Alan Carter

Beyond primacy

Marxism, anarchism and radical green political theory

Marxism and technological primacy

The theoretical dispute between Marx and Bakunin

A weakness in Marx’s theory of the state

Transcending explanatory primacy

An environmentally hazardous dynamic

Abstract

The most sophisticated philosophical defence of Marx’s theory of history– G.A. Cohen’s—deploys functional explanations in a manner that accords explanatory primacy to technological development. In contrast, an anarchist theory can be developed that accords explanatory primacy to the state. It is, however, possible to develop a theory of history that accords explanatory primacy neither to the development of technology nor to the state but which nevertheless possesses the explanatory powerof both the Marxist and the anarchist theories. Such a theory can also provide the foundations for a radical environmentalist political theory.

Introduction

Environmentalists can be found right across the political spectrum (see Dryzek 1997). Not surprisingly, the most politically radical environmentalists have tended to adhere to some form of either eco-Marxism (for example, O’Connor 1998) or eco-anarchism (for example, Bookchin 1982). Here, I explore both Marxist and anarchist theory as a prelude to providing a glimpse of a genuine, radical environmentalist theory. I begin by outlining G.A. Cohen’s defence of Karl Marx’s theory of history. I then indicate how an anarchist theory can be developed that builds upon elements drawn from Cohen’s defence of Marx, while nevertheless standing in contraposition to Cohen’s theory. I then show how elements of both these approaches can be combined within a theory that transcends both Marxist and anarchist theories. Finally, I show how such a general theory can provide the basis for an environmentalist political theory with truly radical implications.

Marxism and technological primacy

In numerous places, Marx appears to subscribe to a form of technological determinism (for example, Marx 2000b, pp. 209–211, Marx, 2000k, p. 281, Marx and Engels 2000a, pp. 177–178, and, especially, Marx 2000d, p. 425), which is, perhaps, most succinctly expressed in his dictum that ‘[t]he hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist’ (Marx 2000h, pp. 219–220). In a nutshell, Marx appears to hold that the development of the forces of production—principally the technology that is employed in the production of a society’s means of subsistence, along with the labour-power that is required to operate that technology—explains the relations of production that obtain within a society, and he further appears to hold that the relations of production explain (what he calls) the ‘superstructure’ of legal and political relations that also obtain within a society.

Elsewhere, however, Marx seems to hold that competition between capitalists forces them to introduce new technologies (for example, Marx and Engels 2000b, p. 248). In which case, the relations of production that obtain within a society would appear to be what explains the development of its forces of production, and this seems, prima facie at least, to contradict technological determinism.

Can this seeming contradiction be avoided? G.A. Cohen has argued that it can, so long as one invokes functional explanations (Cohen 1978).[1] For the claim that the development of the forces of production possesses explanatory primacy with respect to the nature of the relations of production can be reconciled with the claim that the relations of production exert a causal influence on the development of the forces of production by arguing that the development of the forces of production in a given society ‘selects’ relations of production within that society that are functional for developing its forces of production. Here, the development of the forces of production enjoys explanatory primacy (because it is the development of the forces of production that does the ‘selecting’), while the causal influence of the relations of production on the development of the forces of production is not merely acknowledged but is actively employed within this particular form of explanation; for it is precisely because of their effect on the development of the forces of production that the latter selects those particular relations of production. And when different relations of production would be more functional for the development of the productive forces, those new relations come to be selected. Thus, on Cohen’s account, revolutionary transformations of society occur when the relations of production become, in some sense, dysfunctional for the further development of the forces of production (see Carter 1998).

Moreover, Cohen views the relationship between the relations of production and the superstructure of legal and political institutions—principally the state—also as best construed in terms of a functional explanation. On Cohen’s account, relations of production ‘select’ a superstructure of legal and political institutions that is suited to stabilising those relations of production. In short, the superstructure of legal and political institutions is ‘selected’ because it is functional for the relations of production. Thus, in a structurally similar manner to his account of the relationship between the forces and relations of production, Cohen argues that the relations of production ‘select’ a superstructure of legal and political institutions because of the latter’s effect on those relations of production. And a revolution that brings in new relations of production, because the old ones have become dysfunctional for the development of the forces of production, will involve overthrowing the prevailing superstructure of legal and political institutions, for that superstructure is especially suited to preserving the old relations of production.

