Aufheben

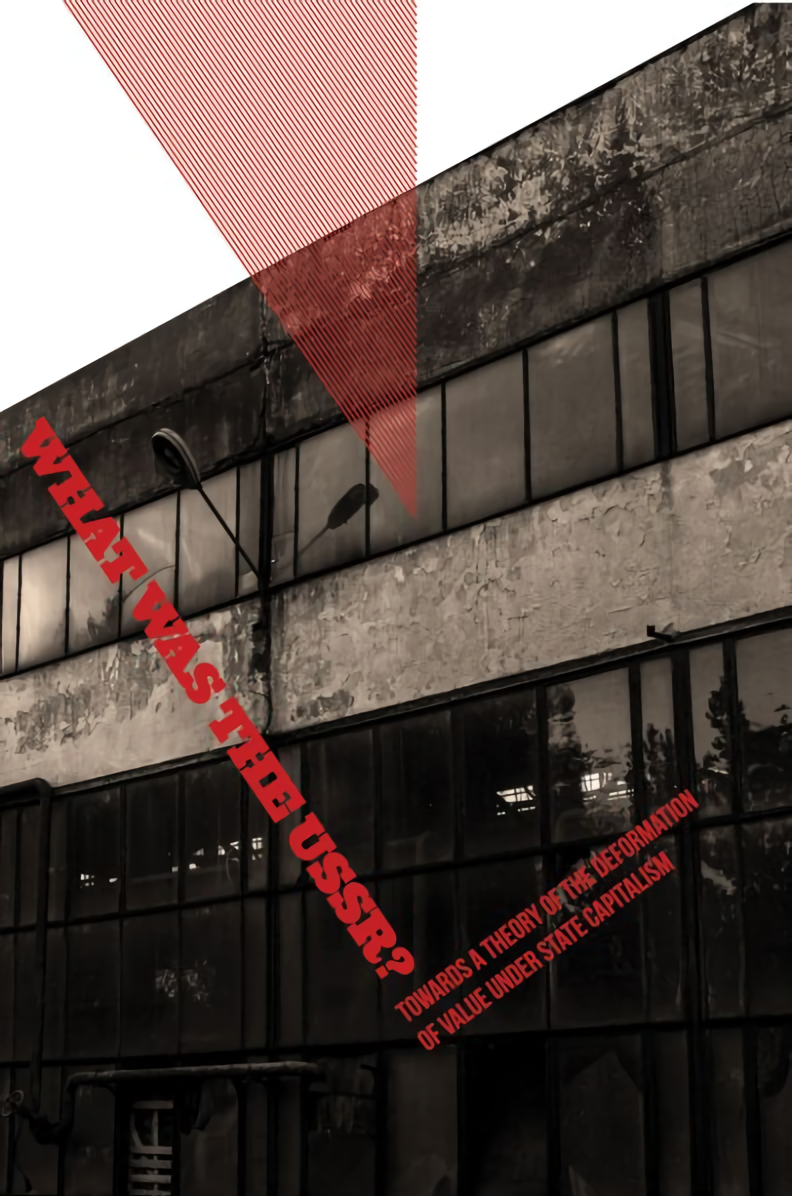

What was the USSR?

Towards a Theory of the Deformation of Value Under State Capitalism

Part I: Trotsky and state capitalism

The question of Russia once more

Trotsky’s theory of the Soviet Union as a degenerated workers’ state

Trotsky and the Orthodox Marxism of the Second International

Trotsky and the theory of permanent revolution

Trotsky and the perils of transition

The NEP and the Left Opposition

Preobrazhensky’s theory of primitive accumulation

Trotsky and the Leninist conception of party, class and the state

The degeneration of the revolution

Trotsky and the question of transition

The theory of the USSR as a form of state capitalism within Trotskyism

The theory of state capitalism and the second crisis in Trotskyism

Cliff and the neo-Trotskyist theory of the USSR as state capitalist

The flaws in Cliff’s theory of state capitalism

Part II: Russia as a Non-mode of Production

The origins of Ticktin’s theory of the USSR

Ticktin and the reconstruction of Trotskyism

Ticktin and Trotsky’s theory of the transitional epoch

Ticktin and the failure of Trotsky

Ticktin and the political economy of the USSR

The question of commodity fetishism and ideology in the USSR

Problems of Ticktin’s ‘political economy of the USSR’

The Question of the Transitional Epoch

Part III: Left Communism and the Russian Revolution

Organic Reconstruction: Back to Orthodoxy

Lenin’s Arguments for State Capitalism Versus the Left Communists

New Economic Policy: New Opposition

The German/Dutch Communist Left

The German Revolution: Breaking from Social Democracy

The German Left and the Comintern

The spectre of Menshevism: October, a bourgeois revolution?

Mattick: Its capitalism, Jim, but not as we know it

Part IV: Towards a theory of the deformation of value

The capitalist essence of the USSR

Capitalist crisis and the collapse of the USSR

The historical significance of state capitalism

Germany and the conditions of late industrialisation

Mercantile and Industrial capitalism

Russia and the problem of underdevelopment

The problem of the nature of the USSR restated

The circuits of industrial capital

To what extent did the Commodity-form exist in the USSR?

To what extent did commodity-production exist in the USSR?

To what extent did commodity exchange exist in the USSR?

To what extent did Money exist in the USSR?

Contradictions in the USSR: the production of defective use-values

Part I: Trotsky and state capitalism

The Russian Revolution and the subsequent establishment of the USSR as a ‘workers’ state’, has dominated political thinking for more than three generations.

In the past, it seemed enough for communist revolutionaries to define their radical separation with much of the ‘left’ by denouncing the Soviet Union as state capitalist.[1] This is no longer sufficient, if it ever was. Many Trotskyists, for example, now feel vindicated by the ‘restoration of capitalism’ in Russia. To transform society we not only have to understand what it is, we also have to understand how past attempts to transform it failed. In this and future issues we shall explore the inadequacies of the theory of the USSR as a degenerated workers’ state and the various versions of the theory that the USSR was a form of state capitalism.

Introduction

The question of Russia once more

In August 1991 the last desperate attempt was made to salvage the old Soviet Union. Gorbachev, the great reformer and architect of both Glasnost and Perestroika, was deposed as President of the USSR and replaced by an eight man junta in an almost bloodless coup. Yet, within sixty hours this coup had crumbled in the face of the opposition led by Boris Yeltsin, backed by all the major Western powers. Yeltsin’s triumph not only hastened the disintegration of the USSR but also confirmed the USA as the final victor in the Cold War that had for forty years served as the matrix of world politics.

Six years later all this now seems long past. Under the New World (dis)Order in which the USA remains as the sole superpower, the USSR and the Cold War seem little more than history. But the collapse of the USSR did not simply reshape the ‘politics of the world’ — it has had fundamental repercussions in the ‘world of politics’, repercussions that are far from being resolved.

Ever since the Russian Revolution in 1917, all points along the political spectrum have had to define themselves in terms of the USSR, and in doing so they have necessarily had to define what the USSR was. This has been particularly true for those on the ‘left’ who have sought in some way to challenge capitalism. In so far as the USSR was able to present itself as ‘an actually existing socialist system’, as a viable alternative to the ‘market capitalism of the West’, it came to define what socialism was.

Even ‘democratic socialists’ in the West, such as those on the left of the Labour Party in Britain, who rejected the ‘totalitarian’ methods of the Lenin and the Bolsheviks, and who sought a parliamentary road to socialism, still took from the Russian model nationalization and centralized planning of the commanding heights of the economy as their touchstone of socialism. The question as to what extent the USSR was socialist, and as such was moving towards a communist society, was an issue that has dominated and defined socialist and communist thinking for more than three generations.

