Nohara Shirõ

Anarchists and the May 4 Movement in China

A Note on the Pronunciation of Chinese Names and Terms

Unite With the Toiling Masses!

The rise and fall of practical activities

Translator’s Note

Until the post-Cultural Revolution thaw that began in 1979, Chinese readers found it next to impossible to gain access to information about the strong anarchist influence within their country’s revolutionary movement. From the point of view of the ruling Communist Party, in whose favour historical materials were invariably rewritten, this was a necessity borne out by the fact that, when people took to the streets in 1989 to demand a degree of control over their own lives, among the slogans that they raised were the traditional ones of anarchism. One of the few sources of information on anarchism available in Chinese before the 1960s was the collection titled An Introduction to the Periodicals of the May 4 Period (Wusi shiqi qikan jieshao), which first appeared in 1958 and was reissued in 1979. To those with the energy to wade through the six hefty volumes, the collection proved to be a treasuretrove. It not only listed all the major periodicals of the May 4 period and after, but also reprinted their Contents Pages, Editorial Statements, etc, while providing an analysis of the significance of each periodical. The latter, while written from the standpoint of the Communist Party, was nevertheless remarkably objective, even with regard to the anarchist periodicals. Toward the latter the policy was one of stating the facts then suggesting shortcomings, making it possible to sift out considerable information not only about anarchist activities but also about the considerable overlap between groups of different political persuasions during those years. It was this collection, in fact, that provided the catalyst for Nohara Shiro’s original essay.

Nohara Shiro, until his death in 1981, was a Marxist historian specializing in Chinese history and politics who had also become strongly involved in the movement to eradicate pre-war feudal and fascist influences from Japanese education and learning. The essay translated here originally appeared in his 1960 collection, History and Ideology in Asia (Ajia no rekishi to shisb). Despite his personal preference for Marxism over anarchism, Nohara’s approach to the subject is quite open-minded. The strengths of his essay are its focus upon practical organizing attempts rather than intellectual activities, and its revelation of the considerable anarchist influence upon Li Dazhao, whom the Communist Party has long claimed as its own. Whilst most of the early intellectual exponents of the anarchist idea either drifted away into obscurity, were converted to Marxism, or joined the bandwagon of the nationalist movement (some even becoming outright fascists), the organizing activities described here often became the building blocks for the subsequent communist movement. Nohara’s work is thus invaluable not only for shedding light on the role of anarchism as an intellectual stimulus for the Chinese revolutionary movement as a whole, but also for making clear the political debt owed the anarchists in terms of practical activities.

In the Commentary I have attempted to marshall additional material on themes raised by Nohara, without losing a sense of proportion. The Chinese anarchist movement, like its counterparts elsewhere, has often been overlooked because of a lack of materials, and the Commentary is an attempt to assemble previously scattered information and make it accessible to readers. The translation is a completely revised version of one that first appeared in issues 1–4 of the small magazine Libero International, published in Kobe and Osaka from 1975 to 1977. The Commentary and Introduction have also been considerably expanded and amended. In accordance with standard East Asian practice, personal names of Chinese, Japanese and Korean individuals have been transcribed with the family name preceding the given name. Chinese characters for most of the individuals and periodicals mentioned may be found in Chow, 1963.

A Note on the Pronunciation of Chinese Names and Terms

Most letters are pronounced roughly as written, with the exception of the following:

c = ts as in ‘its’

q = ch as in ‘chin’

x = hs as in ‘shin’

si = sir

zi = zer as in ‘Tizer’

Part One

Introduction

The students’ movement for democratization that erupted in China in April 1989 only to be bloodily crushed by the authorities some two months later was the latest in a series whose origins can be traced back to the beginnings of modern China’s revolutionary process. Sparked off by the death of Hu Yaobang, the former Secretary-General of the Chinese Communist Party who had been deposed in disgrace by conservatives two years before, the movement had derived further inspiration from the visit to Beijing of the Soviet leader Gorbachev, then at the height of his popularity thanks to his perestroika’ reform initiative. And yet it was not by chance that the movement also coincided with the 70th anniversary of the famous student movement of May 1919. Ironically, while the latter has been appropriated as a primary revolutionary icon by the ruling Communist Party, it was against the dictatorial style of that very party that the 1989 students were protesting. Sadly, despite the students’ insistence upon a nonviolent movement and the fact that they sought merely to urge the Party to live up to the revolutionary ideals it still claimed to espouse, the government’s reaction was as ruthless as had been that of its counterpart, the warlord regime of seventy years before.

The parallel between the two movements does not stop there. Government approval for thousands of students to travel abroad, which formed one wing of the opening-up’ (Jtaifang) policy of the ten years following the refutal of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ in 1979, closely matched the policy of dispatching students to Japan and the West for further education in the early years of this century. In both cases the initiative was an implicit recognition of the fact that stagnation had set in which could only be cured by the injection of new blood; and in both cases student demands, far exceeding the bounds of the government’s original intentions, were for fundamental reforms in the country’s political organization. For in 1989, as in 1919, changes were taking place on a worldwide scale that not only stimulated the students to press home their demands with still greater fervour than they might otherwise have had, but also caused the government to look fearfully over its shoulder, admitting the justice of many of the students’ arguments while ordering them to restrain the ‘radicalness’ of their behaviour.

Behind the students’ actions, in 1989 as in 1919, was a deep mood of patriotism that was effectively obliterated in each case by a barrage of government propaganda. In 1919 the students, a tiny minority of the population but open to the input of new ideas and current information, had watched their country being steadily divided up among the superpowers and realized that politicians in charge of government policy were in fact contributing to the disaster. It was as if the shock of that realization had galvanized them into a search for the real meaning of ‘China’. Why was the country apparently resigned to suicide? Was there any longer any meaning to being ‘Chinese’? Where was the country bound, and what was needed to guide it along the way ? In the sense that the spirit of the May 4 Movement was an attempt to redefine Chinese culture in the context of the modern world, it was far more of a revolution than its predecessor of eight years earlier which had overthrown the Qing dynasty and inaugurated a republic.

Seventy years later the 1989 students’ call for a multi-party state to replace the Communist Party’s dictatorial control over national affairs stemmed from a similar realization that the Party’s refusal to admit change was leading China toward disaster. Not least was their concern that the Party, by betraying the very values it had foisted upon the country in place of those of traditional society, had left people with no values at all. Their anxiety was fuelled by the screening the previous year of the controversial television documentary ‘River Elegy’ (Heshang’). Using the Yellow River as a symbol for Chinese civilization, the programme had suggested that the desperate efforts put in over the centuries by peasants to sustain the river in its course and prevent flooding had their parallel in efforts by successive governments to sustain the unique nature of Chinese civilization, resulting in stagnation and a refusal to admit the validity of outside ideas. The allusion to the conservatism of the present government was obvious. To concerned intellectuals, persisting on this course could only mean the continued isolation of China from the world community.

Despite government efforts to contain the controversy and the sponsoring of a stream of publications criticizing the producers of ‘River Elegy’, the debate continued. Just as students and intellectuals in 1919 had called for political reform to ‘protect our mountains and seas’ — ie, to return China to its own people — the demands for democratization in 1989 grew from the perception that the government possessed neither the will nor the energy to tackle the multitude of problems facing the country. If anything, reports of widespread pollution and defoliation throughout China over the past few years have made the issue of ‘protecting the mountains and seas’ more pressing than ever.

On May 4 1919 some 3,000 Beijing students demonstrated in protest against the Chinese government’s acquiescent attitude toward Japan’s expansionist demands. The immediate cause was the failure of the Versailles Peace Conference to return to China German colonies in Shandong province seized by Japan in 1915; the revelation that the government had tacitly agreed to Japan’s assuming control was the last straw. The officials held responsible for the government’s stance were denounced as traitors, and the May 4 demonstrations were called to force their resignation. When some students invaded the home of one of the ministers, police arrived, a fight ensued, and 32 people were arrested. This was the ‘May 4 Incident’, the catalyst for a process of tumultuous change that would end in the total transformation of China. Out of the May 4 Movement that followed the Incident grew not only the cultural revolution that would sweep away the old elite and (most of) its values for ever, but also many of the political currents that over the next thirty years would battle for control of the country. National consciousness, political parties, the labour and student movements, even the beginnings of the peasant movement, can all be traced back to ‘May 4’, the term which has come to subsume not merely the Incident itself but also the decade of social and intellectual change that had begun four years earlier.