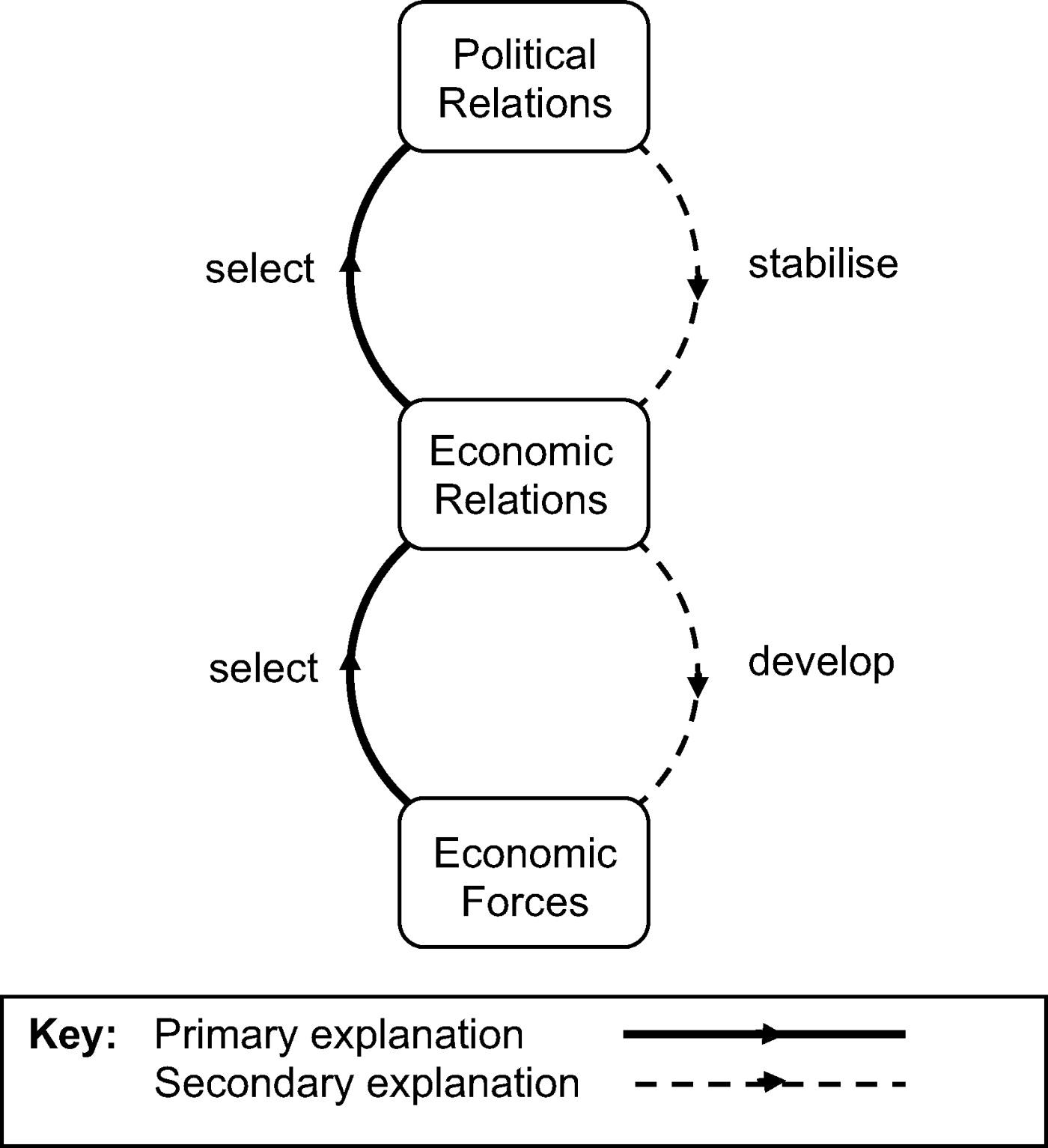

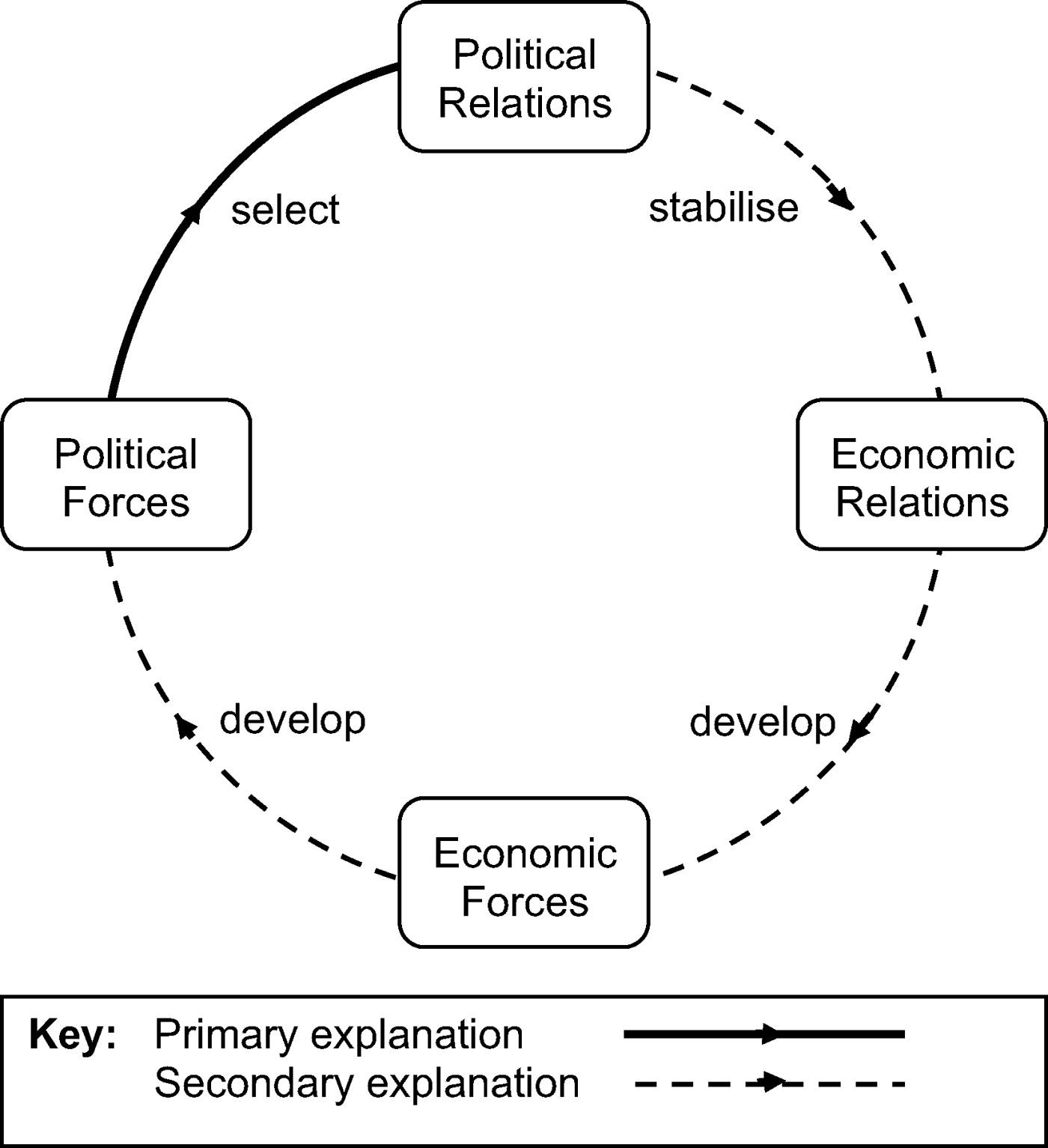

Cohen’s defence of Marx’s theory of history is thus grounded on a bi-directional theoretical model. The bottom level of the model, as it were, explains the level above it, which in turn affects the level below it. To be precise, the development of the forces of production (the development of the economic forces, in other words) explains the relations of production (the economic relations), and the relations of production affect the development of the forces of production. (For example, because capitalist economic relations develop the productive forces faster than do feudal economic relations, the former came to replace the latter.) Moreover, the middle level of the model, as it were, explains the top level, which in turn affects the level below it. To be precise, the relations of production explain the superstructure of legal and political institutions (which are, clearly, political relations), and the superstructure affects the relations of production. (For example, feudal economic relations supposedly select an absolute monarchy, which is conducive to stabilising feudal economic relations; while ‘bourgeois’ economic relations supposedly select a modern representative state, which is, ostensibly, especially conducive to stabilising bourgeois economic relations.) But crucially, this is not simply a bi-directional model. It is what we might think of as a weighted one, for one direction of explanation possesses explanatory primacy: the upward direction of explanation is, as it were, primary, while the downward direction of explanation is, as it were, secondary ( Figure 1).

