Portia Ladrido

The anarchists making a difference in Philippine society

The misconception about anarchism

The motivations of Filipino anarchists

These anarchists’ ideology is about the belief that humans are wired to pursue the common good, regardless of an authority figure. From left: Bas Umali, Chuck Baclagon, Ron Solis, Fread de Mesa, and Taks Barbin. Photo by JL JAVIER

Manila (CNN Philippines Life) — A blue, mini gas tank with a cooking dock sits on the corner of Taks Barbin’s living room. He turns the knob, puts a water-filled kettle on top of the dock, and opens foldable plastic chairs, forming a circle. This living room is a modest extension of his bedroom; a space that makes up a part of the interconnected shanties that snake around one of UP Diliman’s side streets.

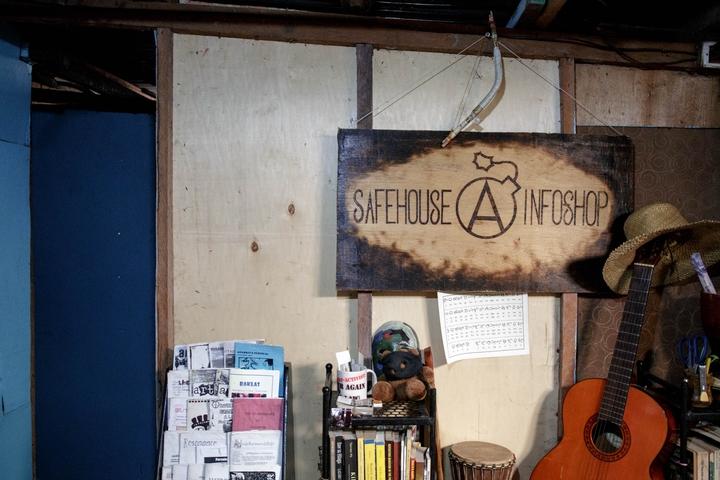

“Karamihan [ang] tawag dito ‘infoshop,’ a place na pwede kang mag-share ng information,”{1} says Barbin while pointing towards the other side of his living room — a corner neatly crammed with worn-out books, original and photocopied zines, and indigenous musical instruments. The wooden sign above this corner reads “Safehouse Infoshop,” with the capital letter ‘A’ enclosed in an illustration of a detonating bomb.

Barbin, a student of UP’s Malikhaing Pagsulat sa Filipino{2} program, pours the hot water to two brown mugs and gives the other one to Bas Umali, a long-haired Uber driver dressed in a T-shirt with the words “In Defense of Autonomy” running across it. Bas, like Taks, also runs his own ‘infoshop,’ called Onsite, headquartered in the slums of Muntinlupa where they publish zines that discuss the solutions to the rampant flood in the area.

“Ganoon din [ang] mga typical na ginagawa ng mga infoshops — gumawa ng publication, [tapos yung sa amin] tungkol sa baha, nag-aatake [din] kami sa local politicians. Tuwing eleksyon, nag-co-conduct kami ng mga anti-election na campaigns,” he says.{3}

The Safehouse Infoshop is a space in UP Diliman where anarchists share books and zines about disaster communism, critical thinking as an anarchist weapon, and community-organizing, among many others. Photo by JL JAVIER

A closer look at the piles of literature at the Safehouse reveals some of the written works by social activists and anarchist writers Errico Malatesta and John Zerzan, as well as manifestos on disaster communism, critical thinking as an anarchist weapon, and community-organizing — materials that could deepen the knowledge on a controversial philosophy: anarchism.

The ‘infoshops’ that Barbin and Umali separately started serve as a resource center where people within their communities can come in and share skills and solutions to problems specific to their community. It is also a place where anarchists convene to discuss political philosophies and the ways in which they can come together to further a certain cause — from promoting urban gardening to disrupting pork barrel.

Every year since 2014, during the Philippine president’s State of the Nation Address, their network of anarchists gather at the Quezon City Memorial Circle to hold a ‘peaceful protest.’ They call it Sining, Kalikasan, Aklasan, a day-long guerilla event where they share the many skills and solutions being done in their respective communities; solutions that need not come from any type of political leader.