It is hardly surprising then that the fall of the USSR has thrown the left and beyond into a serious crisis. While the USSR existed in opposition — however false — to free market capitalism, and while social democracy in the West continued to advance, it was possible to assume that history was on the side of socialism. The ideals of socialism and communism were those of progress. With the collapse of the USSR such assumptions have been turned on their head. With the victory of ‘free market capitalism’ socialism is now presented as anachronistic, the notion of centralized planning of huge nationalized industries is confined to an age of dinosaurs, along with organized working class struggle. Now it is the market and liberal democracy that claim to be the future, socialism and communism are deemed dead and gone.

With this ideological onslaught of neo-liberalism that has followed the collapse of the USSR, the careerists in the old social democratic and Communist Parties have dropped all vestiges old socialism as they lurch to the right. With the Blairite New Labour in Britain, the Clintonite new Democrats in the USA and the renamed Communist Parties in Europe, all they have left is to openly proclaim themselves as the ‘new and improved’ caring managers of capitalism, fully embracing the ideals of the market and modern management methods.

Of course, for the would-be revolutionaries who had grown up since the 1960s, with the exception of course of the various Trotskyist sects, the notion that the USSR was in anyway progressive, let alone socialist or communist, had for a long time seemed ludicrous. The purges and show trials of the 1930s, the crushing of the workers’ uprisings in East Germany in 1953 and in Hungary in 1956, the refusal to accept even the limited liberal reforms in Czechoslovakia in 1968 and the continued repression of workers’ struggles in Russia itself, had long led many on the ‘revolutionary left’ to the conclusion that whatever the USSR was it was not socialist. Even the contention that, for all its monstrous distortions, the USSR was progressive insofar as it still developed the productive forces became patently absurd as the economic stagnation and waste of the Brezhnev era became increasingly apparent during the 1970s.

For those ultra-leftists[2] and anarchists who had long since rejected the USSR as in anyway a model for socialism or communism, and who as a result had come to reassert the original communist demands for the complete abolition of wage labour and commodity exchange, it has long since become self-evident that the USSR was simply another form of capitalism. As such, for both anarchists and ultra-leftists the notion that the USSR was state capitalist has come as an easy one — too easy perhaps.

If it was simply a question of ideas it could have been expected that the final collapse of the USSR would have provided an excellent opportunity to clear away all the old illusions in Leninism and social democracy that had weighed like a nightmare on generations of socialists and working class militants. Of course this has not been the case, and if anything the reverse may be true. The collapse of the USSR has come at a time when the working class has been on the defensive and when the hopes of radically overthrowing capitalism have seemed more remote than ever. If anything, as insecurity grows with the increasing deregulation of market forces, and as the old social democratic parties move to the right, it would seem if anything that the conditions are being lain for a revival of ‘old style socialism’.

Indeed, freed from having to defend the indefensible, old Stalinists are taking new heart and can now make common cause with the more critical supporters of the old Soviet Union. This revivalism of the old left, with the Socialist Labour Party in Britain as the most recent example, can claim to be making just as much headway as any real communist or anarchist movement.

The crisis of the left that followed the collapse of the USSR has not escaped communists or anarchists. In the past it was sufficient for these tendencies to define their radical separation with much of the ‘left’ by denouncing the Soviet Union as state capitalist and denying the existence of any actually existing socialist country. This is no longer sufficient, if it ever was. As we shall show, many Trotskyists, for example, now feel vindicated by the ‘restoration of capitalism’ in Russia. Others, like Ticktin, have developed a more sophisticated analysis of the nature of the old USSR, and what caused its eventual collapse, which has seriously challenged the standard theories of the USSR as being state capitalist.

While some anarchists and ultra-leftists are content to repeat the old dogmas concerning the USSR, most find the question boring; a question they believe has long since been settled. Instead they seek to reassert their radicality in the practical activism of prisoner support groups (‘the left never supports its prisoners does it’),[3] or in the theoretical pseudo-radicality of primitivism. For us, however, the question of what the USSR was is perhaps more important than ever. For so long the USSR was presented, both by socialists and those opposed to socialism, as the only feasible alternative to capitalism. For the vast majority of people the failure and collapse of the USSR has meant the failure of any realistic socialist alternative to capitalism. The only alternatives appear to be different shades of ‘free market’ capitalism. Yet it is no good simply denouncing the USSR as having been a form of state capitalism on the basis that capitalism is any form of society we don’t like! To transform society we not only have to understand what it is, we also have to understand how past attempts to transform it failed.

Outline

In this issue and the next one we shall explore the inadequacies of various versions of the theory that the USSR was a form of state capitalism; firstly when compared with the standard Trotskyist theory of the Soviet Union as a degenerated workers’ state, and secondly, and perhaps more tellingly, in the light of the analysis of the USSR put forward by Ticktin which purports to go beyond both state capitalist and degenerated workers’ state conceptions of the nature of the Soviet Union.

To begin with we shall examine Trotsky’s theory of the USSR as a degenerated workers’ state, which, at least in Britain, has served as the standard critical analysis of the nature of the Soviet Union since the 1930s. Then we shall see how Tony Cliff, having borrowed the conception of the USSR as state capitalist from the left communists in the 1940s, developed his own version of the theory of the USSR as a form of state capitalism which, while radically revising the Trotskyist orthodoxy with regard to Russia, sought to remain faithful to Trotsky’s broader theoretical conceptions. As we shall see, and as is well recognized, although through the propaganda work of the SWP and its sister organizations world wide Cliff’s version of the state capitalist theory is perhaps the most well known, it is also one of the weakest. Indeed, as we shall observe, Cliff’s theory has often been used by orthodox Trotskyists as a straw man with which to refute all state capitalist theories and sustain their own conception of the USSR as a degenerated workers’ state.

In contrast to Cliff’s theory we shall, in the next issue, consider other perhaps less well known versions of the theory of the USSR as state capitalist that have been put forward by left communists and other more recent writers. This will then allow us to consider Ticktin’s analysis of USSR and its claim to go beyond both the theory of the USSR as state capitalist and the theory of the USSR as a degenerated workers’ state.

Having explored the inadequacies of the theory that the USSR was a form of state capitalism, in the light of both the Trotskyist theory of the Soviet Union as a degenerated workers’ state and, more importantly, Ticktin’s analysis of the USSR, we shall in Aufheben 8 seek to present a tentative restatement of the state capitalist theory in terms of a theory of the deformation of value.

Trotsky’s theory of the Soviet Union as a degenerated workers’ state

Introduction

It is now easy to deride those who have sought, however critically, to defend the USSR as having been in some sense ‘progressive’. Yet for more than a half a century the ‘defence of the Soviet Union’ was a central issue for nearly all ‘revolutionary socialists’, and is a concern that still persists today amongst some. To understand the significance of this it is necessary to make some effort to appreciate the profound impact the Russian Revolution must have had on previous generations of socialists and working class militants.

I The Russian Revolution

It is perhaps not that hard to imagine the profound impact the Russian Revolution had on the working class movements at the time. In the midst of the great war, not only had the working masses of the Russian Empire risen up and overthrown the once formidable Tsarist police state, but they had set out to construct a socialist society. At the very time when capitalism had plunged the whole of Europe into war on an unprecedented scale and seemed to have little else to offer the working class but more war and poverty, the Russian Revolution opened up a real socialist alternative of peace and prosperity. All those cynics who sneered at the idea that the working people could govern society and who denied the feasibility of communism on the grounds that it was in some way against ‘human nature’, could now be refuted by the living example of a workers’ state in the very process of building socialism.

