Joseph Llewellyn

Envisioning an Anarcho‐Pacifist Peace

A case for the convergence of anarchism and pacifism and an exploration of the Gandhian movement for a stateless society

The Issue: Global Violence and Anarcho-Pacifism as a Revolutionary Solution

Exploring Anarcho-Pacifist Possibilities: The Contents and Scope of the Thesis

Theoretical Contribution and Finding my Audience

PART ONE: Anarcho-Pacifist Theory

Chapter One: An Anarcho-Pacifist Conceptualisation of Violence and Peace

Defining an Anarcho-Pacifist Peace

Chapter Two: From Pacifism to Anarchism and the Violence of the Capitalist-State

The Direct Violence of the Capitalist-State

Structural and Non-Lethal State Violence

The Role of Capitalism in State Violence

The Role of Racism and Sexism in State Violence

Chapter Three: From Anarchism to Pacifism and the Rejection of Revolutionary Violence

An Act of Violence is an Act of Domination

Excuses for Revolutionary Violence and Reasons to Dismiss Them

Excuse One: Violence as Necessary

Excuse Two: Violence as Inspiring and Virtuous

The Root Assumption: The Means of Violence Can Reach the Desired End of Revolution

Conceptualising an Anarcho-pacifist Nonviolence

PART TWO: Anarcho-Pacifist Vision and Practice: An Exploration of the Sarvodaya Movement

Chapter Four: Exploring Anarcho-Pacifist Theory Through Gandhi

Approaches to the Study of Anarchism

Anarchist Methodology: Conducting Anarchist Research via Interviews

Specifics of Inclusion: Exploring Gandhian rather than Euro-Centric Visions

Chapter Five: Gandhi, Sarvodaya and Nonviolent Experimentation

Critiques of the Sarvodaya Movement

Chapter Six: The Sarvodaya Movement’s Stateless Society: Gram Swaraj and the Constructive Programme

Economics, Production and Work

Truthful Engagement with Others: The Gandhian, Marxist and Anarchist approaches

Truthful Engagement in Gandhi’s Action

Is an Anarchist Leader an Oxymoron?

Is Gandhi’s Thought Relevant for Thinking About Political Organisation Today?

Gandhi’s Village in Modern Times

Thinking about Village Technology Today

Uplift Today: Women and Dalits in the Gandhian Struggle

Lessons from the Sarvodaya Movement

A Three-Pronged Approach to Change

How Anarcho-Pacifism Challenges Anarchism and Peace and Conflict Studies

Contributions of this Research and Future Research

Appendix One: Sharp’s 198 Methods of Nonviolent Action

THE METHODS OF NONVIOLENT AND PERSUASION

THE METHODS OF SOCIAL NONCOOPERATION

THE METHODS OF ECONOMIC NONCOOPERATION: (1) ECONOMIC BOYCOTTS

THE METHODS OF ECONOMIC NONCOOPERATION: (2 )THE STRIKE

THE METHODS OF POLITICAL NONCOOPERATION

THE METHODS OF NONVIOLENT INTERVENTION

Appendix Two: Gandhi’s 11 Vows and the Activities of the Satyagraha Ashram

Explanation : Languages other than Gujarati may be taught by direct method.

Abstract

The primary aim of peace and conflict studies is to build a world that is free from the suffering that results from violence in all of its forms. No political theories pursue this more than pacifism and anarchism: pacifism through its rejection of physical violence as a tool of politics and anarchism through its staunch opposition to the structural and direct violence that results from violent forms of authority. This thesis is an attempt to explore the rejection of violence and the building of a nonviolent world through the lens of anarcho-pacifism, which is the amalgamation of both anarchism and pacifism. The purpose of this is to answer the question of how we can create nonviolent societies that enable human flourishing. This is done in two stages.

In the first part of this thesis, an argument is made for the joining of anarchism and pacifism. Put simply, this argument is that because pacifists oppose violence as a method of politics, they should therefore reject the state, as the state is rooted in violence. This means that pacifists should adopt anarchism as an ideology and a practice. On the other side, anarchism can be defined through its opposition to domination and violent authority, and on this basis it rejects the state, capitalism, patriarchy and racism, along with any other past, present or future forms of privileging and violent hierarchical structures. The argument is made that if anarchism opposes domination, it should reject physical violence and killing, the ultimate form of domination, as a tool of politics and social transformation. In this way, both pacifism and anarchism come together in synergistic ways. Therefore, anarcho-pacifism is presented as a unique and revolutionary theory that fully rejects all forms of violence as a means and an end in its pursuit of a peaceful world. As a result, there is a theoretical case made that anarcho-pacifism offers great potential to build a nonviolent world.

The second part of this thesis is a preliminary exploration into how anarcho-pacifism can be practiced in the real world. This is explored through the Gandhian movement, both in Gandhi’s lifetime but also in the sarvodaya movement. The sarvodaya movement is the movement focused on achieving Gandhian ideals, during Gandhi’s lifetime and after his assassination. It was chosen for exploration as it was deemed to be the largest, most sustained, and most successful example of anarcho-pacifism in practice. Multiple academic contributions are made here. The first is that Gandhi’s anarchistic theory is explored, as well as his similarities and differences with anarchism, which has its roots in Europe. Second, the sarvodaya plan for a nonviolent anarchistic society is outlined using the writings of Gandhi and his principal successor, Vinoba Bhave. Third, the views and reflections of contemporary followers of Gandhi are shared, via in-depth interviews that were conducted in India and the United States. This research is therefore also an attempt to desubjugate Gandhi’s anti-state theory and practice, and highlight the thought and achievement of his successors – Vinoba Bhave and Jayaprakash Narayan – who are rarely acknowledged in nonviolence, anarchist and peace and conflict studies literature. In the final part of the thesis, some conclusions are offered about the Gandhian experience and what it can offer to similar movements in the future. Finally I discuss some challenges that anarcho-pacifism presents to peace and conflict studies.

Keywords: Anarchism, Pacifism, Anarcho-Pacifism, Gandhi, Sarvodaya, Nonviolence

Acknowledgements

As I think everybody who has ever written a PhD thesis can testify, the PhD journey would be impossible without the support and input of a long list of people. I would like to acknowledge them in the next two pages, although I do not feel that my words can fully express my gratitude.

I owe a great deal of thanks to my primary supervisor, Professor Richard Jackson. He has guided me through this project over the last few years by offering encouragement, reading many drafts, and helping me improve the work I have done via his feedback. Not only that, but if it was not for his teaching and the many conversations we had in the two years preceding this PhD project, I probably would not have started it at all. He has also offered his full support to various academic and activist projects that I have pursued throughout my time at the National Centre for Peace and Conflicts Studies (NCPACS). For all of this, I am extremely grateful.

I am also very thankful to my other supervisors: Dr. Charles Butcher, Dr. Marcelle Dawson and Dr. SungYong Lee. Charles gave me important feedback in the early stage of this project. Also, if it were not for the time, feedback and encouragement he offered as the supervisor for my Post-graduate Diploma and MA theses in the years preceding this PhD, I would not have built the foundations to do this work. Marcelle and SungYong have both given me very valuable supervision in the later half of this project. They have provided extremely helpful comments that assisted me in honing and clarifying many aspects of this work and provided helpful feedback on my teaching as well.

Throughout my post-graduate study I have been very lucky to be at NCPACS. Two NCPACS members who I must mention here by name are Griffin and Jonathan, whom I have spent most of my daylight hours over the last three years sitting next to in our office. Thank you both for providing relief when it was needed, chatting about work, providing feedback, collaborating on multiple projects and papers, listening to me complain, for offering reflections, and over all for just being great friends. I am very thankful to many members of the NCPACS community who have come and gone during my time here who have made NCPACS such as great place to be. There are many others who have been integral to the development of my work and I am unfortunately unable to mention all of them here by name.

