G. Jewell

The IWW in Canada

General Introduction

Established in 1886, the American Federation of Labor had by the turn of the century secured its domination over North American organized labour. True, the federation was still a shaky affair; the AFL — interested primarily in “respectable” craft unions — refused to organize the great bulk of industrial workers. But with the Knights of Labor (the first genuine, albeit mystical attempt to bring all workers together under one all-embracing organization) everything but buried, and industrial unions like the American Railway Union destroyed and the Western Federation of Miners under increasing attack by the mine owners, the AFL managed to establish hegemony and either batter down or absorb all rivals.

This craft union hegemony existed in Canada as well as the United States. The original Canadian unions — insular and indecisive — failed. The same fate met the first mass- industrial union from the U.S., the Knights. In 1902, the Trades and Labour Congress, already the leading force in Canadian labour and controlled by the AFL union branches in Canada, expelled from its ranks all Canadian national unions, British internationals, and the Knights of Labor. The opposition formed a Canadian Federation of Labour (CFL) but it never amounted to much. Prospects seemed clear for the TLC and, behind it, Samuel Gompers, U.S. president of the AFL.

Yet only three years were to pass before the IWW emerged as a revolutionary challenge.

Birth of the IWW

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was founded in 1905 in Chicago. The driving force behind the new union was the Western Federation of Miners, which had been fighting a bloody but losing battle throughout the western US and Canada. Joining were the WFM’s parent, the American Labor Union (which included several hundred members in B.C) the United Brotherhood of Railway Employees, and Daniel DeLeon’s Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance. Observers were sent from the United Metal Workers (US and Canada), the North American branch of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers of Great Britain, the International Musicians Union, the Bakers Union, and others.

Keynote speeches were delivered by Big Bill Haywood of the WFM, Eugene Debs of the Socialist Party, Mother Jones of the United Mine Workers, DeLeon, Lucy Parsons, anarchist and widow of a Haymarket martyr, Father Hagerty, who drew up the One Big Union industrial structure, and William Trautmann from German Brewery Workers of Milwaukee (who was expelled from that union for his participation in the IWW convention). Trautmann’s and Hagerty’s views were influenced by European anarcho-syndicalism, as were Haywood’s by the revolutionary syndicalism of the French CGT. A claimed membership of 50,827 was pledged to the IWW. The professed aim was nothing less than the overthrow of the capitalist system by and for the working class.

Two months later, after the United Metal Workers brought in 700 of their claimed 3,000 members, the actual total of union members was a mere 4,247. There was a magnificent $817.59 in the treasury. The new union had begun to march on the wrong foot and the AFL crowed with delight. Within a few years all the founding organizations had either quit the IWW or had been expelled. By 1910, a low year with only 9,100 dues-paid members, the IWW was the unruly bastard of the labor movement, ridiculously challenging the AFL and the Capitalist Class to a battle to the death.

However, the IWW then suddenly burst out with an amazing explosive force, becoming a mass movement in the US, Canada, Australia, and Chile, and leaving a fiery mark on labour in South Africa, Argentina, Mexico, Peru, Great Britain and the world maritime industry.

The reasons for this sudden expansion lay at the very root of the economic crisis underlying capitalist society in the years immediately prior to the First World War. To begin with, organized labour, divided as it was into squabbling craft unions, was in a pitiful state, unable to effect even the most innocuous reforms. The larger mass of unorganized and chronically under-employed workers lived in appalling misery as it reeled from a capitalist “boom and bust” cycle of high speculation followed by crushing depression every five or ten years.

Yet despite this seemingly tremendous weakness of the working class, many unionists had already recognized the great power inherent in the vast industrial monopolies which the ever-shrinking number of super-industrialists themselves scarcely knew how to handle. That a working class already trained in the operating of these industries might continue to do so in the enforced absence of the capitalist owners was a matter of new-found faith and high expectations. At this particular moment, it was precisely the IWW which gave not only voice to these hopes and desires, but also offered the first INDUSTRIAL strategy to effect that transference of power.

The IWW, cutting across all craft lines, organized workers into industrial unions — so that no matter the task, all workers in one industry belonged to one industrial union. These industrial unions formed the component parts of six industrial departments: 1-Agriculture, Land, Fisheries and Water Products, 2-Mining, 3-Construction, 4-Manufacturing and General Production, 5-Transportation and Communication, and 6-Public Service. The industrial departments made up the IWW as a whole; yet although functioning independently, they were bridged by the rank and file power of the total general membership to vote on all union general policy and the election of all officers of the General Administration coordinating the industrial departments.