For many socialists at this time the revolutionary but disciplined politics of Bolsheviks stood in stark contrast to the wheeler-dealing and back-sliding of the parliamentary socialism of the Second International. For all their proclamations of internationalism, without exception the reformist socialist parties of the Second International had lined up behind their respective national ruling classes and in doing so had condemned a whole generation of the working class to the hell and death of the trenches. As a result, with the revolutionary wave that swept Europe following the First World War, hundreds of thousands flocked to the newly formed Communist Parties based on the Bolshevik model, and united within the newly formed Third International directed from Moscow. From its very inception the primary task of the Third International was that of building support for the Soviet Union and opposing any further armed intervention against the Bolshevik Government in Russia on the part of the main Western Powers. After all it must have seemed self-evident then that the defence of Russia was the defence of socialism.

II The 1930s and World War II

By the 1930s the revolutionary movements that had swept across Europe after the First World War had all but been defeated. The immediate hopes of socialist revolution faded in the face of rising fascism and the looming prospects of a second World War in less than a generation. Yet this did not diminish the attractions of the USSR. On the contrary the Soviet Union stood out as a beacon of hope compared to the despair and stagnation of the capitalist West.

While capitalism had brought about an unprecedented advance in productive capacity, with the development of electricity, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, cars, radios and even televisions, all of which promised to transform the lives of everyone, it had plunged the world into an unprecedented economic slump that condemned millions to unemployment and poverty. In stark contrast to this economic stagnation brought about by the anarchy of market forces, the Soviet Union showed the remarkable possibilities of rational central planning which was in the process of transforming the backward Russian economy. The apparent achievements of ‘socialist planning’ that were being brought about under Stalin’s five-year plans not only appealed to the working class trapped in the economic slump, but also to increasing numbers of bourgeois intellectuals who had now lost all faith in capitalism.

Of course, from its very inception the Soviet Union had been subjected to the lies and distortions put out by the bourgeois propaganda machine and it was easy for committed supporters of the Soviet Union, whether working class militants or intellectuals, to dismiss the reports of the purges and show trials under Stalin as further attempts to discredit both socialism and the USSR. Even if the reports were basically true, it seemed a small price to pay for the huge and dramatic social and economic transformation that was being brought about in Russia, which promised to benefit hundreds of millions of people and which provided a living example to the rest of the world of what could be achieved with the overthrow of capitalism. While the bourgeois press bleated about the freedom of speech of a few individuals, Stalin was freeing millions from a future of poverty and hunger.

Of course not everyone on the left was taken in by the affability of ‘Uncle Joe’ Stalin. The purge and exile of most of the leaders of the original Bolshevik government, the zig-zags in foreign policy that culminated in the non-aggression pact with Hitler, the disastrous reversals in policy imposed on the various Communist Parties through the Third International, and the betrayal of the Spanish Revolution in 1937, all combined to cast doubts on Stalin and the USSR.

Yet the Second World War served to further enhance the reputation of the Soviet Union, and not only amongst socialists. Once the non-aggression pact with Germany ended in 1940, the USSR was able to enter the war under the banner of anti-fascism and could claim to have played a crucial role in the eventual defeat of Hitler. While the ruling classes throughout Europe had expressed sympathy with fascism, and in the case of France collaborated with the occupying German forces, the Communist Parties played a leading role in the Resistance and Partisan movements that had helped to defeat fascism. As a result, particularly in France, Italy, Yugoslavia and Greece, the Communist Parties could claim to be champions of the patriotic anti-fascist movements, in contrast to most of the Quisling bourgeois parties.

III The 1950s

The Second World War ended with the USA as the undisputed superpower in the Western hemisphere, but in the USSR she now faced a formidable rival. The USSR was no longer an isolated backward country at the periphery of world capital accumulation centred in Western Europe and North America. The rapid industrialization under Stalin during the 1930s had transformed the Soviet Union into a major industrial and military power, while the war had left half of Europe under Soviet control. With the Chinese Revolution in 1949 over a third of human kind now lived under ‘Communist rule’!

Not only this. Throughout much of Western Europe, the very heartlands and cradle of capitalism, Communist Parties under the direct influence of Moscow, or social democratic parties with significant left-wing currents susceptible to Russian sympathies, were on the verge of power. In Britain the first majority Labour government came to power with 48 per cent of the vote, while in Italy and France the Communist Parties won more than a third of the vote in the post-war elections and were only kept from power by the introduction of highly proportional voting systems.

What is more, few in the ruling circles of the American or European bourgeoisie could be confident that the economic boom that followed the war would last long beyond the immediate period of post-war reconstruction. If the period following the previous World War was anything to go by, the most likely prospect was of at best a dozen or so years of increasing prosperity followed by another slump which could only rekindle the class conflicts and social polarization that had been experienced during 1930s. Yet now the Communist Parties, and their allies on the left, were in a much stronger starting position to exploit such social tensions.

While the West faced the prospects of long term economic stagnation, there seemed no limits to the planned economic growth and transformation of the USSR and the Eastern bloc. Indeed, even as the late as the early 1960s Khrushchev could claim, with all credibility for many Western observers, that having established a modern economic base of heavy industry under Stalin, Russia was now in a position to shift its emphasis to the expansion of the consumer goods sector so that it could outstrip the living standards in the USA within ten years!

It was this bleak viewpoint of the bourgeoisie, forged in the immediate post-war realities of the late 1940s and early 1950s, which served as the original basis of the virulent anti-Communist paranoia of the Cold War, particularly in the USA; from the anti-Communist witch-hunts of the McCarthy era to Reagan’s ‘evil empire’ rhetoric in the early 1980s.

For the bourgeoisie, expropriation by either the proletariat or by a Stalinist bureaucracy made little difference. The threat of communism was the threat of Communism. To the minds of the Western bourgeoisie the class struggle had now become inscribed in the very struggle between the two world superpowers: between the ‘Free World’ and the ‘Communist World’.[4]

This notion of the struggle between the two superpowers as being at one and the same time the final titanic struggle between capital and labour was one that was readily accepted by many on the left. For many it seemed clear that the major concessions that had been incorporated into the various post-war settlements had been prompted by the fear that the working class in the West, particularly in Western Europe, would go over to Communism. The post-war commitments to the welfare state, full employment, decent housing and so forth, could all be directly attributed to the bourgeoisie’s fear of both the USSR and its allied Communist Parties in the West. Furthermore, despite all its faults, it was the USSR who could be seen to be the champion the millions of oppressed people of the Third World with its backing for the various national liberation movements in their struggles against the old imperialist and colonial powers and the new rapacious imperialism of the multinationals.

In this view there were only two camps: the USSR and the Eastern bloc, which stood behind the working class and the oppressed people of the world, versus the USA and the Western powers who stood behind the bourgeoisie and the propertied classes. Those who refused to take sides were seen as nothing better than petit-bourgeois intellectuals who could only dwell in their utopian abstractions and who refused to get their hands dirty in dealing with current reality.

Of course, by the early 1950s the full horrors and brutality of Stalin’s rule had become undeniable. As a result many turned towards reformist socialism embracing the reforms that had been won in the post-war settlement. While maintaining sympathies for the Soviet Union, and being greatly influenced by the notion of socialism as planning evident in the USSR, they sought to distance themselves from the revolutionary means and methods of bolshevism that were seen as the cause of the ‘totalitarianism’ of Russian Communism. This course towards ‘democratic socialism’ was to be followed by the Communist Parties themselves 20 years later with the rise of so-called Euro-communism in the 1970s.

While many turned towards ‘democratic socialism’, and others clung to an unswerving commitment to the Communist Party and the defence of the Soviet Union, there were those who, while accepting the monstrosities of Stalinist and post-Stalinist Russia, refused to surrender the revolutionary heritage of the 1917 Revolution. Recognising the limitations of the post-war settlement, and refusing to forget the betrayals experienced the generation before at the hands of reformist socialism,[5] they sought to salvage the revolutionary insights of Lenin and the Bolsheviks from what they saw as the degeneration of the revolution brought about under Stalin. The obvious inspiration for those who held this position was Stalin’s great rival Leon Trotsky and his theory of the Soviet Union as a degenerated workers’ state.

