Center for a Stateless Society

Anarchy and Democracy

June C4SS Mutual Exchange Symposium: Anarchy and Democracy (Cory Massimino)

1. The Abolition Of Rulership Or The Rule Of All Over All (William Gillis)

Democracy as Collective Decision-making

Democracy As “Getting a Say in the Things That Affect You”

Democracy as a Transitory State

2. Democracy, Anarchism, & Freedom (Wayne Price)

Anarchism is Democracy without the State

Does Democracy Require Domination?

3. Democracy: Self-Government or Systemic Powerlessness? (Derek Wittorff)

4. The Linguistics of Democracy (Alexander Reid Ross)

5. Anarchy and Democracy: Examining the Divide (Shawn P. Wilbur)

Progress and the Anarchic Series

6. On Democracy as a Necessary Anarchist Value (Kevin Carson)

7. The Regime of Liberty (Gabriel Amadej)

When Property Is Theft, and When Property Is Liberty

An Antidote to the Problem of Democracy

8. Demolish the Demos (Grayson English)

9. Anarchism as Radical Liberalism: Radicalizing Markets, Radicalizing Democracy (Nathan Goodman)

Tell me what democracy looks like

Political Culture and Anarchism

10. Politics and Anarchist Ideals (Jessica Flanagan)

11. Response to Goodman (William Gillis)

12. Embracing the Antinomies (Shawn P. Wilbur)

13. Formality, Collectivity and Anarchy (Derek Wittorff)

14. Response to Wittorff (William Gillis)

15. Individualist Anarchism vs. Social Anarchism (Wayne Price)

16. Comments on the Other Lead Essays (Kevin Carson)

17. Response to Carson (William Gillis)

18. Reply to Kevin Carson and William Gillis (Derek Wittorff)

19. Further Response on Democratic Anarchism (Wayne Price)

20. Social, but Still Not Democratic (Shawn P. Wilbur)

21. Reply to Alexander Reid Ross (William Gillis)

22. Response to Shawn Wilbur and Gabriel Amadej (Wayne Price)

23. Anarchism Without Anarchy (Shawn P. Wilbur)

24. Non-Coercive Collective Decision Making: A Quaker Perspective (Robert Kirchner)

25. A Last Response to Shawn Wilbur (Wayne Price)

26. Antinomies of Democracy (Shawn P. Wilbur)

I.—Principles and Rhetoric in Defense of “Democracy”

June C4SS Mutual Exchange Symposium: Anarchy and Democracy (Cory Massimino)

June 1st, 2017

Mutual Exchange is the Center for a Stateless Society’s effort to achieve mutual understanding through dialogue. Following one of the most divisive Presidential elections in recent U.S. American history and a dangerous victor’s contested ascension to power, the political climate is one of intense ideological strife and disagreement. There is no better time to refocus at least some of our efforts on respectful and mutually beneficial discourse. Periodically delving into the weeds of complex theoretical topics to collaboratively experiment with ideas is not only necessary for individual and collective intellectual progress, but is part and parcel of anarchist praxis itself.

“Fighting over the definitions of words can sometimes seem like a futile and irrelevant undertaking. However, it’s important to note that whatever language gets standardized in our communities shapes what we can talk and think about,” says William Gillis in his lead essay of our June symposium. Indeed, rather than pointless “infighting” and social posturing, the Center for a Stateless Society hopes to create a platform for free expression that benefits authors and readers alike by productively clarifying our values and principles.

Whether or not any sort of resolution, consensus, or agreement results from our ensuing dialogue is, perhaps ironically, not the point. Ten anarchist authors have chosen to participate in an in-depth examination of the idea of “democracy” and how it relates to anarchy. I hope they are able to develop, advance, and popularize their individual ideas, but also set a standard for productive, yet diverse debate that is sorely needed right now.

Combining the Greek words demos (“common people”) and kratos (“strength”), democracy means “rule of the commoners.” The philosophical and political debates surrounding democracy extend back 2500 years to Ancient Athens. For much of recent history, many people consider democracy to be a cherished value to protect and spread across the globe, while many others see it as a privilege they hope to someday enjoy. Even others, from all over the political spectrum, see democracy as an enemy to be squashed.

This C4SS Mutual Exchange Symposium will explore what anarchists have to say about democracy. What is the historical relationship between democracy and anarchy? Is democracy always entwined with the state? What should anarchists think of democratic government? What are truly democratic values and how do they relate to anarchist values? How does democracy relate to market exchange and social organization? How should those interested in social change view democracy? How do causes like feminism, anti-racism, anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, and anti-capitalism relate to democracy?

It is no secret that a President Trump is reigniting debates surrounding democracy and democratic values among many commentators. What will a Trump presidency mean for democracy around the world and how should anarchists react? Moving forward in the 21st century it is imperative that we get to the roots of these nuanced debates so that we are better prepared to build the new world in the shell of the old, while also staying afloat in the stormy seas of authoritarianism, political violence, turbulent geopolitical alliances, and genocide.

The June C4SS Mutual Exchange Symposium features the Center’s own William Gillis, Kevin Carson, Nathan Goodman, and Grayson English in addition to Shawn Wilbur, Wayne Price, Alexander Reid Ross, Gabriel Amadej, Derek Wittorff, and Jessica Flanagan. Every day this month the Center will publish another entry in our ongoing conversation from one of the ten authors fleshing out their thoughts regarding the above questions and issues. Some essays will remain stand-alone contributions while others will provide back-and-forth commentary between multiple authors.

I look forward to seeing these prolific and nuanced writers hash out all their points of disagreement as well as agreement and hope you stay with the Center throughout the entire month to gain both theoretical and practical insights from our symposium.

Before the exchange kicks off tomorrow, June 2nd, here are some preliminary texts and resources related to the longstanding anarchist debate on democracy that I hope are useful going forward:

-

The Anarchist Critique of Democracy – CrimethInc.

-

Are Anarchism and Democracy Opposed? A Response to CrimethInc. – Wayne Price

-

Against Democracy – Coordination of Anarchist Groups

-

Neither Democrats nor Dictators: Anarchists – Errico Malatesta

-

An Anarchist Critique of Democracy – Moxie Marlinspike and Windy Hart

-

Democracy is Direct – Cindy Milstein

-

Occupy and Anarchism’s Gift of Democracy – David Graeber

-

Direct Action, Anarchism, Direct Democracy – David Graeber

-

Down With the Law! – Libertad

-

Anarchy and Democracy – Robert Graham

Mutual Exchange is C4SS’s goal in two senses: We favor a society rooted in peaceful, voluntary cooperation, and we seek to foster understanding through ongoing dialogue. Mutual Exchange will provide opportunities for conversation about issues that matter to C4SS’s audience.

Online symposiums will include essays by a diverse range of writers presenting and debating their views on a variety of interrelated and overlapping topics, tied together by the overarching monthly theme. C4SS is extremely interested in feedback from our readers. Suggestions and comments are enthusiastically encouraged. If you’re interested in proposing topics and/or authors for our program to pursue, or if you’re interested in participating yourself, please email C4SS’s Mutual Exchange Coordinator, Cory Massimino, at cory.massimino@c4ss.org.

1. The Abolition Of Rulership Or The Rule Of All Over All (William Gillis)

June 2nd, 2017

Fighting over the definitions of words can sometimes seem like a futile and irrelevant undertaking. However it’s important to note that whatever language gets standardized in our communities shapes what we can talk and think about. So much of radical politics often boils down to acrimonious dictionary-pounding over words like “capitalism,” “markets,” “socialism,” “communism,” “nihilism,” etc. Each side is usually engaged in bravado rather than substance. Radical debates turn into preemptive declarations of “everyone knows X” or “surely Y,” backed by nothing more than the social pressure we can bring to bear against one another. And yet — to some degree — we’re trapped in this game because acquiescing to the supposed authority of our adversaries’ definitions would put us at an unspeakable disadvantage. The stakes of debates over “mere semantics” can be quite high, determining what’s easy to describe and what’s awkward or laborious.

