Lewis Borck, Matthew Sanger

An Introduction to Anarchism in Archaelogy

Archaeologists are increasingly interested in anarchist theory, yet there is a notable disconnect between our discipline and the deep philosophical tradition of anarchism. This special issue of the SAA Archaeological Record is an attempt to both rectify popular notions of anarchism as being synonymous with chaos and disorder and to suggest the means by which anarchist theory can be a useful lens for research and the practice of archaeology.

Popular notions of anarchists and anarchism can be found in movies, television shows, and a variety of other media. In many of these representations, governments collapse and violence erupts when society attempts to operate without leaders. While the Greek root of anarchy is an (without) arkhos (leaders), this does not necessarily entail lack of order. Indeed, the Western philosophical tradition of anarchism was born out of an interest in how individuals could form cooperative social groups without coercion. Instead of chaos being implicit, anarchism assumes a level of order and cooperation among consenting parties.

Interest in voluntary organization has a lengthy history (Marshall 1992) and predates the first use of the term anarchism in Western thought. However, by 1793 Godwin published Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and Its Influence on General Virtue and Happiness and discussed how an anarchist society might be organized. This was followed by Kant’s 1798 definition of anarchy as a form of government entailing law and freedom without force in Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. But the term was not formalized until Pierre Joseph Proudhon’s 1840 book, What Is Property? An Enquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government. Eventually the word anarchism was popularized by Mikhail Bakunin and others in the 1800s.

In reaction to the rising authority of the capitalist elites in Europe, anarchists, specifically Proudhon and Bakunin, argued that the average individual was quickly becoming subsumed under the industrialist state and that human freedoms were being lost to authoritarian rule. Anarchism, said Proudhon and Bakunin, was the rejection of elitism and authoritarianism and the creation of a new social body where “freedom is indissolubly linked to equality and justice in a society based on reciprocal respect for individual rights” (Dolgoff 1971:5).

If this seems similar to Marxist socialism, it’s because the two exist on a continuum with anarchism as a libertarian form of socialism on the end opposite Marxism (Chomsky 2005:123). Both Proudhon and Bakunin were correspondents, if not friends, with Karl Marx until an eventual falling out between the two philosophical camps. While Marxism and anarchism were both concerned with the formation of fair and just societies where individuals were not alienated from their labors and could live their lives free from the oppression of an elite class, anarchism understood power as emerging from a range of factors, only some of which were the economic and material principles favored by Marxists.

Perhaps more importantly, the two also differed on how best to transform society. In contrast to Marxism, in which revolution proceeds in stages and relies on state authority to enact the eventual transformation into communalism, anarchism requires that liberation proceeds in a manner that reflects the end goal—meaning state-level authority had to be rejected from the outset. This grew from the anarchist idea that societies are prefigured, which is to say they emerge from the practices that create them. Instead of the ends justifying the means, anarchists believe that that the means create the ends. But also that the means in some way are the ends. The two are simultaneous. The ends are process.

Although long disregarded by most academics (and the history of how Marxism flourished while anarchism did not is an interesting one), anarchist writers have built up an impressive body of work over the last 200 years. As an anti-dogmatic philosophy, anarchism is difficult to circumscribe and define. Nonetheless, anarchism is tied together by an interest in self-governance, equality of entitlement, and voluntary power relations marked by reciprocity and unfettered association (Call 2002; McLaughlin 2007). One of the central interests driving anarchist thought is how to organize in the absence of institutionalized leadership. Whether it’s order through respect of each individual’s rights and humanity or order as supported through rules worked out in a committee format, anarchism is often about order, albeit very vocal, disruptive, heterogeneous order.

Clastres’s 1974 publication of Society Against the State was a watershed moment for anarchism in anthropology; yet it is only since the publication of works by James C. Scott and David Graeber that increasing numbers of anthropologists have begun to apply anarchist theory to their research. Initially, anthropological use of anarchist theory was divided between those studying groups with acephalous sociopolitical organization and those who desired to bring anarchist thought and actions into anthropological practice. Bringing this research and practice into dialogue with one another has proven useful (e.g., articles in High 2012), and anarchist theory is advancing new ideas, practices, and interpretations within anthropology (Barclay 1982; Clastres 2007 [1974]; Graeber 2004; Macdonald 2013; Maskovsky 2013; Scott 2009).

