Institute For The Study of Insurgent Warfare

The Seemingly Quixotic, but Remarkably Effective, Journey of a Small Band of Extreme Islamists

And Why It Seems As If They Are Winning, When They May Not Be

From Al-Qaeda in Iraq to the Anbar Awakening

Civil War, The Rise of Maliki and the Institutionalization of Sectarianism

The Withdrawal of American Troops, the Revolution in Syria, the Arab Spring in Iraq

The Current Situation and Its Misconceptions

Introduction

Over the past weeks the news has been dominated by the discussion of the advances of the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS, The Islamic State of Iraq and asSham/Syria) through Iraq, the apparent ease with which this has occurred, and the virtual absence of any concerted resistance from an Iraqi military that was trained and armed through an expensive and arduous US military program. The common narrative in the Western media has been centered around the extremism of ISIL, their supposed military prowess, the “threat” that the organization poses domestically to the United States, and the potential for US military intervention in response. There have been other voices, largely in the think tank community, that have been attempting to inject an element of nuance, through a discussion of the constellation of fighting forces on the ground, a discussion of the political history behind the recent uprising, and some of the possible regional dynamics at work, but these have been largely ignored. This seems to be a result of the opacity of the entire discourse, the density of the recent history in the area, and the complexity of the situation on the ground. However, without this sort of background the current events seem to have sprung from nothingness.

As the dominant narrative goes, the US military drew down forces from Iraq in 2010 after succeeding in their mission to stabilize the political structure that resulted from the US invasion and occupation of the country in 2003. There are clearly issues with this narrative, issues that are clear to anyone that has been following events in Iraq closely for the past decade, but even where doubt about this narrative has persisted there is still a sense that the past few years have been relatively stable in Iraq. Hidden by this narrative is not only the political resentment that has been accelerating since 2010, culminating in a protest and occupation movement that was violently dispersed in the early part of 2014, but also the quiet reorganization that has been undertaken by a number of insurgent groups, as well as the dynamics of a region that is characterized by false borders that traverse vast swaths of open desert, a region that has been in a process of political upheaval for the past three years, particularly in Syria and bordering regions of Iraq.

To really understand the media phenomena that is now termed ISIL we have to first be clear about some points.

Primary among these is the multiplicity of forces that are arrayed within Iraq, specifically the tribal councils, most importantly in the rural north and east of the country, Kurdish groups, and the myriad of organizations participating in the current insurrection, which has largely, though inaccurately, been attributed completely to ISIL. But before discussing ISIL and the current array of forces around Iraq we will return to a period before ISIL or any of its previous incarnations existed, to May 22, 2003, when Paul Bremer signed Coalition Provisional Authority Order Number 2 disbanding the Iraqi military and placing 400,000 people with arms and military training out of work. This move is widely considered to have set the stage for the Iraqi insurgency against the US occupation forces, beginning a trajectory that would move from resistance to occupation through sectarian civil war, the founding of AlQaeda in Iraq and the sectarian militias, the collapse of AQI from US counterinsurgency, the Anbar Awakening (a movement which had much to do with American funding of employment) and the betrayal of the Awakening members by first the US and then the Maliki regime.

It is in this background that we can understand how a small organization, less than 5,000 fighters by most estimates, has come to be the most dominant military force in an area roughly the size of Indiana in which there are tens of thousands of insurgents and any number of regime forces, and how they could launch a lightning strike of such speed and ferocity. Without this background it would almost seem as if ISIL is an invincible force, impervious to defeat, with unlimited resources and numbers that vastly outweigh the actual levels of force that they are able to deploy. ISIL is very adept in the use of guerrilla tactics, and many fighters within their ranks have previous experience in insurgent conflict in Iraq, Syria, or Chechnya, among other places, but it is not possible to understand the dynamics of the current conflict without examining their tactics through one essential lens; they are really good at projecting force, expanding capacity and moving through space quickly. This approach, though highly effective currently, generates a widely dispersed force dependent on other elements for its success. The strategy becomes difficult to maintain after a common objective dissipates, and makes impossible the inevitable attempt to move on to constitute the state. State building requires occupying, holding and policing space, and much higher concentrations of force than ISIL is currently able to mobilize. But before moving ahead in this analysis it is important to establish events starting from March 19, 2003, a day many of us who were active at the time remember, the day that Shock and Awe began in Iraq.

Background

From Al-Qaeda in Iraq to the Anbar Awakening

To understand the rise of ISIL we must begin with AlQaeda in Iraq, and to understand that story it is important to work through two threads, threads which converge in Iraq in 2003. One follows the history of US support for Israel, involvement in arming the mujahedeen in Afghanistan in their fight against the Soviets, the first Gulf War and the sanctions that followed, the invasion of Afghanistan after September 11, and the invasion of Iraq in 2003. This is a well chronicled path; if one would like to look further I would suggest reading Ghost Wars by Stephen Coll.

The second path, deeply entwined with the first, is the path of a man named Abu Masab alZarqawi, a Jordanian former street criminal who, upon his release from a Jordanian prison in the late eighties goes to Afghanistan to fight against the Soviets. On his return to Jordan in the early nineties he is arrested on charges of possessing firearms and explosives and imprisoned for six years. During this time in prison Zarqawi begins organizing Salafi prisoners, setting the stage for the path that will lead him to Iraq. Upon his release in 1999 he founds an organization called al Tawhid walJihad and is quickly implicated in an attempt to bomb a hotel frequented by Americans and Israelis, leading him to flee to Peshawar, Pakistan. In Pakistan he begins to organize fighters, and crosses the border into Afghanistan to start a training camp along the northwestern border with Iran, which by most accounts specializes in bomb making and poisoning tactics.

When the US invasion of Afghanistan commences Zarqawi flees the country, likely ending up in the Kurdish areas of northwestern Iraq. In September 2002 he returns to Jordan for a short period, leaving quickly after Lawrence Foley, the US ambassador to Jordan, is assassinated, and crosses back into Iraq, setting up in Fallujah. After the US invasion of Iraq, and the beginning of a low level insurgency by a small number of Iraqis, Zarqawi organizes fighters to begin to escalate attacks against the foreign occupation.[1]

In August of 2003 Zarqawi and associates in al Tawhid walJihad bomb the UN headquarters in Baghdad and begin a campaign of kidnapping and beheading foreign operatives, including Nicolas Berg, and filming the executions for propaganda purposes. Attacks also begin to escalate against Iraqi governing council members and the nascent security forces in the country. During this time, the Iraqi military is disbanded, with hundreds of thousands of former soldiers, many still in possession of their weapons, put out of work. This, combined with the economic collapse that quickly followed the invasion, generates a desperate situation, made worse when the Coalition Provisional Authority ends former Iraqi government social service programs, such as the disbursement of food rations, that had been organized during the sanctions regime that persisted from the end of the Gulf War to the beginning of the 2003 invasion. This leads to a multilayered insurgency, with a number of organizations, small militias and tribal groups participating in overlapping ways. Zarqawi and his associates function as a core of specialized fighters, one of many; what sets them apart is their target set. Rather than attacking troop patrols, checkpoints and low level enforcers of the occupation, al Tawhid walJihad targets the infrastructure of foreign occupation through the use of tactics that generate psychological terror rather than material disruption, pressuring UN employees and security contractors to either limit operations to more secure areas or curtail operations altogether.[2]

The pace of conflict accelerates dramatically due to events in Fallujah in April of 2003. Fallujah had revolted against the Hussein regime on a number of occasions, and the US stationed very few troops in the area as a result, assuming that any insurgency would be carried out by latent remnants of the Baath Party. A detachment of troops from the 82nd Airborne enters the city on April 23, 2003 and occupies a school to use as a forward operating base and organizational center. Around nightfall a group of demonstrators gathers around the school to demand that the troops vacate the building and allow it to open as a school again. As the demonstration wears on the troops, now occupying the rooftop, begin to fire tear gas in an attempt to disperse the crowd. Some within the crowd began throwing rocks and firing weapons at the school, which results in a half hour long exchange of gunfire, killing 17 demonstrators and wounding over 70. Three days later a demonstration against the occupation of the city is fired on, leading to the deaths of three more demonstrators. By June American patrols are under frequent attack within the city, as are the local police, leading to American troops withdrawing to fire bases on the outskirts of the city by the beginning of 2004.

Interestingly, a very similar dynamic is playing itself out in Mosul around the same time, a city under the command of General David Petraeus, and the site of the primary experiment in counterinsurgency tactics in Iraq. In both situations the paradoxes of counterinsurgency become readily apparent. Counterinsurgency requires close proximity between an occupied population and an occupying force, a proximity that the occupiers use to both gather intelligence on possible threats, and build alliances with local power brokers for mutual benefit. This close proximity also generates a level of conflict, a visibility of occupation, the presence of checkpoints, convoys, patrols, etc., leaving occupying troops open to attack. Even a single attack forces occupation troops to adopt a more defensive posture, creating distance from the same population from which they are attempting to extract information and coopt. This distance not only casts the street as an opaque space, one that occupation forces have a difficult time penetrating, but also creates a material conflict, an easy differentiation between friends and enemies. As countermeasures begin to be taken by occupation forces, the rate of attacks increases, leading to escalated counterattacks, feeding a dynamic of conflict that accelerates and spreads out geographically. In the case of Mosul this leads to the walling off of the city from the outside, the setting up of checkpoints and cameras, and the conversion of the city into a gigantic prison. In Fallujah American troops respond by pulling out of the city, setting up fire bases on the outskirts, and launching “lightning raids” into the city, setting the stage for the events of March 31, 2004.[3]

On this day four security contractors from Blackwater are ambushed as they attempt to move in an armed convoy through the center of the city. Their vehicles are burned, the bodies pulled out, filmed, and dragged through the streets before being hung from a bridge. The attack makes international news and prompts a dramatic American military response that becomes known as the First Battle of Fallujah, a military campaign which involves the blockading of the city, the expulsion of residents not considered to be fighters by the US military, and the systematic bombing and shelling of the city, killing hundreds. These events catalyze the public rise of two organizations that will soon play an integral role in the war, the Mahdi Army, a Shia extremist group led by Muqtada al Sadr, and the growth and metamorphosis of al Tawhid walJihad into AlQaeda in Iraq[4]. This concurrent rise happens for different reasons, but centers on a common trend developing in Iraq. The invasion and destruction of much of Fallujah is symptomatic of an approach becoming fashionable within US military circles using overwhelming force to crush resistance movements that are based in localized structures and grievances. More formal organizations, such as AlQaeda in Iraq or the Mahdi Army, are more the exception than the rule; but in the fallout from the strategy of overwhelming force both groups begin to gain traction.

The Mahdi Army, the largest of a number of sectarian Shia organizations, who along with the Badr Brigades and Kata’ib Hizbollah, among others, had begun to engage in resistance, sometimes funded and trained by elements of the Iranian military and intelligence apparatus, almost immediately after the invasion. This resistance begins intensify during the fighting in Fallujah, with the closing of a Sadrowned newspaper in April of 2004, beginning the trajectory of events that will lead to an armed uprising consuming the Sadr City area of Baghdad and Najaf, among other places, largely southeast of Baghdad to the Iranian border. At the same time, as a direct result of the assault on Fallujah, Sunni dominated organizations, including AlQaeda in Iraq, and organizations tied to the former Baathist regime begin to recruit more fighters, and insurgent activity increases within Sunni dominated areas of Baghdad and the north and west of the country. These two parallel trajectories of resistance take on increasing magnitude, with the pace of the insurgency accelerating, until a point in 2006 when they collide, with horrendous consequences.[5]

Civil War, The Rise of Maliki and the Institutionalization of Sectarianism

In January of 2005 attacks are carried out on polling places and political candidates for the new National Assembly, which is tasked with drafting a new Iraqi constitution. Among those elected to this assembly is Nouri alMaliki, a politician from the sectarian Shia Dawa Party and member of the DeBaathification Committee. Maliki will go on to serve numerous stints as Prime Minister, a rise that will be explained as the story proceeds. In September of that year, as the government begins to organize the October referendum on the draft constitution, AlQaeda in Iraq seizes the town of Qaim, which lies on the border of Syria and Iraq, which it intends to use as a mobilization base for operations to disrupt the referendum. In a communique AlQaeda in Iraq declares war on the Shia majority, a declaration that it would begin to act on quickly.

After the December parliamentary elections, which result in a majority for the United Iraqi Party, a Shia political bloc, the sectarian war threatened by AlQaeda in Iraq begins with the bombing of sites around Karbala, as well as a police station in northern Baghdad, killing 130 largely Shia civilians. Concurrently with this offensive AlQaeda in Iraq announces the launch of the Shura Council of the Mujahedeen, a coalition that ostensibly combines the largely foreign forces in AlQaeda in Iraq with the more localized forces of other Sunni Islamist organizations and tribal groups.

Sectarian violence begins to increase around the country, culminating in the act that is widely credited with beginning the mass sectarian killings that characterized the civil war in Iraq, the bombing of the Al-Askari mosque in Samarra on February 22, 2006. The resulting firestorm quickly engulfs the entire country, with sectarian militias routinely bombing public places, killing families, and kidnapping hundreds off the streets, many of whom would turn up dead days later with clear signs of torture. The reaction to this bombing facilitates the rise of Maliki, leads to the sectarian segregation of large areas of Iraq through ethnic cleansing, and gives birth to the battlefield dynamics that characterize today’s conflict.

AlQaeda in Iraq made the decision to bomb the AlAskari mosque against the advice of Osama Bin Laden. Through the publication of a series of letters captured in raids and intercepts we get an interesting glimpse into the inner workings and strategic differences of the networks of foreign fighters that emerged from the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, expanded into Yemen, Somalia, and parts of northern Africa, and uses the brand of AlQaeda as an organizing and logistical hub and moniker. In one of the intercepted communications is an exchange that occurred between February 2004 and June 2005 in which Zarqawi and Bin Laden, through an aide going by the name Atiyah (likely Atiyah Abd alRahman), discussed the strategic effectiveness of generating a sectarian conflict in Iraq. Zarqawi argues, in a letter intercepted in February 2004, that the creation of a civil war would generate a scenario where the US occupation forces would be caught in the middle of a general conflagration between warring factions, unable to act without being seen as taking sides and generating more animosity, animosity which would further fuel the insurgency[6].

In his response, likely written in December 2005 and captured after Zarqawi’s death in June 2006, Atiyah argues that this may well be the case, but that in the process AlQaeda would lose any hope of gathering public support, a prediction that would prove to be remarkably accurate[7].

As the body count spirals out of control, with hundreds turning up dead each morning, dynamics begin to play out which will prove integral to both the ending of the US occupation and the rise of Nouri alMaliki, besides setting the stage for the current crisis. In April 2006 Prime Minister Ibrahim al Jafaari is forced to step down amidst accusations of sectarianism by Sunni and Kurdish politicians. After his dismissal the CIA begins to screen candidates from various Shia political parties for connections to the Iranian regime. At the end of this process Nouri alMaliki is the one left standing, and is promptly appointed to be Jafaari’s replacement as Prime Minister. With the appointment of Maliki a concerted campaign against Sunni insurgent groups begins in earnest, through a combination of American and Iraqi security and military forces. This initiative drives Sunni insurgent groups out of many of the cities that they had been occupying, but also begins two other distinct processes. Firstly, in the attempt to bolster Iraqi security forces Maliki draws from elements he can count on, the sectarian Shia fighters of the Mahdi Army and Badr Brigade. This results in sectarian killings accelerating in tandem with combat against Sunni insurgents. Maliki’s new recruits carry out a campaign of ethnic cleansing, with many police, soldiers and ministers being directly complicit in kidnapping, torture and murder on an absolutely serial scale. This drives many Sunni civilians into extremist resistance organizations, including AlQaeda in Iraq. These organizations then exploit their increasing numbers to impose control over Sunni areas, often through the intimidation and killing of opponents. The increasing violence in Sunni communities, coming both from their own “protectors” and Shia death squads, results in a backlash, an initiative that becomes known as the Sons of Iraq.[8]

The Sons of Iraq arise in 2005 on a localized level, with an approach by Iraqi tribes to a local Marine commander, asking for assistance in expelling AlQaeda in Iraq from the area after a series of actions that were perceived as disrespectful. As sectarian violence increases throughout 2006 and into 2007 the occupation forces notice a distinct problem; they can not function in local areas without exposing themselves to attack, and the Iraqi security forces are hopelessly sectarian. They need an alternative. At this time counterinsurgency doctrine is growing more popular within US military command circles, centering on the attempt to coopt local forces, both to generate support for the occupation and to identify both the reconcilable and irreconcilable elements within the resistance. Drawing from local initiatives, the US creates a program to arm and pay local civilians and former insurgents to fight against irredeemable Sunni rebels, termed the Sons of Iraq or the Awakening Movement. This strategy carries an inherent danger for the general project of the US occupation of Iraq, which was ostensibly to create the conditions for a sustainable state structure to function. Awakening Movement fighters are meant to fight other Sunni militants, while ignoring the atrocities committed by Shia death squads. Their arms and training could be turned easily against the very state that the US is attempting to prop up, a state which is directly complicit in ethnic cleansing and mass murder of civilians in Sunni neighborhoods and towns. This scenario would come to pass in the nottoodistant future.

In the attempt to ensure their loyalty the Awakening groups are guaranteed a certain voice in the political process, placement in the security forces, and guaranteed command positions within a multiethnic military and security apparatus, but end up betrayed. The beginning of the erosion of this agreement, and another central ingredient to understanding the current unrest, appears at a pivotal point in 2007. Between 2006 and 2007 Maliki’s control over the military is somewhat limited. He does not hold the post of Commander in Chief, and is not the final arbiter of decisions within the military structure. He can however appoint sectarian ministers to lead government departments, who then form their own special forces units, all of which answer to Maliki, and most of which are used to carry out sectarian killings, often in the basements of government buildings. Thus Maliki controls a sort of Praetorian Guard of highly trained special forces units. It soon becomes clear that state forces are not only sectarian, but also corrupt, with many positions purchased, from low ranking police officers all the way up to generals in the army. Graft is rampant while military acumen and experience are almost entirely absent. To further solidify these changes and exert even more control over the security apparatus Maliki makes three distinct moves; taking control of he office of Commander in Chief, appointing a loyal general to command the Operations Center (a command center for operations in provinces experiencing active insurgency), and formalizing individual special forces units into an elite new unit called Iraq’s Special Operations Force, American trained counterterrorism troops directly under Maliki’s control. ISOF exists completely outside of both the chain of military command and any parliamentary oversight, complete with an offthebooks black budget. Like similar structures in Libya and Syria, the idea is to make a coup almost impossible.

Not only are those involved in the command and control of military operations all directly beholden to Maliki for their positions, but any attempted coup could only draw from an understaffed, underequipped force of inexperienced troops, troops which would have to go against the well trained and equipped ISOF. This is a fantastic structure if your goal is to stop a coup, but it creates a lot of problems in the attempt to stop an uprising or fight off an insurgency, a lesson that Gaddafi learned the hard way[9].[10]

The combination of torture and indiscriminate violence by state security forces and the creation of the Awakening Movement by the US does achieve the almost total destruction of AlQaeda in Iraq. As the letter from Atiyah warned, the indiscriminate killing of civilians, the use of coercion to maintain control and the imposition of a strict form of Islamic law generates a backlash, both from Awakening groups and hard line Shia militias, many of which are motivated as much by sectarianism as a sense of self defense. This backlash begins to claim members of the leadership of AlQaeda in Iraq, including Zarqawi, who was killed in a US air strike on his safe house on June 8, 2006, likely after a tipoff from an informant. After the death of Zarqawi AlQaeda in Iraq undergoes a fundamental shift to morph into the ISIL of today. There are two phases in this transformation, both centered around the death of Zarqawi and the rise of Abu Ayyub alMasri, an Egyptian militant, as the new sheik of the organization. Concurrently, AlQaeda in Iraq begins to transform the Shura Council of the Mujahedeen into an organization called the Islamic State of Iraq, a coalition between AlQaeda in Iraq and other Salafi organizations led by Abu Omar alBaghdadi, an Iraqi. The second transformation comes with the 2007 US troop surge and the elimination of much of the core of foreign fighters that had dominated AlQaeda in Iraq up to this point[11].

The 2007 surge involves the deployment of 20,000 additional troops to Iraq, most of which are sent to Baghdad. But, contrary to media accounts, the surge is not merely a small increase in troop numbers, but a fundamental realignment of US military strategy and priorities. A faction led by David Petraeus had been pushing for a shift in strategy away from the attempt to patrol space, with troops retreating to their fire bases and ceding space at night, thus maintaining a distance from a population that was opaque from a military operations standpoint. The surge involves a series of initiatives in Baghdad, beginning with a concerted offensive into a belt of cities on the outskirts of Baghdad that AlQaeda in Iraq/Islamic State of Iraq were using as logistics bases. In these raids large numbers of foreign fighters are killed, gutting the core of the organization. In the wake of these offensive pushes US occupation troops move into the core of the cityspace, occupying and fortifying key buildings and running patrols through neighborhoods. This dramatically increases the number of US casualties, concurrent with an increase in their exposure to attack and the number of engagements, but allows them to conduct operations on a more regular basis and occupy centers of social interaction such as markets, inserting themselves as both an armed force and the central arbiter of all issues. Finally, the surge includes an element of the plan that Petraeus had enacted in Mosul four years prior, the use of walls to limit and channel movement within the city. The occupying forces set about building such walls between neighborhoods and setting up checkpoints to control movement into and out of areas. This severely limits the ability of insurgent groups to get supplies and move into operational zones, but also entrenches the lines that were drawn through mass murder and ethnic cleansing, preventing many former residents of neighborhoods from ever returning home. (Recently ISIL has taken to tearing many of these same walls down in Mosul, in a propaganda move to build popular support.) Though AlQaeda in Iraq/the Islamic State of Iraq will continue to carry out bombings of public spaces, their presence on the ground is marginalized, and they begin a period of increasingly infrequent activity and organizational restructuring[12].

The Withdrawal of American Troops, the Revolution in Syria, the Arab Spring in Iraq

On December 14, 2008 George W Bush signs the Status of Forces Agreement to begin the process of drawing down American forces in Iraq. The agreement calls for the removal of all nonUS forces from Iraq, most of which are completely withdrawn before December 31, 2008, the withdrawal of all American forces from cities before June 30, 2009 and the complete withdrawal of remaining forces by December 31, 2011. Starting in early 2009 American troops begin pulling back from cities and largely operating in a support and training role, patrolling areas and carrying out joint operations. Like many insurgent groups al Qaeda in Iraq begins to switch strategic targeting from a focus on American forces to a focus on the functioning of the Iraqi state, a move that sees the group engage in an increasing number of actions aimed at ministry buildings, Iraqi military and police activities, as well as attempting to perpetuate the civil war through attacks on Shiite civilians. During this time another shift begins to occur, with the death or imprisonment of many of the foreign fighters that formed the core of the organization in the past the composition of the group becomes more based in Iraqi Salafist militants. This shift is due to two factors. Firstly, the Surge led to the death and imprisonment of much of the core of the organization but secondly, and possibly more importantly, the centers of gravity for extreme Salafist activity began to diversify, moving into areas like Yemen, Somalia and northern Africa, drawing many of the remaining foreign fighters, and new recruits, to fields of conflict outside of Iraq. This dispersion of force is a response to the concentration of American force in limited spaces, primarily Iraq and Afghanistan, a concentration which leaves other spaces open for intervention. This dispersion leads to the reformulation of American military strategic frameworks, away from the counterinsurgency operations, operations which have large concentrated force footprints in limited areas for long periods of time, to a more mobile, tactile form of counterterrorism operation based in lightning raids by Special Forces, the heavy use of surveillance and attack drones and the deployment of limited engagement forces into areas to support local forces, sometimes with the use of large scale, but limited duration, air cover campaigns, as we saw in Libya and are currently seeing in Iraq[13].

On March 7, 2010 parliamentary elections in Iraq lead to a political crisis. The Iraqiyya bloc, led by Ayad Allawi, wins a plurality over Maliki’s State of Law bloc, but fails to obtain a parliamentary majority, preventing them from forming an acting government. The State of Law bloc also fails to form a coalition, causing a political impasse that will last for nine months. After intervention by Iran to convince Muqtada al-Sadr to support the government, as well as protracted negotiation with Kurdish political parties, an Iraqi government is finally formed. It seems on the surface to be based on concern for ethnic balance and reconciliation, with many ministerial posts shared by members of Sunni and Kurdish political parties, but underlying this superficial diversity many of the old dynamics persist, particularly within the security forces.

During this time another profound shift occurs for Al-Qaeda in Iraq, the death of both Abu Ayyub al-Masri and Oman alBaghdadi in a joint US-Iraqi raid in Tikrit on April 18, 2010. This leads to the rise of a formerly littleknown Iraqi jihadi by the name of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the current leader of ISIL. Al-Baghdadi is a somewhat mysterious figure.

There are few records of his activity before this date, and few pictures have ever been released. It is said that many within his own organization have no idea what he looks like, having only interacted with him while he is wearing a mask. (This changed on July 5 when a video was released of a cleric purporting to be alBaghdadi giving a sermon at a mosque in Mosul). By some accounts alBaghdadi was a cleric of a local mosque during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and was detained by American forces during a 2005 sweep of the area, in which large numbers of men were detained.

Initially held as a civilian internee, he was transferred to Iraqi control under the terms of the Status of Forces agreement, which prevented long term American detention of Iraqi citizens, and then promptly released after being deemed a mild threat. His rise is somewhat vague, but his position on strategy will fundamentally change the organization. He begins his time at the head of the organization at a low point, when attacks have become infrequent and the organization has lost much of its civilian support, operational bases, funding, and sources for foreign fighters[14].

In the period between the rise of alBaghdadi and the rebuilding of AlQaeda in Iraq into first the Islamic State of Iraq and then ISIL, the political calculus of the entire region changes dramatically. In early 2011 the Arab Spring completely reconfigures the political dynamics of the Middle East and Northern Africa. This is not just due to the collapse of the Ben Ali, Mubarak and Gaddafi regimes in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya, but also the alliances that these movements bring to the surface. A new NATO policy of counterterrorism emerges, one based on the use of air power to support local forces, small contingents of special forces to carry out raids and train these local fighters, and the use of arms transfers to gain political influence after the collapse of dictatorships. This shift in policy is an attempt to perfect the strategy NATO employed at the beginning of the war in Afghanistan. This war is thought of as a long running, large scale, military occupation that exists to prop up a failing Karzai regime, but this was a sort of plan B. The initial phase of the war, from October 2001 through to the main force invasion in December 2001, was based on the deployment of a small contingent of CIA and Joint Special Operations Command personnel who were responsible for identifying sympathetic local forces, and arming, training, and supporting them. This strategy failed when Taliban forces left their easily identifiable and targeted logistics bases and government offices, taking to the mountains along the Pakistan/Afghanistan border. The small contingent of US forces supporting poorly equipped Northern Alliance mercenaries was not able to contain this space, necessitating the deployment of 30,000 NATO troops to Afghanistan[15].

In the analogous scenario in Libya local forces, though operating on a different plane of engagement from their so called international representatives in the National Transitional Council, were motivated by more than just money, and willing to accept NATO air cover and military assistance[16].

Two other major transitions occur during the early phases of the Arab Spring, both centered on crushing uprisings. The first is the rise of the Gulf Cooperation Council, an economic and military alliance of Gulf oil states, which undertakes its first major military coordination in support of the Libyan rebels with military training by Qatari special forces, but really comes together around the Saudi invasion of Bahrain to put down the uprising in Manama, centered around the Pearl Roundabout. The other bloc that begins to become more coordinated is centered in Iran, and encompasses the Maliki government in Iraq, the Assad regime in Syria, and Hezbollah in Lebanon. This bloc is supported by Iran economically and militarily. As events begin to move forward we will begin to see these blocs clash in a fight over regional influence, with the Gulf Cooperation Council nations supporting various factions in the Syrian uprising and the bloc centered around Iran supporting the Assad regime, either covertly (the Iraqi government allowing supply flights to cross Iraqi territory and giving sanction to Shia militias to cross the border to intervene) or overtly (Hezbollah intervening directly with Iranian assistance).

With the uprising in Syria these dynamics begin to converge. Like many of the other Arab Spring uprisings the one in Syria begins with demonstrations that are violently repressed. As in Libya, this leads to mass defections from the military. Much like the reconstructed military in Iraq, many of the commanders of the Syrian military are generally inexperienced regime loyalists, with the greatest concentration of force monopolized in the Mukhabarat (the secret police), who are directly under the command of Assad himself. Air Force Intelligence and the elite Republican Guard are also run by regime loyalists. Unlike in Iraq, there is no functional parliamentary oversight to circumvent, but very much like in Iraq the main military forces are populated by undertrained, underequipped troops that are unable to fight off internal resistance. These defecting forces, largely made up of front line troops and low ranking officers, form the nexus of the Free Syrian Army in the late summer and early fall of 2011, beginning mostly as a defensive force which serves to protect demonstrations. Increasingly they begin to force loyal Assad troops out of cities and towns where the uprising is gaining momentum.

Starting in January 2012 a new force enters the fray in Syria against the regime, a group called the Jabhat alNusra, or the AlNusra Front, loosely translated as Support Front. The organization stems from multiple roots. Firstly, during the fall of 2011 the Assad regime released many Salafists from prison in a general amnesty for rebels willing to renounce the uprising and pledge loyalty to the regime. Many of these former detainees take themselves straight to the front lines to fight against the regime that had imprisoned and tortured them. Some find their way to Iraq and link up with the Islamic State of Iraq. There they connect with Syrians that had entered Iraq in order to fight the American occupation forces, and group together under the leadership of Abu Muhammad alJawlani, a former detainee at Camp Bucca (at the same time as alBaghdadi) who was released in 2008 and promptly rejoined the Islamic State of Iraq. Jabhat alNusra also draws support from experienced foreign fighters coming into the country from places like Chechnya. They maintain a composition that is majority Syrian while allying with groups of foreign fighters. The decision will sow the seeds for some of the more complicated elements of the current situation.

As Jabhat al-Nusra is forming in Syria, and the Islamic State of Iraq becoming more and more involved in the Syrian conflict American forces complete their withdrawal from Iraq, with the final troops leaving on December 16th, 2011.

The withdrawal of American forces leads to an immediate increase in attacks, but it tapers off fairly quickly, with many of the attacks being confined to sectarian violence that does not threaten the Iraqi state in a serious way. Earlier that year there had been a somewhat subdued Arab Springinspired movement in Iraq, focused on problems of corruption and the failure of government services, but this movement was repressed and fizzled out quickly. Throughout 2012 the insurgency in Syria keeps expanding, with insurgents threatening to drive the government out of Aleppo and beginning to threaten Damascus itself. A series of high profile attacks is launched from inside the regime, including the poisoning of a Security Council meeting in the Presidential Palace and bombing of the National Security Bureau building in the Midan district of Damascus, which together eliminate almost half of the regime’s inner circle. As Assad’s military begins to wither away through defection and battlefield attrition, massive gaps in regime coverage began to open up, gaps which insurgent groups exploit in order to set up training and logistics hubs, while strengthening supply lines into Turkey and Lebanon. One such group is the Islamic State of Iraq, which begins to intervene directly in the conflict in eastern Syria by launching suicide attacks in support of assaults on regime military bases and military airports. This intervention creates internal conflict between AlQaeda affiliate organizations, with Jahbat alNusra chartered as the affiliate within Syria and the Islamic State of Iraq chartered as the Iraq affiliate. This conflict will soon come to a head, with profound consequences.

Two other dynamics of profound importance must be discussed. The first, and potentially most important in the current crisis, is the revival of the antiMaliki movement in December of 2012 in Anbar province, primarily in Ramadi and Fallujah, as well as in Tikrit and Mosul. As this conflict begins to gain momentum, with increasingly intense battles between demonstrators and the state, armed elements ally themselves with the demonstrators, defending camps and fighting back against the police and military, including reprisal attacks whenever demonstrators are killed by state forces. Prominent in this alliance are three groups that had some presence during the resistance to the US occupation, but which were largely marginalized in the context of sectarian violence. First among these is the General Military Council for Iraqi Revolutionaries, a coalition of armed groups and local tribal formations formed for the sole purpose of defending the antiMaliki demonstrations and camps against government action. The General Military Council allies with latent elements of the Baath Party regime, including the Men of the Naqshbandi Order, a Baathist Sufi organization, as well as some moderate Islamist organizations, such as the Islamic Army of Iraq. Alongside of these more formal organizations the increasingly armed struggle is joined by growing numbers of veterans of the Awakening groups. If we remember back to 2007 the Awakening groups were formed by civilians who had rejected the tactics of AlQaeda in Iraq, as well as former insurgents who had reconciled with the US occupation forces. As the US forces began to pull out Maliki largely violated the agreement with the Awakening groups, that they would be incorporated into the military in important ways. During his consolidation of control over the Iraqi military Maliki discarded this agreement, with many Awakening members arrested by his security forces, while others were either left out of the military entirely or relegated to low ranking positions in which they were commanded by politically loyal, militarily inept political operatives.

Between January and March of 2013 events in Iraq escalate quickly, with military units opening fire on demonstrators in Mosul and Fallujah and being forced out of both cities as a result. Security operations in both cities are undertaken by more lightly armed federal police units, and attempts to disperse demonstrations end for the time being in both cities.

Events in Syria also begin to take an ominous turn, with the Islamic State of Iraq taking control of more of northeast Syria. On April 8, 2013 the Islamic State of Iraq makes an announcement declaring that Jahbat al-Nusra had been a front organization, and that the two organizations had agreed to a merger, resulting in what we now know as ISIL. The following day Abu Muhammad alJawlani issues a statement denying the merger and accusing al-Baghdadi of attempting to forcibly take control of the Syrian conflict and the assets of Jahbat alNusra. This internal conflict leads to a split in both organizations, with a lot of the local Syrian members of ISIL defecting to Jahbat alNusra and many of the foreign fighters, mainly highly trained and experienced Chechens, joining ISIL. Ayman al-Zawahiri, who took control of Al-Qaeda after the death of Bin Laden, issues a ruling rejecting the merger. ISIL becomes increasingly isolated from Al-Qaeda, and instead takes on the role of a more extreme competitor. This split begins a string of ISIL

attacks on other insurgent organizations within Syria, including the assassination of military officers from Ahrar ashSham, a moderate Islamist insurgent group, and the Free Syrian Army. The internal crisis that ISIL created allows them to further carve out space in Syria from which to launch attacks and organize logistical capacity, pulling in increasing numbers of foreign fighters, including many from Europe and Northern Africa. Their numbers are bolstered through a bold attack on Abu Ghraib prison (the same prison where US soldiers took pictures of themselves torturing detainees) in which ISIL fighters penetrated numerous walls of the prison, and with the help of some sympathetic prison staff and a riot among the inmates, liberated hundreds of their fighters. Spirited off to eastern Syria, the newlyfreed combatants help seize the city of Raqqa, the largest city in Syria completely outside of regime control, from other insurgent groups, including Jahbat alNusra. All along the way ISIL seizes military bases, raiding rebel strongholds and checkpoints, while stockpiling weapons, ammunition and cash for an eventual return to Iraq.

Other developments from mid-2013 impacting the current crisis include the intervention of Hezbollah in Syria in support of the Assad regime, along with thousands of fighters from sectarian Shia militias, both jumping in at the behest of the Iranian government. By this point the Syrian military has been reduced to a smattering of highly trained forces supported by Russian and Iranian weapons, and backed by a number of informal militias organized among Syrian Shia communities and trained by commanders of the Iranian Basij Militia and the Revolutionary Guard. Hezbollah intervenes first by sending advisers, and then with the literal invasion of Syria, with an estimated 5,000 troops pouring over the border to take the city of Qusayr from the Free Syrian Army in May of 2013. This is accompanied by the intervention by Iraqi Shia militias Kata’ib Hizbollah and the Badr Brigades. This move literally saves the Assad regime from oblivion, but leaves it little more than a placeholder for Iranian and proxy force control, completely dependent on outside support for military and economic resources.

Meanwhile in Iraq, the military launches a renewed assault against entrenched protest camps in April 2013 in the west and northwest areas of the country, with the initial assault being in the city of Hawija. Over 50 demonstrators are shot by the military, a move which triggers escalating attacks, initially by the Naqshbandi Order, but soon involving more generalized armed action. On December 28 the military attempts to arrest a local Sunni MP in the city of Ramadi, generating mass demonstrations that lead special forces units under the direct command of the Prime Minister’s office to attempt to evict the protesters’ camp. The military kills 30 to 40 in the ensuing firefight and 40 members of Parliament resign in protest. The escalation of events in Iraq comes to collide with the increasing power that ISIL wields in the eastern areas of Syria. Due to an insurgent counterassault, ISIL’s operations in Syria are limited to areas immediately along the Iraqi border and the Euphrates River valley. Their control is reinforced by an unnegotiated mutual nonaggression pact forged with the Assad regime, allowing them to focus their attention on other insurgent groups, even pushing into the increasingly autonomous Kurdish regions in northeastern Syria. The Assad regime exploits this tacit agreement similarly. These trucelike conditions prevail until the ISIL returns to Iraq in strength. The relative autonomy ISIL enjoys in eastern Syria, combined with an influx of foreign fighters, the looting of resources from the cities under their control, and the hundreds liberated in the attack on Abu Ghraib strengthen the organization tremendously. This renewed strength leads ISIL to launch its first major assault into Iraq on January 2, 2014, with an attack on some police stations in Fallujah. This attack, carried out with the help of local tribesmen, quickly metastasizes throughout Anbar province. By January 8 ISIL and associated forces have driven the Iraqi military out of Fallujah, most of Ramadi, Karmah, Khalidiyah, Al Qaim and Abu Ghraib (the town where the prison is located), and are within striking distance of Baghdad. The Iraqi military launches a counterattack and drives insurgents out of most of the towns in Anbar province, but fails to take back Fallujah, setting the stage for the ISIL offensive of June 2.

The Current Situation and Its Misconceptions

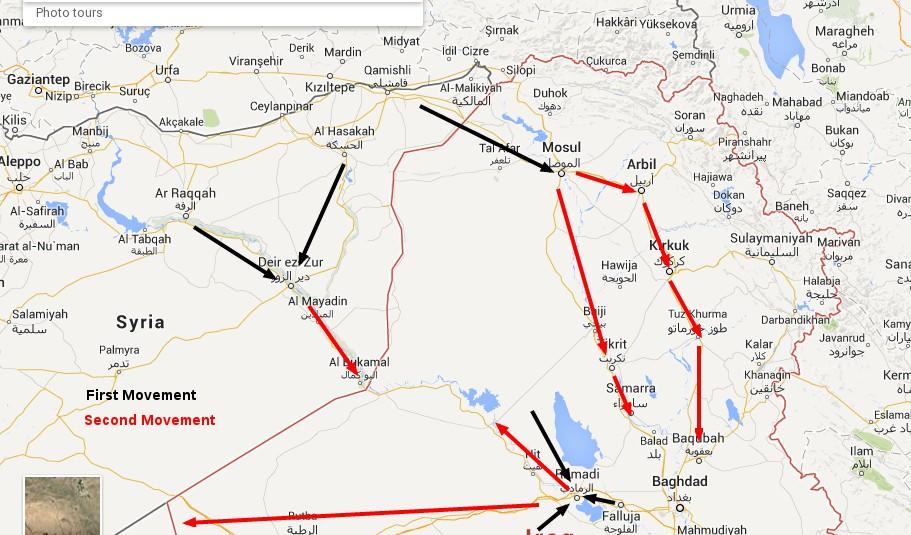

The June ISIL offensive moved into an area that was already experiencing localized resistance to the Maliki regime, along two primary routes. One route departed from the area around alBukamal in Syria, and areas in Anbar province west of Baghdad, into Ramadi and Fallujah. Having secured that route to Baghdad they moved back along the highways into Syria in order take alBukamal from the Free Syrian Army and threaten to take over Deir ez Zor. They also attacked the town of Haditha, fighting local tribes who have turned on ISIL as well as remnants of the Iraqi military that were there guarding a large dam on the Euphrates River. They have also since moved along highways to the west to take the town of Rutba and border crossings between Iraq and Jordan and Iraq and Syria. Their second route went from the northwest of Syria down through the city of Mosul. At this point the two main thrusts of the offensive split.

One line of movement went through Arbil and then Kirkuk, towns which were largely abandoned by Iraqi forces, and then occupied by Kurdish Peshmerga after ISIL moved on, and approached Baghdad from the north. The second line of movement went directly south from Mosul, through Tikrit and Sammara, cutting off Baghdad from the northwest.

The Iraqi military collapsed from internal lack of cohesion, lack of political will and general lack of support. Since the fall of Mosul in June the government has been attempting to launch a counterattack through three separate mechanisms.

Firstly, Shia militia that had been fighting in Syria, where they are a primary support pillar of the Assad regime, have been abandoning their posts and returning to Iraq. Many if these were well trained special units of the Iraqi military, who had been put on “leave” and deployed under the name of a militia, or veterans of Shia militias, such as the Mahdi Army and Kata’ib Hizbollah. Secondly, the government and many Shia militia organizations have launched specifically sectarian recruitment drives in order to bolster their respective ranks. Thirdly, they have been using special forces units that are commanded directly from the Prime Minister’s office, as discussed earlier. These forces have launched attacks into the areas to the north of Baghdad, and have been concentrating on Tikrit as of June 28. This has been complemented with the move of Kurdish Peshmerga forces to the south, in an attempt to occupy Kirkuk and Arbil.

Since the end of June the lines in Iraq have solidified and ISIL has shifted their attention back to Syria. This demonstrates an interesting feature of ISIL’s strategy that will be discussed later in more detail. They tend to avoid centers of gravity, and move into empty space, moving force very quickly, sometimes over hundreds of miles in a night, and shifting the kinetic axis in a completely different direction, against different enemies. This has allowed them to accomplish two different things. Firstly, it allows them to avoid the mass casualties that occupations of space tend to generate, especially when fighting against forces that have a profound advantage on the level of firepower and total air superiority. By avoiding the occupation of space, and leaving enough force behind to further destabilize space and mount defense, ISIL can hit weak points with force and speed, while depriving their opponents of the ability to counterattack. This dynamic was being facilitated by any number of organizations, outside of the ISIL chain of command and hostile to their project, but allied with them in the immediate goal of overthrowing Maliki, which actually occupy the spaces that ISIL largely moves through. This highly kinetic strategy has the side effect of overwhelming opposing forces, forcing them to capitulate, which means almost certain death in captivity, or defecting, which has been occurring more and more frequently, especially in eastern Syria. As these defections increase defensive forces can increasingly be left behind to hold territory. Secondly, in utilizing this form of kinetic strategy their opponents are deprived of the ability to mount a meaningful offensive. The opponent can move through space, but that means little, except that they have just stretched their supply lines out through potentially hostile terrain in which they are open to ambush. What they are never able to do is strike a decisive blow, or cause enough casualties to really cripple the organization. This is a temporary effect, but in the short term the sheer speed of ISIL’s movements means that opposing forces are kept perpetually off guard in a situation of total uncertainty. This has allowed ISIL to compensate for their lack of numbers, which even after defections was no more than 10,000 fighters, and their relative lack of firepower.

Except for some tanks and artillery recently captured from fleeing Iraqi forces they have been restricted to small arms, the mining of roads, and the use of car bombs, most of which are weapons that can only be used in close proximity to an enemy.

As the lines in Iraq have solidified and the rate of expansion in Syria has slowed ISIL is attempting to build long term viability. On the level of their own internal image and the external projection of this image they have declared, very publicly, the establishment of a caliphate, and have renamed themselves the Islamic State, with alBaghdadi making a public appearance in which he appealed for fighters from outside of the country to flood into their newly declared statelet. They have also begun to establish long term economic viability through the seizing of oil fields in both Iraq and Syria to sell oil on the black market, much of it to the Assad regime. Recent expansions have been aimed at establishing a foothold to take parts of both Aleppo and Baghdad. In Aleppo an interesting dynamic has been playing itself out. As rebel factions in Syria have had to devote more and more resources to fighting ISIL the Assad regime uses this opening to attack rebels in Aleppo, specifically to the north and west of the city where they have been attempting to reclaim assets for over a year. When rebels shift their focus to fighting Assad ISIL uses the opening to drive rebel factions, including Kurdish units, out of towns to the north and east of Aleppo. This strategy of encirclement is not only increasing defections as rebel units are cut off from supply lines and forced to surrender, but has also caused a profound crisis within rebel ranks within Aleppo, a city that they were poised to take over as recently as early May.

For a while it seemed as if the informal truce between the Assad regime and ISIL was collapsing, as the Syrian air force had begun to bomb ISIL targets in Raqqa, Syria as well as over the border into Iraq, likely under orders from their Iranian sponsors who are backing the Maliki regime. This brief lull in this truce has since ended, and it seems clear that if there is not overt cooperation between ISIL and the Assad regime, then there is at least a tacit agreement to leave one another alone to concentrate on their common enemy, Syrian rebels. As these moves are being made in Syria, ISIL units have begun to drive Iraqi troops, who are largely being devoted to launching attacks to the north and east of Baghdad, from towns to the south of Baghdad, specifically Mahmudiyah, which can be seen at the very bottom of the above map.

In the period since the initial assault on Iraq by ISIL attention in the international media has largely focused on the beheading of Western journalists and the attempted genocide on the Yazidi community in western Iraq, which prompted the initial wave of US air assaults. But, for as much as these events have grabbed the headlines this attention has obscured a more complex strategic dynamic that has fundamentally shifted the relationship of force on the edges of ISIL’s area of operations. Since midJuly ISIL has made tactical shifts in response to a form of tactical constriction. In response to incursions into Iraq, and the launching of ISIL attacks on Baghdad, mostly in the form of suicide bombings, the Iraqi military accelerated its process of rebuilding. As was mentioned earlier this rebuilding focused on the entrance of members of sectarian Shia militias into the formal Iraqi military, the collusion with these nonofficial Shia militias and the return of Shia fighters that had been fighting to support the Assad regime in Syria. As this newly formed Iraqi force organized and became active ISIL forces were pushed out of the area immediately around Baghdad and toward the north and west of the city, at which point it is reported that these Shia militias carried out a series of atrocities in order to remove Sunni populations from the towns that they had recently moved through, followed by the building of a dirt berm that currently forms the official front line.

