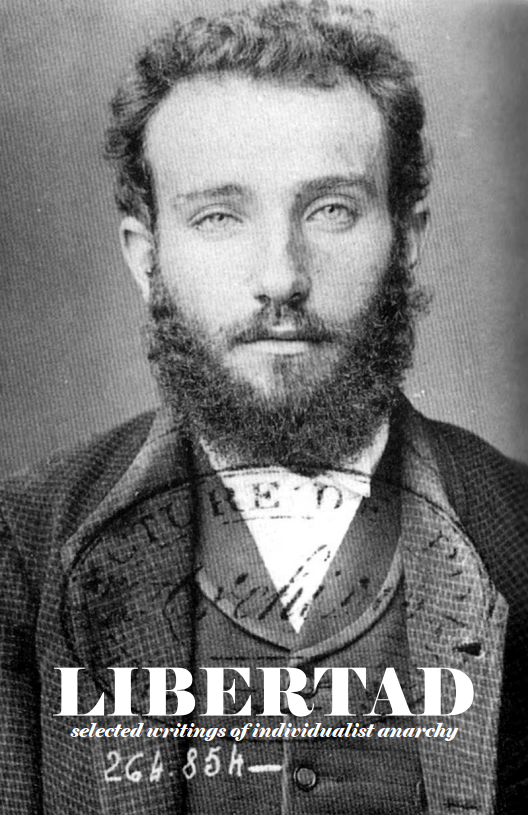

Albert Libertad

Libertad

Selected Writings of Individualist Anarchy

Freedom

Many think that it is a simple dispute over words that makes some declare themselves libertarians and others anarchist. I have an entirely different opinion.

I am an anarchist and I hold to the label not for the sake of a vain garnishing of words, but because it means a philosophy, a different method than that of the libertarian.

The libertarian, as the word indicates, is an adorer of liberty. For him, it is the beginning and end of all things. To become a cult of liberty, to write its name on all the walls, to erect statues illuminating the world, to talk about it in season and out, to declare oneself free of hereditary determinism when its atavistic and encompassing movements make you a slave...this is the achievement of the libertarian.

The anarchist, referring simply to etymology, is against authority. That’s exact. He doesn’t make liberty the causality but rather the finality of the evolution of his Self. He doesn’t say, even when it concerns merest of his acts, “I am free,” but “I want to be free.” For him, freedom is not an entity, a quality, something that one has or doesn’t have, but is a result that he obtains to the degree that he obtains power.

He doesn’t make freedom into a right that existed before him, before human beings, but a science that he acquires, that humans acquire, day after day, to free themselves of ignorance, abolishing the shackles of tyranny and property.

Man is not free to act or not to act, by his will alone. He learns to do or not to do when he has exercised his judgement, enlightened his ignorance, or destroyed the obstacles that stand in his way. So if we take the position of a libertarian, without musical knowledge in front of his piano, is he free to play? NO! He won’t have this freedom until he has learned music and to play the instrument. This is what the anarchists say. He also struggles against the authority that prevents him from developing his musical aptitudes — when he has them — or he who withholds the pianos. To have the freedom to play, he has to have the power to know and the power to have a piano at his disposition. Freedom is a force that one must know how to develop within the individual; no one can grant it.

When the Republic takes its famous slogan: “Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite,” does it make us free, equal or brothers? She tells us “You are free” — these are vain words since we do not have the power to be free. And why don’t we have this power? Principally because we do not know how to acquire the proper knowledge. We take the mirage for reality.

We always await the freedom of a State, of a Redeemer, of a Revolution, we never work to develop it within each individual. What is the magic wand that transforms the current generation born of centuries of servitude and resignation into a generation of human beings deserving of freedom, because they are strong enough to conquer it?

This transformation will come from the awareness that men will have of not having freedom of consciousness, that freedom is not in them, that they don’t have the right to be free, that they are not all born free and equal...and that it is nevertheless impossible to have happiness without freedom. The day that they have this consciousness they will stop at nothing to obtain freedom. This is why anarchists struggle with such strength against the libertarian current that makes one take the shadow for substance.

To obtain this power, it is necessary for us to struggle against two currents that threaten the conquest of our liberty: it is necessary to defend it against others and against oneself, against external and internal forces.

To go towards freedom, it becomes necessary to develop our individuality. When I say: to go towards freedom, I mean for each of us to go toward the most complete development of our Self. We are not therefore free to take any which road, it is necessary to force ourselves to take the correct path. We are not free to yield to excessive and lawless desires, we are obliged to satisfy them. We are not free to put ourselves in a state of inebriation making our personality lose the use of its will, placing us at the mercy of anything; let’s say rather that we endure the tyranny of a passion that misery of luxury has given us. True freedom would consist of an act of authority upon this habit, to liberate oneself from its tyranny and its corollaries.

I said, an act of authority, because I don’t have the passion of liberty considered a priori. I am not a libertarian. If I want to acquire liberty, I don’t adore it. I don’t amuse myself refusing the act of authority that will make me overcome the adversary that attacks me, nor do I refuse the act of authority that will make me attack the adversary. I know that every act of force is an act of authority. I would like to never have to use force, authority against other men, but I live in the 20th century and I am not free from the direction of my movements to acquire liberty.

So, I consider the Revolution as an act of authority of some against others, individual revolt as an act of authority of some against others. And therefore I find these means logical, but I want to exactly determine the intention. I find them logical and I am ready to cooperate if these acts of temporary authority have the removing of a stable authority and giving more freedom as their goal. I find them illogical and I thwart them if their goal isn’t removing an authority. By these acts, authority gains power: she hasn’t done anything but change name, even that which one has chosen for the occasion of its modification.

Libertarians make a dogma of liberty; anarchists make it an end. Libertarians think that man is born free and that society makes him a slave. Anarchists realize that man is born into the most complete of subordinations, the greatest of servitudes and that civilization leads him to the path of liberty.

That which the anarchists reproach is the association of men-society — which is obstructing the road after having guided our first steps. Society delivers hunger, malignant fever, ferocious beasts — evidently not in all cases, but generally — but she makes humanity prey to misery, overwork, and governments. She puts humanity between a rock and a hard place. She makes the child forget the authority of nature to place him under the authority of men.

The anarchist intervenes. He does not ask for liberty as a good that one has taken from him, but as a good that one prevents him from acquiring. He observes the present society and he declares that it is a bad instrument, a bad way to call individuals to their complete development.

The anarchist sees society surround men with a lattice of laws, a net of rules, and an atmosphere of morality and prejudices without doing anything to bring them out of the night of ignorance. He doesn’t have the libertarian religion, liberal one could say, but more and more he wants liberty for himself like he wants pure air for his lungs. He decides then to work by all means to tear apart the threads of the lattice, the stitches of the net and endeavors to open up free thought.

The anarchist’s desire is to be able to exercise his faculties with the greatest possible intensity. The more he improves himself, the more experience he takes in; the more he destroys obstacles, as much intellectual and moral as material, the more he takes an open field; the more he allows his individuality to expand, the more he becomes free to evolve and the more he proceeds towards the realization of his desire.

But I won’t allow myself to get carried away and I’ll return more precisely to the subject.

The libertarian who doesn’t have the power to carry through an explanation, a critique which he recognizes as well founded or that he doesn’t even want to discuss, he responds “I am free to act like this.” The anarchist says: “I think that I am right to act like this but come on.” And if the critique made is about a passion which he doesn’t have the strength to free himself from, he will add: “I am under the slavery of this atavism and this habit.” This simple declaration won’t be without cost. It will carry its own force, maybe for the individual attacked, but surely for the individual that made it, and for those who are less attacked by the passion in question.

The anarchist is not mistaken about the domain gained. He does not say “I am free to marry my daughter if that pleases me — I have the right to wear a high style hat if it suits me” because he knows that this liberty, this right, is a tribute paid to the morality of the milieu, to the conventions of the world; they are imposed by the outside against all desires, against all internal determinism of the individual.

