M

Anti-life

Dearest,

Introduction

Liberalism—a term which I abuse here to refer to a whole range of political discourses (progressive, radical, anarchist, etc.) related by their dependence on a common pool of “liberal” values (freedom, equality, life, dignity, etc.)—is fucked. I say this as someone who is “one of the good ones”, raised liberal and well-versed in all the right rhetorical commonplaces. “Liberalism” is fucked because it is hollow at its core, supported by a web of values that gain authority only from their constant circulation. It’s fucked up because it’s confused about its ethical foundation. If we are bold enough to ask why something like “freedom” is good, either (1) we get an answer that refers us to some other foundational value (freedom is good because oppression is bad, or because it’s a human right) or (2) the value is justified by an experience it is associated with (freedom is good because the experience of freedom is good, or because the experience of being unfree is bad). The first case is useless because it simply repeats the circulation of the same supposedly self-evident liberal values. The second case is much more interesting.

The reference to experience represents a possibility for the justification of liberal values by something more fundamental and more real. Unfortunately, liberalism generally fails to get specific about experience or rigorous about how experience relates to its core values. Instead, the “liberal” prefers to invoke experience in vague terms such as “suffering” simply in order to quickly return to the comfort of their abstract liberal values. I’m generalizing a lot here, and I’m pretty ignorant about the nuances of all the diverse strands of thought I’m calling “liberal”. But in my experience, this dependence on values abstracted away from experience seems to be overwhelmingly the case in liberal spaces. The pervasive acceptance of these values makes it hard to ever reach beyond the terms of the liberal discourse. But, in the interest of being able to think accurately about what should be done, we must reach beyond these terms.

What follows is my best sketch of what I think that should look like. I won’t pretend to prove anything, and I don’t even have a clear vision of what I would want to prove. But maybe I will convince you of some things, or at least start a conversation.

Value

My first claim is that experience is what makes it possible for anything to matter. By experience, I mean the fact that some things are not just physical structures reacting to and affecting their environment, but that they also, as a byproduct of their physical processes, produce experience. Certain bodies don’t just move, or think, but experience moving and thinking. The production of experience is inexplicable, just like the existence of anything is inexplicable, but it is our situation. If there were no experience, then nothing would matter.

But experience on its own is not enough to make things matter. It’s specifically the experience of what I will call “literal value” that allows anything to matter at all. Literal value refers to how experiences can somehow be good or bad. “Literal” is meant to emphasize the fact that this goodness or badness is directly experienced as good or bad, rather than being an unfelt evaluation of an experience. It makes sense how something called “value” can exist within a given value system (for example, it’s good to score points in basketball because it will get you closer to winning the game, which is the goal), but it’s impossible to understand literal value, which exists as value itself, not in reference to some more fundamental goal or value. Even given that experience exists and that it will have certain qualities (like how touch feels a certain way or how colors look the way they do), it’s perplexing that actual goodness and badness (not merely qualities, but value) can be experienced. Despite being unexplainable, literal value is experienced, and so—unfortunately—things matter.

I want to say more about what this experience of value is actually like—which is a frustratingly tricky thing to do. The descriptions of “good value” and “bad value” I give below reflect my struggle to pin down experiences that are by nature fleeting and difficult to put into words. The trickiness of examining experience means there’s still a lot I’m uncertain about. So I don’t want to theorize too much, especially since I’ve really only been thinking about my own experiences—experiences which are certainly different from those of other bodies, either in big or little ways. I want to leave room for my understanding to change. All that being said:

Bad Value

When we say that we “feel bad”, there are a number of mental states we might be in: we might be sad, depressed, grumpy, angry, guilty, in physical pain or discomfort, etc. In my understanding, while we might experience bad value (or not) within these states, being in these states is not itself a bad experience. Bad value is unlike any feeling in that it only ever occurs as an isolated moment. Bad value arises in certain contexts and is immediately dealt with via some positive reaction: a yelp, anger, crying, etc. In an especially bad experience, bad value might spring up again and again, but in between these moments, we cope with it and experience either no value or good value. It can be hard to tell what was really bad value after you’ve experienced it, but here are some of the contexts in which I think I’ve experienced bad value:

