CrimethInc.

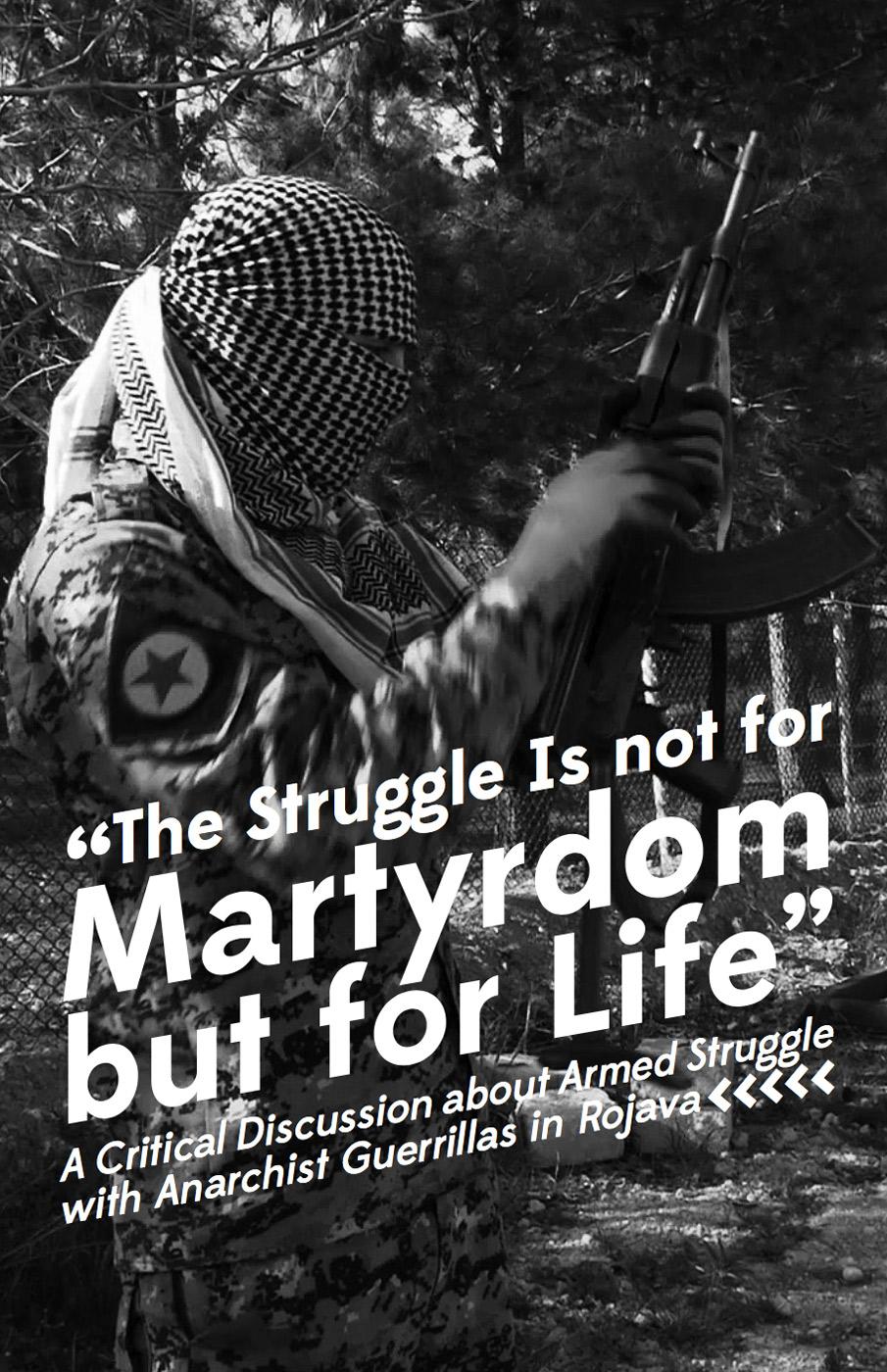

“The Struggle Is not for Martyrdom but for Life”

A Critical Discussion about Armed Struggle with Anarchist Guerrillas in Rojava

At the end of March 2017, news spread that a new anarchist guerrilla group had formed in Rojava, the International Revolutionary People’s Guerrilla Forces (IRPGF). Their emergence has reignited discussions about anarchist participation in the Kurdish resistance and in armed struggle as a strategy for social change. It has been difficult to communicate with comrades in Rojava about these important questions, as they are operating in wartime conditions and surrounded by enemies on all sides. Therefore, we are excited to present the most comprehensive and critical discussion yet to appear with the IRPGF, exploring the complex context of the Syrian civil war and the relationship between armed struggle, militarism, and revolutionary transformation.