The anarchist acts thus not due to modesty, or the spirit of contradiction, but because he holds a conception which is completely different from that of the libertarian. He doesn’t believe in innate liberty, but in liberty that is acquired. And because he knows that he doesn’t possess all liberties, he has a greater will to acquire the power of liberty.

Words do not have a power in themselves. They have a meaning that one must know well, to state precisely in order to allow oneself to be taken by their magic. The great Revolution has made a fool of us with its slogan: “Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite.” The liberals have sung us above all the tune of their “laisser-faire” with the refrain of the freedom of work. Libertarians delude themselves with a belief in a pre-established liberty and they make critiques in its honor... Anarchists should not want the word but the thing. They are against authority, government, economic, religious, and moral power, knowing the more authority is diminished the more liberty is increased.

It is a relation between the power of the group and the power of the individual. The more the first term of this relation is diminished, the more authority is diminished, the more liberty is increased.

What does the anarchist want? To reach a state in which these two powers are balanced, where the individual has real freedom of movement without ever hindering the liberty of movement of another. The anarchist does not want to reverse the relation so that his freedom is made of the slavery of others, because he knows that authority is bad in itself, as much for he who submits to it as for he who gives it.

To truly know freedom, one must develop the human being until one makes sure that no authority has the possibility of existing.

Obsession

Durand, leaving his hotel, a smile of contentment on his lips, took a small step back, to read a tiny poster:

While we perish in the street,

the bourgeois has palaces to live in

Death to the bourgeois!

Long Live Anarchy!

Then, he sneered, and yelled to the concierge “You will take these idiocies off of the door?” And his calm smile came back when he noticed, glorious in their incapacity, two officers on the beat. But he stopped at the same time as them, red flyers stuck out on the stark white of the wall:

Cops are the bulldogs of the bourgeois

Death to cops!

Long Live Anarchy!

The cops used their nails to scratch off the posters and Durant left anxious. While at the corner of the avenue, he heard the sound of bugles and drums and from afar two battalions appeared. He felt protected and breathed a sigh of relief.

As a troupe passed in front of him, he discovered, at that moment, like a flight of butterflies, a multitude of squares of paper floating in the air; indifferently, he read:

The army is the school of crime

Long Live Anarchy!

Some of the papers fell on the soldiers, others covered them; his obsession resumed, he felt crushed by the light butterflies.

When he sat down in his usual place to have a beer or the usual aperitif, on the table laid another flyer:

Go on, gorge yourself, the day will come when hate will turn us into cannibals.

Long Live Anarchy!

He sneered, but this time he didn’t fill up saucer after saucer. Getting up, he headed quickly toward the corner of X street, where the exploiters asked for workers, and mechanically searched for the propaganda poster, he discovered it and read:

The exploiter Thing or Machine asks for your sons to degrade them,

Your daughters to rape them, you and your wives

To exploit you

Watch out Parisians.

Long Live Anarchy!

He shook his head and headed towards his office. He read on a plaque: Durand and Cie, Society in a capitol of two million, but, below, the exasperating critique said its piece:

Capital is the product of work

stolen and accumulated by the idle.

Long Live Anarchy!

He tore himself away quickly. He took care of some business, and to distract himself, thought of seeing his mistress. On his way, he bought a bouquet of flowers to offer her.

She smiled, seeing amidst the flowers what appeared to be a love letter:

“Some verses, now?” says she.

Prostitution is the outlet of too many bourgeois.

One turns the son of the poor man into a slave and his daughter into a courtesan.

Long Live Anarchy!

She threw the bouquet in his face and sent him away.

Ashamed and tired, he returned home, the door had once again taken on its usual appearance.

Now, upon entering the living room, his wife said to him: “Look at this vase that I just bought, what an occasion.” He took it, turned it around, and turned it around again; a piece of paper fell out:

The luxury of the bourgeois is paid for by the blood of the poor man.

Long Live Anarchy!

This “Long Live Anarchy!” and its harsh claims, all this hovered around him, and that very evening, he didn’t go to see his wife, in fear of finding, in a discreet and camouflaged place, a flyer where he would have read:

Marriage is legal prostitution.

Long Live Anarchy!

The Joy of Life

Wearied by the struggle of life, how many close their eyes, fold their arms, stop short, powerless and discouraged. How many, and they among the best, abandon life as unworthy of continuance. With the assistance of some fashionable theories, and of a prevalent neurasthenia, some men have come to regard death as the supreme liberation.

To those who hold this view, society replies with the usual clichés.

It speaks of the “moral” purpose of life; argues that one has no right to kill himself, that “moral” sorrows must be borne courageously, that a man has duties, that the suicide is a coward or an “egoist,” etc. etc. All of these phrases are religious in tone; and none of them are of genuine significance in rational discussion.

What after all is suicide?

Suicide is the final act in a series of actions that we all tend to carry out, which arise from our reaction against our environment, or from that environment’s reaction against us.

Every day we commit suicide partially. I commit suicide when I consent to inhabit a dwelling where the sun never shines, a room where the ventilation is so inadequate that I feel like I am suffocated when I wake up.

I commit suicide when I spend hours on work that absorbs an amount of energy which I am not able to recapture, or when I engage in activity which I know to be useless.

I commit suicide whenever I enter into the barracks to obey men and laws that oppress me.

I commit suicide whenever I grant the right to govern me for four years to another individual through the act of voting.

I commit suicide when I ask a magistrate or a priest for permission to love.

I commit suicide when I do not reclaim my liberty as a lover, as soon as the time of love is past.

Complete suicide is nothing but the final act of total inability to react against the environment.

These acts, which I have called partial suicides, are no less truly suicidal. It is because I lack the strength to react against society that I inhabit a place without sun and air, that I do not eat in accordance with my hunger or my taste, that I am a soldier or a voter, that I subject my love to laws or compulsion.

Workers daily commit mental suicide by leaving the mind inactive, by not letting it live, as they kill within themselves their enjoyment of the arts of painting, sculpture, music, which offer some relief from the cacophony which surrounds them.

There can be no question of right or duty, of cowardice or of courage in relation to suicide; it is purely a material problem, of power or lack of power. One hears it said, “Suicide is a human right when it constitutes a necessity...” Or again, “one cannot take the right of life and death away from the proletariat.”

Right? Necessity?

Shall one debate his right to breathe poorly, i.e. to kill most of the health-giving molecules to the advantage of the unhealthy ones? His right not to eat in accordance with his hunger, i.e. to kill his stomach? His right to obey, i.e. to murder his will? His right to love the woman designated by the law or chosen by the desire of one period forever, i.e. to slay all the desires of days to come?

Or if we substitute the word “necessity” for the word “right” in these phrases, do we thereby make them the more logical?

I do not intend to “condemn” these partial suicides more than definitive suicides; but it seems to me pathetically comical to describe as right or necessity this surrender of the weak before the strong — and a surrender made without having tried everything. Such expressions are merely excuses one clings to.

All suicides are imbecilities, total suicide more than the others, since it is possible to bring oneself out of the partial forms.

It would seem that at the moment of the departure of the individual, all energy might be focused on a single point of reaction against the environment, even with a thousand to one chance of failure in the effort. This seems still more necessary and natural in view of the fact that one leaves those one loves behind. For this part of one’s self, this portion of the energy of which one consists, cannot one engage in a gigantic struggle, however unequal the combat, capable of shaking up the colossal Authority?

Many die, declaring themselves to be victims of society; do they not realize that, since the same cause produces the same effects, their comrades, those they love, could die as victims of the same state of things? Won’t a desire then come to them to transform their vital force into energy, into power, so as to burn the pile rather than to separate its elements?