The transformation of China’s predominantly-agrarian economy had begun during the 19th century, the result of a combination of imperialist pressure and more gradual domestic trends. In the early days native industry had little chance to expand because foreign-manufactured goods of lower price and superior quality were constantly being dumped on the market through the many one-sided trade agreements forced upon the weak Chinese government. With World War 1 and the preoccupation of the western powers with military production, however, China obtained a breathing space. Native production, especially in light industry, grew rapidly from 1914 to 1920. Investment moved from the countryside to the cities; joint-stock corporations and modern banks began to appear; capital concentration and the growth of a modern economy quickened. Merchants, always a despised group in Chinese society because of their non-productive character, transferred their operations from the hinterland to the cities with the encouragement of the new Chambers of Commerce. Their consequent interest in national rather than local markets made them a highly significant political factor, and many of them came to support the aims of the May 4 Movement. In particular, the increased influence of Japan and the return of the other imperialist powers after the war made the merchants and industrialists anxious about the future and therefore sensitive to appeals for national recovery.

The intellectual revolution which provided the initial impetus for the May 4 Movement also grew out of this process of structural change. China’s ability to maintain its social and political systems virtually unchanged for more than two millenia was primarily due to the fact that their intellectual premises had never been seriously challenged. After the Opium War with Britain in 1840–42 had demonstrated the superior might of the West, however, the first stirrings of national consciousness began to be discernible. A movement grew up around the principle that, while China’s traditional learning and institutions were superior to those of the West, in order to protect and preserve them China needed to learn Western methods and technology. Military defeat by Japan in 1894–5, though, brought another rude awakening. The lessons of the ineffective revolution of 1911, together with increasing encroachment by Japan (where the 1868 ‘Meiji Restoration’ had already begun to transform society along Western lines) convinced intellectuals that merely transplanting laws and political institutions was not enough.

Fierce nationalism, inspired by opposition to the 250-year rule of the alien Qing or Manchu dynasty, had won a transparent victory in the revolution of 1911 that established a republican system of government, but the new order was almost immediately turned into the personal dictatorship of President Yuan Shikai. Many erstwhile revolutionaries joined the government; others wasted time and lives on futile, uncoordinated insurrections; still others, once their more practical strategies showed signs of becoming a serious threat to the established order, were eliminated by presidential assassins. Following Yuan’s abortive 1916 attempt to make himself emperor and his death soon after, the country fell into the hands of local militarists or ‘warlords’.

All this, together with further imperial restoration attempts, the collusion of party politicians with the warlord governments, and the total failure to rally popular opinion for a ’Second Revolution’ in 1913, brought home all too plainly that mere nationalism was not the cure-all which many intellectuals had thought it to be. The abject acceptance by the government in 1915 of Japan’s ‘Twenty-One Demands’, intended to turn China into little more than a Japanese colony, merely underlined the hollowness of the changes that had taken place so far, and convinced many intellectuals of the need for more fundamental change. Things being what they were, it was inevitable that these intellectuals, though numbering only some ten million in 1919, would come to represent other casualties of social change in a kind of crusade to save China.

The ‘new’ intellectuals, whose contacts with modern Western civilization had often, even if only temporarily, alienated them from traditional Chinese orthodoxy, claimed that not only should Western methods and ideas be fully introduced, but also that China’s hallowed traditions themselves should be subjected to a total re-examination. In 1915, therefore, through the medium of the newly-established New Youth magazine, these intellectuals began calling for the destruction of all traditional values, ethics, social theories and institutions, and for their replacement by new ones appropriate to building a ‘new culture’ for \ China. The appeal was predominantly to young people, as the name of the magazine suggested, and Chinese students responded enthusiastically, particularly after New Youth began to be published in the vernacular style instead of the stilted classical forms that symbolized the old culture. As this ‘New Culture Movement’ gathered momentum, every aspect of the old society came under fire: the traditional family was to be abolished, arranged marriages would give way to freely-chosen love matches, filial piety would be replaced by individual equality, and the sexual double standard would be ended by the establishment of sexual equality. Old superstitions and religions were castigated in the name of scientific methods. Politics would be by and for the common people, and a literary revolution would do away with the old script intelligible only to a few thousand trained scholars, making culture available to all.

Events outside China were presenting a stimulating contrast to its own passivity. While Western democracy had been widely discredited by the Peace Conference’s decision on Shandong, the success of the October Revolution in Russia, followed by the ill-fated but still impressive revolts in Hungary, Finland, Germany, Austria, Bavaria and elsewhere showed the potential of popular uprisings. Meanwhile, the August 1918 ‘Rice Riots’ in Japan and the following year’s ‘March 1 Movement’ against Japanese colonial rule in Korea helped demonstrate that popular initiative was not the prerogative of the West.

The effects of May 4 were far-reaching. Most profoundly affected of all, perhaps, were the women — at least, those living in the cities. Chinese women were taught from childhood to be passive and obedient, sheltered from the outside world, used as pawns in family politics, rarely given any education, and not allowed to work. Foot-binding, concubinage, female infanticide, the cult of chastity preferring suicide to dishonour and so on had made Chinese women perhaps the most violently oppressed in the world. Women’s emancipation, when first mooted by progressive (male) intellectuals made aware that half China’s population was kept in virtual slavery, thus had a feeling of inevitability to it. Young women bobbed their hair, went on demonstrations, attended school for the first time, demanded a free choice in marriage and so on. The idea of ‘women’s rights’ had gradually filtered down through the few schools and publications that were available until by 1919, despite strong resistance, it had become a key motif of the intellectual and social revolution.

The modern labour movement was also a product of May 4. Foreign economic encroachment since the mid-19th century had created a small proletariat, and expansion during World War 1 had increased the number of urban workers by 1918 to about a million. Though but a tiny proportion of the entire Chinese population of 400 million or so, the anti-imperialist movement, particularly the anti-japan agitation during May 4, quickly awakened these workers to a sense of their own potential. It also brought home the advantages of organization, which in turn, by arousing the opposition of Chinese industrialists, helped encourage class awareness. Although there was no central labour organization at the time, it has been estimated that as many as 60,000 workers in 43 enterprises staged some form of strike or stoppage in Shanghai alone. Much of the activity was stimulated by the socialist clubs and study groups that had spread across the country during mid-1919.

The remaining 90% or more of the population, meanwhile, the peasants, took little part in the events of 1919. Mostly illiterate, and culturally speaking light years removed from the world of the urban intellectuals, the people of the Chinese countryside could make little of the nationalist furore enveloping the cities. Rural China, controlled for two thousand years by an unproductive landlord class presiding over an atomized peasantry in varying degrees of economic distress, had naturally changed but little as a result of the revolution of 1911, which had been barely more than a military coup. Years of inter-warlord conflicts rolling back and forth over the villages, destroying the economy and killing millions, had by the time of the May 4 Movement reduced many parts of inland China to chaos. Thus, while May 4 had meant little more to most peasants than the entertaining sight of bands of well-meaning students come to ‘share the peasants’ lives’ and to spread the message of ‘national reconstruction’, intellectuals concerned with the practical methods for creating a ‘new China’ were giving serious thought to the ’peasant problem’. Out of this concern to liberate the countryside from poverty and ignorance would eventually, after twenty years in which rural conditions went from bad to worse, come the peasant revolution that would prove stronger than either Japanese imperialism or the US- backed middle-class elite of Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek), and which would win the whole country for the popular policies of the Chinese Communist Party. China’s peasant revolution may thus also be said to have germinated in the fertile soil of the May 4 Movement.

An Anarchist Genealogy

In the China of 1919, hot on the heels of the broad-based popular movement known as ‘May 4’, a cacophony of diverse ideologies was vigorously disputing how to build upon the movement’s successes in the reconstruction of their country. One of the profoundest of those disputes, as elsewhere, was that between anarchism and ‘bolshevism’.[1]

Prior to the establishment of the Communist Party in 1921, ‘socialism’ in China had encompassed a range of creeds, from anarchism, syndicalism, guild socialism and bolshevism to Tolstoyan humanism and even the Japanese ‘New Village’ (Atarashiki mura) movement.[2] Indeed, the thinking of the earliest Chinese communists had been deeply imbued with elements of anarchism and other ideologies, and ‘bolshevism’ itself was widely viewed as no more than a faction within the anarchist movement.[3] Not until after the post-May 4 disputes did the Chinese bolsheviks genuinely manage to forge a clear direction for themselves and strike out upon an independent path.

