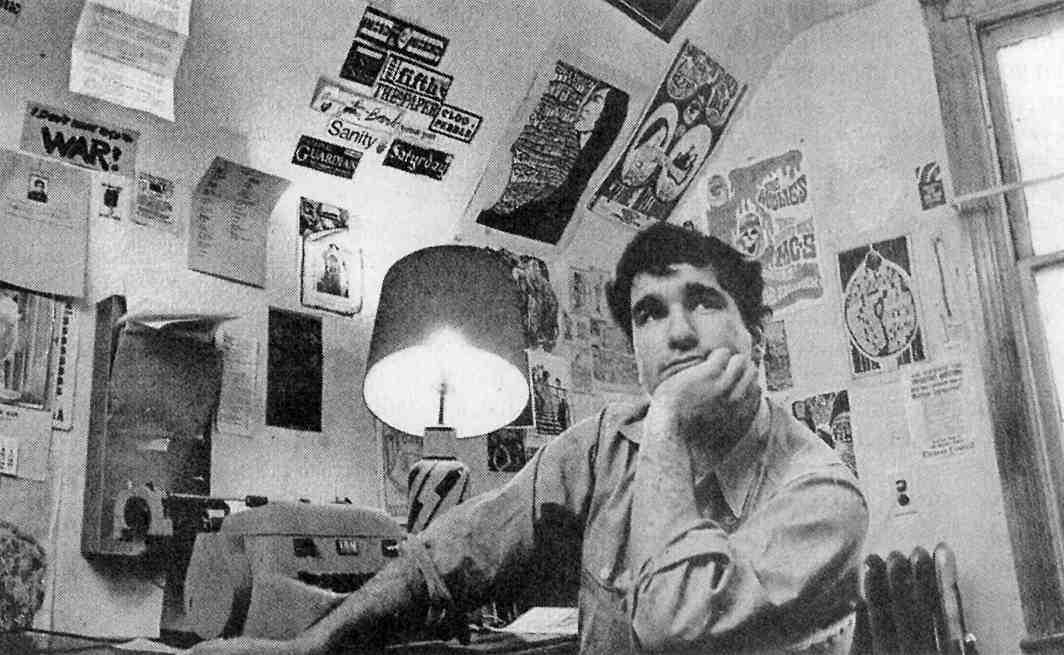

Harvey Ovshinsky

The story behind Detroit's long-lasting underground newspaper

In November 1965, Harvey Ovshinsky was 17 and a recent graduate of Mumford High School when he started the Fifth Estate, one of the nation's earliest underground papers. Ovshinsky, now 73 and a resident of Ann Arbor, went on to become an award-winning filmmaker and multimedia journalist. The Fifth Estate, unlike virtually every alternative publication from that era, survives 56 years later as an anarchist quarterly. In this edited excerpt from his memoir, "Scratching the Surface: Adventures in Storytelling," published by Wayne State University Press, Ovshinsky recalls the paper's birth.

* * *

It was not the reunion I expected. When I returned to Mumford after my brief stint working for the Los Angeles Free Press, widely considered the nation's first underground newspaper, I pitched my former classmates on the idea of helping me launch my own paper. My friends were eager to lend a hand, but were confused. Start your own newspaper? Who does that?

I understood the problem: in the early1960s, front-page news reports about teenagers and Black people were infrequent in The Detroit News and Detroit Free Press unless they were in trouble. Prominent stories about the civil rights and the burgeoning peace movements were all but invisible, and articles about women's issues were often quarantined to the society or features sections.

What to do? As eager as I was to publish my alternative newspaper, first I had to come up with some alternative news.

I began by knocking on the doors of the area's most prominent civil rights and antiwar organizations. The executive director of the Michigan chapter of the ACLU was extremely receptive, not only offering to supply stories for the paper but also subscribing on the spot. Other activists weren't sure what to make of my plans, but they were eager for the opportunity to have a newspaper, any newspaper, that would print their press releases instead of simply tossing them in the wastebasket.

Unfortunately, not everyone was as eager to support our efforts.

The Fifth Estate's first issue was delayed by several weeks when our printer refused to print our layout sheets because of what he called "unpatriotic" content. The front-page Jules Feiffer cartoon ridiculing America's leaders wasn't the problem. The printer's primary objection was a political cartoon on page two that portrayed an American flag with rifles and bayonets in place of the stripes.

"We don't print treason," he announced proudly.