Thus the partisan impulse is usually to define our adversaries out of existence: muddying their analytic waters, emphasizing any and all negative associations, and painting their conclusions as insane, verboten, or outgroup. At the same time we leap on any and all positive associations we can twist to serve our own ends. Debate over definitions is so often merely a game of social positioning: every word reverberating with the different associations of different audiences and thus what alliances you’re declaring or managing to ascribe to your interlocutor. Language is a messy, complicated, and nebulous place where fallacious arguments are not only par for the course but often thought to be how the whole thing hangs together. In the worst corners of academia and “radical” politics this is embraced wholesale, where philosophy is reduced to mere poetry and cheap ploys of emotive resonance: batted back and forth with an underlying smug derision at the entire affair. “Have you ever noticed that we use the same word for your job — your occupation — as we do for the occupation of Iraq?” and this is somehow treated as insightful rather than doing violence to clarity and honesty.

Obviously my biases here — and social affiliations — are quite apparent. While there can be a place for rhetoric to convey emphasis and it is sometimes necessary to counter fire with fire, in general I find these opportunistic language games detestable. Whenever possible I prefer a subversive linguistic pluralism, happy to adopt the language of those I’m speaking to, declaring myself, for example, pro-“capitalism” or pro-“communism” in some contexts and against “capitalism” or against “communism” in others. If by “capitalism” some poor soul means nothing more than economic freedom then I’m fine adopting his tribe’s language to reach him — the same holds true with “communism”. Yet opportunities for such ecumenism are few and far between; even in those situations where we can escape tribal jockeying and arguments from popularity, such words almost always carry hidden baggage through their broader associations, with the explicit definition hiding the implicit conclusions of its wider use. When it comes to semantics, I’m of the opinion that our first step should always be to discard popular associations as much as possible and decipher what are the most illuminating or fundamental dynamics at play, only then attempting to realign or reserve our most basic words for the most rooted concepts. If our final mapping of concepts to terms is idiosyncratic or provocative, or if it strips away the full array of associations found in common use, then perhaps all the better.

While such an approach is often contentious, I believe that it offers a relatively nonpartisan compromise and starting point in definition debates. Let us hold off as much as possible on barraging each other with claims about what’s more “authoritative,” much less what can be leveraged as proof of such, and likewise abandon the negative and positive association-judo. We can always return to this after we’ve sorted out what sort of realities are even before us to map our vocabulary to. This offers us a certain efficiency, handling some quite heavy work at the start, but at least offering us something other than an endless quagmire going forward. More important though is the danger that jumbled interpretive networks or misaligned concepts pose when normalized. Terms that fail to cut reality at the joints can mislead and obscure, make some basic realities incredibly hard to state or address. In language we should seek depth, generality, and accuracy first and foremost, not mere rhetorical expedience. There is a place for the play of “interestingly” open interpretations but such hunger should not consume us and sever our capacity to act.

Democracy and Anarchy

In many contemporary western societies “democracy” retains positive (if nebulous) associations. Naturally, many activists have therefore repeatedly tried to latch onto that term and redirect it in narratives or analysis that line up with their own political aspirations. “You like chocolate, right? Well anarchism is basically extra chocolately chocolate. It’s more chocolate than chocolate. It’s like direct chocolate.”

This opportunistic wordplay is at least self-aware, and such maneuverings seems fair game to many. After all, isn’t “anarchy” a similarly nebulous word — a site of contention and redefinition?

Yet I’d argue that the situations are quite different. The fight over “anarchy” is an inescapable one for anarchists because the world we want will never be obtainable as long as the term’s historical definition goes unchallenged. In every language that touched ancient Greek, “anarchy” bundles together the explicit definition of “without rulership” with the implicit definition of “fractured rulership” (what should really be called ‘spasarchy’) in a nasty Orwellianism that makes the concept of a world without domination unspeakable and often unthinkable. We have a term for the abolition of power relations and we use it instead to refer to chaotic, violent, dog-eat-dog situations of strong (albeit decentralized) power relations. In short, the fight over the definition of “anarchy” is a battle to untangle an existing knot.

On the other hand, “democracy” tends to stand for majority rule and etymologically for the rule of all over all. If there is an Orwellianism at play it is seems to me one of being too charitable to the term, sneaking in associations of freedom when one is in fact describing a particular flavor of tyranny. A situation more akin to “war is peace” than the “freedom is slavery” is at play with “anarchy.”

Honest proponents of democracy can of course contend that such an “ideal” would look nothing like our contemporary world and so the characterization of our nation states as “democracies” misrepresents what true democracy would actually be. But it would still be a dystopia to anarchists. “Rulership by the populace” is clearly a concept irreconcilable with “without rulership” unless one has atrophied to the point of accepting the nihilism of liberalism and its mewling belief in the inescapability of rulership. Or perhaps even going so far as to join with fascists and other authoritarians who silence their conscience with the ideological assertion that one cannot even limit power relations, only rearrange them.

Etymology isn’t destiny but it does carry a strong momentum and corrective force. I’m not sure why we should feel obliged to fight an uphill battle to redefine “democracy” in a direction consistent with anarchist aspirations. And in any case, from an abstract distance it seems wasteful to assign two terms to the same concept.

Those claiming that democracy and anarchy can be reconciled seem to either be rhetorical opportunists — gravely mistaken about what they can and should leverage — or else they seem gravely out of alignment with anarchism’s aspirations, treating “without rulership” not as a guiding star but a noncommittal handwave.

Perhaps this is today the regrettable consequence of a few decades of anarchist recruitment from activist ranks, a conveyor belt that has sadly often resulted in the most shallow of conversions. Rather than a fervent ethical opposition to rulership, we’ve often settled for merely instilling a mild distaste for collaboration with the existing state on leftists, sometimes going no deeper than “you want to accomplish X with your activism but have you noticed that the state is in your way?” This has led to generations of activists — many I count as close friends — who have never considered how they might achieve their standard collection of leftist desires like universal health care in the absence of a state. When pressed they invariably describe a state apparatus, squirming in recognition and cognitive dissonance. “Oh, sure I’m describing a centralized body wielding coercive force and issuing edicts, but it wouldn’t be, you know, The State… because, like, well it wouldn’t systematically kill black people at the hands of the police.” Such an anemic analysis of the state’s crimes never ceases to be shocking. Just as the gutless defanging of anarchism’s radical ethical hunger and dismemberment of its philosophical roots to a mere political platform is invariably depressing.

Let us be clear; if anarchy means anything of substance then many of these people are not really anarchists. At least not yet! They do not believe anarchy is achievable or even thinkable. And this is reflected in their own frequent aversion and/or equivocation in relation to the term “anarchy,” gravitating more to some positive associations they have seen made with it than the underlying concept of a world truly without rulership. Compared to our present society they want the things often associated with anarchism without the core that draws them. I was — for a time — hopeful that such individuals would move to the much more open term “horizontalist.” In truth they’d be better described as minarchist social democrats, who want a cuddlier, friendlier, flatter, more local and responsive state that makes people feel like happy participants and doesn’t engage in world historic atrocities.

Yet for those of us who have tasted the prospect of a world without rulership, this is simply a difference in degree of dystopia. If it truly were possible to achieve some kind of enlightened social democracy without wealth inequality, systematic disenfranchisement of minorities, and with some decentralization of state function, anarchists would still go to the barricades because this is not enough.

If anarchism is to mean anything of substance, it is surely not merely an opening bid from which you are happy to settle. Anarchy doesn’t stand for small amounts of domination: it stands for no domination. Although our approach to that ideal will surely be asymptotic, the whole point of anarchism is to actually pursue it rather than give up and settle for some arbitrary “good enough” half-measure. Such tepid aspirations is what has historically defined liberals and social democrats in contrast to us.

