Jim Donaghey

The ‘punk anarchisms’ of Class War and CrimethInc.

Punk, anarchism, ‘lifestylism’ and ‘workerism’

CrimethInc.’s lifestylism (and their anti-lifestylist detractors)

Class War’s anti-lifestylism (and their lifestylist tendencies)

Abstract

Many of the connections between punk and anarchism are well recognized (albeit with some important contentions). This recognition is usually focussed on how punk bands and scenes express anarchist political philosophies or anarchistic praxes, while much less attention is paid to expressions of ‘punk’ by anarchist activist groups. This article addresses this apparent gap by exploring the ‘punk anarchisms’ of two of the most prominent and influential activist groups of recent decades (in English-speaking contexts at least), Class War and CrimethInc. Their distinct, yet overlapping, political approaches are compared and contrasted, and in doing so, pervasive assumptions about the relationship between punk and anarchism are challenged, refuting the supposed dichotomy between ‘lifestylist’ anarchism and ‘workerist’ anarchism.

Introduction

Punk, anarchism, ‘lifestylism’ and ‘workerism’

Punk and anarchism have been significantly intertwined for more than 40 years. From ‘early punk’s’ shock tactic invocation of anarchy,[1] a deeper relationship quickly developed, and this interrelationship has been evident in punk’s continued development and global spread. While this genealogical link to their ‘early punk’ forebears remains vital, contemporary punk scenes defy many of the wider stereotypical assumptions conjured by ‘punk,’[2] not least in the influence of anarchism on the punk scene, as evident in DIY production practices and in the imagery and lyrics of punk bands.[3] The relationship is also evident in the reciprocal influence of punk on the anarchist movement, both as a politicizing influence on individuals and as a cultural bedrock for various elements of the anarchist movement.[4] Particular activisms such as Food Not Bombs, squatting, hunt sabbing and antifa are especially associated with punk—though the relationship is not limited to these and is also evident in grassroots trade union groups like the IWW[5] and other syndicalist groups.[6] There are numerous examples of anarchist activist groups which are in one way or another identifiable as ‘punk,’ but certainly two of the most prominent are Class War (active in the UK since the early 1980s, with wider influence in places such as Ireland and Australia) and CrimethInc. (active in the US since the mid 1990s, with international influence, including many non-English-speaking contexts). The relationship between punk and anarchism is viewed as problematic, and even damaging, by some sections of the broader anarchist ‘movement’ (and by some punks too), but while both Class War and CrimethInc. have been criticized for their particular approaches, it is hard to refute their huge influence within the anarchist movement in recent decades. Both groups have published prolifically and each has enjoyed considerable longevity, and as such, they provide a wealth of material for analysis and comparison when thinking about their respective explications of ‘punk anarchism.’

A key tension in discussion of punk and anarchism is that between ‘lifestylism’ and ‘workerism,’ and CrimethInc. and Class War, despite both being identified as ‘punk’ anarchists, are associated with opposite ends of this tension—CrimethInc. as lifestylists, Class War as workerists. By way of succinct, though certainly not definitive, descriptions: ‘lifestylism’ denotes anarchist perspectives which consider personal and cultural politics to be pre-eminent to revolutionary activity;[7] ‘workerism’[8] denotes anarchist perspectives which focus exclusively on the worker and workplace as the agent and site of revolutionary struggle—this is usually couched in materialist economic analyses, but (perhaps contradictorily) is also often combined with an emphasis on ‘classist’ identity politics. It should be stressed from the outset, however, that the terms ‘lifestylist’ and ‘workerist’ are not much more than pejorative slurs used to exaggerate differences in philosophy and tactics between various strands of anarchist activism. The terms do not fully or accurately reflect any substantially existing anarchist perspective but are rather used to conjure fuzzily imprecise straw figures for polemical attack. Perhaps the best way to understand these terms, then, is through a negative definition: ‘workerism’ eschews personal or cultural politics; ‘lifestylism’ lacks concern for class analysis or workplace organizing. And further, these positions are antagonistic to one another, so ‘workerism’ is more clearly understood as ‘anti-lifestylism’ and ‘lifestylism’ as ‘anti-workerism.’ Despite the essential baselessness of these terms, they remain (stubbornly) current in movement debates—so they are employed here, even as they crumble under interrogation.

As Sandra Jeppesen notes: ‘subcultural component[s]’ of the anarchist movement, including punk, are often conflated with ‘what Murray Bookchin[9] deridingly calls “lifestyle anarchism,”’[10] and this conflation with the lifestylist caricature has some grounding, as exemplified by influential punk anarchist zine Profane Existence: ‘We have created our own music, our own lifestyle, our own community, and our own culture … Freedom is something we can create everyday; it is up to all of us to make it happen.’[11] This lifestylist reading of punk is picked-up by Laura Portwood-Stacer as well, who suggests that lifestylism and punk have concurrent and related geneses and that this association is a persistent (though problematic) one:

[T]he fact that many who became involved in punk scenes lacked a deep understanding of anarchist history or political philosophy meant that their enactment of anarchist principles could, at times, be fairly limited, remaining at the ‘shallow’ level of their individual lifestyle choices. This was what earned them the pejorative labels of lifestyle anarchist or lifestylist … lifestylism has retained its connotative associations with the anarchopunk sector of the broad anarchist movement.[12]

Sean Martin-Iverson also identifies the lifestylist/punk association and notes that this relationship is critically viewed as ‘a reduction of the class struggle tradition of social anarchism to a commodified “counter-cultural” identity.’[13] Craig O’Hara notes a problematic association between punk and lifestylism, which he characterizes as a ghettoizing tendency to ‘stay within their own circle and … reject … the possibility of widespread anarchy.’[14] Some criticisms of punk anarchism are directed from older anarchist groups which pre-date punk’s emergence in the mid-to-late 1970s. For example, Nick Heath, a regular contributor to the long-standing periodical Black Flag,[15] writes that punk-inspired anarchists were ‘very much defined by lifestyle and ultimately a form of elitism that frowned upon the mass of the working class for its failure to act.’[16] This focus on class speaks to the tensions between lifestylism and workerism, as also identified by Daniel O’Guérin,[17] who writes that punk ‘espoused lifestylist politics … without seeming to grasp the implications of the wider class struggle. In consequence some see punk as a distraction from the work that really needs to be done.’[18]

The issues of class and class consciousness are somewhat ambiguous in punk—and this speaks to a core divergence between the lifestylist and workerist caricatures. McKay, writing about the DIY movement in the UK during the 1990s, argues that it ‘present[ed] itself as being blind to class (that is, is dominated by middle-class activists).’[19] This points to lifestylism’s argued lack of engagement with class analyses, and lifestylists’ perceived position of class privilege, which either goes unrecognized or is unaddressed. Discussing the Indonesian punk scene, Martin-Iverson argues that ‘punk repositions and rearticulates class rather than transcending or displacing it’[20]—this déclassé concept is discussed in more detail later. Of course, some punks are highly concerned with class, often in terms of class identity, especially evident in the lyrical tropes and aesthetics of genres such as Oi! and street punk. However, this focus on class as an identity politics frequently descends into a crude ‘classism’ which contradicts conceptions of class as a primarily economic relation—so even when class does appear as a key tenet within punk, its implications are not straight-forward.

So, some anarchist punks, such as Profane Existence, embrace lifestyle politics, but others view punk’s connection with lifestylism as fatally problematic, with the criticism that punk’s sub-cultural navel-gazing renders it ghettoized, elitist, individualist and thus incapable of engaging in ‘serious’ anarchist activism. Criticisms of anarchist punk focus on class, especially as directed from ‘pre-punk’ anarchists, and crucially, according to these criticisms, punk’s association with lifestylism sets it in opposition to (or, at best, as a distraction from) ‘proper’ anarchism.

This article will analyse and compare Class War and CrimethInc. in terms of these emerging key themes, i.e. their connections with punk and their manifestations of ‘being punk’; their iconoclastic attitudes to ‘pre-punk’ anarchists; their conceptions of class; and their positions regarding lifestylism. Analysis of just two particular groups cannot speak on behalf of a movement as wide-ranging and multifarious as anarchism (or punk), but doing so raises interesting issues, and it significantly problematizes many of the sweeping criticisms levelled at the relationship between punk and anarchism, while also undermining the basis of the workerism versus lifestylism dichotomy which persists in warping debate about strategy and tactics within the broader anarchist movement.

Punk

Class War and punk

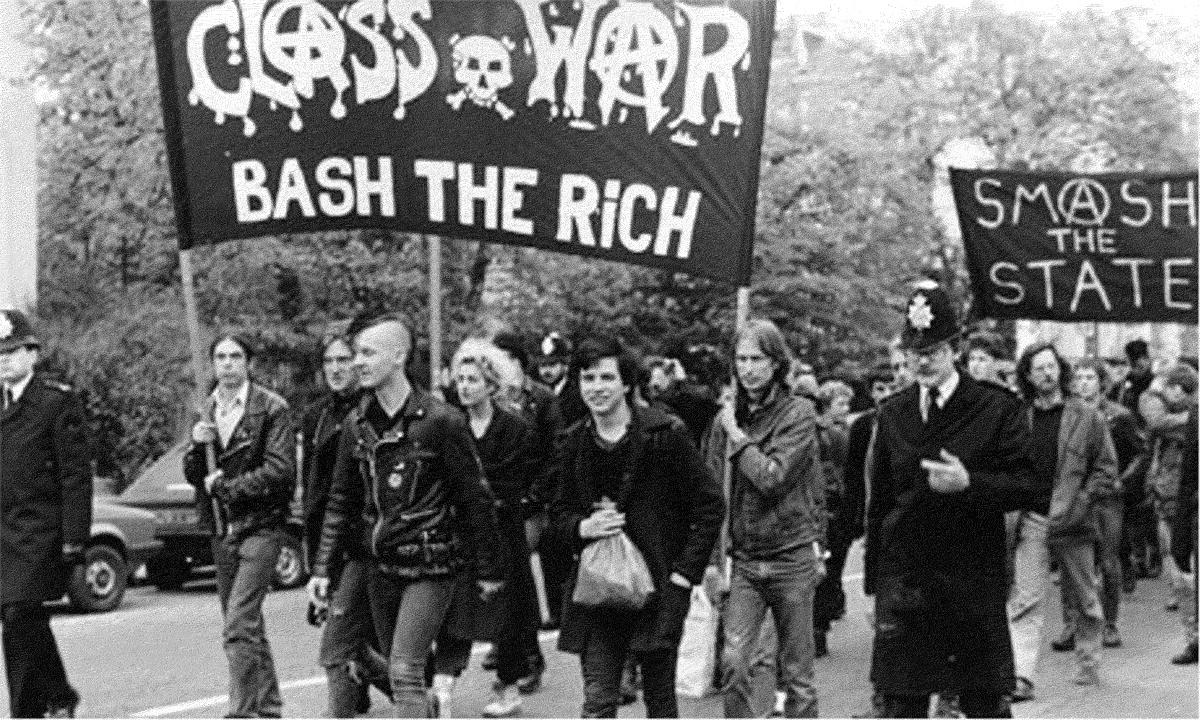

Class War are an anarchist group that emerged in the UK in the early 1980s, after the founding of the Class War newspaper by Ian Bone in 1982. Bone was inspired by the propagandistic successes of the anarcho-punk[21] band Crass and made use of a punk aesthetic to promote a more class-focussed version of anarchist politics to a newly emerging and receptive punk audience—Bone described Class War as ‘a punkoid fanzine mutated into a newspaper.’[22] Class War’s open and decentralized structure means that a wide range of perspectives fall under the Class War banner—as one former Class War Federation member put it: ‘their politics were all over the place.’[23]

