Frans Masereel

My Book of Hours

2020 Preface

The Masereel Group is devoted to spreading the public domain works of this great artist. The text was first acquired and then scanned. Then it was cropped, rotated, balanced, contrasted, saturated, despeckled, noise-reductioned, and some manually touched up. This was followed by OCR scanning, manual proofreading, and translating into English.

This book is in the public domain in the United States (because it was published before 1925), but it is not public domain in Europe (because its author died in 1972). But the Masereel Group is based in the United States, so everything within here is released under the Public Domain, and all content that is not allowed to be licensed under the Public Domain is released under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) 3.0 License.

UprisingEngineer, Masereel Group,

August 30, 2020

MY BOOK

OF HOURS

167 DESIGNS ENGRAVED

ON WOOD BY

FRANS MASEREEL

---

Foreword by -- ROMAIN ROLLAND

---

My Book of Hours

Se trouve chez l'Auteur

THIS EDITION IS STRICTLY LIMITED TO 600 COPIES FOR AMERICA. EACH COPY IS SIGNED.

No. 544

Frans Masereel [Signature]

FOREWORD

During the war, Switzerland was the refuge of a small number of artists who refused to take part in the fratricidal conflict of the European nations, and kept their faith in the internationality of thought. Frans Masereel, of Ghent, was one of the most prominent. Settled at Geneva, but linked in friendship with the little group of liberal French minds in the front rank of which shone the names of the poets, René Arcos and P. J. Jouve, he shared with them--and with us--the sorrow and mental revolt of those dark years. This community of trials cemented among us a union of mind that was at once our happiness and pride. I owe a debt to exile for giving us such brave comrades, and above all the good and great Masereel, big-hearted and great-minded.