Of course, without the time, generosity and hospitality of the tremendously inspiring activists, anarchists, pacifists and Gandhians, in Aotearoa New Zealand, the USA and India, this thesis would not have been possible. I am very grateful to all of them and I hope that in time we will create the nonviolent world that we seek.

I am thankful for the words of advice of my teachers and guides, Lama Zopa Rinpoche and Ven. Lhagon Rinpoche, whose guidance has kept me on track and which I aspire to completely live up to. I also need to thank the Dhargyey Buddhist Centre, who gave me a room to live in throughout most of this process, and which felt like a supportive nest to retreat to. The Dhargyey Buddhist Centre has also always offered support for the various peace projects I have kicked off or been involved in during my time studying at NCPACS.

Last but certainly not least, I want to thank all of my family and my wonderful partner, Nicole. Without years of support, sacrifices, presence and encouragement throughout life’s many ups and downs from my Mum and Han, I would not have reached this point. Nicole, who I met within three weeks of starting this project, has been my rock throughout. I am extremely grateful to have her in my life.

It is through the kindness of all of these people that I was able to reach this stage and enjoy the journey along the way. To quote the late Geshe Jampa Tegchok: “if we think about the great kindness of all beings it will be evident that all our happiness does indeed depend upon them.”

Introduction

The greatest challenge of the day is: how to bring about a revolution of the heart, a revolution which has to start with each one of us?

– Dorothy Day (1963, p. 210)

About seven years ago, I took a tuk-tuk[1] from the centre of Phnom Penh and travelled about 15 kilometres to the Choeung Ek killing fields. The remains of almost 9000 bodies have been excavated from mass graves on the site with many graves left untouched. Many of those killed at Choeung Ek were previously tortured in Phnom Penh’s notorious S-21 prison. In Cambodia, about 1.7 million people, one fifth of the population, were killed by the Khmer Rouge (Kiernan, 2003). They killed all who opposed them and many connected to those who opposed them, in order to try and prevent retaliation and to maximize their control. Alongside this, the Khmer Rouge’s Year Zero social engineering campaign starved 300,000 people to death in a resultant famine (Hauveline, 2001).

When you walk around Choeung Ek, there are multiple scenes that become etched into your memory. There is a tree, as the sign next to it states, “against which executioners beat children”. Bullets were considered too precious to use, so the executioners had to find other ways of murdering their victims. Another tree, called the “magic tree”, had a loudspeaker hanging in it, which was used to drown-out the sounds of death. There are many hollows in the ground where the mass graves are. From these hollows, fragments of bone, teeth and clothing still rise out of the ground and are collected and put into see-through containers around the site. In the centre of the site is a large stupa[2] with big glass windows. Through the glass you can see 5000 skulls of victims piled from the floor to the ceiling, many with visible signs of trauma.

I walked around Choeung Ek for about an hour, before sitting down and looking at the stupa for a while, with a deep sinking feeling inside, as if I had been kicked in the chest and my chest was now hollow. While many years have passed since the Khmer Rouge’s genocide, the cracked skulls held within the stupa offer a glimpse of what physical violence is, of its nature. Physical violence is about inflicting suffering and pain. It is about destruction and injury. It is horrific. When you are presented with the skulls, clothes, teeth, and bloodstained trees, violence can no longer be abstracted, or discussed as if it is simply a neutral political tool.

As I sat looking at the stupa, I had an opportunity to think more about the gut-wrenching response I was feeling to what was in front of me. I realised that the violence that had been committed where I sat was not just about the act of killing, murder by evil individuals. It was an extreme example of the violence that can be committed by a so-called revolutionary group in the name of change. It is also an extreme example of the violence that can be committed, and arguably would not be possible, without a state. The Khmer Rouge represents a total bastardisation of what communism is meant to be; however, it also represents the logical end point of revolutionary violence, which aims to remove all challengers to reach its desired ends. The Khmer Rouge also demonstrates the violent potential of a state with a monopoly on, and a huge capacity for, violence, without which atrocities such as the Cambodian genocide would not be able to occur.[3]

While looking at the stupa, I made a strong reaffirmation of the pacifist commitments I had already made, and a strong commitment to do what I can, where I am, to prevent violence and work for the removal of violence in all of its forms. After getting up and leaving the killing field, I passed a person who was selling tied string bracelets on the side of the road. I brought the bracelet with a peace symbol in the middle of it and tied it to my wrist as a symbol of my reaffirmed commitment. It remained there for a number of years before the string broke. It is from this moment that I started to make changes, which, along with some additional life alterations, led to me signing up to a post-graduate peace and conflict studies course, and ultimately, two qualifications later, to writing this thesis.

Walking around Choeung Ek was a defining moment for me, because although I was already an activist, and already committed to nonviolence, I made a big step away from the communism, Trotskyism and Leninism that I had been drawn to as a teenager. I had been drawn to it because of its vision of a nonviolent world, but had, I now think naïvely, assumed that nonviolence could be integrated into Marxism. Maybe it can, but currently Marxists do not speak much of nonviolent resistance or the inherently violent nature of the state. I had been involved in Marxist groups, but this experience gave me the push I needed to step away from my attempts to reconcile my pacifist commitment with Marxism, and towards other traditions that were both radical and truly nonviolent. Here, I leaped away from Marx, Che, and Lenin and started to explore more deeply nonviolent radical traditions such as anarcho-pacifism, and Gandhianism.

On top of the Choeung Ek stupa, above the 5000 skulls, are figures of the Garuda and the Naga, two mythical animals, the first a bird and the second a snake. The two are natural enemies, trapped in a cycle of violence. On the top of the stupa, they hold each other up as a symbol of peace and reconciliation, as a representation of flourishing rather than suffering, and in this context, a symbol of moving away from the horrific violence of genocide to a place where this horror cannot happen again.

This leads me to the premise of this thesis. How can violence be stopped, allowing the Garuda and Naga to come together, breaking the cycle of violence and abolishing the means of violence? How can a truly nonviolent society be created? My conclusion, which I aim to substantiate and explore throughout this thesis, is that nonviolence cannot be created through the horror of violence. While revolutionary social transformation may be necessary, it cannot happen with the logic and action of revolutionary violence. It also cannot happen while there are political institutions, namely, the state, defined by a monopoly on violence, that along with a violent economic system, namely, capitalism, maintain and enact many other forms of violence upon people. It is from these thoughts that I aim to explore anarcho-pacifism and along with it, the interconnected but also unique theory and practice of Gandhian nonviolence. This is because they both reject direct violence, including killing, and they reject violent political and economic institutions. At the same time, they may offer insights into an alternative way of being and an alternative way of getting there. I am interested both in their theory and how they can be practised in order to create nonviolent societies.

The Issue: Global Violence and Anarcho-Pacifism as a Revolutionary Solution

The last one hundred years have seen many moments of optimism for those who want to create a nonviolent world. Many of these moments have either been caused, or greatly influenced, by popular peoples’ movements. For example, we have seen the end of direct colonial rule around the world as popular movements have challenged and removed rulers and colonisers. This included Gandhi’s demonstration of mass revolutionary nonviolence, which has been used many times since in various ways. The civil rights movement and anti-apartheid struggles played a large role in reducing the violence of racism. We have seen the rise of feminism and women’s movements that have challenged patriarchy. We have seen a rise in universal suffrage. Peace movements around the world have challenged war and contributed to an increased cynicism of war. Many countries, as the result of popular workers’ movements, increased the support that they offered to their citizens as governments were forced to take some responsibility for welfare and the regulation of working conditions. We have also seen the breaking of symbols of authoritarianism such as the Berlin Wall, and the consideration of human rights has become more mainstream.