“Na-experience ko na ‘yung working class na buhay. Wala ring mangyayari hanggang pagtanda mo, hangga’t kamatayan mo.” — Ron Solis

“Nandito ‘yung mga practical solutions sa mga problemang kinakaharap natin. Hindi naman nila[anarchists] inaangkin. … ‘Yung mga ginagawang activities hindi nila inaangkin na kami lang pwedeng gumawa nito, na kami ‘yung founder or vanguard or pioneer ng ganitong practice … May mga ganoon, dati siguro. Mga old school tawag namin [sa kanila],” says Barbin. {4}

Umali fiddles with his phone while explaining how this “new school” of anarchists works. “Walangrecruitment, walang organization dito. … Pero hindi ibig sabihin na disorganized tayo, hindi ibig sabihin na kanya-kanya tayo,” he says, almost contradicting himself in one breath.{5}

“Organized tayo sa paraan na voluntary ‘yung process ng pag-oorganize natin at nakabatay iyon sa sarili natin — kung ano ang kaya nating i-taya, i-commit na oras, na resources, at iba pa,” he says. “Hindi ito ‘yung para maging aktibista ka, sasali ka sa LSF [Libertarian Socialist Federation] … parang si Bonifacio, tapos makabayan ka? Hindi ganyan iyan,” Umali adds, while mimicking historical revolutionaries of the Philippines that slash their wrists in the name of solidarity.{6}

“Nandito ‘yung mga practical solutions sa mga problemang kinakaharap natin,” says Taks Barbin, an anarchist and a student of UP Diliman’s Malikhaing Pagsulat sa Filipino program. Photo by JL JAVIER

A seaman for five years prior to being a ‘full-time anarchist’, Ron Solis spends his time volunteering for environmental organizations like Greenpeace and 350. Photo by JL JAVIER

The misconception about anarchism

The anarchist that the general public has come to picture is more than a revolutionary fighting for its country; they’ve been portrayed as groups of people in all-black ensembles with ski masks and baseball bats in tow, ready to smash the nearest glass window. The term is often equated to chaos in the streets, the police stopping ‘rebels’ with riot shields and fire extinguishers.

This picture that circulates within the public’s modern consciousness was purportedly due to the highly mediatized World Trade Organization protest in Seattle in the ‘80s. These men with faces covered in handkerchiefs are called Black Bloc anarchists, a sect of anarchism whose main method of protest is property destruction.

Umali, a then-leftist turned anarchist, explains that within the anarchist network, people do various things to push for what they want. Some anarchists’ mode of protest may be simply giving out things in what they call a ‘free market,’ while others, like the Black Bloc anarchists, do take a more ‘violent’ route.

Bas Umali, a then-leftist turned anarchist, declares himself as an anarchist primarily because of political necessity; not wanting to be confused for being a Marxist. Photo by JL JAVIER

“Ang focus nila sisirain mo ‘yung symbols ng oppression, ng capitalism, kaya kadalasan nabibiktima yung Starbucks, McDonalds.‘Yung mga malalaking corporate symbols, ‘yun ‘yung mga binabanatan nila,” says Umali.{7}

After the rage of riots in the U.S. in the ‘80s, Umali witnessed that a more politicized punk scene in the Philippines suddenly started to take root. “Kasi dati, yung mga 1980s na punk, mas cultural ‘yun eh. … Sex Pistols na anarchy ‘yun. Karamihan sa kanila, mas na-o-organize pa ng Left,” he says. “Pero mga1996, diyan na nagsulputan na nililinaw ng mga indibidwal na ito na hindi sila Marxist, hindi kami leftists, kami ay mga anarchists.” {8}