But it’s important to go further, because “democracy” doesn’t solely pose a danger of half-measures but also of a unique dimension of authoritarianism. A pure expression of “the rule of all over all” could be a hell of a lot worse than “Sweden with Neighborhood Assemblies.” The etymology itself seems to best reflect a nightmare scenario in which everyone constrains and dominates everyone else. If we seek to match words to the most distinct and coherent concepts then perhaps the truest expression of “demo-cracy” would be a world where everyone is chained down by everyone else, tightening our grip on our neighbors just as they in turn choke the freedom from our lungs.

To be sure few proponents of “democracy” specifically define it as “the rule of all over all.” There are many distinct dynamics that folks single out and focus on, but none of these definitions directly address the problem of rulership itself.

Democracy as Majority Rule

The most conventional definition of democracy among the wider populace is today quite rare in anarchist circles. At this point “majority rules” is rarely advocated by anyone in my experience outside some old fogies in the underdeveloped backwaters of the anarchist world like the British Isles, and its use in ostensibly anarchist meetings or organizations now rises to moderately scandalous. But it’s maybe worth reiterating that majority rule can be deeply oppressive to minorities. If 51% of your neighborhood committee votes to eat the other 49% alive, that’s a hell of a lot worse than a situation without majority rules where one person refuses to mow their lawn and thus unilaterally inflicts their malaesthetic on the rest of the neighborhood.

Proponents of such tyranny by the majority love to pretend that the only alternative is “tyranny by the minority.” But anarchist theory is all about removing the structures and means by which rulership can be asserted or expressed by anyone, majority or minority.

This is probably not the place to list them all like some kind of 101 course, but one example is superempowering technologies like guns that asymmetrically make resistance more efficient than domination. Such technologies are directly responsible for the increase of liberty over recent history. In an era where capital intensive undertakings like trained knights on horseback trumped anything else, you got rulership by elites; when the best weapons are one-kill-averaging soldiers, you just line up your troops and the one with the biggest count can be expected to win. But high-ammunition guns give every individual a veto against the lynch mob outside their door, allowing guerrillas to impede empires that vastly outscale them in capital. Technologies like the printing press and internet function similarly. And on the other side of the coin, the infrastructural extent and dependent nature of modern technologies of control or domination makes them brittle against resistance, easily prey to acts of disruption and sabotage. These tools — along with technologies of resilience and self-sufficiency — allow individuals to reject the capricious edicts of anyone, be they a minority or a majority.

Ideally anarchists seek to highlight and strengthen such dynamics with the political approaches we take, treating everyone like they have the most powerful of vetoes, capable of destroying everything, of grinding everything to a halt if they are truly intolerably imposed upon. This focus on individuals stops “the community” or other beasts from running rampant, forcing a detente tolerable for all parties. Such truces are far more likely to be attentive to the severity of individual desires, because “one vote per person” is incapable of reflecting just how much a person has at stake: something we could never hope to make objective and would be laughable to try to have a collective body legislate.

What norms fall out of such an assumption of veto powers are complex (and I’ve argued left market property norms are likely to be one) but at the center is always freedom of association. The consensus society is one primarily comprised of autonomous realms so that individuals can minimize conflict between their swinging fists and maximize the positive freedoms provided by collaboration. But note also the psychological norms. Majority rule treats people as means to whatever ends you want (rallying a large enough army at the polls), whereas a consensus detente can never lose sight of the fact that people are agents with their own particular desires. There is no subsumption of one’s subjective desires into merely being “one of the vote-losers”, a bloc rendered homogeneous and dehumanized by such democracy.

Okay agree some, but maybe we can say that consensus itself is democracy?

Democracy as Consensus

This is probably the most charitable way of framing “democracy” but here too are deep problems.

There’s a massive difference between consensus that’s arrived at through free association, and consensus that’s arrived because people are locked into some collective body to some degree. Often what passes for “consensus” within anarchist activist projects is merely consensus within the prison of a reified organization. Modern anarchists are still quite bad at embracing the fluidity of truly free association, and we cling to familiar edifices. Our organizations reassure us insofar as they function like the state, simplistic monoliths that exist outside of time and beyond the changing desires and relations of their constituent members.

Truly anarchist approaches to consensus would prioritize making the collectivity organic and ad hoc, an arrangement that prioritizes individual choice in every respect. Not just the prospect or potential of choice but the active use of it.

This would mean adopting an unterrified attitude about dissolution and reformation, learning new habits and growing new muscles that have atrophied in the totalitarian reference frame of our statist world. As it now stands, the prospect of going separate ways on a thing if we can’t reach consensus on a single collectively unified path strikes absolute fear into the hearts of most.

For consensus to be truly anarchistic we must be willing to consense upon autonomy, to shed off our reactionary hunger for established perpetual collective entities. Otherwise consensus will erode back in the direction of majority rules, individuals feeling obliged to tolerate decisions lest they break the uniformity of the established collective. Almost everyone of this generation is quite familiar with the general assemblies of Occupy that endlessly and fruitlessly fought over essentially just what actions would be formally endorsed under a local Occupy’s brand. Clearly in many cases we should have just gone our separate ways, working out not a single blueprint but a tolerable treaty to allow us to undertake separate projects or actions. The brand provided by The General Assembly was a centralization too far, creating such a high value real estate that everyone was obliged to fight to seize it. Surely anarchists should resist the formation of such black holes.

Okay, but regardless of the size and permanence of the collectives involved, maybe democracy is just collective decision-making itself?

Democracy as Collective Decision-making

While there are unfortunately many pragmatic contexts on Earth that oblige a degree of collective decision-making, it’s dangerous to fetishize collective decision-making itself.

Many young leftist activists get caught with a bug that suggests the core problems with our world are those of “individualism” by which they mean a kind of psychopathic self-interest that is inattentive to others. The solution, this bug tells them, is to do everything collectively. To stomp out anti-social perspectives by obliging social participation. If we all go to meetings together then we’ll become more or less friends.

The unspoken transmutation they appeal to is one where extraversion and being enmeshed in social interactions will somehow suppress selfish desires. Of course in reality the opposite is often true. The most altruistic people in the world are often introverted individuals who prefer to act alone and the most psychopathic predators are often those most at home manipulating a web of social relations.

Many leftists are scarred by the alienating social dynamics of our society and seek meetings as a kind of structured socializing time to make friends and conjure a sense of belonging to a community, but this is absolutely not the same thing as engendering a sense of altruism or empathy. If anything collective meetings are horrible draining experiences that scar everyone involved and only partially satiate the most isolated and socially desperate. Like a starving person eating grass, the nutrition is never good enough and so the activist becomes trapped in endless performative communities, going to endless group meetings to imperfectly reassure base psychological needs rather than efficaciously change the world for the better. (I say such cutting words with all the love and sympathy of someone who’s nevertheless persisted as an activist and organizer attempting to do shit for almost two decades.) Collective decision-making itself is no balm or salve to the horrors that plague this world.

But that’s not even the worst of it. Collective decision-making is itself fundamentally constraining. It frequently makes situations worse in its attempt to make decisions as a collective rather than autonomously as networked individuals.

The processing of information is the most important dynamic to how our societies are structured. A boss in a large firm for example appoints middle managers to filter and process information because a raw stream of reports from the shop floor would be too overwhelming for his brain to analyze. There are many ways in which aspects of the flow of information constrain social organizations, but when it comes to collective decision-making the most relevant thing is the vast difference between the complexity our brains are capable of holding and the small trickle of that complexity we are capable of expressing in language. As a rule, individuals are better off with the autonomy to just act in pursuit of their desires rather than trying to convey them in their full unknowable complexity. But when communication is called for it’s far far more efficient to speak in pairs one-on-one, and let conclusions percolate organically into generality. “Collective” decision-making almost always assumes a discussion with more than two people — a collective — in an often incredibly inefficient arrangement where everyone has to put their internal life in stasis and listen to piles of other people speak one at a time. The information theoretic constraints are profound.