The developments in Syria foreshadow a rapidly arriving future in which war is no longer limited to specific geographical zones but becomes a pervasive condition. State and non-state actors have been drawn ineluctably into the conflicts in Syria, and those conflicts extend far beyond its borders; today, civil war is becoming thinkable again in many countries that have not experienced war within their home territories for 70 years. Proxy wars, once geographically contained, are spreading around the world as religious denominations, ethnicities, nationalities, genders, and economic classes become proxies in the struggles between various ideologies and elites. As capitalism generates intensifying economic and ecological crises, these struggles are probably inevitable. But while they offer new opportunities to challenge capitalism and the state, they hardly point the way to the relations of peaceful coexistence and mutual aid that anarchists desire to create.

Is it possible for anarchists to participate in such conflicts without abandoning our values and principles? Is it possible to coordinate with forces pursuing different agendas while retaining our integrity and autonomy? How might we confront these situations without turning into a militarized war machine? From the vantage points of Europe and the United States, we can only develop limited perspective on these questions, though it is necessary to form our own critical hypotheses. We are grateful for the opportunity to engage in dialogue with those who are fighting in Rojava, and we hope to facilitate conversations on this topic across blockades and battle lines all across the world.

Kurdish forces have been calling for international supporters to fight alongside them for years now. How does this play out in practice? Do you consider yourselves to be equal and autonomous participants in both the fighting and the transformation of society? Or you feel your role to be allies supporting their defense?

First, it is important to realize that not all international supporters come to Rojava, or for that matter to the broader region of Kurdistan, for the same reason. As you are aware, there has been a steady flow of international supporters joining the ranks of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) for decades now. Additionally, international support has come from neighboring countries as well as other parties and guerrilla groups like the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA).

More recently, however, international supporters have come to the region mostly as a result of the growth of Daesh (ISIS) and its full-out assault in both Iraq and Syria. A few years ago, during the period of the battle of Kobanê and the genocidal campaign by Daesh in Rojava and Shengal, various international groups and individuals came to struggle for a myriad of reasons. For example, the Lions of Rojava attracted those with more militaristic, right-wing and religiously motivated ideologies and perspectives. At the same time, the Turkish militant Left, namely the Marxist-Leninist Communist Party (MLKP) and the Turkish Communist Party Marxist-Leninist (TKP/ML) had arrived in Rojava (to later include the United Freedom Forces, or BÖG, which would be formed after Kobanê) and joined the armed struggle in an effort to assist Kurdish forces and aid the struggle not only in Rojava but in Bakur (Northern Kurdistan — Turkey) and broader Turkey.

Thus, simultaneously during those pivotal months in Kobanê, there were Christian fundamentalists, fascists, and Islamophobes fighting alongside Turkish and international communists, socialists, and even a few anarchists. That is not to say that all Western fighters are either fascists or leftists. On the contrary, in fact, quite a few international supporters have simply identified as anti-fascists, supporters of the Kurdish struggle, liberal feminists, democracy advocates, and those with a fascination with the democratic confederalist project unfolding in Rojava. While the situation has changed on the ground and many of those with right-wing or religious convictions are no longer fighting with the People’s Protection Units and Women’s Defense Units (YPJ/G), there is still an eclectic and far from monolithic mix of international supporters here.

In practice, international supporters are placed in different units depending on certain criteria. For example, prior military personnel who come to Rojava may have access to Kurdish units that would, for the most part, be closed off to those who do not have prior military experience. Those include sniper (suîkast) and sabotage (sabotaj) units (tabûrs). Internationals who come to fight for ideological reasons, for anarchism, communism, or socialism, could choose to go to one of the Turkish party bases to train and fight as an attached member of their guerrilla units. Most international supporters, however, join a Kurdish unit within the YPJ/G and fight alongside the Kurds, Arabs, Ezidis, Armenians, Assyrians and other groups within the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

The social position of international supporters in relation to the local and indigenous members of the military forces is of course complex. For the people of Rojava and for the broader Kurdish liberation movement, it is an honor for them to have international supporters come to defend them when they feel that the international community, for almost a century, has abandoned their struggle for autonomy and self-determination. Yet, there is this almost celebrity atmosphere around some Westerners who come here to fight, as well as a tokenizing and sometimes paternalistic atmosphere on the part of some elements of the local political and military establishment. Of course, this changes depending on the international supporters’ reasons and motives for coming to Rojava. For example, some international supporters take great pleasure in showing their faces, posing with weapons and gloating about their “accomplishments.” Others choose to hide their faces and identities for both political and practical reasons.

There is no doubt that some international supporters have used the conflict in Rojava as a vehicle for personal advertising, which is of course part of the “age of the selfie” and social media. This has allowed some of them to make a small fortune writing books and using the revolution for their own gain. This is opportunism and adventurism at its worst. This is a small minority of the international supporters here and in no way indicative of the motives or actions of the much larger population of foreign fighters. While there is an appreciation for those who have brought the conflict and revolution to a much wider audience, there is also the fact that those who struggle here can, in most cases, forget the struggle and have the privilege to go back to their comfortable lives. There are also the war-tourist types who come here for the love of combat and fighting. They gloat about their military experiences and many even have served or attempted to join the French Foreign Legion. When asked, they often express a desire to travel to Ukraine or to Myanmar to continue fighting after leaving Rojava.