In recent years, anarchist theory has found a new foothold in many other disciplines as well, especially geography (e.g., Springer 2016), political economy (e.g., Stringham 2005), sociology (e.g., Shantz and Williams 2013), material culture studies (e.g., Birmingham 2013), English (e.g., Cohn 2006), and indigenous studies (e.g., Coulthard 2014). The utility of anarchist theory, in many ways, is built on the same scaffold as its practice. Free association of multiple disciplines and theories are possible. This confluence of praxis works because, as Lasky (2011:4) notes when discussing the intersection of feminism, anarchism, and indigenism, “this interplay of diverse traditions, what some are calling ‘anarch@indigenism,’ (Alfred et al. 2007), forges intersectional analysis and fosters a praxis to de-center and un-do multiple axes of oppression.”

This is a much-needed reflexive collaboration. Anarchist theory has been a very white and male-centered space in the Global North that has often unintentionally excluded many of the voices it was interested in supporting and amplifying. Anarchism in the Global South has been much more inclusive, and anarchist theory there has blossomed by both questioning the primacy of hierarchy as the desired model of a complex society and engaging in the larger program of decolonizing sociopolitical systems (for example, the Rojava autonomous zone in northern Syria [Enzinna 2015; Weinberg 2015] and Aymara community organization in Bolivia [Zibechi 2010]). On a global scale, a more heterovocal and simultaneous package of anarchist thought has emerged that includes, intersects, and/or supports feminist, indigenous, Western, and Global South philosophical traditions.

Anarchy and Archaeology

While anarchism has positively influenced many social science disciplines, it has yet to be widely applied within archaeology. To date, the few explicit and published uses of anarchist theory within archaeology include work by Fowles (2010), Angelbeck and Grier (2012), Flexner (2014), Morgan (2015), Wengrow and Graeber (2015), and dissertations by Sanger (2015) and Borck (2016), as well as some discussion by González-Ruibal (2012, 2014). These examples are followed up by the recent publication on Savage Minds of a framework for an anarchist archaeology entitled “Foundations of an Anarchist Archaeology: A Community Manifesto” that was written by a non-hierarchy of authors (Black Trowel Collective 2016).

Anarchist theory’s absence in our discipline is particularly interesting since resistance to authority has a long history of study in archaeology. Many recognize that the establishment of decentralized social relations is not a “natural” condition but rather requires significant effort (e.g., Trigger 1990). In small-scale societies, authority is often resisted through leveling mechanisms including ostracism, fissioning, public disgrace, and violence (Cashdan 1980; Woodburn 1982). Within larger societies, archaeologists have suggested a variety of ways in which power relations can arise in decentralized forms, including sequential hierarchies (Johnson 1982) and heterarchies (Crumley 1995; see also McGuire and Saitta 1996). The archaeological study of decentralized power structures and active resistance to authority has become increasingly common (Conlee 2004; Dueppen 2012; Hutson 2002) and often benefits from Marxist, postcolonial, feminist, and indigenous critiques that highlight the importance of class, gender, and race in formulating power structures.

Considering the history of concern over the control of power and the growth of inequity appears as ancient as human society (e.g., Wengrow and Graeber 2015), these overlaps with anarchism are unsurprising. Anarchist historians have even taken parallel interests such as these to argue that anarchism is quite ancient. Kropotkin (1910) contended that the early philosophical underpinnings for anarchism could be seen in writings by the sixth-century BC Taoist Laozi and with Zeno (fourth century BC) and the Hellenistic Stoic tradition. Others have argued that Christ in the New Testament is a fundamentally anarchist figure (Woodcock 1962:38 citing Lechartier) and that Al-Asamm and the Mu’tazilites were Muslim anarchists in the ninth century AD (Crone 2000). But instead of early strains of anarchism, Woodcock has argued that anarchist historians and theorists are identifying “attitudes which lie at the core of anarchism—faith in the essential decency of man, a desire for individual freedom, an intolerance of domination” (1962:39).

In some ways it is an act of theoretical and philosophical colonization to label anyone interested in contesting power or emancipation of the individual as anarchist, and since anarchism thrives in a multivocal environment, it should be antithetical as well. Researchers have recognized this in various ways. Patricia Crone (2000) burns through a bit of text noting that the Mu’tazilites were anarchist not because they subscribed to anarchist thought, but because they thought society could function without the state. Anarchist archaeologists often recognize the simultaneity of these fellow travelers with the term anarchic to avoid co-opting modes of thought and action that are not explicitly anarchist.[1] Thus anarchic is like anarchism but not explicitly of it.

