Noche

But We Have To So We Do It Real Slow…

On Anti-work, Mexican(-American)s and Work (Revised)

Introduction

I wrote this short essay 5 years ago at a time when anti-work was not as popular a position, or sentiment, within the radical milieu. My intention with this piece was to highlights elements of anti-work / refusal of labor that already exist among Mexican(-American)s in the so-called United States. And by doing this extend the critique of work beyond the white radical milieu of the North American Anglosphere. The critique of work is now (thankfully) more widespread, and I hope that others take up the task of extending the critique of work because the pandemic has verily cleared the fog of pro-work propaganda: most of us learned first-hand that our work, deemed essential or not, has always been activity which exists for the immediate benefit of others and not ourselves. We barely float by, physically & mentally, while capitalists retreat further into their well-protected bubbles of wealth (even into space). It’s time we reclaim our time, energy & activity. Time for communism & anarchy…which always also means the abolition of work.

Noche

Tovaangar, so-called Los Angeles

July, 2021

In Los Angeles to be against the racial regime of Capital typically presents itself in a pro-work / worker position. The problem is never work itself, the nature of work or that work is waged; instead, what is desired is extending the sphere of unionized work bolstered with higher wages. Take for instance the CLEAN Carwash campaign, where carwash workers (whom are mostly immigrant men) have been unionized under the representation of United Steelworkers Local 675. Though this move about much-needed improvements of the working conditions and wages for these workers, what is ultimately not brought up is that the work of car wash workers can and has already been automated. But the fading labor movement seems to be no longer concerned with the overthrow of capitalism, let alone the abolition of work. As Capital offers up less & less in concessions to workers, these radical dream appear to be lost long, along within the labor movement.

The expression of an anti-work position has either been minoritarian or unheard of. In a city where working conditions for immigrants can be well below the legal standards set forth by the State and the Federal Government, the push for more protections and rights within the workplace understandably takes precedence. An anti-work affect (rather than a bonafide position) among Mexican immigrants and / or Mexican-Americans is usually to be found in cultural forms and often do not take on explicit anti-political or anti-capitalist forms. That said, the playful, tongue-in-cheek cultural forms are plentiful, the other set of forms are few and far in between.

Anti-Work / Anti-Capitalist: An Introduction

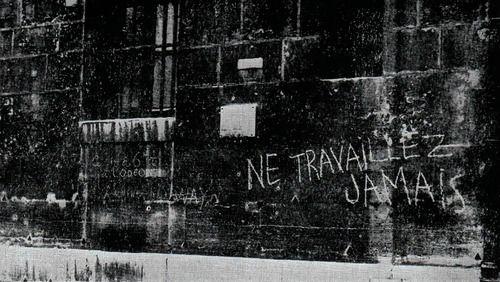

My first encounter with an explicit anti-work position came from fellow Chican@ friends who I had met in 2001. They were heavily-influenced by the French communist theorist Guy Debord and the Situationist International. In 1953, a young Guy Debord painted on a Parisian wall, on the Rue de Seine « NE TRAVAILLEZ JAMAIS » (tr. Never Work). A statement that was difficult for me to understand conceptually at the time but which I immediately gravitated towards (who as a youth looks forward to a lifetime of work ahead of them?). Previously, all the anarchist literature I had read on work concerned themselves with how wage labor was theft of our time, our labor-power, our created wealth and that the solution was not the abolition of work per se but worker self-management.

Anti-work was a scandalous position growing up in a Mexican household where what was prized was the opportunity to find well-paying work, as well as a hearty work ethic. Though the starting point for Guy Debord’s opposition to a world of work was not a beatnik, bohemian-lifestyle refusal common to the 1950s, rather it was a rejection of the bleariness of life under capitalism and part of a whole project to overthrow the capitalist totality he coined as the Spectacle. The aim was not just to make life bearable, but also to return joy into our daily lives.