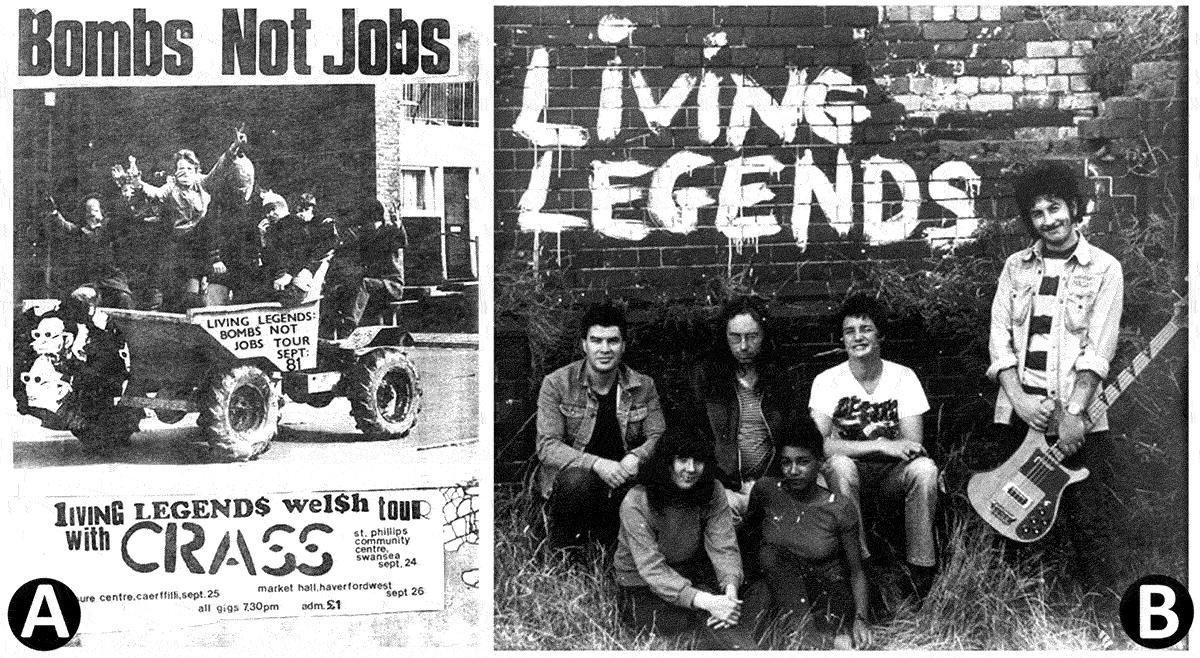

This same activist described Class War as having ‘a punky image … It combined a class politics and a kind of a spikiness … and they would accept people as punks.’[24] This punk aesthetic and attitude attracted many punks to become involved with Class War (see Figure 8). For example, Bone identifies ‘two anarcho-punks, Spike and Tim Paine,’ who were involved early on with Class War, editing issue six in early 1984, and ‘open[ing] up a squat … which served as both an anarchist bookshop and [Class War’s] contact address.’[25] Much of the membership of the Class War Federation was also populated by punks, as the aforementioned former Class War member recalled:

There were a hell of a lot of punks in the early Class War … the first conference I went to, in Manchester … in ‘86, there was a lot of kind of punky dudes there, right? There was a lot of people that had heard of Crass Records. I would say if you did a poll, everybody there would have had a Crass record at some point in their lives, maybe with the exception being Ian Bone and Martin Wright.[26]