The motivations of Filipino anarchists

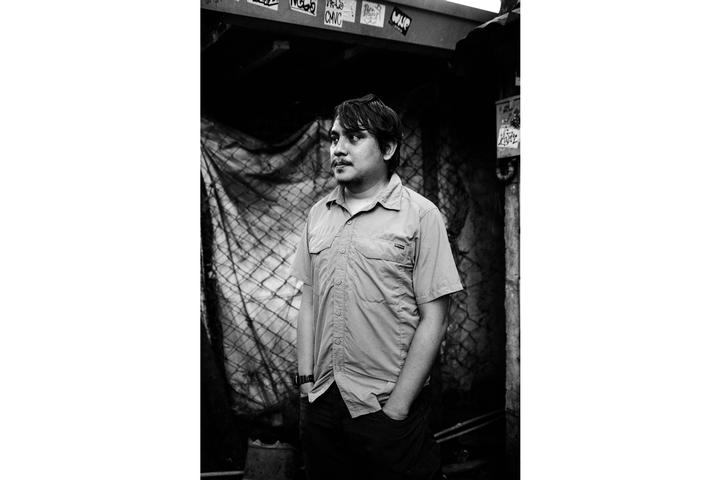

The sound of multiple footsteps stepping on twigs and dead leaves starts getting louder. Fread de Mesa, a man in dreadlocks and tunnel earrings, knocks on the door of Barbin’s living room. “Tokhang, tokhang,”{9} he teasingly whispers. Behind him is Chuck Baclagon, in a gray button-down wearing a cap that resembles Che Guevara’s military beret, and Ron Solis, wearing a half-grown beard and a necklace with a Baybayin pendant.

Together they complete the chairs Barbin arranged in a circle. One by one, the newly arrived anarchists start sharing what attracted them to the anarchist scene, despite all that it is generally perceived of it.

“’Yung involvement ko sa mga anarchists, nagsimula sa simbahan... tawag sa kanila mga Mennonite and Anabaptists tapos ‘yung tradition ng simbahan ngayon mas naka-ayon doon sa justice and peace na usapin. May pagka anti-authoritarian din ang nature,” says de Mesa, still an active member of Peace Church Philippines, instantly breaking the image of the stereotypical churchgoer one may conventionally imagine.{10}

“Hindi sila naniniwala sa absolute na kapangyarihan ng State. Basta ‘yung allegiance ay wala sa estado or sa presidente, kundi [na kay] Jesus Christ,” says Fread de Mesa, a member of the Peace Church Philippines and an anarchist. Photo by JL JAVIER

Chuck Baclagon got involved with the anarchist network through his work with 350.org, an international environmental NGO that fights to eradicate the use of fossil fuels. Photo by JL JAVIER

“Halos madami silang pinagsasaluhang value system ng mga anarchists. Hindi sila naniniwala saabsolute na kapangyarihan ng State. Basta ‘yung allegiance ay wala sa estado or sa presidente, kundi [na kay] Jesus Christ, sa broader church, at nasa community,” he adds.{11}

Baclagon, on the other hand, got involved with the anarchist network through his work with 350.org, an international environmental NGO that fights to eradicate the use of fossil fuels, among others. “Kahit anong gawin mo na activity or campaign na may kinalaman sa reduction ng emissions, ano ‘yun, 350 ‘yunmost likely ... Maraming mga ganoon din [ang] ginagawa sa anarchist na community,” Baclagon says.{12}

“Hindi naman pwedeng hindi ka kikilos dahil hindi mo siyang magagampanan ng tuluyan eh. Kasi kung hindi ka kumilos kasi hindi mo siya nagampanan, walang nabago.” — Chuck Baclagon

While de Mesa and Baclagon are still within civic society organizations, Solis has stopped working altogether. A seaman for five years prior to being a ‘full-time anarchist’, he spends his time volunteering for environmental organizations like Greenpeace and 350.

“’Pag magtratrabaho ka [kasi] nasa ano ka parin, nasa sistema ka parin eh. Ganoon parin ‘yung problema. Eh mag-sarili ka nalang. Gumawa ka nalang ng sarili mong diskarte,” Solis says. “Na-experience ko na ‘yung working class na buhay. Wala ring mangyayari hanggang pagtanda mo, hangga’t kamatayan mo, nasa [baba] ka parin ng [pinakababa].” {13}

The difference between the far Left and anarchism

The group exchanges personal stories of how they found anarchism or how anarchism found them; their insights reek of the anti-establishment, anti-authoritarian ethos that seems to bind them all. Their discussions are heavy on turning their backs to consumerist practice, from exploring ways to start farming in their own backyard instead of buying in the supermarket to employing themselves instead of submitting to a manager.

On the surface, it looks as if their motive to subvert capitalism is no different from the far Left.