For example, in her article “The Establishment and Defeat of Hierarchy” (2004), Barbara Mills contends that the creation and caretaking of inalienable possessions evidence human processes that serve to generate and reinforce social hierarchy through religious practice. She combines that with an understanding of radical power dynamics wherein hierarchy is contested through the destruction of the material signature of that ritual inequality. While not a product of anarchist thought, her article nicely captures anarchic principles through the theoretical lens of materialism.

As another example, Robert L. Bettinger’s book, Orderly Anarchy: Sociopolitical Evolution in Aboriginal California, drawing on the “ordered anarchy” described by Sir E. E. Evans-Prichard in The Nuer, is a study of how decentralized power structures formed and functioned among Native American groups in precolonial California. Bettinger’s work can also be considered an anarchic study, since he seeks to understand how governance without government can be accomplished, yet does not draw on anarchist theory.

And there is a host of other fellow travelers. These include the recent Punk Archaeology book published by Caraher and colleagues (2014); Sassaman’s (2001) work on mobility as an act of resistance to state-building; Creese’s (2016) work on consensus-based, non-hierarchical polities in the Late Woodland period of eastern North America; and complexity scientists within archaeology (sensu Maldonado and Mezza-Garcia 2016; Ward 1996 [1973]). While not explicitly anarchist, these examples all demonstrate that anarchic ideas are more prominent than many realize.[2]

Anarchy and Studying the Past

So-called middle-range societies have traditionally been offered little agentive powers within archaeological research. They are often seen as acting under the whims of greater entities (climate, neighboring “complex” groups, etc.). Archaeological chronologies are littered with Intermediate, Transitional, and other terms for periods of dissolution and “de-evolution,” many of which are given little interpretive precedence in comparison to Classical, Formative, and periods otherwise marked by hierarchical “fluorescence.”

Anarchist theory, with its focus on social alienation and a questioning of political representation, offers unique insights into these periods. Indeed, traditional archaeological chronologies are turned on their heads when reframed using anarchist theory. Periods of cultural disorganization, collapse, and disintegration are instead seen as points of potential societal growth and freedom. Anarchist theory questions the base concept that “simplicity” is the starting point and that only “complexity” is achieved. Instead, equivalent power relations are recognized as requiring tremendous amounts of effort to establish and maintain. As such, archaeologists utilizing anarchism conceptualize and interpret “simple” societies in new ways to the extent they are seen as earned through direct action and actively produced through entrenched practices, ideologies, and social institutions. And hierarchical, or complex, societies can be viewed as ones that emerge when social institutions that minimize or limit self-aggrandizement break down (e.g., Borck 2016). Instead of being constructed by purposeful actions of elite individuals, these top-down societies may grow like weeds from cracks spreading in the social processes meant to limit aggrandizement.

The contestation of the dominance of hierarchy is also one of the reasons why anarchist archaeologies are also often decolonizing archaeologies. They challenge the implicit idea that states are the pinnacle of society and “rather than seeing non-state societies as deviant, the exception to the rule, we might begin to look at examples of anarchic societies as adaptive and progressive along alternative trajectories with historical mechanisms in place designed to maintain relative degrees of equality, rather than simply those who haven’t yet made it to statehood” (Flexner 2014:83).

Anarchism and Archaeological Practice

Much like other social critiques (e.g., feminism, Marxism, postcolonial, queer), anarchist theory is applicable not only to our interpretations of past peoples but also to our discipline as a whole. For decades, archaeologists have been increasingly concerned with developing projects that are more inclusive, collaborative, responsive, and reflexive. Archaeologists have called for changes in field methods, publication practices, and interpretive stances in order to produce a discipline with fewer boundaries, decreased centralization of authority, and increased equality of representation (Atalay 2006; Berggren and Hodder 2003; Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson 2008; Conkey 2005; Gero and Wright 1996; Silliman 2008; Watkins 2005). Anarchist theory has been applied to similar restructuring projects within education, sociocultural anthropology, and sociology (e.g., Ferrell 2009; Haworth 2012). In each of these projects, collaborative engagement and informational transparency were increased as researchers restructured their practices around anarchist ideals to focus on free access to information and democratization of decision-making.

Anarchist theory can also be used to scrutinize heritage management decisions and to offer insights into how practices might be revitalized, revolutionized, or entirely reframed. As a brief example, examining UNESCO cultural preservation decisions in North America leads to deep questions about what Western society valorizes and what type of history we are creating through heritage preservation decisions.