I tried not to be discouraged, but in 1965, finding someone to print the first issue of a "treasonous" newspaper like the Fifth Estate was like trying to pin down a priest or a rabbi to marry a "mixed" religious couple. Finally, the Rev. Albert Cleage Jr., the Black Nationalist minister, and his brother, Henry, who published their own radical newspaper, Illustrated News, agreed to support our cause. The Fifth Estate was born.

In addition to Feiffer's wry rant, the first issue featured news of the mistreatment of civil rights activists in Mississippi, a condemnation by the Michigan ACLU of a plan by Selective Service in the state to punish draft protesters and the announcement of the formation in Detroit of a group for people who considered themselves part of the "independent left."

The lead story was a review of a Bob Dylan concert at Masonic Temple. Steve Simons, a fellow Mumford Mustang, loved Dylan but was confused by his "wielding an electric guitar surrounded by a rock and roll combo. Now Bob Dylan feels like he can 'make it' in rock and roll," Steve wrote. "Perhaps he can."

Oh well, we were journalists; we never said we were prophets.

Fortunately, it wasn't only our music reviews that stood out. Years later, I told Detroit Free Press columnist Desiree Cooper that I believed the mainstream media was like a hand mirror that only showed part of the body, whereas underground alternative papers like the Fifth Estate insisted,—No, there's more!' We were like this full-length mirror that wanted to see and show everything."

Inevitably, the paper found itself under attack from what my partner and co-editor, Peter Werbe, eventually came to call the "Four Ps"—parents, police, principals and priests—who were often horrified by the paper's irreverent content and radical politics.

"It's so foul. I can't hold it up for display," a Royal Oak city commissioner later said of the paper, when he tried to close a local head shop for selling the Fifth Estate.

As proud as I was of the Fifth Estate, the first issue was a flawed masterpiece. For one thing, each copy came with two blank pages. No one ever told me that when you lay out six pages of copy, tabloid newspapers can only print four pages at a time.

Still, we managed to impress. Wayne State University's Daily Collegian wrote a glowing review, inviting readers to "look for something different in newspapers. Like to see topics treated from a new angle?" asked the article. "You might want to take a look at the Fifth Estate, a Collegian-size paper and a product of a university freshman, Harvey Ovshinsky...an angry young man lashing out at established institutions and the status quo."

The article helped, not just because it made me look the way I felt, but also because of the several new subscriptions we received from curious students and faculty members. "Good luck with your newspaper," one new subscriber wrote. "I'm enclosing a check to help pay for a dictionary. I'm no journalist but I do know the word publicity has two 'i's in it, not just one."

I've always been proud of having started the paper so young, but by the second issue, my youth and inexperience were starting to show. Playboy, reporting on the underground press, slammed it as a "hick cut-and-paste job of pilfered materials."

That hurt. What if my mother was right after all: Instead of starting my own literary magazine at Mumford, I should have "buckled down" and joined the staff of a real magazine like the school's official literary magazine, the Muse. Or a real newspaper like the Mumford Mercury.

Maybe, probably, but then I took heart from a lesson I learned from my scientist/inventor father, Stan Ovshinsky. During one of our many visits to Greenfield Village's re-creation of Edison's Menlo Park laboratory, Dad reminded my brothers and me that for every one of Edison's early lightbulbs that worked, there were hundreds, even thousands, that didn't.

At the time, I thought my father was talking about Edison. Years later, when I imagined he was thinking of his own failed experiments, he dismissed the very idea: "That's not how it works, Harvey. In science, there's no such thing as a failed experiment."

And he was right, as the nation's "straight" press was soon to discover. "Shoestring papers of the strident left are popping up like weeds across the US," wrote Time magazine in 1966. "Their editors, writers and subscribers represent a curious coalition of hipsters, beatniks, college students and teachers and the just plain artsy-craftsy."

A half-century later, the hipsters and beatniks are long gone but the Fifth Estate, now a quarterly magazine, continues to provide a new generation of counterculturalists with a radical take on such timely topics as the environment, technology, the state of our civilization and the far right's threat to American pluralism and democracy.

I remember well when the Jefferson Airplane's Paul Kantner once famously said, "If you can remember anything about the '60s, you weren't really there." Not true. The fearless Fifth Estate was there.

And still is.

Photo caption: Harvey Ovshinsky in his childhood bedroom in the 1960s. Tony Spina/Detroit Free Press