“Actually, ‘yun ang dahilan kung bakit ako nag-dedeclare na anarchist ako. Kasi kung tutuusin wala namang pangangailangan na sabihin mo na anarchist ako … Ang sa akin, political necessity ang pag-declare ko na anarchist ako. Kasi merong Left na nag-do-dominate siya, sinasabi niya na ang rebolusyon nila ay kung ano lang ang sinasabi ng Left,” Umali explains. {14}

He goes into detail of where this confusion between anarchism and communism may come from. He says that the many variations of the Left usually extract their ideologies from Marxism, and anarchism may have been a byproduct of this as well.

Ideologies, beliefs, and countercultures tend to enter society in waves. Umali believes that they can keep their culture alive so long as they leave materials for the next wave of Filipino anarchists to come. Photo by JL JAVIER

“Naging Marxist-Lennist, naging Maoist. Kaya kung mapapansin mo, anarchy siya, hindi siya naka-attach sa pangalan. Hindi katulad ni Marx, kilala mo na kung sino yung lider niya, kilala mo na sino si Lenin, si Mao, or kung sino ang mga Bolsheviks,” he continues. “Walang ownership [ang anarchy]. ‘Yun ‘yung sinasabi kanina ni Taks, ‘yung mga ginagawa din namin [sa infoshop], recognition din ito na ginawa na ito ng mga ninuno natin dati. So sino ka para pag-arian mo at sasabihan mong, ‘kami ang gumagawa nito?’” {15}

The conversation on political philosophies amplifies, as they simultaneously mention the ‘failed’ socialist and communist governments of China, Germany, and Russia. Baclagon further clarifies this assumed misperception between anarchism and the Left. He goes deep into challenging Karl Marx’s First International, the federation of working class men who swore to end the dominant economic system and replace it with cooperative ownership. He explains the failings of the mode of production narrative, and cites the teachings of Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin that says that Marxism will just breed another form of dictatorship.

“Kasi kung tutuusin wala namang pangangailangan na sabihin mo na anarchist ako … Ang sa akin, political necessity ang pagdeclare ko na anarchist ako.” — Bas Umali

Despite the flaws of the Left, Umali, a former member of Kabataang Makabayan, a leftist group founded by Communist Party of the Philippines leader Jose Maria Sison, acknowledges the organization’s genius in systematically drilling communist ideologies into his then young, impressionable brain. He says that leftists have a knack for articulating the goal of the movement; a trait that he thinks anarchism still lacks. But Umali questions the ways of the Left, particularly the Protracted People’s War, a political revolution strategy developed by Mao Zedong.

“Ba’t tayo naging makabayan eh komunista pala tayo? Kasi talagang oxymoron eh. Doon talaga akong unang nagkaroon ng duda. Tapos kinuwestiyon ko ‘yung Protracted People’s War. Baka naman maubos na yung kalikasan natin, giyera parin tayo ng giyera,” he recalls.{16}

A capitalist world

It might still be perplexing to some to see these anarchists in a circle, with urban shacks as the backdrop, fiercely discussing the ‘anti-isms’ of society, all the while knowing that Umali drives a tangerine Vios as an Uber driver and de Mesa still participates in one of the biggest organized systems in the world — religion.

“‘Yung sa kasaysayan kasi, ‘yung role ni Jesus Christ ay chinallenge yung State. Chinallenge ‘yungRoman empire sa ibang lifestyle,” de Mesa explains. “Natutunan namin na mas nakikita namin si Jesus sa mga anarchists. … Sila ‘yung ginagawa nagpapakain sa mga nagugutom, dumadalaw sa mga may sakit… Tapos basic ‘yung self-agency. Napakalakas ‘yung pag-recognize nung capacity ng individual na mag-ambag sa kabutihan ng mas nakakarami.”{17}

The anarchists’ discussion are heavy on turning their backs to consumerist practice, from exploring ways to start farming in their own backyard to employing themselves instead of submitting to a manager. Photo by JL JAVIER

But how does an anarchist thrive in a society where every single move is powered by consumerist dogmas? When asked how they settle this tug-of-war of opposing ideologies, Baclagon is quick to come to their defense. “Hindi naman pwedeng hindi ka kikilos dahil hindi mo siyang magagampanan ng tuluyan eh. Kasi kung hindi ka kumilos kasi hindi mo siya nagampanan, walang nabago,” he says. {18}

For these anarchists, while they may come from different interest groups, they all form the same basic principles of ‘true’ anarchism: that anarchism values the capacity of the individual to organize itself; that anarchism sees the role of the individual as a tool that contributes to a larger community; that anarchism is about mutual aid, directly helping any soul in need; and that anarchism is about the belief that humans are wired to pursue the common good, regardless of an authority figure.