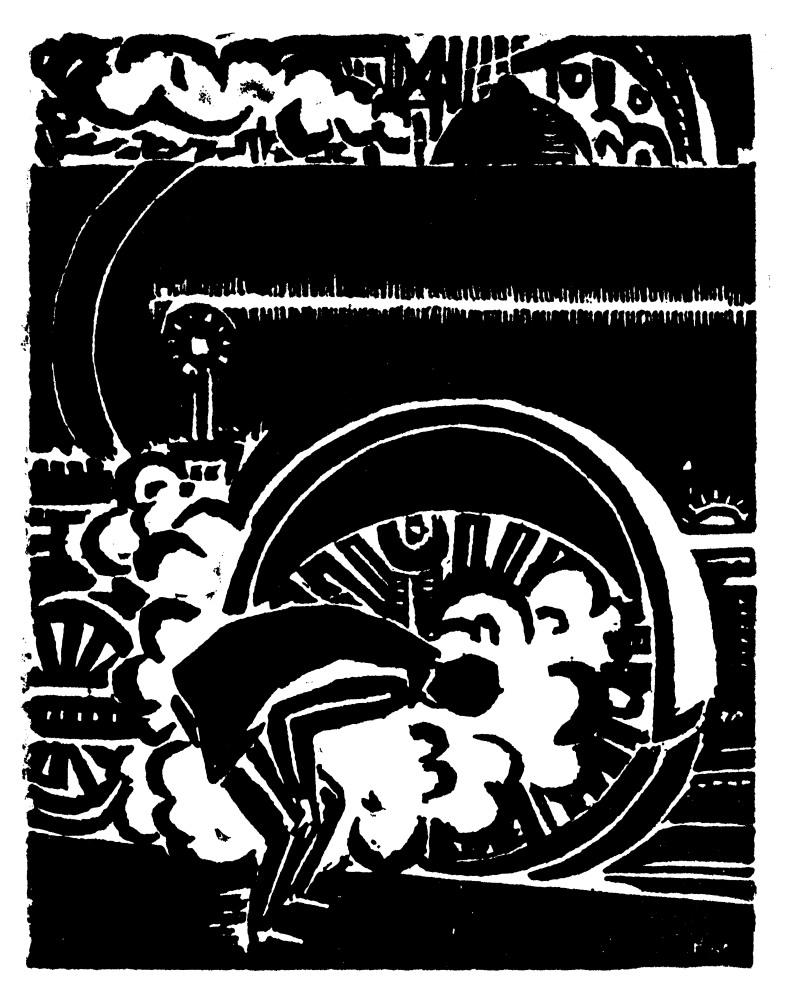

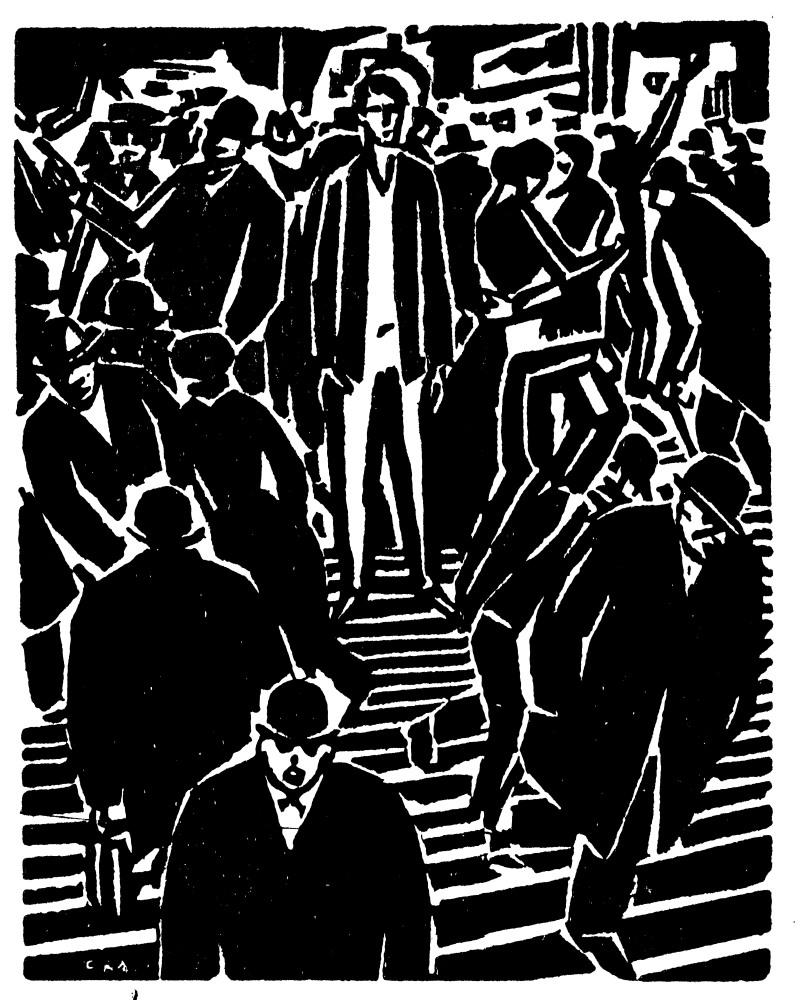

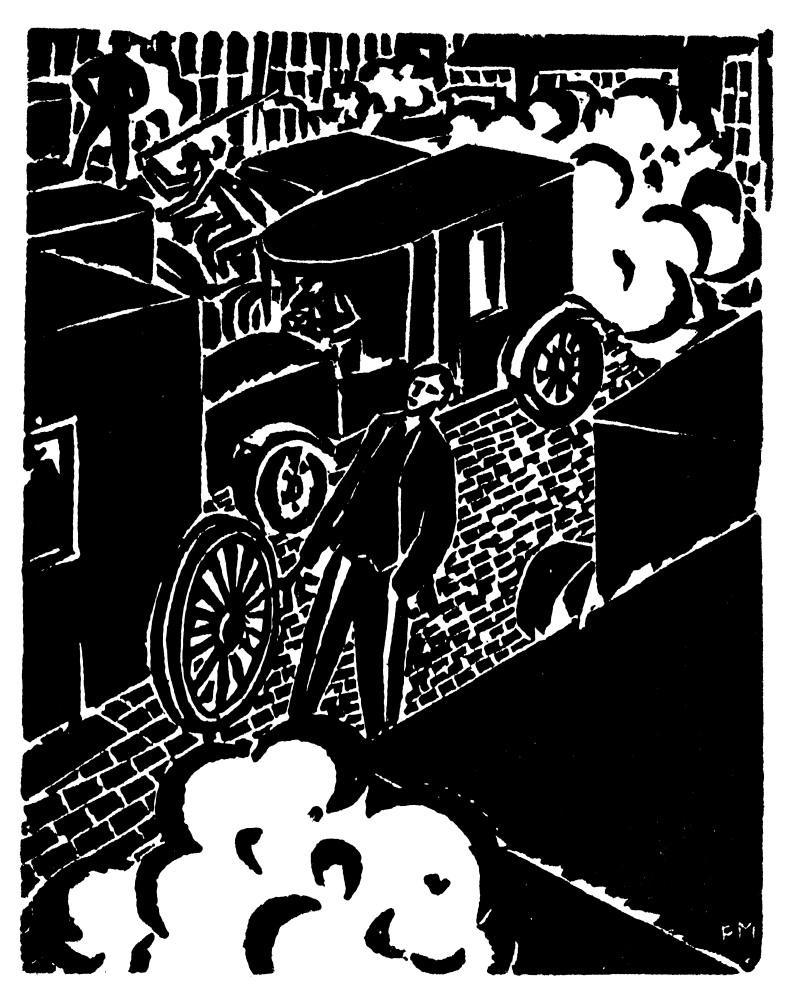

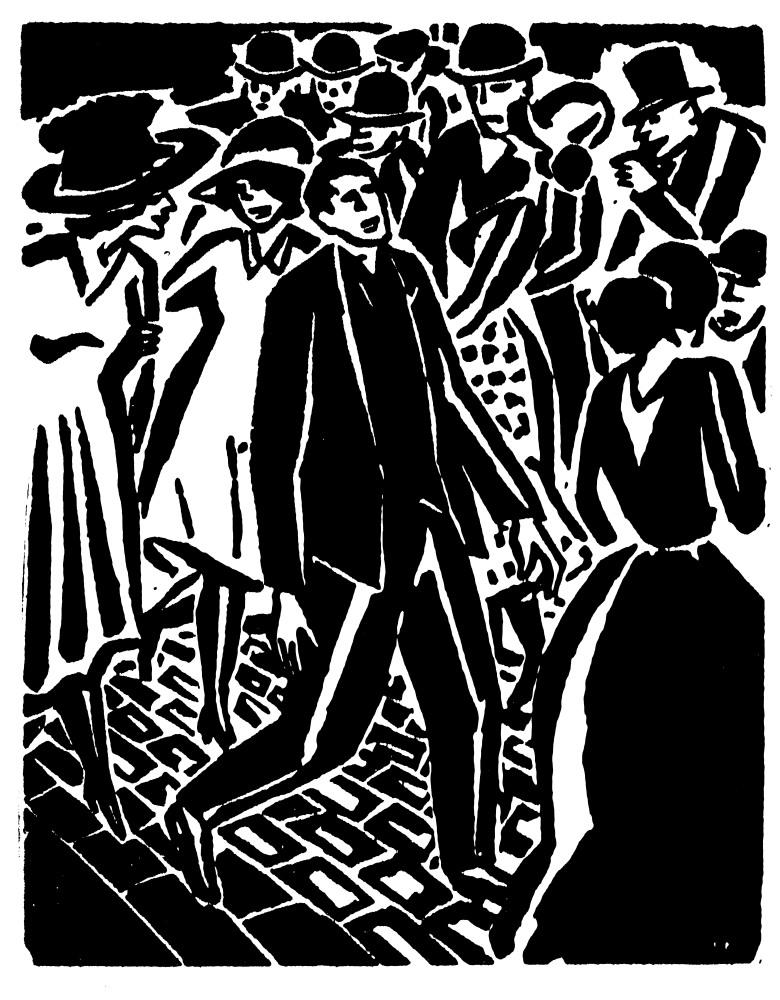

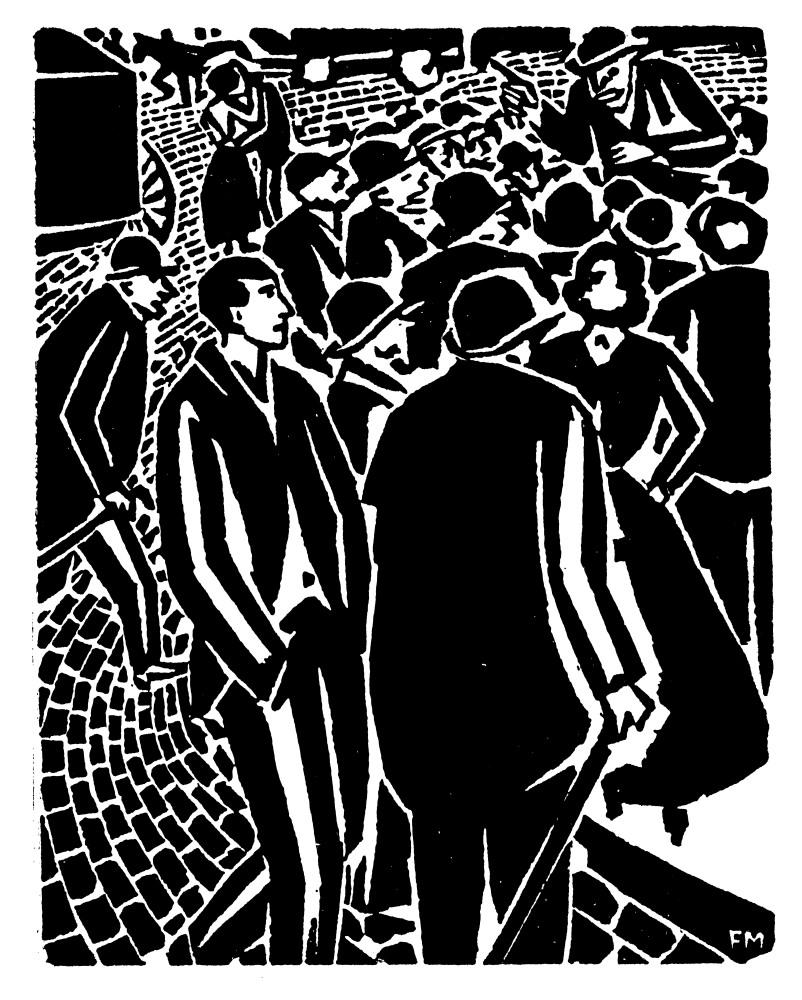

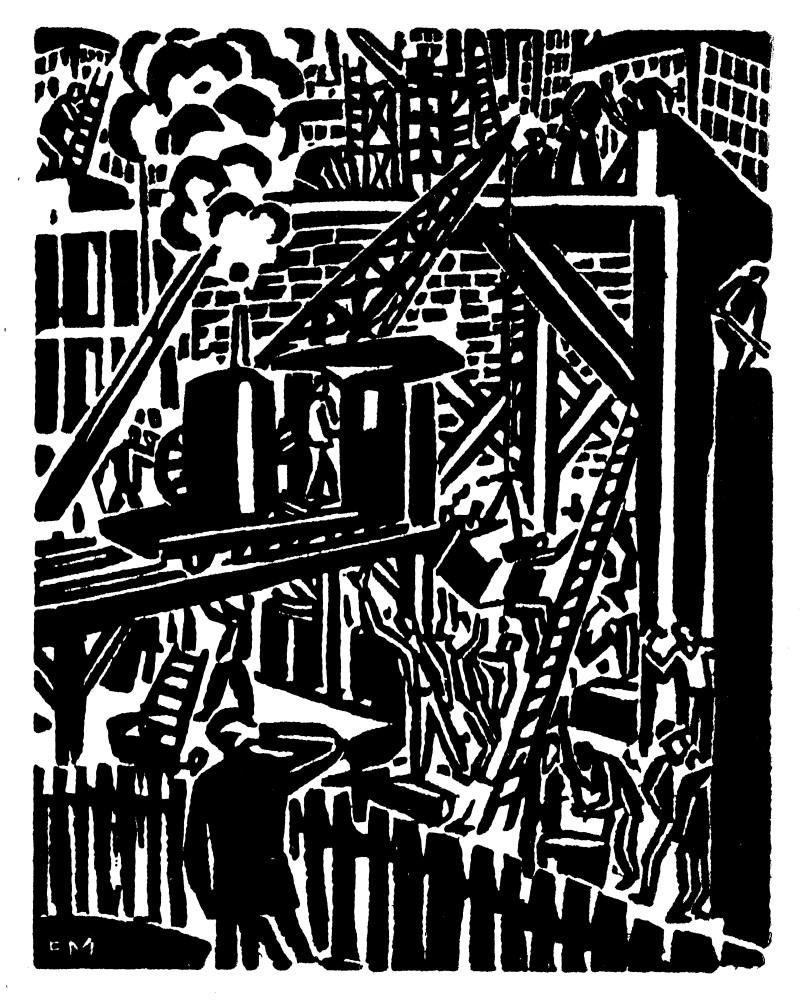

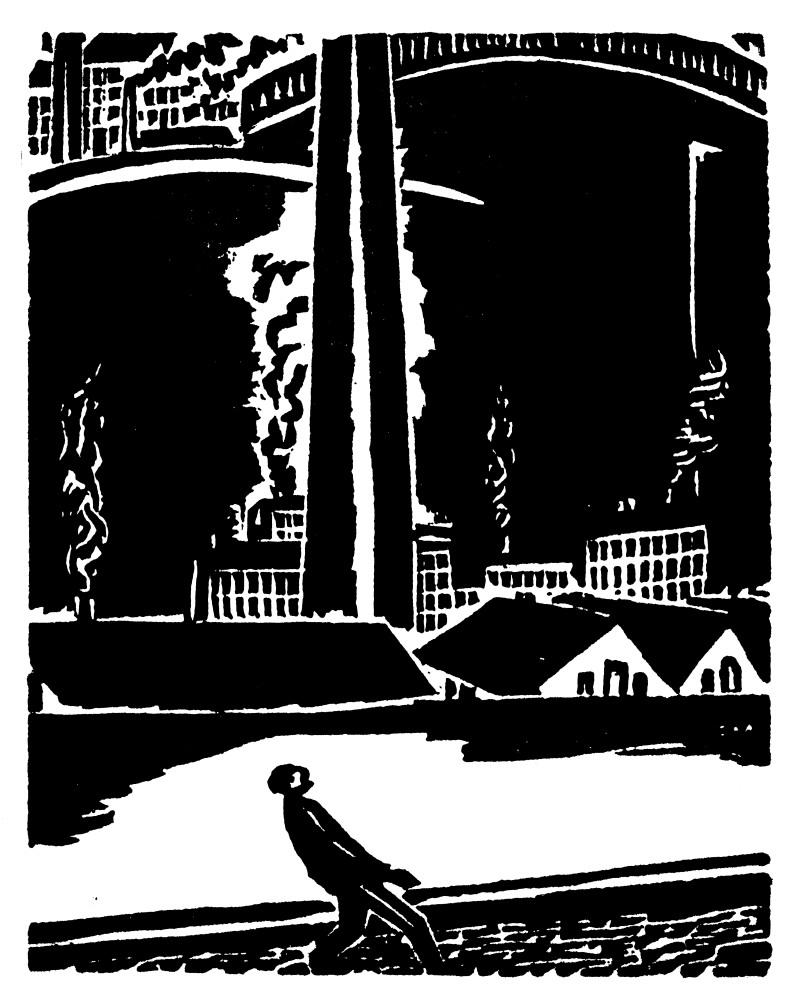

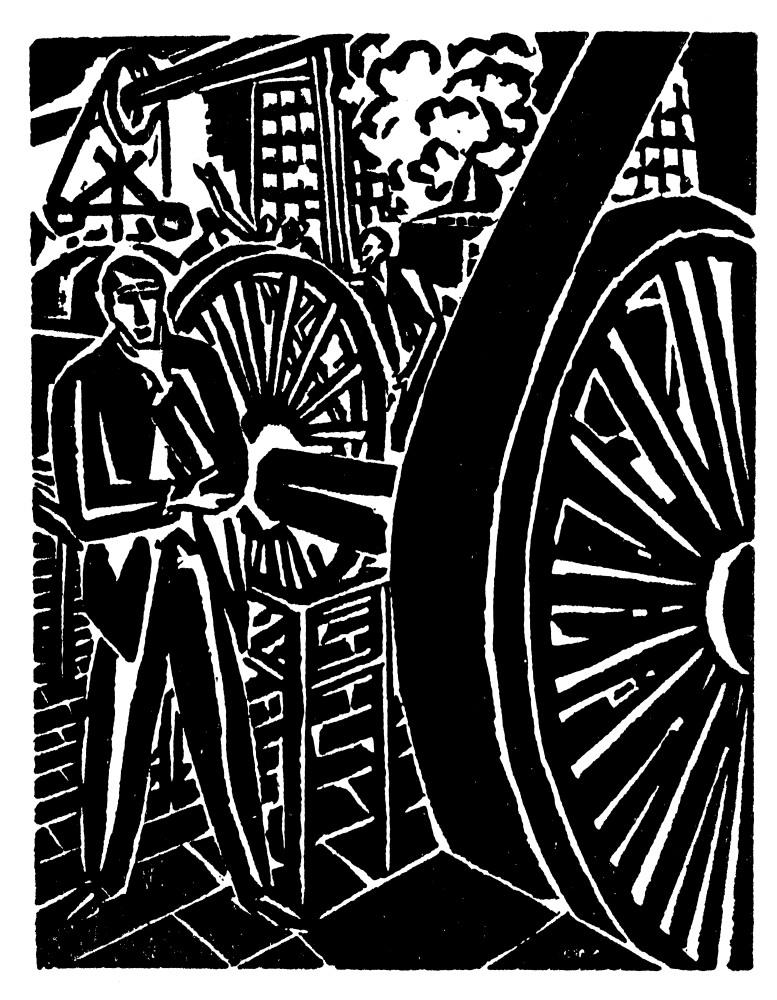

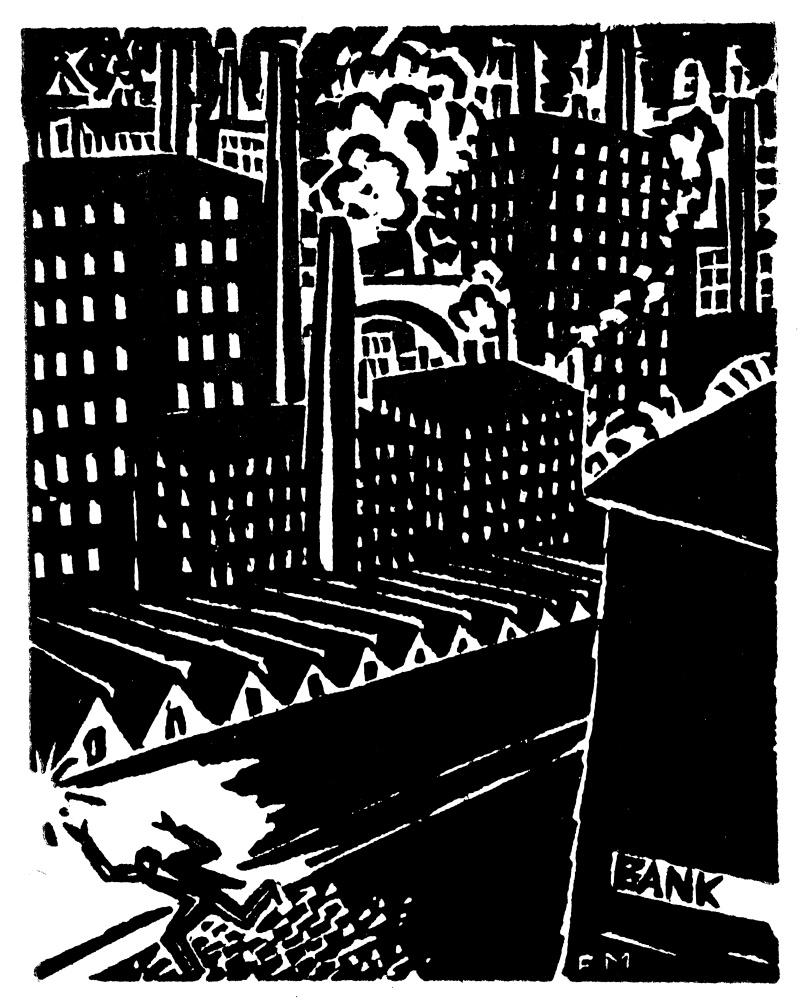

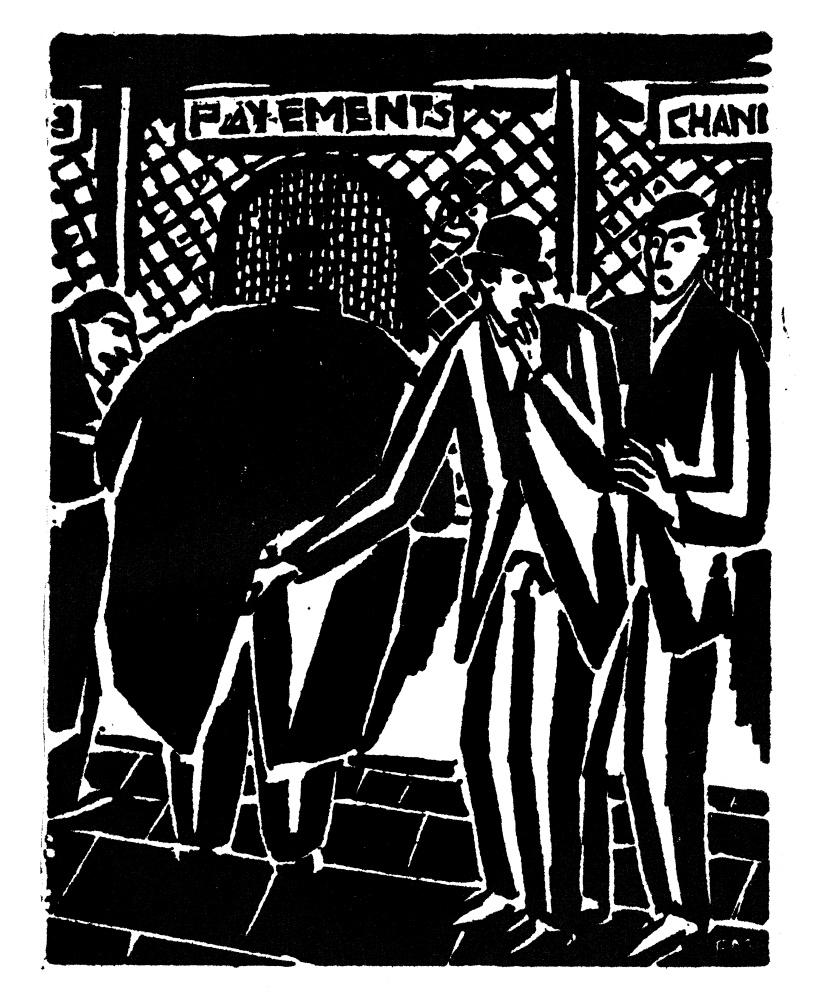

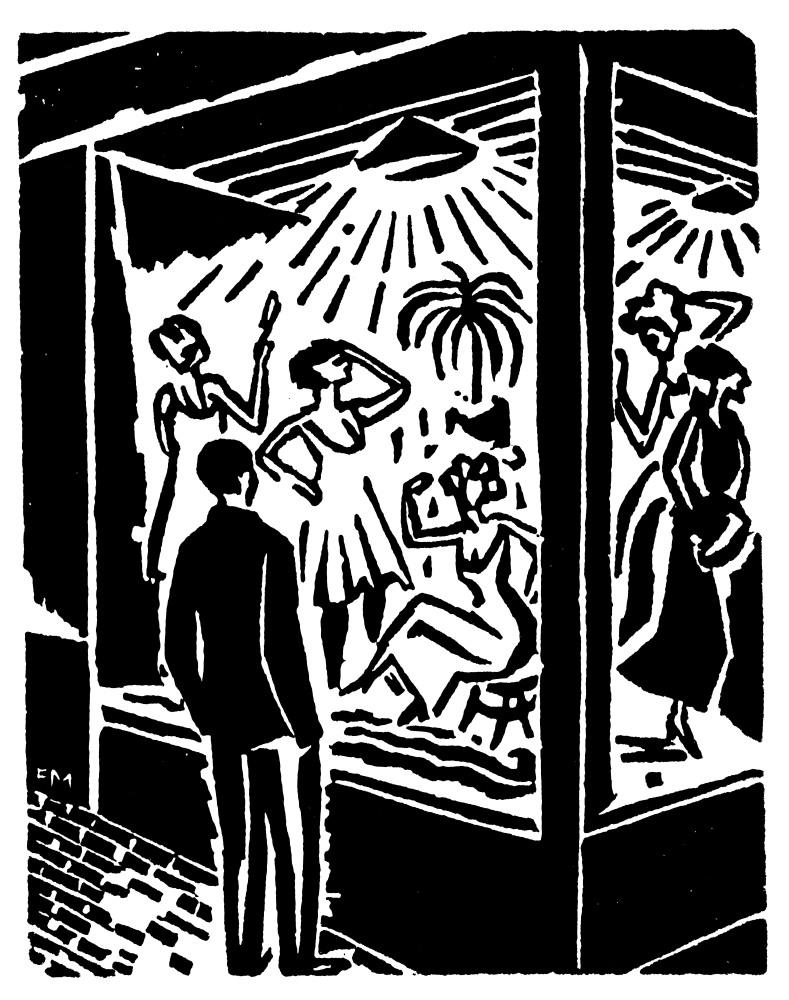

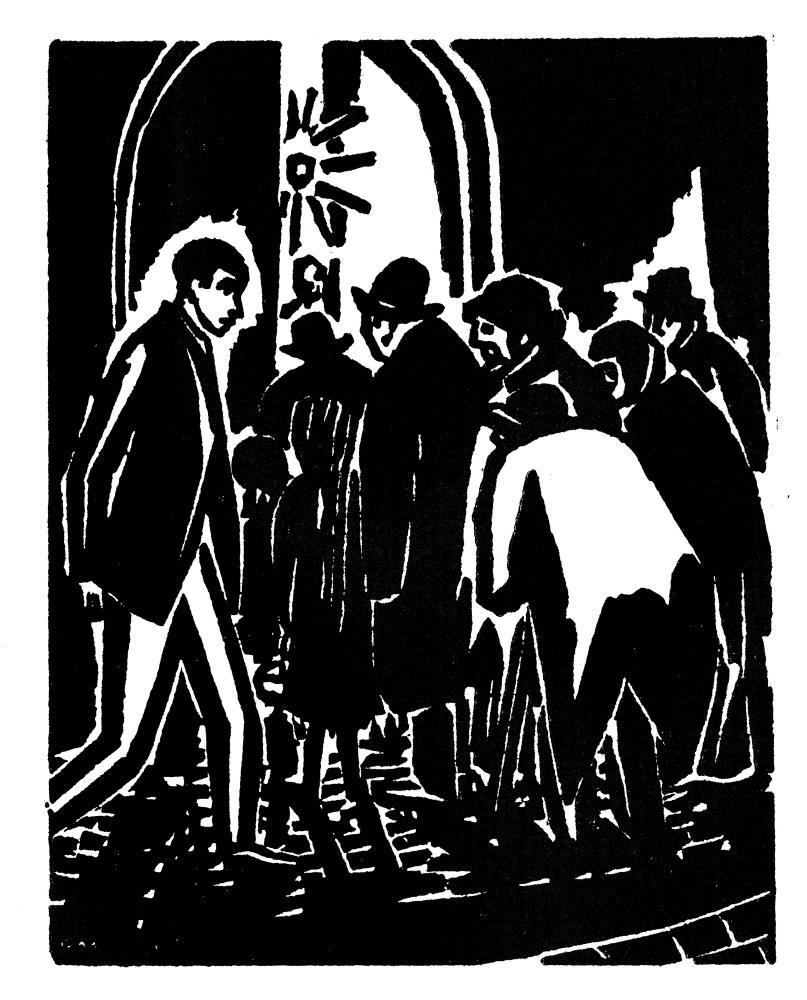

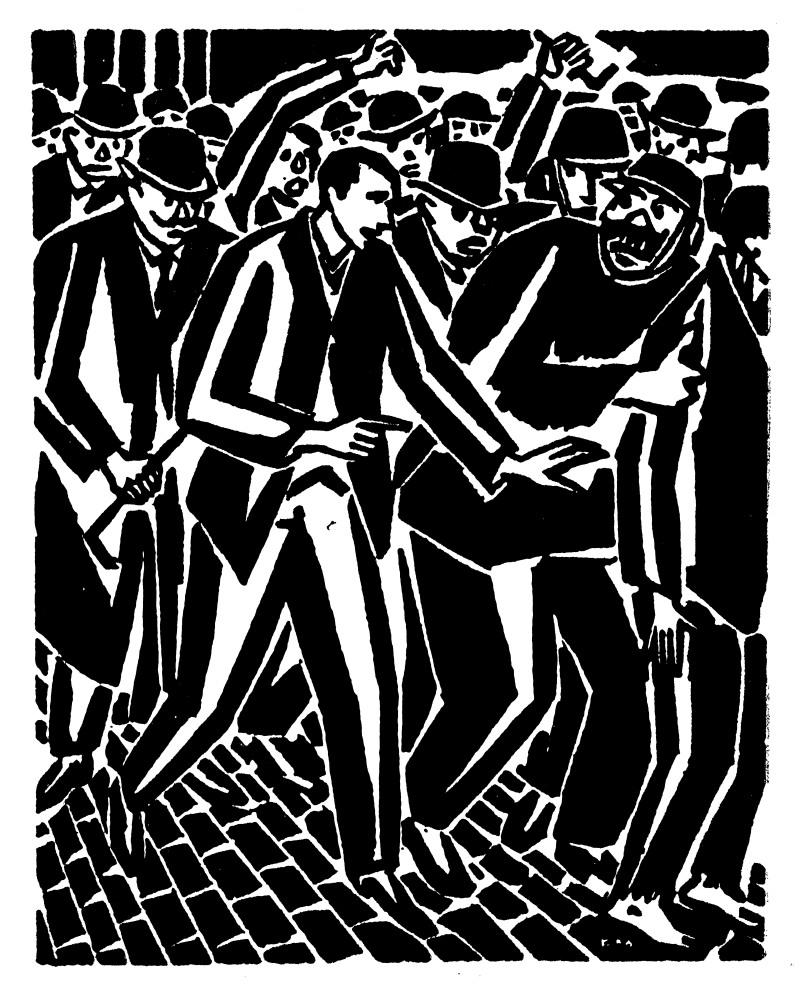

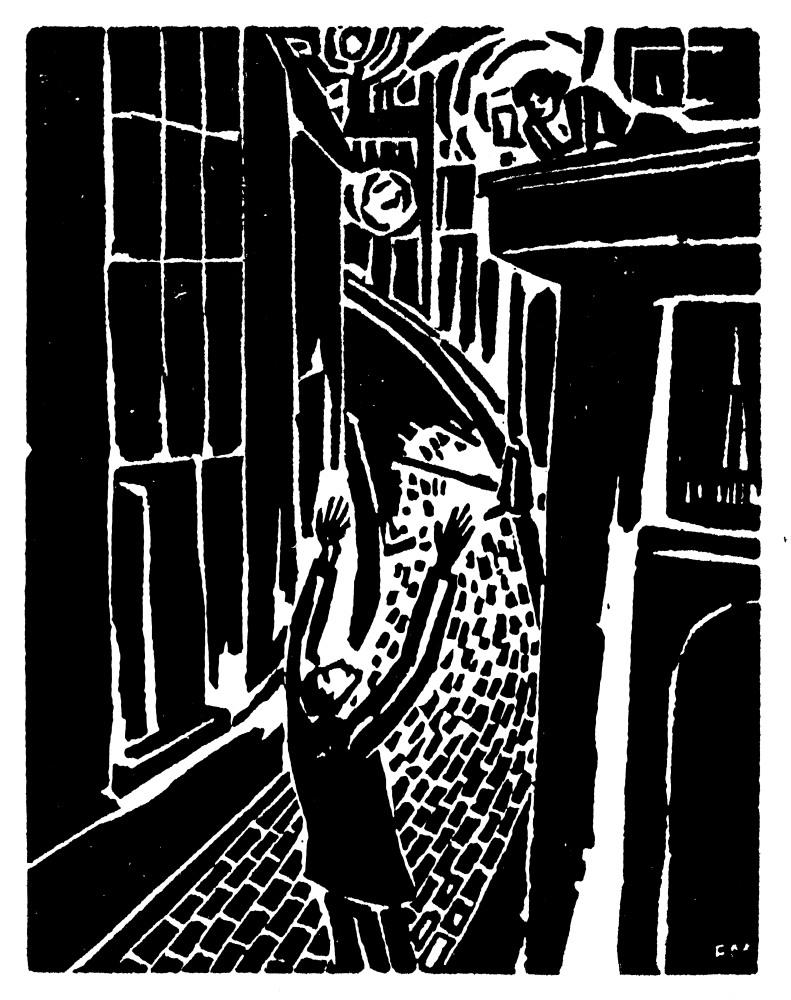

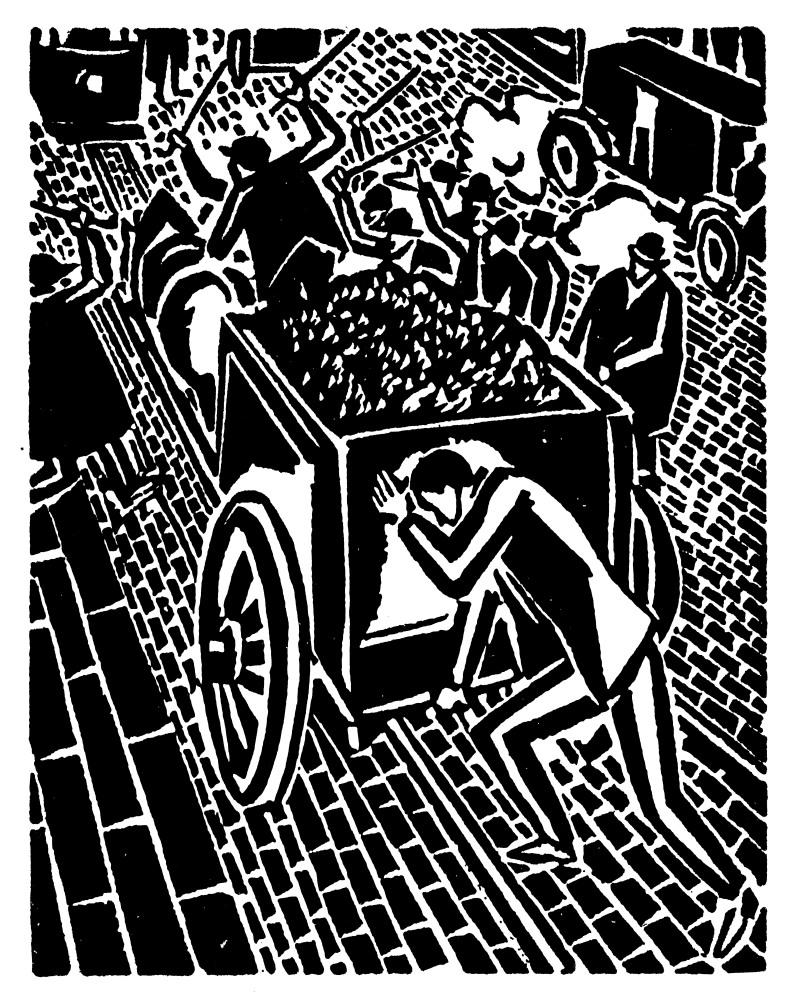

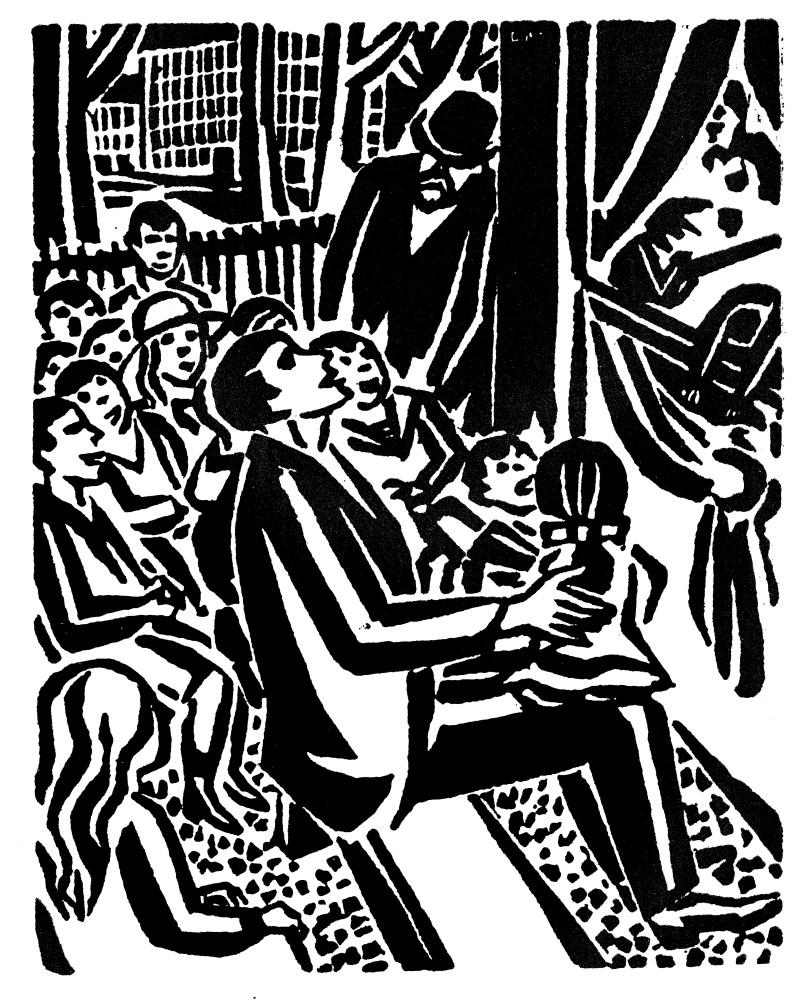

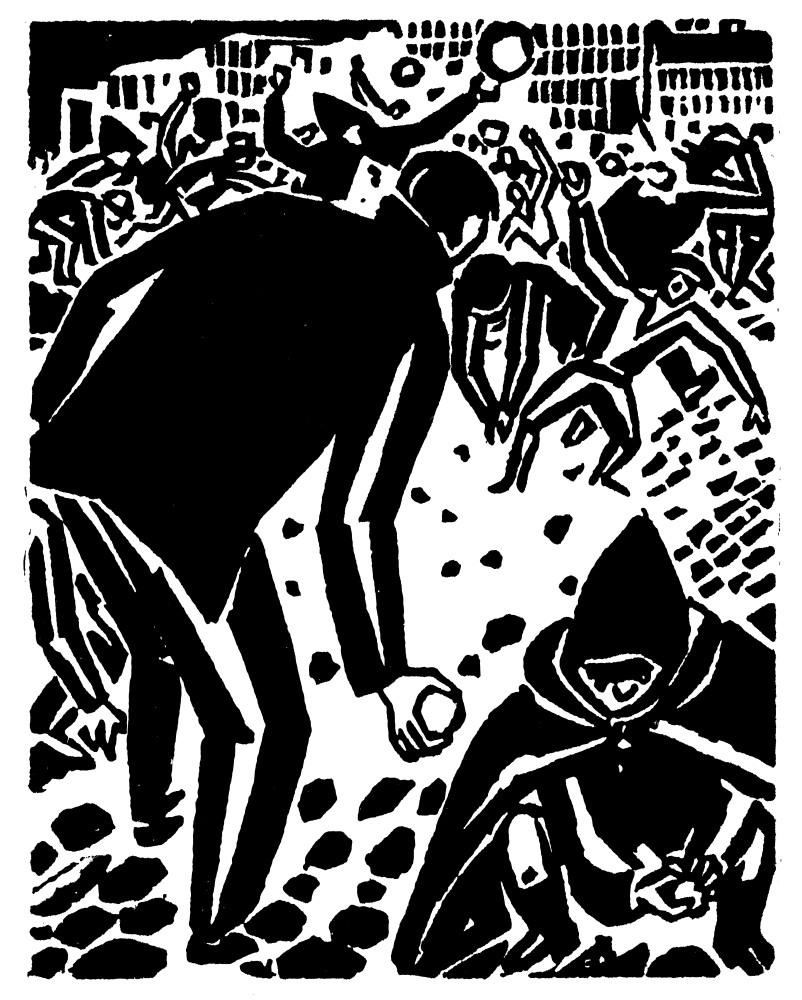

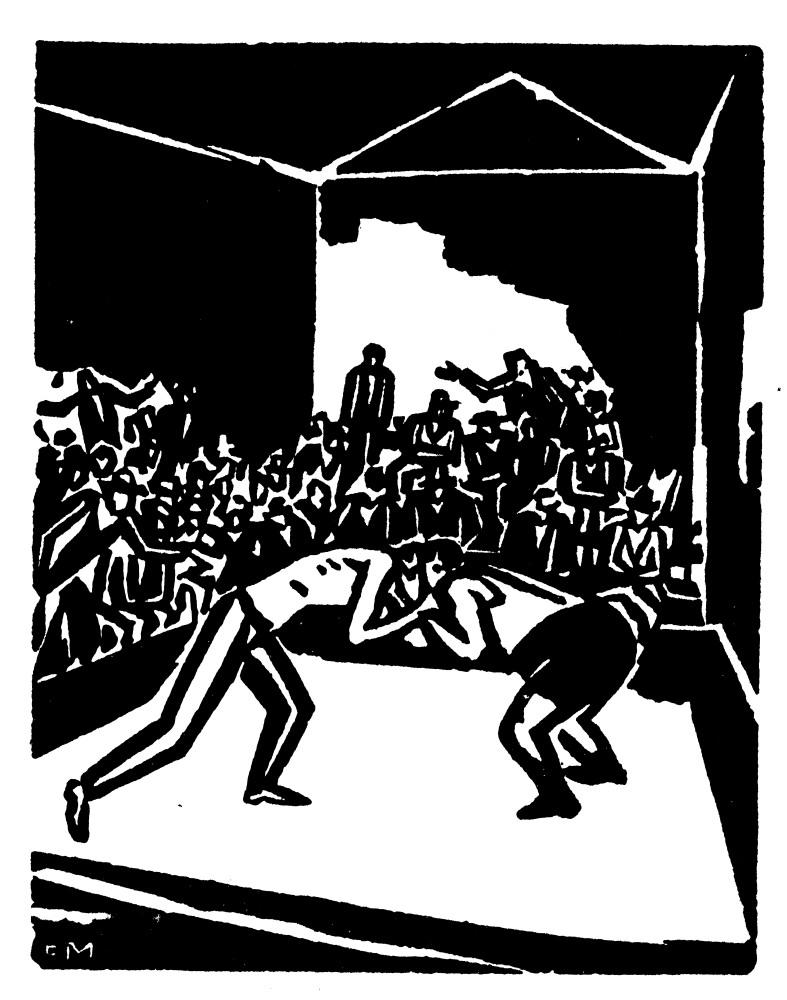

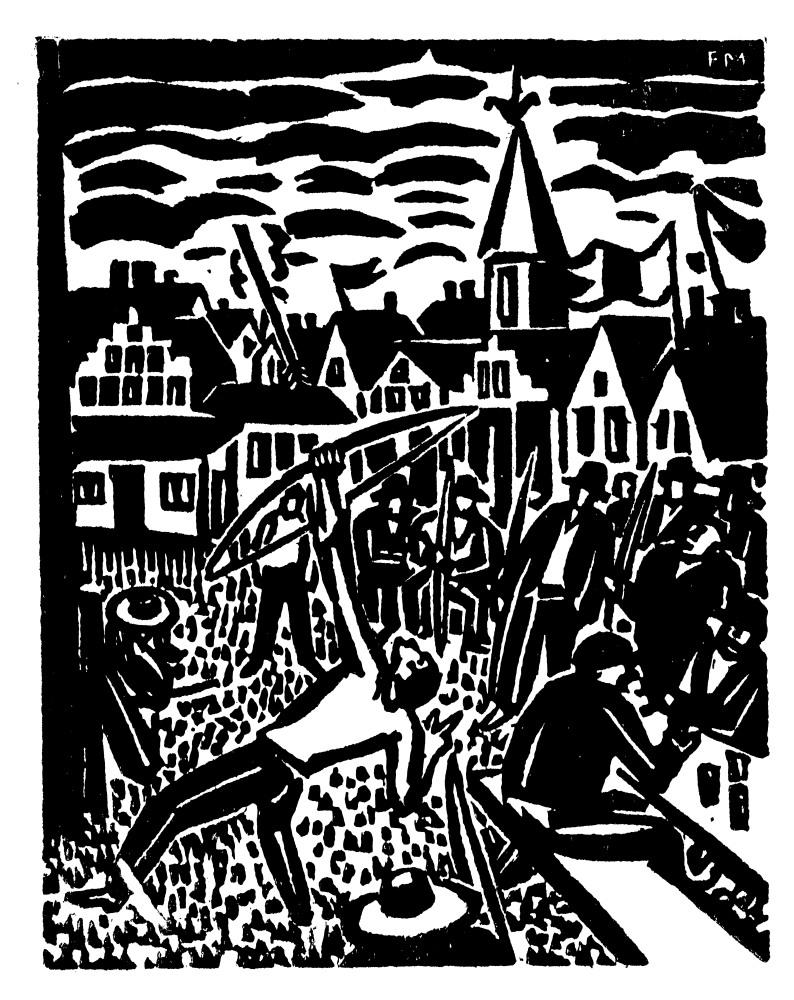

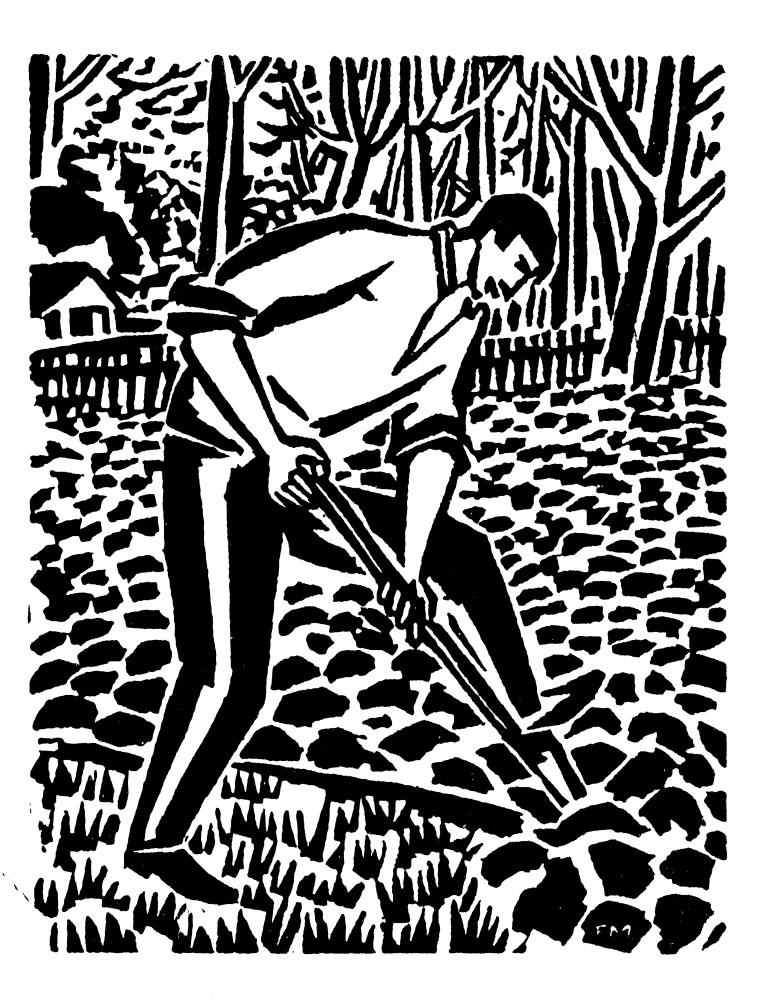

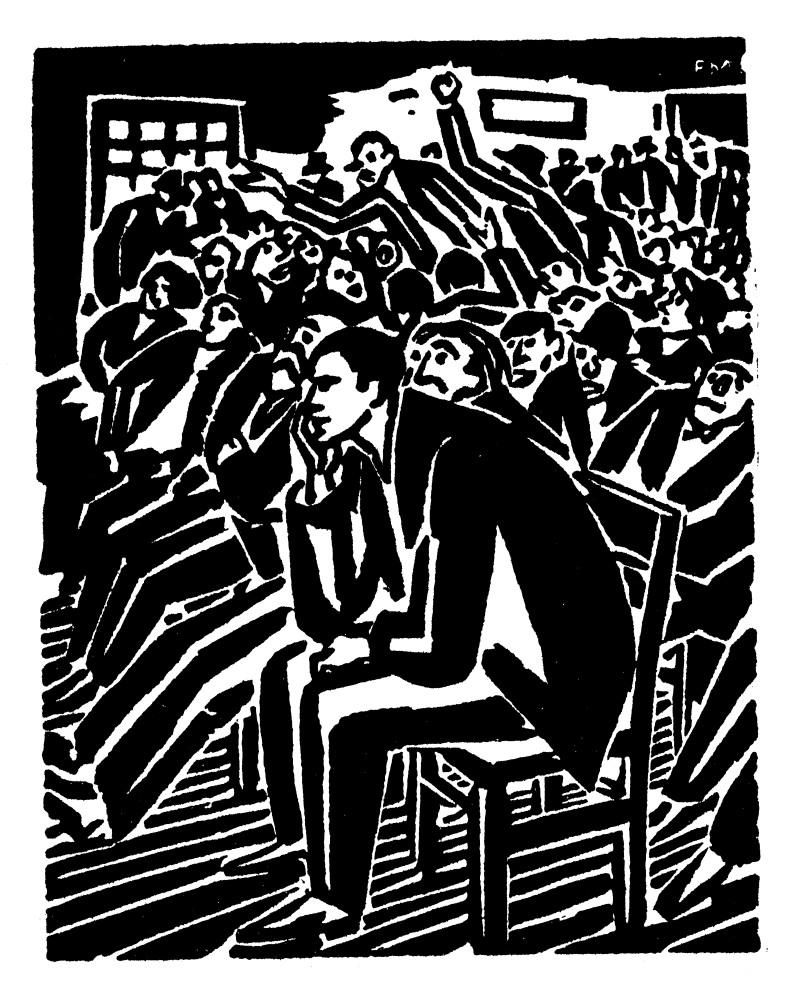

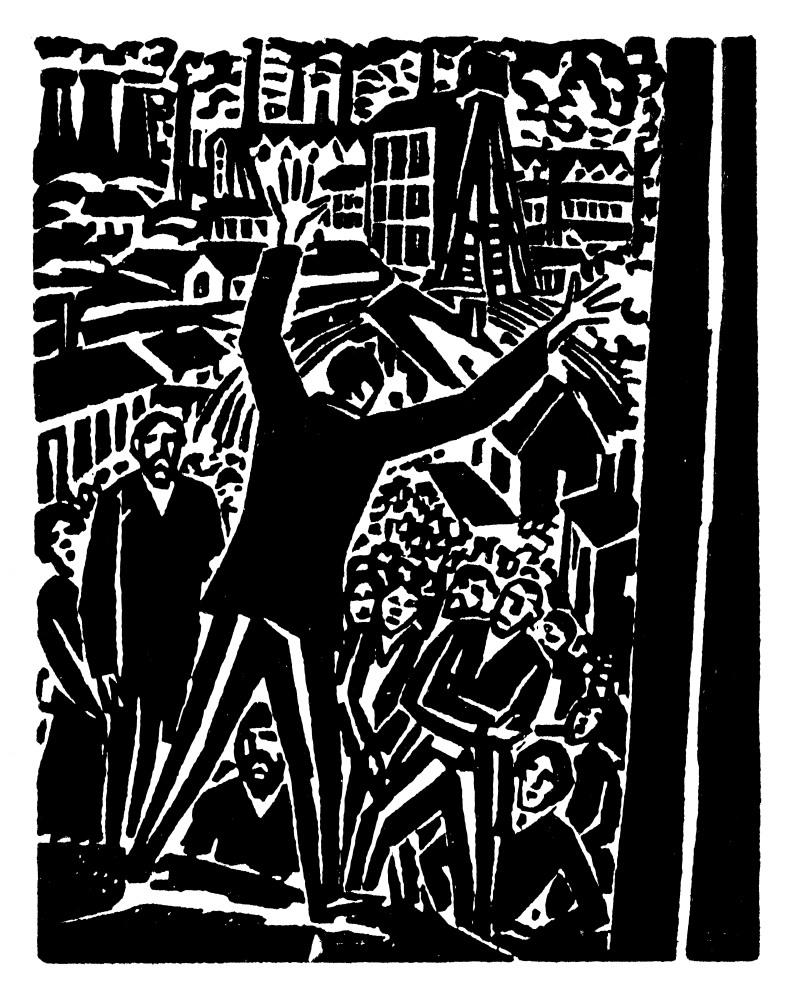

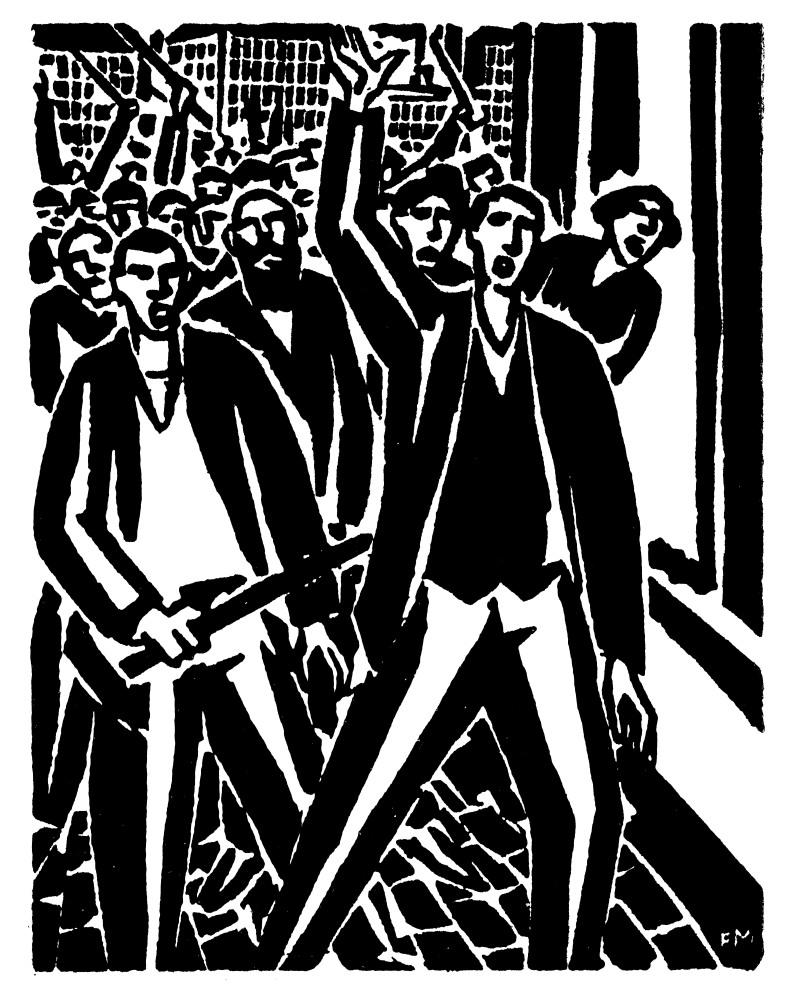

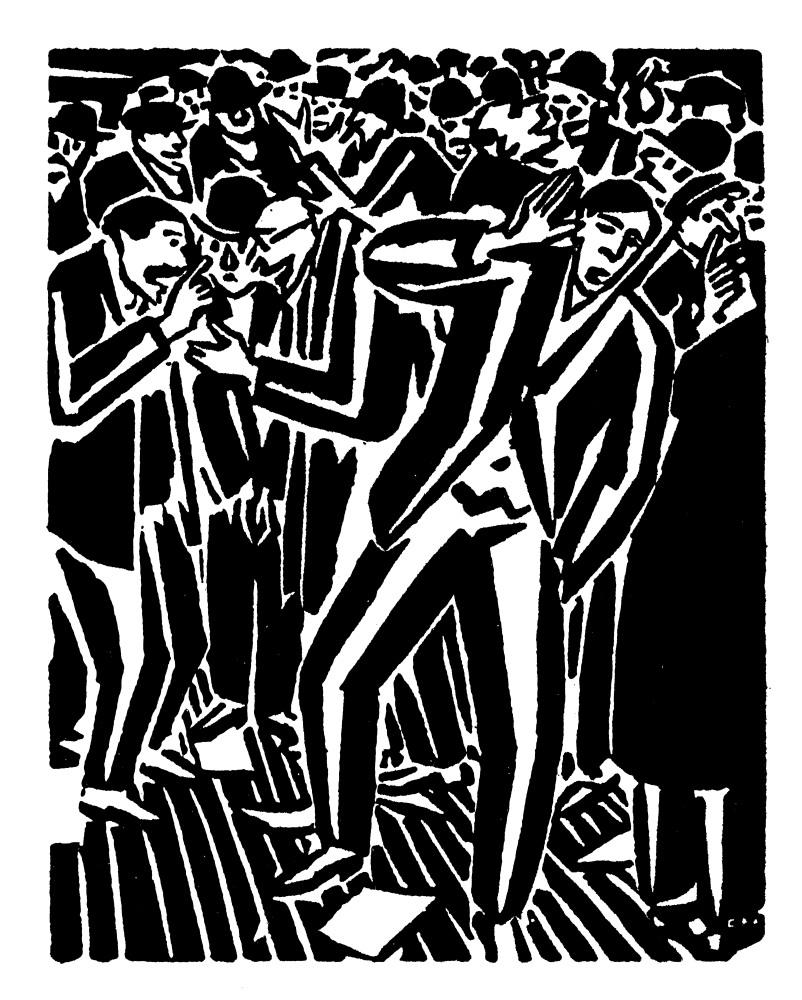

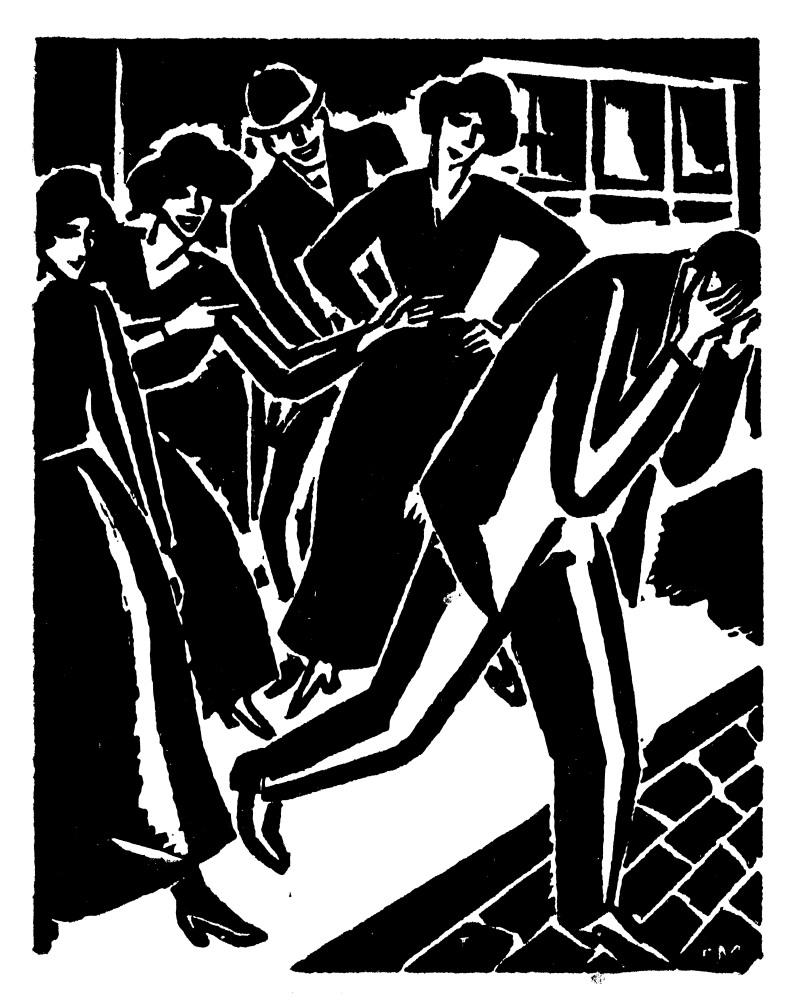

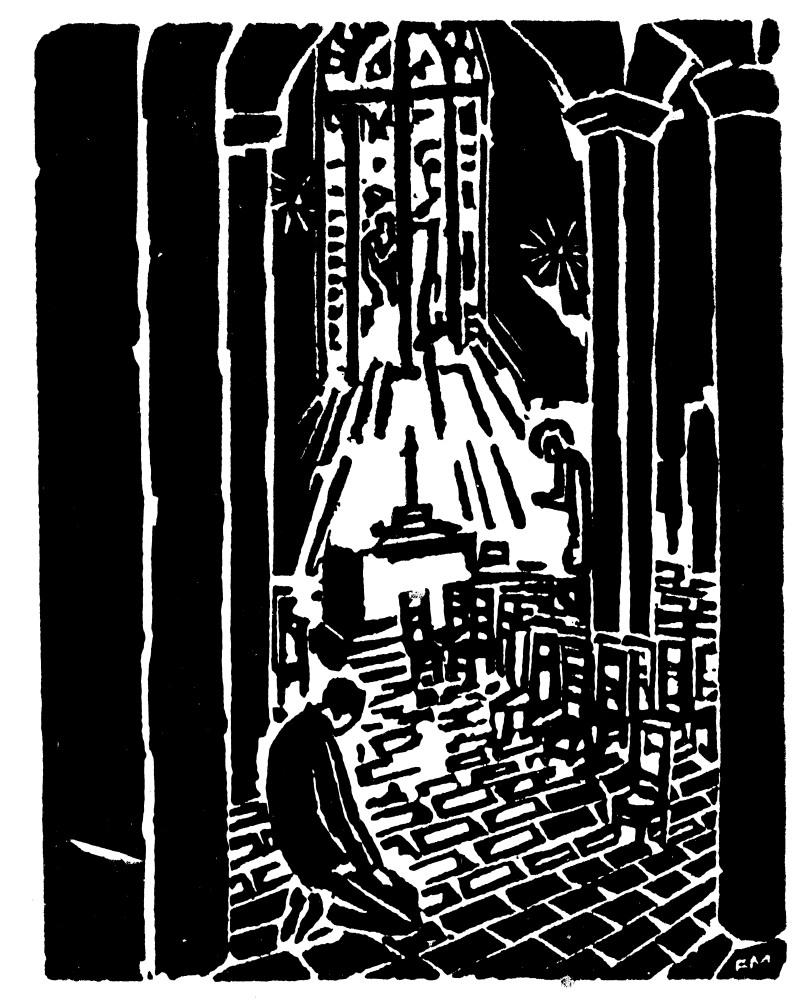

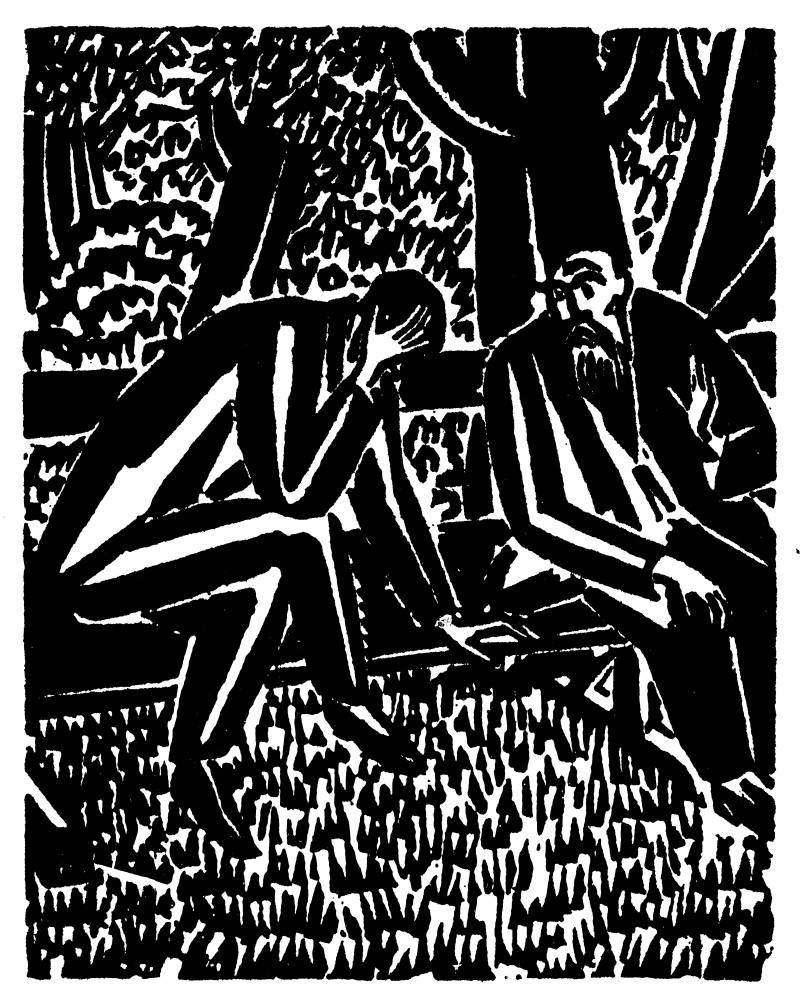

