Peter Gelderloos

Consensus

A New Handbook for Grassroots Social, Political and Environmental Groups

The Radical Importance of Decision Making

Structure and Structurelessness

Why is Consensus so Difficult?

Changing the Format of Discussion

Making Decisions without the Whole Group

Mission Statements and Principles of Unity

An Unforgivably Quick Rundown of Common Power Dynamics

Frequent Problem Characteristics

Teaching Consensus to New Members

Introducing Consensus to a Group

Introduction

Making the shift to the consensus decision-making process might be the most important thing that we can do to build a democratic society. Consensus can give us the power we need to focus our society’s attention on improving education, making peace, providing universal healthcare and creating the world we desire.

Consensus creates true democracy—not the democracy in name only that sickens any aware person. Consensus empowers all who participate in it. In-name-only democracy disempowers all who participate in it (who dutifully trudge to the polls every few years to select new masters). True democracy might be a large part of the solution to our most pressing problems. In-name-only democracy is little more than a smokescreen for domination and an excuse for war. Thus, this book addresses one of the most important topics of our time.

It’s ironic that at the time when in-name-only democracy in the United States may be nearing its end, with the congress and courts allowing the executive branch to seize their powers, an interest in a more powerful system of democratic decision making is emerging. Many prominent Americans, such as former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, former Vice President Al Gore and former senator Gerry Hart, are expressing concern about the possibility of a Bush dictatorship. Yet for all the words of alarm, relatively few people are talking about solutions. It is self-evident that representative democracy has failed to express the dreams of most of the people it supposedly represents—both here and abroad. Iraq is merely the latest example of such failure.

At the same time the U.S. government is promoting “democracy” in the Middle East via bombs, guns, and torture, movements around the world are enthusiastically embarking on the search for real democracy. Consensus decision making is used around the world by indigenous people in resistance, who have used it for millennia—groups like the Zapatistas, and organizations in the United States such as Earth First!, Indymedia, and some Green Party chapters.

One of the most prominent groups using consensus is Food Not Bombs (FNB), which now has over 300 chapters worldwide. Food Not Bombs’ members adopted formal consensus as FNB’s decision-making process because it reflects FNB members’ values. Consensus has also been an effective way to encourage commitment to the tasks and goals of Food Not Bombs, and has made it more difficult for the authorities to infiltrate Food Not Bombs groups and disrupt FNB actions.

In fact, the use of consensus by Food Not Bombs and Indymedia may be one reason the FBI in Texas placed both groups on its “Terrorist Watch List.” Examples of effective, nonviolent, truly democratic groups are a clear threat to a “democratic” government based on hierarchy, coercion, intimidation, and violence. Lest others see and imitate the truly democratic practices of Indymedia and Food Not Bombs, the government attacks and smears those embodying the values it supposedly represents.

Why is consensus decision making so revolutionary? Consensus is on the cutting edge of global social change because it reflects the core values that every truly progressive political and social group is working towards. Consensus encourages its participants to express their interests directly to their group, and it ensures that all are heard. It is cooperative, not adversarial. It gives everyone affected by a decision the power to consent to (or block) that decision. Because all are heard and all have an equal Say, consensus is an ideal way for groups and organizations to discover the true desires of their participants and to reach decisions that best reflect the goals and values of those participants.

So, it’s no accident that groups that use consensus well tend to be strong and effective. Consensus often results in a synthesis of ideas that is better than the original “competing” ideas. And consensing on decisions usually produces greater commitment to those decisions than would be the case if a voting process was used, with “winning” and “losing” sides, and with the “losers” grudgingly acquiescing to decisions they dislike.

Consensus decision making is one of the most revolutionary practices any group can adopt. For me, consensus decision making zs the revolution. Consensus provides the democracy that the world is searching for, and this book is a means of discovering how to make that democracy a reality.

—Keith McHenry Co-founder of Food Not Bombs

Preface

The Radical Importance of Decision Making

The historical evolution of government has involved an increasing consolidation of decision-making power in the hands of bureaucrats, technocrats, and public officials. Simultaneously, progressive or radical elements have struggled for greater access to power, often as part of a greater movement for decentralization and democracy. Power structures have responded to these pressures by adopting more democratic forms on the one hand, and on the other by removing ever more decision-making power from the public sphere.

In modern democracies, voting rights are considered universal (though in actuality they exclude people younger than eighteen, non-citizen immigrants, a percentage of ethnic, racial, and political minorities intimidated away from the voting booths, and in some countries, convicted law-breakers); however individuals and communities enjoy less and less autonomy, as schools and other institutions are subjected to increasing government oversight, laws governing ever more minutiae proliferate, the economy is centralized and globalized, media are consolidated, and commercialism invades and appropriates public spaces.

Many people have heard the truism about means determining ends, about being the change we wish to see in the world. Leaving aside the implicit oversimplification regarding tactics of resistance, this truism actually is important in regard to decision-making methods. Throughout history, human groups have demonstrated an almost infinite variety in social organization and political strategies. An anti-hierarchical society, and the attendant decision-making strategies, are certainly within our reach if we look past the economic structures, military and police forces, and popular culture that currently stand in the way of the necessary changes. In addition to overcoming the organized barriers of economic and state violence, we need to relearn how to be social animals, and become practiced and comfortable with new models of decision making.

In building our resistance, we need to resist our own authoritarian habits. In empowering ourselves, we need to become familiar with social power that is based on equality, not exploitation. We need to learn consensus.

The Benefits of Leadership?

Part of our education as subjects of an authoritarian society is indoctrination in all the supposed benefits of hierarchy and leadership. It is an article of faith. Yes, dictatorships, including those kinds that allow general participation through majoritarian voting, are expedient in one sense, but this expedience masks a more profound inefficiency. Hierarchy developed to allow group activities to be controlled and exploited by a central leadership, not because hierarchy increases the possibility of realizing human potential. Quite the contrary: authoritarian systems suffocate the individual. Because hierarchies must limit the number of people who rise to positions of leadership, more people must be followers than leaders, and they are thus prevented from developing their potential for thinking and acting autonomously, or establishing voluntary relationships with peers—their activities, and their relationships, are dictated by their position in the hierarchy. Everyone must work for the singular initiative of the person or people at the top of the pyramid. In contrast, in a horizontal society, everyone is free to pursue their own initiatives and, through cooperation, accomplish more.

Non-hierarchical organizing and decision making is also more efficient than traditional hierarchy because it frees up a great deal of energy and resources that would otherwise go to enforcing the party line and keeping people passive and obedient. In fact, authoritarian decision making only appears to be more expedient because in our society it is the type people have the most practice with. With time, radical organizations can learn to organize and make decisions at least as quickly and efficiently as they might using authoritarian methods.