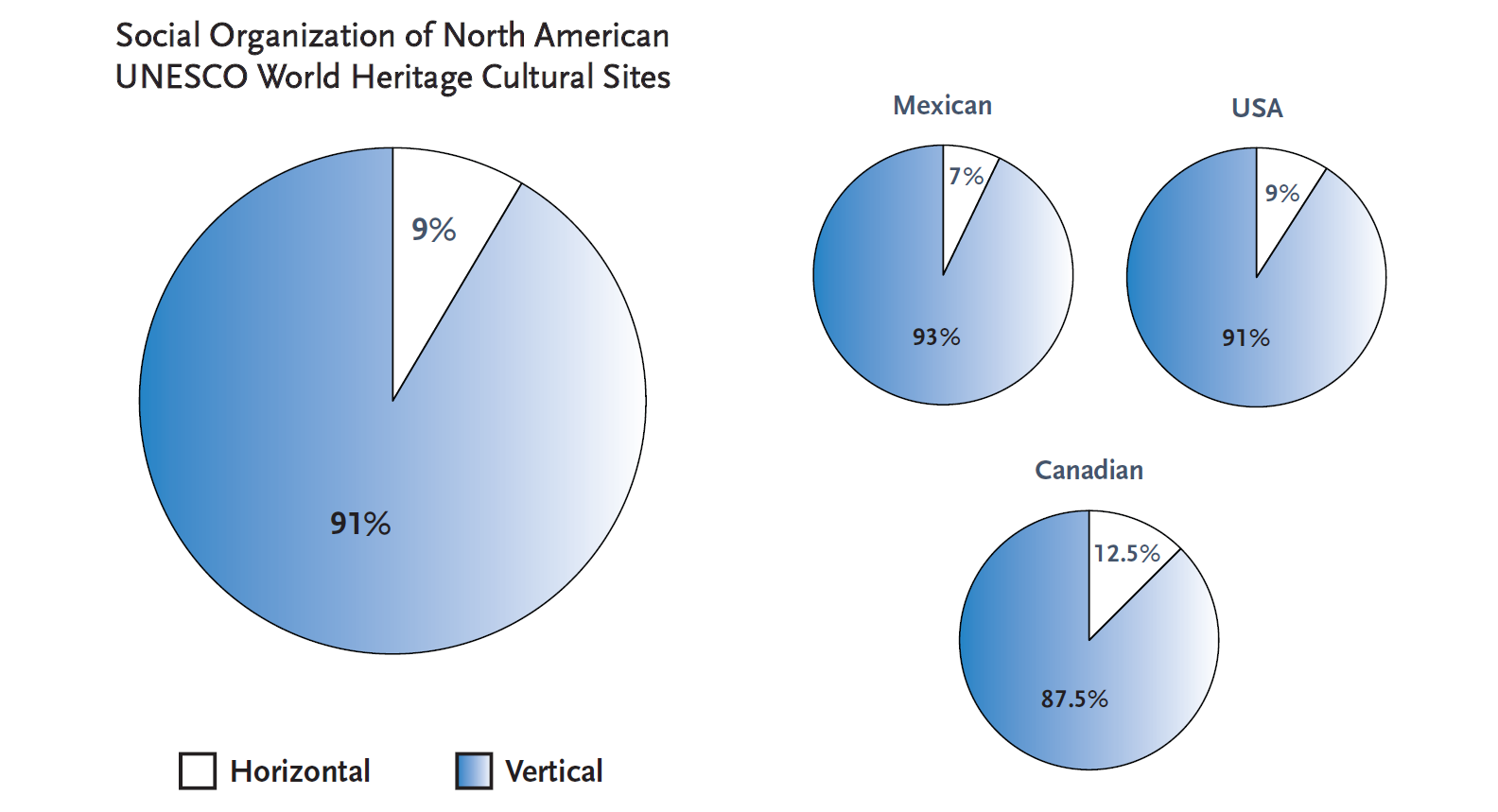

Out of the 47 UNESCO World Heritage Cultural Sites in North America,[3] only four (9 percent) can best be described as horizontally organized (Figure 1).[4][5] This low number does not accurately reflect the history of this continent since much more than 9 percent of human history in North America consisted of horizontally organized governance (although see Wengrow and Graeber 2015 and Sanger this issue for a discussion of the problems with assuming all Neolithic groups are “simply” egalitarian). It is arguable that these sociopolitical organization preservation decisions arise out of a form of statist ethnocentrism that makes it conceptually difficult to envision complex modes of organization that are not hierarchical. Indeed, if we continue at present pace, we risk erasing our past through political biases embedded in heritage preservation value judgments. Without more representative, or at least balanced, decisions, our shared history will mostly be one of hierarchical societies: the present re-created in the past.

