Dedication: In Memory of Max Nettlau, 1865–1944

Paul Avrich

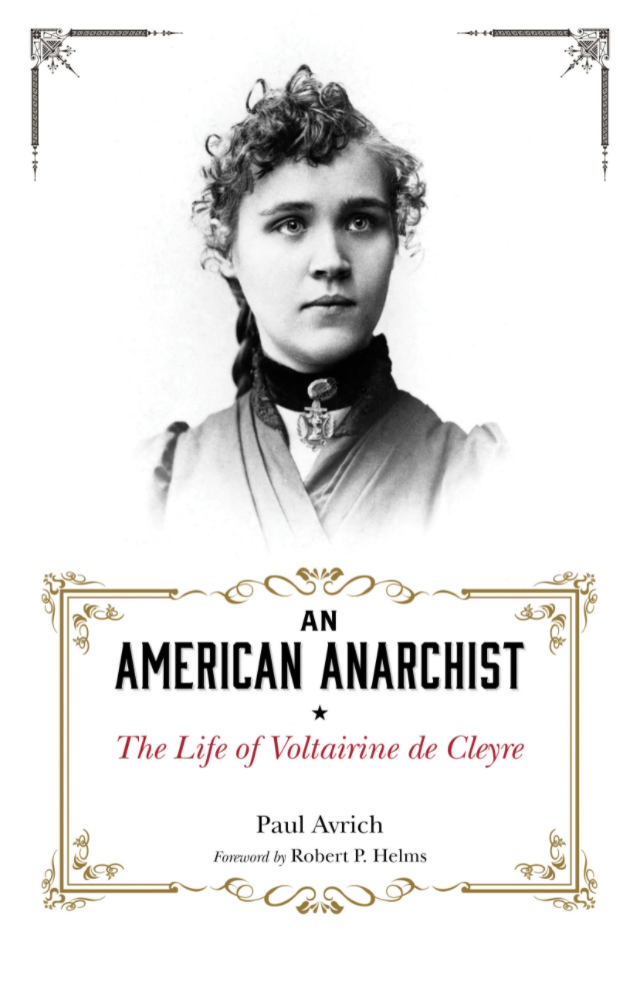

An American Anarchist

The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre

Foreword to the 40th Anniversary Edition of An American Anarchist

In 1990, I walked into a tiny anarchist bookstore and found a rare copy of An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre by Paul Avrich. I knew de Cleyre only as a figure mentioned in Avrich’s later book The Haymarket Tragedy. Because I relished Avrich’s writing already, because I had the enthusiasm of a recent convert to anarchist thinking, I could hardly wait to read de Cleyre’s biography.

Avrich presented to his readers the depth and intensity of this intellectual powerhouse who repeatedly made sacrifices and endangered herself in order to stay true to her principles, which she never once compromised for her own safety’s sake. De Cleyre pressed her cause when anyone else would have dropped the activism due to poverty and sickness. No one, living or dead, could introduce her as well as Paul Avrich does with this biography, which is as inspiring to readers as Emma Goldman’s Living My Life or Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed. Avrich’s books are as readable as novels, and de Cleyre’s life is what you’re about to discover.

De Cleyre remains today one of the most inspiring of all the early-American anarchists, including the notorious few, such as Emma Goldman or Johann Most, and the less known but equally remarkable, like educator Joseph J. Cohen, editor Abraham Isaak, or the almost completely forgotten poet-essayist Viroqua Daniels.

In contemporary descriptions, Voltairine de Cleyre is striking for her intellectual powers, her intense empathy and love for suffering people and animals, and her particular charisma. Her writings carry the entire range of human experience—curiosity and profound wonder in her earlier years, then more sorrow and bitterness as she grew older. In an interview, Avrich said de Cleyre was “a fascinating person. I read her poetry and stories and found a sadness in her.” He succeeded in rescuing this brilliant and compelling person from near non-existence, and because of his work we too are moved by her words, we imagine her voice and self, and we are energized by her courage.

Paul Henry Avrich was born in Brooklyn, New York on August 4, 1931, growing up in the Crown Heights neighborhood with his sister Dorothy. His parents, Murray, the owner of a small dress manufacturing company, and Rose Zapol Avrich, were Jews who had emigrated from Odessa. Avrich was educated in public schools and completed a Bachelor of Arts degree at Cornell University in June 1952, having started there at age sixteen on a scholarship. He then joined the military, which sent him to Syracuse University to study Russian.

In 1959, Avrich was one of twelve American students chosen to go to Russia in a special exchange program, and he spent three months in the archives of the Lenin State Library in Moscow, reading the records of factory workers’ committees and the sailors’ uprising at Kronstadt. Here was where he first discovered anarchism, and these early research endeavors in Moscow developed into his doctoral dissertation at Columbia University and then into his pioneering books, The Russian Anarchists, The Russian Rebels, and Kronstadt 1921, which are still definitive texts on anarchism in Russia. Avrich began teaching at Queens College of the City University of New York in 1961 and remained there until his retirement in 1999. Karen Avrich describes her father as “an intensely disciplined man, working seven days a week, usually in his small study at the back of the family apartment on Riverside Drive. It was a somewhat Spartan space, holding a plain desk, piles of books and files, and stacks of yellow pages covered in his slanting, looping longhand. There was no television or radio playing, no art on the walls; the window looked out onto a glum section of courtyard. The only occasional distraction, a cat sprawled across the desk, tail swishing deliberately through sheaves of paper.”[1]

Paul Avrich spoke several languages, including Yiddish, Russian, French, German, Italian, and his native English. He could also read, with varying degrees of difficulty, other European languages. He held that serious, reliable scholarship could not be done by anyone lacking a command of the language of the subject.[2] We might measure the extent to which Avrich was right by the gigantic footprints he left in the study of anarchists who spoke and wrote in these particular languages.

In the generation of Voltairine’s admirers before Avrich, Joseph Ishill communicated with several of her friends and associates with a view to publishing all of her extant writings, as was her dying wish. Receiving a batch of her letters from the Scottish anarchist Will Duff, Ishill extracted parts for publication “without discrediting either Voltairine’s name or that of the comrade to whom they were addressed.” Duff continued, to Saul Yanovsky in 1930, “If I were to use them as they originally appear it would of course be a gauche affair, an irrational piece of work which only an ignoramus or an enemy of her ideas could perform. My sense of fairness and justice to Voltairine demand that her work be well represented in the eyes of those who still cherish her revolutionary interpretations.”[3]

Likewise, Avrich chose not share de Cleyre’s abortion in 1897, which she described in a private letter, another part of which is quoted in the present volume. Also unmentioned is de Cleyre’s syphilis[4] and that Thomas Hamilton Garside, her lover, was exposed as an undercover Deputy US Marshall not long after he deserted the young de Cleyre.[5]

An American Anarchist includes a discussion of de Cleyre’s mentor, Dyer D. Lum, the older and respected anarchist thinker who died as Voltairine was emerging as an important anarchist writer. Later scholarship tells a more shadowed backstory of depression, serious alcoholism, and more racism than we can ignore.[6] Also, their relationship was almost entirely intellectual, but in Lum’s mind there was a sexual angle that did not exist in de Cleyre’s. It was de Cleyre’s writings on Lum that insured him a substantial readership after his death.

In 1978 when An American Anarchist was first published, several of de Cleyre’s friends and grandchildren remained alive and were sensitive to painful items in the her story. Paul Avrich chose to write respectfully of his subject and the movement of which she was a part. Forty years later, with de Cleyre’s contemporaries gone, we can learn about parts of her life that were hitherto concealed.

Very few readers of English recognized the name of Voltairine de Cleyre when An American Anarchist first appeared. Since then, however, there has been an increasing interest in her life and work. A steady stream of articles, pamphlets, and small books have also been published in several languages—not just scholarly tracts but others written to support current activism, or to share anarchist or feminist ideas. Nearly all of de Cleyre’s known published writings are now available on the internet and several long-lost writings have come to light—some of which are quite important. Five anthologies have been published, the recent four informed almost entirely by Avrich.[7]

Little or none of this would have happened without the influence of this book. Such is the stature of Paul Avrich among historians of anarchism: he breathed life into the dead, whose voices now command unique and considerable attention.