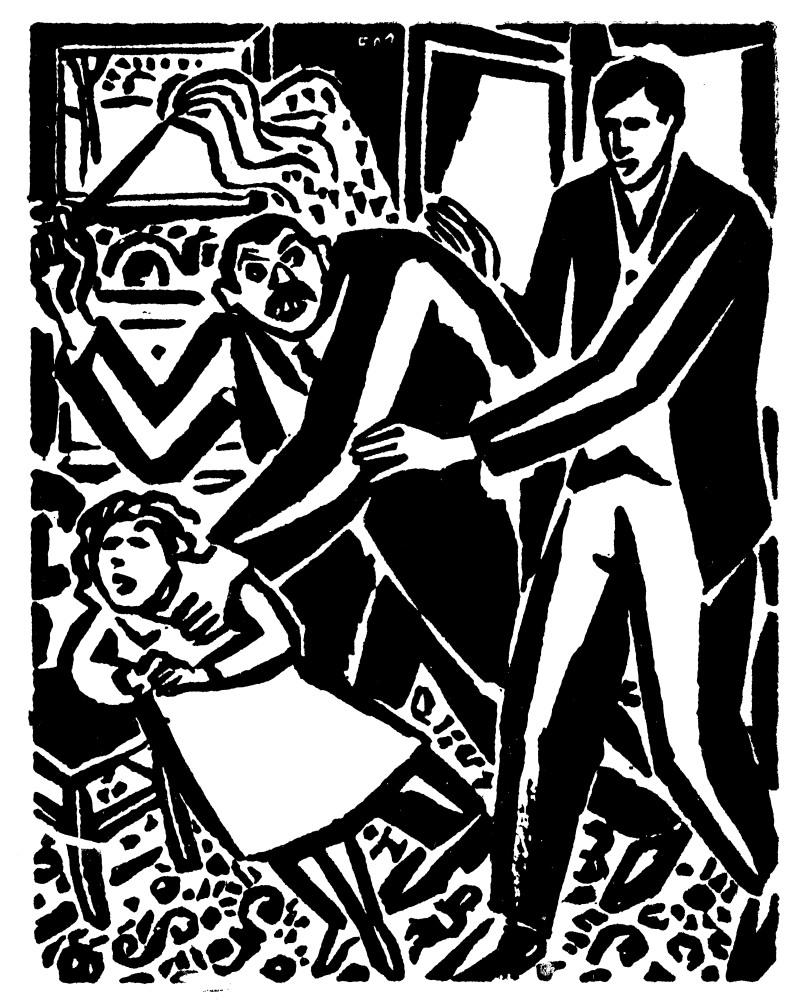

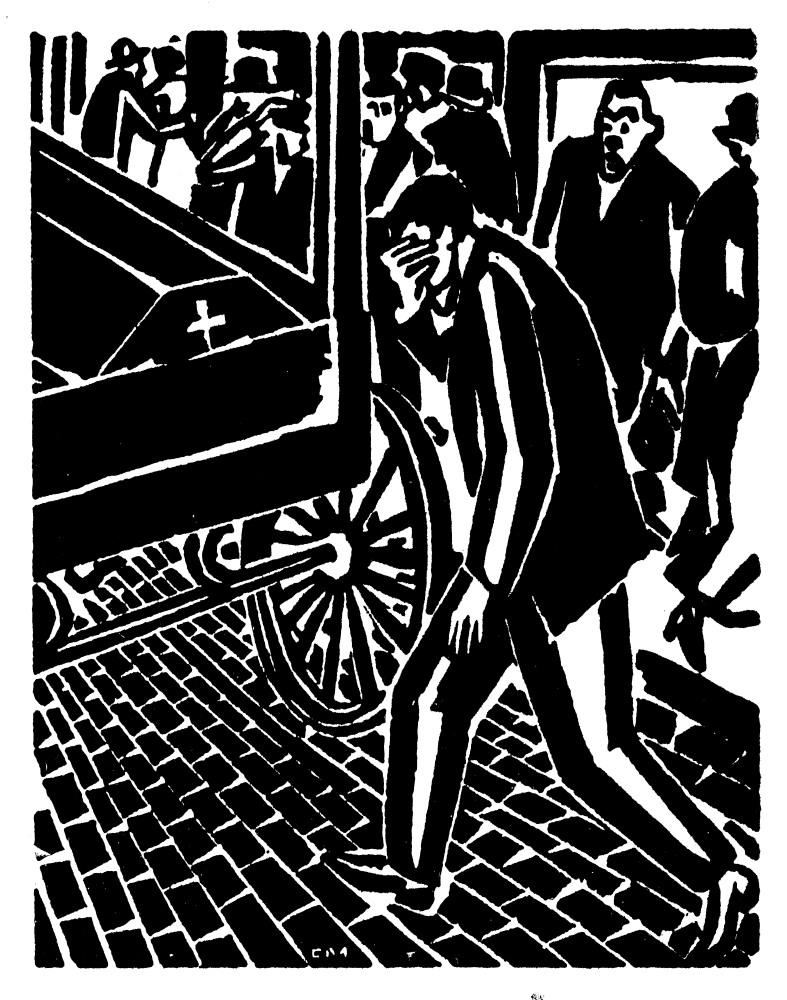

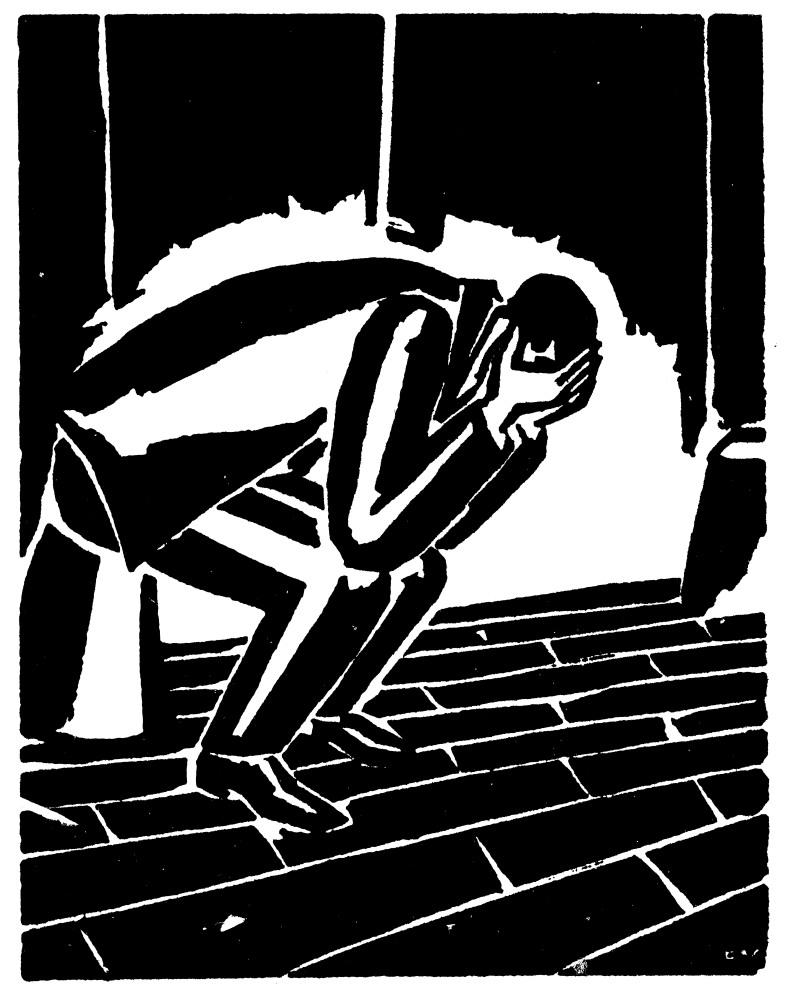

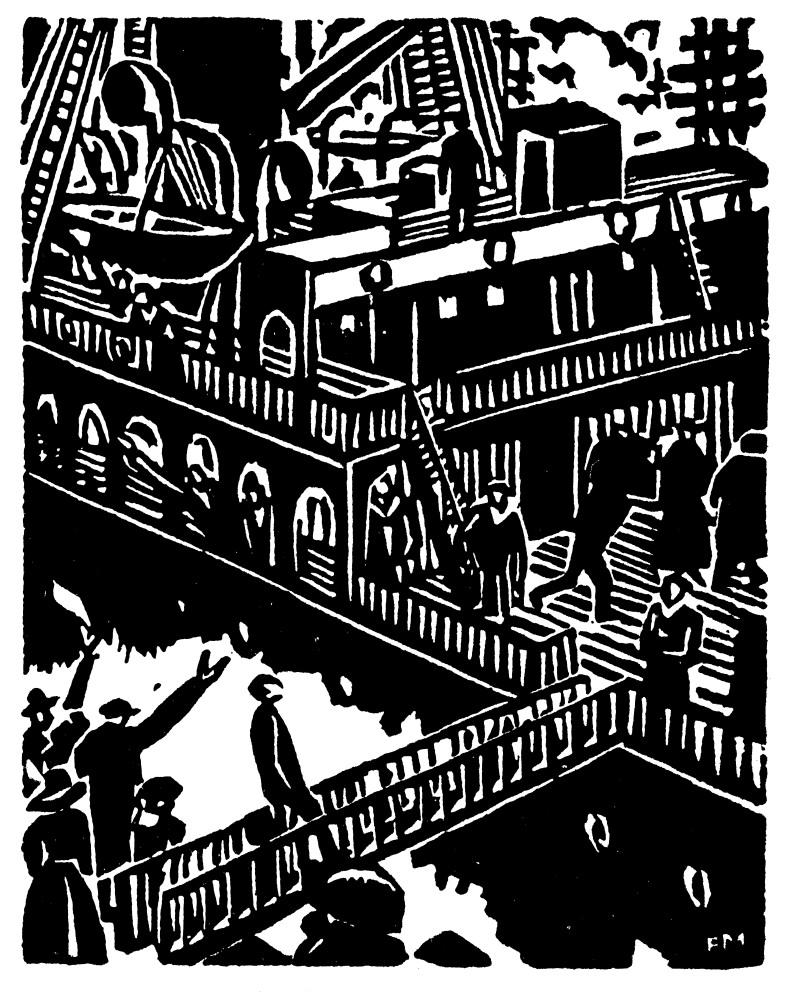

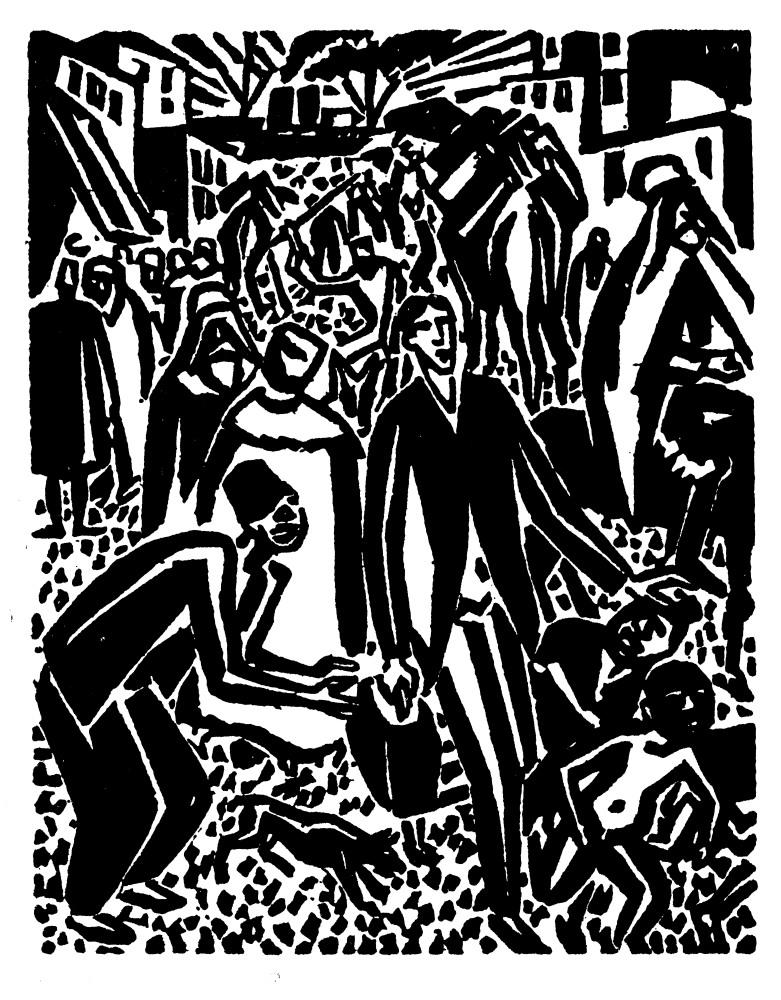

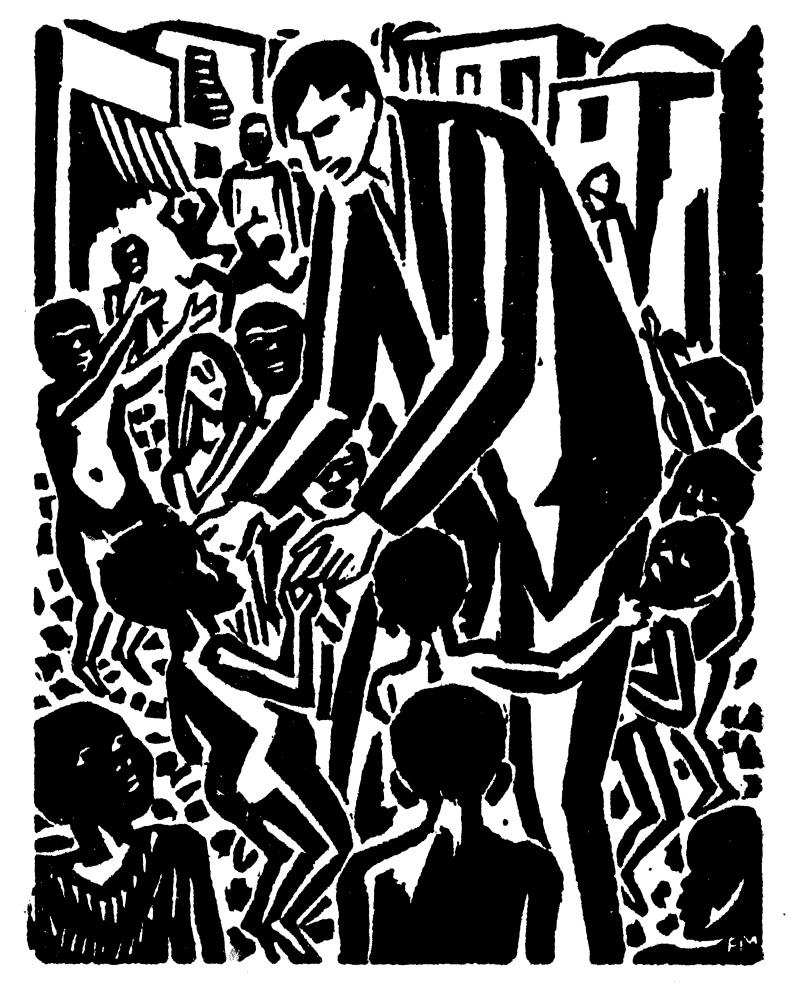

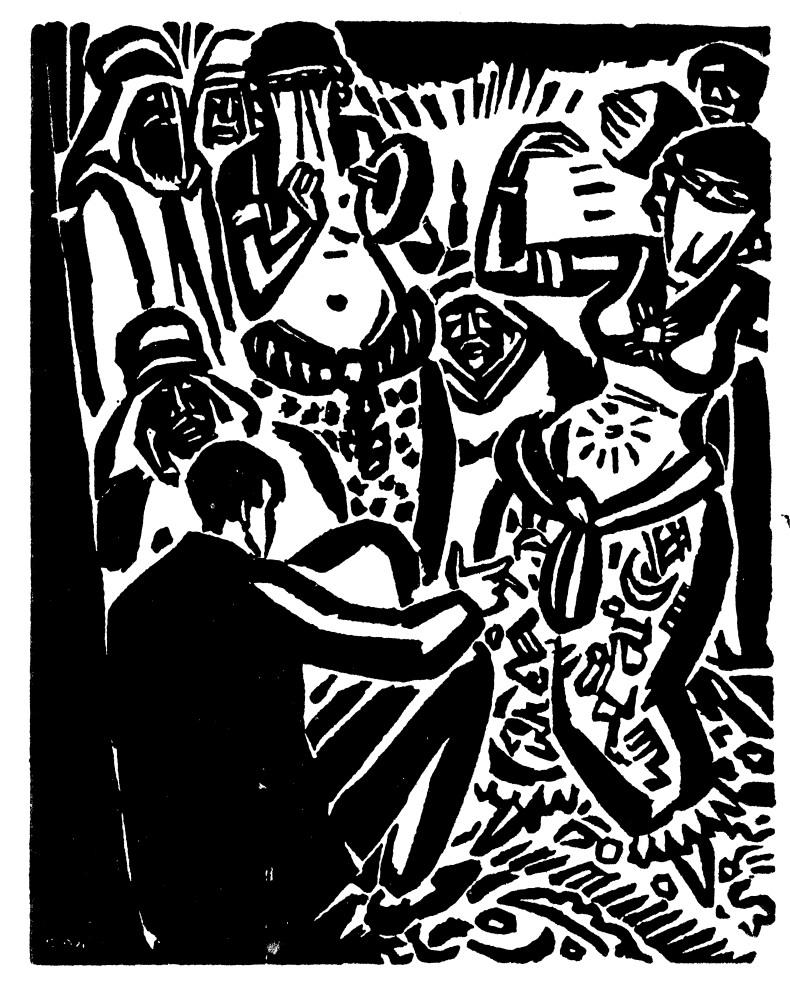

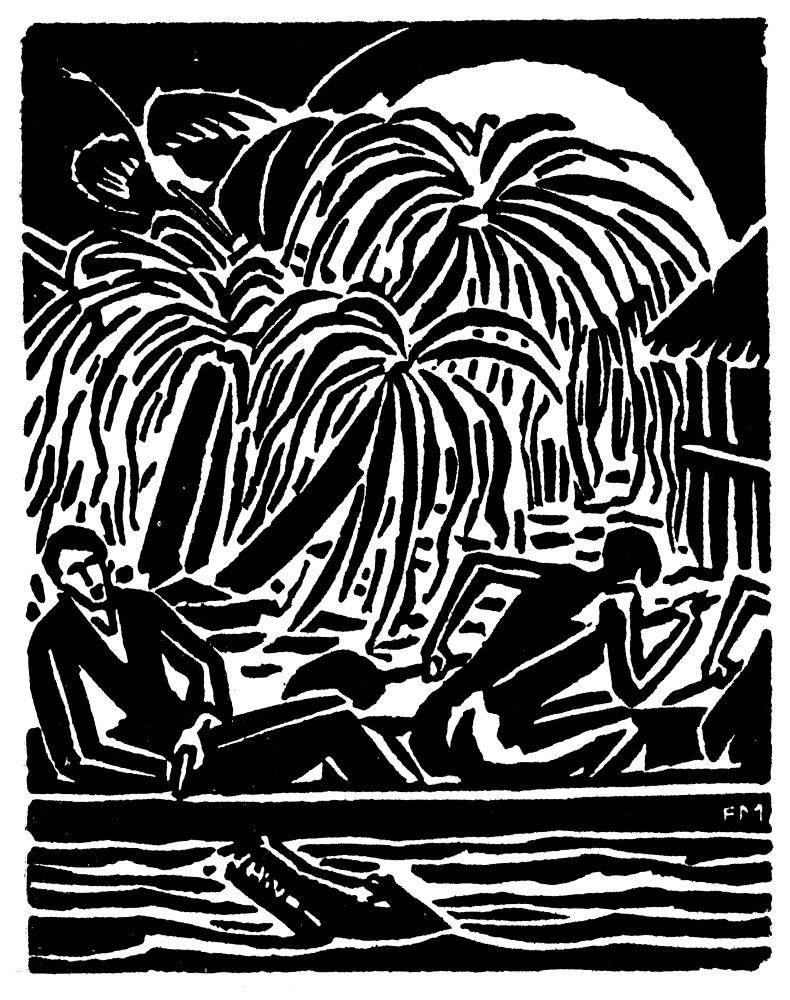

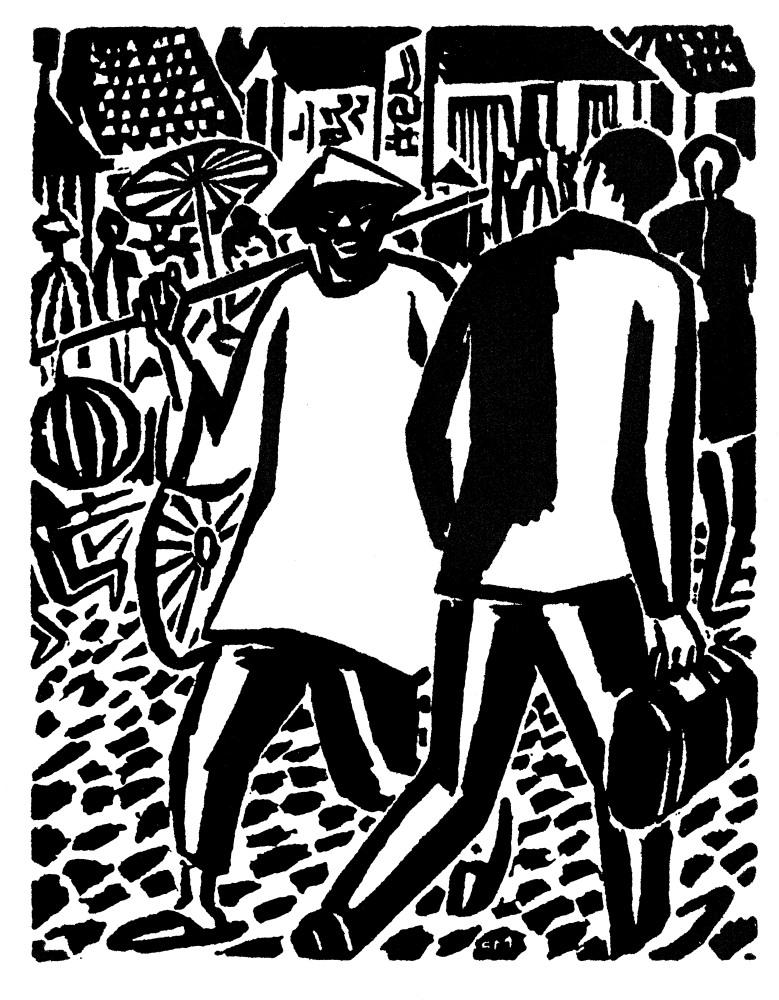

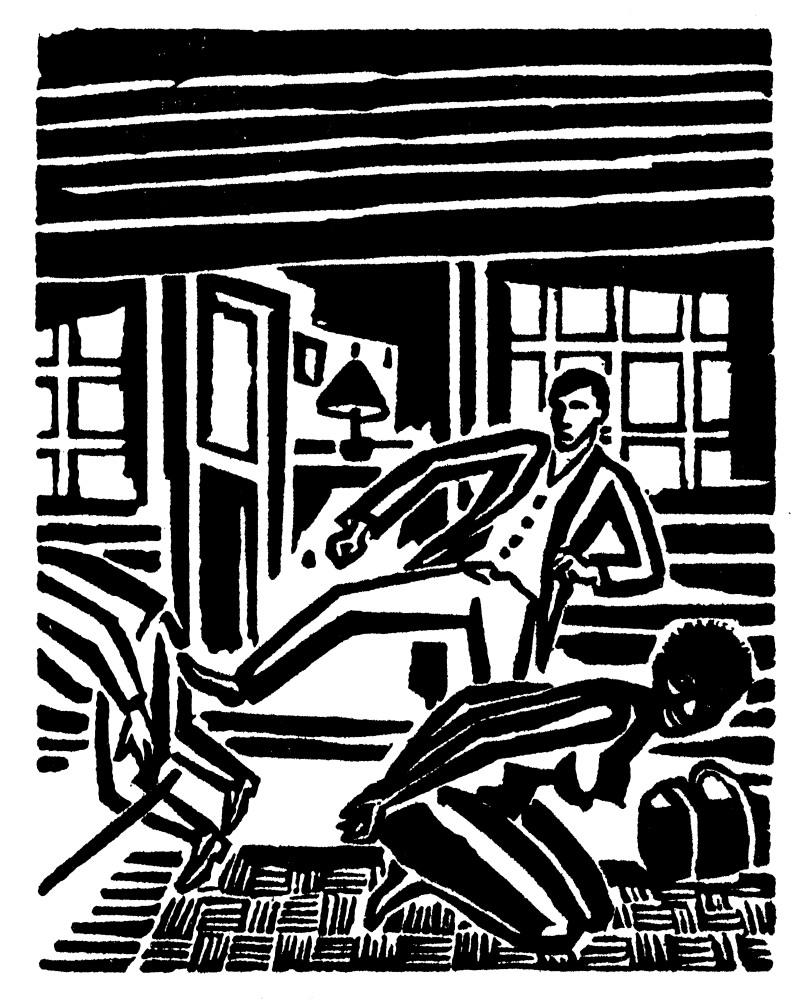

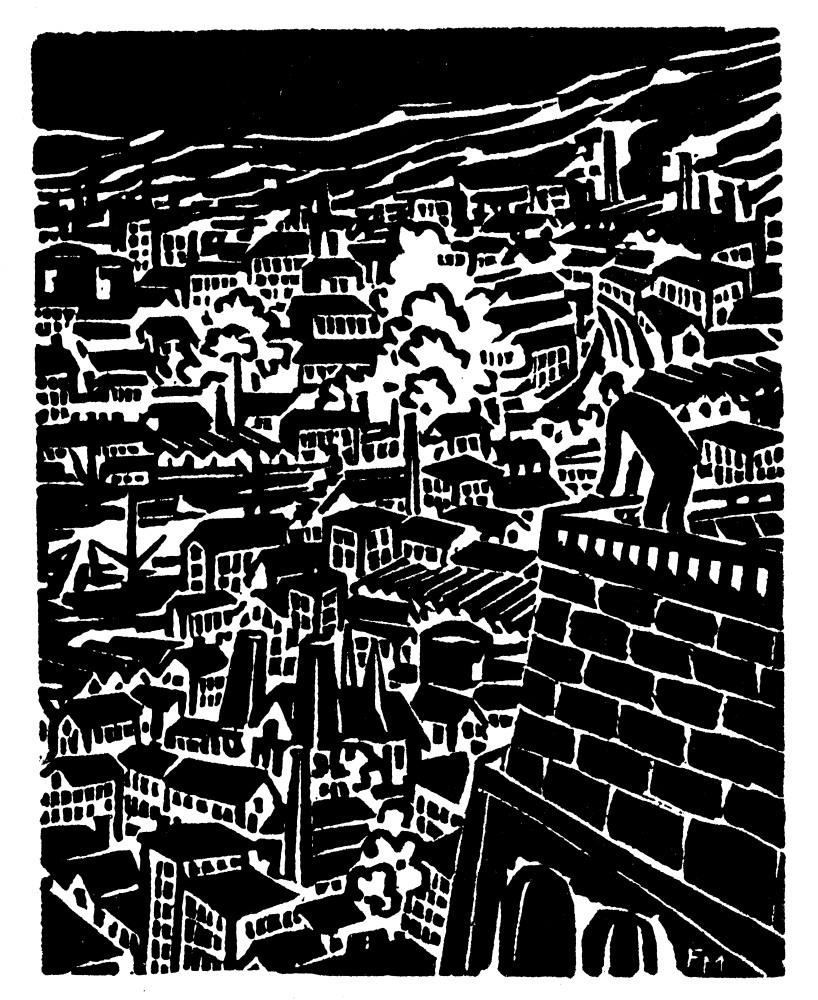

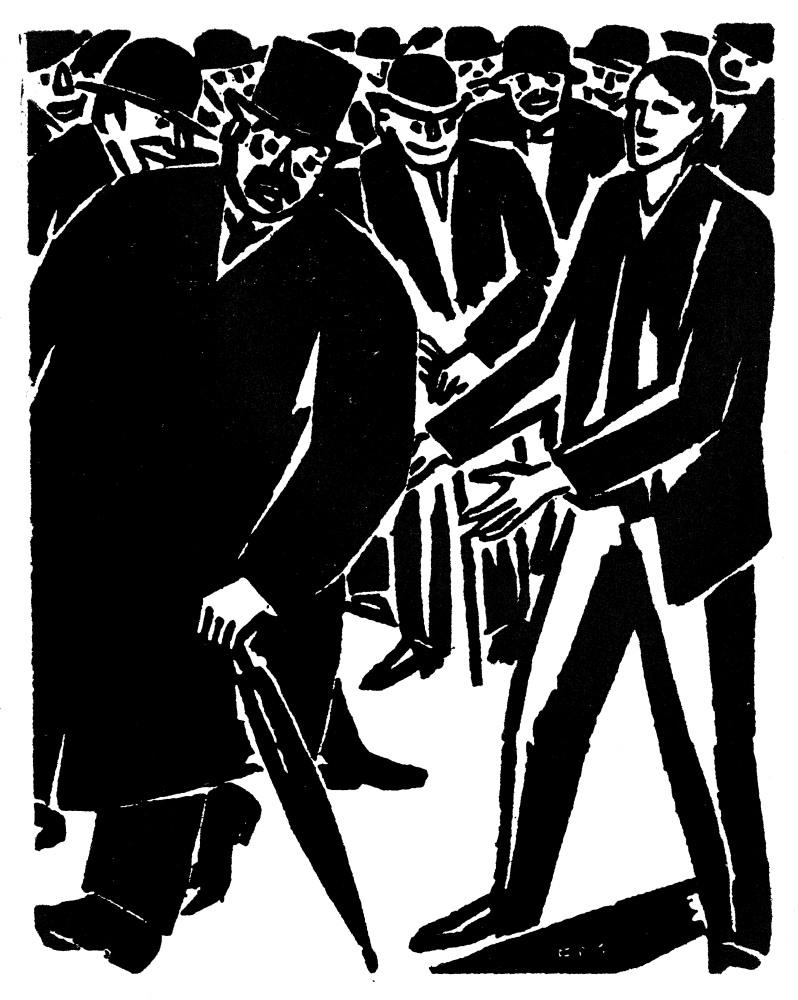

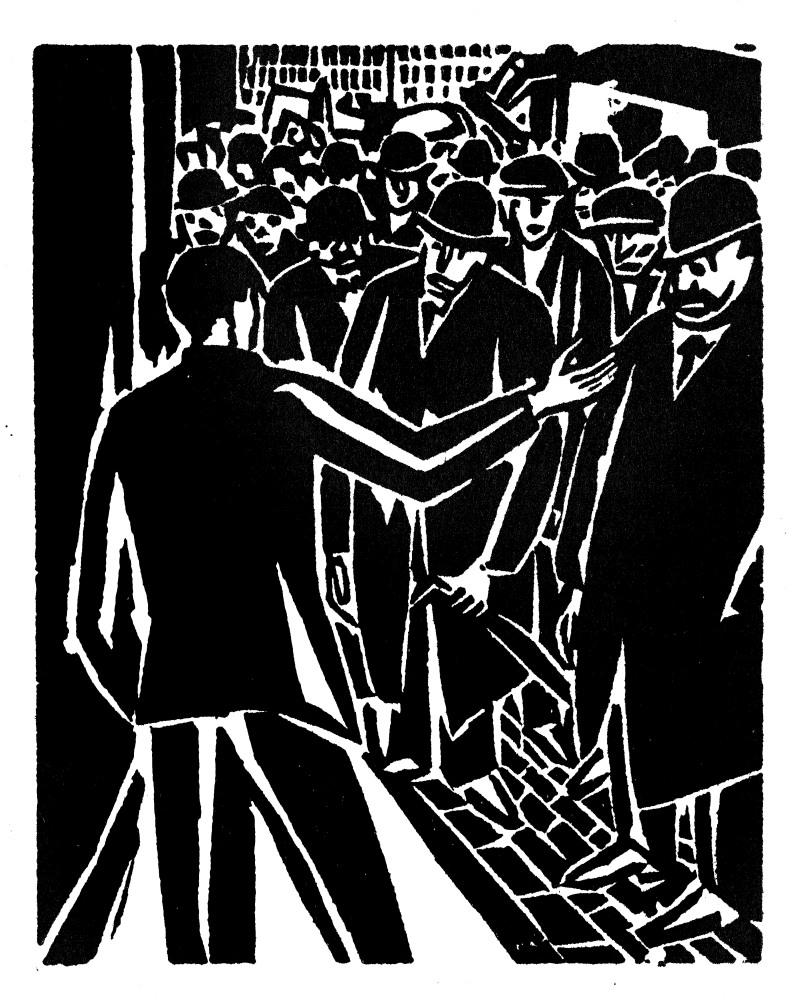

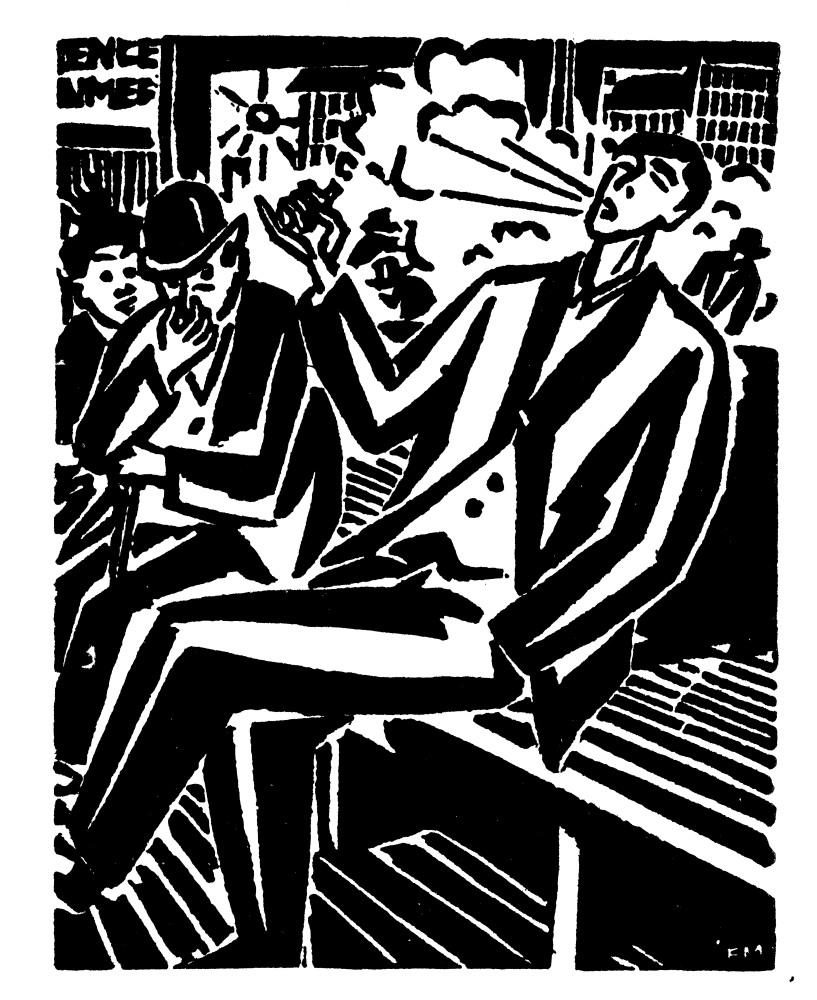

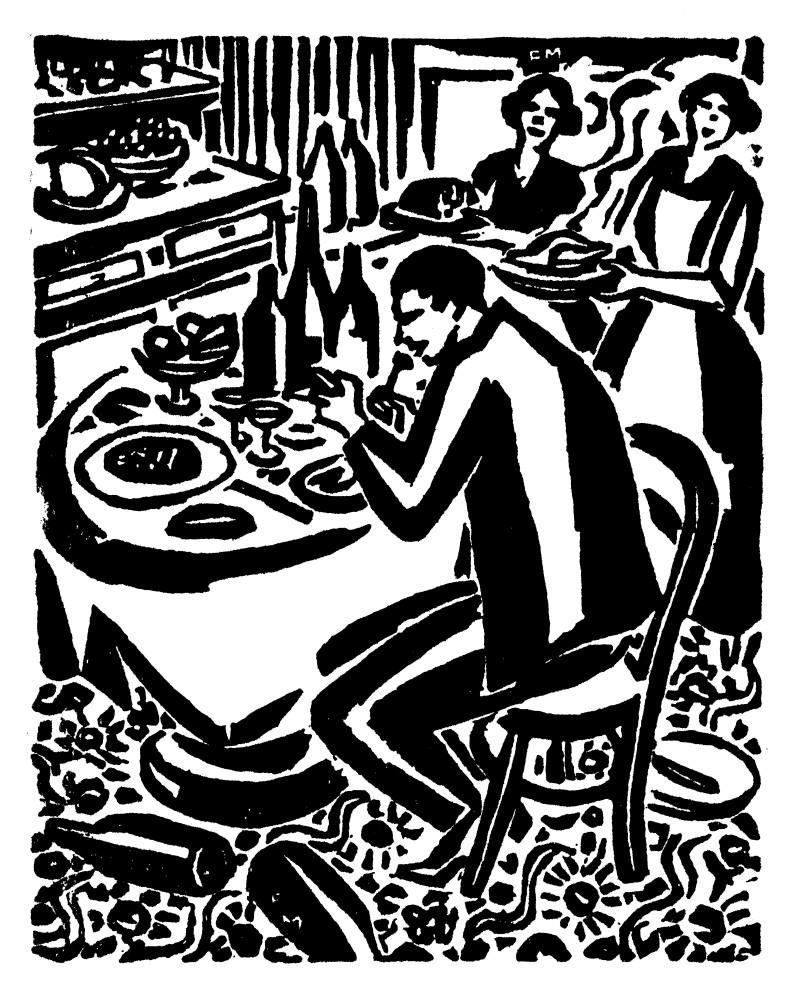

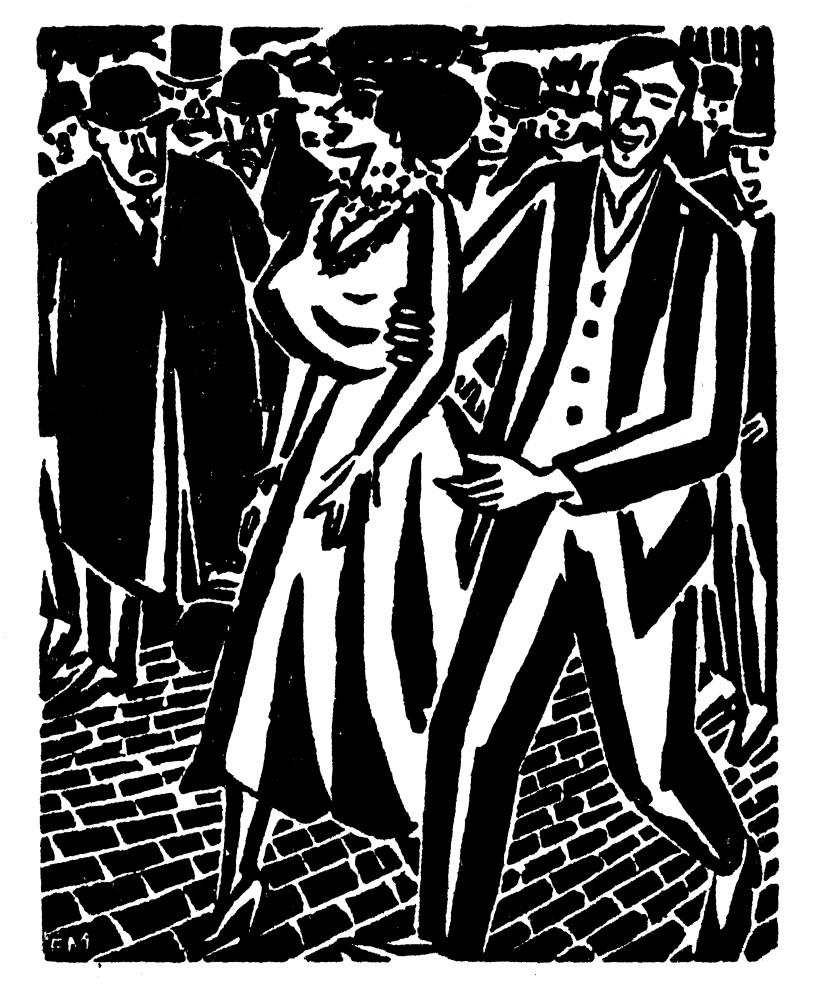

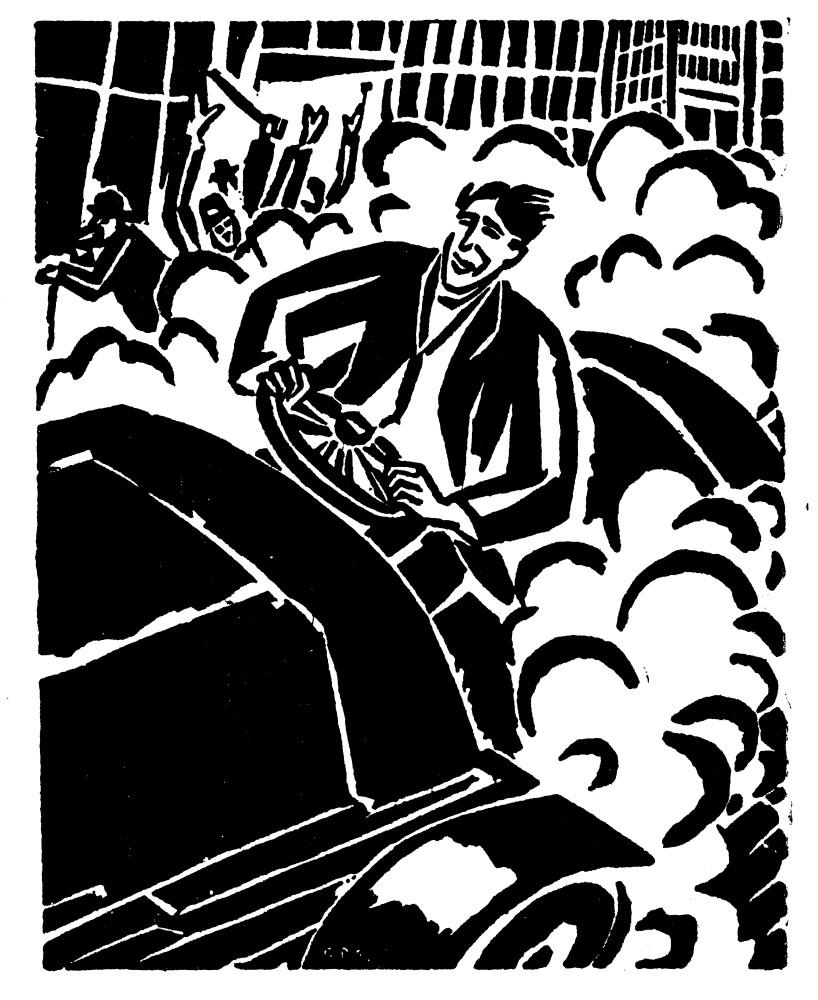

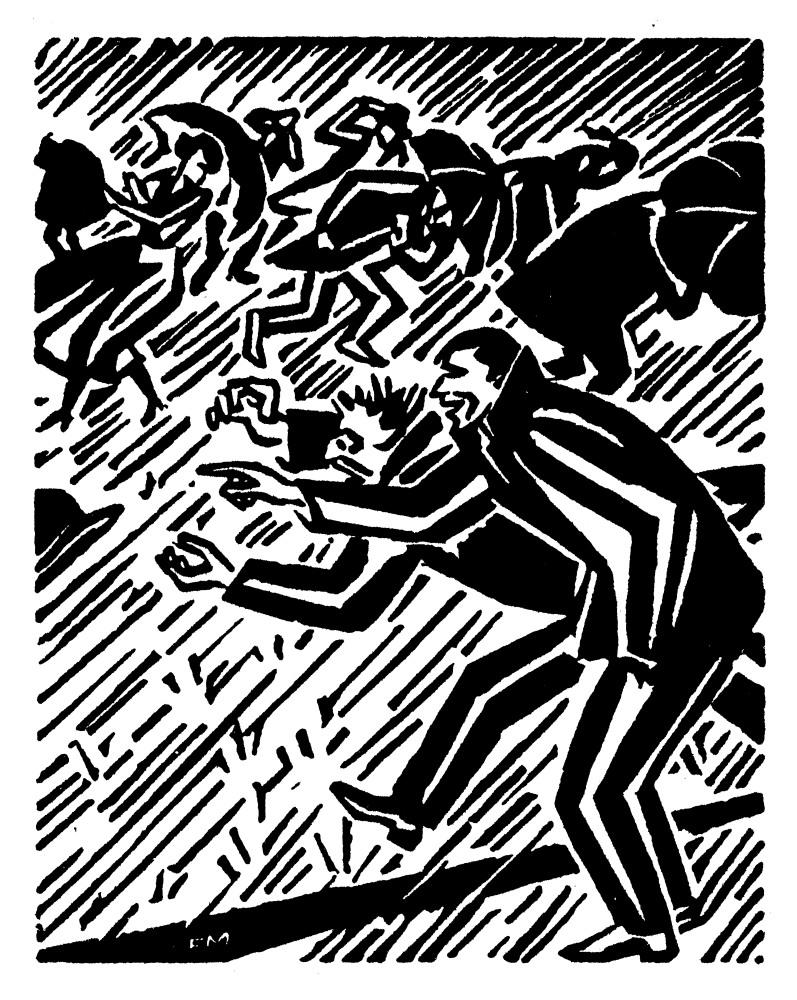

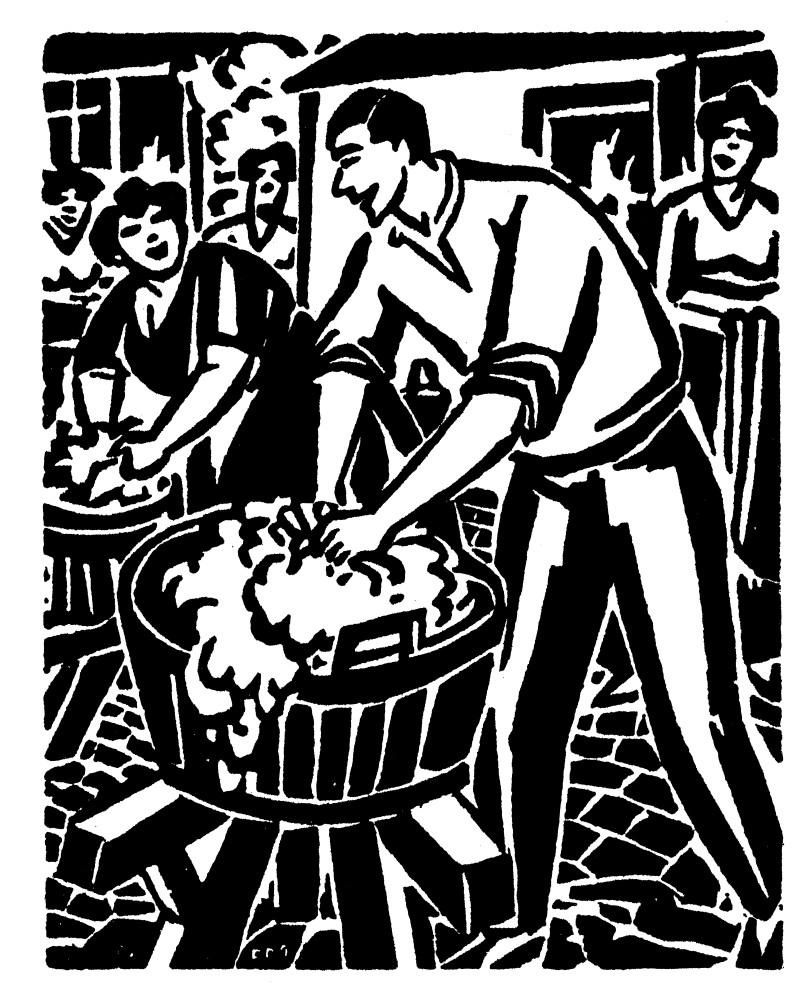

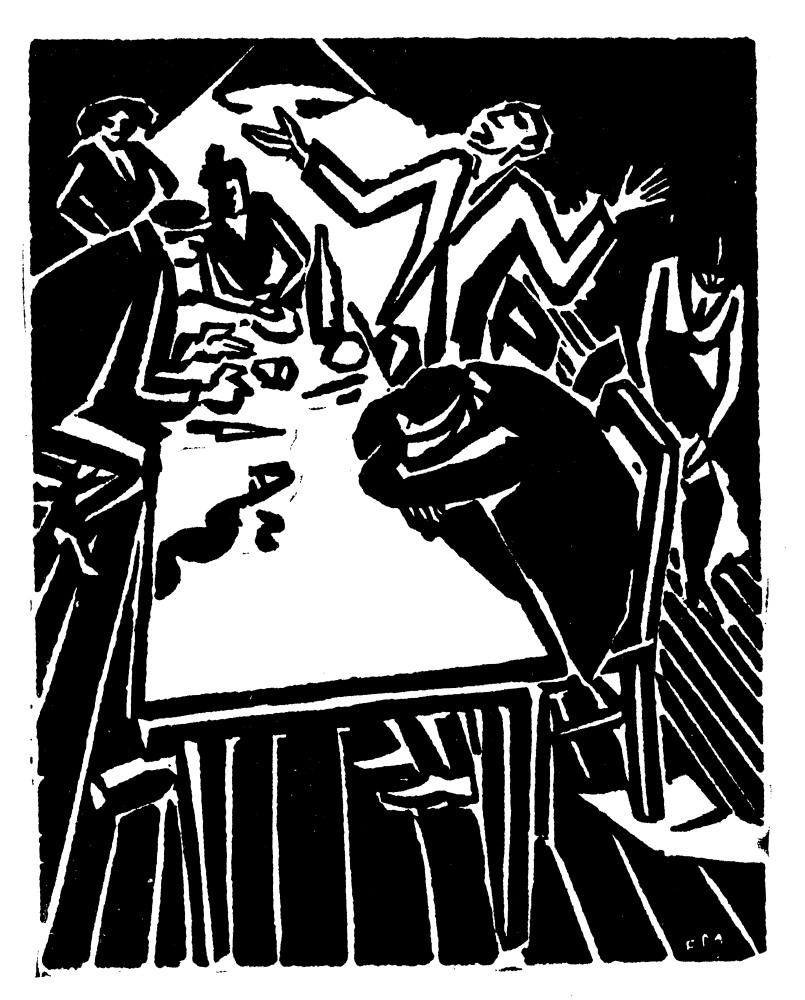

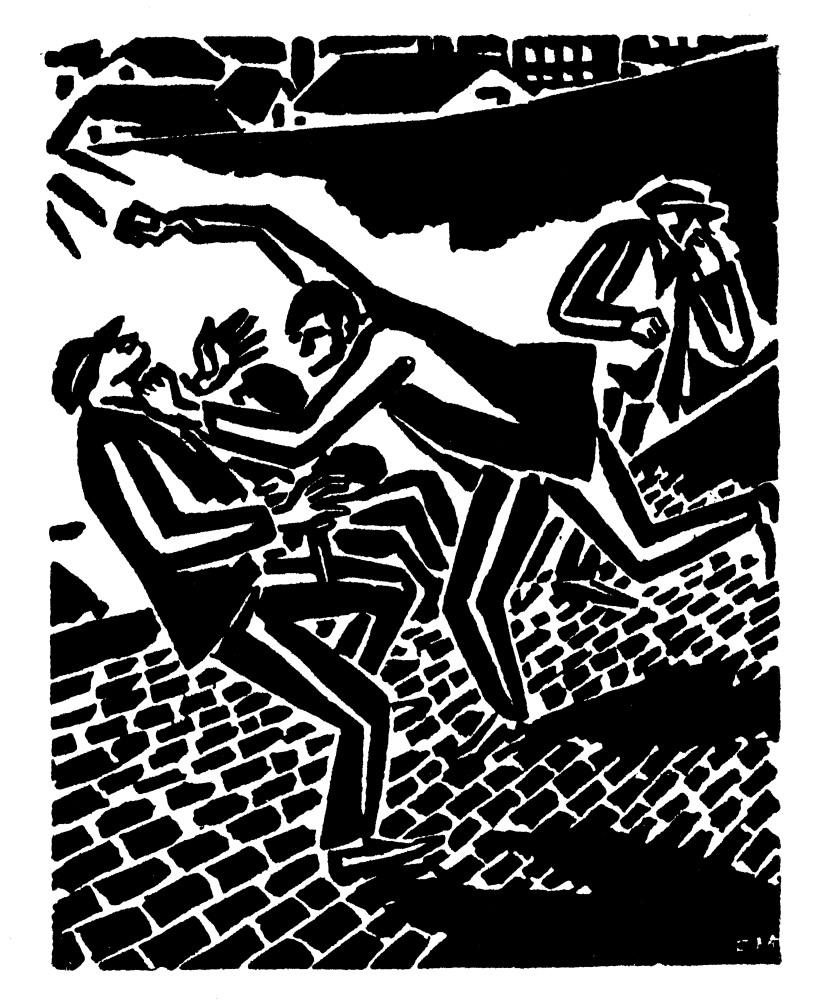

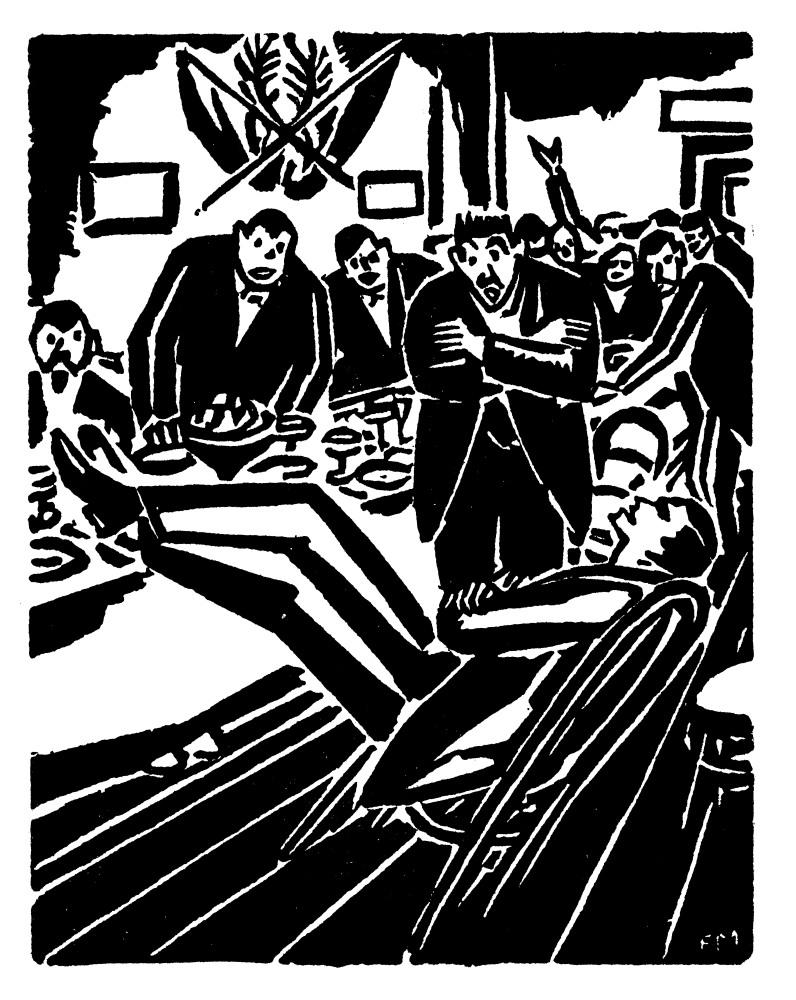

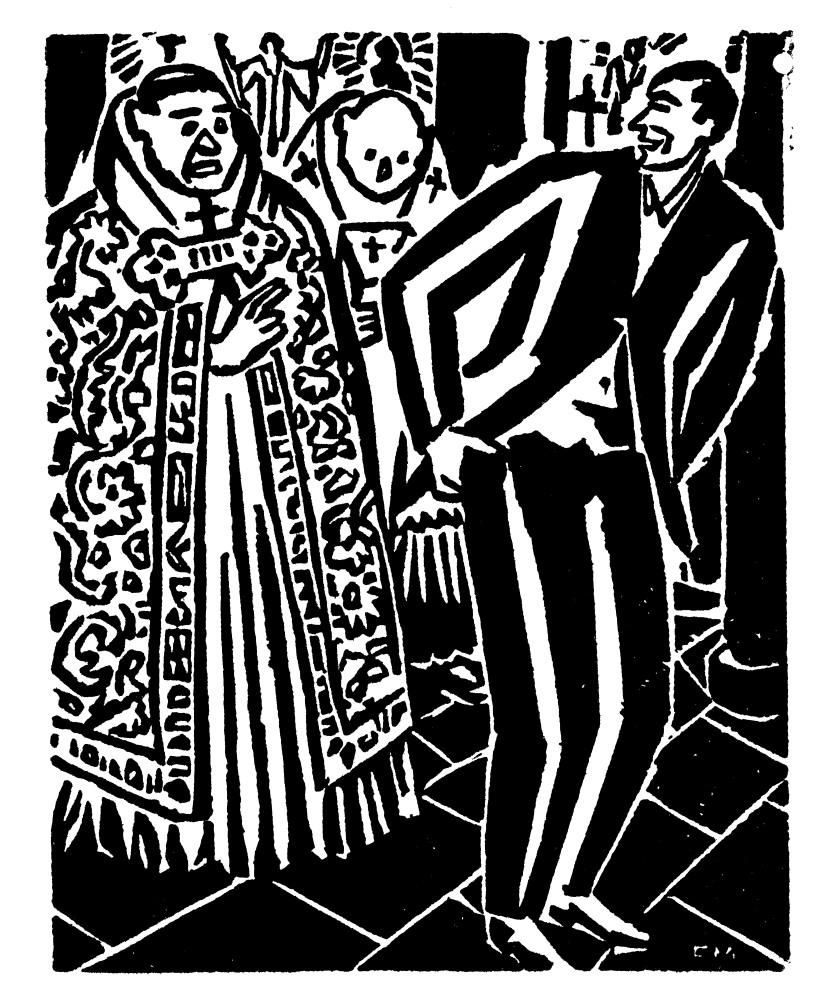

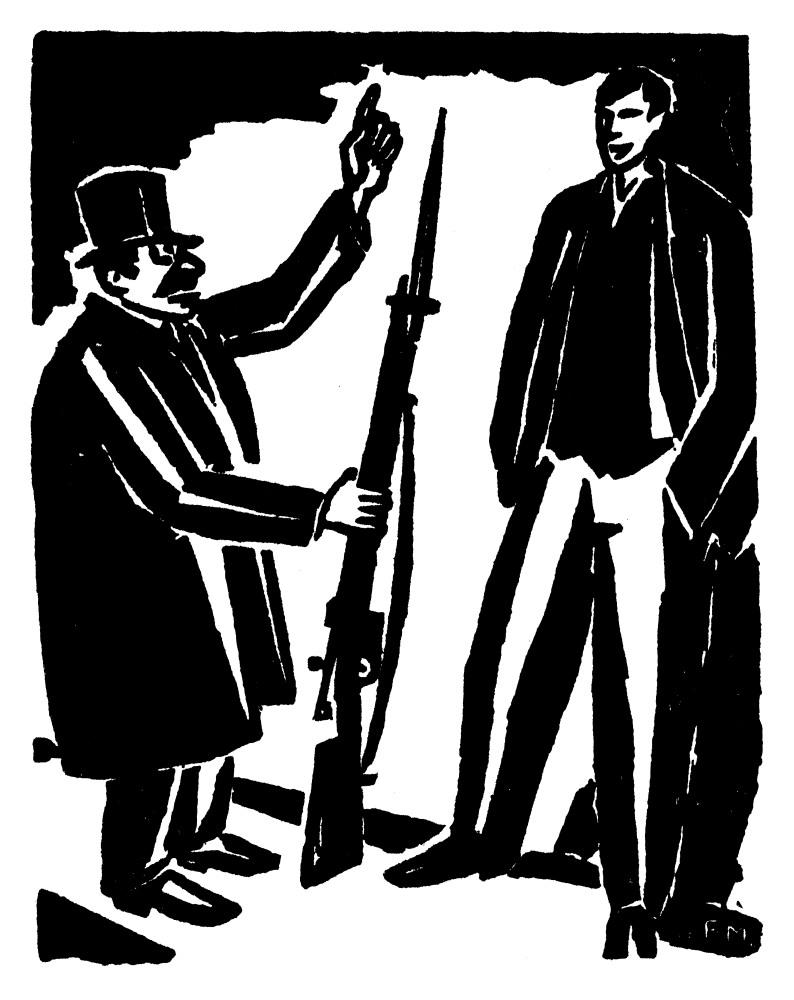

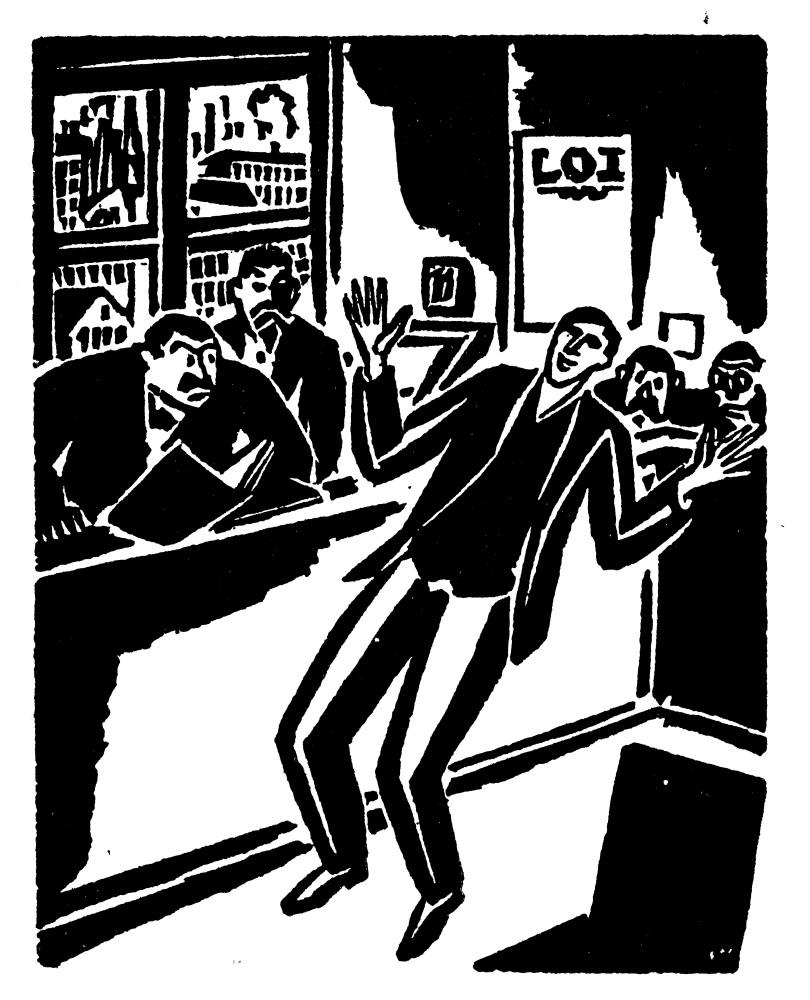

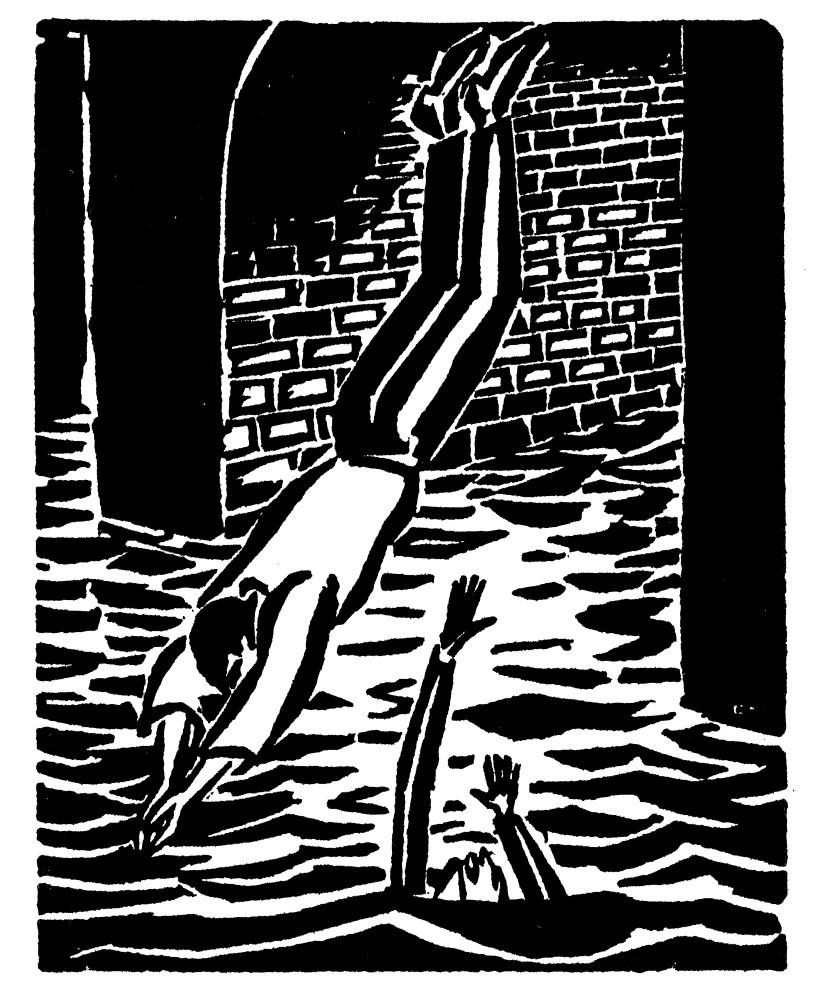

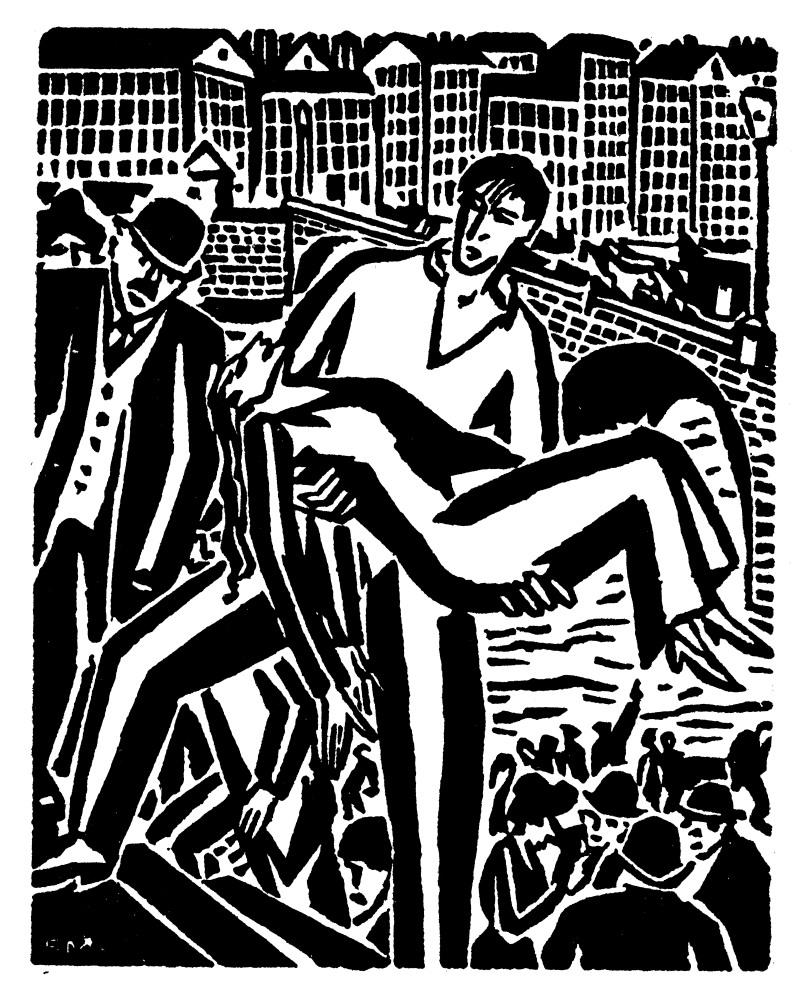

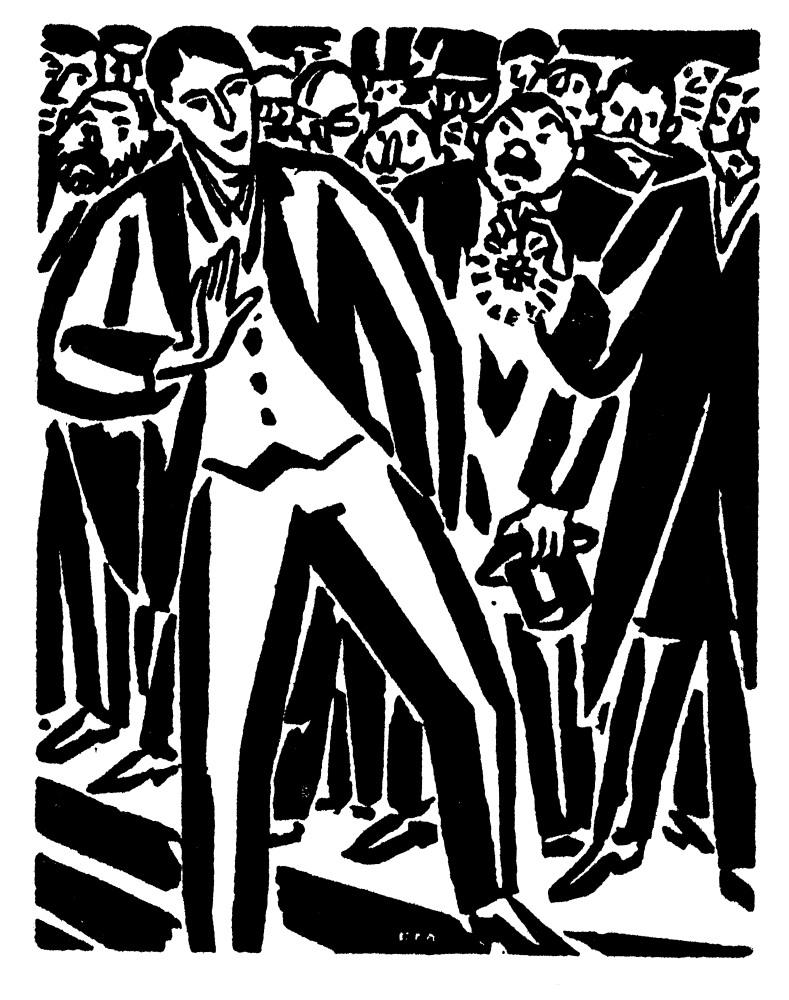

