Benjamin Franks

Rebel Alliances

The means and ends of contemporary British anarchisms

Terminology: ‘Class struggle anarchism’

Terminology: ‘Liberal Anarchism’

Chapter One: Histories of British Anarchism

1. Problems in Writing Anarchist Histories

3. The Heroic Period: A history of British anarchism up to 1914

3.2. Workers Arise: Anarchism and industrial organisation

3.3. Propaganda and Anarchist Organisation

3.4. Ideological Differences in Class-Struggle Anarchism

4. Anarchism During the First World War, 1914 — 1918

5. The Decline of Anarchism and the Rise of the Leninist Model, 1918–1936

7. Spring and Fall of the New Left, 1956 — 1976

7.2. Alternative Revolutionary Subjects

8. Punk and DiY Culture, 1976 — 1984

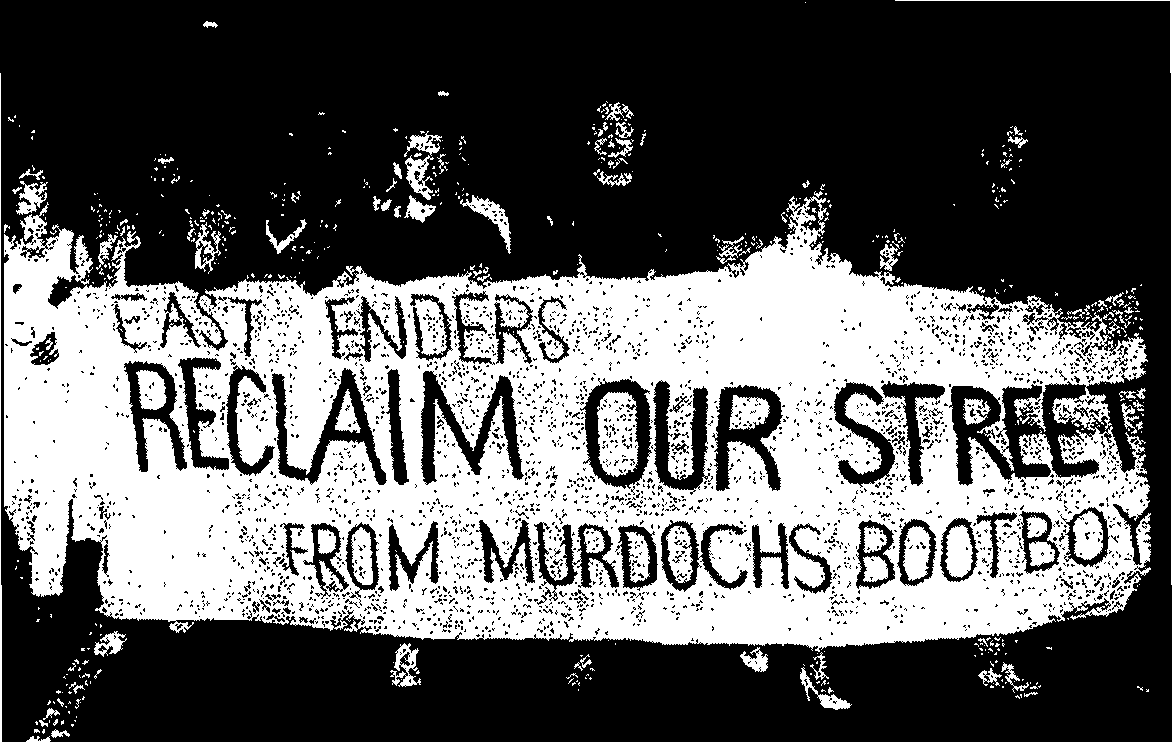

9. The Revival of Class struggle Anarchism: The Miners’ Strike to anti-capitalism, 1984 — 2004

Chapter Two: The Anarchist Ethic

PART I: The Anarchist Ethical Framework

2.1. The Means-Ends Distinction

3.1. Prefiguration Versus Consequentialism

3.2. Anarchist Consequentialism

4.1. Deontology and Contractual Relationships

4.2. Liberal Anarchist Deontology

4.3. Anarchism Against Liberal Rights

5. Direct Action: Means and Ends

5.2. Practicality and Direct Action

6. Constitutional Proceedings Versus Direct Action

6.3. Misdirected Sites of Power

7. Symbolic Action and Direct Action

8.2. Violence and the Working Class

Chapter Three: Agents of Change

1. The Anarchist Ideal: A concept of class agents

1.1. Agents in Anarchist Propaganda

1.2. The Decline and Rise of Class Within British Radicalism

5. Extension of Class: The social factory

6. Ethnicity, Gender and Sexuality

1.1. The First Form of Spontaneity: Chaosism

1.2. Second Form: Organisation only in revolutionary epochs

1.3. Third Form: Organisation by oppressed subject groups

2. Formal Structures: Leninist organisation

2.4. The Invisible Dictatorship

3. Contemporary Anarchist Structures

3.1. Centralism and The Platform

3.2. Federalism and the Manifesto

4.1. Syndicalism, Anarcho-syndicalism and Trade Unionism

4.2. Against Workplace Organisation

4.2.1. Workplace Groups as Reformist

4.2.3. Privileging the Industrial Worker

4.3. Syndicalism and Other Forms of Organisation

5.1. The Structure of Community Based Groups

5.2. Environmental Groups: Tribes and communities

5.3. Internet Co-ordination — the Global Community

5.4. Community and Workplace Organisation

Chapter Five: Anarchist Tactics

1.1. Anarchist Ideal of Revolution

1.2. Temporary Autonomous Zone

2.3. Machine and Product Breaking

2.7. Go-Slow and Working Without Enthusiasm

4. Community Sabotage and Criminality

4.1. Vandalism and Hooliganism

5.3. Hyper-Passivity and Disengagement

Conclusion: ‘Resistance is fertile’

Guide To Footnotes and Bibliography

Anarchist Magazines and Newspapers Consulted

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was originally begun in September 1991. It has taken over fourteen years from the start of the research to its publication. Nonetheless, it is this, the last page to be consigned to paper, which has proven the most difficult to write. There are so many people to whom I am deeply indebted, for their love, friendship and patience, that it is difficult to know where to start. As a result, this brief section already runs the risk of appearing like the Oscar night acceptance speech of a particularly neurotic actor. There are also the concerns of overlooking those who have made significant sacrifices — and of namingthose who would prefer to remain anonymous. In listing people there is the additional hazard of those at the top being considered of greater importance than those in the middle or end, so except for the first few names, everyone else is listed in reverse alphabetical order. I have to start, however, by thanking my partner Lesley for her love, good humour, patient proofreading and encouragement, and my parents Susan and David Franks for their constant support, love and hot food. It would be quite amiss not to acknowledge the carefully considered, academic guidance provided by Jon Simons of the University of Nottingham, supported by the kindly words of Prof. Richard King.

My thanks are also due to Paul M. of London Class War, Mike & Clare of the Anarchist Federation, Trevor B. of Movement Against the Monarchy, Millie W. of the Advisory Service for Squatters and Bill Godwin formerly of the Anarchist Trade Union Network for their comments. Their relevant and good-humoured advice was pertinent, if not always welcome. The advice and support offered by Malcolm of Dark Star and Michael Harris of AK Press was also invaluable. I would also like to thank Euan Sutherland and Alexis McKay of AK Press for their invaluable assistance.

My gratitude to the following is also quite beyond words: Rowan Wilson, Kathy Williams, Millie Wild, Bill Whitehead, Colin West, Mark Tindley, Claire Taylor, Robert Smith, Simon Sadler, Helen Rodriguez-Grunfeld, Sarah Merrick, David McLellan, Angie McClanahan, Brian and Suzanne Leveson (Cumper), David Lamb, Richard King, Sarah Kerr, Rita Kay (z”l), Sean Johnston, Adenike Johnson, Benedict Jenkins, Natalie Ireland, Steven Gillespie, Rebecca Howard, Stephen Harper, Stephen Hanshaw, Jim Hanshaw, Stuart Hanscomb, John and Gina Garner, Tim Franks, Esme Choonara, Mike Craven, Larry Chase, Russell Challenor, Carolyn Budow, David Borthwick, Ian Bone, Julie Bernstein, Mark Ben-David (z”l), Trevor Bark, Clare Bark and thanks also to the domestics at Dudley Road Hospital (1991–2), participants at the Goldsmiths’ College, extra-mural philosophy classes (1992–4), WEA current affairs courses Derby (1997–2000) and Nottingham (2000), University of Nottingham politics classes (1997–2000), fellow staff members at Blackwells University Bookshop, Nottingham University (1997–9), students and staff at the University of Glasgow, Crichton Campus (2001-), and my friends in numerous anarchist and Leninist groups.

Introduction

This book, like many other recent texts dealing with radical politics, was going to start with a detailed account of one of the numerous antiglobalisation protests.[1] There are attractions with starting with vivid accounts of these demonstrations; dramatic narratives can capture the colour and carnival of the fancy-dressed dandies, protesting stilt walkers and semi-clad demonstrators, the chaotic rhythms of electronic dance music, samba-bands and police sirens. Mixed into this vibrant concoction is exhilaration at assaults on the property of sweatshop profiteers, humbling politicians by restricting them to house arrest inside their luxury hotels, and the mass collegiality of shared dissent. Then there is the hi-tech shock and awe of the heavily armoured state forces, ending sometimes, as in the case of Carlo Giuliani, a 23-year-old Italian anarchist, in brutal tragedy.[2] In comparison, few writing on politics, even the vivacious discourse of contemporary anarchisms, can match the emotional descriptions of exuberant mass action. It is unsurprising, therefore, that these eye-catching, high-profile gatherings have become a central theme in contemporary assessments of radical politics.

