MB Sundjata

How and Why the US Left Betrayed Tigray

US organizations like PSL and Black Alliance for Peace cannot be trusted to advocate for Palestine’s liberation after they condemned nearly a million Tigrayans to genocide.

I thought further and said: “Why do men lie over problems of such great importance, even to the point of destroying themselves?” and they seemed to do so because although they pretend to know all, they know nothing. Convinced they know all, they do not attempt to investigate the truth. — Zara Yacob of Aksum (Tigray), 17th-century philosopher, in The Hatata Inquiries

(Content Warning: this article describes acts of genocide and wartime atrocities, including mass murders, concentration camps, land theft, deliberate starvation, and militarized sexual assault.)

I.

From November 3rd, 2020 to November 3, 2022, the Ethiopian Federal State waged a genocidal war on the kilil (regional state) of Tigray. Its pretext was a prior assault on the Northern Command base of the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) in Mekelle, perpetrated by the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the leading party in the country’s former ruling coalition, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF).

What was sold to the international community was a rapid pacification campaign, lasting no more than a few weeks, undertaken to defend Ethiopia’s unity from secessionists. Weeks became months, months grew to years. Backed on the ground by Eritrea’s EDF, by Amhara Special Forces and (civilian) Fano militias, and (surreptitiously) by Somalian troops; employing bombers, drones, and other materiel sold by Turkey, Israel, the UAE, and Iran, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed protracted his “counter-terrorist campaign” into a wide-scale cleansing of the Tegaru people.

At breakneck speed, the cities and towns of Tigray, historical center of the Aksumite empire, were heavily shelled, toppling ancient relics alongside young bodies. In the span of one month, hundreds of civilians each died in massacres at Humera, Adigrat, and Aksum. The invaders mass-detained civilians in makeshift internment camps, where they allowed the sick and starved to die, and directly killed others. They looted private property and national artifacts, seized homes, cleared Tegarus by hundreds of thousands from centuries-old neighborhoods in Western and Southern Tigray. An estimated 1.6 million Tigrayans have been displaced from their homes due to operations across the region.

With the moral sanction of handpicked Orthodox clergy, Ethiopia and Eritrea’s ground forces unleashed hell on the old Christian capital. They weaponized rape, especially of adolescent girls, to terrifying effect, and destroyed hospitals and clinics that could provide local care for their victims. Activists warn that the government severely downplays the resulting spike of HIV cases, a problem that will affect Tigray for generations. Famine, an endemic fear in the northern country, was ensured by military crop destruction, and like Mengistu before him, Abiy was keen to prevent humanitarian aid from entering the region. Thousands died from starvation, and even today some 3.5 million Tigrayans are in need of year-long food aid. Telecommunications were shut down, and the government barred entry to foreign press agents, leaving Abiy and accomplices to shape the narrative to their liking.

State and private media clamored for something like a final solution to the TPLF “sickness” — code for Tegaru, and some didn’t bother with any code. State officials, like Abiy’s Social Affairs Adviser, Daniel Kibret, a very religious man, said the quiet part out loud in Amharic: “Woyaneness” (TPLF affiliation) is a physical disease of the Tigrayans, that needs to be wiped out by physical means. His analogy was to the extermination of the indigenous Tasmanians.

Abiy, a Peace Prize-winning, neoliberal warlord after Obama’s pattern, saw his reputation drop with Western institutions that formerly backed him. He was supposed to undo remnants of the ‘developmental state’ model from the TPLF years; create a more friendly climate for foreign investment; and pivot Ethiopia back toward the World Bank, after Meles had moved it nearer to China and India. They apparently didn’t notice, more likely didn’t care, that Abiy rose from the same school of violent repression (EPRDF) they had always ignored, for the sake of their intelligence and financial ties with Meles’s regime. When Abiy stepped over the thick red line for acceptable atrocities in Black countries, the West finally felt compelled to ‘act’. Some threatened sanctions, but this was only performance. However, a UN International Commission of Human Rights Experts in Ethiopia (ICHREE) was assembled in late 2021, and found strong evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Among other recommendations, they called for an extension of their mandate, to gather further evidence of genocide. Abiy simply refused them entry to Tigray. Suspiciously, the UN Human Rights Council dropped the entire matter, despite the earlier hand-wringing by NATO allies, who control that body.

“Recent years have seen some of the darkest chapters in Ethiopia’s history. We cannot overstate the scale and gravity of atrocities committed by all parties to the conflict,” said Mohamed Chande Othman, Chairperson of the Commission. “We found evidence of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed on a staggering scale. In the region of Tigray, we believe that further investigation is needed to determine the possible commission of the crime against humanity of extermination and the crime of genocide.”

The Commission’s mandate was not renewed at the 54th session of the UN Human Rights Council earlier this month.

“The decision to discontinue the work of the Commission takes place against a backdrop of serious violations against civilians in the country, as our recent reports have shown,” said Commissioner Steven Ratner.

[Quoted]: statement by the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia, expressing their concern over the HRC’s decision not to extend their investigation for further evidence of genocide in Tigray Region.

The signing of the Pretoria Agreement, in late 2022, brought this hateful bacchanal to an unsteady halt. In the aftermath, between 600 and 800,000 Tigrayan lives were lost, out of an estimated population of 7 million. Close to 2 million were displaced from their homes, with many seeking refuge in neighboring Sudan, another flashpoint of racial violence. Recent efforts to re-settle native IDPs in Southern Tigray, in compliance with the Pretoria plan, are once more stirring the cauldron of fascism, especially with irredentist supporters of Fano. Despite the formal cessation of hostilities — there is no room to really speak of ‘peace’ here — activists at home and abroad warn that a fresh round of atrocities waits at the next corner.