Philadelphia

Robert P. Helms

September 2017

Preface

This biography of Voltairine de Cleyre, one of the most interesting if neglected figures in the history of American radicalism, is designed to be the first of several volumes dealing with anarchism in the United States, a project on which I have been engaged for the past six years. When I began my work, I expected to treat the entire subject between the covers of a single volume, in which Voltairine de Cleyre would occupy a modest place. My intention at the time was to produce a comprehensive history of American anarchism from its seventeenth-century origins until recent years, embracing the individualists and collectivists, the native Americans and immigrants, the pacifists and revolutionists, and their libertarian schools and colonies.

A study of this type was badly needed. For while there were a number of useful works on American socialism and American communism, the history of American anarchism remained largely unwritten. Two well-known surveys of anarchism as a whole, George Woodcock’s Anarchism and James Joll’s The Anarchists, contained brief accounts of the movement in the United States, in addition to a longer discussion by Max Nettlau in his multivolume history of anarchism, written half a century ago but never published in its entirety. On American anarchism itself most available studies were tendentious and unreliable. There were, however, a few creditable works, such as Eunice M. Schuster’s pioneering Native American Anarchism, which, if largely out of date, was still of some value, and James J. Martin’s Men Against the State, an authoritative treatment of the Individualist school, of which Josiah Warren and Benjamin Tucker were the outstanding exponents. Moreover, one of the leading Anarchist-Communists, Emma Goldman, had been the subject of a sympathetic biography by Richard Drinnon, Rebel in Paradise, in addition to which The History of the Haymarket Affair by Henry David and The Mooney Case by Richard Frost merited special attention. But much remained to be done, particularly on the immigrant groups; and in many areas scholarly explorations were completely lacking, sources uncollected and often unknown, and historical works, with few exceptions, encrusted with political and personal bias.

It was considerations such as these which led me, at the beginning of the 1970s, to contemplate the writing of a general history of American anarchism. At an early stage, however, my plans began to alter. For a fuller examination of the materials at my disposal, together with the discovery of new sources, aroused a growing sense of the complexity of the movement, of the richness and diversity of its history. Again and again, I encountered important figures begging to be resurrected, tangled episodes to be unraveled, neglected avenues to be explored—too many, it was clear, to be treated in a single volume. A larger design was required to do the subject justice and to incorporate the findings of such recently published works as Lewis Perry’s Radical Abolitionism and Laurence Veysey’s The Communal Experience, which have filled conspicuous gaps in our knowledge of American anarchism and enabled us to begin to separate historical legend from historical reality. To a significant extent, moreover, the need for a general history was met in 1976 with the publication of William O. Reichert’s Partisans of Freedom: A Study in American Anarchism, a work of 600 closely printed pages with useful bibliographical references.

I found myself, as a result, less and less inclined to produce an exhaustive chronological history of American anarchism. Besides, as my work progressed it became increasingly evident that much of what had happened in the movement had been due to the personal characteristics of its adherents, and that the nature of American anarchism might be profitably explored through the lives of a few individuals who played a central role in the movement and set the imprint of their personalities upon it. From most existing accounts, unfortunately, one gets little understanding of the anarchists as human beings, still less of what impelled them to embark on their unpopular and seemingly futile course. Anarchism, as a result, has seemed a movement apart, unreal and quixotic, divorced from American history and irrelevant to American life.

For these reasons, I have decided to tell the story of American anarchism through the lives of selected figures who, in large measure, shaped the destiny and character of the movement. In arriving at this decision, I have been guided by the assumption that by focusing on key individuals, their dreams and passions, failures and successes, weaknesses and strengths, I can make the movement as a whole more comprehensible. I have not, however, ignored the social and economic developments of the age, but have tried, as the story unfolds, to include sufficient historical background to make the lives of the anarchists intelligible.

Of all the major movements of social reform, anarchism has been subject to the grossest misunderstandings of its nature and objectives. No group has been more abused and misrepresented by the authorities or more feared and detested by the public. And of all the misconceptions of anarchism, the one that dies the hardest is the belief that it is inseparable from assassination and destruction. There were, to be sure, individuals and groups among the anarchists who were ready to commit acts of terrorism. Yet, for all the notoriety that they achieved, they occupied a relatively small place in the movement. By the time of the First World War, however, anarchism had acquired a reputation of violence for its own sake that the passage of six decades has failed to alter. The stereotype, once created, has been endlessly recopied, so that to this day the association of anarchism with terrorism, with bombs, dynamite, and chaos, remains deeply embedded in the popular imagination.

But who in fact were the anarchists? What did they actually say and do with regard to economic, social, and political issues? How did they cope with popular abuse and with official harassment and repression? How did they react to problems, both social and personal, which confronted them at different stages of their careers? What did they want and what did they achieve? Such are the questions this study will try to answer. Every effort will be made to portray the anarchists as they really were, rather than as they have appeared in the fantasies of policemen and journalists and not a few historians, who have neglected to look up the sources from which any reliable study must be made.

Anarchism has been defined as “the philosophy of a new social order based on liberty unrestricted by man-made law; the theory that all forms of government rest on violence, and are therefore wrong and harmful, as well as unnecessary.”[8] As such, it will be seen, it was not an alien doctrine, but an integral part of the American past, deeply rooted in native soil; and though an organized anarchist movement did not emerge in the United States until the 1870s and ’80s, the belief in a minimum of government, as one writer has noted, had been “a fundamental article of faith of the new nation.”[9] Indeed, an American libertarian tradition runs back to the seventeenth century and continues to the present day. The vision of a stateless utopia may be discovered among the religious and political dissenters of the colonial era as well as among the anti-slavery followers of William Lloyd Garrison and the communitarian enthusiasts of the antebellum period. It may also be found in the writings of Emerson, Thoreau, and other nineteenth-century figures, both well-known and obscure. “Why should I employ a church to write my creed or a state to govern me?” asked Bronson Alcott in 1839. “Why not write my own creed? Why not govern myself?”[10]

Sentiments such as these, at bottom a response to the quickening pace of political and economic centralization brought on by the industrial revolution, were by no means uncommon among New England transcendentalists and reformers. Josiah Warren, who has been called “the first American anarchist,” began to evolve a coherent libertarian philosophy as early as the 1820s, while identifiably anarchist colonies can be traced back to the 1830s and 1840s, if not earlier. And with the upsurge of centralized power after the Civil War, a vigorous anarchist movement took shape, spreading across the country from Massachusetts to California. During the early 1870s, Bakuninist sections of the International Working Men’s Association were established in Boston, New York, and other cities, and Americans at this time began to take part in international anarchist congresses. The influx of immigrants during the succeeding decades provided the movement with a fresh supply of recruits, and anarchist groups sprang up in every part of the country except the deep South.

In most locations these groups fell into three categories: Anarchist-Communists, who envisioned a free federation of agricultural and industrial cooperatives in which each member would be rewarded according to his needs; Anarcho-Syndicalists, who pinned their hopes on the labor movement and called for workers’ self-management in the factories; and Individualist Anarchists, who, distrusting any collaboration that might harden into institutional form, rejected both cooperatives and unions in favor of unorganized individuals, exalting the ego above the claims of collective entities. To these might be added the Tolstoyan and pacifist anarchists, who spurned all revolutionary activity as a breeder of hatred and violence.

Communists and syndicalists, pacifists and revolutionists, idealists and adventurers—the American anarchist movement encompassed a fascinating and often contradictory variety of groups and individuals, whose activities ranged from strikes and terrorist attacks to the dissemination of birth-control propaganda and the creation of libertarian schools. Yet, however they might differ on such questions as violence and organization, they were united in their rejection of the state, their opposition to coercion, and their faith that people could live in harmony once the restraints imposed by government had been removed. In spite of personal and factional disputes, they shared a common determination to make a clean sweep of entrenched institutions and to inaugurate a stateless society based on the voluntary cooperation of free individuals, a society without oppression or exploitation, without hunger or want, in which men and women would direct their own affairs unimpeded by any authority.

