Alexander Reid Ross and Joshua Stephens

About Schmidt

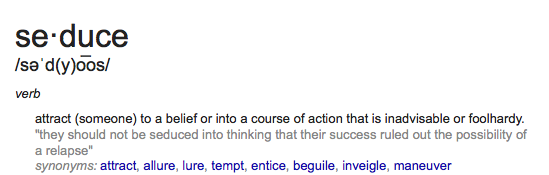

How a White Nationalist Seduced Anarchists Around the World

The Basest Service to the Revolution

Storm Clouds over the Battlefront

Ideological and Political Alignments

Michael Schmidt’s Complicated Relationship with National-Anarchism and Pan-Secessionism

Politico-Cultural Dynamics of Denial

On the Question of Infiltration

Appendix: AK Press Facebook Post dated September 26, 2015

Appendix: Michael Schmidt Responds to Allegations of White Nationalism

Researching the white ultra-right

Chapter One

The Basest Service to the Revolution

On a sunny day in July 2008, six months before the publication of Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism (Counter Power, Vol. 1), co-author, Michael Schmidt, met with fellow members of the Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front (ZACF) at his cozy bungalow in Johannesburg, South Africa. It was a gorgeous day, so the four collective mates sat down comfortably on Schmidt’s wooden furniture in his spacious garden, near a lemon tree while his White Swiss Shepherd puppies, Loki and Freya, came out to sniff their guests.

There was a lot going on in Schmidt’s life. He was in the midst of working on Black Flame alongside academic Lucien van der Walt — a work that, since publication in early 2009, has sold roughly 4,000 copies. According to Charles Weigl, a collective member at the book’s publisher, AK Press, “the average nonfiction book in the US sells less than 250 copies a year, and 3,000 over its lifetime.” Sales-wise, Black Flame stood shoulder to shoulder with recent editions of works from some of anarchism’s most recognized names, and Weigl told us that Black Flame was “still selling steadily,” until late this past September.

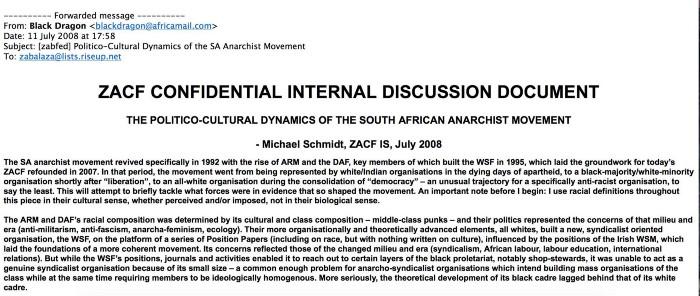

However, as internal secretary of the ZACF, Schmidt had taken time out of his busy schedule to host a meeting in a different context. Part of the business of the meeting was a “confidential discussion document” circulated by Schmidt titled “Politico-Cultural Dynamics of the South African Anarchist Movement” (which will be referred to as “Politico-Cultural Dynamics” from this point on). One person at the meeting, who asked not to be named for this piece, recalled, “Michael asked about thoughts on the document. Everyone was awkwardly quiet and pretended they hadn’t read it.”

The text at the center of discussion that July day was his take on why anarchist organizing had foundered in post-apartheid South Africa. “Blacks,” he wrote, are “incapable of other than the basest service to the Revolution.” Schmidt explained that while the best anarchist militants “have almost without exception been proven to be whites,” black anarchists, “while good comrades, have not been up to the exacting standards” required of them. He goes on to state that “in [South Africa], where race is often more important than class as a determining factor in consciousness, we find that white anarchist militants are the de-facto leading echelon, while most black anarchist militants merely follow.”

Due to “Bantu national education” and economic disparities facing black people in South Africa, Schmidt claims, “logical process, self-discipline and autonomous strategic thinking has been strangled at birth.” He goes on to list an alphabet soup of different international groups that he claims gain strength from cultural homogeneity, and presents the ZACF as “a white politico-cultural anarchist movement” that cannot “merge” with “the black politico-cultural anarchist movement… at this stage of history.”

Schmidt states that white culture is not culturally identical by calling on his relationship with Black Flame co-author, van der Walt: “For example, Lucien considers himself a ‘European settler,’ despite his Afrikaner heritage, whereas I consider myself an ‘Afrikaner’ or ‘white African’ despite my Anglophone heritage.”

“So, are [South African (SA)] black anarchists unequal to the task [of revolutionary organizing]?” Schmidt asks, well into the document. “After 16 years of activism, I’m forced to say no — as long as the task is established for them under the influence of SA white anarchists.” In other words, black South Africans are equal to the task, but only if the terms of struggle are defined by South African white anarchists. The platform, in this case established by Schmidt and a cohort of white colleagues, becomes a compass to lead allegedly feeble-minded Africans toward their own liberation.

Black Flame, White Blindspot

Such a compass was in the works, as Schmidt and van der Walt worked on their book through the coming months. At five hundred pages, Black Flame is widely considered the first major (non-anthology) work in some time — perhaps ever — to provide a global historical account of anarchist movements. Many viewed the work as a kind of “Anarchist Bible,” or what Immanuel Ness, a professor at City University of New York and author of New Forms of Worker Organization: The Syndicalist and Autonomist Restoration of Class-Struggle Unionism (PM Press, 2014), had described as “perhaps the most important contribution [to] the global history of working class movements from an anarchist perspective.”

While its proletarian message rang true to many, Black Flame did not come without its controversy. The construction of anarchism one finds in its pages is keenly specific, and strikes a deliberate contrast with contemporaneous anarchist literature seeking to grapple with the gritty realities of anarchist practices increasingly deployed by on-the-ground struggles. Alongside the influence of prison-abolition movements, post-structural theory, and leftist solidarity for Indigenous uprisings like the Zapatistas in Mexico, a variety of shifts reaching back some two-decades had effectively put the anarchist tradition’s classical preoccupations with capitalism and the State on equal footing (and in conversation) with struggles around patriarchal and racial domination, Indigenous and gender self-determination, colonialism, and disability. In contradistinction, the construction of anarchism put forth by Black Flame reasserts a temptingly simple primacy of class struggle and workers’ movements with the not inconsiderable force of “big A Anarchism.”

Black Flame maintains historical roots in what its authors deem the “broad anarchist tradition,” drawing from what is known as platformism. Andy Cornell, formerly the Anarchist Studies postdoctoral fellow at Haverford College and author of Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Mid-20th Century (forthcoming, University of California Press), argues the tendency emerged in the first decade of the Russian Revolution, reckoning with the direction of the left in the hands of the Bolsheviks. “[Platformists] felt the Russian anarchist movement, and the international movement more generally, was theoretically weak and had insufficient organization to push the revolution in an anarchist direction,” Cornell explained. “So they argued for an anarchism that was more clearly committed to class struggle, and that accepted formal organizations. [Basically,] figure out an organizational structure, develop a strategy, [and] stick to it.”

In Schmidt’s view, the politics of race, gender, sexuality, and other forms of what he calls “identitarianism” are implicit within revolutionary class struggle, so centering them rather than class leads to compromises and half-measures. Perforce, reading Black Flame, one is hard-pressed not to discern this contempt for “identity politics,” and in its indictments, the voices cited are conspicuously white.

Noel Ignatiev, the white firebrand behind the journal Race Traitor, figures as often and substantively in Black Flame as W. E. B. du Bois. Curiously, Schmidt and van der Walt misidentify Ignatiev as a “former-Maoist.” In fact, Ignatiev’s big claim to fame came in 1967, with an article critical of the Maoist tendency within Progressive Labor, published along with Theodore W. Allen’s famous essay, “The White Blindspot,” recalling du Bois’s brilliant book, Black Reconstruction (published in 1935).

A Sordid History

Like most white men until conscription was abolished in 1993, Schmidt was drafted into the South African military, which was putting down black unrest during the end of apartheid. This, he claims, radicalized him, and he visited Rwanda as a journalist just after the genocide of 1994, growing increasingly politicized. Professionally, he appears to have been respected more for his administrative capabilities than his journalism. He founded the Professional Journalists’ Association of South Africa (ProJourn) and The Ulu Club for Southern African Conflict Journalists, and has a personal network of associates that spans an influential set of counter-culture celebrities and highly-regarded media figures.

In conversations with some who’ve known him personally, Schmidt is described as warm and sensitive — a beguiling and experienced man, with a gloominess carried from his time in Rwanda, where as a journalist, he witnessed horrors such as “piles of dead bodies” stacked in warehouses. He is open about his PTSD. From other, less-sympathetic accounts, he figures as an intellectual gatekeeper prone to contrarianism and rowdy outbursts during bouts of drinking. He is known to have come to blows with at least one friend during heated arguments fueled by alcohol.

“Politico-Cultural Dynamics,” however, offers a more intimate portrait of Schmidt’s organizing career. During the 2003 drafting of the constitution for the previous incarnation of the Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Federation, Schmidt declares that he proposed a strategy based on the Brazilian group Federação Anarquista Gaúcha, which maintained a “‘specific’ core, with outlying nodes of social insertion.” With this structure in mind, Schmidt called for distinguishing racially distinct collectives for whites and for “less ideologically convinced black cadre.”

He continues, “My attempt during the drafting of the ZACF Constitution to have this divide explicitly recognized as (white) rearward collectives and (black) frontline collectives was defeated as it was felt this would unduly emphasize the race/class divide in the Federation.”