Anarchism, along with other socialist creeds, had been introduced to China on the eve of the 1911 Revolution there by radicals exiled in France and Japan. Among the numerous articles dealing with socialism carried in the People’s Report (Minbao), organ of the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance (Zhongguo geming tongmenghui) formed in Tokyo in 1905, Bakunin, Kropotkin and other European anarchist figures were well represented. Alliance members including Zhang Binglin, Zhang Ji and Liu Shipei[4] contacted Japanese militants Kotoku Shusui, Osugi Sakae, Sakai Yoshihiko and others,[5] and with their help organized the Society for the Study of Socialism (Shehuizhuyi jiangxihui). In the journals Natural Justice (Tianyi bao) and Impartiality (Heng bao) which they subsequently launched, they began regularly introducing the ideas of Bakunin and Kropotkin.[6]

In 1906 Kbtoku Shusui, following his return from the United States, had promptly announced his conversion to anarcho-syndicalism and begun to propagate the general strike as the only road to a true revolution:

We will never, never achieve genuine social revolution through universal suffrage or by parliamentary procedures. In order to attain our target of socialism, there is no other course for us but to rely on 7) direct action by the workers acting in unison.[7]

In China, meanwhile, domestic and foreign pressure since the Boxer Uprising of 1900 had forced the Qing authorities to take steps towards establishing a constitutional monarchy based upon a system of consultative assemblies in an attempt to bolster its autocratic rule. The working class was still fearfully weak, however, and an anti-government struggle by means of a general strike was quite out of the question. Under the circumstances Chinese anarchist militants could do little but resort to ‘propaganda by the deed’ using the tactic of assassination. The backcloth to this advocacy of individual terrorism was provided by such episodes as the 1907 plot to kill all the high officials of Anhui province, in which Qiu Jin, a woman student just returned from Japan was involved, and Wang Jingwei’s attentat upon the Imperial Regent in 1910.[8]

A good example of this trend was Liu Sifu. Following his return from Japan in 1906, Liu, or Shi Fu as he is usually known,[9] undertook the elimination of local officials in support of the Alliance’s armed rising in Guangdong in 1907, and later masterminded an assassination attempt upon the Imperial Regent on the eve of the 1911 Revolution. In this way he commenced his efforts to propagate anarchism by way of undisguised terrorism.[10] His subsequent activities too, since they came to constitute the main current of the pre-May 4 anarchist movement, require a brief explanation here.

Since 1907 the anarchists Wu Zhihui, Li Shizeng, Zhang Jingjiang and, following his expulsion from Japan, Zhang Ji, had been publishing the weekly magazine New Century (Xin shiji) in Paris.[11] Sales outlets had also been set up in England, the United States and Japan, and efforts were being made to spread anarchist propaganda via overseas Chinese students and residents. Shi Fu, who had contacted this Paris group soon after the 1911 Revolution, then set up his own propaganda organization in Guangzhou called the Cock-Crow Study Group (Huiming xueshe). From August 1913 the group began to publish its own magazine, Cock- Crow Record (Huiming lu), later changed to People’s Voice (Minsheng). In the meantime, they had already put out, in the summer of 1912, not only a selection of articles reproduced from the New Century, but also a collection entitled Masterpieces of Anarchism (Wuzhengfuzhuyi cuiyan), which introduced the writings of Kropotkin and other libertarian theo- 12) rists and propagated the use of Esperanto.[12]

In the summer of 1913 Shi Fu and his fellow-anarchists also got together to found the Conscience Society (Xin she). Membership required observation of the following twelve injunctions: 1. do not eat meat; 2. do not take liquor; 3. do not smoke tobacco; 4. do not have servants; 5. do not use sedan chairs or rickshaws; 6. do not marry; 7. do not use family names; 8. do not become officials; 9. do not become Members of Parliament; 10. do not join any political party; 11 do not 13) join the military; 12. do not profess any religion.[13]

The Chinese scholar Ding Shouhe has suggested a number of reasons for China’s susceptibility to the appeal of anarchism. First, having suffered long under the corrupt rule of an autocratic monarchy, the Chinese people had come to regard governments, laws and all political activity with extreme antipathy. Second, the expanding petty bourgeois class, accustomed to backward and dispersed forms of economic organization, mistrusted and therefore reacted strongly against the idea of a strong centralized polity based upon an advanced mass-production economy. Third, when confronted by social or political difficulties everyone fell back on their own abilities: when occasion demanded some might dream of establishing an ideal society, but the idea of a fierce, protracted class struggle was repugnant to the Chinese. Finally, the traditional nihilistic influence of Lao Zi and Zhuang Zi created a hotbed for the spread of anarchist ideas.[14]

As far as the last point is concerned, it is true that certain anarchists at the time followed Natural Justice in posing Lao Zi as the father of Chinese anarchism.[15] The charge that anarchism appealed to the petty bourgeoisie, too, is more or less borne out by Shi Fu’s union activities as described below. Point number one, on the other hand, can perhaps only be fully appreciated in the context of the period between the Revolution of 1911 and the May 4 Movement of 1919. Indeed, unless this point is grasped it is impossible to understand the special significance of anarchism’s far-reaching influence during this period.

For many Chinese, the 1911 Revolution had brought a promise of better things to come, but that promise had been totally dashed by the subsequent assumption of power by Yuan Shikai, Duan Qirui and successive militarist governments. The anarchists’ profound mistrust of parliamentary politics and indeed of all political activity was thus borne out by actual events. Shi Fu’s ‘Twelve Abstentions’, therefore, especially numbers 8, 9, 10 and 11 with their air of political asceticism, struck a harmonious chord in many hearts.

Let us now return to Shi Fu’s activities. With the failure in 1913 of Sun Zhongshan (Sun Yat-sen)’s so-called ‘Second Revolution’ against Yuan Shikai, Yuan’s authority finally extended as far south as Guangzhou. Cock-Crow Record was immediately proscribed after only two issues and the Study Group closed down. In September Shi Fu himself was forced to move, lock, stock and barrel, to Macao, where he managed to publish two more issues under the title of People’s Voice before the Portuguese colonial authorities, under pressure from the Chinese Foreign Ministry, also clamped down on him.[16] He next found refuge in the Foreign Concession of Shanghai,[17] from where in April 1914 he began to put out People’s Voice once again. That July he formed a new group under the name of the Society of Anarcho-Communist Comrades (Wuzhengfu-gongchanzhuyi tongzhishe), and released a manifesto:

What is anarcho-communism? It means the elimination of the capitalist system and its reconstruction as a common-property society in which both governments and rulers shall be superfluous. To put it plainly, it is to advocate absolute freedom in economic and political life.[18]

The proposal for a ‘common-property society’ with no need for governments or rulers was intended to proclaim the group’s rejection of the post-revolutionary dictatorship advocated by the bolsheviks; ironically, however, the Chinese phrase gongchanzhuyi or ‘commonproperty-ism’, evidently coined by Shi Fu, later came to stand for that very ‘communism’ advocated by the bolsheviks.[19]

That August a strike spread among lacquer craftsmen in Shanghai, but with very little organization. Shi Fu promptly ran up a pamphlet advising them on how to conduct their campaign and urging them to organize themselves and increase their social awareness. The pattern which he outlined for their union was a revolutionary syndicalist one repudiating all political objectives. During that same month of August — whether before or after this episode is not clear — the Society of Anarcho-Communist Comrades affiliated itself to the Jura League, an international anarchist organization based in Switzerland.[20] By this time Shi Fu had clearly abandoned his former individualist anarchism for the anarchist-communism of Kropotkin. Accordingly, he threw himself into the thick of the labour movement, putting out a worker-oriented paper called the Worker’s Handbook (Gongren baojian) as an organ for the propagation of syndicalism.[21]

Back in Guangzhou barber-shop workers (with funds of 100,000 yuan, it was claimed) and tea-shop employees were inspired to form their own unions under Shi Fu’s guidance, while many other young Guangdongese, after imbibing his ideas, left China to settle in European colonies like Burma, Java and Singapore. There they either became teachers in schools for overseas Chinese or bustled about organizing the Guangdongese printers, clothing workers and hotel employees. Shi Fu himself, however, on March 27 1915, succumbed to tuberculosis in Shanghai.[22]

Despite Shi Fu’s death the subsequent development of the Chinese anarchist movement was much along the lines that he had advocated....[23] After the 1911 Revolution, and particularly after 1915, the year of Shi Fu’s death and of the beginnings of the May 4 New Culture Movement, Chinese anarchism was generally seen as having abandoned its individual terrorist associations for Kropotkin’s ‘mutual aid’ conception. It thereby re-emerged as a systematic body of thought rejecting every authority save that of science, demanding absolute liberty, and advocating the construction of an ideal utopian society.