The critique of work can be found elsewhere throughout history including Paul Lafargue’s “The Right to be Lazy”(1883) written by Karl Marx’s son-in-law or in Gilles Dauve’s “Eclipse & Re-Emergence of the Communist Movement” (1970) where Dauvé clarifies what the abolition of work means: “what we want is the abolition of work as an activity separate from the rest of life.” He further explains that the issue at hand is not whether we are active or not, but rather that under capitalism what we do is abstracted into two spheres, both alienated: work-time and leisure-time. This (anti-state) communist critique of work highlights that the liberation from Capital is not the liberation of labor but the liberation from labor. Currently it is broadly assumed that only those activities which are paid a wage have some social worth and that only those things which are productive, in the capitalist sense, are necessary to human life.

Mexican-Americans & Work

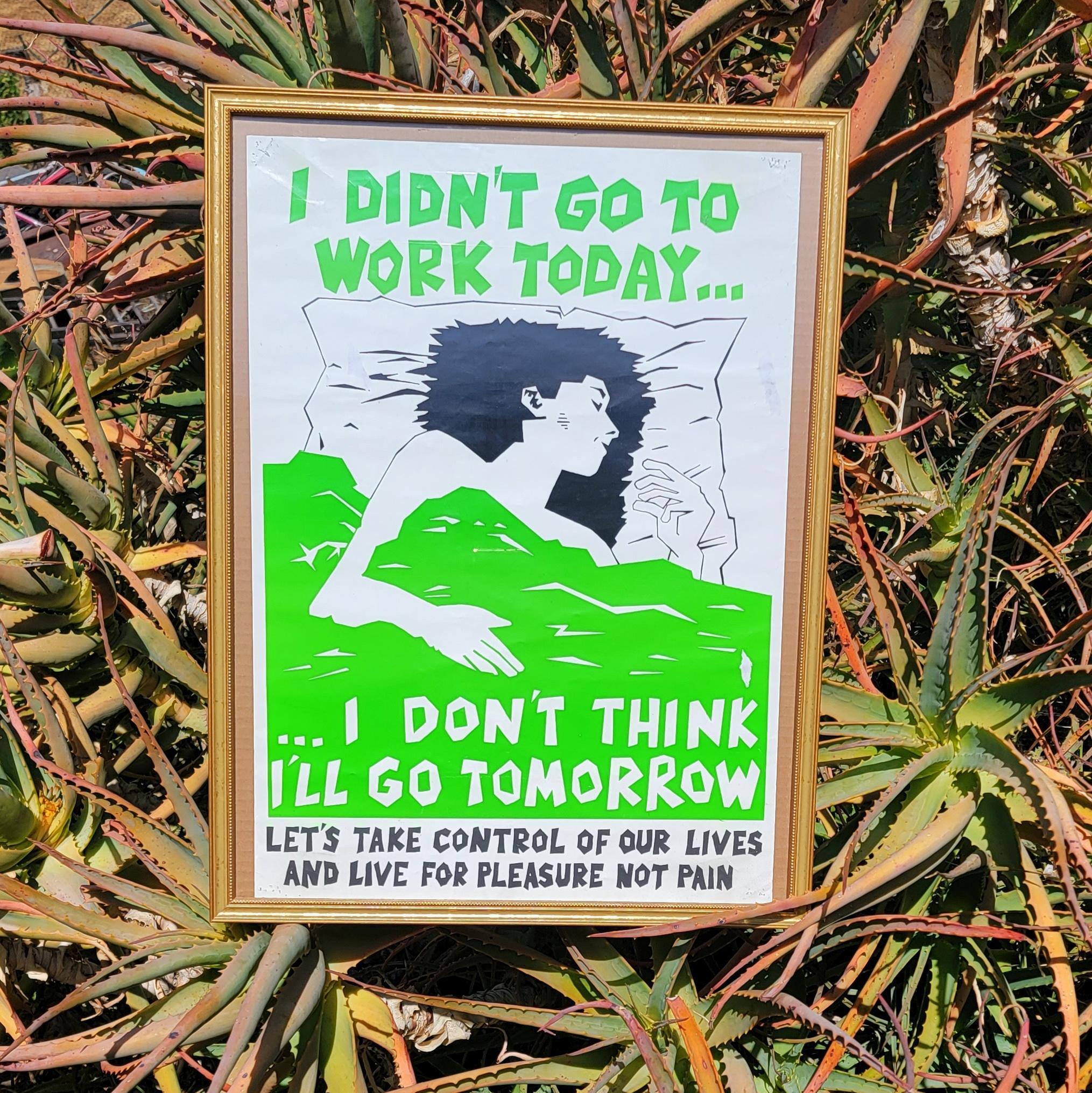

That said there is no shortage of cultural output from Mexican immigrants, or Mexican-Americans (some of whom identify as Chicanx) that takes a swipe at the way work is made necessary to our social reproduction. Take for instance a comedic song from “Up In Smoke” (1978), where the main protagonist, Pedro de Pacas, sings a song trying to upend notions of popular Mexican-American identity and says, “Mexican-Americans don’t like to get up early in the morning but they have to so they do it real slow.”

CHEECH AND CHONG — MEXICAN AMERICANS HQ

Here we catch a key moment in the subjectivity of the racialized Mexican-American worker caught up in a world where labor is understood as a necessary evil, but an evil all the same. There is an implicit understanding that work and the preparation for work is itself drudgery, but also that the refusal of labor is always present; this refusal is acknowledged and gives way to a sabotage on social reproductivity, an at home slow-down.

The spectacular production of the Mexican as a worker in the USA (or as a Mexican-American) is often tied up in a binary of either being hard-working & job-stealing; or lazy and welfare-scheming. As seen by the words used by Donald Trump during his presidential campaign and throughout his presidency, there is also the perception of the Mexican as a dangerous criminal, forming a trinity of prejudice that returns when it suits the need of nativist, racist politicians. This type of characterization was first seen when the U.S. forcefully annexed the so-called American SouthWest from México and bandits like Tiburcio Vasquez haunted the minds of the waves of Westward-bound Anglo-Americans. In 1954, this showed up as Operation Wetback where the INS (which later becomes ICE) enacted indiscriminate round-ups of Mexican laborers to put a chilling effect on undocumented migration of laborers into the USA. Laborers needed only to “look Mexican” to be deported and many of those deported were in fact U.S. citizens.