Unfortunately, despite these moments of optimism, it is clear that we do not yet experience a nonviolent world. Many forms of violence that have been opposed by progressive movements have largely remained intact. Specifically, I refer to: the perpetuation of war, its consequences, and its ever-increasing lethal possibilities; an economic system – capitalism – that is based on exploitation, oppression, and dispossession; systems of political power – states – that rely on top-down control; and pervasive bigotry in the forms of patriarchy, racism and disablism. This is not to say that the nature of these systems of violence has not changed, but rather that they are still being perpetuated. At this current moment, little seems to stand in their way as the political left, globally, seems small, reactive, and largely uncreative. Much of its time is spent in opposition mode rather than on creating new ways of being and a positive vision of the future. Writing in 2018, one hundred and one years on from the Bolshevik revolution, and 154 years since the formation of the First International, radical popular movements have not made the changes they yearned for. We have seen communist hopes of equality turn into the Soviet Union, the gulags, civil wars, invasions, authoritarianism and Mao’s great leap forward. Other revolutions faded as they could not maintain or protect themselves, such as the anarchist revolutions in Catalonia and the Free Territory of Ukraine (Orwell, 1970 [1938]; Peirats, 1990; Skirda, 2004).[4] There are many other progressive movements that have not achieved a social revolution at all.

While leftist revolutionary movements have not been able to achieve their goals, another proposed road to peace, the liberal-democratic project, has arguably failed. The optimism about the liberal democratic project that was present at the fall of the USSR and heading into the millennium has now all but faded with a resurfacing of racist, rightist sentiments in the heart of liberal-democracies. The war on terror, the election of Donald Trump as President of the USA, and the increased power of populist right-wing parties in Europe, as well as popular movements such as the alt-right, are all examples of this. In addition, neoliberal economic reforms promoted by liberal democracies have only resulted in increased global and national inequalities, and the world’s leadership seems utterly unable and/or unwilling to solve pressing world problems such as those caused by the looming and increasingly current threat of climate change.

It is here, in a lull of leftist creativity and thought, and in an atmosphere of increasing pessimism about the possibility of a peaceful world that I start this thesis, and ask: how do we create a nonviolent society that facilitates human flourishing? And what kind of politics is able to take us further than other popular movements have so far? More specifically, what approach could take us beyond a politics that rests on violent authority and division, to one of bottom-up democracy? What approach could take us beyond an economic system based on exploitation, dispossession and oppression, to one based on the needs of the earth and its inhabitants? What approach could take us beyond division and bigotry to a politics of nonviolence that entails an ethics of uplift, care and support rather than division and contempt?

Peace studies, at least in recent years, has largely avoided these big questions. Discussions about the creation of positive peace, the absence of all violence, and the obliteration of structural and cultural violence have all but disappeared in the top peace studies journals (Gleditsch, Nordkvelle, Strand, Buhaug and Levy, 2014), as has a radical imagining of what could be. Most research and practice is focused on the creation of negative peace, the absence of war, and limiting physical violence. While it is undoubtedly beneficial to limit war, this narrow focus is not capable of creating a positive peace — a nonviolent politics and nonviolent economics that would allow people and the planet to thrive.

The aim of this thesis is to explore an often-overlooked theory and method of peace making and explore its practice and potential solutions to global violence. Anarcho-pacifism, an amalgamation of both anarchism and pacifism, is a world-view that is committed to nonviolent revolution. It involves a specific critique of politics, authority and hierarchy and a belief that nonviolent societies can be created and maintained. I will argue that anarchism and pacifism are theories that contain the potential to overcome some of our world problems and create a positive peace, especially when they are practiced together as anarcho-pacifism.

The word anarchy is traced by Proudhon, an early anarchist thinker, to the ancient Greek a narkhos – meaning without government – not chaos as the word is commonly assumed to mean. Anarchism is a philosophical position that questions authority and rejects and resists it if it cannot justify itself (Chomsky, 2013). I will suggest that it is a political position that rejects all violent authority – authority that leads to domination and/or exploitation. Pacifism, often mistaken for passivism, is “…the view that war, by its very nature, is wrong and that humans should work for peaceful resolution of conflict” (Cady, 2010, p. 17). Pacifists reject passivity and work for peace. Another key component of pacifism is a “commitment to cooperative social order based on agreement” (Cady, 2010, p. 30), a position held in common with anarchism. It is fair to say that pacifism has in the past been acknowledged in peace studies, and there is currently increasing support for the exploration of nonviolent civil resistance as a means of change for downtrodden peoples. However, anarchism has rarely, if ever, been explored in the field. The closest it may have come is through the study of Mahatma Gandhi in the early days of the discipline, but these are brief, distant discussions that focused mainly on Gandhi’s nonviolent use of force, rather than his vision of a nonviolent society that would have been anarchistic in nature. Of course, anarcho-pacifism is by no means the only theory that aims for the creation of a peace that rejects the capitalist-state. Others have asked similar questions and come up with their own answers. Most of these are in either the Marxist traditions or broader anarchist traditions. Many of them will be referred to in this thesis.

Exploring Anarcho-Pacifist Possibilities: The Contents and Scope of the Thesis

This thesis is split into three parts. The first makes a theoretical argument for anarcho-pacifism. I argue that peace scholars and revolutionaries should engage with and investigate anarcho-pacifism, as there is reason to believe that it could have a unique potential to help create nonviolent societies. This is because, unlike other methods of social change, it fully rejects violence — physical, structural and cultural — as a means and an ends, thus opening the possibility for a nonviolent world. As a key part of this, I challenge the use of violence as a tool of change, and make an argument for the rejection of violent forms of authority: authority that leads to oppression and/or exploitation. This leads me to conduct a major critique of the violence of the capitalist-state. From an anarchist perspective, the capitalist-state could be seen as the biggest instigator of violence in the world. It is the most dominant system of power and control.

In this thesis, I will argue that anarchism and pacifism naturally fit together. In summary, I will make this argument through justifying the following sub-arguments. Pacifists oppose violence as a method of politics, and should therefore reject the state, as the state is rooted in violence (as I discuss in Chapter Two). This means that pacifists should adopt anarchism. On the other side, anarchism can be defined by its opposition to domination, and from this it rejects the state, capitalism, patriarchy and racism, along with any other past, present or future form of privileging and violent hierarchical structure. If anarchism opposes domination, it should reject physical violence and killing, the ultimate form of domination, as a tool of politics and social transformation (as will be discussed in chapter three). The anarcho-pacifist position can be summarised in three key points, which set it apart from other leftist thought and peace-making theories:

-

The rejection of violent authority. The existence of violent authority represents the antithesis of peace because it necessitates structural and cultural violence. Importantly, this anarchist stance against violent authority leads to the rejection of our capitalist-state dominated world system as peaceful and also rejects the capitalist-state as a means to peace.

-

The rejection of physical violence. This is a pacifist rejection of physical violence as a means of change that can lead to peace. Combined with the anarchist stance of point one, this means that anarcho-pacifism supports revolutionary rather than reformist methods of change, but rejects violence as a means of revolution. To go one step further, it sees violence as inherently counter-revolutionary because it reinforces existing structures and modes of power.

-

The promotion and creation of ways of being that allow people to live without violence. This is both an anarchist and pacifist stance that seeks to create ways of living and organising that are nonviolent, and foster and encourage ways of living and organising that are already nonviolent. This allows people to learn how to meet their needs in a way that is conducive to peace, and for us to reconstitute ourselves into existing and thinking in peaceful ways.

