Eric Fleischmann

Toward a Cooperative Agorism

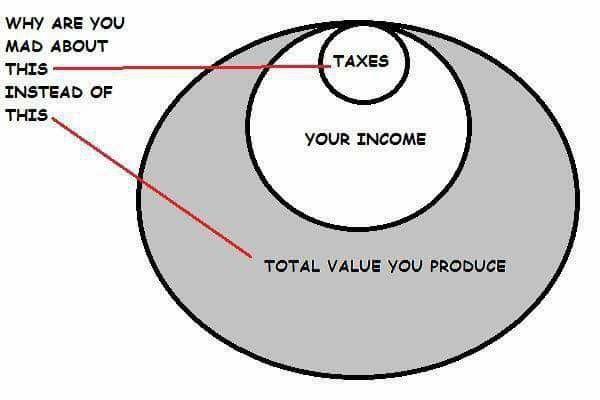

I have a saying that goes something like: ‘I don’t trust anybody who thinks taxation is theft but profit isn’t.’ The former is a common sentiment among libertarians left and right, who argue, like Michael Huemer, that “[w]hen the government ‘taxes’ citizens, what this means is that the government demands money from each citizen, under a threat of force: if you do not pay, armed agents hired by the government will take you away and lock you in a cage.”[1] The affirmative of the latter is a less well known sentiment but is rooted in Marxist exploitation theory. Richard Wolff explains in Democracy at Work: A Cure For Capitalism how profit…

is the excess of the value added by workers’ labor—and taken by the employer—over the value paid in wages to them. To pay a worker $10 per hour, an employer must receive more than $10 worth of extra output per hour to sell. Surplus is capitalists’ revenue net of direct input and labor costs to produce output.

This argument is based in the labor theory of value, which is rejected by most right-libertarians. Kevin Carson, in Studies in Mutualist Political Economy, rehabilitates it as the tendency of prices fall to the cost of production in the absence of artificial restrictions like state-sanctioned monopolies, but even if one rejects this, the logic of the LTV actually comes very close to the Lockean principle of ownership acquisition via mixing one’s labor. Cory Massimino explains:

For 19th century anarchists, the labor theory of value, or “cost limit of price,” was the natural extension of the individual’s absolute sovereignty over themselves. Labor was seen as the source for all wealth, and the laborer naturally owns the fruits of their labor as an extension of their self-ownership. Tucker’s theory of value was intimately related to his ethical views based on each individual having sole dominion over their body and their justly acquired property, which required labor mixing.

By this logic, profit could be considered theft from the same libertarian principles that outline taxation as such. And this has already more-or-less been done by proto-libertarians like Dyer Lum, who decries “taxation, profits, and rent” as “superimposed burdens” on “Labor.”

Most right-libertarians would argue, however, that profit is earned from the voluntary exchange between employer and employee based on the former’s ownership of the means of production. But one can take a libertarian position to as extreme a point as Karl Hess did and suggest that much of what people call private property is actually…

stolen. Much is of dubious title. All of it is deeply intertwined with an immoral, coercive state system which has condoned, built on, and profited from slavery; has expanded through and exploited a brutal and aggressive imperial and colonial foreign policy, and continues to hold the people in a roughly serf-master relationship to political-economic power concentrations.

One can also look at the primitive accumulation, subsidies, regulatory capture, and monopoly privileges that have favored capitalists over the entire course of U.S. and global history. As such, Carson proposes that, from the dialectical libertarian perspective outlined by Chris Matthew Sciabarra, “the corporate economy is so closely bound up with the power of the state, that it makes more sense to think of the corporate ruling class as a component of the state.” This would ultimately mean that, like Logan Glitterbomb explains, because all large-scale private ownership of the means of production is “the result of theft, coercion, enclosure, corporate subsidies, state licensing regimes, zoning laws, government bailouts, tax breaks, intellectual property laws, and other political favors,” it is therefore “illegitimate,” and capitalists have less of a claim to its ownership than the worker. Glitterbomb allows “while, yes, if the original owner can be found, the property should revert back to their control and the decisions about what to do with it should rest with the original legitimate owner, as [Murray] Rothbard and many others have pointed out, finding the original or ‘legitimate’ owner can sometimes prove to be difficult or even impossible. It was in such a case that Rothbard claimed that the next best option was to turn such property over to those who have put the most labor into it recently, the workers.” By this analysis, workers generally have a greater claim over the means of production than capitalists, thereby making the extraction of surplus value a form of theft.