The Tigray War, the most devastating war begun in this century, set the tone for Abiy’s fledgling dictatorship, which is quickly extending Tigray’s nightmare to all of Ethiopia. Ordering Fano to disarm after Pretoria, Abiy was met with surprising resistance from the Amhara region. His tried-and-true response has been to bomb, arrest, intern, and otherwise harass innocent Amharas across the country. Their elite representatives, in an ironic turn, have now charged the regime with Amhara genocide. His own Oromo people — ruled by his Chief of Staff, and Oromia regional president, Shimelis Abdisa — have proved an unreliable base in his bid for absolute power. Shimelis, and other regional Prosperity Party (PP) officials, have reportedly organized a secret police committee, the Koree Nageenya, to arrest, torture, kill, or intimidate thousands of dissenting Oromos, who are accused of sympathies with the rebel Oromo Liberation Army (OLA). Most recently, the committee has been blamed for the assassination of Battee Urgessaa, a political officer of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), the major ‘legal’ opposition in the region, whose leaders are largely imprisoned.

For now, Ethiopia’s unity is indeed secured, but as it usually has been, by systematic State terror.

For anti-imperial observers, analogies between Tigray and Palestine are, or should be, unavoidable. Using “anti-terrorism” as a legal shield, Ethiopia launched a full-scale war on a civilian population, one replete with state-sponsored hate speech, summary abrogation of human rights, massive land theft, historical and cultural erasure, and, most important, the erasure of hundreds of thousands of innocent lives. Fueled by extreme race hatred, formed over centuries of Habesha power politics; and desperate to prove their grip on Ethiopia, a vital geostrategic asset for the West, the ruling party antagonized Tigray at each point leading to November 3. Then they used a desperate TPLF countermeasure as their casus belli to “dry up the sea” of the Tigray people, pledging to resettle the landscape with loyal Ethiopians. The parallels with Israel’s scapegoating of Hamas, and with its demagogic appeals to Israeli settlers, are uncanny. Also familiar are the prevarications of Ethiopia’s diplomatic class: their rollout of neat rhetorical binaries that divided “terrorists” from “democrats,” whenever the global community raised alarms over the war.

The clearest discontinuities in the genocides, meanwhile, concern the racial/geographic positions and death tolls of the impacted populations. Tigrayans, an Ethio-Semitic ethnic group, anciently related to indigenous African and Southern Arabian populations, are inscribed as Black by Western codes of racialization. So they are subsumed with the general mass of Black victims of genocides, from Sudan to the Democratic Republic of Congo, and pushed into very remote corners of Western policy talk and public awareness. Africa, the most exploited continent, cannot be so thoroughly robbed by finance capital without the prior, widespread devaluation of its inhabitants’ lives. When we hear, then, that an estimated 10% of Tigray’s total population has died in this war — compared to 1.7% of Gazans since October 2023 — we shouldn’t wonder at the disproportion in global outcry, even as we stand with Palestine against all settlerism. Antiblackness is the axis of racial capitalism on the world stage. Among the colonized, who die deaths by similar means, according to the same beastly illogic, the system still sifts for the right shade of victims.

But has the Western left taken up the cause of Tigray with equal vigor as Palestine’s liberation? US-based organizations like Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL), and its anti-war front group, the ANSWER Coalition; the Workers World Party (WWP), from which PSL originally split; and Black Alliance for Peace (BAP), a self-proclaimed “inheritor of the Black Radical Tradition,” all claim to be foremost allies in Africa’s struggle against capitalism, imperialism, and racism. Surely they would recognize the urgency of Tigray’s crisis better than the Western press, diplomatic corps, and NATO-aligned human rights groups. Surely this grave nexus of international financial interest, military occupation, inter-imperialist collusion, and global apathy toward Black death, demands their attention, like no other US political bloc.

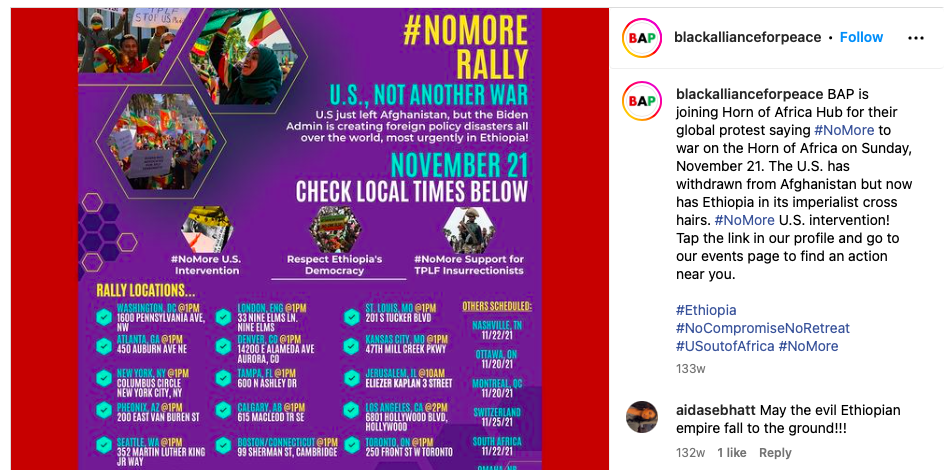

During the war, in fact, these groups covered up the genocide, parroted Abiy’s talking points. Under the guise of US non-interventionism, at protests of State Department sanctions, they played surrogates for Ethiopia at a time of mass bloodletting. Leaders spoke of the pro-American designs of TPLF “terrorists,” at panels convened by the #NoMore campaign, led by Hermela Aregawi. (Aregawi is an Ethiopian-American journalist and fitful “anti-imperialist,” who went on, after the war, to become a US Congressional employee.) In outlets like BreakThrough News, Liberation News, and Black Agenda Report, they cheered for Abiy and Isaias’ victory over “TPLF” (Tigray); ignored or downplayed civilian death tolls; implied that genocide claims were concocted by the CIA/State Department; trotted out romantic, often contradictory tropes of Ethiopia’s anti-imperial history, and that of its Eritrean partner, while ignoring their own fraught history together.