The first draft of this book began with an extended narrative that described the ‘Carnival Against Capitalism’ of Friday June 18th 1999 (otherwise known as J18). It covered the London-end of the global protest against the G8, where leaders of the eight top industrialised countries met to discuss and agree further steps towards freer trade. There was an account of the assaults on the facades of billion dollar corporations, the occupation of Congress House, the head quarters of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), by those angry at the official labour movement’s involvement in supporting the dictates of the government. That version included the selective torching of luxury cars and other creative acts of destruction aimed at the beneficiaries of global capitalism, and the invasion of the LIFFE building (a trading exchange), where City traders, furious that their turf had been occupied by joyous assortments of anti-market pranksters and class struggle mobs, hurled abuse at the invaders of the free trade area. It was a rare day, for seldom had stock-market dealers, Tom Wolffe’s ‘masters of the universe’, been so threatened. The extended account covered the tactics at avoiding detection, the CCTV camera covered up by plastic bags, the banners proclaiming poetic rebellion strung up through the square mile, preventing the easy movement of the mounted police. The account also covered the identities of those taking part in J18, which included many explicitly class struggle libertarians, plus those with a distinct influence from this direction.[3] Noticeably absent on the day were participants from the once powerful Leninist organisations. Although some of the groups taking part in J18 were not explicitly class struggle, the modes of organisation, the targets and the methods were consistent with contemporary anarchism.

But the original description of J18 and the anti-capitalist events has been curtailed Whilst the anti-globalisation and anti-capitalist movements do contain a substantial element of anarchists and anarchist inspired groupings, there has been too great an emphasis on the recent anti-globalisation movements that has risked both ignoring the other manifestations of anarchist activity and also subsuming the other currents in the anti-capitalist movement that are antipathetic to anarchism into the libertarian fold. In the context of the United Kingdom, these would include anti-Third World debt campaigners initiated by Christian churches, social democrats like the trade unions and Green Party, state-socialists like the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and Scottish Socialist Party (SSP) and more philosophically conservative political groupings. The anti-capitalist movement has also undergone significant transformation, most notably since late 2001.[4] It is also relatively new, and even since the late 1990s, when it developed as a significant phenomenon, it has been only mobilised sporadically. Concentrating too much on this form of protest overlooks the other more long-standing, and often more pressing areas of libertarian concern than those of the ‘anarchists’ travelling circus’, as Prime Minister Tony Blair referred to the anti-capitalist protestors.[5] The often anarchic anti-globalisation protests did not occur in a vacuum, but are part of a process of radical challenge to particular forms of oppression. One of the themes of this book is tracing and classifying the myriad methods employed by class struggle anarchist groups and assessing them according to how far they reflect and embody their complex, multiple objectives.

Terminology: ‘Class struggle anarchism’

In order to carry out this examination and evaluation, some clarification of the terminology employed throughout the text is required. The organisations identified under the heading of ‘class struggle anarchism’ include those that identify themselves as such, as well as those from autonomist marxist[6] and situationist-inspired traditions. The organisations and propaganda groups examined include the Anarchist Black Cross (ABC), Anarchist Federation (AF) (formerly the Anarchist Communist Federation (ACF)), Anarchist Youth Network (AYN), Anarchist Workers Group (AWG), Aufheben, Black Flag, Class War Federation (CWF), Earth First! (EF!), Here and Now, Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), Reclaim the Streets (RTS), Solidarity, Solidarity Federation (SolFed) (formerly the Direct Action Movement (DAM)), Subversion, White Overall Movement Building Libertarian Effective Struggles (WOMBLES), Wildcat and Workers Solidarity Movement (WSM), many local and regional federations such as Haringey Solidarity Group, Herefordshire Anarchists and Surrey Anarchist Group as well as the precursors to all these associations.

These organisations and their tactics can be said to form a semi-coherent subject for this book as they meet four hesitantly proposed criteria. The first is a complete rejection of capitalism and the market economy, which demarcates anarchism from reformist politics and extreme liberal variants (often referred to as ‘anarcho-capitalism’ or in America as ‘libertarianism’). The second criteria is an egalitarian concern for the interests and freedoms of others as part of creating non-hierarchical social relations; the third is a complete rejection of state power and other quasi-state mediating forces, which distinguishes libertarianism from Leninism. The final criterion, alongside the other three, is the basis for the framework used here for assessing anarchist methods: a recognition that means have to prefigure ends. The first three criteria contain elements of ‘anti-representation’, dismissing oppressive practices that construct identities through market principles of class or wealth, party or nation, leader or citizen. The last criterion, prefiguration, is indicative of the reflexivity of anarchist methods which not only react against existing conditions but are also ‘self-creative’. These four criteria create the ‘ideal type’ used to assess the actions of contemporary groups.

These four identifiable standards contrast with the view of the political philosopher David Miller, who considered that the confusing multiplicity associated with anarchism meant that, unlike marxism, it had no identifying core assumptions and consequently could barely be called a political ideology.[7] The multitude of often incompatible interpretations of ‘anarchism’ would give Miller good grounds for this assertion. The label has been applied to Stirnerite individualism, Tolstoyan Christian pacifism, the hyper-capitalism of the Libertarian Alliance, as well as the class struggle traditions of anarchist communism, anarcho-syndicalism, situationism and autonomist marxism.[8] By limiting the scope to the revolutionary socialist variants of libertarianism, however, a distinctive group of ideas and practices can be identified through the aforementioned four criteria.

It was necessary to provide criteria to limit the scope of the subjects for analysis. Choosing appropriate standards for classifying political movements is always a precarious business. It is especially difficult to select appropriate measures for classifying class struggle anarchism as it constantly responds to changing circumstances and approves multiple forms of revolt. Yet there is a strong case for classifying class struggle anarchism using the four criteria. Historically, anarchist groups can be traced using these standards. John Quail, in his account of the growth of British anarchism, characterises anarchism using the first three criteria: ‘Anarchism is a political philosophy which states that it is both possible and desirable to live in a society based on co-operation, not coercion, organised without hierarchy More specifically it marks a rejection of the political structure which the bourgeoisie sought to establish — parliamentary democracy’.[9] And the commitment to these principles can be found in libertarian groups themselves, for instance in the definition of anarchism provided in 1967 by the Solidarity group[10] and in the shorter explanation in the Anarchist 1993 Yearbook. There are other statements proclaiming the same norms in the ‘Aims and Principles’ sections of most anarchist publications,[11] such as those of AF, Class War and SolFed ,[12]

Even with this clarification of the four criteria, the label ‘anarchism’ and other vital parts of the revolutionary lexicon have been subject to criticism by proponents and opponents of socialist libertarian traditions. Andy and Mark Anderson claim that the terminology of the revolutionary socialist groups under consideration is too vague and the objectives consequently obscure, thereby making debate confusing and alienating.[13] Such a problem concerning definition is not new; the first edition of Seymour’s The Anarchist discusses confusion surrounding the term as indeed do early copies of Kropotkin’s Freedom.[14] The Andersons’ objections are not without foundation, but a recognisable set of groups, movements and events can be categorised as part of the class struggle variant of anarchism. The differentiation is not precise or absolute. Groups such as Earth First! (EF!) initially saw themselves as unconcerned with issues of class and capitalism but, in Britain especially, many EF! sections have come to regard environmental activism as interwoven with more general class struggles.[15]

It should be noted that occasionally one trend or other would fall outside the criteria. However, to use more inclusive criteria, as David Morland recognises, would mean drawing up principles so vague as to be meaningless.[16] Anarchism’s constant evolution, its suspicion of universal tenets and its localist philosophy risk making any gauge for one epoch or region seem wholly inappropriate to another. Yet these criteria do hold remarkably well, within the relatively short time-span of the post-1984 period, of a fairly limited geographical region (predominantly the UK context).

Anarchism is a historically located set of movements. The opening chapter illustrates this by placing current groups and tactics in a wider context and introducing some of the main debates. The second chapter develops a framework for assessing anarchist actions, and ties this method of evaluation to the distinctive category of libertarian tactics known as ‘direct action’. The third chapter elucidates the importance of the appropriate agent, and examines what sort of revolutionary subject anarchism should embrace if it is to remain consistent to its principles. The fourth and fifth chapters categorise and assess anarchist organisational forms and tactics according to the types of group involved and their suitability according to the framework.

In the past, the class struggle trend was attractive to a broad swathe of the industrial working class, especially the Jewish immigrant communities of the late nineteenth century. Chapter One demonstrates that the socialist variants of anarchism were the most important ones within the more general libertarian milieu, where they competed with individualist, liberal and anarcho-capitalist anarchist alternatives and also, often detrimentally, with state-socialism. The latter became increasingly important from 1917, when Vladimir Lenin’s triumphant Bolshevik forces were thought by many radicals to have provided the successful blueprint for the revolutionary movement. Anarchism has often been in debate with Leninism, and as a result, discussion of anarchist tactics goes hand-in-hand with critiques of orthodox marxist strategies.