I did some pretty careless jaywalking and almost got hit by a car. Someone honked at me. It took a few seconds to sink in and then I felt bad value. I reacted by trying to blame it on the driver. That wasn’t very convincing and a vision of what happened recoalesced, and I got bad value again. I tried to just laugh at the whole situation, but this didn’t really work either. I kept thinking about it, but it’s unclear if I kept getting bad value each time the thought reappeared.

I was lying in bed in L’s apartment. I had been feeling generally annoyed at L, and they came over to me to ask me something. They had some hard candy or something in their mouth, and as they talked, it clinked around against their teeth, which I found really disgusting in a hateful way. I was feeling intense hatred towards L, but at the same time I was straining against my hatefulness and disgust because I felt guilty about always being annoyed at L for no reason. So instead of me just going all in on being grumpy and annoyed, my conflicting feelings culminated in a moment of really just wanting the interaction to end, and I got bad value.

I was in the airport waiting for my flight when I learned that A, who I was supposed to be visiting, tested positive for covid. I got all sad and crestfallen about it, but I didn’t get any bad value at first. Part of me was denying what was happening and the other part of me was enjoying being dramatic about it and moping around the airport. But, in the moment(s) when it clicked that my trip was basically ruined and I was gonna have to get on a shitty plane to go to shitty New York for no reason and spend the whole week with L, I did get bad value. And then I immediately converted the image of my situation back into fuel for an enjoyable hopelessness.

The A/C in L’s apartment was exceptionally loud, and it had the most terrifying wind up. It was early in the morning and I was half awake in bed, and the sound of the A/C starting up gave me a feeling of vulnerability and confusion as if I sensed I was about to die. There was bad value there. I think I continued to get bad value whenever it was quiet in the apartment and the A/C turned on.

I was sewing and I pricked my finger kinda hard. There was bad value, and then I said “Ow, fuck” under my breath and started heating up a little. I got over it quickly. There was a moment a few minutes later when my finger touched the dull end of the needle and I thought I was pricking it again. This gave me bad value.

These accounts are all based on notes I’ve taken on bad experiences immediately after the fact. Even still, it’s hard to know how much to trust them. Bad value occurs and is instantly lost to the past, and all I can do is rush to copy down the fading impressions left by the experience. My record of these impressions is distorted by the concepts I use to understand and express them. Maybe I’m deeply invested in an incorrect framework, and so I shape my memories of experiences in order to make them fit my model. I’m trying to delay theorization in order to remain open to the experience, but there are some things I do feel confident about.

For one, bad value as I understand it is not at all equivalent to “pain”. In the case of physical pain, “pain” describes the quality of a class of physical sensations. We might enjoy pain, or get mad at it, or not be bothered by it. In some cases, like when I pricked my finger, a painful sensation is a part of the circumstances that give rise to bad value, but it would be wrong to say that pain itself is bad. I sense that the term “mental pain” is more likely to be used to describe the experience of bad value itself, but it’s hard to know.

Secondly, certain mental states that we might call “feeling bad”—like sadness, depression, anger, feeling discomfort/pain, etc.—can actually be enjoyed and at least are not bad themselves in that they are not the continual experience of bad value. (“Enjoyed” is perhaps an awkward word to use here because I don’t mean that these states produce the feeling of “joy”, but that it can feel good or comforting to dig into and wallow in them.) Bad value certainly can occur within these states, like when you’re feeling sad and then a vision of the horribleness of the thing you’re sad about coalesces. Some bodies might even experience a depression, for example, that feels dominated by bad value, but in between the moments of bad value, the mental state itself is not bad. But maybe your experience is very different from mine.