Leon Trotsky

It is not that hard to understand why those who had become increasingly disillusioned with Stalin’s Russia, but who still wished to defend Lenin and the revolutionary heritage of 1917 should have turned to Leon Trotsky. Trotsky had played a leading role in the revolutionary events of both 1905 and 1917 in Russia. Despite Stalin’s attempts to literally paint him out of the picture, Trotsky had been a prominent member of the early Bolshevik Government, so much so that it can be convincingly argued that he was Lenin’s own preferred successor.

As such, in making his criticisms of Stalinist Russia, Trotsky could not be so easily dismissed as some bourgeois intellectual attempting to discredit socialism, nor could he be accused of being an utopian ultra-leftist or anarchist attempting to measure up the concrete limitations of the ‘actually existing socialism’ of the USSR against some abstract ideal of what socialism should be. On the contrary, as a leading member of the Bolshevik Government Trotsky had been responsible for making harsh and often ruthless decisions necessary to maintain the fragile and isolated revolutionary government. Trotsky had not shrunk from supporting the introduction of one-man management and Taylorism, nor had he shied away from crushing wayward revolutionaries as was clearly shown when he led the Red Army detachments to put down both Makhno’s peasant army during the civil war and the Kronstadt sailors in 1921.Indeed, Trotsky often went beyond those policies deemed necessary by Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders as was clearly exemplified by his call for the complete militarization of labour.[6]

Yet Trotsky was not merely a practical revolutionary capable of taking and defending difficult decisions. Trotsky had proved to be one of the few important strategic and theoretical thinkers amongst the Russian Bolsheviks who could rival the theoretical and strategic leadership of Lenin. We must now consider Trotsky’s ideas in detail and in their own terms, reserving more substantial criticisms until later.

Trotsky and the Orthodox Marxism of the Second International[7]

There is little doubt that Trotsky remained committed throughout his life to the orthodox view of historical materialism which had become established in the Second International. Like most Marxists of his time, Trotsky saw history primarily in terms of the development of the forces of production. While class struggle may have been the motor of history which drove it forward, the direction and purpose of history was above all the development of the productive powers of human labour towards its ultimate goal of a communist society in which humanity as a whole would be free from both want and scarcity.

As such, history was seen as a series of distinct stages, each of which was dominated by a particular mode of production. As the potential for each mode of production to advance the productive forces became exhausted its internal contradictions would become more acute and the exhausted mode of production would necessarily give way to a new more advanced mode of production which would allow the further development of the productive powers of human labour.

The capitalist mode of production had developed the forces of production far beyond anything that had been achieved before. Yet in doing so capitalism had begun to create the material and social conditions necessary for its own supersession by a socialist society. The emergence of modern large scale industry towards the end of the nineteenth century had led to an increasing polarization between a tiny class of capitalists at one pole and the vast majority of proletarians at the other.

At the same time modern large scale industry had begun to replace the numerous individual capitalists competing in each branch of industry by huge joint stock monopolies that dominated entire industries in a particular economy. With the emergence of huge joint stock monopolies and industrial cartels, it was argued by most Marxists that the classical form of competitive capitalism, which had been analysed by Marx in the mid-nineteenth century, had now given way to monopoly capitalism. Under competitive capitalism what was produced and how this produced wealth should be distributed had been decided through the ‘anarchy of market forces’, that is as the unforeseen outcome of the competitive battle between competing capitalists. With the development of monopoly capitalism, production and distribution was becoming more and more planned as monopolies and cartels fixed in advance the levels of production and pricing on an industry-wide basis.

Yet this was not all. As the economy as a whole became increasingly interdependent and complex the state, it was argued, could no longer play a minimal economic role as it had done during the competitive stage of capitalism. With the development of large scale industry the state increasingly had to intervene and direct the economy. Thus for orthodox Marxism, the development towards monopoly capitalism was at one and the same time a development towards state capitalism.

As economic planning by the monopolies and the state replaced the ‘anarchy of market’ in regulating the economy, the basic conditions for a socialist society were being put in place. At the same time the basic contradiction of capitalism between the increasingly social character of production and the private appropriation of wealth it produced was becoming increasingly acute. The periodic crises that had served both to disrupt yet renew the competitive capitalism of the early and mid-nineteenth century had now given way to prolonged periods of economic stagnation as the monopolists sought to restrict production in order to maintain their monopoly profits.

The basis of the capitalist mode of production in the private appropriation of wealth based on the rights of private property could now be seen to be becoming a fetter on the free development of productive forces. The period of the transition to socialism was fast approaching as capitalism entered its final stages of decline. With the growing polarization of society, which was creating a huge and organized proletariat, all that would be needed was for the working class to seize state power and to nationalize the major banks and monopolies so that production and distribution could be rationally planned in the interests of all of society rather than in the interests of the tiny minority of capitalists. Once the private ownership of the means of production had been swept away the development of the forces of production would be set free and the way would be open to creating a communist society in which freedom would triumph over necessity.

Of course, like many on the left and centre of the Second International, Trotsky rejected the more simplistic versions of this basic interpretation of historical materialism which envisaged the smooth evolution of capitalism into socialism. For Trotsky the transition to socialism would necessarily be a contradictory and often violent process in which the political could not be simply reduced to the economic.

For Trotsky, the contradictory development of declining capitalism could prompt the revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist class long before the material and social preconditions for a fully developed socialist society had come into being. This possibility of a workers’ state facing a prolonged period of transition to a fully formed socialist society was to be particularly important to the revolution in Trotsky’s native Russia.

Trotsky and the theory of permanent revolution[8]

While Trotsky defended the orthodox Marxist interpretation of the nature of historical development he differed radically on its specific application to Russia, and it was on this issue that Trotsky made his most important contribution to what was to become the new orthodoxy of Soviet Marxism.

The orthodox view of the Second International had been that the socialist revolution would necessarily break out in one of the more advanced capitalist countries where capitalism had already created the preconditions for the development of a socialist society. In the backward conditions of Russia, there could be no immediate prospects of making a socialist revolution. Russia remained a semi-feudal empire dominated by the all powerful Tsarist autocracy which had severely restricted the development of capitalism on Russian soil. However, in order to maintain Russia as a major military power, the Tsarist regime had been obliged to promote a limited degree of industrialization which had begun to gather pace by the turn of century. Yet even with this industrialization the Russian economy was still dominated by small scale peasant agriculture.

Under such conditions it appeared that the immediate task for Marxists was to hasten the bourgeois-democratic revolution which, by sweeping away the Tsarist regime, would open the way for the full development of capitalism in Russia, and in doing so prepare the way for a future socialist revolution. The question that came to divide Russian Marxists was the precise character the bourgeois-democratic revolution would take and as a consequence the role the working class would have to play within it.

For the Mensheviks the revolution would have to be carried out in alliance with the bourgeoisie. The tasks of the party of the working class would be to act as the most radical wing of the democratic revolution which would then press for a ‘minimal programme’ of political and social reforms which, while compatible with both private property and the limits of the democratic-bourgeois revolution, would provide a sound basis for the future struggle against the bourgeoisie and capitalism.

In contrast, Lenin and the Bolsheviks believed that the Russian bourgeoisie was far too weak and cowardly to carry out their own revolution. As a consequence, the bourgeois-democratic revolution would have to be made for them by the working class in alliance with the peasant masses. However, in making a revolutionary alliance with the peasantry the question of land reform would have to be placed at the top of the political agenda of the revolutionary government. Yet, as previous revolutions in Western Europe had shown, as soon as land had been expropriated from the landowners and redistributed amongst the peasantry most of the peasants would begin to lose interest in the revolution and become a conservative force. So, having played an essential part in carrying out the revolution, the peasantry would end up blocking its further development and confine it within the limits of a bourgeois-democratic revolution in which rights of private property would necessarily have to be preserved.

