Anonymous

I am no hero, and neither are you

thoughts on how our histories of abuse inflect our anarchist practice

the hand you hold is the hand that holds you down

on vigilance: toward another impossibility

These contributions were made in response to the prompt “How have our histories of abuse inflected our anarchist practice?”

They may be triggering.

for starters

Most anarchists share an understanding of security culture practices that discourages spreading information about peoples’ private political involvement. It is also important to avoid handing over emotional information without consideration of the potentially damaging ramifications. We need to build a practice of emotional security culture: mindfully protecting the emotionally charged parts of our friends’ lives.

In our scene, snitches and cops have been given easy access to personal information through the seemingly benign stories told about people’s private lives. This information is often used to create divisions between their targets. It is almost always an element of snitching, and sometimes is the driving force. This is one reason we should be keeping our friends safe when sharing parts of their emotional lives in the same way we protect parts of their political activity: they are really not separate at all.

That’s the big scary example. What happens more often is the casual spreading of other people’s emotional lives amongst friends, sometimes in the form of divisive gossip. Although the definition of gossip is debatable, what is clear is the harm that can come from people sharing emotionally sensitive information about other people’s lives without knowing if it is OK to do so. This isn’t to say we should never talk about other people’s stories; rather, we should do so with discretion, and get permission when possible. These boundaries are consistent with the principles of security culture in general.

On the other hand, we don’t feel an obligation to protect those who’ve harmed us. We must feel free to share our own stories of emotional vulnerabilities, and to pass on those of others when they consent. Doing so safely may take some extra consideration, but this additional effort is totally worth it.

When dealing with emotionally sensitive information, be sensitive with it.

the hand you hold is the hand that holds you down

Everyone I know is so fucked. We are all damaged broken ugly things, with huge, gaping faults that make us always near the brink of condemnation. At times, I think our greatest redeeming quality is that we know this, and hate ourselves more than anyone, and want to kill the parts of ourselves that have come to resemble those who made us this way. In this situation, among the ones who cannot leave anarchy because we have no other options, despair has come to constitute the real basis of our affinity. False positivities feel insulting, hope seems treacherous—but, also, sometimes necessary. How to fight them without being just like them, how to survive them without being just like them, how to love each other with all our oozing infected wounds?