The powerful, hegemonic influence of Leninism began to fade most significantly after Kruschev’s speech denouncing Stalin. This was followed by the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956, and orthodox Communism continued to decline culminating in the fall of the Soviet Empire in 1989. However, its influence has not entirely disappeared — it still lingers within revolutionary socialist movements, including aspects of anarchist organisational and tactical activities. The significance of the conflict between Leninism and anarchism is one of the major themes of this book, as anarchist methods are partly the result of a rejection of authoritarian socialism. The decline of Leninist movements has also coincided with the weakening in influence of individualist anarchist currents.

Terminology: ‘Liberal Anarchism’

The liberal versions of anarchism had a position of dominance within the relatively restrictive anarchist milieu between the post-Second World War period and the Miners’ Strike of 1984–5; however, since then liberal anarchism has gone into decline, as class struggle groupings have become predominant. The contrast and often conflict between class struggle and liberal traditions is mirrored in America in the clash between social and lifestyle libertarians.[17] The latter, ‘self-centred’ or liberal anarchists, consider the individual to be an ahistoric ‘free-booting, self-seeking, egoistic monad [....] immensely de-individuated for want of any aim beyond the satisfaction of their own needs and pleasures’.[18] Liberal, or lifestyle, anarchists have a view of the individual which is fixed and conforms to the criteria of rational egoism associated with capitalism. The social or class struggle anarchist, by contrast, whilst recognising that individuals are self-motivated and capable of autonomous decision-making, also maintains that agents are historically and socially located.[19] The way individuals act and see themselves is partly a result of their social context, and this formative environment is constantly changing.

By concentrating on class struggle libertarianism, this book stands in contrast to much speculative writing on the subject coming out of universities in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s. Academics such as Robert Wolff and Robert Nozick have associated the term with individualism and economic liberalism.[20]

Postanarchism

The four principles of class struggle anarchism are consistent with contemporary poststructuralist anarchism (sometimes referred to as ‘post-anarchism’ or ‘postanarchism’).[21] Todd May’s The Political Philosophy of Poststructuralist Anarchism[22] has been influential in the development of postanarchisms. May develops a libertarian philosophy that rejects a universal vanguard and asserts the importance of a prefigurative ethic, in which the means are consistent with the ends. This postanarchism is in agreement with the non-essentialist theories of the more politically-engaged contemporary theorists such as Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari.

The moral framework that comes out of the four principles is developed in Chapter Two. This ideal framework, of an anarchism consistent with the key axioms, is evaluated against competing moral theories, in particular those of ends-based moral theories, especially utilitarianism and Leninism, which argue that the justness of an act is based on the outcome. In the technical language of moral philosophy these types of assessment are termed ‘consequentialist’. The anarchist ethic is also contrasted with rights-based moral theories, which considered ends to be unimportant, and held that only the duties and freedoms of individuals matter. These means-based approaches, associated with Immanuel Kant (and referred to as ‘deontology’), inform contemporary liberalisms. Ideal type anarchism differs significantly from these orthodox ethical models, as it holds that the ends must be reflected in the means. This way of thinking is captured in the notion of ‘direct action’, which is of critical importance to current anarchist practice.

Anarchism approves of direct action because, as a liberation movement, it asserts that the oppressed must take the primary role in overthrowing their oppression. Chapter Three identifies the moral agent of change approved by the anarchist ideal. In analysing this concept of the revolutionary agent, the starting point is with the marxist notion of the ‘working class’ based on the economic subjugation of those without control of the means of production. However, this concept is widened beyond a single group with a fixed identity determined wholly by the economy; instead, consistent anarchism recognises that agents of change are multiple and in flux. Oppressive practices combine differently in specific contexts. Whether it is economic subjugation, patriarchy or racism, these forces appear, overlap in different ways depending on context, with no one form having total sway in all contexts.

Such an account stands in contrast to Leninist versions of the revolutionary subject, the influence of which can still be identified in some parts of the libertarian movement. In Leninism the term ‘working class’ refers to solely economic determined identities as opposed to the plethora of radical subjectivities which are denoted in contemporary anarchisms’ uses of the term. This is not to deny the importance of economic conflict. In most, if not all, circumstances, the economic conditions of capitalism play a dominant (but not exclusive) oppressive role, hence the continuation of terminology based in marxist analysis.

Chapters Four and Five identify and classify a wide variety of contemporary anarchist organisational methods and their (anti-political tactics.[23] The division between non-workplace (referred to for convenience as ‘community’) and workplace organisation and the corresponding division in tactics is explored. The ideal type constructed in Chapters Two and Three is used to assess anarchist formal structures and their favoured methods. Many tactics and organisational structures condemned by some critics as inconsistent with anarchism are latterly shown to be reconcilable, in particular contexts, with the prefigurative archetype. However, other stratagems, although normally associated with anarchist practice, are shown to be fundamentally flawed as they create a vanguard acting on behalf of the oppressed.

Scope

The main, but not the only, region under analysis for this study is the area known up until 1922 as the ‘British Isles’. The reason for the inclusion of the 26 County WSM[24] is not due to any imperialist bias but a recognition that English, Scottish, Welsh and the Six Counties’ anarchist histories are intimately linked, partly through anti-imperialism, with that of the 26 counties.[25] The WSM are also important as they represent one version of a particular type of class struggle grouping. These groups use the controversial centralising organisational principles outlined in the Organisational Platform of the Libertarian Communists.[26]

The definition of ‘Britishness’ is geographical rather than cultural, to take into account the contribution of immigrants. One of the first anarchist newspapers printed in this country was written in German, not English. Amongst the earliest major groups of anarchists in Britain was Der Arbeiter Fraint (The Workers’ Friend), comprised of Jewish refugees fleeing from Tsarist persecution, who carried out their activities in Yiddish.[27] In the 1930s, the arrival of Italian and Spanish activists inspired and influenced anarchism in Britain.

The concentration on the British Isles should not overlook the fact that anarchism is an internationalist movement, and organisations often reflect this. In the past, Der Arbeiter Fraint was a member of the cross-channel Federation of Jewish Anarchist Groups in Britain and Paris, while the SolFed is part of the International Workers’ Association of anarcho-syndicalists, which has the Spanish CNT-AIT (Confederacion Nacional del Trabajo — Asociacion Internacional Trabajadores) as its most famous and influential constituent. The AF are part of a wide libertarian communist network including groups on three continents.

Oppression is understood to be contextual and based on opposing dominating forces as they affect that locality, rather than a single universal form of domination that determines all hierarchies As a result, it is not possible to represent the whole anarchist movement through one or two key groups, regions or individuals, or through particular canonical texts. The anarchist movement, to quote the activist George Cores, ‘was due to the activities of working men and women most of whom did not appear as orators or as writers in printed papers’.[28] The types of material considered, and the approach taken here, reflect anarchism’s concern for localised micropolitical, as well as more extensive, global narratives.

An accurate account of anarchism requires a combination of the actors’ own perceptions and an appreciation of the wider context.[29] Accounts based only on the actors’ own perceptions would omit the broader contextualising relationship which helps shape these beliefs.[30] To use an example drawn from the socialist theorist, Andre Gorz, individual soldiers may not be in a position to fully understand their role in the wider military conflict.[31] A comprehensive account of warfare, nonetheless, must still take into account the experiences of service personnel.

The views of anarchist participants are derived from the propaganda sources created by the groups identified above and the analysis of their activities through self-reports, participant-observation and supporting interviews with members of class struggle libertarian groupings. Materials collected and analysed are by no means complete or exhaustive and no such holding exists. A number of the articles, especially of pre-First World War materials, were found at the British Library and the Colindale newspaper depository. The specialist Kate Sharpley Library (KSL) holds many anarchist periodicals, although it too has absences, and access for UK scholars has become more difficult since the archive moved to the United States. Accounts of the main groups have tried to be as complete as possible but the localised nature of many anarchist publications has meant that the concentration has been on those that attempt to be nationally available (but may fall well short). Additionally it must be admitted that an element of chance and arbitrariness is unavoidable in the selection of material.

Texts and Actions

The concentration on both written texts as well as action may seem to contradict the dubious distinction, problematised in the following paragraphs, between writings and events. Anarchists tend to consider the latter to be more important than the former (in certain academic circles they reverse this order by placing greater emphasis on classical texts). George McKay comments that the environmentalists he champions give pre-eminence to deeds over words.[32] This distinction occurs in much anarchist self-analysis. One of the founders of Class War, Ian Bone, for instance, prioritises action as most desirable and criticises former comrades for spending too long on theorising rather than acting. Bone himself is criticised in similar terms by his libertarian opponents.[33] Yet the distinction between deeds and words does not stand up to rigorous scrutiny.

The philosopher J. L. Austin fundamentally collapsed the opposition between speaking and acting in How to do Things with Words. Speaking is an act in itself and not only an abstract expression of meaningful (or meaningless) propositions. Speaking/writing is not just a dispassionate exercise in academic communication but is also an action. Anarchists, including Bone, have also acknowledged this.[34] They reject the rights of organised fascists to speak publicly, for example, as such activities are also recognised as provocative acts and expressions of power. Nationalist newspaper sales, leaflets and public oratory are not merely ways of broadcasting ideas and means for encouraging debate. As speech-acts they also serve to marginalise and exclude sections of society and mark geographical regions as restricted to privileged groups.[35] Speech-acts, then, are performative. So too events have a communicative purpose that can be read textually. An example of direct action, such as tearing up genetically modified crops, can be read as a symbol of wider ecological concern or as a provocative inquiry that questions rights to land ownership. The apparent distinction between theorising and action is really about who is involved in their performance and those whom the act intends to influence.