Against both these positions, which tended to see the historical development of Russia in isolation, Trotsky insisted that the historical development of Russia was part of the overall historical development of world capitalism. As a backward economy Russia had been able to import the most up to date methods of modern large scale industry ‘ready made’ without going through the long, drawn out process of their development which had occurred in the more advanced capitalist countries. As a result Russia possessed some of the most advanced industrial methods of production alongside some of the most backward forms of agricultural production in Europe. This combination of uneven levels of economic development meant that the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Russia would be very different from those that had previously occurred elsewhere in Europe.

Firstly, the direct implantation of modern industry into Russia under the auspices of the Tsarist regime had meant that much of Russian industry was either owned by the state or by foreign capital. As a consequence, Russia lacked a strong and independent indigenous bourgeoisie. At the same time, however, this direct implantation of modern large scale industry had brought into being an advanced proletariat whose potential economic power was far greater than its limited numbers might suggest. Finally, by leaping over the intermediary stages of industrial development, Russia lacked the vast numbers of intermediary social strata rooted in small scale production and which had played a decisive role in the democratic-bourgeois revolutions of Western Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

On the basis of this analysis Trotsky concluded as early as 1904 that the working class would have to carry out the democratic-bourgeois revolution in alliance with the peasant masses because of the very weakness of the indigenous Russian bourgeoisie. To this extent Trotsky’s conclusions concurred with those of Lenin and the Bolsheviks at that time. However, Trotsky went further. For Trotsky both the heterogeneity and lack of organization amongst the peasant masses meant that, despite their overwhelming numbers, the Russian peasantry could only play a supporting role within the revolution. This political weakness of the peasantry, together with the absence of those social strata based in small scale production, meant that the Russian proletariat would be compelled to play the leading role in both the revolution, and in the subsequent revolutionary government. So, whereas Lenin and the Bolsheviks envisaged that it would be a democratic workers-peasant government that would have to carry out the bourgeois revolution, Trotsky believed that the working class would have no option but to impose its domination on any such revolutionary government.

In such a leading position, the party of the working class could not simply play the role of the left wing of democracy and seek to press for the adoption of its ‘minimal programme’ of democratic and social reforms. It would be in power, and as such it would have little option but to implement the ‘minimal programme’ itself. However, Trotsky believed that if a revolutionary government led by the party of the working class attempted to implement a ‘minimal programme’ it would soon meet the resolute opposition of the propertied classes. In the face of such opposition the working class party would either have to abdicate power or else press head by abolishing private property in the means of production and in doing so begin at once the proletarian-socialist revolution.

For Trotsky it would be both absurd and irresponsible for the party of the working class to simply abdicate power in such a crucial situation. In such a position, the party of the working class would have to take the opportunity of expropriating the weak bourgeoisie and allow the bourgeois-democratic revolution to pass, uninterrupted, into a proletarian-socialist revolution.

Trotsky accepted that the peasantry would inevitably become a conservative force once agrarian reform had been completed. However, he argued that a substantial part of the peasantry would continue to back the revolutionary government for a while, not because of any advanced ‘revolutionary consciousness’ but due to their very ‘backwardness’;[9] this, together with the proletariats’ superior organization, would give the revolutionary government time. Ultimately, however, the revolutionary government’s only hope would be that the Russian revolution would trigger revolution throughout the rest of Europe and the world.

Trotsky and the perils of transition

While Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution may have appeared adventurist, if not a little utopian, to most Russian Marxists when it was first set out in Results and Prospects in 1906, its conclusions were to prove crucial eleven years later in the formation of the new Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy which came to be established with the Russian Revolutions of 1917.

The revolution of February 1917 took all political parties and factions by surprise. Within a few days the centuries old Tsarist regime had been swept away and a situation of dual power established. On the one side stood the Provisional Government dominated by the various liberal bourgeois parties, on the other side stood the growing numbers of workers and peasant soviets. For the Mensheviks the position was clear: the organizations of the working class had to give critical support to the bourgeois Provisional Government while it carried out its democratic programme. In contrast, faced with a democratic-bourgeois Government which they had denied was possible, the Bolsheviks were thrown into confusion. A confusion that came to a virtual split with the return of Lenin from exile at the beginning of April.

In his April Theses Lenin proposed a radical shift in policy, which, despite various differences in detail and emphasis, brought him close to the positions that had been put forward by Trotsky with his theory of permanent revolution. Lenin argued that the Bourgeois Government would eventually prove too weak to carry out its democratic programme. As a consequence the Bolsheviks had to persuade the soviets to overthrow the Provisional Government and establish a workers’ and peasants’ government which would not only have the task of introducing democratic reform, but which would eventually have to make a start on the road to socialism.

With this radical shift in position initiated by the April Theses, and Trotsky’s subsequent acceptance of Lenin’s conception of the revolutionary party, the way was opened for Trotsky to join the Bolsheviks; and, together with Lenin, Trotsky was to play a major role not only in the October revolution and the subsequent Bolshevik Government but also in the theoretical elaboration of what was to become known as Marxist-Leninism.

While both Lenin and Trotsky argued that it was necessary to overthrow the Provisional Government and establish a workers’ government through a socialist-proletarian revolution, neither Lenin nor Trotsky saw socialism as an immediate prospect in a backward country such as Russia. The proletarian revolution that established the worker-peasant dictatorship was seen as only the first step in the long transition to a fully developed socialist society. As Trotsky was later to argue,[10] even in an advanced capitalist country like the USA a proletarian revolution would not be able to bring about a socialist society all at once. A period of transition would be required that would allow the further development of the forces of production necessary to provide the material basis for a self-sustaining socialist society. In an advanced capitalist country like the USA such a period of transition could take several years; in a country as backward as Russia it would take decades, and ultimately it would only be possible with the material support of a socialist Europe.

For both Lenin and Trotsky then, Russia faced a prolonged period of transition, a transition that was fraught with dangers. On the one side stood the ever present danger of the restoration of capitalism either through a counter-revolution backed by foreign military intervention or through the re-emergence of bourgeois relations within the economy; on the other side stood the danger of the increasing bureaucratization of the workers’ state. As we shall see, Trotsky saw the key to warding off all these great perils of Russia’s transition to socialism in the overriding imperative of both increasing production and developing the forces of production, while waiting for the world revolution.

In the first couple of years following the revolution many on the left wing of the Bolsheviks, enthused by the revolutionary events of 1917 and no doubt inspired by Lenin’s State and Revolution, which restated the Marxist vision of a socialist society, saw Russia as being on the verge of communism. For them the policy that had become known as War Communism, under which money had been effectively abolished through hyper-inflation and the market replaced by direct requisitioning in accordance with the immediate needs of the war effort, was an immediate prelude to the communism that would come with the end of the civil war and the spread of the revolution to the rest of Europe.[11]

Both Lenin and Trotsky rejected such views from the left of the Party. For them the policy of War Communism was little more than a set of emergency measures forced on the revolutionary government which were necessary to win the civil war and defeat armed foreign intervention. For both Lenin and Trotsky there was no immediate prospect of socialism let alone communism[12] in Russia, and in his polemics with the left at this time Lenin argued that, given the backward conditions throughout much of Russia, state capitalism would be a welcome advance. As he states:

Reality tells us that state capitalism would be a step forward. If in a small space of time we could achieve state capitalism, that would be a victory. (Lenin’s Collected Works Vol. 27, p. 293)

Trotsky went even further, dismissing the growing complaints from the left concerning the bureaucratization of the state and party apparatus, he argued for the militarization of labour in order to maximize production both for the war effort and for the post-war reconstruction. As even Trotsky’s admirers have to admit, at this time Trotsky was clearly on the ‘authoritarian wing’ of the party, and as such distinctly to the right of Lenin.[13]

It is not surprising, given that he had seen War Communism as merely a collection of emergency measures rather than the first steps to communism, that once the civil war began to draw to a close and the threat of foreign intervention began to recede, Trotsky was one of the first to advocate the abandonment of War Communism and the restoration of money and market relations. These proposals for a retreat to the market were taken up in the New Economic Policy (NEP) that came to be adopted in 1921.