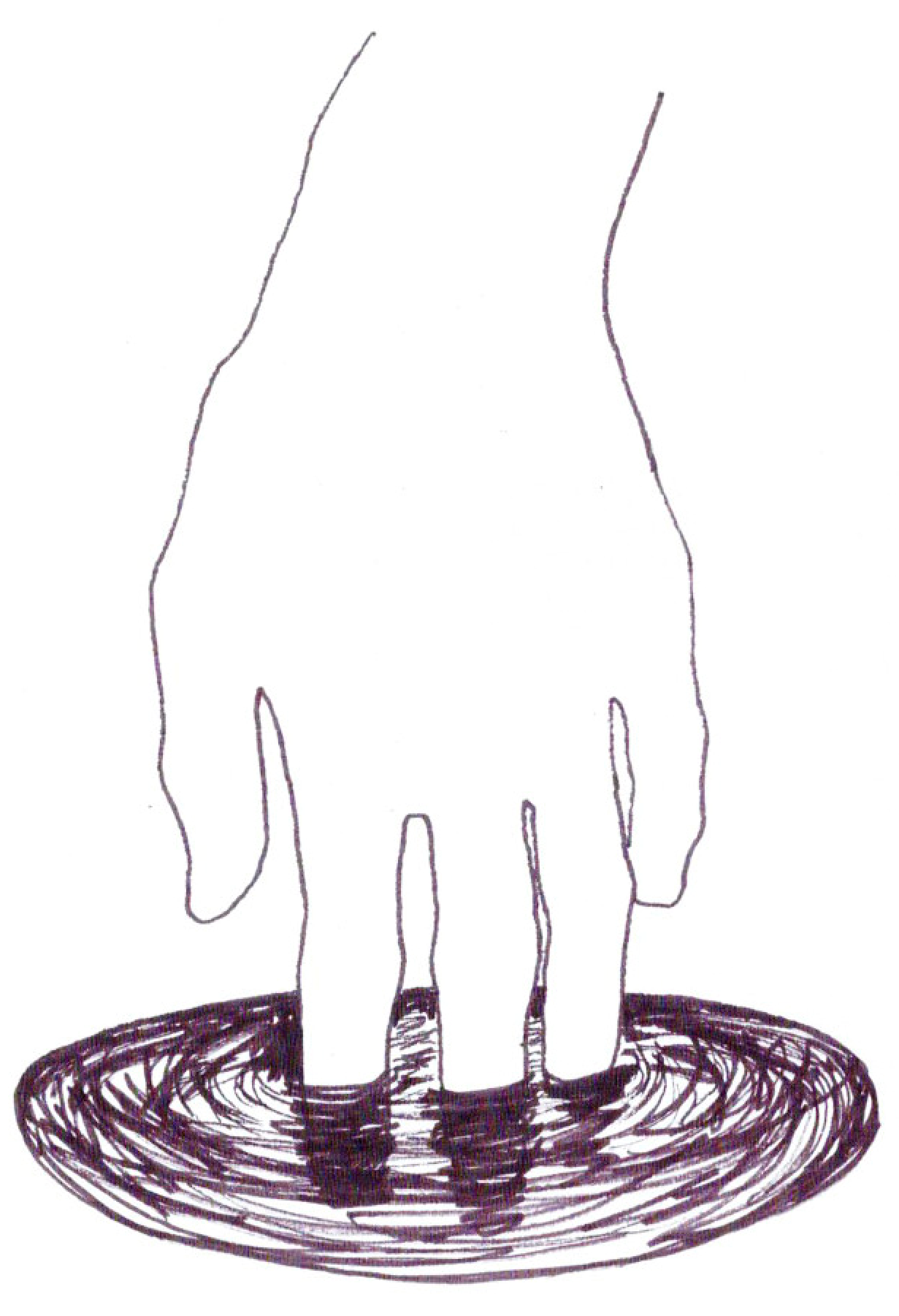

When elephants are born into captivity, they sometimes are chained to a stake when still small. The young elephant learns its limits, the circle within it may act; it can see the rest of the world, perhaps imagine its ability to act outside the circle, but it is not permitted to. Perhaps it rages against this constraint, but the fact remains that, when it is old enough, the stake and chain can be removed. The elephant will continue to walk its small circle, having been taught that no greater freedom exists. This is called domestication.

But, sometimes, the elephant revolts and kills its trainer. Sometimes herds of wild elephants rampage through a town, destroying infrastructure and people alike. Let’s not kid ourselves—these elephants pay for their rebellion, are put down or further confined. But in that moment of freedom that comes from biting the hand that feeds, there is an opening, a hope, an anarchy.

There are many qualities of anarchist spirit I have come to appreciate: bravery, humility, the tendency to listen to others and take them seriously, a deep hatred of the world and disdain for its offerings, an empathy with the struggles of others that translates directly into material solidarity, and a complicated relationship with death—a desire for it that overtakes us completely sometimes, a guiding vision of its necessity for those who control us, but a total regret and sadness for its power over us at present. (Sometimes, the knowledge feels liberating: in the Algerian insurrection of spring 2001, “the young rioters fought police and gendarmerie forces during several weeks shouting: “You cannot kill us, we are already dead!””[1])

One way to sum these qualities up is as a great generosity of spirit. We are not afraid to give of ourselves. We recognize, in fact, that there is little difference between ourselves and our comrades, with whom we have a fluid bond; we cannot help but share everything. We can extend further, to find some solidarity with those forms of life estranged from ours… although the relationship is attenuated and made difficult for our differences at times. And, truly, we all inhabit different forms of life at once— the queer anarchist is unhappy amidst their straight comrades, but even more so among queer radicals.

All of this generosity, though, and its attempts at generalizing itself, are constrained by the circle we have been taught to walk.We may be taking the Ring to Mordor to destroy it, but, at times, we are not Frodo, or even Sam. Sometimes we are Gollum, desiring and hating what destroys us, bent and broken by it already, not always able to resist its temptation. The poor abused Smeagol in us is not always on top.

Other ways of saying this: we are Frankenstein’s monster, misshapen by our experiences and trauma, but still with a human heart that can feel and bleed. Nietzsche would say that we have a slave morality, that we try to bring down those around us, that we hate our oppressors so much that we try to become their opposites—the perfect victims. We are full of ressen- timent, our natural anger against our conditions turned inwards for our own destruction. We are Reich’s little man, reactionaries fighting against our own liberation, covered in character armor. Our defense mechanisms have outlived our need for them, and come to define and control us.