The theoretical dispute between Marx and Bakunin

One obvious problem with a weighted bi-directional model is that it may get the weighting the wrong way round. Perhaps what the model takes to be primary is actually secondary, and what it takes to be secondary is, in actual fact, primary. Indeed, it could be argued that this is what lies behind the opposition between Marxist and anarchist theories of the relationship between the state and the economic structure of society. For consider how Frederick Engels (1989, pp. 306–307) characterises the dispute between Marx and his major anarchist opponent, Mikhail Bakunin:

While the great mass of the Social Democratic workers hold our view that state power is nothing more than the organization with which the ruling classes—landowners and capitalists—have provided themselves in order to protect their social privileges, Bakunin maintains that the state has created capital, that the capitalist has his capital only by the grace of the state. And since the state is the chief evil, the state above all must be abolished; then capital will go to hell of itself. We, on the contrary, say: abolish capital, the appropriation of all the means of production by the few, and the state will fall of itself. The difference is an essential one … [2]

Crucially, Marx’s theoretical approach generates a significant political implication: if one correctly sorts out the economic structure of society, then political problems will disappear. For, according to Marx, political power is class power (see Marx and Engels 2000b, p. 262). Hence, political power must disappear when classes disappear. So it is not surprising that he should insist that ‘the economical subjection of the man of labour to the monopolizer of the means of labour, that is, the sources of life, lies at the bottom of servitude in all its forms, of all social misery, mental degradation, and political dependence … ’ (Marx 1974, p. 82). Thus Marx concludes that all major social and political problems will vanish once economic subjection has been removed by means of a revolution.

But it is precisely this conclusion that anarchists have traditionally rejected. In Bakunin’s view, for example, centralised, authoritarian revolutionary means will inevitably lead to a centralised, authoritarian post-revolutionary state, which is surely not implausible if the chosen revolutionary means include the creation of coercive political structures that will, on the morrow of the revolution, remain in place. Hence, as Engels acknowledges, Bakunin’s fear that authoritarian revolutionary means will produce an authoritarian, post-revolutionary outcome has significant implications for his views regarding the organisation of the International Workingmen’s Association: in short, because ‘the International … was not formed for political struggle but in order that it might at once replace the old machinery of the state when social liquidation occurs, it follows that it must come as near as possible to the Bakuninist ideal of future society’ (Engels 1989, p. 307).

Moreover, Bakunin (1973, pp. 281–282) appears to agree that his dispute with Marx is roughly as Engels depicts it:

To support his programme for the conquest of political power, Marx has a very special theory, which is but the logical consequence of [his] whole system. He holds that the political condition of each country is always the product and the faithful expression of its economic situation; to change the former it is necessary only to transform the latter. Therein lies the whole secret of historical evolution according to Marx. He takes no account of other factors in history, such as theever-present reaction of political, juridical, and religious institutions on the economic situation. He says: ‘Poverty produces political slavery, the State.’ But hedoes not allow this expression to be turned around, to say: ‘Political slavery, the State, reproduces in its turn, and maintains poverty as a condition for its own existence; so that to destroy poverty, it is necessary to destroy the State!’ And strangely enough, Marx, who forbids his disciples to consider political slavery, the State, as a real cause of poverty, commands his disciples in the Social Democratic party to consider the conquest of political power as the absolutely necessary preliminary condition for economic emancipation.

Bakunin is certainly unfair in caricaturing Marx as taking no account of political effects on the economic sphere; but this notwithstanding, it seems uncontroversial that Marx lays the greater explanatory weight on the economic, while Bakunin lays it on the political.

In summary, then, because Marx assumes that political power is premised upon inegalitarian relations of production, he concludes that political power will disappear once the appropriate relations of production are introduced. Consequently, because of Marx’s theory regarding the relationship of the state to the economic structure of society, Marx simply dismisses Bakunin’s fears regarding political centralisation within the International. Moreover, Cohen’s weighted bi-directional model is wholly consistent with the assumption shared by both Marx and Engels that political power will disappear in communism. For while inegalitarian economic relations, which manifest class conflict, seem to require a coercive state apparatus to stabilise them, non-conflictual egalitarian economic relations might be thought to lack any such requirement. Thus, it might be presumed, no coercive state will be selected by egalitarian economic relations.

A weakness in Marx’s theory of the state

But there are grounds for thinking that there is a fundamental flaw in Marx’s assumption that the state will necessarily vanish in a communist society. From some of his earliest writings onwards (see, especially, Marx 2000a,c), Marx locates the explanation of the state in divisions within civil society. Rights to private property split civil society into discrete persons who, in becoming economically individualised, seem to require a state above them to secure the public interest. But once the state sees to the public interest, individuals within civil society are free to pursue their own private interests, within the bounds of the law legislated and enforced by the state, without regard for other persons—thus strengthening the need for a state above them to secure the public interest. The result is a re-enforcing spiral whereby individualism and egoism at the level of civil society require a seeming community at the level of the state, which, in turn, exacerbates that individualism and egoism at the level of civil society (see ‘Thesis IV’ in Marx 2000i, p. 172; also see Marx 2000c, p. 53 and Marx 2000j, pp. 71–72).[3]