Good Value

I haven’t thought that much about good value because, as I will argue later, it’s much less important than bad value. My rough understanding of good value is that it’s pretty similar to what we call “pleasure”. The only things I want to point out are that (as I’ve said above) we can find good value in the “enjoyment” of what we might call “feeling bad”; and that good value can occur in close proximity to bad value, often as result of how we react to the bad value. In other words, it would be wrong to associate good value purely with bright and cheery, happy feelings.

Ethics

Perhaps my usage of the word “value” is strange. Maybe “good value” seems redundant and “bad value” contradictory. At least according to Wikipedia, “value” typically only refers to something that is good, whereas “disvalue” is used to refer to bad things. But I like my misuse of “value” because unlike “value/disvalue”, it doesn’t imply that good and bad value are opposites. Instead, good and bad value are two distinct types of the same thing: value, where “value” simply refers to the way in which a thing matters. “Disvalue” suggests that bad value is the negative of good value, and that the two might cancel out when added together, but in reality, the two don’t interact at all. If you have a bad experience and then a good experience, you’ve just had two experiences, and neither one is able to erase the other. Similarly, there is no spectrum of value that ranges from good to bad. When you have an experience, it will either be of good value, bad value, or no value (or some other distinct kind of value that I haven’t experienced or haven’t had the insight to identify).

In fact, it’s not just that bad value is distinct and isolated from good value, but that each instance of bad (or good) value is isolated from every other instance of bad (or good) value. When bad value is experienced, the actual bad value of the experience is immediately lost to time. We might be able to conjure up memories of past bad experiences (or imagine future bad experiences), but the process of remembering (or imagining) is itself a new experience in the present, and if it comes with bad value, it’s not that memory (or imagination) can access past (or future) instances of bad value, but that a new instance of bad value is produced in the present. Experiences of value are separated by time, but also by space. By “space”, I mean the space of experiencers: when you experience a moment of bad value, I might empathize with you, but whatever I experience is entirely separate from what you experience. Instances of value are localized to a point in time and to an individual experiencer.

The consequence of this localization is that experiences of value do not naturally add up over time or across experiencers. We might get the sense that value can accumulate: repeated bad experiences might give us the impression that we had a particularly “bad day”, and many experiencers getting bad value at the same time might be called a “bad event” in history. But in reality, all these instances of bad value are always experienced separately, and the most we can ever experience is one individual instance of bad value. It might feel like this view of value makes bad value insignificant by saying that things can never really be that bad. But what this model of value actually shows us is that bad value is inherently bad no matter how gut/heart-wrenching the context. Every time bad value occurs, it is the worst thing that can ever be experienced. I propose that we take this equality between every instance of bad value as the basis for an ethical framework. Perhaps it’s possible that not all experiences of bad value are created equal: that some are worse than others. But if this were true, how could we know it? I see no grounds on which to speculate that some experiences carry more weight than others.

With bad value as its basis, I want to construct an ethics that resembles negative utilitarianism (if you know what that means…—it’s okay if you don’t), but stands as far as possible from the “Effective Altruists” (read: liberal cr*pitalists) who are most often associated with utilitarianism. I might call my ethics a queer nihilist anarchist anti-humanist negative utilitarianism to make clear the fact that I reject any bullshit definitions of “happiness”, “pleasure”, or “value” based on economic factors and suicide rates, and that I refuse to limit myself to political strategies committed to the legitimacy of the state or any other social, biological, or physical form. But I’m getting way ahead of myself.

I want to explain myself in my own terms. The ethical framework I’m suggesting begins with a (contestable) approximation of our situation: that there exist experiencers moving through time who experience isolated moments of good value, bad value, or no value; and that all instances of bad value are identical. Given this situation, the actual work of constructing an ethics is to determine how different options should be evaluated and to determine what constitutes an “option” in the first place. I suggest that we think of things in terms of “paths”. A path is a way forward into the future and details all of what happens and (most importantly) all of what is experienced along the path. A path is one possible image of what the future looks like, but also an image of how we get there and what happens after. To be technical, paths also extend backwards in time, but that part of the path is ignored because it’s assumed that we can’t affect the past. But maybe this is an overly dramatic explanation of something that is obvious and intuitive. You decide. Anyway, there are an infinite number of possible paths before us, and we can affect which one becomes reality by taking actions.