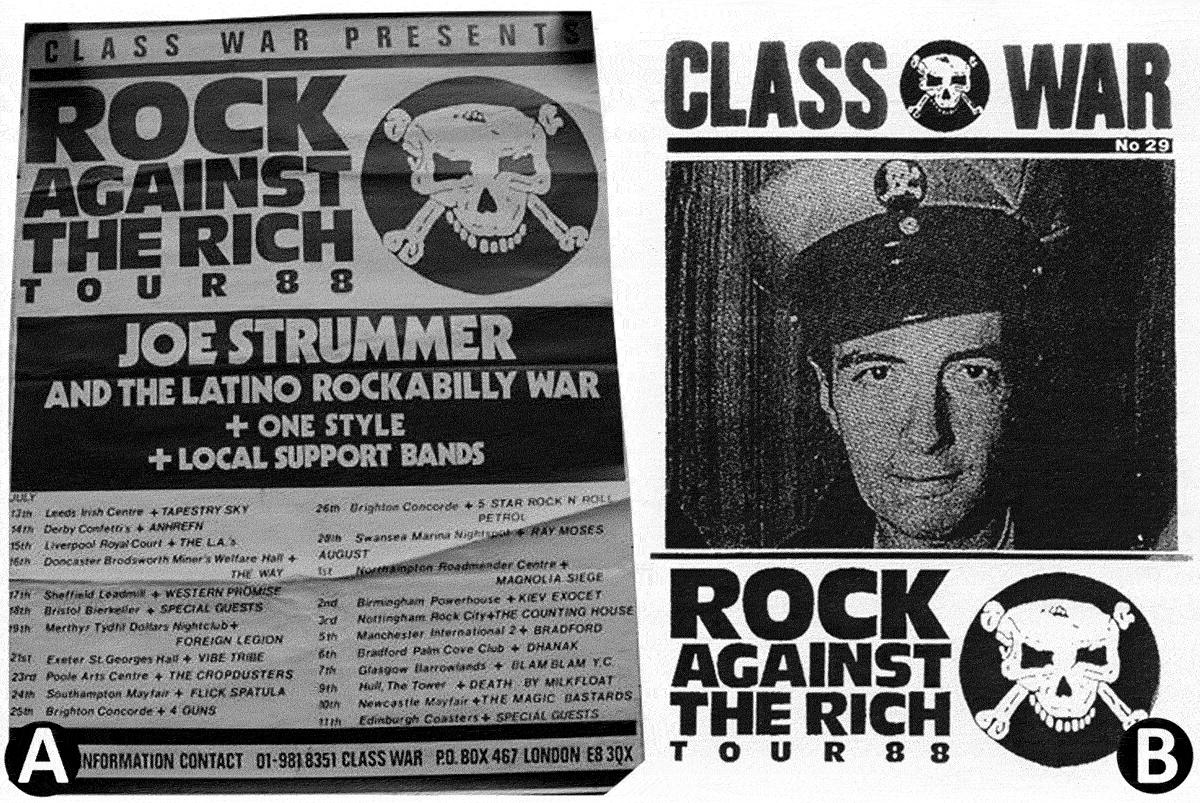

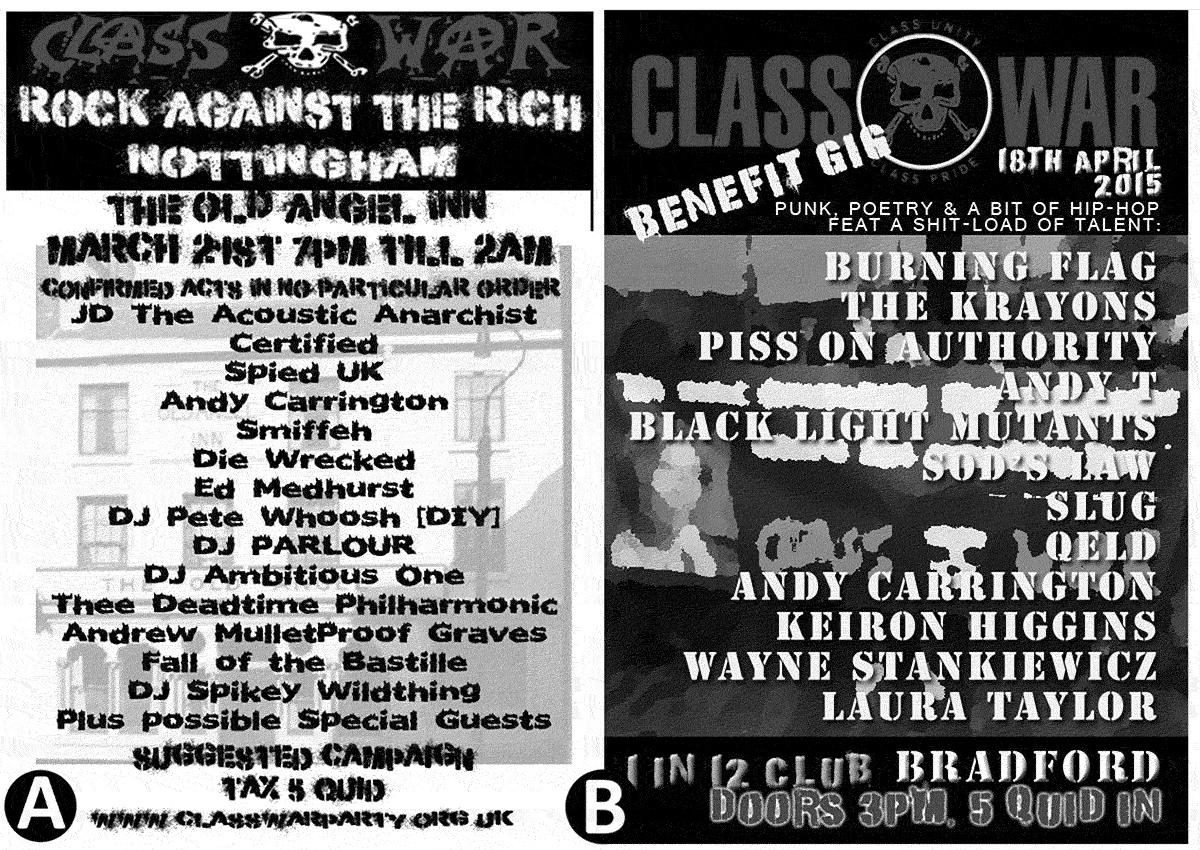

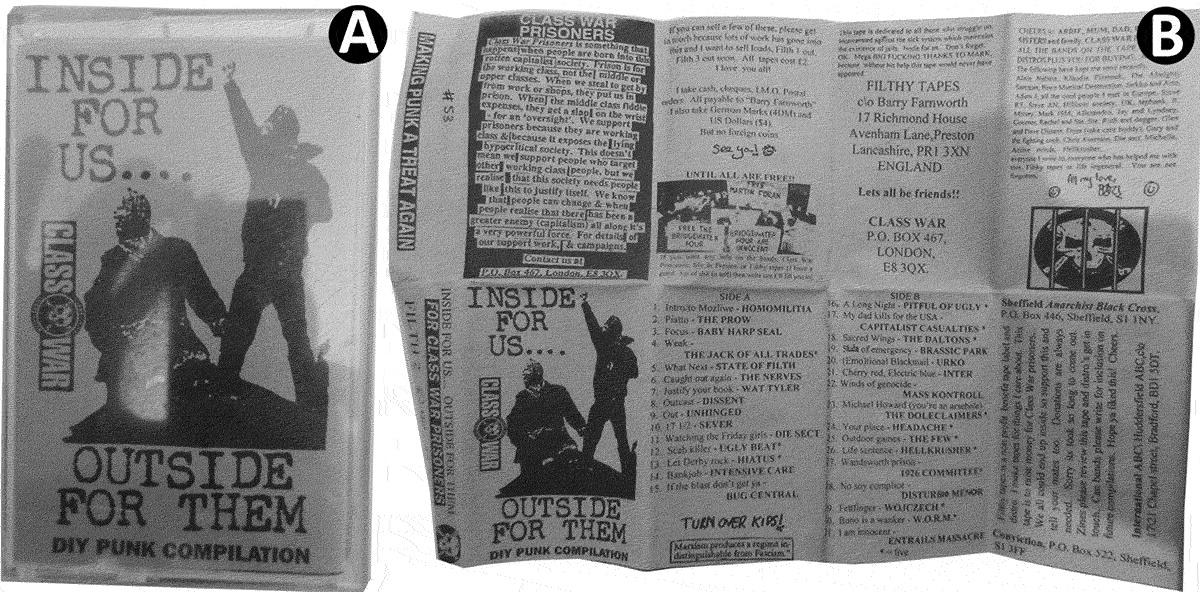

In fact, Bone played in the South Wales-based punk band Living Legends (see Figure 1), who played with Crass on numerous occasions, so he too can be considered an active (if transitory) punk participant. And indeed, Bone was explicit about the desire to attract punks, drawing on the ‘embryonic political movement’ which Crass had helped to form: ‘[f]rom the plastic As of [the Sex Pistols’] Anarchy in the UK, Crass had given the circle As real political meaning.’[27] Perhaps the most tangible connection between Class War and punk is through production and distribution of numerous punk records, cassettes and VHS compilations including, for example, the Better Dead Than Wed 7” released on Conflict’s Mortarhate label in 1986; the bootleg tape Crass—Peel Session, Interviews and Bits (undated) on Class War records; a live bootleg of Discharge titled Class War presents—Discharge live (recorded in 1981); a split double disc CD-R titled Class War by Bone’s band The Living Legends and Unit, released in 2008 on DNA Records; Inside For Us … Outside For Them tape compilation (see Figure 7), a benefit for Class War released by Filthy Tapes (undated); and the Incitement to Riot VHS compilation (undated) and a whole list of compilation albums produced and distributed by Class War activists in Australia. The Class War newspaper makes explicit references to punk throughout its issues including CD and gig reviews, and Class War’s 1988 Rock Against the Rich initiative[28] featured several punk bands including ‘ex-Clash singer Joe Strummer’[29] (see Figure 2 — the 2015 resurrection of Rock Against the Rich, for the ‘Class War Party’ campaign, also featured numerous punk bands — see Figure 3).

So Class War’s association with punk is clear, in terms of aesthetic, its membership and many of its activities. However, despite such a close association, Class War were keen to distinguish themselves from the 1980s anarcho-punk scene affiliated with Crass. Bone quotes Class War contributor Jimmy Grimes giving Crass a decidedly backhanded compliment in issue two, comparing their extensive influence to that of Peter Kropotkin. He writes:

[They] had found a way of getting anarchist political ideas through to tens of thousands of youngsters … They’d reached punters in towns, villages and estates that no other anarchist message could ever hope to reach … but like [Kropotkin] their politics are up shit creek.[30]

George McKay considers Class War’s criticism here to be rooted in Crass’s ‘refusal to situate their actions in the traditional labour framework of class opposition—presumably they are compared to Kropotkin, a one-time prince, to signal Class War’s distrust of influence through privilege.’[31] In their theoretical journal The Heavy Stuff, Class War write that they were keen ‘to break out of the anarcho-punk scene and create a real force for credible Anarchist politics,’[32] and Bone states that, in his view: ‘anarcho-punk music, far from helping the struggle, got in the way of it by diverting the punks away from street action and into the anarcho-ghetto of endless squat gigs.’[33] So, in common with the criticisms of punk (mentioned earlier), Class War view the anarcho-punk of Crass and their ilk as a distraction from ‘proper’ anarchism because of its failure to engage with class. This criticism is being made by an explicitly punk anarchist group, which significantly complicates the grounding of similar criticisms that are levelled at punk as a whole, and points to a much more nuanced (and complicated) relationship between punk and anarchism.

CrimethInc. and punk

The CrimethInc. ex-Workers’ Collective is an anarchist propaganda and activist group based in the US. They emerged from the DIY punk milieu in the 1990s and since that time have published several theory books/activist guides and 12 issues of their periodical journal Rolling Thunder (the latest in spring 2015), as well as producing numerous podcasts, blogs, zine columns, posters, stickers, pamphlets, documentaries and music releases. Numerous contributors publish under the CrimethInc. banner, and while divergent opinions and approaches are discernible, their overall political stance is generally more coherent than that of Class War, and it is possible to trace some key developments in their political positions, especially regarding class and lifestylism, through their key texts: Days of War, Nights of Love (2001),[34] Expect Resistance (2008),[35] Work (2011),[36] Contradictionary (2013).[37]

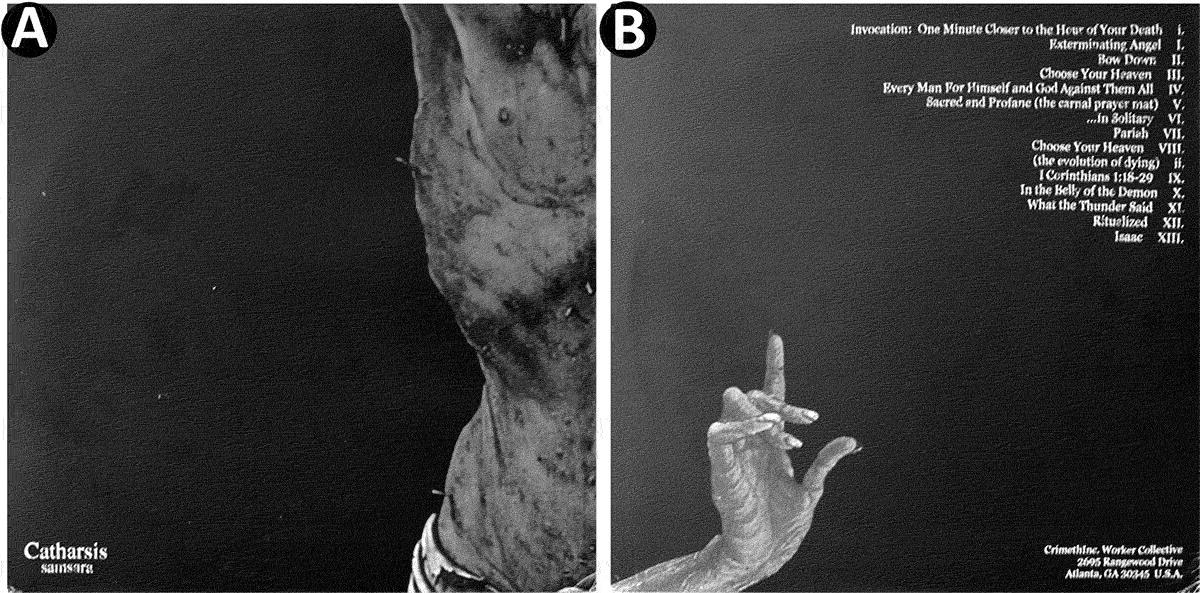

Several CrimethInc. contributors have been in prominent punk bands such as Catharsis (see Figures 5 and 6) and Zegota, and CrimethInc.’s grounding in the DIY practices of punk has a discernible influence on their aesthetic and philosophy. They also engage in outreach into punk publications, including: ‘Slug and Lettuce and Profane Existence and a column … in Maximum Rock’n’Roll.’[38] Jeppesen considers that an engagement with ‘the growing global anarchapunk community’[39] is at the root of CrimethInc.’s popularity and argues that CrimethInc. texts ‘provide a path from punk, an anti-corporate music and fashion-based subculture, to becoming activists through an engaged political philosophy.’[40]