If collective decision-making is supposed to provide us with the positive freedoms possible through collaboration, it offers only the tiniest fraction of what is usually actually possible. That there are occasionally situations so shitty that collective decisionmaking is requisite does not mean anarchists should worship or applaud it. And one would be hardpressed to classify something far more general like collaboration itself as “democracy”.

Okay, but maybe we can reframe democracy as an ethics?

Democracy As “Getting a Say in the Things That Affect You”

It got particularly popular in the 90s to frame anarchy as a world where everyone gets a say in the things that affect them. And for a time this seemed to nicely establish anarchism as a kind of unterrified feminism. But let’s be real: there are plenty of things that massively affect you that you should have no vote over. Whether or not your crush goes out with you should entirely be at their own discretion. Freedom of association is quite often sharply at odds with “getting a say over things that affect you.”

This may seem in conflict with the moral we drew from our discussion of consensus and the necessity to create a detente grounded in a respect for individual vetoes, but it’s important to remember that we weren’t settling for the naive first-order resolution where anyone strongly affected by something sets off a nuke. There’s a kind of meta-structure that emerges in any network of people upon consideration. The detentes we ultimately gravitate to involve certain more abstract norms, that are more generally useful to all than their violation in specific instances. Respect for freedom of association is one such very strongly emergent norm.

And in any case the goal of anarchists is freedom, we champion a decentralized world — among other conditions — precisely so that it might dramatically increase our freedom, not chain us down. This means at the very least cultivating a culture of live and let live when someone blocks you on Twitter rather than setting the world ablaze because you feel entitled to their attention.

Similarly if everyone in your generation starts using Snapchat — which you dislike — that puts you at a disadvantage: such an emergent norm clearly affects you in a negative way. But this doesn’t and shouldn’t give you cause to bring your peers before the city council and demand that Snapchat be outlawed. The norms of freedom of association, freedom of information, and bodily autonomy cleave out distinct realms of action that can affect third parties immensely yet should not — barring absolutely extreme situations — be dictated or constrained by them. Every invention and discovery changes the world but you don’t get to vote against the propagation of truth, however disruptive it might be to your life.

Okay, but maybe we can reframe democracy as not as any kind of system but as a demographic?

Democracy as “The Rabble”

In recent times David Graeber has re-popularized the historical association of “democracy” with large underclasses. And it’s true that in certain points in history “democracy” served alongside “anarchy” as a boogeyman of the horrors they were claimed would arise if the ruling elites lost their stranglehold on the populace.

Certainly we anarchists leap to defend the unwashed masses from those sneering elites. The prospect that the rabble would demolish the elites’ positions of power or get up to dirty and uncouth things with their freedom is something we embrace. But just because we despise those who despise “the rabble” doesn’t mean we should embrace any and all mobs or the concept of “the mob” itself. The positives that can be wrestled from this use of the term surely aren’t worth explicitly opening the door to “mobocracy”.

This archaic use of “democracy” has obvious subversive potential in our present world, flipping the positive affect built around “democracy” by our current rulers and returning it to those in conflict with them. But anarchists are not blind proponents of “the masses” in any and all situations, something this rhetorical opportunism would lock us into. The masses can be horrifically wrong, and what is popularly desired can be quite unethical. It’s not vanguardism to resist pogroms or work to thwart the genocidal ambitions of majorities like in Rwanda. There are endless examples of “the masses” seeking to dominate, and our goal as anarchists is not to pick sides but to make such rulership impossible or at the very least costly.

Anarchists aren’t engaged in team sports; while we often defend underdogs in specific contexts, we’re not out to back one demographic against another in any kind of fundamental way.

Okay, but does “democracy” still have a role as a transitory state?

Democracy as a Transitory State

This is a complicated issue because obviously it depends on a host of abstract and practical particulars. We’ve covered a lot of different definitions one encounters among apologists for “democracy” in anarchist circles, and what I’ve tried to highlight among all of them is both a lack of any explicit anti-authoritarianism as well as a series of lurking problems that risk warping things in an authoritarian direction.

In some situations, certain things going by the name “democracy” would likely pose half-steps in the direction of anarchism. The replacement of a feudal lord with a village assembly would almost certainly be an improvement. We can get distracted with concerns about possible failure modes and lose sight of what’s actually happening on the ground. Just because the democratic processes of Rojava could theoretically bend in a more sharply nationalistic or racially oppressive direction doesn’t mean that they actually are. There are many situations where participatory democracy represents a major step forward, even something anarchists should fight for with our lives.

But when democracy is idealized — when it’s generalized or elevated as an ideology rather than as a pragmatic strategy in a specific context — things gets dangerous. The risk of such idealization is inherent to its use. And oftentimes democracy serves as a half-measure that actually impedes further progress. The Chomskyian strategy of compromise and “incremental steps” that secure bread today can actually further entrench power structures while providing minor ameliorations.

Democracy is in almost every definition a kind of centralization and such centralization pulls everything under its control. Just as with other types of states, once you establish a centralized system with far-reaching capacity it starts to become more efficient for individual agents to try to do everything through the state: to capture it for your ends rather than working to build solutions from the roots up outside of it. Even those with sharp anarchist ideals start feeling the pressure to go to the General Assembly rather than doing things outside of it as actual agents.

Like shooting people, in our messy and deeply dystopian world democracy may sometimes be necessary and strategic, but as anarchists our every inclination and instinct should be to avoid such means by default, to only cede to them kicking and screaming, and never cease feeling distaste. We must not lose sight of our ideals and even as we can only asymptotically approach them we must still attempt to asymptotically approach them rather than asymptotically approaching some halfway point.

And of course let us not forget that a world where say a social democrat like Bernie Sanders or Jeremy Corbyn gets their way might even actually end up worse than our present horrorshow. Liberal and socialist policies have a long history of making worse the things they were supposedly out to fix.

Okay, but isn’t that unfair since the whole point is direct democracy?

A Note About “Directness”

It’s annoying how often young activists attempt to create a spectrum of democracy with varying levels of mediation or representation that places anarchy as synonymous with the most direct democracy. It’s true that depending upon a representative to speak on your behalf is an insanely inefficient approach — anyone who’s dealt even just with spokescouncils pooling few dozen people knows this. We know that due to the shallow bandwidth of human language, conversation itself is ridiculously inefficient at a means of conveying the fullness of our internal desires and perspectives, so delegating to someone else with only the vaguest of outlines of what you want is surely much worse.

But what I find particularly pernicious about the reduction of anarchism to a mere “direct” qualifier on “democracy” is that it plays into a fetishization of immediacy that has already ideologically metastasized among anarchists, indeed often among those more insurrectionary or individualist figures on the other side of the debate over “democracy”. The issue with representation in my mind isn’t the lack of immediacy but a matter of limits to the flow of information. It’s a subtle but crucial difference.

A number of anarchists or former anarchists have in recent years increasingly grown to treat immediacy as the secret sauce — the very definition of freedom. This stems from a philosophical confusion over what freedom is and a very continental or psychological focus upon emotional affect, focusing on a phenomenological experience they associate with “freedom” — that is to say a kind of spontaneity or impulsive reaction rather than reflection (since in our present world reflection often brings to attention just how constrained we actually are). To consider an action is precisely to chain it through a series of mediations, to filter and parse it. It’s important to note that the reactionary approach smothers one’s internal complexity, ultimately reducing an agent to a mere billiard ball. When treated as an ideal, immediacy necessarily involves the suppression of consciousness and thus of choice.