Once one has overcome the fear of death, of the complete dissolution of the human form, one can engage in the struggle with that much more strength. Some will respond to us, “We have a horror of bloodshed. We do not wish to attack this society, made up of men who seem to us to be both unaware and irresponsible.”

The first objection does not hold. Does the struggle only take a violent form? Is it not multiple, diverse? And all the individuals who understand its usefulness, can they not take part each according to his own temperament?

The second is too inexact. Such words as “society,” “knowledge,” “responsibility” are too often repeated and too little explained.

The barrier that obstructs the road, the biting serpent, the tuberculosis microbe are unaware and without responsibility, yet we defend ourselves against them. Still more irresponsible (in the relative sense) are the cornfields which we reap, the ox that we kill, the beehive that we rob. Nevertheless we attack them all.

I know nothing of “responsible” nor of “irresponsible.” I see the causes of my suffering, of the cramping of my personality; and my efforts are bent to suppress or to conquer them by every possible means.

According to my power of resistance I assimilate or I reject, I am assimilated or rejected. That is all.

Even stranger objections are advanced, in a form neurotically scientific: “Study astronomy, and you will realize the negligible duration of human life as compared to the infinite. Death is a transformation and not termination.”

For myself, being finite, I have no conception of the infinite; but I know that duration consists of centuries, centuries of years, years of days, days of hours, hours of minutes, etc. I know that time is made up of nothing but the accumulation of seconds, that great immensity formed from the in-finitely small. Short as our life may be, it has its dimensional importance from the point of view of the whole. Life, seen from my own point of view, with my own eyes, cannot be of little importance to me; and all seems to me to have had no purpose but to prepare for us — for myself and for that which surrounds me.

The stone which caresses the head when dropped from a meter above, will break it open if it falls twenty meters. Arrested on the way, seen from the point of view of the whole, it differs in no particular; but it lacks the energy which makes it a power.

I disregard all that I cannot conceive, and look primarily to myself; and a dissolution or rather a non-absorption of strength that acts to my detriment occurs in either a partial or a definitive suicide.

Death is the end of a human energy, as the dissociation of elements of a battery is the end of the electricity which it releases, as the dissolution of threads of a tissue is the end of that tissue’s strength. Death, as the end of my “I,” is more than a transformation.

There are those who say to one, “The goal of life is happiness,” and who profess to be unable to attain it. It seems to me simpler to say that life is life. Life is happiness. Happiness is life.

All the acts of life are a joy to me. Breathing pure air, I know happiness; my lungs are expanded, an impression of power makes me glow. The hour of work and that of rest afford me equal pleasure. The hour which brings the mealtime; the meal itself with its labor of mastication; the hour which follows with its interior activity — all give me joy of varying sorts.

Shall I evoke the delicious attention of love, the sense of power in the sexual encounter, the succeeding hours of voluptuous relaxation?

Shall I speak of the joy of the eyes, of hearing, of odor, of touching, of all the senses, of the delights of conversation and of thought? Life is a happiness.

Life has not a goal. It is. Why wish for a goal, a beginning, an end?

Let us recapitulate. Whenever, hurled on the stones by an earthquake, avid for air, we bow our head against the rock; whenever seized by the regimentation of society as it is, avid for the ideal (to make this vague term exact: avid for the integral development of one’s self and one’s loved ones) we arrest our life, we obey, not a necessity nor a right, but as obsession of force, of the obstacle. We do no voluntary act, as the partisans of death profess; we obey the power of the environment which crushes, and we depart precisely at the hour the weight is too heavy for our shoulders.

“Then,” they say, “we do not go except at our hour — and our hour is now.” Yes. But since, resigned, they envisage their defeat in advance; since they have not developed their tissues with a view to resistance; they have not made due effort to react against the regimentation of the environment. Unaware of their own beauty, of their own force, they add to the objectives of the obstacle all the subjective weight of their own acceptance.

Like those resigned to partial suicides, they surrender themselves to the great suicide. They are devoured by an environment avid for their flesh, eager to crush all energy that appears.

Their error lies in the belief that the dissolution is by their own will, that they choose their hour, while actually they die crushed inevitably by the wickedness of some and by the [...][1] of others.

In a locality by the maleficient of typhus, of tuberculosis, I do not think of absenting myself to avoid the malady; rather, I proceed immediately to disseminate disinfectants, without any fear of killing millions of microbes.

In present society, made foul by the conventional defecations of property, of patriotism, of religion, of family, of ignorance, crushed by the power of government and the inertia of the governed; I wish not to disappear, but to throw upon the scene the light of truth, to provide a disinfectant, to do it by any means at my command.

Even with death approaching, I shall have still the desire to chair my body by means of phenol or acid, for the sake of humanity’s health.

And if I am destroyed in this effort, I shall not be totally effaced. I shall have reacted against the environment, I shall have lived briefly but intensely; I shall perhaps have opened a breach for the passage of energies similar to my own.

No, it is not life that is bad, but the conditions in which we live. Therefore we shall address ourselves not to life, but to these conditions: let us change them.

One must live, one must desire to live still more abundantly. Let us accept not even the partial suicides.

Let us be eager to know all experiences, all happiness, all sensations. Let us not be resigned to any diminution of our “me.” Let us be champions of life, so that desires may arise out of our turpitude and weakness; let us assimilate the earth to our own concept of beauty.

Thus may our wishes be united, magnificently; and at the last we shall know the Joy of Life in the absolute.

Let us love life.

Germinal, at the Wall of the Fédérés

Near their tomb,[2] in the middle of the gaudy wreaths and bouquets showily brough there, in the grass, in black letters on a red background, someone wrote one word: Germinal.

This person knew how to give the correct tone to this anniversary.

Germinal! This wasn’t a banal remembrance of the dead, this was a call to the living; it wasn’t the pointless glorification of the past, it was a call to the future.

On the tomb of these men who died for freedom, this word called their children to liberating rebellion.

The wreaths, the bouquets, the speeches, were vain palliatives. Germinal was the still living fight, rising up, terrible, calling the workers, the rebels, to the imminent harvests.

We Go On

We don’t have faith, we have absolutely no confidence in our success: we are certain that we have neglected nothing, that we have made all our efforts in order to be on the correct road.

We are not certain that we will succeed: we are not certain that we are right.

We don’t know, it is not possible for us to know if success will be at the end of our efforts, if it will be the reward; we try to act so that, logically, we should arrive at the result that interests us.

Those that envision the goal from the first steps, those that want the certitude of reaching it before walking, never arrive.

Whatever the task undertaken may be, if the completion is near, who can say they’ve seen the end? Who can say: I will plentifully reap that which I sow; I will live in this house which I build, I will eat the fruits of the tree which I plant?

And therefore, one throws the wheat on the ground, one arranges the stones one by one, one surrounds the fruit-tree with care.

Because one does not know for certain, for sure, for whom, how, when the result will be, will one neglect one’s efforts for that which will be possibly good? Will one throw the grain on the hard rock or mix it with the tares? Will one arrange the stones without the square and the plumb-line? Will one put the seedling at the crossroads of the four winds?

The joy of the result is already in the joy of effort. He who makes the first steps in a direction that he has every reason to believe good, already arrives at the goal, that’s to say, at the reward of this labor.

We don’t need to know if we will succeed, if men will come to live in a great enough harmony to assure the complete development of their individuality, we have to do the deeds for that which may be, to go in the direction that both our reason and our experience aptly decide.

We don’t say: “Men are born good, they should therefore harmonize their relations.” We say “Logically, it will be in the interest of men to obtain with the least effort the greatest sum of well being; not from the point of view of eliminating effort, but of always using it for betterment. It is thus necessary to show them where our interest is. The understanding between individuals is the best means to come to assure human happiness. Let’s try to make him understand it.”