This brings us to an important theoretical position that we hold as the IRPGF. For us, we believe that many of the international supporters, specifically most Westerners, reproduce their privilege and social position here in Rojava. We want to introduce the concept of the “safe struggle.” That is to say that, since this war is supported by the United States and Western powers, it is safe to fight against the enemy and not face the repercussions for being in an organization whose ideology is Apoist (Apo is an affectionate nickname for Abdullah Öcalan, one of the founding members of the PKK), and therefore linked to a declared terrorist organization. There is no real penalty for involvement in Rojava except if one has direct links to some of the more radical groups here. For example, Turkish nationals who fight with the groups here are declared terrorists by the state of Turkey and even the comrades of the Marxist-Leninist Party (Communist Reconstruction) were arrested and imprisoned leading to their offices being closed across Spain on charges that they had links to the PKK. These unique cases aside, the vast majority of international supporters who come to fight Daesh and help the Kurds are safe from prosecution.

Additionally, in some cases, this reproduces the often-cited example of Western intellectuals and activists applauding a conflict beyond their borders but not willing to sacrifice their comfort and privileges to increase the fight at home. Some international supporters can come and be revolutionaries for six months or a year, they can be applauded and self-congratulatory and return back to their complacency and normal existence. This is not the majority of cases, but it is still an issue here. Also, coming for a few months or a year is in no way something we want to downplay or ridicule. In fact, every international supporter does put their life in danger by simply choosing to come to an active war zone. Concordantly, international supporters can learn skills and new perspectives while risking their lives here in the struggle and then go back to their homes and continue struggling there in a variety of ways.

Some international supporters have even changed their ideological positions in both directions. Mostly in a positive direction, seeing women’s liberation and self-organization to be key components to a more liberated life. A small minority have changed their opinions for the worse, claiming that the Kurds are incompetent fighters, that the revolution has failed or will fail and that coming to Rojava did not provide the unrestrained combat and war that they desired. With all of this in perspective and as we will discuss, what will happen when the international powers turn their backs on the project in Rojava and have no more use for the revolutionary forces? Will the vast majority of international supporters be willing to fight against Turkish forces or, for that matter, even US forces? This remains to be seen.

In contrast to the aforementioned group of international supporters, there are those who have come here with a profound depth, clarity, and analysis of their ideological positions, the regional geopolitics, and guerrilla warfare. The mixture, quality, and amount of communist, socialist, and anarchist guerrilla fighters is unsurpassed in any other armed conflict around the world. This provides new opportunities and has led to some unique innovations, like the International Freedom Battalion (IFB), as well as joint training and operations, but also raises the specter and danger of repeating history.

In the final analysis, those who have come for ideological reasons or to support the people of Rojava and their struggle feel that they are equal participants in both the fighting and social transformation while others, at this time a growing minority, who have come with their military experience or a war-tourist type attitude aren’t and in some cases don’t want to be considered equal, claiming to know more about warfare than the local forces on the ground. This can make for tense exchanges and sometimes physical confrontation and intimidation.

We, as the IRPGF, are both equal and autonomous participants and, of course, we are allies supporting the people’s defense. We do not see them as mutually exclusive. Yet, our autonomy is in some ways limited, since we are a part of a much larger struggle with a semi-formalized military structure and set of alliances. We are under the YPG, which means we are under the SDF which at this point cooperates with some US military forces and those of other Western countries in attacking Daesh. We see this as pragmatism and, of course, this does not change our opinions that the United States is as much our enemy as Daesh or any state for that matter. Yet, we also recognize that since it is the foreign policy of the United States that eventually led to the creation of Daesh, they ultimately must be responsible for combating them.

With the complex set of alliances and international powers aside, this struggle contains both indigenous and international characteristics, which makes it all the more important and necessary to defend. What we are currently investigating and learning, through (self-)criticism, theory, and practice, is the relationship of internationalist revolutionary anarchists to an indigenous struggle which sees itself as part of an internationalist revolutionary movement that will spread beyond its “borders.”

Since the majority of our energy is focused on armed struggle, we at present have limited projects in civil society. We are presently working to support anarchist initiatives and capabilities within civil society. Yet, social transformation is not exclusive to projects in civil society. For example, local Arab villagers who neighbor the base we are stationed at come every other day to give us milk and yogurt they produce, while we provide them with sugar or other commodities they do not have in an act of mutual aid. This creates a bond of solidarity and collective life. We also have a positive relationship with a few Armenian families in the region. The simple act of drinking chai with someone and kissing them on the cheek is the first step towards building relationships which in the long term can help lay the foundation on which to build projects leading to social transformation.

International fighters, particularly anarchist and communist fighters, have been organizing separately in Rojava for some time already. Why is that? What is your relation to other Kurdish structures?

As we alluded to in the first question, most international anarchist, Apoist, socialist, and communist fighters in addition to other fighters who identify more as anti-fascists and anti-imperialists have been attempting to organize separately in Rojava for some time. This is not something new. Answering this question will require a description of the historical situation of the Turkish Left and the numerous armed groups that operate within the region.