In 1913 the radical intellectual Li Dazhao had written his essay titled ‘The Great Grief’ (Da-ai pian) in which he decried the complete untrustworthiness of ‘democracy’ and ‘political parties’ under warlord rule.[24] However, with Japan’s infliction of her ‘Twenty-One Demands’ in 1915, the conclusion of the Nishihara Loans in 1917, and the signing of the Sino-Japanese Military Mutual Assistance Conventions in 1918,[25] Li’s mistrust turned to alarm as he came to feel still more keenly the crisis facing the Chinese people. In order to overthrow warlord rule and establish a new society, it was necessary to go to the very roots of the problem, something which had not hitherto been attempted. In a 1916 essay, ‘Spring’, Li thus stressed as follows:

From now on, the problem for humankind in general and the Chinese nation in particular is no longer merely to seek blindly to survive, but one of rebirth, rejuvenation, and reconstruction.... Young people who are self-aware can burst through the ensnarling webs of history, smash the prison of stale ideas.... free their present selves, destroy their past selves, and urge the selves of today’s youth to clear the way for those of tomorrow.

The theme of youth persisted right up to Li’s 1918 essay ‘Now’ (Jin), clearly reflecting young people’s contemporary demands for a ‘change in values’.[26] Ye Shaojun’s novel Teacher Ni (Ni Huanzhi) framed those demands succinctly:

The revamping of all values has become a popular ideal. Why have hitherto-sacred concerns become of no import?.... Doubts are bubbling over, self-questioning is rising in pitch. The time is past for worrying over the minor details — let us boldly pull down and rebuild the whole lot![27]

This passage expressed perfectly the May 4 New Culture Movement’s attack on the old morality and ethics that sustained warlord rule, and its hopes for constructing a new Chinese identity. To this end, the movement took up and used as weapons in its struggle not only evolutionism and other modern western theories brought into China since the closing years of the Qing era, but also the various schools of socialism and the ideas of Bergson, Dewey and Russell.[28] Among the young people and students of the time, however, by far the most popular books were Tan Sitong’s Philosophy of Benevolence (Renxue), Kang Youwei’s One World (Datong shu), and, representing the West, the ideas of Kropotkin and Tolstoy.[29]

Amidst all this, it was anarchism that for a time seized the emotions of young students who, along with many other people, translated their fierce desire for a reorientation of values into a total rejection of traditional authority itself. With their suspicion and mistrust of ‘politics’, they came to dream of setting up an ideal society at one stroke. During the May 4 period, therefore, it was inevitable that the lingering influence of Shi Fu should finally stretch as far as north China too. The credo of the Society for Promoting Virtue (Jinde hui) formed by Cai Yuanpei and others in 1918, for example, clearly echoed the ‘Twelve Abstentions’ of the Conscience Society.[30] In May 1917 Beijing University students had already formed an anarchist group, the Reality Society (Shi she), whose prominent members included Huang Lingshuang, Ou Shengbai and Zhao Taimou. In their occasional magazine Notes on Liberty (Ziyou lu) they explained Kropotkin’s mutual aid theory, and argued for a workers’ general strike to bring about a socialist revolution.[31] Elsewhere, too, new anarchist groups were appearing, like the Masses Society (Chun she) of Nanjing with its magazine The Masses (Renchun) and the Peace Society (Ping she) of Taiyuan with its Peace (Taiping). By March 1918 Wu Zhihui had begun publication in Shanghai of an anarchist monthly called Labour (Laodong), where Chinese readers first received the message of May Day.[32]

The considerable overlap among the editors of and contributors to these magazines suggests that the groups were in close contact with one another. As Huang Lingshuang said, all of them were really just extremely small free-wheeling outfits, with but a minimum of ideological unity. They were viewed by the warlord-controlled government, however, as treasonable, immoral and ultra-extremist, a clear measure of how strongly their proposals appealed to the current mood of Chinese intellectuals.

In February 1919[33] the Japanese Diet had heard the following speech from one of its members:

Broadly speaking, the socialists in Japan may be divided into five varieties. Among them, the state socialists are not in the least dangerous — on the contrary, they should be encouraged. Next come the pure Marxian socialists who, whilst not to be encouraged, pose no threat. Then there are the communists, visionaries admittedly, but not to the extent of posing any threat to social order. Fourth and fifth, respectively, come the plainly dangerous syndicalists with their advocacy of revolutionary labour unionism, and the anarchists, who seek to do away with all authority and advocate absolute liberty for the individual.

Conditions in China, where the union movement lagged far behind that of Japan, were thus somewhat different. Still, the Chinese ruling class kept a firm grip on the situation. As a result, during the course of 1918 the People’s Voice, Reality, Masses and Peace groups were all forced to close down. In January 1919 they merged as the Progress Society (Jinhua she), and began to put out a new monthly, Evolution (Jinhua), whose third issue (March 1919) was a special one in commemoration of Shi Fu, but before long this too was proscribed, a victim of the furore surrounding the May 4 student movement.[34] Let us now take a look at how things were on the campus of Beijing University, particularly the activities of the anarchists there, by way of Xu Deheng’s ‘Recollections of May 4.[35]

Ideologically speaking the campus was divided into three trends, the most influential being the New Youth (Xin qingnian) group represented by Chen Duxiu, Hu Shi and Li Dazhao.[36] Although the three men had all been initiators of the New Culture Movement, by 1919 their paths had already begun to diverge. To Li Dazhao’s piece ‘The Victory of the Poor’, for example, Hu Shi retorted with ‘The Victory of Democracy over Militarism’, revealing their fundamentally polarized conceptions of democracy. Again, to Hu’s insistence upon “more study of problems, less talk of isms”, Li issued a refutation, precipitating a clash over the issue of theory versus practice. Among Hu’s student followers were Fu Sinian and Luo Jialun, editors since January 1919 of the monthly New Tide (Xin chao) and active in the vernacular speech movement.[37]

The second of the three trends, though far less influential, was the so-called National Heritage Faction represented by Gu Hongming, Huang Kan and Liu Shipei, which published the monthly National Heritage (Guogu). Extremely conservative, the group made hardly any mention of politics whatsoever.[38]

Then, of course, there were the anarchists, the main focus of this essay. Li Shizeng and Wu Zhihui were there, and at first even University Chancellor Cai Yuanpei demonstrated sympathy with their aims. The combination of highly backward political conditions, low student comprehension of the social sciences, and the attractiveness of these ‘eminent scholars’ ensured that, for a time, considerable numbers of students would flock to the anarchist ideal.[39] Best remembered among the latter are Huang Lingshuang and Ou Shengbai. Denying the need for either state or family, these two symbolized their stand by refusing to use their family names.[40]

The ‘Recollections’ contain Several noteworthy points concerning the 1919 student movement, but before discussing them it seems worthwhile to show how the ground for May 4 had already been prepared by the students, particularly those in Beijing, in the previous year’s campaign against the Sino-Japanese Military Mutual Assistance Conventions.

Japan, which was then plotting intervention against the new Soviet regime in Russia, had devised the Conventions as a Sino-Japanese ‘alliance’ to defend the Far East against mutual enemies. To this end, Japanese and Chinese troops would ‘cooperate’ in north Manchuria, and dispatch a ‘joint’ force for operations ‘beyond the Chinese frontier’ : ie, in Siberia. Japan would also appoint personnel to ‘maintain mutual contacts’ with the Chinese army, and establish ‘jointly operated’ military bases on Chinese territory. The real objectives of this ‘mutuality’, of course, were no less than the subjugation of the Chinese army to Japanese control, and the subordination of China itself through the system of military bases.