The idea of a meteor collision with the earth, a collapse of the sun, a great fire being able to interrupt our show or our experience, cannot hinder all of us from beginning. Likewise, the misunderstanding of our ideas and practice by the majority of men, be it due to cretinism or perversity, would not be a reason to stop us from thinking and critiquing.

All work begun is on its way to completion, whatever the resistance of the attacked group may be. It is not a question of speculating about the magnificence or the proximity of the goal to reach, but rather of convincing oneself with a constant critique with which one proceeds handsomely, and doesn’t get lost in digressions.

We go on with ardor, with strength, with pleasure in such a direction, determined because we are aware of having done everything and of being ready to do anything so that this is in the right direction. We bring to the study the greatest care, the greatest attention, and we give the greatest energy to action. While we direct our activity in a given direction, it’s not a matter of telling ourselves: “Work is hard; statist society is solidly organized; the foolishness of men is considerable,” it would be better to show us that we are heading in the wrong direction. If one reached it, we would use the same force, in another direction, without faltering. Because we don’t have faith in such a goal, the illusion of such a paradise, but in the certitude of using our effort in the best direction.

It would not be worthwhile to concern ourselves with an immediate, tangible result if it obstructs, diverts our exact path. The bait of reforms attracting the mass of men would not be able to hinder us.

To accelerate our march, we don’t need mirages showing us the closest end, within our hand’s reach. It will be enough for us to know that we go on and that, if we sometimes stamp around the same spot, we do not go astray.

The mirage calls us to the right and to the left, diverts us, and if one succeeds in returning to the correct road, this is weakened and diminished by lost illusion. The intoxication of words and illusions resembles that of alcohol, it can throw the multitudes into an impassioned movement, towards the closest goal: but the sobered multitudes pause.

They pause discouraged by the emptiness of the empty result. The perseverance of courage is not in the act of arriving, but in the certitude of being right.

We don’t need a sign-post to show us that we have traveled a third, a fourth, a hundredth of the way; nothing measures the quantity of our effort and such markings have no relation to our effort as a whole. We please ourselves to know that we give, according to our strengths and in the direction that we believe is best, all that we can give.

We believe in a constant evolution, we therefore know that there is no end. It is enough for us to always go forward, always on the correct path. And the packs may bark after us, and we may be the crazy ones, the bad ones. The majority may stand in our way. Atavism, heredity may want to impose its ineluctable laws. The group may defend itself harshly. Though the end may be far, very far, these things do not concern us.

We go on... employing all means, in turn persuasive and violent. We are ready to come together with anyone and with everyone for the attainment of universal happiness and for the normal development of the unique.

We go on... Each effort brings joy in itself and every day sees its stopping place, even if advancement is slight.

We go on... We are not sure to arrive; we are mindful that we have done everything and to be ready to do anything to be right, and hence to arrive.

And it is this that makes us the strongest...that we are never weary.

We go on…

To the Resigned

I hate the resigned!

I hate the resigned, like I hate the filthy, like I hate layabouts!

I hate resignation! I hate filthiness, I hate inaction.

I feel for the sick man bent under some malignant fever; I hate the imaginary sick man that a little bit of will would set on his feet.

I feel for the man in chains, surrounded by guardians, crushed under the weight of irons of the many.

I hate soldiers who are bent by the weight of braids and three stars; the workers who are bent under the weight of capital.

I love the man who says what he feels wherever he is; I hate the voter seeking the perpetual conquest by the majority.

I love the savant crushed under the weight of scientific research; I hate the individual who bends his body under the weight of an unknown power, of some “X,” of a God.

I hate, I say, all those who, surrendering to others through fear or resignation a part of their power as men, not only keep their heads down, but make me, and those I love, keep our heads down too, through the weight of their frightful collaboration or their idiotic inertia.

I hate them; yes I hate them, because me, I feel it. I don’t bow before the officer’s braid, the mayor’s sash, the gold of the capitalist; morality or religion. For a long time I have known that all of these things are just baubles that we can break like glass...I bend beneath the weight of the resignation of others. O how I hate resignation!

I love life.

I want to live, not in a petty way like those who only satisfy a part of their muscles, their nerves, but in a big way, satisfying facial muscles as well as calves, my back as well as my brain.

I don’t want to trade a portion of now for a fictive portion of tomorrow. I don’t want to surrender anything of the present for the wind of the future.

I don’t want to bend anything of mine under the words fatherland, God, honor. I too well know the emptiness of these words, these religious and secular ghosts.

I laugh at retirement, at paradises the hope for which holds the resigned, religions, and capital.

I laugh at those who, saving for their old age, deprive themselves in their youth; those who, in order to eat at sixty, fast at twenty.

I want to eat while I have strong teeth to tear and crush healthy meats and succulent fruits. When my stomach juices digest without problem I want to drink my fill of refreshing and tonic drinks.

I want to love women, or a woman, depending on our common desire, and I don’t want to resign myself to the family, law the Code; nothing has any rights over our bodies. You want, I want. Let us laugh at the family, the law, the ancient form of resignation.

But this isn’t all. I want, since I have eyes, ears, and other senses, more than just to drink, to eat, to enjoy sexual love: I want to experience joy in other forms. I want to see beautiful sculptures and painting, admire Rodin or Manet.

I want to hear the best opera companies play Beethoven or Wagner. I want to know the classics at the Comedie Française, page through the literary and artistic baggage left by men of the past to men of the present, or even better, page through the now and forever unfinished oeuvre of humanity.

I want joy for myself, for my chosen companion, for my friends. I want a home where my eyes can agreeably rest when my work is done.

For I want the joy of labor, too; that healthy joy, that strong joy. I want my arms to handle the plane, the hammer, the spade and the scythe.

Let the muscles develop, the thoracic cage become larger with powerful, useful and reasoned movements.

I want to be useful, I want us to be useful. I want to be useful to my neighbor and for my neighbor to be useful to me. I desire that we labor much, for I am insatiable for joy. And it is because I want to enjoy myself that I am not resigned.

Yes, yes I want to produce, but I want to enjoy myself. I want to knead the dough, but eat better bread; to work at the grape harvest, but drink better wine; build a house, but live in better apartments; make furniture, but possess the useful, see the beautiful; I want to make theatres, but big enough to house me and mine.

I want to cooperate in producing, but I also want to cooperate in consuming.

Some dream of producing for others to whom they will leave, oh the irony of it, the best of their efforts. As for me, I want, freely united with others, to produce but also to consume.

You resigned, look: I spit on your idols. I spit on God, the Fatherland; I spit on Christ, I spit on the flag, I spit on capital and the golden calf; I spit on laws and Codes, on the symbols of religion; they are baubles, I could care less about them, I laugh at them...

Only through you do they mean anything to me; leave them behind and they’ll break into pieces.

You are thus a force, you resigned, one of those forces that don’t know they are one, but who are nevertheless a force, and I can’t spit on you, I can only hate you...or love you.

Above all my desire is that of seeing you shaking off your resignation in a terrible awakening of life.

There is no future paradise, there is no future; there is only the present.

Let us live!

Live! Resignation is death.

Revolt is life.

May Day

The national and international holiday of the organized proletariat. The Bastille Day of the unionized working class, the replay of the holiday of the Bistros.

The tragi-comic anniversary of something that will be taken away...

May Day 1905: Prologue

In the archiepiscopal church the grand ceremony takes place: the high priests, who have been delegated to other places, are absent.

The tribune is filled. The office is invaded. The strangest looking faces appear there. An assessor, delegate and secretary of I-don’t-know-what, who has decorated his breast with a large tie, with his decoration and his lit up mug, set the appropriate tone.

Appearing in a curious parade, all alone come the eternal bit players and the future stars. In the wings we can imagine the presence of influential directors falsifying the system.

Alcohol overflows in smelly burps from almost every mouth.