I suggest that we evaluate a given path by adding up, across time and experiencers, all the instances of good and bad value that occur along the path. Our job as ethical actors is to always make the choice that puts the world on the path with the fewest instances of bad value. (Admittedly, this interpretation makes me a little bit uneasy because it’s not totally grounded in experience. Because value is only ever experienced as an isolated event, one “path” will never actually be experienced as worse than another. It might make intuitive sense that we should want to minimize the number of experiences of bad value, but I’m not sure how to really justify this intuition.)

The reason I’m emphasizing reducing the amount of bad value rather than maximizing good value is that bad value is always more important than good value. The absence of good value is not a bad experience, so there is not an urgent need to increase good value. On the other hand, there is an urgent need to reduce bad value. I realize this is a pretty bad argument because it relies on you already having the intuition that bad value is infinitely more important than good value. What I want to say is that no amount of good value will ever make even a single instance of bad value worth it. As a result, we should only concern ourselves with maximizing good value when choosing between paths that have the exact same amount of bad value. In other words, good value only matters when bad value has already been minimized.

Establishing a method for evaluating possible paths introduces a new type of value. I want to be able to say that a certain action is “good” if it puts us on the right path. But when I say “good” here, I don’t mean that that action is good in the same way that the experience of good value is good. Good and bad experiences have “intrinsic” value, meaning that they are themselves literally good or bad. By contrast, an action can be—to take another word from Wikipedia—“instrumentally” bad or good depending on whether it leads to more or less bad value.

The ethical framework I’ve laid out so far gives us a way to determine the instrumental value of any possible action by looking at the intrinsic value experienced along the path that action puts us on. The framework tells us that, to the extent to which we know the effects of our actions, we can always act ethically—that we can always determine the least bad path possible and take the action that puts us on that path. The problem that immediately arises in any practical application of this framework is that, to a very large extent, we don’t know the effects of our actions. So we have to make our best approximations based on what we do know. Also, in practice, we can never really single out specific paths to choose from, but we can get a sense for the general sorts of paths we could try to move towards.