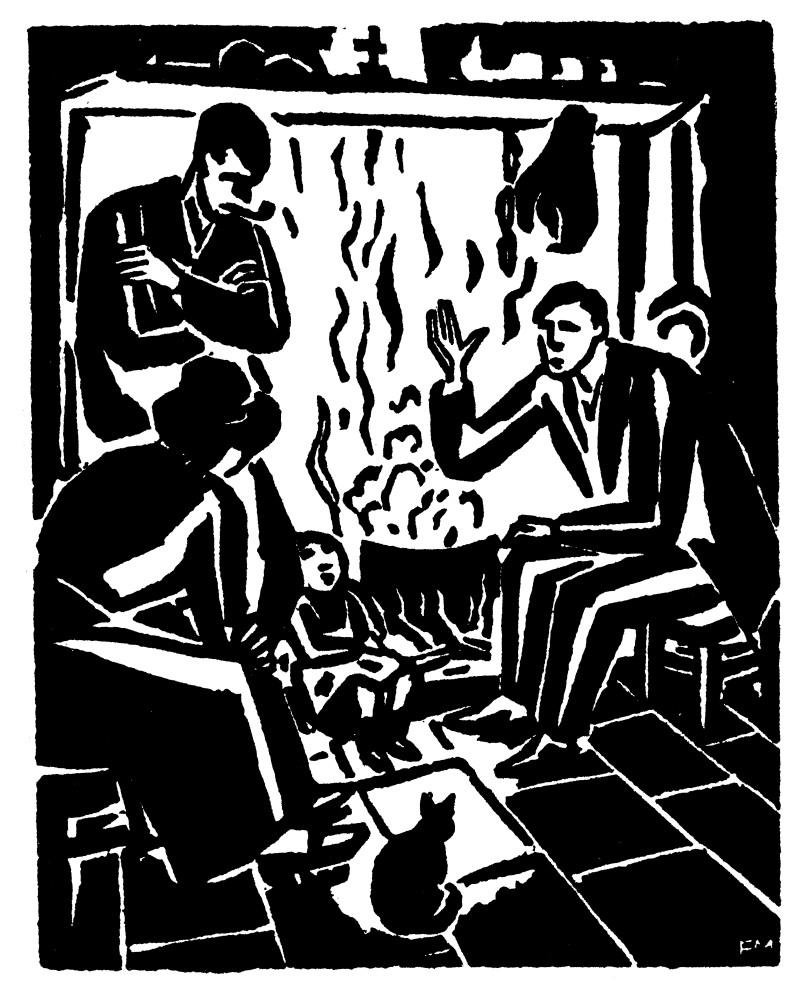

Our blood-stained era, which concealed under the guise of heroism and idealism so much cruelty and so much hypocrisy, demanded the flaying stroke of a Daumier or a Goya. Masereel is of their line. His drawings, which appeared daily during several years in La Feuille de Genewe, “Rise, Ye Dead!” and “The Dead Speak” are works of retribution, cries of outraged sorrow that will reverberate down the ages. Those momentous works, of a ghastly power, testify to the sufferings through which the soul of the poet was passing. It was inevitable that he should succumb. The spectacle of death haunted him. He tried to rouse himself and turn his thoughts to life, the life of peace-time, but he found there the same oppression, the same injustices, continual warfare. He records it in one of his most admirable works, “Twenty-five Pictures of the Sufferings of a Man.” Here, the moral excellence of the protagonist-—a simple workman-—triumphs over the cares and fears of social life, and fixes the stamp of his sturdy judgment on the courts which try and convict him. A sublime melancholy pervades this virile tragedy.