The problem with collective decisionmaking isn’t that the discrete deliberative bodies involved process information or ponder choices, but that such arrangements are ridiculously inefficient at it compared to individual autonomy: an embrace of the full agency of their constituents. A more organic network of reflective individuals would provide more choice — that is to say more freedom.

Against All Rulership, Always

To people in the trenches just trying to grab whatever weapons they find useful, all this philosophical criticism of “democracy” no doubt appears to be an ungainly impediment. But anarchism is not a pragmatic project myopically concerned only with what can be won here and now. Our most famous triumphs have been our foresight — often our predictions of dangers to come from various stripes of “pragmatism” and “immediacy.” Anarchism is a philosophy of infinite horizons, taking the longest and widest possible scope. An ethical philosophy of stunning and timeless audacity, not some historical artifact trapped in a limited set of concerns. This sweeping consideration is what enabled us to correctly predict the failures of Marxism, and it’s a tradition worth maintaining. Bakunin’s denouncement of Marx took place in a context long before Kronstadt and all the atrocities that would eventually become popularly synonymous with Marxism. Such “abstract philosophy” and non-immediacy split the ranks of those fighting against the capitalist order, weakening what they could bring to bear in the service of workers’ lives that very minute. And yet the world is clearly all the better for it. Thanks to the anarchist schism with Marxism, the struggle for freedom was able to survive.

I’m not saying that a system of direct democratic town councils are going to be set up somewhere in the world tomorrow under the banner of “direct democracy” and turn genocidal or into some kind of totalitarian small town nightmare, but every take on “democracy” is nevertheless pretty distant from anarchy and thus unlikely to stay true. When your ideal isn’t pointed at freedom itself it’s only a matter of time before the runaway compounding processes of domination warp its path.

I am, at the end of the day, happy to grimace slightly and move along when some comrade I’m working with spouts something about “more democratic than democracy!” just as I’m capable of biting my tongue with the sincere but confused trapped in Marxist or anarcho-capitalist languages. Semantic battles are not the be-all and end-all, but attempts to appropriate the general goodwill towards “democracy” have yet to latch onto any underlying concepts worth validating. It seems to me that a far better practice is to stick somewhere close to the etymology of the word (the rule of all over all) and its near universal associations (majority rule).

One might object on the semantic grounds that it’s better to assign our words to their most positive possible interpretations, but I do think it’s important to have words for bad things, to be able to describe the array of possibilities we oppose with any sort of detail. It’s important to be able to see and comprehend the various flavors oppressive systems can take. Even if we don’t presently live in a full-blown democracy with all the horrors of a true domination of all over all, it’s still an illuminating extreme and one that I think warrants highlighting.

Anarchism’s uniqueness is that it doesn’t seek to equalize rulership but to demolish it, a radical aspiration that cuts through the assumptions of our dystopian world. Anarchism isn’t about achieving a balance of domination — assuring that each person gets 5.2 milliHitlers of oppression each — but about abolishing it altogether.

2. Democracy, Anarchism, & Freedom (Wayne Price)

June 3rd, 2017

“As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.”

—Abraham Lincoln

“Democracy” and “anarchism” are broad, vague, and hotly contested terms. Even if we stick to specific definitions, there are still arguments about what these definitions mean in practice. (Lincoln’s quotation, above, seems to be about the preconditions for democracy.) This is not just a linguistic dispute. The argument is not just over “democracy” but over democracy, not just over “anarchism” but over anarchism. Still more controversial is the relationship between these two broad terms.

I will use the definition of “democracy” as “rule of the commoners”—a definition going back to classical Greece. The “commoners” were both the majority of the population and the lower classes (of free, native-born, males, in ancient Greece). By “anarchism” I mean total opposition to the state, to capitalism (but not necessarily to the market), and to all other forms of oppression. This is pretty broad, but it rules out “anarcho-capitalists,” not to mention “national anarchists” (fascists).

On the relation between anarchism and democracy, anarchists have held varying opinions (those who addressed the issue, anyway). Many reject “democracy.” Mainly they make two arguments. One is that “democracy” is the official ideology and rationalization of most capitalist states today. They do not wish to support this ideology, the main justification for the modern state. Instead, they wish to expose it and oppose it, advocating “anarchism” as the goal. (They do not necessarily deny the advantages of living under a capitalist democracy, as opposed to fascism or Stalinism, say. But they point out that even the best capitalist democracy is still really a form of rule by an elite minority of capitalists and their agents.)

The other main argument raised by these anarchists is that anarchism, by definition, rejects all forms of domination. This means domination of the many by the few, but also of the few by the many (the “commoners,” the working class, the “people”). Since “democracy” means a form of rule, then anarchists must reject it, they argue.

Anarchism is Democracy without the State

However, there are other anarchists who regard themselves as supporters of democracy. They claim that anarchism is the most extreme, radical, form of democracy. This is my view (I have written two essays on this topic; see Price 2009; 2016). I see both “democracy” and “anarchism” as requiring decision-making by the people, from the bottom-up, through cooperation, clashes of opinion, social experimentation, and group intelligence.

But “democracy” means collective decision-making. It does not apply to matters which are of individual or minority concern only, such as individual sexual orientation, religion, or artistic taste. Free choice should rule here, whatever the majority thinks.

Democratic anarchists recognize that “democracy” is used as an ideological cover for the rule of a capitalist elite (it is still the “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie”). The ideal of “democracy” is contradicted by the reality of the state and capitalism. In fact, the capitalists have never lived up to their “democratic” program. This contradiction could be used to challenge the system, to expose its fraudulent claim to be “democratic,” to justify opposition to the real state. Almost no one in the U.S. is for “anarchism” or even “socialism,” but almost everyone is “for” “democracy.” Why not use the ideal against the reality?

Actually the capitalists limit their claim of “democracy” to the government apparatus. They do not claim that their economy is democratic. Instead they justify their corporations (totalitarian in their internal organization) by using the rationalization of “freedom,” specifically the “free market.” Anarchists make a revolutionary challenge to capitalism by advocating a democratic economy. (For example, a federation of worker-run industries, consumer co-ops, and collective communes.)

Even those anarchists who reject “democracy” because of its ideological use by the capitalists usually advocate “freedom” or “liberty.” But these terms are just as much ideological watchwords of capitalist society, used constantly to justify its un-free reality. If it is all right to use “freedom” against the false proponents of freedom, then it is all right to use “democracy” against the pretended advocates of democracy.

Secondly, these anarchists deny that anarchism contradicts “democracy” in principle. They point out that virtually all the anti-“democracy” anarchists advocate “self-rule,” “self-governing,” and “self-management.” These terms are no different than “direct democracy” and “participatory democracy.”

If everyone is involved in governing (participatory democracy), then there is no government—no special institution over society which rules people. Anarchists are not against all social coordination, community decision-making, and protection of the people. They are generally for some sort of association of workplace committees and neighborhood assemblies. They are for the replacement of the police and military by an armed people (a democratic militia, so long as that is necessary). This is the self-organization of the people—of the former working class and oppressed population, until the heritage of class divisions and oppression has been dissolved into a united population.

In short, what anarchists are against is not social organization but the state. The state is a bureaucratic-military socially-alienated organization of special forces (professional politicians and armed people). It stands above and against the rest of society. Anarchists want to abolish the state. They do not believe in the possibility of a “transitional state” or a “workers’ state.” The self-organization of the people, through popular assemblies and associations, needs to be democratic (self-managing). Anarchism is democracy without the state. The people themselves must be able to manage all of society from below.

Does Democracy Require Domination?

