Linda Lanphear and Jacqueline V.

Student Uprising in Mexico

Observations at the University of Mexico by Jacqueline V.

Excerpts from leaflets used during the Mexican student uprising.

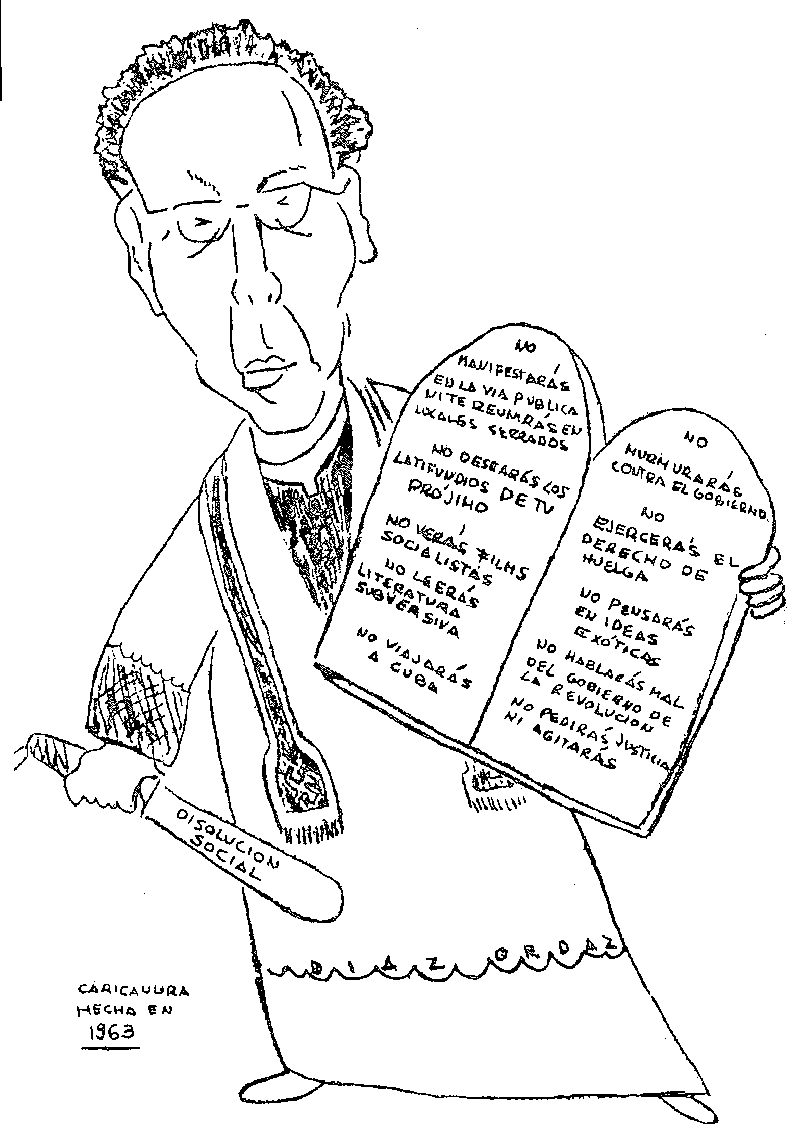

Translation of Mexican political caricature of President Diaz Ordaz; back cover of this issue

Background by Linda Lanphear

[Some of the details concerning the Mexican student uprising were obtained from the independent magazine Por Que?]

A bloody struggle between students and police took place in Mexico City during the last part of July and the first part of August. The violence began when the police broke into Vocational Schools #2 and #5, detaining and brutally beating both students and instructors. The immediate cause for this intrusion on the part of the police was a street fight between students from vocational and preparatory schools. 1 As there is great rivalry between these schools, the street fight that broke out on July 23rd was not an uncommon occurrence; indeed, it is “a very common thing,” as one student leaflet pointed out. The intervention of the police on the second day of the conflict, however, was both uncommon and unexpected.

To protest the police brutality, the leader of the pro-establishment National Federation of Technical Students (FNET), Jose Cebreros, obtained permission for his group to stage a protest march from the Ciudadela to the Casco de Santo Tomas. The date for this demonstration was July 26th, the same as that of another demonstration to be held by the Mexican Communist Youth (JMC) in support of the Cuban Revolution. When members of the first demonstration were dissatisfied with the turn-out of protesters, a faction of them decided to carry their demonstration to the front of the National Palace in the square known as the Zocalo. Cebreros, on the other hand, phoned the authorities who had granted permission for his demonstration and told them that it had ended peacefully but that a group of “radicals” were headed for the Zocalo to hold a meeting.