If speech-acts are activities just like any other, then on what grounds can this study justify concentrating on contemporary events and propaganda, and downplaying classical theoretical texts? The answer involves acknowledging the importance of the identities of the agents involved in the actions and the types of agent appealed to. It is on the grounds of the involvement and identity of active and affected agents that distinctions are drawn between propaganda and theorising. Theorising is interpreted by Bone as discourse created by and towards elite groups (especially those not involved in the events to which the speech acts refer). The greater the distance from those involved or intended to be involved in the acts, the greater designation its designation as mere ‘theory’. This explains Bone’s disapproval of pure theorising, such as discussions in and between revolutionary groups and the organisation of conferences aimed at a select group, over and above the participation of the wider revolutionary agent. Action, then, for Bone, aims at and aspires to include, as autonomous participants, wider groups of individuals — in particular the revolutionary agent of change. Thus certain speech-acts, such as leafleting and speaking tours in response to the activities of organised racists in working class communities, are forms of political action.[36] The same activities in a different context, with a different range of influence, might be dismissed as theorising. Publication and distribution of tracts by the classical anarchist thinkers was originally part of popular agitation. However, in the principal period addressed by this study (1984 -2002), the publication of these same writers is more often associated with distribution to a specialised, academically-privileged audience and therefore designated pejoratively as theorising.[37] To re-cap, the identity of the agents involved in rebellion is fundamental to the demarcation between anarchist and non-anarchist variants of direct action. In anarchist direct action the agents are those immediately affected by the problem under consideration, whereas other forms of direct action promote benevolent (and sometimes malevolent) paternalism.

Drawbacks and Dangers

By undertaking a critique that is sensitive to, and draws heavily upon, the accounts of the activists themselves, the objective is to avoid some of the pitfalls identified by Simon Sadler in the introduction to his book The Situationist City. Sadler notes that university-based researchers engaging in analysis of revolutionary movements (in his case the Situationist International) provoke numerous criticisms from revolutionary activists. These reproaches suggest that the researcher is misrepresenting the subject by using the tools and debates that are the concerns of an intellectual elite rather than the participants themselves, or that the author is domesticating the revolutionary potential of their subject by integrating it into academic discourse. My response differs from Sadler’s reply, although acknowledging the veracity of his rejoinder that the university can provide a means to transmit such ideas, and that the small magazines of the purist revolutionary groups rarely avoid the elitism of which they accuse others. It would be disingenuous to deny that universities (especially the ones which assisted this project) were not elite institutions and that any research, even that which is self-consciously radical, is not only going to be damned by association but risks only being of interest or available to those who seek to police autonomous, egalitarian activity. Nonetheless, efforts have been made to resist the reduction of anarchism into a subject of study for the dominant class, and to this end a particular methodology is employed.

The procedure developed has at its core the recognition that anarchism is primarily a mode of revolutionary action rather than a set of theoretical texts. As a result this book concentrates on the materials of the revolutionary groups, their magazines, newspapers, journals, books, pamphlets, posters, stickers, graffiti and websites as well as describing their actions. This stands in contrast to the approach of many critics of anarchism, such as James Joll, George Woodcock and Peter Marshall, who have examined the movement largely through the supposed canon of the classical anarchist thinkers; but few contemporary anarchists are directly inspired by these writers.

It would be surprising if the thousands participating in libertarian events had read the standard texts by Michael Bakunin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon or Emma Goldman. Consequently the works of the classical writers are referred to, but only in order to elucidate the explanations of more recent activists.

This book attempts to describe contemporary anarchist movements and to show they are significant and important forms of (antipolitical thought. The form of assessment I have developed aims to be sympathetic to, and consistent with, the evaluative techniques of anarchism itself (see above). Yet it does not avoid all the problems associated with ‘academic’ research, despite the fact that for a significant period this text was written external to the university. This was not a matter of principle but due to the unpopularity of the subject, matched maybe by a similar suspicion of the author, amongst grant awarding bodies.

As mentioned above, there is serious concern in avoiding the misrepresentation of past and existing groups, and more importantly in ensuring that no-one’s security is jeopardised by inadvertently making known sources that desire anonymity. Consequently, I am grateful to the many friends in working class and/or anarchist groups who have assisted me and read parts or all of this text to check for such unwarranted disclosures and factual inaccuracies. Nonetheless there are still many weaknesses within the text that I am unable to resolve. Reductionism and omission has unavoidably occurred — even in a document of this size. My apparent tone of confidence in providing a linear narrative is similarly inappropriate for a movement that is contingent, fluid and diffuse. As a result, there are many groups, journals and individuals who have been unjustly excluded (or included to their chagrin) or whose original, thoughtful and inspiring ideas and actions have been diminished or overlooked. In such instances I offer my regrets and hope that these aberrations do not discourage any ‘senseless acts of beauty’ and that my deficiencies cause others to create superior accounts.

Chapter One: Histories of British Anarchism

Foreword

Looking at the histories of anarchism, primarily in the British context, not only helps characterise some of the debates inherited by contemporary libertarians but also illustrates that it is not an isolated national phenomenon, but developed out of worldwide movements. The different guises that class struggle anarchisms have adopted are indicative of their varied tactical and theoretical formulations as well as the diverse contexts in which they have developed.

There is, at present, no single text that covers the history of British anarchism, so this account draws upon a large number of competing, partial accounts. For the pre-First World War period, William Fishman’s and John Quail’s chronologies of Jewish immigrant and indigenous radicalism were used alongside the general histories of anarchism provided by George Woodcock, Peter Marshall and James Joll. Also of significant relevance were the first hand accounts of activists of the period such as Rudolph Rocker and Errico Malatesta and the pamphlets reissued by the Kate Sharpley Library (KSL), an archive that not only preserves anarchist texts but reprints and distributes previously overlooked accounts. These include publishing the autobiographical offerings of militants Tom Brown, Wilf McCartney and George Cores. KSL concentrates on the lived experiences of the ordinary activist rather than the deeds of the leading personalities.

However, many more scholarly works have been useful and inspiring such as Fishman’s (1975) East End Jewish Radicals, Quail’s (1978) Slow Burning Fuse and Daniel Guerin’s (1970) Anarchism. The first stops at the First World War, the second ends in the 1920s with the rise of the hegemonic influence of the Communist Party, and the last ends with the failure of the Spanish Civil War. 1939 is the terminal date of Woodcock’s first edition of Anarchism.[38] Later works, such as Marshall (1992), do include a few brief mentions of more contemporary groups, but these are often side issues to larger historic themes, so they are brief and occasionally inaccurate.[39] Texts by contemporary and near-contemporary activists and organisations provide more comprehensive information. Class struggle newspapers, magazines, pamphlets and websites provide reports of their own events and those of other liberatory movements. The founders of the ABC and Black Flag, Stuart Christie and Albert Meltzer, in their respective autobiographies,[40] as well as in Meltzer’s own histories of British anarchism,[41] include evaluative descriptions of the development of the libertarian milieu. Critical accounts of anarchist activities also appear in orthodox marxist publications such as Socialist Review and Red Action. Reference is also made to reports found in general histories of Britain in which anarchists have played a small part, for instance George Dangerfield’s The Strange Death of Liberal England and, post-war, Nigel Fountain’s Underground and Robert Hewison’s Too Much.[42]