A few ordinary workers, a hundred at most, have come in a spirit of combativeness, or though obligation. There are a few who are sincere, thinking they are working for their emancipation, and who are sickened and disillusioned by the drunken events around them.

A bizarre salad where the words “Organized proletariat,” “Workers’ demands,” “Eight hour day,” dance about. “All arise in 1906,” “The Bosses,” “The Exploiters,” “The Exploited,” “My Corporation,” “Delegates,” “The Union of...,” etc. are seasoned before us.

One has the impression of listening to a constantly wound up phonograph, but whose worn out notches allow only a few words to escape.

Any attempt at serious debate is impossible. We are in the hall not to learn but — it appears — to impress the bosses.

We must all be in agreement, all friends, all brothers, so that the press can’t say there was any disagreement.

We are working for the gallery.

Should the press say tomorrow how many drunks there were at the tribune? Should it speak of the exceptional receipts at the bistros within a kilometer of the Labor Exchange? Should it count the number of men who came home at night with their bellies full of alcohol and their pockets empty?

Across from the Labor Exchange a group decorated in red is drinking… I pass by... a man detaches himself and gives me two sous “for good luck,” taking me for a poor devil and so as to get a laugh. Pieces of silver fall to the ground, rolling from his pockets.

Working class emancipation through union organization!

But let’s go back... Nevertheless, a few notes are interesting and throw a bit of light on this milieu. Two navvies speak with a simplicity, a great sobriety and please quite a few; a man who keeps his hat on and at whom the union crowd shouts: “Your hat!” says some true things; Gabrielle Petit, with her raw eloquence, maintaining her impulsive character, breaks up the disgusting monotony of the dogmatic ritual.

After an incident where we — the best as well as the worst — take on grotesque forms in the rapidity of our gestures, where can be felt the irritation of disgust and fatigue of some, of alcohol among others, afterwards, we must sing.

Sing the ditty that fits the circumstance.

It’s a family from Bercy, former owner of a special cabaret for snobs and the neurotic near Clichy that has made up the words and the music.

It’s not so much the ignorant crowd that wants the song, it’s the leaders: the director Pouget forgets himself so much as to leave the wings. One has to sing to the people. And the woman, with a certain courage, incidentally, not caring about our more or less correct shouting, waits for the right moment to emit her note. One must live, after all.

We do all we can so as not to sing, fully understanding how ridiculous this graceless song is between these four walls, giving this struggle a soppy character... But in France everything ends in a song. And we stop, vanquished not by the force of these men, whose cunning masters, slipping slander in, order them to respect us, but rather by their thoughtlessness, their blindness, by the atmosphere of alcohol that we can no longer breathe.

And here is the final scene.

Lepine has given his police clique the order to hold itself back... To let this religious crowd enjoy its icon, its idol, its flag. The doorways are clear; the policemen are behind the metro worksites, waiting for the opportune moment.

The Labor Exchange, squeezed in between two houses, in this narrow corridor, is ugly. Its base is covered in posters, its upper floors are slashed by a red band with gold lettering for 1906. A red flag with a black crepe (colors authorized by the law) recalls the tragedy of Limoges. Nothing is missing; neither the hosanna, nor the remembrance of the martyrs.

They’re going to raise the red flag at the window! The ditty was good, but the sight of the icon...that’s sublime! I look and I see once again... the scenes where to the cry of “God wills it,” brandishing the cross, the Peter the Hermits led the crowd to their death. Only here the preachers chew their tobacco and let the crowd leave on their own...In any event, the crowd’s enthusiasm is only on the surface.

A large mass heads toward the red flag, and a “Ca Ira,” broken up with hiccups, can be heard... It’s pure delirium.

The cops!

The anger calms. The honest worker reappears... and flees, followed by the policemen’s boots.

The comedy is over... They have to disperse and the crowd flees, hiccupping and stumbling, while exasperated comrades, wanting to resist orders and shoves, shout “anarchy” in the face of the police workers as a challenge.

And in the distance...the cabarets, the bars, the thousand tentacles of that terrible octopus, alcohol, suck out and breathe in all this worker blood.

It’s the holiday of the organized proletariat.

It’s May Day.

To the Electoral Cattle

Under the impetus of interested individuals the political committees are opening the awaited era of electoral quarrels.

As usual, they will insult each other, slander each other, fight each other.

Blows will be exchanged for the benefit of third thieves, always ready to profit from the stupidity of the crowd.

Why will you go for this?

You live with your kids in unhealthy lodgings. You eat — when you can — food adulterated by the greed of traffickers. Exposed to the ravages of alcoholism and tuberculosis, you wear yourself out from morning to night at a job that is always imbecilic and useless and that you don’t even profit from. The next day you start over again, and so it goes till you die.

Is it then a question of changing all this?

Are they going to give you the means of realizing a flourishing existence, you and your comrades? Are you going to be able to come and go, eat, drink, breathe without constraint, love with joy, rest, enjoy scientific discoveries and their application, decreasing your efforts, increasing your well-being. Are you finally going to live without disgust or care the large life, the intense life?

No, say the politicians proposed for your suffrage. This is only a distant ideal...You must be patient...You are many, but you should also become conscious of your might so as to abandon it into the hands of your ‘saviors’ once every four years.

But what will they do in their turn?

Laws! What is the law? The oppression of the greater number by a coterie claiming to represent the majority.

In any event, error proclaimed by the majority doesn’t become true, and only the unthinking bow before a legal lie.

The truth cannot be determined by vote.

He who votes accepts to be beaten.

So why then are there laws? Because there is property.

So it is from the prejudice of property that all our miseries, all our pain, flow.

So those who suffer from it have an interest in destroying property, and so the law.

The only logical means of suppressing laws is not to make them.

Who makes laws? Parliamentary arrivistes.

On closer analysis, it is thus not a handful of rulers who crush us, but the thoughtlessness, the stupidity, of the herd of those sheep of Panurge who constitute the electoral cattle.

We will fight without cease for the conquest of “immediate happiness” by remaining partisans of the only scientific method and by proclaiming together with our abstentionist comrades:

The voter — that is the enemy!

And now, to the voting urns, cattle.

Fear

The bourgeois were frightened!!! The bourgeois felt pass over them the wind of riot, the breath of revolt, and they feared the hurricane, the storm that would unleash those with unsatisfied appetites on their too well garnished tables.

The bourgeois were frightened!!!

The bourgeois, fat and tranquil, beatific and peaceful, heard the horrifying grumble of the painful and poor digestion of the thin, the rachitic, the unsatisfied. The Bellies heard the rumblings of the Arms, who refused to bring them their daily pittance.

The bourgeois were frightened!!!

The bourgeois gathered together their piles of money, their titles; they hid in holes from the claws of the destroyers, the bourgeois stored their movable property, and they then looked around to see where to hide themselves. The big city wasn’t very safe with all those threats in the air. And the countryside wasn’t either...chateaus were being burned down there when the evening came.

The bourgeois were frightened! A fear that gripped their bellies, their stomachs, their throats, without any means of attenuating this presenting itself.

And so the bourgeois put barricades of steel and blood up in front of the workers, cemented with blood and flesh. They tried to be joyful at seeing the little infantrymen and the heavy dragoons parade before their windows. They swooned before the handsome Republican Guards and the fine cavalrymen. And still, fear invaded their being. They were frightened.

That fear seemed to have something of remorse in it. One could believe that the bourgeois felt the logic of the acts that included everyone and everything that they alone had possessed up till then.

The bourgeois were afraid that suddenly, in a great movement, the two sides of the scale that had always inclined in the direction of their desires would suddenly be balanced. They believed the moment for disgorgement had finally come. Since their lives were made of the deaths of other men they believed that on this day the lives of others would be made of their deaths.

O anguished dream! The bourgeois were frightened, really frightened!!