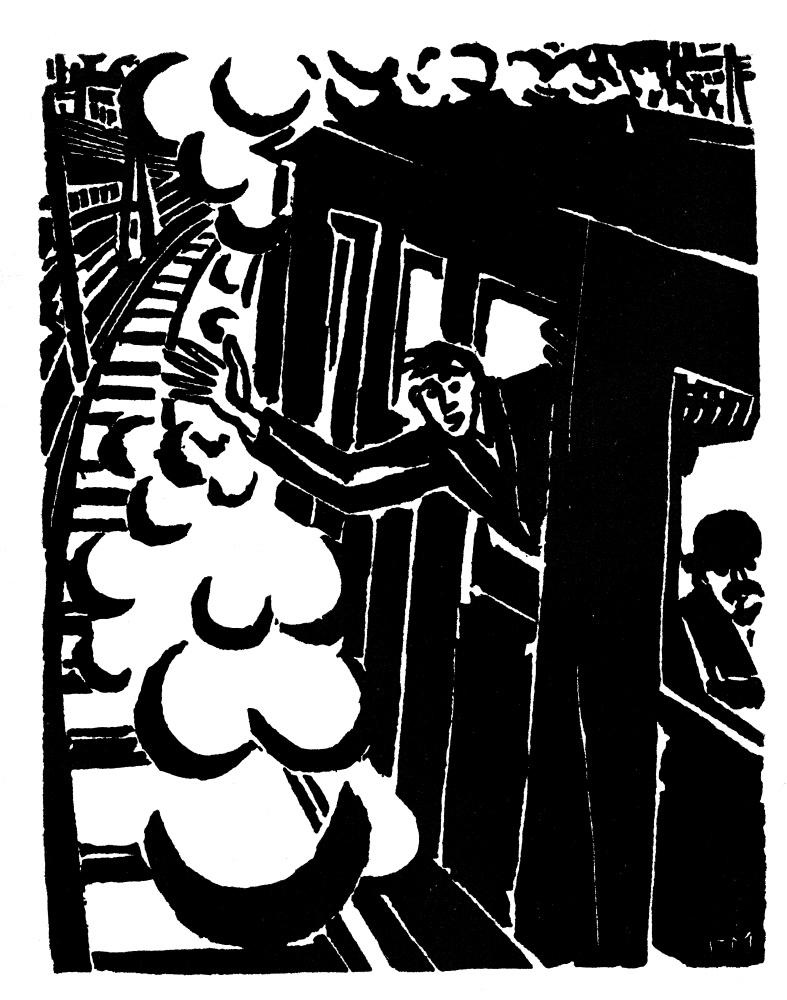

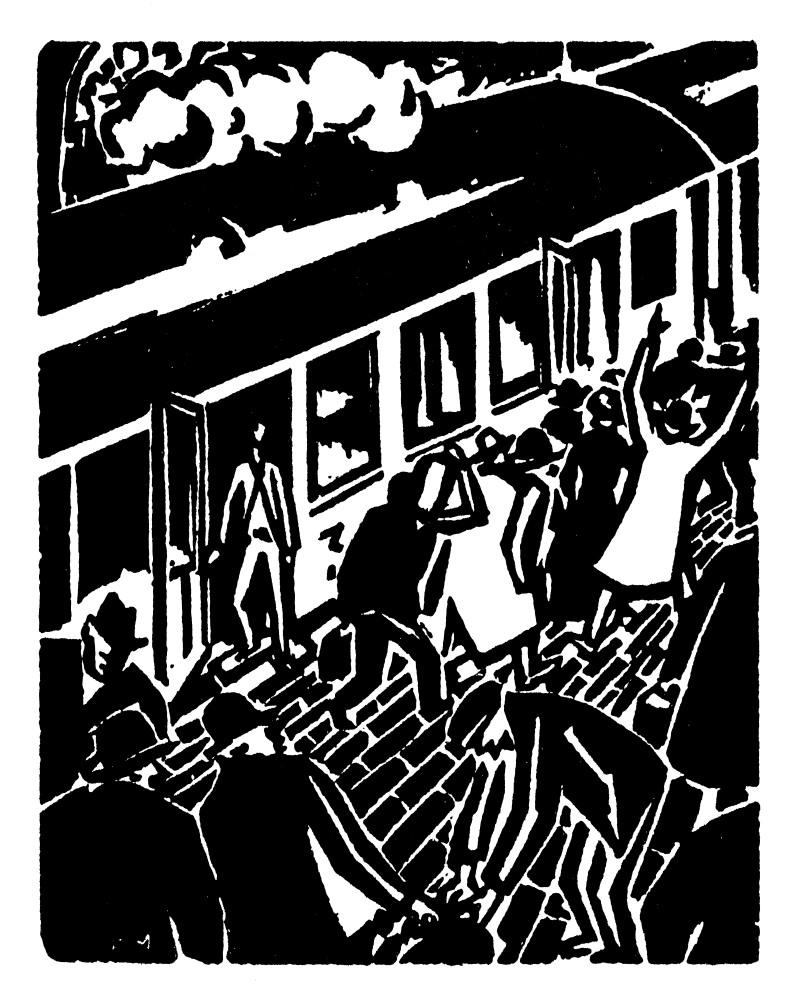

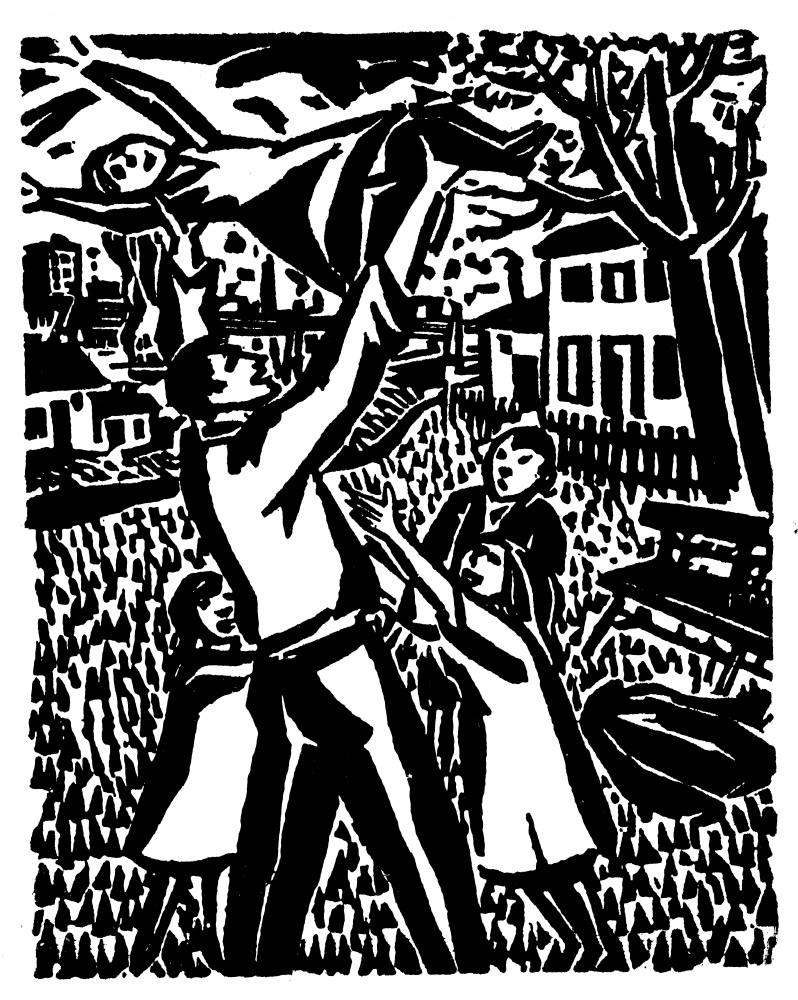

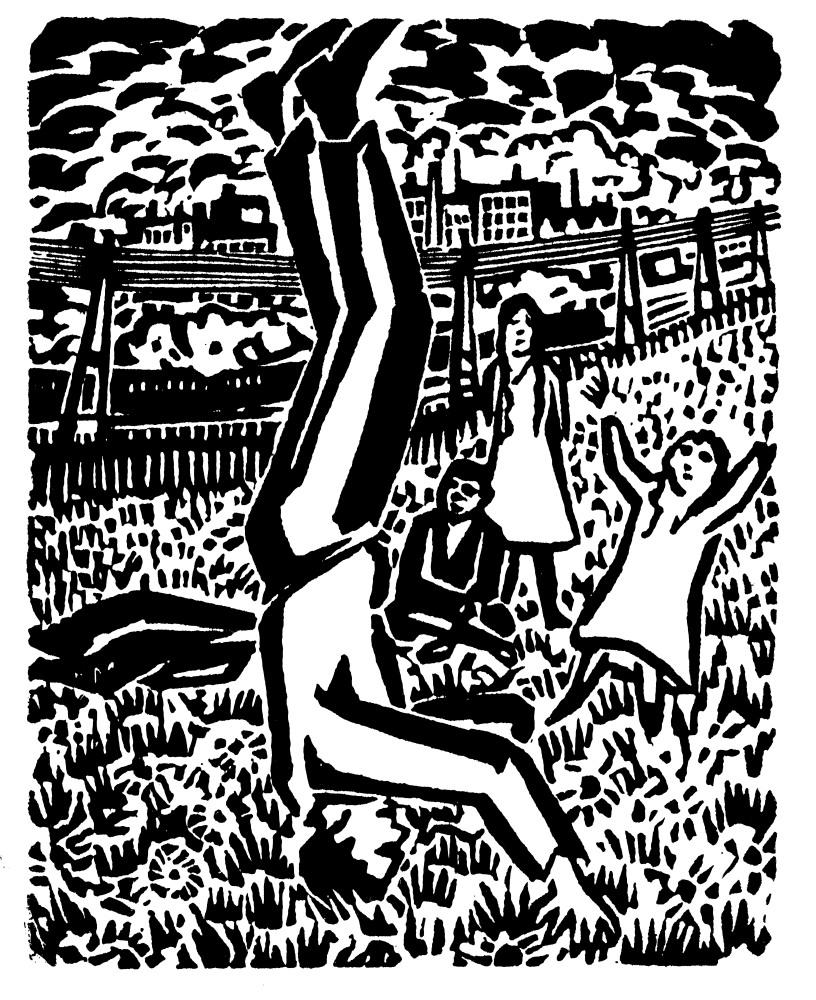

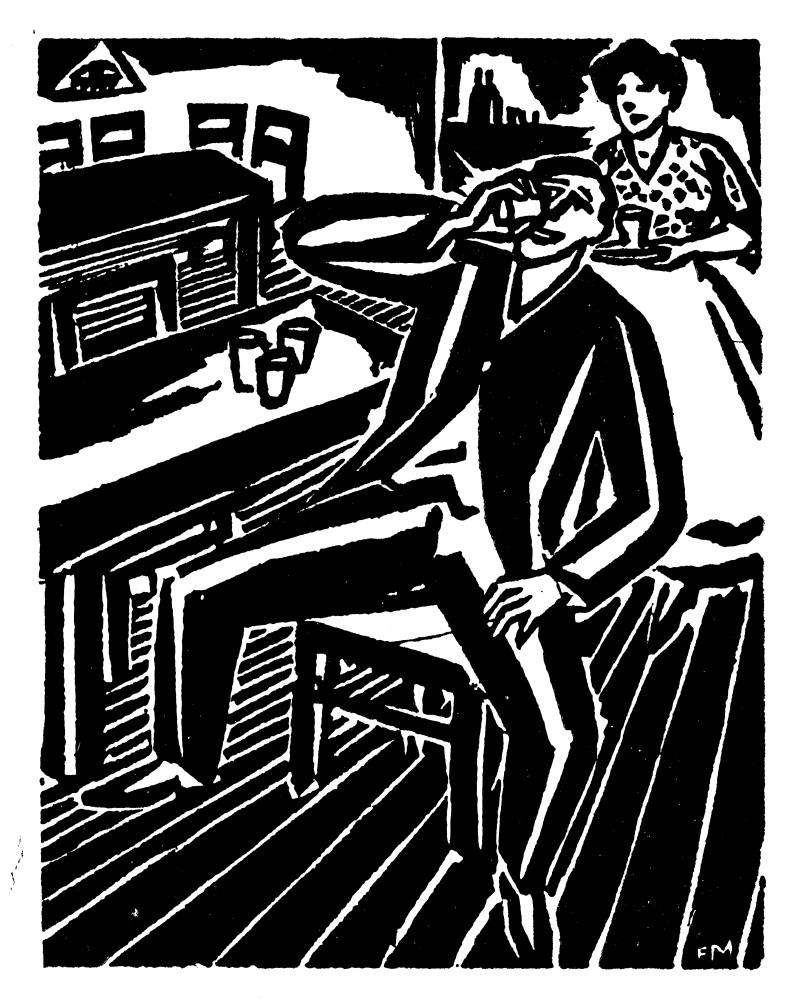

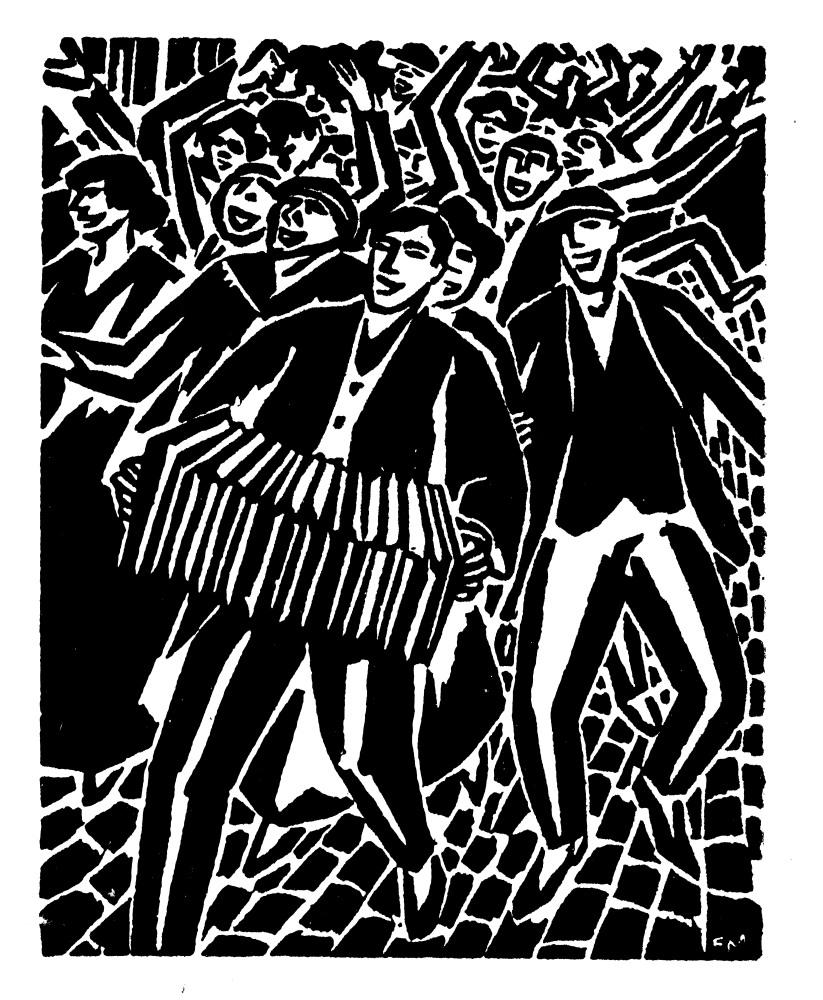

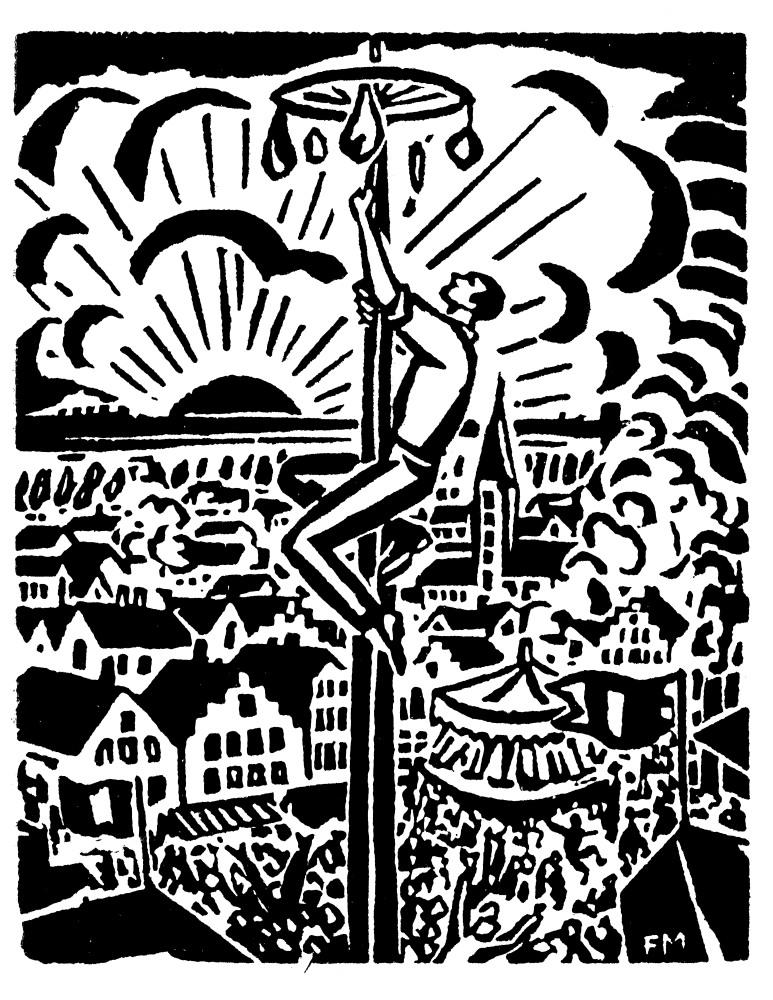

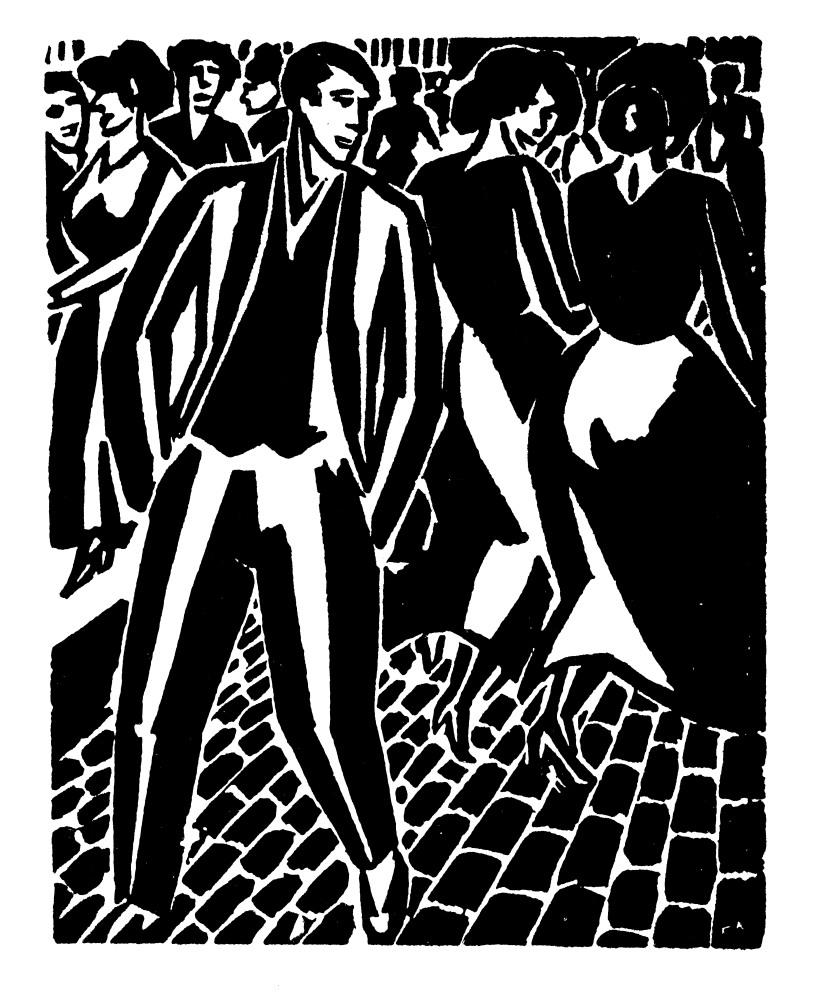

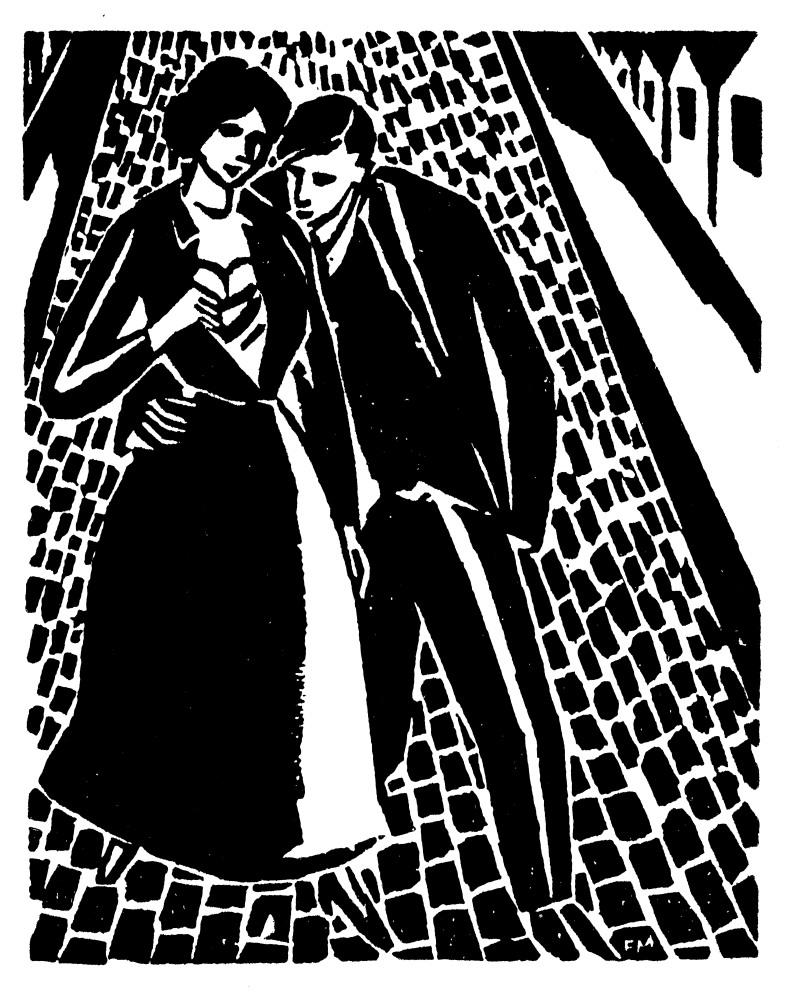

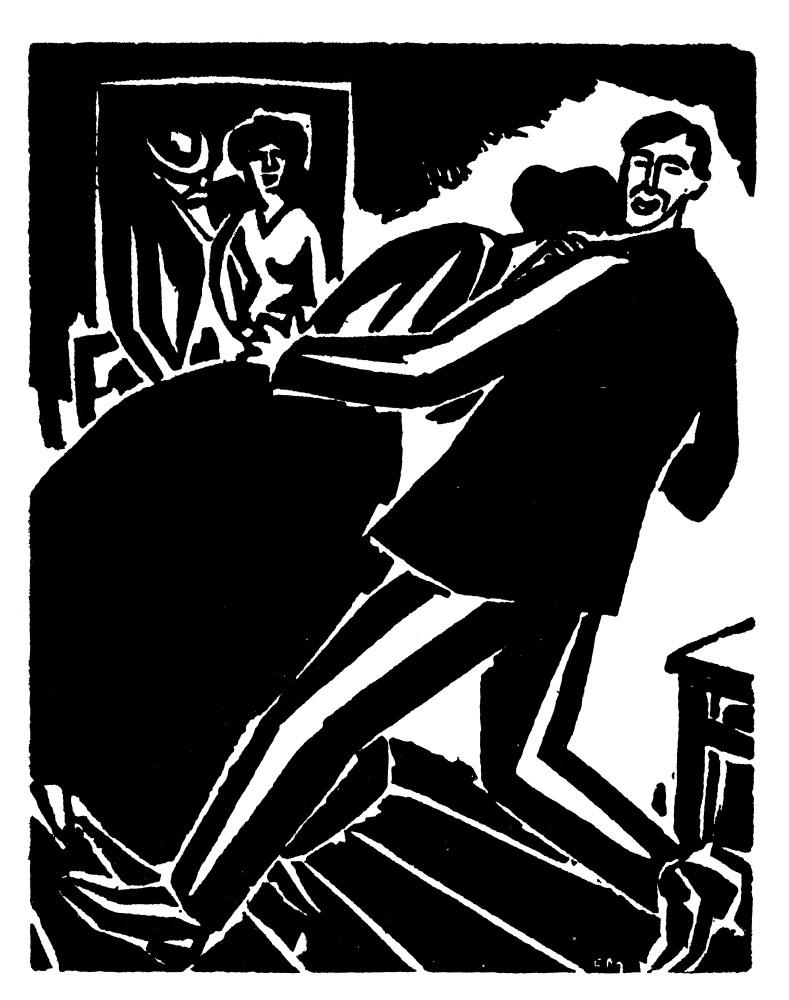

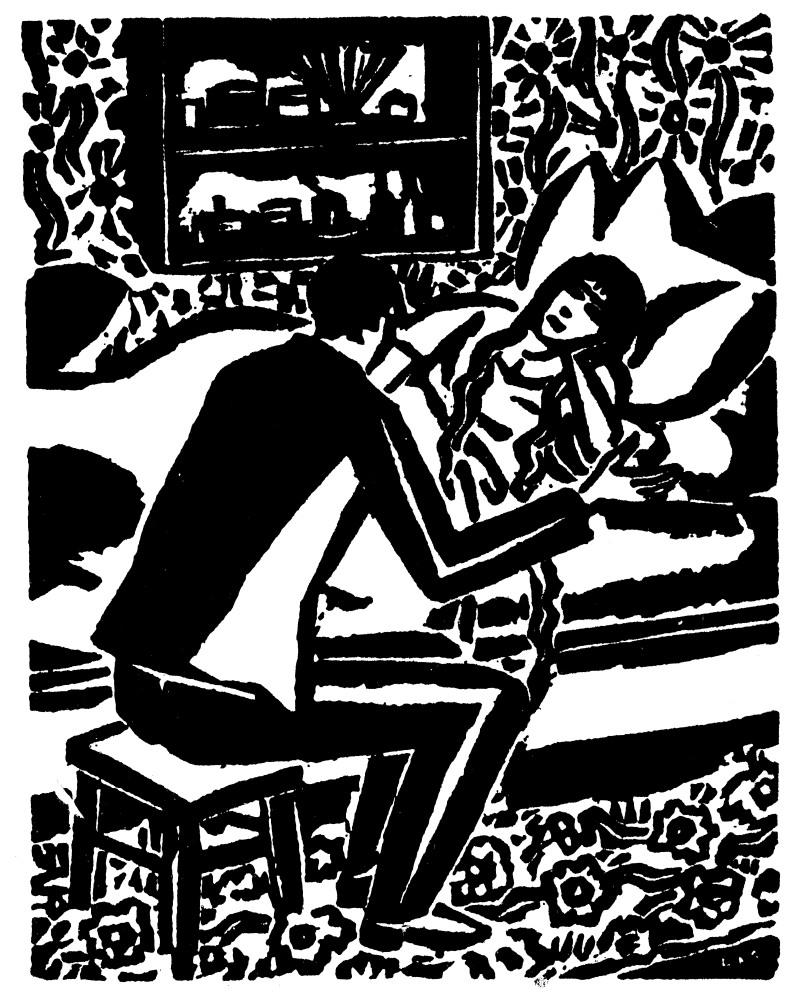

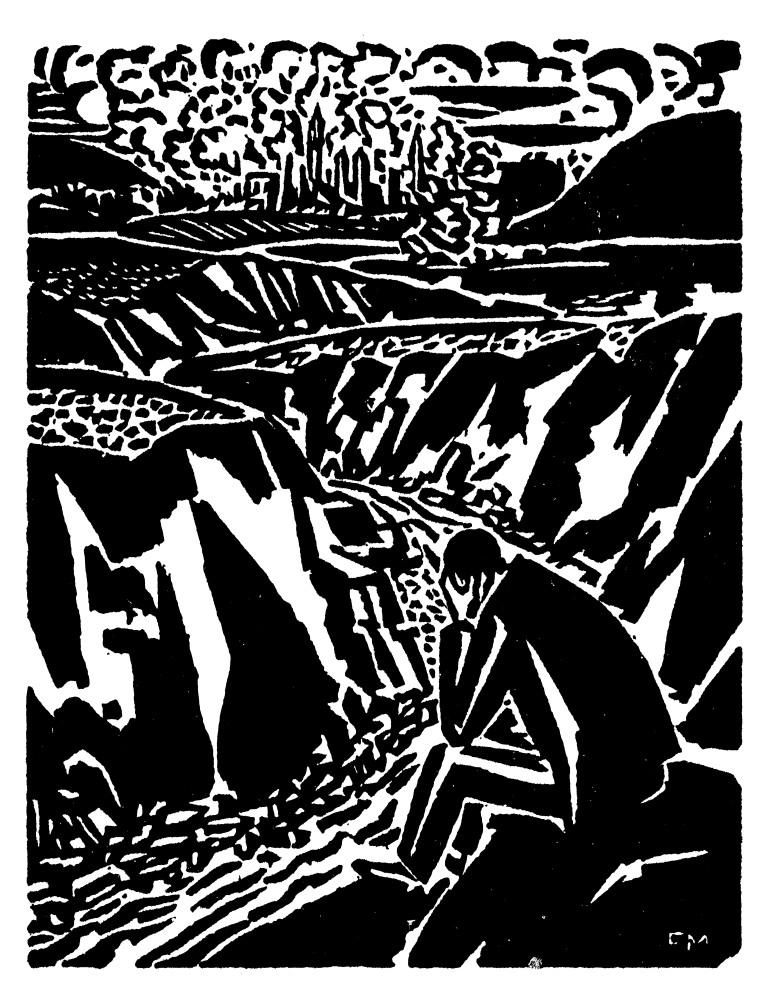

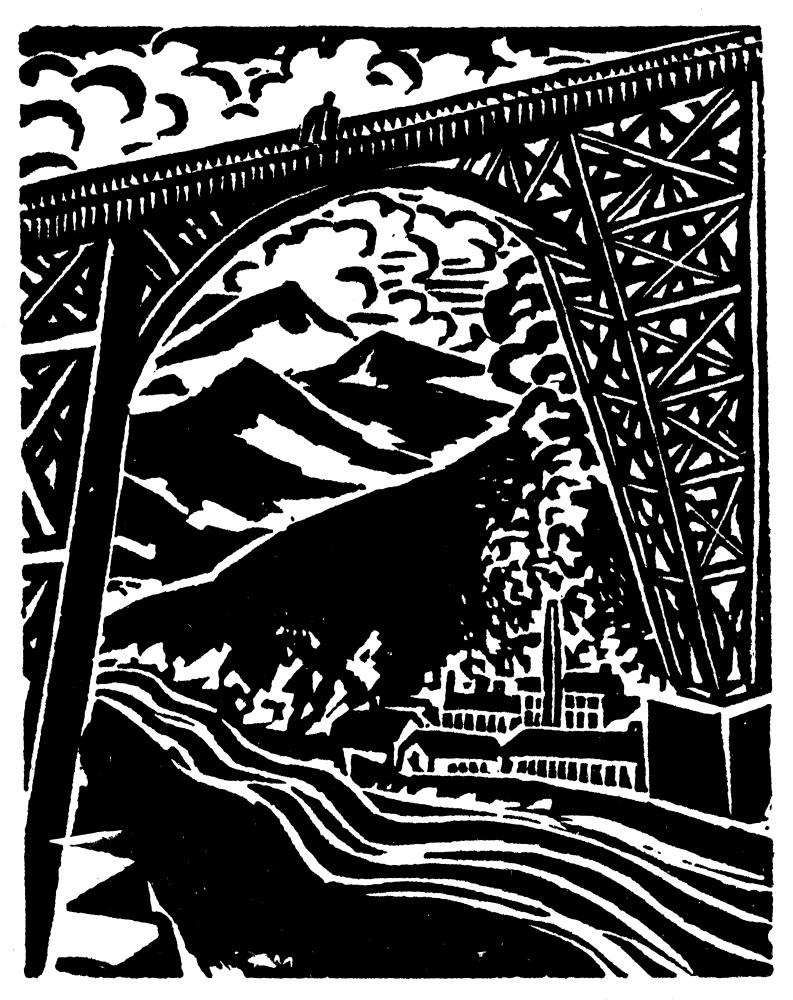

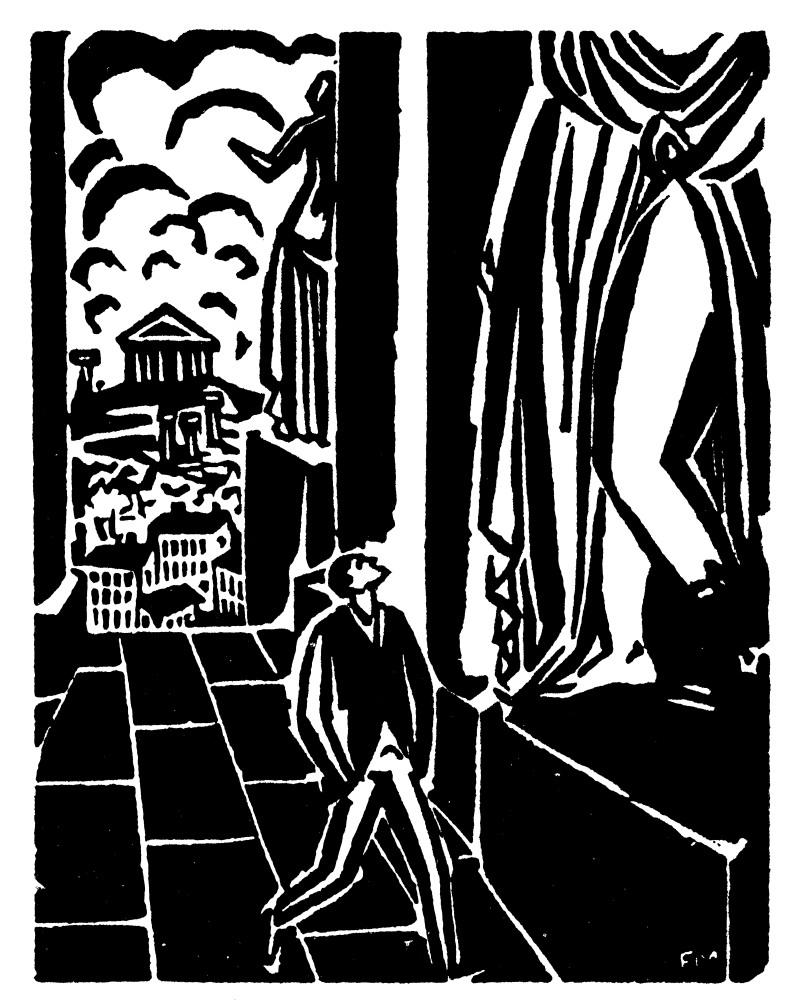

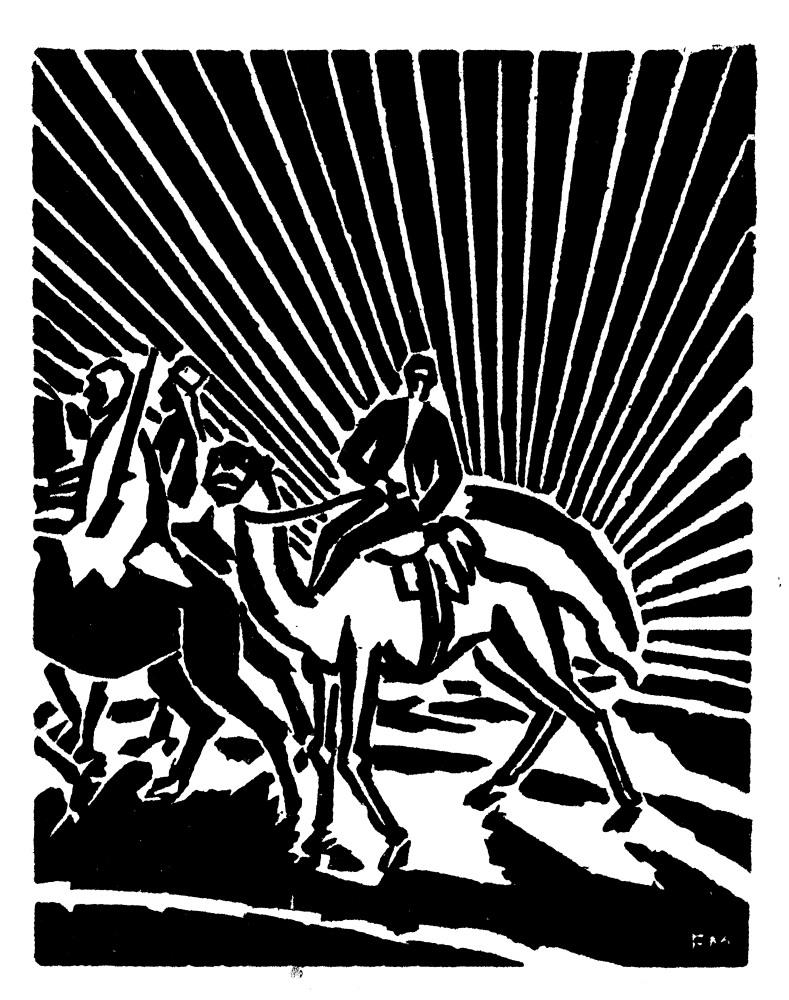

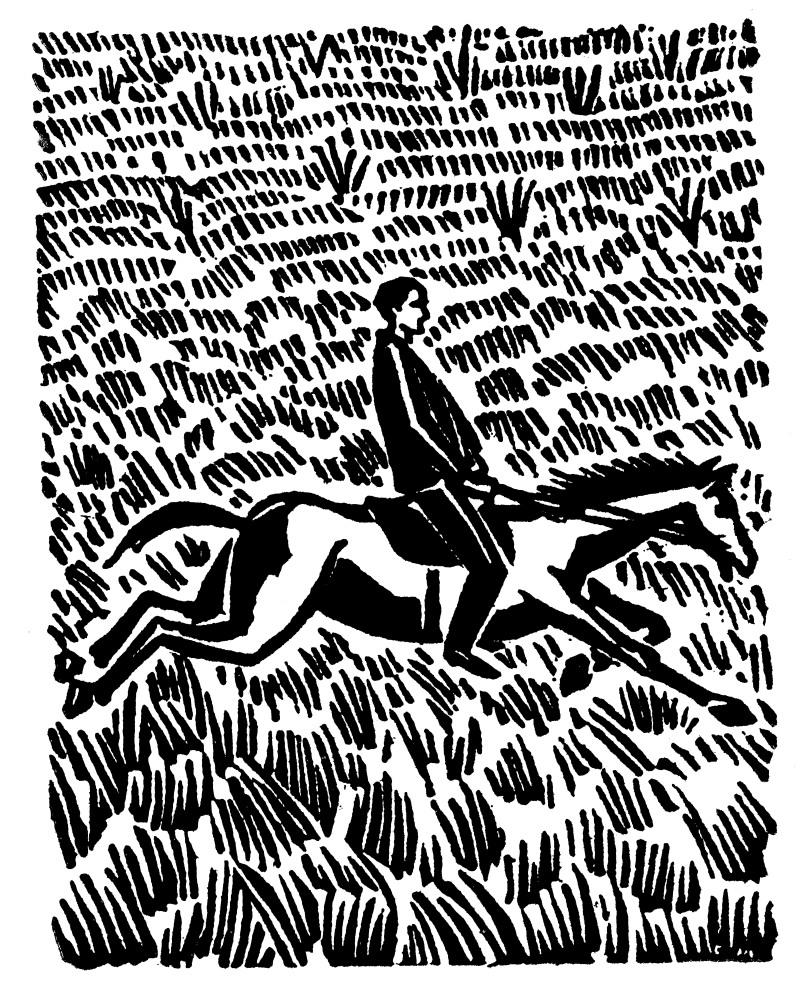

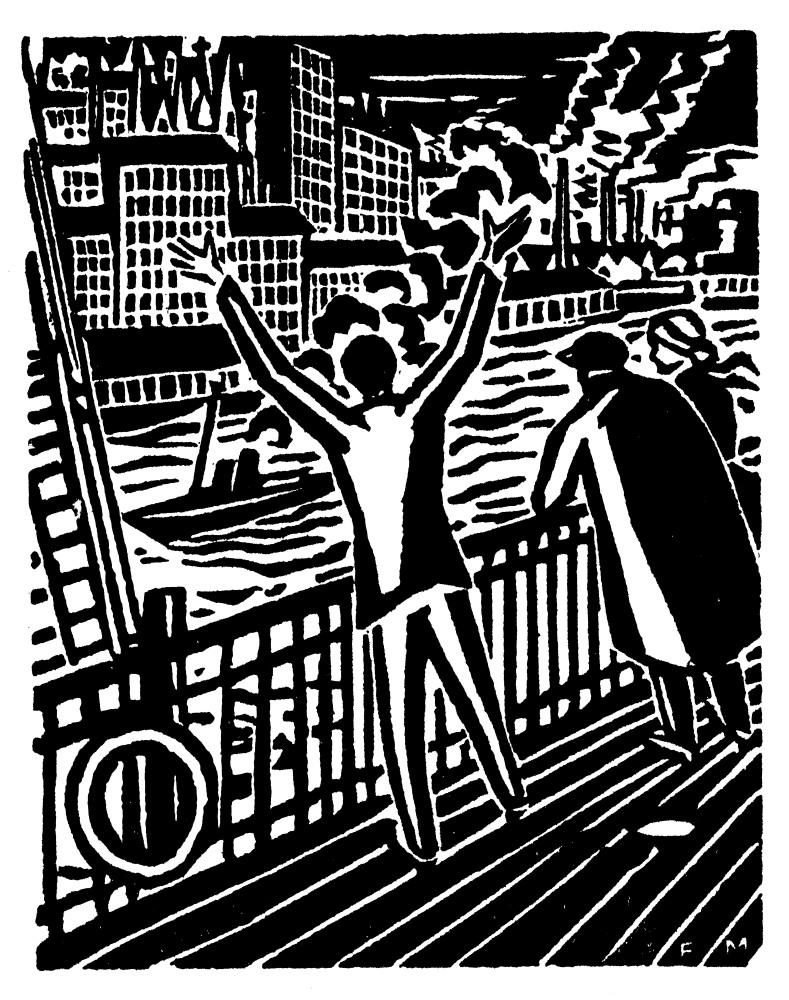

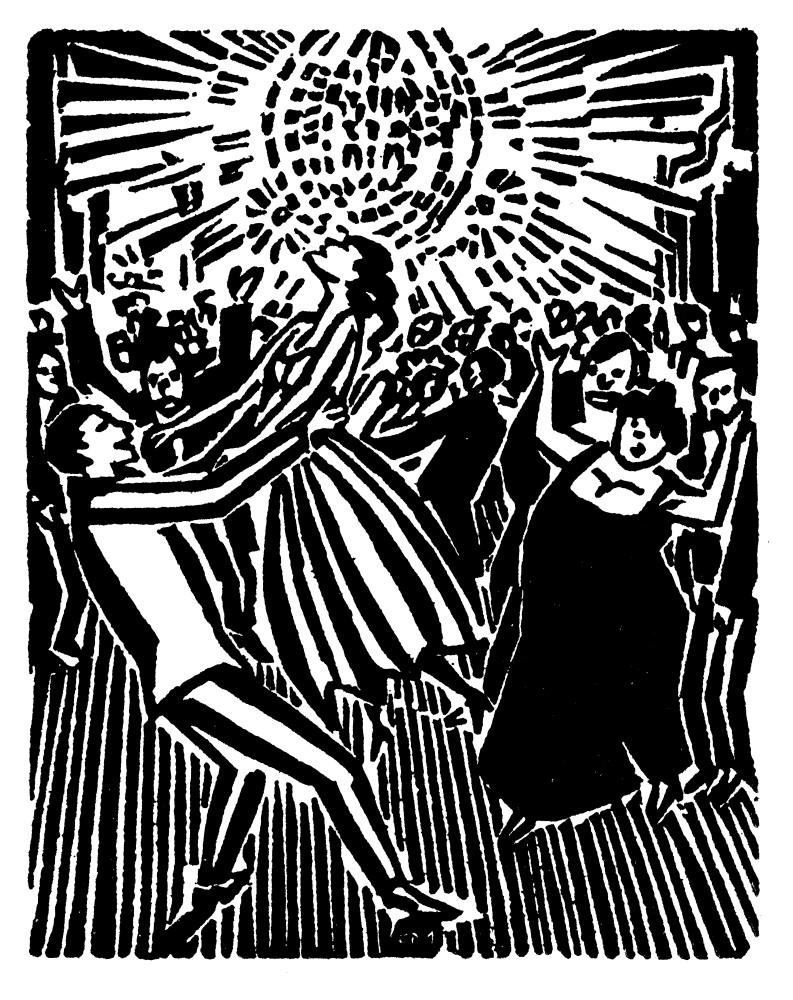

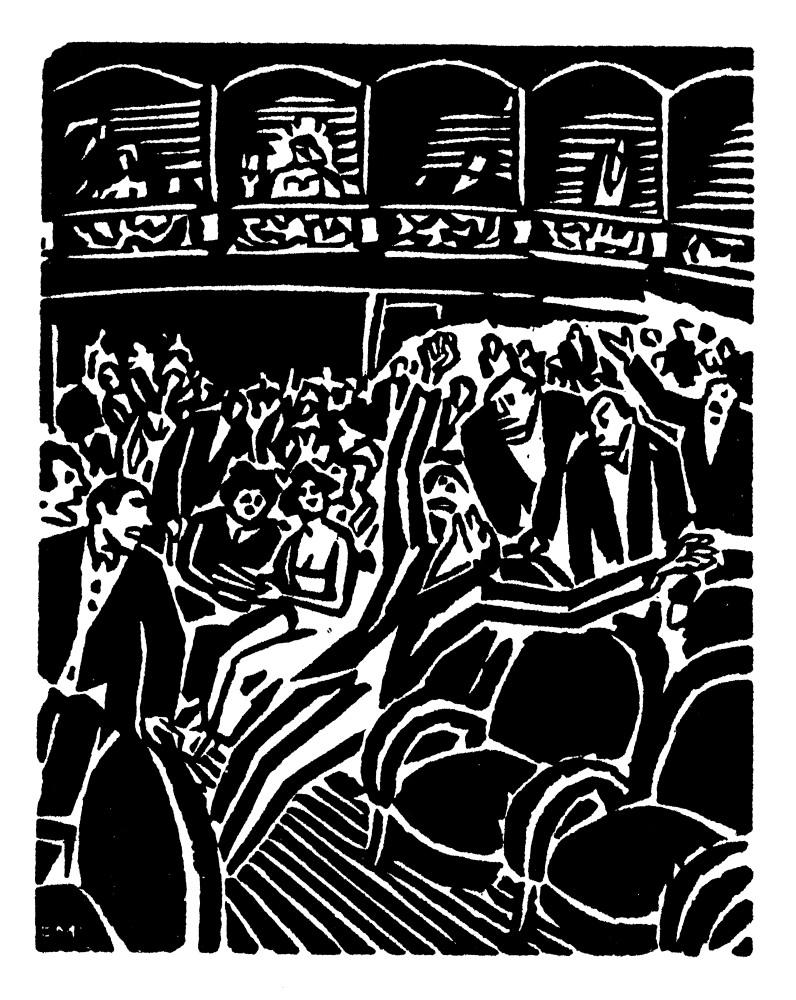

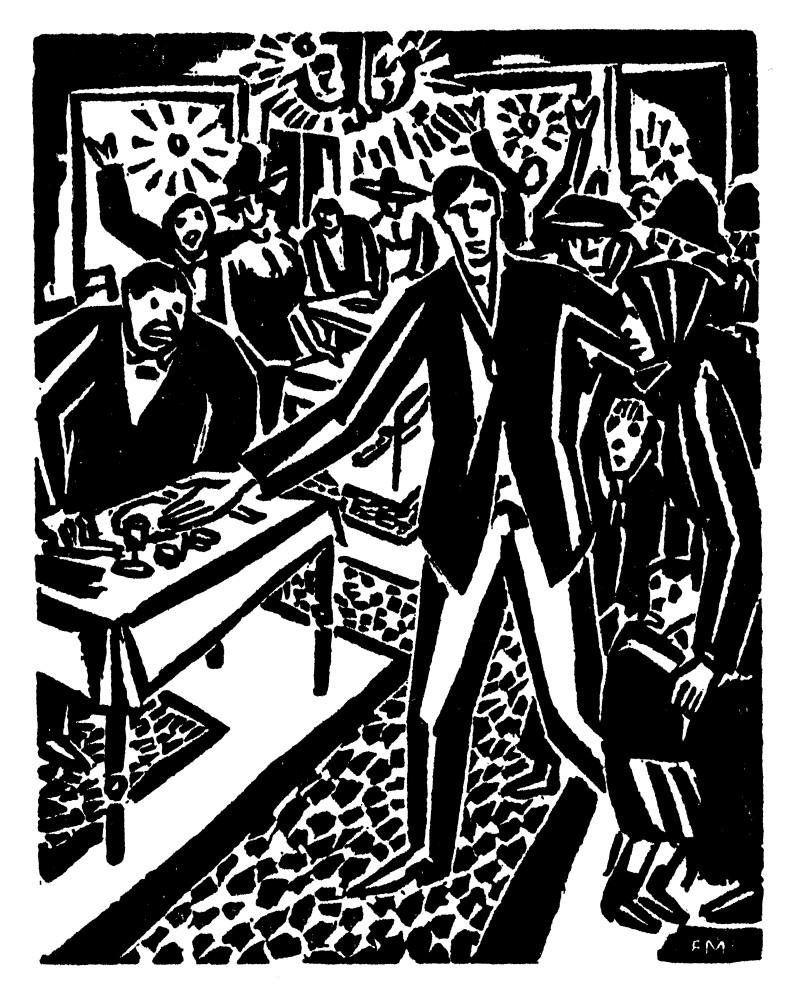

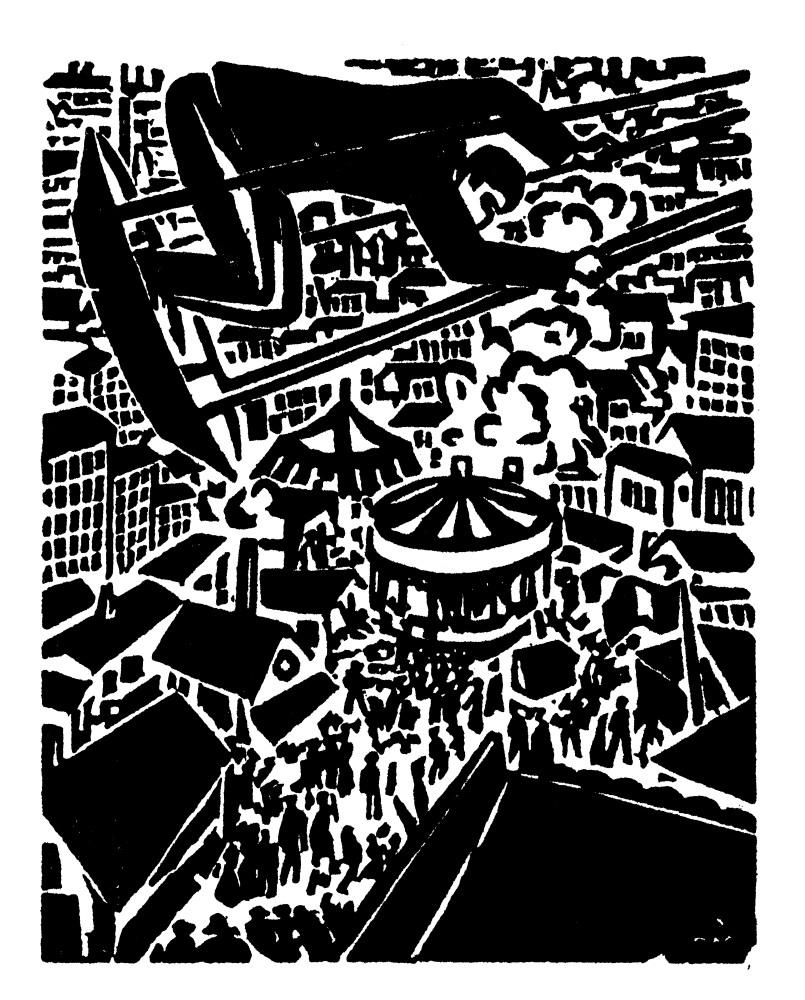

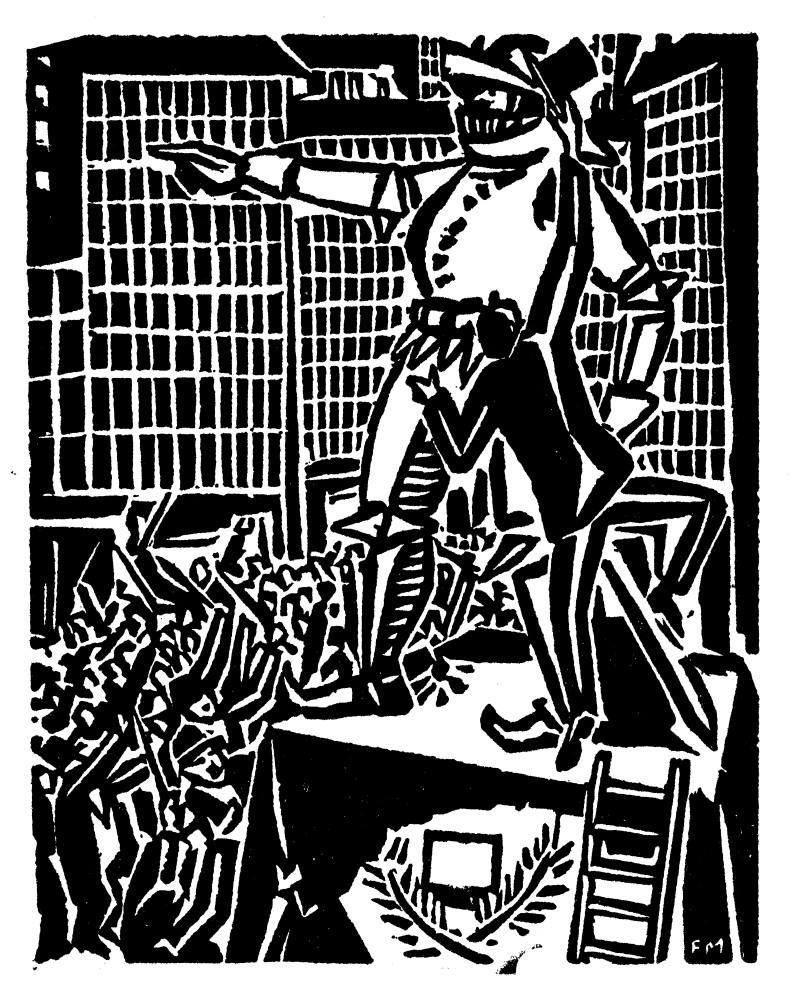

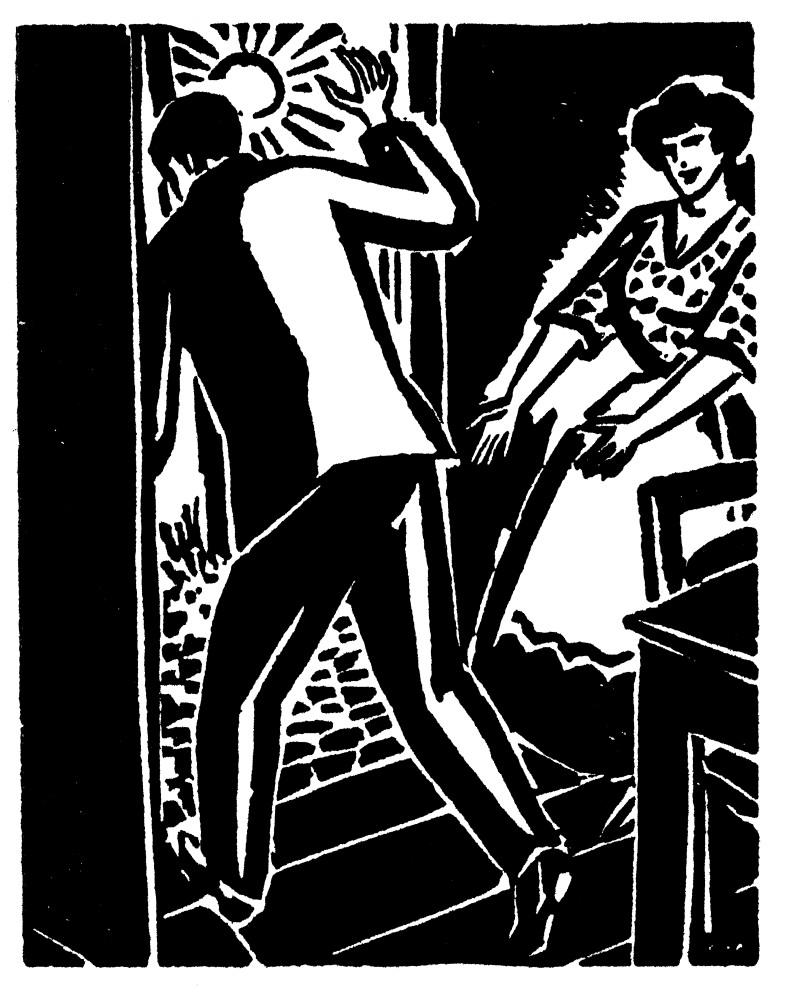

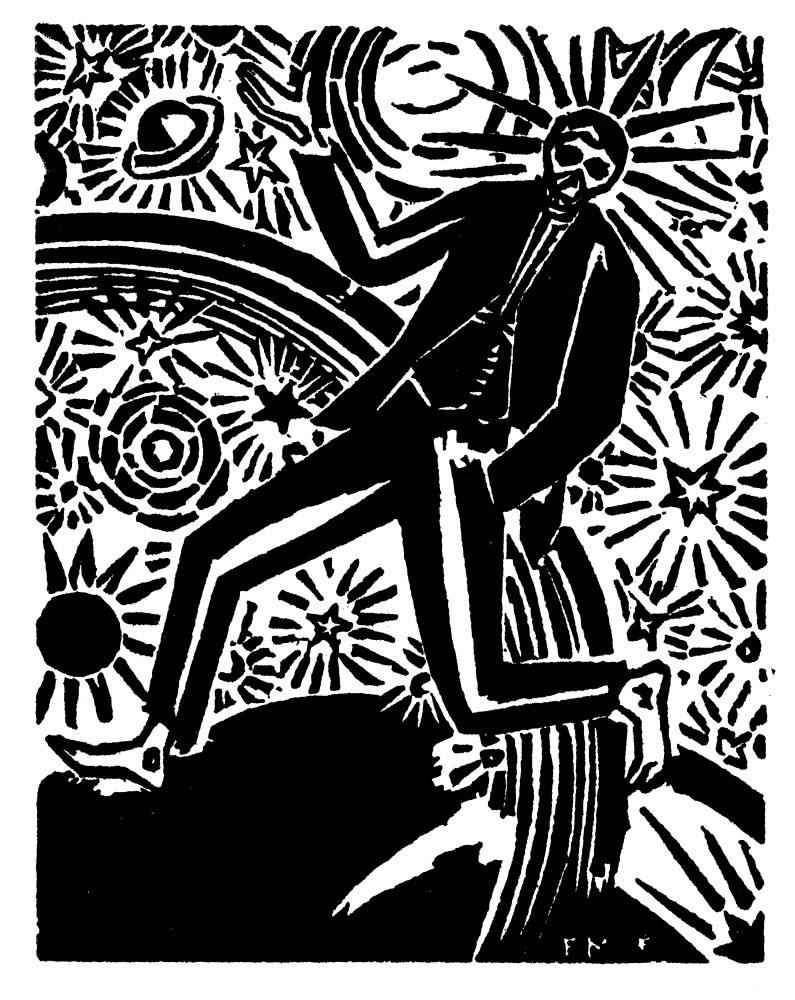

This was the first step up out of the abyss toward a new life. Henceforward, the spirit had heard the voices of the “gai scavoir” of freedom. Life is seen as a show, a great tragico-comedy, where the soul plays its part, but even while participating in the action of the play, frees itself, as if with a flap of its wings, and looks down upon life from a height as it were, laughing, somewhat pitifully, at its own efforts, at its joys, even at its own sufferings. “My Book of Hours” is the expression of this triumphant liberty.

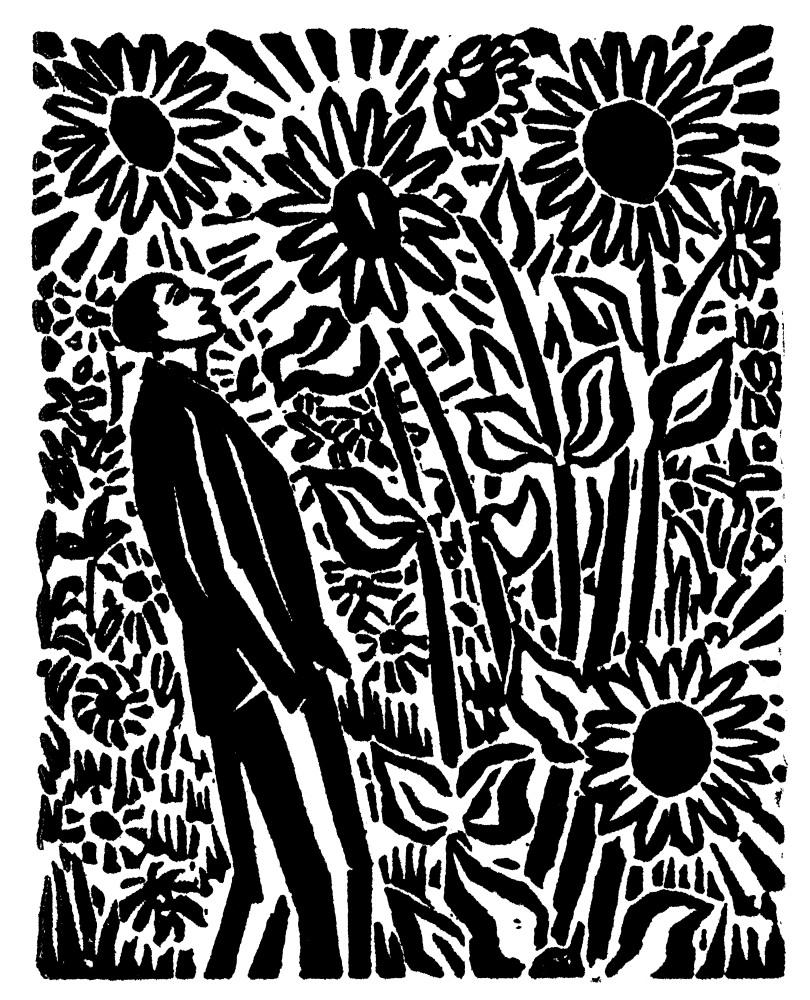

It is even more winged, more enraptured in the books which follow, such as “The Sun,” in which the liberated imagination is not content with looking merely at life, but must needs have the dream, too.

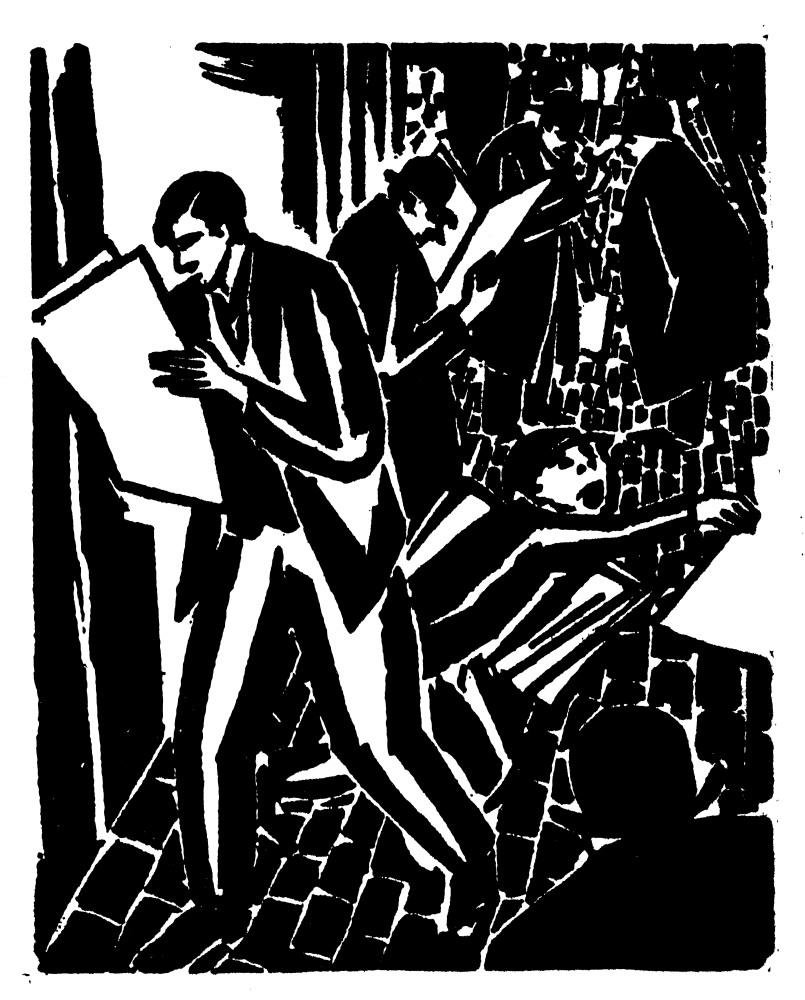

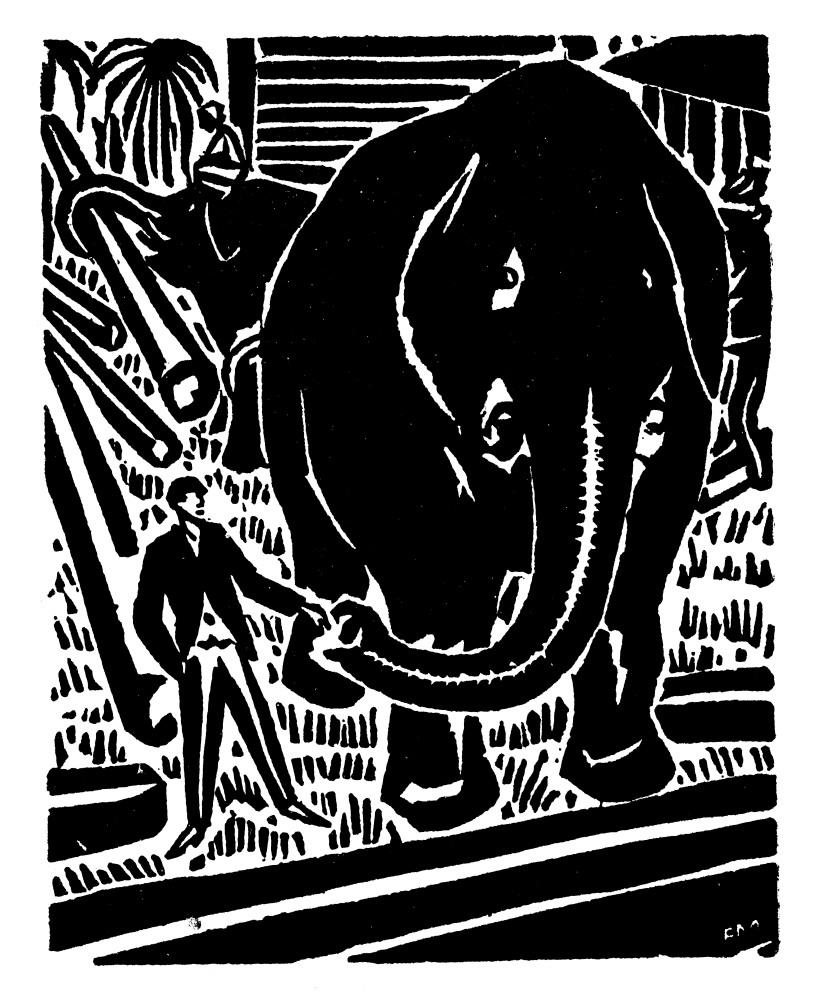

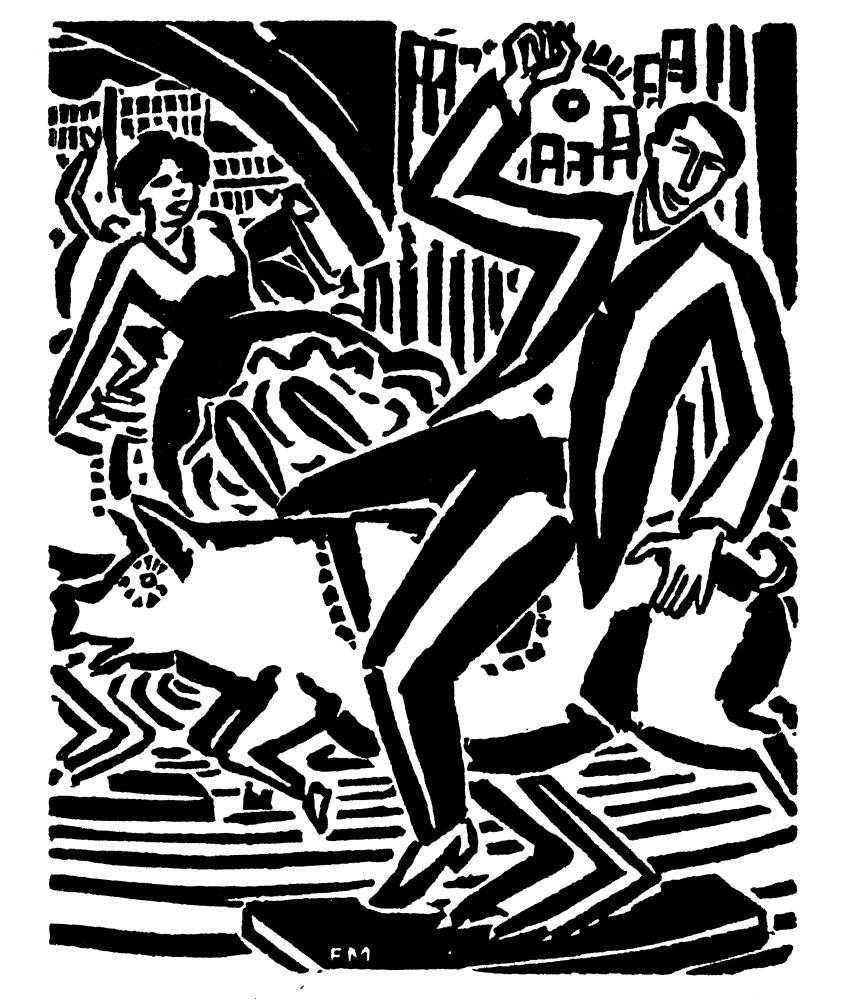

I will not attempt to pass judgment on an art which is still in the state of a metal undergoing fusion in the melting-pot. There are so many conflicting forces in Masereel, such varied passions, fantasies and ideals! His style is constantly undergoing change: at first realistic (as in the fifteen poems of Verhaeren), then heroically imaginary in “Rise, Ye Dead!” primitive in concept to a point of classical restraint in “The Sufferings of a Man.” and his present style, short and forceful, and so concise as to be sometimes overwhelming.

I will point out only the two chief aspects of his genius: On the one hand, he is the great illustrator, adapting himself with impassioned responsiveness to the thought of the poetic works which he transforms by his art. To indicate only three: “L’Hotel-Dieu,” by P. J. Jouve, where the interpretation is mainly realistic, enlivened by bitter irony; a laughing wanton abandon as in my “Liluli”; and “Other Men’s Blood," by René Arcos, illustrated in a heroic vein with symbolic compositions out of which arises, like the song of a flute, the admirable elegy, “To the Memory of a Friend,” full of musical imagery, genuine and poignant.