Does this radical democracy still mean the coercion or domination of some people by others? Let us imagine an industrial-agricultural commune under anarchism. Some member proposes that it build a new road. People have differing opinions. A decision will have to be made; either the road will be built or it won’t (this is coercion by reality, not by the police). Suppose a majority of the assembly decides in favor of road-building. A minority disagrees. Perhaps it is outvoted (under majority rule). Or perhaps it decides to “stand aside” so as not to “block consensus” (under a consensus system).

Is the minority coerced? Its members have participated fully in the community discussions which led up to the decision. They have been free to argue for their viewpoint. They have been able to organize themselves (in a caucus or “party”) to fight against building the road. In the end, the minority members retain full rights. They may be in the majority on the next issue. (Of course, dissatisfied members may leave the community and go elsewhere. But other communities also have to decide whether to build roads.)

The minority may be said to have been coerced on this road-building issue, but I do not see this situation as one of domination. It is not like a white majority consistently dominating its African-American minority. In a stateless system of direct democracy, all participate in decision-making, even if all individuals are not always satisfied with the outcome. In any case, the aim of anarchism is not to end absolutely all coercion, but to reduce coercion to the barest minimum possible. Institutions of domination must be abolished and replaced by bottom-up democratic-libertarian organization. But there will never be a perfect society. This is why I began by defining “anarchism” as a society without the state, capitalism, or other institutions of domination.

Conclusion

These issues are of vital importance under the Presidency of Donald Trump, with its right-wing direction, and the fierce fight-back against it (the “Resistance”). Supporters of Trump claim his right to attack the people and the environment due to his election—this is “democracy” they say. But his popular opponents also appeal to “democracy” in order to de-legitimize him (“Not My President!”). They note that he lost the popular vote, that there was voter suppression of People of Color, and interference in the election by the FBI and by Russian agencies. But their political strategy is still electoral, to elect Democrats. This is an excellent time for revolutionary anarchists to identify with the fight for democracy, even while rejecting the supposedly “democratic” capitalist system which brought Trump about.

There are broader questions of anarchism and democracy which I am not discussing here. How to form effective federations and networks while still rooting them in face-to-face democracy in the workplace and community? How to resolve conflicts of interest and opinion through intelligent discussion? Such issues will be dealt with pluralistically through experience and experimentation. A society based on radical democracy and freedom will not be perfect. But it will give humanity a chance to live productively, freely, and happily.

References

Price, Wayne (2016). “Are Anarchism and Democracy Opposed? A Response to Crimethinc”: https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/wayne-price-are-anarchism-and-democracy-opposed

Price, Wayne (2009). “Anarchism as Extreme Democracy.” The Utopian: https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/wayne-price-anarchism-as-extreme-democracy

3. Democracy: Self-Government or Systemic Powerlessness? (Derek Wittorff)

June 4th, 2017

Democracy: the universal war cry of justice. We’re told by the left — both moderate and radical — that all socio-political problems almost always arise from a pure lack of democracy. We’re told all social manifestations of authority, inequality, and hierarchy require democracy as a political solution. If there happens to be some kind of democracy in a society, and there remains the problem of hierarchy, the problem is always attributed to there not being direct democracy, or that there isn’t free association between individuals and collectives. Either representatives of an indirect democracy are corrupting the very function of the system, and acting in their own personal interests (which is generally how republican systems devolve into a plutocracy), or the freedom of others to leave the collective if they don’t like it, ironically the “like it or leave it” motto usually held by conservatives when addressing political dissidents and immigrants, isn’t being upheld and enforced.

Most libertarian socialists tend to believe that freedom of association, or decentralism, is a cornerstone of a well-functioning democracy. They believe that individuals must first consent to the democratic decision-making of the collective by association, and that the potential choice to disassociate rules out the imposition of such majoritarian decision-making on the minority. At first glance, this appears to be fairly reasonable and consistent with libertarian socialist criticisms of the State. However, what is grossly overlooked are the internal dynamics of democracy and fundamental inquiry as to whether democratic organizing principles per se are libertarian and egalitarian in nature. Does freedom of association institutionally prevent the majority forcibly expropriating the power of the minority? Is democracy technically anarchist?

Anarchy, by definition, means “no rulers” or self-rulership in the most distributed sense: rule of each by each (“each” according to anarchist sociology includes both collectives and individual persons). It is the political opposition to all social hierarchy and centralized authority. Democracy is by definition “rule of commoners” which is assumed to be personified by the majority (i.e. rule of all by the majority). I believe that these two forms of decision-making are irreconcilable. Anarchist sociology (adhering to Proudhonist theories of individual sovereignty, collective force, social contract, and federation) while being heavily influenced by classical liberal notions of free association, ultimately went further in its social analysis to conclude that “the people” was too general a concept and didn’t involve enough individual and collective sovereignty necessary for freedom from the State. Collectives and persons may be individual products of “the people” as this monolithic concept of the masses, but recognizing the autonomy of each to determine how best to compose “the people” was key in the formulation of anarchist notions of justice, equality, liberty, freedom, peace etc. The liberal notion of “the people” can just as easily include a minority of politicians, military personnel, and capitalists as much as it attempts to exclude them, in the name of granting commoners power, because of failed liberal institutional analysis of State and Capital. As Proudhon critiqued in Solutions to the Social Problem[1]:

“The sovereignty of the nation is the first principle of both monarchists and democrats. Listen to the echo that reaches us from the North: on the one hand, there is a despotic king who invokes national traditions, that is, the will of the People expressed and confirmed over the centuries. On the other hand, there are subjects in the revolt who maintain that the People no longer think what they formerly did and who ask that the People be consulted. Who then shows here a better understanding of the People? The monarchs who believe that their thinking is immutable, or the citizens who suppose them to be versatile? And when you say the contradiction is resolved by progress, meaning that the People go through various phases before arriving at the same idea, you only avoid the problem: who will decide what is progress and what is regression? Therefore, I ask as Rousseau did: “If the People have spoken, why have I heard nothing?””

Anarchism seemingly radicalized the concepts of free association and decentralization to its logical extreme and therefore destroyed the theoretical legitimacy of a liberal democratic State.

Many anarchists believe, particularly after the hegemonization of anarchist communism after the Black International, that anarchy (rule of each by each) was best expressed by communism (rule of all by all), and that some form of democracy is de facto necessary to synthesize both communism and anarchism. However, the practice of communism, if not politically consistent with anarchism, may conflict with anyone’s conception of liberty, equality, freedom, unity etc. That’s why I believe that democratic measures fail to reconcile the two philosophies. Not everyone could have access to the capital of everyone else at any given time. There would be unresolvable conflicts that only a bureaucratic ruling class, practically absolved from all blowback of its imposing statecraft, could try to solve by forcing others to share and be subordinated to the Collective Democratic Will. Nonetheless, as all anarchists know, that process of centralization institutionalizes unresolvable social conflicts that inevitably ends in war. Authoritarian communism has proven a historical and ethical failure.

In my opinion, there seems to be a theoretical antagonism between the idea of communism and decentralism, particularly if democracy is the governing principle aimed at developing some kind of synthesis. To give anarchist communists some credit, not all support democracy, and even those that do maintain a belief that this community would be approximated by means of federalism. “Full communism” is indeed an ideal that cannot be immediately and perfectly attained, and democratically operated collectives would eventually federate to and break down conventional barriers to access between collectives to best attain it. I criticize this practice based on the topic of this paper. Simply put, democratically operated collectives wouldn’t be able to federate in a way that destroys all barriers to access because the power dynamics of democracy internal to a collective maintain a different set of barriers to access. Namely, the barriers to access would be drawn between the activity and resources of the minority and the majority when a certain proposal is adopted, a given direction solidified, and a collective goal determined. This is essentially systemic powerlessness, a distinct form of oppression, and federating those systems institutionalizes the barriers on a massive scale to the virtual effect of a State. Freedom of association is not a remedy for power dynamics internal to a collective; it is only a remedy for those power dynamics shared between collectives. Free consent, or giving permission to be ruled, is not the same as mutually agreeing upon how to rule ourselves, or freely choosing to rule oneself. Majoritarianism is hierarchical and antithetical to anarchy, and no amount of decentralization can change that.