For the Turkish Left, specifically the Left that is involved in armed struggle and that maintains guerrilla units, the relationship between the groups is one that has changed and adapted over time. There was a time when Turkish Left parties would see each other as enemies as much as they would see the Turkish state or the capitalist system. This led to inter-party violence and even deaths. Yet, as history has revealed, the Turkish state has proved much stronger and more resilient than many have expected. Previously, the vast majority of Turkish society did not advance the struggle as many of the parties, being traditional Marxist-Leninists, dogmatically believed would naturally happen as result of historical necessity. In fact, with the referendum in Turkey nearing, and Erdogan practically secure in an “evet” or “yes” victory, the parties saw a necessity to unite and struggle together. This is not to say that they had not done so before. In fact, many of the parties, the largest one being the PKK, had worked with other guerrilla groups in the vast mountainous regions of Turkey, sharing resources and training and even conducting joint operations. It was on March 6, 2016, when history was made in Turkey with the formation of the People’s United Revolutionary Movement (Halkların Birleşik Devrim Hareketi). This united front brought 10 of the major parties involved in the armed struggle under one structure and banner to fight against the government of Erdogan and the Turkish state.

Of course, one must also look at Middle Eastern history in general to understand how the various Turkish parties operated within various countries and participated in various conflicts. For example, The Communist Party of Turkey/Marxist–Leninist (TİKKO), ASALA, and the PKK operated in Lebanon (Beqaa valley) and trained alongside the PLO and various Palestinian, Lebanese, and international guerrilla groups, even conducting joint operations. In Syria, the PKK set up its headquarters and opened up party offices and training facilities in Rojava in the 1980s until the mid-’90s. Abdullah Öcalan was able to operate relatively freely with the support of the Syrian regime, who saw Turkey as an enemy. Turkish-Syrian tensions and the threat of war would force Hafiz al-Assad to cut all ties with Öcalan and expel him from Syrian territory. The collapse of the Soviet Union forced many Turkish and international guerrilla groups underground and limited their mobility, resources, training, and operations. The Syrian Civil War and the start of the revolution in Rojava provided another opportunity for Turkish parties which were illegal, clandestine, and in the mountains to come to set up operations and bases in Rojava by which to support the struggle as well as organize and communicate more freely and effectively. This led to multiple parties setting up karargahs (headquarters) in Rojava.

With the struggle in Rojava intensifying and the parties needing to share resources, intelligence, and military operations, the parties, with the lead of MLKP, formed the International Freedom Battalion in Rojava. This experiment in joint management and command, unifying the various parties and groups under one banner to fight, was the first experiment of its kind in Rojava and preceded the formation of Peoples’ United Revolutionary Movement (HBDH). This experiment has had mixed results. For example, the IFB is run on the principles of democratic centralism, which we, as the IRPGF, disagree with. We would rather it be horizontal and equal for all groups and members. Additionally, the vast majority of the groups, parties, and fighters within the IFB are Turkish, leading to the international character being skewed. Even Kurdish forces refer to the IFB as “çepê turk” or “Turkish Left.” Yet, this aside, we would argue that it has had positive and symbolic value as well as various military successes. It has shown that the various parties and groups, including the IRPGF, can work, train, and fight together against a common enemy, uniting our energies and forces to achieve victory both in combat as well as in civil society.

The International Freedom Battalion, though it is directly under the command of the joint leadership of the various parties and groups, is ultimately under the command of YPG and SDF forces. While we are autonomous in terms of our military structures, unit organization, and individual movements, we await orders and directives directly from YPG about our position and movements on the battlefield, as does the rest of the IFB. This situates us directly under the command of YPJ/G and therefore we, too, share their alliances and the battlefield with those they conduct joint operations with. Yet, the parties and groups maintain their autonomy as separate entities outside the structure of the IFB to disagree with the positions of Kurdish forces and even to criticize certain policies and decisions. Yet, while part of the IFB, we are careful about the positions, views, and perspectives we express while using the IFB name and structure. Ultimately, the IFB has proved to be a unique experiment and laboratory to bring (far/ultra-)leftists and radicals of all colors and persuasions to fight under one unit and command structure.

Considering that the alliance between Kurdish and US forces is not likely to last indefinitely or to create space for radical projects to grow in Rojava, how can anarchists position themselves in this struggle? Can you maintain autonomy from decisions made by others in Rojava who are involved in this alliance?

The word “alliance” here is very misleading, indeed it is a strong and implicit word. The US and its coalition allies, for totally unrelated political and economic reasons, have made a project of eliminating an armed group (Daesh) from which the Revolution must defend itself and which YPJ/G would also like to eradicate. YPJ/YPG are on the same battleground as US forces. Since they share the same enemy, and since the inherent political, ideological, and economic antagonism between the two is, by a certain priority of interests, delayed from igniting, military cooperation is not surprising. There is no political alliance between the US and the revolutionaries of Rojava.

