specialized military structures crafted to ensure that the assemblies and demonstrations were conducted in a way that was acceptable to their father-master PCI (with the sole exception —besides, naturally, the Bordiguist groups that had already experienced the armed repression of the “extraparliamentary” Stalinists—of Potere Operaio, a group devoted to guerrilla tactics which, although it did not publicly defend the revolutionaries, was always opposed to […]the systematic calumnies of the left which had for several years been proclaiming that “situationists=fascists.” It is indisputable, however, that Comontism was a revolutionary group, which the Cronaca di un ballo mascherato justly cited as part of the radical communist current. Not in vain did it claim to have remained on the terrain of revolutionary practice, when so many other former Luddites had accepted the separation between the “militant” public life and private life, which soon led them to passive nihilism and, in many cases, to renounce the revolutionary option in favor of worldly success or simply a tranquil life. On the other hand, one cannot avoid criticizing the retreat of Comontism with respect to the level attained by Ludd. Comontist immediatism is nothing but a substitutionism of the proletariat carried to its logical extreme.

From this point of view, Comontism was an authentic model of ideology, based on an undeclared but easily recognizable hierarchy, which subjected its recruits to initiation tests and examinations of their radicality. The most disastrous aspect of Ludd, which we shall discuss in connection with Cesarano’s critique, became a systematically and relentlessly applied ideology. Among its ideological conclusions we find: the apology for crime (the only respected and recognized way to survive); the praise, not publicly proclaimed, but a constant feature within the group, for hard drugs as an instrument of destructuring and liberation from family and repressive relations; the sectarian attitude of superiority displayed towards every element external to the organization; the group’s hostility to the hard working, sheep-like proletariat, which was viewed as just as culpable as everyone else who was not part of the organization. All of this turned Comontism into a gang at war with all of humanity, and an uncritical follower of the criminal model. This is what we mean by “ideology”: the theorization of this practical attitude in fact prevented any critical procedure from assuming a material basis: they were dogmas embedded in the extremely coercive experience of the members of the group. This form of immediatism was certainly one of the reasons that prevented Cesarano from drawing practical conclusions, and which led him to lose himself in sterile abstractions.

However, behind this and other dead ends of Cesarano we find certain positions that are diametrically opposed to those of Comontism: the positions of Invariance.

Invariance had “resolved” the problem of organization by studying the measures employed by Marx to prevent the party from succumbing to bourgeois reformism during the period of counterrevolutionary retreat. This analysis was extremely partial, since it completely ignored all of Marx’s activity that was devoted to building the communist party, and distorted the revolutionary tradition by avoiding a critical examination of the purely political activity of Marx taken as a whole. This attitude was expressed in a text from 1969, published three years later by Invariance under the title, “On Organization,” signed by Camatte-Collu, which can be summarized as follows:

-

Under the real domination of capital every organization tends to be transformed into a Mafia or a sect;

-

Invariance avoided this danger by dissolving the embryonic group that had begun to form around the journal;

-

All organized groups are excluded a priori, because of the risk that they will be transformed into Mafias;

-

Relations between revolutionaries are only useful at the highest level of theory, which each individual can attain in a personal and independent way, or otherwise fall prey to followerism.

According to Camatte and Collu, the danger of individualism was of no account because the “production of revolutionaries” was already underway—in 1972: the extension of the revolutionary process was such that a network of interpersonal contacts at the “highest” level of theory was already guaranteed and was even evident.