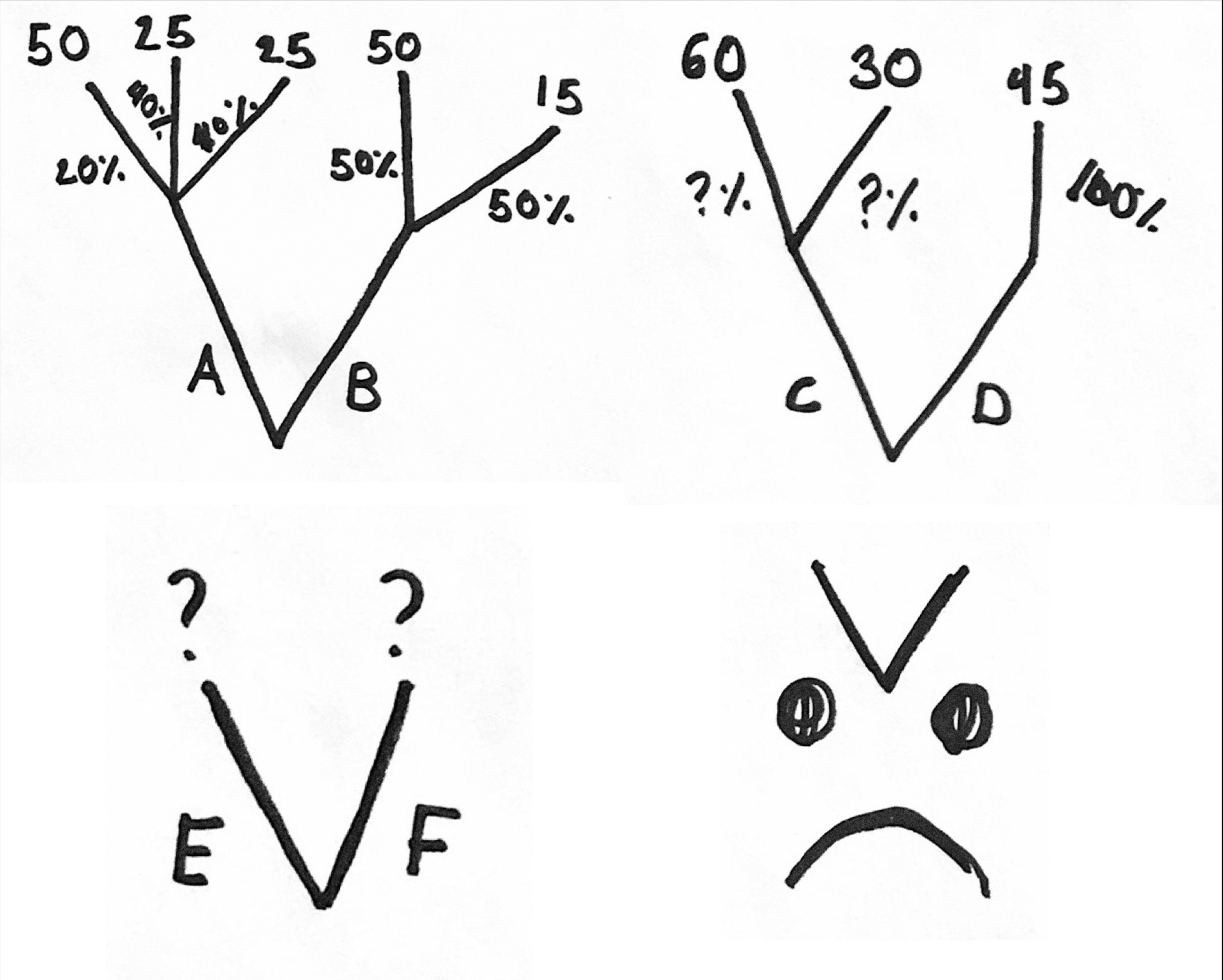

When trying to apply this ethical framework to real world decisions, it becomes useful to think in terms of the “expected value” of an action. Given a set of actions we might take, we can look at each action, identify the different paths it might result in, and approximate both the probability that the action will lead to each of those paths and the total bad value that would be experienced on each path. The first diagram below illustrates what I mean. A and B represent two actions you could choose between. We’ve somehow approximated that taking action A would have a 20% chance of bringing about a path containing 50 instances of bad value, a 40% chance of a path with 25 instances of bad value, and a 40% chance of another path with 25 instances. We can use this information to calculate the expected (bad) value of action A: E.V. = (0.20 × 50) + (0.40 × 25) + (0.40 × 25) = 30. We can do the same with action B to find that its expected value is 32.5. So in this case, even though action B would give us the possibility of a really good outcome (only 15 instances of bad value!), we should actually choose action A because its expected value is lower.

Even this “practical” approach has its limitations, however. The second diagram represents a scenario where we lack the knowledge needed to even approximate the probabilities of the paths resulting from action C. In this case, we’re unable to calculate C’s expected value, so the model gives us no way of deciding between C and D. The third diagram shows how sometimes we really know nothing at all. The fourth diagram shows how I feel sometimes.

In real life, things are never as simple and well-defined as in the diagrams I’ve drawn here. Also, in real life, taking the time to gather knowledge, analyze options, and make a decision is itself a decision with its own pros and cons. And a lot of times we just do things without any attempt to justify them at all. We are rarely in the position to go through the ideal ethical decision making process. Even so, it’s important to be clear on what this ideal process is so that when we do have to make rough approximations of how we should act, we can at least know which approximations are appropriate to make.