The defeat of Schmidt’s attempt to create ideologically and structurally separate collectives for white and black cadres is important, inasmuch as it shows that Schmidt’s racialized understanding of platformism was and is not widely shared. While the relative silence that followed the defeat of his proposal raises critical questions, it appears that Schmidt’s explicit use of “the platform” as an intellectual power structure best understood and controlled by whites was of his own making.

This was a major change that broke down the collaborative aspect of the federation — in particular, doing away with action groups in places like the 99%-black township of Umlazi. Within two years of his initial, rejected frontline/rear guard proposal, the Federation had been cut in half; two years after that, in 2007, it was dissolved completely. According to Schmidt, this change took place, due to its black members’ “ill-discipline, inactivity or a lack of theoretical understanding.”

However, the Federation was re-founded as the Zabalaza Anarchist Communist Front with a new structure. Schmidt explains the implications: “[T]he organization lost its last black members in Swaziland, reducing it from a biracial ‘international’ organization to a white ‘national’ organization.” The ZACF had gone from a six-branch, multiracial anarchist Federation that was too broad to have a membership roster, but was engaged in activities throughout South Africa and in Swaziland, to an all-white group with only six members dedicated specifically to the development of ideology and propaganda.

According to Schmidt’s “Politico-Cultural Dynamics,” he had been there every step of the way — first advocating unsuccessfully for a racial divide in the Federation in 2003, then arguing for a political hardening into three collectives in 2005, then finally re-founding the group as a “white ‘national’ organization” in 2007, with some six members and three “supporters.” Considering what Schmidt named as his own cultural understandings of his Afrikaner identity, it is clear that he puts “national” in quotations to connote white South Africans who share a common “culture,” which he understands as a standard for organizational specificity and unity.

“[T]he underlying ideology at work here, [is] a more or less direct inheritance of the European New Right. That is why the ‘culture’ / ‘race’ nexus seems so important to him,” says Peter Staudenmaier, an historian at Marquette University and co-author (with Janet Biehl) of Eco-Fascism: Lessons from the German Experience, reflecting on Schmidt’s internal document. “There is a lengthy tradition, especially after 1945, of shifting ‘race’ talk to ‘culture’ talk without really changing the content, and it’s that same conceptual fuzziness that the far right plays on (the radical left hasn’t done much to clarify the fuzziness either). In that sense, this story is a good example of anarchists’ failure to work through the complexities of race not only at a political level, but at an intellectual level.”

Schmidt’s conclusion of “Politico-Cultural Dynamics” is summed up in one telling passage: “[P]erhaps we should not be too quick to seek partially-qualified black members, or be ashamed of our whiteness — for we after all reject both the Maoist theory of ‘white skin privilege’, and the radical counter-theory of ‘race-traitorship. Instead we should proudly recognize that we are (currently, and presumably temporarily) a white anarchist movement.”

Thus, Schmidt encourages the “white ‘national’ organization” to be proud of itself as forming the “white anarchist movement” after purging black militants, who he describes as ill-disciplined, lagging, and incapable of meeting “the exacting standards of platformism.” It was those “exacting standards of platformism that Schmidt would attempt to explain with Lucien van der Walt in Black Flame, gaining greater influence throughout the world through their widely read book. Through Schmidt’s attempts to reconstruct the platform, it would seem as though he saw himself as leading the whites in laying out the “task” of revolution for the “ideologically less convinced” people of color whose “inactivity” had brought about the failure of the anarchist movement in South Africa. However, across more than a hundred pieces of evidence, we located far more sinister ideas at work in Schmidt’s own handiwork whittling the ZACF from a multi-collective federation down to an all-white intellectual “front,” and blaming it on people of color.

Errata: The authors would like to note that Ignatiev does in fact seem to have been briefly a member of a tendency close to Maoist analysis. This, however, does not change the fact that “white privilege” analysis developed from WEB du Bois on, and in a critical relation to Maoism. It is not “Maoist,” as such.

Chapter Two

Michael Schmidt, posing for a photo which he posted under a pseudonym on white supremacist clearinghouse Stormfront

Storm Clouds over the Battlefront

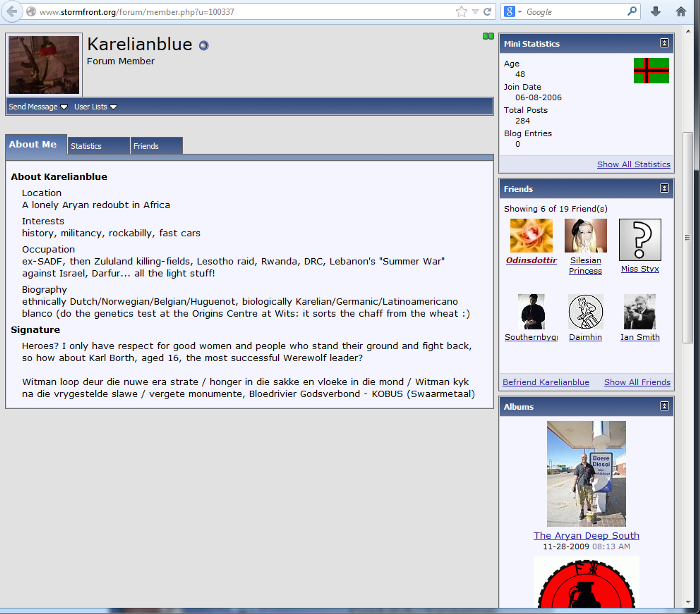

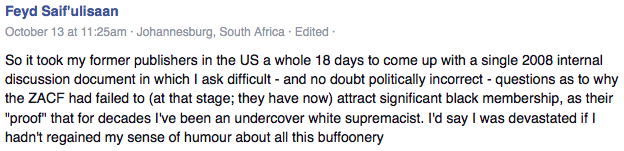

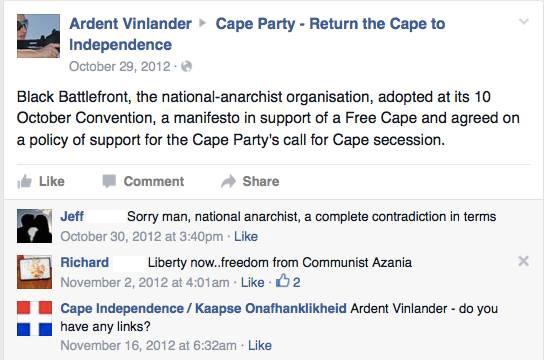

This past September, in response to incontrovertible evidence of Michael Schmidt’s racist activities, AK Press announced it was cutting ties with him and ceasing all printing of works connected to him. He quickly responded, mounting a preemptive defense in which he admitted opening and managing an account with Stormfront, arguably the preeminent online white supremacist forum, linked to some 100 racially-motivated killings.

Michael Schmidt’s personal profile on Stormfront

The account dates back to the summer of 2006 — three years before the publication of Black Flame. In the lifespan of the account, he logged nearly 300 posts. Curiously, his explanation of it dated its origin a full year prior:

[S]ince 2005 until I shut it down recently, I maintained a profile on the white supremacist website. Let me explain: I am an investigative journalist by profession and in 2005 was working at the Saturday Star in Johannesburg. My beat included extra-Parliamentary politics — social movements, trade unions, and political organizations from the ultra-left to the ultra-right. My editor Brendan Seery allowed me to set up a Stormfront account under which I could pose as a sympathetic fellow-traveller in order to keep an eye on what the white right-wing in South Africa was talking about: in other words, this was professionally vetted by my editor.

Schmidt went on to state that he lied consistently for years about a group connected to his Stormfromt account, called Black Battlefront. In his statement, he openly confessed that he ran both the Stormfront account and Black Battlefront, but his admission makes confidence in his explanation difficult. Simply put, the details are bizarre. The deception in question, according to his mea culpa, included using a bout of anterograde amnesia in order to pass off a character he allegedly created on the internet, and then portrayed as an acquaintance in the employ of a shadowy private security company. According to this story, this character may or may not have hacked his Stormfront account to plant a post about Black Battlefront to frame him.

The defense goes on to mysteriously discard that fabrication while retaining a tale about another unnamed intelligence agent from South Africa’s National Intelligence Agency (NIA), who he says had recently come out to him after spying on a friend for two full years. He could not admit to the Black Battlefront profile at the time, he claims, for fear that the NIA would learn of it, and retaliate. Since Schmidt has claimed journalistic privilege over his “source,” we cannot substantiate the story about the NIA agent who suddenly had a change of heart and came clean to the close friend of the anarchist on whom she’d spent two years spying. However, the Facebook page for Black Battlefront, as well as one of its moderators, retained several friends in common with Schmidt’s own more public profile. There seem two plausible readings of the narrative, each equally bizarre. Either he was attempting to entrap his own friends, or Black Battlefront remained a well-kept secret between Schmidt and a close circle of like-minded peers. There nonetheless remains one thing his story oddly fails to establish in any way: that it was a personal page used to infiltrate the virtual networks of white supremacists and national-anarchists.

It’s further confounding that Schmidt did not inform anyone about either of these apparent agents (the one he invented, as well as the one purportedly real) until suspicion began to swell around his links to white supremacist and white nationalist websites and groups. It also defies explanation that Schmidt is adamant in protecting a person who spied on the South African anarchist movement for years. What we know for sure, beyond Schmidt’s hazy memory, is the truth about his Stormfront profile, which appears lockstep with Schmidt’s public life when examined in closer detail.