Many archaeologists are also very concerned with the intersection of archaeology and pedagogy, especially in regard to the ways archaeologists teach about the past in the classroom, at field schools, and through mentoring. Scholars of engaged pedagogy have long commented on the detrimental effects hierarchical forms of teaching produce in diverse student populations (e.g., Freire 1993; hooks 2003). Anarchist thinkers also have a long tradition with pedagogical experimentation (e.g., Godwin 1793; Goldman 1906; Stirner 1967) and suggest ways in which learning can benefit from decentralized authority, individuated experimentation, and situated learning (Haworth 2012; Suissa 2010; Ward 1996).

Anarchism also provides important insights regarding the way we engage with modern communities. Collaborative projects informed by anarchism aim to shed traditional hierarchical posturing and instead integrate stakeholders throughout the research process. Applied to work with descendant communities, this approach can also serve to decolonize the research relationship, as well as archaeological research in general.

Anarchism’s central concern with unequal power structures also provides a useful framework for examining the division between specialists (professionals) and nonspecialists (amateurs) and challenges the control of information within the discipline. Anarchist frameworks may help to dismantle the normative divide between archaeologists (framed as producers and interpreters of the past) and the public (thought of as passive consumers of archaeological narratives). This also means that, as knowledge holders, archaeologists need to answer some difficult questions about what it means to be a specialist. Edward Said (1993) was grappling with just this question when he wrote that “an amateur is what today the intellectual ought to be.”

Critical to both anarchist archaeological theories and practices is a philosophical commitment to decentralizing power relations and building a more inclusive discipline. This includes a destabilization of Western conceptions of science, time, and heritage that are often employed to legitimize the practice of archaeology in the broader political sphere. Using an anarchist lens, non-Western or nonnormative world-views, ontologies, epistemologies, and valuations are given equal footing, both in terms of interpreting the past and in the formation of current practices. Here again, anarchist theory intersects and parallels many queer, indigenous, and feminist critiques.

Archaeology is particularly well suited to engage with, and benefit from, anarchist theory since we often study non-state societies, points of political dissolution, active rejections of authority by past peoples, and the accrual of power by elites and institutions. Likewise, the restructuring of our discipline to be more inclusive is certainly underway. Anarchist theory can provide a new philosophical grounding by which archaeologists can reframe their engagements with the past, with students, descendant peoples, the engaged public, and each other in ways that will redistribute authority and empower individuals and communities often relegated to the margins of our discipline.

The articles in this issue take on some of these contexts. John Welch begins the discussion by thinking about how resistance can be implemented and centralized authority combatted in his complementary narrative to Spicer’s Cycles of Conquest. Welch offers a series of variables (scale, frequency, and effectiveness) by which we might be able to better describe and compare resistance efforts that he then applies to Apaches relations with Spanish, Mexican, and US forces. The dynamism allowed through the applications of these variables allows Welch to better clarify the means by which the Apaches combatted colonial forces as well as offering insights into how anarchism is not a single mindset, practice, or goal—but is rather a concept that we apply to the world in order to better understand it.

Carol Crumley builds on Welch’s work by arguing that anarchist archaeology, or anarchaeology, is a moral and ethical activity, designed to critique uneven power structures and offer alternative understandings of the past as well as the present. Crumley argues that traditional notions of progress from simplicity to complexity are beginning to crumble and that in their stead, a better understanding of collective action and governance is emerging.

The piece by Edward Henry, Bill Angelbeck, and Uzma Z. Rizvi likewise focuses on the practice of archaeology, arguing that an anarchist approach offers a greater degree of epistemological freedom in our research, including at its most basic level—the creation and application of typologies. When applied as essential and timeless, typologies restrict our understanding of the past and end up reifying themselves as objects of study. Instead, Henry et al. argue that typologies must remain experimental, fluid, and above all else relational, by which they argue archaeologists ought to apply typologies that foreground connections between phenomena.

Theresa Kintz continues the focus on the practice of archaeology, both in the present and as a vision of the future if anarchist principles are brought into the discipline. Using evocative language, Kintz looks at the practice of archaeology through many paths: in the field, at museums, through CRM reports, with indigenous communities, and among academic archaeologists. By suggesting we are currently living in an age of rapid environmental change caused by humans—the Anthropocene—Kintz argues that the unique point of view offered by archaeologists is of critical importance as it offers alternative ways of living in the world.