The NEP and the Left Opposition

By 1921 the Bolshevik Government faced a severe political and economic crisis. The policy of forced requisitioning had led to a mass refusal by the peasantry to sow sufficient grain to feed the cities. Faced with famine, thousands of workers simply returned to their relatives in the countryside. At the same time industry had been run into the ground after years of war and revolution. In this dire economic situation, the ending of the civil war had given rise to mounting political unrest amongst the working class, both within and outside the Party, which threatened the very basis of the Bolshevik Government. Faced with political and economic collapse the Bolshevik leadership came to the conclusion that there was no other option but make a major retreat to the market. The Bolshevik Government therefore abandoned War Communism and adopted the New Economic Policy (NEP) which had been previously mooted by Trotsky.

Under the NEP, state industry was broken up in to large trusts which were to be run independently on strict commercial lines. At the same time, a new deal was to be struck with the peasantry. Forced requisitioning was to be replaced with a fixed agricultural tax, with restrictions lifted on the hiring of labour and leasing of land to encourage the rich and middle-income peasants to produce for the market.[14] With the retreat from planning, the economic role of the state was to be mainly restricted to re-establishing a stable currency through orthodox financial polices and a balanced state budget.

For Trotsky, the NEP, like War Communism before it, was a policy necessary to preserve the ‘workers’ state’ until it could be rescued by revolution in Western Europe. As we have seen, Trotsky had, like Lenin, foreseen an alliance with the peasantry as central to sustaining a revolutionary government, and the NEP was primarily a means of re-establishing the workers-peasants alliance which had been seriously undermined by the excesses of War Communism. However, as we have also seen, Trotsky had far less confidence in the revolutionary potential of the peasantry than Lenin or other Bolshevik leaders. For Trotsky, the NEP, by encouraging the peasants to produce for the market, held the danger of creating a new class of capitalist farmers who would then provide the social basis for a bourgeois counter-revolution and the restoration of private property. As a consequence, from an early stage, Trotsky began to advocate the development of comprehensive state planning and a commitment to industrialization within the broad framework of the NEP.

Although Trotsky’s emphasis on the importance of planning and industrialization left him isolated within the Politburo, it placed him alongside Preobrazhensky at the head of a significant minority within the wider leadership of the Party and state apparatus which supported such a shift in direction of the NEP, and which became known as the Left Opposition. As a leading spokesman for the Left Opposition, and at the same time one of the foremost economists within the Bolshevik Party, Preobrazhensky came to develop the Theory of Primitive Socialist Accumulation which served to underpin the arguments of the Left Opposition, including Trotsky himself.

Preobrazhensky’s theory of primitive accumulation

As we have already noted, for the orthodox Marxism of the Second International whereas capitalism was characterized by the operation of market forces — or in more precise Marxist terms the ‘law of value’ — socialism would be regulated by planning. From this Preobrazhensky argued that the transition from capitalism to socialism had to be understood in terms of the transition from the regulation of the economy through the operation of the law of value to the regulation of the economy through the operation of the ‘law of planning’. During the period of transition both the law of value and the law of planning would necessarily co-exist, each conditioning and competing with the other.

Under the New Economic Policy, most industrial production had remained under state ownership and formed the state sector. However, as we have seen, this state sector had been broken up into distinct trusts and enterprises which were given limited freedom to trade with one another and as such were run on a profit-and-loss basis. To this extent it could be seen that the law of value still persisted within the state sector. Yet for Preobrazhensky, the power of the state to direct investment and override profit-and-loss criteria meant that the law of planning predominated in the state sector. In contrast, agriculture was dominated by small-scale peasant producers. As such, although the state was able to regulate the procurement prices for agricultural produce, agriculture was, for Preobrazhensky, dominated by the law of value.

From this Preobrazhensky argued that the struggle between the law of value and the law of planning was at the same time the struggle between the private sector of small-scale agricultural production and the state sector of large-scale industrial production. Yet although large-scale industrial production was both economically and socially more advanced than that of peasant agriculture the sheer size of the peasant sector of the Russian economy meant that there was no guarantee that the law of planning would prevail. Indeed, for Preobrazhensky, under the policy of optimum and balanced growth advocated by Bukharin and the right of the Party and sanctioned by the Party leadership, there was a real danger that the state sector could be subordinated to a faster growing agricultural sector and with this the law of value would prevail.

To avert the restoration of capitalism Preobrazhensky argued that the workers’ state had to tilt the economic balance in favour of accumulation within the state sector. By rapid industrialization the state sector could be expanded which would both increase the numbers of the proletariat and enhance the ascendancy of the law of planning. Once a comprehensive industrial base had been established, agriculture could be mechanized and through a process of collectivization agriculture could be eventually brought within the state sector and regulated by the law of planning.

Yet rapid industrialization required huge levels of investment which offered little prospects of returns for several years. For Preobrazhensky there appeared little hope of financing such levels of investment within the state sector itself without squeezing the working class — an option that would undermine the very social base of a workers’ government. The only option was to finance industrial investment out of the economic surplus produced in the agricultural sector by the use of tax and pricing policies.

This policy of siphoning off the economic surplus produced in the agricultural sector was to form the basis for a period of Primitive Socialist Accumulation. Preobrazhensky argued that just as capitalism had to undergo a period primitive capitalist accumulation, in which it plundered pre-capitalist modes of production, before it could establish itself on a self-sustaining basis, so, before a socialist society could establish itself on a self-sustaining basis, it too would have to go through an analogous period of primitive socialist accumulation, at least in a backward country such as Russia.

The rise of Stalin

With the decline in Lenin’s health and his eventual death in 1924, the question of planning and industrialization became a central issue in the power struggle for the succession to the leadership of the Party. Yet while he was widely recognized within the Party as Lenin’s natural successor, and as such had been given Lenin’s own blessing, Trotsky was reluctant to challenge the emerging troika of Stalin, Kamenev and Zinoviev, who, in representing the conservative forces within the state and Party bureaucracy, sought to maintain the NEP as it was. For Trotsky, the overriding danger was the threat of a bourgeois counter-revolution. As a result he was unwilling to split the Party or else undermine the ‘centrist’ troika and allow the right of the Party to come to power, enabling the restoration of capitalism through the back door.

Furthermore, despite Stalin’s ability repeatedly to out-manoeuvre both Trotsky and the Left Opposition through his control of the Party bureaucracy, Trotsky could take comfort from the fact that after the resolution of the first ‘scissors crisis’[15] in 1923 the leadership of the Party progressively adopted a policy of planning and industrialization, although without fully admitting it.

By 1925, having silenced Trotsky and much of the Left Opposition, Stalin had consolidated sufficient power to oust both Kamenev and Zinoviev[16] and force them to join Trotsky in opposition. Having secured the leadership of the Party, Stalin now openly declared a policy of rapid industrialization under the banner of ‘building socialism in one country’ with particular emphasis on building up heavy industry. Yet at first Stalin refused to finance such an industrialization strategy by squeezing the peasants. Since industrialization had to be financed from within the industrial state sector itself, investment in heavy industry could only come at the expense of investment in light industry which produced the tools and consumer goods demanded by the peasantry. As a result a ‘goods famine’ emerged as light industry lagged behind the growth of peasant incomes and the growth of heavy industry. Unable to buy goods from the cities the peasants simply hoarded grain so that, despite record harvests in 1927 and 1928, the supply of food sold to the cities fell dramatically.