Profiling KarelianBlue

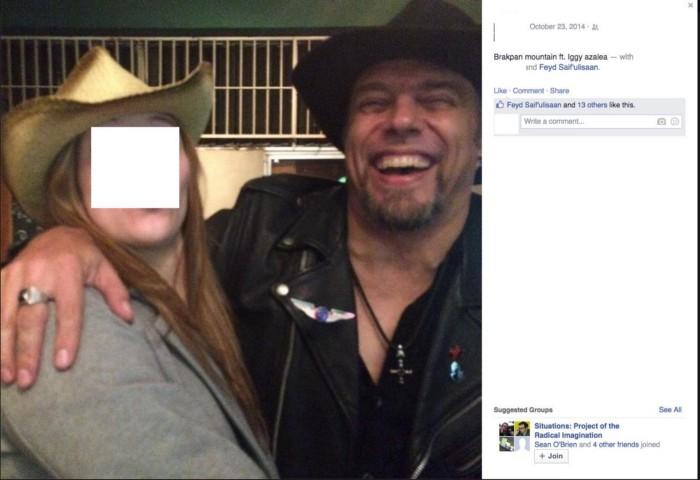

As well as a possible reference to a kind of cigarette, Schmidt’s preferred Stormfront profile name, “KarelianBlue,” suggests a reference to his blue eyes and purported ancestry (the Karelians were an ancient people from Northern Europe, a reference echoed in the Norse names of his dogs), as well as a popular white supremacist pop band, Prussian Blue. On Stormfront, he details his tattoos, describes his neighborhood, holds forth on his (deeply flawed) knowledge of leftist and fascist movements, and even hosts a smiling photograph of himself with a shaved head in front of a Boer filling station, appearing to repurpose the sign in a macho, racist joke. Another photo on the Stormfront profile of KarelianBlue shows a blonde woman wearing a Nazi sidecap that one source confirmed to us Schmidt owns. If the intent was to go undercover, all the personal details Schmidt shared on Stormfront would undermine the anonymity of a simple “research” project.

Publicly, he enjoyed hot rod culture and his old Mustang, going to metal shows, and drinking beers with friends. Privately, he indulged in ignominious racism through an anonymous profile on at least four white supremacist sites. To what extent these scenes overlapped, it is not entirely clear, but on his profile, KarelianBlue lists as interests, “history, militancy, rockabilly, fast cars” — perhaps a clue that he shared his white supremacist views with communities beyond anarchists.

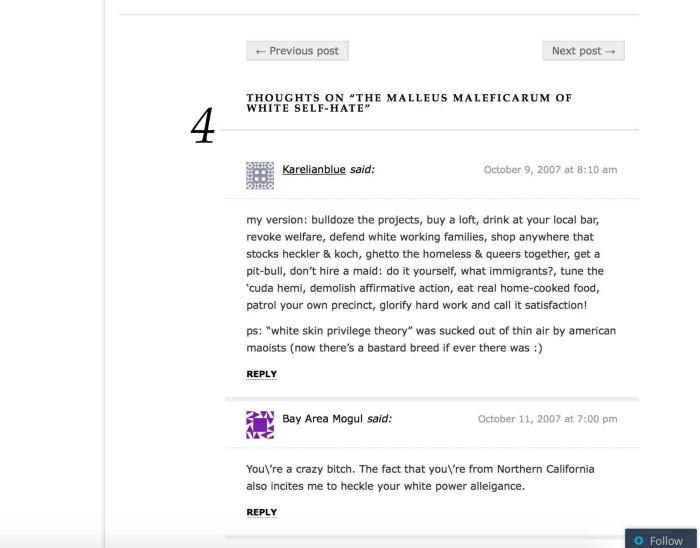

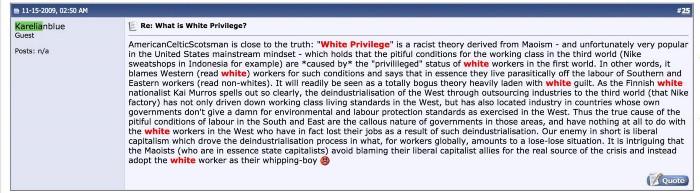

One of the sites in the white supremacist blogosphere that KarelianBlue visited and commented on is a blog called The Spoils of War managed by someone calling themselves, “the accidental ‘racist.’” Commenting in 2007 on an article comparing the analysis of white privilege to medieval witch trials, KarelianBlue waxes prosaic:

Although Schmidt describes his posts on Stormfront as “pretty neutral in tone,” we found them to be consistently otherwise. They regularly refer to Africans as “k*ffirs,” a highly derogatory slur, when they do not refer to them as a “subspecies”; they also lament the dying out of the white race, “white genocide,” and call for potentially violent “fascist skinhead” intervention. Well afield of mere research, Schmidt’s Stormfront profile and other interventions in the white supremacist blogosphere encourage white supremacist organizing, offer strategic options and critiques of antifascist analysis, and discuss historical trivia about the “Good Guys of the Waffen SS,” as well as provide links to Nazi paraphernalia for sale online.

In posts marked with the black and red Nordic cross backed by green — the flag of the short-lived Republic of Karelia on the border of Russia and Finland — KarelianBlue corrects other users about the radical history of the Soweto riots, while also deriding the Black Consciousness movement for reverse-racism. Publicly, in writing done under his own name, Schmidt has shown no compunction about smearing African politicians with allegations of “black racist” and anti-white “hate speech.”

To put what Schmidt describes as “occasional” posting into perspective, it yielded an average of more than one Stormfront post per week for the first four years. Many were more informative than inquisitive. Often, they were deeply personal, almost introspective. Stormfront seems to have functioned for him as a forum for a kind of soul searching, where he sought to identify problems holding him back from securing a romantic partner or some other variety of success. His activity depicts an isolated, deeply frustrated radical blowing off racist steam.

Desperate, esoteric, sad windows into an incredibly turbulent soul, described on his profile as a “lonely Aryan redoubt”.

Networking as a Skinhead

On his profile, KarelianBlue declares that his heroes are those “who stand their ground and fight back,” and his earlier posts are full of a sense of alienation in a neighborhood that is decaying. He writes vividly about an ongoing turf war in his neighborhood between whites and blacks, in which it appears the whites are losing.

In a post dated August 20, 2007, he writes about defending his white neighbors from potentially “dangerous” people of color:

I don’t have firearms as that attracts the attention of the authorities: instead I prefer bladed weapons, my favourite being a vicious, curved Gurkha kuki [a Nepalese blade]. A month ago, the white American student across the road heard a noise and called me for help. I ran out, around the block, with the kukri tucked back against my forearm (out of sight, but perfect for CQB [Close Quarters Combat]) and found nothing, but I sure impressed the Yank.

The same blade appears in a selfie on one of Schmidt’s Facebook profiles.

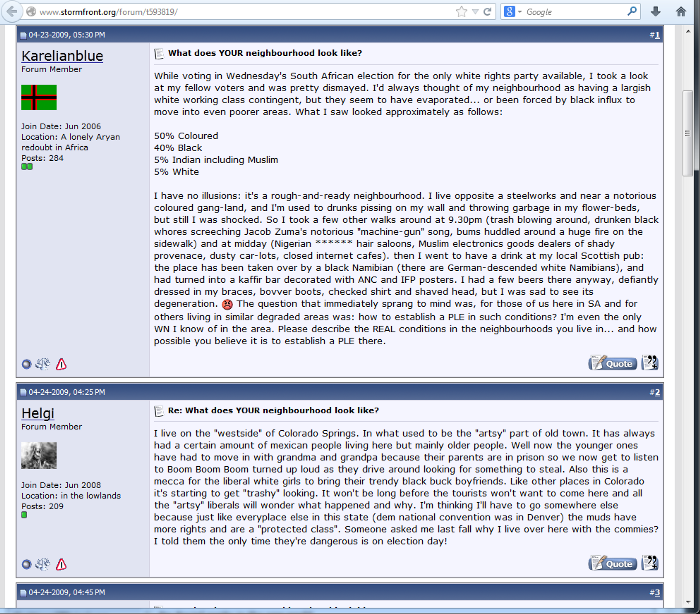

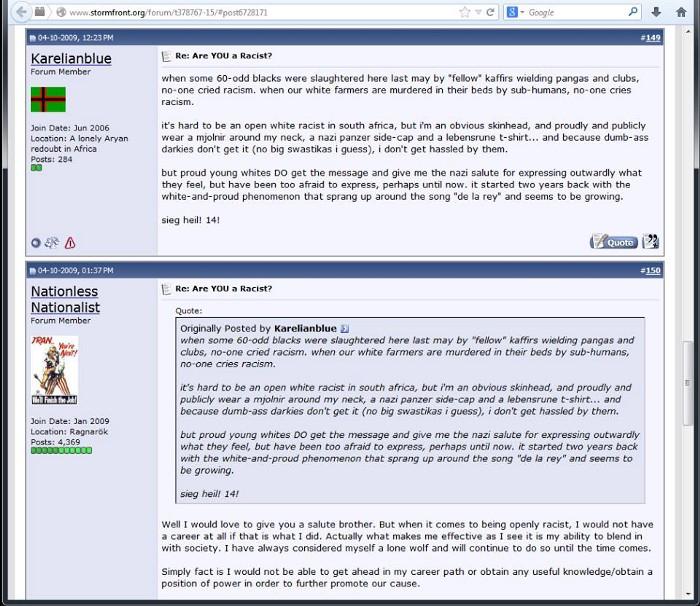

In a post from April 10, 2009, KarelianBlue brags, “it’s hard to be an open white racist in south africa, but i’m an obvious skinhead.” Indeed, photos on his profiles from the time period show him to be presenting as a skinhead. Less than two weeks later, KarelianBlue posts about wearing the traditional skinhead gear — boots and braces — and walking into a mostly-black, formerly-Scottish bar to make his presence known:

These posts appear to reveal significant and corresponding details about his own private life, defining himself a fascist skinhead defending his neighborhood with lethal weapons in the unfriendly territory of South Africa under the “k*ffir state.” If Schmidt let these feelings show in public, the presentation was usually masked and indirect, often during drinking bouts with close friends. According to a source who was close to him, his drinking would often result in revealing utterances. “Why do they get to call us white trash, when we don’t get to use our words for them?” Occasionally, he would raise his voice and make racial slurs as though relieving himself of a burden. But for whatever reasons, he generally kept KarelianBlue bottled up. One former friend of Schmidt’s described his personality as “compartmentalized.” Sober, the racist beliefs, the championing of “white trash,” and the feeling of victimhood at the hands of Affirmative Action and the black majority were generally vaulted.