Indeed, we believe that the cooperation between revolutionary forces and US forces is not likely to last. Of course there exist forces here in Rojava that would seek a nation-state or have used nationalist sentiments to stir up support. Right next door is the US supported Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) under the leadership of Masoud Barzani, who is yet another US puppet in the region. The KRG has a virtual embargo on Rojava. Barzani and the KDP are seen by many as traitors for allying themselves with Turkey at the expense of the Kurds and the Ezidis of Shengal. Additionally, the KRG seeks to “stir things up,” both politically with groups like the Kurdish National Council (ENKS) and KDP within Rojava as well as militarily with the Rojava Peshmerga. The enemies of this revolution are countless.

It is often noted that some anarchist thinkers like Murray Bookchin contributed to this social revolution in the first place, which led Abdullah Öcalan to move away from Marxism-Leninism and create his theory of “Democratic Confederalism.” Regardless of how accurate that is, ultimately anarchists both in the armed struggle and in civil society can make an impact on this revolution. Through dialogue and joint projects, we can work with local communities and develop relationships that can further entrench the gains of the revolution while pushing it forward. The more influence anarchists and anarchist philosophy have in dialogue with the people and structures in Rojava, the more we can build something new together and focus on transformation not only in Rojava but around the world. That is the importance of connecting the struggles as we have done so far regarding Belarus, Greece, and Brazil. The struggle in Rojava is the struggle in every oppressed neighborhood and community. It is the struggle for a liberated life and that is where anarchists can have their biggest impact.

As anarchists, we are uncompromisingly against all states and authority. That is non-negotiable. While we fully acknowledge the role of the various parties in struggling and fighting to liberate territory both in Rojava and in the broader mountainous regions of Kurdistan, we believe that critical solidarity allows us to work, fight, and possibly die alongside the parties while having the autonomy to remain critical of their ideologies, structures, feudal mentalities, and numerous policies. We can maintain autonomy in the sense that we can disagree with the positions or choose not to fight should the alliances the revolutionary forces make be beyond survival and pragmatic geostrategic necessity. In the final analysis, should the revolutionary forces make formal alliances with state powers and Rojava be turned into a new state, even if that state is social democratic, the IRPGF would leave and move our base of operations elsewhere to continue the revolutionary struggle. Anarchist projects within civil society would still be able to operate and function so long as they were allowed to do so, and they should, but, it is most likely that anarchist as well as communist guerrilla groups would no longer be allowed to operate in Rojava.

Have you experienced a tension between engaging in armed struggle and developing social projects in Rojava? In what ways do they feed into each other and reinforce each other? In what ways are they in contradiction?

Our group is only in the beginning stages of developing social projects in Rojava. It is difficult for a unit to organize and maintain social projects while engaged, at the same time, in armed struggle if it lacks the resources in terms of personnel and infrastructure. This requires more people to be here; we must reach the critical mass necessary to develop a successful project. Some of our comrades have worked in civil society before and are actively working on creating new initiatives that are both sustainable and achievable. This will allow us to achieve our respective commitments to the armed struggle and the social revolution.

Has the war effort in the Rojava community subjected other structures to its imperatives? Are there spaces or spheres of life in which control is centered in the hands of militarized groups, contributing to de facto hierarchical relations? How do we prevent military priorities from determining who has power in a community at war?

Certainly the war in Rojava and the broader Syrian and Iraqi Civil Wars have drastically changed the relationship between civil society and military forces. What is currently going on in Rojava can be aptly described and characterized, as some hevals [comrades] have put it, as “war communism.” The current situation in Rojava has subjected much of the economy and civil society to the war effort. However, this is not surprising. Rojava is surrounded by enemies who seek to destroy the nascent revolutionary experiment. Daesh is a highly lethal and efficient para-state actor with tremendous resources, both financial and military, as well as a fighting force numbering in the tens of thousands. As such, it is one of the most brutal and capable threats against Rojava itself. Had it not been for the massive war effort on the part of large segments of the society, most notably the resistance of Kobanê and its subsequent victory which was a pivotal turning point, Daesh would have been victorious and continued its rapid expansion.

While the war has turned and Daesh is now on the run both in Iraq and Syria, Turkey entered the war seeking to stifle YPJ/G efforts to secure contiguity between the Kobanê and Afrîn cantons. One must be cognizant of the fact that almost daily, Turkish forces on the borders of Rojava bombard targets within its territory, killing scores of civilians and military forces. Likewise, to the east in Iraq, the Kurdistan Regional Government (Bashur) under the leadership of Masoud Barzani and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) continue to impose a virtual blockade and embargo on Rojava in addition to attacking People’s Defense Force (HPG) and The Sinjar Resistance Units (YBŞ) positions in Shengal using the Peshmerga. Additionally, Barzani and the KDP collude with Erdogan, the fascist Justice and Development Party – Nationalist Movement Party (AKP-MHP) government and the Turkish state, sharing intelligence, resources, and conducting joint military operations.