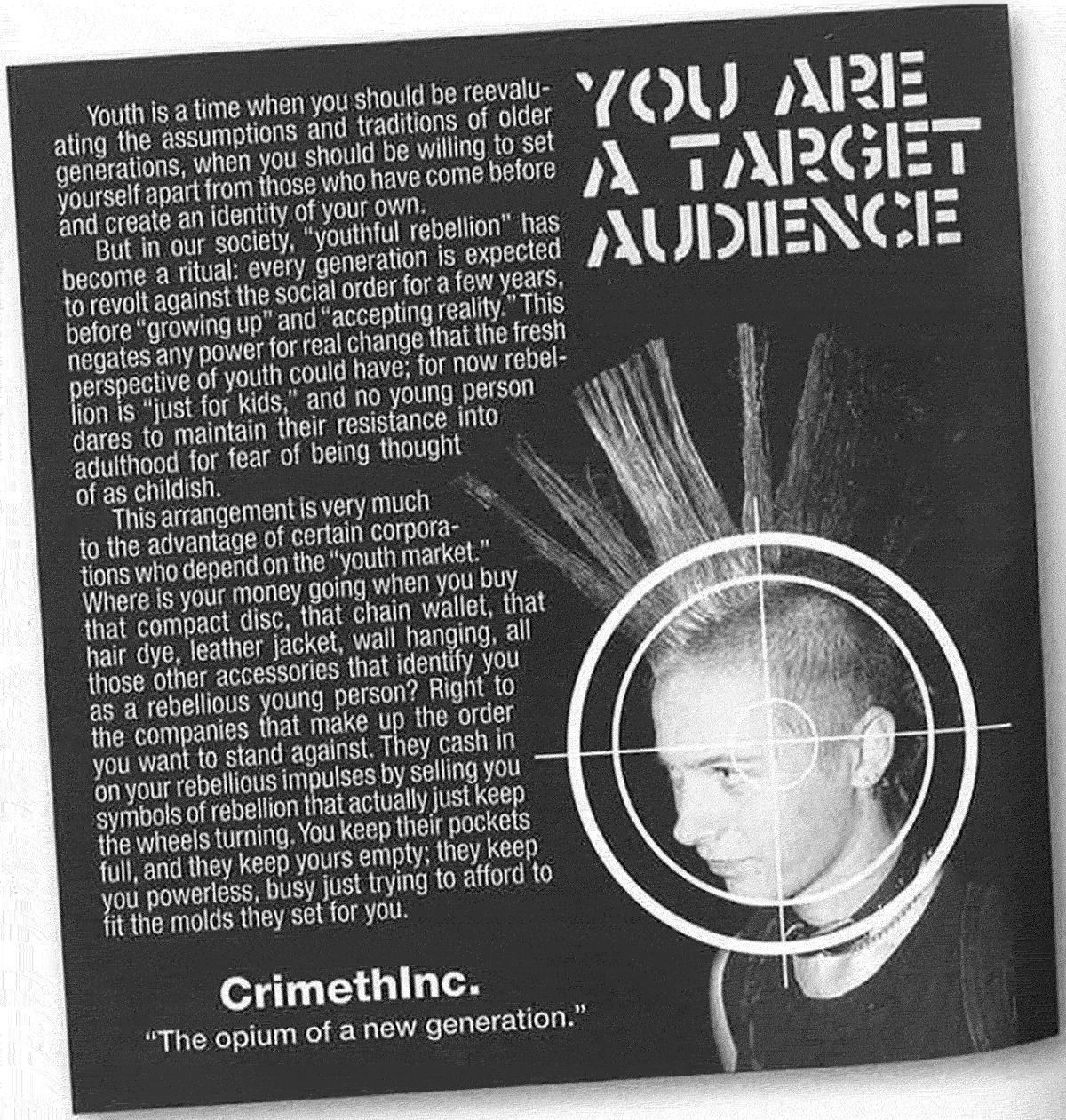

So CrimethInc. are clearly very closely associated with punk, and they embrace this relationship (almost) unequivocally (see Figure 4). In an extensive article in issue seven of Rolling Thunder, they celebrate the connections between punk and anarchism, pointing to the ‘great proportion of those currently active in anarchist circles [who] have at some point been part of the punk counterculture’[41] and suggesting that ‘there has been something intrinsically subversive about punk.’[42] Defending the relationship between punk and anarchism from its critics, CrimethInc. argue that ‘[w]ere we to attempt to invent a counterpart to contemporary activism that could replenish energy and propagate anarchist values among people, we could really do worse.’[43]

However, CrimethInc. are not wholly uncritical of punk, recognizing that ‘it is crippling for a social movement aimed at transforming the whole of life to be associated with only one subculture,’[44] and they are also conscious of the ways in which punk’s critics consider it to be (pejoratively) lifestylist, in terms of a focus on culture, consumerism and identity. But these criticisms are not considered to be fatally problematic, and in direct response to those anarchists who would dismiss punk, CrimethInc. write: ‘there’s no sense in seeking to expand the anarchist moment by rejecting one of the primary venues through which people have discovered it,’ and that punk is a ‘sustainable space that nurtures long-term communities of resistance,’ and provides ‘demonstrat[ion of] a concrete alternative.’[45]

Commenting on a draft of this article, a participant with the CrimethInc. ex-Workers’ Collective described CrimethInc. as ‘a sort of transitional project using punk strategies (media, touring, etc.) to try to address much broader audiences about the subjects that had previously been confined to subcultural circles.’[46] They identified a decline in the relationship between punk and anarchism in the US, weighing that ‘today, a minority of the anarchists we interact with have a background in punk’ but noted that the lack of engagement with ‘a vibrant arts-based element (whether punk music or any other medium)’[47] is a point of weakness in the contemporary US anarchist movement, echoing the arguments in issue seven of Rolling Thunder.

Both CrimethInc. and Class War have their roots in punk, and while both groups have a persisting association with punk, they react to this in distinctly different ways. CrimethInc. argue in defence of punk’s contribution to anarchism, while Class War express unease, even embarrassment, over punk’s association with lifestylism and attempt to recast the relationship between punk and anarchism on their own terms. So, some of the complexity of ‘punk anarchism’ is already revealed in just an introductory analysis of two ‘punk anarchist’ groups—both Class War and CrimethInc. can be understood as ‘punk’ in terms of their aesthetic, membership and activities, but their positions regarding the relationship between punk and anarchism are clearly divergent. The similarities between the ‘punk anarchisms’ of Class War and CrimethInc. do, however, extend beyond their shared punk aesthetic, membership and activity, as evident in their iconoclastic attitude to ‘pre-punk’ or ‘old guard’ anarchists.

Iconoclasm

Discussing the UK anarcho-punk scene of the early 1980s, O’Guérin writes of ‘a debate at this time between the emerging anarchist punk philosophy and traditional class struggle anarchists.’[48] This understanding of ‘pre-punk’ or ‘old-guard’ anarchists struggling to come to terms with a new expression of anarchist politics is echoed by Richard Porton, who recalls a ‘conversation with the long-time anarcho-syndicalist Sam Dolgoff, who worried that kids compelled [by punk] to draw circled “As” on the sides of building [sic] knew little about anarchist history or theory.’[49]

The old guard’s dubious impression of punk is more than reciprocated by Class War and CrimethInc. For example, Class War founder Ian Bone recalls his negative impression of the anarchist movement in the UK of the 1980s, paraphrasing Raoul Vaneigem:[50]

‘[T]hose who make a revolution without explicit reference to everyday life speak with a corpse in their mouths.’ But the anarchists did speak with corpses in their mouths—usually Spanish or Ukrainian—and their papers seemed to have no connection with the ordinary lives of anyone.[51]

Bone derides the commonplace anarchist preoccupation with historic episodes such as the Spanish Revolution and Civil War (1936–1939) and the Makhnovist Revolution in Ukraine (1917–1921) and describes attendees at a Black Flag conference as ‘deadwood CNT[52] worshippers and armchair-armed struggle fetishists’[53] and blasts the longstanding anarchist publication Freedom[54] as ‘a fucking boring, awful liberal irrelevance of a newspaper.’[55] This is echoed (with less fiery panache) in The Heavy Stuff issue one, when Class War ask: ‘How much longer are we going to be content to base our politics around ideas and actions that were formulated nearly 100 years ago?’[56] This iconoclasm is a continuous thread in Class War’s publications, with a 2012 pamphlet published by ‘The Friends of Class War’ rearticulating a similar argument in a more contemporary context:

What is certain is that existing efforts are not enough; the organisations there are at times are embarrassing with a precious view of themselves, and are not up to the political situation as they have a complete lack of dynamism and ambition, unable to develop beyond stereotypical forms and existing practices, which have never delivered progress … You’ve had opportunities for years to do something, anything even, and blown it.[57]

A late-1980s issue of Class War states: ‘[w]e reject the boring character of the so-called “revolutionary” groups. Politics must be fun, it’s part of ordinary day to day life and must be able to take the piss out of itself!’[58] Class War’s criticism of the ‘old guard’ anarchists as being precious, transfixed by historical preoccupations, boring and irrelevant is echoed very strongly in CrimethInc.’s writing. For example:

today’s radical thinkers and activists … often seem mired in ancient methods and arguments, unable to apprehend what is needed in the present to make things happen. Their place in the tradition of struggle has trapped them in a losing battle, defending positions long useless and outmoded: their constant references to the past not only render them incomprehensible to others, but also prevent them from referencing what is going on around them.[59]

And even more emphatically:

FACE IT, YOUR POLITICS ARE BORING AS FUCK … You know it’s true. Otherwise, why does everyone cringe when you say the word [anarchism]? Why has attendance at your anarcho-communist theory discussion group meetings fallen to an all-time low? Why has the oppressed proletariat not come to its senses and joined you in your fight for world liberation? … The truth is, your politics are boring to them because they really are irrelevant.[60]

In particular, CrimethInc.’s accusation that ‘pre-punk’ anarchists are boring is a point of uncanny similarity to Class War’s criticisms—and boredom is a prominent trope in punk as well, particularly in the ‘early punk’ of the mid-to-late 1970s.[61] Indeed, the iconoclasm expressed by both Class War and CrimethInc. has a distinctly ‘punk’ ring to it, with the ‘old guard’ anarchists being berated in much the same way as were punk’s musical and cultural forebears. The Situationists are another key influence here (Vaneigem has already been mentioned earlier), and both Class War and CrimethInc. draw on the Situationists’ focus on cultural struggle and rejection of reformist political strategies.[62]

However, the targets of this punk anarchist iconoclasm are not identical—unlike Class War, CrimethInc. also focus their ire on class struggle anarchists, writing, for example: ‘However much theorists of class war might like to see themselves as the voice of the common people, nowadays they are a more obscure demographic than the dropouts they despise.’[63] This is from an early issue of Rolling Thunder written after the publication of Days of War, Nights of Love in apparent response to the subsequent tide of criticism of CrimethInc. as ‘arch-lifestylists’—this is evident in the terminology: they defend the lifestylist tactic of ‘dropping out’ and attack the workerist emphasis on class struggle. Attitude to class is a key difference between CrimethInc. and Class War, which will be explored in more detail later.

In 1997, the main body of Class War Federation decided to dissolve the organization[64] and published a special issue of Class War (number 73) to analyse their successes and failures. In it, they specifically address their iconoclastic approach to the ‘old guard’ anarchists:

Class War has always been rightly paranoid about ending up like the left parties and sects, defending particular unchanging theoretical positions and traditions, regardless of how much things have changed since 1917 or 1936. We set out to avoid this, but fell into another trap—defending a rebellious ‘attitude’ and ‘image,’ rather than looking at what’s wrong with the world and how we can best intervene to change it. In many respects it’s true to say that Class War failed to become much more than a ‘punk’ organisation.[65]

The authors still identify the ‘old guard’ anarchists’ historic focus on 1917 (Ukraine) and 1936 (Spain) as a ‘trap’ of irrelevance, but they also consider the group’s association with punk to be fatally detrimental, in much the same terms as detailed in the criticisms of punk earlier, and in sharp contrast to CrimethInc.’s consideration of their own relationship to punk. (Though it must be noted that the continuing iterations of Class War have largely retained an association with punk.)

Even in this iconoclasm, where a shared sense of ‘punk anarchism’ might be most strongly identified, some crucial differences open up between Class War and CrimethInc., especially around class.