Ideological and Political Alignments

One revelation that Schmidt alerted us to in his lengthy, public statement was that he used his Stormfront profile to enter into correspondence with Troy Southgate, who he describes as “the founder of ‘national-anarchism.’” Schmidt revealed not only correspondence with Southgate, but that he had “talk[ed] on a personal level with Southgate and his cronies.” That Schmidt made no attempt to disguise his identity on Stormfront is both conspicuous and mysterious, for the simple fact that, had any of his anarchist peers recognized him (as some eventually did) his open visibility throws into question the status and function of his relationship with Southgate and his national-anarchist circle.

More shocking still, if only for Schmidt’s own openness about it with sources who spoke to us, was that while self-identifying as a “fascist skinhead,” he publicly supported the Freedom Front Plus Party (Vryheidsfront Plus, FF+), voting for them in the 2009 elections. The party is a political splinter group from the white nationalist paramilitary group Afrikaner Volksfront led by former army commander Constand Viljoen. As a right-wing coalition of groups, the Volksfront included the Boerestaat Party, and other ultranationalist white separatists. The FF+ currently proposes a Volkstaat in western South Africa that would provide land reform to shelter whites from Affirmative Action and the “black majority.” Since Africans did not occupy much of South Africa when the Dutch settlers came, FF+ members claim, a considerable amount of land is authentically Boer territory.

In a post from this time period (pictured above), dated April 23, 2009, KarelianBlue laments the high number of voters he saw at the ballot box in 2009, and claims he voted for “the only white rights party available.” A month after his account of voting for the FF+, KarelianBlue posted a demographic survey that breaks down class divides among whites, stating that they present “not quite the picture of white rule that is so often peddled by our k*ffir state.” Interestingly, while the statistics show that there are more poor whites than affluent whites, they also show that the white “emerging middle class” outnumbers the white poor. His statistics also fail to show the proportion of whites making up the ruling class as opposed to non-whites, who The Economist described as composing a mere “sliver” of the South African economic elite.

As pertains leftist rhetoric and theory, one does well to examine a November 15, 2009 post by KarelianBlue at length, if for no other reason than it clarifies Schmidt’s public analysis:

Though the characterization of Maoism is at best mistaken, KarelianBlue offers something of a class analysis in the post. “Our enemy in short is liberal capitalism which drove the deindustrialization process in what, for workers globally, amounts to a lose-lose situation,” he writes. Just over four months later, on March 6, 2010, in a post related to Iceland’s resistance to austerity, KarelianBlue exposes the nature of his anti-capitalism, asking the rhetorical question, “Is this not a Semitic-banker plot to destroy one of the world’s most homogenous Aryan cultures?” The anti-Semitic, anti-capitalist analysis lines up with what’s sometimes called “Third Positionist” fascism, defined by some as “neither left (Marxist) nor right (capitalist), but something else.”

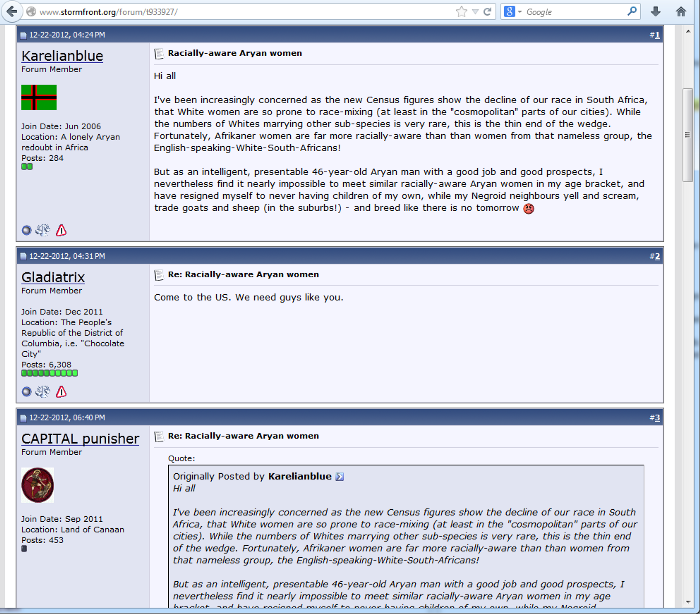

Elsewhere, KarelianBlue delves deeper into racist terrain through additional reflections on demographics. On December 22, 2012, he looks into the South African Census, claiming that it “shows the decline of our race in South Africa,” and complaining that “White women are so prone to race-mixing (at least in the ‘cosmopolitan’ parts of our cities).” He goes on to say, “While the numbers of Whites marrying other sub-species is very rare, this is the thin end of the wedge.”

In a post created less than a year ago, KarelianBlue expresses delight that “Afrikaner women are far more racially-aware” than “English-speaking-White-South-Africans,” but laments:

Personal Descriptions

As goes his own identity, KerelianBlue declares on November 17, 2007:

For Schmidt, the nation is a cultural development marked by centuries of wars and slavery; hence, his designation between white and black culture and the “white ‘national’ organization” in his “Politico-Cultural Dynamics” memo.

Detailing his practice of cultural identification, KarelianBlue declares on April 10, 2009:

He finishes the post “sig heil! 14!” To the casual reader, the number 14 is at best obscure, at worst almost meaningless. In the world of white nationalists, it’s code for the “14 words” of neo-fascist terrorist, David Lane: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for White Children.”

Corroborating the information in this post, we found photos of Schmidt on one of his Facebook profiles wearing the mjolnir:

His surreptitious wearing of the sidecap in public was confirmed by a source who knew him. Furthermore, KarelianBlue writes about where he purchased his Nazi paraphernalia: the War Store at the Military History Museum. An eyewitness source confirmed Schmidt’s patronage of the store.

Fascism to Schmidt is neither costume party nor fetish, however. It runs as deeply as white nationalist beliefs in pan-European ancestral spirituality. KarelianBlue describes his tattoos on July 25 of last year, declaring, “my uniform is my skin… Every race has historically marked its skin with symbols relevant to its culture and whites are no exception, whether they align spiritually as Christian, Norse, Teutonic, Celtic or other.” He discusses his “14th Century family crest, which includes two crescent moons as symbols of the crusades my ancestors fought in.” Regarding his “Scythian chieftain’s tattoos,” he explains, “the Scythians were a white horse people who ruled the steppes from present-day Ukraine to the Altai mountains).” In truth, the Scythians were a nomadic people originating in modern-day Iran, and have become an important figure in the narrative of the emergence of the Indo-Aryan white race and the “birth of Eurasia,” which features prominently in neo-fascist literature.

He also lists his “lebensrune” tattoo. While the actual Nordic-German Algiz rune is not itself related to racism, it was only dubbed the “lebensrune” in twentieth-century Germany, first by occultists and then by the Nazi Party, who utilized it in Stormtrooper uniforms. It has been employed regularly since by neo-Nazi and white nationalists groups, the militant fascist skinhead group, Volksfront International, the the US National Alliance, and the Flemish nationalist Voorpost. Of his tattoos, Schmidt proclaims, “It means I’m serious about my heritage.”

These tattoos, taken in full, represent a deep expression of pan-European traditionalism and pride, linked to crusades and ancient warriors. The narrative inked on Schmidt’s flesh is in keeping with the cultural pride of colonial Europeans in Africa, bearing what scholar Tamir Bar-On calls an “ultranationalist or pan-European, pro-colonialist and militaristic tone calling for the revival of elite, chivalric warrior societies where honor and courage superseded material considerations” (2007, Ashgate). Schmidt’s honest descriptions of pan-European cultural signifiers based in crusades and German mysticism seems to provide a fuller picture of the white cultural identity staked out in 2008 ZACF internal document.

In a post from May 10, 2009, KarelianBlue tells his Stormfront forum that he “attended a private boy’s school in joburg [Johannesburg] for the full 12-year-stretch, matriculating in ’84.”

Recalling the system of seniority that carried over to the army when he signed up after school, KarelianBlue connects the hierarchical structures to the British system: “i was in favor of a mentoring approach and when i was an ouman myself [I] had a throw-down fight with another ouman [superior] who was being needlessly vicious towards his roof [inferior].” When he went to university, KarelianBlue claims, “[I] resolved i’d get extremely violent with anyone who even dared” to demean him. “In sum,” he announces, “i’d say my attitude is that if the system teaches respect, self-discipline, cleanliness and upstanding character, then okay. if it just serves to brutalise and crush the spirits of the younger then i’m opposed to it.” The question of anarchy hovers in the midst of this moral and ethical question: if a hierarchical system utilizes mentorship in an organic and orderly fashion, then it can be considered healthy; otherwise, the order must be disrupted.