Chinese students in Japan, as soon as they got wind of the Conventions, organized a protest rally, only to suffer numerous arrests and injuries at the hands of the police. Their anger complete, in May they returned as one to China. Once back in Shanghai they formed the National Salvation Corps of Chinese Students in Japan, founded a paper called the National Salvation Daily (Jiuguo ribao), and sent representatives to Beijing to appeal their case to the students there.[41] As a result, on May 21 1918 more than 2,000 students from Beijing University, the National Higher Normal College, the National Industrial College, the College of Law and Political Science, and the College of Medicine demonstrated against the Conventions.

While it had no direct effect, the anti-Conventions movement did provide an opportunity for the students of Beijing and Tianjin to get organized. The most significant result was the establishment soon after of the Students’ Society for National Salvation. In July Beijing and Tianjin representatives went south where they contacted other students in Jinan, Nanjing and Shanghai, and within a month a nationwide organization had been created. In October preparations began for a new monthly, the Citizens’ Magazine (Guomin zazhi), intended to act as a liaison medium among the scattered groups. The Citizens’ Magazine Society, founded at the same time, had over two hundred members, each of whom paid five yuan into a fund to finance publication of the magazine. Many of them were active in the subsequent May 4 demonstrations.[42]

According to the ‘Recollections’, the anarchist students of Beijing University did not take part in the 1918 agitation. Neither, for that matter, did the New Tide group, but it was the anarchists above all who poured scorn upon their fellow-students’ patriotic agitation, deriding patriotism as a decadent ideology. Since their opposition is said to have been behind the adoption of the name Students’ Society for National Salvation instead of the original name of Students’ Patriotic Association, it may be gathered that the anarchists wielded considerable influence among their fellow-students. Moreover, few Citizens’ Magazine Society members were as yet capable of holding their own in an argument with the cosmopolitan anarchists.

Unite With the Toiling Masses!

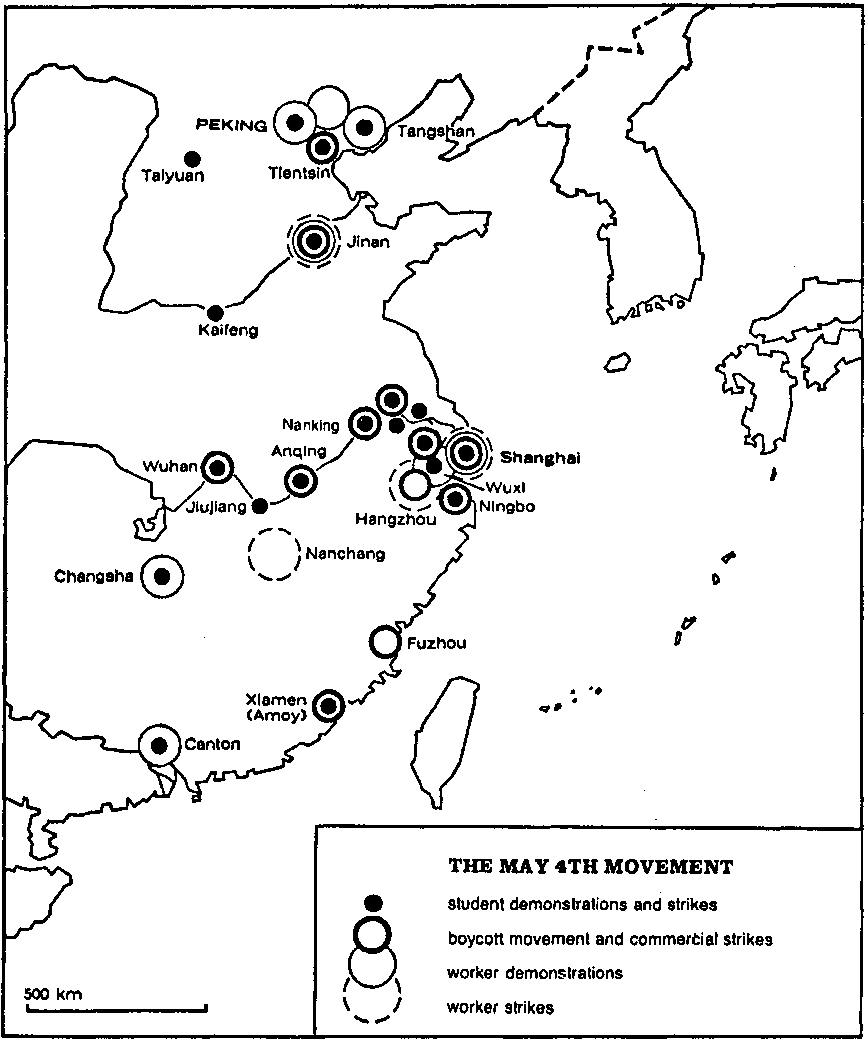

In April 1919 the Versailles Peace Conference granted Japan the former German colonial rights in Shandong province, sparking off nationalistic fury at almost every level of Chinese society. Since the failure of China’s international diplomacy was clearly a result of the ‘nation-selling’ policies of the Beijing government, this nationwide anger fused with and further strengthened the existing opposition to warlord rule, already intensified by the New Culture Movement. The first to translate this emotion into actual activities were the students. The slogans coined for their demonstration on May 4, ‘Fight for Sovereignty Abroad, Smash the Traitors At Home!’, ‘Refuse to Ratify the Peace Treaty!’, ‘Fight to Retrieve Shandong!’, ‘Bury the 21 Demands!’, ‘Boycott Japanese Goods!’, ‘Punish the Nation-Selling Traitors!’, ‘China for the Chinese!’, and so on soon turned the original Beijing-centred student movement into a national shutdown by merchants, to be followed after June by a wave of workers’ strikes. Under pressure from this unified nationwide resistance, the government finally declined to sign the Peace Treaty.[43]

According to Xu Deheng’s ‘Recollections’, Beijing University student groups who had previously pursued independent paths now put politics behind them as they joined forces at the forefront of the May 4 Movement. The anarchists were no exception to this trend; on the contrary, it was for them a golden opportunity. Of course, from their standpoint all political activity was pointless; on the other hand, if the movement could be turned in the direction of the workers’ general strike which they had advocated for so long, nothing could have been better. However, it has to be said that their decision to participate in the May 4 Movement owed less to such clear political calculations than to their inability to stem the force of an irresistible tide. The calculating was to begin only after May 4.

The organizational leadership of the May 4 Movement was quite independent of established groups and political parties. When word of the Peace Conference’s humiliating decision reached Beijing, the Citizens’ Magazine Society, New Tide Association, Work-Study Society (Gongxue hui) and other influential student groups had immediately held a meeting at which they resolved to stage a mass demonstration on May 7, ‘National Humiliation Day’ (the anniversary of Japan’s ultimatum on the 21 Demands). At a later meeting of Beijing student representatives held on the university campus on May 3, the demonstration was brought forward to the next day. The organizations set up the previous year by the Students’ Society for National Salvation were transformed into students’ unions, first in Beijing then elsewhere, culminating on June 16 with the formation in Shanghai of the Students’ Union of the Republic of China.[44] It was precisely these local students’ unions that were to provide the organized leadership for the movement that followed.

The already-mentioned Work-Study Society, formed by students and graduates of Beijing Higher Normal College in February 1919, was one of the groups destined to fire the opening shots in the campaign. Its work-study principles, as we shall see later, were remarkably anarchistic. Always present behind the scenes of the May 4 Movement, frequently playing a militant role, the group has been credited with planning the assault on the homes of the three government ministers held responsible for acceptance of the 21 Demands and conclusion of the Nishihara Loans: Minister of Communications Cao Rulin; Minister to Japan Zhang Zongxiang; and Director-General of the Currency Reform Bureau Lu Zongyu.[45]

May 4 left behind it a rich legacy, not least the realization among the people as a whole that the combined struggle against feudalism and imperialism was a national issue. Another lesson was that the decisive factor in the struggle had been the power generated by the united front of the mass organizations formed at every level of society. Thus was born, in July 1923, the Great Anti-Imperialist League comprising some fifty organizations including the Students’ Union of China, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce and the Chinese Federation of Labour Unions.