Perhaps the most important disadvantage of authoritarian organizing and decision making is that it preserves the oppressive power dynamics that exist in society at large. In a racist, sexist, capitalist society, white people, males, and those with a college education hold power that they do not deserve over people of color, women, queers, and trans people, and those without a diploma. This generalization even holds true in many radical groups. It is not at all unusual to see progressive and radical organizations with a leadership (official or unofficial) consisting entirely or mostly of white, college-educated males. Even in hierarchical groups with a diverse leadership, oppressive dynamics are likely to persist. A hierarchy preserves an elite culture, so women or people of color who climb the ladder often do so by adopting that elite culture and disowning their solidarity with those they’ve left behind at the bottom of the hierarchy—we see this all the time when conservatives appoint a token woman or person of color to a powerful government post. Efforts by group members to challenge these oppressive dynamics are seriously hampered when power is concentrated in the hands of a privileged authority. Not only are oppressive dynamics harder to change, they are encouraged. The existence of a hierarchy isolates group members from one another, so feelings of hostility are more likely to develop than feelings of solidarity.

This tendency is compounded by the fact that the goal of authoritarian decision making is not to come up with the best solution for everyone, but to win. Majoritarian voting is especially good at fostering competition and creating minorities within a group. This method makes sense in a world where people have to exploit one another to survive. It does not make sense in a world based on mutual aid, freedom, and cooperation, and it does not make sense if we are trying to build solidarity to create that world. Hierarchy and authoritarian decision making were developed so that elites could control the collective power of a society. We must develop antiauthoritarian decision-making methods that keep power in the hands of all, to free society from that legacy.

Representation

Authoritarian states that call themselves “democratic,” after the slave-driven Greek polities, have given us the idea of representation as a means of achieving equality. The masses have power to elect and recall representatives, and the representatives have the power to work in an efficiently small group to manage the details of everyone’s lives. Such a system purports to overcome the authoritarianism of leadership, without descending into the presumed chaos of leaderless social organization. Efficiency is the ultimate justification, and in truth it would be inefficient to bring everyone from a massive nation or multiregional organization together in a huge meeting to make decisions. But that proposition itself demands scrutiny. Under what circumstances do human groups become too large for horizontal consensus decision making to be practical? The nation, in the Western sense, is not any naturally arising unit: it is a manufactured identity designed to achieve political unity within the territory conquered and controlled by a central leadership. Absent the attempt to subordinate large numbers of people to a hierarchy, human polities will be only as large as they can be to accommodate horizontal, leaderless decision making. Hierarchy did not evolve to answer questions of efficiency. Hierarchy developed to impose control, and to use that control to expand the group, to specialize and alienate daily activities, and to centralize power, until society could not run without hierarchy. Leaders were not needed originally, but once in power they imposed the economic, social, and political changes that made them “necessary.”

In the present mass societies, activists may often have a need to communicate and coordinate across distances or among huge groups of people. This need, and our socialization, may influence us to adopt the same representational forms of organization as those employed in the institutions we are fighting. The idea is that activists need as large an organization as possible to direct a unified effort to organize the masses. But groups of individuals are turned into masses in order to be controlled. Activists not wishing to be the vanguard of some new authoritarianism need to break themselves and their communities out of the disempowered, alienated “mass.” Communities can work together in a spirit of solidarity and mutual aid without centralizing decision-making power. Activists in Virginia can communicate with activists in California to share information so that each group can make the best decision on how to effectively overcome a common enemy, but there is no need for different groups to come to the same decision: what works for one may not work for another.

Organizations or federations that for whatever reason join groups from multiple communities should be structured in a way that makes it impossible to forget that power flows from the level of the community and the individual. The spokescouncil model used at a number of major protests by the antiglobalization movement is an effective alternative to a permanent body of formal representatives who have assumed full decision-making authority for their constituency.

A large number of affinity groups with a common aim each send spokespersons to meet and discuss the action that all are planning to participate in. They may just share the potential plans, targets, or capabilities of their affinity groups, so that the spokespersons can go back and communicate the broad picture to their groups, and then each group can have better information to help formulate their specific plans. The spokescouncil can also take a more active role. Spokespersons can communicate the desires, limitations, and general goals expressed by their affinity groups, and using that information as a starting point, the spokescouncil can create a structure or framework that assists each affinity group in pursuing its desired ends, and allows each affinity group to work together without ever relinquishing the ability to decide its own course. Examples of how a spokescouncil can create a useful structure rather than dictating the contributions of each member group include providing tactical information (maps, surveillance, etc.) and resources (bicycle locks, PVC pipe, legal and medical aid, etc.) for affinity groups to set up road blockades during a protest, or by setting up days of action and sharing useful information for a campaign to simultaneously target multiple locations of a particular corporation or other institution.

Just as political hierarchies exist to control a society, an activist organization may use hierarchy to try and control a movement. Leadership is not about efficiency, it is about control. People can struggle without being told how to do so. History shows that when governments face an enemy without a leader, whether mutinous workers or an indigenous society, they appoint one, and then negotiate, co-opt, assimilate, and control. A leaderless opposition is the hardest to defeat.

Individual Autonomous Action

In the absence of formal leadership, there is an array of horizontal decision-making strategies. There are forms of decision making other than group consensus that would have a place in a free society, and can also play an important role in consensus-based organizations. At a very basic level, the individual should not be subordinated to the group to the extent that individual, autonomous action is discouraged. Such action, performed by lone individuals or small groups of individuals, is vital in a number of circumstances: when security concerns prohibit discussion of an action in a larger group; when people need to act out of the possibly stagnating confines of a group, and act without broader approval in order to stir things up or spark initiative; or when the project at hand is of a creative or personal nature that could not brook a potentially homogenizing or stifling group process. However, the potential of individual action is limited, because it fails to foster social growth in dominant and submissive people, and other people who need to learn to work as part of a group, and it fails to build the strong relationships that are the backbone of a serious revolutionary movement. Ultimately, individual actions must exist with consideration of group decisions, just as individuals exist within the context of larger human groups.

Spontaneous Consensus

Once a group decides to use consensus, there are countless varieties from which to choose. The kind most people are familiar with is spontaneous, or informal, consensus. It’s the kind of decision making you use with good friends and in other healthy relationships. No articulated process is needed, and no leadership, because of a strong foundation of trust and intimacy. This is what consensus looks like when we’ve had a lifetime of practice. Needless to say, it is an unrealistic goal to use spontaneous consensus for political organizing, unless your organization consists of a small group of close friends.

A look beyond the often insular confines of Euro/ American activist circles reveals numerous indigenous societies that are non-authoritarian and use consensus decision making. (Indigenous and Afro-Colombians in the Choco area, for example, use consensus for the decisions of entire communities, and for decisions in regional councils that include as many as 50 communities.) Each society’s model was/is a little different, and best suited to people of a particular cultural background. Many of these societies first had authoritarian decision-making models imposed upon them during the colonization process.

In any case, the historical abundance of cooperative, consensual groups gives lie to the claim that competition and authoritarian leadership are simply parts of human nature. However, indigenous models of consensus exist within a specific cultural and historical context. The consensus model described in this book is the model I have learned among the North American queer activists, anarchists, anti-racists, and anti-capitalists with whom I organize. Most of these activists have grown up white and middle class. The model they use is most practical and helpful for people from a similar background. It is important to recognize that culture is inherent in every human act; the form of consensus described in this book is a cultural artifact. It is not the single correct way to make decisions, and it is a process that should be open to change, especially when your organization consists of people from varied backgrounds.

These pages describe a very detailed, organized process. I include exhaustive discussion of process because process is an effective crutch or bridge for people not used to anti-authoritarian decision making. With practice, the process can be set aside, like any tool that is no longer useful.