The IWW was characterized by a syndicalist reliance on the job branch at the shop floor level; a strong distrust of labour bureaucrats and leftist politicians; an emphasis on direct action and the propaganda of the deed. Above all, Wobblies believed in the invincibility of the General Strike, which to them meant nothing less than the ultimate lock-out of the capitalist class. They wrapped their theory and practise with a loose blanket of Marxist economic analysis and called for the abolition of the wage system.

The IWW pioneered the on the job strike, mass sit-downs, and the organization of unemployed, migrant, and immigrant working people. It captured the public imagination with free speech fights, gigantic labour pageants, and the most suicidal bluster imaginable. Its permanent features were an army of roving agitator-organizers on land and sea, little red song books, boxcar delegates, singing recruiters.

In Australia IWW members were involved in a plan to forge banknotes and bankrupt the state. During the Mexican revolution of 1911, Wobblies joined with Mexican anarchists in a military effort that set up a six-month red flag commune in Baja California. In the Don Basin they faced Cossacks; at Kronstadt they died under Trotsky’s treacherous guns; in the German ports they were silenced only by the Gestapo; in the CNT anarchist militias and the International Brigades they battled Franco.

Canada 1906 – 1918

The IWW immediately began organizing in Canada, and experienced erratic growth from 1906 to 1914, especially in B.C. and Alberta. The first Canadian IWW union charter was issued May 5, 1906 to the Vancouver Industrial Mixed Union No.322.

Five locals were formed in BC in 1906, including a Lumber Handlers Job Branch on the Vancouver docks composed mainly of North Vancouver Indians, known as the “Bows and Arrows.”

By 1911, the IWW claimed 10,000 members in Canada, notably in mining, logging, Alberta agriculture, longshoring and the textile industry. That year a local of IWW street labourers in Prince Rupert struck, initially bringing out 250 but swelling to 1,000 assorted strikers. 56 arrests resulted from several riots, and a special stockade was built to house them (reportedly by TLC union carpenters). A number of strikers were injured and wounded; the HMS Rainbow was called in to suppress the strike.

In 1912 the IWW fought a fierce free speech fight in Vancouver, forcing the city to rescind a ban on public street meetings.

Organizing began in 1911 among construction workers building the Canadian Northern Railway in BC. In September a quick strike of 900 workers halted 100 miles of construction. IWW organizer Biscay was kidnapped by the authorities and charged as a “dangerous character and a menace to public safety.” A threatened walkout by the entire Canadian Northern workforce prompted a not-guilty verdict in a speedy trial. In December, a 50-cents a day pay raise was won by on-the-job action.

The 1,000- Mile Picket Line

By February 1912, IWW membership on the CN stood at 8,000. A demand for adequate sanitation and an end to piece-rate or “gypo” wages was ignored by the government. On March 27, unable to further tolerate the unbearable living conditions in the work camps, the 8,000 “dynos and dirthands” walked out. The strike extended over 400 miles of territory, but the IWW established a “1,000-mile picket line” as Wobs picketed employment offices in Vancouver, Seattle, Tacoma, San Francisco, and Minneapolis to halt recruitment of scabs.

Meanwhile the strike camps were so well run and disciplined that the press began calling the Yale camp in particular a “miniature socialist republic.” While not going that far, the west coast IWW weekly, Industrial Worker, proudly pointed to this example of working class solidarity in which Canadians, Americans, Italians, Austrians, Swedes, Norwegians, French and other countrymen — one huge melting pot into which creed, colour, flag, religion, language and all other differences had been flung — were welded together in common effort. Even “demon rum” was proscribed, which alone indicates the seriousness of the strikers.

Authorities arrested the strikers by the thousands for “unlawful assemblage” and vagrancy. Many were forcibly deported at gunpoint. But the picket lines held. In August they were joined by 3,000 construction workers on the Grand Trunk Pacific in BC and Alberta. The entire action, better known as the Fraser River or Fraser Canyon Strike, was popularized in song by Joe Hill’s “Where the Fraser River Flows.” The strike also spawned the nickname Wobbly. A Chinese restaurant keeper who fed strikers reputedly mispronounced “IWW” in asking customers “Are you eye wobble wobble?” and the name stuck.

The CN strike lasted until the fall of 1912, when exhausted strikers settled for a few minor improvements: better sanitary conditions and a temporary end to the gypo system. The BC Grand Trunk strike was called off in January 1913 after the Dominion government promised to enforce sanitation laws. A greater gain was development of the “camp delegate” system in which the IWW secretary in town delegated a worker to represent him in the field — a method later refined into the permanent “Job Delegate” system of the roving Agricultural Workers.