Since the war’s “end,” and with its recent security challenges, these groups seem to have dropped all collective mention of Ethiopia. Maybe they did so out of embarrassment at its waxing political crisis; or at the re-normalization of US-Ethiopia relations, accompanied by much brown-nosing of Mike Hammer; or at Abiy’s saber-rattling toward Eritrea and Somalia — his former crime partners — for Red Sea access. Their expectation was apparently that TPLF’s demise would help stabilize and further unify the region under IGAD, preferably with a ‘Marxist’ leader, like Isaias Afwerki, at its helm. If countless people died, that was worth it, for whatever ‘scientific’ reason the Central Committees could invent. Nobody seems to have guessed that a leader who enacts a genocide before the world wouldn’t become a lamb on the day after.

As we will see in the next section, these organizations were not simply misinformed about what was happening in Ethiopia. In truth, the war formed a strange constellation of interests between US Marxist-Leninist groups, with tendentious and very outrageous views on Ethiopia after Mengistu; statist Pan-Africanists in the US, well-rehearsed in militant scripts to acquit African heads of state for every criminal act; and regime supporters of Ethiopia and Eritrea, with their own cynical reasons to uphold nationalism’s checkered legacy in the Horn.

II.

In August 2012, Eugene Puryear, a Central Committee member of the PSL, published an opinion piece in the Party organ, Liberation News, where he explains the revolutionary importance of the Derg, and denounces the imperial aims of its opponents (”The Legacy of Meles Zenawi: Good for Imperialism, Bad for Ethiopia”). The occasion was the sudden passing of Meles Zenawi, Prime Minister of Ethiopia: architect of the interior strategy that deposed Mengistu, leader of the transition to multinational federalism. It is one of several articles on the Horn with Puryear’s byline. It can be safely assumed that he is a Party authority on the subject.

This document, in fact, exposes the ignorance and oracular pretensions of PSL’s leadership on African affairs. As an artifact of their broader view of Horn politics, it also helps explain why, a decade later, they looked away while nearly a million lives were sacrificed to a neoliberal tyrant’s plans. Then, as now, Puryear laid the blame on TPLF for Ethiopia’s sorrows since ’74. His many articles and broadcasts since then have only repeated the truisms found here, minus the Mengistu-worship; though Stalinist revisionism remains a suppressed premise through the rest of his reports on the region. We hear the same themes when he is shilling for the #NoMore movement years later, though he has since switched out idols for Isaias.

With no scholarly or journalistic citations backing him, Puryear tells us straightaway that the Derg — perpetrators of the Red Terror, which destroyed and exiled thousands of Ethiopian families, and of parallel wars to retain Eritrea and subdue Tigray — were a”pro-socialist government”. That Ethiopia’s potential as a launching-pad for Marxist revolutions was a mortal threat to Western interests in Africa. Furthermore, that since TPLF and other (unnamed) liberation movements challenged the nation’s integrity, hence the revolution itself, Mengistu’s apparatus was right to repress them. Western powers covertly funded these secessionist movements, he suggests, in a plot to destabilize Ethiopia and remove a powerful Soviet ally. Out of gratitude to his masters, once Meles seized power, his regime acted as a US military proxy in the Horn. It liberalized the national economy, with underdeveloping effects for the rural masses; and enlarged the bureaucracy to murder, imprison, and exile the Party’s political opponents. You get the sense that Meles’s surprise death is a welcome event, since it portends TPLF’s collapse, though it’s not clear what social force or political movement will replace it, or on what ideological basis.

Puryear’s account is not wrong in every detail. But it discards or distorts the key details that condemn Mengistu, if they don’t exonerate Meles. Above all it shows that Puryear, and the Party that published him, are cultists, who believe that a junta like the Provisional Military Administrative Council (PMAC) can really institute socialism from above, without a substantial worker base for its ‘workers’ dictatorship’ and even, until 1984, without a formal Party. That PSL expects senior cadres to embarrass themselves when talking about Ethiopia. It shows that they’re too susceptible to Marxist pageantry in distant countries, and don’t care to study the real social conditions and national conflicts beneath the red flags and Lenin portraits. Of course, it’s one thing to have a stereotyped and willfully ignorant view of history as a fringe sect, that will never seize state power. But to act on your bad ideas, to persuade others not to act and not even to listen during a genocide, is unforgivable, from a political and a purely human point of view.

The theoretical reasons for this failure have to be closely considered, since these same groups place themselves at the forefront of the US anti-war movement. According to Leninist theory, these vanguards are supposed to have clearer conceptions about world events than the spontaneous masses. When worlds are being destroyed, the oppressed can’t afford ‘solidarity’ from unserious people, who don’t take our histories seriously, and who base their practice on the most ridiculous ideas of history’s meaning.

Zenawi was born in 1955 in Adwa, the northern Ethiopian city where in 1895 Ethiopian soldiers soundly defeated land-hungry Italian colonizers. He was a college student in 1974 when a group of revolutionary officers in the Ethiopian army overthrew Haile Selassie and established the People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. The new regime, popularly known as the Derg, had a Marxist orientation and aligned itself with the Soviet Union and other socialist bloc countries. Caught up in the popular uprising that swept the emperor out of power, Zenawi became a leader of the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front, the Tigray being both a region and a people, one of the many that exist across Ethiopia.

The area today known as the Horn of Africa has at different times been under the hegemony of various Ethiopian kingdoms and empires. The Solomonic dynasty had ruled large parts of this area from 1270 until Selassie’s fall in 1974. As the Solomonic rulers came principally from the Amhara people, other peoples such as the Tigray, Eritreans and Oromo faced oppression. This was the impetus behind the creation of the TPLF—to assert the right of self-determination on behalf of the Tigray people.