Class

Class War and classism

Despite their grounding in punk, Class War were at pains to distinguish themselves from Crass’s brand of ‘peace punk’ anarchism. This was most simply achieved by advocating violence (exemplified in their iconic page three splashes of ‘Hospitalised Coppers’) but also by placing class at the centre of their politics. Ramsay Kanaan, singer with anarchist punk band Political Asylum and co-founder of AK Press and subsequently PM Press, argues that Crass were ‘very middle-class’:

Other than joining the peace movement, Crass did not talk about class and were very anti-class: ‘Left wing, right wing, it’s a load of shit. Middle-class, working-class, I don’t give a shit.’—probably because Crass were mostly middle-class, of course.[66]

This absence of class analysis, Kanaan argues, results in ‘individualistic instead of collective actions to change society’[67] and is therefore not ‘proper’ anarchism. This echoes the workerist caricature, which vaunts the working class but also emphasizes the inherently counter-revolutionary nature of the ruling class and the middle class. Echoing Lucy Parsons’ famous quote,[68] an early issue of Class War newspaper states:

the ruling class will never give up its stolen, spoilt lives. It will never give away its power unless we violently take it as a class. The only language the ruling class and its paid mercenaries the cops and army, understand is that of class violence. WE FIGHT FOR A WORKING CLASS REVOLUTION.[69]

Strongly reflecting the workerist caricature, Class War identify the working class as ‘the only people capable of destroying capitalism and the State, and building a better world for everyone.’[70] The working class is defined as:

people who live by their labour … the ownership of property that generates wealth is the dividing line. If you have enough property or money not to have to work then you are not working class. The other component of class identity is ‘social power.’ The working classes do not have power.[71]

This definition is quite broad[72] and inevitably includes a large number of people who would describe themselves as middle class, despite not owning wealth-generating property or having ‘social power’ (and conversely, their definition of middle class includes many traditionally working-class occupations). As such, class consciousness is of key importance, but this is expressed, not as a critique of social relations, but as an identity politics—as classism. The views of Andy Anderson (a contributor to Class War Federation’s publications) are interesting in this regard since he considers that the whole middle class is irrevocably implicated in the perpetuation of capitalist society and that the anarchist movement too is sullied by association with the middle class (suffering, he writes, from a fundamental ‘class corruption’ because Kropotkin was a prince and Bakunin was middle class[73]). Anderson also vaunts a particular type of ‘working class behaviour’ and as a result rejects any possibility of class-mobility since even those few working-class people who sometimes find their way into middle-class occupations ‘almost always still behave like working class people.’[74] This expression of class as an identity politics (implicitly) contradicts conceptions of class based on economic relationships—and actually stands in direct opposition to the materialist economic analysis which also typifies the workerist caricature and which Class War also express. This confusion around class is symptomatic of the fundamental baselessness of the workerist caricature.

Class War’s views on class are not always so crudely classist, however. In their theoretical journal, The Heavy Stuff, they argue that ‘the emphasis has shifted from the workplace to the community, as the focal point for class struggle,’[75] which is pointedly distinct from the workerist caricature in terms of the site of struggle (even while the agent of revolution remains as the working class). In issue 73 of Class War (the ‘final issue’), they write that they suspect it is not possible ‘to make a revolution in which only working class people participate … [or] to create a purely working class organisation.’[76] The problem essentially boils down to an impassable difficulty in actually defining who is working class and who is not: ‘how do you determine who is allowed to get involved? Do you have a class-based means test or is it down to intuition? What about the numerous grey areas?’[77] This is clearly a significant departure from the reductive concept of class espoused in some Class War publications, and especially by Anderson—but, even with this qualification, Class War do not abandon their core focus on class: ‘This doesn’t mean that we don’t know who the enemy is.’[78] These excerpts from The Heavy Stuff and Class War issue 73 are fairly exceptional in their challenging of the reductive class concepts and classism expressed elsewhere, and it might be generally stated that Class War’s analysis basically correlates with that of the workerist caricature (including the contradictions that are entailed in that). Commenting on a draft version of this article, Jon Bigger,[79] who is involved with Class War, agreed that ‘the confusion around class is symptomatic of the baselessness of the workerist caricature’ but he extends this baselessness to argue that the apparent contradiction of viewing class as a system and ‘as a culture/consciousness’ is actually a reflection of the top-down imposition of class concepts which are essentially ‘unreal and arbitrary.’ He argues that there is a ‘dominant cultural view that class is measurable and something set down via occupation’ which Class War’s analyses lapse into ‘because systemic examples dominate our understanding,’ ‘but [Class War] also fight [against that dominant view of class] by focussing on class cultural identification.’ Bigger asserts that the ‘modern’ Class War position on class is quite clear: ‘you’re part of the group if you come to an action and hold the banner. The emphasis is on action in solidarity, leading to political belonging … It is solidaristic struggle that cements your conscious class position.’

So, aspects of the workerist caricature are evident in Class War’s writings, albeit in complex and conflicting ways (and as Bigger points out, this arguably says more about the arbitrary top-down imposition of class categories than it does about the consistency of Class War’s analyses). In any case, this fundamentally challenges the understanding of punk anarchism as unabashedly lifestylist.

CrimethInc. and the déclassé

CrimethInc.’s position is very distinct in this regard and, as discussed earlier, CrimethInc. also include class struggle anarchists in their dismissal of ‘old guard’ anarchism. As may be noted from the references in this particular section, most of their engagement with class analysis emerges in more recent publications such as Work (2011) and Contradictionary (2013), while earlier texts only address class politics in passing and usually dismissively or even to explicitly counter a focus on class.

Jeppesen highlights the criticism that CrimethInc. ‘are often considered “lifestyle anarchists” who have no self-awareness of their class privilege.’[80] CrimethInc. argue against workerist conceptions of class, viewing it as a social categorization that is to be resisted, rather than as a revolutionarily significant social relation or identity. CrimethInc. highlight classism as particularly problematic, writing that ‘fixation on the working class can promote a sort of class-based identity politics—even though class is not an identity, but a relationship’[81] and that ‘some activists focus on “classism” rather than capitalism, as if the poor were simply a social group and bias against them a bigger problem than the structures that produce poverty.’[82] They argue against vaunting the working class as a revolutionary subject, using Marxist terminology (critically) to state that this ‘fosters a determinism that objectifies human beings and revolutionary struggle while avoiding the complexities of reality.’[83] They even defend the middle class against workerist opprobrium, writing: ‘[t]here’s no moral high ground in capitalism: it’s not more ethical to be further down the pyramid. Trying to appease your conscience isn’t likely to do anyone else a lot of good.’[84] CrimethInc. argue that contemporary dynamics of capitalist society mean class-based organizing is ‘outflanked and out-moded’ and argue that ‘Anticapitalists are still casting around for new forms of resistance that could take the place of the union and the strike,’[85] implying that those who cling to the ‘old’ workplace-based methods are no longer effectively countering capitalism at all. And, in a clear statement of their opposition to workerism, they assert that ‘[a]nybody who wants to change the subject back to the proletariat once the issue of domination itself has been broached is not a comrade.’[86]

When CrimethInc. do talk about class, it is very distinct from Class War’s position—Jeppesen considers that CrimethInc. ‘both reject and exploit their own class privilege’[87] and argues that CrimethInc.’s main political point is that: ‘if we want to overthrow that system, we need to renounce our [middle class] privilege and become class traitors.’[88] In this vein, CrimethInc. assert that:

We have to supersede our current roles and identities, reinventing ourselves and our interests through the process of resistance. We shouldn’t base our solidarity on shared attributes or social positions, but on a shared refusal of our roles in the economy.[89]

This ‘déclassé’ position[90] is significant, echoing arguments made by Joel, ‘columnist for the Punk-anarchist fanzine’ Profane Existence, who explicates a ‘class traitor’ position within the US punk scene, along with an intersectional analysis:

We are the inheritors of the white supremacist, patriarchal, capitalist world order. A prime position as defenders of the capital of the ruling class and the overseers of the underclass has been set aside for us by our parents, our upbringing, our culture, our history, and yet we have the moral gumption to reject it. As Punks we reject our inherited race and class positions because we know they are bullshit.[91]

This is clearly in sharp distinction to the workerist caricature and, indeed, very different to Class War. Jeppesen notes that this:

political choice of ‘declassing’ … has been critiqued as a choice that only middle-class kids have, but people involved in CrimethInc. come from a range of classes, and the strategies they suggest … work equally well and are actually more important for people who have no money, as anti-poverty survival mechanisms.[92]

However, this position is somewhat complicated by a discussion of class consciousness in Work that could comfortably sit within any Class War publication. CrimethInc. write that debt

makes it possible for low-income workers to partake in the lifestyles of the wealthy, buying houses and cars and college degrees. This serves to make people see themselves as middle class even as they are fleeced by banks and credit card companies[93]

and ‘[t]hus,’ they argue, ‘a whole class never identifies with its role or demands better treatment.’[94] This sort of class-analysis is fairly anomalous, and this one section of writing does not recast CrimethInc. as class struggle anarchists—but it does perhaps represent an interesting development in CrimethInc.’s politics.

CrimethInc.’s engagement with class only really emerges in their more recent writing, and even then, it is distinct from workerist class analysis and classism—the fleeting moments where CrimethInc.’s position on class overlaps with Class War’s are basically exceptions, which only serve to highlight the overall distinction between the two groups in this regard. Several of those who commented on a draft version of this article pointed to the distinct contexts of the UK and the USA, especially in terms of class, as a main reason behind the divergent approaches of Class War and CrimethInc. Chris Low, a long-time associate of Class War, wrote that because of ‘fundamental differences in … class structure and perception, the idea of … class (self) reinvention/revisionism is harder to achieve’ in the UK than in the USA. A participant in the CrimethInc. ex-Workers’ Collective also highlighted the ‘cultural difference between Britain and the US,’ especially in terms of traditions of class struggle, noting that:

while in the UK, belligerently identifying with the working class might situate you advantageously to get the ear of (other) workers, in the US, it often has precisely the opposite effect. From the beginning, we responded to this particular context by setting out to undermine the idea that middle-class privilege had anything of value to offer … draining middle-class status of its appeal was essential for establishing a point of departure for any kind of struggle in the first place.[95]

So, in both contexts, entrenched views of class (or class aspiration) stand in the way of a déclassé consciousness, but the class-attachments in each context are clearly distinct, and this has a bearing on the class analyses and strategies of Class War and CrimethInc.