But the hurricane passed over their heads and Bellies and didn’t kill. The lightning rods of sabers and rifles sufficed for the few gusts that blew forgotten over society.

The worker again took up his labor. He again bent his back over the daily task. Today like yesterday, the slave prepares his master’s swill.

The hurricane has passed...the bourgeois have little by little raised their heads. They looked upon their faces convulsed with fear...and they laughed. But their laugh was a snigger; their laugh was a bark.

Since he didn’t know how to do his work himself, the hyenas and jackals were going to fall on the lion, caught in the trap of his ignorance and confidence.

The females who, in 1871, poked out the eyes of communards with their parasols, have had children. These children are now in the magistracy, in the administration, in the army. They wear the kepi or the robe, they kill by the Code, regulations, or the sword, they kill without pity.

The bourgeois were frightened!!!

They are taking revenge for having been frightened!!! Like a club, the jackhammer of justice is descending on the vanquished. The Magnauds and the Bulots, the Séré de Rivières and the Bridoisons, all of them are in agreement in striking the troublemakers.

Never have those who do not labor been overcome by such respect for those who labor. The hindrances to the freedom to work have been struck with months and month of prison. Men have been condemned until the healing of their wounds, children to reform schools, and adolescents to the slammer. Those who reason must be put down.

The bourgeois were frightened!!!

But those who must be struck the hardest are the enemies of all the bourgeois, the reactionary bourgeois and the socialist bourgeois: the anarchists.

Other men are vanquished by the weight of their own ignorance; it will still be quite a while before they free themselves from their foolishness. But the anarchists are vanquished by the ignorance and the passivity of others, so they work every day to instruct them, to make rebels of them. It is thus they who are the danger; it is they who must be struck.

The bourgeois want to avenge themselves, but they are cowards and so it is the bystanders they strike. They fear the might of anarchist logic and they know that the sophistry of their reasoning will burst like soap bubbles in the sun. They can crush us with the dead weight of the brutal force of number, but they know that we will always win in reason’s combat.

“That man had an anarchist paper in his pocket! — That one had pamphlets on sociology. — That one had needles on him.” And they strike even harder whoever dares read anything but La Croix, La Petite République, or Le Petit Journal.

Why don’t you strike the authors, the publishers of these publications? Are they untouchable, above all laws, or are you afraid of finding yourselves confronting the truth, viscous Berengers of politics?

Bourgeois, you were frightened!!!

And it was nothing but a shadow that passed across the heaven of your beatitude. But be on your guard: you will only see the storm that will swallow you up when it will be imminent. It will only be announced by tiny lightning bolts. It will surge around you and you will be no more.

Bourgeois, you experience the frisson of fear, and you are savoring the joy of revenge...but don’t be in such a hurry to celebrate. Don’t exaggerate too greatly the reprisals of your victory, for the upcoming revolt could very well not leave you the time to be frightened...

The bourgeois were frightened!!!

Down with the Law!

The anarchists find to be logically consistent with their ideas M. de La Rochefoucauld and all those who protest without worrying about legality,” Anna Mahé tells us.

This is obviously not exact, as I am going to show.

All that is needed is one word to travesty the meaning of a phrase, and so the two words underlined suffice to entirely change the meaning of the one I quote.

If Anna Mahé was the leader of a great newspaper she would hasten to accuse the typographers or the proofreader of the phrase and everything would be for the best in the best of all possible worlds.

Or else she would think it wise to maintain an idea that isn’t a manifestation of her reasoning, but rather the act of her pen running away with itself.

But on the contrary, she thinks that it is necessary, especially in these lead articles that are viewed as anarchist, to make the fewest errors possible and for us to point them out ourselves when we take note of them.

It is to me that this falls today.

The Catholics, the socialists, all those who accept at a given moment the voting system, are not logical with themselves when they rebel against the consequences of a law, when they demonstrate against its agents, its representatives. Only the anarchists are authorized, are logically consistent with their ideas when they act against the law.

When a man deposits his ballot in the urn he is not using a means of persuasion that comes from free examination or experience. He is executing the mechanical operation of counting those who are ready to choose the same delegates as he, to consequently make the same laws, to establish the same regulations that all men must submit to. In casting his vote he says: “I trust in chance. The name that will come from this urn will be that of my legislator. I could be on the side of the majority, but I have the chance of being on the side of the minority. More the better, and too bad.”

After having come to agreement with other men, having decided that they will all defer to the mechanical judgment of number, there is on the part of those who are the minority, when they don’t accept the laws and regulations of the majority, a feeling of being fooled similar to that of a bad gambler, who wants very much to win, but who doesn’t want to lose.

Those Catholics who decided for the laws of exception of 1893–4 through the means of a majority are in no position to rebel when, by means of the same majority, the laws of separation are decided.

Those socialists who want to decide by means of the majority in favor

the laws on workers retirements are in no position to rebel against the same majority when it decides on some law that goes against their interests.

All parties who accept suffrage, however universal it might be, as the basis for their means of action cannot revolt as long as they are left the means of affirming themselves by the ballot.

Catholics, in general, are in this situation. The gentlemen in question in the late battles were “great electors,” able to vote in Senatorial elections, some were even parliamentarians. Not only had some voted and sought to be the majority in the Chambers that prepare the laws, but the others had elaborated that law, had discussed its terms and articles.

Thus being parliamentarists, voters, the Catholics weren’t logical with themselves during their revolt.

The socialists are no more so. They speak constantly of social revolution, and they spend all their time in puerile voting gestures in the perpetual search for a legal majority.

To accept the tutelage of the law yesterday, reject it today, take it up again tomorrow, this is the way Catholics, socialists, parliamentarists in general act. It is illogical.

None of their acts has a logical relation with that of the day before, no more than that of tomorrow will have one with that of today.

Either we accept the law of majorities or we don’t accept it. Those who inscribe it in their program and seek to obtain the majority are illogical when they rebel against it.

This is how it is. But when Catholics or socialists revolt we don’t search for acts of yesterday; we don’t worry about those that will be carried out tomorrow, we peacefully look on as the law is broken by its manufacturers.

It will be up to us to see to it that these days don’t reoccur.

So the anarchists alone are logical in revolt.

The anarchists don’t vote. They don’t want to be the majority that commands; they don’t accept being the minority that obeys.

When they rebel they have no need of breaking any contract: they never accept tying their individuality to any government of any kind.

They alone, then, are rebels held back by no ties, and each of their violent gestures is in relation to their ideas, logical with their reasoning.

By demonstration, by observation, by experience or, lacking these, by force, by violence, these are the means by which the anarchists want to impose themselves. By majority, by the law, never!

Weak Meat

We in Paris, almost without our knowledge, were threatened with a great revolution.

We were threatened with great perturbations in sales from the slaughterhouses of La Villette.

A few snatches of reasons for this reached indiscrete ears. Hoof and mouth was spoken of. But what is this alongside other reasons, ones we should be ignorant of.

Only dead meat should leave the slaughterhouses of the city, and only living meat should enter.

But go see. Beasts enter, pulled on, pushed against. They must enter alive, with a breath, only a breath, a nothing.

And the contaminated carrion is sold, served to the faubourgs of Paris from Menilmontant to Montrouge, from Belleville to La Chapelle.

Go, workers of the slaughterhouses, defend your “rights.” Go, butcher boys, defend “your own.” You must continue to slaughter, to serve poisoned meat.

Go beef drivers, turn and return your fever-bearing meats, from the Beauce to Paris, from Paris to all the workers from the north, the west, and the east? Go ahead, come to Paris, contaminate your animals or bring here the poison contracted elsewhere.

What do evil gestures, useless gestures, poisonous gestures matter? One must live. And to work is to poison, to pillage, to steal, to lie to other men. Work means adulterating drinks, manufacturing cannons, slaughtering and serving slices of poisoned meat.

Working means the rotten meat that surrounds us, that meat that should be slaughtered and pushed into the sewers.