Matthew Sanger concludes the issue by using anarchist theory to redirect what he sees as an overexuberance in the study of hunter-gatherer complexity. Sanger suggests that a preoccupation with studying complexity has resulted in an underappreciation of balanced power relations in many non-agrarian communities as these egalitarian structures are thought to be natural and to require little work to maintain. Instead, Sanger argues that “simple” hunter-gatherers often create, promote, and preserve anarchic ideals through acts of counter-power—acts that often predate the emergence of centralized authority and are indeed the means by which such authority often fails to take hold.

Finally, the “Many Voices in Anarchist Archaeology” sidebars are an assembly of archaeologists and material culture scholars engaged in the development of applications for an anarchist archaeology. There is no theme. Authors were given full sway to write for themselves as anarchist archaeologists. These pieces are meant to provide an appreciation for the breadth of anarchism and to highlight how it is becoming more widely applied within the discipline.

References Cited

Alfred, Taiaiake, Richard Day, and Glen Sean Coulthard

--- 2007 Anarcho-Indigenism. In Indigenous Leadership Forum. University of Victoria, BC.

Angelbeck, Bill, and Colin Grier

--- 2012 Anarchism and the Archaeology of Anarchic Societies: Resistance to Centralization in the Coast Salish Region of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Current Anthropology 53(5):547–587.

Atalay, Sonya

--- 2006 Indigenous Archaeology as Decolonizing Practice. American Indian Quarterly 30(3/4):280–310.

Barclay, Harold B.

--- 1982 People without Government. Kahn & Averill with Cienfuegos Press, London.

Berggren, Åsa, and Ian Hodder

--- 2003 Social Practice, Method, and Some Problems of Field Archaeology. American Antiquity 68:421–434.

Bettinger, Robert L.

--- 2015 Orderly Anarchy: Sociopolitical Evolution in Aboriginal California. University of California Press, Oakland.

Birmingham, James

--- 2013 From Potsherds to Smartphones: Anarchism, Archaeology, and the Material World. In Without Borders or Limits: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Anarchist Studies, edited by Jorell A. Meléndez Badillo and Nathan J. Jun, pp. 165–176. Cambridge Scholars Press, London.

Black Trowel Collective

--- 2016 “Foundations of an Anarchist Archaeology: A Community Manifesto.” Savage Minds (blog) 31 October. Electronic document, http://savageminds.org/2016/10/31/foundations-of-an-anarchist-archaeology-a-community-manifesto/, accessed December 11, 2016.

Borck, Lewis

--- 2016 Lost Voices Found: An Archaeology of Contentious Politics in the Greater Southwest, A.D. 1100–1450. Unpublished PhD dissertation, School of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson.

Call, Lewis

--- 2002 Postmodern Anarchism. Lexington Books, Lanham, Maryland.

Caraher, William R., Kostis Kourelis, and Andrew Reinhard (editors)

--- 2014 Punk Archaeology. Digital Press at the University of North Dakota, Grand Forks.

Cashdan, Elizabeth A.

--- 1980 Egalitarianism among Hunters and Gatherers. American Anthropologist 82(1):116–120.

Chomsky, Noam

--- 2005 Chomsky on Anarchism. AK Press, Chico, California.

Clastres, Pierre

--- 2007 [1974] Society Against the State: Essays in Political Anthropology. 6th ed. Zone Books, New York.

Cohn, Jesse S.

--- 2006 Anarchism and the Crisis of Representation: Hermeneutics, Aesthetics, Politics. Susquehanna University Press, Selinsgrove, Pennsylvania.

Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip, and T. J. Ferguson

--- 2008 Introduction: The Collaborative Continuum. In Collaboration in Archaeological Practice: Engaging Descendant Communities, edited by Chip Colwell-Chanthaphonh and T. J. Ferguson, pp. 1–32. AltaMira Press, New York.

Conkey, Margaret W.

--- 2005 Dwelling at the Margins, Action at the Intersection? Feminist and Indigenous Archaeologies. Archaeologies 1(1):9–59.

Conlee, Christina A.

--- 2004 The Expansion, Diversification, and Segmentation of Power in Late Prehispanic Nasca. Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 14(1):211–223.

Coulthard, Glen Sean

--- 2014 Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Creese, John Laurence

--- 2016 Emotion Work and the Archaeology of Consensus: The Northern Iroquoian Case. World Archaeology 48(1):14–34.