1. Problems in Writing Anarchist Histories

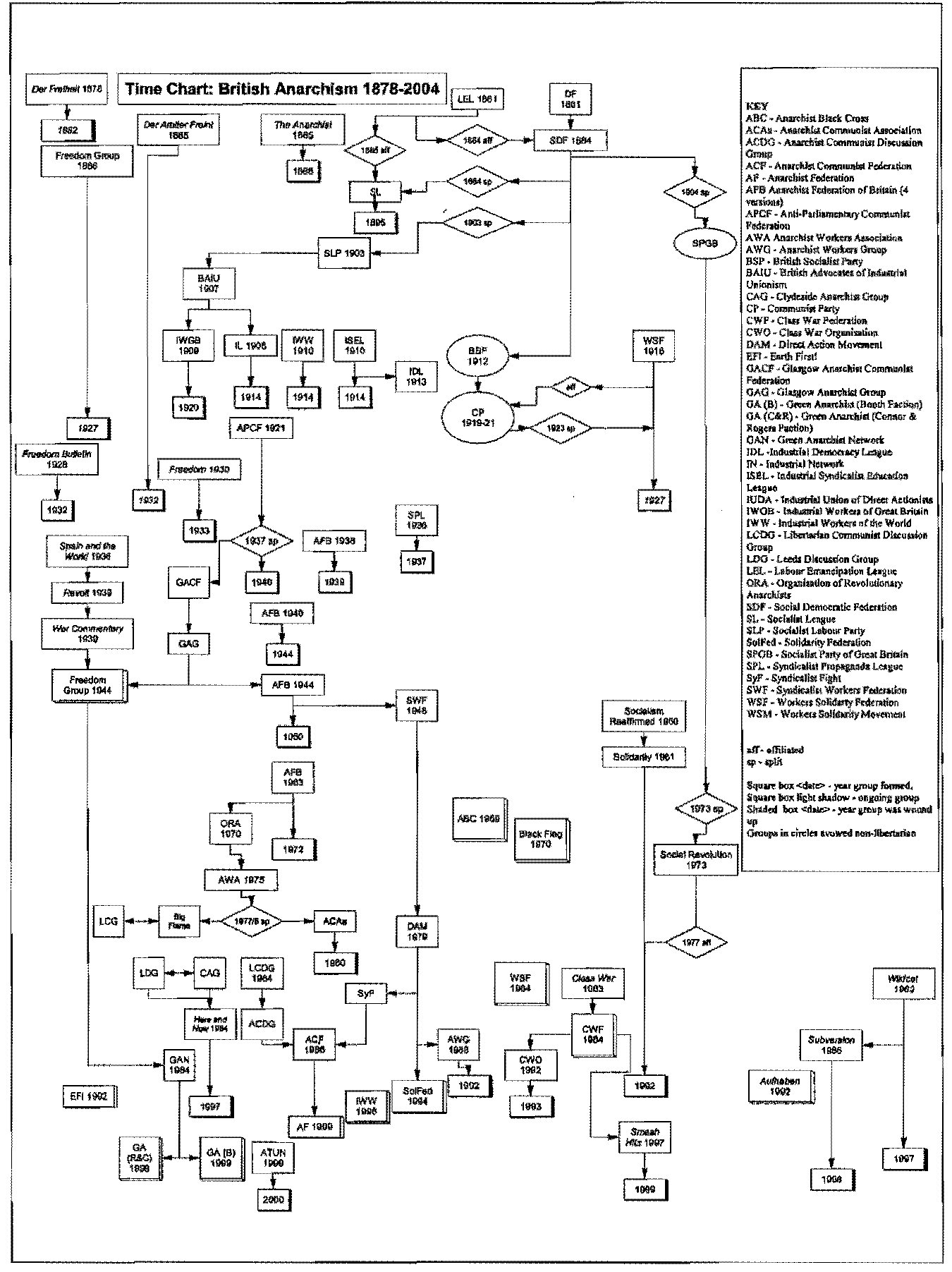

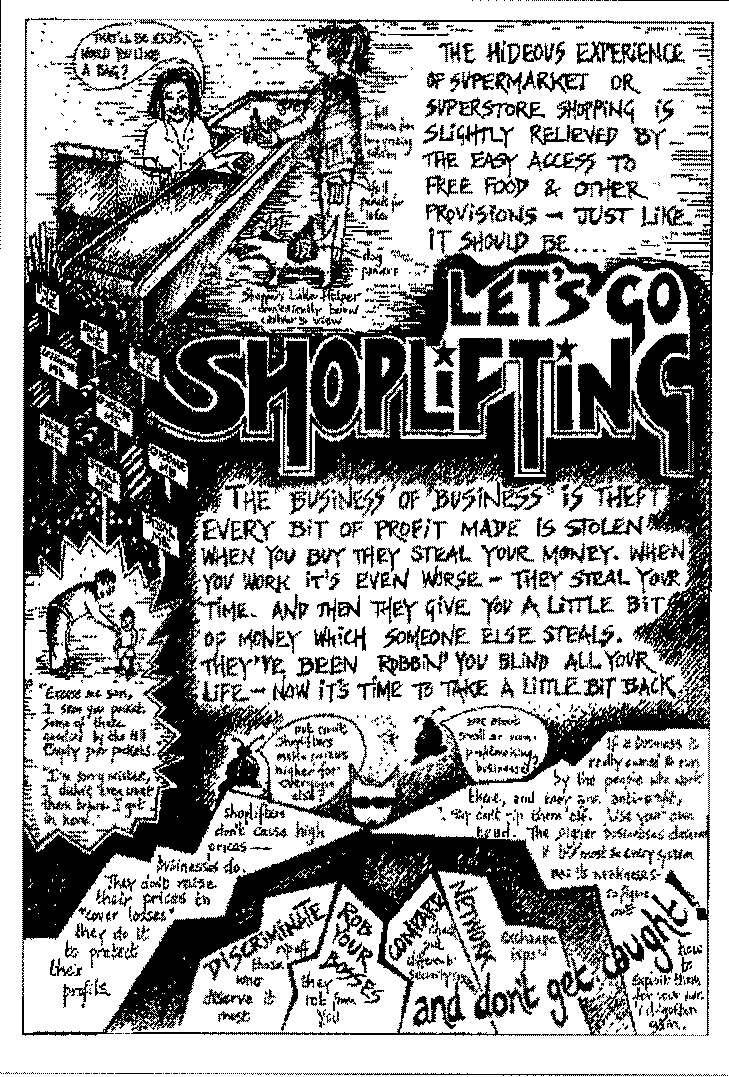

There are enormous difficulties with writing a history of British anarchism and the histogram (fig 1.1.) has unavoidably reproduced some of them. The confusion of groups, with different organisations having the same title, groups affiliating and disaffiliating, appearing, disappearing and reappearing in quick succession, are by no means unique to anarchism but are, nevertheless, significant features of this political movement. These are the consequences of the particular anarchist approaches to organisation; the revolutionary role of the association differs significantly from that of their orthodox socialist and communist counterparts.

Leninists believe that their party is essential to the success of the revolutionary project: ‘The Communist Party is the decisive Party of the working class and necessary to lead it to victory.’[43] More recently, the SWP argues ‘there are those in the West — like members of the Socialist Workers Party — who continue to adhere to revolutionary Leninist organisation and who see it as the only answer to fighting the capitalist system... it is an essential part of working class struggle.’[44] The importance of the party means that organisational integrity is vital; it also has the consequence that Leninist groups tend to keep accurate records that provide a good source of evidence. This is not the case with most anarchist groups.

The types of group proposed by anarchists stress that, as far as possible, formal structures should develop the autonomy of participants, so groups are often federal in structure and maintain a large amount of local initiative. Thus, small groups that nevertheless may have been hugely influential in their locale, have unfortunately been excluded from the histogram. Tracking the multitude of such smaller groups, influential though they may be on particular events, is an almost impossible task. McKay, in his history of post-1960s counterculture, comments on the difficult task of developing a master narrative out of the autonomous events and networks which crisscross the country, but which nevertheless represent an identifiable ‘bricolage or patchwork’ of oppositional activity and culture.[45]

To add to the confusion, prior to the Bolshevik Revolution the divisions within the socialist camps were not hard and fast. Many groups, such as the SDF, contained both statist marxists and anarchists amongst their ranks, and numerous individuals alternated between the two movements. Some did not recognise a distinction or straddled both camps.[46] Even in the 1970s the Libertarian Communist Group (LCG) worked with the non-anarchist Big Flame group and ended up entering the Labour Party.[47]

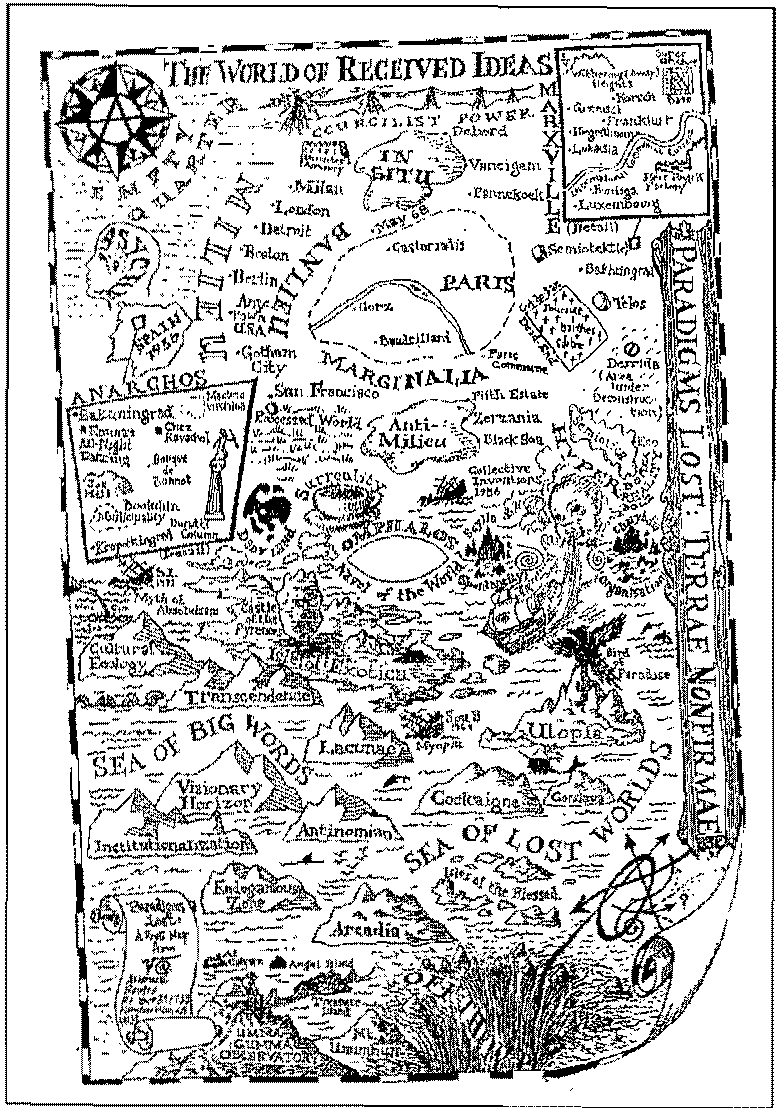

Given the problems of mapping groups coherently, some commentators have presented anarchism spatially, through the interconnectedness of ideas, rather than historically through the interaction of organisation (fig. 1.2.). The diagram from the 1980s libertarian magazine Fatuous Times illustrates the many different theorists and movements that create the terrain of libertarianism. A more contemporary version might extend the area ‘under deconstruction’, given the recent increase in interest between forms of poststructuralism and anarchism from the likes of David Morland, Tadzio Mueller and postanarchists like May and Saul Newman.[48]