It seems that the anarchist notion of radical decentralization may have delegitimized the idea of the liberal democratic State, but it didn’t necessarily go so far as to delegitimize the idea of democracy in our minds altogether. Maybe our ideas of decentralization weren’t radical enough: an idea I’ll explore later in this piece. Even in the absence of the State — a centralized monopoly on oppressive violence — the idea that freedom of consent alone necessarily presents the greatest degree of anarchy within a democratically operated collective is totally absurd. Ironically, this argument sounds like the “anarcho-capitalist” narrative that capitalist hierarchies are fully capable of being anarchist if they are not enforced as the dominant mode of organization by the State. This narrative holds that competition (i.e. free association with some capitalist connotations) on the free market ensures that no one would be forced to join a business through some kind of state, and that this somehow means that absolute authority of the capitalist over their wage-laborers, in the specific context of that capitalist business, or within the territorial monopoly on oppressive and violent force of the capitalist’s property, is technically anarchist. Nevermind whether competition eventually dissolves capitalist businesses because of economic inefficiencies; this is clearly wrong on a political level, because hierarchy exists within that specific context of the business and property. No hierarchy can be a logically professed option, or conscious practice, of anarchist philosophy because hierarchy and anarchy are not reconcilable. Libertarian socialists recognize this, and criticize “anarcho-capitalists” on this front. However, I’ve found that certain libertarian socialists are incapable of applying this same logic to their own mode of decision-making. Even without the oppression of violence, democracy suffers from the oppression of powerlessness that prohibits and expropriates the power of each and all to determine the specific combination of labor, capital, and talents that is decidedly best for each and all. That powerlessness may reinforce the need for other kinds of oppression such as violence, exploitation, cultural imperialism, marginalization, etc.

When backed into this corner, libertarian socialists of all kinds will argue that democracy is less hierarchical than a capitalist business, and that even the worst cases of a 51-49% margin are still less unilateral than a capitalist doing anything they want without the say of their workers. This may be true. However, a person can be on the losing side of a vote 100% of the time. This might not be a normalcy, but this is a possibility inherent to democracy. Even if not everyone is a member of the minority, the minority is ruled by a majority. Whatever the circumstances may be, this is a socio-political hierarchy, and the degree of unilaterality doesn’t change that. The vote of the minority might be organizationally involved but their vote has had no effectual impact on the operation of the group when the majority forms. Obviously, most people won’t be on the losing side of the vote all the time, but since it surely happens some of the time it reveals that direct democracy isn’t so much the dissolution of social hierarchy as the continuous shifting and alternation of who composes the majoritarian hierarchy.

This kind of formal hierarchy ultimately reinforces informal power dynamics as well. People who are normally on the winning side of a vote can develop their own subgroup, forming a majoritarian tendency that antagonizes the minority voters to follow their rule. There can be an informal power dynamic of silencing the dissent of those who have an equal vote. Proposals may not even reach the table if some folks don’t feel empowered enough to propose them in the first place because some winning majority and collective direction has been normalized. This reveals a false assumption that votes necessarily indicate the full participation of everyone because there’s more to decision-making than voting on proposals that were informally pre-constructed by the majority. This is often how workers in capitalist workplaces forget how economy functions for each individual, which reinforces the outrageous belief that the organization they’re employed in is just a social body that operates for the sake of itself separately from the interests of each of those within that “unity collective”[2]. Democracy doesn’t appear to fully recognize and change that condition. Many radicals will scoff at this point and tell me that if someone doesn’t like the group’s direction, they can find another one they do like, or essentially just bite the bullet and internalize the costs of the majority’s decisions for the sake of collective action. They defect to the free association argument. But like I’ve said, consenting to a mode of decision-making does not change the very structural nature of that decision-making process per se.

Many are probably wondering what I propose for decision-making in the context of collective action. Surely anarchy as the “rule of each by each” cannot be individualist in the sense of atomizing each person, as if they’re isolated beings! It’s obvious that each individual is born from a social context with complex relations that progressively develop their personhood, conditions, groups, organizational forms, etc. The alternative would be the flawed (and indeed it is) Crusoe economics of Austrian and classical political economy!

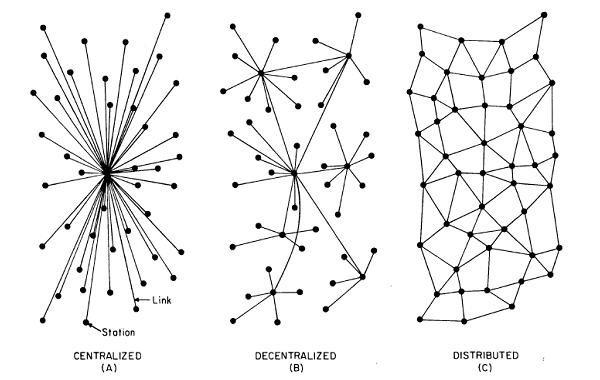

Well, I propose consensus. There are probably cries of opposition from all directions: “consensus doesn’t work in large groups,” “it takes too much time and energy to develop consensus on every decision,” “consensus suffers from the same informal power dynamics of a core group that you mention about democracy,” and more. In reality there are many forms of consensus — many of which are problematic — but I think that some forms are very broadly applicable to most economic functions of a society where politics is not the institutionalization of oppression, or the exercising of power and manipulation, but rather the mutual process of liberation and freedom. To interject here, an individual and federal model of consensus-based groups also outlines a conceptual distinction between historical notions of anarchist decentralism/federalism (often involving democratically elected delegates of groups and regional federations up to international congresses) for a potentially more theoretically coherent notion of distributism, illustrated here:

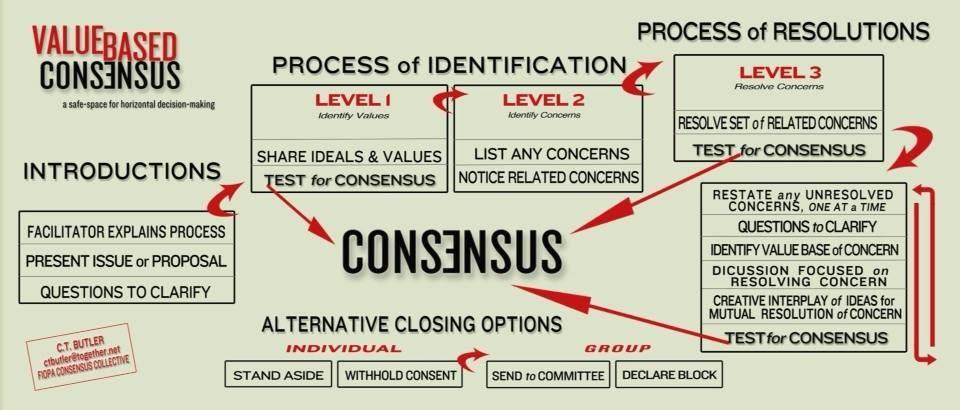

That being said, consensus processes can become hierarchical[3], and to that extent of course antithetical to anarchy, but I think there is fundamentally more room for experimentation. Let’s imagine that an informal power dynamic within a consensus-based group practically forms and subordinates either a minority or majority to the will of authoritarians, or forcibly pushes certain individuals out of the association by the barriers to access created by its social hierarchy: for example, because of some kind of white toxic masculinity discouraging the participation and membership of women and POC. At least this power dynamic is not being crystallized as it would be under the mechanisms and structure of some democracy! Not all consensus models practically become hierarchical, which cannot be said about democracy. That being said, small affinity groups can easily be inclusive and reach consensus without the necessity of formal structures preventing conflicts from breaking down communication, goals, or agreements on proposals. Individuals and even subgroups can break off from the initial group to pursue their own goals. This breaks down the very notion of formal organization, and makes informal organization an obviously important tool for anarchists. However, when certain goals require large-scale organization, and no matter the goal we do not want to sacrifice our principled support for anarchy, I propose a specific form of consensus known as “formal values-based consensus”, or “formal consensus.” This was most notably adopted by Food Not Bombs[4]: arguably the largest and most effective anarchist project in recent history.