Other unique features of the strike are worth mentioning. One, used again in the 20’s on the Northern Railway strike in Washington, was to “scab on the job” by sending convert Wobs into scab camps to bring the workers out on strike. Another came in response to the “free” transportation offered scabs by the Railways on condition a man’s luggage was impounded until such time as his strike breaking wages repaid the fare. Large Wob contingents signed on, leaving the Railways with cheap suitcases stuffed with bricks and gunny sacks, and then deserted en route.

Edmonton, Alberta was then a major railroad construction center and in the winter of 1913- 14, thousands of workers from all over Canada and the US were stranded there without jobs or funds. The city fathers refused to alleviate their plight. The IWW established an Edmonton Unemployed League, demanding that the city furnish work to everybody regardless of race, colour or nationality, at a rate of 30 cents an hour, and further, that in the meantime the city distribute three 25-cent meal tickets to each man daily, tickets redeemable at any restaurant in town. These demands were backed by mass parades which police clubs and arrests could not stop.

On January 28, 1914 the Edmonton Journal headlined the news: IWW Triumphant! The city council provided a large hall for the homeless, passed out three 25-cent meal tickets to each man daily, and employed 400 people on a public project.

That summer the IWW began organizing a campaign in the Alberta wheat fields, but the guns of August were drawing near.

Repression in W.W.I

With the outbreak of World War one and Canada’s subservient entry as British cannon fodder, the federal government effected a number of articles in the War Measures legislation embodied in the British North America Act. IWW members were hit by a wave of harassment and arrests that presaged that which swept most of the American IWW leadership into jail in 1917–18 (by 1920 there were 2,000 Wobblies behind bars in the USA). In late 1914 the union could claim only 465 members in Canada and in 1915 its last three remaining branches dissolved. Agitation continued, however, especially among Finnish lumber workers in Northern Ontario.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 caused severe jitters in the ruling classes around the world and with the unilateral withdrawal of Russian forces from the war effort against Germany, the conflict in Europe reached a critical stage. This was coupled with a number of mutinies in the Allied forces and weary dissension on the homefronts. Repression was intensified and Canada a number of Wobblies were jailed in 1918. The “Vancouver World” of August 5, 1918 outlined the “facts” in the case of Ernest Lindberg and George Thompson:

Two IWW Prospects Caught in Police Trap-- Couple Declared Active at Logging Camps Arrested and German Literature is Seized... “Lot of Good Rebels Quitting, stated letter...Message in German to Tenant of House is postmarked Glissen. Lindberg, accused of delivering speeches in a logging bunkhouse, after which a number of workers quit their jobs and returned into the city, was held under the Idlers Act. Thompson, who is alleged to be a firebrand and whose connection with the pro-German element is said to be close, was charged with having banned literature in his possession, including copies of the Week, LaFollette’s Magazine (LaFollette: anti-war Progressive US Senator), and of the Lumber Worker, as well as letters written in German.

The World went on to editorialize:

** For some time past the Dominion authorities have been alive to the situation existing in the camps, and have been desirous that the ringleaders of the movement which is responsible for draining of the logging centres, should be found... By the arrest of Lindberg and Thompson, the authorities believe they have succeeded in locating two main workers in the IWW cause, although there are others who will be carefully watched and apprehended in due course... The IWW is the short term used for the Industrial Workers of the World, an American organization with very extreme policies, Bolsheviki principles, and far reaching aims for the betterment of the conditions of the masses. Like other large organizations, it has two factions, the red flagging element generally regarded as dangerous as inciters against the observance of law and order. The organization is disowned by all but the lowest type of union labour men, as well as by Socialists.***

On September 24, 1918, a federal order in council declared that while Canada was engaged in war, 14 organizations were to be considered unlawful, including the IWW and the Workers International Industrial Union (DeLeons’ expelled Detroit faction of the IWW).. Penalty for membership was set at 5 years in prison.

The same order banned meetings conducted in the language of any enemy country (German, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Turkish etc) or in Russian, Ukrainian or Finnish (except for religious services.)

IWW organizer Dick Higgins was tried under the War Measures Act in Vancouver, but a defense by the Socialist Party of Canada kept him out of jail. In the USA, two of those receiving minor sentences were well known British Columbia unionists who had been temporarily organizing in the USA, as headlined in the B.C. Federationist September 1918: IWW Members Given Long Terms: G. Hardy and A.E.Sloper are among those who received year terms.

Postwar Growth

1918 witnessed a major change in Canadian Labour. The drive for industrial unionism resumed and stiffened resistance against the AFL affiliated TLC and the latter’s support for conscription and the suspension of civil liberties.