To posit an anti-work position and consider the racialization of workers in the USA may loom as an impossible task. Often immigrants internalize a work ethic that can be as entrenched as that of right-wing Anglo-Americans, who erroneously describe the USA as a meritocracy. This is more necessity than reaction by Mexican immigrants under racialized capitalism since they are often forced into the most grueling of work reserved for non-citizens without legal recourse or for the incarcerated: picking of fruits & vegetables, construction, food service, childcare, landscaping, etc. We work hard because we are compelled to and create a self-serving mythology around it. A mythology where we are the hard-working ones and everyone else is the not-harding-working ones. This is notably where the international aspect of anti-Blackness comes to the fore. Nonblack Mexicans often harbor anti-Black positions that claim that Black people in the United States are not as industrious as they are and thus dismiss the realities of antiBlackness as courting victimization. On the other hand, European-Americans are seen as exemplary and should be our role models because of their capacity for money management and investment.

To further the myth of the hard-working immigrant, that does not threaten the colonial-capitalist social order of the USA, is to strip immigrants of the agency to express refusal, resistance and revolt. In a time where nativist racism is once again peaking, we must realize that the proliferation of this myth is no safety net against ICE sweeps or other racist violence. There is no pride in presenting ourselves as hard-working, since under capitalism working hard merely means we are putting in more labor for the same amount of pay. In effect, we are lowering our wages by putting in more work than is expected and making ourselves hyper-exploited. If we were to collectively express our reluctance or refusal to work beyond the bare minimum, we could begin to flex the capacity of our labor-power across industries. (An inspiring moment of this kind of flexing was the general strike on May 1st, 2006 where immigrants largely self-organized a strike to show how much their labor is integral to the functioning of U.S. capitalism; in Los Angeles 1 to 2 million people took to the streets & over 90% of LA Port traffic was shut down.)

