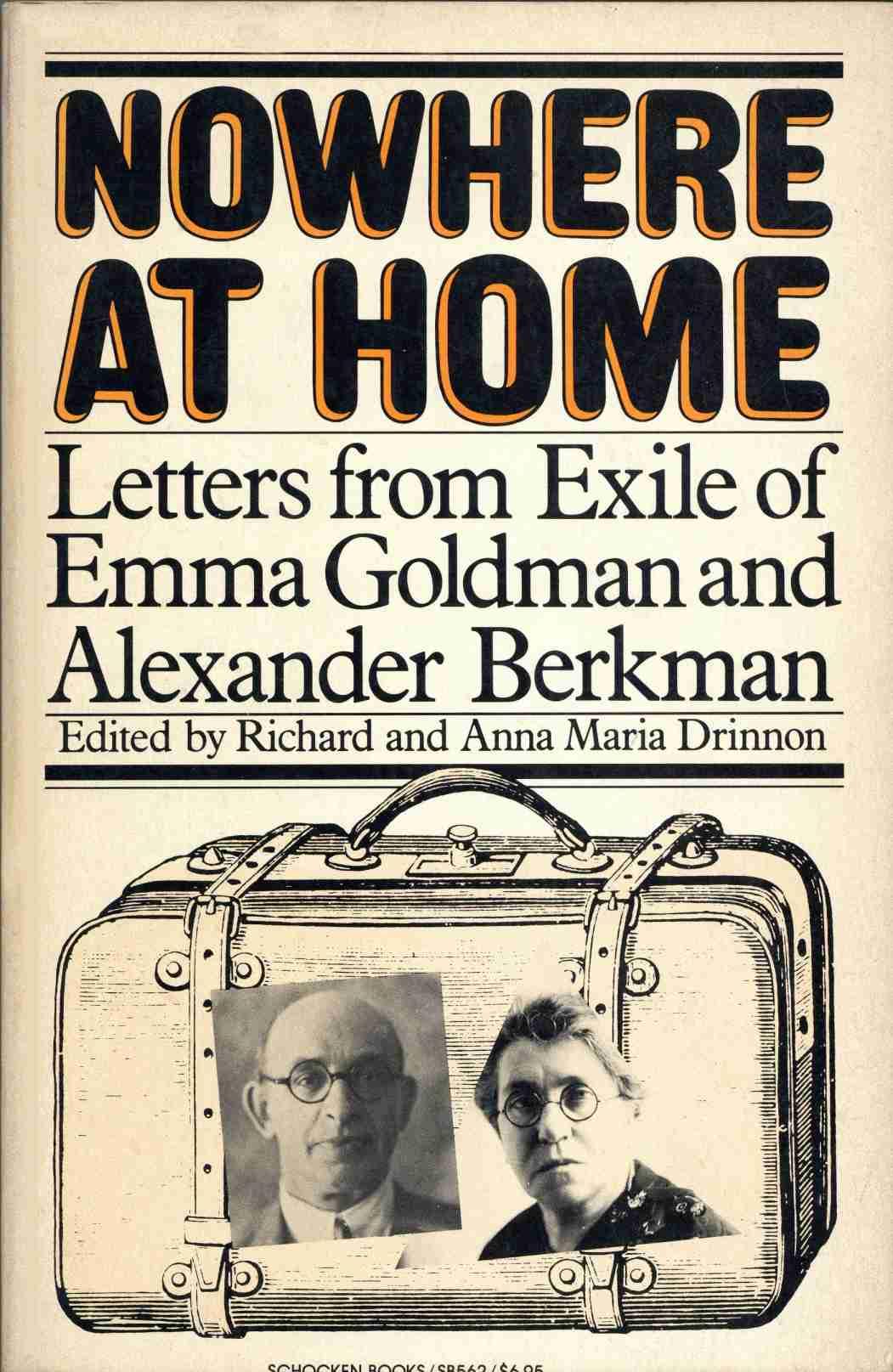

Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman

Nowhere at Home

Letters from Exile of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman

To 1919: Autobiographical Fragment and Chronology

Autobiography of Alexander Berkman (Rough Outline)

EG TO ELLEN KENNAN, July 24, 1919, JEFFERSON CITY

EG TO STELLA COMINSKY, August 30, 1919, JEFFERSON CITY

AB TO M. ELEANOR FITZGERALD, September 7, 1919, ATLANTA

STATEMENT BY ALEXANDER BERKMAN IN RE DEPORTATION

STATEMENT BY EMMA GOLDMAN AT THE FEDERAL HEARING IN RE DEPORTATION

EG AND AB TO DEAR FRIENDS, December 19, 1919, ELLIS ISLAND

Part 2: Communism and the Intellectuals

AB TO M. ELEANOR FITZGERALD, February 28, 1920, MOSCOW

EG TO ELLEN KENNAN, April 9, 1922, STOCKHOLM

AB TO DR. MICHAEL COHN, October 10, 1922, BERLIN

AB TO LILLIE SARNOV, July 22, 1924, BERLIN

AB TO DR. MICHAEL COHN, September 16, 1924, BERLIN

EG TO AB, December 20, 1924, LONDON

EG TO AB, December 22, 1924, LONDON

EG TO HAROLD I. LASKI, January 9, 1925, LONDON

ERIC B. MORTON TO EG, February 23, 1925, SAN FRANCISCO

EG TO TED McLEAN SWITZ, March 10, 1930, PARIS

AB TO EG, November 14, 1931, ST. TROPEZ

EG TO AB, November 18, 1931, PARIS

EG TO AB, December 1, 1932, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, December 3, 1932, NICE

EG TO FREDA KIRCHWEY, August 2, 1934, TORONTO

AB TO EG, November 4, 1934, NICE

EG TO AB, January 5, 1935, MONTREAL

EG TO AB, January 24, 1935, MONTREAL

EG TO ROGER BALDWIN, June 19, 1935, ST. TROPEZ

EG TO AB, November 26, 1935, LONDON

Part 3: Anarchism and Violence

EG TO HAVELOCK ELLIS, November 8, 1925, BRISTOL

EG TO BEN CAPES, February 16, 1927, PARIS

AB TO EG, June 24, 1927, PARIS

EG TO AB, July 4, 1927, TORONTO

EG TO AB, December 17, 1927, TORONTO

AB TO EG, June 25, 1928, PARIS

EG TO EVELYN SCOTT, June 26, 1928, ST. TROPEZ

EG TO AB, June 29, 1928, ST. TROPEZ

EG TO AB, July 3, 1928, ST. TROPEZ

EVELYN SCOTT TO EG, July 31, 1928, WOODSTOCK, NEW YORK

AB TO EG, November 19, 1928, ST. CLOUD

EG TO AB, November 23, 1928, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, Monday [late November 1928], ST. CLOUD

EG TO HENRY ALSBERG, March 24, 1931, NICE

EG TO MAX NETTLAU, January 24, 1932, PARIS

AB TO EG, February 9, 1932, NICE

AB TO MOLLIE STEIMER, August 16, 1933, NICE

EG TO AB, March 23, 1934, CHICAGO

EG TO AB, June 16, 1934, TORONTO

AB TO EG, June 21, 1934, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, November 25, 1934, NICE

EG TO AB, February 12, 1935, MONTREAL

AB TO PAULINE TURKEL, March 21, 1935, NICE

EG TO C.V. COOK, September 29, 1935, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, December 9, 1935, NICE

FRANK HARRIS TO EG, January 23, 1925, NICE

ISADORA DUNCAN TO AB, April 8, 1925, NICE

EG TO AB, May 28, 1925, LONDON

EG TO FRANK HARRIS, August 7, 1925, LONDON

EG TO AB, September 4, 1925, LONDON

EG TO AB, September 10, 1925, LONDON

AGNES SMEDLEY TO EG, Sunday, BERLIN

EVELYN SCOTT TO EG, October 6, 1926, LISBON

EG TO EVELYN SCOTT, November 21, 1927, TORONTO

EG TO BEN REITMAN, December 17, 1927, TORONTO

EG TO AB, February 20, 1929, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, May 11, 1929, ST. CLOUD

EG TO AB, May 14, 1929, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, May 20, 1929, ST. CLOUD

EG TO AB, May 24, 1929, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, May 26, 1929, ST. CLOUD

AB TO EG, Tuesday [ca. Summer 1929], NICE

EG TO HENRY ALSBERG, June 27, 1930, BAD EILSEN, GERMANY

EG TO EMMY ECKSTEIN, June 10, 1931, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, November 23, 1931, NICE

AB TO EG, December 22, 1931, NICE

EG TO AB, December 25, 1931, PARIS

THOMAS H. BELL TO EG, January 14, 1932, LOS ANGELES

EG TO DR. WILLIAM I. ROBINSON, January 26, 1932, PARIS

EG TO THOMAS H. BELL, February 8, 1932, PARIS

EG TO MARY LEAVITT, November 2, 1932, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO M. ELEANOR FITZGERALD, November 11, 1932, NICE