National unity quickly became an important issue in the wake of the popular uprising that deposed the emperor. Organizations representing, or at least claiming to represent, various ethnic groups quickly made claims and counter-claims to large sections of Ethiopia. By contrast, the new revolutionary government emphasized national unity.

The Derg realized that self-determination did not exist in a vacuum, and in fact such claims were becoming a danger to the social revolution taking place in Ethiopia. Western imperialist powers were terrified of the new Derg government. They recognized that the Derg were not simply sloganeers but were determined to move forward with deep-going social change. Ethiopia was poised to become a center for the broader revolutionary movement in Africa.

In this short opening selection, we already find several basic misunderstandings of Ethiopian history — politically, socially, even chronologically, all held together by rhetorical tricks that fall apart quickly on inspection. It’s a part of the text that contains the whole error of his argument.

First, despite the impression we’re given above, the TPLF’s birth was not a sudden response to the events of 1974. Rather, it grew out of the activity of the Tigrean University Students’ Association, formed in 1971 (John Young, Peasant Revolution in Ethiopia, 83–85). The Association was the product of more than a decade of nationalist organizing by Tigray’s small, but politically combative, intellectual strata. It based itself on the spirit of the first Woyane (“rebellion”) of 1943: when Tigrayan peasants and landowners protested their diminished status under Selassie, and were bombed into silence, with British air support.

The armed movement’s growth was assisted by the Tigray National Organization (TNO), a Students’ Association offshoot, active in the early months of the Revolution. Like most Marxist groups, the TNO initially attempted to work with PMAC. But within months, the regime had showed its real face. By 1976, TPLF’s ranks swelled with Tigrayan students who were forced out of legal activism by PMAC’s spy apparatus, and its unaccountable violence toward civilians, as shown by the assassination of Tigrayan student activist, Meles Teckle (Gebru Tareke, The Ethiopian Revolution, 84–85; Young, 86).

Without Derg repression catalyzing their recruitment, the early TPLF cadres would have stayed a small and outgunned faction in the countryside, where they likely would be crushed by rival Marxist groups. You would think that “dialectical materialists” understood this, if they had bothered to peruse the record.

Next, by projecting the national question into a vague feudal past, Puryear hides the real causes of the Revolution, and of Tigrayan responses to it. He skips past the historic rivalry of Tigray and Amhara for the Abyssinian throne, which raged since before the Era of the Princes (Zemene Mesafint), and which had more recently yielded legendary figures like Yohannes IV, the last Tigrayan emperor; and Ras Alula Engida, the hero of Adwa and the Mahdist War.

That rivalry was only decided in Amhara’s favor in the late 19th century. Menelik’s ties to Europe gave him access to Western arms and military advisers, traded for commodities from the newly conquered ‘provinces’, like Oromia, Kaffa, and Hararghe (Harold Marcus, The Life and Times of Menelik II, 64–68, 73–75). Since Tigray was mired in dynastic wars in the North, while also fighting Italy’s occupation of Massawa, they soon fell behind Shewa militarily and diplomatically, as the Amhara-controlled Southern empire steadily grew with Western assistance.

In Menelik’s expanding State — already tied to the world capitalist market, and therefore not simply ‘feudal’ — a new system emerged, one departing from the political-economic, juridical, and cultural norms of the northern Habesha kingdoms. Neftegna (“gun-owners”) from the North, armed by the regime, occupied lands in the South, where they became the overseers of non-Habesha gabbars (serfs). Forced baptisms, of practitioners of Waaqeffannaa and other indigenous faiths, accompanied the imposition of Amharic, the sole official language of emerging colonial institutions.

From the Battle of Adwa, which proved the volatility of competing French and British imperialisms in the Horn; and definitely since the Tripartite Treaty of 1906, Ethiopia can be safely characterized, much like ‘Portuguese Africa,’ as a dependent colonial state: an empire having formal sovereignty, but that depends on senior foreign partners (who derive economic or strategic benefits) to maintain control of its colonies (Bonnie Holcomb and Sesai Ibssa, The Invention of Ethiopia, 108–13, 132–33). For sure, every Amhara did not profit from the new imperial arrangements. But those who did were fanatically invested in their racial hegemony, and insistent on the Amharanization of Ethiopia’s formal institutions and cultural life.

In this regime, elite Tigrayans, such as Ras Seyoum Mengesha, and elite Oromos, such as Ras Gobana Dache, sometimes held important roles in the state ministries and military. A small balabat class of native collaborators, paid with land and servants for loyalty to the State, also played a comprador function in the extraction of rural goods for Western markets. But the self-consciousness of the empire, of the ideal Ethiopian, was now solidly Amharan and Christian. As were the country’s economic and social relations; though these took a brutal altered form in the colonies, where they supplanted traditional relations by violence.

By the mid-20th century, these antagonisms had assumed a nationalistic form throughout the empire. Regime officials like Ras Seyoum were sometimes jeered at home, for their perceived political-cultural compromises with Amhara nobility: who had interpolated themselves into the Kebra Nagast as rightful heirs of the Solomonic line, at Aksum’s expense. Due to the neftegna legacy, furthermore, peasant uprisings in the South also often had dimensions of a racial struggle between Northern, Semitic landowners, and Cushitic or Nilotic serfs on their native land.

The 60’s student movement was therefore greatly exercised by the ‘national question’. Their cry, ‘Land to the Tiller!’, was inspired by peasant land expropriations that students observed directly, during mandatory teaching assignments in provincial villages (Holcomb and Ibssa, 320–21). The rise of armed liberation groups in Eritrea, Ogaden, Oromia, and Sidamo, only underlined the systemic crisis these youths would inherit, since they knew that such movements would have a strong support base among the peasant majority.