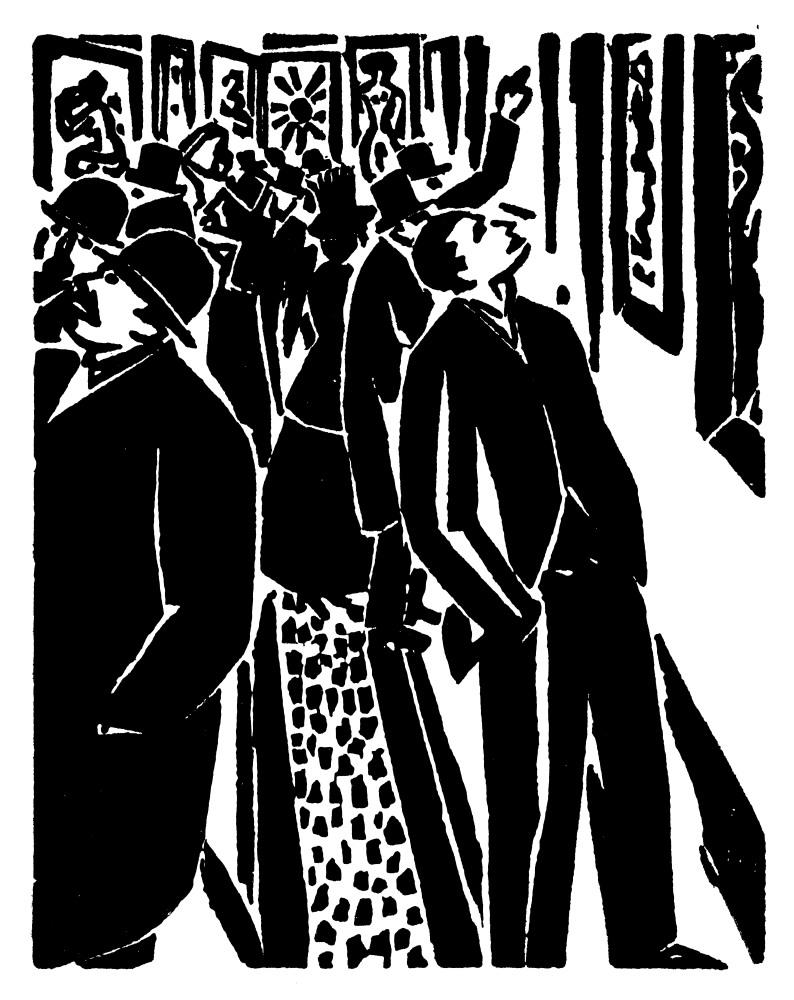

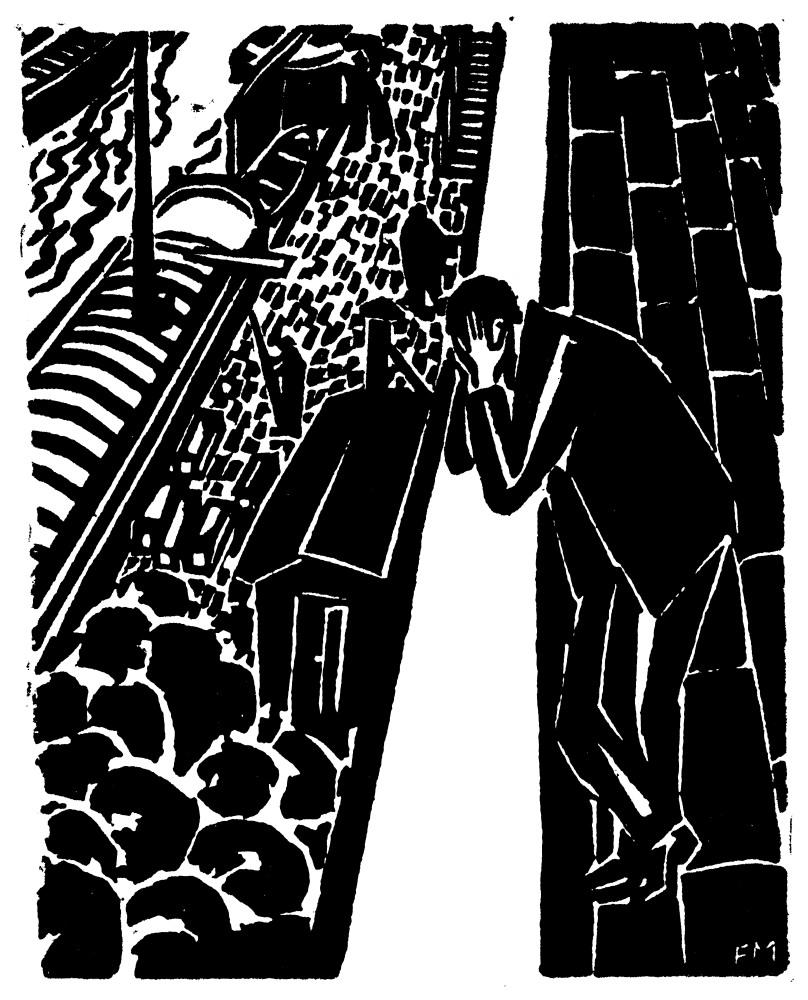

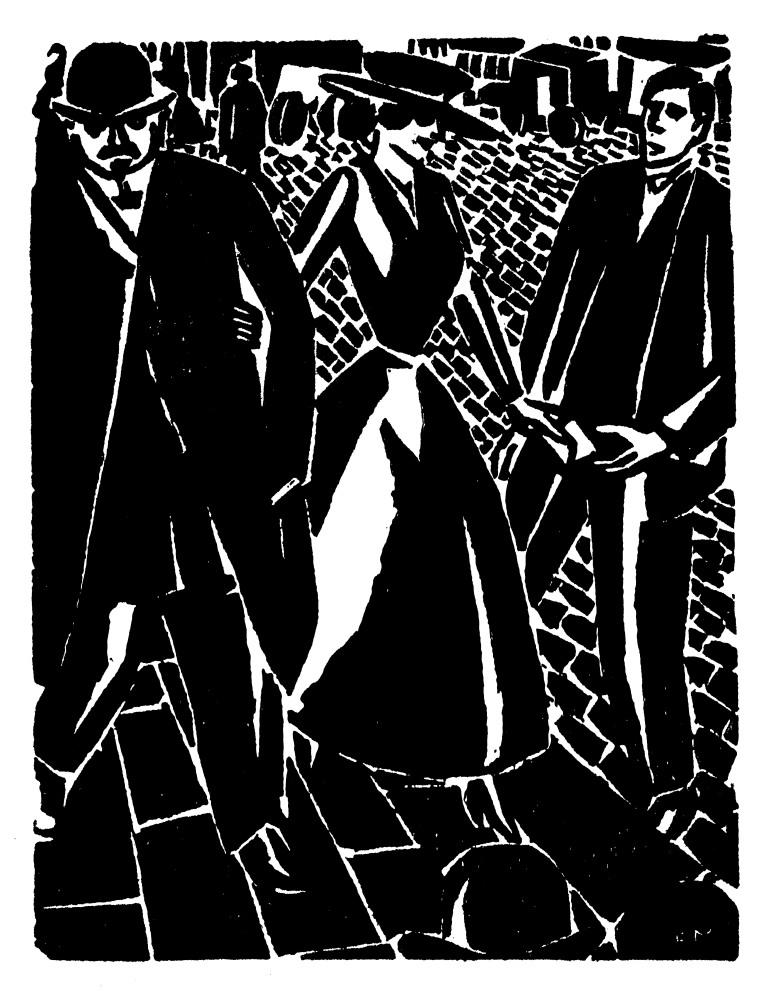

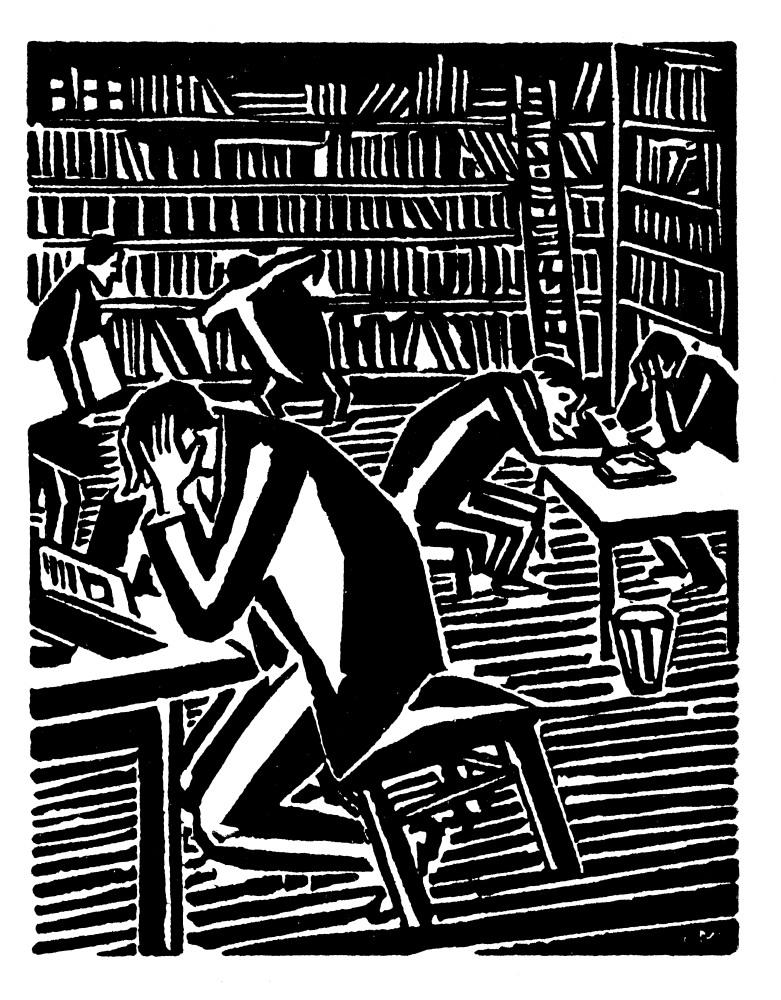

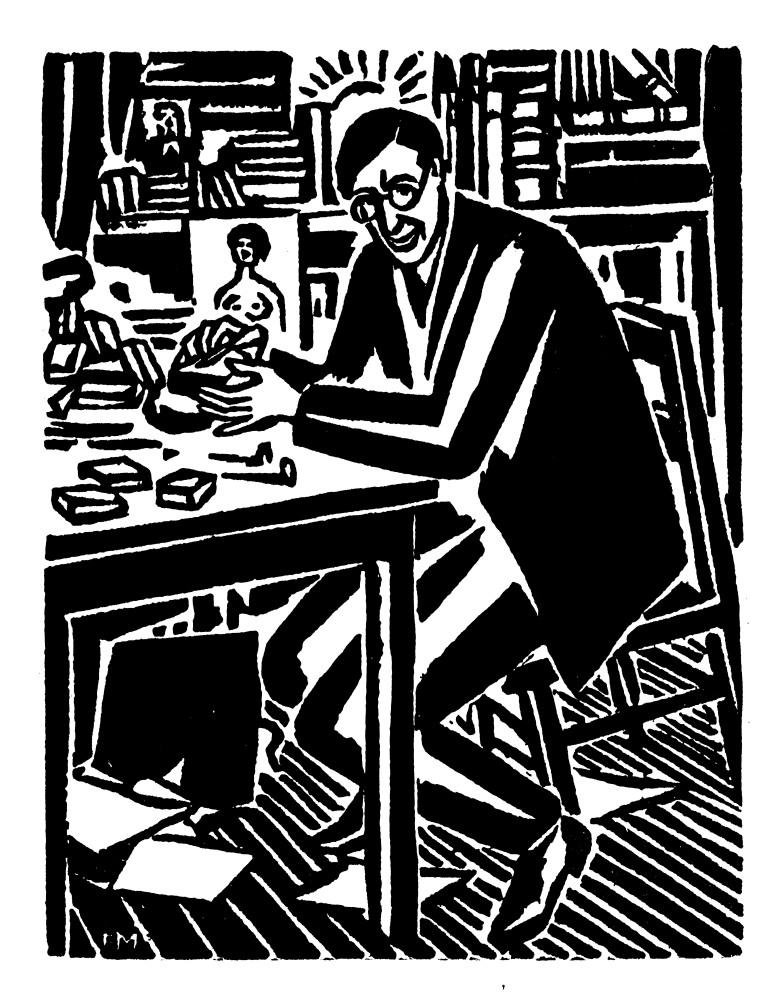

On the other hand, there are those illustrations which, rather than being exact interpretations, are like happy musical variations on given themes. Masereel rises to personal creation, becoming suddenly a poet sufficient unto himself. He has produced a sort of philosophic and fantastic travesty poems in pictures, of which “My Book of Hours” is one of the most beautiful examples.