Lifestylism

CrimethInc.’s lifestylism (and their anti-lifestylist detractors)

CrimethInc.’s labelling as lifestylists is based on their prominent focus on revolutionary personalism and cultural activism. In a typical example, CrimethInc. argue that ‘[w]e should put the anarchist ideal—no masters, no slaves—into effect in our daily lives however we can,’[96] and they assert that a personal focus is pre-eminent:

If we are to transform ourselves, we must transform the world—but to begin reconstructing the world, we must reconstruct ourselves … Our appetites and attitudes and roles have all been moulded by this world that turns us against ourselves and each other. How can we take and share control of our lives … when we’ve spent those lives being conditioned to do the opposite?[97]

CrimethInc. argue that ‘[a]ny kind of capital-R Revolution … will be short-lived and irrelevant without a fundamental change in our relationships’[98]—revolutionary philosophies or actions lacking this ‘lifestylist’ consideration are fundamentally flawed, in this view. CrimethInc. are highly concerned with consumption and consumerism, particularly in terms of a refusal of bourgeois capitalist culture. This is termed as ‘dropping out’ which CrimethInc. define as: ‘ceasing to make purchases, reducing your needs, and finding other sources for what you require.’[99] This is not argued to be an end in itself, but rather as ‘a point of departure for revolutionary struggle.’[100]

CrimethInc.’s emphasis on personalistic revolution as a prerequisite for any significant social change closely reflects the lifestylist caricature, and this has been the main focus for the criticism, and often outright ire, directed at them. Many of these attacks are framed explicitly in terms of the supposed ‘lifestylist’ versus ‘workerist’ dichotomy and often specifically include associations with punk as part of their denigrations. Some examples are to found on the websites anarkismo.net (which identifies itself as anarcho-communist and platformist[101]) and libcom.org (an abbreviation of ‘libertarian communist’ listing influences as ‘anarchist-communism, anarcho-syndicalism, the ultra-left, left communism, libertarian Marxism, council communism’[102]). One anarkismo.net contributor, writing under the pseudonym ‘W,’ writes:

Your politics are bourgeois as fuck … Crimethinc substitute … class struggle with a teenage individualistic rebellion based on having fun now. Shoplifting, dumpster diving, quitting work are all put forward as revolutionary ways to live outside the system but amount to nothing more than a parasitic way of life which depends on capitalism without providing any real challenge … Condescending, privileged, middle class crap.[103]

An article on libcom.org by ‘Ramor Ryan’ takes a similar tone:

CrimethInc begins with the brand name, and ends with the relentless merchandising of ‘radical’ products on their website. In between there is, as exhibited by this book [Days of War, Nights of Love], an individualist, selfish, and inchoate rebel ideology that eschews work, political organising, and class struggle.[104]

AK Thompson understatedly notes that ‘the CrimethInc Ex-Workers Collective … [are] not universally loved,’[105] quoting W’s ‘scathing article,’ which was widely circulated online:

The US based sub-cultural cult ‘Crimethinc’ (CWC) who mix anarchism with bohemian drop-out lifestyles and vague anti-civilisation sentiment would have you believe that capitalism is something from which you can merely remove yourself by quitting work, eating from bins and doing whatever ‘feels good.’[106]

Ramor Ryan’s libcom.org article raises the punk ‘accusation’:

CrimethInc’s vision seldom rises above that of a suburban kid rebelling against authority. Mired in the punk rock and crusty sub-culture, the practical application of all this revolutionary theory is apparently realised by forming a band, fucking in a park, going vegan … [they are] dull and inchoate.[107]

‘W’ even goes as far as to say that CrimethInc.’s Furious George Collective ‘each deserve a bullet for crimes against anarchism’[108] for their Anarchy in the Age of Dinosaurs book. It must be assumed that “W” is not seriously suggesting that anyone be murdered, but the vitriol of the criticisms levelled against CrimethInc. is clear. The articles from the libcom.org and anarkismo.net websites attack CrimethInc. as middle class, bourgeois, individualist and elitist and point explicitly to CrimethInc.’s dismissal of class struggle and association with punk to argue that CrimethInc. represent a fatally corrupted interpretation of anarchism which redirects energy away from useful revolutionary activity, and they are, as such, considered to be worse than useless by their workerist detractors.[109] The terms of these criticisms echo those made of punk, and the pointedly pejorative accusation behind the ‘lifestylist’ label is made very apparent (see Figure 9).

Class War’s anti-lifestylism (and their lifestylist tendencies)

Class War are early adherents of ‘anti-lifestylist’ rhetoric—ten years prior to Murray Bookchin’s Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism:An Unbridgeable Chasm,[110] an issue of Class War (c. April 1985) carried an article bemoaning ‘groups of “life-stylers“ [as] … patronising or abusing working class values’[111] and in a similar vein the founding statement of the Class War Federation in 1986 states:

Now is the time for Class War anarchists and all who agree with class struggle politics to break away from the ghetto of dropouts, drugs and hippy attitudes. There is no place for anarchism in the working class till it can offer something better than free festivals and political fanzines.[112]

Even Class War issue 73, which displays a conciliatory approach in most other regards, writes that ‘Class War came into being with the aim of sticking the boot into anarcho-pacifism and lifestyle politics.’[113] Class War argue that lifestylism romanticizes poverty, and particularly attack dropping out, writing that ‘[t]his strange behaviour is usually accompanied by the use of hard drugs and right-wing individualism hiding behind the label of “anarchism.”’[114] So Class War perceive lifestylism as being in opposition to anarchism, even to the extent of being denigrated as right wing, and this opposition to ‘hippy’ lifestylism is rolled-in with derision for the middle class as well (for example: ‘a ragged-arsed bare foot hippy from the middle class on the dole is still middle class’[115]).

This anti-lifestylist rhetoric foreshadows the terms of criticism levelled against CrimethInc.—but even so, there are threads within Class War’s writing that could correlate very closely with CrimethInc.’s personalistic and cultural focus. For example, from Unfinished Business:

Fundamentally this is about bringing politics into all areas of peoples [sic] lives … [C]apitalists invade every area of our lives, in turn the working class have to retrieve every part of their lives … This development becomes the foundation and energy behind any possible revolutionary movement.[116]

There is a clear emphasis on ‘revolutionary personalism’[117] here, even to the extent of describing it as the foundation of revolution. Class War seem to straddle directly conflicting positions in their simultaneous rejection and embrace of lifestylism. However, rather than identify hypocrisy, this, in fact, points to the misuse or mislabelling of lifestylism. They identify a narrow subcultural aesthetic as ‘lifestylism’ and reject it on those grounds, while actually arguing in favour of quintessentially lifestylist political approaches—which, as Laurence Davis[118] points out, is exactly what Bookchin does in his own influential anti-lifestylist rant.

Class War propagate anti-lifestylist rhetoric while emphasizing revolutionary personalism and cultural activism, framing these in terms of working-class identity (not necessarily classism) and working-class culture. Even though the class framing clearly distinguishes them from CrimethInc., Class War argue for the same revolutionary mechanisms which typify the lifestylist caricature. Again, this points to the baselessness of the lifestylist caricature, rather than hypocrisy on Class War’s part—and this is all the more poignant in light of Class War’s anti-lifestylist rhetoric and their association with punk.

Conclusion

Class War and CrimethInc. are chiefly identified here as ‘punk anarchists’ because of their roots in the punk scene, their involvement in punk cultural production, their punk aesthetic and the punk membership of their groups—they might both, then, be described as being situated within (or adjacent to) punk culture. Beyond being ‘punk-situated,’ Class War and CrimethInc. have very distinct emphases—they share an iconoclastic attitude to the ‘old guard’ of the anarchist movement (which in itself has a distinctly punk ring to it), but they have contradicting emphases with regard to class and lifestylism. On the surface, this distinction serves to undermine criticisms of ‘punk anarchism’ as being lifestylist, which is reinforced by Class War’s own anti-lifestylist rhetoric. However, on closer inspection, Class War can be identified as sharing CrimethInc.’s emphasis on revolutionary personalism and culturally focussed activism (even to the point of framing revolutionary personalism as being pre-eminent to other arenas of struggle)—and these are key tenets of lifestylism. This is not to say that Class War are closet lifestylists or that lifestylism is, after all, the identifiable characteristic of punk anarchism—rather, it highlights the fundamental emptiness of the ‘lifestylist’ versus ‘workerist’ dichotomy. The caricature straw figures of ‘lifestylist’ and ‘workerist’ disintegrate in examination of actually existing anarchism, and it becomes apparent that anarchist activists and groups simultaneously occupy a range of positions across a spectrum between the false poles of ‘lifestylist’ and ‘workerist.’

So, rather than argue that critics of punk anarchism are wrong to identify it as lifestylist, this article argues that they are wrong-headed in seeking to apply a rigid dichotomous framework to entities as multifarious and nuanced as punk and anarchism. An anarchistic reading of the complex relationship between punk and anarchism can be framed in Proudhon’s deployment of Kant’s concept of antinomy, which allows for an embrace of antagonisms and tensions while still enabling meaningful analysis. Proudhon describes the concept of antinomy as the ‘plurality of elements, the struggle of elements, the opposition of contraries,’[119] or as Nicolas Walter puts it: ‘This tension is never resolved.’[120] An antinomous understanding avoids misleading simplifications of punk or anarchism. Steven Duncombe, when questioned by Roger Sabin about the ‘confused picture’ that punk often presents, replied: ‘We revel in that confusion!’[121] This is the only useful approach for analysis of punk. Any attempt to smooth over this confusion, or impose rigid frameworks, results in skewed and dishonest reflections of punk—and this has very often been the case. Henri De Lubac notes that ‘[w]ith Proudhon the debate is never closed.’[122] Likewise, this article does not aim to close down debate, it aims to open up and explore the relationships between punk and anarchism, rather than become bogged-down in fruitless attempts to define either.

Acknowledgements

This article has benefitted from review by Benjamin Franks, Matthew Worley, Laurence Davis, Jon Bigger, Chris Low and a participant in the CrimethInc. ex-Workers’ Collective, as well as two anonymous reviewers on behalf of the Journal of Political Ideologies. The author thanks all of them for their comments. The author also thanks the Sparrow’s Nest library and archive in Nottingham for their warm hospitality and access to their extensive collection of Class War.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

[1] See Jim Donaghey, ‘Bakunin Brand Vodka: An exploration into Anarchist-Punk and Punk-Anarchism,’ Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies, 1 (2014), pp. 138–170.

[2] See Kevin Dunn, Global Punk: Resistance and Rebellion in Everyday Life (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2016).