This vision, to all appearances, differed little from that of the Marxists: a world in which the free development of each was a condition for the free development of all and in which no man would be master of his brother. The Marxists, however, did not regard the millennium as imminent. They foresaw an intervening stage of proletarian dictatorship that would eliminate the last vestiges of capitalism. The anarchists, by contrast, were opposed to the state in any form. Refusing to temporize with political or economic power, they poured contempt on intermediate stages, partial reforms, and palliatives or compromises of any sort. The existing regime was rotten, and salvation could be achieved only by destroying it root and branch. Moreover, political revolutions were useless, for they merely exchanged one set of rulers for another without altering the essence of tyranny. Instead, the anarchists called for a social revolution that would abolish all political and economic authority and usher in a decentralized society of autonomous communities and labor associations, organized “from below,” as they put it.

Anarchism, however, did not become a creed of the mass of industrial workers. For reasons which will be explored, it was destined to remain a dream of comparatively small groups of men and women who had alienated themselves from the mainstream of American society. Yet they claim our attention, not only as a collection of colorful personalities, but as social and moral critics whose voices should not go unheard. They foresaw the negative consequences of “scientific” socialism and offered a continuous and fundamental criticism of all forms of centralized authority. They warned that political power is intrinsically evil, that it corrupts all who wield it, that government of any kind stifles the creative spirit of the people and robs them of their freedom. And, notwithstanding their small popular following, they played a significant part in American history and had a deep and abiding effect on American life.

Since no attempt was made to keep records of membership (anarchists issued no “party cards” and distrusted formal organizational machinery), the numerical strength of the movement is hard to determine. But it was greater than has generally been supposed. Scattered across the country, with concentrations in the larger cities, anarchists reckoned in the tens of thousands at the crest of the movement between 1880 and 1920, with 3,000 in Chicago alone during the last decades of the nineteenth century and comparable numbers in Paterson and New York. The Union of Russian Workers in the United States and Canada, in which anarchists formed the largest element, boasted 10,000 adherents on the eve of its suppression in 1919 by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer.

To spread their libertarian message, anarchists in the United States issued nearly 500 periodicals in a dozen languages, several of which ran for decades and achieved a high level of literary distinction, including Benjamin Tucker’s Liberty, Johann Most’s Freiheit, and Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth. The Italian L’Adunata dei Refrattari endured for half a century, while the Fraye Arbeter Shtime, whose circulation exceeded 20,000 in the period before the First World War, is still in existence after eighty-seven years, the oldest Yiddish newspaper in the world. Anarchist influence was also exerted through active participation in trade unions and cooperatives, while the execution of the Spanish educator Francisco Ferrer in 1909 led to the formation in America of more than twenty anarchist schools on the model of his Escuela Moderna in Barcelona. One of these, at Stelton, New Jersey, survived for forty years, closing in 1953. Anarchists, it might be added, were involved in two of the most dramatic and controversial trials in American history, the Haymarket affair of the 1880s and the Sacco-Vanzetti affair of the 1920s, both of which had international repercussions, providing a rallying-point for radicals and liberals throughout the world. In short, a study of American anarchism is essential to an understanding of such subjects as labor and immigration, pacifism and war, birth control and sexual freedom, civil liberties and political repression, prison reform and capital punishment, avant-garde culture and art. In a larger sense, a study of American anarchism will shed interesting light on the nature of American democracy, American capitalism, and American government.

What began then as a chronological survey has become a series of interrelated studies which, taken together, will form a kind of biographical history of a movement that included figures as striking and diverse as Josiah Warren and Alexander Berkman, Benjamin Tucker and Johann Most, Emma Goldman and Voltairine de Cleyre. By assigning Voltairine de Cleyre a separate volume, I do not mean to overstate her importance. Yet for twenty-five years she was an active agitator and propagandist and, as a glance through the files of the anarchist press will show, one of the movement’s most respected and devoted representatives, who deserves to be better known. Besides, there was so much rich drama in her life that a full-length biography was needed to do it justice. As a freethinker and feminist as well as an anarchist, moreover, she can speak to us today, across a gulf of seven decades, with undiminished relevance. For, in a remarkably detailed and articulate fashion, her writings anticipate the contemporary mood of distrust toward the centralized bureaucratic state. She was one of the most eloquent and consistent critics of unbridled political power, the subjugation of the individual, the dehumanization of labor, and the debasement of culture; and with her vision of a decentralized libertarian society, based on voluntary cooperation and mutual aid, she has left a legacy to inspire new generations of idealists and reformers.

Much of the documentation on which this biography is based has been hitherto unknown or unused. At every stage it has been necessary to reconstruct the story from primary sources—letters, memoirs, journals, oral testimony, and bits of information pieced together by other means. I have tried to approach these materials directly and to reach my own conclusions, even when some aspect of the subject has been touched upon in a secondary work not marred by prejudice or ignorance. While it is the first of a series of studies, this volume is a self-contained biography, complete in its own terms, which can be read as an independent work. To some extent, however, it bears the character of a stage of a larger enterprise, in that several strands of narrative and interpretation will be taken up and expanded in future instalments.

It may be useful, finally, to indicate how the present series fits into my overall program of research. My work on the history of American anarchism, begun in 1971, will form part of a still larger investigation of libertarian movements with which I have been occupied since my graduate years at Columbia University from 1957 to 1961. My research at Columbia began with a study of the factory-committee movement during the Russian Revolution, a form of revolutionary syndicalism in which rank-and-file workers assumed control of their factories and shops. This led, in turn, to a general history of Russian anarchism (published in 1967) and to related histories of the Kronstadt rebellion of 1921 and of popular risings in Russia during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

I have not, in the intervening years, changed the direction of my research, but have broadened its scope to include the United States and other countries. When the American volumes are completed, I hope to turn to anarchism in Europe and Asia, and also to a history of the forerunners of anarchism from ancient times to the French Revolution. With regard to the United States, my training in Russian and European history, while it presents a number of difficulties, may also have certain advantages. For it has been necessary to delve into the European roots of American anarchism, especially of the numerous immigrant groups that were formed during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Such an approach, one hopes, will contribute not only to our knowledge of American anarchism itself, but of anarchism as a worldwide phenomenon between the French Revolution and the Spanish Civil War, and beyond.

During the course of my research on American anarchism, which is now largely completed, I have visited more than fifty libraries and archives in Europe and the United States, the most important of which are listed in the bibliography of this volume. To the staffs of these institutions, and especially to Rudolf de Jong, Thea Duijker, and Maria Hunink of the International Institute of Social History, Edward Weber and Helen Jameson of the Labadie Collection, Dorothy Swanson and Debra Slotkin-Shulman of the Tamiment Collection, Hillel Kempinski of the Bund Archives, and Laura V. Monti of the University of Florida, I am grateful for their kind assistance.

A subject such as this, however, especially when approached from the angle of biography, cannot be studied from documents alone. Personal contacts are essential, and I am fortunate in this regard to have come to know many of the survivors of the anarchist movement, who have allowed me to attend their meetings, to inspect their manuscripts and correspondence, and to discuss with them, at considerable length, points of mutual interest relating to anarchist history. By revealing the inner recesses of anarchist life as perhaps no other sources can, these contacts have done much to broaden and deepen my knowledge of the subject. Over the years, moreover, I have conducted more than 150 interviews with these survivors, each adding valuable details or a fresh point of view. Together, these interviews provide a unique account of the movement in the words of the participants, and in due course I shall deposit bound transcripts in major libraries for use by other students of anarchist history.

With regard to my work on Voltairine de Cleyre, I am much indebted to several individuals who placed important materials at my disposal: William Morris Abbott, Marion Bell, Renée de Cleyre Buckwalter, William J. Fishman, Elmer Isaak, Rose Lowensohn, George H. O’Brien, Sidney E. Parker, and Grace Umrath. In addition, I have greatly profited from interviews and conversations with a number of people who knew Voltairine de Cleyre, heard her speak at meetings, or had other contacts with her and were willing to share their recollections with me: Rebecca August, Marion Bell, Zalman Deanin, Gussie Denenberg, Nellie Dick, Sam Dreen, Morris Gamberg, Emma Cohen Gilbert, Jeanne Levey, Harry Melman, Shaindel Ostroff, and Boris Yelensky.