We are taught our own constraints by subtle means, often “positive”—to buy from the co-op if we can afford it, and to feel guilty if we cannot; to patiently stand in line at that co-op; to not leave the line in disgust and walk out with our arms full of stolen groceries. We are also taught, if this omnipresent manipulation is not enough to confine us, by more blunt, sovereign power—the violent arrest, prison and the abuse we might experience there. But, as for the elephant, the most effective teachings we endure happen early—the advice of our parents, the tone of our interactions, whether or not they hit us, and so on. These things are not small—studies show that the single most important fact defining whether or not someone will do well in life is whether or not your mother loves you. Even if for only a year, when you are too young to remember her—it matters.

The killer in me is the killer in you

This whole time I have said we, because I suspect I am not alone in this, but now I will say I, and speak from my own experience. My mother did not love me. She hated me, in fact, and spent my childhood reenacting a less horrifying version of the abuse she experienced in her own childhood, although she would not describe it so; she often told me that I had it easy, and described things terrible enough to make me agree. My dad loved me, though, and I chalk it up to his care that I am sometimes able today to love and care, to feel a tension towards freedom within myself. Now that I am grown, and have a child of my own, I am determined to not become my mother, to never hurt her. I want to believe that experience is not destiny, that the story does not have to repeat just so.

As anarchists, we seek to defy the limitations of society in blatant, powerful ways—attacking abusers, institutions, physical manifestations of what we hate. We affirm our own sovereignity, or try to destroy what destroys us; so many slogans. This is good, and more of it is needed, but... as I get older, and as I come up against my internal limitations more and more consistently, I am reluctantly coming to believe that we must also resist and undo the subtle inflections of our terrible experiences. I am afraid that, otherwise, my practice will be forever constrained and uncreative, that I am doomed to reproduce the state in every relationship. For years I have mouthed “it’s not what, but how” without fully believing it—if there were a thousand more attacks a year, it might not be enough, but it would certainly be encouraging! But I look to history, and see how it has been bad before, and feel unwillingly convinced of the need for personal and social destruction on an intangible level.

If you hit me and I hit you, we still ain’t even

The most common definition of the cycle of violence is something like: you hit me, I hit you, you hit me back, and it never ends. This is a disempowering and flattening definition: one thinks of the liberal narrative of Israel and Palestine. The definition used by the antidomestic violence “community”, however, is a bit more useful.

It describes a process that happens largely within the abuser: a honeymoon period in which everything is good, better, more intense than other relationships; then a building tension; next a violent outburst; then apologies, promises of never again and a return to the honeymoon period. It is not just a circle, but a spiral turning clockwise, tending to tighten each time. The survivor becomes invested in the cycle too, certainly, but that is a result of the abuser’s manipulation:

you can’t leave me, I need you; you can’t leave me, I love you more intensely than you’ve ever experienced; you can’t leave me, or I will make you hurt.

Within this context, if a survivor reacts violently against their abuser, it is not so much an act of participation within the cycle of violence, but a blow of self-defense, a push towards freedom. (Of course, it is often not this linear.)

But there is yet another cycle of violence, and it is generalized. Statistics, for what they’re worth, say that 30% of those who are abused as children go on to abuse their own children. Fredy Perlman’s Against History, Against Leviathan is this narrative on a global scale. Perlman tells the story of many different sets of people resisting their conditions, fighting their oppressors—then forming their own new Leviathans, corrupted by the harm they experienced, sick with the virus of civilization (some would say.) These situations are horrible and complicated and not this simple—there are so many structural oppressions and points of history at play—but, still, this pattern seems too true to look away from.

You could believe from all this that we are poisoned at the core by all the damage we’ve experienced, too likely to repeat the past—but that eliminates the possibility of choosing otherwise, means that resistance is never real or possible for long, that all lines of flight hit brick walls. I don’t think so. I think it is true that we are nearly doomed, and that it is delusional and dangerously short-sighted to believe otherwise—but I don’t want us to use that as an excuse to give up. We must think and talk together and try again; only in that effort can we learn.

So in my own life: the shit I experienced so long ago became a self-destructive tendency. Then it started to harm my practice. Now those tendencies have begun to negatively affect others.

All of the times I’ve had sex I didn’t want to have, not because the other person forced me into it but because it was a narrative I had become used to playing out—I thought that I was only hurting myself, but now I see that I was hurting others too, that the wrong lies not only in forcefulness but, sometimes, in withholding an answer. The bad habits it has taught me take me to the edge of an unthinkable precipice.