[3] See: Caroline K. Kaltefleiter, ‘Anarchy girl style now. Riot Grrrl actions and practices,’ in Randall Amster, Abraham DeLeon, Luis A. Fernandez, Anthony J. Nocella II, Deric Shannon (Eds), Contemporary Anarchist Studies (London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 224–235; Ben Holtzman, Craig Hughes, Kevin Van Meter, ‘Do it yourself … and the movement beyond capitalism,’ in Erika Biddle, Stevphen Shukaitis, David Graeber (Eds), Constituent Imagination: Militant Investigations//Collective Theorization (Edinburgh: AK Press, 2007), pp. 44–61; Ian Glasper, The Day the Country Died. A History of Anarcho-Punk 1980–1984 (London: Cherry Red, 2006); George McKay, Senseless Acts of Beauty: Cultures of Resistance Since the Sixties (London: Verso, 1996); George McKay (Ed.), DiY Culture: Party & Protest in Nineties Britain (London: Verso, 1998); Alan O’Connor, ‘Anarcho-Punk: Local scenes and international networks,’ Anarchist Studies, vol. 11, no. 2, (2003), pp. 111–21; Alan O’Connor, Punk Record Labels and the Struggle for Autonomy: The Emergence of DIY (Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2008); Daniel O’Guérin, ‘What’s in (A) song? An introduction to libertarian music,’ in Daniel O’Guérin (Ed.), Arena Three: Anarchism in Music (Hastings: ChristieBooks, 2012), pp. 3–22; Craig O’Hara, The Philosophy of Punk: More than noise! (Edinburgh: AK Press, 1999); Scott M. X. Turner, ‘Maximising Rock and Roll: Tim Yohannan interview,’ in Ron Sakolsky and Fred Wei-han Ho (Eds), Sounding Off! Music as Subversion/Resistance/Revolution (New York: Autonomedia, 1995), pp. 180–194; Steven Taylor, False Prophet. Fieldnotes from the Punk Underground (Middletown Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2003); Stacy Thompson, Punk Productions. Unfinished business (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2004); Michelle Liptrot, ‘“Punk belongs to the punx, not the business men!” British DIY punk as a form of cultural resistance,’ in Matt Worley (Ed.) (The Subcultures Network), Fight Back: Punk, Politics and Resistance (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015), pp. 232–251; Sean Martin-Iverson, The Politics of Cultural Production in the DIY Hardcore Scene in Bandung, Indonesia, PhD thesis, (University of Western Australia, 2011); Rich Cross, ‘The Hippies now wear black: Crass and anarcho-punk, 1977–1984ʹ, Socialist History, no. 26, (2004), pp. 25–44; Kevin Dunn, ‘Anarcho-punk and resistance in everyday life,’ Punk & Post-Punk, vol. 1, no. 2, (2012), pp. 201–218; Roy Wallace (Dir.), The Day the Country Died: A History of Anarcho Punk, (2007).

[4] See Laura Portwood-Stacer, Lifestyle Politics and Radical Activism (New York/London: Bloomsbury, 2013); Claudio Cattaneo and Enrique Tudela, ‘¡El Carrer Es Nostre! The Autonomous Movement in Barcelona, 1980–2012ʹ, in Bart van der Steen, Ask Katzeff, Leendert van Hoogenhuijze (Eds), The City Is Ours. Squatting and Autonomous Movements in Europe from the 1970s to the Present (Oakland: PM Press, 2014), pp. 95–130; Grzegorz Piotrowski, ‘Squatting in the East: The Rozbrat Squat in Poland, 1994–2012ʹ, in van der Steen, Katzeff, van Hoogenhuijze (Eds), The City Is Ours. op. cit., Ref. 3, pp. 233–254; Sandra Jeppesen, ‘The DIY post-punk post-situationist politics of CrimethInc.,’ Anarchist Studies, vol. 19, no. 1, (2011), pp. 23–55; Jim Donaghey, Punk and Anarchism. UK, Indonesia, Poland, PhD thesis, (Loughborough University, 2016); Jesse Cohn, Underground Passages. Anarchist Resistance Culture, 1848–2011 (Edinburgh: AK Press, 2014); Benjamin Steinhardt Case, Bridging the Chasms: Contemporary Anarchists in the US, MA thesis, (University of Pittsburgh, 2015).

[5] See Erik Forman, ‘Revolt in Fast Food Nation: The Wobblies Take on Jimmy John’s,’ in Immanuel Ness (Ed.), New Forms of Worker Organization: The Syndicalist and Autonomist Restoration of Class-Struggle Unionism (Oakland: PM Press, 2014), pp. 205–232.

[6] For example, Smith and Worley write that ‘[e]arly editions of the Direct Action newspaper [organ of the Direct Action Movement (DAM) formed in 1979] had an irreverent style and the cut-and-paste design motif of a punk fanzine, only later adopting a more sober tenor for its industrial reportage’ (Evan Smith and Matthew Worley, Against the Grain. The British far left from 1956 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), p. 135). See also Donaghey, Punk and Anarchism. op. cit. Ref. 4.

[7] A few writers have attempted to recuperate the term ‘lifestylist’ from its pejorative use, see: Portwood-Stacer, Lifestyle Politics, op. cit. Ref. 4 and Matthew Wilson, Biting the Hand that Feeds Us. In Defence of Lifestyle Politics, Dysophia Open Letter #2 (Leeds: Dysophia, 2012).

[8] This description applies within anarchist philosophy and activism and should not be confused in this context with autonomist-Marxist Operaismo or pejorative slurs associated with Leninist-Marxism.

[9] Murray Bookchin’s polemical derision for ‘lifestyle anarchism’ is expounded in Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism. An Unbridgeable Chasm (Edinburgh: AK Press, 1995). The identification of ‘lifestylism’ as an anarchist current predates Bookchin’s rant by at least a decade, as exemplified by Class War here. Bookchin’s screed has informed the terms of anti-lifestylist critique over the last quarter century, but it is interesting that, throughout most of his life, Bookchin was actually highly concerned with typically ‘lifestylist’ tenets such as culture and ‘self-emancipation’ (Murray Bookchin, ‘Post Scarcity Anarchism,’ in Terry M. Perlin (Ed.), Contemporary Anarchism (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books, 1979), p. 265). For a thorough demolition of Bookchin’s Social anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism see Laurence Davis, ‘Social Anarchism or lifestyle anarchism: an unhelpful dichotomy,’ Anarchist Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, (2010), pp. 62–82.

[10] Jeppesen, ‘The DIY post-punk post-situationist politics of CrimethInc.,’ op. cit., Ref. 4, p. 25 fn.

[11] Profane Existence, no. 4, (June 1990), n.p. [emphasis added].

[12] Portwood-Stacer, Lifestyle Politics, op. cit., Ref. 4, p. 132 [emphasis added].

[13] Sean Martin-Iverson, ‘Anak punk and kaum pekerja: Indonesian Punk and Class Recomposition in Urban Indonesia,’ draft paper from ‘Encountering Urban Diversity in Asia: Class and Other Intersections’ Workshop (Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore), 15–16 May 2014, p. 10.

[14] O’Hara, The Philosophy of Punk, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 87.

[15] Black Flag was founded in the UK in 1970 by Stuart Christie, originally as the organ of the Anarchist Black Cross (https://libcom.org/tags/black-flag [accessed 25 September 2017]), and according to Smith and Worley ‘stood firmly within the “revolutionary class struggle” traditions of anarchism’ (Smith and Worley, Against the Grain, op. cit., Ref. 6, p. 135). The most recent issue of Black Flag appears to have been #233 in 2011 (http://blackflagmagazine.blogspot.co.uk/[accessed 25 September 2017]).

[16] Nick Heath, ‘The UK anarchist movement—Looking back and forward,’ originally written for an issue of Black Flag, posted to libcom.org by ‘Steven’ (15 November 2006): http://libcom.org/library/the-uk-anarchist-movement-looking-back-and-forward [accessed 10 November 2014].

[17] To assuage any confusion, Daniel O’Guérin is a pseudonym adopted by a prominent zine publisher and anarchist activist from the north of Ireland—the name is a pastiche of/homage to Daniel Guérin, the well-known French anarchist/Marxist political theorist.

[18] O’Guérin, ‘What’s in (A) song?’ op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 20 [emphasis added].

[19] McKay, DiY Culture, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 17 [emphasis added].

[20] Martin-Iverson, ‘Anak punk,’ op. cit., Ref. 13, p. 2.

[21] Throughout this article, the term ‘anarcho-punk’ is used to refer particularly to the anarcho-punk genre initiated and nurtured by Crass and its particular aesthetic, with ‘anarchist-punk’ used to indicate punk bands that have an engagement with anarchist politics in a broader sense.

[22] Ian Bone, Bash the Rich. True-life confessions of an anarchist in the UK (Bath: Tangent Books, 2006), p. 121.

[23] In Donaghey, Punk and Anarchism, op. cit., Ref. 4, p. 285.

[24] In Donaghey, ibid., p. 291.

[25] Bone, Bash the Rich, op. cit., Ref. 22, p. 196.

[26] In Donaghey, Punk and Anarchism, op. cit., Ref. 4, pp. 51–52.

[27] Bone, Bash the Rich, op. cit., Ref. 22, p. 119.

[28] Rock Against the Rich (1988) consisted of ‘gigs in towns and cities all over the country, each one highlighting the working class struggles in that particular area,’ to ‘support these communities and workers physically, politically and financially in their resistance’ (Class War, c. 1988. n.p.).

[29] Class War Federation, Unfinished Business … the Politics of Class War (Edinburgh: AK Press, 1992), p. 168.

[30] Jimmy Grimes, quoted in Bone, Bash the Rich, op. cit., Ref. 22, p. 119 [emphasis added].

[31] McKay, Senseless Acts of Beauty, op. cit., Ref. 3, pp. 77–78.

[32] The Heavy Stuff, no. 2, (c. 1988). Undated, p. 18).

[33] Bone, Bash the Rich, op. cit., Ref. 22, p. 166.

[34] CrimethInc. Ex-Workers’ Collective, Days of War Nights of Love. Crimethink for Beginners (Salem, Oregon: CrimethInc. Free Press, 2001 [2011]).

[35] CrimethInc. Ex-Workers’ Collective, Expect Resistance. A Field Manual (Salem, Oregon: CrimethInc., 2008).

[36] CrimethInc. Ex-Workers’ Collective, Work (Salem, Oregon: CrimethInc., 2011).

[37] CrimethInc. Ex-Workers’ Collective, Contradictionary. A Bestiary of Words in Revolt (Salem, Oregon: CrimethInc. Writers’ Bloc, 2013).

[38] Rolling Thunder: an anarchist journal of dangerous living, no. 3, (summer 2006), p. 108.

[39] Jeppesen, ‘The DIY post-punk post-situationist politics of CrimethInc.,’ op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 29.

[40] Ibid., p. 25.

[41] Rolling Thunder: an anarchist journal of dangerous living, 7 (spring 2009), p. 69.

[42] Ibid., p. 69 [emphasis in original].

[43] Ibid., p. 69.

[44] Ibid., p. 74.

[45] Ibid., p. 74.

[46] Private communication with the author February/March 2018.