The second part of this thesis is an exploratory study of anarcho-pacifism. More specifically, it is an exploration of anarcho-pacifist politics and action by looking to Gandhi and the Gandhian Sarvodaya movement in India. This may seem like a strange place to explore anarcho-pacifism, at least to people who are unfamiliar with Gandhi’s anarchistic practices. However, Gandhi is looked to as the case for exploration for two reasons that will be justified more through the thesis. The first is that Gandhian nonviolence fulfils the three summary points presented above, which define anarcho-pacifism. For all intents and purposes, Gandhian political and economic thinking fits neatly within the definition of anarcho-pacifism that I have given because it is committed to nonviolence, recognises means/ends consistently, rejects violent authority including the state, aims to create bottom-up democracy, and seeks to develop an economic model that is based on the needs of all sentient beings and the planet, and is therefore opposed to capitalism. The second reason is that the Gandhian movement, during Gandhi’s lifetime and after his death, is by far the largest movement that has fulfilled these three points, at least in recent history. This is true in regard to the size and the impact of the scale of the nonviolent resistance that the movement was engaged in, but also in regard to the scale of their experiments in living nonviolently and their expansive theory of how this can be done. Other anarcho-pacifist traditions have not existed on the same scale. Considering this led me to the conclusion that the exploration of the Gandhians would offer more insights and examples into how anarcho-pacifist principles can be practiced on a large scale than the study of any other movement could.

The broad purpose of exploring the Gandhian movement is to start to explore visions of anarcho-pacifism, by researching the knowledge, experiences, and views of different generations of activists who have followed this path. The key way in which the Gandhian movement is explored in this research is through interviews with people who are following in Gandhi’s footsteps, in the modern day. This is assisted and preceded by an outline of the Gandhian plan for the nonviolent society, using key texts. I created a summary of this plan by referring to key writings of Gandhi and one of his principal followers, Vinoba Bhave.

Initially, the vision for this thesis was to explore manifestations of anarcho-pacifist practice over the two traditions, the Gandhian and the European. As a result, I had conducted interviews with twenty-five activists/proponents of nonviolence based in the USA, India and Aotearoa New Zealand. All rejected violence as a means and an end and held an anarchist, or at least, an anarchistic, worldview. In other words, they seek to create change and achieve justice through nonviolence, and reject violent authority; instead, they seek human freedom, which entails the creation of a decentralised and non-hierarchical society. While all interviews offered valuable insights into how anarcho-pacifism can be lived, I could not do justice to them by putting them all within the confines of this thesis, and, for the reason explained, I have put the anarcho-pacifist interviews to one side to use in future work.

The anarcho-pacifist tradition coming out of Europe is the only one of the two to explicitly label itself anarcho-pacifist, with its members sitting within the European anarchist and pacifist traditions.[5] In the USA, for example, there are multiple traditions of anarcho-pacifism that have been practiced and developed by the likes of Dorothy Day and the Catholic Workers movement, by Quakers, students, and members of the Movement for a New Society (MNS), the Ploughshares movement founded by Daniel and Phil Berrigan, by a range of anarchist collectives, by people like Paul Goodman, and by some members of the Beat Generation, and of course, in the anti-war movements with some members of groups like the War Resisters League being anarcho-pacifists. Other significant groups, historically, have been the Tolstoyan Communes that were set up around the world, along with other Christian influenced communities that held similar principles (Alston, 2014).

The second movement — the thought, philosophy and practice of Mahatma Gandhi and his followers — does not use the term anarcho-pacifist. It is focused on the creation of a society based on sarvodaya, meaning the welfare of all. The first half of the thesis is framed in the language of anarcho-pacifism which differs from the language of Gandhi; Gandhi and his followers have many of the same conclusions about the problems of the world and what is needed to fix them. I am not the first to make the direct link between Gandhi and Anarchism (see Ostergaard, 1985; Ostergaard and Currell, 1971; Doctor, 1964; Woodcock, 1972; Kumar, 2004, p. 377). However, I do not want to simply label Gandhi as an anarcho-pacifist. I will briefly address the reason for this now, in this introduction, and more substantively in the fourth chapter of this thesis.

While the European Anarchist and Gandhian traditions of nonviolence are distinct, they also share strong connections. Gandhi and his followers were a huge influence on anarcho-pacifists in Europe and the USA (Ostergaard, 1982), especially as Gandhi showed the world how nonviolence can be wielded on a large scale. It is harder to say that the influence is as great the other way around, although Gandhi was influenced and moved by the writing of well-known anarchists such as Leo Tolstoy and Henry David Thoreau. Gandhi also read two of the most prolific anarcho-communist and anarcho-syndicalist thinkers, Kropotkin and Bakunin (Dalton, 1993, p. 21; Woodcock, 1972). Tolstoy and Thoreau were also read by some of his followers, along with the likes of Kropotkin.[6] He also corresponded with Dutch anarcho-pacifist, Bart de Ligt.

Despite this, it is my view that it would be a disservice to Gandhi to subsume him under a Euro-centric anarcho-pacifist label. While Gandhi was influenced by anarchists, his philosophy of nonviolence and visions of a nonviolent society are indigenous to, and firmly rooted within, India (Shah, 2009). Gandhi did not, while he was alive or now, need to look to a European theory for solutions to violence that has been instilled in Indian society or for the emancipation of Indians living under colonial rule. These issues will be discussed in detail later in the thesis, but I mention them briefly here just for the purpose of accurately framing my argument from the outset, and to explain the exploration of the Gandhians in this research.

It is important to note, as I have now made clear, that I do not aim to write about anarcho-pacifism as if it exists as one stream of homogenous thought, with one set of practices and solutions. It is a world-view held by different groups and people that inspires different solutions within different contexts, spaces and times. It can be seen as a set of root principles on how violence exists and how nonviolence can be used and experienced in order to remove violence. It follows then, that there could be many different anarcho-pacifisms. Indeed, Gandhi and many others fit comfortably under a broad anarcho-pacifist umbrella, recognised for their various conclusions and experiments that aim to do away with physical, structural and cultural violence as a means and an end.

In summary, in the first part of this thesis, I make an argument for anarcho-pacifism — for a nonviolent politics that rejects physical violence, violent authority, and searches for nonviolent ways of being. In the second part, I point to and explore the sarvodaya movement, which aimed to implement anarcho-pacifist principles. The argument I present in this thesis and the conclusions I make should not be seen as definitive of anarcho-pacifism. Others justify their anarcho-pacifism in different ways and enact it in different ways to the Gandhians. The Gandhians, while enacting an anarchist or anarchistic pacifism, do not explain their position in the same way that I champion anarcho-pacifist nonviolence and politics, despite the two being consistent with each other.

Although I pose this as an exploratory study of anarcho-pacifist practice, I am not conducting a study of all who fit under the anarcho-pacifist umbrella. In this sense, I am very limited in the comments I can make about the representative nature of my findings. The reason I initially conducted interviews in the three selected countries, the USA, India, and Aotearoa New Zealand, was because all have unique traditions of anarcho-pacifism that have developed in relative isolation, with different challenges.

The final part of the thesis summarises the Gandhian approach and puts the discussion of anarcho-pacifism, along with the Gandhian practice and insights, into direct conversation with peace and conflict studies theory and practice. Here, I will finish the thesis by outlining ways in which anarcho-pacifism speaks to the problem that peace studies is concerned with: the creation of a nonviolent world. I finish the thesis by concluding that anarcho-pacifist politics are not unrealistic, but can be liveable and usable. They require us to experiment in new ways of being rather than offering a complete prescription of a nonviolent society. I will argue that there are multiple areas of peace and conflict studies research that share common ground with anarcho-pacifist politics, and these can be built upon in the future.

Theoretical Contribution and Finding my Audience

I think that it is important to state outright that I have found this a difficult task. The key reason for this is that I have found it difficult to speak to or even find my audience/s. This is because this research bridges disciplines, rather than fitting solidly under one. The fields I am bridging are: first, peace and conflict studies, and within this, the study of pacifism and nonviolence; second, anarchism and anarchist studies; and third, Gandhian studies. The subject matter speaks primarily to anarchism and pacifism, drawing on Gandhi. An articulation of anarcho-pacifism is rare in both peace studies and anarchism, and this is the key research gap that I am trying to fill. Within peace studies there is an increasing body of work that looks at mass nonviolence, but little on anarcho-pacifist communities and individuals.