If one accepts this argument, what then is next in terms of praxis? The immediate solution to the taxation problem according to many libertarians is agorism. Agorism, as a refresher, is a left-libertarian anarchist strategy developed by Samuel Edward Konkin III that, as Derrick Broze explains,

seeks to create a society free of coercion and force by using black and gray markets in the underground or “illegal” economy to siphon power away from the state. Konkin termed this strategy “counter-economics”, which he considered to be all peaceful economic activity that takes place outside the purview and control of the state. This includes competing currencies, community gardening schemes, tax resistance and operating a business without licenses. Agorism also extends to the creation of alternative education programs, free schools or skill shares, and independent media ventures that counter the establishment narratives.

It is important to note, however, that not all agorism must take place in the grey or black market—only horizontal agorism must meet this criteria. Broze describes alternatively a vertical agorism that includes things like “participating in and creating community exchange networks, urban farming, backyard gardening, farmers market, supporting alternatives to the police, and supporting peer to peer decentralized technologies.” These practices “can be considered agorist in the sense that they are aimed at building self and community reliance rather than dependence on external forces, but they are not explicitly counter-economic because they do not involve black and grey markets.”[2] This is not only about taxes as it runs deeper toward avoiding as much state intervention as possible, but the movement toward black, grey, and informal markets is generally avoidant of taxation in one way or another.

This covers taxation, but what about profit? Interestingly, while ‘taxation is theft’ appears to be a more well known slogan than ‘profit is theft,’ the solution to the latter is perhaps more well known: cooperatives. Based on the assertion that the primary problem of capitalism is the exploitation of surplus, Wolff advances that worker-owned businesses should replace “the current capitalist organization of production inside offices, factories, stores, and other workplaces in modern societies. In short, exploitation—the production of a surplus appropriated and distributed by those.” In such an enterprise, profit as it exists in capitalist businesses does not appear even when the profit motive is utilized because the surplus value is controlled democratically as opposed to being appropriated by capitalists. And worker-owned cooperatives, as with all cooperatives, function under seven central principles:

-

Voluntary and Open Membership

-

Democratic Member Control

-

Member Economic Participation

-

Autonomy and Independence Education

-

Training and Information

-

Co-operation among Co-operatives

-

Concern for Community

These principles define not just individual cooperatives but the cooperative movement as a whole, which whether explicitly or not, is attempting to shift the primary mode of production to a cooperative one. For example, Cooperation Jackson outlines their “basic theory of change” as being “centered on the position that organizing and empowering the structurally under and unemployed sectors of the working class, particularly from Black and Latino communities, to build worker organized and owned cooperatives will be a catalyst for the democratization of our economy and society overall.”

What I propose then is that principled opposition to both taxation and profit be combined into a ‘cooperative agorism.’ Admittedly this term is already in use by the subreddit r/cooperativeagorism, who describe it as “a social strategy, that consists of influencing the political landscape by means of peacefully improving and strengthening civil society in critical ways.” These include things like a Farm-To-Consumer Defense Fund or the mafia distributing food to those in need in Italy. And what I’m talking about is certainly not mutually exclusive from this but rather more specifically the practice of agorism using cooperative principles. Let’s say Emma is selling x, where x is a (non-violent) illegal or off-the-books product or service. Instead of selling x as an individual, Emma could pool her resources with other interested parties and establish an informal cooperative outside of the taxable wage labor economy. Emma could start an off-the-grid, farm-to-consumer herbalist commune or get all the kids in the neighborhood into an equal-shares babysitting business or team up with IT nerd friends to undersell big tech corporations in their city with a DIY computer co-op. In all these scenarios, profits would be pooled and distributed democratically, resources and knowledge would be shared with other informal (and sometimes formal) co-ops, and concern for the local community would be a high priority.

A fairly new and innovative example of this type of project is—despite my strong misgivings about blockchain and cryptocurrency—the DAO (decentralized autonomous organization).[3] These organizations are “designed to be automated and decentralized” and act primarily “as a form of [cryptocurrency] venture capital fund, based on open-source code and without a typical management structure or board of directors.” A post on Comrade Cooperation accounts how “[t]he switch from a 9–5 job to becoming a part of a DAO gave me an entirely new vision of work” because…

I have become the manager of my own work. I track hours on the tasks I complete. I review my peers’ work and we all vote on the next steps of the two big projects we are building. This allows us to keep everything transparent, and each member’s contribution is rewarded with a share of the profits. The system is fair, and all the rules and decision[s] we make are recorded on the Blockchain.