The coming Revolution was, in truth, a convergence of multiple factors: the fuel crisis in Addis, worker/student-teacher strikes, military grievances, popular outrage at Selassie’s response to the Wollo Famine. But of these factors, the anti-colonial struggles were the most indicative of the system’s impending collapse. These were revolts against local landowners or the central government. But because of the dependent colonial arrangement, they were also, implicitly, revolts against Western wealth extraction, and expressions of the inchoate nationalisms of its victims-by-proxy. In this respect, the Revolution was not simply a social one, but belongs to the story of national liberation movements that shook the Continent between the 1960s-80s. This fact tends to be obscured for Western observers by the apparent racial “sameness” of the various antagonists.

Meanwhile, Selassie was competing with more radical currents abroad to shape the course of African independence. He had negotiated to make Addis Ababa the headquarters of the OAU. He had intervened directly against Katanga secessionists in the Congo, and aided anti-apartheid struggles in Southern Rhodesia and South Africa (Robert Hess, Ethiopia: The Modernization of Autocracy, 211–12, 236). But he had also used his clout at the UN to engineer the Ogaden annexation; maneuvered to infiltrate and dissolve Eritrea’s National Assembly; and conspired with De Gaulle to keep Djibouti a small French dependency, instead of joining Greater Somalia (Hess, 121, 219–21, 226–28). His US security ties, which had sent Ethiopian troops to Korea in the 50s, made for a very visible Yankee presence in Addis Ababa, Debre Zeit, Dire Dawa, and other larger cities in the 60s — this, while the entire Third World was watching Vietnam. Selassie projected a continental role for Ethiopia: a kind of Pan-African capital, symbolized by Africa Hall. But the current agenda for the Continent was national liberation, and popular struggle with emergent neocolonial structures. These priorities clashed with the regime’s Western friendships, its contempt for neighbors’ sovereignty, and its stubborn defense of the existing borders of its admitted empire.

The contradictions must have been unbearable for Ethiopian students, required at once to be future leaders of a democratizing Africa, and future imperial technocrats, designing the fates of subordinate nations. Some students, fully inculcated with Ethiopianism, believed the “national question” was merely a bourgeois distraction from the class struggle that could unify the whole country. However, there were also important student leaders, like the Amhara revolutionary, Wallelign Mekonnen, who made good-faith attempts to reconcile Marxist-Leninist doctrine with the reality of national oppression in their country.

In his watershed article, “On the Question of Nationalities in Ethiopia” (1969), Wallelign bursts the sacrosanct myth of Ethiopia’s national unity:

What are the Ethiopian people composed of? I stress on the word peoples because sociologically speaking at this stage Ethiopia is not really one nation. It is made up of a dozen nationalities with their own languages, ways of dressing, history, social organization and territorial entity [...]. [I]n Ethiopia there is the Oromo Nation, the Tigrai Nation, the Amhara Nation, the Gurage Nation, the Sidama Nation, the Wellamo [Wolaytu] Nation, the Adere [Harari] Nation, and however you may not like it the Somali Nation.

He goes on to strip the veneer from the ostensibly “universal,” but really Amharic, national identity forced on the empire’s non-Habesha subjects:

To be a “genuine Ethiopian” one has to speak Amharic, to listen to Amharic music, to accept the Amhara-Tigre religion, Orthodox Christianity and to wear the Amhara-Tigre Shamma in international conferences. In some cases to be an “Ethiopian”, you will even have to change your name. In short to be an Ethiopian, you will have to wear an Amhara mask (to use Fanon’s expression). Start asserting your national identity and you are automatically a tribalist, that is if you are not blessed to be born an Amhara. According to the constitution you will need Amharic to go to school, to get a job, to read books (however few) and even to listen to the news on Radio “Ethiopia” [...].

Wallelign was no “secessionist.” His answer to national oppression was the founding of a “genuine national-state,” where there would be full recognition of the national characteristics and associated rights of federated peoples. Other theorists, like B.M. Redda, would include the right of secession, i.e., the right to dissolve any Ethiopian union predicated on force, in Wallelign’s formula (Ian Scott Horst, Like Ho Chi Minh! Like Che Guevara!, 43, 49). Tigrayan students were conscious of this general line, which they developed further, to include the demand that nationalities lead their own liberation struggles. This led to clashes with student factions that believed in multi-national organizations; these would eventually coalesce into the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP). Nonetheless, many Tigrayans embraced Wallelign’s thesis on Ethiopian empire, and felt that the oppression of non-Habesha lands was the economic and historic basis for their own condition in the North.

It is unsurprising that, with the fall of the Derg, “multi-national federalism” became the TPLF’s program for Ethiopian unity: in its essentials, it’s in agreement with the most advanced positions of the 60’s student movement.

Gliding past all this background, Puryear insinuates that TPLF arose, not from decades of Tigrayan struggle, or from a decade-plus of theorization, by Ethiopians, of their own country’s characteristics; but as a recent and erroneous byproduct of the ‘pro-socialist’ revolution of ’74, led by blameless army officials. This way, he can make a few idealistic students, naive enough to take Lenin serious about self-determination, into the sole efficient cause of a nationwide movement. Not the people themselves — the wrong-headed leadership.

And he insists that this leadership had very definite class commitments:

Practically, the TPLF was a nationalist peasant grouping with Maoist coloring. With Zenawi heading the leadership core, the TPLF found fertile ground in the rural areas for its cause, as significant numbers of more well-off peasants resisted Derg land-reform strategies, which aimed at expanding and appropriating agricultural surpluses to finance social services and industrial development. This discontent led the TPLF to fairly quickly become the dominant force in the Tigrayan countryside. Prioritizing the national struggle over social revolution made it easier to capitalize on peasant opposition to the Derg’s land collectivization policies and accompanying large-scale resettlements.

The TPLF quickly became the most effective anti-Derg armed force, and beginning in the late 1980s was able to play the key role in the united front of opposition groups that overthrew the Derg in 1991.