Less than a month later, KarelianBlue strikes out against the enemies of such an ethical order — figures who promote disorder or, perhaps worse, an order of shame and guilt. Unable to limit his response to just one enemy under an illustratively titled thread:

Mandela was later the subject of a weird article from Schmidt published shortly after his death, titled, “From demonic terrorist to sainted icon: the transfiguration of Nelson Mandela,” which describes the late President of South Africa as the satanic-angelic leader of a politico-religious cult.

The Battlefront Analysis

While receiving accolades for Black Flame in 2009, Schmidt distanced himself from the ZACF. Former friends told us he was complaining of a lack of time, money, and personal interest. One piece of what he had been developing at that time frame was the analysis anchoring Black Battlefront:

Schmidt’s use of the term “political soldier” is significant, developed by the Strasserist faction of the English fascist party, National Front, to describe both rural paramilitaries and urban skinheads. Otto Strasser, the guiding theorist, had been a member of the original Nazi Party before being kicked out in 1930, at which time he formed a group called Black Front in order to grow a clandestine base of “true national socialists” against the Hitler faction. That the group Schmidt created took the name Black Battlefront suggests a nod to some sort of similar clandestine operation within the South African anarchist scene, through which he could encourage privately racist analyses among key friends. Put another way, his group seemed intended to function like a secret social club for anarchists who believe in militant white separatist ideology in keeping with what some neo-fascists call “ethno-pluralism” — the need of different ethnicities to live in separate racial enclaves in order to preserve true cultural diversity. In a post to his profile, KarelianBlue included three red, circular patches with different “Black Battlefront” logos:

In his September 27th public statement regarding the revelation of this “network”, Schmidt claimed that the site was initiated in 2009, as he stepped up research into the “national-anarchist” movement. Nobody else could know about this group, he insisted, not even his ex-wife — lest the NIA catch wind of his investigation. Again: Schmidt’s more-public Facebook profile shared friends with both the group and its moderator (another top-secret profile Schmidt created) before the site went down; unless Schmidt was working to entrap his own friends, he was clearly using it as a focal point for a “racially aware” cell within the anarchist movement. Furthermore, the site was actually initiated in 2006, three months before his Stormfront profile, exposing another timeline anomaly in Schmidt’s account. According to a web designer we talked to, Schmidt and a friend pitched him the idea for developing a similar white nationalist internet site as early as 2003, but they were refused. This was a year before Schmidt proposed a division between white and black collectives in the ZAC Federation. The first post in Black Battlefront, published March 3, 2006, was the “Platform of the Anarchist Communists of Bulgaria, 1945.”

His identity for Black Battlefront is “Strandwolf”:

the brown hyaena found on the lonely Atlantic beaches of the Namib desert: with more powerful jaws and greater stamina than a lion, the hyaena hunt in matriarchal packs and, inverting their clitori, are impossible to rape. They are viewed by the indigenous people as spirit-animals… Strandwolf is a ghost in the machine of the African night, a spectral flicker on the shores of the Skeleton Coast, a low-slung hunter on the night-time highway that stretches away from the rolling smokes of Johannesburg into the bleach-and-acetate reaches of the platteland where gaunt wind-pumps scratch stars in the sky.

The analogy evokes the militant, lone-wolf character advocated by Louis Beam, a famous Texas Klansman who advocates for “leaderless resistance” through acts of political assassinations, individual murders, bombings, and general terror. It was Beam’s ideology and his relationship with San Diego-based white supremacist Tom Metzger and his acolyte Dave Mazzela, that helped shape the consciousness of the early west-coast skinhead movement through an organization called White Aryan Resistance.

The “creed” advertised on the Black Battlefront blog is practical:

Strandwolf calls for revolutionary anarchism as an answer both to the modern multicultural project and the apartheid era exploitation of poor whites and blacks, alike. The postings on Black Battlefront were sparse between from 2006 to 2009. However, after midnight on February 17, 2010, two posts appeared, authored separately by “white African national anarchist” and a shadowy, Ukrainian woman named “Ardent Vinlander.” Vinlander’s article is dedicated entirely to a cultural reading of race and class, as well as a sense of nationalism rooted in conquest. In the other article, “white African national anarchist” explains:

‘Medieval’ is the closest that blacks have come to civilisation, while some still today languish 10,000 years behind the Europeans who gave Africa its science, industry, infrastructure, education, medicine and large-scale agriculture, most of it fallen into terrible disrepair under black rule since the late 1950s. In order to, if not forestall this decay, at least build the bulwarks of a white redoubt strong enough to stand against this darkening tide, we require organization.

The same post declares that revolutionary anarchism must be informed by Jim Goad, Nestor Makhno, and Troy Southgate, realizing that:

in order to be truly grounded, we need to be scrupulously egalitarian and what this means in the southern African battlespace is that we are compelled to judicially recognize the right of white anarchists and black anarchists to establish their own separate, culturally-distinct formal organizations and informal networks.

Schmidt’s cultural racism carries over from his “Politico-Cultural Dynamics” memo within ZACF, to Black Battlefront, which appears to show that the latter was formed through his disaffection with the former. Furthermore, Schmidt’s desiderata of a “white anarchist organization” to develop independently as a “national” group seems to be at work in his writings as Strandwolf at this time. While we can’t be certain how much support Schmidt had during this endeavor, his admission that he fell in with Troy Southgate and his “cronies” seems to imply that his blog was more than just an isolated project. Instead, it was an outreach tool with some (perhaps extensive) network behind it.

Schmidt, of course, has claimed that this elaborate, circuitous trail — as often confused as confusing — was ultimately nothing more than an investigative ruse carried out for the purposes of journalism. Setting aside the correspondence between the sentiments of his allegedly undercover persona and his own publicly-stated beliefs, and his bizarre attributions to conspiratorial counter-intelligence operations and selective amnesia, there is nothing in his online activity that, in principle, anyway, conflicts with a (perhaps staggeringly overzealous) long-con for the sake of investigation.

Only, it wasn’t.

When we tracked down Brendan Seery — the editor Schmidt claims authorized his journalistic foray into the depths of the white-nationalist internet — he seemed bewildered by Schmidt’s story. “Mike did work for us as a senior reporter and on a number of big stories,” he told us. “[A]nd because of his seniority and the way newspapers work, I would not have to give him permission at all to investigate. That would be something a good investigative journalist would do off his own bat.”

Schmidt having laid oversight at Seery’s feet aside, it was never likely Seery would’ve authorized such an undertaking, if only because gathering information through deception, while standard for police, is at odds with basic journalistic standards. “My style as an editor is that journalists should be as upfront as possible in order to get a story with subterfuge only as a last resort,” Seery told us. “If, however, you mean that we ordered or gave permission to him to pose as a right-winger, then I certainly don’t recall that.”

Since Seery ran the Saturday Star until 2007, after Schmidt left and after the Stormfront account went up, there’s zero chance that a subsequent, incoming editor approved Schmidt’s alleged project.

Chapter Three

Strangely Quiet and Troubled

After the publication of Black Flame, Michael Schmidt began distancing himself from and finally left the ZACF. According to one source within the group, they’d done their “best to recruit new people, including a ‘colored’ member who joined in 2010… Michael [Schmidt] left at around the same time because he had ‘ideological differences.’ That was shortly after he voted for Freedom Front Plus in the national election.” Speaking to the double standards of the organizational culture Schmidt had helped create at the ZACF, a source told us that Schmidt received no official criticism about voting for the FF+, but a female member of the ZACF was disciplined around the same time for wanting to join a feminist reading group.

The ZACF has since continued its transition from Schmidt’s era to a far-more inclusive group, and it was during the lengthy debate around members joining collectives with ideological differences that Schmidt issued his parting letter to the ZACF on March 12, 2010, declaring he would no longer be a member or supporter (except in spirit). “I’m burned out after 20 years of activism and am feeling pretty emotionally damaged by the longer-term effects of my divorce, of my disillusionment with the working class as a result of the 2008 Pogroms, and of all the killings and heavy stuff I have seen over 20 years of journalism.” Schmidt’s divorce took place before 2006, but was still as fresh in his mind as Rwanda in 1994, and what he calls the 2008 “Pogroms,” in which a wave of xenophobic riots swept South Africa. However, there was more in the air at that time than Schmidt let on.

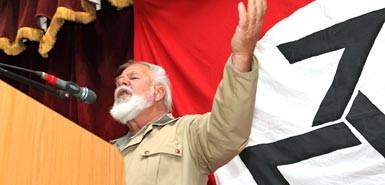

Less than a month after the Black Battlefront posts on February 17th, and a week before Schmidt left the ZACF, Eugene Terre’Blanche, a founding leader of the white nationalist paramilitary group Afrikaner Resistance Movement (AWB), was killed by farmhands. It had been less than a year since Schmidt had voted for the FF+. The links between these two groups are important to note in understanding Schmidt’s rationale: the FF+ was founded by the leader of a paramilitary Afrikaner Volksfront group called the South African Defense Force, which joined the AWB in 1994 to violently disrupt the vote that dissolved the segregated Bantustan of Bophuthatswana — one of the final victories over apartheid. The two groups had connections, but they remained distinct and, like many white supremacist groups, often combative.