When the students arrived at the Zocalo they were dragged from the buses and beaten by the riot police who had been waiting for them, hidden in the side streets. The few who managed to get away went to the demonstration in support of the Cuban Revolution. They told members of this peaceful demonstration about the police attack that had just occurred. This combined group then returned to the Zocalo to support the Others and were met with more brutality when the police again sprang from their hiding places. July 26th ended with two burned buses; 16 people were wounded; 6 taken in by the Red Cross and 10 by the Green Cross. Four persons died.

On July 27th the students occupied their schools and warded off police by throwing rocks. That day the students took over 30 buses and used them to block off the streets adjacent to the Zocalo. During the night of July 28th students took over more than 100 buses. Each time the police tried to charge a school the students burned a bus. Characteristically enough, the police saw and used the opportunity to gain public support by provoking the students into burning buses, thereby “justifying” the brutality that they themselves initiated. These conditions continued throughout July 29th, punctuated by all-out battles between students and police. It was rumored that, by then, seven students had died. The police only admitted to one.

The climax came the morning of July 30th, when army paratroopers and motorized battalions arrived at Preparatory School #1. With the protection of tanks and vehicles armed with cannon and machine guns, the troops situated bazookas in front of the 400-year-old colonial door of the school and demolished it. The students were beaten and arrested at bayonet point while the other schools were being dealt with in the same way.

During that day the troops occupied the streets and schools. There were five fights between students and the army. Two students were machine-gunned. Those arrested numbered over 1200; the wounded had reached 400, 65 severely. It is being said that 60, 75, even 200 died.

Observations at the University of Mexico by Jacqueline V.

[Jacqueline V., a French student, went to Mexico in August. She gives some impressions of her visit.]

The campus of the University of Mexico, far from the center of the city, is composed of very modern buildings. The general atmosphere reminded me very much of Paris during the spring events: posters of the repression, of Marx, Che and even one obviously coming from Paris; groups of students conversing and then stopping to listen to an announcement given through a megaphone telling where a general assembly would meet.

With a Mexican student as my guide, I went to the general assembly of the medical students. The amphitheatre was full and though one of the speakers would make jokes about the government or the cops, the whole atmosphere was serious. Here were young people aware of the importance of what they were doing. At this meeting the discussion was concerned with the demonstrations of sympathy that were going on in Vera Cruz, the witnesses to the deaths and what should be done, and about organizing a demonstration on the part of the parents. (A few days later a meeting of the parents actually took place at the University; some 15,000 people attended.) One student advised that, instead of reading the newspapers, they should attend the information assemblies. It was asserted that no examinations would take place as long as the school program was interrupted. (One must remember that, in Mexico, the students are not on vacation.) And, of course, the program would remain interrupted as long as necessary.

Walking along the corridors after leaving the amphitheatre, I noticed that one room had been baptized “Nanterre,” a mark of sympathy with the French students. In a small room students were busily writing leaflets. They gave us various leaflets and magazines as sources of information. I was then introduced to a representative of the Information Committee. This is the interview I had with him:

Q. How do you happen to be able to work here in the university while the police have attacked the schools so savagely?

A. You know, they even used the army against the students and entered the polytechnical schools and what are called the vocationals and preparatories. And many students of the school of dramatic art are in jail. But the university is autonomous and it’s illegal for the cops to enter the university. [This autonomy is also the reason why the students’ rebellion could not be mistaken for a will of change inside the university but was immediately and obviously aimed toward social and political change. J.V.]

Q. What is the function of the different political groups?

A. The Socialist Party is against the students and supports the government. The Communist Party is sort of in favor of the students but its support is only abstract--and not even total. The role of the students belonging to the Communist Party is very small. On the other hand, the position of the Communist Party is a pretext for the government, which says that the students are manipulated by the communists.

Q. I understand that your general organization is the fight committee.

A. That’s correct. We have different groups; some are concerned with urban guerrilla activity, others are called “political brigades.” They go to town and to the factories to talk with the people. We feel that the Six Points can’t be obtained without popular agreement.

Q. What are the six points?

A. Liberty for political prisoners, destitution for three generals: the chiefs and subchief of the police; dissolution of the grenadier corps, indemnity for the dead and wounded, removal of the articles 145 and 145 bis; 2 assumption of total responsibility for the violence and vandalism on the part of the governmental authorities.