Sun Zhongshan, who at the peak of the May 4 Movement was staying in Shanghai, told student representatives who came to plead for his support that he was powerless to help them. Nevertheless, in an address to the World Association of Chinese Students on October 18 1919 Sun exclaimed:

Even in so short a space of time... what tremendous things this student movement has achieved! I now know that unity is strength. Sun then sought the students’ support for his own ‘Constitution Protection Movement’. Moreover, in a letter to overseas Nationalist Party members in January 1920 he pinned his hopes upon the ideological changes wrought by May 4, and highly appraised the New Culture Movement. In fact the Chinese Revolutionary Party (Zhonghua gemingdang), over which Sun had wielded dictatorial control since its founding in 1914, had already renamed itself the previous October as the above- mentioned Chinese Nationalist Party, the first step in its transformation from a secret society-style organization into a mass political party.[46]

Mao Zedong also demonstrated the profound lesson learned from May 4 in his ‘Great Union of the Popular Masses’ (Minzhong dalianhe), published in the Xiang River Review (Xiangjiang pinglun) in July and August 1919. This article had strong repercussions, and its importance was stressed by a representative of the Shanghai Students’ Union in the China Times (Shishi xinbao) on the movement’s first anniversary.[47] In his article Mao singled out the Students’ Union of China and the National Salvation Societies formed in various quarters as the two most significant groupings spawned by May 4.

Another important political thinker to feel the impact of May 4 was Li Dazhao. Li took up the issue of ‘personal liberation’ raised by the New Culture Movement, and, by linking it to the May 4-inspired ‘Great Union of the Popular Masses’ idea, evolved the conception that it would be achieved in the process of struggles waged by individuals within their organizations. It was a conception which would revamp modern political thought in Asia, and an example of what is meant by the contention that May 4 was the ideological take-off point for the New Democratic Revolution in China. Chinese scholars have even seen in the wartime National United Front the germination of the ‘Great Union of the Popular Masses’ conception.[48]

Among the new organizations that appeared as a result of May 4 were the ‘Street Unions’ (Malu lianhehui) formed in Shanghai and other big cities by merchants and shop proprietors. These unions differed fundamentally from the old commercial guilds, which had become the creatures of successive warlord governments. In later years they were to become active in campaigns for civil rights.[49]

The peasants, however, who were of course the great bulk of the population, remained quite excluded from the popular movement of 1919. To be sure, Mao Zedong and Li Dazhao were showing great interest in the peasant issue, but they had yet to take any practical measures. Then there were the efforts of a group of Beijing University students who, in March 1919, had set up the Commoners’ Education Lecture Corps (Pingmin jiaoyu jiangyantuan) with the objective of increasing the common people’s knowledge and awareness. Inheriting the New Culture Movement’s twin concepts of ‘science’ and ‘democracy’, they had initiated an enlightenment programme aimed particularly at village dwellers, but after the spring of 1920 their message too was confined to a lecture hall set apart for them on the university campus.[50]

While Chinese scholars have attributed this failure to official obstruction or financial difficulties, it seems far more likely that the inability of the Corps members to shake off their inherent didacticism came up against a brick wall in the villages themselves. The unbridgeable gulf that persisted during the May 4 era is treated in the writings of Lu Xun.[51]

For a time, then, the problem of how to organize the working class remained the movement’s central concern, but in order to get so far, a certain turning point had had to be manoeuvred. As the example of the student movement showed, the posture assumed by the May 4 agitation was one of seeking to force the government to accept its demands by a combination of petitions and propaganda among the masses. Even after May 4, however, the government, bowing to Japanese pressure, ordered provincial authorities to suppress the boycotts of Japanese goods. Subsequently, in January-February 1920, it even clamped down on students in Beijing and Tianjin protesting against the opening of direct negotiations with the Japanese government on the Shandong question. In both cities the Students’ Union, the Teachers’ Union and the Federation of All Organizations of China (Quanguo gejie lianhehui) were ordered to dissolve.

As the confrontation with the government intensified, the more radical students were already beginning to tire of petitions, protest demonstrations and the like, and their tone gradually began to change. From things like dismissal of the nation-selling politicians, opposing the signing of the Peace Treaty, and a boycott of Japanese goods, they now began to advocate the wholesale overthrow of the present government and the reform of the country’s social structure. The Nationalist Party’s organ Weekly Review (Xingqi pinglun) of Shanghai highlighted this trend in an article titled ‘The Past and the Future of the Student Movement’:

Up to now the movement has been one concerned solely with foreign policy issues; from now on it will be a movement addressing itself to fundamental social problems... a movement through which the plundered class shall overthrow the plunderers, and all the people of the world become workers ! (No. 46, April 18, 1920)

In this way the effect of government repression was to push concern with social change, hitherto submerged beneath the students’ absorption with resistance to imperialism and feudalistic ideas, to the forefront of their consciousness. Their vision of the form that change would take was given shape by the decisive role of the working class in the victory of May 4; that same energy, hopefully, could now be put to use to destroy the existing order and construct a new society. As a result the relative merits of anarchism and various socialist creeds became the subject of debate within many of the student groups. Deng Yingchao’s ‘A Memoir of the May 4 Movement’ gives an example.[52] Within the Awakening Society (Juewu she), an organization formed in Tianjin in September 1919 by progressive male and female students (who included Zhou Enlai), such arguments took place constantly, though no-one as yet possessed any firm belief. As for communism, it was simply an ideal society, where you had only to work to the best of your ability for all your desires to be met. Exposure to the vicious savageries of the warlord governments, however, indubitably for a time made anarchism the prevailing trend among the students.[53]

As examples of that trend, it is possible to single out the Beijing University Students’ Weekly (Beijing daxue xuesheng zhoukan), founded as the official organ of the students’ union in January 1920; Struggle (Fendou), put out by the Struggle Society, a small anarchist group established at Beijing University soon after May 4; and Zhejiang New Tide (Zhejiang xinchao), established in November 1919 and edited by teachers and students of the Zhejiang Provincial First Normal, First Middle and other schools in Hangzhou.[54] The change of tone of the Students’ Weekly was particularly striking, and gives a vivid illustration of the turning point mentioned above.

As originally conceived, the magazine was intended to be an ideological forum for the entire student body: in line with Chancellor Cai Yuanpei’s principle of ‘broad-minded tolerance of diverse points of view’ (jianrong binghao), no single ‘ism’ or theory was to be promoted within its pages. Up to its fifth issue, therefore, it continued to reflect the trends of the New Culture Movement period, for which the ‘mass movement’ meant no more than conducting academic research, importing new scientific methods, seeking ideological breakthroughs, and rebuilding the cultural framework. What is more, the tasks of cultural reconstruction and social leadership were seen by these intellectuals as devolving upon them alone; one must look hard to find any suggestion of the need to change themselves by learning from working people.

With the upsurge in the student movement that accompanied the negotiations on the Shandong question after February 1920, the magazine’s tenor steadily began to break through those limitations. In response to the February movement, the Beijing government had announced that “of late ... people in various quarters have organized illegal groups in which they engage recklessly in discussions of politics and thereby disturb the security of the realm.” Several groups including the Beijing Students’ Union were consequently ordered to disband. In response the Students’ Weekly’s ninth issue (February 27), in an article titled ‘Dissolution! Dissolution! Illegal Dissolution!’, argued that the Public Order Police Law invoked to justify the dissolution itself infringed the Constitution: drafted by a parliament that had been no more than a rubber-stamp for Yuan Shikai’s policies, it too was illegal. What was more, the warlord-bureaucrat clique then controlling the government, known as the ‘Anfu Club’, was itself an illegal organization, so why did the Police Department not dissolve it as well? While those in power are allowed to sell the country out and create chaos, deplored the writer, the powerless are forbidden even to utter the word “patriotism” !