In this passage, Puryear again argues by pure assertion, this time with a bad analogy wrapped in Marxist cant. His framing of TPLF in the countryside is a simple copy-paste job of Stalin’s struggle with the kulak. He’s saying that TPLF’s social base was the rich, reactionary farmer, not the poor peasant masses. This is simply not true. Gebru Tareke, who is by no means a TPLF sympathizer, informs us that, while the peasantry’s support oscillated between the Derg and Woyane due to crimes committed by both, the vast majority of the population (not merely the “well-off peasants”) were unified under TPLF by the mid-80s (The Ethiopian Revolution, 90). This speaks at least as much to the rebels’ success at fostering a real sense of nationalist consciousness, and connecting that up with rural economic grievances, as to their capacity for repelling government forces.

But it is noteworthy that Puryear never raises the obvious question of the Derg’s social base. Was it the poor peasantry, the progressive nobility, the industrial workers, the small shopkeepers, the intelligentsia and petty-bourgeoisie, the urban capitalists — what was it? Ken Tarbuck, a Marxist philosopher who taught at Addis Ababa University in 1978, was genuinely confounded by the question, motivated by his personal experience of the paranoid and un-democratic environment of the capital under Mengistu’s rule (“Ethiopia and Socialist Theory”). Since the working class, he says, was already a negligible element in national life, and was suppressed in the early months of the Revolution; and the peasantry (he claims) was not a driving force either, he was at pains to clarify the regime’s class basis. He concludes that the State itself — or an apparatus of the State, the military — had become autonomous, and was running the machinery of surveillance and terror in its own interests.

The Derg’s social base was, indeed, within the military itself. The Imperial Army of Ethiopia (IAE) was organized as a modern defense force by Selassie from 1947; with the advisement and abundant financial aid, from 1951, of the United States (Hess, 118). The rank-and-file of this army was recruited from across the country, though Amharas and Oromos predominated. The staggered industrialization of Selassie’s Ethiopia meant that white-collar workers were nearly double the size of the proletariat, and both classes were drops in the ocean of the peasantry, which numbered nearly 23 million by 1970. The army, around 40,000 strong, was the readiest means to wage employment and upward mobility for many rural subjects, although there was an upper limit to promotion for most, and their pay and working conditions were often unsatisfactory (Tareke, 122).

Given Ethiopia’s expansionist character, though, there was little danger that recruits would run out of work. The IAE’s raison d’etre had been to increase the throne’s power relative to local rases; who historically defended Ethiopia’s ‘unity’ by activating regional troops, stationed at carefully placed ketemas (garrison towns), to quell colonial revolts (Holcomb and Ibssa, 110–11). To serve its intended function, the army had to prove its greater efficacy for taming rebellious provinces so as to ‘save’ Ethiopia: which it did, with blood-soaked campaigns in western Eritrea, Arussi, and the Ogaden. (It seems that during the Gojjam Rebellion, in Amhara country, the IAE could afford to be more circumspect about its use of violence.)

This is an openly imperial institution, built to strengthen the central authority against rival power centers in Abyssinia and the provinces; trained in US-funded (and staffed) military schools, and outfitted with US military equipment; and reared, like many elites-in-training during Selassie’s reign, with the view that there is only one government and one people of Ethiopia, which must be defended from secessionists by the harshest means. In fact, this was the sector that Western commentators most expected to take power after Selassie’s death, but without any concerns over its “Marxism” — unlike the students.

When the army did come to power, their parasitic relation to the peasant did not change from Selassie’s days, except by becoming more subtle. The Revolution’s vaunted land reforms, for which Mengistu receives the most credit, were in truth an opportunistic land-grab by the State. Contrary to the accounts of Tarbuck, Fred Halliday, and others, it was the peasant’s associations in Oromia that initiated the struggle with the “feudal” land-tenure system, by directly seizing their own produce from landlords.

The Derg, realizing the importance of first consolidating its grip on Addis, issued a pre-emptive land reform proclamation (March 4, 1975) that made all land the “collective holding” of Ethiopia. With promises to devolve control to the associations, the peasants’ land was converted overnight to State property, instead of reverting to the traditional owners. Then PMAC cadres began coopting the peasant’s organic movement, eventually (in 1978–79) absorbing their radical unions into the All-Ethiopia Peasant Association — curated by the regime and run by state-appointed officials, who immediately raised taxes and imposed conscription on the countryside (Holcomb and Ibssa, 347–48, 358–63). The Revolution was as much a counter-revolution, from the colonial Center against the agrarian Periphery.

By far, the Mengistu apologetics are the most embarrassing aspect of this document. Puryear blots out the Derg’s record of harshly repressing all opposition, not just from Marxist students, but also peasants and workers, which made armed struggle against it necessary. The junta’s crimes don’t start with the Red Terror — the anti-EPRP campaign that killed thousands in Addis and other urban centers — but begin on the very day they assumed power, in what was a dual coup: against the monarchy and the heterogeneous, but democratic and progressive, social forces poised to replace it. According to Babile Tola:

Between September 1974 and September 1976, there was no peace. A new war had started. The people did not raise arms during this time, they killed no official. Their main weapon was peaceful protest — demonstrations, petitions, protest resolutions, strikes and the like [...]. They were also calling on the military regime to live up to its words of going back to the barracks by handing over power to the people. The people protested peacefully, the Derg reacted violently. (To Kill a Generation, 29)

As Tola points out, the day the PMAC assumed power (Sept. 12, 1974), they issued a sweeping proclamation, giving them comprehensive powers over military and civilian affairs. Article 8 of the proclamation vaguely prohibits any opposition to the “philosophy” of Ethiopia First, and also banned strikes, and spontaneous demonstrations or public assemblies. The months that followed saw widespread arrests of labor and student leaders; an army shooting of a previously sanctioned gathering of unemployed workers (October 23); brutal repressions of Eritreans by Israeli-trained killing squads in Asmara; and a further proclamation (Nov. 16th) that made “impair[ing] the defensive power of the State” — which could mean about anything — into a capital offense. Thousands were arrested or killed before the EPRP took up arms (Tola, 29–32).