This crisis of the New Economic Policy brought with it a political crisis within the leadership of the Party and the State. All opposition within the Party had to be crushed. Trotsky and Zinoviev were expelled from the Party, with Trotsky eventually being forced into exile, leaving Stalin to assume supreme power in both the Party and the state. To consolidate and sustain his power Stalin was obliged to launch a reign of terror within the Communist Party. This terror culminated in a series of purges and show trials in the 1930s which led to the execution of many of the leading Bolsheviks of the revolution.

Perhaps rather ironically, while Stalin had defended the New Economic Policy to the last, he now set out to resolve the economic crisis by adopting the erstwhile policies of the Left Opposition albeit pushing them to an unenvisaged extreme.[17] Under the five year plans, the first of which began in 1928, all economic considerations were subordinated to the overriding objective of maximizing growth and industrialization. Increasing physical output as fast as possible was now to be the number one concern, with the question of profit and loss of individual enterprises reduced to a secondary consideration at best. At the same time agriculture was to be transformed through a policy of forced collectivization. Millions of peasants were herded into collectives and state farms which, under state direction, could apply modern mechanized farming methods.

It was in the face of this about turn in economic policy, and the political terror that accompanied it, that Trotsky was obliged to develop his critique of Stalinist Russia and with this the fate of the Russian Revolution. It was now no longer sufficient for Trotsky to simply criticize the economic policy of the leadership as he had done during the time of the Left Opposition. Instead Trotsky had to broaden his criticisms to explain how the very course of the revolution had ended up in the bureaucratic nightmare that was Stalinist Russia. Trotsky’s new critique was to find its fullest expression in his seminal work The Revolution Betrayed which was published in 1936.

Trotsky and the Leninist conception of party, class and the state

As we shall see, in The Revolution Betrayed, Trotsky concludes that, with the failure of the revolution elsewhere in the world, the workers’ state established by the Russian Revolution had degenerated through the bureaucratization of both the Party and the state. To understand how Trotsky was able to come to this conclusion while remaining within Marxist and Leninist orthodoxy, we must first consider how Trotsky appropriated and developed the Leninist conception of the state, party and class.

From almost the very beginning of the Soviet Union there had been those both inside and outside the Party who had warned against the increasing bureaucratization of the revolution. In the early years, Trotsky had little sympathy for such complaints concerning bureaucratization and authoritarianism in the Party and the state. At this time, the immediate imperative of crushing the counter-revolutionary forces, and the long-term aim of building the material basis for socialism, both demanded a strong state and a resolute Party which were seen as necessary to maximize production and develop the productive forces. For Trotsky at this time, the criticisms of bureaucratization and authoritarianism, whether advanced by those on the right or the left, could only serve to undermine the vital role of the Party and the state in the transition to socialism.

However, having been forced into opposition and eventual exile Trotsky was forced to develop his own critique of the bureaucratization of the revolution, but in doing so he was anxious to remain within the basic Leninist conceptions of the state, party and class which he had resolutely defended against earlier critics.

Following Engels, theorists within the Second International had placed much store in the notion that what distinguished Marxism from all former socialist theories was that it was neither an utopian socialism nor an ethical socialism but a scientific socialism. As a consequence, Marxism tended to be viewed as a body of positive scientific knowledge that existed apart from the immediate experiences and practice of the working class. Indeed, Marx’s own theory of commodity fetishism seemed to suggest that the social relations of capitalist society inevitably appeared in forms that served to obscure their own true exploitative nature.[18] So, while the vast majority of the working class may feel instinctively that they were alienated and exploited, capitalism would still appear to them as being based on freedom and equality. Thus, rather than seeing wage-labour in general as being exploitative, they would see themselves being cheated by a particular wage deal. So, rather than calling for the abolition of wage-labour, left to themselves the working class would call for a ‘fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work’.

Trapped within the routines of their everyday life, the majority of the working class would not be able by themselves to go beyond such a sectional and trade union perspective. Hence one of the central tasks of a workers’ party was to educate the working class in the science of Marxism. It would only be through a thorough knowledge of Marxism that the working class would be able to reach class consciousness and as such be in a position to understand its historic role in overthrowing capitalism and bringing about a socialist society.

In adapting this orthodox view of the Party to conditions prevailing in Tsarist Russia Lenin had pushed it to a particular logical extreme. It was in What is to be Done? that Lenin had first set out his conception of a revolutionary party based on democratic centralism. In this work Lenin had advocated a party made up of dedicated and disciplined professional revolutionaries in which, while the overall policy and direction of the party would be made through discussion and democratic decision, in the everyday running of the party the lower organs of the party would be completely subordinated to those of the centre. At the time, Trotsky had strongly criticized What is to be Done?, arguing that Lenin’s conception of the revolutionary party implied the substitution of the party for the class.

Indeed, Trotsky’s rejection of Lenin’s conception of the party has often been seen as the main dividing line between Lenin and Trotsky right up until their eventual reconciliation in the summer of 1917. Thus, it has been argued that, while the young Trotsky had sided with Lenin and the Bolsheviks against the Mensheviks over the crucial issue of the need for an alliance with the peasantry, he had been unable to accept Lenin’s authoritarian position on the question of organization. It was only in the revolutionary situation of 1917 that Trotsky had come over to Lenin’s viewpoint concerning the organization of the Party. However, there is no doubt that Trotsky accepted the basic premise of What is to be Done?, which was rooted in Marxist orthodoxy, that class consciousness had to be introduced from outside the working class by intellectuals educated in the ‘science of Marxism’. There is also little doubt that from an early date Trotsky accepted the need for a centralized party. The differences between Lenin and Trotsky over the question of organization were for the most part a difference of emphasis.[19] What seems to have really kept Lenin and Trotsky apart for so long was not so much the question of organization but Trotsky’s ‘conciliationism’. Whereas Lenin always argued for a sharp differentiation between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks to ensure political and theoretical clarity, Trotsky had always sought to re-unite the two wings of Russian social democracy.

To some extent Lenin’s formulation of democratic centralism in What is to be Done? was determined by the repressive conditions then prevailing in Tsarist Russia; but it was also premised on the perceived cultural backwardness of the Russian working class which, it was thought, would necessarily persist even after the revolution. Unlike Germany, the vast majority of the Russian working class were semi-literate and uneducated. Indeed, many, if not a majority of the Russian working class were fresh out of the countryside and, for socialist intellectuals like Lenin and Trotsky, retained an uncouth parochial peasant mentality. As such there seemed little hope of educating the vast majority of the working class beyond a basic trade union consciousness.

However, there were a minority within the working class, particularly among its more established and skilled strata, who could, through their own efforts and under the tutelage of the party, attain a clear class consciousness. It was these more advanced workers, which, organized through the party, would form the revolutionary vanguard of the proletariat that would be the spearhead of the revolution. Of course this was not to say that rest of the working class, or even the peasantry, could not be revolutionary. On the contrary, for Lenin and the Bolsheviks, revolution was only possible through the mass involvement of the peasants and the working class. But the instinctive revolutionary will of the masses had to be given leadership and direction by the party. Only through the leadership of the proletarian vanguard organized in a revolutionary party would it be possible to mediate and reconcile the immediate and often competing individual and sectional interests of workers and peasants with the overall and long-term interests of the working class in building socialism.

For Lenin, the first task in the transition to socialism had to be the seizure of state power. During his polemics against those on the right of the Bolshevik Party who had, during the summer of 1917, feared that the overthrow of the bourgeois Provisional Government and the seizure of state power might prove premature, Lenin had returned to Engels’ conception of the state in the stage of socialism.