After I escaped my mother, I felt invulnerable to further abuse. But, when shades of it come to me after all, it feels more like real love than anything positive I have freely engaged in. It is so hard to decline.

I consider the bitterness and resentment I feel when others are doing projects I feel incapable of because of my circumstances or insecurities, and I see an enemy.

I try to create the magic moments of revolt I have sometimes stumbled into with others, and they fall apart, crumble in my hands. I become afraid to even try.

There are other ways to look at it, of course. Surely our desire to fight against what has been done to us (and who does it and how it is done to everyone) is based in our own experience, the most legitimate basis for attack. One could argue that one of the reasons why so surprisingly many privileged people are anarchists— or, conversely, why it seems that a disproportionate number of anarchists have experienced abuse—is because surviving abuse can give you a basic ability to empathize with others, to feel an impulse towards solidarity, that privileged people would otherwise lack.

What happened to us is terrible, but it fuels our desire for something else, our hatred of the world and need to resist it. This is not to psychoanalyze our resistance away, but rather to recognize our emotional resources so that we may more explicitly draw on them. Knowing what we do about how abuse has shaped us, we can also look at our practices critically, search for the poison in us, and build a tension towards dissolution rather than replication.

And it’s not all holding us back: we have learned practical skills in our personal attempts to survive, not only outdated defenses. We know how to smile when we want to cry; we know how to keep secrets. We know how to be beaten without making a sound. We know how to strike back in small but meaningful ways, and how to keep a little piece of ourselves out of their grasp, hidden and free. We have learned, in a very direct sense, that there really is an outside; that it may take years of failed attempts, but that one can escape not only in death.

Freedom lies in revolt;

we are good in a crisis, and the crisis is always on.

fever dream

i am illegible. i am convulsing and we are not fucking. your tongue cleans my wounds and we are not fucking. i swallow the sickest parts of you and we are not fucking. we are not fucking because we cannot fuck. fuck is irrelevant. fuck is redundant. you exhale down my throat and i breathe your breath. you spit in my mouth and i digest your teeth. i taste you - under my finger nails, in hair clinging to my cheek, in my death lines.

the lines blur.

all we are now is voice.

scream at me.

break the wall.

you give me the violence of your vocabulary.

animal. monster. faggot. scum.

your words do not name me,

do not bring me back into the

labyrinth of identity

(ripping skin,

endlessly stepping on needles).

animal. monster. faggot. scum.

you do not inscribe me

with Nature and Law and Light and Beauty.

no,

your words do not entrap

the fetid mire that is my body.

they open up

possibilities:

how many scars can my skin accumulate?

how many teeth can i fracture?

how much shit can i swallow?

how much nature can i profane?

your words loose in me

the monster hiding:

stabbing her father,

castrating her self.

do your violence to me.

set fire to our childhood homes.

let old selves die.

until we are born,

the horror we want to be.

every time i attend a consent workshop, sexual assault accountability discussion, or even read a survivor support zine, i fight back tears. every fucking time it’s a trigger for me to hear that the most important thing you can provide as support is to listen, to believe. when i went to my family about being sexually abused they continued the abuse by screaming at me for hours, insisting that i was lying. i was moved into my grandma’s house where my life was threatened if i ever ‘said anything about the men in her home.’ my mom tried another go with housing me a year later. another three years of abuse. i ran away when i was 15.

my family didn’t want to believe me when i told them i was being assaulted because my abuser was, to them, virtuous beyond reproach. this belief was fostered by the parallel created between my mother’s first husband (my dad) and her second (my abuser.) my dad was an alcoholic and outwardly abusive, so i was actually happy when mother divorced him. my happiness was shortlived; soon after the divorce she brought home something even worse. with this one the abuse happened when no one was looking and didn’t leave visible marks. to everyone except me it seemed like my mother had improved her situation.

nobody wanted to believe that this man who held a steady job, went to church, and gave expensive gifts could ever be the monster i was calling him out for being. i was told that i was ungrateful and awful to make up such stories about someone who did so much for my mother and i.

many things have become a part of my core beliefs and personality based on my formative experiences. some i try to resist, and others i try to see as the positive takeaway from an overall negative time in my life. having my mother, a figure imbued with assumptions of unconditional support, turn against me and not believe and defend me, has made it so that i struggle with speaking up and asking for help. i feel like she defended her partner over her child because she felt like she had to maintain a relationship with a man in order to survive. this understanding has been the basis for my cynicism of the power dynamics between men and women. the societal pressure for two by two pairings and the inherent co-dependence that ensues is what i primarily blame for the destruction of my relationship with my mother. as a result of not having familial involvement i also have a heightened understanding of the importance of the bonds established within my community of chosen family.