The Cult of Carrion

In a desire for eternal life, men have considered death as a passage, as a painful step, and they have bowed before its “mystery” to the point of veneration.

Even before men knew how to work with stone, marble, and iron in order to shelter the living, they knew how to fashion matter to honor the dead.

Churches and cloisters richly wrapped their tombs under their apses and choirs, while huts were huddled against their sides, miserably sheltering the living.

The cult of the dead has, from the first moments, hindered the forward march of man. It is the original sin, the dead weight, the iron ball that humanity drags along behind it.

The voice of death, the voice of the dead, has always thundered against the voice of universal life, which is ever evolving.

Jehovah, who Moses’ imagination made burst forth from Sinai, still dictates his laws. Jesus of Nazareth, dead for almost twenty centuries, still preaches his morality. Buddha, Confucius, and Lao Tzu’s wisdom still reign. And how many others!

We bear the heavy responsibility of our ancestors; we have their defects and their qualities.

So in France we are the children of the Gauls, though we are French via the Francs and of the Latin race when it comes to the eternal hatred of the Germans. Each of these heredities brings with it obligations.

We are the oldest children of the church by virtue of who knows which dead, and also the grandchildren of the Great Revolution. We are citizens of the Third Republic and we are also devoted to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. We are born Catholics or Protestants, republicans or royalists, rich or poor. We are always what we are through the dead; we are never ourselves. Our eyes, placed atop our heads, look ahead and, however much they lead us forward, it is always towards the ground where our dead repose, towards the past where the dead lived that our education allows us to guide them.

Our ancestors...the past...the dead...

Whole peoples have died from this triple respect.

China is exactly where it was thousands of years ago because it has guarded the first place in their homes for their dead.

Death is not only a germ of corruption due to the chemical disintegration of man’s body, poisoning the atmosphere; it is even more the case because of the consecration of the past, the immobilization of the idea at a certain stage of evolution. Living, it would have evolved, would have been more advanced. Dead, it crystallizes. Yet it is this precise moment that the living choose to admire it, in order to sanctify it, to deify it.

Usages and custom, ancestral errors are communicated from one person to another in the family. One believes in the god of his fathers, another respects the fatherland of his ancestors...Why don’t we respect their lighting system, their way of dressing?

Yes, this strange fact is produced that while the externals and the daily economy improve, change, are differentiated, that while everything dies and is transformed, man, man’s spirit, remains in the same servitude, is mummified in the same errors.

Just as in the century of the torch, in the century of electricity, man still believes in tomorrow’s paradise, in the gods of vengeance and forgiveness, in hells and Valhallas as a way of respecting the ideas of his ancestors. The dead lead us, the dead command us, the dead take the place of the living.

All our festivals, all our glorifications are the anniversaries of deaths and massacres. We celebrate All Saints’ Day to glorify the saints of the church, the Feast of the Dead so as not to forget a single dead man. The dead go to Olympus or paradise, to the right of Jupiter or God. They fill “immaterial” space and they encumber “material” space with their corteges, their displays, and their cemeteries. If nature didn’t take it upon itself to disintegrate their bodies and to disperse their ashes, the living wouldn’t today know where to place their feet in the vast necropolis that would be the earth.

The memory of the dead, their acts and deeds, obstruct the brains of children. We only talk to them about the dead, we should only speak to them about this. We make them live in the realm of the unreal and the past. They must know nothing of the present.

If secularism has dropped the story of Mr. Noah or that of Mr. Moses, it has replaced it with those of Mr. Charlemagne or Mr. Capet. Children know the date of death of Madame Feregonde, but don’t have the least notion about hygiene. Some young girls of fifteen know that in Spain a certain Madame Isabelle spent an entire century wearing one blouse, but are strangely upset when their first menstrual period comes.

Some women, who have the chronology of the kings of France at the tip of their fingers without a single mistake don’t know what to do with a child who cries out for the first time in its life.

While we leave a young girl next to he who is dying, who is in his final throes, we push her away from she whose belly is opening to life.

The dead obstruct cities, streets, and squares. We meet them in marble, in stone, in bronze. This inscription tells us of their birth, and that plaque tells us where they lived. Squares bear their titles or those of their exploits. Street names don’t indicate their position, form, altitude or location; they speak of Magenta or Solferino, an exploit of the dead where many were killed. They recall to you Saint Eleuthere or the Chevalier de la Barre; men, incidentally, whose only quality was that of dying.

In economic life it is also the dead who trace the lives of all. One sees his entire life darkened by his father’s “crime,” another wears the halo of the glory, the genius, the daring of his forefathers. This one is born a bumpkin with the most distinguished of spirits, that one is born noble with the most vulgar of spirits. We are nothing through ourselves; we are everything through our ancestors.

And yet...in the eyes of scientific criticism, what is death? This respect for the departed, this cult of decrepitude, by what argument can it be justified?

Few have asked this, and this is why the question is not resolved.

And in the center of cities, don’t we see great spaces that the living piously maintain: these are cemeteries, the gardens of the dead.

The living find it good to bury, right next to their children’s cradles, piles of decomposing flesh, carrion, the nutritive element of all maladies, the breeding ground of all infections.

They consecrate great spaces planted with magnificent trees and depose typhoid-ridden, pestilential, anthracic bodies there, one or two meters deep. And after a few days the infectious viruses roam the city seeking other victims.

Men who have no respect for their living organism, that they wear out, that they poison, that they put at risk, are suddenly taken with a comic respect for their mortal remains when they should be rid of them as soon as possible, put them in the least cumbersome, the most usable form.

The cult of the dead is one of the most vulgar aberrations of the living. It’s a holdover from those religions that promised paradise. The dead must be prepared for the visit of the beyond: give them weapons so they can participate in the hunts of Velleda, some food for the trip, give them the high viaticum, prepare them to present themselves to God. Religions depart, but their ridiculous formulas remain. The dead take the place of the living.

Whole groups of workingmen and women employ their abilities and energy at maintaining the cult of the dead. Men dig up the earth, carve stone and marble, forge grilles, prepare a house for all of them in order to respectfully bury in them the syphilitic carrion that has just died.

Women weave the shroud, make artificial flowers, fashion bouquets to decorate the house where in the pile a just-ended tubercular decomposition will repose. Instead of hastening to make these loci of decomposition disappear, of using all the speed and hygiene possible to destroy these evil centers whose preservation and maintenance can only spread death around them, everything possible is done to preserve them as long as possible. These mounds of flesh are paraded around in special wagons, in hearses, through the roads and the streets. When they pass, men remove their hats. They respect the dead.

The amount of effort and matter expended by humanity in maintaining the cult of the dead is inconceivable. If all this force were used to receive children then thousands and thousands of them would be spared illness and death.

If this imbecilic respect for the dead were to disappear and make room for respect for the living, we would increase the health and happiness of human life in unimaginable proportions.

Men accept the hypocrisy of necrophages, of those who eat the dead, of those who live off the dead; from the priest, giver of sacred water, to the merchant of eternal homes; from the wreath seller to the sculptor of mortuary angels. With ridiculous boxes that lead and accompany these grotesque puppets, we proceed to the removal of this human detritus and its distribution in accordance with the state of their fortune, when a good transport service, with hermetically sealed cars and a crematory oven constructed in keeping with the latest scientific discoveries would suffice.

I will not concern myself with the use of ashes, though it would seem to me more interesting to use them as humus rather then carrying them around in little boxes. Men complain about work, yet they don’t want to simplify those gestures that overly complicate occasions of their existence, not even to do away with those for the imbecilic — as well as dangerous — preservation of their cadavers. The anarchists have too much respect for the living to respect the dead. Let us hope that some day this outdated cult will have become a road management service, and that the living will know life in all its manifestations.