In the following issue (March 7), an article titled ‘A Refutation of Riots’ argued that “laws and institutions created by the state are ultimately designed to protect the interests of the capitalists and to suppress those of the workers”. When such an arbitrary system provokes plans for “general strikes” and “overthrowing the government”, the rulers label such tactics as “riots”, but for the people they are simply extraordinary methods forced upon them by the need to break out of the extraordinarily onerous conditions they live in. “As citizens of a republic they have the right to express their opinions concerning important national affairs — this is agitation, not ‘rioting’, and the sole criterion should be not whether a movement is violent or nonviolent but whether its motives are good or bad.” Accordingly, the popular anti-monarchical movements in Russia and Germany which sought political reform and an improvement in people’s living conditions were not ‘riots’. On the other hand, the Japanese government’s suppression of the Korean Independence Movement, Yuan Shikai’s attempt to make himself emperor, and the present government’s armed interference in the students’ patriotic movement are all motivated by malicious despotism, and it is those which should be considered as true ‘riots’. “In a stagnant and poverty-stricken country like ours is today”, the writer summed up, “is there any other way to break down these irksome barriers than to resort to deeds of a startling nature?”

Although this piece still held up the Provisional Constitution as the basis for the right to resist, the signs of change were already clearly visible. The new course, apparent in issues six and seven and growing steadily stronger thereafter, led towards anarchism. The addition to the editorial board of anarchist members of the Reality Society like Huang Lingshuang, Chen Youqin and Huang Tianjun undoubtedly provided much of the impetus for this drift.[55] In issue six, an article titled ‘Governments and Freedom’ had argued: “In an era of governments there can be no freedom for the people. From now on we must give up the illusion that governments are divinely prescribed”. From issue seven onwards, introductions to Kropotkin’s theories and editorials discussing anarchism appeared more and more frequently, and issue seventeen (May 23, 1920) was actually given over to an ‘anarchism special’. One article in this issue, ‘The Meaning of the Anarchist Revolution’, explained as follows:

Direct action by the workers, the driving force of the revolution, will return the entire means of production — fields, factories, mines and machinery — to public ownership, thus abolishing the private property system. At the propaganda stage of our activities, we cannot and must not seek to avoid radical methods. Our objective is to arouse society and pressure the government, so we must devise effective propaganda without questioning the methods.

Another article, ‘Anarchism and Socialism’, took an unmistakeably anarcho-syndicalist line:

The most rapid means for the realization of anarchy is the general strike. Naturally, the more tightly organized the workers’ groups are, the more quickly it can be attained. However, many Chinese workers are uneducated, and to create anarchy overnight would be difficult. As anarchists, therefore, our most pressing tasks at this time are, first, to propagate anarchist ideas as energetically as possible; and second, to raise the workers’ educational level so as to give them the ability to govern themselves and resist attempts to lead them astray.

Already, the implications of ‘direct action’ had come a long way from the “deeds of a startling nature” — within the limits of the Provisional Constitution — proclaimed earlier.

References to anarchism could also be found in other issues of the magazine. Concerning direct action, Kropotkin’s ideal society was invoked:

The workers will run the factories directly, and return the organs of production which have been plundered by the capitalists to public ownership. After that both production and consumption will be communal, based on the principles of liberty. (‘Congratulations on May Day’, issue number 14)

As to prospects for the future:

Workers of the whole world, irrespective of national boundaries, will organize labour boards at strategic points; these will take over the planning responsibilities historically assumed by so-called governments. (‘Labour’s Great Enemy and its Future Role’, same issue)

This second article, which resounded with the tenor of anarchist cosmopolitanism, also described the October Revolution in Russia as only the first stage in the liberation of the proletariat, which for its ultimate victory would have to await the anarchist revolution.

At the same time that the tone of the Beijing University Students’ Weekly was experiencing this sudden transformation, the Zhejiang New Tide’s programme for social change, as outlined in its ‘Opening Statement’, also displayed a clearly anarchistic tone:

Our ideal is a society based upon liberty, mutual aid and labour. In order to bring prosperity and progress to people’s lives, we must resolutely smash all politics, laws, states, families, impotent theories, customs and habits which stand in the way!

The Statement also stressed that the mission of reforming society could only be assumed by the workers and peasants. It divided the world into four classes, politicians, capitalists, intellectuals and workers, and continued:

The classes of politicians and capitalists, being the root source of slavery, competition and plunder, are the principal opponents of liberty, mutual aid and labour, and are therefore incapable of creating social change. The class of intellectuals too, since it assists the former in their crimes against society, is equally incapable. Only the class of workers, the vast majority of the world’s population, can discharge the responsibility for mutual aid and labour. Moreover, since their lives are filled with misery they must take the responsibility for reforming society, however much they may shrink from it.

Enlightened members of the intelligentsia must cast off their class preconceptions, throw themselves into the world of labour, and become as one with the toilers .... Our hope for the future is that, in the first place, the students will become aware and join forces before going on to promote similar awareness and unity within the labouring world; in the second stage the students’ and labouring worlds will join forces; finally, the students will all become workers, and the labouring world move toward one great federation. If all the students threw in their lot with the workers, the aim of reforming society could be easily attained.

Deng Yingchao, who had experienced the May 4 student movement as a 16-year old pupil of the Tianjin-Zhili First Girls’ Normal School, was not then aware of the need for such things as the need for intellectuals to unite with the workers and peasants. Yet, she relates in her ‘A Memoir of the May 4 Movement’, she felt intuitively that the students alone could not save China, that they must go beyond their limited capacities and awaken all their compatriots. What was no more than an inkling for her, meanwhile, had already been refined by the Zhejiang New Tide into a union of intellectuals, workers and peasants. The era of Illuminati-style politics had passed.

Their experiences in the May 4 Movement brought home to the youthful students the fact that not only destruction, but even the construction that would follow it required the strength of the working class to succeed. How to ally with and organize the workers consequently became a problem of major proportions for them. Accordingly, went the Zhejiang New Tide programme, intellectuals could not merely act as purveyors of political education from some foreign haven.[56] They had to derly their very existence as intellectuals, casting in their lot with the working class. At the same time as raising the latter’s consciousness, they would also remake themselves, finally blending into the workers’ midst. The overall strength of the working class would thus be increased, allowing itself to free itself by its own efforts, and thus making it possible to commence the task of constructing a society based on liberty, mutual aid and labour.

Certain Chinese scholars, holding up Li Dazhao’s conception of a ‘union of intellectuals and workers’ (expounded in his 1919 article ‘Youth and the Villages’), have insisted that the principle of uniting with the labouring masses was first proclaimed by the early Chinese communists, whose understanding of Marxism had been deepened by the lessons of the October Revolution. This is not quite true. The crucial differences between the Chinese Marxists and the anarchists and others would appear elsewhere. That the ideological principle of uniting with the toilers was shared by both anarchists and communists at this point in time is left in no doubt by the programme for social reconstruction of 57) the Zhejiang New Tide.[57]

The best source of information in English on the magazines of this period is Chow, 1963. Most of the information given here, unless otherwise stated, is taken from that source.

Part Two

The rise and fall of practical activities

How did the anarchist students initially seek to realize their plans for social reconstruction? The activities of the ‘Work-and-Learning Mutual Aid Corps’ (Gongdu huzhutuan) movement, which spanned a period of some six months following the Corps’ founding at the end of 1919, were one example.[58] Centred on Beijing University students and supported by Hangzhou students from the Zhejiang New Tide group, members included the founder Wang Guangqi, Luo Jialun from Beijing, and Shi Cuntong and Fu Linran from Zhejiang. Financial support was provided by several well-known intellectuals including Cai Yuanpei, Chen Duxiu, Hu Shi, Li Dazhao and Zhou Zuoren.[59] The movement also seems to have sprung up among students in Shanghai and Tianjin.