my abuse also made me question everything that my abuser believed in. his value as a person for making money and spending it on gifts (bribes), has definitely formed my anti-work/capitalism ethic. his faith in god as our holy father and his conviction to submit oneself to the authority of god has made me retch at any patriarchal pyramid scheme bullshit ever since i was made to submit to his authority. and i guess that plays into my overall distrust of any person in a position of authority.

i sometimes wonder what my life would be like if my mom never met him. would i be less cynical? would i be able to communicate easier? would i have a relationship with my bio family? i don’t really know and i try to not fixate on the things that might have been different and focus on the things that i can have an impact on. helping other folks in their struggles helps me deal with my own. i know that i would have figured that out, even if i never had to struggle in the ways i have.

“All that is ruined in you, I’ll cherish. All that you have endured, every pain you have known brings me closer to you; I would not take you into my heart but for each crack in yours. Every bruise your mind cannot get rid of, every little detail that is hideous I find beautiful beyond words. It is only with the exposure of our horrifying scars that I can learn to love, and be loved.”

– Delete me, I’m so Ugly

on vigilance: toward another impossibility

1: a consideration

what does it mean to be an anarchist survivor of abuse what does it mean to have been abused by an anarchist what does it mean when men who want to fuck you because you have “good politics” keep fucking you when you don’t want to what does it mean when your lifelong comrades lie to you for years about what they did what does it mean when you don’t trust anyone what does it mean to be real, really real, about how capital has poisoned your idea of intimacy over and over again what if the first person who ever abused or manipulated you was an anarchist, a popular one, one whose press people still recommend you read zines from, what does it mean when the friendships that were the only thing you could still believe in are sick with the rot of cruelty, manipulation, emotional expropriation, how do you cut out the rot, can you cut out the rot, why can’t you find exactly where the rot is, if you could find it you’d kill it, if you could find it you’d kill it, you call them scene enmities as to discount them when you’re looking for someone else to trust but you know it’s something else, know your reputation is monstrous if you talk shit, what does it mean to have survived anarchist abuse, what does it mean in our tiny scene, its impotent gestures utterly destined for failure (we know this) except god damn can its practitioners destroy you easy, what does it mean to be an anarchist survivor of abuse, if anarchy as a politic has taught me to take solace in nothing then what’s the next step, more zines about accountability processes, more baseball bats, except nothing leaves you unabused if anything anarchy means failure to me and even if the failure isn’t mine i know that there is no other side, there is no abuse>>[slide missing]>>communique>>then healing complete, abuse terminated, history wiped clean, trust restored, community standard upheld, perpetrator cast out, redemption achieved, ready to block capital flows in accordance with my ability forever and evermore, amen

anarchy’s not like a video game and neither are our lives. you can’t win on the other side of abuse even if you kill the motherfucker. you can’t and won’t win. all the actions that want you to win feel like shit because they are shit. you don’t have to disappoint anarchist narratives of healing and accountability, too. you’ve got enough disappointment in the depths of yourself. you don’t have to pretend you don’t feel like shit.

i see one attainable goal for abusers, which is a lifelong commitment to not abusing anyone else, ever. accountability per se should be understood as a failing gesture at an impossible project, that of unabusing the survivor, of building a world where people aren’t systemically encouraged to abuse one another. survivor solidarity means understanding that i’m not going to feel better, and that you don’t get a pass from feeling bad. solidarity is agreeing to feel bad with me for a while. maybe really bad, maybe a long while.

2: an expansion

lest we fucking forget that many kinds of abuse can be understood, for the guileless marxists among us, as a special kind of forced value extraction: a coerced accumulation of care from the abused to the abuser. the flows of affect and care that reproduce culture and therefore subjectivity are unequally maintained by women; emotional abuse forcibly directs those affective gestures away from the surviving subject and onto the abusing subject; the abuser’s selfhood is affirmed endlessly through the survivor’s maintenance of it, and at the expense of the survivor’s selfhood. one leaves the abusive situation shattered, unsure of which affective bonds can be trusted, starved for care or attention whose implicit purpose is not control, confused as to where oneself ends and the other—much less a network individuals connected by affinity—begins.