EMMY ECKSTEIN TO EG, July 16, 1934, ST. TROPEZ

EG TO EMMY ECKSTEIN, July 30, 1934, TORONTO

EG TO AB, September 13, 1934, TORONTO

EG TO DR. SAMUEL D. SCHMALHAUSEN, January 28, 1935, MONTREAL

EG TO MAX NETTLAU, February 8, 1935, MONTREAL

EG TO AB, May 2, 1927, TORONTO

EG TO BEN CAPES, July 8, 1927, TORONTO

EG TO AB, August 19, 1927, TORONTO

AB TO TOM MOONEY, September 5, 1927, ST. CLOUD

EG TO EVELYN SCOTT, October 17, 1927, TORONTO

AB TO EG, April 11, 1929, ST. CLOUD

EG TO ARTHUR LEONARD ROSS, April 29, 1930, PARIS

AB TO MICHAEL COHN, June 6, 1930, PARIS

EG TO AB, August 23, 1931, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, August 26, 1931, NICE

AB TO EG, Wednesday, 10 A.M. [ca. October 1931], NICE

EG TO AB, Friday morning [ca. October 1931], ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, Friday evening [ca. Fall 1931], ST. TROPEZ

EG TO AB, March 6, 1932, BERLIN

EG TO AB, March 14, 1932, DRESDEN

AB TO EG, March 31, 1932, NICE

AB TO EG, Thursday P.M. [ca. summer 1932], NICE

EG TO AB, March 8, 1933, LONDON

AB TO EG, August 10, 1933, NICE

EG TO AB, August 12, 1933, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, August 15, 1933, NICE

EG TO AB, August 18, 1933, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO EG, August 22, 1933, NICE

EG TO AB, August 23, 1933, ST. TROPEZ

EG TO AB, November 26, 1933, PARIS

AB TO EG, November 27, 1933, NICE

AB TO EG, December 31, 1933, NICE

AB TO EG, January 14, 1934, NICE

EG TO HENRY ALSBERG, April 9, 1934, ST. LOUIS

EG TO AB, May 15, 1934, MONTREAL

EG TO AB, May 27, 1934, TORONTO

AB TO EG, June 3, 1934, ST. TROPEZ

AB TO TOM MOONEY, February 6, 1935, NICE

EG TO AB, February 23, 1935, MONTREAL

AB TO MICHAEL COHN, March 15, 1935, NICE

AB TO STELLA BALLANTINE, August 14, 1935, ST. TROPEZ

EG TO AB, November 19, 1935, LONDON

AB TO EG, November 24, 1935, NICE

EG TO AB, January 25, 1936, LONDON

EG TO AB AND EMMY ECKSTEIN, March 9, 1936, LONDON

EG TO AB, March 15, 1936, COVENTRY

AB TO EG, March 18, 1936, NICE

AB TO EG, March 21, 1936, NICE

EG TO AB, March 22, 1936, LONDON

EG TO AB, March 24, 1936, LONDON

AB TO EG, March 23, 1936, HOSPITAL PASTEUR, NICE

EG TO AB, June 27, 1936, ST. TROPEZ

EG TO COMRADES, July 12, 1936, ST. TROPEZ

EG TO JOHN DEWEY, May 3, 1938, LONDON

Dedication

For all exiles, external and internal

Acknowledgments

In the interwar years, especially following Hitler’s rise to power, those in flight from repression and terror frequently paused long enough in Amsterdam to drop off their personal and group archives. Their deposits at the International Institute of Social History make it today one of the great good places in the world for the study of radical and social movements. Our collection of letters comes thus most fittingly from manuscript holdings so largely built up by exiles. We are deeply grateful to the Director, Professor Fr. de Jong Edz., to Deputy Director Ch. B. Timmer, and to the staff for permission to go through the Goldman-Berkman Archives once again, to photocopy letters and copies of letters, and then to have the results published. Our obligation is all the greater since the Institute has an impressive list of source-material publications under its own imprint. And we are particularly indebted to Mr. Rudolf de Jong of the Institute’s anarchist section for making our most recent stay in Amsterdam so pleasant, for reading the collection at an early stage, and for his many valuable suggestions. Thanks to him and his associates, our return to Amsterdam was like coming home again.

Ian Ballantine, Emma Goldman’s present literary executor, graciously gave us permission to publish the exchanges of his great-aunt and Alexander Berkman.

Although this is first and foremost a collection of Goldman and Berkman letters, eight of those that appear below were written by their friends. For permission to publish individual letters or for their help in trying to locate literary executors, we wish to thank the following: Arthur Leonard Ross, Emma Goldman’s counselor and Frank Harris’s executor; Irma Duncan Rogers, Isadora Duncan’s protegee and friend; and Paula Scott, Evelyn Scott’s daughter-in-law.

Several letters in Part One were originally the property of Ellen Kennan, a libertarian teacher who was for many years a friend of Emma Goldman. These letters, along with many others, are presently in the ‘possession of her cousin, Esther Brack, of Modesto, California. We ran off copies of those we now publish, along with the others, and presented the lot to the International Institute. Since they have now been added to the other papers in the Goldman-Berkman Archives, we have not bothered to indicate the separate provenance of the few that appear below. We do record here our appreciation to Ms. Brack and to librarian Zoia Horn, our good friend, for bringing these letters to our attention.

Finally, our debt to Mollie Steimer and Senya Flechine is special. Living presently in Cuernavaca, Mexico, they have patiently tolerated our long distance queries about Yiddish phrases, supplied photographs and directed us to others, and helped with the identification of individuals. Fellow exiles of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, they are still managing, somehow, to live their principles in strange lands with “nowhere to go.” They have our admiration and thanks.

Contents

Introduction xi

Autobiographical Fragment and Chronology xxv

1 Cast Out 1

2 Communism and the Intellectuals 15

3 Anarchism and Violence 65

4 Women and Men 121

5 Living the Revolution 189

Postscript 261

Index 275 (not included)

Illustrations appear after pp. 63 and 187.

Introduction

“Back in France. Soon again requested to leave. Expelled again and again. Must get off the earth, but am still here. Nowhere to go, but awaiting the next order.”

—Alexander Berkman

“It is only now, when most of my friends have gone by the board and when I myself feel so cast out, pursued by the furies and nowhere at home, that the love of the few friends [left] has begun to stand out more beautifully than ever.”

—Emma Goldman

“For all men who say yes lie; and all men who say no—why they are in the happy condition of the judicious unencumbered travelers in Europe; they cross the frontiers into Eternity with nothing but a carpet-bag—that is to say, the Ego. Whereas those yes-gentry, they travel with heaps of baggage, and, damn them! they will never get through the Custom House.”

—Herman Melville

1.

In late 1931 Emma Goldman assured Alexander Berkman she had been writing faithfully:

“Got your letter of the 14th [of December] with enclosures. I don’t see why you should have been anxious. I wrote you the 9th, again the 13th, with a postcard between. And again the 14th. It seems to me I keep writing to you all the time. Anyhow I am glad you still care about your old sailor sufficiently to be anxious if you do not hear every day. May you never cease to be that.

“Dear heart, do you know what I keep busy with? Writing endless letters to America....Yesterday I worked over a letter to Arthur [Leonard Ross] in answer to four of his. I wrote ten pages. You can imagine how long it took me to do that. Besides, other letters to the States which had to be gotten out before this rotten old year is done with. I still have about fifteen to do. Fact is, I did not budge out of my [Paris] apartment all week. I will never make a good or rapid typist. I hate it and I grow ill if I keep long at the machine. My old neck and spine do not bear up under much strain. That’s how I keep busy. I know it is useless labor. But it is the only link in my life, to keep in touch with our friends in America. And so I keep at it.”

Keep at it she did, writing letter after letter to friends in America while managing somehow to send almost daily dispatches to her old comrade. Never ceasing to be eager to hear from her when they were separated, Berkman replied almost as frequently as she wrote.

The mail is terribly important to banished men and women like Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman: For them the postman never need ring twice. Uprooted persons by definition, exiles yearn to hear from family, comrades, editors, publishers, lawyers, acquaintances. Has a favorite brother, ill for so long, finally died? Will someone explain why a hitherto faithful correspondent writes only perfunctory notes? Does the silence of another old friend mean he has fallen off the face of the earth?

Did the corrected galley proofs actually get to a distant editor? If so, what egregious liberties is he taking with them? And where is the check for the advance? Questions breed more questions, submerge in the mails, and frequently fail to surface: “So much gets lost in the French mails,” Berkman complained to Emma in 1927. “That package sent to me at St. Tropez, you remember....I investigated it and found that the package reached the American Express here and was sent by them to the Paris post office to be sent to St. Tropez and then and there it disappeared.” Still, however frustrated by what they have not received, exiles go on rising each morning to wait on the postman. Conceivably, though this would be most rare good luck, he may bring word of a revolution at home that has banished the banishers; much more likely would be the next best news he could hand them: the regime that condemned them to wander in foreign lands has fallen from power.