Consensus Process

Adopting a conscious consensus process is significant in a number of ways. Commitment to the ideal of consensus signifies a bold rejection of society’s dominant values of order, hierarchy, competition, and formalized leadership. In this way, embracing consensus rejects the generally unspoken Western assumption that dictatorship is efficient; that people need leaders to recognize and pursue their own interests; that life, evolution, and progress must be fueled by a brutal competition between individuals rather than by the mutual aid and voluntary cooperation of human groups. The idea of consensus also pushes anti-authoritarian resistance to develop and demand an even more fundamental understanding of freedom. The notion that freedom is a legal concept that can be guaranteed on paper is rejected; this new freedom only comes when po__ aspect of our lives can be dictated to us—in other words, it means that our involvement is crucial to the decisions that will affect our lives.

Adopting an explicit process to facilitate consensus decision making signifies a new understanding of human potential. It acknowledges that we are not the slaves of “human nature” or any other tragic flaw, but that we can learn an almost unlimited range of behaviours.

An explicit consensus process serves as a crutch or bridge which intentionally reinforces the learning of consensus until a new, cooperative, anti-authoritarian society provides that reinforcement as a matter of course. The process also recognizes that the oppressive systems of our society deeply affect our own behaviours, and that people who are typically silenced by our society can also be marginalized within ostensibly anti-authoritarian groups unless there is an intentional structure that helps expose and overcome these power dynamics.

Consensus Process

Group Meetings

Trying to change the world often means engaging in tedious work, but even so, meetings tend to be more painful experiences than they need to be. People who attend a consensus meeting and come away with a bad impression frequently report one of two complaints. Sometimes they feel like they have entered a tight-knit social club with rules that are secret and inscrutable and power dynamics that are cliqueish and impenetrable. At other times, newcomers get the impression that a particular consensus-based group is hyper organized to the point of inefficiency, and almost bureaucratic in its rules and procedures. Both extremes are disempowering. But unlike authoritarian organizations or governments, for which public meetings simply provide a rubber stamp to the decisions already made behind closed doors, consensus-based groups need meetings to organize group activities openly and fairly. People cannot be empowered members of the group if they do not know how to effectively participate in meetings. A shared understanding of how the meetings are to run will help keep everyone on equal footing.

Structure and Structurelessness

One of the hardest skills in consensus decision making is knowing when to be formal and when to be informal, and how to transition between the two. Structureless groups are likely to turn into social cliques with informal leaders perpetuating many of the same power dynamics we are fighting against in society at large. On the other hand, groups that are too heavily structured can be inefficient, heavy-handed, and unwelcoming to outsiders.

Finding a comfortable middle ground for your group can require a constant effort. Often, groups will be flexible, using different levels of organization and different processes at different times. Many consensus-based groups that meet regularly will spend most of their meetings discussing topics that only require simple decisions, or no decisions at all. Sharing updates about an ongoing campaign, announcing upcoming events, deciding if you want to host a particular workshop at your radical community space, organizing publicity for an event—many conversations can take place informally, without an explicit process. Group discussions that require a more formal process, such as solving problems and deciding strategies and actions, will probably come up less frequently, but are of huge importance. These types of discussions in particular are difficult, both in their own right and because of our upbringing in an authoritarian society that rarely lets us make such decisions.

Process of Discussion

Who has not had the excruciating experience of sitting through meetings in which discussion goes through endless, tail-biting circles with no progress or development? A decision implies both a question and a resolution. Therefore, the principle of effective discussion goes from general to specific, from inquiry to explanation to suggestion to solution. You can’t come up with a solution before you know what the problem is, and you can’t come up with a good solution until all the relevant questions have been answered, and group members have the information they need.

First, a group needs to express the problem. Doing this clearly and plainly can help everyone focus on the problem, and begin to think strategically. Second, those who lack important information need to ask questions and to receive answers. Then it is important, before talking about specific actions in response to the problem, to define success. What does the group want or hope to accomplish? What is the best solution to the problem at hand, and what is an acceptable intermediate solution? For complex or difficult problems, it can help to identify primary and secondary goals, long-term and short-term goals, ideal goals and compromise goals.

Only after all these steps have been articulated will it be useful to talk about and decide specific actions the group can take in response to the problem. Again, in discussing tactics, people should proceed from general to specific. Don’t start working out the logistical details of a tactic until you’ve made sure group members approve of the tactic and have decided that the tactic will help achieve the group’s chosen strategy. To properly consider the tactical questions in front of you, you may need to ask clarifying questions about one individual option, or even establish if it is logistically possible, but don’t get tied up in unnecessary specifics until you have defined the options and then agreed as a group on a definite choice.

One of the ways unscrupulous people pushing their own agenda can manipulate consensus process is by getting the group to delve into the details of a specific decision before that decision has been consensed on. In such cases, the people in your group will soon be too involved in formulating a certain course of action to remember that they were considering several other courses of action as well. Although real discussions are fluid and organic, thinking of the discussion as something that unfolds in stages can help your group openly and effectively consider all options, and prevent you from getting sidetracked.

NOTE: Work out a general framework before dealing with specific details of any one element of that framework. Express the problem. Ask questions. Answer those questions. Define success. Decide specific actions.

Process of Decision Making

It’s helpful to have a clear outline or flow chart of how decisions will be made in your group. Few things are more frustrating than to have a long discussion on a problem, only to find at the next meeting that some group members think a decision has been made, and others do not. Often this happens when some group members are more vocal than others, and interpret the others’ silence as agreement.

This brings up the problem of leadership. In a hierarchical society, an informal decision-making process allows informal leadership. Although informal leadership may be more flexible than formalized leadership, it is also less accountable, because it exists behind a facade of equality. Worse, it can and will accentuate unequal power dynamics already existing in the group.

How can we avoid this? To start out, the group as a whole formulates an agenda, and proceeding item by item, shares all the information at hand, discusses the topic with an eye to expressing goals and agreeing on a strategy, proposes a solution, reviews the proposal, and decides on the proposal. It repeats these steps for each new topic, until all agenda items are dealt with and the meeting is over. As long as all group members are made aware of this process, they will know exactly how decisions are made and can participate. Making decisions in this way does not require attending secret meetings, paying membership dues, knowing and being friends with the inner core of influential group members, or being able to talk more loudly or articulately than others. If would-be leaders attempt to manipulate or disregard an open and visible process, their actions will be more apparent than if they tried to do the same in a closed, informal, or hidden process.

Agenda

An agenda is simply a list of what your group will talk about at a meeting. Anyone who is a group member should be able to add a topic of discussion to the agenda. Naturally, the group should come up with an agenda at the very beginning of a meeting, if not before. Some people like to draw up the agenda before the meeting, so group members can decide how important their participation at that meeting will be, and start preparing for the discussions in advance. However, making the agenda in advance usually means that a handful of more involved group members create the agenda with little or no input from less-involved group members. This can and often does aggravate the problem of inequality within a group.

A good compromise is to create and publicize a preliminary agenda before the meeting, and then rewrite the agenda with new suggestions at the beginning of the meeting. A good way to generate a preliminary agenda is, at the end of a meeting, for the group as a whole to make a list of unresolved business to discuss at the next meeting. The preliminary agenda is then passed around by e-mail, telephone, word of mouth, or however the group communicates. Finally, it’s modified at the start of the next meeting.