A few years back I had the pleasure of meeting C.T. Butler (a cofounder of Food Not Bombs) who formulated the formal consensus model in his book “On Conflict and Consensus”[5]. We discussed the history of Food Not Bombs, the common problems identified with various consensus models (such as the Quaker model used by 1970’s anti-nuclear activists and David Graebers “modified consensus” which was often used during the Occupy movement), and the dimensions of his model and how it attempted to resolve those problems. The central problem that he found in most consensus-based groups, which has become the common critique among proponents of direct democracy, is the lack of participation that creates a core group and system of minority rule. This is largely caused by the ability of any one person to block a proposal, coupled with the group’s value for unanimity often promoting discussion but not resolving to consensus. There’s also the problem of repressing certain conflicts, which causes problems down the road. This institutionalizes conflict, and creates an environment of exclusiveness, competition and secrecy. C.T.’s solution was to create more procedural mechanisms designed to facilitate the greatest amount of participation, promote extreme clarity on the unified collective goal, and foster agreement on new proposals. The more effective these mechanisms, the greater the amount of participation there would be, therefore ensuring the horizontal, inclusive, transparent, and effective nature of the process. I won’t go through all the details, so here’s a depiction of how the process works:

It may seem fairly complex, but I won’t argue too much about the details here. Not coincidentally, oftentimes the disadvantage to this model is having everyone understand the process and underlying agreements of the organization (i.e. high compliance costs and barriers to entry). I’ve made my criticism of democracy partially about internal barriers to entry/access, but those barriers are constructed by the hierarchy between the majority and minority. In the case of formal consensus, its barriers to entry are not the result of hierarchy, but instead the nature of self-management: at least self-management associated with the highly skilled workforce and complex division of labor of a large-organization. Formal consensus simply reveals the real costs of individual responsibility and self-management in large organizations. As anarchists, that’s a cost we’d be willing to pay for freedom. And why complain? The costs are arguably less than a democracy with its institutionalization of conflict, exploitation of the minority, lack of freedom, and other issues. Down with democracy!

4. The Linguistics of Democracy (Alexander Reid Ross)

June 5th, 2017

Democracy is a word that evokes an array of affective responses depending on time, place, and people involved. For the Patriot movement, democracy stimulates a constellation of ideals, values, and principles. People who view the Patriot movement’s adherence to such forms as hypocritical might attempt to recuperate the term or abandon it entirely. To decipher the usage of democracy in everyday discourse, we must first plunge into the phenomena of words, concepts, and ideas in efforts to understand and properly define it. The following admission must be made: I use terms for practical purposes but with intent, recognizing that their meanings as defined in this essay cannot be seen as universally understood. Suffice it to say that they are adequate to the facts of this piece but should not be seen as their only conceivable usage. Words are useful in context and must not be made into altars. This is, perhaps, the first principle of understanding the word “democracy.”

Most people will agree that the world exists to us insofar as we can perceive it. That it is not a formless soup of undifferentiated matter, existential phenomenology tells us, is due to our ability as a species to discern one thing from another. Such discernment can be driven largely by the evolutionary form our species has taken. For example, I cannot keep my eyes open or breathe underwater. At the same time, discernment can be intentionally conditioned through cultural practice and repetition, like “acquired tastes” such as wine.

The ability to perceive distinction and recognize things as our senses perceive it certainly remains within the domain of the subjective. To this world of the affective is typically assigned the word, “notion.” If one has a notion of something, one feels it intuitively. Only together through experience and common notions can we agree upon a baseline existential-perceptive reality. It is through the affective, the sensual—the accepted as well as the rejected—that we understand the world of things as a world of objects that can be put to use. This public motion toward cooperative fellowship is typically linked to the “idea”—a momentous event where our consensus reality intertwines subject and object to recognize the utility of things and their consequences. As we gather ideas and accumulate knowledge based on consequences to our actions, we develop concepts or “frameworks” through which we interpret the world and clarify our understanding of its workings and ours.

Lastly, we come to that which is called “the truth.” The truth is not a statement of objectivity, it is an expression of a reality that has been socially produced. Here I disagree with the French philosopher Alain Badiou who, in the Heideggerian vein, approaches the truth event as an act of destruction that returns the subject to a pre-reflective condition of emptiness. Rather, it is my understanding that the truth presents simply an affirmative statement or group of statements that correctly articulate the premise on which social reality is produced. Hence, truth becomes a matter of constant negotiation over experiences superior and inferior, desirable and undesirable. It might be ably said that truth is the method of inquiry that recognizes fact from fiction and seeks to use knowledge toward the advancement of others as well as one’s self, or, as Turcato calls anarchism, “the method of freedom.”

Here, truth becomes a dialectical phenomenon of human experience relatable to the universality of fact on the basis of humanity’s long and short term desires. It is, then, a way of living more than a strict observation. A way of living considered true and accepted for its providential merit is considered a principle. The consensus about reality is constantly tested through art, which really is nothing less than that which makes us what we are. The consensus about truth lies in the realm of philosophy. The consensus about principles lies in the domain of the political.

The first philosopher in European history to truly understand these terms was Aristotle, because he recognized that people’s equal potential to know the truth and to follow right principles, which return to a subject who knows what they want and want the right thing. Aristotle identified politics as the act of being together in the city and identifying as a political community. People form mutual associations and “political friendships” on the basis of common agreements on the experience of life and happiness. The mutual benefit of collaborative labor binds the city in practical thought and turns it toward logical administration. As city life unfolds in its beautiful reasoned chaos, its appreciation reaches the philosophical, from which it can be theorized as a whole, a la Jane Jacobs. Democracy, for Aristotle, becomes the sum total of theory, which we have understood as the sublation of notion, idea, concept, and principle.

We must remain critical of the Aristotelian tradition, of course. Though he is roundly critiqued for believing slavery to be a consequence of inferior will, Aristotle also insisted that democracy cannot truly exist in a state of slavery, and that democracy manifests the superior form of human political participation. I will not defend the Ancient Greek understanding of slavery, save to point to Frantz Fanon’s deliberation on the “master-slave” dialectic in which the philosopher identifies liberation through self-emancipation.

The most important thing to point out in Aristotle, rather, is his sexism and classism. Enfranchising class divisions within the city, Aristotle automatically pitched experiential equality into the crisis of economic inequality. The basis for this failure of economic and political thought lies in Aristotle’s assessment of women as lacking the logos of politics. Women’s authority belonged in the oikos, the household, from which we receive the root for our words economy and ecology. Women cared for the running of the household, its economy and relation to the outside, while disturbingly men sought socio-political status often through pedophilia. If, as Marx claimed, man is not a political but first a social animal, it is crucial to recognize even in Marx the placement of oikos and economy at the root of social intercourse.

What Aristotle and his tradition leaves us with, then, is a problematic theory of democracy that contributes to both its critique and rectification. If Aristotle’s understanding of democracy is plagued by patriarchy, it is also a decisive defense of human equality. The hypocrisy here should aggravate any believer in truth, given our understanding of truth as a way of living that closest resembles what we understand to be factual, accurate, and of positive consequence to our community. In Theory of Democracy, Giovanni Sartori states, “Aristotle defined a stateless, direct democracy,” yet even here we recoil from such a thing where it is dominated by patriarchy.