The theoretical contributions I have sought to make in this thesis are: to define anarcho-pacifism and its theoretical foundations; to outline the violence of the capitalist-state, which peace studies and pacifism pays little attention to; to question the method of violent revolution, which has been accepted by large strands of anarchist theory as a necessary or productive way to create nonviolent societies; and to explore the Gandhian sarvodaya movements experience of trying to enact anarcho-pacifist politics. The task of finding my audience is made even more problematic, as different parts of this research speak more strongly to some fields than others. For example, discussions about structural violence and the violence of the capitalist-state (see Chapter Two) speaks to peace and conflict studies and pacifism much more than it does to anarchist studies. Anarchism already rejects these things, whereas peace studies rarely recognises the capitalist-state as an impediment to peace. On the other hand, discussions about violence being an unproductive method for creating revolutionary change (see Chapter Three) challenges much anarchist thought, but does not strongly challenge peace and conflict studies, which, as a whole, views nonviolence as a more effective way of creating change compared to violence.

These issues have made it difficult to get the balance right as I make my arguments, and throughout the process I have received contradictory feedback on how best to do this as I have presented my work. I will share two sets of examples to illustrate this. First, many comments I received early on in my PhD journey were contradictory in regards to my discussion of the violence of the capitalist-state. On one side, I was told that I needed to spend a lot of time justifying the position that capitalism is violent, because this was not obvious. On the other side, I had multiple people advise me that that I did not need to spend much time talking about structural violence and the violence of capitalism, because this was quite obvious. Another piece of advice that stuck in my mind was that I should not use the word anarchism in my work, as peace and conflict scholars would not pay attention to it. To follow this advice, of course, would undermine the premise of this research.

Trying to talk to multiple positions and fields of study has been challenging, so I sincerely hope that I have struck the correct balance, while acknowledging the fact that some people who may read this will want more or less justification for different sections of this research. At times, this project has felt like an overly ambitious task to do within the confines of one thesis. However, a piece of advice I received earlier on in my journey was that it is better to take a difficult swing at a harder question, than an easy swing at a less interesting or challenging one. I have tried to follow this advice.

My main contribution leads to a sub-set of contributions, which are especially relevant to the second part of the thesis. The first is highlighting the anarchistic vision of Gandhi, which is largely ignored or has not been looked at by many pacifists and peace scholars. Moreover, I discusses the Gandhian movement post-Gandhi, which has rarely been done within peace studies, and thereby aiming to bring peace and conflict studies up to date in regards to Gandhi. Gandhi was integral to the early work of many important figures in the field, such as Johan Galtung (Galtung and Næss, 1955; Weber, 2004) and Gene Sharp (1961), but his contemporary relevance and practice is not currently explored. Second, work on pacifism has been quite Eurocentric. It makes reference to Gandhi, but has not evolved or developed Gandhi’s anarchistic approach. Finally, I show that Gandhi has relevance to Anarchism. Despite the Gandhian movement being one of the largest and longest running examples of anarchistic action, it has been largely ignored by Western Anarchists, with Geoffrey Ostergaard’s work being the notable exception (Ostergaard, 1985; Ostergaard and Currell, 1971).

As these contributions show, this research offers more to peace studies and anarchist studies, than it does to Gandhian studies. This thesis presents a case for anarcho-pacifism, with reference to, and exploration of, the Gandhian movement. In this way, I engage with anarchism and pacifism, and look to the Gandhian approach to explore a lived experience of enacting the theory I am presenting. I offer very little to Gandhian literature which already deals with Gandhi’s anarchistic vision, except for pointing to the fact that there is another set of movements, those that are called or have called themselves anarcho-pacifist, that share major similarities. While saying this, as I will expand on in multiple places throughout the thesis, much Western work on Gandhi does not explore his anarchistic ideals.

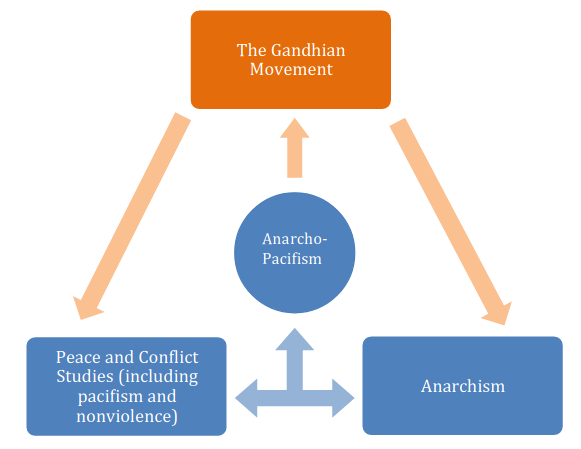

To assist with explaining where I see this research fitting, I have included the diagram below (Figure 1). This research on anarcho-pacifism is positioned between three fields of study: peace and conflict studies, anarchism and Gandhi. The blue part of the diagram represents the first half of the thesis, as I make arguments for anarchism to become pacifist, for pacifism to become anarchist, and for the two to come together as anarcho-pacifism in order to create peace. The second half, represented by the orange part of this diagram, shows the exploration of how anarcho-pacifist theory can be lived by looking to the Gandhian movment, which then offers lessons back to peace and conflict studies, anarchism, and together as anarcho-pacifism.

My Positioning

I write this thesis, as I have mentioned, as somebody who identifies as an anarcho-pacifist. My worldview, in terms of my political beliefs, is a kind of anarcho-communist-pacifism, with a strong affinity towards Gandhi. In this sense, I have an investment in the research. This research is therefore focused both on making an argument for anarcho-pacifism and for exploring it further. This means that this thesis can be seen as, firstly, a normative theoretical piece of work. The second part is an empirical exploration. A full discussion of the methodology of this research is included at the beginning of section two, but it is important to highlight from the beginning that this work is an engagement in activist research and praxis.

Activist research “comes about through long-term commitment to the struggle and those in it, and through critical engagement with what’s going on in that struggle” (King, 2016, p. 8). As a teenager, I was drawn towards nonviolence, and from this, communism, due to its aim of creating of an equitable and non-oppressive society. This led to me spending a few years in a Trotskyist group in my late teens to early twenties. Over time, as I studied more and engaged in more activism, it became clear to me that my own views and experiences did not fit neatly with Leninism/Trotskyism/Marxism as revolutionary theories. Issues regarding the acceptance of physical violence as just and productive grated with me from the beginning.

As time went on, I became increasingly cynical of the way that class relations were seen as the root of oppression in Marxist theory. I increasingly saw many lines of domination along with class struggle, all of which are forms of violence to be opposed and appeared to exist in an interrelated but not necessarily dependent manner. This led to me leaving the group, not long before my trip to Cambodia, and engaging in a few years of organising and learning with like-minded people: organising large and small protests, study groups, film screenings, printing papers and pamphlets, and debating. From here, through nonviolence and my rejection of Marxist-communism, I started to explore anarchism and its rejection of the state, and Tibetan Buddhism and its ethics, system of logic, and the Bodhisattva ideal. At about this time, I started to engage formally in peace and conflict studies, completing a Post-Graduate Diploma and a Masters of Arts thesis, both focusing primarily on the practice of nonviolence. This process has led to a tearing down of the Che Guevara poster that graced my wall as a fourteen-year-old, as I replaced him with pictures of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama and Mahatma Gandhi, in my early twenties. It has led to a personal commitment to explore anarcho-pacifist nonviolence as a political tool for peace, and engage in its practice both intellectually in this thesis, and practically in my activism and everyday life.

My activist background and world-view provides the basis for calling this activist research. It is the reason I ask these questions. This research seeks to make an intervention in the activist and academic communities I am involved in that aim to create nonviolent societies. In this way, it is political and ideological. The majority of the interviews I conducted were with people who shared similar beliefs and goals as me. However, I have not been directly involved in their day-to-day activism (I had never been to the USA or India before this project). Hence, this is not participant action research in an anarcho-pacifist organisation, but a broad exploration of the ideas and actions of anarcho-pacifism.