These function through the blockchain, which—though not as decentralized as many would have you think—allow them to stay out of the reach of the state in many instances. And because of its use of blockchain and cryptocurrency, this follows the classic style by which, according to Glitterbomb, “many libertarians advocate [cryptocurrency] specifically along with the agorist tactic of avoiding taxes. The idea is that by not paying taxes one will ‘starve the state.’” And not only are, as Emmi Bevensee, Jahed Momand, and Frank Miroslav point out, “a handful of projects . . . now focusing on these innovations in stewardship from an Ostromian point of view, even going so far as adopting Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) wholly into the goals of their projects,” but there are numerous groups “working to build tools to enable cooperation across DAOs and protocols. All of them are ostensibly, in their outward-facing messaging and their daily practice, collectively governed projects that are trying to build open-source, freely available tools and components for cooperative economies to scale themselves on blockchains” [4]. DAOs can also be put toward funding broader community projects such as “Indigenous land back,” “BIPoC artist collectives,” community workshops, and free medical clinics. All of these factors together—workplace democracy, cryptocurrency, open-source code, etc.—make DAOs an ideal template from which to elaborate a cooperative agorism.

Admittedly, in large part because of their small scale in what Konkin calls the current “Low-Density Agorist Society” in the New Libertarian Manifesto, most agorists entrepreneurs already circumvent the capitalist business structure entirely. The independent carpenter working through Craigslist, the mom selling vegetables from her backyard garden to her neighbors, the basement cryptocurrency investor, and the ‘humanitarian’ entrepreneur smuggling needed medical supplies into countries in crisis are obviously already operating to some degree outside of anything like the wage labor economy. As such, one of Rothbard’s main critiques of agorism is that…

Konkin’s entire theory speaks only to the interests and concerns of the marginal classes who are self-employed. The great bulk of the people are full-time wage workers; they are people with steady jobs. Konkinism has nothing whatsoever to say to these people.

And while Konkin describes agorism as “profitable civil disobedience” and proclaims in the New Libertarian Manifesto that “[t]he fundamental principle of counter-economics is to trade risk for profit [emphases added],” Glitterbomb points out in her article “Toward an Agorist-Syndicalist Alliance” that “[e]ven Konkin couldn’t help but notice the exploitative nature of corporate hierarchy, believing it to be some of the lasting remains of feudalism and that if the individual were truly respected, bosses would slowly become a thing of the past.” Additionally, many of the practices that full under the term agorism like “alternative education programs, free schools or skill shares” are already inherently communitarian. The purpose of this piece then is not entirely to propose a new approach but to render an existing one more explicit. This is similar to what agorists are already doing by trying to transform existing counter-economic behavior into conscious agorist action. Broze explainshow “[it] is important to distinguish counter-economic activity from full on Agorist activity,” and, as such, agorists like Jesse Baldwin insist “[w]e should practice the right to disregard the law, . . . but we have to do it in a way that is conscious rather than opportunistic.” But even further, we should seek to imbue agorism with cooperative principles as we work to raise the counter-economy up as explicitly agorist.

This is particularly important because of the attempt by anarcho-capitalists to co-opt agorism. This process is already underway, as the movement—despite Konkin’s explicit anti-capitalism—is continually branded with the black and yellow of anarcho-capitalism. Of course, there is nothing wrong with individual ancaps practicing agorism. Konkin openly admits in a 2002 interview that “[i]n theory, those calling themselves anarcho-capitalists do not differ drastically from agorists; both claim to want anarchy (statelessness, and we pretty much agree on the definition of the State as a monopoly of legitimized coercion, borrowed from Rand and reinforced by Rothbard).” However, “the moment we apply the ideology to the real world (as the Marxoids say, ‘Actually Existing Capitalism’) we diverge on several points immediately.” This applicational failure is a kind of vulgar libertarianism, where an actually free market is haphazardly and inconsistently conflated with capitalism, and the result is, as Konkin explains in the aforementioned interview, that “the ‘Anarcho-capitalists’ tend to conflate the Innovator (Entrepreneur) and Capitalist” and, furthermore, end up with no genuine theory of class and class struggle like agorists have. And it is these failures that lead pseudo-agorist ancaps to advocate neo-feudal projects like private cities and seasteading where private companies would rule over micronations in a real-world version of the city of Rapture from Bioshock or a throwback to the rule of India by the East India Company. These are rather extreme examples and it can be assumed that most ancaps practicing agorism are not attempting to build their own cities. But the truth is that ancaps like Rothbard, as Peter Sabatini argues, allow for “countless private states” and see “nothing at all wrong with the amassing of wealth, therefore those with more capital will inevitably have greater coercive force at their disposal.” And while folks like Anna Morgenstern and David Graeber make compelling cases that without the state nothing like wage labor could exist in a stateless society, as we—if Konkin’s theory of social change outlined in the New Libertarian Manifesto proves correct—move toward an agorist society of greater density and “the statists take notice of agorism,” it must be made clear that this is not meant to build a refuge for advocates of child labor and sweatshops from the minimal state protections for workers or to create some sort of anarchs-capitalist Panama Papers situation, but rather the beginnings of a new anti-capitalist, cooperative mode of production and exchange.

This cooperative agorism can be linked to the practice that Wesley Morgan (disapprovingly) calls “market syndicalism,” where anarchists look “to create ‘dual power’ through the creation of cooperatives.” Morgan asserts that “[w]hile these cooperatives are internally self-managing, they exist as units in a market economy, they still rely upon access to the market.” I will not go into a full rebuttal of Morgan’s point but rather point out the assumption that there is only one unified market—a claim that agorists contest. Certainly the formal, white market economy is riddled with statist privileges that render a lot of cooperative efforts sterile. Glitterbomb maintains, in “Bullshit Jobs and the End of Work (As We Know It),” that “to give worker cooperatives a real fighting chance, we have to abolish the web of state subsidies, occupational licensing, and corporatist regulations that all work together to limit market competition and disproportionately advantage capitalist business models.” But this presents the possibility that by avoiding restrictions of the capitalist economy, cooperatives in the counter-economy have an even greater chance of success. However, integral to this project is continued cooperative and syndicalist work within the unfree capitalist market—despite its restrictions—but with the ultimate goal of unifying it with the cooperative agorist projects. In “Toward an Agorist-Syndicalist Alliance,” Glitterbomb proposes that…

[w]hile agorists build alternatives to the white market within the black and grey markets, syndicalists could focus on challenging existing white market entities from the inside, eventually taking them over as Rothbard advocated. But it doesn’t have to stop there. Agorists should indeed advocate that syndicalists go even further. Once a white market business is successfully syndicalized, agorist-syndicalists should help transition the business into the agora. The newly collectivized business should eventually do what all good agorist businesses do: ignore state licensing regimes, refuse to pay taxes, engage in the use of alternative currencies, and generally disregard statist interference with their business dealings.

And if the goal is to generate an anti-capitalist, cooperative economy, the combination of cooperative agorism and agorist-syndicalism can be considered forms of venture communism, the scheme, as described by Glitterbomb in “Bullshit Jobs and the End of Work (As We Know It),” “which seeks to invest in cooperatives and outcompete capitalist firms” and ultimately use “worker cooperatives as a means to achieve communist outcomes via market means.” This communist end goal is twofold: Karl Marx explains that “[i]f co-operative production is not to remain a sham and a snare; if it is to supersede the capitalist system; if united co-operative societies are to regulate national production upon common plan, thus taking it under their own control, and putting an end to the constant anarchy and periodical convulsions which are the fatality of capitalist production – what else . . . would it be but communism, ‘possible’ communism?” But even when that “common plan” must necessarily be spontaneous and decentralized for Hayekian reasons, Carson asserts that removing barriers to production and allowing “free market competition in socializing progress,” as would be the case in the agora, “would result in a society resembling not the anarcho-capitalist vision of a world owned by the Koch brothers and Halliburton, so much as Marx’s vision of a communist society.”

[1] A nuanced libertarian position on taxation can be found in my piece “An Anti-Statist Beginner’s Guide to (Taxation, Public Budgets, and) Participatory Budgeting.”

[2] While Broze believes that vertical agorism does not qualify as counter-economics, Glitterbomb contends that “if these tactics directly challenge state and corporate power how are they not counter-economic?”

[3] For critical opinions on blockchain and related technologies, see my pieces “NFTs Suck for Labor” and “Crypto Will Not Save Us From the Workplace.”

[4] See Wikipedia for a diagram of the IAD framework.