Political exiles have always tried to contribute to this end and perforce have worked through the mails. Herzen, Bakunin, and Kropotkin, for example, sought to undermine the Czar by sending their books, periodicals, manifestoes, and suggestions to their Russian confederates. In an essay “The Tragedy of the Political Exiles,” which appeared in the Nation on October 10, 1934, Emma Goldman pointed out that, no matter how great the suffering of these and other pre-World War I exiles, “they had their faith and their work to give them an outlet. They lived, dreamed, and labored incessantly for the liberation of their native lands. They could arouse public opinion in their place of refuge against the tyranny and oppression practiced in their country, and they were able to help their comrades in prison with large funds contributed by the workers and liberal elements in other parts of the world.” But the war for democracy and the rise of left and right dictatorships, she argued, had ended an era when rebels could find asylum in a number of countries and had relative freedom of movement: Now “tens of thousands of men, women, and children have been turned into modern Ahasueruses [Wandering Jews], forced to roam the earth, admitted nowhere. If they are fortunate enough to find asylum, it is nearly always for a short period only; they are always exposed to annoyance and chicanery, and their lives made a veritable hell.” Berkman was a leading case in point, though what she said applied to herself as well. Yet, utterly unwilling to accept this tragic turn of events, she kept at her “endless letters to America.” It was by no means a useless labor.

The endlessness of her correspondence was almost literal fact. Our guess is that she must have written some two hundred thousand letters, notes, postcards, and wires—all referred to here under the generic term letters—in her lifetime. [1] She could thus say with little exaggeration that friends had returned “veritable mountains of letters” for her to use in writing Living My Life (1931). Beginning in the 1920s, she multiplied their already awesome number by broadcasting carbon copies to a wide circle of correspondents. As she explained to novelist Evelyn Scott:

“I am delighted to know, dearest mine, you like my scheme of sending carbon copies of letters to my different friends. I began this method really to save labor because I find much typing sheer torture besides being a rotten typist. And now it has become a habit. I am glad to say most of my correspondents are enthusiastic about it....

“I have been hard at work making some order among my papers, mss., lecture notes, and letters. My dear, it was a job. You see, I am always so rushed while on tour to the last moment that I never can afford the time to put everything in order. I did it here [in St. Tropez]. Would you believe it, my correspondence alone would take about ten volumes. Sasha [Berkman] insists I’ll be punished good and hard when I come before my maker for having been such a prolific letter writer. I must say I find it infinitely easier to express myself in letters than in books. My thoughts come easier though not always worthwhile.”

In her reply Ms. Scott remarked on the colossal undertaking of sorting a correspondence which “must in itself constitute a marvelous record of radical thought in our age. Your letters are to me not only exceptionally fluent but stirring in those thoughts ‘worthwhile.’ I have wondered at your aversion to writing books when the written word, as your correspondence shows, is so easily at your command.”

Letters became Emma Goldman’s medium primarily because she was an exile and because in them the gap between the written and the spoken word was at its narrowest. A short stride over the gap enabled her to express her great strength as a speaker and conversationalist: It was as though she were responding to an earnest questioner after a lecture or having her say after a fine meal in someone’s apartment. She spoke with directness and intensity from the current edge of her thinking, feeling, experiencing—and not incidentally therewith effectively revoked the official edict of separation from all she held dear. This “proclivity to spread myself in letters,” for which she was chided by Berkman and others, meant that her distant friends had access to her continuous present and to her self-revelation of different aspects of character to different correspondents. Her letters gave them immediate data on how she was living her life and were in a sense invitations to live as much of it as they could with her. The end result made her seem, with the touch of irony detected by anarchist historian Max Nettlau, a figure out of an earlier letter-writing society: “In letters happily, though tiptop up to date otherwise,” he wrote in 1929, “you are eighteenth century, doing honor to the good old art of letter writing, which the wire and telephone have strangled, and this is a good thing, as a thoughtful way of communication by letters is an intellectual act of value of its own, which rapid talk, etc., cannot replace in its essence....”

In his still ridiculously neglected Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist (1912), Alexander Berkman had expressed acute psychological and political insights through a style of unusual simplicity and suppleness. As editor of Mother Earth, Emma Goldman’s monthly, and later of his own Blast, he went on to demonstrate that he was in some respects a more able, practiced writer than she. Yet his surviving correspondence, considered as a whole, is less impressive than hers and this rather surprising contrast calls for a few words of explanation. It was partly due to his temperament, which was less outgoing than Emma’s, and to the many years in prison, which fed his reluctance to reveal inner feelings even to intimate friends. Moreover, a man without a passport, repeatedly subject to deportation orders, and forever at the beck and call of the authorities, he was understandably less ready to disclose all in writing. In 1928 he wrote Emma, for instance, that he had destroyed a certain letter, adding: “I destroy most letters, except those on business or such as have reference to matters which might in the future serve as data etc. There are many deportations here now, and with some of those people my address might be found—the government has it anyhow, and so searches are always possible, and it is no use keeping personal letters.” Finally, Berkman was less vitally interested in expressing himself in letters than Emma, for he refused to consider ever returning to America. Now if the expatriate differs from the exile mainly in that he chooses not to go home again, Berkman became in this sense more the expatriate, while Emma’s yearning for repatriation marked her as always the exile. [2] Put more directly, letters to and from home meant less for him because home meant less.

But these distinctions have a way of becoming misleading when they become too tidy. In fact some of Berkman’s letters showed that he cared deeply what happened to his American correspondents and that he had not really relinquished all hope for the libertarian cause there. He was frequently stung by Emma into writing, if only in self-defense, eloquent and emotionally moving replies to her questions and arguments. Their letters indeed constitute a marvelous record of radical thought. Therein they noted their ongoing reflections on the repression and terror in post-Revolutionary Russia, the lot of exiles and refugees on the Continent, the reaction in England, the Sacco-Vanzetti case and other events in the United States, the rise to power of the Nazis in Germany, the appeal of dictatorship for the masses, and the like. Their continuing dialogue about things that mattered produced a “double, yet separate correspondence,” to borrow Samuel Richardson’s formulation, which was remarkable in its sweep and depth, frankness, and, not least, loving concern.

2.

One day this correspondence should be published in its entirety. Meanwhile its very richness presents special problems of selection: Why these particular letters and not others? Why not a greater or a lesser number? Should they appear in the usual chronological order? Or should we attempt to gather them into topical units? Our answers to these questions may be more readily understood if we explain how this volume came to be.

Over a decade ago the senior (in years) editor used the Berkman-Goldman letters as a framework for a biography of Emma Goldman. Their correspondence then posed some critically important questions: What was an appropriate response of Western radicals to the Soviet Union? Could anarchism cope with the problem of violence? How might men and women learn to establish decent relationships? And how might exiled revolutionaries live their beliefs? Stripping away the descriptive and analytical flesh from these questions as they appeared in the biography and using our notes as guides to the whole body of their correspondence, we retraced our steps to the archives and to those letters that had provided the skeleton of the earlier study. We then had the most important letters photocopied; from these four hundred and forty copies we later chose some as more significant than others, eliminated the latter, and cut some of the irrelevancies from the former. Our method has amounted to a kind of willful perversity, tantamount to the unwriting of a book, and can only be justified by the results: If we have carried out our editorial chores with a measure of success, the reader will find that the two sides of the correspondence collected here already constitute a biography of sorts, the lives of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman in their letters.

Collections of letters are usually strung on a simple chronological thread for good reason: By their nature such communications are hard to classify. Correspondents only occasionally discuss a single topic. Some letters contain passages on all the topics under consideration: Should they appear and, if so, where? Others obviously fit a particular category but contain passages on themes discussed elsewhere: Should these repetitions be cut? Even a selection of letters that are entirely of a piece may give a misleading view of the writer. Thus when Emerson edited some of Thoreau’s letters to demonstrate his friend’s “most perfect piece of stoicism,” Sophia Thoreau held the edition dishonest in that it contained none of her brother’s “tokens of natural affection.” Furthermore, excising these tokens destroys the unity of a letter; worse still, snippets can form a composite almost as lacking in fidelity as those redistributed passages of certain nineteenth-century editors. Nevertheless, recognizing these dangers, we still have chosen a topical organization for the five parts of Nowhere at Home, but have arranged the letters chronologically within each part—readers primarily concerned with chronology should not find it unbearably difficult to hop from part to part in pursuit of letters from a particular year or years. Happily some of their letters are almost completely given over to a theme; excerpts from others are usually direct responses to earlier queries or assertions and at all events are clearly identified as sections from particular letters. Excisions are always marked by the usual ellipsis dots. In Part Five, “Living the Revolution,” we have presented the reader with as many whole letters as space would allow: Especially there he or she can become acquainted with the relatively trivial, homely details of their everydays.