Q. What is the attitude of the population?

A. Our demands are met with sympathy. One must understand that the workers are very much under control and the union is in the hands of the government. Some groups showed their sympathy very openly. The veterinarians wanted to go on strike. That’s important because they control all the meat coming to town. However, they were not allowed to. The same thing happened to the bakers.

Q. Are the professors working with the students?

A. Yes they are. A professors’ assembly has already proclaimed total solidarity with the students, but the students remain the leaders of the movement. The teachers also are agreed that they won’t accept any examinations until the Six Points are obtained.

Q. Is anything going on in the other towns?

A. Yes. The government tried to prevent any contact with the other towns but there are strikes of solidarity and similar movements in the other main universities.

Q. What is the relationship between the Fight committees and the various radical groups?

A. Before the events, there were a few radical political groups, but this being a mass movement, they worked along with all the other students and none of those groups were given the opportunity to lead the whole movement.

Q. What is your own political line?

A. It is democratic and pretty much revolutionary. For instance, one of our slogans is “Viva la guerrilla de Gevaro Vasquez Rojas,” (“Long live the guerrilla war of Gevaro Vasquez Rojas”). This refers to a group which attacked an army fort in 1965 and was almost totally destroyed but which is now re-emerging and gaining strength.

Q. What were the main slogans?

A. “Press Shit!”

“Press Bought!”

“Without Police, No Disorder!”

“Books, Yes! Bayonets, No

In conclusion, the events that began in Mexico City during the last part of July are revolutionary in many ways. Before the events, only a handful of students were politicized. Now the entire student body is developing a radical political consciousness. They want radical social change and their aim is to be a real vanguard, a vanguard that carries the true interests of the Mexican people.

The students are aware not only of their own interests, but of the interests of the Mexican population as a whole. They call for student-worker solidarity and urge everyone’s participation. At every turn they emphasize the need to arouse the consciousness of the people. This they attempt through political brigades that go to factories and neighboring communities to dispense information.

Through their struggle the students reveal the repressive structure of the society and also show the possibility of fighting that structure. As their slogans illustrate, they also are aware that their actions have something in common with the guerrilla struggles. The student struggle is certain to have far-reaching effects in developing the political consciousness of the Mexican people.

Notes

1. Students who attend the “preparatorias” age from 17 to 19 and intend to continue their education at a university. The “vocacionales,” on the other hand, train students of the same age group in technical skills. The technical students’ equivalent to the university is the polytechnical institute where prospective engineers receive their training.

2. These articles define in vague and broad terms the conditions under which people may be arrested for the crime of “social dissolution.” As this law can be applied at the discretion of the “authorities” to anyone, anywhere, it functions in the interests of the status quo by allowing the arrest and detention of anyone accused of disrupting the peace.

Excerpts from leaflets used during the Mexican student uprising.

TO THE RAILROAD WORKERS:

Do you remember March, 1959? Do you remember that you were put in jail and beaten? That in that year the laws were not made for you? Remember your friend Vallejo who was on a hunger strike for days. Make yourself remember and you will realize that this movement is also your own and not only a student movement. Join the student protest demonstrations.

School of Medicine University of Mexico

TO THE GOVERNMENT:

We are opening our eyes in order to discover all of your corrupt acts. Our people have been afraid to protest because you would put them in jail, but WE ARE NOT AFRAID. We are all young people and our spirit clamors for justice, equality, respect for individual guarantees and the constitution, the freedom of speech and assembly, the exercise of a true democracy, and for the death of hunger and ignorance. DO YOU BELIEVE THAT THIS IS AGAINST THE PEOPLE?

School of Medicine

University of Mexico

Mexico lives. A people will not succumb to the whims of the powerful if it defends the cause of justice, civilization and humanity.

Fight Committee of Preparatoria 8

UNIDOS VENCEREMOS!

Translation of Mexican political caricature of President Diaz Ordaz; back cover of this issue

Thou shalt not demonstrate in the streets nor shalt thou assemble in closed areas.

Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s grand estate.

Thou shalt not see socialist films.

Thou shalt not read subversive literature.

Thou shalt not travel to Cuba.

Thou shalt not grumble against the government.

Thou shalt not exercise the right to strike.

Thou shalt not contemplate exotic ideas.

Thou shalt not criticize the Government of the Revolution.

Thou shalt not ask for justice nor shalt thou agitate.