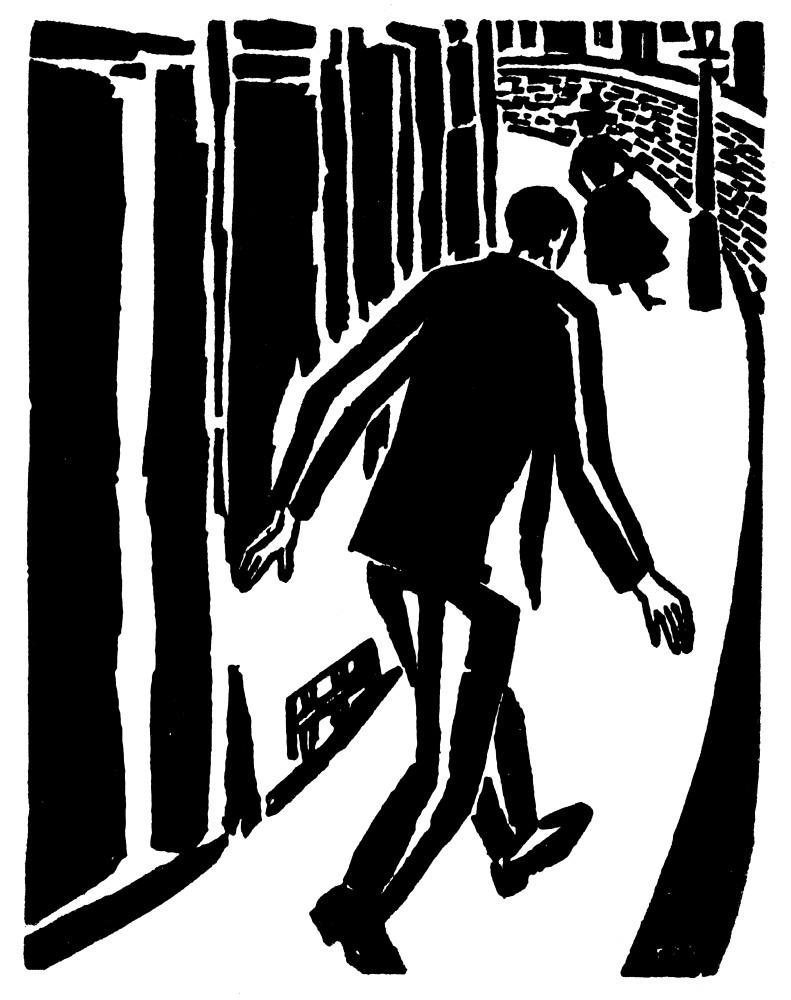

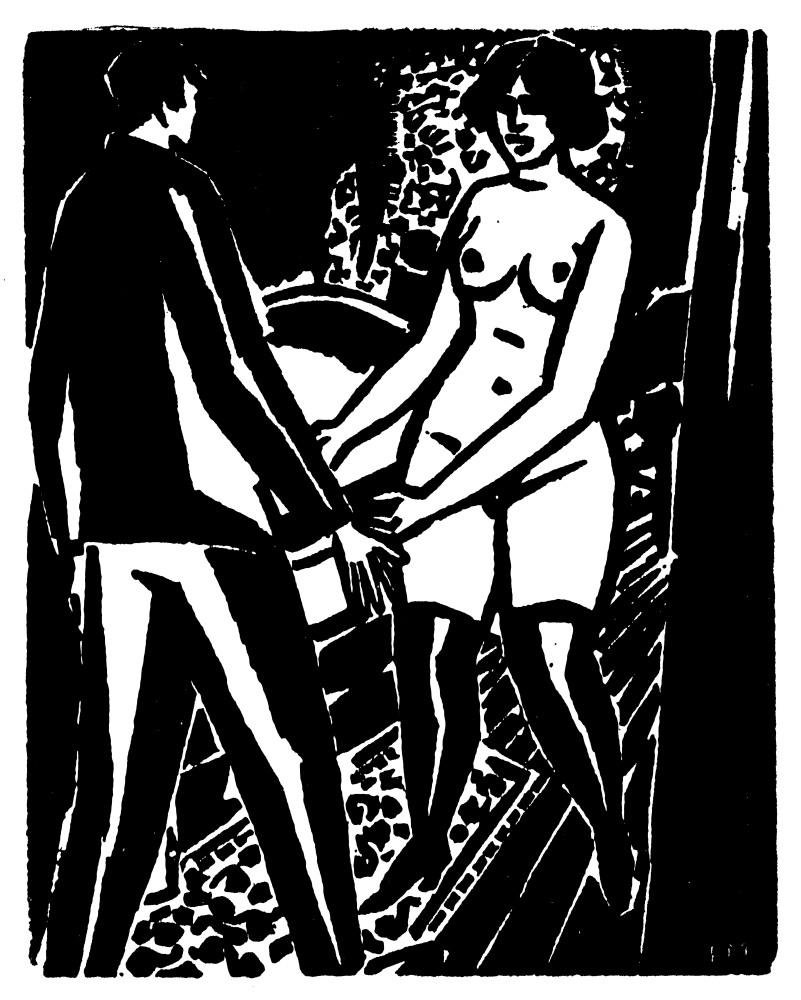

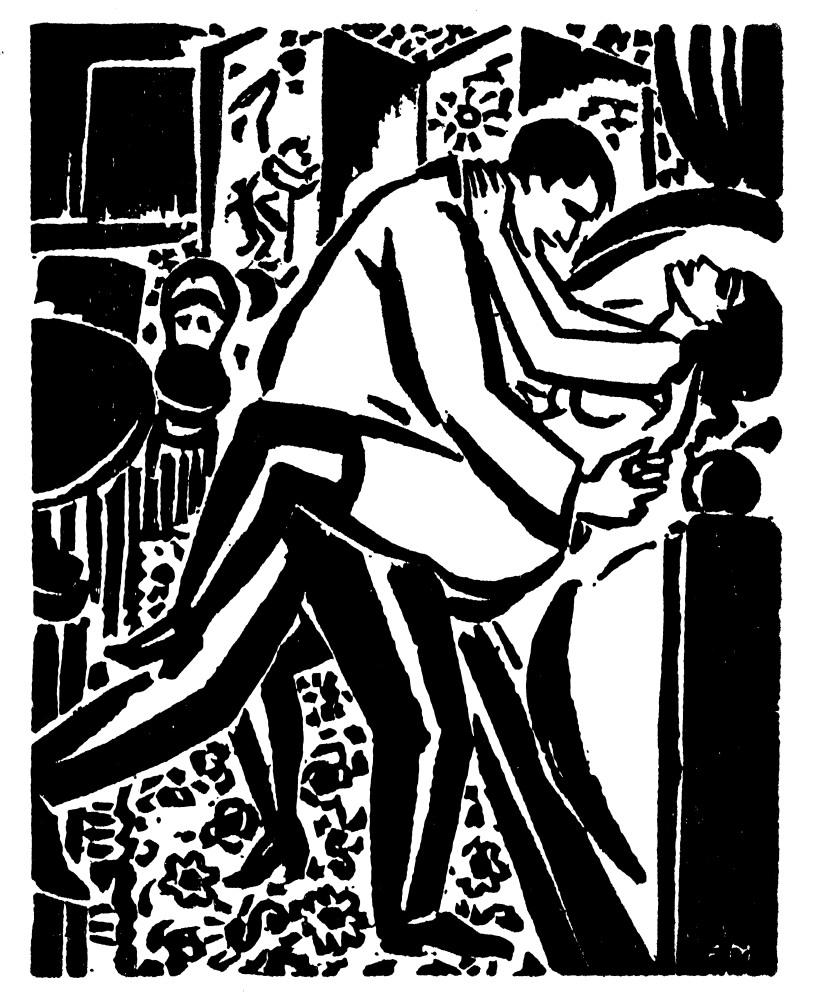

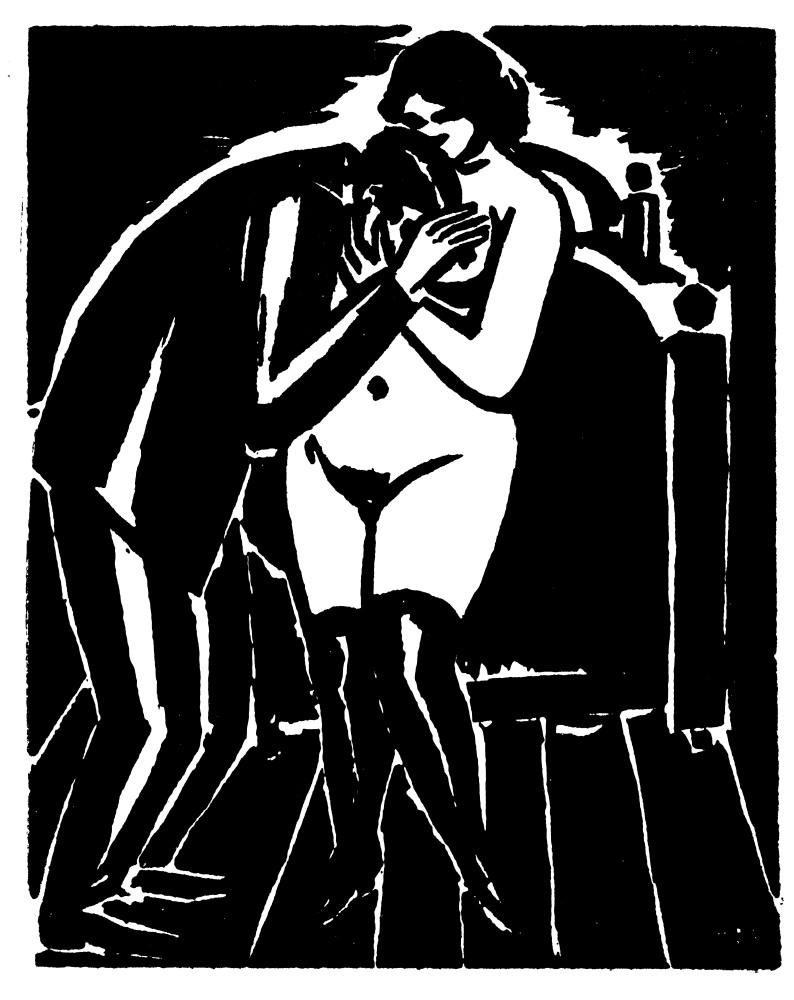

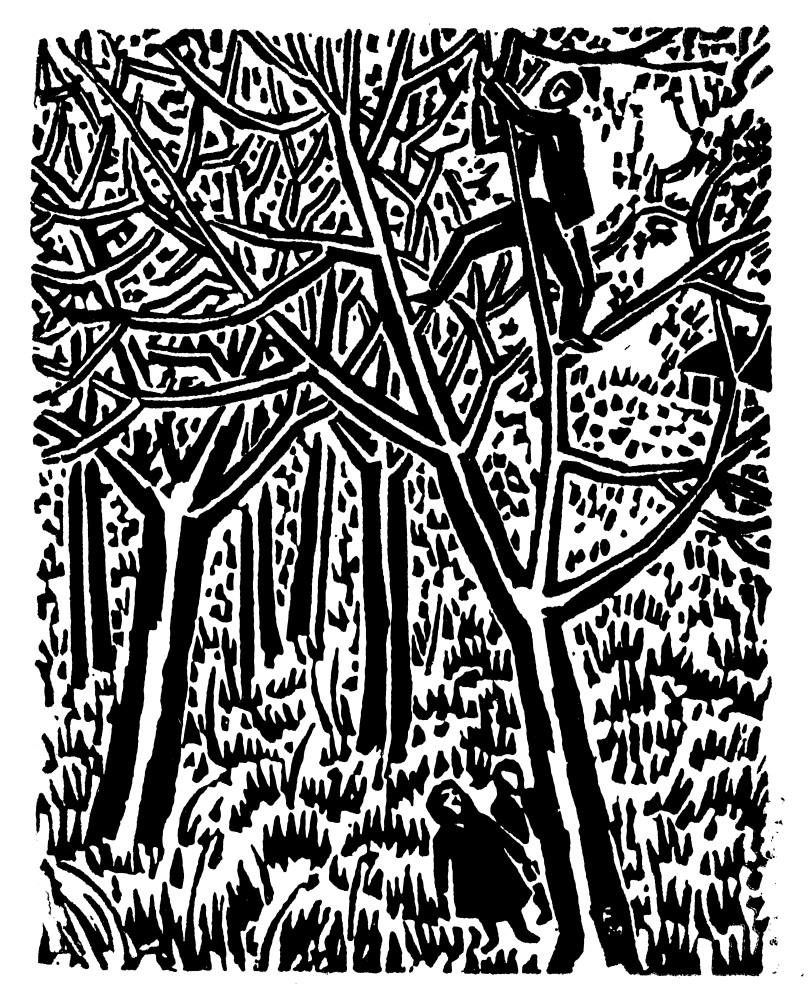

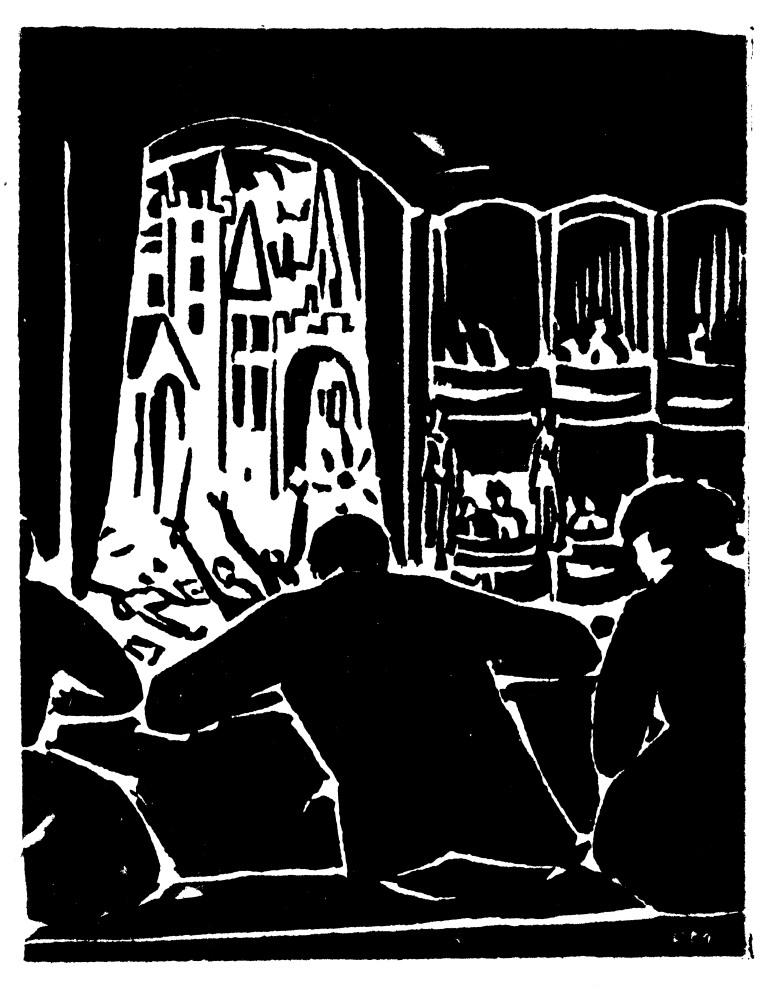

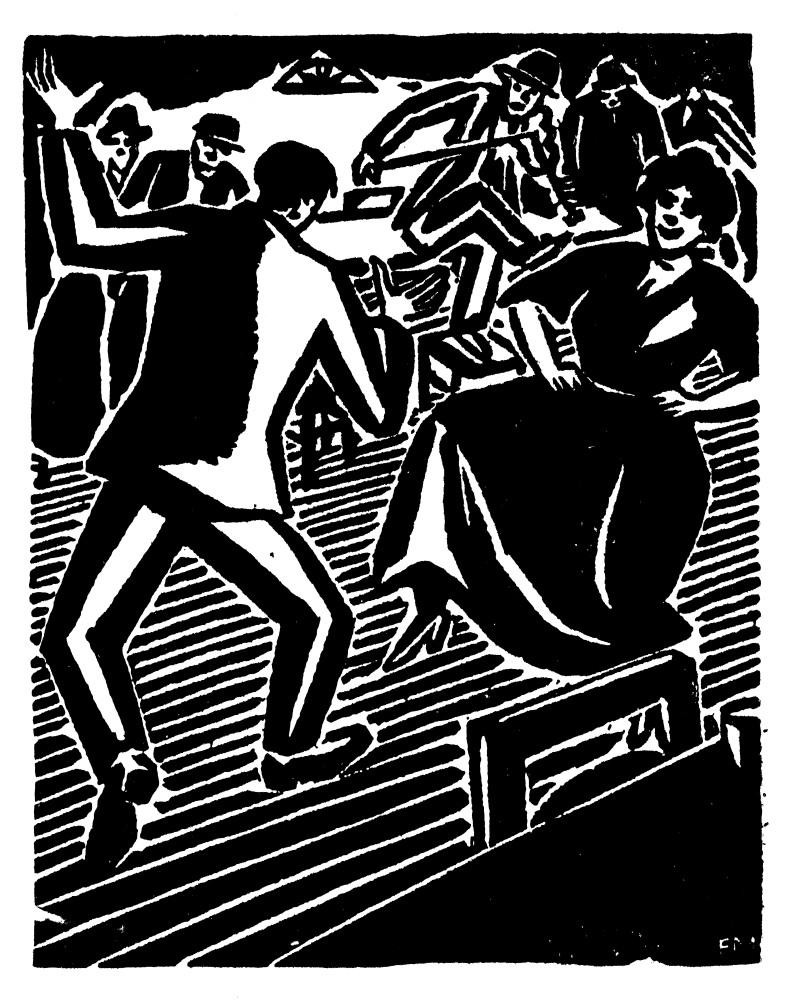

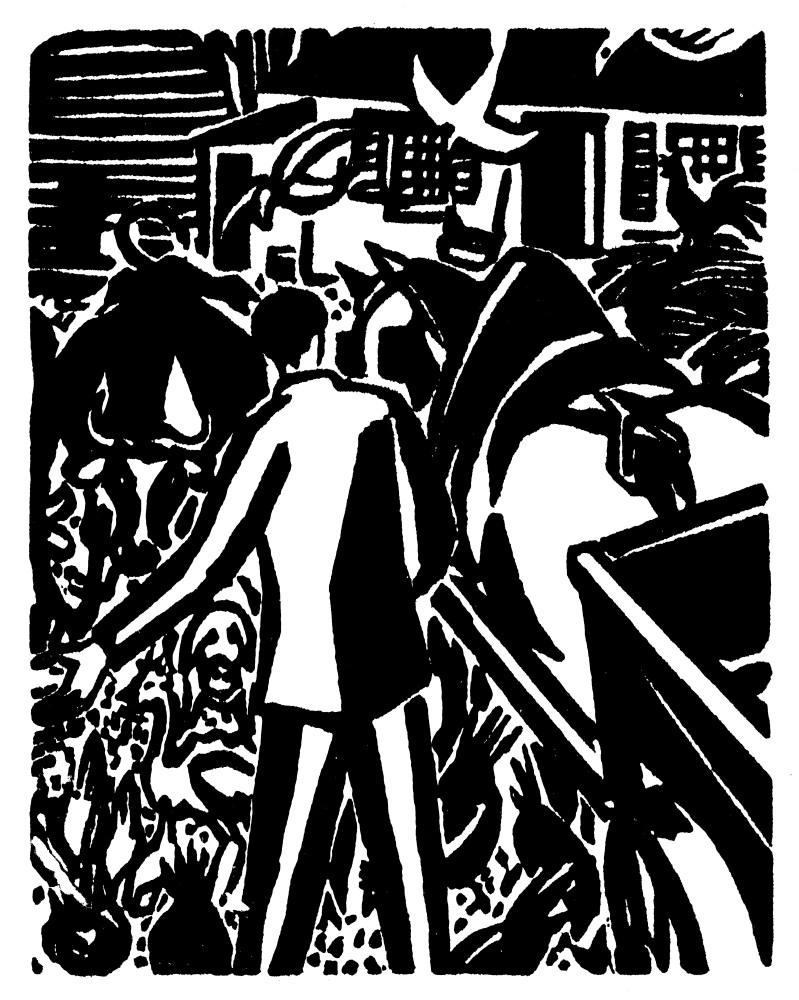

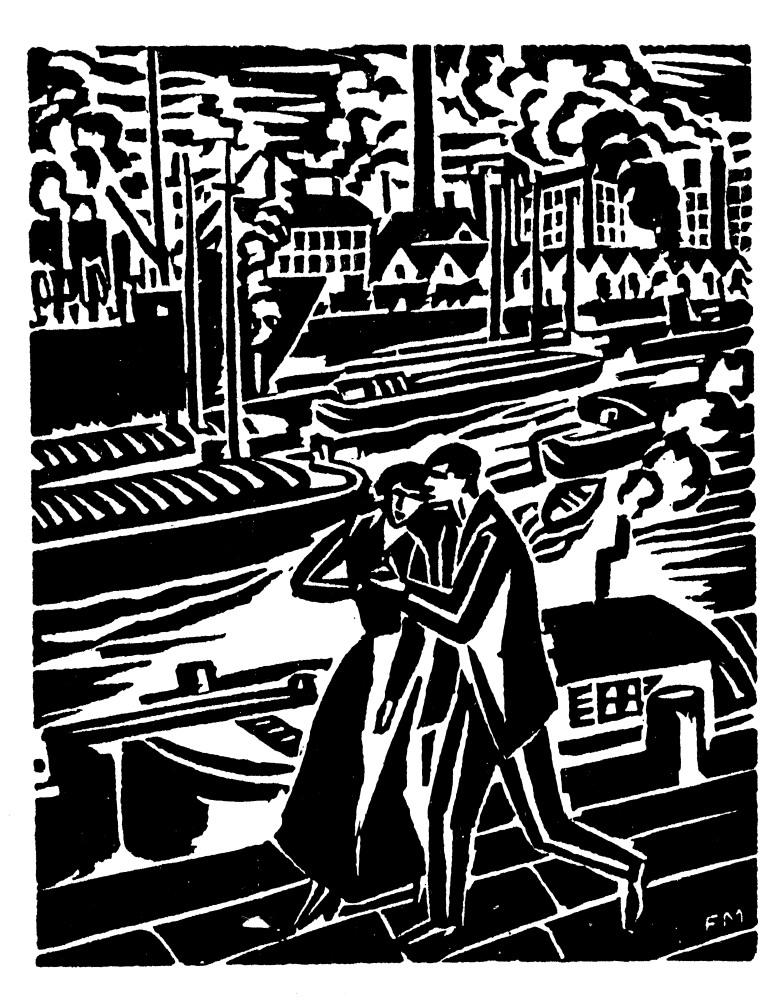

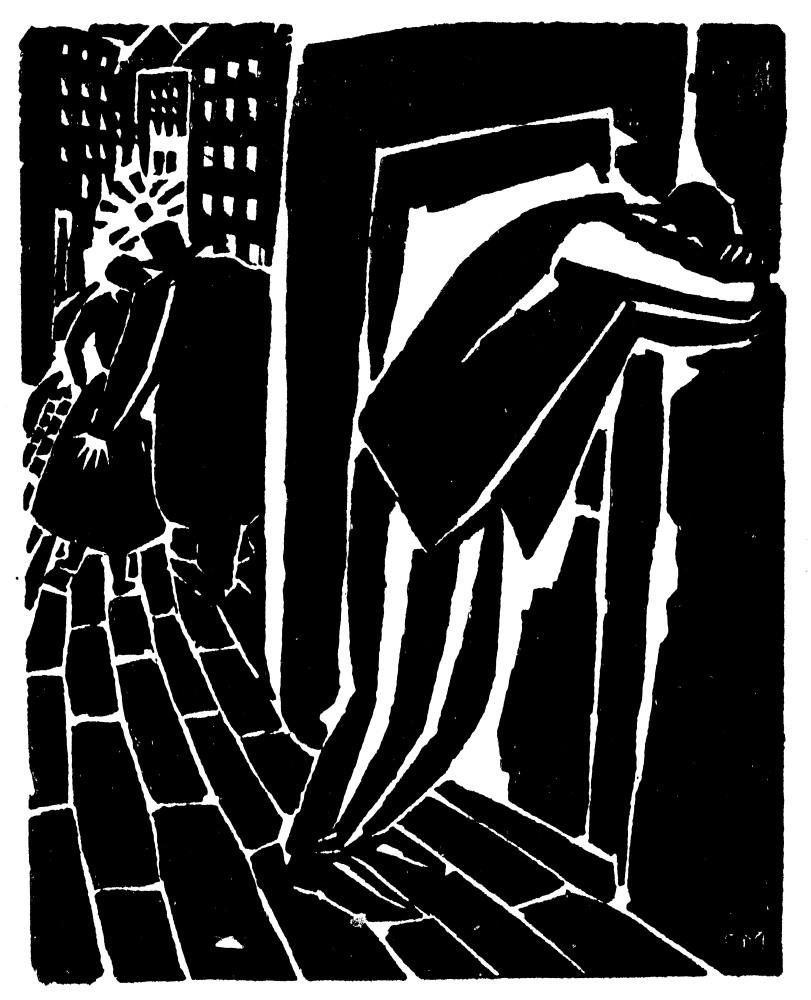

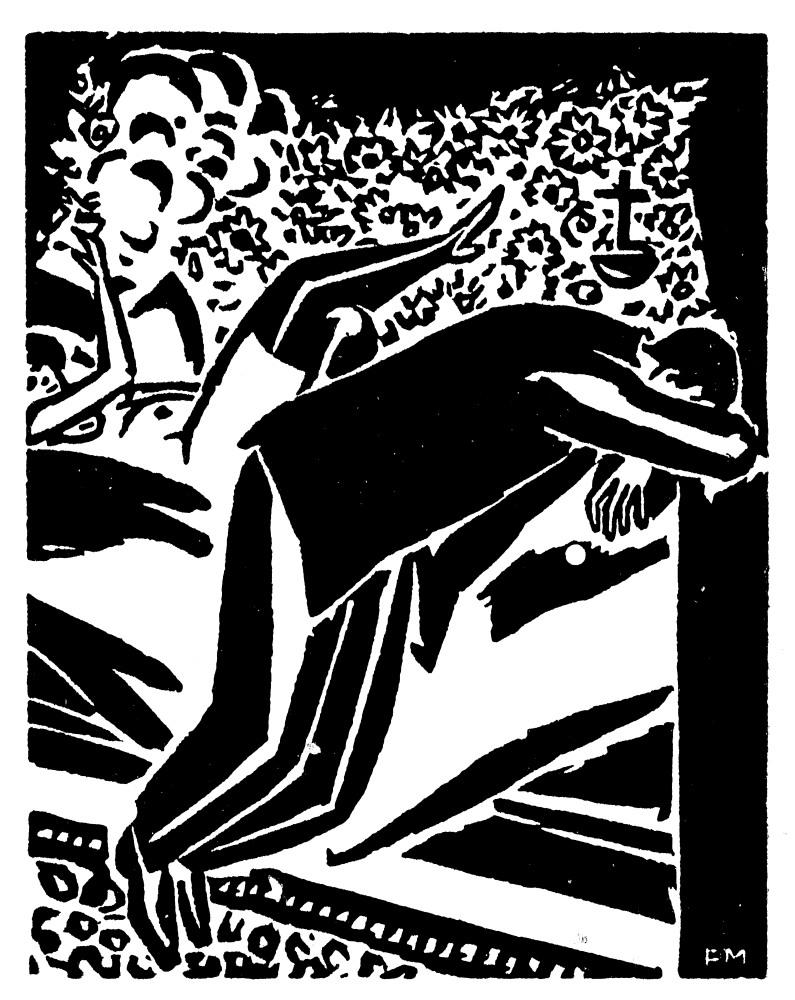

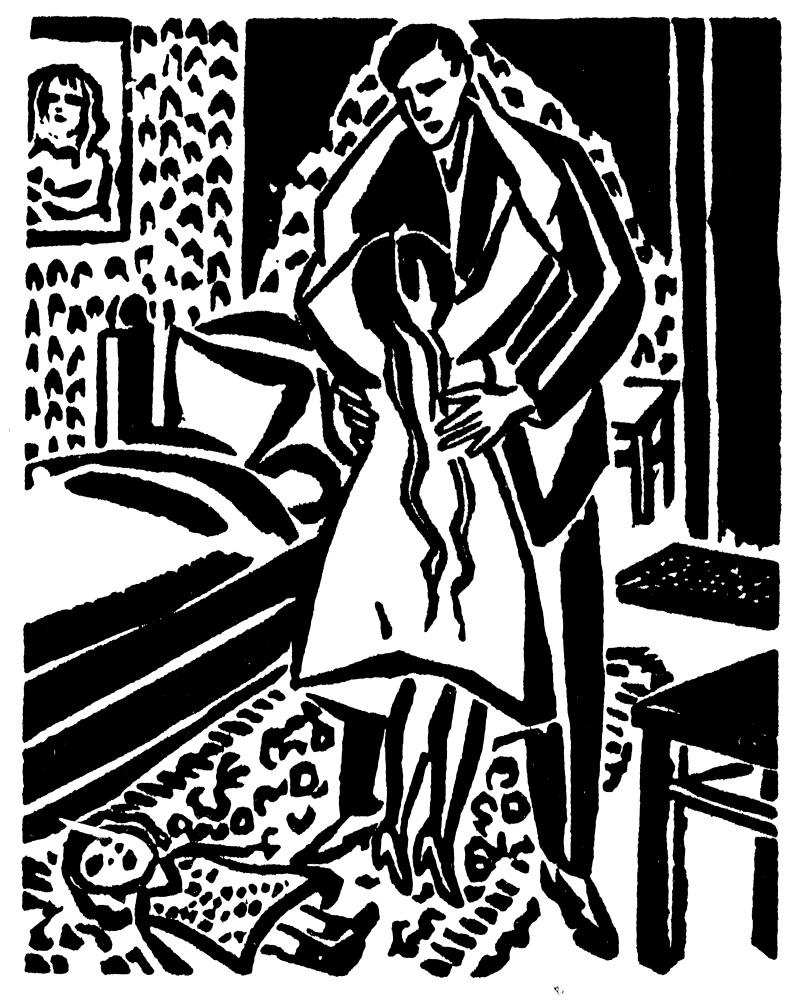

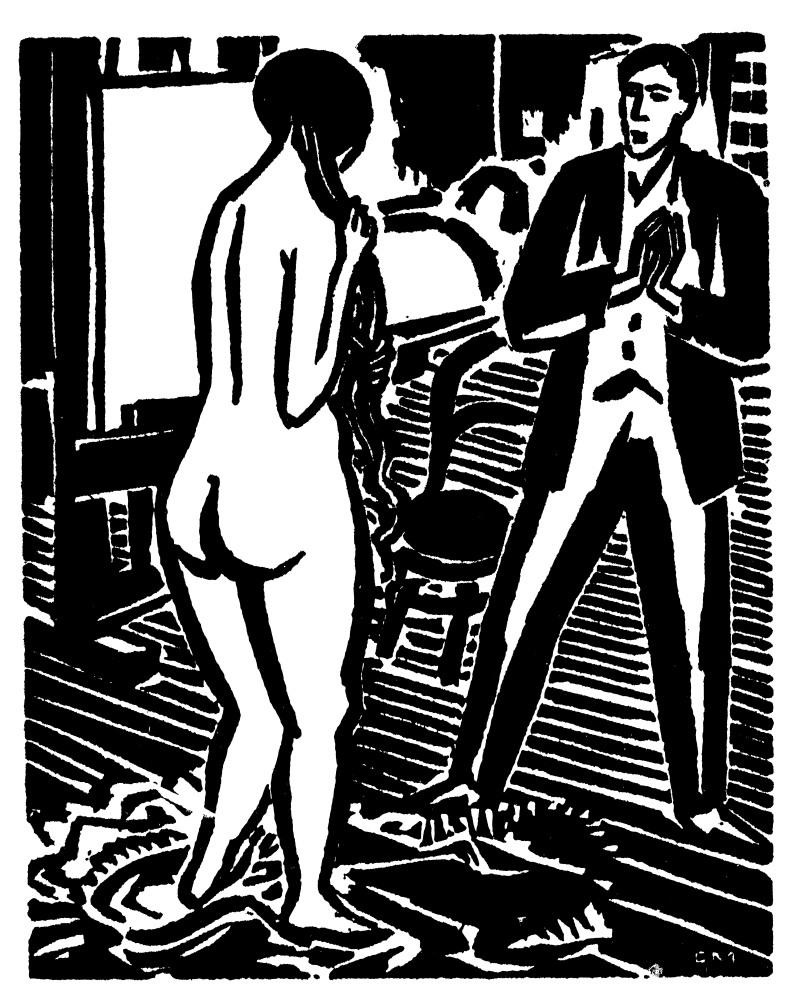

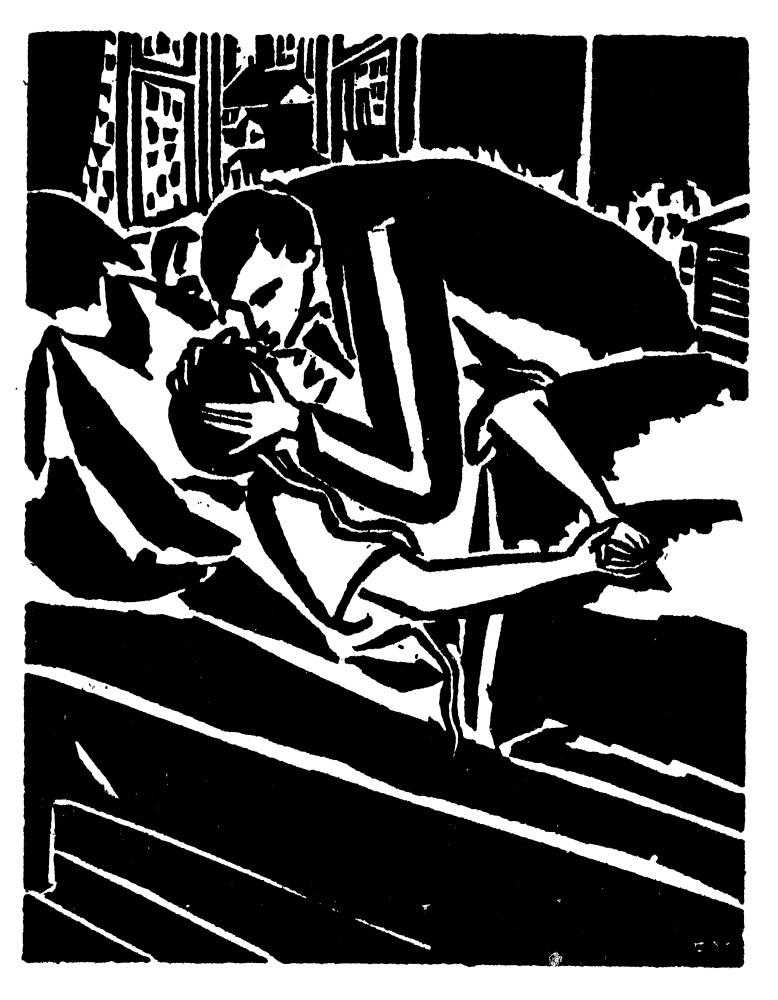

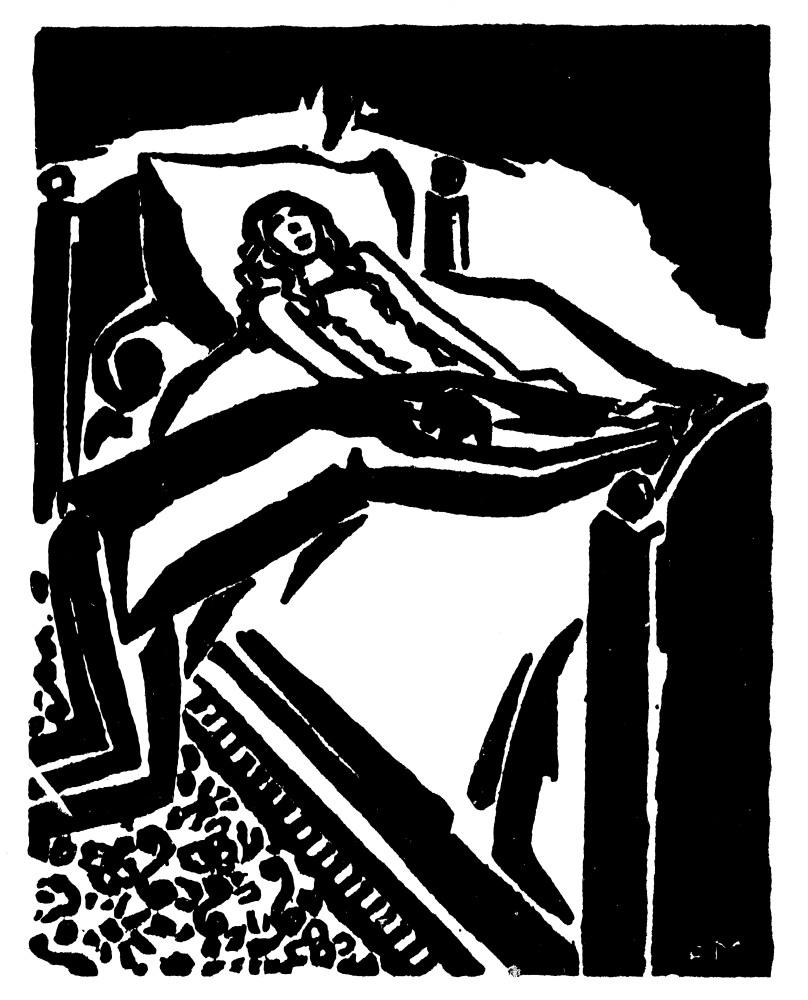

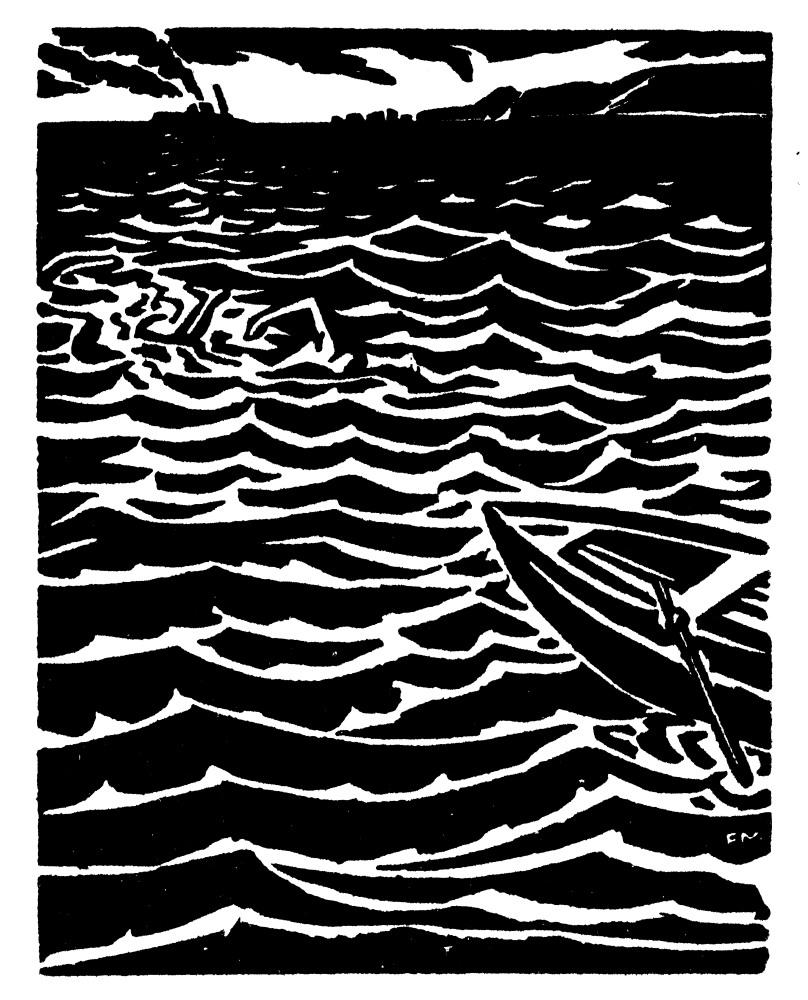

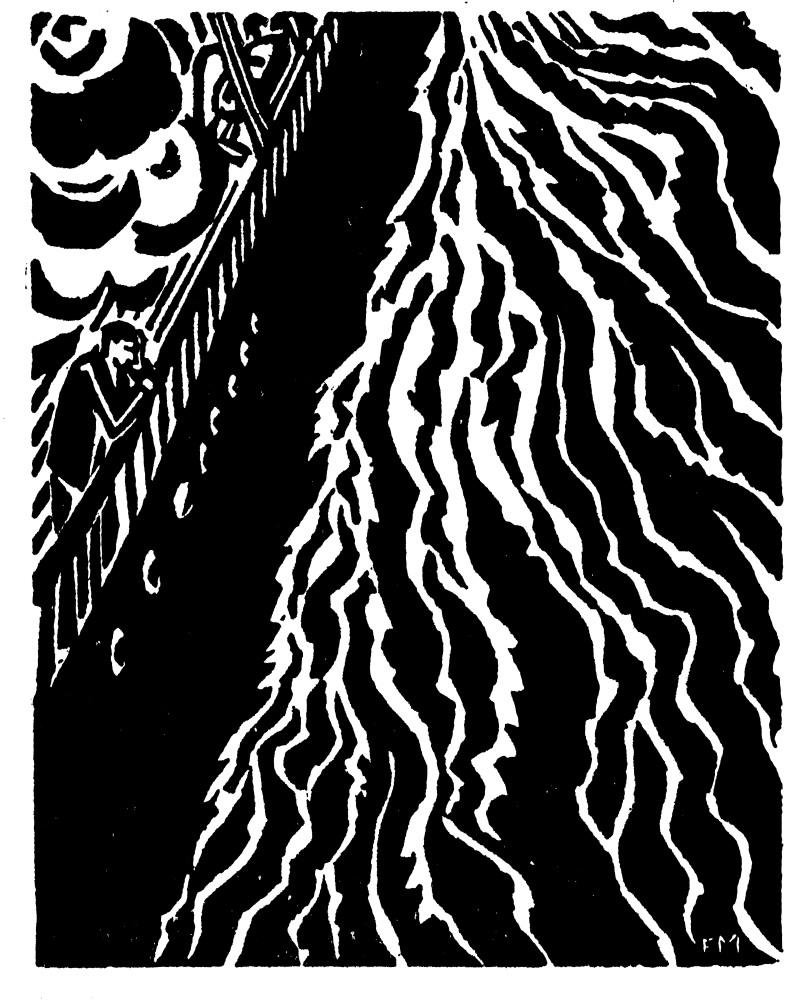

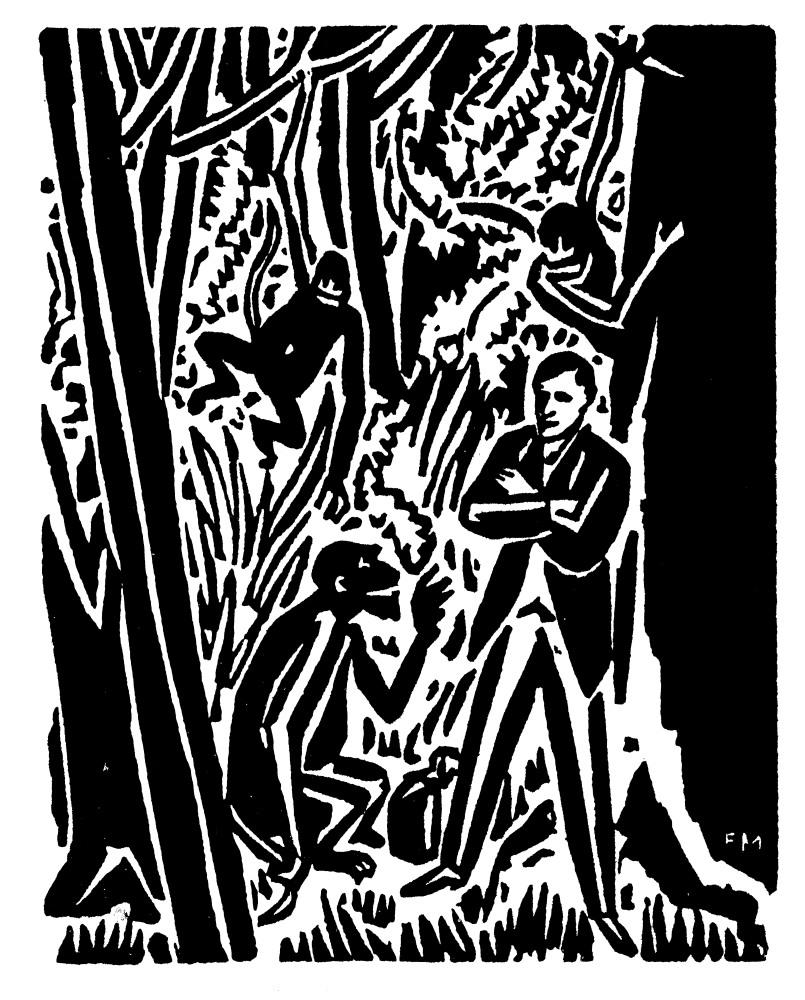

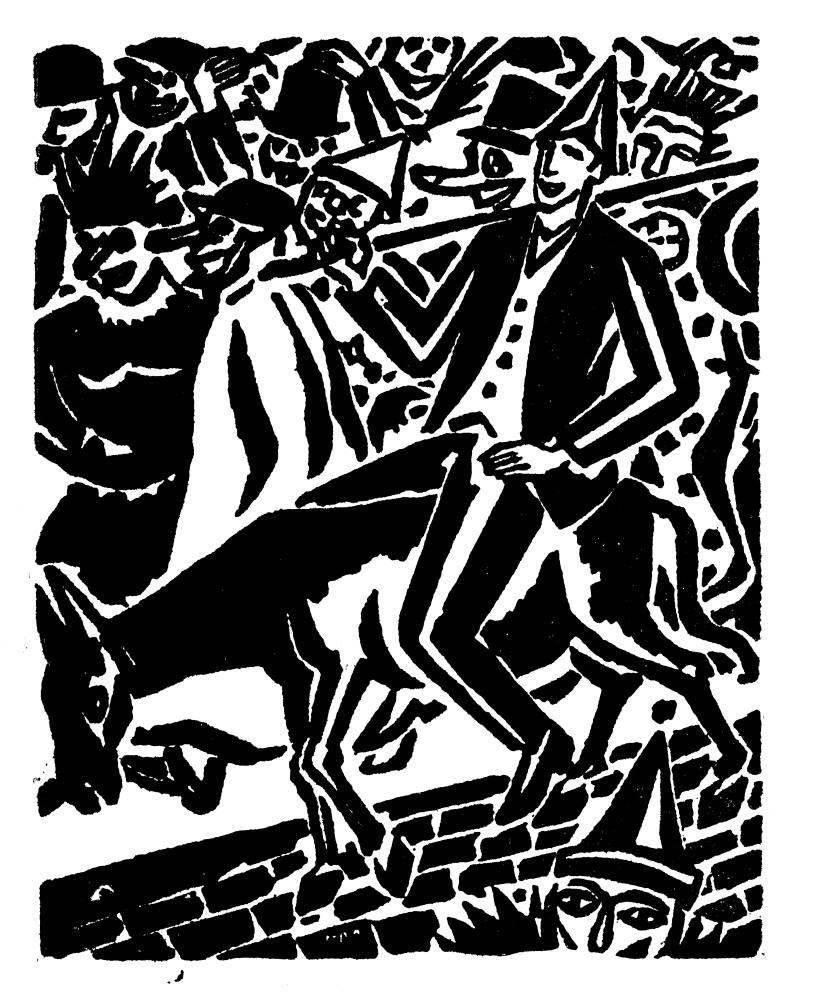

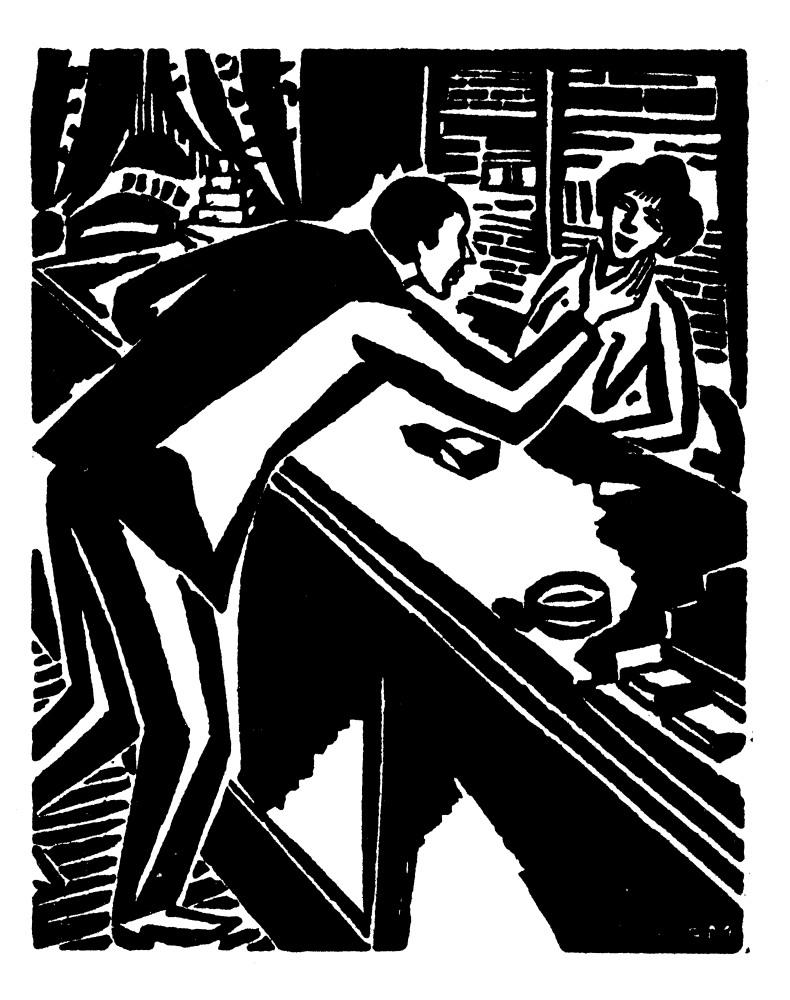

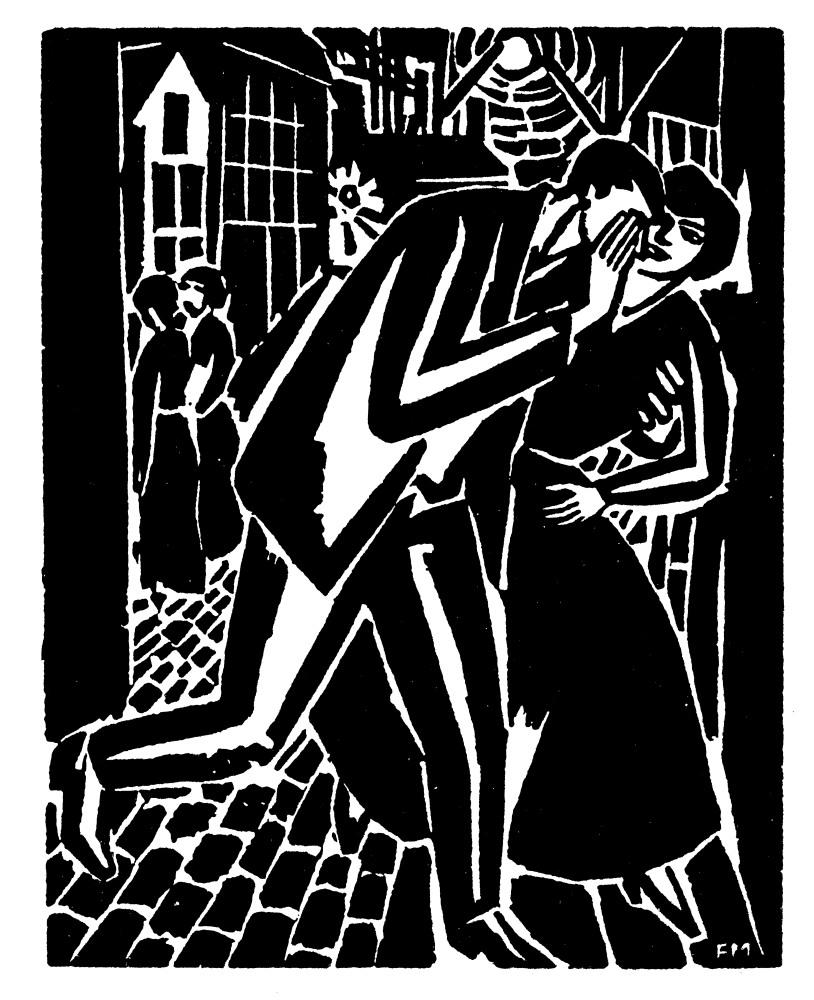

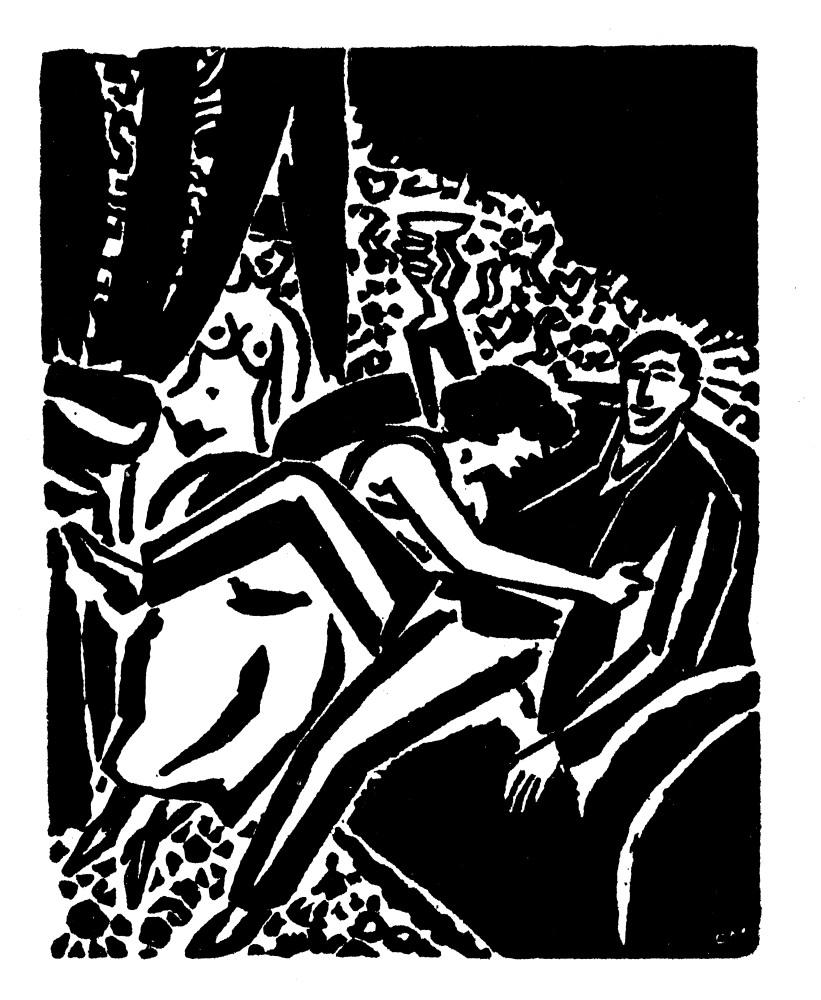

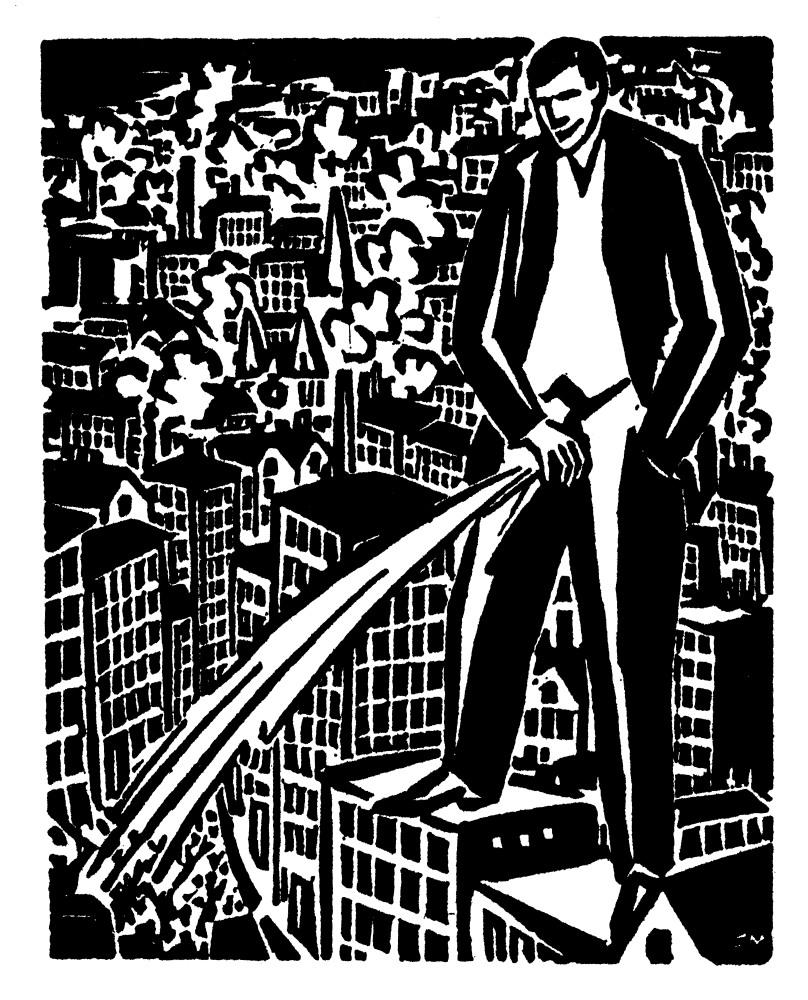

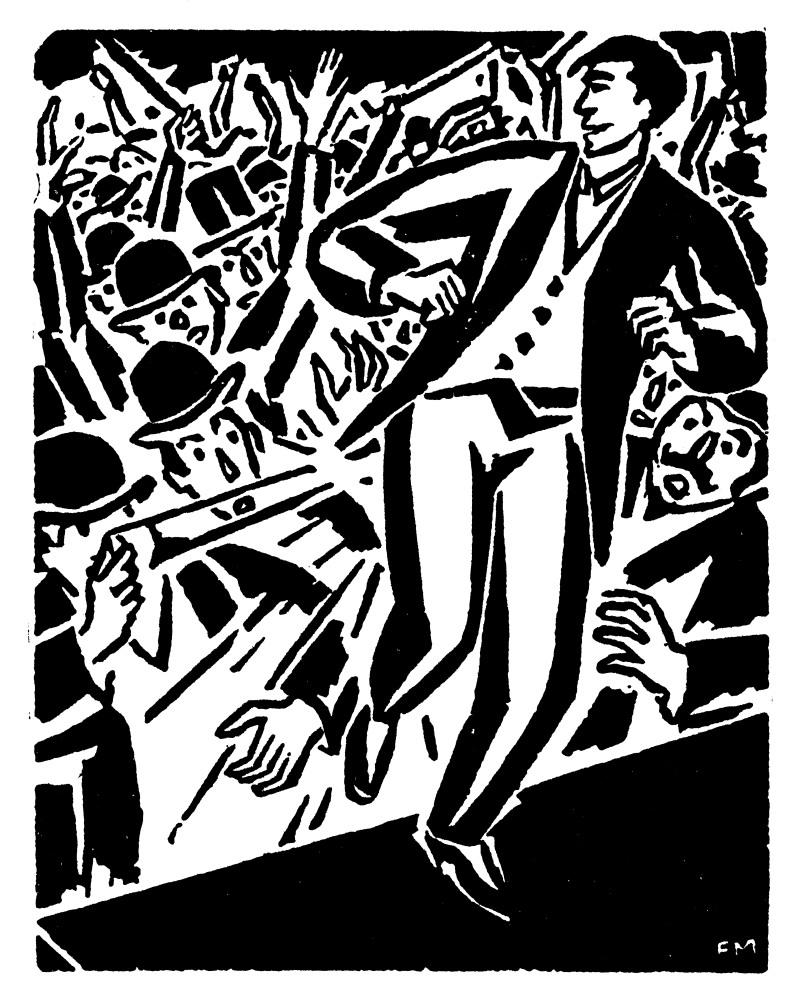

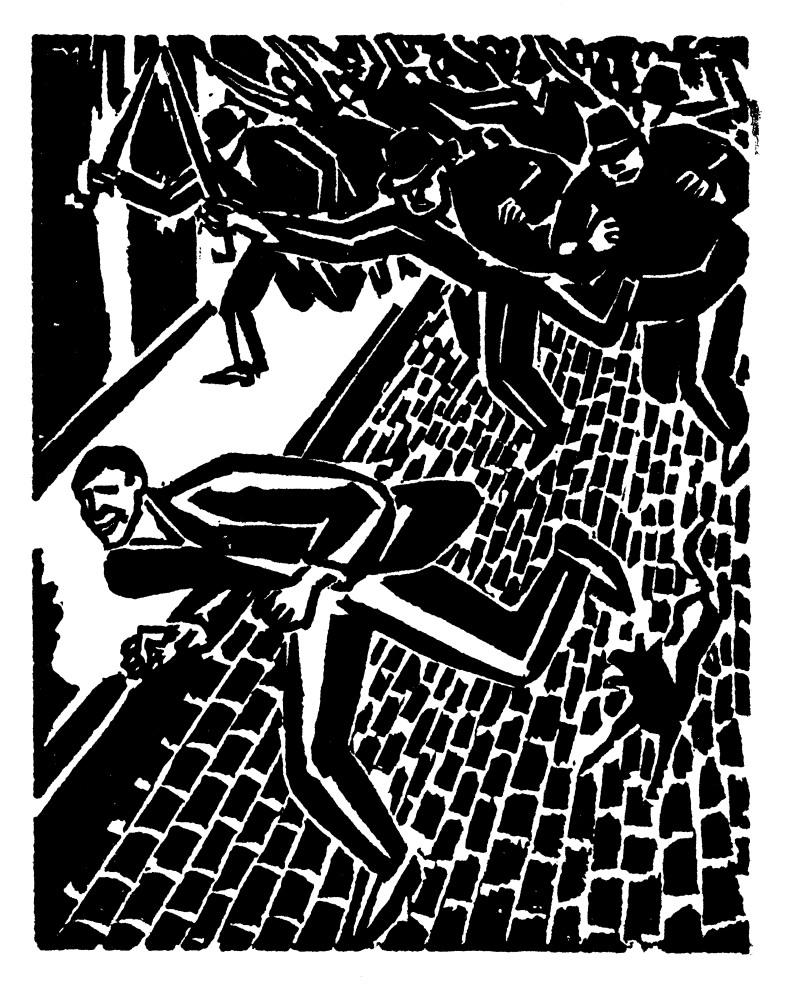

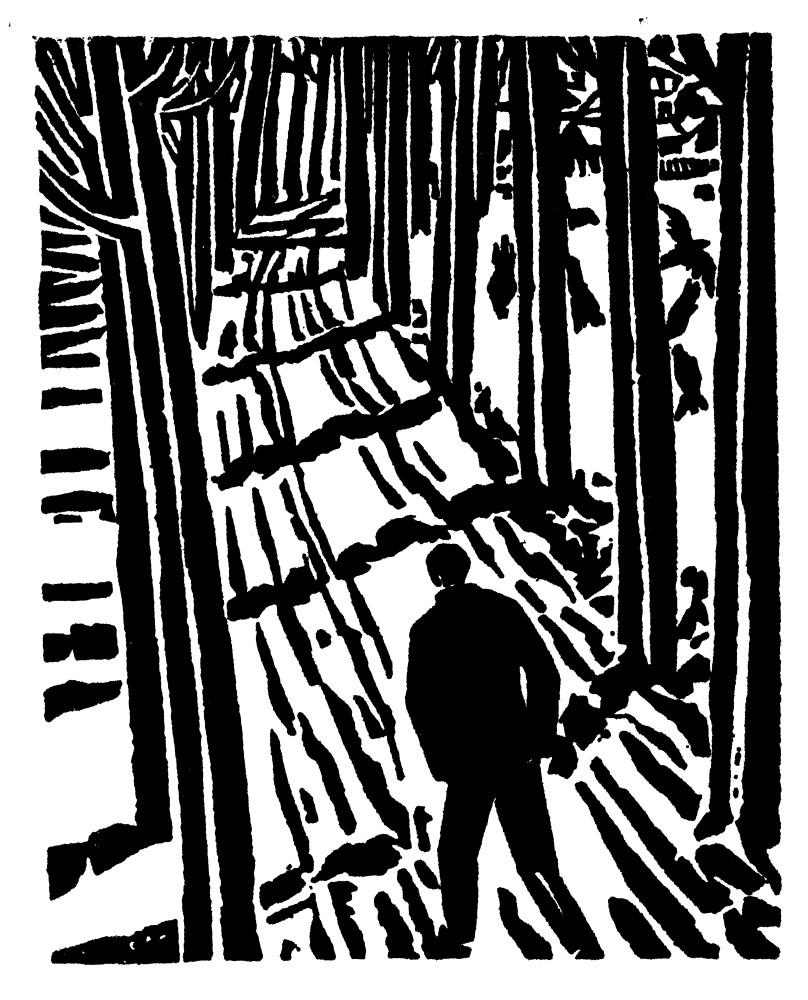

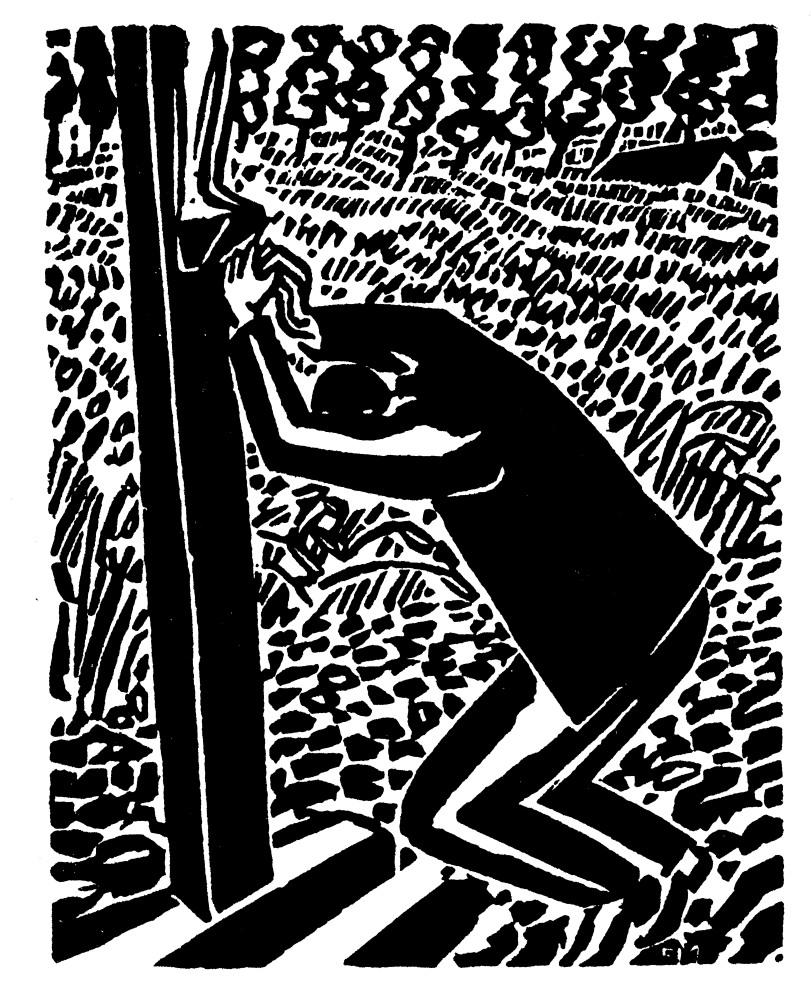

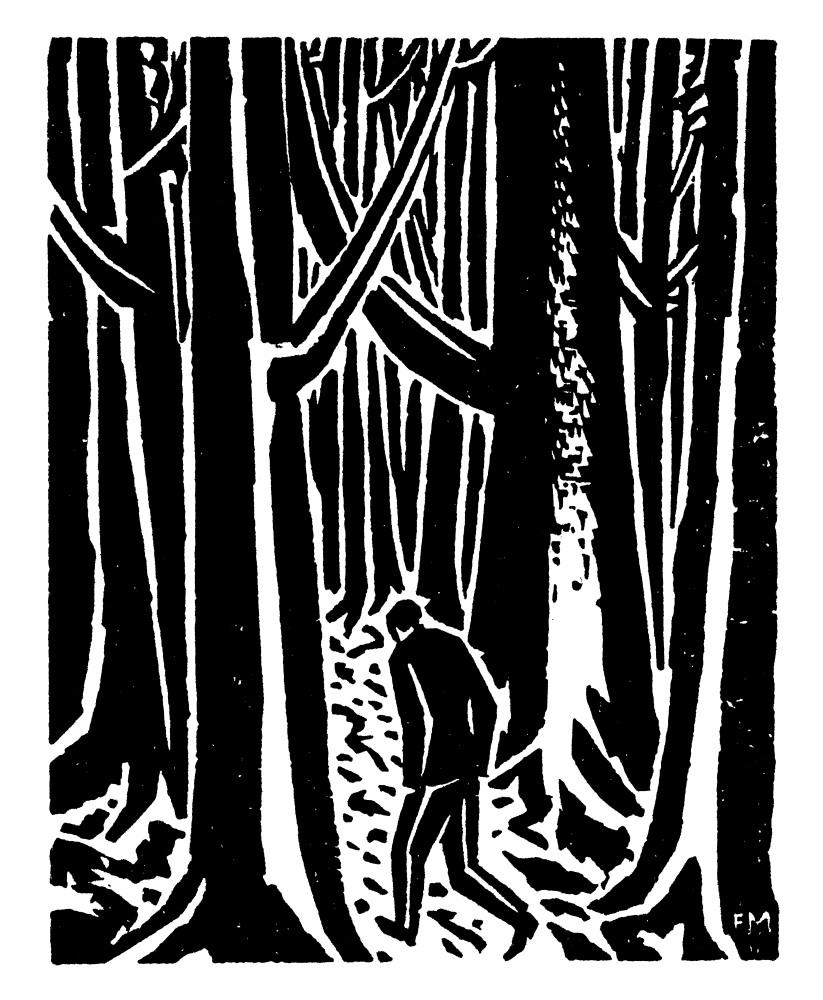

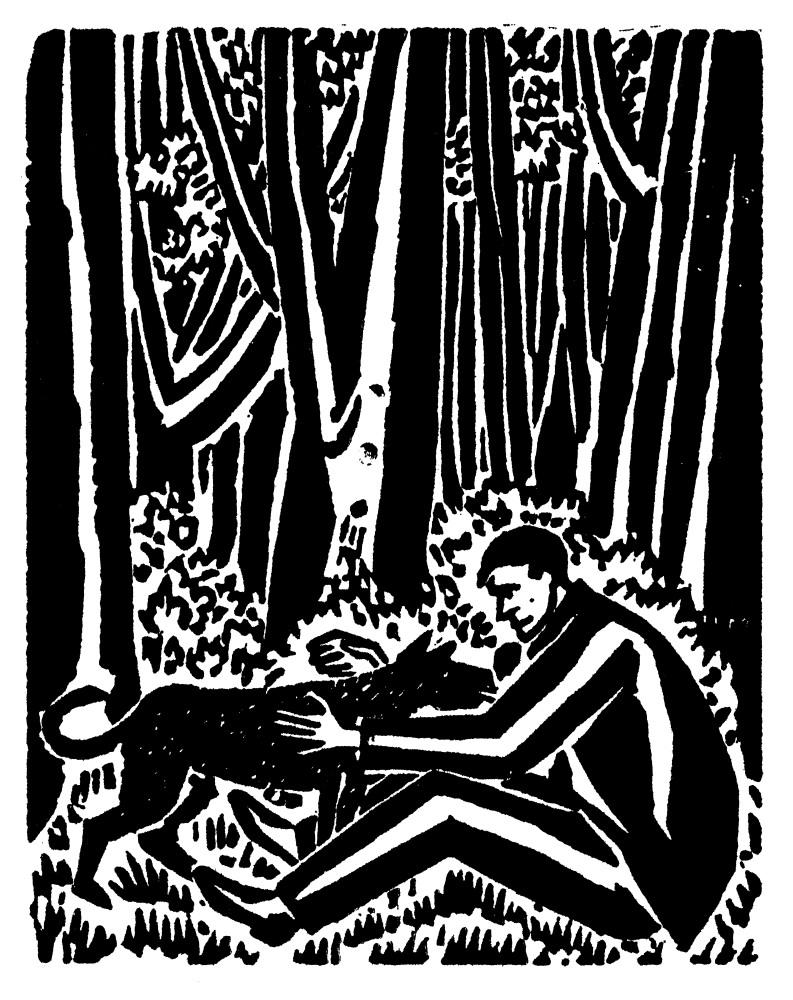

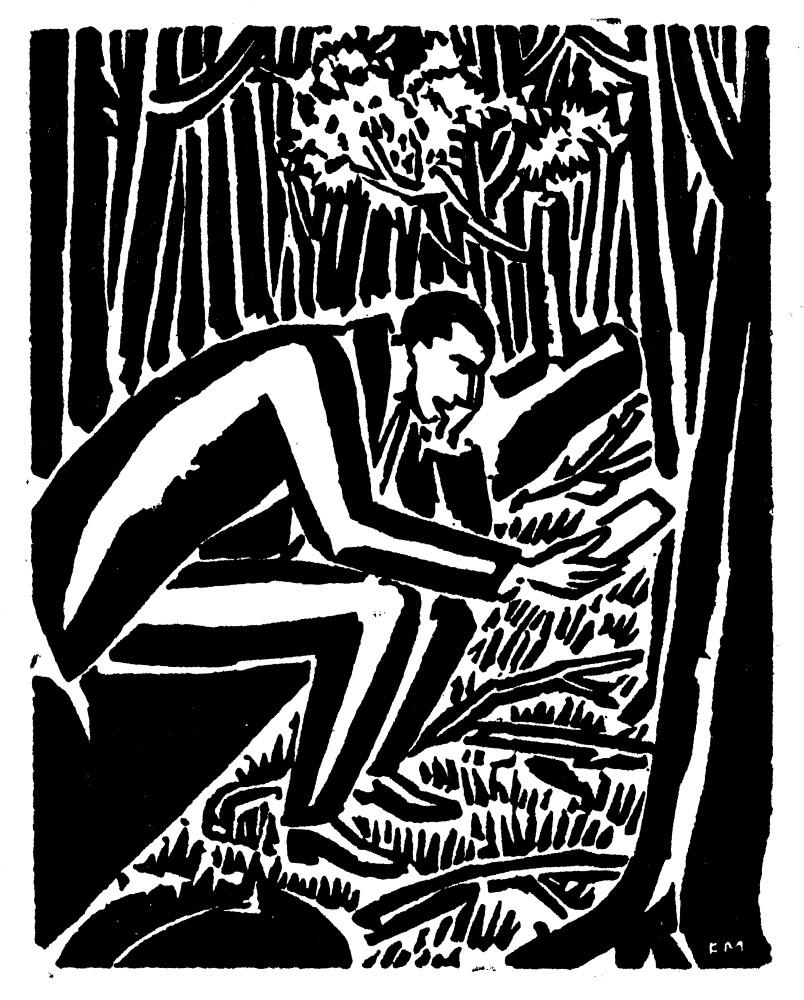

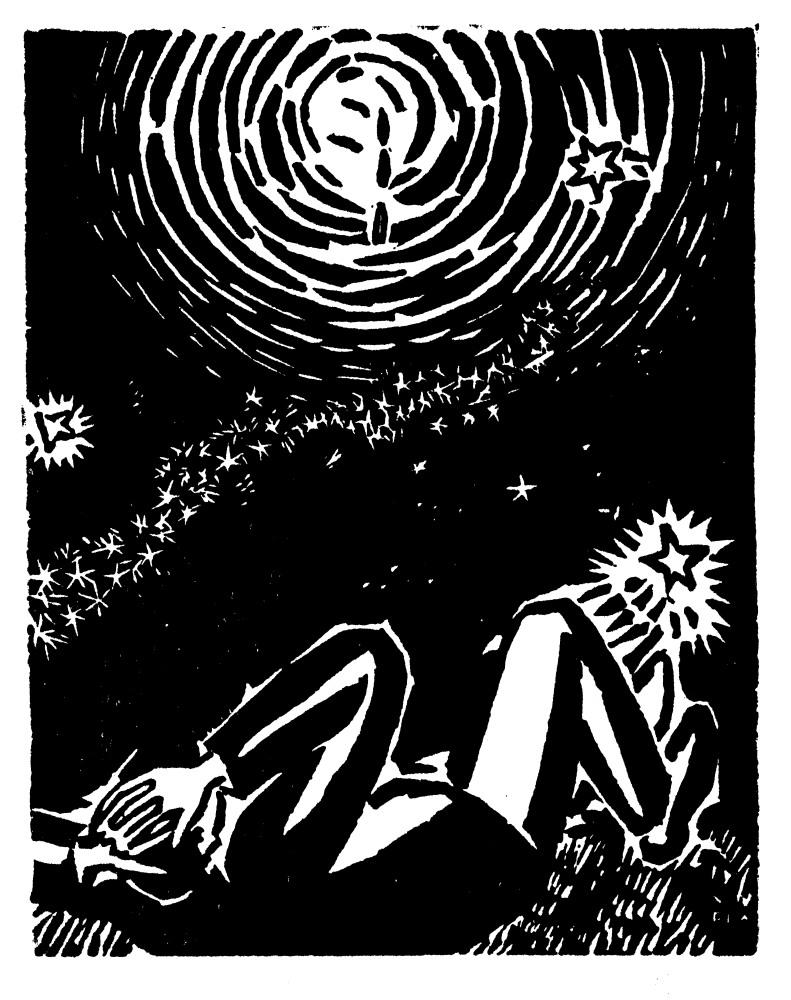

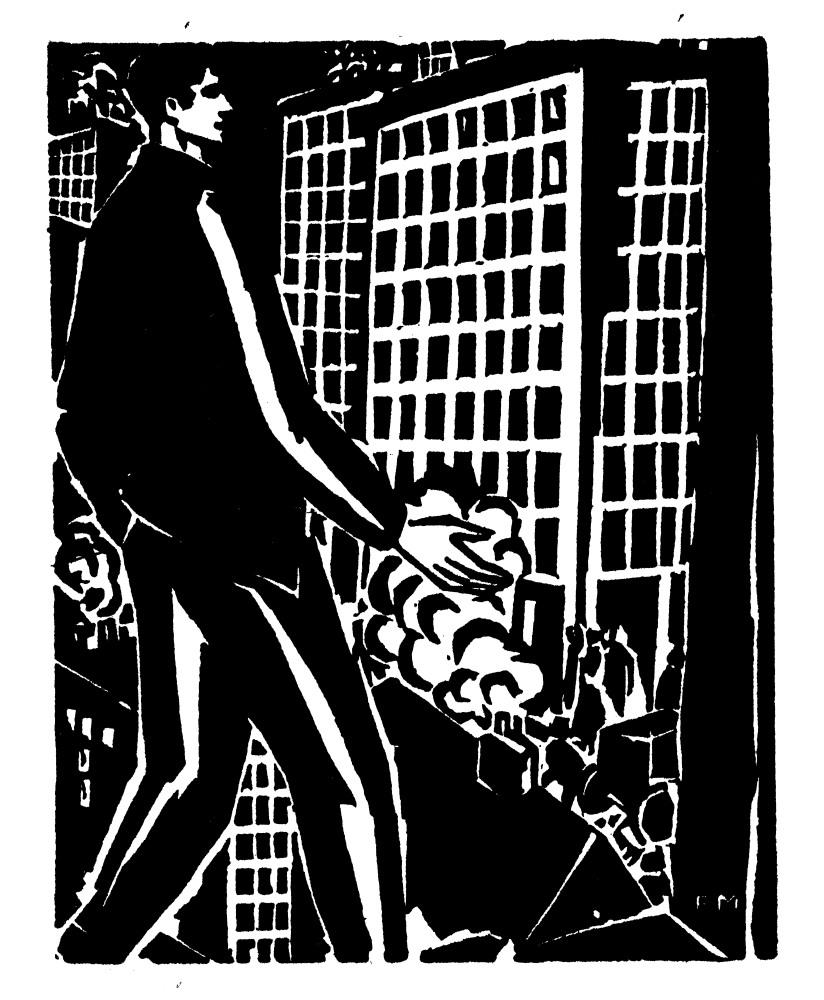

This is the story of a man who has drunk steadily of all the springs of life. He has known all its joys; all its illusions, all its disappointments. Exhausted by disillusionment, he whips with his contemptuous laughter this humankind which he had loved so well, and fleeing from it, he goes to search in the wilderness, to become lost there, for the peace of Nature and of Death who inevitably crushes in her fangs the vanity of life.