2. Origins

The origins of British anarchism are not clear-cut. Many different movements have been posited as precursors, from the Peasant’s Revolt led by Wat Tyler[49], to Winstanley’s Diggers[50] and the Chartists.[51] For European anarchism, Greil Marcus, following Norman Cohn, saw significant anarchistic elements in the religious radicals of the Medieval period.[52] There has been a desire to create a respectable historical tradition for anarchism. This aspiration often leads to the creation of inappropriate forebears and an inaccurate account of the movement. In his history of anarchism, Marshall cites figures as diverse as the conservative theorist Edmund Burke, the nationalist Tom Paine and even the Christian messiah as ‘forerunners of anarchism’ — a revolutionary, anti-state, egalitarian movement.[53] Certainly many of these can be regarded as influences on anarchism as they have inspired many contemporary activists (for instance, Tyler featured in the anti-Poll Tax publicity), rather than being classed as libertarian themselves. Anarchism is, in part, a product of industrialism and post-industrialism, modernity and post-modernity. Actions from preceding eras can be emancipatory and conform to the basic criteria of anarchism, as outlined in the introduction, but the types of subjects or participants are not those associated with anarchism.

3. The Heroic Period: A history of British anarchism up to 1914

Anarchism in Britain had foreign origins but would not have taken root unless there was a native born population receptive to its message and prepared by its own historical experiences. It grew from small and exotic beginnings to become a major cause of concern for the British State and an influence in breaking down divisions of race and ethnicity.

The first person in the modern epoch to use the phrase ‘anarchist’ in a non-pejorative sense was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon who, in his book, What is Property?, declared in 1846, ‘I am an Anarchist.’ In this text he positioned anarchism as a coherent political movement:

“[Y]ou are a republican.” — Republican, yes, but this word defines nothing. Res publica; this is the public thing. Now, whoever is concerned with public affairs, under whatever form of government may call himself a republican. Even kings are republicans. “Well, then you are a democrat?” — No.

— “What! You are a monarchist?” — No. “A constitutionalist?”

— God forbid — “You are then an aristocrat?” — Not at all. -“You want mixed government?” — Still less. — “So then what are you?” I am an anarchist.[54]

And

Although a friend of order, I am, in every sense of the term, an anarchist.[55]

Proudhon gained much support and notoriety in France for his views, yet his ideas remained, for the most part, confined to his native country. Outside of France, interest in Proudhon is mainly due to the interest shown in him by Marx and his reclamation of the name ‘anarchist’. It was Michael Bakunin who spread the ideas of anarchism.[56] It was Bakunin’s, not Proudhon’s, name that appeared in the earliest editions of the anarchist newspapers in Britain.[57]

If the first criterion, self-identification as anarchists, is used to assess the start of the British anarchist movement, then it starts as late as the 1880s and is based on immigrant personalities and influences.[58] The Jewish immigrants who settled in Britain having fled Tsarist persecution were the foundation of a strong anarchist movement, as indeed were similar communities in France and America. Furthermore, Britain received an influx of anarchists from the Continent, fleeing oppression from their countries of origin, amongst them Peter Kropotkin, Errico Malatesta, Johann Most and Rudolph Rocker. The models of anarchism had many international sources but found advocates and sympathisers amongst the native-born as well as recent immigrant communities. Initial hostility between the recent immigrants and the longer established communities was replaced by mutual support between the ethnic groups.

One of the native radical traditions was the Chartist movement, the precursor to the British socialist movement from which the anarchist movement developed. Although the heyday of the Chartists was between 1838–1848, it continued to have an identifiable influence later into the nineteenth century. Joe Lane and Frank Kitz, later to become active in the early anarchist movement, were supporters of the Chartists, the latter having taken part in the Hyde Park rally and disorders.[59] Other broad-based socialist groups and movements grew out of the Chartist clubs, amongst them the Democratic Federation (DF) and the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). These are relevant to the history of British anarchism because there were no clear-cut distinctions between anarchists and other versions of radicalism.

This remained the case until the Bolshevik revolution. Despite the infamous split between Michael Bakunin and Karl Marx in the First International in 1871, many working class activists admired both anarchist and orthodox socialist personalities.[60]

It was out of the DF and SDF that Lane and Kitz launched the Labour Emancipation League (LEL), which according to the ACF (whose account of this period draws upon Quail): ‘was in many ways an organisation that represented the transition of radical ideas from Chartism to revolutionary socialism.’[61] The LEL created the Socialist League (SL), which distributed Kropotkin’s Freedom, although there was mutual suspicion between the anarchists in the League and those of the Freedom Group.[62] Groups such as the DF, SDF and then the SL contained more orthodox (parliamentary) socialists and anarchists, as well as those who flitted between the two positions, as the radicals Cores and McCartney explain.[63] This fluidity between marxist and anarchist movements also indicates a culture of solidarity in pursuit of socialist causes.

The first of the influential foreign revolutionaries to come to Britain was Johann Most. He epitomised one of the ways in which anarchism emerged from the socialist movement. He was originally a radical member of the Social Democratic Party, an elected member of the Reichstag from 1874 to 1878, but moved to a more explicitly anarchist position as he grew older, and he is widely regarded as a leading proponent of ‘propaganda by deed’, violent direct action. Following a contretemps with Bismarck, Most was forced to flee Berlin and arrived in London in 1878. Here he published his newspaper Freiheit in 1879, originally subtitled ‘The Organ of Social Democracy’, but throughout 1880 articles which were more seditious and anarchic in tone were published — by 1882 it was subtitled ‘an Organ of Revolutionary Socialists’. Freiheit thereby stakes a strong claim to being the first anarchist newspaper printed in Britain, although it was intended for export back to Germany.[64]

3.1. Age of Terror

On March 15, 1881, Most held a rally to celebrate the assassination of the Tsar Alexander II that had taken place earlier that year. Four days later, he also wrote an editorial in praise of the killing. In Most’s direct and lurid style, which finds its echo in early editions of Class War and Lancaster Bomber of more recent times, he wrote:

One of the vilest tyrants corroded through and through by corruption is no more [.... the bomb] fell at the despot’s feet, shattered his legs, ripped open his belly and inflicted many wounds [....] Conveyed to his palace, and for an hour and a half in the greatest of suffering, the autocrat meditated on his guilt. Then he died as he deserved to die — like a dog.[65]

For this, Most was arrested for incitement to murder, and was indicted at Bow Street Magistrates Court. The subsequent trial at the Central Criminal Court, the later appeal and the sentence of sixteen months caused much press and public interest, especially as the conviction was considered a restriction on the freedom of the press. The newspaper reports of the trial brought anarchism to a wider public. A week after he was released from prison Most emigrated to New York, taking his periodical with him. However, he did leave behind a group of committed radicals that sought to promote socialism through direct action.

Most’s dramatic support for violent direct action was more fully explained in his book The Science of Revolutionary Warfare, which also gave a detailed account of how to pursue well-prepared guerrilla attacks. In this way it is similar to, although more scientifically accurate than, the more infamous Anarchist Cookbook.[66] Propaganda by deed was frequent on the continent of Europe. The highlights were:

— 1881, the assassination of Russian Tsar Alexander II by the People’s Will.

— 1881, attempt on the life Gambetta, a Republican leader, by Emile Florain.

— 1883–84, bombings, in France, of churches and employers’ houses.

— 1884, a more accurate attempt on the Mother Superior of the convent at Marseilles by Louis Chaves.

— 1891–92, bombing campaign against judiciary and police by Ravachol (ne Koenigstein).

— January 1894, nail bomb attack on the Chamber of Deputies in Paris, by August Vaillant.

— 1900, King Umberto of Italy shot by Gaetano Bresci.

America also faced similar incidents, following state repression of industrial militants. These included Alexander Berkman’s attempt to take the life of Henry Clay Frick in 1892 and the 1901 assassination of President McKinley by Leon Czolgosz. These events promoted the association of anarchism with terrorism throughout Europe and America. There was a general perception that a worldwide conspiracy of assassins existed.[67] Although individual anarchist assassins were aware of the deeds of others from the libertarian press, there was no formal conspiracy.