Anti-life

Identifying experience, and bad/good value in particular, as the only real sources of ethical value throws into question the validity of the “liberal” values mentioned earlier. Concepts like dignity, freedom, oppression, and exploitation claim to represent experience. These terms can be used to mean a lot of different things in practice, but there are certainly at least some formulations of these concepts that (semi-)concretely describe experience in ways that can be useful. However, it’s inaccurate and problematic to take these concepts as the basis for our ethics because they are not immediately derived from the experience of literal good and bad value. Although someone we identify as “oppressed” might experience more bad value than someone we identify as “free,” “freedom” is still a position plagued by bad value. Situating oppression and freedom as fundamental values gives us the (false and harmful) impression that a “good world” is simply one where every subject is free and not oppressed. “Liberal” values such as these may have originated out of an intuitive concern for experience, but they have since grown into something else. Words like “exploitation” and “(human) dignity” have come to carry a weight of their own, independent of their relationship to good/bad value, as if they were themselves inherently valuable.

The “liberal” practice that makes me want to give up and die the most is the valuing of life. The liberal approach to life is that it is sacred. In the liberal imagination, the worst possible thing you can do to a being is to kill it, and the one thing we are expected to avoid above all else is death—unless we are to heroically sacrifice our individual life for the cause of Life on a grander scale. Any liberal image of the future is one that contains life and is centered around the continuation of life. In fact, a future devoid of life is not considered a future at all. Life is conflated with hope, and without it we have no hope. Life is the ultimate liberal value. Its value is taken to be infinitely self-evident, and yet we can’t help constantly and passionately rearticulating it—in our poems, in our movies, in our political rhetoric.

But looking through the lens of literal value, it becomes evident that life, generally, does not have our best interests in mind. Similar to other liberal values, the valuing of life might be partly based on a concern for the bad value surrounding the loss of life: many experiences of dying could certainly contain bad value, and the experiences of loss surrounding death can also produce bad value. But the valuing of life has also become something arbitrary and alienated from actual experience. Liberalism celebrates life for its own sake.

This celebration of life as inherently valuable misses the fact that life is what makes the experience of bad value possible in the first place. Analogous to “cr*pitalism” or any other well-known evil social structure, life is a “biological structure” that creates us and shapes us into well-behaved, domesticated agents of its own reproduction, all while producing for us more and more bad value. Life is the precondition for all of the worst shit, and yet we find it hard not to love it. The liberal “pro-life” discourse works together with life’s biotechnologies (the various drives and processes that determine our behavior) to make it unthinkable to question life or to even understand life as a structure capable of being questioned in the first place. Rather than interrogating and dismantling life, we find ourselves constantly trying to redeem it. We turn experiences of bad value into works of art expressing the special sadness that makes life so beautiful. We might acknowledge that life is tragic, but we immediately consume that tragedy as fuel for the sad solemn somber aesthetic that makes our perceived duty to keep trudging forward feel bittersweet and romantic.

Even if we don’t romanticize life’s bad value, we still remain inexplicably committed to life. We see that things may be bad now and in the past, but we have faith that through a certain reorganization of the conditions of life, we will eventually reach a future where life is simply good. Or if our thinking isn’t quite this utopian, we might imagine a “liberated” future where there is still bad value, but things are somehow ideal. Perhaps we believe that our ideal world will never actually be achieved, but we see it as our duty to continually strive towards it. Some of us even see our struggles for a good world as “hopeless”, but believe that hopeless struggle is the only option. In all of these cases, our conception of the future is constrained from the beginning by the naturalized assumption that, above all else, life must go on. We settle for images of “liberation” that still contain bad value because imagining liberation as the absence of all life (and so the absence of experience and of bad value) is placed off limits for us.

But I don’t want us to simply reimagine liberation as the end of all life because the use of liberation as an ethical framework is itself flawed. When we organize our efforts around moving closer to a liberated future (which is what I mean by “liberation as an ethical framework”), we risk losing touch with experience and literal value. Even when the image of liberation that we’re working with is one devoid of bad value, the liberation framework can trick us into overlooking all the bad value that will happen between now and liberation. If we find it useful to think in terms of a long term goal, we need to consider the likelihood and timeframe of actually achieving that goal, the amount of bad value expected after achieving that goal, and the amount of bad value expected in the meantime. We cannot assume that liberation (however we imagine it) is our only option and that it is always worth whatever cost.