What the Corps students did, basically, was to promote in one small corner of Beijing a self-sufficient group lifestyle in which members, in addition to their studies, would work at least four hours a day, contributing their income to a pool which paid for living expenses and other outlays. Some opened printing shops, restaurants and laundries for students and teachers; others even tried selling handicrafts and so on. While there was little to distinguish this superficially from the life of the average student, their programme was in fact a sincere effort to tackle the problem of what was to become of China in the post-May 4 era. Believing that the class contradictions in society stemmed from the separation of mental and physical labour, they sought to create, by their own efforts in one isolated enclave, the prototype of a new society in which the two would be reunited, and from where they could begin to spread their influence to society at large. Wang Guangqi summed up their aspirations in issue No. 7 (January 1920) of their magazine Work-and-Learning Mutual Aid Corps:

The Work-and-Learning Mutual Aid groups are the embryo of the new society, and the first step in the realization of our ideals .... On paper we advocate a social revolution every day, but we have yet to begin to put it into practice. Our mutual aid organization is just the starting point for our real movement.... If it is successful, we can gradually expand it and simultaneously begin to realize the ideal of ‘from each according to their ability; to each according to their needs’. This movement should indeed be called ‘a peaceful economic revolution’. [60]

Similar ideals were invoked in an article in issue No. 2 (August 1919) of Young China (Shaonian Zhongguo).[61] Entitled ‘My Plan for Creating a Young China’, it too advocated the establishment of ‘Small groups’:

We must escape from the confines of the old society and head for the wilderness and forests, where we can create a truly free, truly egalitarian association. Then, by promoting economic and cultural autonomy through cooperative labour, we can cut ourselves off completely from the corrupting influence of the old society. After that we will set about the rebuilding of the latter on the pattern of our own society. Unlike the socialist parties of Europe, we do not declare war on the old society by the method of armed insurrection.

Strongly reflecting the influence of the currently-popular ‘New Village’ movement of the Japanese utopian Mushanok6ji, the group’s proposals ultimately amounted to a mere caricature of the concept of ‘uniting with the toiling masses’. Yet these students threw themselves dedicatedly into the work they chose, and, when Hu Shi dismissed their typical ‘poor student’, haphazard ways of making ends meet as no different from those of American students, they must surely have been deeply resentful.[62])

The previously-mentioned Work-Study Society of Beijing Higher Normal School, on the other hand, openly advocated anarchy, and made a fundamental distinction between their own doctrine of work-study and the position of the Mutual Aid Corps. Still, there was nothing to choose between them as far as practical activities were concerned, and both experiments ultimately ended in disappointment. Shi Cuntong, in a self-critical piece, described the failure of the Mutual Aid Corps as follows:

Present-day society is organized on a capitalist basis, and the capitalists keep a firm grip on all capital resources. There is absolutely nothing we can do about that, and to imagine regaining control of those resources is a mere pipedream! Pitting our feeble strength against such a treacherous, vicious society as this-how could we but be defeated? We tried to rebuild society, but found we could not even penetrate it, even after creating the Work-and-Learning Mutual Aid Corps. Rebuilding society? It was never even on the cards! From now on, if we want to rebuild society we must plan to do it wholesale and from the very roots!

Piecemeal reforms will get us nowhere. As long as society is not reformed at the roots, no experiments in new lifestyles are possible. So long as such experiments fail to distance themselves from everyday society, it follows that they will always be under its sway, and consequently come up against countless obstacles. The only way around this is a joint uprising of the peoples of the whole world, which will uproot those obstacles once and for all... ‘To rebuild society, we must gain entry into the capitalist controlled means of production. ‘ This is our conclusion.[63]

Dai Jitao too, then a supporter of Marxism, looked back on the failure of the Mutual Aid Corps and counseled the students to go into the capitalist-controlled factories where, toiling side by side with the workers, they could then try to seize their leadership.[64]

Accordingly, a number of the more serious anarchists, among them one Huang Ai, began to throw themselves into syndicalist activities. In May 4 days Huang had been a Tianjin Students’ Union delegate. Subsequently, at a joint preparatory meeting for the ‘May 30 Petition Movement” Huang clashed bitterly with the General Secretary of the Beijing Students’ Union Zhang Guotao over the advisability of such a movement.[65] He and his supporters’ position — that even though it would not achieve much in itself such a movement would effectively expose Premier Duan Qirui’s collusion with the Japanese, prevent direct Sino-Japanese negotiations on the Shandong question, and awaken the entire people to the situation -eventually triumphed. Huang was arrested twice during the May 4 agitation, and early in 1920 returned to his native Hunan province in central China. There, in November he and another comrade named Pang Renquan organized the syndicalist Hunan Workers’ Association (Hunan laogonghui) in the provincial capital of Changsha.[66]

The Japanese historian Suzue Gen’ichi writes of another incidence of syndicalist organizing activities:

In Shanghai there was an organization known as the Chinese Wartime Labourers’ Corps (Canzhan Huagongtuan), a section of which showed syndicalist tendencies. In practice, though, the part it played was minimal, and it amounted to little more than a loose group of Chinese workers of various kinds linked solely by the fact that they had all worked along the French border during the war in Europe. There was very little of the labour union about it, whether of the industrial or the craft variety.

On the other hand, there was also a second group of French returnees, the Diligent Work and Frugal Study Association (Qingong jianxuesheng tuan) students. Sent to France after the war ended through a scheme arranged by Wu Zhihui to help poor students, on arrival they had found their lives to be all work and no study, and had promptly returned to China. Among them were not a few who had been deported for their attempts to form a communist party while in France, but many others had returned as syndicalists, and were becoming involved in practical activities.[67]

This latter group evidently owed something to the influence of the New Century Society formed in Paris at the end of the Qing dynasty by Wu Zhihui and Li Shizeng, but little is known about the actual activities of either of these two factions.[68]

Meanwhile, following the foundation under Comintern auspices of a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) core group in Shanghai in May 1920, similar communist groups were established in Beijing, Wuhan, Changsha, Jinan and Hangzhou, as well as in Paris and Tokyo (the names varied from place to place: some were simply called Societies for the Study of Marxism),[69] and members began to apply themselves to the task of organizing labour unions. The following 2ol or three examples were typical. In mid-1920 the Shanghai group established in Xiaoshadu a Workers’ Spare-Time School, where they began political education classes in Marxist theory; in November and December of that year China’s first communist-led labour unions, the Shanghai Machine-workers’ Union and the Shanghai Printers’ Union were formed; and in January 1921 the Beijing group followed with another Workers’ Spare-Time School in Zhangxindian leading to the establishment of the Zhangxindian Labour Union that May.[70] With the membership of these groups as its nucleus, in July 1921 the CCP was finally inaugurated, followed by the Chinese Labour Union Secretariat, whose avowed role was to promote the development of the labour movement by setting up workers’ organizations and directing strikes.

During this period, arguments between anarchists and communists continued unabated even within the communist groups. The Beijing group, for example, originally numbered Huang Lingshuang, Ou Shengbai, Yuan Mingxiong and other anarchists among its members. During discussions on the provisional draft for a general party programme which the group had independently drawn up, however, Huang and the others fiercely opposed a clause advocating the dictatorship of the proletariat, and in the end withdrew from the group. As anarchists they were all in favour of revolutionary activities, meaning direct political action that negated the present system; they rejected totally, as strategies for the pre- and post-revolutionary periods respectively, both parliamentary politicking and the seizure of political power leading to a dictatorship of the proletariat under a revolutionary government.

In line with this kind of reasoning, the anarchists, unlike the communists, sought to promote the labour movement independently of everyday political activities. This debate was the keystone of the anarchist-communist struggle in all countries; in China, like elsewhere, it never managed to get beyond the realms of abstract polemic. To go into the details of the argument would be extremely tedious, and I propose to ignore it.[71] Even in Guangdong, where Shifu’s influence persisted, the same conflict took place, and eventually the anarchists either withdrew from the communist group or were converted to Marxism.

Let us now pick up the string of Huang Ai’s story once again. After returning to Hunan in June 1920, as I have said, Huang and Pang Renquan set up the Hunan Workers’ Association (HWA) in Changsha in November. Its aims were to raise both the living standards and the educational level of local workers. The original membership consisted of students, mostly from Huang’s and Pang’s alma mater, Hunan Jiazhong Technical School. Gradually, technicians and workers of the No. I Textile Mill and the local mint joined, followed by construction workers, machinists and barbers. By the time of the December 1921 strike at the No. 1 Textile Mill, some 4000–5000 workers were said to be under the HWA’s influence. This was perhaps the largest of all the workers’ organizations established by the anarchists.[72] The mill, founded in 1912 under joint management of officials and merchants, had been brought to a standstill by successive years of warlord conflicts, though its doors remained open. In the meantime the Hua Shi company, a Hunan capitalist concern, had colluded with the local warlord to acquire the management rights to the mill. Since the company’s policy of importing capital and technology from other provinces had aroused the common resentment of Hunan’s industrial, commercial and educational circles, the HWA achieved great popularity when, in April 1921, it began an all-out struggle to restore the mill to the Hunanese.