Crone, Patricia

--- 2000 Ninth-Century Muslim Anarchists. Past & Present (167):3–28.

Crumley, Carole L.

--- 1995 Heterarchy and the Analysis of Complex Societies. Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 6(1):1–5.

Dolgoff, Sam

--- 1971 Introduction. In Bakunin on Anarchy: Selected Works by the Activist-Founder of World Anarchism, edited by Sam Dolgoff, pp. 3–21. Vintage Books, New York.

Dueppen, Stephen A.

--- 2012 From Kin to Great House: Inequality and Communalism at Iron Age Kirikongo, Burkina Faso. American Antiquity 77:3–39.

Enzinna, Wes

--- 2015 A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS’ Backyard. New York Times 24 November. Electronic document, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/29/magazine/a-dream-of-utopia-in-hell.html, accessed December 12, 2016.

Ferrell, Jeff

--- 2009 Against Method, Against Authority . . . For Anarchy. In Contemporary Anarchist Studies: An Introductory Anthology of Anarchy in the Academy, edited by Randall Amster, Abraham DeLeon, Luis A. Fernandez, Anthony J. Nocella II, and Deric Shannon, pp. 73–81. Routledge, New York.

Flexner, James L.

--- 2014 The Historical Archaeology of States and Non-States: Anarchist Perspectives from Hawai’i and Vanuatu. Journal of Pacific Archaeology 5(2):81–97.

Fowles, Severin

--- 2010 A People’s History of the American Southwest. In Ancient Complexities: New Perspectives in Pre-Columbian North America, edited by Susan Alt, pp. 183–204. University of Utah Press, Provo.

Freire, Paulo

--- 1993 Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum, New York.

Gero, Joan, and Rita P. Wright

--- 1996 Archaeological Practice and Gendered Encounters with Field Data. In Gender and Archaeology, edited by Rita P. Wright, pp. 251–280. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

Godwin, William

--- 1793 An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and Its Influence on General Virtue and Happiness. G. G. and J. Robinson, Paternoster-Row, London.

González-Ruibal, Alfredo

--- 2012 Against Post-Politics: A Critical Archaeology for the 21st Century. Forum Kritische Archäologie 1:157–166.

--- 2014 An Archaeology of Resistance: Materiality and Time in an African Borderland. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Maryland.

Goldman, Emma

--- 1906 The Child and Its Enemies. Mother Earth 1(2):7–13.

Graeber, David

--- 2004 Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology. Prickly Paradigm Press, Chicago.

Haworth, Robert H.

--- 2012 Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education. PM Press, Oakland, California.

High, Holly

--- 2012 Anthropology and Anarchy: Romance, Horror or Science Fiction? Critique of Anthropology 32(2):93–108.

hooks, bell

--- 2003 Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope. Routledge, New York.

Hutson, Scott R.

--- 2002 Built Space and Bad Subjects: Domination and Resistance at Monte Albán, Oaxaca, Mexico. Journal of Social Archaeology 2(1):53–80.

Johnson, Gregory A.

--- 1982 Organizational Structure and Scalar Stress. In Theory and Explanation in Archaeology: The Southampton Conference, edited by Colin Renfrew, Michael Rowlands, and Barbara A. Segraves-Whallon, pp. 389–421. Academic Press, New York.

Kant, Immanuel

--- 1996 [1798] Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale.

Kropotkin, Peter

--- 1910 Anarchism. In Encyclopædia Britannica, Vol. 1, pp. 914–919. 11th ed. Encyclopædia Britannica, New York.

Lasky, Jacqueline

--- 2011 Indigenism, Anarchism, Feminism: An Emerging Framework for Exploring Post-Imperial Futures. Affinities: A Journal of Radical Theory, Culture, and Action. Anarch@Indigenism: Working Across Difference for Post-Imperial Futures: Intersections Between Anarchism, Indigenism, and Feminism:3–36.

Macdonald, Charles J-H

--- 2013 The Filipino as Libertarian: Contemporary Implications of Anarchism. Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 61(4):413–436.

Maldonado, Carlos, and Nathalie Mezza-Garcia

--- 2016 Anarchy and Complexity. Emergence: Complexity and Organization 18(1):52–73.

Marshall, Peter H.

--- 1992 Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism. Harper-Collins, London.

Maskovsky, Jeff

--- 2013 Protest Anthropology in a Moment of Global Unrest. American Anthropologist 115(1):126–129.

McGuire, Randall H., and Dean J. Saitta

--- 1996 Although They Have Petty Captains, They Obey Them Badly: The Dialectics of Prehispanic Western Pueblo Social Organization. American Antiquity 61:197–216.