Thus, Camatte and Collu expressed in the clearest way an error that was typical of the entire current and of Cesarano himself. In reality, a pre-revolutionary stage on an international level was not opening up in 1972 (despite the fact that the movement would continue to resist, although only in Italy), nor was an inexorable production of revolutionaries imminent (even Camatte and Collu would desert). Therefore, the disregard of individualism was nothing but an illusion. There was nothing glorious about dissolving the small group that was forming around the journal. This did nothing but accelerate what was already taking place: the dispersion of the sparse revolutionary forces that remained from 1968, forces which would not experience a resurgence (in France there were no more large-scale social uprisings, and in Italy the revolutionary current faced 1977 so weakened by individualism that it was incapable of undertaking any relevant interventions). In fact, individualism favored the dissolution of the revolutionary perspective: either because life in isolation produced a feeling of reduced self-esteem—which could only be escaped by comparing oneself with one’s peers—which prevented one from perceiving the movement and which generated discouragement and depression, the loss of one’s defenses against the invasion from “outside” and surrender to dominant tendencies; or because it disguised personalism and elitism, and served to enable one to get rid of those uncomfortable relations that could stand in the way of an opportunist reinsertion into bourgeois ideology. During the seventies and eighties the work of the liquidation of the organizational remnants (which were by then fragile and informal) and the unjustified fear of succumbing to politics, “workerism” or leftism, contributed the impulse to jump to the “other side of the barricade” for those exponents of the “elite” who had transformed theory into a fetish and who were mistrustful of the alleged danger of followerism (a danger that was actually imaginary and non-existent: in Italy no group or personality exercised any attraction or obtained passive followers such as the Situationist International had on the other side of the Alps. In France, in any event, Invariance never did so). We have been analyzing two views regarding organization that were typical of the seventies, which we can reject without any remorse, and above all without falling prey to any of the mystifications offered by the youngest elements. The first view, that of Comontism, is the model of the criminal gang-historical party-human community. Although respectable from a human point of view (like its current epigone, the French group, Os Cangaceiros), and although it was often interesting for the practical-organizational-lifestyle solutions that it proposed (the revolutionaries must live “as if” communism was already a fact and could thus face the terrible struggle for survival together, which was twice as hard for them), its vision was born from resentment: the proletariat is not revolutionary, so “we” (the tiny groups) are the proletariat; we are the now-realized human community. This led them to a dogmatic and ideological evaluation of their own sectarian activity and offered the most disastrous answers: the terroristic self-criticism imposed on every gesture and every word; the fetishism of coherence; the lurking possibility of political decline, caused above all by the spell cast by action, which led them to become a mere gang of loud-mouthed thugs. All of this was based on the totemic-fetishistic blackmail of “practice,” in the ideological scorn for theory and lucid action.

The other, “invariantist,” view, which would later spread over a large part of the radical current, is the model of the circle of relations among “theoreticians.” In this case, the enormous totem-fetish of theory conceals the unilateral nature of relations limited to a tiny elite of “critics.”

Such an attitude, now that the illusions regarding a rapid and abundant “production of revolutionaries” have dissipated, amounts in reality to pure and simple individualism. Instead, there is nothing left to do but to adjust to the fact that the revolutionaries are now isolated. To increase their current powerlessness by taking a position against organization does not make any sense. The alternative of continuing to pursue this option, in an environment of the anxious atomization of revolutionaries, insisting on the anti-Mafia phobia and on the exclusivity of relations between a handful of the elect (if one can find any such elect) at the highest level (higher than what?) of theory, is not very attractive.

Although it is now clear that the resurgence of activism and militancy rapidly leads back to politics, it is also clear that the fetish of theory separated from collective efficacy and, if possible, organized practice, offers no way out. Communist principles, united with a critical theory animated by its contrast with the theory of the previous two decades and with the principle results of the recent past—that is: a revolution of and for life, a questioning of the limits of the ego and of personal identity (which in the work of Cesarano are denounced vehemently and comprehensively), the experience of a revolution in the revolution—are the only antidotes against the Mafioso degeneration, which cannot be escaped by way of self-valorizing isolation, and much less by the original and personal road of an alleged creativity.

It is obvious that in 1970 there was no danger posed by the possibility that a militant-activist group associated with Invariance or a core group of “theoreticians” would be formed. In fact, the danger was just the reverse: disintegration and the neglect of the most important questions that should have been addressed:

-

The reformulation of the contribution of the historical ultraleft (Bordiga and the most consistent sector of the German revolution, which were decisive for the world revolution);

-

Draw up a balance sheet of the new contents contributed by the sixties;

-

The need to create a network of relations capable of enduring and prepared to reinitiate the revolutionary possibilities that were presented during the seventies.

According to Camatte and Collu the “production of revolutionaries” would magically resolve all problems, when what actually took place immediately thereafter was the dispersion of the revolutionaries, and it became evident that they were incapable of taking advantage of the opportunity that would be once again, and only in Italy, be presented.

In the following years the question of nihilism arose, still posed in terms that were upside down with respect to reality: in reality the expressions of nihilism were the abandonment of the revolutionary tradition, the end of the search for communist relations among subversives, the denial of the need to become an effective community, and the underestimation of the need to avoid being dragged down by the counterrevolution.

Comontism was a caricature of relations between revolutionaries, with its illusion that all problems could be magically resolved by the right ideology, and its pretension of being the embodiment of the theory of the sixties, now complete, which only had to be applied in practice without any delay. Although it was aberrant and unsustainable on the theoretical plane, this simplification was based on a profoundly correct demand: theory cannot be a separate and specialized activity, it is an integral part of the everyday coherence of revolutionaries and the need to change reality in its entirety, to have an impact on society and on history.

Comontism had a doubly counterproductive result:

-

Because it created a gang that proclaimed itself to be the enemy of society and the proletariat, preventing any possibility of forming a pole of regroupment and of having an effect on society;

-