Emma spelled and typed atrociously and proved it once and for all by rendering the adverb as “atrotiously.” As she sat at her machine, parsnips came out “parsnaps,” cushions as “cussions,” trash as “thrash,” array as erray,” practical habitually appeared as “practicle,” and octopus even surfaced as “octiebus.” In 1931 she wrote Berkman about the irritating habits of a mutual friend, adding: “Of course I gave him a peace of my mind.” When the man apologized, “it was impossible to be angry with him though he certainly goes on one’s nerves.” The crisis of a feminine friend struck her as mere whim, knowing as she did “all these sexual obheavals of the American women.” In fact, the lives of these women were pitiably empty, she held, “and so they make a mountain of every little molehead.” Her typing was no less idiosyncratic. In 1925, for instance, she wrote Berkman a long letter from London, starting out by inserting her first page at an angle, so that the text leaned heavily over the right margin, and finishing by typing to the very bottom of the legal-sized sheet, whereupon her lines commenced an eerie diagonal course: “Look at this rotten crooked letter, will you?” she asked Berkman. “Try as I may I can never get it quite straight. There must be something crooked in my make up somewheres, don’t you XXX think?” And try as she might, the letters still “jomped.” In 1934 she responded to Berkman’s twitting with a wry plea for indulgence:

“Have a heart, dearest, old Pal. How can you be so cruel to tease me about my typing? Gawd knows I am already sickeningly conscious of it. What is more I think I am getting worse instead of better. This is the more inexplaninable because I am not so lacking in other respects. Except spelling. That is another strange complex. I suppose there is no help for me on this or the other world.”

To reproduce these vagaries of spelling, punctuation, spacing, and typography, all duly witnessed by swarms of sics, would be rank pedantry. We have therefore “normalized” spellings, mostly hers, corrected their obvious typographical errors, regularized punctuation, silently eliminated most abbreviations, and blocked and formalized their salutations and closes. Our overriding concern has been the interests and needs of the general reader, but we have not presumed to keep from him those idioms that are slightly awry. It strikes us as refreshing, anyhow, to imagine someone “making a mountain out of a molehead,” another wanting “to eat the pie and have it at the same time,” or to think of those pseudo-radical women who gave Emma “a pain in a soft spot.” American English was after all not their native tongue, as Emma’s spelling in a favorite saying forcibly reminds us: “Every little bit helps, said the old lady who pie pied in the sea.”

Marks and flaws in the photocopies we have had to use may have misled us on occasion. Still, we might have misread originals for the same reasons and did find onionskin carbons sometimes more readable when photocopied. No point would be served, in our opinion, by indicating in each instance whether our copy is of an original or of a carbon. As our acknowledgments indicate, all the letters or carbon copies we reproduce are at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. Doubtful passages and dates and incomplete letters are indicated by warnings in brackets or in the notes. To keep the latter at a minimum, we ask the reader to turn to the index for data, when known, on an unidentified individual on the first appearance of his name. In the headings appear the initials of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman; these are followed by the date and, when known, the place of writing. Thus: AB TO EG, December 20, 1933, NICE. Following the complimentary closes, finally, their initials in brackets indicate, in the absence of a note marking an incomplete original, that we are reproducing a carbon copy.

No doubt our choices among and from the letters of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman have not infrequently been misguided and sometimes simply unwise. But the reader may be certain of one thing: At no point did we feel obliged to keep from him those details “too intimate to publish.” If not for other reasons, it would have been too absurd to repress matters from lives dedicated to forthright expression. When Emma was preparing to write her autobiography in 1928, for instance, attorney Arthur Leonard Ross advised her to exclude her role in Berkman’s attempt to assassinate Henry Clay Frick:

“A bourgeois president of a bourgeois country could no more see in the story the humane promptings of a girlish heart than I can see Vesuvius from my office window....Should you entertain any illusions concerning your reentry into the Promised Land, remember that whatever vestige of hope there is will be dissipated by the publication of the story. Your guilt of complicity in a crime would be established against you pro confesso, and the actual purchase and delivery of the deadly weapon is the overt act.”

Emma’s reply merits quoting at length:

“Dear Arthur, I appreciate deeply your interest in my autobiography and in my chances of a possible return to the States. But it will be out of the question to consider your suggestion of eliminating the story....There are numbers of reasons why I could not possibly do that. The principal being that my connection with Berkman’s act and our relationship is the leitmotif of my forty years of life [since]. As a matter of fact it is the pivot around which my story is written. You are mistaken if you think that it was only “the humane promptings of a girlish heart” which impelled my desperate act contained in the story. It was my religiously devout belief that the end justifies all means. The end, then, was my ideal of human brotherhood. If I have undergone any change it is not in my ideal. It is more in the realization that a great end does not justify all means....

“After all, forty years have passed since that in tense and tragic event. I do not think that even the stupid 100% American government would hold this against me, especially as one of us has paid a price in blood and tears. But even if that should be the case, I would rather never again have the opportunity of returning than to eliminate what represents the very essence of my book.”

The final sixteen years of their relationship represents the very essence of this collection. As editors we have undertaken no less than to emulate their openness about its ups and downs.

3.

A short while ago a newspaper photograph showed a “draft dodger” in Toronto holding a biography of Emma before his face to hide his identity. The other day at a New York demonstration, the EMMA GOLDMAN BRIGADE of radical feminists marched boldly down Fifth Avenue behind a red-and-black banner bearing her name. In the spring of 1973 students at Hunter College organized a “Self Liberation Conference” to discuss Berkman and other anarchists, with music provided by the Death City Survivors. A few months ago two new editions of Berkman’s classic Prison Memoirs came out within weeks of each other. The issues of his Blast and of Emma’s Mother Earth were recently reprinted. Publishers have also brought out soft-cover editions of her Anarchism and Other Essays (orig. 1911), of My Disillusionment in Russia (orig. 1923, 1925), and of her autobiography Living My Life. What a columnist recently observed about Emma on the editorial page of the Washington Post (February 23, 1973) might also have been said of Berkman: “Her ideas of fifty years ago, bouncing back at us in history’s echo chamber, are in a language which has had to wait half a century for translation.” Why? And why their astonishing contemporaneity?

In those distant days of high patriotism and the Red Scare, when Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman were sent packing back past the Statue of Liberty, their strictures against the omnicompetent state struck all but a handful of libertarians as subversive foreign nonsense. Conservatives, liberals, and mainstream radicals were in perfect agreement on the need for centralization, unity, big nations. Herbert Hoover conservatives championed “rugged individualism,” but proceeded to build up the U.S. Department of Commerce and corporate bureaucracies. Franklin Roosevelt liberals expressed concern over civil liberties, but never wavered in their confidence that more agencies and more statutes, along with scientific management, would guarantee the freedom of individuals. And the Old Left, “progressive” by definition, also embraced integral nationalism and unrestrained industrialism, asking only that the managerial elites be staffed by socialists or communists. Everybody agreed that the good life could and would be achieved through the increased application of centrally directed technology. No one or almost no one proposed transcending the given reality or even suggested ways of asking the right questions about political and technological processes that were destroying the last possibilities of individuality and community. No one, left, right or center, in short, posed a compelling challenge to the nearly universal habit of reading history with centralist prejudices.

Yet as the twentieth century rolled on these yes-gentry cut ever more ridiculous figures: As though history were poking a little malicious fun at them for defying her processes, they were repeatedly let down by the “progress” they celebrated. The gas ovens, saturation bombing, Hiroshima, napalm, colonized minorities at home and colonial wars abroad all helped unmask centralist prejudices for what they were—apologies for systems of domination and repression. Man as Master (of many other men) used the nation state to slaughter more tens of millions of human beings: the war in Southeast Asia alone killed at last reckoning a million Indochinese and fifty thousand young Americans. With the publication of The Pentagon Papers, Americans learned that they had been consistently lied to about the origins of the war and that their leaders had almost certainly committed major war crimes. Meanwhile, Man as Conqueror (of nature) increased the Gross National Product by escalating his violations of the earth. The two processes converged in Vietnam with a destruction of lives and land justly labeled “ecocide.”

By the 1960s events themselves had thus helped translate the ideas of these two anarchists and gave them meaning for a generation in search of a politics of vision (and survival). Liberation movements of students, women, gays, and ethnic minorities produced an inchoate New Consciousness, a “counterculture” that could appreciate their pioneering struggles against war, racism, sexism, and injustice, and could draw on their example to carry out latter-day anarchistic experiments in radical journalism, forming communes, establishing free schools and clinics, homesteading; the communication over the generations was almost as direct as that suggested by the short step from the title of Emma’s Mother Earth to that of the ecology-minded Mother Earth News.