on a better day i’d argue against conceiving of all social life as the circulation and maintenance of affects and subjects mirroring the circulation and maintenance of capital and the commodity, since that framework is limiting and terrifying. but in terms of abuse, it can perhaps be useful to lay out an analysis that treats sociality as perhaps not work, but as circuits that produce value, keeping in mind particularly the material consequences of surviving abuse.

which is to say: we can conceive of the things we do to maintain each other as gestures that have value both to a capitalist machine that requires healthy subjects to perform labor and to ourselves and each other, as creatures who need to be cared for or take part in a social life. the marxist intervention into the concept of labor is that people who work for wages are subject both to giving over the value of their labor to an employer (“consensually”) and to the extraction of profit from that labor, which accumulates in the pockets of their bosses. the wage they receive can never be commensurate with the work they do, because the work goes toward reproducing capital. by this token, we might understand abuse as that which reproduces the abuser’s selfhood unilaterally, with a violence that mirrors that which is inherent to capital exchanges. abusers mimic bosses not only in their manipulation of survivors, but in the value of which they rob the survivor.

“abuse” is a nebulous term, handed down to us in clinical settings to explain our maladaptive behaviors and busted attachment styles, a floating signifier easily taken up to mean “anything we don’t like” to end conversations and win arguments. especially as anarchists, who need not value civility or niceness for the sake of making our enemies comfortable, it can be difficult to find the lines between “mean” and “shitty” and “abusive” to describe the behaviors of people who have wronged us.

a key component of my understanding of abuse is the idea that abuse seeks to control or maintain power over an individual, to use their body, mind, work, feelings, speech, etc. to one’s own ends and without their consent. one would want to believe that even without an elegant definition of the boundaries of abuse, we might “know it when we see it,” but its invisibility, or its congruence with capitalistic modes of social interaction, is perhaps the most damnable aspect of abuse. it can be awfully fucking difficult to see close up, since coercion and manipulation are implicitly encouraged by capital as long as their goal is the production of more value, more “success” for the individual. “it’s a dog-eat-dog world out there.”

one must be careful, then, of where the value goes. it’s hardly news that we as anarchists require a particular kind of upkeep, wedded as we are to trouble. the labor we do to produce affinities, projects, spaces, and actions is obviously bound up in the care-labor we do to maintain one another. we need not put one above or below the other—indeed, they’re inextricable—but responding to abuse in our circles requires the pluck and ire we bring to all of our projects as anarchists. it seems absurd at this point to bring up another reason why we should pay attention to patterns of abuse in anarchist circles, but the prevalence of abuse among anarchists would suggest that it couldn’t hurt to remind ourselves to pay attention.

3: a call

love, and the feminized subjects out here know this, is hardly a space for opening up: safety there has long been an illusion. home is where the heart is hardened to the regular violences of the family. it’s infuriating to hear anarchists invoke invented community standards or purported shared politics as evidence that abuse cannot occur among us, that our spaces are safe, that we’ll take care of each other so we can be dangerous together. risk pervades a culture structured around violence. anarchy is not safe, and neither are we.

we all know better than to oppose violence for its own sake: if violence is that which erases, which cuts off subjects from producing, then we need it for our project of ending this world. but we must take care to not end each other. i am struck again by the impossibility of the anarchist project set against the seemingly endless ability of anarchists to render each other impossible: abused but alive, surviving, hated and hateful in a hellish world.

being careful with each other isn’t enough. active consent models aren’t enough. accountability isn’t enough. if they were enough, we wouldn’t need them in the first place. but if you’re on the team, be on the fucking team. we are owed vigilance as survivors of abuse. we know we will not get it. we are compelled by capital to get better. we know we cannot do it. we are asked even by our so-called comrades to heal. but there is no self uninflected by capital, and there is no going back after abuse. “solidarity is vigilance redistributed.”[2] we are owed vigilance. vigilance need not reproduce the opacity of self-satisfied call-out culture. vigilance requires attending to nuance, to sussing-out, to messy overlaps and incoherent subjects, to weird nonlinear narratives. vigilance may require conflict. we know better than to rely on assumed communities. confronting affinity and lack of affinity in the wake of abuse is tiresome, complicated, noxious. so be it.

vigilance doesn’t mean taking sides in callouts that have nothing to do with you, or arranging your allegiances for social gain in the wake of someone’s alleged abuse: vigilance has no room for a failure to critically approach abuse. the expansiveness of “abuse” as a category, combined with the rhetorical weight it holds, makes it an easy concept to, well, abuse. rape is not the same as emotional manipulation; intent matters; there are degrees. none of it should be regarded lightly, but the ways in which abuse destroys us are multiple, the consequences varied. surprise: we live in a world that defies simple binaries; survivors of abuse become abusers; situations can be mutually abusive. it serves no one, least of all survivors, to address abuse as a monolith. vigilance is required.