This groundswell culminated in the founding of the One Big Union at the Western Labour Conference in Calgary in March 1919. Directly affiliated to the OBU were a number of independent mining and lumber industrial unions, but its influence reached into a majority of TLC locals west of Port Arthur, Ontario. This explosive mix of militant independent unionists and rebellious TLC units resulted in the Winnipeg General Strike that summer. It began with the building trades striking for recognition, followed by the metal trades, and on until 30,000 workers were out directly or in sympathy and a Central Strike Committee was running the city. Fred Tipping, a member of the Strike Committee, explains the situation:

First of all, you should remember that there were a series of unsuccessful strikes through 1918. In a sense the 1919 strike was a climax to many months of labour unrest due to a great deal of unemployment after the War, big increases in prices and no job security. Bear in mind too that Winnipeg and Vancouver were centres of advanced radical thought at the time. The Socialist Party of Canada/Marxist had been strong for a number of years and had gained support among industrial workers and even farmers. In the Winnipeg Trades and labour Council you would find men who were Marxists and others who supported the IWW. There was also the Social Democratic Party, many of these people were strong enthusiasts for the Russian revolution and were commonly called Bolsheviki. When the Social Democrats split during the War some of these later joined the Communist parties. Others of us became members of the Labour Party — later to become the Independent Labour Party and then the CCF. The idea of the general strike seemed to have been in the air. Don’t forget that not too many months before, some key people on the Strike Committee had attended the OBU conference in Calgary and the general strike was a weapon much favoured by the OBU. Then there was the attitude of business. They were first generation businessmen. I call them Ontario bushmen. Most of them had been farmers. They felt paternalistic to the workers. “I don’t want a bunch of workers telling me how to run my plant,” was a remark commonly heard. On the other hand the union leaders had come from industrial England. They had years of bitter strike experience. They were not novices

---- Canadian Dimension/Winnipeg----

The strike was smashed by a combination of government troops and a “Citizens committee.” Many strike leaders were arrested and tried for subversion. A number of immigrants were deported. The OBU was shattered as an all-industry federation as court after court ruled that the TLC “internationals” owned the contracts in the majority of organized locals, though the OBU continued to hold the Lumber Workers Industrial Union, some mine unions, the Winnipeg streetcar workers, and Saskatoon telephone operators.

After a series of disastrous strikes by its 23,000 members, the LWIU collapsed in 1921. Stepping into the breach, the newly founded Workers Party — later the Communist Party-- declared war on the OBU’s industrial unionism and succeeded in directing it into “geographical unionism,” following the dictate of Lenin’s 3rd International union strategy, which was to break up dual or independent unions and bring them into locals affiliated with the AFL, which the Communists hoped to capture from within. By the mid-twenties, the Communist TUEL had captured about a third of the important union positions in the AFL, but were purged overnight by a counter-coup of the Gompers faction.

The Communists were aided in the move for geographical unionism by some syndicalists, especially in Edmonton, who had moved toward that defensive concept in the period of the OBU”s decline. In BC, the Communists managed to get many of the lumberworkers “east of the hump’ into the AFL Carpenters union.

AT the same time, however, the IWW was reorganizing in Canada. In 1916, virtually extinct in the rest of the country, the IWW had moved from the Minnesota iron fields in the Mesaba Range northward into Ontario and had gained a large following in the northern woods, especially among Finnish Lumber workers. After the orders in council outlawing the IWW in 1918, organizers went underground. In 1919 the Ontario lumber workers joined the OBU, but Wobbly delegates continued to bootleg union supplies to the minority who wanted to keep their IWW membership books as well, as well as did OBU-IWW delegates in B.C. On April 2, 1919 the ban on the IWW was lifted. Two branches were formed in Toronto and Kitchener.

Organizing in the 20’s

An exchange of union cards was arranged between the IWW and the OBU locals still functioning in the lumber fields, seaports and Great Lakes. This exchange was a system in which separate unions recognized as valid the union cards of workers transferring into their own jurisdiction from that of the other union and required no initiation fee. an OBU an d IWW delegate travelled together to the 1921 Red International of Labour Unions conference in Moscow. The obu delegate, Gordon Cascaden, was denied a vote because he represented the “anarchist wing “of the OBU.

The IWW delegate, who originally supported ties the RILU, argued against affiliation on his return.... Among the ultimatums RILU attempted to impose... was that the IWW affiliate the virtually defunct Lumber Workers Industrial Union/OBU in Western Canada, already permeated by Communists.