Others who have aided me in different phases of my work, including the furnishing of information and the reading of the manuscript, are Irving Abrams, Sally Axelrod, Roger Baldwin, Fedora de Cleyre Benish, Morris Beresin, Eva Brandes, Emanuel V. Conason, Franklin de Cleyre, Hertha de Cleyre, Lincoln de Cleyre, Sonya Deanin, Richard Drinnon, Beatrice Schumm Fetz, Franz Fleigler, Charles Hamilton, Jack Frager, Millie Desser Grobstein, Anatole Freeman Ishill, Sophia Janoff (Yanovsky), Sonia Edelstadt Keene, Crystal Ishill Mendelsohn, Vladimiro Muñoz, Oriole Tucker Riché, Fermin Rocker, Ma Schmu, Ray Miller Shedlovsky, Clara and Sidney Solomon, Ahrne Thorne, and George Woodcock.

My exploration of the relevant archives was facilitated by a grant from the Research Foundation of the City University of New York and by a National Endowment for the Humanities Senior Fellowship for the academic year 1972–1973. The responsibility for this volume, however, is entirely my own.

New York

P. H. A.

June 1977

An American Anarchist

The life of Voltairine de Cleyre

Introduction

“Nature has the habit of now and then producing a type of human being far in advance of the times; an ideal for us to emulate; a being devoid of sham, uncompromising, and to whom the truth is sacred; a being whose selfishness is so large that it takes in the human race and treats self only as one of the great mass; a being keen to sense all forms of wrong, and powerful in denunciation of it; one who can reach in the future and draw it nearer. Such a being was Voltairine de Cleyre.”[11] Jay Fox’s eulogy succeeds in evoking both the unique place of Voltairine de Cleyre in the history of American anarchism and the respect which she commanded among her comrades. Rudolf Rocker, who met her in London in 1903 and visited her grave in Chicago a decade later, considered her “one of the most wonderful women that America has given the world.”[12] Max Nettlau, the foremost historian of the anarchist movement; described her as “the pearl of Anarchy,” outshining her contemporaries in “libertarian feeling and artistic beauty.”[13] Marcus Graham, editor of the journal Man!, called her “the most thoughtful woman anarchist of this century,” while Leonard D. Abbott ranked her, along with Emma Goldman and Louise Michel, as “one of the three great anarchist women of modern times.”[14] To Emma Goldman herself, in spite of much bitterness and friction between them, Voltairine de Cleyre was “the poet-rebel, the liberty-loving artist, the greatest woman Anarchist of America.”[15]

And yet, of all the major American anarchists, Voltairine de Cleyre has received the least serious attention from historians and literary scholars. Even the most elementary facts of her life are unknown to all but a handful of specialists, who themselves have perpetuated the errors and myths of previous generations.[16] Surprisingly, Voltairine de Cleyre is not so much as mentioned, let alone accorded the space she deserves, in the widely read histories of anarchism by George Woodcock, James Joll, and Daniel Guérin,[17] while the most authoritative accounts of her career (produced by Max Nettlau) remain buried in an Argentinian anarchist journal of 1928 and in an unpublished volume of Nettlau’s German-language history of anarchism.[18] Nor is she represented in any of the anthologies of anarchist or feminist writings that have appeared in recent years, although her essay on “Anarchism and American Traditions,” perhaps her best-known work, has been reprinted in two documentary collections of American radical thought.[19]

The reasons for this neglect are not far to seek. The most important, perhaps, are the brevity of her life and the difficulty of finding relevant source materials. Voltairine de Cleyre was of the same generation as Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, and a number of other prominent American anarchists. But she died in 1912 at the age of 45. Thus she did not live to see the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the Spanish Civil War, which marked the high-points of anarchist activity during the twentieth century. Goldman and Berkman outlived her by a whole generation, twenty-eight and twenty-four years respectively. Her own mother survived her by fifteen years, her elder sister Adelaide by thirty-three. Because of her untimely death, ending her career abruptly in mid-course, there are few people now alive who so much as attended her lectures or met her even casually at anarchist meetings, let alone knew her on an intimate basis. And the passing of her only child in 1974 removed the last direct link; her grandchildren were all born after her death and thus have no recollection of her.

Furthermore, Voltairine de Cleyre was seldom in the public limelight during her short life. In contrast to Emma Goldman, she shrank from notoriety. Her withdrawn, retiring nature kept her out of the headlines except for a few brief periods, as in 1902, when she was wounded by an assassin, and in 1908, when she was involved in a free-speech disturbance in Philadelphia. Unlike Emma Goldman or Alexander Berkman, moreover, or Lucy Parsons or Johann Most, she was never imprisoned, although she was once arrested and brought to trial but acquitted. Though well known among the anarchists in the United States, she played no role in the international movement comparable to that of Most or Goldman or Berkman. She traveled only twice to Europe (in 1897 and 1903), and her writings, though translated into several languages, never became as widely known as the works of these other figures.

Had she been granted the financial means, the physical constitution, and the necessary leisure for sustained writing and speaking, Voltairine de Cleyre might have emerged in the forefront of both the anarchist and feminist movements. As it was, however, she was compelled to work long hours to earn a meager living, with the result that she remained largely in the background and out of the public consciousness, gaining sudden but fleeting prominence on a few dramatic occasions. She was a brief comet in the anarchist firmament, blazing out quickly and soon forgotten by all but a small circle of comrades whose love and devotion persisted long after her death.

Today, however, even among the older generation of anarchists, Voltairine de Cleyre remains little more than a memory. But her memory possesses the glow of legend and, for vague and uncertain reasons, still arouses awe and respect. She is not rated among the major theorists or practitioners of the anarchist creed, such as Godwin or Proudhon, Stirner or Tucker, Bakunin or Kropotkin, Malatesta or Reclus. Yet she is a distinguished minor figure, a strong and unusual personality among the many interesting men and women thrown up by the anarchist movement around the turn of the century. She produced a number of essays which have enriched the literature of anarchism; and, though American born and rooted primarily in native traditions, she became, like Rudolf Rocker in London, the apostle of anarchism to the Jewish immigrants of the Philadelphia ghetto, learning to read and to some extent to speak and write the Yiddish language, in addition to her knowledge of German and proficiency in French which she acquired from her father and from the Catholic convent where she was educated.

It is not difficult, then, to understand the fascination, verging at times on reverence, that she inspired among her contemporaries, and continues to inspire among the dwindling band of survivors of the classical age of anarchism which preceded the First World War. To Abraham Frumkin, a prominent Jewish anarchist who first heard her speak in London in 1897, her name itself had a beautiful, exotic sound that somehow fit her character and appearance.[20] But it was her writings that won her lasting acclaim among her comrades. An inspired essayist and poet, she possessed a greater literary talent than any other American anarchist. She was at pains to write well; and she put into what she wrote a voice, an era, a state of mind that nobody else has conveyed. She was, in fact, one of the most powerful and distinctive writers in the entire anarchist movement, with an individuality of mind and expression that only the very gifted possess. Her prose, distinguished, in Emma Goldman’s words, by an “extreme clarity of thought and originality of expression,” reflects the working of a first-rate intellect and a strong creative impulse. Leonard Abbott, associate editor of Current Literature, called her “a gifted and distinguished writer” whose arresting images and phrases “live vividly in my mind after forty years.”[21]

She was also a voluminous writer, publishing hundreds of poems, essays, stories, and sketches, mainly on themes of social oppression, but also on literature, education, and women’s liberation. Her note is distinctively American, yet she had a more universal appeal, and her prose has been translated into several languages, including French, Italian, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, German, and Yiddish. She herself was an accomplished translator, rendering into English Jean Grave’s Moribund Society and Anarchy and Francisco Ferrer’s The Modern School. She also produced an unfinished translation of Louise Michel’s autobiography, the manuscript of which has been lost; and her translations from the Yiddish of Libin and Peretz appeared in the early issues of Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth.

Owing to her unfortunate personal and financial circumstances and to chronic ill health, Voltairine de Cleyre’s literary potentialities were never completely fulfilled. She never published a full-length book, something she always regretted. A novel on social themes, written in collaboration with Dyer D. Lum, remained unprinted during her lifetime, and the manuscript has not survived. Nor did her shorter works reach a large audience outside the anarchist and free thought movements. A selection of her writings, edited by Alexander Berkman, was brought out by the Mother Earth Publishing Association in 1914, two years after her death, but many of her best poems and essays remain buried in obscure and hard-to-find periodicals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, while most of her manuscripts and letters—she was a careful and prolific correspondent—have been lost.