Without a doubt, war leads to de facto hierarchical relationships and seriously hinders horizontal relations and community power. In fact, multiple layers of hierarchical relationships exist. There are hierarchies within the party structures which permeate social structures and extend into the broader civil society. Those tend to be, for example, whether someone is a cadre or not, how long they have been in the movement for, their ideological formation and knowledge, their influence and contacts in addition to their combat experience. This can be perceived as a system of rank, privilege, and advancement. It does in fact exist, but it is something that operates in tension with a party which is self-critical of this and an ideology that seeks to transcend these relations in the midst of a real existing social revolution. While the cadre members of the militarized groups do in fact have a de facto social position which would be above other people in society, they ultimately answer to the people through the commune structure and the larger framework of the Northern Syrian Federation. Ultimately, these hierarchical relations exist as a military necessity in the midst of one of the most brutal wars. As anarchists, we see them and understand why they are necessary while being critical of their existence and seeking to challenge these relations of centralized authority and control. It is positive that these relations can be criticized using the tekmil process (a directly democratic assembly for critiquing a commander or others in a unit), a serious, vital practice of criticism-self-criticism and self-discipline which has its roots in Maoism.

Hierarchical relations of power, while sometimes necessitated by military realities and priorities in the context of combat, must exist as something which we want and desire from one another in order to act effectively. When there is time for deliberation, we can discuss, criticize, and make collective decisions. In combat, one expects immediate guidance, instruction, protection, certainty, and accountability from comrades more experienced and knowledgeable, because there are many decisions and tasks affecting the group that one cannot deal with and should not be burdened with. This applies to training and secure recruiting as well. But these relations can ultimately have the potential to harm the autonomous, horizontal, and self-organized nature of communities if they are not understood and practiced in accordance with other ideological principles. How can we, as anarchists and members of the IRPGF, prevent kyriarchal relations in this context—that is, in these overlapping contexts? The complexity of this question additionally reveals an inherent problem with how the question is framed. That is to say, that somehow the military priorities or defense of a community are separated from the community itself; imposed from without by some non-community actor. While it is true that military priorities are imposed on some communities, for example, evacuating villages that are on the front lines, in danger of attacks and using people’s homes for temporary military outposts, the fact is that in Rojava, local communities, neighborhoods, and ethno-religious communities are responsible for their own defense.

This is not something new. In fact, it goes back to the Qamishlo riots of 2004 (an uprising of Syrian Kurds in the northeast) that led to the creation of community defense initiatives and the precursor to the YPG. To protect against the larger defense structure, the YPG, should it seek to impose its will in a military style coup and take power away from the communities, communities have their own defense forces, the HPC (Hêzên Parastina Cewherî). While the YPG represents the people’s guerrilla army of Rojava, there are smaller forces—for example, the Syriac Military Council which is comprised of Syriac Christians and works to protect that community. Defense itself is decentralized and confederalized while at the same time retaining the ability to deploy rapidly, to call on troops and even conscription, which does occur in Rojava.

We believe and affirm that communities at war must be responsible for their own defense. Yet, with large state, para-state, and non-state actors attacking these communities in an effort to wipe them out, there is a necessity for even larger military forces. This may necessitate certain processes that, in a time of war, curtail the autonomy of a community. This reality is one that we are forced to live with. Ultimately, there is a dichotomy and tension between communities at war and the military forces which confront enemies sometimes many times their size. We are tasked with ensuring, as much as possible, that communities retain their autonomy and decision-making processes while simultaneously protecting them and ensuring their survival. Communities are ultimately responsible for their defense; when the need arises, all the unique and diverse communities can come together to form a larger military force for their collective protection. This means that each community constitutes a fundamental component part of the much larger force whose task is the protection of all the communities. This tension, between the community and military, is but another aspect of the philosophical tension between the particular and the universal. Our task is to ensure that this imbalance is minimized as much as possible so that communities can remain autonomous and ultimately have the final say as to their priorities and defense.

What is it that distinguishes anarchist armed struggle formations and strategies from other examples of armed struggle? If you oppose “‘standing armies’ or ossified revolutionary groups” but grant that armed struggle may be necessary until it is impossible to force hierarchical institutions onto anyone, what is the methodological difference that can keep long-term anarchist guerrilla forces from functioning in the same way that a standing army or ossified revolutionary group does, concentrating social power?

A question often asked of us is how we are different from other armed left-wing groups? What are our distinguishing characteristics? As an anarchist armed struggle formation, along with other anarchist groups around the world, we strive for liberated communities and individuals based on fundamental principles within anarchism. We are not dogmatic nor orthodox in our understanding of anarchism, but perpetual iconoclasts and innovators. Anarchism is an ever changing and growing ideology that cannot be separated from life itself. While other non-anarchist left-wing groups may want some version of socialism and/or communism, we are ultimately distinguished from these armed struggle formations by our understanding of authority, both within the group and beyond. We have no leader. There are no cults of personality and no portraits of ourselves hanging on the wall. We take inspiration from the Zapatistas who cover their faces and focus more on the collective than on individuals, for we, as a collective of individuals, represent many unique identities and social positions. We make decisions by consensus, and when we are on the battlefield we agree on one or more comrades who will be responsible for the operation. There is no permanent command structure within the IRPGF. There are rotating positions of responsibility and assignments, the logic being not to reproduce military ranks or technocratic class structures.