Because in Britain political repression was less severe than elsewhere in Europe, propaganda by mouth was possible, meaning that propaganda by deed was less frequent. However, this is not to say that the tactic of terror promulgated by Most was utterly neglected here. The Walsall anarchists, Charles, Cailes and Battola, were accused of conspiracy to conduct a terror campaign and held on explosives charges. How far there was any real conspiracy for a French style bombing campaign, or whether it was a pre-emptive strike by the nascent British political police fearing such a campaign, remains a matter of some dispute.[68] More famously there was the 1894 bomb in Greenwich Park, which killed the anarchist who was planting it. The incident at Greenwich was immortalised in Joseph Conrad’s 1907 novel The Secret Agent. Other popular, Active accounts of anarchists as terrorists were Henry James’ (1886) The Princess Casamassima, H. G, Wells’ (1894) The Stolen Bacillus and G, K. Chesterton’s (1908) The Man Who Was Thursday?[69] Journalistic accounts treated anarchism and terrorism synonymously, such that terrorist acts were attributed to anarchists, no matter who carried them out.

The terroristic strand of anarchist activity was also evident in the incidents surrounding Leesma (Flame) cell number 5, a group of anti-tsarist revolutionaries originally from the Letts province of Russia involved in the December 1910 Sidney Street siege. The robbery at a jewellery shop to provide funds for comrades back home went awry. In making their escape the thieves shot dead three policemen and injured two more. The revolutionaries were tracked down to a house at 100 Sidney Street in Stepney in the East End (now a multistorey residential block of flats called ‘Siege House’). The events ended with Winston Churchill, the then Home Secretary, overseeing the deployment of Scots Guards to support the police, creating a 1000-strong combined force to capture two cornered men, Fritz Svaars and William Sokolow. Peter Piaktow (Peter-the-Painter), who is most frequently associated with the events, had already fled. Svaars and Sokolow died in the house.[70] The incidents entered East End mythology; parents would threaten their recalcitrant offspring that if they failed to behave ‘Peter-the-Painter would get them’. Unsuccessful efforts were made to further incriminate the general anarchist movement. The Italian militant, engineer and electrician, Malatesta, was charged with involvement in the crime, as he had innocently provided the gang with the equipment to make a cutting torch, but he was released.[71]

Propaganda by deed was just one form of anarchist activity, although it was the one with which anarchists were most strongly associated. This was not because anarchists placed greater emphasis on this rather than other tactics, but that they were unusual in accepting it as a legitimate tactic, under appropriate circumstances. Propagandists of all types, including Kropotkin, supported it. So although anarchists, like other socialist groupings at the time, were also active in industrial organisation, it was the uniqueness of their occasional advocacy of propaganda by deed that was their most distinctive characteristic. Even some of the French illegalists, who mainly used propaganda by deed, regarded it as just one method amongst many others.[72]

3.2. Workers Arise: Anarchism and industrial organisation

Anarchist industrial organisation had a great influence upon the Jewish immigrants in Britain who had fled from Tsarist Russia. The arrival of these refugees had been met with a marked increase in popular xenophobia. Even the anarchists had been promoters of racism and anti-semitism. The French utopian socialist Charles Fourier, and allegedly Proudhon, had argued that J ews were habitually middlemen and exploiters, incapable of common feeling with their fellow man.[73] The incoming immigrants, desperate for work, were blamed by socialists for strikebreaking and under-cutting pay rates.

Socialists and trade unionists such as Ben Tillett were anti-refugee.[74] By 1888, 43 trade unions had ‘condemned unrestricted immigration’.[75] Many of the native British workers’ groups repeated the stereotypes of Jewry as the parasitical enemies of the gentile population, found in the remarks of Proudhon and Fourier. In the East End, where many of the immigrants settled, the anti-semitism of established left-wing groups assisted in the formation of the ultra-patriotic British Brother’s League. A petition demanding the exclusion of immigrants from Britain attracted 45,000 signatures in Tower Hamlets alone.[76]

Against this background of anti-alien prejudice, Aron Lieberman, a Lithuanian socialist, tried to organise the immigrant poor, first to help them in their plight and second to show the established workers’ movement that the refugees were capable of socialism. The principles of his Hebrew Socialist Union had much in common with anarchism.[77] An alliance of state authorities and the ruling class within the Jewish community (Jewish Chronicle, Board of Guardians and Chief Rabbi’s Office) thwartedLieberman’s plans. The Jewish Chronicle libelled the movement, claiming that it was a front for Christian missionaries. This constituted a particularly effective piece of propaganda, as it questioned the integrity of the movement and united with the dominant culture’s anti-semitic views that Jewry and socialism were incompatible. The Chief Rabbi’s agents also deliberately disturbed the meetings, so that the police were called and the gathering broken up. Partly as a result of this harassment, Lieberman later left for America.

One of Lieberman’s fellow socialists, Morris Winchevsky, set up the first Yiddish socialist journal in Britain, Poilishe Yidl (T7ie Polish Jew). Winchevsky left the paper when it supported the parliamentary candidature of the anti-socialist Sam Montagu, and set up in its place Der Arbeiter Fraint. It quickly gained a distinctive anarchist outlook, promoting equality, liberty, atheism and anti-capitalism (from 1892 it called itself ‘The organ of anarchist communism’). During the period from 1885 to 1896, the group around the paper gained the support of the English-speaking anarchist movement, as well as a sizeable section of the Jewish immigrant community; however it was with the assistance of Rudolf Rocker that its progress was most significant.

Although not Jewish, Rocker had worked with Jewish anarchists in France.[78] In 1895 he had arrived to stay in London and came into contact with the Jewish anarchists there. He was sympathetic to the plight of the refugees and learnt Yiddish in order to help them. In 1898, he went up to Liverpool to edit Der Freie Vort (The Free Word). Its success prompted a request from Der Arbeiter Fraint for Rocker to come back and relaunch their paper. The editorial and presentational skills of Rocker, along with his organisational and agitational abilities, transformed the Jewish movement into one of the most effective anarchist groupings in British history.

Rocker was a syndicalist, and he encouraged the tactic of organising unions. The early Der Arbeiter Fraint had been unenthusiastic, regarding unions as a reformist distraction from building the immediate revolution. They had concentrated instead on communal agitation, particularly against rabbinical authorities. Under Rocker’s lead this workplace strategy was adopted. It proved to be successful. Workplace agitation was attractive to Jewish refugees, as the ruling elite within this ethnic community championed social peace by claiming that Jewish interests were the same, whether worker or owner, whereas unionism recognised the vital differences in circumstances between employee and employer.

Syndicalism was a multi-faceted organisational tactic. It demonstrated the primacy of class division over ethnic division. It was a structure that could bring about a general transformation of society by being part of a General Strike and it could provide the basic administrative framework for the running of the new society.[79] In the short term it also brought about recognisable results. The unions organised effective strikes within the workshops where immigrant workers were found. The growth of radicalism meant that by 7 January 1906 the Jewish Chronicle was reporting that, ‘hardly a day passes without a fresh strike breaking out.’[80] However, the continuing streams of immigrants, desperate and disorientated, provided an ample source of potential strikebreakers.

The period from 1910 to 1914 saw an increase in general industrial militancy with dockers, shipwrights, railwaymen and miners taking major strike action.[81] In 1912 when a strike of largely gentile West End tailors was called, it was feared that East End garment workers would continue working. Der Arbeiter Fraint set to work by calling a general strike. Rocker reports that: ‘Over 8,000 Jewish workers packed the Assembly Hall... More than 3,000 stood outside.’[82] Within two days 13,000 tailors were out on a strike. Throughout the two weeks of the strike (approximately May 10 — 24) Der Arbeiter Fraint appeared daily in order to inform workers of the strike’s progress. It was almost certainly the first and last (to date) daily anarchist paper in Britain. The strike was successful; immigrant and native workers struggled together to improve their lot, winning shorter hours, the abolition of piece work, and an improvement in the sanitation of their working conditions.

The SDF had been unenthusiastic about the role of trade unions, seeing them as restricted to skilled .workers and being little more than friendly societies. In their place, they favoured parliamentary tactics.[83] Yet industrial organisation was becoming more frequent after the mid 1880s. Most unions took a more reformist line like the Trades Union Congress (TUC), but after the turn of the century the more radical Socialist Labour Party (SLP) and an offshoot, the Advocates of Industrial Unionism (AIU), were formed. These bodies increasingly prioritised revolutionary syndicalism over party building, just as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was doing in the USA.[84] The main anarchist section, Kropotkin’s Freedom Group, noticing this move towards industrial organisation, started to produce a syndicalist journal, The Voice of Labour.[85]

Syndicalists did not cause the increased industrial unrest that flared during the early part of the twentieth century but the wave of strikes confirmed that such tactics were a relevant form of action.[86] Although propagandists for syndicalism had little influence on events there was small need for them to do so: agitation in industry was already high and taking a syndicalist direction.[87] Noah Ablett, alongside other members of the unofficial rank-and-file reform committee of the Miners’ Federation of Britain (a forerunner of the National Union of Miners), produced The Miners’ Next Step. It was a lucid statement of revolutionary syndicalism, promoting democratic workers’ bodies to run industry. A pocket of syndicalism continued in Welsh mining communities for decades, even at the height of Communist influence.[88] Fear that the revolutionary industrial message was winning support was such that by 1912 the labour organiser Tom Mann was arrested for publishing a reprint of a leaflet in his paper The Syndicalist asking troops not to shoot at strikers. The Syndicalist was the newspaper of the Industrial Syndicalist Education League and claimed a circulation of 20,000.[89] The authorities clearly felt that his message might find a receptive audience. The political motivation behind Mann’s arrest is even more stark when one considers that a year later the Conservative Party leader, Andrew Bonar Law, called on the army to mutiny over the issue of Home Rule for Ireland, without facing any similar prosecution.[90]

3.3. Propaganda and Anarchist Organisation

In the last two decades of the nineteenth century there were a number of anarchist newspapers available that began to reflect the diversity of anarchist methods and beliefs. The aforementioned Freiheit, with its links to revolutionary socialism and propaganda by deed, spawned an English language version in 18 82, published to rally support for Johann Most during his trial. Extending the tradition back into British working class struggle was the former Chartist Dan Chatterton’s Commune — the Atheist Scorcher of 1884.[91] Also published in this era was Henry Seymour’s The Anarchist and a fellow individualist-anarchist paper from the USA, Benjamin Tucker’s Liberty.[92] Anarchist newspapers of all kinds provided both a means of propaganda as well as a tangible product around which an organisation could be based. The papers acted as a means of communicating with other socialist militants and with the workers (the potential agents of social change). Newssheets enabled the co-ordination of tactics such as public meetings, rallies and strikes. Their distribution at rallies and meetings helped to put individuals in touch with groups and clubs. Successful periodicals also provided a source of finance: the importance of the newspaper to the revolutionary movement is discussed in more detail in the last chapter.