It is praxis-based, in that I aim to learn about anarcho-pacifist practices that can contribute back to anarchist-pacifist activism, as well as advocate for the possibilities of anarcho-pacifist peace making and further research into anarcho-pacifist peace making. I also aim to bring together some dispersed examples of scholarship, resistance and activism under one banner, as very few writings on anarcho-pacifist theory look at anarcho-pacifism as a whole. They tend instead to focus on studies of particular key people or movements. This research offers a critique of existing violent systems of power, an exploration of what a nonviolent world could look like, and questions what the necessary factors are for revolutionaries and peacemakers of all kinds to create nonviolent societies.

Outline of Chapters

As I have mentioned, this thesis contains three parts. Part one makes an argument for the anarcho-pacifist position of revolution, nonviolence and peace making. I start Chapter One by defining violence and peace from an anarcho-pacifist perspective. I suggest that a peaceful society is one that prioritises human flourishing. It does what it can to promote human flourishing and not hinder it. Human flourishing can only exist in a society that rejects physical, structural and cultural violence as an option of politics. As a result of this, I label anarcho-pacifist peace as a eudaimonious peace, a concept I will introduce in the chapter.

In Chapters Two and Three, I do two things. First, I examine what an anarcho-pacifist politics would reject as violent. Second, I explain how anarchism and pacifism can naturally come together to form a nonviolent politics that rejects physical, structural and cultural violence as a means and end for peace making.

In Chapter Two, I make an argument, primarily aimed at pacifists, for why pacifism should be anarchist and in the process, lay out a justification for the anarchist rejection of the capitalist-state. In Chapter Three, I make an argument, primarily aimed at anarchists, for why anarchism should be pacifist and, in doing so, champion revolutionary nonviolence rather than revolutionary violence.

In Chapter Four, I move onto the second part of the thesis, as I outline my methods and the details of my exploration. This second section is about exploring anarcho-pacifism by looking at the sarvodaya movment’s experience and theory. Here, I start to explore anarcho-pacifism as an approach to creating peace. As I have made clear, I do this by exploring the anarchistic theories and practices that come out of the Gandhian movement. In this chapter, I justify the case selection further, and introduce the interview participants and the approach I took to conducting the interviews.

In Chapter Five, I introduce the Gandhian movement, briefly outlining Gandhi’s life and contribution along with that of two of his most important followers, Vinoba Bhave and Jayaprakash (JP) Narayan. I also provide a brief overview of some concepts and terms that are necessary for understanding the Gandhian worldview. This leads directly onto Chapter Six, in which I provide an outline of the Gandhian plan for a nonviolent, anarchistic, society of village republics. I do this primarily by drawing on the writings of both Gandhi and Vinoba.

In Chapters Seven and Eight I focus on the thoughts of the interview participants and their reflections on Gandhian political organisation and action. These two chapters are based on key topics that arose from the interviews. Chapter Seven focuses on how to engage with others: adversaries, allies, and friends. Chapter Eight focuses on the ins and outs of political organisation.

Part Three is made up of one final chapter. In Chapter Nine, I offer some conclusions to the Gandhian case study. I then bring anarcho-pacifism and the Gandhian insights into discussion with peace and conflict studies as a whole, outlining some areas of peace and conflict studies research that this research can speak to.

PART ONE: Anarcho-Pacifist Theory

Chapter One: An Anarcho-Pacifist Conceptualisation of Violence and Peace

Any situation in which “A” objectively exploits “B” or hinders his and her pursuit of self-affirmation as a responsible person is one of oppression. Such a situation in itself constitutes violence, even when sweetened by false generosity, because it interferes with the individual’s ontological and historical vocation to be more fully human.

— Paulo Freire (1996 [1970], p. 37)

Anarchism: The philosophy of a new social order based on liberty unrestricted by man-made law; the theory that all forms of government rest on violence, and are therefore wrong and harmful, as well as unnecessary.

– Emma Goldman (1969 [1910], p. 50)

In the introduction to this thesis, I argued that the two political positions of anarchism and pacifism fit together. Before discussing in detail how and why anarchism and pacifism come together, and what anarcho-pacifism could offer for the creation of peaceful societies, it is important to explain what is and what is not peaceful and violent, according to the anarcho-pacifist worldview. Anarcho-pacifist vision of peace is the antithesis of violence. Without delving deeper into these definitions, it is not possible to understand what anarcho-pacifism challenges (violence) and what it aims to create (peace), as the precise meanings of the words peace and violence can hold different meanings in other fields of study, activism, politics and philosophy.

In the anarcho-pacifist conceptualisation of peace that I will present, peace is a condition where incidents of violence are limited as much as possible. This allows humans (or we could go beyond this to say all sentient beings, and the environment) to flourish unhindered by the activity of other humans. In fact, it goes further, namely to flourish with the support of other humans. This large-scope anarchist aim has been dismissed by many as unrealistic and naïvely utopian; a position that this thesis seeks to challenge. The structure of this chapter will be as follows: first, I will discuss the conceptualisation of violence; second, I will discuss the lines between violence, authority, coercion and power; finally, based on what I have written, I will offer a more detailed definition of anarcho-pacifism and its definition of peace.

Conceptualising Violence

I cannot claim that the conceptualisation of violence that I am about to describe is exactly what is held by all of those who label themselves as anarcho-pacifists. As will be discussed in the following chapters, both anarchism and pacifism are not absolutely homogenous positions. Having said this, I believe that the position I am about to describe is consistent with the overall position that anarcho-pacifists take – the rejection of all forms of violence and the aim of assisting human flourishing — even though I may arrive at that position using different sources and drawing on different thinkers.

Many philosophers and political theorists have sought to deal with the questions of what violence is, whether the use of violence is morally acceptable, whether or not it is avoidable, and whether or not it can have productive outcomes. This chapter addresses the first of these questions on a theoretical level. The remaining three questions — whether violence is avoidable, acceptable, or productive — will be addressed in the following chapters where I will delve deeper into the pacifist and anarchist worldviews, along with examples of how violence manifests.[7]

Plentiful definitions of violence posit its nature in quite different ways. Tyner (2016, p. 31) suggests that this is because violence is always an abstraction; there is no thing called violence that has “an existence that transcends time and space.” However, we often presume that there is. Tyner (2016, p. 8–9) writes that, “in arguing against a transhistorical concept of violence, I postulate that violence (and, by extension, crime) is an internally derived abstraction that is a contingent and contextual project of human interaction.” In politics, especially when discussing radical politics, protest and resistance, this confusion often leads to problematic discussions about violence. I will use the example of protests to briefly demonstrate this, as this topic is pertinent for the exploration of anarchism and pacifism. In protests, definitions of violence used by activists (including anarchists and pacifists), the state, and the media, become particularly problematic due to their different positions. Different actions and inactions are viewed and labelled by the observers as violent or not violent, or more violent or less violent, depending on one’s point of view and agenda. In other cases, levels of, or what is called violence and what is not, can be manipulated for political gain.

I will briefly illustrate this with two examples of social movements in the United States: the anti-globalisation movement, focusing specifically on the 1998 World Trade Organisation (WTO) protests in Seattle; and the Black Lives Matter movement, 2013-current. These cases are selected for purely illustrative purposes. Putting questions about the justification and legitimacy of violence to one side for the time-being, in both cases we can see different views of what is and what is not seen as violent when discussing these movements/protests from the perspectives of activists, the state (including the police) and the mainstream media (and consequently, many people watching).