At the moment the best estimate of draft resisters and deserters still in exile is sixty to a hundred thousand; about ten thousand are in civil or military prisons, on probation, or facing court action; and another eighty thousand are “underground” in America. These exiles, abroad and at home, and their families are very much on our minds as we edit these letters, as the dedication above suggests, for the prison experiences and the exile years of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman speak directly over the decades to the like circumstances of a large number of courageous men and women. Those who take up this volume, along with other general readers, should find their own hard times eased a little. Those who seek to continue their resistance with deepened understanding, patience, and love will find sustenance here.

By the 1970s surface manifestations suggested that the original energy of the New Consciousness had been pretty well played out, although divisions within American society remained deep and it was still too early to tell whether the preceding decade was one of those turning points “at which history fails to turn,” as Louis Namier said of the 1840s. If it does not come round, the fault will not all lie with the young and not so young in what once seemed truly “the movement.” Only now as we write, in the wake of the Watergate disclosures, is it clear how serious a threat the counterculture has seemed to those who wield power. Even the most knowledgeable activist, keenly aware that the atmosphere of radical groups had been poisoned by snooping, suspicion, and official harassment, would never have suspected that electronic buggers and old-fashioned burglars were operating out of the White House to deny justice to radical defendants, discredit dissent, stifle the New Consciousness. Even less would anyone have thought that the late J. Edgar Hoover, who more than any other person was responsible for the deportation of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, would have acted to restrain this high-level criminality by becoming a blackmailer for justice—and the FBI. Concerned with the vulnerability of his Bureau, Hoover, according to his one-time chief assistant, William Sullivan, threatened to reveal a file of illegal phone-tap records if his superiors in the Republican Administration persisted in ordering such flagrant “dirty tricks”: “That fellow was a master blackmailer,” declared Sullivan, “and did it with considerable finesse despite the deterioration of his mind” (London Times, May 16, 1973). So apparently was freedom fought for and partially preserved in our modern state.

But no small part of all this scum atop official waters would have surprised Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, which truth argues powerfully that, with these letters from exile, they have come home again none too soon.

Richard and Anna Maria Drinnon

S.S. Eurybates

North Atlantic

May-June 1973

Notes for Introduction

1. Dan H. Laurence, Bernard Shaw’s editor, estimates that the playwright wrote a quarter of a million letters. Emma must have written almost as many, though a large number of course were lost or destroyed or confiscated—much of her correspondence to 1917, for instance, was scooped up by federal raiders and carried behind the walls of the U.S. Department of Justice. For a discussion of those papers that survived and came to rest in various archives, see the “Bibliographical Essay” in Richard Drinnon, Rebel in Paradise: A Biography of Emma Goldman (New York: Bantam Books, 1973).

2. Mary McCarthy argues persuasively for this distinction in “A Guide to Exiles, Expatriates, and Internal Emigres,” New York Review of Books, XVIII (March 9, 1972), 4–8.

To 1919: Autobiographical Fragment and Chronology

Of primary importance in his own right, Alexander Berkman has long merited a full-scale biography. The lack of one leaves a big hole in our understanding of modern radicalism and contributes to the regrettable tendency to see him as a mere adjunct to his more ebullient comrade. His prison memoirs go a good way toward righting the imbalance, but they carry the reader only a little beyond 1906. Berkman figures prominently in Emma Goldman’s autobiography and in biographies of her, of course, but in none of these works is he put at center stage.

In July 1930 Berkman had himself moved to meet the need in a prospectus of “a book I have in mind. Its title is to be: I Had to Leave. It will be autobiographical, perhaps held in a light and humorous vein, and will deal with the situations in my life when ‘I had to leave.’ Thus, as a mere youth, I had to leave Russia, because of a disagreement with my rich uncle and also to avoid forced military service. I had, later on, to leave on many occasions.” That he did, from an imposing list of countries, but he did not sit down to detail the circumstances. By November 1932 he had only a seven-page “rough outline” of an autobiography for which he then proposed the ironic title An Enemy of Society. Unhappily this too remained unwritten.

His outline to 1919 appears here in belated recognition of the life that might have been and as a convenient way to give the reader a sense of the flow of people and events in it down to the American Deportations Delirium. It is followed by a very brief chronology of Emma Goldman’s life during the same period, which order, for at least this once, gives Berkman top billing.

Autobiography of Alexander Berkman (Rough Outline)

Early Days: [b. November 21, 1870; Wilno.] Life at home and at school in St. Petersburg. My bourgeois father and aristocratic mother. Jews and Gentiles. I question my father about the Turkish prisoners of war begging alms in the streets.

Our Family Skeleton: Strange rumors about my mother and her brother Maxim. Echoes of the Polish rebellion of 1863. I hear of the dreaded Nihilists and revolution.

A Terrified Household: A bomb explodes as I recite my lesson in school [March 1881]. The assassination of Czar Alexander II. Secret groups in our class. Police search our house. Uncle Maxim is arrested for conspiring against the Czar’s life. The funeral of the dead Czar. A terrorized city.

Family Troubles: Rumors of my beloved Uncle Maxim’s execution. My terrible grief. Death of my father [ca. 1882]. We lose the right of residing in the capital. Race prejudice and discrimination. Breaking up our business [the wholesale of “uppers”—the upper leather part of shoes] and home.

Provincial Russia: The Ghetto. Life in Wilno and Kovno. My sister Sonya and my two elder brothers. In school and university. My rich Uncle Nathan [Natansohn]—dictator of Kovno. His peculiar family.

The Troubles of Youth: Class distinctions in school and at home. I am forbidden to associate with menials. Our warring school gangs on the River Niemen. Boys and girls—the mysteries of sex. Visiting university students initiate me into Nihilism. Secret associations and forbidden books.

My First Rebellion: I defy my rich Uncle Nathan and defend a servant girl against my mother. Punished in school for my essay, “There Is No God,” written when I was thirteen years old [1883]. Chumming with a factory boy and teaching him to read. I discover capitalism. I worship my martyred Uncle Maxim.

Planning an Escape: I learn that Uncle Maxim [Natansohn, his mother Yetta’s brother, later head of the Executive Committee of the Social Revolutionist Party, and affectionately known on the Russian Left as “The Old Man”] is alive and has escaped from Siberia. My brother Max is refused admission to the universities, because he is a Jew. My violent indignation. More trouble at school. Max preparing to enter a German university. I conspire to accompany him. A narrow escape in stealing our way across the border. I go to Hamburg. Traveling steerage to America.

In Free America: [From February 1888.] Life on the East Side of New York. A new-fledged workingman at seventeen. The troubles of a greenhorn. I find friends and a sweetheart. Wealth and poverty. I meet Russian political exiles and frequent revolutionary groups in New York. I join the anarchists. Echoes of the Chicago Haymarket affair.

The World of Labor: Factories and machines. I work as cigarmaker and cloak-operator. Friends and enemies. East-Side cafes and meetings. The great proletariat. The troubles of an immigrant. Prominent revolutionaries.

Reality versus Idealism: Life and struggle. Devotion to my ideals. My intimate comrades and our first “commune colony.” Planning to return to Russia for revolutionary work. Johan Most and the German anarchist movement in America. My friends Emma Goldman and Fedya [Modest Stein]. Love, friendship, and revolution.

The Homestead Strike: The steelworkers of Pennsylvania. Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick. The bloodbath on the Monongahela [1892]. Carnegie and his hired Pinkertons. The whole country shocked. I decide to go to Homestead. Carnegie escapes to his castle in Scotland. My attempt on the life of Frick. The travesty of my trial. I am sentenced to twenty-two years’ prison.

In the Penitentiary: Life in prison [1892–1906]. Guards and convicts. I organize a strike for better food and treatment. Am sentenced to the dungeon. Prison torture. Attempting suicide and escape. I spend ten years in solitary confinement. The grist of the prison-mill. Types of prisoners. Stories of crimes. Robbing the stomach. Fake prison investigations. My prison chums. Love and sex in prison.

My Resurrection: Freedom after fourteen years in prison [May 18, 1906]. The shocks of reality. Great expectations and crushing disillusionment. How the world had changed. Old-time friends and new actualities. Afraid of meeting people. My first lecture tour. I am in Frick’s stronghold again. A visit to Homestead. I disappear: [friends fear I am] either dead or kidnapped by Frick.

My New Lease on Life: Police brutality and the arrest of my comrades. I am roused to work and fight. The labor and new revolutionary movement. Russian political refugees: echoes of the Russian revolution of 1905. My new activities. I start a cooperative printing shop. The “Americanized” East Side. Labor leaders, socialists, IWW, bundists, and anarchists.

Some More Trouble: A mass meeting in Cooper Union. I object to a speaker’s remarks and am railroaded to Blackwell’s Island. I am editor of Mother Earth, Emma Goldman’s anarchist publication [1908–15]. Trouble with [Anthony] Comstock. Illiberal American liberals and muddle-headed radicals. I organize the first Anarchist Federation in America. Trouble with the police. Free-speech fights.