An overflowing of tempestuous ideas, where sharp satire is combined with the crude and grotesque humour of the old Dutch masters, bursts forth from this stormy intellect, so tormented that he knows no rest, and the creative fire is itself consumed. So much so that the hero of "The Sun," at the end of the work, falls from his dream in flames, like a torch-light. The mind of Masereel, possessed by hidden devils, lets itself go in a frenzy of maddened imaginings. I confess that it frightens me sometimes, and I hope that such a fancy will know enough to control itself and never lose its mastery over the force which it liberates. Let us just enjoy these outbursts of genius, of which we have few enough these days! They call to mind the great painters of the Romantic School, and the masters of the Sixteenth Century.

May this “Book of Hours” carry to America the name and the fame of Frans Masereel! And may it bear witness to the inexhaustible life-torch which still bursts forth from that genial, heroic old country of Flanders!

ROMAIN ROLLAND.

Paris

MY BOOK OF HOURS

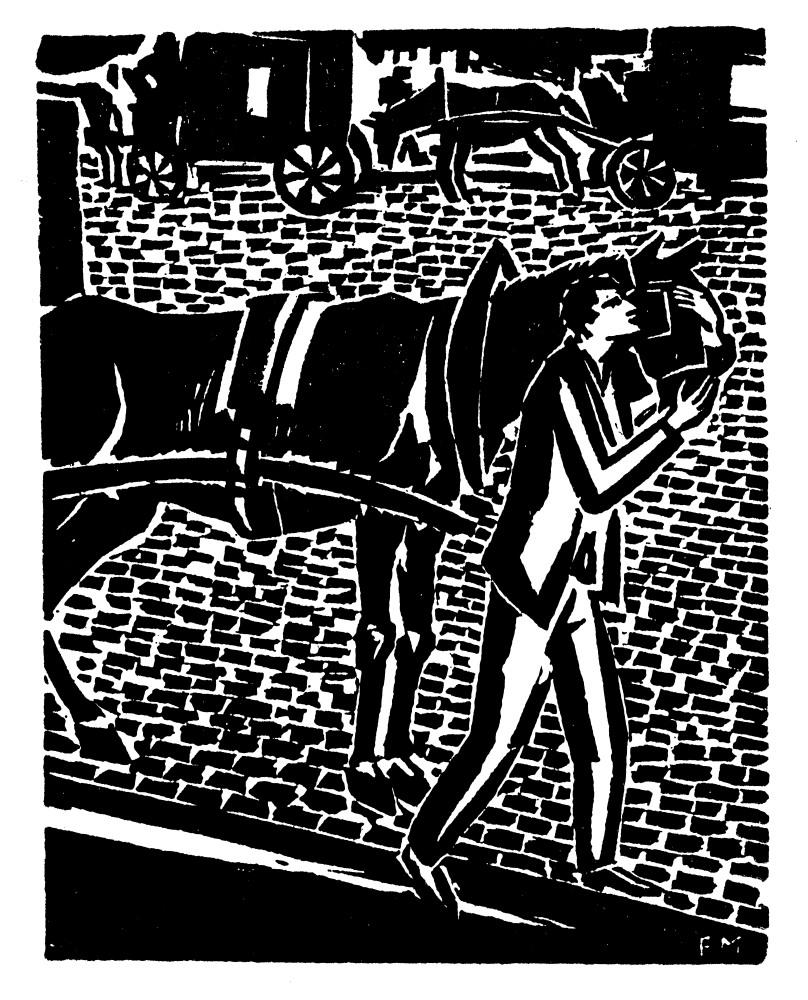

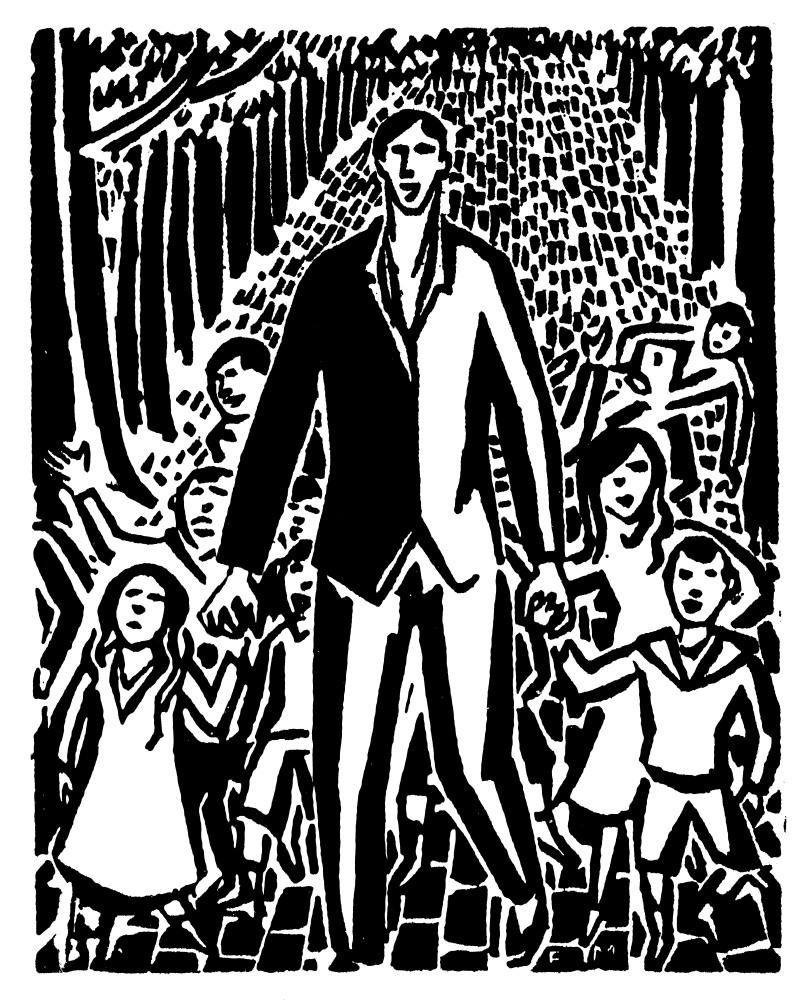

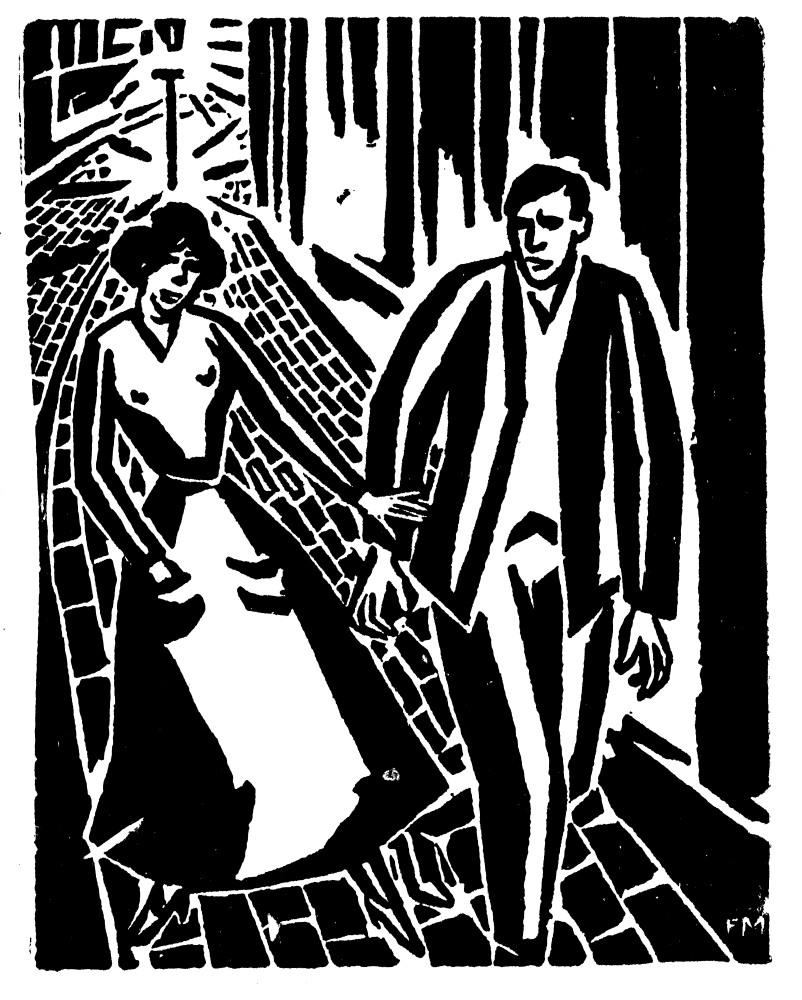

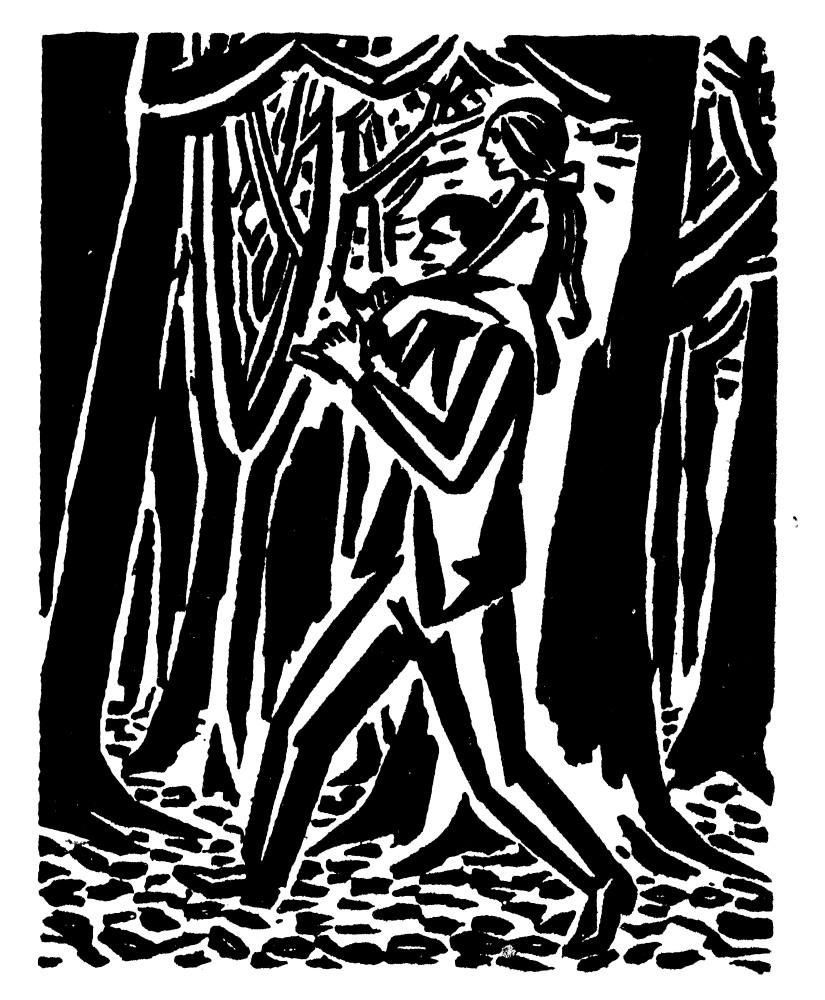

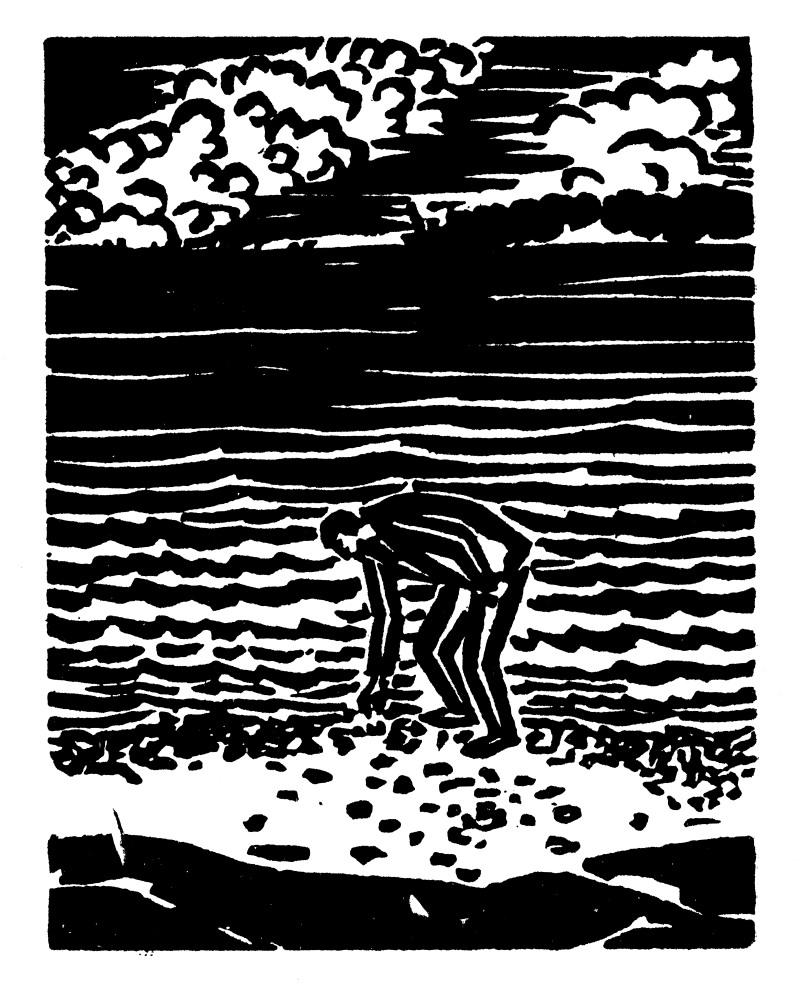

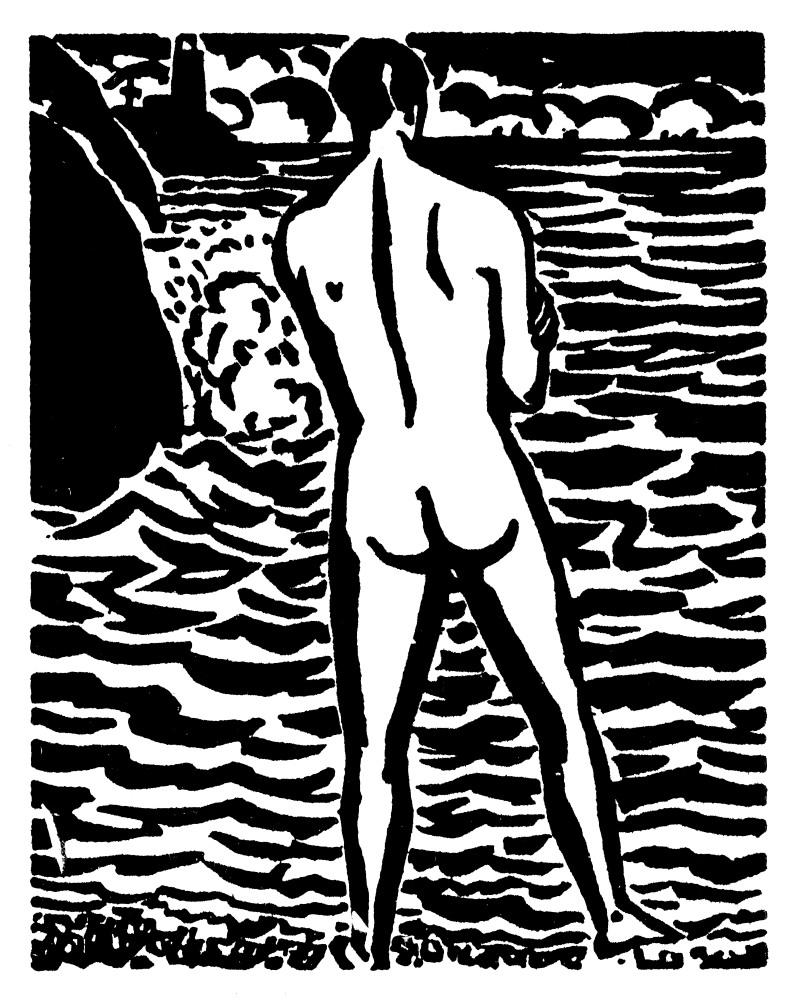

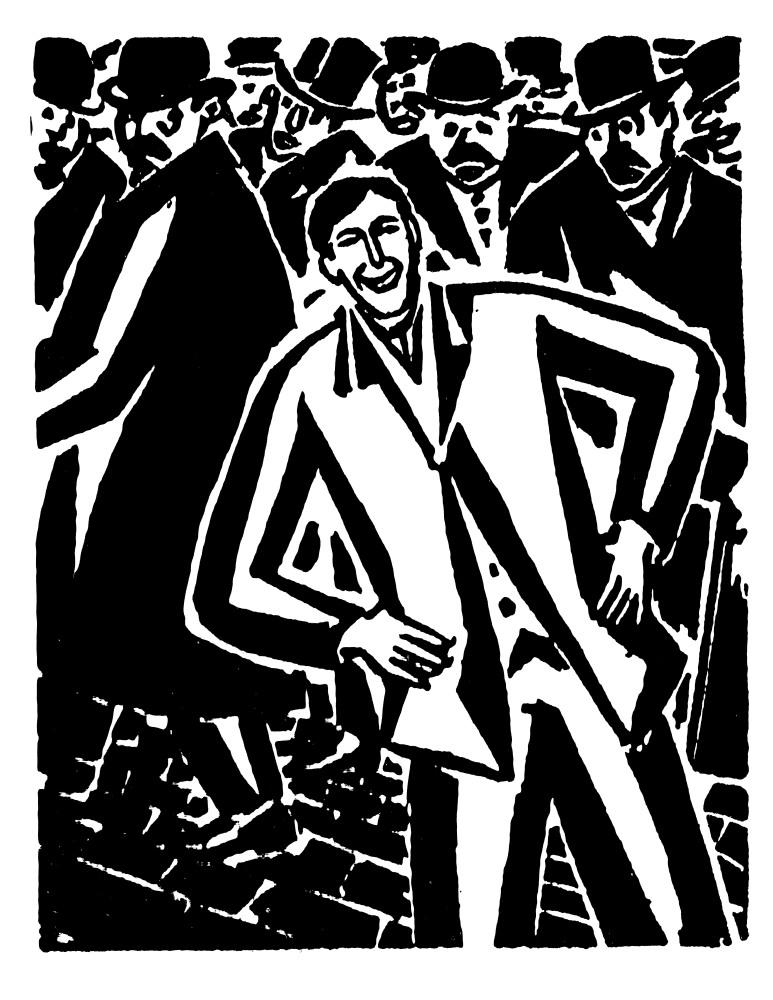

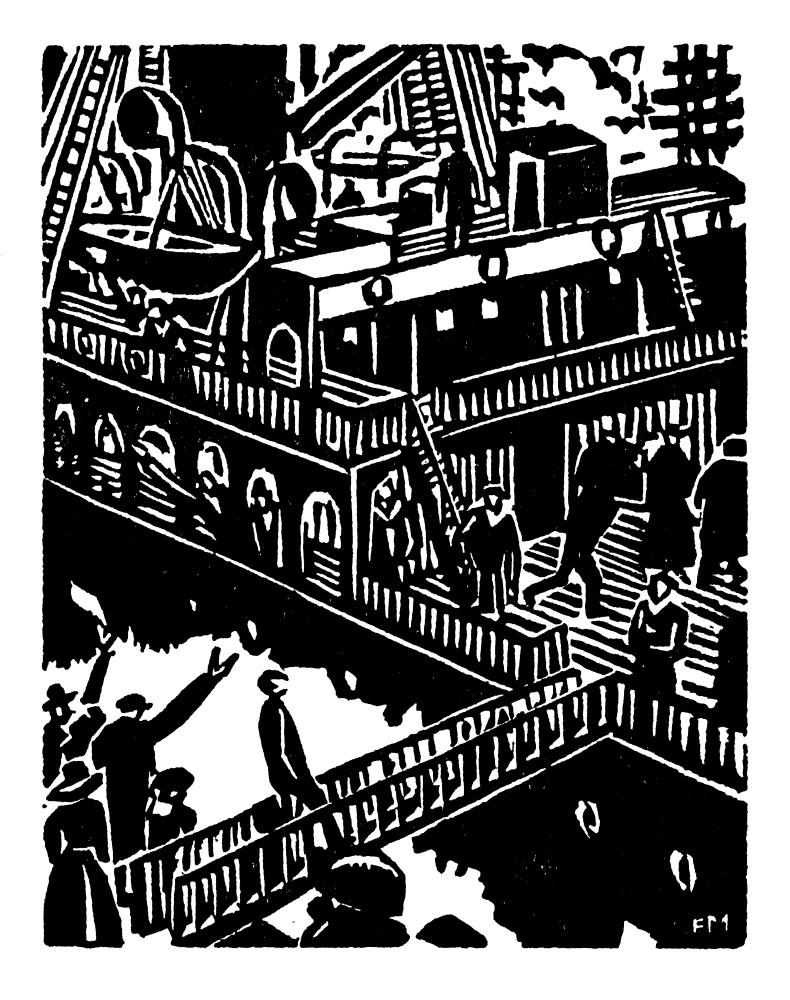

Here is the story of a man who goes into life with young eyes, with a spirit fresh and naive, with strong, young limbs, with a heart full of love and tenderness.

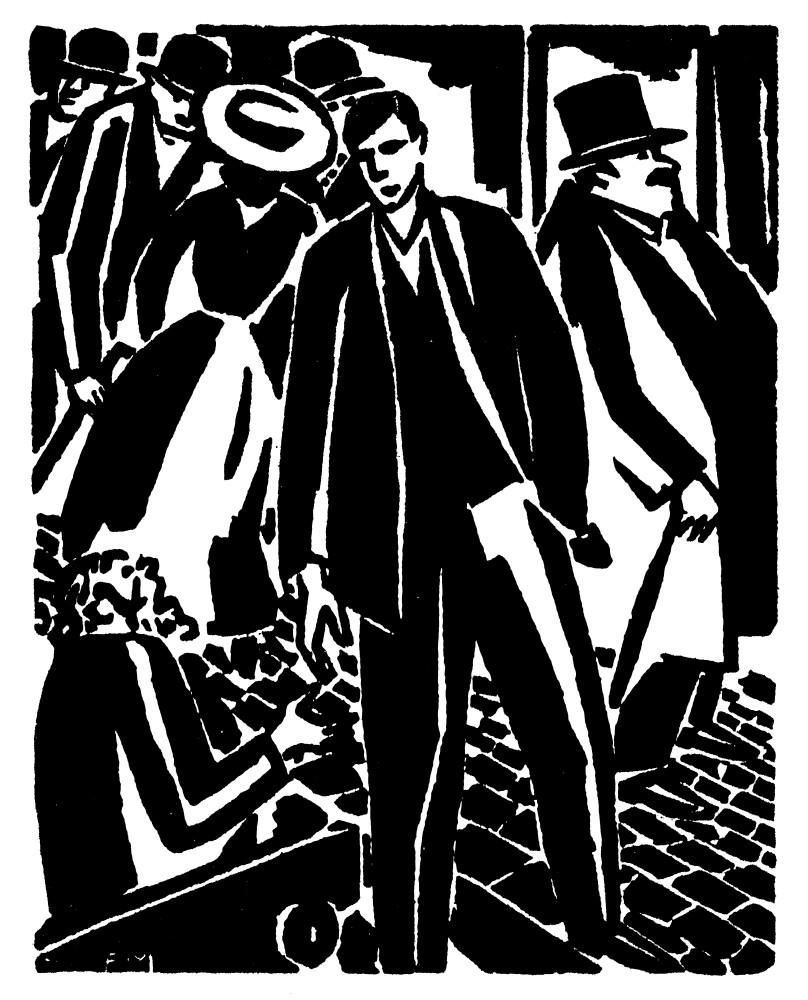

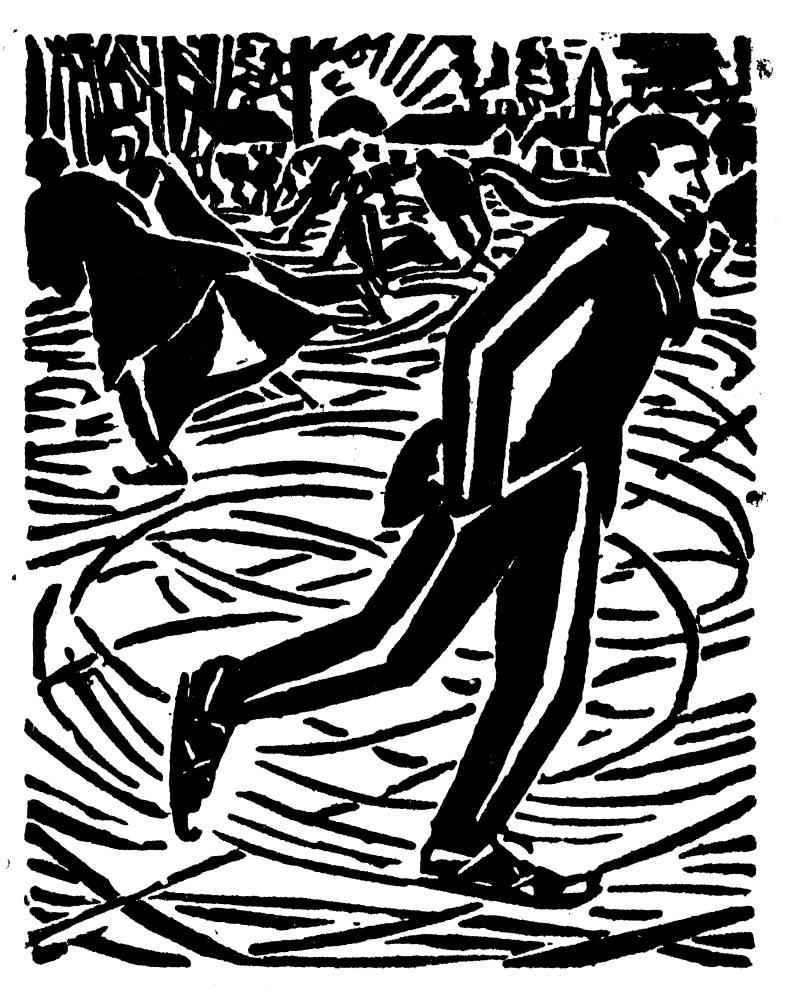

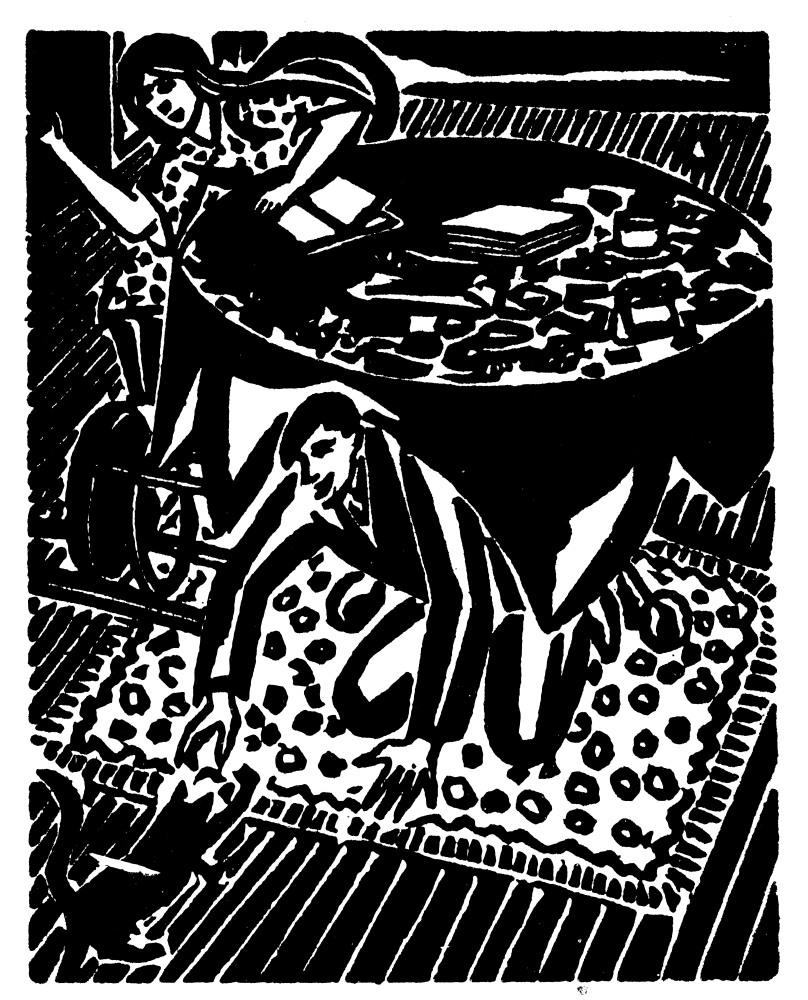

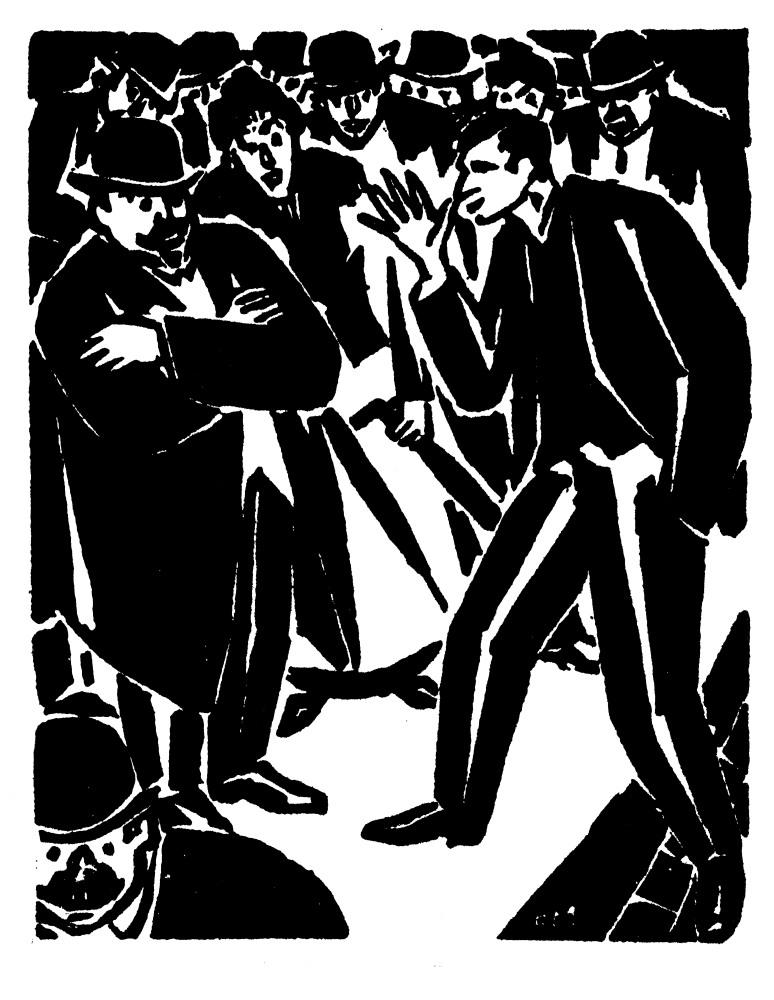

Everything interests him, everything is new for him, he wishes to know everything, to love everything, and to hurl himself into the stream of life... only to come out wounded, bitter, skeptical and so forth.

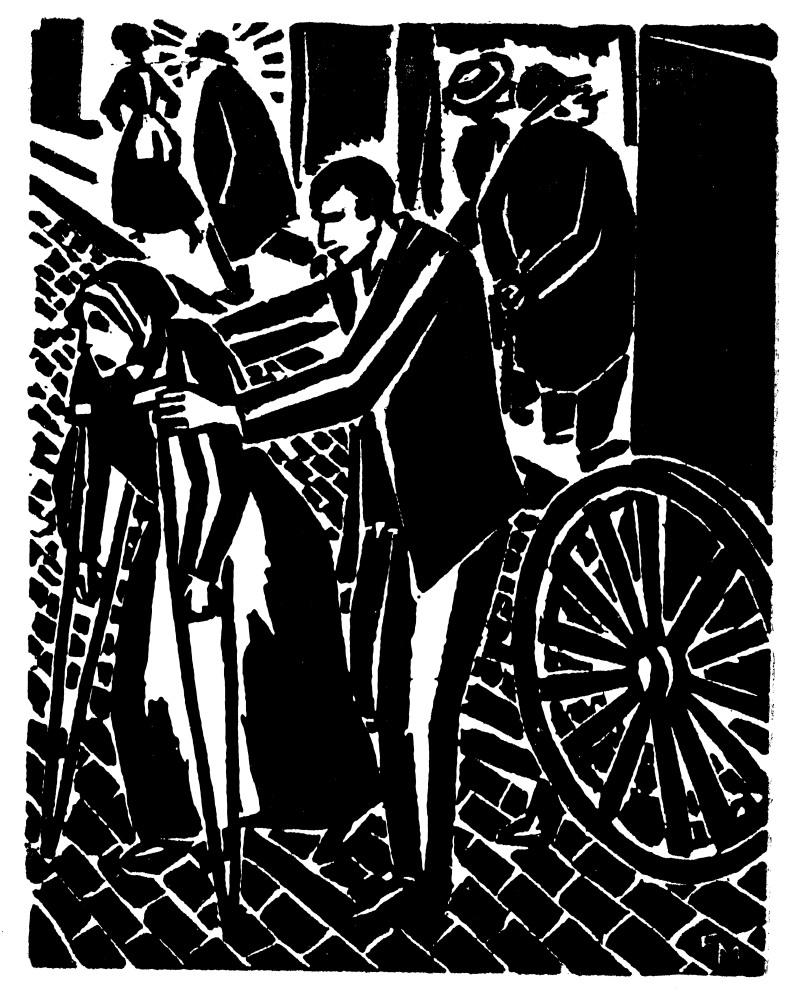

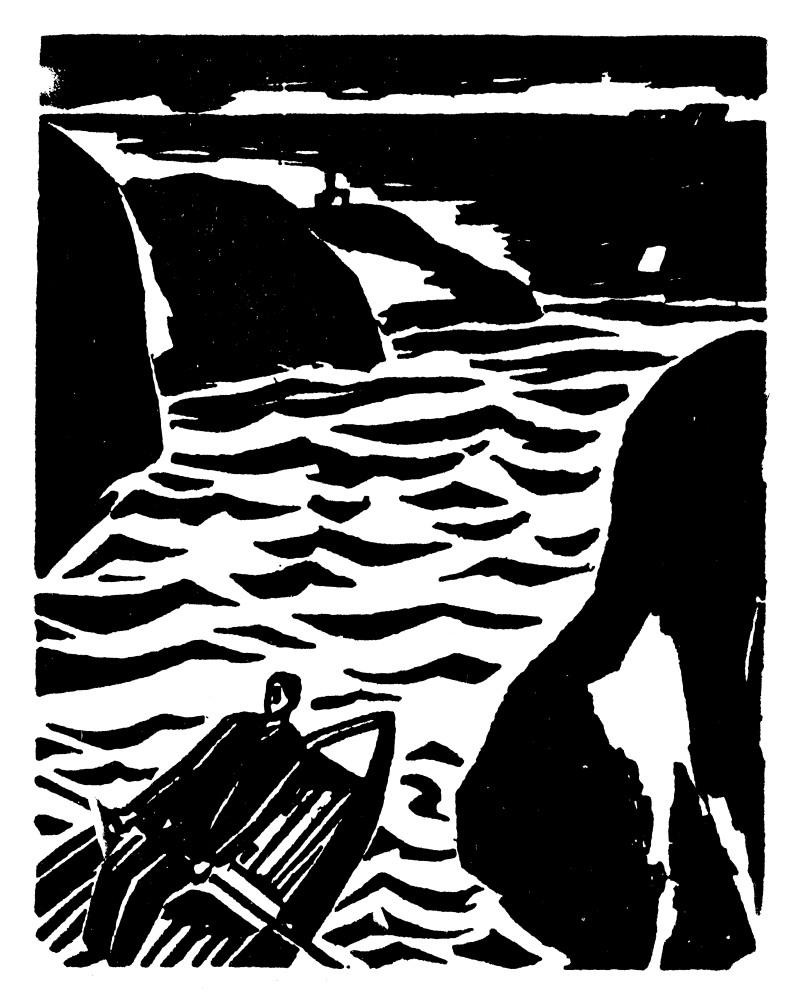

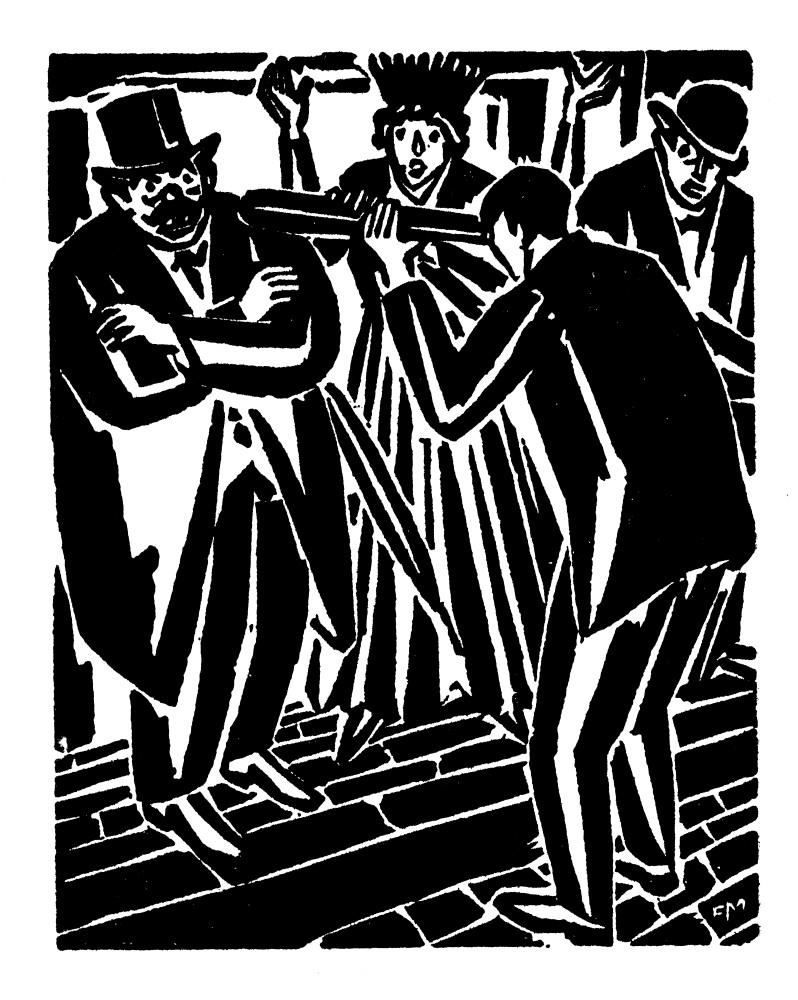

He is wise now, his eyes are more sophisticated, his spirit curbed... his strength is sapped by vices, and he mocks at the strong; his heart is sad.

He seeks solitude, wishes to die alone, like a savage wolf, but his spirit is reborn in a mocking and... laugh.

By the Same Author:

Twenty-five images of a man's passion (25 woodcuts).

The Sun (63 woodcuts).

Story Without Words (60 woodcuts).

A News Item (8 woodcuts).

The Idea (83 woodcuts).

Remember My Country (16 woodcuts).