[47] Ibid.

[48] O’Guérin, ‘What’s in (A) song?’ op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 18 [emphasis added].

[49] Richard Porton, ‘Introduction,’ in Richard Porton (Ed.), Arena One: On Anarchist Cinema (Hastings: ChristieBooks, and Oakland, California: PM Press, 2009), p. iv. Though, according to Norman Nawrocki, at least one of the ‘old-guard,’ Albert Meltzer, thought the Sex Pistols’ ‘Anarchy in the UK’ was ‘bloody good’ (Norman Nawrocki, ‘From Rhythm Activism to Bakunin’s Bum: Reflections of an unrepentant anarchist violinist on “anarchist music,”’ in Daniel O’Guérin (Ed.), Arena Three: Anarchism in Music (Hastings: ChristieBooks, 2012), p. 64).

[50] Raoul Veneigem, The Revolution of Everyday Life, Anarchist Library version, (1963–1965) https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/raoul-vaneigem-the-revolution-of-everyday-life.pdf [accessed 9 February 2018], p. 11).

[51] Bone, Bash the Rich. op. cit., Ref. 22, p. 256.

[52] Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, the anarcho-syndicalist union in Spain which was a prominent force during the Spanish Revolution and Civil War and continues to be active today, despite harsh repression during the Franco dictatorship. For information on their current campaigning, see http://www.cnt.es/[accessed 13 December 2017].

[53] Bone, Bash the Rich, op. cit., Ref. 22, p. 102.

[54] Freedom was first published in 1886. Smith and Worley describe Freedom as ‘the longest running of British anarchist newspapers, [which] reflected the interest of a wider libertarian readership, and had stronger roots in the more liberal, artistic, cultural and intellectual traditions of the movement’ (Smith and Worley, Against the Grain, op. cit., Ref. 6, p. 135).

[55] Bone, Bash the Rich, op. cit., Ref. 22, p. 167.

[56] The Heavy Stuff, no. 1, (December 1987), p. 13.

[57] The Friends of Class War, Class War Classix, (spring 2012), p. 4. This attack goes on to explicitly identify ‘the Libcom website’ among other anarchist organizations.

[58] Class War, no. 38, (c. 1989). Undated, n.p.

[59] CrimethInc., Days of War Nights of Love, op. cit., Ref. 34, p. 111.

[60] Ibid., pp. 188–189, [bold and caps in original].

[61] A cursory glance at some early punk releases demonstrates the repeated ‘boredom’ trope: The Buzzcocks, ‘Boredom,’ Spiral Scratch EP, (New Hormones, 1977); The Adverts, ‘Bored Teenagers,’ The Roxy London WC2 compilation, (Harvest, 1977); The Clash, ‘I’m So Bored With The USA,’ The Clash, (CBS, 1977); and even Crass are repeatedly ‘bored,’ providing a link with the anarcho-punk scene, for example, ‘End Result,’ The Feeding of the 5000, (Crass, 1978), and ‘Chairman Of The Bored,’ Stations of the Crass, (Crass, 1979). This is by no means an exhaustive list, boring though it is. For more on early punk and anarchism, see Donaghey, ‘Bakunin Brand Vodka,’ op. cit. Ref. 1 and Matthew Worley, No Future: Punk, Politics and British Youth Culture, 1976–1984 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

[62] Sandra Jeppesen discusses the Situationist influence in the case of CrimethInc. in ‘The DIY post-punk post-situationist politics of CrimethInc.,’ Anarchist Studies, 19, 1 (2011), pp. 23–55.

[63] Rolling Thunder: an anarchist journal of dangerous living, 2 (winter 2006), p. 18.

[64] Though a group calling themselves London Class War persisted, continuing to publish Class War, and from which subsequent iterations of Class War have emerged.

[65] Class War, no. 73, (summer 1997), p. 8.

[66] Ramsay Kanaan in Joe Biel, Beyond the Music: How Punks are Saving the World with DIY Ethics, Skills, & Values (Portland, Oregon: Cantankerous Titles, 2012), p. 75.

[67] Ibid.

[68] ‘Never be deceived that the rich will allow you to vote away their wealth.’ See Lucy Parsons, Freedom, Equality and Solidarity (Chicago, Illinois: Charles H. Kerr, 2004).

[69] Class War, (c. August 1986). Not numbered, undated, n.p. [caps in original].

[70] Class War Federation, Unfinished Business, op. cit., Ref. 29, pp. 58–59 [emphasis added].

[71] Ibid., p. 58.

[72] In addition to workers in all sorts of industries and the unemployed, the definition goes on to explicitly include some controversial occupations, such as workers in ‘the finance industry up to section supervisors, soldiers up to NCOs [Non-Commissioned Officers], police up to seargent [sic] … & many of the self employed[.]’ (Class War Federation, ibid., p. 58).

[73] Andy Anderson and Mark Anderson, The Enemy is Middle Class (Manchester: Openly Classist, 1998), p. 19.

[74] Anderson and Anderson, ibid., p. 20 [emphasis added]. And likewise, middle-class people must engage in ‘pathetic and ridiculous antics … (in dress, speech, behaviour) so as to try to feel like and/or be taken for “working class”’ (Anderson and Anderson, ibid., p. 19).

[75] The Heavy Stuff, no. 1, (December 1987), p. 12.

[76] Class War, no. 73, (summer 1997), p. 6.

[77] Class War, ibid., p. 6.

[78] Class War, ibid., p. 6 [emphasis added].

[79] Jon Bigger was the Class War Party candidate for Croydon South in the 2015 UK General Election and is completing a PhD thesis at Loughborough University drawing upon his experiences.

[80] Jeppesen, ‘The DIY post-punk post-situationist politics of CrimethInc.,’ op. cit., Ref. 4, p. 43 [emphasis added].

[81] CrimethInc., Contradictionary, op. cit., Ref. 37, p. 255.

[82] CrimethInc., Work, op. cit., Ref. 36, p. 250.

[83] Ibid., p. 250.

[84] Ibid., p. 349.

[85] Ibid., p. 97 [emphasis added].

[86] Rolling Thunder: an anarchist journal of dangerous living, no. 6, (autumn 2008), p. 7 [emphasis added].

[87] Jeppesen, ‘The DIY post-punk post-situationist politics of CrimethInc.,’ op. cit., Ref. 4, p. 33.

[88] Jeppesen, ibid., p. 25 [emphasis added].

[89] CrimethInc., Work, op. cit., Ref. 36, p. 250 [emphasis added].

[90] Rolling Thunder, no. 2, op. cit., Ref. 63, p. 18.

[91] Profane Existence, no. 13, (February 1992), quoted in O’Hara, The Philosophy of Punk, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 40 [emphasis added].

[92] Jeppesen, ‘The DIY post-punk post-situationist politics of CrimethInc.,’ op. cit., Ref. 4, p. 40). Jeppesen describes this as ‘precarity activism’ and the footnote points to ‘www.precarity-map.net which maps out collectives, social centres, media, coordination networks, unions and militant research groups across Europe and in Australia’ (Jeppesen, ibid., p. 40, f.n.).

[93] CrimethInc., Work, op. cit., Ref. 36, p. 207.

[94] Ibid., p. 242 [emphasis added].

[95] Private communication with the author February/March 2018.

[96] CrimethInc., Days of War, Nights of Love, op. cit., Ref. 34, p. 39 [emphasis added].

[97] CrimethInc., Expect Resistance, op. cit., Ref. 35, p. 45.

[98] Ibid., p. 148.

[99] Rolling Thunder, no. 2, op. cit., Ref. 63, p. 10.

[100] Ibid., p. 17. In Work, CrimethInc. take this qualification even further, writing that ‘those who drop out don’t find themselves in another world—they remain in this one, plunging downward’ (CrimethInc., Work, op. cit., Ref. 36, pp. 311–312).

[101] ‘About Anarkismo.net,’ http://anarkismo.net/about_us [accessed 29 November 2014].

[102] Libcom, ‘libcom.org: an introduction,’ (11 September 2006), http://www.libcom.org/notes/about [accessed 29 November 2014].

[103] W, ‘Rethinking Crimethinc.,’ (4 September 2006), http://www.anarkismo.net/article/3664?condense_comments=true [accessed 10 November 2014].

[104] Ramor Ryan, ‘Days of Crime and Nights of Horror,’ posted by Steven, (4 April 2011), (first published in Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, not dated), https://libcom.org/library/days-crime-nights-horror-ramor-ryan [accessed 10 November 2014].

[105] AK Thompson, Black Bloc White Riot. Anti-Globalization and the Genealogy of Dissent (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2010), p. 95.

[106] W, ‘Rethinking Crimethinc.,’ op. cit., Ref. 103, quoted in Thompson, Black Bloc White Riot, op. cit., Ref. 105, endnote 22, p. 174.

[107] Ryan, ‘Days of Crime and Nights of Horror,’ op. cit., Ref. 104.

[108] W, ‘Rethinking Crimethinc.,’ op. cit., Ref. 103.

[109] To their credit, CrimethInc. engage very generously with these decidedly ungenerous attacks, writing in conciliation with their critics, that ‘[t]he focus on lifestyle as an end in itself among passive consumers of CrimethInc. literature … has maddened its authors as well’ (Rolling Thunder, no. 3, op. cit., Ref. 38, p. 111).

[110] Bookchin, Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism, op. cit., Ref. 9.

[111] Class War, (c. April 1985). Not numbered, undated, n.p.

[112] Class War, (c. August 1986). Not numbered, undated, n.p.

[113] Class War, no. 73, (summer 1997), p. 8.

[114] Class War Federation, Unfinished Business, op. cit., Ref. 29, p. 80 [emphasis added].

[115] Ibid., pp. 78–79.

[116] Ibid., p. 101 [emphasis added].

[117] As it is termed by Davis in ‘Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism,’ op. cit., Ref. 9, p. 62. He continues: ‘Its defining characteristic is the recognition that the liberation of everyday life is an essential component of the anti-authoritarian revolutionary change’ (Davis, ‘Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism,’ ibid., p. 63).

[118] Ibid.

[119] Diane Morgan, ‘Saint-Simon, Fourier, and Proudhon, “Utopian” French Socialism,’ in Tom Nenon (ed.), Vol. I (1780–1840) History of Continental Philosophy (Dublin: Acumen Press, 2010), p. 302.

[120] Nicolas Walter, About Anarchism (London: Freedom Press, 1969 [2002]), p. 30.

[121] Roger Sabin, ‘Interview with Stephen Duncombe and Maxwell Tremblay, editors of White Riot: Punk Rock and Politics of Race,’ in Punk and Post-Punk, 1, 1 (2012), p. 107.

[122] Henri De Lubac, The Un-Marxian Socialist (London: Sheed and Ward, 1948), p. 165.