At that next meeting, the preliminary agenda should be made visible by putting it on a poster or chalkboard, so that it can be easily modified. After your group decides on a final agenda, that agenda should also be posted so that, during the meeting, everyone can see where the group is and how much remains to be done.

Some agenda items will be problems that require decisions (these are the hardest, and will receive the most attention in this manual), but other agenda items do not require substantial discussion and decision. These include announcements (fundraiser at so-and-so’s house), complex announcements that require more question and answer before everyone fully understands (there’s a big protest in New York, this is what’s happening...), routine decisions with limited, well-established outcomes (where are we going to have our next meeting?), and autonomous actions that simply need the group’s yea or nay (“I’m organizing a radical movie night and I want to know if I can do it in the group’s name?”).

If the meeting is expected to be easy or routine, the order of agenda items can be left in the random order in which group members shout them out, as someone writes them down. However, if the meeting might be difficult, it can help to order the agenda items in a strategic way. Don’t leave the difficult topics for the very end, or everyone will be too tired or frustrated to discuss them effectively. Start out with an easy decision to get people warmed up for the hard ones. If you have more than one difficult topic, it helps to break them up with easy topics or other activities.

Announcements usually work best at the beginning of a meeting. Tedious discussion topics should not be scheduled at the beginning of a meeting, when people tend to be long winded; but such topics also should not be at the end, when no one will have the energy to deal with them. Decisions that are not urgent and can be put off for another meeting should go towards the end of the meeting, so that if the group runs out of time, you will at least have covered the topics of immediate importance.

Discussion

The group should discuss one agenda item at a time, until everyone agrees to go on to the next topic. Each time the group turns to a specific agenda item, the person who suggested the topic, or the people who know most about it, should give a quick background so everyone knows what is being discussed. Then everyone who knows something about the topic should go around and share information until all the general, relevant information has been covered. Depending on how much time the group has to talk about this agenda item, you may also bring up specific details, or instead mention resources where people can research the specific details on their own. Remember: relevance is important! No one wants to sit through a long meeting, so thoroughness should be balanced with conciseness.

As people volunteer information, group members should also ask questions until they are satisfied that they know enough to proceed. You don’t have to be an expert on the topic at hand, just competent to discuss it. Next, the group needs to decide its goals.

(The more diverse the group members are in their politics, visions, and worldviews, the more difficult it will be to agree on a goal. There sometimes comes a point when it is no longer effective for people to be working together in a group, because their desires are irreconcilable. For example, do we just want to raise awareness, or stop these trees from being cut down? Do we want to push the government to accept more public input and accountability in making logging decisions, or do we want to empower people to take direct action to physically prevent the logging? It is almost normal, in our alienated culture, for people to put substantial energies into a campaign without ever defining success.)

Once you have a goal, you need to decide upon a strategy to implement that goal. If a goal is a destination, a strategy is the path to reach that destination. We will raise awareness by teaching people the importance and uniqueness of this forest ecosystem/by showing how corporations hold influence over the political process at the expense of the public. Or alternately: We will stop these trees from being cut using civil disobedience to obstruct the logging operations and raise the political costs incurred by the decision-makers/ using sabotage and harassment to disable logging machinery and equipment, and to dissuade people from participating in the logging.

If a group knows what its goal is, and group members have a consistent and shared morality (do they favor civic duty or autonomy? Reform or revolution?), the basic strategy will follow on its own. A more complex strategy will take more thought, but simplicity can increase a strategy’s feasibility.

Tactics are the concrete steps and actions that are carried out as part of a larger strategy. Putting out a pamphlet, organizing a demonstration, blockading a road, setting up a free clinic, all of these can be tactics within particular strategies.

Too often, activists will carry out certain tactics, especially protests, as an empty habit or ritual, without understanding how that action will help achieve a goal, or even what that goal is. The point of a discussion is to make sure that everyone knows enough to address the topic strategically, and then move from a general understanding towards making a specific plan. Usually, people will disagree about the best way to confront the problem at hand. Discussion allows group members to evaluate one another’s thoughts, synthesize different ideas into a richer, more complete whole, and move towards a point of agreement that can be expressed as a concrete proposal.

Some decision topics are simple enough that the progression from goal to strategy to tactic is self-evident, and the only points requiring group decision are the logistical specifics. For example, if a group member announces that the group is out of funds, and there is a need for funds, and if neither of these bits of information are controversial, then the goal is quite obviously to raise some funds, and unless this group is the kind that engages in expropriations, you can skip discussions of strategy and go straight to talking about the tactic—what kind of fund-raising event you want to organize. Other topics are complex enough that articulating the goal, strategy, and tactics are essential. Again, depending on the complexity of the issue, the group may be able to incorporate goal, strategy, and tactics all into one decision, or you may need to go through entirely separate discussions, proposals, and decisions for each step.

NOTE: Some tactics are complex and ambitious enough to become goals in their own right, requiring a new set of strategies and tactics to implement them successfully. Most things can be viewed as one of three—as a goal, a strategy, or a tactic, depending on whether it is looked at in the context of long-term goals, short-term goals, or immediate projects.

Proposals

A proposal is a clearly articulated plan put before the group as a possible solution to the problem you are discussing. Both the timing and content of the proposal are crucial. Don’t make a proposal too early in a discussion, before all group members have gotten to speak their minds and consider the different ideas sufficiently, and also don’t wait until people have tired themselves out agreeing, saying the same things over and over again. It’s extremely important not to make a proposal when there are still serious disagreements, as this will only divide the group. The purpose is to synthesize everyone’s wants and needs; consensus is cooperative, not competitive like voting. With practice, you can begin to feel the perfect time for making a proposal—after disagreements have been discovered and amended, and group members are starting to agree on suggestions for a solution.

Not every discussion will lead to a proposal. Sometimes it becomes apparent that group members need to learn more before they make a decision, and the topic should be put off for a future meeting. At other times, disagreements are too serious to allow an effective synthesis, and group members will need more time to consider their positions and think about new solutions. A good consensus process ensures that the group is not forced into making decisions before it is ready.

If the group is ready to decide on a course of action, the proposal should be precise, inclusive, and fair. It needs to be stated clearly, and ideally restated by someone else in the group, so everyone has the same understanding of the proposal. Too often, a group goes through all the effort of a consensus decision only to find that there are multiple, conflicting interpretations of the decision. The proposal also needs to include as many group members’ wants, needs, and ideas as possible. It should be an expression of the agreements that culminate from the group discussion.

Once a proposal has been made, group discussion has to focus on that proposal until it has been voted on or withdrawn.

Changing the topic or making other proposals once a proposal is already on the table is distracting and makes progress difficult.

Questions

The first step after someone makes a proposal is to ask clarifying questions, to make sure everyone has the same understanding of the proposal, and to confirm background information that can help group members assess whether the proposal is a good one.

Concerns

After clarifying questions, group members should bring up concerns they have with the proposal at hand. Group discussion can help assess whether these concerns illuminate valid problems.

Friendly Amendments

If group members’ concerns with the proposals are focused on a small detail or a larger component, but are not disagreements with the entire proposal itself, either the proposer or anyone else in the group can suggest a friendly amendment. A friendly amendment is a mild modification of the proposal to address people’s concerns. If anyone disagrees with the friendly amendment, the proposal and any amendments need to undergo further discussion.