Eugene Terre’Blanche, backdropped by the AWB flag.

On his Stormfront profile, KarelianBlue vented his spleen over the Terre’Blanche murder:

I have yet to go out and read what the mainstream yellow press has to say about this, but i’m certain the black genocidaire parasites will be celebrating this cowardly hate-crime murder. This is where the ‘kill the Boer’ and ‘kill for Zuma’ hate-speech leads: to the very real slaughter of aryan South Africans.

The post is followed by four, red-hot angry emoticons. Within a matter of days, Schmidt had penned and published an article warning of potential “Boer genocide.”

With a lengthy and difficult title — “Death and the Mielieboer: The Eugène Terre’Blanche Murder & Poor-White Canon-fodder in South Africa” (Mielieboer roughly translates to “maize farmer,” a symbol of Boer nationalism) — Schmidt’s article, published via the anarchist website Anarkismo, contemplated the murder of genocidal killer and pro-apartheid paramilitary leader, Eugene Terre’Blanche, as an act consistent with a movement toward genocide against white South Africans. Even the title seemed to associate Terre’Blanche with the Mielieboer, the archetypal hero of the rural, white Afrikaner nationalists who supported apartheid.

Casting “a strangely quiet and troubled” shadow over the death of Terre’Blanche, Schmidt relayed that his hatred of the white nationalist leader had “all but drained away.” Schmidt explained that he was especially put off by the fact that “the way Terre’Blanche died was the way so… ordinary; it was the way many poor rural whites die, hacked to death in their beds for reasons grand and petty, criminal and (despite strong government denials) racial” (his ellipses).

“It’s not that there is a ‘Boer Genocide’ (as yet) as many on the far right already proclaim,” claimed Schmidt, “but some powder-keg combination of race and class is killing our white farmers at an alarming rate.” The combination of race and class at the root of “farm killings,” Schmidt claims, is actuated by the “link between [African National Congress (ANC)] hate speech calling for the killing of the Boers and, well, the actual killing of Boers.” These claims of hate speech resonate with Schmidt’s rhetoric of “black racism,” “white rights,” and “Boer genocide” to formulate an ideology that sees racism not as a power relation developed through the historical narratives of colonial Europe, but as a static relativist doctrine that views white people as victims of racist oppression.

Schmidt followed this statement claiming that “Against [the] tense backdrop [of failed land reform], the murder rate of white farmers is four times higher than the rest of the population — in a country with the highest murder rate in the world of any country not at war — and the viciousness which accompanies many killings belies purely criminal motive.” These farm killings are racist crimes against whites stoked by the ANC, Schmidt insisted, and in his first draft of this article, he defiantly ended his piece with the lines, “Will I not speak out merely because I am not a Boer? No; I’ve said my piece. But will I celebrate, knowing it will be presumed to endorse the slaughter of poor rural whites? Hell no!”

Schmidt’s statement reads like a searing indictment of the ANC, which he believes is stoking angry “black genocidaires” into militant action against poor whites in order to turn the working class against itself. However, according to the SAPS National Planning Commission, the number of white murder victims in police analysis of murder dockets is a mere 1.8% (disproportionate to the 9% of the population that is white), many of whom are not rural poor, putting to rest the idea of incoming genocide. The number of murders per 100,000 people in South Africa in 1970 was 32.12; the number reached a peak around 1994, during the transition to democracy, and had actually declined below 1970 levels by 2011/2012, so violence in South Africa, far from reaching terrifying new heights, was declining.

With regard to the rate of farm killings, Schmidt’s claim that Afrikaner farmers are being slaughtered at four times the average rate was rejected even by Genocide Watch, the only human rights group that has entertained claims of genocide. In their July 12, 2012 report, Genocide Watch listed the situation in South Africa as “polarization,” two stages away from actual genocide. However, these terms are contestable, according to the fact-checking organization, AfricaCheck, since numbers of killings between 1994 and 2012 by the Transvaal Agricultural Union do not take into account that nearly 40% of those killed in farm attacks were non-whites — even though the one tenth of South Africans who own more than 80% of the land are overwhelmingly white. Putting things into a crisper class perspective, the South African Institute for Race Relations explains that commercial farmers are twice as likely to be killed as the average citizen.

Genocide is defined as “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.” Since white farmers do not make up a nationality or ethnic group, and since the rate of killings correlates to class position, no other respectable group has agreed that “Boer genocide” is a phenomenon worth studying. In fact, Human Rights Watch has criticized not only the term “Boer genocide,” but the term “farm killings,” denouncing the amount of focus given to farm killings in South Africa, as opposed to the crimes committed against black farm workers:

Violence against farmworkers and residents is perpetrated not only by farm owners and managers, with whom they are in daily contact, but also by private security companies and vigilante groups hired by farm owners. Those seeking to uphold farmworkers’ interests have also been harassed and assaulted when they have sought access to farms.

The discourse of “white genocide” rose to prominence during the 1960s and ’70s, as the colonial grip of the North Atlantic began to loosen its hold. Novels like Camp of the Saints by Jean Raspail (much appreciated by the former-leader of France’s radical right populist party, the National Front, Jean-Marie Le Pen, among others), stoke fear of a terror rising in the South — from India to Algeria, wherein the maniacal, sub-human barbarians begin raping and slaughtering whites by the thousands, and suddenly, off the Mediterranean coast, an invasion fleet appears from Africa preparing to exact a phantasmagoria of revenge. The notion that African self-rule would mean the genocide of all whites has since become standard fare for white supremacists, and has even helped shape neo-fascist rhetoric around “the immigration problem,” rather than “the Jewish question.”

A former leader of the Nazi Party of America, Harold Covington lived in then-Rhodesia during the mid-1970s, and has become one of the foremost spokespeople on the subject of “white genocide” in the US. After living in Rhodesia, Covington moved to North Carolina where he purportedly took part in organizing the 1979 Greensboro Massacre — the brutal shooting of five members of the Communist Workers Party during an anti-Klan rally in broad daylight. Covington claims to have fled the US in search of asylum in the UK, where he helped create a violent, racist skinhead group called C18. Finally settling in the Pacific Northwest, Covington became a leading exponent of a white secessionist movement under the slogan of the “Northwest Imperative.”

Another important promulgator of “white genocide,” Dylann Storm Roof proudly wore the flags of Rhodesia (now called Zimbabwe) and apartheid-era South Africa on his jacket before carrying out the June 18, 2015, massacre of six black parishioners in a historic church in Charleston, South Carolina. After the shootings, Covington weighed in: “there will be more of this kind of thing in the future as our people finally begin to respond, sluggishly and spasmodically and incorrectly, to the ongoing genocide.”

Frazier Glenn Miller, the white supremacist who murdered three people outside of a Jewish Community Center in Kansas City on Passover Eve last year, argued during his sentencing that “diversity is a code word for white genocide” and that the killings were justified on the basis of preventing its ongoing threat. Schmidt’s language of “white genocide” is the same rhetorical device used in his Stormfront posts, and the same deployed by Covington, Roof, and Miller.

Afrikaner Nationalism

Rather than the killing of Terre’Blanche as an opportunity to discuss the harsh, racist climate faced by African farmhands, and call for increased solidarity to end the conditions of farm killings, Schmidt brushes off the history of exploitation of Africans in order to rehabilitate an ultranationalist caricature of the Boer:

True, they were and often remain an austere, narrow people: one of their Calvinist sects, the Doppers, is deliberately named after the tin cap or dop used to extinguish a candle, the message being the need to extinguish the Enlightenment. And true, they often beat ‘their blacks’ with an offhanded cruelty, and at best established a paternalistic overlordship over them known as baasskap (boss-hood). But in their warfare with, suffering at the hands of, and eventual enslavement of the Bantu, a strange relationship developed: alone among all white settlers on the African continent, they self-identified en masse as Afikaners, as Africans, not Europeans, and severed their ties to their distant motherlands. The they [sic] and their black neighbours lived, ate, thought and died, merged and became inextricably intertwined: well over 10-million more black South Africans today speak Afrikaans, the slave’s idiom-rich, story-telling pidgin-Dutch of old, than do whites; while platteland (big-sky farmland) Afrikaners are fluent in African vernacular languages.

Schmidt’s declaration that Afrikaners have become “inextricably intertwined” with Africans obscures a rather glaring lacuna in his own historical approach. On the one hand, he argues that militant apartheid supporter Terre’Blanche is a representative of the Mielieboer, and on the other, he claims that the Afrikaners mixed with the Africans to create an authentic form of nationalism. In Schmidt’s view, Terre’Blanche somehow figures as a representative of Afrikaners intermixing with Africans — an unlikely prospect, but one worth investigating.

Considering the paradoxical manner by which the Boer “inextricably intertwined” with “African neighbors” (presumably not those forcibly removed to Bantustans, the equivalent of “Indian Reservations” in apartheid-era South Africa), it might be helpful to recognize that Terre’Blanche’s hero was, ironically, Shaka Zulu. This kind of appropriation of an African leader by white Afrikaners represents a synthetic identity pegged to colonial conquest, not of true respect or “intertwining.” (It is also the same sense of identity ideated by Strandwolf.) That more Africans now speak Afrikaans, the language of their former slave masters, does not go far to prove the authenticity of Afrikaner nationalism — the “stolen dream” of the Afrikaner Volksfront, which attempted to have Afrikaners identified as indigenous peoples of South Africa by the UN. Rather, it reveals the sheer historical magnitude of colonial rule.