Following the collapse that year of the LWIU, the IWW, OBU and the Communists all made bids for the former members. Some sections joined the Communist Red International (a way station to the AFL Carpenters) others made an abortive attempt to revive the LWIU, which still had support in the east. The remainder joined IWW. largest section being the Vancouver LWIU branch, which had revolted when LWIU joined the Communists. By 1923 IWW had three branches with job control in Canada: Lumberworkers IU 120 and Marine Transport Workers IU 510 in Vancouver and an LWIU branch in Cranbrook BC for a total of 5,600 members.

Organizing in the 20’s was extremely difficult. The defeat of the Winnipeg General Strike and the depression of the early part of the decade weakened unions everywhere. During 1921 and 1922 the usual cause of strikes was resistance to wage reductions. Most such disputes were won by the employers. A large number of strikes were smashed by scabs drawn from a vast pool of new workers migrating from the farms to the cities.

Nonetheless, 1924 marked a peak year for the IWW in Canada. This was in direct contra distinction to the US IWW, which underwent a disastrous split over the questions of decentralization and amnesty for IWW prisoners in federal prisons (the decentralists demanded total autonomy of all industrial unions, with no central clearing house or headquarters dues. The anti-amnesty faction called for a boycott on any federal amnesty., instead relying on class struggle to win the release of imprisoned Wobblies).

The split in the US IWW puzzled the Canadian membership, who decided to support the Constitutional IWW in Chicago instead of the decentralist Emergency Program IWW in the West — the latter lasted for ten years; the resulting raids and counter-raids destroyed IWW power in the western lumber fields and caused a temporary membership drop nationwide.

In Northern Ontario the Canadian Lumber Workers (the OBU remnant of the LWIU) voted in 1924 to bolt the geographically based OBU and join the IWW. The same referendum elected a Finnish lumberworker, Nick Vita, as secretary. Vita had joined the IWW in 1917 and secretly carried an IWW red card through the War Measures Act and his years in the OBU. In 1919 he had attended the IWW Work People’s College and then Ferris Institute, a business college in Michigan, after a meagre three months of school before adulthood.

Vita’s first chore as secretary was to issue 8,000 IWW union cards. Branches were set up in Sudbury — Ontario head office — and Port Arthur. Vita began organizing railroad workers and miners in Timmins and Sudbury districts, but a brief success of 3,000 recruits soon faded. That same year an Agricultural Workers Organization IU 110, was formed in Calgary. Four IWW organizers were arrested on charges of vagrancy. IWW headquarters in Chicago provided legal fees and three of the cases the charges were quashed. On January 1, 1924, after the firing of an IWW member of the Cranbrook BC branch IWW Lumber Workers IU120 struck the lumber owners, calling for an 8 hour day with blankets supplied, minimum wage of $4 per day, release of all class war prisoners, no discrimination against IWW members and no censuring of IWW literature. After three weeks the camp operators tried to bring in scabs from Alberta and Saskatchewan. Pickets severely curtailed the scabbing and on February 26 the operators served an injunction on the officers and members of the IWW to restrain the strikers from picketing. The seven companies asked for $105,340.41 in damages. At a mass meeting March 2, strikers voted to “take the strike back on the job.” As the injunction came up for review on June 24, the Mountain Lumbermen’s Association paid to the IWW $2,450 to settle out of court.

In 1925 the LWIU branch disappeared from Cranbrook — a not unfamiliar event in the IWW, which still refused to sign binding contracts with employers, and often dwindled away as an organization after specific demands had been won. A new Agricultural Workers branch was formed in Winnipeg, bringing the IWW a total of 6 branches in Canada for a membership of 10,000 — the same as in 1910.