To a large extent, it is true, the power of her pen derived from her personal suffering and from her sympathy with the suffering of others. Yet if she had enjoyed greater physical comfort and peace of mind, she might have achieved a reputation beyond the circles of freethinkers and libertarians in which she revolved. Her failure in this regard was one of the greatest disappointments of her life. “Had she followed the line of least resistance, and forgotten her principles, she would have been famous,” wrote her Scottish friend, Will Duff. “Instead she spent her tortured life in the service of an obscure cause—lecturing, teaching, and writing for Anarchist papers.”[22]

To the modern reader her writing may seem at times too flowery, displaying a weakness for rhetorical flights. In this respect, it resembles the essays of the French anarchist Elisée Reclus and of other romantic revolutionaries of the Victorian and Edwardian period. Yet much of what she wrote retains its vitality and originality. Her prose seems superior to the work even of Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, and Benjamin Tucker, who figure among the most talented anarchist writers in English, possessing a lyrical quality that the other three lacked. Nor, so far as I am aware, did any of them publish a line of poetry or fiction, of which Voltairine de Cleyre’s output was prodigious. She wrote for both Tucker’s Liberty and Goldman and Berkman’s Mother Earth. Emma cherished her stories for their stylistic beauty and descriptive power, singling out “The Chain Gang” (which appeared in Mother Earth in October 1907) as a literary gem. Berkman shared this opinion. “I consider Voltairine de Cleyre one of the best short story writers in America,” he wrote to Upton Sinclair, “of high idealism and clear social view. A proletarian writer.”[23]

For all their elegance, however, her writings could become emotional and occasionally maudlin. They were always intensely and sometimes passionately felt, sounding a mournful note, a note of deep and overwhelming sadness. “The world is as full of weeping as the heavens are full of stars” is a not uncharacteristic line from her poems.[24] Leonard Abbott remarked: “Her voice has a vibrant and somber quality that, so far as I know, is unique in literature. Crimson as blood, black as hate, are some of her lyric utterances. Night birds flap their wings, ‘the whipped sky shivers,’ and the wind roars from the depths of the sea, in the ghostly visions she evokes.” Her best poems, as Abbott noted, were poems of vengeance. “They are crimson and black; they quiver with hatred.”[25] To Emma Goldman these morbid preoccupations constituted a serious drawback: “She saw life mostly in greys and blacks, and painted it accordingly. It was this which prevented Voltairine from being one of the greatest writers of her time.”[26]

Voltairine de Cleyre’s writings reflected not only the miseries of humanity at large but also her profound personal unhappiness, the tragedy of her own existence. Her life was so littered with catastrophes and misfortunes that Will Duff described it as “a long-drawn-out martyrdom.”[27] She was a troubled and a troubling spirit, the woes of the world weighing heavily upon her. On this point all her acquaintances were unanimous. “A great sadness, a knowledge that there is a universal pain, filled her heart,” wrote Hippolyte Havel in the Introduction to the Selected Works. “I feel in her a tragic and tortured spirit,” said Leonard Abbott, “one of the most tragic figures that I have ever known.”[28] Born in poverty in Michigan, she lived in poverty in Philadelphia and died in poverty in Chicago after weeks of agonizing pain. She suffered from chronic physical illness and moral torment. Her life, moreover, was jarred by a series of emotional dislocations which might have destroyed a weaker nature. Her lover and mentor, Dyer D. Lum, committed suicide; and she herself had frequent suicidal impulses and tried to take her own life more than once. In 1902, when she was thirty-six, she was the victim of an assassin’s bullets which nearly killed her and, by aggravating her already weak physical condition, left her in constant pain and shortened the remaining span of her life.

On top of all this, Voltairine de Cleyre wore herself out in the day-to-day struggle for existence and in her unremitting labors for her cause. Her earnings were insufficient to keep her in even moderate comfort; and as the years wore on and the effects of her illness, poverty, and accumulating misfortunes took their toll, she became increasingly introverted, shrinking from people and conversation. Her natural disposition toward privacy, reinforced by her physical pain, made her, in Emma Goldman’s words, “taciturn and extremely uncommunicative.” “I never feel at home anywhere,” Voltairine wrote. “I feel like a lost or wandering creature that has no place, and cannot find anything to be at home with.”[29]

There was very little joy in her life, especially in these later years. Not that she was incapable of happiness. In her youth during the 1880s and 1890s, her letters often sparkled with gaiety, and she was in general more animated and cheerful than she is sometimes depicted. Emma Goldman, in particular, exaggerates the gloomy side of her character and consequently leaves a distorted picture. Yet humor was not one of her notable attributes. For her life was too touched by sadness, at times by outright calamity, to allow more than temporary relief from her melancholy.

Although an atheist and freethinker with a “logical, analytical mind,”[30] Voltairine de Cleyre possessed a deeply religious nature. In spite of her pragmatic approach to anarchist theory and practice, she remained at bottom a zealot of sectarian temperament, ascetic, self-sacrificing, even puritan, akin to the religious heretics of the past. Had she lived in the Middle Ages, she might have been a Cathar or a Waldensian or a Sister of the Free Spirit. Emma Goldman speaks of the “religious zeal which stamped everything she did. . . . Her whole nature was that of an ascetic. Her approach to life and ideals was that of the old-time saints who flagellated their bodies and tortured their souls for the glory of God.”[31] Educated in a Catholic convent, she once considered becoming a nun; and, in a sense, this is in fact what she did. By living a life of religious-like austerity, she became a secular nun in the Order of Anarchy, consecrating herself to her ideal. “In the service of the poor and oppressed she found her life mission,” wrote Hippolyte Havel. But it was Sadakichi Hartmann, the Eurasian writer and poet, who summed it up best: “Despite the wealth of her emotions, limitless sympathies, and love for nature, her whole life seemed to center upon the exaltation over, what she so aptly called, the dominant idea. Like an anchorite, she flayed her body to utter one more lucid and convincing argument in praise of direct action. She starved and endured, and worked indefatigably for the enlightenment of the masses. She was brave, far seeing, invincible, one of the staunchest, truest, never-tiring banner-bearers of Anarchism, the great cause that to so many means the solution of the most important problem of modern society, the problem of equal rights for all.”[32]

In time, Voltairine de Cleyre acquired the status of a saint. Leonard Abbott, who presided over a memorial meeting after her death and called her “one of the strongest influences in my life,”[33] named his first daughter, who died in infancy, Voltairine. Other anarchists did the same. During her own lifetime, there was a Voltairine de Cleyre Blum at the Playhouse School in Brooklyn, conducted by the pioneer libertarian educators, Alexis and Elizabeth Ferm. In after years there was a Voltairine de Cleyre Bernstein in Chicago and a Voltairine de Cleyre Winokour in Stelton, New Jersey, both of them children of anarchists. The main thoroughfare at Stelton, the most important anarchist colony in America, was called Voltairine de Cleyre Street. (The library was named after Peter Kropotkin and the colony itself after the Spanish educator and martyr, Francisco Ferrer.)

On the eve of the First World War, Adolf Wolff, an anarchist sculptor and poet at the Ferrer Center in New York, included Voltairine de Cleyre among the heroines for his daughter to emulate:

A Joan of Arc leading a people to victory,

A Louise Michel fighting on the barricades,

A Voltairine de Cleyre singing songs of revolt,

An Emma Goldman preaching the gospel of rebellion.[34]

The juxtaposition of Voltairine de Cleyre with Louise Michel was particularly apt, for the parallels between them, down to their French names and origins, are striking. In her religious-like passion and asceticism, her acute sensitivity to suffering, her pity for the unfortunate and exploited, her hatred for cruelty and oppression, Voltairine de Cleyre resembled Louise Michel—whom she met in London in 1897—more than any other figure in the anarchist movement. Both were teachers and poets who were militantly devoted to their ideal. Both were wounded in assassination attempts; and both, returning good for evil, refused to press charges against their assailants. Both, moreover, loved plants and animals with deep feeling. Voltairine, as Emma Goldman noted, “would give shelter to every stray cat and dog,” something it would be hard to imagine Emma herself doing. As her friend George Brown remarked, “I have never known any one who had so much sympathy for dumb animals. In fact, she made the house a hospital for misused cats and dogs,” and in keeping with her Tolstoyan precepts, she would not destroy life of any kind if she could avoid it, so that “when pests invaded her rooms she captured them and carried them out.”[35] In view of these similarities, it is small wonder that she should have translated Louise Michel’s autobiography; and it was fitting that Leonard Abbott should have called her “a priestess of pity and vengeance,” a phrase originally applied to Louise Michel by the British editor and reformer, W. T. Stead.