While apartheid was by no means forced on poor whites from above, Terre’Blanche still does not represent the broad majority of Afrikaners. His death did not imply their death, or even a sign of their coming death. Rather than representing poor whites, Terre’Blanche represented a specific tradition of poor white extremists in South Africa that fought, through extralegal means, to deepen apartheid in order to better the economic situation of poor whites (less than 10% of the population at its height). These are the same kind of extremists who united to fight against the dissolution of apartheid Bantustans in 1994, and who Schmidt voted for in 2009.

Furthermore, Schmidt’s article obscured the fascist roots of Terre’Blanche’s AWB in order to present a völkisch apology for Afrikaner nationalism. According to The Routledge Companion to Fascism and the Far Right (2005, Routledge), the AWB represented “probably the most famous post-war fascist movement on any continent.” According to Schmidt, however, “Despite the childish shock-value of their swastika-like flag, they aren’t neo-Nazis (pagan Nazism gained little purchase in Protestant South Africa)” (his emphasis). Of course, numerous non-pagan examples of fascism have existed and continue to exist throughout the world. There have also been non-pagan neo-Nazis, like the American Nazi Party, among other groups, which adopted Christian Identity during the 1960s. Yet Schmidt confines his discourse to specifically-pagan National Socialism in order to cleanse the stigma of Nazism (and implicitly fascism) from the AWB, something he would attempt later and more controversially with national-anarchism. Instead, the AWB are depicted as “ultra-conservative Calvinists who dream of a separate white bantustan of their own — this being the same stolen dream of generations of Boers.” Given the horrifying crimes of the AWB, Schmidt’s sympathetic take on their “stolen dream” of a Boerestaat, is chilling.

Schmidt admitted his belief in the prospect of a Boerestaat to us in an interview: “A proper ‘Boerestaat’ would be a multiracial autonomous territory — as they always were — except that it would have to guarantee equal rights to all.” This call for a majority-white state in South Africa that would grant equal rights to racial minorities was virtually identical to his post less than a month before in Black Battlefront.

Rather than manifesting a neo-Nazi threat against the state, Schmidt claims, Terre’Blanche “was viewed by the radical right — and most anarchist-communists in SA probably can only concur — as a conservative buffoon, useful to the ‘New South African’ political-economic establishment as a scary outsider” who could motivate people toward a “moderate,” neo-liberal political option. While aligning anarchist perspectives with the radical right in a telling “red-brown” analysis, Schmidt (perhaps unwittingly) raised an interesting point: Terre’Blanche was among the most recognizable symbols of the Boerestaat, but he gave it a negative connotation, which it seems Schmidt resented. Schmidt sought to play down Terre’Blanche’s fascism, and attempts to rekindle his “stolen dream,” as an answer to the allegedly growing potential of the “Boer genocide” — a classic white nationalist narrative.

Perforce, after Schmidt published his article on Terre’Blanche, he received an incredible amount of positive attention from white supremacists online, who characterized him as a strong journalist speaking out against purported “white genocide.” In a very public way, racist white separatists all over the country were posting Schmidt’s articles to their blogs dedicated to “white genocide,” declaring that Schmidt was speaking for them. In an article on one right-wing blog called Why We Are White Refugees, the author intriguingly claimed that Schmidt declared his intention to form a vigilante group to protect white journalists from killings: “[Schmidt] has informed the ANC that should these journalists murders continue, he and his journalist followers shall be forced to step in to defend these defenseless Journalists their husbands, wives & children.”

While he did not appreciate so much exposure in the white supremacist blogosphere, Schmidt was still comfortable enough in our interview to use the notion of “white genocide” in terms of culture: “I wholeheartedly support the destruction of structural whiteness, that is, the race-supremacist structures of the European-originated part of capitalism (bear in mind that [S]ino-supremacism prevails in state-capitalist China where Uighurs, Tibetans, Manchus etc are racially suppressed). But as a white person living in Africa as a minority the bulk of which are working class (3,2-million out of 4,5-million), I taste a smack of genocide in the desire by race fanatics to destroy even cultural whiteness.” As elsewhere, we found Schmidt insisting that white culture must be preserved against the specter of racist, anti-white, Maoist traitors who apparently come with some whiff of genocide.

The Breakdown Begins

According to a South African web designer who spoke to us on the condition of anonymity, Schmidt and a friend checked in to ask if he could create a white nationalist anarchist website for them. The request was unceremoniously refused, but this was likely the beginning of what would become the media organ of “Black Battlefront.”

As Schmidt left the ZACF, Black Battlefront maintained a Facebook presence administered by an account that he now claims to have created named Ardent Vinlander. A female of Ukrainian origin, Ardent Vinlander was the person who Schmidt had originally identified as the brains behind Black Battlefront. Based on our research, it appears her Facebook account was initiated in 2009. She seems to have been Schmidt’s fantasy Aryan woman, who he invented out of thin air — a modern, Scythian woman of the Steppes of Eurasia who hates feminism and loves guns; a Steppenwolf come down to join the white African movement as a Strandwolf.

At one point in our interview, Schmidt told us that the architect of the site was “Ardent Smith.” When we mentioned that he had earlier stated the site’s architect was Vinlander, he did not respond. When we looked up Smith online, we could not find him (categorized as a male, not a female like Vinlander); however, we looked with a different account, and he was there with a faceless avatar. Among his posted links was an article called “Why Liberals Are Terrified of Anders Breivik,” by Robert Henderson, a radical-right columnist who has also written for a notorious neo-fascist publication of the “New Right” ilk, The Occidental Observer. Among Smith’s likes was the racist English Defense League. Far from a Ukrainian South African woman, Ardent Smith seemed to be an English man — likely created by Schmidt in order to communicate among neo-fascists in the UK without being detected by anarchist peers.

Another sockpuppet account, François Le Sueur, was initiated just a couple of months after the Terre’Blanche article. Based on photographs of his family with the last name Le Sueur, as well as confirmation from former friends and Schmidt’s own admission to us, we have concluded that Le Sueur is likely Schmidt’s given last name. Michael Schmidt is presumably an adoptive family name. Very much like his Stormfront profile, with its photographs of Schmidt and its personal information, the Facebook account he uses for Black Battlefront contains obvious personal information. This seemed to us to indicate that Black Battlefront and Stormfront were, in fact, closer to Schmidt’s personality than his more-nominal personas.

Le Sueur’s Facebook account profile bears a photo of a totenkopf — the “death’s head” skull and crossbones insignia used by the Nazi SS. His inaugural post is about a National Socialist named Louis Weichardt. The month after Le Sueur came into the world, however, Schmidt was struck down by a terrible case of meningitis, and then broke his spine during seizures caused by the virus.

On his more-public Facebook account, Schmidt stated in late-July, three weeks after going to the hospital, that it is his last day as an in-patient. He declared in his public response to AK Press dated September 27, 2015, “[I]n the subsequent months, due to heavy pain medication and perhaps some brain damage caused by the meningitis/seizure, my memory is patchy about what I posted online under my Stormfront and Facebook aliases[.]” In our interview, he told us that he stayed with a photographer and his wife for the following month. In fact, according to his Facebook profile at the time, on July 28th, the day he left the hospital, he claimed he was “convalescing with friends,” and by August 2, he was “back at home with a prodigious amount of chocolate to wade through.” According to another public statement, he was “cared for by some friends,” and in a different public statement, he claimed he was “visited” by friends, who he didn’t remember. On August 10th, about a week after returning home, he told his Facebook friends that he would be going to Cape Town for a week, and added with a sense of humor, “be prepared for a party.”

On August 20th, less than a month after leaving the hospital, he reported (via Facebook) that he was “walking without crutches at last (and [...] back from a very chilled week in Cape Town, for those of you who want to hook up in Joburg)!” By this point he was posting twice a day, lucidly, about a variety of subjects, including going on a date —one commenter told him to wear a condom, and he responded with full emotional maturity that the date was likely to be a platonic occasion. He described himself as “busy proof-reading Zabalaza: a Journal of Southern African Revolutionary Anarchism #11” by late-August (a post commented on by Ardent Vinlander). In early September, he was appearing on FM radio with Lucien van der Walt and posting comments critical of the “reactionary ideology of ‘wimin centered’ identity politics that preaching that men and women are enemy species.”

Why did Schmidt tell this story about his two-month “delirium” in which he might have posted anything on Stormfront or Facebook? The answer is right in his public response: “as a result of one of those posts in that period, in 2011 some anarchist comrades came across a Black Battlefront link to my Stormfront profile and in shock recognized my face.” There were two posts, actually, which came in early October and late-November, October having been more than two months and November having been about three months after Schmidt was released from the hospital in late-July.

According to two documentarians, Aragorn Eloff and Steffie, they became suspicious after Ardent Vinlander contacted them in late 2011 to suggest that they consider including proponents of national-anarchism in a film they were making about anarchism. They checked Schmidt’s more-public Facebook profile, and discovered Vinlander had commented on his Facebook profile at around the same time that new posts came up in Black Battlefront. This connection between Black Battlefront and Schmidt led them to Schmidt’s Stormfront profile, which they asked him to explain.