Anarchist armed struggle formations are not new. For example, there are anarchist groups around the world including the Conspiracy of Cells of Fire, FAI-IRF (Informal Anarchist Federation — International Revolutionary Front), and Revolutionary Struggle. We do not necessarily agree with all the positions of these groups or their members. For us, we do not seek to be elitist or to be mountain guerrillas who leave the world to focus on people’s war in the countryside, though that is an important aspect of the struggle. We seek to bring the mountains to the cities and vice versa. It is important to connect all the struggles around the world, for they are interconnected by nature due to the various systems of oppression and domination which exist. We too “shit on all the revolutionary vanguards of the world” as Subcomandante Marcos once said. We do not see ourselves as anarchist vanguards. We are anything but this.

The IRPGF feels it is necessary to be with the people and to understand the social character of the revolutionary process. There is no revolution without all of the communities, neighborhoods, and villages participating. We do not seek to glorify the arms and weapons we possess, though we do see them as a vehicle towards our collective liberation. Yet liberation is not possible if the social revolution is not present. Therefore, we are not another urban guerrilla group that seeks only to destroy without building anything social and communal. Of course, having arms and engaging in armed struggle carries with it a tremendous responsibility and great danger, not only for ourselves but for the power we possess. We agree with the guerrillas who often repeat the Maoist principle of not even taking pins from the people. We are revolutionaries guided by principles, not a marauding gang of mercenaries. This is the foundation by which we, as the IRPGF, seek to develop a collective ethic and understanding of armed struggle.

Knowing full well that armed struggle may be necessary for many years and decades to come, and realizing that as the years progress, structures become more entrenched and rigid, we are concerned about the creation of certain group dynamics that could lead to various hierarchies and a concentration of social power wherever we are based. In order to minimize this risk, we feel that it is necessary to not only be professional full-time revolutionaries but equally members of a living community. That means that we must be involved with local struggles and projects within civil society. Whereas a standing army or an ossified revolutionary group see their position as either professional work or lifelong dedication to struggle, they both maintain their distance and remoteness from communities and everyday life.

Anarchist guerrilla groups must remain horizontal entities and resist the temptation or structural necessity to centralize and concentrate social power. Should they fail to do this, they would no longer be liberating nor anarchist, in our perspective. As the IRPGF, understanding this danger, we feel that developing projects and developing relationships within civil society is the main way to withstand the creation of social hierarchies. It is a process that will be fraught with contradictions and errors. Yet it is through these contradictions and shortcomings coupled with our criticism-self-criticism mechanisms and horizontal self-organized structure that will challenge the creation of an ossified revolutionary group that has centralized its own authority and concentrated social power.

As you say, the conflicts in Syria, Ukraine, and elsewhere are only the beginning of what will be a protracted and messy period of global crisis. But what do you consider the proper relationship between armed struggle and revolution? Should anarchists seek to commence armed struggle as soon as possible in the revolutionary process, or to delay it as long as we can? And how can anarchists hold our own on the terrain of armed struggle, when so much depends on getting arms—which usually means making deals with state or para-state actors?

First of all, there is no general formula for how much armed struggle is necessary to initiate and advance the revolutionary process, nor at which point it should commence, if at all. For the IRPGF, we recognize that each group, collective, community, and neighborhood must ultimately decide when they initiate armed struggle. Armed struggle is contextual to the specific location and situation. For example, whereas throwing a Molotov cocktail at police is fairly normalized in the Exarchia neighborhood in Athens, Greece, in the United States the person throwing it would be shot dead by the police. Each particular local context has a different threshold for what the state allows in terms of violence. However, this is not an excuse for inaction. We believe that armed struggle is necessary. Ultimately, people must be willing to sacrifice their social position, privilege, and lives if necessary. Yet we are not asking people to go on suicide/sacrifice missions. This struggle is not for martyrdom but for life. Should it require martyrs, like the struggle here in Rojava and Kurdistan, that will be part of the armed struggle and revolutionary process as it unfolds.

Armed struggle does not necessarily create the conditions for a revolution and some revolutions may occur with little to no armed struggle. Both armed struggle and revolutions can be spontaneous or planned years in advance. Yet, local or national revolutions, which in some cases have been peaceful, do not create the conditions for world revolution nor challenge the hegemony of the capitalist world-system. What remains our fundamental question here is—when should one commence armed struggle? To start, we think that one has to analyze their local situation and context. The creation of local community and neighborhood defense forces which are openly armed is a critical first step to ensuring autonomy and self-protection. This is a powerful symbolic act and one that will certainly attract the attention of the state and its repressive forces. Insurrection should happen everywhere and at all times, but it doesn’t necessarily need to happen with rifles. Ultimately, armed struggle should always be done in relation to living communities and neighborhoods. This will prevent vanguard mentalities and hierarchical social positions from developing.