Withdrawals

If it becomes obvious that a proposal, or a friendly amendment for that matter, has serious shortcomings or disapproval, the proposer can withdraw it. A withdrawal means the proposal is no longer under discussion, and the group can return to brainstorming a better proposal. The point of a proposal is to come up with a decision the whole group can own, and if it’s clear that a number of other group members don’t like your proposal, you should withdraw it.

Voting

Once the proposal has been discussed to everyone’s satisfaction and no one appears to be staunchly opposed to it, anyone can call a vote, and as long as no one objects, the group should then vote. Someone should restate the proposal, especially if it has been amended or changed during the discussion, and field any last clarifying questions. Then you should ask if there are any blocks or any stand asides, and then ask who is in favor. As with the proposal, timing is important in taking a vote. Don’t call a vote if the room is tense or divided, and don’t call a vote before everyone has gotten a chance to discuss the proposal fully.

Blocks

The block is a very powerful action, and one of the things that makes consensus unique. Any one person in the group can veto a decision. Just give a thumbs down during the vote, and the group cannot adopt that proposal. Consensus is based on voluntary association. You cannot be forced to be a member of a consensual group, like you can be forced to be the subject of a democratic government. Because the rest of the group is associating with you by choice, they can’t force you to do anything you don’t want to do, and the group, with you as an integral part, cannot do anything you do not approve of.

Because the block is a serious power, it comes with serious responsibilities. Firstly, you have the responsibility to explain your reason for blocking the decision, and you have the responsibility to express your serious disagreement during the group discussion, before the proposal ever comes to a vote. If people are surprised when you block a decision, something did not happen the way it was supposed to.

Because of the tremendous impact of a block, you shouldn’t block unless you have a good reason. Consensus decision making cannot exist in a competitive, individualistic culture. You shouldn’t block a decision just because you didn’t like the proposal or thought your idea was better. You should block a proposal when you think it is a bad thing for the group as a whole to do. Consider it this way: if in your local Cop Watch group you want to publicize an instance of police brutality using a graffiti campaign, and everyone else wants to make flyers, the contradiction is simply a disagreement of preference. Ideally, your idea may be the better one, but practically you should recognize your idea won’t work out well if you’re the only one who is enthusiastic about it. The critical question should be, what is best for the group to do? The group can’t stop you from doing your graffiti campaign on your own ume, as long as it’s not in the group’s name, and if you’re not stoked about it you don’t have to help with the group’s flyering campaign. The point is that a large enough majority of the group wants to do it that it can be an effective action. You certainly can’t dictate to other people what is the best way for them to spend their time.

On the other hand, if you feel like a proposed decision would hurt the group, hurt people in the group, alienate the group from its base of support, or something like that, it is your responsibility to block the decision. You should also block the decision if you think that people in the group have seriously or intentionally manipulated the process to silence disagreement, or push their proposals through without legitimately addressing concerns. One person standing alone can halt the momentum of the other group members, who may have stopped considering other opinions simply because they’re in the majority. Our society certainly teaches people that might makes right. An effective block can give the rest of the group time to think about the situation from another angle.

If someone does block a decision, the group then needs to discuss whether to go back to the drawing board and work out another proposal, or drop the topic at hand, until another meeting or for good. Some may call this a disadvantage, but I consider it one of the unique strengths of consensus decision making: it allows the group to make no decision at all. With consensus, the highest priority is the health of the group, and allowing the group to not make a decision prevents minorities from having to go along with decisions they oppose. The failure to make a decision should not be stigmatized—it should be appreciated as a signal that the group needs to work more on finding common ground.

In some cases, a healthy group using consensus will never have a block, because group members communicate so well that no one will call a vote until all major disagreements have been worked out. On the flipside, other consensus groups never see anyone block a decision because less-involved group members are afraid to cause an inconvenience or contradict the group’s informal leaders.

If, on the other hand, people repeatedly block decisions, making it difficult for the group to accomplish anything, there are two possible problems. Perhaps certain members are still operating in an individualistic, competitive mode, and need to be confronted with this fact so they can decide whether to improve their behavior or find a group that better fits their beliefs. Another possibility is that yours is simply not a feasible group. An effective group needs to have common ground and good reason to work together. Can different group members even agree on a common purpose for the group? If not, it’s time for the group to break up, and its members to form more effective groups with people of shared interests. Likewise, if you find yourself at odds with everyone else in your group in terms of morality and worldview, perhaps the group isn’t the right one for you.

Stand Asides

If nobody blocks a decision, you should then see if anyone in the group chooses to stand aside. Signal a stand aside by putting your thumb out to the side, neither up nor down. If you personally don’t feel like the proposal on the table represents the best decision, or have other disagreements with parts of the proposal, but you still think it would be better for the group to use that proposal than to do nothing at all, you can stand aside. Also, if you don’t care to support the plan of action but you don’t mind if other people do, you can stand aside. If anyone does indicate a stand aside during the vote, you should find out why. It’s best to ask them if they feel like their concerns have been heard and addressed, and double-check that they are okay with the group accepting the proposal. If one or two people stand aside and those people feel like their concerns have been treated fairly, you’re doing fine! If a large portion of the group is standing aside, that’s a good indication that more involved group members have pushed a decision through without the participation or support of everyone else.

Thumbs Up

Once you have asked if anyone blocks or stands aside, even though that means that everyone else is technically in favor of the proposal, you should still go ahead and ask for thumbs up. Make sure that everyone votes one way or another. If you notice that someone did not vote, you ask why—and give them the benefit of the doubt. Maybe they felt intimidated.

If your consensus process is working well, you should know how everyone is going to vote before the vote is called. A major purpose of the vote is to allow formal group recognition of the proposal, and to require every single group member to personally express what they feel about the proposal before the decision is made. In groups with informal leadership in which a few more-involved people do all the talking and decision making while everyone else just sits and watches, the lack of enthusiasm and involvement by less-involved group members will be obvious—often they won’t even bother giving a thumbs up to indicate their approval.

For a consensus decision to be really valid, an overwhelming majority should be actively in favor of the decision. If a substantial number of people are standing aside, you may want to bring this up after the vote, and look towards improving group dynamics.

No Decision

If, after the end of discussion and voting, you don’t have a decision, don’t worry: it’s not the end of the world. It just means that in this case, making no decision was the best option available. What do you do now? If some people still want to take action on the issue, they can proceed autonomously in smaller groups, as long as they don’t go behind anyone’s back, use the group’s name, or do anything that could be counterproductive to the group’s other efforts. It’s not a dictatorship: we don’t have to get all our actions approved by the Central Committee. But at the same time it shouldn’t be a competition, so don’t do anything that will screw over your friends and allies.

Decision

So, the group has consensed on a decision! If it was a long and difficult process, everyone may feel stressed and worn out, but as long as the decision was made fairly, you should also feel accomplished and triumphant. But you’re not done yet: make sure to write down the decision that was consensed on, and make these records available to everyone through group notes or notes sent out over an e-mail list. It’s important to remember and keep a clear record of what the group consenses on, so you haven’t gone through all that work for nothing.