Voltairine de Cleyre bore an equally striking resemblance to Mary Wollstonecraft, the inaugurator of the modern women’s rights movement, about whom she often wrote and lectured. As with Louise Michel, both were poets and writers and pioneering feminists and libertarians. Intense, dedicated, troubled, they both led turbulent, tragic lives and suffered untimely deaths. Intelligent and high-strung, both lived as individualists in the face of stifling convention. And yet, for all their independence of spirit and strength of character, both were vulnerable in the extreme, passing through a series of unhappy love affairs which left them with permanent scars. Both traveled to Norway to seek escape and solace; both worked as teachers and as translators of French; and both called for educational as well as political and economic reform as a cure for society’s ills.

Short as it was, Voltairine de Cleyre’s life spanned the classical age of anarchism between the Commune of Paris and the First World War. She was a contemporary of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman—two and a half years older than Emma, four years older than Sasha—and her interesting relationships with both will be treated in this book. Her radical career coincided with the rise of the American anarchist movement to its fullest flowering. She lived through, and was profoundly affected by, the Haymarket hangings of 1887, the Homestead strike of 1892, and the McKinley assassination of 1901, dying a decade later, on the eve of the great war, when anarchism had reached its zenith and stood on the threshold of decline.

Her life, at the same time, stretched from America’s agrarian past into its industrial and urban present. Born just after the Civil War, she witnessed the passing of the western frontier, the development of corporate capitalism, the centralization and bureaucratization of government, the convulsive changes in population and social relations, and the rise of the United States to the position of a world power, which cast a shadow over the promise of its future. To Voltairine de Cleyre and her associates, the Gilded Age seemed fraudulent, hypocritical, and ruthlessly and coarsely materialistic. It was an era of gluttony and ostentation, of unbridled economic exploitation and unparalleled political corruption, from which men and women of conscience must recoil in indignation and disgust. Together with other articulate reformers, she was attracted by the self-sufficient, noncommercial aspects of American life, the dream of every man his own master and the lost Jeffersonian ideal of autonomous villages and towns, workshops and farms, which had fallen victim to omnivorous corporate industrialism and centralized political power.

In her speeches and writings she drew up a scathing indictment of the new America of big business and money values that, swelling to monstrous proportions, confronted the world at the turn of the century. She criticized the whole range of oppressive institutions, the whole character of the new America in the making, including nearly every feature of American life that has again come under attack in our own time, from militarism and expansionism to racial and sexual exploitation and rapacious industrial development, in short, the whole “modern empire that has grown up on the ruins of our early freedom,” as she put it in one of her best-known essays.[36]

A study of Voltairine de Cleyre’s life, then, is also a study of American society and of the American anarchist movement during its heyday—its “blossom-time,” as Max Nettlau called it—in the decades before the world war. My main concern, however, is biographical: to piece together the facts of her career, to analyze her character, her ideas, her feelings, to explain the intense fascination which she exerted on her companions, to depict the life which throbbed behind her writings. I must leave to others the task of providing a specialist’s analysis of her stories and poems, for which I, as an historian, am inadequately equipped. I would hope, however, that the historical and biographical material presented herein will prove useful to the scholar who will one day undertake an evaluation of her literary legacy.

It is not easy to discover the concealed, often subconscious motives, those hidden springs of action and behavior, which few of us understand in ourselves, much less in others. Voltairine de Cleyre was an extremely complicated individual of a type that does not yield its secrets readily. Therefore, while not avoiding a discussion of her underlying motives, I shall adhere as closely as possible to the available sources and quote extensively from her writings, both published and unpublished. Although documentation is occasionally sketchy—for some episodes almost nonexistent—enough has survived to permit a reasonably complete account of the life of this fascinating woman who, in Emma Goldman’s words, “was born in some obscure town in the state of Michigan, and who lived in poverty all her life, but who by sheer force of will pulled herself out of a living grave, cleared her mind from the darkness of superstition—turned her face to the sun, perceived a great ideal and determinedly carried it to every corner of her native land. . . . The American soil sometimes does bring forth exquisite plants.”[37]

1. Childhood

Voltairine de Cleyre grew up in the American Middle West of flat farms and little towns. She was born, as her sister describes her, “a dainty, fragile girl child,”[38] in the village of Leslie, Michigan, a year after the Civil War ended. Her rebellious character, which manifested itself at an early age, had both native and European roots. On her mother’s side, she was linked to the abolitionist movement of antebellum America; on her father’s, to the artisan, socialist, and free thought traditions of early nineteenth-century France. From both parents, moreover, she inherited a strong will, a stubborn nature, and a keen intellect. Her sister writes: “Our mother was a remarkable woman. Father was a brilliant man. It is no wonder Voltai was a genius.”[39]

Her father, Hector De Claire, came from Lille, in northern France, where he was born in 1836. Though brought up in the Catholic faith, as a boy he became “tinged with earlier French skepticism,” and by the time he was twelve, during the Revolution of 1848, he was already, like his own father, a socialist, “which is probably the remote reason for my opposition to things as they are,” Voltairine remarks, for “at bottom convictions are mostly temperamental.”[40] At the age of eighteen, in 1854, Hector De Claire emigrated to the United States, and both he and a brother fought in the Civil War on the side of the North, for which they were rewarded with American citizenship.

In the years before the war, Hector De Claire worked as an itinerant tailor in the European artisan manner, tramping from town to town in central Michigan. On March 28, 1861, two weeks before Fort Sumter and the outbreak of hostilities, he married Harriet Elizabeth Billings, who had come to Kalamazoo in 1853 from Rochester, New York, where she was born, the youngest of eight children of Pliny and Alice Billings, on December 27, 1836. Of old New England Puritan stock, her father had been an abolitionist in the “Burned-Over District” of upper New York state, where William Lloyd Garrison had stumped for the antislavery cause, and he had helped with the escape of fugitive slaves passing through Rochester on the underground railroad on their way to Canada.[41]

Hector and Harriet De Claire had three daughters, all born in Leslie, some twenty miles south of Lansing. The first, Marion, arrived on May 26, 1862. Next came Adelaide, on March 10, 1864, then Voltairine, the youngest of the three, on November 17, 1866. As a liberal and freethinker, Hector De Claire was an admirer of Voltaire, which, Voltairine tells us, prompted his choice of her name, though “not without some protest on the part of his wife, an American woman of Puritan descent and inclined to rigidity in social views.” After two girls, moreover, he had been hoping for a boy. Accordingly, as Adelaide puts it, “he coined a name to fit the occasion, and called the baby Voltairine.”[42]

In May 1867, the De Claires received what Adelaide calls “the greatest shock and sorrow of their lives.” Marion, just five years old, was accidentally drowned. Missing her from her play, her mother went to look for her and “found her little draggled body in the river under the bridge,” a tragedy, says Adelaide, which “may have caused many of the psychological mishaps that came to our family.”[43] In their grief the parents decided to move. Hector De Claire managed to scrape together enough money to buy a small frame house at 204 South Lansing Street in St. Johns, Michigan, some forty miles to the north in Clinton County, where Voltairine’s mother was to live for sixty years, until her death at the age of ninety in 1927, and Adelaide until 1945 when she died at eighty-one.