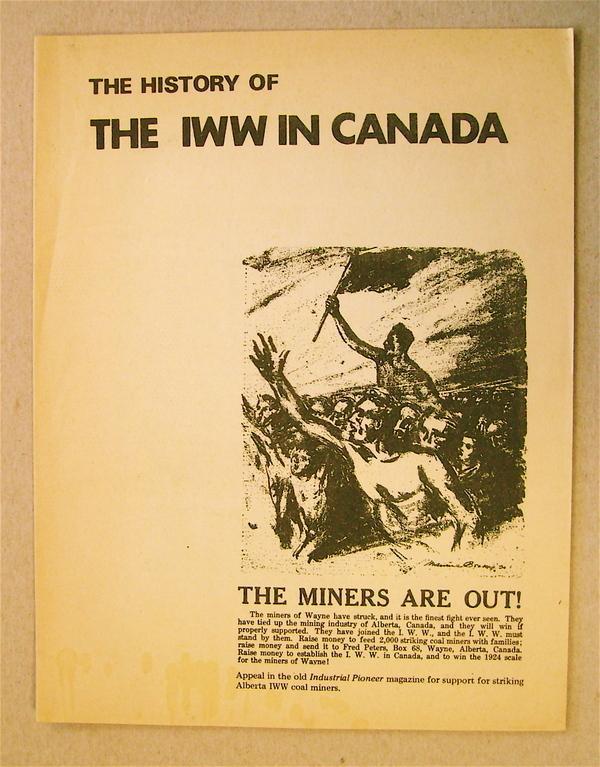

Included was a coal miners branch in Wayne Alberta which fought that year the IWW’s first large strike in coal — a bitter and losing affair. Fighting a mandatory dues check off to the United Mine Workers, which did not represent them, the miners originally joined the OBU, but along with the Ontario lumberworkers switched to the IWW in 1924. The mine company offered a 10% wage increase if they agreed to accept the UMWA. Considering it a bribe, the miners refused and struck, unsuccessfully.

The Winnipeg AWO folded in 1926, as did the Alberta Coal Miners IU branch, but a new General Recruiting Union branch was formed in Port Arthur, in addition to the lumberworkers for a total of 4,600 members in Canada. Seven branches carried 4,400 members through 1927–28 — the IWW General Convention in Chicago urged a joint IWW/OBU convention, which did not materialize — in 1929 the Calgary GRU disappeared, bringing membership down to 3,975.

The IWW Lumber Workers Industrial Union 120, came under competition in 1928 from the refurbished Lumber Workers Industrial Union of Canada, organized by the Communists following the failure of their AFL take-over bid, and in tune with Stalin’s new 1928–34 “left turn” period which demanded independent Communist unions. Communist organizers who had left for BC in the early 20’s to bring carpenters and lumberworkers there into the AFL now returned home to build dual unions under the aegis of Workers Unity League. A number of meagre contracts were obtained from small operators in the northern Ontario woods, for whom the largely Finnish lumberjacks worked. IWW branches asked that union policy be changed to allow them to sign contracts as well, but the 1932 General Convention again voted against allowing binding contracts, and a majority of Ontario lumber workers ended in communist controlled unions. Ironically, it was only a few years later that the US IWW was signing contracts and running in federal NLRB elections.

Changes in the 30’s

The early 30s were a watershed era in the history of North American labor. Initially stunned by the vicious poverty and unemployment caused by the Capitalist breakdown in 1929–31, the working class by 1933–34 had gained the offensive in a massive wildcat strike wave that swept the continent. The period saw an upsurge in IWW activity in Canada, a phenomenon applicable also to the OBU, which even expanded organizing into the New England and opened a hall in San Francisco, and the Canadian Communist Workers Unity League, which was especially strong among textile workers, needle trades, mine and mill workers, and seamen’s unions.

Radical influence was also strong in the US mass strike period, represented by the IWW: longshore, maritime, lumber, construction, mining, metal trades, early auto organizing, and unemployed — the Socialist Party: needle trades, unemployed, later auto — the Communist Trade Union Unity League: mine and steel, textile, furriers, longshore and seamen, teachers, unemployed, veterans, Blacks

---- Trotskyists: Minneapolis Teamsters — and the Musteite CPLA/American Workers Party: Toledo Auto-Lite strike, unemployed.

By 1930, the Sudbury IWW LWIU folded, but a new Lumber workers branch formed in Sault Ste. Marie, giving the union 3,741 members in Canada. Canadian delegates met in Port Arthur September 20, 1931, and voted to form a Canadian administration, primarily to overcome customs problems over supplies sent from Chicago and to coordinate specifically Canadian industrial activity. The move was submitted for consideration at the IWW Convention in Chicago November 8–19, 1931, where it was referred to a general membership referendum and ratified. The Canadian administration was to be autonomous but ultimately responsible to the General Administration and paying a monthly 1/2 cent per capita for international organizing costs.

IWW unemployment agitation generated a number of arrests, especially one big crackdown by Royal Mounted Police at Sioux Lookout, Ontario. Ritchie’s Dairy in Toronto was unionized IWW for a time, and a fisher’s branch formed in McDiarmid, Ontario.

Organizing was undertaken in the Maritimes but did not sustain itself. In 1935 the IWW had 12 branches in Canada with 4,200 members: 2 branches in Vancouver-- Lumber workers and General Recruiting Union — General Membership Branches in Sointula, BC, Calgary, Toronto, Sudbury; lumber workers in Fort Francis, Nipigon, Sault Ste. Marie, and Port Arthur Ontario; a General Recruiting Union in Port Arthur; and a Metal Mine Workers branch in Timmins, Ontario.