Struggles of Labor: The beginning of American imperialism and my first anti-war work. The Industrial Workers of the World and the American Federation of Labor. Outstanding personalities. I help to found the Francisco Ferrer Association for libertarian education. My new role as radical Sunday-school teacher. I write my prison memoirs [1912]. The unemployed movement; taking possession of churches [winter 1913–14]. The Ludlow (Colorado) massacre; strikes and great labor trials. Big Bill Haywood, [Morris] Hillquit, Emma Goldman, Margaret Sanger, [Elizabeth] Gurley Flynn, [Carlo] Tresca, and other personalities. The Union Square tragedy. I defend the McNamara brothers [John J. & James B.]. The Los Angeles Times explosion [1911]. General [Harrison Grey] Otis. Mother Jones and martial law. Clarence Darrow gets acquitted and convicts the McNamara brothers, his clients. Golden-rule Lincoln Steffens is double-crossed at his own game. We fight it out with the police at Union Square. I lead the siege of Tarrytown, home of [John D.] Rockefeller. The inside story of some explosions. I am charged with inciting to riot and face prison again.

On the Coast: A lecture tour across the country [1915]. The Mexican revolutionists in California. I meet a descendant of the Aztecs. The Blast, my revolutionary labor paper in San Francisco [1916]. Persecution by the Catholic Church. The Mexican Revolution. The Blast editorial: “Wilson or Villa—which the greater bandit?” The Blast suppressed, but continues to circulate. The American war hysteria. The Preparedness Parade bomb explosion in San Francisco [July 22, 1916]. The arrest of Tom Mooney, [Warren] Billings, and other labor men. I organize their defense. The conspiracy against Mooney. Fremont Older and the labor leaders assure me Mooney is guilty. I tour the country in his behalf and work for Mooney in New York.

The War: America enters the War [April 1917]. Jingo Quakers and radicals. The No-War campaign and my fight against conscription. Exciting mass meetings. I break my leg and talk on crutches. Defying police and soldiers. The Revolution breaks out in Russia and I plan to go there. I am arrested for obstructing the draft [June 15, 1917]. In the Tombs. California demands my extradition in connection with the Mooney case. The Kronstadt (Russia) sailors threaten the life of the American Ambassador [David] Francis in case I am extradited to California. [Woodrow] Wilson sends a confidential messenger (Colonel [Edward M.] House) to the governor of New York. The governor refuses to extradite me. My trial for “conspiracy to obstruct the draft.”

The Atlanta Penitentiary: Two years in the Georgia State [U.S.] prison [1917–19]. “Politicals worse than criminals.” Conscientious objectors and Eugene V. Debs. Our chain-gang warden. I protest against an officer shooting a Negro convict in the back and killing him. Punished in the dungeon and solitary for the rest of my time. [Liberated, October 1, 1919.]

Emma Goldman Chronology

Birth, Kovno (Kaunas in modern Lithuania), June 27, 1869. Girlhood and adolescence, Kovno, Popelan, Konigsberg, and St. Petersburg, 1869–85. Migration to the United States, 1885. Factory worker, Rochester and New Haven, 1886–89. Marriage to Jacob Kersner, 1887. Divorce, 1888. Joined anarchists in New York City, August 15, 1889.

First speaking tour, 1890. Complicity in Berkman’s attempt to kill Frick, 1892. Union Square speech and arrest for inciting to riot, August 1893. Prison on Blackwell’s Island, 1893-August 1894. Nurse’s training, Vienna, 1895–96. Official attempts to implicate her in the assassination of President McKinley, 1901. Midwife and nurse on the East Side, 1901–05. Publisher-editor of Mother Earth, 1906–17. Delegate to the Amsterdam Anarchist Congress, 1907. Chicago free-speech fight, 1908. New York free-speech fight, 1909. University of Wisconsin free-speech fight, 1910. Published her Anarchism and Other Essays, 1911.

San Diego free-speech fight, 1912–15. Wrote The Social Significance of the Modern Drama, 1914. Birth-control lectures, 1915–16. Arrest in New York for her lecture “on a medical question,” February 1916. Fifteen days in the Queens County Jail, April-May 1916. Mooney defense, 1916. Organized the No-Conscription League, May 1917. Arrested with Berkman for “conspiracy to induce persons not to register,” June 15, 1917. Trial, June 27-July 9,1917. Missouri State Prison (Jefferson City), 1918. Celebrated her fiftieth birthday in her cell, June 27, 1919. Liberated, September 28, 1919.

Part 1: Cast Out

“Deportation: First deportation of politicals from the United States [December 21, 1919]. The hell of Ellis Island and our kidnapping in the dead of night. The leaky boat “Buford” and its passengers. A near-mutiny. Sailors and soldiers offer to turn the ship over to me. The “sealed orders of the captain.” We make demands and gain them. In danger of landing in the country of the Whites. Traveling in Finland under military convoy. Finnish soldiers steal our provisions. Crossing the border [into Russia, January 18, 1920].”

—Alexander Berkman, An Enemy of Society

In his Flag Day Address of June 14, 1917, President Wilson pledged “woe to the man or group of men that seeks to stand in our way in this day of high resolution.” Woe was already stalking the footsteps of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman for their refusal to share in this high moral resolution and for their taking the lead in opposing the draft. On the following day, June 15, they were arrested and on July 9, at the conclusion of their trial, they were sentenced to two years in prison and fined ten thousand dollars each. The prison letters that follow were written toward the tail end of their terms, well after the Armistice had been signed, and after the reaction had set in.

Berkman did hard time, in part because of his protest against a guard’s wanton murder of a black convict. He survived an extended bread-and-water diet in the tomb-like Hole only to spend the last seven and a half months of his sentence in solitary and isolation. The brittle tone of his letters, their obscure allusions and cryptic references to individuals, some of whom remain unidentified, reflect his circumstances and his desire to thwart prison censorship. None of his letters to Emma or of hers to him survive from this period, for they were both involuntary guests of Uncle Sam and forbidden to write each other. M. Eleanor Fitzgerald, or Fitzie, Berkman’s companion and their co-worker, did smuggle a note out of Atlanta for Emma, but it has disappeared. As you will see, however, Berkman was very much on Emma’s mind: Her letters repeatedly voiced her concern over “our boy in the South.”

By contrast Emma did good time, although she was experiencing the menopause, found the “task” in the prison sewing shop exhausting, and throughout was tormented by the helplessness and hopelessness of her sister inmates. Kate Richards O’Hare was a leading socialist, close associate of Eugene V. Debs, and war opponent also convicted of violating the Espionage Act. Her arrival and that of young Ella Antolini, another “political,” made time pass more quickly. Ellen Kennan was a former Denver school teacher. Stella Cominsky was the daughter of Emma’s half-sister Lena, a favorite niece, and the companion of the Shakespearean actor and painter, Teddy Ballantine, whom she later married.

Both emerged from prison with their spirits unbroken, although Berkman’s health was shattered. It is worth noting that at his deportation hearing in Atlanta and at Emma’s later in New York, one of the officials in attendance was J. Edgar Hoover, who was handling their cases for the Department of Justice. Their individual statements on the hearings cut to the heart of their quarrel with American officialdom. Finally, their open letter (“Dear friends”) on the eve of being cast out expressed their hopes and fears: Their spunky, if not cocky, “we are of the glowing future,” was counterbalanced by the rather grim vow: “Our work will go on to the last breath.”

EG TO ELLEN KENNAN, July 24, 1919, JEFFERSON CITY

Ellen dearest,

...Thank you, dear, for your beautiful birthday letter. Yes, I think a number of people thought of me that day. Quite a few sent letters, telegrams, flowers, and many other gifts. I felt quite important on that day, though I was really ill in my cell and had as my next cell-door neighbor a sick lady. For a time Kate O’Hare was very ill, but she seems to have recuperated and is now feeling as well as one can in prison. Among the many things which came, though not as a birthday gift, and later, were two large bunches of roses—all the way from Moscow. Not really the roses, but the money for them. Bill Shatov [old friend and co-worker], of whom you have undoubtedly heard, sent money to a friend in Paris and he in turn gave it to Mary [Heaton Vorse] O’Brien who was there at the time. She gave it to Stella and in that way the beautiful roses reached me. More beautiful however is the spirit which prompted the gift. Think of it, our friends in Russia who are in death’s grip with the blackest reaction that has ever conspired against the efforts of the people, yet they have time to think of us here, and of our small vices among which my love for flowers is by no means the least. Anyway, the three politicals in this institution, Kate, Ella [Antolini], and myself, enjoyed the gift and the spirit. Kate still has some of the ferns that came with the roses; they seem to symbolize the spirit of Russia which cannot be daunted. The ferns, though in the stuffy cell for nearly two weeks, are still fresh. They are just like the plant which Big Ben [Reitman] sent me for Christmas, indestructible.