Against both Lassalle’s conception of state socialism and the anarchists’ call for the immediate abolition of the state, Engels had argued that, while it would be necessary to retain the state as means of maintaining the dictatorship of the working class until the danger of counter-revolution had been finally overcome, a socialist state would be radically different from that which had existed before. Under capitalism the state had to stand above society in order both to mediate between competing capitalist interests and to impose the rule of the bourgeois minority over the majority of the population. As a result, the various organs of the state, such as the army, the police and the administrative apparatus had to be separated from the population at large and run by a distinct class of specialists. Under socialism the state would already be in the process of withering away with the breaking down of its separation from society. Thus police and army would be replaced by a workers’ militia, while the state administration would be carried out increasingly by the population as a whole.

Rallying the left wing of the Bolshevik Party around this vision of socialism, Lenin had argued that with sufficient revolutionary will on the part of the working masses and with the correct leadership of the party it would be possible to smash the state and begin immediately the construction of Engels’ ‘semi-state’ without too much difficulty.[20] Already the basis for the workers’ and peasants’ state could be seen in the mass organizations of the working class — the factory committees, the soviets and the trade unions, and by the late summer of 1917 most of these had fallen under the leadership of the Bolsheviks.[21] Yet this conception of the state which inspired the October revolution did not last long into the new year.

Confronted by the realities of consolidating the power of the new workers’ and peasants’ government in the backward economic and cultural conditions then prevailing in Russia, it was not long before Lenin was obliged to reconsider his own over-optimistic assessments for the transition to socialism that he had adopted just prior to the October revolution. As a result, within weeks of coming to power it became clear to Lenin that the fledging Soviet State could not afford the time or resources necessary to educate the mass of workers and peasants to the point where they could be drawn into direct participation in the administration of the state. Nor could the economy afford a prolonged period of disruption that would follow the trials and errors of any experiment in workers’ self-management. Consequently, Lenin soon concluded that there could be no question of moving immediately towards Engels’ conception of a ‘semi-state’, which after all had been envisaged in the context of a socialist revolution being made in an advanced capitalist country. On the contrary, the overriding imperative of developing the forces of production, which alone could provide the material and cultural conditions necessary for a socialist society, demanded not a weakening, but a strengthening of the state — albeit under the strict leadership of the vanguard of the proletariat organized within the party.

So now, for Lenin, administrative and economic efficiency demanded the concentration of day to day decision making into the hands of specialists and the adoption of the most advanced methods of ‘scientific management’.[22] The introduction of such measures as one-man management and the adoption of methods of scientific management not only undermined workers’ power and initiative over the immediate process of production, but also went hand-in-hand with the employment of thousands of former capitalist managers and former Tsarist administrators.

Yet, while such measures served to re-impose bourgeois relations of production, Lenin argued that such capitalist economic relations could be counter-balanced by the political control exercised over the state-industrial apparatus by the mass organizations of the working class under the leadership of the Party. Indeed, as we have already noted, against the objections from the left that his policies amounted to the introduction not of socialism but of state capitalism, Lenin, returning to the orthodox formulation, retorted that the basis of socialism was nothing more than ‘state capitalism under workers’ control’, and that, given the woeful backwardness of the Russian economy, any development of state capitalism could only be a welcome advance.

As the economic situation deteriorated with the onset of the civil war and the intervention of the infamous ‘fourteen imperialist armies’,[23] the contradictions between the immediate interests of the workers and peasants and those of the socialist revolution could only grow. The need to maintain the political power of the Party led at first to the exclusion of all other worker and peasant parties from the workers’ and peasants’ government and then to the extension of the Red Terror, which had originally been aimed at counter-revolutionary bourgeois parties, to all those who opposed the Bolsheviks. At the same time power was gradually shifted from the mass organizations of the working class and concentrated within the central organs of the Party.[24] As a result it was the Party which had to increasingly serve as the check on the state and the guarantee of its proletarian character.

The degeneration of the revolution

There is no doubt that Trotsky shared such Leninist conceptions concerning the state, party and class, and with them the view that the transition to socialism required both the strengthening of the state and the re-imposition of capitalist relations of production. Indeed, this perspective can be clearly seen in the way he carried out the task of constructing the Red Army.[25] What is more, Trotsky did not balk at the implications of these Leninist conceptions and the policies that followed from them. Indeed, Trotsky fully supported the increasing suppression of opposition both inside and outside the Party which culminated with his backing for the suspension of Party factions at the Tenth Party Congress in 1921 and his personal role in crushing the Kronstadt rebellion in February 1921.

It can be argued that Trotsky was fully implicated in the Leninist conceptions and policies, and that such conceptions and policies provided both the basis and precedent for Stalinism and the show trials of the 1930s. However, for Trotsky and his followers there was a qualitative difference between the consolidation of power and repression of opposition that were adopted as temporary expedients made necessary due to the civil war and the threat of counter-revolution, and the permanent and institutional measures that were later adopted by Stalin. For Trotsky, this qualitative difference was brought about by the process of bureaucratic degeneration that arose with the failure of world revolution to save the Soviet Revolution from isolation.

In his final years Lenin had become increasingly concerned with the bureaucratization of both the state and Party apparatus. For Lenin, the necessity of employing non-proletarian bourgeois specialists and administrators, who would inevitably tend to work against the revolution whether consciously or unconsciously, meant that there would be a separation of the state apparatus from the working class and with this the emergence of bureaucratic tendencies. However, as a counter to these bureaucratic tendencies stood the Party. The Party, being rooted in the most advanced sections of the working class, acted as a bridge between the state and the working class, and, through the imposition of the ‘Party Line’, ensured the state remained essentially a ‘workers’ and peasants’ state’.

Yet the losses of the civil war left the Party lacking some of its finest working class militants, and those who remained had been drafted into the apparatus of the Party and state as full time officials. At the same time Lenin feared that more and more non-proletarian careerist elements were joining the Party. As a result, shortly before his death Lenin could complain that only 10 per cent of the Party membership were still at the factory bench. Losing its footing in the working class Lenin could only conclude that the Party itself was becoming bureaucratized.

In developing his own critique of Stalin, Trotsky took up these arguments which had been first put forward by Lenin. Trotsky further emphasized that, with the exhaustion of revolutionary enthusiasm, by the 1920s even the most advanced proletarian elements within the state and Party apparatus had begun to succumb to the pressures of bureaucratization. This process was greatly accelerated by the severe material shortages which encouraged state and Party officials, of whatever class origin, to place their own collective and individual interests as part of the bureaucracy above those of working masses.

For Trotsky, the rise to power of the troika of Stalin, Kamenev and Zinoviev following Lenin’s death marked the point where this process of bureaucratization of the state and Party had reached and ensnared the very leadership of the Party itself.[26] Drawing a parallel with the course of the French Revolution, Trotsky argued that this point represented the transition to the Russian Thermidor — a period of conservative reaction arising from the revolution itself. As such, for Trotsky, Russia remained a workers’ state, but one whose proletarian-socialist policies had now become distorted by the privileged and increasingly conservative strata of the proletariat that formed the bureaucracy, and through which state policy was both formulated and implemented.

For Trotsky, these conservative-bureaucratic distortions of state policy were clearly evident in both the internal and external affairs. Conservative-bureaucratic distortions were exemplified in foreign policy by the abandonment of proletarian internationalism, which had sought to spread the revolution beyond the borders of the former Russian empire, in favour of the policy of ‘building socialism in one country’. For the bureaucracy the disavowal of proletarian internationalism opened the way for the normalization of diplomatic relations with the capitalist powers throughout the rest of the world. For Trotsky, the abandonment of proletarian internationalism diminished the prospects of world revolution which was ultimately the only hope for the Russian Revolution if it was to avoid isolation in a capitalist world and further degeneration culminating in the eventual restoration of capitalism in Russia. Domestically, the policy of building socialism in one country had its counterpart in the persistence of the cautious economic policies of balanced and optimal growth represented by the continuation of the NEP, which for Trotsky, as we have already seen, threatened the rise of a new bourgeoisie amongst the rich peasantry and with this the danger of capitalist restoration.