In November 1998, tens of thousands of protesters blocked intersections in downtown Seattle in order to protest the WTO conference that was being held in the city. Activists were protesting as a reaction to corporate globalisation and capitalism and/or neoliberalism and/or free trade. They saw these as being responsible for deaths, poverty, and environmental destruction, which ended or limited the lives of the world’s most vulnerable people. Protesters shut down many parts of the city using nonviolent tactics and disrupted the conference. They were met by police. The protests become known for the violence that ensued in parts of the city as some protesters damaged property and the police cracked-down on protesters. However, as I will now demonstrate by using quotes from newspaper articles that were published at the time of the protests, what the various participants labelled as violence were often quite different things.[8]

The view of the protesters was that large-scale violence is committed by the WTO, and any violence that occurred in the protest paled in comparison. The Cincinnati Post (1999) quoted a protester in Seattle as saying that: “The corporations commit way more heinous crimes” than other violence seen in the clashes. A letter to the editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch a few days after the events (Cohn, 1999) also demonstrates the same view:

Much has been made of the violence done to Seattle’s downtown shops by black-clad “anarchists.” The irony is that a few shattered shop windows are receiving more media attention than the large-scale violence visited on people all over the globe by the World Trade Organization.

Protesters also see the crackdown on protesters by police as violent, and sometimes blame violent responses from protesters on them. A piece in the Washington Post (Babington and Burgess, 1999) quotes a protestor who experienced police violence: “Cynthia Hill of Washington, D.C., said she and a large group of protesters had blocked off a street yesterday and stood together peacefully. Hill said two police cars drove into the crowd. ‘I have bruises all over my legs.’”

Other papers quote protest leaders as viewing the WTO, and the police who were defending the WTO event, as violent. The Cincinnati Post (1999) wrote that: “Protest leaders pointed fingers at overreacting police and a few bad apples within their own ranks.” Reuters (Hillis, 1999) wrote that:

The almost festive mood of Friday’s march by about 1,000 people through downtown streets matched that of Thursday’s demonstrations, and speakers took pains to condemn the earlier violence — which they blame largely on the police — and call for healing in the community.

While protesters viewed the WTO and the police as perpetrators of violence, the state, and the media often viewed the protesters as the perpetrators of violence. This was the dominant discourse. This is especially true of the Black Bloc who were a minority in the protest group in Seattle. The Black Bloc are a group of protesters who make a tactical choice to dress in black and conceal their faces to make themselves unidentifiable. They then engage in property damage which they do not see as violence. By breaking the symbols of capitalist-globalisation they aimed to challenge its legitimacy (Paris, 2003). Whatever the motivations of Black Bloc members, their sentiments were not reflected in mainstream media responses to their actions. An example from an article in the Daily Express (1999) entitled “Grim spectre of violence that shocked America” writes that:

More than 68 people were arrested. A small group of protesters, possibly 200 strong, are thought to have been behind most of the attacks on buildings and cars. Dozens of businesses were vandalised.

This segment from Reuters (Charles, 1999), which contains direct quotations from the White House spokesman, shows a similar definition of violence:

…‘Although Clinton is in favour of people expressing their views,’ White House spokesman Joe Lockhart said the president was upset when he saw footage of the violent demonstrations in Seattle which led to mass arrests both on Tuesday then again on Wednesday. ‘He was particularly angry at the indiscriminate violence and vandalism,’ Lockhart told reporters.

These articles clearly depict the protesters as violent. It is important to note that the Black Bloc does not aim to kill anybody and sees itself playing a protective role over other protesters when they clash with police – for example, if they draw the police away from other protesters. If they do accept that they are using violence, they certainly see it as much less significant than the violence of the police and corporate globalisation. This is important, because it shows that the use of the term “violence” here is not about killing, but about property damage and disrupting business. When searching for news articles on the event I found no counter-narrative in the mainstream media that wrote about the deadly consequences of globalisation, or which labelled the WTO as violent. The alternative viewpoint was only mentioned when and if they quoted protesters, as above, and was not the voice of the media.

In regard to police crackdowns, members of the police force and onlookers may have seen police as “keeping the peace”. Rather than being violent, they are ending the violence of the protesters as they restore order. The same piece from the Washington Post (Babington and Burgess, 1999) demonstrates media and state views on what is violent, including the views of the police and the president. They wrote, “As hundreds of Seattle police in riot gear restored order by sharply restricting protesters’ movements and arresting 400 demonstrators, the World Trade Organization got down to business”, and, “Tuesday’s sometimes violent street demonstrations that forced the mayor to declare a curfew and the governor to send in National Guard troops.” They add that, “Clinton and other officials blamed Tuesday night’s disturbances on a relative handful of violence-bent demonstrators.” Similar sentiments are found in other papers. For example, in the Daily Express (1999) article mentioned above, riot police who were clearly taking action that could harm others, are not portrayed as violent, as they write, “Shop windows were smashed and a masked mob looted goods as riot police struggled to regain order, firing tear gas, and rubber pellets as well as pepper at the crowds.”

Police saw themselves as being restrained, the sensible ones, despite being the ones using physical force on the crowds of people, the majority of whom were not using physical violence or even damaging property. In the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, we see participants in the movement condemning violence from police in cases of individual police officers shooting black people (mostly unarmed black men), as well as the violent handling of protesters (Gass, 2016). More broadly, BLM members see violence as part and parcel of a white supremacist culture that exists within the police force, and wider society, which means that people of colour are subject to violence more often and more severely than white people. This comes in the form of harm to their bodies (for example, through death or imprisonment) and through other ways of indirectly limiting their life potential (for example, higher poverty and unemployment rates). Onlookers or police may see any abuse towards the police as a form of violence, with it being clear that some police officers oppose the movement (Seelye and Bidgood, 2016). Others view the concept “black lives matter” as a form of violence because they say that “all lives matter”, or even “cops lives matter”. The New York Times (Seelye and Bidgood, 2016) writes about a group of police attempting to remove a BLM banner from a town hall because they see the movement as encouraging violence against themselves:

“Because some elements identified with the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement have resorted to killing innocent police officers and putting the lives of citizens in jeopardy, the Massachusetts Municipal Police Coalition cannot stand for the continued display of that organization’s banner on a public building,” Michael McGrath, an officer of the coalition and the president of the Somerville Police Employees Association, told the crowd. As he spoke, officers from two dozen nearby cities and towns, wearing street clothes, stood quietly around him, and television helicopters hovered overhead. The police unfurled a large blue banner that read “Cops Lives Matter” and held posters saying “Support Your Local Police.” About 100 residents looked on. The police unions want the mayor to remove the “Black Lives Matter” banner and replace it with one saying “All Lives Matter.”

In both examples, it is clear that the views within these groups — protestors, the state and the media – do not overlap. However, I use these examples merely to demonstrate the range of what the term violence describes, and, just as importantly, what it does not describe. In these two examples, what is viewed as violence describes a range of actions towards bodies, objects and the environment; as a visible process and an invisible process; between individuals, small groups, or across societies and the globe; and depending on who is viewing the action. In short, what is viewed as violence depends on who is labelling the violence.

It is clear that the view of what is and is not violence in different groups is often contradictory. Police using physical force against protesters in Seattle cannot both be violent and peaceful; these are the antithesis of each other.[9] In the BLM example, the police actions imply that it is black people in the BLM Movement who are being violent through exclusion, suggesting that they don’t think other lives matter, and also by provoking physical violence towards police. The police seemingly ignore the deaths of black people at the hands of police. This does not fit with the point of view of the BLM movement: that black people are disproportionately subject to violence at the hands of police; at the hands of a white supremacist culture; that the term ‘all lives matter’ acts to dismiss violence directed disproportionately towards people of colour and ignores or suppresses their voices; and that the term ‘black lives matter’ does not dismiss the value of other lives.