This repressive climate soon forced the largest Marxist party, the EPRP, out of the urban centers, where they had been slaughtered in the thousands, into the northern countryside, where they clashed with TPLF for control of Tigray’s awardjas (regional counties). Given Mengistu’s manipulation of MEISON (the All-Ethiopian Socialist Movement, a smaller Marxist formation) to crush EPRP’s militants, and his subsequent crackdown on MEISON as a weaker rival to power, the early decision (in 1975) of Tigrayan leaders like Ayele Gessesse, to oppose the regime with arms in their home country, proved to be a sound one. We have to ask what real chance there was for any serious Marxist movement to work in good faith with a junta that outlawed civil opposition on pain of death.

To be clear, the Derg did not begin with any ‘pro-socialist’ or Marxist tendency in the military ranks. Its early program, encompassed by the slogan “Ethiopia Tikdem” (“Ethiopia First”), was a gloss of anti-feudalism, modernizing nationalism, and demands by lower-ranking Army officers. Since the country’s small student class were the future State administrators, and since Marxist-Leninists dominated their activist wing, the PMAC did make cosmetic additions of Marxist rhetoric to their movement, hoping to ideologically outflank the student left. But Mengistu did not openly align with the Soviet Union until 1978; that is, only after Ethiopia had slaughtered a full crop of its future bureaucrats, alienating its former US allies. Soviet alignment then became necessary from the standpoint of security, since Mengistu planned to keep Selassie’s borders in place (Tareke, 117, 139).

The idea that in the mid-70s, the Derg was more evidently aligned with the socialist world, or trained in Marxist theory, than its student and worker opposition, is not supported by anything but the fact that they won power. As they were likely to do anyway, without any ideological motivations for the takeover. It overlooks the opportunist pattern of tyrants elsewhere in Africa, from Siad Barre to Jean-Bedel Bakossa, who courted the Soviet Union out of geopolitical exigency, not from any real Marxist conviction. It lets a genocidaire, who absconded from the crime scene with US help and with millions in stolen birr, morally off the hook, with a cheap appeal to History’s slaughter-bench. And it insults the many millions of Ethiopians whose memory of Mengistu is coated in blood.

There are other problems with Puryear’s analysis, both factual and logical. He falsely claims that the Ethiopian economy was stagnant during the EPRDF years, and more crushing for the peasant than it was, presumably, under the Derg government. (For credible scholarly appraisals of Ethiopia’s economic gains and limitations under Meles’s administration, see Gerard Prunier and Eloi Ficquet, eds., Understanding Contemporary Ethiopia.)

By telescoping the national question into a few glib sentences, he also misses the deep impact of Eritrean nationalism on the Ethiopian left, and of Eritrea’s tactical alliance with TPLF against Mengistu: factors that would stretch his argument to the breaking point. If he really believes the Derg’s program of ‘national unity’ was the correct Marxist line, then he is also implying that Eritrea, annexed as recently as 1962, should have remained part of the Ethiopian ‘nation’, as Mengistu himself clearly thought. That its independence struggle was wrong-headed, counter-revolutionary, and/or beneficial to US imperialism. Such a stance would be at cross-purposes with his latest propaganda, which pits Eritrea, as anti-colonial protagonist, against TPLF, the American stooge.

And then, he lays exaggerated stress on TPLF’s interventionism in Somalia, its bellicosity toward Eritrea, and its imperialist relationships, somehow overlooking that these belong to a general pattern of Ethiopian realpolitik, going back to the days of Wube and Menelik, and hardly interrupted by the Derg.

Overall, it is clear that Puryear and PSL have a weak grasp on the contours of ancient and modern Ethiopian history. His somewhat cartoonish account, full of Stalinist buzzwords and crude dialectics, more resembles Hegel’s “picture-thinking” than any determinate idea of its object.

But the vanguardist won’t let poor conceptions stop him from acting; even if, to do so, he has to abstract away from the misery of millions in his idealized State. And that is why he became a tool for the fanatically Protestant, pro-capitalist tyranny of PM Abiy, when a better historical sense would have counseled against it.

III.

Now that the damage in Tigray is ‘done’, PSL and its allies have stopped making official statements on Ethiopia. But it’s not because they’re embarrassed by genocidal regimes or by the genocide itself, which they have never acknowledged. Rather, they seem struck with buyer’s remorse for having backed one of the most dangerous leaders in recent African politics.

However, Puryear and his co-host at BreakThrough News, Rania Khalek, have lately attempted to make “sense” out of this denouement. Yet nothing in their earlier reporting gives them a foundation to do this in an intelligent and non-contradictory fashion.

First, a step back. During the war, BreakThrough News busily gathered any evidence they could find to support the regime’s narrative. They toured sites in Ethiopia that had been damaged by TDF forces, who were accused of atrocities against locals in Lalibela and Afar, while side-stepping the disproportionate destruction in Tigray. They spoke with government leaders, and with “opposition” leaders, to paint the picture that all of Ethiopia — regardless of differences among factions — was united in their disdain for TPLF.

In one video (”Who Speaks For Ethiopia?”, Jan. 19, 2022), the pair interviewed two members of the legal “opposition” to PP: Berhanu Nega of the Ezema Party, and Kejela Merdassa, spokesperson of OLF.

Aside from bemoaning the EPRDF’s undemocratic reign (which Abiy has since reprised, in slick new packaging), Berhanu claims that TPLF has used warnings of “genocide” to stymie the democratic process since 2005, suggesting we remain skeptical of charges of genocide today. He also accuses them of fostering ethnic-based politics, at the expense of an ideal of equality rooted in “citizenship of our country.”