I want to hold onto the possibility of organizing our actions around the goal of ending all life (or at least decreasing the number of living experiencers as much as possible), especially since such a goal is so offensive and unthinkable within the pro-life discourse; but I also don’t know enough right now to believe, in good faith, that this approach to action would be the most useful/ethical one. When I say that I am anti-life, I mean that I reject the world’s pervasive valuing of and commitment to life and that I would kill everything right now if I had the chance; but I don’t mean to simply become entrenched in a new valuing of and commitment to the end of life. I also don’t mean to immediately reject all the thoughts and strategies that are currently being deployed in the service of pro-life causes. What I want is for us (me and you) to reconsider these thoughts and strategies from a perspective that is free from the constraints of the pro-life discourse (and the liberal discourse in general) and is instead grounded in a concern for the experience of literal value.

I want us to be critical of the analytical and political tools currently made available to us and also come up with imaginative new ways to use these tools—tools that were likely designed to only ever provide solutions within the realm of (human) life and society. We might rework the idea of the “social construction”, for example, by asking why we only ever apply our constructionist analysis to (what we recognize as) human “society”. Hasn’t everything else about our world also been constructed over time? if not “socially”, then “biologically” or “physically”? We should recognize the “natural” world as not natural at all, but a constructed structure that deserves as much criticism and reimagining as any “social” construction. We should be able to view life as a system like any other, producing experiences for us and using us to reproduce itself. We should be able to imagine life as something to be “abolished”.

The aspect of many “liberal” politics that feels the most urgently in need of reevaluation is environmentalism. There are many different motivations for taking an action that might be called “environmentalist”, some of which are grounded in a concern for experience. For example, we might wish to fight climate change in order to prevent a proliferation of “natural” disasters that would certainly produce bad value. But what really seems to be driving much environmental action is a concern for the continuation of life. Sometimes it’s that the earth must be protected as “our” (the human species’) only hope of survival, and sometimes it’s that the earth itself has a right to life that must be safeguarded, even at “our” (the human species’) expense. Either way, both nonhuman and human experience is being subordinated to a terrifyingly authoritative image of life as the ultimate value that takes precedence over all else. “Sustainability” rhetoric becomes much less wholesome when we see that what’s being sustained is an eons-old regime of bad value.

What we need is not to naively stop or reverse pro-life environmental actions, but to seriously reconsider their motivations and effects. It’s possible that we will find that some of our old tactics—such as the intervention in the cr*pitalist destruction of the environment—are still useful to us. But we might also develop our own approach to “destroying the environment” as a way of moving life towards its end, or at least shrinking its scope. Our “environmental sabotage”—informed by the bad value caused both by the continuing operation of the “environment” and by its destruction—would likely look very different from the cr*pitalist environmental destruction informed by a lack of concern for the experiences of others and for the future. It would be something intentional and caring, and it would certainly involve spending some bad value now so that experience on earth might dwindle away sometime before everything is swallowed by the sun or whatever. (And we better make sure Elon and Bezos and whoever else don’t manifest their destiny and let this shit escape the planet.) I don’t know enough about anything to know whether or not this is something practical to pursue or just a hopeless distraction. But the knowledge needed to determine the possible effectiveness of such a program of environmental sabotage is probably out there. We’ll need to liberate this knowledge from the thoroughly pro-life formations of environmental science and reorganize it in a way that is useful to us.