Given the uses of the word violence in the cases above, is violence a useful word, and is there any agreed common ground between the different parties? Despite contradictory uses of the word “violence”, it is fairly clear that direct harm is usually seen as a form of violence. This harm is key to using the term, although it is clear that what the harm is – against protesters’ bodies or shop windows – is selected quite deliberately to fit one’s political agenda. When Bill Clinton ignored police violence and focused on the actions of the Black Bloc, he was clearly being selective about whom he wanted to condemn. He was not taking a stance against violence, as the police clearly caused harm — harm to people’s bodies by trained and armed police that was overwhelmingly more forceful. When police in Boston talk of the “violence” of not stating all lives matter, they selectively ignore the harm caused by armed police who kill black people at a rate far higher than they kill white people. However, my point is that despite the wilful blindness towards the harm committed and the proportions of and severity of the harm, they still need to suggest there is “harm” to label an act or person as violent.

It is probably quite clear to most that intentional physical harm is violent. For example, most would see murder as being violent, and this would be hard to deny by anyone. It may be less clear to people as to whether or not systems and structures that allow direct bodily harm to occur are violent, or even whether or not these systems exist, as in the case of racism and white supremacy, both of which are clearly rejected, consciously or not, by the police officers described above. Systemic violence is much easier for the powers that be to deny, I suggest, partly because it is less visible, and partly because it is seen as a norm rather than an exception like a murder. In relation to this, Tyner (2016, p. 27) suggests, that killing is often viewed as violence, but ‘letting-die’ is often not, despite the two having the same outcome: death. So while murder is generally accepted as violence, when a decision is made by a government to cut spending on healthcare, and that spending cut denies adequate healthcare for somebody in need — despite the existence of the wealth, recourses, technology and knowledge that could help that person — and that person dies, this is not often labelled as violence. This relates back to the Seattle protestors’ view on the WTO, which they blame for committing violence towards many people in the world in much the same way.

What I have written so far suggests that the word violence is either: (1) used without thought to its meaning, without a precise definition; (2) it is used to provoke an emotional response or as political positioning, for example, to get support for crackdowns on protestors; (3) it is not often used in cases where it could or should be, where unnecessary death and suffering still occurs. This critique does not, however, mean the term violence is meaningless, or should be used haphazardly. Anarcho-pacifism has a precise and a broad definition of violence that both encompasses and broadens the popular discourse beyond direct physical violence between individuals who wish to cause bodily harm. It is broad in its scope, but specific in what it means. The basis of anarcho-pacifism, as stated above, is allowing and maximising human flourishing. Put simply, an anarcho-pacifist definition of violence is any human action that unnecessarily restricts the flourishing of others. Taking this position, it is clear that an anarcho-pacifist definition of violence must not only include killing but also “letting-die”, as well as any form of social organisation or production that allows killing and letting die. It goes further still, because being alive does not necessarily imply flourishing. Shortening life and restricting possibilities to thrive therefore entails violence. Consequently, any definition of violence that is only concerned with physical violence is too restrictive for anarcho-pacifism. This position also deals with issues such as a surgeon amputating a limb, thus causing harm, but ultimately to save or improve life and therefore assist with flourishing.

This perception of what violence is and is not fits well with the definition of violence provided by Johan Galtung. Galtung (1969, 1990) offers a broad definition of violence that can be interpreted as being consistent with the anarcho-pacifist concern for human flourishing. He defines violence as, “the avoidable impairment of fundamental human needs” that “lowers the actual degree to which someone is able to meet their needs below that which would otherwise be possible” (Ho, 2007, seen in Leech, 2012). He then splits it into three different forms:

-

The first is called direct violence, and this includes physical and psychological violence (Galtung, 1969). From this definition, it is clear that causing death and injurious physical harm is direct violence.

-

The second is structural violence, which Galtung (1969, p. 171) describes as social injustice, coming from social structures. Graeber (2006, p. 76) suggests that structural violence is often reinforced and maintained by the threat of force. Using examples from above, denying healthcare, or not funding it sufficiently, and letting people die is a form of structural violence.

-

The third, cultural violence, “makes direct and structural violence look, even feel, right — or at least not wrong” (1990, p. 291).

All three are interrelated, and there is no reason to think that one causes more suffering than another (Galtung, 1969, 1990). All three prevent, in different ways, human flourishing which is the aim of anarcho-pacifism. Galtung’s definition of violence can be applied back to the Seattle WTO protests and Black Lives Matter examples in order to further highlight the anarcho-pacifist position on what is and is not violence.

From an anarcho-pacifist standpoint, the reason for the emergence of these protests/movements in the first place is clearly violent. The description of violence stated suggests that the actions of the WTO and more broadly, capitalism and corporate globalisation, are forms of structural violence that lead to direct violence. They have negative effects on people and the environment, through exploitation, oppression and the denial of resources, all of which hinder what would otherwise be possible.10 In Black Lives Matter the same can be said about the violence of racism and white supremacy, leading to the disproportionate deaths of black men at the hands of police. In both examples, protesters would view the police crackdown as a form of direct violence, as well as any attacks on police; both are intended to cause bodily harm, hindering flourishing, as well as preventing the protestors from successfully making large-scale change.

Whether property damage (seen mostly in the Seattle protests) is violent or not is slightly more complicated. Anarchists do not normally see property damage as violent, as damage to property, certainly in this type of protest, does not generally restrict human flourishing. Richard Solnit (McHenry, 2015, p. 24), an organiser of the Seattle protests, elaborates on this point:

I want to be clear that property damage is not necessarily violence. The fire fighter breaks the door to get the people out of the building. But the husband breaks the dishes to demonstrate to his wife that he can and may also break her. It’s violence displaced onto the inanimate as a threat to the animate. Quietly eradicating experimental GMO crops or pulling up mining claim stakes is generally like the fire fighter. Breaking windows during a big demonstration is more like the husband. I saw the windows of a Starbucks and a Niketown broken in downtown Seattle after nonviolent direct action had shut the central city and the World Trade Organization ministerial down. I saw scared-looking workers and knew that the CEOs and shareholders were not going to face that turbulence and they sure were not going to be the ones to clean it up. Economically it meant nothing to them.

Solnit suggests that the aim of the property damage is key to whether or not it can be seen as violent. The fire-fighter clearly does not hinder flourishing. The threatening husband certainly does. However, it is important to point out that the symbolic nature of breaking windows is hardly likely to result in any hindrance to human flourishing, and if it did inspire others to join the anti-capitalist movement, it may even help. However, it is also entirely possible that this kind of action could lead to workers losing their jobs during a cost-recovering process, which would be a type of violence.

A clear-cut example of where property damage could also be seen as violent is, for example, if vital infrastructure such as a hospital was destroyed, thereby denying medical care to those in need. Another example is the bombing of cities in war, or other attacks on infrastructure that harms people both immediately and in the long-term if it cannot be replaced, causing structural violence – for example, roads are destroyed that prevent people from reaching the hospital or from food supplies reaching a town. However, when talking about property damage in relation to the movements above, this is less relevant as war is not being used as a tactic, and the damage did not involve the same destructive capabilities.

Verbal abuse from protesters or police in both examples could be seen as a form of cultural violence if it, consequentially, helps any direct violence feel right. In regard to the media coverage, a lack of critique of the violence of corporate globalisation (assuming for now that it is violent), or a lack of critique of the violence of racism, or a of lack coverage of either’s effects, is a form of cultural violence as it puts a blanket over the structural and direct violence that is being committed, making the violence invisible or acceptable. On the 2 December 1999, an article in The Independent (1999) claimed that a media blanket silenced the protests while they were happening. They wrote:

The dozens of network and cable stations that shelved regular programmeming to show such spectacles as the O J Simpson car chase, the phalanxes of terrified children running out of Columbine High School and the office complex in Atlanta where a gunman was on the loose, offered viewers precisely nothing… There was no live, open-ended coverage of the “battle in Seattle” on American television; it was not until yesterday that viewers were shown the scale of the disturbances, by which time it was history, and edited.