The activists behind Der Arbeiter Fraint created anarchist meeting places in Whitechapel in London which acted like more recent radical social centres such as Emmaz in London, 1 in 12 Centre in Bradford and The Chalkboard in Glasgow. Like the contemporary versions, the Jubilee Street club organised educational as well as social events. Entertainments such as dances attracted wider sections of working class communities into the anarchist milieu. Even if the participants did not become full anarchist militants, they were, at least, more likely to be sympathetic. Through lectures and anarchist papers, the clubs provided a source of radical ideas and debate — an arena in which to clarify and exchange political theories.

Newspapers, too, provided a role for such interchange. Seymour’s The Anarchist, for example, printed articles discussing the differences between individualism, anarchist socialism and ‘collectivist socialism’.[93] Seymour invited Kropotkin to contribute, but the association did not last long — the collaboration lasted just one issue.[94] Kropotkin and his followers set up their own anarchist paper, Freedom, in 1886, which became Britain’s most important English-language anarchist paper for the next 35 years.[95]

From the beginning, Freedom developed alliances with socialist and anarchist groups and periodicals throughout Britain and beyond.[96] By building up a wide coalition of sympathisers they could mobilise support far exceeding the formal membership of anarchist organisations. The willingness of socialists and anarchists, immigrants and locals to work together was evident in the large demonstrations against Tsarist oppression.[97] This co-operation helped Malatesta when in 1912 he faced deportation after being found guilty of criminal libel, for suggesting that an Italian called Belleli was ‘a police spy’. A campaign was started calling for his release that united labour, socialist and anarchist movements. Support came from trade unionists such as the London Trades’ Council, Der Arbeiter Fraint group, the Independent Labour Party (ILP) andMPs such as George Lansbury and J. C. Wedgewood.[98]

Debate and solidarity does not mean that there were not also significant theoretical differences between the groups . One of the principal ones has been between the industrial organisation of anarcho-syndicalism and the wider communal structures of anarchist communism. Another has been on theories of distribution and exchange based on mutualism, collectivism or communism: each suggested different forms of organisation, different tactics and appealed to distinct types of agency.

3.4. Ideological Differences in Class-Struggle Anarchism

With Kropotkin’s growing influence within British anarchism, the movement was becoming increasingly anarchist communist. This move from mutualism and collectivism to communism was not merely a change of name but a shift in specific ideals. Collectivism, promoted by Bakunin, was a system of distribution whereby commodities were given a value based on the number of labour hours necessary to produce them. These were then to be exchanged with goods that had an equal labour value. A day’s work by a surgeon was worth exactly the same as that done by a plumber. If barter was not possible, then labour vouchers recording the labour-value of the product would be provided and exchanged for goods. Labour was the key to value — it could be centrally determined by a collective council of labourers. Consequently collectivism was often associated with syndicalism, although some syndicalists have been anarchist communists, especially since the end of the Second World War.

Mutualism, a system preferred by Proudhon, was an intermediary stage towards a fully collectivist economy. At the centre of the operation was the Peoples’ Bank, a non-profit, non-interest charging organisation. Mutualists would join the bank as co-operative groups of workers. Labour cheques would be converted into the currency of the period until the economy was fully mutualist. The bank would sell the members’ products on the open market, with the market, rather than a committee, deciding the value of the goods.[99] As more groups entered the People’s Bank, the power of the state and capital would diminish, allowing people to enter into free contracts with each other based on the principle that ‘A day’s work equals a day’s work’[100]

Anarchist communism was a break with collectivism and mutualism. For Kropotkin these systems were a recreation of the wage economy, with labour vouchers replacing traditional capitalist currencies.[101] In his introduction to anarchist communism, Berkman explains some of the areas of disagreement between the mutualist and the communist anarchists. First, mutualists believed that an anarchist society could come about without a social revolution, through the progress of the People’s Bank, while anarchist communists argued that the ruling class would use force to protect their privileged position. Second, mutualists believed in the immutability of private property rights, while anarchist communists held that use determined ownership — the means of production should be free and equally accessible to all. Third, for mutualists the ideal was for a society without government, where voluntary commercial transactions would become the norm and such free market activity would prevent the build up of monopolies. Anarchist communists on the other hand desired the abolition of the market economy.[102]

Anarchist communists also dismissed the labour vouchers system that had been the basis for collectivism. How could equivalent labour time create equivalent value? ‘Suppose the carpenter worked three hours to make a kitchen chair, while the surgeon took only half an hour to perform an operation that saved your life. If the amount of labour used determines value, then the chair is worth more than your life. Obvious nonsense.’[103] The surgeon’s training might, also, be no longer than an artisan’s apprenticeship. Furthermore, it is hard to determine where and when labour starts for certain professions, such as for acting, writing or child-minding.

Freedom under Kropotkin’s editorship pursued a clear anarchist communist line. It considered mutualism and Bakuninist collectivism to be little better than capitalism. Mutualists aim:

[T]o secure every individual neither more nor less than the exact amount of wealth resulting from the exercise of his own capacities. Are not the scandalous inequalities in the distribution of wealth today merely the culminative effect of the principle that every man is justified in securing to himself everything that his chances and capacities enable him to lay his hands on.[104]

Individualist-anarchism, which has similarities with, but is not identical to, anarcho-capitalism, was condemned on the same grounds. Anarchist communism became throughout the end of the nineteenth century the dominant current in British libertarianism.

Even in the period prior to the First World War, the separation between workplace and community organisation, which was regarded as the distinction between anarcho-syndicalism and anarchist communism, was often more tactical than universal. Anarchist communists were active in industrial organisation as well as supporting propaganda by deed. Kropotkin himself defended certain of these spectacular acts and also wrote of the need for revolutionary syndicates.[105] Propaganda was carried out on two fronts: industrial activism and community organisation. As a result of working on these different fronts, links were built across anarchist groups and into the wider socialist and labour movements.

Propaganda by word, through meetings, rallies, papers and pamphlets, was not a pacifist alternative to other forms of action. Liberal commentators are often embarrassed by Kropotkin’s advocacy of both industrial methods and propaganda by deed, as well as respectable propaganda by word.[106] These were not, however, mutually exclusive currents, but complementary measures. Each was used independently or in combination, depending on circumstances, to develop and encourage emancipation for the oppressed classes from repressive situations. By 1914 the anarchist movement was still marginal in terms of its numbers, but anarchist ideas on tactics and objectives had grown into a minority current in many industries and had permeated into various large communities. However, at this point the movement went into rapid decline. The reasons for this are not hard to discern.

4. Anarchism During the First World War, 1914 — 1918

With the outbreak of war, anarchism’s advocacy of anti-militarism and internationalism was out of keeping with the new jingoistic mood throughout Europe. The excitementofinnovativeformsofbattleseemed far more enticing than the outmoded idea of universal fellowship. The start of international conflict also meant that prominent refugee organisers were interned as enemy aliens. For Rocker, this included being held on a prison ship moored off the south coast.[107] He was not released until 1918 and then only into The Netherlands. He remained an active anarchist setting up the anarcho-syndicalist International Workers’ Association in 1922, but he never returned to Britain.

The war not only lost potential recruits to the anarchist cause through conscription but, as Meltzer suggests, it also provided a cover for the British State to use political foul play against its opponents. Evidence to support this allegation includes the significant number of disappearances of radicals during the period of the First World War.[108] As a result, the talk held on the 5th of February, 1915 by Der Arbeiter Fraint, entitled ‘The Present Crisis’, could be seen as a commentary on the precarious state of the anarchist movement as much as the European wartime situation.

Those socialists who had remained loyal to their internationalist ideals during the feverish jingoism of the early war years had forged a strong bond of unity. ‘Everywhere the Socialists were aggressive and everywhere they moved in solidarity. No attention was paid to party barriers’.[109] As the conflict continued and the casualties mounted in horrifying numbers, nationalistic fervour began to diminish. As a result, the revolutionary anti-war movement, of which anarchism had been a part (Kropotkin’s support for the allies being a rare exception), began to regain public support. They received a further short term fillip with the successful Russian Revolutions of 1917 (February and October), although the latter was shortly to have a devastating effect on the global anarchist movement.