When the family moved to St. Johns, Voltai (as she came to be called) was less than a year old. She was to have no recollections of a happy, secure childhood in old agrarian America. Nor was she to be among that first generation of college-trained American women, drawn from the middle and upper classes, who threw themselves into the reform movements of the Gilded and Progressive eras. On the contrary, she was raised in extreme and unrelieved poverty, and her formal education stopped in a Catholic convent in Canada when she was seventeen. Her birth itself, she thought, coming in “the bleak mid-November of a northern winter,” had set the scene for a grim existence, embittered by the want of common necessities, which her parents, hard as they tried, were unable to provide. As she wrote in an early poem:

Born among the snows and pines,

Gray faced sorrow was to be

Imaged in my mournful lines.[44]

To assist her husband, who scratched out a meager and difficult living at his tailor’s craft, Harriet De Claire herself took in sewing, so that they “managed to feed us, sparingly, and clothe us and keep us in school,” Addie recalls. But “we were among the very poor. There was no ‘Welfare’ in those days, and to be aided by any kind of charity was a disgrace not to be tho’t of. So we were all underfed, and bodily weak. Poor father could not carry the burden of our support, and mother did what she could. So did I. But it was very up-hill work.”[45] To their own grinding poverty Addie attributes much of her sister’s future radicalism, not to mention “the deep sympathy and understanding that she had for poverty in others.” In a similar vein, Voltairine herself speaks of her compassion for the impoverished and disinherited and of “the awful degradation of the workers, which from the time I was old enough to begin to think had borne heavily upon my heart.”[46]

A measure of their poverty was that Voltai and Addie were unable to buy Christmas presents during these childhood years in St. Johns. “We wanted, as all children do, to give our parents and each other something,” Addie recalls, “but spending money was an unknown quantity with us. So we had to make our own gifts.” One year Voltai made her mother a little box with a padded cover with colored beads sewn on it and a little case for Addie’s crochet-hook out of a scrap of cardboard. “Poor little kiddie!” wrote Addie, when she found these articles in the attic many years later. “I think she was about nine years old then.”[47]

Added to their privation was a mounting friction between the parents, which stemmed, at least in part, from their economic difficulties. As the years wore on, Hector De Claire became an increasingly bitter man and, though not without affection for his daughters, a rather stern and demanding father. “Father’s life was such a disappointment to himself,” wrote Addie to Joseph Ishill, an anarchist printer who was assembling her sister’s manuscripts. “And mother’s also. Yet, in his way he was kind to us.” Addie, at the same time, speaks of his “impulsive nature,” while Voltairine’s son Harry calls him “a petty tyrant.”[48] When Voltairine was nearly thirty and living in Philadelphia, he could still scold her for writing to him in pencil, which displeased him as much then, he complained, as fifteen years before “when I brushed you up over the same thing.”[49]

Their mother, too, was often out of sorts. Although she lived to be ninety, she suffered from a chronic sinus inflammation, which Voltairine attributed to long stretches of malnutrition and “fifty years of deprivation.” She was also ungenerous with her affections, holding back her love and not allowing it to blossom. In her poem “To My Mother,” written in 1889, Voltairine alludes to this coolness:

Some suns there are which never pierce their cloud;

Some hearts there are which cup their perfume in,

And yield no incense to the outer air.

Cloud-shrouded, flower-cupped heart: such is thine

own:

So dost thou live with all thy brightness hid;

So dost thou dwell with all thy perfume close;

Rich in thy treasured wealth, aye, rich indeed—

And they are wrong who say thou “dost not feel.”[50]

Like most mothers of her time and background, Harriet De Claire sought to guide her daughters into the conventional channels of American life. Against Adelaide’s wishes, she pressed her to become a schoolteacher (“I would rather have gone into a newspaper office, but she was opposed to it”). Not that the good-natured, even-tempered Addie wished to break away, like her rebellious sister, and lead the life of an emancipated woman. She remained conservative in her political and social views and, “much to Mother’s dislike,” became a Baptist. “I have been quite proud of the genius of my talented sister,” she wrote to Joseph Ishill, “but I am glad to be one of the ‘common people’ myself. Mother could never see any use, or beauty in service of this kind. She never forgave me for marrying two poor men. But they were real men, and I was always proud that they selected me from the world of women.”[51]

Addie, however, excused her mother’s shortcomings. “Don’t judge her too harshly,” she wrote to Agnes Inglis, curator of the Labadie Collection, for she was the youngest of eight children and “so she naturally grew up very self-centered.”[52] Voltairine was less forgiving, although she remained a devoted daughter all her life, wrote and visited her mother often, and, at great sacrifice, sent her regular sums of money from her meager earnings. “I couldn’t fulfil your wishes for me,” she told her mother in 1907, “which were probably that I would have entertained your own principles, married some minister or doctor, or been one of them myself, and have a home, children, and a warm room for you—I mean the idea that the parent gives to the child in youth and the youth returns to the parent in age. All that is utterly foreign to me. I have wanted even less of life than you, for myself. I have cared neither for a home nor any of its addenda. But I have wanted a whole lot of other things, and I’ve got some of them. I have wanted to travel and see the whole world; I’ve seen some. I’ve wanted to print the force of my will—not over-rating it—on the movement towards human liberty. And I have done that, to a certain extent. I have failed in one thing, and that was to hold a place in literature. And I think I have failed partly because I haven’t cheek and persistence enough, and mostly because I’ve always had to do other things. But altogether I think I’ve had more satisfaction in my forty years than you in your seventy.”[53]

Voltairine de Cleyre grew up to be an intelligent and pretty child, with long brown hair, blue eyes, and interesting, unusual features. She had a passionate love for nature and animals. But, already displaying the qualities that were to trouble her personal relations in later life, she was headstrong and emotional. She was “a very wayward little girl,” says Addie, “often very rude to those who loved her best.” Her eyes could be warm or as “cold as ice.” When only four, her “indignation was boundless” when she was refused admission to the primary school in St. Johns because she was under age. She had already taught herself to read, says Addie, “and could read a newspaper at four! I have never known a child who could do that.” Admitted the following year, she was “a bright pupil” and attended the school till the age of twelve. “She was very good friends with all her teachers; but especially a Mrs. Helen Lamphere, who had more influence over her than any one else up to that time.”[54]

At home, both Voltai and Addie were voracious readers. They consumed poetry and novels—Dickens, Scott, Wilkie Collins—“but very little trash,” and discussed what they read with their mother. Literature, writes Addie, was “nearly all the comfort we had.” Mrs. De Claire was herself fond of poetry, especially Byron, which she read to her daughters before putting them to bed. She was “a remarkably fine reader,” says Addie. “The pleasantest memory of my childhood is of Mother reading to us in the evenings.” Many years later, when Addie was visiting Voltairine in Philadelphia, she told her sister that her poetry had “the ring and rhythm of Byron,” to which Voltairine replied, “Can you wonder at it?”[55]

Voltairine herself began to write at a very early age. “Her little hands were not very steady or expert in the use of a pen,” Addie recalls, “and her desk was a board that she had fixed up in the branches of one of our maple trees,” seating herself on an adjacent limb to write or draw. Sensitive and introspective, she had an overriding need for privacy, even as a child, and often took refuge in her tree, her personal retreat, where she could think and write without being disturbed. “Our mother was determined to cut that tree down; but I fought for its life and saved it.”[56]

Rummaging through the attic in 1934, Addie discovered what is Voltairine’s first known poem, “My Wish,” written when she was about six years old “while sitting at her little home made table up in our north maple tree.” It consists of three short stanzas, the first and third of which Addie copied (the second was illegible) and sent to Joseph Ishill:

To live up in a tree

Or a butterfly upon a flower

Or maybe a honey bee.

But more than all I wish I was

A great big man like Pa!

And wouldn’t have to stand around

But would have a chance to jaw!

In 1936 Addie found another poem, tucked away in an old book of her mother’s. This one, written when Voltairine was eight or nine, was called “The School-House Over the Way”:

It carries me there to-day—

So I think I’ll take this rose bud,

To sweeten and brighten the way.

As the dew on the bud is heavy,

And bowed down by its weight,

I stoop down to pick it slowly

And condescend to fate.

As I stoop down to pick it slowly

And I think of the dreary way

And the long, long mess of trouble

I’ll have ’ere the close of the day.

At last I have reached the school-house

The gems on the bud are gone

But as I touch it softly

It seems more beautiful grown.

The studies at length are over

And the examples are all done

And then there is shouting and laughter

For we’re all a-going home.

My beautiful bud has wilted

For as older it grew

The beautiful faded

And took a duller hue.