Revolutions are not dinner parties and, what’s worse, we do not choose the dinner guests. How can we, as anarchists, remain principled in our political positions when we have to rely on state, para-state, and non-state actors to get arms and other resources? Firstly, there is no ideologically clean and pure revolution or armed struggle. Our weapons were made in former Communist countries and given to us by revolutionary political parties. The base we are staying in and the supplies and resources we receive come from the various parties operating here and ultimately from the people themselves. Clearly, we as anarchists have not liberated the kind of territory we would need to operate on our own. We must make deals. The question then becomes: how principled can our deals be?

We have relationships with revolutionary political parties that are communist, socialist, and Apoist. For us, we fight against the same enemy at this point and our combined resources and fighters can only further the struggle. Yet, we remain in critical alliance and solidarity with them. We disagree with their feudal mentalities, their dogmatic ideological positions, and their vision of seizing state power. We both know that should they one day seize state power, we will be enemies. Yet for the time being, we are not only allies but comrades in the struggle. This does not mean that we have sacrificed our principles. On the contrary, we have opened a dialogue on anarchism and criticized their ideological positions while affirming the principles and theoretical positions we share in common. This exchange has transformed us both and is part of what some of them refer to as the dialectical process: the necessity of both theory and practice to advance both the armed struggle and the social revolution.

For the IRPGF, making deals with other leftist revolutionary groups we can find common ground with is a reality we live with. Yet, we also must acknowledge that the larger guerrilla structure that we are a part of does make deals with state actors. While we once again reaffirm our position against all states, which is non-negotiable, our structure makes pragmatic deals with state actors to survive another day to fight. For the time being, all of our supplies and resources come from revolutionary parties that we are in alliance with, who also make concessions and deals with state and non-state actors. We recognize this as a contradiction but a harsh reality of our current conditions.

Anarchists must choose, depending on their particular context and situation, what kind of deals they can make and with whom. Should they need to be pragmatic and make deals with state, para-state, or non-state actors to acquire arms, to hold on to their terrain, or to, at the very least, survive, that will be addressed and critiqued when the time comes. Ultimately, collectives and communities will make decisions for how to advance in the revolutionary process and how to use the various state and non-state actors for their benefit, with the goal of eventually not needing them and destroying them all. In the final analysis, armed struggle is necessary for the revolutionary process and the various alliances we make we deem necessary to achieve this goal of a liberated world. We, as the IRPGF, believe and affirm the often-repeated phrase from Greece that the only lost struggles are the ones that weren’t given.

Sooner or later, every revolution divides into its constituent parts and necessary conflicts ensue. These conflicts determine the ultimate outcome of the revolution. Has this already begun in Rojava? If it has, how have anarchists dealt with this? If it has not, how can you prepare comrades around the world for the situation we will be in when the internal conflicts in the revolution rise to the surface, and it is necessary to figure out what the different positions are? Some comrades outside Rojava have been unsure how to understand some of the reports from Rojava, because in our experience there are always internal conflicts, even in the strongest periods of social revolution, and people reporting on the experiment in Rojava have been hesitant to articulate what they are. We can understand why it would be necessary not to speak openly about such conflicts, but any perspective you can offer us will be very useful, even if it is abstract.

The simple answer is yes, these conflicts have begun in Rojava. Within such a large party and confederal structure, contradictions and different factions have emerged. There are those who seek to carry the revolution to the end and others who are ready to make compromises on certain aspects of the revolution in order to secure whatever has been achieved up until now. There are those who still dream of a Marxist-Leninist Kurdistan and others who are ready to open up to the West and ally themselves with the “forces of democracy.” Within the armed struggle, there are some who want to unleash an all-out people’s war while others claim that the time for armed struggle is nearing its end and that we should slowly cease hostilities. Within this chaotic political arena, with what is a seemingly endless array of acronyms, how do we as members of the IRPGF navigate these murky and often dangerous waters?

As anarchists, we navigate within these complexities and contradictions with the goal of trying to claim as much ground as possible for anarchism. We align ourselves with the sections of the revolution and the party that are closest to us. The alliances we forge are ones that are most facilitating and the least assimilating. We try to keep ourselves safe from assimilation both ideologically and as a group. Being in an autonomous space that supports our goals provides us with tremendous opportunities. There is free space that the party gives to groups such as ours for training, to develop projects and outright space for revolutionary experimentation. The more anarchists come here to Rojava to help us build anarchist structures, the more we will influence and make our goals a reality in society. For example, the youth, who are more critical of their feudal and traditional past, are at the forefront of tremendous social changes and advancements. We want to work with the youth to form educational cooperation and, as anarchists, to focus on anarchist theory and even address queer, gender, and sexuality (LGBTQ+) issues which are still very taboo in the majority of society.

There is a vast space to experiment and build the anarchist structures that will continue to revolutionize society and further liberate all individuals and communities. We believe that our work as anarchists, both in the armed struggle and in civil society here in Rojava, will be valuable to the entire anarchist community worldwide. We look forward to sharing our results, to everyone’s continued solidarity, and to the anarchists who will join us out here.