McLaughlin, Paul

--- 2007 Anarchism and Authority: A Philosophical Introduction to Classical Anarchism. Ashgate Publishing Company, Burlington, Vermont.

Mills, Barbara J.

--- 2004 The Establishment and Defeat of Hierarchy: Inalienable Possessions and the History of Collective Prestige Structures in the Pueblo Southwest. American Anthropologist 106(2):238–248.

Morgan, Colleen

--- 2015 Punk, DIY, and Anarchy in Archaeological Thought and Practice. Online Journal in Public Archaeology 5:123–146.

Proudhon, Pierre Joseph

--- 1876 [1840] What Is Property? An Enquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government. Trans. Benjamin R. Tucker. Benjamin Tucker, Princeton, Massachusetts.

Said, Edward

--- 1993 The Reith Lectures: Professionals and Amateurs: Is There Such a Thing as an Independent, Autonomously Functioning Intellectual? Independent 15 July. Electronic document, http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/the-reith-lectures-speaking-truth-to-power-in-his-penultimate-reith-lecture-edward-said-considers-1486359.html, accessed December 11, 2016.

Sanger, Matthew C.

--- 2015 Life in the Round: Shell Rings of the Georgia Bight. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Columbia University, New York.

Sassaman, Kenneth E.

--- 2001 Hunter-Gatherers and Traditions of Resistance. In The Archaeology of Traditions: Agency and History Before and After Columbus, edited by Timothy R. Pauketat, pp. 218–236. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Scott, James C.

--- 2009 The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Shantz, Jeff, and Dana M. Williams

--- 2013 Anarchy and Society: Reflections on Anarchist Sociology. Brill, Leiden.

Silliman, Stephen W. (editor)

--- 2008 Collaborating at the Trowel’s Edge: Teaching and Learning in Indigenous Archaeology. Amerind Studies in Archaeology. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Springer, Simon

--- 2016 The Anarchist Roots of Geography: Toward Spatial Emancipation. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Stirner, Max

--- 1967 [1842] The False Principle of Our Education: Or, Humanism and Realism. Edited by James J. Martin. Translated by Robert H. Beebe. Ralph Myles Publisher, Colorado Springs.

Stringham, Edward (editor)

--- 2005 Anarchy, State, and Public Choice. Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton.

Suissa, Judith

--- 2010 Anarchism and Education: A Philosophical Perspective. 2nd ed. PM Press, Oakland, California.

Trigger, Bruce G.

--- 1990 Maintaining Economic Equality in Opposition to Complexity: An Iroquoian Case Study. In The Evolution of Political Systems: Sociopolitics in Small-Scale Sedentary Societies, edited by Steadman Upham, pp. 119–145. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Ward, Colin

--- 1996 [1973] Anarchy in Action. Freedom Press, London.

Watkins, Joe E.

--- 2005 Through Wary Eyes: Indigenous Perspectives on Archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology 34:429–449.

Weinberg, Bill

--- 2015 Syria’s Kurdish Revolution: The Anarchist Element and the Challenge of Solidarity. Fifth Estate 393 (Spring). Electronic document, http://www.fifthestate.org/archive/393-spring-2015/syrias-kurdish-revolution/, accessed December 12, 2016.

Wengrow, David, and David Graeber

--- 2015 Farewell to the “Childhood of Man”: Ritual, Seasonality, and the Origins of Inequality. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 21(3):597–619.

Woodburn, James

--- 1982 Egalitarian Societies. Man 17(3):431–451.

Woodcock, George

--- 1962 Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Meridian Books, New York.

Zibechi, Raúl

--- 2010 Dispersing Power: Social Movements as Anti-State Forces. AK Press, Oakland, California.

[1] Anarchic is also used as an adjective to define decentralized or non-state societies, working before or outside of anarchist theory, where individuals and groups actively resist concentrations of authority and promote decentralized organizational structures.

[2] See also David Graeber’s Are You An Anarchist? The Answer May Surprise You! https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/david-graeber-are-you-an-anarchist-the-answer-may-surprise-you.

[3] Data was compiled from the UNESCO World Heritage List and included all of the cultural and mixed cultural/natural sites from the three countries that comprise North America: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/.

[4] Data is available at https://github.com/lsborck/2016UNESCO_Cultural.

[5] Coding these sites as either a vertical or horizontal sociopolitical organization necessarily reduces these political forms from a continuum into a binary.