But methinks it has done its duty

That beautiful little bud

And I hope we shall all learn the lesson

The lesson of doing good.

Examining these lines, one finds little of “the vein of sadness” that Hippolyte Havel discovered in Voltairine de Cleyre’s early poems, “the songs of a child of talent and great fantasy,” as he describes them.[57] Yet they are remarkably good for a child of her age, as her sister was quick to point out. “And to think that neither Mother, nor Father nor I realized nor recognized Voltai’s beautiful spirit nor soul,” wrote Addie to Agnes Inglis, to whom she sent the second poem. “I want you to see it as I do—the spontaneous out-pouring of her practical nature and reaching for beauty of expression. I cried as I read it, and am crying now as I write, to think of all the wasted years of misunderstanding, when we were children, when our childish years should have been filled with beauty, as they could have been.”[58]

But beauty failed to materialize. Indeed, matters became still worse as Hector De Claire found it increasingly difficult to get work in St. Johns, where many of the residents did their own sewing. During the early 1870s, therefore, he left home and went again on the tramp, as he had done before his marriage. After a while he settled down in Port Huron, a town with more than 13,000 inhabitants and a lively trade in lumber and fish. As far as one can tell, he never returned to his wife or to the house in St. Johns. He sent home money whenever he was able. But his absence, far from relieving the tensions within the De Claire household, only compounded the unhappiness of his daughters, who “suffered much shame and sorrow in that we were children of separated parents. All the bitter pain of it was ours.”[59]

In the spring of 1879 Adelaide fell seriously ill, and Voltairine was sent to live with her father, who was still working as a tailor in Port Huron. I was “very sick,” recalls Addie, and mother thought that “she could not do for both of us.” Voltai was twelve years old and “had developed that wilfulness that comes to most girls at that age; and Mother had neither the taste nor the strength to cope with it. So Voltai was sent to Father.”[60]

A restless child on the threshold of adolescence, Voltairine was bored and fidgety in Port Huron, and extremely homesick. She missed the house in St. Johns and the rural life to which she was accustomed. She missed her mother and sister, her maple tree and chickens, her pet birds “Petie” and “Sweetie.” “I don’t want you to write to Pa but I think Port Huron is a nasty hole,” she wrote her mother in June 1879. “I want to come back to St. Johns. I am just as homesick as can be.” On Sundays her father took her to the park to listen to the bands and on the ferry boats plying between Michigan and Ontario. But her homesickness grew worse every day. “I don’t like a city,” she wrote. “They have such times with the privies. I want to come home.”[61]

Nothing further is known of the more than a year that Voltairine de Cleyre spent in Port Huron. Whether she attended school there, whether she returned for visits to St. Johns, remains obscure. In September 1880, however, her father enrolled her in the Convent of Our Lady of Lake Huron at Sarnia, Ontario, directly across the river from Port Huron. Why should a liberal and freethinker have taken such a step? According to Hippolyte Havel, Hector De Claire had “recanted his libertarian ideas, returned to the fold of the church, and [become] obsessed with the idea that the highest vocation for a woman was the life of a nun.”[62] Havel, however, is mistaken. For her father did not rejoin the church until several years later, when she had already graduated from the convent. “I never heard that Father wanted her to become a nun,” wrote Addie, “and can hardly believe it.”[63] Nor was his object to punish his difficult child, as Havel implies, although he did hope that she would “tone up” and shed some of the “impudence and impertinence, so very prominent in her.” Besides, he worked twelve hours a day, notes Agnes Inglis, “and what was he to do with an emotional high strung girl?”[64]

The convent, wrote Hector De Claire to his wife, will “refine her, so she has manners and knows how to behave herself and cure her of laziness, a love of idleness, also love of trash such as Story Books and papers,” and it will “give her ideas of proprieties, of order, rule, regulation, time and industry, as I doubt not you know she needs.” Apart from this, however, he recognized that his daughter was gifted and wanted her to have the best education consistent with his limited means. The convent seems to have been the best school in the vicinity, where she could “get instruction in a vast amount of work, such as makes up a young woman.”[65] He labored long and hard to pay her tuition and board, which cost him a thousand dollars, a very large sum for a man in his circumstances to pay. Sending her there, says Addie, nearly “crippled him financially.”[66]

Voltairine de Cleyre spent three years and four months at Sarnia, from September 1880 to December 1883. In later life she looked back on this period as the saddest and darkest of her life—as a term of “incarceration.” It had “a lasting effect upon her spirit,” Emma Goldman observed, killing “the mainspring of joy and gaiety in her.”[67] That a girl of her age, a sensitive, emotional child, suddenly removed from her family and put in a convent, should be untroubled is hardly conceivable; and though the extent of her suffering was exaggerated in retrospect, though the convent was perhaps not as dismal as her memory painted it, being wrenched from her home, from her mother and sister, was a trauma from which she never fully recovered. For the rest of her life its effects remained with her, compounding the misfortunes that accumulated as the years progressed. She never completely understood how her father, for whom she had considerable affection, could have abandoned her to such a situation; nor could she forgive him for doing so.

After a few weeks at the convent she decided to run away. Escaping before breakfast, she crossed the river to Port Huron. From there, as she had no money, she began the long trek to St. Johns on foot. After covering seventeen miles, however, she realized that she would never make it all the way home, so she turned around and walked back to Port Huron and, going to the house of acquaintances, asked for something to eat. They sent for her father, who took her back to the convent.

By any standard the regimen at the convent was severe. The girls got up at 5:45 every morning, made their beds, then went downstairs to say prayers. Admitted as a Protestant (her mother was a Presbyterian), Voltairine was not compelled to recite them, and she was permitted access to the Bible, which, according to her son, “was denied to those of the Catholic faith.” Yet she had to remain with the others “on our knees ½ an hour.” Breakfast was at 7, dinner at 12, supper at 5, with classes from 9:30 to 11:30 and 1:30 to 4:30, conducted by the nine nuns of the convent, Carmelites of the Order of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary. Sister Mary Médard, wrote Voltairine many years later, “was the only little sister who sympathetically kissed me when all the rest were frowning.”[68]

The pupils at Sarnia were allowed to write home only once every two weeks. As Hector De Claire informed his wife, all letters, papers, and books were “strictly under the surveillance of the mother superior, so in writing to [Voltairine], govern yourself accordingly and do not abuse me nor the Nuns, nor the Town or the British Government for if you do, she’ll never get the letters.”[69] In this connection, Addie records an incident which reveals a good deal both about the convent and about her sister: “Once I wrote to her, I suppose a silly letter as girls often write to each other. I’m sure there was no harm in it—but the nuns kept it from her, but in plain sight, until our Father should come over from Port Huron, and tell them what to do with it. I believe it was a week or more. You know in those schools all the mail is read by the nuns first. Well, when Father came he saw no harm in the letter and let her have it. Then she wore it in her belt until it wore out!” Addie then vents her indignation: “Oh that horrible, accursed convent! She was there about three years I think, and came away a nervous wreck. She was very self willed I suppose, and she was unmercifully punished—and such inhuman punishment! She hardly dared mention these things; but told me that at one time, for a week, she was made to go out for ‘recreation,’ with the others, but they were forbidden to speak to her. Think of that, for an oversensitive, nervous child to endure!”[70]

As the weeks passed, however, Voltai’s homesickness abated, if it did not dissipate completely. At first she was “terribly disgusted and lonesome,” wrote Hector De Claire to his wife on September 17, 1880, but “this week she is all right, and after kicking against the rules all last week is now beginning to laugh at the antics she had cut up, and comes down peacefully.”[71] A few days later Voltairine was allowed to visit her father in Port Huron. While there she took the opportunity to write to her mother “because I don’t want the sisters to read my letter.” The convent, she now confided, was “a very nice place. I learn physiology, Physical Geography, mythology, French, Music, writing and Manners. They wanted me to study Arithmetic but I wouldn’t. To-morrow there is a confirmation and I am going to sing for the Bishop. Don’t be scared for fear I shall be a Catholic for the nuns are ladies and force their religion on no one.” Voltai still missed St. Johns, however, and sent her love to Addie “and to my maple tree and chickens. They sent me my birds but only Petie was alive. Poor little Sweetie was dead.”[72]