I have a bit of good news for you and all of our New York friends. Kate was seen yesterday by a man from Washington who questioned her about her stand, should she be granted a pardon. He was anxious to know whether she would make a demonstration in case a pardon was not extended to the other political prisoners. He wanted her to make other promises as to what she would do when she is released, which of course she refused, but she did say that she would make no demonstration. No doubt she feels that she can do that much better once she is out; in fact she said as much to the man, that she will never rest until all politicals are freed. From the foregoing you will see that Washington is very anxious to get rid of Kate and Debs—I understand RPS [Rose Paster Stokes?] is also included. Wouldn’t that be wonderful! I shall now perhaps not need to worry about leaving Kate behind; it would have been terribly hard for me, as you can well imagine. Now we expect that she may go almost any day. I rejoice even though the rest of my time will be very dismal. You will possibly know as soon as we when the pardon is granted, as the papers will be sure to feature it.

I don’t know whether you saw Fitzie lately and whether you know what a frightful time our boy in the South [AB] is having. The latest is that he will lose five days of his time. Can you imagine a greater cruelty? For months now he has been in solitary confinement, denied all privileges until very recently when he was granted them only partially. He is not allowed to go to the movie, get any kind of decent reading matter, or have sufficient exercise. You can imagine how heavily time must hang on his hands, and now he will have to remain in that hideous place an additional five days; it is exasperating. How weak and insecure must our mighty government feel, if it must stoop to such petty persecution. How futile its effect on a spirit like our boy’s, even though his condition is so galling at the present time. The girls sent me copies of his letters; they are simply wonderful, more wonderful because they come from a man who has spent the best years of his life in prison. Yet his fire and faith are unquenchable....

I think of you a great deal, Ellen dearest; coming into my life has been a great event. I am not in a position to make plans for the future, but if I remain in New York, I should love to take an apartment with you. How does this strike you? Of course I shall be with Stella at first, but I will have to have a place of my own. Having been used to a private room for nineteen months, it will not be easy for me to live where there are many people. But two such maiden ladies as you and I could manage harmoniously together, don’t you think? No dear, I am not getting the Call. I don’t know why; fortunately Kate is and it is all right as long as she is here. With a fond embrace and much love,

EG

P.S. Dearest, enclosed is a $1 bill for which you’re to get me two crepe de chine ties; buy two ties. One in Alice blue or some other nice blue—not too light. The other in a rich yellow.

EG TO STELLA COMINSKY, August 30, 1919, JEFFERSON CITY

Dearest,

I began this letter last night but had to give it up. I worked dreadfully hard all day yesterday, so as not to have to go down this morning. Then, when I got to my cell, I was all in. I have not been feeling very well this week. I think it is the change of weather. It has turned cool suddenly and rained nearly all week. So my old bones are rattling again. As a matter of fact, I have been exceptionally well these last two months—better than at any time during my stay here. I ascribe it to my being able to stay out of the shop on Saturdays—and even more so to our weekly picnics. Four hours in the open each week with the chance of moving about a bit makes all the difference in the world. It is only this week that I have been aching all over but I kept at work. I don’t want to go before the doctor again, if I can help it. Of course, I know that it never was Dr. McNearney who ordered us to the shop that time on threat of being put on punishment for forty-eight hours. But if I can manage without seeing him, I will be satisfied. In any event you need not worry; it is really nothing at all.

Well, dearest, I have already done four of my thirty days for kind Uncle Sam [in payment of the $10,000 fine]. If brother [Judge Julius] Mayer had not honored us—AB and I would now be free. But we ought to be grateful to that Prussian of Prussians for the honor bestowed upon us—he has demonstrated our value far beyond [what] my best friends could have done. Twenty-six days longer—really less than that because the days you will be here will hardly count. I am sure Mr. P. [Warden William R. Painter] will let you see me. I don’t see why he would want to make exceptions when he has been so generous about visits all the time. I only wish more friends could have come. But it is well you wrote him. And about Addie [an inmate] too, you must let me know directly you hear from him.

Funny, it never occurred to me to let you know why Addie is here. For murder, dearest; I don’t know the details of the case. I never asked. I wish I had Kate’s capacity to ferret out things. She knows the history of every woman in this place. Not for the life of me can I ask anyone about the thing which brought her here. To me it is more than terrible that she is here. Then, too, I know that if she were not poor and friendless, she would most likely not be here. In all the nineteen months, not one woman of means was brought here. Yet I know that many have committed the offense and possibly graver ones than Addie or any other. But you will be amused at the conception of propriety on the part of my fellow comrades. When I told Addie that some of our friends wanted to know what she is here for, she said “I don’t blame ‘em, they might think I am here for stealing or using dope.” You see, from Addie’s point of honor, murder is a higher crime than stealing or using dope. Yet the outside world thinks the so-called criminal without any conception of ethics. I am not able ever to see the difference between the outside and the inside world. They are both equally small and equally big according to the point of view. I don’t believe Addie will be paroled to you. But at least the girl will know we have tried. I cannot make out the judgment used in paroling prisoners. This week three women have been paroled. Two have been here only half the time of Addie and have not worked as hard as she. The third one is about to become a mother, so there is sense in her parole. Of course, as far as I am concerned all the prisoners should be let go—it would be better for society and more beneficial to those who watch over them. More than ever I am convinced that, next to the outrage of locking people away where they are degraded to the condition of inanimate matter, is the outrage of condemning people to be their jailers and keepers. The best of them gradually grow hard and inhuman or they do not keep their jobs very long.

Yesterday I made out my application blank for discharge. The [U.S.] Commissioner will now have plenty of time to “look into the matter.” As I wrote you last week, I will be expected to give proofs of my inability to pay the fine. I suppose when H[arry] W[einberger] gets back to town he will go after [Bolton] Hall, [Gilbert E.] Roe, and a few others for affidavits. I may have to swear to an affidavit myself which I am perfectly willing to do. Mr. P[ainter] will let me know in time. About AB’s bond, I understood that [Charney] Vladek had made some arrangements last year when he was out to see the boy. I will write Harry Weinberger Sunday and Fitzie Tuesday to see about the matter at once. I should say the bond must be ready—it would be awful to let the boy [AB] be dragged off to the rotten jail after his terrible time in solitary. And, dearest, my bond too will have to be ready. The 27th is a Saturday—unless the bond is all prepared, I will be kept in jail over Sunday and you will have to stick around the two extra days. That can easily be avoided, if you come prepared. The trouble is, we will not know how much bond will be required. I wonder if Harry Weinberger could get a line on that. I will write him. And whom do you have in mind about bond? Would Jessie [Ashley’s] sister go my bond? She has means of her own and must also have gotten all of Jessie’s property. How strange all our wealthy radicals are—the most generous among them never leave anything for the work they so love during their lifetime. Perhaps I should not say that about Jessie—I don’t know what provisions she has left. But all the others I have known never left a red cent to the work. Let me know whom you mean to approach about the bond. Anyway, dearest, you must come all ready....

I have asked Miss S [Lilah Smith?], to see if she can get me a sailor or little soft felt traveling hat in town. She is going either today or Monday, so I will be able to let you know whether it will be necessary to get one in Rochester. If Miss S can find the kind I want, she will have several sent out here for me to try them on. You know how hard it is to fit me in hats. My head may have been made for the block but it is not fit for a hat. Then the gloves, I would prefer to have them from Altman’s or Constable’s, at least they have some with stubby fingers like mine. I will ask Fitzie to get me a pair and send them out direct to me. I have decided to get black gloves, as the others soil too much in traveling. While you are in Rochester get me a nice soft roching [lawn linen] for the wrists of my black dress and have your mother sew it in. Bennie [Capes] is sending me some collars of which you get one. Dear Bennie, it was such a joy to see him again. He was so disappointed not to be able to see little Ella [Antolini]. But Mr. Painter would not let him see her. He wrote Bennie he could not see what interest he has in her. Of course, Mr. P does not know that community of ideas with us often means more than community of blood. I am going to speak with Mr. P before I leave to let Bennie see Ella when I am gone. He comes through here so often and the child has no one to see her and still will have five months. By the way, dearie, do not forget Ella’s birthday—the flowers. I think you better have the florist send her a little plant with some red flowers. It will keep longer. And did you write Ellen K[ennan] to get me a red crepe kimono for her? Bennie will also send her something. At least the child will have a few tokens of love, even if she meets her twentieth birthday in prison....

Devotedly, EG

P.S. Kiss the kid [Ian] for me. Thank [Eugene] O’Neill for the volume of plays. Write Butler Davenport again. Received [the] large box of apples; all the girls enjoyed [them].