“Tingin ko, ‘di ko din naman aabutin sa lifetime [ang malawakang anarchism.] … Tingin ko ang pinaka-ma-co-contribute [talaga] natin ay mag-iwan ng maraming materyales,”{19} Umali says, as he briefly sizes up the corner of Barbin’s living room awash with shelves and shelves of anarchist materials, lying in wait for another wave of people to enter the scene, quietly asserting their rightful existence.

{1} This here is usally called an infoshop, a place where we can share information.

{2} Creative Writing in Filipino

{3} That’s what infoshops typically do. They create publications. As for us, we talk about the floods, and we criticize the local politicians. Every election, we also conduct anti-election campaigns.

{4} The practical solutions to our current problems are here. Anarchists don’t claim to have ownership of these solutions. The activities that they do, they don’t go and say “Only we can do this, we’re the founders, or the vanguard, or the pioneers of these practices. Where there others like that? Of course, in the past. We call them oldschool.

{5} There’s no recruitment, no organization here. That’s not to say that we’re disorganized, or that we do everything on our own.

{6} Our way of organizing is a voluntary process. It’s based on what we can contribute. Whatever you can contribute, you contribute. Commit your time, resources, etc. It’s not like you become an activist, and join the LSF [Libertarian Socialist Federation]... like Andres Bonifacio, Philippine revolutionary, and then you become a nationalist. It’s not like that.

{7} Their focus is on destroying symbols of oppression, of capitalism. That’s why they target Starbucks, McDonald’s. The large corporate symbols, that’s what they go for.

{8} Because before, the 80’s punks, it was more cultural. It was Sex Pistols anarchy. A lot of them organized with the Left. But around 1996, people started to clarify their positions, that they weren’t Marxists, that we weren’t leftists, that we were anarchists.

{9} [A black humor joke. Tokhang Tokhang is a slang term for when police knock on your door in a drug raid. It’s also slang for an extrajudicial killing.]

{10} My involvement with anarchists started in the church. They were called Mennonites and Anabaptists, and their church tradition focuses on justice and peace, and it was anti-authoritarian in nature.

{11} Most of their value system matched with the anarchists. They didn’t believe in the absolute power of the state. As long as your allegiance is with Jesus Christ, with the broader church, and in the community, you cannot pledge allegiance to the state or any president.

{12} As long as you’re involved in an emission reduction campaign or activity, it’s probably with 350.org. A lot of people in there are also in the anarchist community.

{13} As long as you’re working where are you? You’re still in the system right? That’s where the problem lies. Better to be on your own. Focus on your own hustle. I’ve experienced the working class life. Nothing will happen as long as you remember this, when you die, you’re still as low as dirt.

{14} Actually, that’s why I call myself an anarchist. Because, from your point of view, there wasn’t any reason to call myself an anarchist. For me though, it was a political necessity to declare myself an anarchist. Because there’s a Left that dominates. They say that “revolution” is only what the Left says it is.

{15} It became Marxist Leninism, and Maoism. But if you notice, anarchy, anarchy isn’t attached to any thinker. It’s not like Marx, where you know who the leader is. People know who Lenin, Mao and the Bolsheviks are. No one owns anarchy. That’s what Taks was saying, what we do in the inforshops, we recognize that it’s passed down from those who came before. So how can anyone come along and say “This is our work?”

{16} Why did we become nationalists if we were actually communists? It’s an oxymoron yeah? That’s when I had a realization. Then I questioned Protracted People’s War. We’re here killing the Earth, and we’re still fighting our wars.

{17} In history, the role of Jesus Christ was to challenge the State. He challenged the Roman Empire with a different lifestyle. We found out that we could see Jesus with the anarchists. They’re the ones who are feeding the poor, healing the sick, and the self agency is basic. It’s empowering to recognize the capacity of the individual to help the masses.

{18} You can’t just do nothing just because it’s not your responsibility to uphold. If you do nothing, nothing will change, so act!

{19} If you ask me, anarchism will never come in our lifetimes. I think that our greatest contribution is the foundation that we leave behind.

Translations courtesy of u/brennanfiesta, u/Rallph_, u/Siantlark, on reddit.