Kejela meanwhile avers that the US, which tried to overthrow the Eritrean government in the 1990s, is behind the TPLF’s machinations; and further claims that TPLF began recruiting young, politically immature Oromos into OLA in 2019, thus accounting for that (illegitimate) group’s tactical unity with Woyane.

To call these men “opposition” figures is highly generous. As the video implies, but doesn’t explicate, both of them were members of the PM’s Cabinet of 22. Berhanu worked with Ethiopia’s Ministry of Education; while Kejela manned the all-important Ministry of Culture and Sports. These appointments were made, it appears, to divide and conquer the PP’s potential rivals in federal and Oromia regional elections.

In Kejela’s case, it is important to note that he belongs to the sellout faction of OLF that supports Abiy, even while much of the party’s leadership sits in prison or house arrest. In the early phase of the war, he was outspoken in his criticism of OLF Chairman, Dawud Ibsa, who has languished in house arrest since April 2021; where he has suffered routine home invasions by regional officers, and is denied interviews by the press. Dawud’s internment, which does not appear to have followed any due process, is the result of his party’s rejection of the government’s description of TPLF and OLA as terrorist organizations. It is consistent with the pattern of repression that has seen several high-ranking OLF leaders detained and tortured, and that also explains the murder of Battee Urgessaa in April 2024.

Kejela is clearly a collaborator against his countrymen and comrades, willing to trade in his principles for a ministerial post and a comfortable life, after years in exile.

Berhanu is a leader in a movement that has zero prospects of defeating PP in any federal or regional election. He owes his position completely to Abiy, not the viability of his party.

Given the growing accusations leveled at PSL for its own ties to US State officials, there are perhaps good reasons for their “journalists” to avoid the label “controlled opposition.” But that is precisely whom they were tapping for their cross-section of Ethiopian political stances on the war. This is not journalism, it’s stage management, for a maximum propaganda effect: ‘whatever their differences, Ethiopia is one in recognizing the mortal threat of Woyane’.

So when, after the war, this oneness divided to two, and these terms divided in their turn, our Horn experts returned to make sense of Ethiopia’s latest political crises (”Horn of Africa: Unity or Disintegration in 2024?”, Jan. 24).

“Ethiopia has not been in the news much since [the war ended],” Khalek says, in all seriousness, as if “the news” is limited to the American press and its “anti-war” critics. In the midst of wannabe technocratic rambling about Ethiopia’s possibilities in a multipolar world, Puryear tries to update his viewers on what has taken place there since his outlet has moved on. But his analysis is threadbare, to the point of being tautological.

The current conflicts in Ethiopia, he clarifies, are rooted in pre-existing ethnic tensions in the country — what an insight! His criticism of Abiy, if it can be called that, is that his party seems to want a stranglehold on political power, and will use drones and other deadly means to subdue his competitors by targeting their ethnic base.

Somehow, Puryear doesn’t make the connection between this strategy and the demonization and torture, for more than two years, of the Tigrayan people. Nor does he consider if a similar Machiavellianism was behind the isolating sanctions of TPLF and Tigray Region in the months leading up to the war. He does find time to crack a bad joke about his dislike for TPLF, when he approaches (without touching) the parallels between Tigray’s hell and the deteriorating security situation in Oromia and Amhara.

It seems no number of Ethiopian deaths is enough for him to admit that, perhaps, his analysis was wrong, that he made serious mistakes in buying and peddling the federal government’s narrative. Typically for Stalinists, he seems to think that criticism/self-criticism is an instrument for maintaining centralism in the Party, instead of a tool for arriving at truth by facing and transcending individual and collective errors. It looks like we can expect nothing like an admission of guilt from his party, or any formal apology to the hundreds of thousands who died while he interviewed regime puppets, thinking he was really doing something.

PSL is only the largest and most influential of the leftist culprits of the #NoMore debacle. Other participants might have dressed up the agenda with different rhetoric: maybe invoking the revolutionary importance of Meles’s Eritrean nemesis, Isaias, and his PFDJ, while forgetting Eritrea’s non-recognition of Palestine and its close diplomatic ties with Israel; or sounding alarms about TPLF’s relationship with AFRICOM, while conveniently omitting Abiy’s frequent and friendly strategy meetings with the same neocolonial military force.

But under their apparent differences of approach lay an identical motive, shared with the tyrants they served: to smash TPLF, even if it meant smashing the Tigrayan people with the same blow. Indifference toward, or ignorance of, Ethiopia’s imperial legacy and enduring character, led them to argue that what was needed to counter Western influence in the Horn was a change in personnel at the State’s helm.

This is neither a consistent Marxist-Leninist nor “Nkrumahist-Toureist” position. But it gave these groups an aura of African solidarity for their (relatively small) American audience; perhaps too, some hope of forging connections with the Ethiopian political class. Even this last prospect would only count for promoting their sects to prospective members, since these groups have neither the numbers nor the means to impact US policy, let alone lead a revolution here.

Yet their dirty work still has had the effect of lowering the awareness of some sections of the public to Tigray’s plight, even of prejudicing some people against the testimony of surviving victims. And it has tended to drain the hopes of Tigrayan activists, and of the countless victims of Isaias and Abiy in East Africa and its diasporas, that the “revolutionary Marxist” or “Pan-Africanist” movements in the US can be responsive to their cries.

Organizations that can’t stand in solidarity with all oppressed African people, even in the midst of their extermination, can’t be trusted in the fight against the genocide of non-Africans. Genocide is genocide; whether it’s blamed on the political class of its targeted group, whether it happens to an African or an Arab. Our constant war with the war machine can’t constantly slow down to remind the “vanguards” of this elemental truth.

For more information about the Tegaru Genocide, and guidance on supporting its victims and the Tigray liberation movement, please visit Omna Tigray, Make Injera Not War, and read/share the crucial analysis of Ethiopian politics by Horn Anarchists.