When approached about the content of his Stormfront profile and Black Battlefront, Schmidt now says he lied, claiming he did not have any connections to Black Battlefront. He also stated that his Stormfront profile went active after being “vetted by [his] editor” claiming he still used it for research. In his statements to Eloff, Schmidt revealed the original version of his story, which interestingly switches out the names “Ardent Vinlander” and “Ardent Smith” again:

“Some years ago, I ran into a curious character at a club who claimed to be of part Ukrainian descent, and who expressed an interest in the Makhnovists, so naturally we chatted. She was a late-30s woman called Ardent Smith, though she used another name when she befriended me on facebook. It turned out she works for a private intelligence firm called Erebus. She’s not often in SA, so we corresponded mostly by fb. Then some time later, she defriended me (fb didn’t alert me, but she’d just disappeared). That was the last contact we had [in fact, Vinlander posts on his profile in August, 2010]… In mid-2010, meningitis and breaking my spine laid me low for three months. At this time, my Stormfront profile posted a link to a “national-anarchist” fb group run by Smith and some others, called Black Battlefront. I suspected my profile had been hacked, but never got a satisfactory answer from the Stormfront moderators. This is, I believe, what alerted you to what was going on?… As a result of that single post, I was formally approached by the ZACF… to ask what was going on. I informed them of all of the above. By curious coincidence, a close friend of mine, who I don’t wish to identify, had just confessed to me that she had previously been employed for years by the NIA to spy on Dale McKinley — and by extension, friends of his like myself and the ZACF coms. In other words, it was confirmation for me that I was, in part at least, an intelligence target… So, all taken together, at a time when I was vulnerable (ill and in bed-ridden), I may have been subject to some kind of counter-intelligence game played by Smith and her spook friends (who may include the NIA; my ex-NIA friend says she doesn’t know Smith). Its objective may have been to smear me within the movement, and in this it appears successful[.] :-P Either way, it did not recur, I gave a full explanation to my ZACF coms, and I believe I have proven what side I am on by my continual production of articles for anarkismo, work o n the anarchist books Cartography of Revolutionary Anarchism, Global Fire, Springwaters of Anarchy, and The People Armed, plus a new series of pamphlets I am working on: On the Waterfront, Critical Mass, Uruguayan Anarchism Armed, etc. Hardly the output of a hostile party, I hope you’ll agree?”

There seems little way around the conclusion that Schmidt used anterograde amnesia as part of an elaborate lie to deny involvement with Black Battlefront at the time, and claims that Smith/Vinlander (the sockpuppet account(s) he claims to have invented on Facebook, but who he also claims to have met at a bar) may have been in cahoots with a close friend of his who came out as a spy. Hence, in his public statement, he insists, “[I] could not risk my penetration of the ‘National-Anarchist Movement’ becoming known in activist circles in case other [South African National Intelligence] agents got wind of it and used the information for their own ends.” However, Schmidt’s affiliations with the “National-Anarchist Movement” did continue on Stormfront, and again percolated up to his public articles.

While Schmidt navigated what he described to us as a “whisper campaign,” Le Sueur was so active online that Keith Preston, who runs the pan-secessionist blog, Attack the System, even quoted him in his book of the same name, calling him “one of my readers.” Preston is a former-anarchist who believes that if everyone, left and right wing (inclusive of fascists and neo-Confederates), supports secession, humanity will break apart the greater evil of the federal government, and create metropolitan regions dominated by the Nietzschean ubermensch. Specifically, Preston quotes Le Sueur’s rebuttal of antifascist writer Matthew Lyons’s brilliant critique of pan-secessionism:

The questions raised by [Lyons] appear to reduce to one single fear: the question of power; that decentralizing power allows for no comprehensive/universalist (totalitarian?) enforcement of social norms. And this is clearly what the author wishes: some universal enforcement mechanism that can punish communities for their ‘deviant’ social choices. Surely that is true authoritarianism, writ large, compared with the possibility of some communities choosing authoritarianism writ small as a much lesser threat to civilization?

These communities would include, for Preston, Russia’s fascist National Bolshevik groups and Christian Identity fascist groups, which provides, in Lyons’s words, “a recipe for warlordism.”

Le Sueur and Preston embraced national-anarchist formations, along with other red-brown secessionist assemblages, as an opportunity to join together in dismantling the perceived greater threat of the US federal government and Zionist imperialism. Not only was Michael Schmidt quoted by Keith Preston as François Le Sueur, but he was quoted as a critic of antifascist analysis, indicating to us that if he was doing “research” with his fascist personality, it was in service of and not to infiltrate the pan-secessionist and national-anarchist tendencies. Schmidt’s own appreciation for Keith Preston’s Attack the System blog was laid bare in an article written by Preston and shared on February 27, 2011, by the Le Sueur Facebook page called, “Am I a Fascist?” Preston and Le Sueur were also “friends” on Facebook.

In November 2010, while purportedly in the throes of amnesia, Le Sueur proclaimed he was “working on a Black Battlefront position statement on the reasoning behind the establishment of a white anarchist organization,” the exact term Schmidt publicly used to describe the ZACF in 2008. At the same time, KarelianBlue outlined his plans for a Boerestaat on another post to Stormfront:

[first, to] promote the secessionist Cape Party… then to expand the concept of the ‘Cape’ upwards into Namibia… and lastly to radicalise it by decentralising power in the Cape/Namibia… with the finance-capitalist elements removed and returned to popular control.

The idea was that white supremacists would enter into the secessionist party to mobilize control over a larger territory, effecting a recolonization process of white nationalism under the condition that they would later decentralize and socialize the means of production. On his own post, KarelianBlue commented that a new entry in his Black Battlefront blog was available.

The transition to using Black Battlefront as an organ occurred in direct relation to Schmidt’s leaving the ZACF during a debate over the inclusion of feminism and the recruitment of people of color. Since he was losing authority over the ZACF (which grew increasingly open to people of color after Schmidt’s departure), he designed his own clandestine group to carry out the interests of a “white ‘national’ organization” by promoting a white separatist party. According to one of the most prominent advocates of national-anarchism, Troy Southgate, the appropriate strategy for so-called “national-anarchists” to gain power is called entryism:

Entryism is the name given to the process of entering or infiltrating bona fide organisations, institutions and political parties with the intention of either gaining control of them for our own ends, misdirecting or disrupting them for our own purposes or converting sections of their memberships to our cause.

It would appear that KarelianBlue’s plan to promote the Cape Party matched this strategy perfectly.

Schmidt’s desire to promote the aims of a “proper Boerestaat,” which he admitted to us, combined with his testament to his own Boer/Afrikaner identity in his reflections on Terre’Blanche, prove that, after publishing Black Flame, voting for the FF+, and leaving the ZACF, he began to reissue his concerted effort to push for a “white anarchist organization” more independently. He had created a group where he could explicitly discuss his desired themes of racialized “cultural differences” and advocate for a separate, white anarchist organization. Moreover, through Black Battlefront, he would have an opportunity to link up with national-anarchists and pan-secessionists around the world. As this process continued, his open promotion of the Cape Party and FF+-style secessionism would turn toward increasingly-obvious displays of neo-fascism.

Chapter Four

Lightning bolt used by the British Union of Fascists, posted by one of Michael Schmidt’s sock puppet accounts on Facebook.

Michael Schmidt’s Complicated Relationship with National-Anarchism and Pan-Secessionism

According to a source, after being exposed for his Stormfront posts in 2011, Michael Schmidt entered a phase of presenting himself a journalist with an interest in anarchism, but not an anarchist. In the book he was working on during this period, Drinking with Ghosts, he describes anarchists in passing as one of the many extreme groups of people with whom he has made friends during his journalistic career: “My craft over this period was one hell of a rollercoaster ride; along the way I made friends with arms dealers, anarchist revolutionaries, Special Forces operatives, community activists and intelligence agents” (2014, BestRed). While he continued to write for Anarkismo and other anarchist publications, Schmidt’s presence in anarchist circles would make for increasingly messy reconciliation with the other social circles in which he was allegedly rubbing shoulders.

He began to dial down his “KarelianBlue” Stormfront profile, likely as a result of the investigation into his activities by the ZACF. At the same time, however, his “Le Sueur” profile escalated his Facebook engagement. He posted about USSR gulags, a Flemish separatist party, British crimes in Ireland, and an article from an anarchist platformist site. Among cryptic statements like, “The good dream of what the bad do,” and edgy articles from the controversial Russian ex-patriot news site, The eXile (which boasts neo-fascist, Eduard Limonov, among its columnists), one finds Le Sueur posting flags with the British Union of Fascists’ lightning bolt, as well as the crypto-fascist neo-folk band Sol Invictus, boasting known ties to neo-fascism. A hot rod magazine (a hobby that he told us about) is posted along with Nazi paraphernalia like a Sturmfuhrer T-Shirt, Anarkismo articles, as well as an article from the neo-fascist site, The Occidental Observer.

Black Battlefront also saw a great deal of activity in 2011, including some passages copy-and-pasted from Schmidt’s Stormfront account listing the “propagators of [white] guilt” and “debasers of Aryan culture.” The administrator of Black Battlefront’s posts, Strandwolf, maintains the line about the Cape Party already expressed in Stormfront by KarelianBlue:

And in dispossessing our enemies, what then should our territory be?… We can rather lay claim to the western portions of the Old Cape and its hinterland, settled from 1652… Surrendering the gold- and coal-mining, industrial and financial hinterland plus the eastern ports, farms and plantations to majority-black South Africa would nevertheless leave us with a coherent territory, predominantly Afrikaans-speaking, with a white and coloured majority[.]

Strandwolf continued: