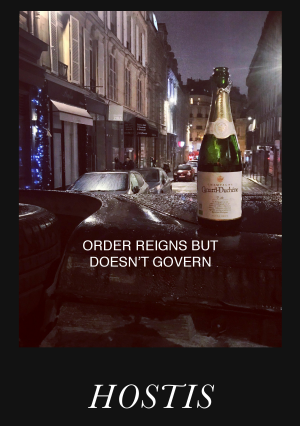

Hostis

Order Reigns But Doesn’t Govern

The burning down of Minneapolis PD’s 3rd precinct; the subsequent national poll that reported 54% of the US population’s assessment of insurrectionary violence as a legitimate response to the murder of George Floyd; the fact that insurrectionary violence garnered more support than that of any elected president in recent memory; the various instances of militant eviction defense replete with novel forms of conflict infrastructure; the legal support and networks of solidarity established for every comrade arrested; the unapologetic composition of our very own “hot summer” as black/non-black poc and its disregard for legality; the week where the world learned of Trump’s positive covid test; the week where the world learned of Boris Johnson’s positive covid test, and of Bolsonaro’s, and Macron’s, and so on...

As incomplete of a summary as this may be, what can be said of a political sequence wherein a disparate set of events such as these come to serve as its inflection points?

They are, if anything, the serial expression of a collective desire for bringing about an end to this world. A collective desire whose content is not the restoration of dignified estrangement, but rather the termination of everything that forces us to be strangers to ourselves, our friends, comrades, and to the world. Unlike the “parties of Order” whose utopias are the fever dreams of the present; or the “progressive” Party’s that are nothing but the Left-wing of capital and tempt us with a world where all activity is validated as essential work; our utopias can be, tentatively, said to be utopias of rest. These are utopias whose destructive character is defined, not by the feeling that we are all essential workers, but by the feeling that labour is simply not worth the trouble. If it helps to use the language of the present, these utopias of rest show themselves to be destituent ones. These are non-worlds where the “strength of hatred in Marx” and the “fighting spirit of the dispossessed” coincide; where there is no longer any need for either fear or hope, but only the search for new weapons. And because these are of a destructive kind, they are utopias without interest or patience for any discourse on the universal. Rather, they are proposals for an everyday life that belongs to no world in particular precisely because they are, themselves, rich with the particular. For what else would it mean to be a partisan if not taking sides? If not participating in the defense of the Particular? As the saying goes: those who talk about revolution and class struggle without referring to everyday reality have a corpse in their mouth.

— Hostis, December 2020