A Way Out?

But this desire to be the most hardworking Mexican in the world wasn’t always the norm. Labor discipline, as experienced under the racial regime of Capital, is a Euro-import. In British historian E.P. Thompson’s 1967 text “Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism” he mentioned how economic-growth theorists viewed Mexican mineworkers as “indolent and childlike people” because they lacked labor discipline. For instance, he notes from a book on the The Mexican Mining Industry, 1890 – 1950 that Mexican mineworkers had:

“[a] lack of initiative, [an] inability to save, absences while celebrating too many holidays, [a] willingness to work for only three or four days a week if that paid for necessities, [and] an insatiable desire for alcohol…” (Bernstein)

It seems that time changes little. Of course, in many ways we always knew that we don’t really want to go to work and that we only have disdain for those who don’t have to because we are not them. That we enjoy the winter break where we fill up on tamales, cervezas and spend the evenings talking about what we’d really like to be doing and dreams for the future. Even the Left’s obsession with the mythologized collective worker that is socially responsible, punctual and who identifies with their work is largely a fabrication of the largely dead worker’s movement.

The communist theory journal, Endnotes, notes that:

“the supposed identity that the worker’s movement constructed turned out to be a particular one. It subsumed workers only insofar as they were stamped, or were willing to be stamped, with a very particular character. It included workers not as they were in themselves, but only to the extent that they conformed to a certain image of respectability, dignity, hard work, family, organisation, sobriety, atheism, and so on.”

Too often we are given the lie that the way forward is to submit to the rationalization of the capitalist system; that we simply need to awaken the sleeping giant which represents the possible Latinx voting bloc; that the rich are rich because they really know how to handle their money; that if only we could sway Congress to push immigration reform; if only we could get universities to tell us back our histories or to enroll us at all…but really the way out is to abolish the set of social relations that reproduce the racial regime of Capital…which is protected by the State; which then protects itself with borders, police, oppressive vigilante violence and a standing army; that controls the way we envision our lives with careers, time management and rigid gender & sexuality roles; that makes a commodity of what we choose to spend our not-working hours on, which yet are still spent preparing or recovering from those working hours.

¿Pero Cómo Resisteremos Por Mientras? / How Can We Resist Right Now? (Or we’ve been resisting this whole time)

Thinking back to the 90s, the ditch party was both an escape from the terrible Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), as well as a form of resistance to the most alienating of compulsory schooling: in many ways these teens that would not show up to school and instead partied during school hours contained much more awareness of the society they live in than the kids that would instead get ‘straight As’ and then study Chicano/a Studies. These kids implicitly understood the pipeline that the LAUSD embodided to low-paying, entry-level service work where they would have to do much more rule-following, guideline-abiding, button-pushing, uniform-wearing than critical thinking. It was as though they were able to envision the no future we currently find ourselves in.

So many of us already partake in what are often public secret(s) of resistance to work:

-

we slack off at work, which in Marxian terms could be seen as a way of raising your own wage since you are putting in less labor for the same length of time.

-

we steal from work and thus make our time at our workplace much more worthwhile, and even get some nice gifts for friends and family.

-

we sabotage the flow of productivity by working slowly, or by shutting down the internet, or by talking to our coworkers about not-work-related things, or by not working at all and taking a nice siesta.

-

we call in sick when we’re really not sick at all or really we’re just too hungover from the rager the night before.

A world without work seems like an impossibility, a utopia, an unlikely dream especially when most of our waking time is spent thinking about how we’re going to pay the rent, the power bill, car insurance, student loans, credit card debt or the bar tab…but a world without work is also a world without capitalism… a world of communism & anarchy.

That world is a world without wage labor, without patriarchy, without race, without class, without a state, without police; where we would decide our lives on our own terms without the limitations of value production, without the control of borders, without Monday mornings, without social death, without artificial crises, where we won’t have to suffer the indignities of being harassed by the boss, a world beyond accounting, a world where what we do will not define who we are to each other. For a world without measure!

c/s