The working class rebellion of the mid thirties culminated in a series of sit down strikes — using the tactics developed a few years earlier in the auto plants by the IWW, including the little cards passed hand to hand, reading: “Sit down and watch your pay go up.” — which established the Congress of Industrial Organizations/CIO. The CIO was a reformist semi- industrial movement launched by the United Mine Workers which succeeded where the revolutionary industrial unions had failed. Its success was due primarily to its willingness to collectively bargain with employers for modest wage and conditions changes and then to enforce submission to the contract on any subsequent rank and file rebellion. Both the Roosevelt administration and a sector of “far-seeing” Capitalists saw in this an opportunity to corral the strike wave into the bounds of a lightly reformed capitalist system. (Slower to move, the Canadian ruling class followed suit only toward the end of the Second World War.)

Hundreds of unauthorized work stoppages were suppressed by CIO chieftains. At one point CIO head and leader of the United Mine Workers, John L. Lewis, threatened to dispatch “flying squads of strong-arm men” to bring auto wildcatters into line.

The CIO drive coincided with a far reaching right turn by Stalin (and by iron-fisted extension, the then monolithic world communist movement, sans Trotskyites of course). The Workers Unity League was jettisoned by the Canadian Communists; its independent unions were brought into the AFL or CIO or sabotaged. Communist militants flocked into the CIO organizing committees and assiduously worked themselves into key positions, ranging from stewards to actual union presidents. The CIO ventures were highly successful, initially in the US and after WWII in Canada.

The Communists captured the leadership of ten industrial unions, including the United Electrical Workers, the Mine Mill & Smelter Unions, the Fur and Leather Workers, the Canadian Seamens Union and United Fishermen, and the B.C. Ship builders Union. They also become strong in the International Woodworkers, especially in BC, the AFL International Longshoremen, and others.

In the broader Canadian union movement, a number of things were happening. In 1921 TLC expelled the Cdn. Brotherhood of Railway Employees in favour of the Brotherhood of Railway and Steamship Clerks from the USA. In 1927, the CBRE, the OBU remnant, and the old CFL joined together to form the All Canadian Congress of Labour. The CFL had been the stillborn result of the merger of the Knights of Labour and some national unions in 1903, after their expulsion from AFL-dominated TLC.

First called the National Trades and Labour Council, in 1908 it became the Cdn. Federation of Labour, a big name for so little, and now in 1927 it dissolved into the ACC of L. The All-Canadian Congress grew, in its own reactionary way; in the early 30s the OBU supported the red-baiting bureaucracy, only to find itself later ousted. In 1937 the ACCL chiefs aided the anti-union Ontario Premier Hepburn in his attack on the AFL, CIO, and Communists — all seen as “American.”

In 1938, however, the TLC under AFL pressure expelled the CIO unions in Canada and, in a complete flip-flop, the CIO units joined the ACCL in 1940 to form the Canadian Congress of Labour. Considering that many of the CIO organizers were Communists, and all the CIO unions internationals from the USA, it was quite a marriage of convenience. In 1943 the CCL came out in support of the social-democratic Cooperative Commonwealth (now the New Democratic Party)-- although the Communists were supporting the Liberal Party.

After WWII the CCL grew closer to the TLC, especially as both were expelling communists en masse. Finally in 1956 the CCL and TLC merged to form the Canadian Labour Congress. Another independent union body organizing during this period was the Canadian and Catholic Confederation of Labour in Quebec, established in 1921, now the syndicalist CNTU.

The success of a moderate semi-industrial unionism, temporarily fringed with a radical hue, greatly hampered the revolutionary industrial unionism of the IWW. Another factor was the extremely conservatizing influence of the Second World War — ostensibly an anti-fascist crusade — with its no-strike pledges, for which the Communists were the strongest backers in the interests of the Soviet Fatherland — even to the point of denouncing all strikers, such as the United Mine Workers, as “fascist agents.”

Even so, the IWW in the USA was able to stabilize a number of solid job units, particularly metal shops in Cleveland area, and by fighting the no-strike pledge expanded general membership on the docks and construction camps. In 1946 the IWW numbered 20,000 members.

IWW agitation continued strong in Canada until 1939, especially in northern Ontario, but Canada’s entry as British ally into the war and the resulting mass conscription and War Measures Act, caught the union without a job-control base. Moreover, in-fighting with the Communists had become particularly vicious. Sudbury was being organized by the Communist controlled Mine Mill & Smelters to the point that J. Edgar Hoover later called it the “red base of North America.”