In response ISIL began to focus its attention more on Syria, launching operations to take the oil fields in eastern Syria, as well as to push more into Kurdish controlled areas in northeast Syria. But, just as quickly as ISIL was able to take these oilfields and push into lightly defended areas of Syrian Kurdistan they began to run into more and more concentrated resistance from a combination of Kurdish forces and Syrian insurgent groups. It is this resistance, combined with the elimination of their ability to push closer to Baghdad that has created a fundamental tactical shift in the approach ISIL has taken to offensive operations. Up to this point ISIL’s strategy has centered around two dynamics, the movement into space that was either lightly defended or not defended at all, combined with the use of localized forces to facilitate movements through space, and the use of this movement to concentrate resources, both around immediate logistical requirements as well as longer term financial operations. This entire strategy relies on the ability to remain fluid, to move with speed and force, and a constant supply of resources, whether material or human, to continue to fuel this mobility. As their spaces of movement have become restricted this movement has not been able to continue in the same ways, and this has led to two specific shifts in operations.

The first shift that occurred is more of an expansion of the strategy ISIL attempted to deploy within Baghdad earlier in the summer. During this period of time the contraction of Iraqi military forces had concentrated around Baghdad, as retreating units returned to the city to regroup, and this eliminated the ability of ISIL forces to move smoothly through this space. At this point their disadvantage in magnitude of force, both numerically and on the level of weaponry, which was generally based in light arms and a limited amount of armored vehicles, combined to eliminate their forward movement into the capital. At this point ISIL began to send smaller units, often no more that 510 operatives, into the city to launch single attacks against military and police targets in an attempt to generate logistical chaos within Iraqi military forces that were already in a process of reorganization. These attacks had some effects, specifically forcing the city to be locked down almost entirely, further concentrating Iraqi military assets in the city and increasing the amount of open space available to move within. Throughout the end of the summer ISIL attempted a similar strategy in western Syria, specifically in the areas within the Qalamoun Mountains, bordering Lebanon, as well as within Lebanon itself. In early August ISIL cells attacked a police station in Arsal, Lebanon and kidnapped a number of Lebanese soldiers, provoking a Lebanese military attack on the mostly Sunni city, and hub for supplies to Syrian insurgent groups, as well as the adjoining Syrian refugee camp. As a result of this attack ISIL forces were expelled from Lebanon and the adjoining Qalamoun Mountains by Syrian insurgent groups, but this expulsion forced several forces adversarial to ISIL to shift forces to western Syria, including both Hezbollah, the Islamic Front, and the Free Syrian Army, opening up more space in eastern Syria, where ISIL forces are concentrated. In the wake of these attacks in Lebanon ISIL increased its operational pace in eastern Syria.

Far from a simple skirmish strategy this strategy seems to be based more in an approach that has long been used by Syrian insurgent groups against Assad regime forces, the coordination of attacks in an area far from an intended area of operations in order to pull enemy forces away from the area of future attack. Throughout the Syrian revolution insurgent forces have used this strategy. For example, during the Syrian government offensive into the Qalamoun Mountains during the fall of 2013 insurgent forces were able to entrap Assad forces by allowing them to move into an area and attacking behind them, cutting their command, control and supply lines, while at the same time launching offensive in other areas to draw supporting forces away from the area. After these counterassaults insurgents would routinely abandon the areas they had moved into, in favor of other areas that Assad forces could be drawn into. This strategy is not based so much in moving into and maintaining operations in an area, but rather to reconfigure the dynamics of force within an area to achieve a level of operational pace and strategic advantage. This is clear if we take a look at the use of this approach, one based in diversion and seizing the operational pace, as deployed by ISIL. It is not relevant to say that these approaches failed due to their failure to take Baghdad or Arsal, this was clearly not their purpose; if it were more forces would have been dedicated. Rather, what occurred in both areas was the commitment of a small number of forces that through a limited number of operations could have maximum tactical impact on the dynamic in a completely different area. In the attacks on Baghdad ISIL was able to force Iraqi military assets to concentrate in the city, drawing them away from the periphery where ISIL operates, while in Arsal they were able to draw both Syrian insurgent and Hezbollah forces away from eastern Syria, where ISIL was attempting to expand their area of operations. In both situations, after a very limited period of time ISIL ceased operations in these areas, to a large extent, and shifted their assets elsewhere.

The second and concurrent shift that has occurred is the beginning of large force contingent operations on a level that had not been seen up to this point, specifically in Raqqa and Deir ez Zor provinces in Syria, as well as Kurdish regions in eastern Syria along the Turkish border, especially in Kobani. Within Syria ISIL has been basing many of its main force operations out of Raqqa city, which sits along the Euphrates River, and has been attacking largely along the Euphrates River Valley. This pathway of movement has left large concentrations of Assad regime forces isolated and supplied primarily by airlift. With the constriction of ISIL lines of movement to the west of the Euphrates River Valley, with the exception of the deserts to the south of the valley, including numerous oilfields taken by ISIL over the summer, ISIL was forced into a position which necessitated the launching of concentrated assaults on these concentrated but isolated forces. These assaults began in early July with the attempt to expel insurgent factions from Deir Ez Zor city, which had been held by insurgent groups since 2011, and was surrounded by ISIL forces to the east and Assad regime forces to the west. As insurgent forces became isolated in the city, cut off from supplies, some defected to ISIL, while others fought their way out of the city, past the ring of Assad forces concentrated at the Deir ez Zor Military Airbase and into safe areas around Aleppo, to the west, allowing ISIL to capture the city on July 15 and creating a tense standoff between ISIL forces and Assad regime forces around the airbase in the west of the city[17].

What followed was a series of main force operations launched by ISIL, beginning with the launching of an assault on the Division 17 military base north of Raqqa on July 23, which was taken in a few days of concentrated assault. This was followed by an assault on the Tabqa Airbase immediately to the west of Raqqa by a strike force that included potentially thousands of ISIL troops. However, unlike prior ISIL assaults, which included a limited number of troops assaulting lightly defended areas, and unlike the assault on Division 17, which only took a few days to complete, the assault on Tabqa Airbase exacted a completely different toll on ISIL. The assault itself took around two weeks, beginning on August 9 and ending on August 24, to actually complete, involved at least three concentrated assaults on the base, and resulted in the death of around 400 ISIL fighters, by some reports, and much higher tolls by other reports, not counting the number that were wounded.

After the assault on Tabqa Airbase, which resulted in ISIL obtaining tanks and a large amount of small arms, they began an assault on the Deir ez Zor Military Airbase, an assault which has not been completed as of October 4. With the neutralization of Assad forces in both Deir ez Zor and Raqqa Provinces, and the concentration of insurgent forces to the west of Raqqa Province, around Aleppo and Hama, ISIL has begun to focus their operational force on the Kurdish areas to the north of the Euphrates River Valley with an assault on Kobani, which lies on the SyrianTurkish border.

Though these ISIL assaults have tended to be successful, and resulted in them obtaining a large amount of military resources, these assaults have generated two effects that have fundamentally changed ISIL military operations, and the structure of their movements. Firstly, as ISIL began its assaults earlier in the summer forces adversarial to ISIL began to concentrate their numbers and move into a defensive posture. This limited the lines of movement that ISIL could rely on, and forced them into these large scale frontal engagements. In these engagements ISIL took casualties that were far greater than forces that they were fighting within any single engagement, resulting in the loss of almost 1,000 fighters in the initial engagements and an untold number in their recent assaults on Kobani and the Deir ez Zor Military Airbase. The loss of fighters, combined with the necessity of concentrating forces for these engagements, has also slowed their operational pace dramatically, leading to a dynamic in which large amounts of resources are expended on assaults, resources which they may not be able to recoup. Up to this point the entirety of ISIL’s strategy has centered around fast movement and the obtaining of resources through this movement, and this has changed due to the compression effect that they generated through their early assaults. Secondly, ISIL forces had to begin to move in large groups, usually in convoys, making them easy targets from the sky, a dynamic that would become highly detrimental with the beginning of concentrated US air strikes within Syria on September 22.