AB TO M. ELEANOR FITZGERALD, September 7, 1919, ATLANTA

Well, dear woman,

You see I’m back to my old letterhead. This means that hereafter I may write every week, though I remain in solitary, as before. It’s three weeks, and three days—twenty-three days, not counting today which is already half gone: It is 1 P.M. Who said there are only twenty-four hours in a day—and night? That may be true of March and April and such months, but not of August and September. Of course, I have no work to do—that makes it worse, and I’ve had to cut out a good deal of my reading on account of my eyes. So that Old Father Time seems to me mightly slow of late—but it isn’t long now, and I guess I’ll have to be patient with the Old Man. You all speak—Stella and Kal also—of a few weeks’ vacation in that wonder spot on the [Cape] Cod, but it seems to me a daydream. Well, we’ll see. I confess I’d enjoy it, though: these two years, and especially the last six months, have been hard. I’m afraid I’m not as young as I used to be—in Allegheny, for instance. I’ll be thirty-three years in November, or forty-nine if you want to count the sixteen years I didn’t live. The beautiful rose “kissed by Minnie [Fishman]” (no one else? safety first) came yesterday with your letter, dear. It was a kind of lifesaver—a needed change from the postal-card diet. That isn’t quite fair, though, for I had four very good letters from you, besides six postals, counting since my last letter of August 24. Also good letters from Pol and Stella. I’ve been wondering what’s become of Minna [Lowensohn] and all the others. And by the way, what about Dr. [Michael] Cohn’s letter? I did not receive it. Her visit home did not do Gertrude [Nafe] much good. Upon her return she sent me a letter, signing herself “yours respectfully”! And Lilly Kisliuk addressed her postal to me at Jefferson City. You are back now in New York and I suppose already in full harness. I wish you could have stayed in P[rovincetown]. Pol says it’s such a beautiful place; it’s easy to be literary there. And I notice her own letters are assuming that character....My little niece refers to that marriage of convenience as if I knew all about it. But I don’t. Edwina hinted, but I didn’t want to talk about it, at that time. Such marriages have often proved happy. I hope it isn’t too late, though. Some remarks I made in a previous letter referred to a different phase of the matter. And dear LD [Lavina Dock?] thinks the radicals get it in the neck, etc. And that “the radical gesture is defeated almost always on the practical plane.” We all—everything living—finally “get it in the neck.” The ultimate goal is six feet of clay, but I’d rather die the victim of my faith then live the dupe of vain self-aggrandizement or ambition. It’s all in the point of view. I do not think we get it in the neck, except as individuals; as idealists we always win; yes, on the practical plane. Huss dies to give birth to Luther and to triumph with him. And Sophia Perovskaya conquers in [Mme Alexandra] Kolontay. I hold that ultimately it’s the ideal that conquers, and having conquered, it mounts to still higher and further visions. As to the individual—he is the stepping stone of man’s progress, but remember there are times when the most elevated place in the world is a scaffold. Dear woman, have you profited by your vacation? It was too short. Are you about to send my things? It’s nearly time. If you answer this promptly, I’d get your letter just before I write again. And now, so long, dear. It seems so near already, but who knows? Yet you may depend on it, I shall be equal to any emergency. Do you mean to meet me anywhere on the road? Dear Kal must be counting the minutes of our meeting. So am I. Where shall we twain meet again? If perchance in hades, I’ll call a strike of the firemen and stokers.

Much love,

AB

STATEMENT BY ALEXANDER BERKMAN IN RE DEPORTATION

Made to the officials of the U.S. Federal Immigration Service at the Federal Penitentiary, Atlanta, Georgia

September 18, 1919

The purpose of the present hearing is to determine my “attitude of mind.” It does not, admittedly, concern itself with my actions, past or present. It is purely an inquiry into my views and opinions.

I deny the right of anyone—individually or collectively—to set up an inquisition of thought. Thought is, or should be, free. My social views and political opinions are my personal concern. I owe no one responsibility for them. Responsibility begins only with the effects of thought expressed in action. Not before. Free thought, necessarily involving freedom of speech and press, I may tersely define thus: no opinion a law—no opinion a crime. For the government to attempt to control thought, to prescribe certain opinions or proscribe others, is the height of despotism.

This proposed hearing is an invasion of my conscience. I therefore refuse, most emphatically, to participate in it.

ALEXANDER BERKMAN

STATEMENT BY EMMA GOLDMAN AT THE FEDERAL HEARING IN RE DEPORTATION

New York, October 27, 1919

At the very outset of this hearing I wish to register my protest against these star-chamber proceedings, whose very spirit is nothing less than a revival of the ancient days of the Spanish Inquisition or the more recently defunct Third Degree system of Czarist Russia.

This star-chamber hearing is, furthermore, a denial of the insistent claim on the part of the government that in this country we have free speech and a free press, and that every offender against the law—even the lowliest of men—is entitled to his day in open court, and to be heard and judged by a jury of his peers.

If the present proceedings are for the purpose of proving some alleged offense committed by me, some evil or anti-social act, then I protest against the secrecy and third-degree methods of this so-called “trial.” But if I am not charged with any specific offense or act, if—as I have reason to believe—this is purely an inquiry into my social and political opinions, then I protest still more vigorously against these proceedings, as utterly tyrannical and diametrically opposed to the fundamental guarantees of a true democracy.

Every human being is entitled to hold any opinion that appeals to her or him without making herself or himself liable to persecution. Ever since I have been in this country—and I have lived here practically all my life—it has been dinned into my ears that under the institutions of this alleged democracy one is entirely free to think and feel as he pleases. What becomes of this sacred guarantee of freedom of thought and conscience when persons are being persecuted and driven out for the very motives and purposes for which the pioneers who built up this country laid down their lives?

And what is the object of this star-chamber proceeding, that is admittedly based on the so-called anti-anarchist law [of 1903]? Is not the only purpose of this law, and of the deportations en masse, to suppress every symptom of popular discontent now manifesting itself through this country, as well as in all the European lands? It requires no great prophetic gift to foresee that this new governmental policy of deportation is but the first step toward the introduction into this country of the old Russian system of exile for the high treason of entertaining new ideas of social life and industrial reconstruction. Today so-called aliens are deported; tomorrow native Americans will be banished. Already some patrioteers are suggesting that native American sons, to whom democracy is not a sham but a sacred ideal, should be exiled. To be sure, America does not yet possess a suitable place like Siberia to which her exiled sons might be sent, but since she has begun to acquire colonial possessions, in contradiction of the principles she stood for for over a century, it will not be difficult to find an American Siberia once the precedent of banishment is established....

Under the mask of the same anti-anarchist law every criticism of a corrupt administration, every attack on governmental abuse, every manifestation of sympathy with the struggle of another country in the pangs of a new birth—in short, every free expression of untrammeled thought may be suppressed utterly, without even the semblance of an unprejudiced hearing or a fair trial. It is for these reasons, chiefly, that I strenuously protest against this despotic law and its star-chamber methods of procedure. I protest against the whole spirit underlying it—the spirit of an irresponsible hysteria, the result of the terrible war, and of the evil tendencies of bigotry and persecution and violence which are the epilogue of five years of bloodshed....

EMMA GOLDMAN

EG AND AB TO DEAR FRIENDS, December 19, 1919, ELLIS ISLAND

Dear, dear friends,

We have been told this afternoon that we must get ready as we may be shipped any moment. This, then, is our last chance to speak to you once more while still on American soil. Most of what we have to say about the black reaction now rampant in this land and the urgent need of concerted action to stem the tide, you will find in our last message to the American people—the pamphlet on deportation, written by us while here, and now in the hands of the printer. To you, dear, faithful friends, we want to send a parting word.

Do not be sad about our forced departure. Rather rejoice with us that our common enemies, prompted by fear and stupidity, have resorted to this mad act of driving political refugees out of the land. This act must ultimately lead to the undoing of the madmen themselves. For now the American people will see more clearly than our ardent work of thirty years could prove to them, that liberty in America has been sold into bondage, that justice has been outraged, and life made cheap and ugly.

We have great faith in the American people. We know that once the truth is borne in upon them what the masters have made [of] this once promising land, the people will rise to the situation. With Samson strength they will pull down the rotten structure of the capitalist regime. Confident in this, we leave with joy in our hearts. We go strengthened by our conviction that America will free herself not merely from the sham of paper guarantees, but in a fundamental sense, in her economic, social, and spiritual life.

Dear friends, it is an old truism which most of you have surely experienced: He who ascends to the greatest heights of faith is often hurled into the depths of doubt. We have known the ecstasy of the one and the torture of the other. If we have not despaired utterly, it is because of the boundless love and devotion of our friends. That has been our sustaining, our inspiring power. Few fighters in the struggle for human freedom have known such beautiful comradeship. If we have been among the most hated, reviled, and persecuted, we have also been the most beloved. What greater tribute to one’s integrity can one wish?

As in the past, so now in this our last struggle on American soil, your love, your splendid devotion, your generous gifts, are our strength and encouragement. We feel too intensely to express our gratitude in words. We can only say that our physical separation can have no effect on our appreciation of your loyalty—it can only enhance it.

We do not know where the forces of reaction will land us. But wherever we shall be, our work will go on until our last breath. May you, too, continue your efforts. These are trying but wonderful times. Clear heads and brave hearts were never more needed. There is great work to do. May each one of you give the best that is in him to the great struggle, the last struggle between liberty and bondage, between well-being and poverty, between beauty and ugliness.