All this is to say that it isn’t easy and it feels horrible: to be abused, to support ` the fucking team. pay attention. you’ve chosen the impossible project.

so do it already.

“There is a point when shit comes at you with such brutal force, everything is associated with trauma. Once this threshold has been reached and it is no longer clear where the pain is coming from, we forget language and everything detestable is exposed to the violence of our swinging limbs.”

– Delete me. I’m so Ugly

trauma, abuse and anarchist practice

I am not exactly sure how to say what I aspire to say. I feel uncertain of how to begin a conversation or piece about trauma as it relates to my Anarchist practice, because these things feel so convoluted, hard to separate. Both are innate and inform each other, and I don’t always know how and when and in what ways. This is due in part to how entwined abuse and trauma are with Anarchism, both ideologically and in my lived experience, and in part to an ongoing internalized struggle I am engaging in constantly. It is a conflict of implicit and contradicting desires, like being accountable for myself in a broader context of community, friendship, trust, and commitment, and just doing without thinking what I know viscerally to be effective methods of surviving and coping.

I feel a certain amount of disassociation coupled with an innate capacity for understanding that is complicated to navigate, and is hard to discern and articulate. Abuse is such a fundamentally damaging and harmful violation of trust that it inescapably colors the ways in which people perceive and experience the world. I can have a certain amount of self-awareness and still not understand all of the ways in which abuse manifests in my life.

I do know that my survival led me to desperate acts, and to body and mind-numbing behaviors and substances for which I was criminalized and marginalized. These experiences were translatable to a larger context of systematic oppressions that felt easy to see and place myself within.

It feels impossible to live in the world, but we survive somehow, and we attempt to paint a picture that makes more sense then the one we are staring at. Anarchism articulated certain truths about the world and gave me a means to begin reconciling with myself little by little. Through that process, still ongoing, of reconciling with myself, I learned to breath a little slower; live; develop over time deep, meaningful, trusting friendships; and fuck in ways that didn’t seem possible. I think people have come to similar places by very different means, but my Anarchy and my trauma have never been separate because it’s impossible to separate myself from the trauma I have experienced. Thus they inform each other, fuel each other.

It didn’t take a huge leap in consciousness to relate trauma to a larger context of oppression and violence. In making that connection through the lens of Anarchism, I was able to shift my conception of self and identity from this place of feeling desolated by particular acts by specific persons to a critique of the larger systemic conditioning and perpetuation of abuse that lends itself by design to the creation of monsters, perpetrators, and victims. Anarchist rhetoric and energy tried to make sense of the monsters I still wanted to love, and took the spotlight off of my own experiences, and allowed me to step outside of my pain body a little.

My early exploration of anarchy and mutual aid built a bridge that connected my isolation to the isolation of other folks, and there was something hopeful about this. Perhaps what I am trying to say is that where trauma led me into isolation, addiction, remorse and self-deprecation, Anarchy led me into a place where my struggles became relatable, gave me a context to understand the underlying motivations for patterns of abuse and made me feel connected to a larger network of people with similar experiences. In this way Anarchism created space for me to heal and engage in ways that would not have been possible otherwise. I felt elated by a framework of critical resistance that was ripe with possibility and complexity, one that was integrated and uncompromising in its demands for change.

Living in a world axised around the absence of coercion, violence, force and authority feels very practical in contrast to the abusive relationships rooted so deeply in force, shame, and negligence that we experience everyday, and which made me feel heavy and helpless. I have always been circumstantially at odds with the powers that be, and I have always felt like I had to fight for my life, which felt disposable, but Anarchism demanded vengeance and annihilation and I wanted that more than I wanted to die. This emotional and reactionary sort of desperation is indicative of my Anarchism in practice.

It is clear that abuse perpetuates itself, that it affects us so pervasively that we are prone to repeating, engaging in, or otherwise participating in the furtherance of abusive behaviors. My Anarchist practice is very much inflected by the fear of this potential in myself, and motivated by a refusal to be complacent in my potential participation in these cycles of abuse. I am an Anarchist because nothing else makes sense, and it is among comrades that I am inspired to act in ways that make me feel alive. Thus it is my early experiences with abuse and trauma that led me to Anarchism in the first place. I don’t remember a necessity to deconstruct my pre-existing notions of “privilege” or “violence” or “danger” or whatever in order to come to a place where I could develop a relationship with anarchist principles and actions.

I do realize, though, that in order to live the kind of life I want to live, as persistently and fearlessly and dangerously as possible, I have had to and continue to engage in a lot of intentional self-evaluation and work. I have struggled with addictions and other mind numbing coping mechanisms. I have struggled with being dependable, flighty, impulsive. Trauma affects the ways in which I relate to my own body, obvi; I internalize stress, fatigue, agitation, and periods of deep unrest, depression, anxiety and hopelessness. It limits my ability to engage as consistently and persistently as I would like to imagine possible for myself.

I feel the most able in crisis, in times or situations that require a lot of reactivity. I can deal with a lot of emotional chaos without feeling weighed down or immobilized by it as it’s happening. These are practical and useful skills. I am intuitive, perceptive, sensitive, patient, and pretty levelheaded in a lot of ways, and these are all strengths that are, at times, a part of my practice. I feel especially good at conflict resolution, mediation, facilitation, legal defense type stuff and various support efforts. I think that I am fairly accessible, easy to talk to, and receptive, which feels important, and I think that these skills are derivative of past experiences.

On the flip side of this, I think that trauma has also been hugely limiting in the ways I have engaged with anarchist projects and community. I don’t have the energy, stamina, or attention for sustaining projects long-term. I don’t even have a deep interest in that, which feels weird to say. I mean only that my own practice feels more reactionary, more spontaneous, and the skill set that feels inherent to me and my experience is more centered around responding to moments as they’re happening.

I am retrogressive maybe in the sense that I am at my best in states where I am ‘triggered’ to respond in ways that feel very inherent to my essential character. I feel especially capable in times of urgent necessity. I can hold a lot of disparity, heartache and excitement without being halted by it, while being, in a way, moved to act or react because of its existence, its intolerability. Highly stressful situations feel easier to navigate because that environment of reactivity is what I am most familiar with; the monotony of daily life, of work, of sustaining meaningful friendships, paying bills and doing all the things feels a lot more overwhelming. It takes a great deal of effort to resist self-destructive behavior in the face of that monotony. There is a paradigm that I am trying to speak to of great strength, intuition, and perception, juxtaposed with a tendency towards just surviving days, of being easily distracted, impulsive, in varying states of depression. The really intense empathy and sensitivity I feel in light of my experiences drive me to act, but also affects my tolerance of the odious act of day to day living.

There are a thousand ways to dissolve

Sexual assault,

I have no more words for you, I disappear

Into murder, beating

Murder, plots on the linoleum floor

There are no ways of actualizing a total dissolve

Of sexual assault and murder

Counting rail ties between here and Seattle

99, 100, 101

I could throw you off a grainer

Abandon you in White Fish, mile post 1217

Or tie you up under a chase

But scheming is like a runaway train,

And I don’t want to be closer to get you away

Pepper spray, bottle rockets

Mile markers between here and Kansas City,

Read something like

“I should have been older to have touched you”

Read something like a ten hour drive

Something like pepper spraying a room full of people

Might be worth it

If I can aim at your eyes

Something like igniting a fist-full of bottle rockets

From here to the Great Plains

To set the fields between us ablaze Might be worth it if

It takes out the churches with the tall steeples

It takes out every monster who felt up

Drunk 14 year old me at every party

From here to Nebraska

From here to Astoria

From here to Monterey Bay

From here to I was wearing my mother’s bra

Out of shame for my small tits, and now I

Wish they were concave, so every monster’s

imprints weren’t fossilized on my chest

Like the limestone pyramids

That we walked to without socks

During our hippy white trash vacation to

Escape to the mountains

"There hasn't been any reason, in quite some time, to imagine a different reality than this. Our bodies grow tried as they take repeated blows; it is increasingly difficult to create that secret world in our head, the world saturated with beauty and congregated in conflict."

-Delete me, I'm so Ugly

[1] Semprun, Jaime. “Apology for the Algerian Insurrection.” Tr. Karim Al Majnun. Edition de l’encyclopedie des Nuisances, 2001.

[2] berlant. http://supervalentthought.com/2013/10/26/the-game-8-and-9/