Wobbly units in Sudbury and Port Arthur were mixed membership branches of scattered lumbermen, miners and labourers. During the Spanish Civil War 1936–39, the IWW in Ontario actively recruited for the anarcho-syndicalist CNT union militia in Spain, in direct challenge to the Communist sponsored Mac-Pap International Brigade. A number of Canadian Wobs were killed in Spain — some possibly shot by Stalinist NKVD agents. Not only weapons and ammunition but even medical supplies were denied the CNT by the Communist-controlled government of Madrid. Violent altercations erupted at northern Ontario rallies for the communist doctor Norman Bethune, soon to quit Spain for Mao’s partisans in China, when Wobblies openly denounced Communist perfidy.

World War II

In Toronto where the IWW Canadian Administration headquarters was temporarily moved, Wobblies gave physical support to the soap boxing efforts of anarchists from the Italian, Jewish and Russian communities. Pitched street battles often occurred at Spanish CNT support rallies, and IWW secretaries McPhee and Godin, both former lumberjacks, were noted for their quick despatch of Young Communist goon squads.

But the War halted IWW organizing. A number of young Wobs were immediately inducted into the Armed Forces. At war’s end re-growth was too slow. In 1949 membership in Canada stood at 2,100 grouped in six branches; two in Port Arthur and one each in Vancouver, Sault Ste. Marie, Calgary and Toronto.

Meanwhile the government in the USA was attempting to destroy the IWW once and for all. After refusing to sign the Taft-Hartley anti-red clause, the IWW was denied the certification services of the National Labor Relations Board. In 1949 the IWW was placed on the Attorney General’s list, which came replete with mailing curtailments, refusal to members of government jobs, loans or housing, and FBI harassment of individual members, especially at their place of employment. To cap it off, the IWW was slapped with a “corporate income tax”, the only union in North America to be so taxed. As a culminative consequence the IWW lost its last shops, including all the IU440 Metal shops in Cleveland.

During the same period the AFL and CIO began a mass purge of Communists in its ranks, an easy task, so riddled was the Communist party with opportunism and cowardice. Completed quickly in the US, the expulsions were slower and less thorough in Canada, lasting beyond 1955. Those unions the reactionaries could not purge they expelled and then raided. The Communists in Canada managed to hold only the United Electrical Workers, the remnant of Mine & Mill, and the United Fishermen in BC.

The Canadian IWW retained branches in only Vancouver, Port Arthur and Calgary by 1950- 51. The following year the Canadian Administration in Port Arthur folded and membership reverted to the services of the Chicago office. By comparison, the OBU-- by now a mild trade grouping in Winnipeg — continued until 1955–56 with 34 locals and 12,280 members at which time it merged with the CLC.

The Dark 50’s

The Cold War snuffed out the Canadian, British and Australian administrations of the IWW. It remained for the General and Scandinavian administrations to hold together scattered Wobs in Canada, USA, Britain, Sweden, and Australia. Through the 1950s the IWW still exerted some power on the docks and ships with IU510 branches in San Francisco, Houston and Stockholm. But with the early sixties, the IWW was near extinction.

Yet, the IWW survived. One, in the courage and dedication of old-timers who kept the structure going. Two, with the slow influx of young workers of a casual labour hue. In the mid-60s, the IWW organized a restaurant job branch in San Francisco, only to be raided by the Waiters & Waitresses Union. In 1964 the IWW led a blueberry harvest strike in Minnesota. With the Vietnam War the IWW began taking in young workers with ties to the campuses. IN 1968 it was decided to sign up students alongside teachers and campus workers into Education Workers IU620. There followed a wild and erratic campus upsurge, two notables being Waterloo U in Ontario and New Westminster BC. The results were nil in themselves, but it got the IWW over the hump and left a fine residue of militants who left campus to find jobs.

The next 5 years spawned some 20-odd industrial drives, including one among construction workers in Vancouver, another among shipbuilders in Malmo, Sweden, and two tough factory strikes in the USA. For the most part unsuccessful, a number had interesting features.

In a Vancouver drive, a construction crew in Gastown was signed IWW — but certification before the Socred-appointed BC Labour Board was denied, the IWW declared not a “trade union under the meaning of the Act.” A subsequent strike fizzled.

Industrial organizing efforts continue. The IWW has picked up a number of newspapers, print shops and print co-ops over the years, a few highly viable and long lived.

The new IWW has its own list of labour martyrs: the San Diego Wobs shot, bombed and arrested during the 1969–71 Free Speech Fight and Criminal Syndicalism frame up trial. Robert Ed Stover, knifed to death in San Quentin Prison, where he was framed on an arms cache charge; and Frank Terraguti, shot to death by Chilean fascists in Santiago during the 1973 coup.

In 1975, the IWW is organizing in Canada, USA, Sweden, Britain, Guam, New Zealand and Australia.

--------------------------END----------------------------------------

*see also WHERE THE FRASER RIVER FLOWS, New Star (Canada) 1991*