As we’ve already said, it is because men are ignorant that they surround a phenomenon as simple as death with such religious mumbo jumbo. It also worth noting that this is only the case with human death: the death of other animals and vegetables doesn’t serve as the occasion for similar demonstrations.

Why?

The first men, barely evolved brutes, devoid of all knowledge, buried the dead man with his living wife, his weapons, his furniture, his jewels. Others had the corpse appear before a tribunal to ask him to give an account of his life. Man has always misunderstood the true meaning of death.

And yet, in nature everything that lives dies. Every living organism falls when for one reason or another the equilibrium between its different functions is broken. The causes of death, the ravages of the illness or the accident that caused the death of the individual, are scientifically determined.

From the human point of view then, there is death, disappearance of life, that is, the cessation of a certain activity in a certain form.

But from the general point of view death doesn’t exist. There is only life. After what we call death the transformative phenomena continue. Oxygen, hydrogen, gas, and minerals depart in different forms and associate in new combinations and contribute to the existence of other living organisms. There is no death; there is a circulation of bodies, modifications in the aspect of matter and energy, endless continuation in time and space of life and universal activity.

A dead man is a body returned to circulation in a triple form: solid, liquid, and gaseous. It is nothing but this, and we should consider and treat it as such.

It is obvious that these positive and scientific concepts leave no room for weepy speculations on the soul, the beyond, the void.

But we know that all those religions that preach the “future life” and the “better world” have as their goals causing resignation among those who are despoiled and exploited.

Rather than kneeling before cadavers it would be better to organize life on better foundations so as to get a maximum amount of joy and wellbeing from it.

People will be angered by our theories and our disdain: this is pure hypocrisy on their part. The cult of the dead is nothing but an insult to true pain. The fact of maintaining a small garden, of dressing in black, of wearing crepe doesn’t prove the sincerity of one’s sorrow. This latter, incidentally, must disappear. Individuals should react before the irrevocability and the inevitability of death. We should fight against suffering instead of exhibiting it, parading it in grotesque cavalcades and false congratulations.

This one, who respectfully follows a hearse, had the day before worked furiously at starving the deceased; that one laments behind a cadaver who did nothing to come to his assistance when it would have been possible to save his life. Every day capitalist society spreads death by its poor organization, by the poverty it creates, by the lack of hygiene, the deprivation and ignorance from which individuals suffer. By supporting such a society men are thus the cause of their own suffering, and instead of moaning before destiny they would do better to work at improving their conditions of existence so as to allow human life its maximum of development and intensity.

How could we know life when the dead alone lead it?

How can we live in the present under the tutelage of the past?

If man wants to live, let him no longer have any respect for the dead, let him abandon the cult of carrion. The dead block the road to progress for the living.

We must tear down the pyramids, the tumuli, the tombs. We must bring the wheelbarrows into the cemeteries so as to rid humanity of what they call respect for the dead, but which is the cult of carrion.

The Patriotic Herd

To the barracks! To the barracks! Go, young man of twenty years, mechanics and teachers, masons and draftsmen, stretch out on the bed… on Procrustes’ bed. You are too short… we are going to stretch you out. You are too tall… we are going to shorten you up. Here, this is the barracks… nobody gets smart here, nobody shows off… all are equal, all are brothers… Brothers in what? In stupidity and obedience, of course. Ah! ah! Your body, your head, your form! Who cares about that? Your sentiments, your tastes, your tendencies go down the drain. It’s for the fatherland… so they tell you.

You are no longer a man, you are a sheep. You are in the barracks to serve the fatherland. If you don’t know what that is, too bad for you. Anyway you don’t need to know. You only need to obey. Look right. Look left. Fall into line. Rest. Eat! Drink! Sleep! Ah! You speak of your initiative, your will. Don’t know it here. There is only discipline. What! What are you saying? Someone taught you to reason, to discuss, to form an opinion about men and things? Here, you button it, you shut your mouth. You do not have, you should not have, other concerns or opinions other than your bosses’. You don’t want to, you cannot follow anyone but those whom you have recognized as authority resulting from experience? No joking here, young man. You have a mechanical means for knowing who to obey… Count the gold stripes on the sleeve of a dolman.[3]

So what’s your problem? They taught you to not have idols, to adore nothing? No matter, bend down, kiss the ground, be respectful to the symbol of the fatherland, the idol of the 20th century, the democratic icon. That, my friend, is the republican form of Joan of Arc’s standard. So, check your mind, you intelligence, your will at the door… You are a part of the herd… they only ask for you wool… Enter… and stop thinking. To the barracks! To the barracks!

The army, I said recently, is not raised against an exterior enemy; the army is not raised against an interior enemy; the army is raised against ourselves; against our will, our “me.” The army is the revenge of the crowd against the individual, of the numbers against the single. The army is not the school of crime; the army is not the school of debauchery, or if it is, that’s the last of its faults; the army is the school of spinelessness, the school of emasculation.

Despite the family, despite school, despite the workshop, there is still a little personality in every man; from time to time movements arise in reaction against the milieu. The army, whose locale is the barracks, comes to annihilate the individual. The twenty year old man has the strong virility that allows him to dedicate himself to the development of an idea. He does not have the fetters of habit, the watering down of the home, the weight of years. He can push his logic to the point of revolt. He has, within himself, the lifeblood needed to make the buds burst and the flowers blossom. At the bend in the road comes the ambush of the fatherland, the army pitfall, the mousetrap barracks. Then, all faculties are obstructed. Thinking must stop. Reading must stop. Writing must stop. And in no case can there be any will. From head to toe, your body belongs to the army. You no longer choose a hairstyle nor the shoes that you would like. You no longer wear clothing that is roomy or loose around the waist. You no longer go to bed when you get tired… There is one regulation shoe, one regulation haircut, one regulation style of clothing. Bread is made in communal batches and your break time has been set for years. What’s that? A case of endurance?

But there’s worse… in the streets you don’t speak with whom you’d like! You don’t go to the place you want! You don’t read the papers you’re interested in! Your visits, your meetings and your readings are all subject to regulations! And if by chance you have sexual problems, there is a whorehouse for the soldiers and one for the officers, as there are also different places to drink alcohol.

Everything is regulated, everything is planned out. The individual is assassinated. Initiative is dead. The barracks are the stables for the patriotic herd. From them come herds ready to become the electoral herds. The army is the formidable instrument raised by governments against individuals; the barracks is the channeling of the human forces of the all for the benefit of the few. You enter a man, become a soldier, exit a citizen.

The Greater of Two Thieves

Every day, every hour, without rest nor remittance; the battle of life. A hor rible battle if so, where the cadavers pile up, the wounded number in themillions. Battle of Life for life. Battle against the elements, battle against the self. Battle against other humans. Battle of those who are rich and those who aren’t. Battle of those who have against those who don’t. Battle of the future against the past, of science against ignorance.

Right now, in Amiens, it seems to be taking a more cruel form, which makes it more noticeable to everybody.

Two groups of individuals are grappling with one another. One of them seems to have achieved victory. It no longer fights, it judges. It has named delegates who put on uniforms and decorate themselves with special names: gendarmes, judges, soldiers, prosecutors, jurors. But nobody’s fooled; everybody knows the usual collaborators of the social war: thieves, counterfeiters, assassins, depending on the situation.

Securely held, the members of the other gang face them. They are there, in person. They did not send delegates. One has the sense that they are bound but not defeated. And when they shake their heads, the delegates and the spectators cower.

Those of the first gang call this process bringing justice and say they are prosecuting crime. Everyone sees that it isn’t remorse that leads their enemies, but handcuffs. And the debate begins. They are two terrible gangs and their organizations strike fear. To think of all the spirit lost in the subtleties and the ruses of these fighters. What improvements of the fate of each and every person would come out of their combined efforts. What steps forward science could have made with all of these brains preoccupied with falsifying to survive.