This concentration of force has a series of profound impacts in ISIL political objectives and military operations.

Throughout the summer ISIL was dealing with a paradox. On the one hand they were attempting to launch assaults as quickly and as widely as possible, pushing small concentrations of adversarial forces out of areas, and allying with local forces in Iraq in their fight against the Maliki regime. But, this strategy, especially after the replacement of Maliki on August 24, became untenable. In order to function as a state, which is their ultimate political project, it is not enough to eliminate adversarial forces from an area, one must consolidate control over an area and police that space in all moments to the degree that this is logistically possible. This consolidation and policing of space requires forces to be inert in space, and in a sufficient saturation, which ISIL had attempted to achieve through deterrent actions. These deterrent actions however, generated resistance from localized groups, resulting in localized uprisings and demonstrations throughout the summer. This forces ISIL to face a choice, to either entrench and police space, limiting their area of operation and the speed of assault, or to continue to operate in a decentralized way, forming their strategy around mobility. In the compression effect that was generated by their early assaults this decision was somewhat made for them, and they were forced to concentrate forces for large assaults. However, this concentration of forces became a liability in the early days of US air strikes, in which convoys and centers of operation were targeted from the sky, resulting in a large number of casualties. Their vulnerability to air strikes has forced ISIL forces to redisperse, with many reports indicating that they have again decentralized command and control and have ceased large convoy movements, with the exception being the areas immediately outside of Kobani, where they are engaged in a large scale operation.

As the situation currently sits, in late October, there are a series of very open questions that exist in relation to the dynamics of ISIL operations. Firstly, and primarily, there is a tension that currently exists between ISIL political goals of organizing the state, and ISIL strategic imperatives, which requires dispersing forces. This situation has reemerged with the US air strikes, after a period of hiatus, but is the central tension in the project ISIL is attempting. Secondly, the ability to compensate for the effects of air strikes depends on whether ISIL can recruit enough forces to expand dispersed operations and to multiply the number of targets, which could potentially overwhelm the ability of air strikes to have much of an effect in the long run; this is the dynamic that occurred with the Taliban forces in Afghanistan, where force dispersal multiplied targets to such a degree that air strikes are often launched against individual vehicles or individuals, an approach that is not having much of an impact. It is the case that ISIL forces have expanded dramatically, from around 10,000 in July to as many as 37,000 in October, but this comes at a cost. With the rapid expansion of ISIL forces, combined with the large numbers of casualties that have been taken in recent large scale engagements the force quality of ISIL forces has diminished; many of the experienced fighters from the initial assaults have been killed or wounded, and have been replaced with largely inexperienced fighters. This decline in force quality is coupled with the increased stress that is placed on ISIL logistical capacity, the ability to command and supply a force that is many times greater than it was in the past, and the ability to maintain enough resource flow to make this possible.

It is this dynamic that is increasingly shaping the situation on the ground, and these dynamics that will likely become decisive in the long term.

Implications and Possible Scenarios

For as small a force as ISIL is on a practical scale, comparative to other forces in the region (e.g. the 100,000 troops of the Islamic Front networks in Syria), their actions have had profound implications in a very short period of time. This is partially a result of the tactics that ISIL has been deploying, and their ability to remain nebulous, fast and mobile, but also as a result of the speed in which opposing forces have folded in light of these movements. The rapid degradation of formal military forces in Iraq, and the threat that this has placed the Iraqi regime under, has recalibrated the entirety of the dynamic in that region, specifically in relation to the Syria conflict.

To understand this shift it is important to remember the blocs that are involved here, especially those in the Iranian sphere of influence. At the beginning of the Syrian revolution Iran sent military advisers there to attempt to support the Assad regime, train troops and organize informal forces, which are also a cornerstone of the repressive apparatus within Iran itself. At the same time they are attempting to support the Iraqi regime in similar ways, but at a lower level, largely through the training of parastate militias rather than direct aid. As the Assad regime began to lose control of the situation, and as the Syrian military evaporated through defections and losses due to combat with an increasingly armed resistance, the Quds Force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard made an important decision. Rather than fighting directly through the deployment of large numbers of troops, they would attempt to leverage their patronage of informal nonstate organizations, specifically Hezbollah and a number of sectarian Iraqi militias, to fight in Syria in support of the regime, and they would increase military and economic aid to the regime to keep these troops armed and the Syrian economy afloat. This began a process in which Iran, and by extension Hezbollah, would become increasingly drawn into an increasingly regional conflict, and the Iraqi militias would be caught in the middle, with some odd implications for the Assad regime.

As the Maliki[18] regime began to become destabilized, and as the Iraqi military collapsed in Mosul and Tikrit, the Quds Force was faced with a choice. On the one hand they needed to remain engaged in Syria, otherwise it would be likely that the regime would collapse quickly. On the other hand, if they did not shift force dramatically it was looking increasingly like the Maliki regime would collapse, and Iraq shares a long and porous border with Iran. As ISIL began to accelerate through Iraq the Iraqi militias that had been fighting in Syria began a mass exodus back to Iraq to support the Iraqi state, which led to a momentary surge in rebel movements within Syria. Hezbollah was then called on to commit thousands more troops, which increases their vulnerability within Lebanon. Not only have Hezbollah controlled areas been under a consistent barrage of reprisal attacks by Syrian rebel groups and allies within Lebanon, but the volume of casualties that they have suffered has already been in the thousands, including the loss of many high ranking, experienced commanders. These losses have eroded their political support within Lebanon as Shia families increasingly question why their children, who signed up to fight the Israelis, are dying in a war in Syria.[19]

Paradoxes have also begun to surface in relation to the tacit truce between Assad regime forces and ISIL. Early in ISIL’s Syrian incursion they directly fought regime forces, especially in Aleppo, where they controlled several neighborhoods.

But as conflict between rebel factions and ISIL accelerated and ISIL units were driven out of Aleppo and into eastern Syria a tacit truce took hold. The Syrian regime had, at that time, little presence outside of isolated cities in eastern Syria since early on in the revolution, with a presence in Deir ez Zor, Palymrya and a few bases scattered in the desert, all of which are largely supplied by helicopter. These small garrisons were more than content to allow ISIL to function in eastern Syria as long as they were fighting other rebel factions in the area. This tacit truce began to become more symbiotic when ISIL began to take over smaller oil fields and sell oil to the regime, which had been under international sanctions for some time. This began to create a problem, however, when ISIL began to focus their operational capacity on carrying out attacks in Iraq, leading to a phenomena that had not been seen in over a year, a Syrian air force strike on an ISIL target, a headquarters building in Raqqa. After this attack Assad regime forces, which had been besieging rebel troops in Deir ez Zor from one side, while ISIL cut them off from the opposite side, began to be attacked by ISIL units, at the same time that Iraqi militias were abandoning their positions within Syria to return to Iraq; since this initial bombing all of these regime held areas in Eastern Syria, with the exception of the garrison in Deir ez Zor, has fallen to ISIL forces. This generates a profound problem for the alliance that has built up within the Iranian sphere of influence.

The Syrian regime is reliant on ISIL, not only for some of their oil supply, but also to divert their enemies, yet ISIL is also attacking their sponsors and support organizations. This could lead to any of a number of scenarios, but the most likely at this point is that the Assad regime will abandon the eastern deserts, which had already begun to happen as of early July, and allow ISIL free reign so they can concentrate their forces around Aleppo, creating a pincer in northern central Syria with the potential to generate serious problems for rebel factions in the area. This also means that the Assad regime is tacitly consenting, for the time being, to allowing ISIL to base operations out of eastern Syria, essentially securing ISIL’s rear flank so they can concentrate on operations in Iraq. At the same time Assad is acknowledging that his regime’s area of operations has just shrunk dramatically. The Assad regime is essentially preserving its ability to survive in the short term, and in the process has sacrificed the Maliki regime, although that collapse may have been unavoidable. The real question is whether this completely fragments this bloc or not.