Why is Consensus so Difficult?

Consensus is not inherently more difficult than other forms of group decision making. It’s just a question of what we’re used to. In this society, very few decisions are up to us. The economy, the government, the media, schools and universities are all managed from above by secretive, exclusive groups of experts and specialists. The vast majority of decisions that are left up to us, mostly simple leisure and consumer choices, are highly individualistic, and don’t require any group process. Problem solving is mostly monopolized by the government, through courts, cops, politicians and social workers. Situations in which people do exist as part of a group are usually mediated by the government or some other hierarchy. There is always a boss, always a leader, always someone in charge, except in a few private settings, like interactions with friends.

In a society that treats us like incompetent, antisocial citizens/consumers/employees, our social skills atrophy like an unused muscle. Acting once again like competent, social beings requires a lot of tiring exercise. Rather than following orders or giving orders, in consensus you’re forming voluntary groups to decide new and flexible ways of organizing your lives and harmonizing your activities so that everyone’s needs can be met in a manner of their choosing. With enough practice, though, consensus begins to feel like second nature. Considering how empowering it can be to work with others as equals and begin reclaiming control of all the commodified, co-opted aspects of your life, the effort is well worth it.

NOTE: Your group does not need to formally consense on every decision. Some decisions can be made informally, without going through the whole voting process. The group has to make many minor decisions throughout the discussion itself as you proceed towards consensus. For example, everyone has to agree whether they’re ready to vote on a proposal, but it would be horribly inefficient to hold a vote on whether people are ready to vote on a proposal. Routine decisions, like when to hold the next meeting, can also do without full process. A good rule of thumb is this: If a decision is minor enough that the length of discussion will probably not take longer than going through a vote, than just consense informally by making a suggestion, looking for approval, asking if there are any objections, and moving along. If an issue is complex or controversial enough that the discussion will definitely take longer than the process of making a proposal and voting on it, it makes sense to use a formal, explicit consensus process. Otherwise, you may have to do it all over again if it turns out that there were objections or conflicting understandings of the informal decision.

Making Consensus Easier

Assigning Positions

Fortunately, there are plenty of tools to make consensus process easier. One crucial step is to assign important roles to different group members at the beginning of a meeting, to make sure the different critical tasks necessary to the process get done. Once someone volunteers for a role, they are not the sole authority on those tasks. Anyone else can choose to help out as well, but the person who volunteers is personally accountable for making sure those tasks get done. If you’ve volunteered for a specific job, it’s easier to remember to keep an eye on your responsibilities.

The following is a list of good roles that help to keep the group working smoothly. If your group is small, or well practiced at consensus, you may want to skip some of these roles. It’s also important, meeting to meeting, to make sure that different people are volunteering to take on different tasks. (You don’t want one person doing the same thing over and over—it tends to make the group dependent on that person, and it impedes others from learning the task in question.)

Note Taker

At any meeting, taking notes is a task you probably don’t want to skip. You need to be able to record group decisions, and inform people who missed the meeting about what was discussed. There’s no need to go into exhaustive details in the notes, but at a minimum you should record all the topics that were discussed, the announcements made, major concerns or criticisms raised, and decisions consensed on. If your group is engaged in potentially illegal actions or anything that may warrant legal sanctions, the note taker should be aware of the appropriate security practice, especially in terms of what never to write down, (and in more extreme circumstances whether to take any notes at all).

The note taker may be in charge of keeping the agenda, though in some groups this is the responsibility of the facilitator. The note taker is also responsible for making the notes available to the rest of the group sometime after the meeting, via copies or e-mail or whatever your group decides is best.

Timekeeper

If your group only has a limited amount of time for meetings, or wants to keep meetings from dragging on, you can agree on a certain number of minutes per agenda item when you’re writing up the agenda. A timekeeper is someone who uses a watch to let the group know when the time for a discussion topic is expired—it’s also good to give a heads-up a minute or two before the time is up, and to give periodic time checks during agenda items allotted more than fifteen minutes. When the time is up, the group moves on to the next agenda item, to ensure that everything can be covered before the meeting is over. If the group is still in the middle of a decision when the time runs out, someone can suggest an extension of another few minutes, and if no one objects discussion on the subject can continue.

Vibes Watcher

A vibes watcher is someone responsible for keeping an eye on power dynamics and vibes—emotional energy—within the group. This is an extremely important role in keeping the group healthy and functional. In majoritarian decision making, you win or you lose; your feelings don’t matter. With consensus, it’s the opposite. If people are feeling ignored, if someone is being domineering or manipulative, if people do not feel empowered within the group, their frustrations or submissiveness will become apparent, and it is up to the vibes watcher to interject and point this out so the group can deal with it in the open. It’s important for the vibes watcher to be sensitive enough to notice and interpret nonverbal emotional cues, and fair-minded enough not to take sides.

Authoritarian behavior, cliqueishness, oppressive dynamics like sexism or racism, frustration, sadness, confusion, disempowerment, or anger evidenced by several people or an individual, tension and hostility between different factions within the group—all of these are dynamics that the vibes watcher should point out, so the group can acknowledge them and deal with them. The vibes watcher is not interested in laying blame, or singling people out. It’s better to say “I’m noticing some frustration” than “So-and-so seems frustrated.”

Facilitator

The facilitator plays an extremely crucial role in any meeting that includes a substantial number of people not experienced with consensus process, or in meetings that bring together people from different backgrounds or people not used to working with one another. Groups with more experience working together gradually absorb the role of facilitator until each group member participates equally in facilitating the decision-making process.

The facilitator’s job is to make sure the group sticks to the agreed-upon decision-making process. This means striking a tricky balance between allowing plenty of flexibility and ensuring group efficiency. No one wants to have to follow a strict set of rules in a conversation, nor does anyone want to sit through a two-hour meeting in which discussion goes in circles, people keep changing the topic, and nothing gets accomplished. The facilitator isn’t there to make the trains run on time; a little chaos helps people relax and increases group creativity, but too much prevents the group from getting anything done.

As a facilitator, you’re given a certain amount of power. Don’t abuse it and impose your decisions on the group or favor the people you agree with. Before you decide a comment is “off topic,” make sure you don’t think so just because you disagree with what the person is saying. If you can’t be fair, or are too worn out to keep a clear head, step down and let someone else facilitate for the rest of the meeting. It is also the responsibility of the rest of the group to keep the facilitator in check, and give the facilitator feedback or criticism.

If a group isn’t having any problems coming to decisions on its own, the facilitator won’t have to do anything. If there are problems, the facilitator may need to step in. The following forms of intervention in the group discussion are appropriate: If no one in the group takes the initiative to start forming an agenda, the facilitator should ask for agenda items, and also ask if people have a preference for the order of the agenda items. If the group is discussing an agenda item, and one person starts talking about a completely different topic, the facilitator can bring the decision back to the topic at hand, or point out that the topic has changed and ask if the whole group wants to change topics, or finish discussing the first topic. If, during the discussion, someone starts bringing up tactics or action plans while other people are still asking questions and trying to get general information about the topic, the facilitator can suggest that not everyone is ready to begin discussing possible decisions. If someone interrupts another person in the group, the facilitator should point this out. If one group member makes a suggestion and everyone ignores it, the facilitator should encourage discussion of that person’s suggestion. If group discussion is going in circles, the facilitator should suggest moving forward. Sometimes it helps if the facilitator expresses an apparent consensus, when everyone seems to be saying similar things. If no one else in the group does so, the facilitator should make proposals, and conduct voting, when the time is ripe. The facilitator can also suggest go arounds, straw polls, or other discussion tools (which will be discussed later).

It is inappropriate for the facilitator to impose a discussion process that people disagree with. Any disagreement should be discussed before a decision is made. It is also inappropriate for the facilitator to provide an interpretation of how the group feels without giving group members the chance to agree or disagree. A good mantra to keep yourself in line, if you are facilitating a meeting, is “Open doors for equal participation. Help synthesize different ideas. Move towards a decision that everybody can own.”

To keep from strong-arming the group, it’s often best if the facilitator phrases comments about process as questions. Rather than saying: “That’s off-topic, so we can’t talk about it,“say “Do we want to move onto this topic, or finish what we were already discussing?” Don’t tell the group what to do, ask them what they want to do. This encourages group members to think more strategically and efficiently about the discussion, and returns power over the course of the discussion back to the group as a whole, away from the facilitator, and away from any individual who may try to change the topic or otherwise manipulate the discussion. Also, if the facilitator misses the relevance of a comment, or misinterprets what the group wants, using a question rather than an accusation can avoid undue tension.

Another effective tool of communication you can use as a facilitator is simply to express what you see happening. Oftentimes, people do not realize when they are being manipulative or counter-productive. Our society does not teach us to be effective and fair at communicating. Hearing other people describe our communication techniques helps us think about them. It can also be helpful to sum up what seems to be the common opinion, or to suggest a compromise or synthesis, when group members are just repeating one another or butting heads without having an actual disagreement.

There are a number of factors that can influence the role of facilitator. A major distinction is whether your group wants to use an involved or an uninvolved facilitator. An involved facilitator is a group member who participates in discussion and decision making, as well as fulfilling the facilitator role. An uninvolved facilitator is usually someone from outside the group who does not take part in discussion or decision making except to help the rest of the group make a decision.

Preferably, your group will not need outside help to facilitate meetings. However, some meetings are very difficult, and some groups too temporary, too large, or too inexperienced to have the necessary cohesion to come to decisions organically. With difficult meetings or incohesive groups, it can help to bring in an experienced, outside facilitator, someone who is not self-interested in what gets decided, only interested in making sure that consensus flows smoothly, and that the whole group is happy with the decisions.

Obviously, if one person facilitates meeting after meeting, that person will become an authority figure. Still, the need to rotate facilitators should be balanced with the need to have competent facilitators. Someone who is not ready to facilitate a group meeting, but does so because he thinks it’s a minor task or has been pressured into taking on the role because “it’s his turn,” will lose confidence in his abilities, and will also hurt group dynamics, as the others fall back into informal leadership patterns as an easier alternative to confronting the poor facilitation and helping the facilitator better learn his role. Your group should make a definite effort towards helping everyone become experienced facilitators (at which point no one facilitator is needed, and spontaneous or informal consensus becomes practical). Break in less-experienced facilitators with easier meetings, reserve time to give newer facilitators helpful feedback, provide workshops and discussions on good facilitation techniques, and in the meantime let the better facilitators pick up some of the slack, as long as they understand that their role is to fade back into the group as quickly as possible. Their experience is only helpful to the group if they pass it on, rather than hold onto it for themselves.

Stack Taker

A stack is simply a list of people who are next in line to speak. Sometimes there is no need for a stack, but when you have multiple people trying to speak at once, it helps if the facilitator asks people to raise their hands. The person who volunteered at the beginning of the meeting to be stack taker then begins making a list, writing people’s names down in order of who raised their hand first. When one person is done speaking, the stack taker then says whose turn is next. Small, informal, well acquainted groups do not need a stack anymore than do groups of friends, but a group wishing to expand beyond a clique can make room for equal participation with a stack.

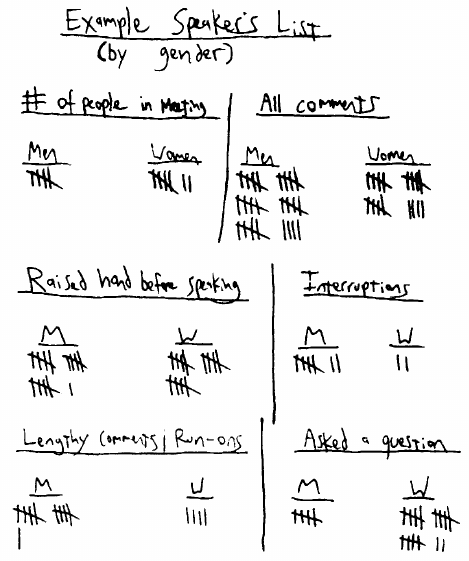

At certain points in a meeting, like brainstorming sessions, the group may explicitly wish to do away with the stack. At other times, there are many options for how exactly the group uses a stack. Should you use a straight stack or give priority to the less vocal? For example, some groups create a gendered speakers’ list, meaning that every time a man is added to the stack, a woman must be next. Gender-balanced stacks can help groups with pronounced sexist dynamics be more mindful of male domination or unequal participation, but they can entrench gender binary or otherwise rigid segregation of people with different gender identities. Gender-balanced stacks can also be mistaken as a solution to gender inequality in meetings, and allow group members to avoid thinking about, and fail to solve, the underlying causes of unequal participation. The ultimate goal should be a group in which people notice and equalize gender dynamics on their own.

Groups that have problems with run-on speakers can impose time limits for each person on the stack, but this is also a temporary solution that can create the same problems as gender-balanced stacks. Other groups may decide that no one can get on the stack a second time until everyone has been on once, or more flexibly, that no one can speak three times until everyone has spoken. A helpful tactic to increase the group’s awareness of unequal dynamics without imposing any rules is for the stack taker to read every name on the stack at the end of the meeting. If a particular individual is speaking more often than everyone else, this will become quite apparent when the stack is read off. The stack taker should be able to conduct the stack in whatever way the group decides is best.

Hand Signals

To “affirm,” extend one or both hands and wiggle all your fingers up and down (sometimes referred to as “twinkling”), give a “thumbs up,” or visibly nod. Affirming means you agree with what someone is saying. It takes the role of clapping or snapping your fingers, which can make it hard to hear and encourages speechifying. Affirming is very helpful, because it lets everyone know when an idea is popular, and can proceed towards consensus. No one wants to sit around and listen to a whole line of people say “I agree with what so-and-so says,” but on the other hand, consensus means that everyone’s opinions are essential to the process. Affirming allows people to express supportive opinions without wasting time on duplicate comments.

There should be no complementary gesture of disagreement, for two reasons. First, it can be very intimidating to someone if they start talking and everyone starts shaking their heads or giving a thumbs down—it’s almost as bad as being interrupted, and less-confident people especially will stop sharing their idea if they see signs of disapproval. Secondly, if you disagree with a comment, you need to explain to the group why you disagree. There is no comparable negative hand gesture, because people who disagree should just raise their hand and get on the stack.

Process Point

You signal a process point by making a triangle with the thumb and index finger of each hand. The process point is one of two hand signals that can bump you to the top of the stack. Even if five people are waiting to speak when you signal a process point, you are the next one to speak. This means that you need to be very careful about using process points. Process points must be substantive comments about discussion process, not personal opinions, announcements, or discussion topics. Important comments about group vibes (e.g., “So-and-so just got interrupted” or “There’s a lot of hostility here we should deal with”) or time limits (e.g., “We’re over the agreed time for this topic”), whether or not they are made by the assigned vibes watcher or timekeeper, can be process points.

Comments correcting the discussion process can also be made as process points. For instance, if one person makes a proposal and another person changes the subject or continues discussing the topic without acknowledging the proposal; or if people keep changing the topic; or if someone makes a decision for the whole group without allowing a vote, make a process point and express what happened. If you are the facilitator, it’s your job to make comments like that, so you can speak up without making the hand signal, unless your group has decided that they want the facilitator to act like any other group member.

Direct Response

Signal a direct response by making a gun with your hand and pointing at the person you wish to respond to. A direct response is the other hand signal that bumps you to the top of the stack, so use it responsibly. Again, no opinions. Use a direct response to offer corrections, in case someone reports some information that is not true. Make sure you’re offering a correction only if it is a matter of solid facts, and not just a differing interpretation of facts. You can also give a direct response to offer clarifying information. It’s best to do this only when someone else has asked a question, and you have more relevant information about it than other group members. It is also acceptable to use a direct response if someone says something you don’t understand and want to ask a clarifying question.

Other Signals

There are also hand signals for voting: thumbs up, thumbs down, and stand aside, which have already been discussed. Your group can come up with other hand signals as needed. Be prepared to come up with back-up signals for people who are not able to use their hands, or do not have hands.

Nonverbal Language

It’s important to remember that not all language comes in words. Nonverbal language—body posture, hand signals, facial expressions, expressive sounds like sighs or laughter— can have a critical impact on the collective mood and the effectiveness of the group. It would be absurd to suggest we should try to be “positive” all the time. Never try to hide your feelings, just express them in a constructive way that makes it easy for problems to be dealt with. If you are frustrated, or don’t like what someone is saying, don’t do things that could increase hostility or make people feel stupid, like rolling your eyes, groaning, fidgeting impatiently, yelling, et cetera. Expressing discontent should be encouraged, but don’t do it in a bullying way.

Changing the Format of Discussion

No two people communicate in the exact same way. While some forms of communication are counterproductive or hurtful, there is no single right way to communicate. But there are good ways and bad ways. Your group can embrace multiple healthy styles of communication by using multiple discussion formats within a meeting. You can’t find one compromised style that suits everyone, so change up! Here are some discussion formats that your group can incorporate in addition to the linear, goal-oriented format that has been described so far. The linear style can help your group progress towards an effective decision, and these other styles can be used along the way to encourage greater participation and new ways of thinking.

Step Forward, Step Back

Especially when a discussion is being dominated by more assertive group members, the facilitator, or anyone else, can ask people to step forward and step back. What this means is that people should honestly assess whether they are someone who is comfortable speaking or if they are someone who does not contribute much to group discussions. People who identify themselves as more talkative should then hold their tongues and think twice before they decide to take up the group’s time with a comment. Less talkative people are responsible for trying to contribute more to the discussion. Calling for a step forward, step back reminds people of their responsibilities and allows them to improve their own behavior. It also increases awareness of unequal participation in the group. If you can’t honestly admit, for example, that you take an unequal amount of space during discussions, and you continue to talk disproportionately after someone has called for a step forward, step back, then your inability to make yourself accountable to the group will become more obvious to those around you. Alternately, if you continue to be quiet during group discussions, other group members may be encouraged to look for more entrenched dynamics that keep you silent, or to try to get to know you better and find out if you’re not just someone who would choose to be quiet even in a perfectly egalitarian society.

Moment of Reflection

Guess what? Not everyone can think of things to say at the drop of a hat. Often, silence is fertile ground for new thoughts. Especially in difficult, fast-paced meetings, you can call for a moment of silence. This helps to relieve stress, give slower people more time to think (and thus participate), and allow clarity in a tense or confused moment. And just like counting to ten after someone insults you, a moment of silence can defuse strife and prevent an argument.

Even when your group isn’t using a moment of silence, silence can be helpful. For example, if you’re a quick thinker and speaker, try to leave a second or two of silence after someone finishes speaking before you start speaking. Hold on to your thought, make sure it is important, look around and see if anyone else is also about to speak. A rapid-fire conversation with no pauses can be very intimidating for people who are less assertive.

Go Around

On the other hand, too much silence can be suffocating! Sometimes, no one has any ideas they want to share. At other times, the more assertive people in a group might feel guilty for talking all the time, so they keep quiet. But if the people who are usually responsible for keeping discussions moving stop talking, less-assertive group members may feel even more uncomfortable speaking up. In any of these situations, you can suggest a go around. One person, usually the one who suggested it, starts by sharing their thoughts and feelings for a few seconds to a minute. Then the next person shares, and the next person, until everyone has spoken. A go around helps break the ice, bring out new ideas, or reveal how the entire group feels about an issue.

In other situations, doing a go around can be counterproductive. If the group is divided on an issue, facing high tensions or a possible argument, a go around may only draw party lines and encourage majoritarian competition, especially in larger groups.

Partnering

In situations of tension or conflict, a good tactic can be partnering. Simply call for partnering, and if no one objects, group members split up into small groups of two or three to talk. The fewer people there are, the more each person gets to talk. Partnering helps explore complex ideas or controversies, and allows you to see other points of view and work out a compromise. It’s easier to get in a fight with someone the farther away from you they are—being face to face encourages cooperation. At the end of the partnering, it may be a good idea for each pair to report back to the whole group the highlights of what they discussed.

Fishbowl

A fishbowl allows a group to explore a contentious topic that has divided the group into multiple sides or opposing camps. The different sides choose representatives to advocate their positions. The larger group remains on the outside, in a circle, observing as the representatives of the two or more opposing sides meet in the middle to work out the disagreement. They may come to a compromise themselves, or they may debate until the group as a whole is won over to one side or the other. The fishbowl has the advantage of allowing for greater detail and continuity than is usually possible in large group discussions, which can be helpful in evaluating solutions to difficult questions. The fishbowl also recognizes that a group may factionalize during certain disagreements, despite efforts to maintain a constant air of reconciliation, unity, and consensus. On the downside, fishbowls can be highly competitive, and can increase the influence of more articulate group members while disempowering those who are not confident debaters. Fishbowls can elevate debate above mutual understanding, and they can give more importance to the effectiveness of someone’s rhetoric than to the merits of the position they are advocating.

Brainstorming

If your group is stumped on a particular problem, or wants to encourage a highly creative solution, it can help to put the linear discussion on hold and do some brainstorming. It works best when everyone gathers close together around a sheet of paper or chalkboard, on which someone will write down every idea that gets tossed out. For simple decisions, like picking a name or the wording for a banner, just do a “shout-out” or a “popcorn.” As soon as you think of something, shout it out, until the group’s creative energies crescendo and everyone is tossing out ideas, like popcorn. Ideally, when you’re all done a suggestion that everyone likes will be right there, written down on the piece of paper.