This is not to say that science is the only place we should be looking for knowledge. Of course there are other human sources of knowledge that are also of interest to us, but more crucially, we must work to access the knowledge of nonhuman experience that has often been made unavailable to us[1] by barriers to communication and/or human supremacist prejudice and/or not caring and/or whatever else. It’s crucial that we learn to notice nonhuman experience because of this fun fact: that the vast (VAST!) majority of experience is nonhuman. And yet so little of our attention is given to nonhuman experiences. It will be impossible to produce an ethical analysis of our situation that is even remotely accurate as long as we keep ignoring the majority of the experiencers on this planet. (We should care for any experiencers off this planet too, but I’m assuming we would have very little hope of finding and affecting them.)

While I’ve never heard any explicit discussion of this fun fact, I get the sense that some liberals would justify their fixation on human social issues by expressing that humans (and certain captive nonhumans) are the ones who need freeing; that the vast majority of nonhumans are already free because they are “wild” animals living out in “nature”. But while wildness surely has its advantages over domestication, wildness, like “freedom”, is not some perfect, purely good state. Whether while being hunted or freezing or starving or totally lost or embarrassed or when a friend dies or whatever else, wild creatures will experience bad value. So nonhuman experiencers cannot be so conveniently ignored.

Caring is scary because it will break you up. It might take some courage/recklessness to extend our care to nonhuman experiencers because it will break the human-centric, pro-life framework that many of us are comfortable with. But we need to break. We will always need to be broken up and re-formed.

Conclusion

To be honest, the images of good and bad value I’ve presented here feel inadequate. Sometimes I feel like there are experiences that I want to call bad that don’t really fit with the description of bad value I’ve given here. And sometimes I wonder if the terms “good” and “bad” can even tell the whole story of experienced value, and if my desire to impose this structure onto experience only serves to further naturalize the good/bad opposition that I’ve failed to question in the first place. I don’t want my engagement with experience to become an erasure of the experiences that don’t fit neatly into my structure. I know that by theorizing experience at all, I risk this erasure. But I find that some amount of theorization is necessary in order to “know” anything about the experiences outside of my present moment. If I were to accept that I can’t really know anything about anyone else’s experiences, or even about “my” own experiences in the past, then I would have no way to try to act ethically. (What the fuck does “ethical” mean and why do I want to be it??)

Although I started writing this thinking I had really cracked the case on experience, I now want to offer this as more of a first attempt at thoroughly treating experience as a basis for ethical action. But even if some of the specifics of my ethical framework will turn out to be inaccurate or inadequate or inapplicable, I do think some things will/should stick: that value is found only in experience, that our commitment to life is not supported by the reality of experience, and that all aspects of our politics touched by this pro-lifism (and the human supremacy that frequently accompanies it) need urgently to be reconsidered.

Anyway, that’s pretty much what I wanted to say. I wrote this so I could talk to people about it, so please let me know your thoughts. Send me an email, or write me a letter, maybe, and track me down and slip it into my bag when I’m not looking, with hugs and cuddles attached.

Sincerely as ever,

M

m.antilife@proton.me

p.s.

I really want this life thing to work out too. I like how the wind feels and the crashing ocean waves and all that, and I like the idea of all beings being together happily and wholesomely. I think of finally arriving home and ending all this missing, and I want it so bad. But I don’t think this is possible. Instead, this desire for the perfect world feels like a most enticing trap that aims to keep us in this shit for at least a couple billion more years, at least until the oceans start to boil. I wish everything was different. I wish god existed and was omniscient enough not to make a world where things can literally be bad. I experience a sadness that the world cannot be perfect. And then given that the world cannot be perfect, I experience a sadness that it exists at all—a double sadness which, by the way, does not contain bad value, but is nonetheless real. I think about the world ending, and it’s hard not to imagine it as a loss—a loss of all the warmth and highs and touching and being with and perfectness that should be—but I have to know that the world is not worth it, and that the emptiness that’s left when we’re gone will not be bad; it will be empty and ok.

[1] I’ve used we/us a lot in this “zine”, and it’s made evident here that that we/us assumes that you are human. It also assumes that you belong to a certain subset of humans who I imagine would be reading this. It’s true that I have a certain human audience in mind while writing this, but I don’t want to limit my possibilities by assuming that I will only ever work with humans.