Later, Marx focuses in particular on the fact that some—the bourgeoisie—own the means of production while others—the proletariat—own only their ability to labour. Thus property rights divide society into two major classes (see Marx and Engels 2000b, pp. 246–255), who stand opposed to each other because of their conflicting interests as a result of their differential ownership. This particular fracturing of society along class lines is then taken by Marx to be the explanation of the modern representative state, which, he claims, stands in a special relation to one of those classes (see Marx and Engels 2000b, p.247)– what he terms ‘the ruling class.’ Later still, Marx devotes more attention to the complex relationship between classes and the state, and between their various sub-groupings (see Marx 2000f, 2000g), but throughout his writings there runs a common theme regarding the modern state: it arises because of fracturing at the economic level. Moreover, Marx never doubts that this entails that the removal of that fracturing by the establishment of a classless society will inevitably lead to the disappearance of the state.[4]

But that the state has arisen due to fracturing at the economic level, even if this were uncontroversially true,[5] does not allow one simply to conclude that removing those fractures entails the disappearance of the state. To see this, distinguish, on the one hand, between necessary and sufficient conditions and, on the other, between originating conditions—those conditions that are eithernecessary or sufficient for a state of affairs to arise—and perpetuating conditions—those conditions that are either necessary or sufficient for a state of affairs to continue. If fracturing within civil society is the explanation for how it is that the modern state has arisen, then fracturing within civil society may well only constitute a sufficient originating condition. But for the removal of fracturing within civil society to entail the disappearance of the state, fracturing within civil society would have to be a necessary perpetuating condition of the state. Consider a tumour: A toxin might cause a tumour to start developing, but later removal of that toxin might well lead neither to the tumour’s ceasing to grow nor to its disappearance. Similarly, the modern representative state might possibly have arisen due to fracturing within civil society. But even if this were so, the removal of that fracturing might well not lead to the state’s disappearance—just as the removal of the toxin would not suffice as a cure for the tumour it had caused. And one reason why the removal of fractures within civil society might not lead to the state’s disappearance is that once an authoritarian state had arisen, even if its rise were due to fracturing within civil society, such a state might have the power to tax those within civil society to such an extent that it could pay for a large enough police force and standing army to keep it in power even once that fracturing within civil society had been removed.

Anarchism and state primacy

Perhaps, then, we should not be too quick to reduce political power to economic power. And if we refrain from such a reduction, then the anarchist critique of Marxist political strategy is not so easily dismissed as Engels had presumed. And interestingly, Bakunin’s approach might be thought to be supported to some degree by a weighted bi-directional explanatory model that reverses the weighting found in Cohen’s Marxist model; for recall that Bakunin (1973, p. 282) moots the suggestion that ‘the State … maintains poverty as a condition for its own existence; so that to destroy poverty, it is necessary to destroy the State’—which certainly sounds like a functional explanation.

So, let us see how an anarchist might deploy a complex functional explanation to cast doubt on the Marxist conclusion that if revolutionaries were to ‘abolish capital, the appropriation of all the means of production by the few,’ then ‘the state will fall of itself’ (Engels 1989, p. 307). To do so, we must first isolate an additional element to those clarified by Cohen. In identifying economic forces (the forces of production), economic relations (the relations of production) and political relations (the structure of legal and political institutions), Cohen, in effect, distinguishes between forces and relations, on the one hand, and between the economic and the political, on the other. But this pair of distinctions allows a fourth category to be identified: namely, political forces.

What might constitute the political forces of a modern society? Cohen (1978, p. 32) argues that the forces of production include the means of production (that is, tools, machines, premises, raw materials, etc.) and labour-power (that is, the strength, skill, knowledge, etc. of the producing agents). If the forces of production are the principal economic forces at play within a society, then we might suspect that the principal political forces presently at play within any of today’s societies are its forces of coercion. If so, then it is not simply labour-power that industrial workers sell; rather it is economic labour-power, for military personnel and the police sell their capacity to labour, too. But it seems inappropriate to characterise the capacity to labour offered by soldiers and the police as an economic force, given that the work soldiers perform is potentially more destructive than productive. Hence, it seems that we should distinguish between economic and political labour-power. And we might therefore regard the forces of coercion as including political labour-power (that is, the strength, skill, knowledge, etc. of the coercive agents) and the means of coercion (that is, the tools, machines, premises, etc. that are deployed in order to maintain political control).[6]

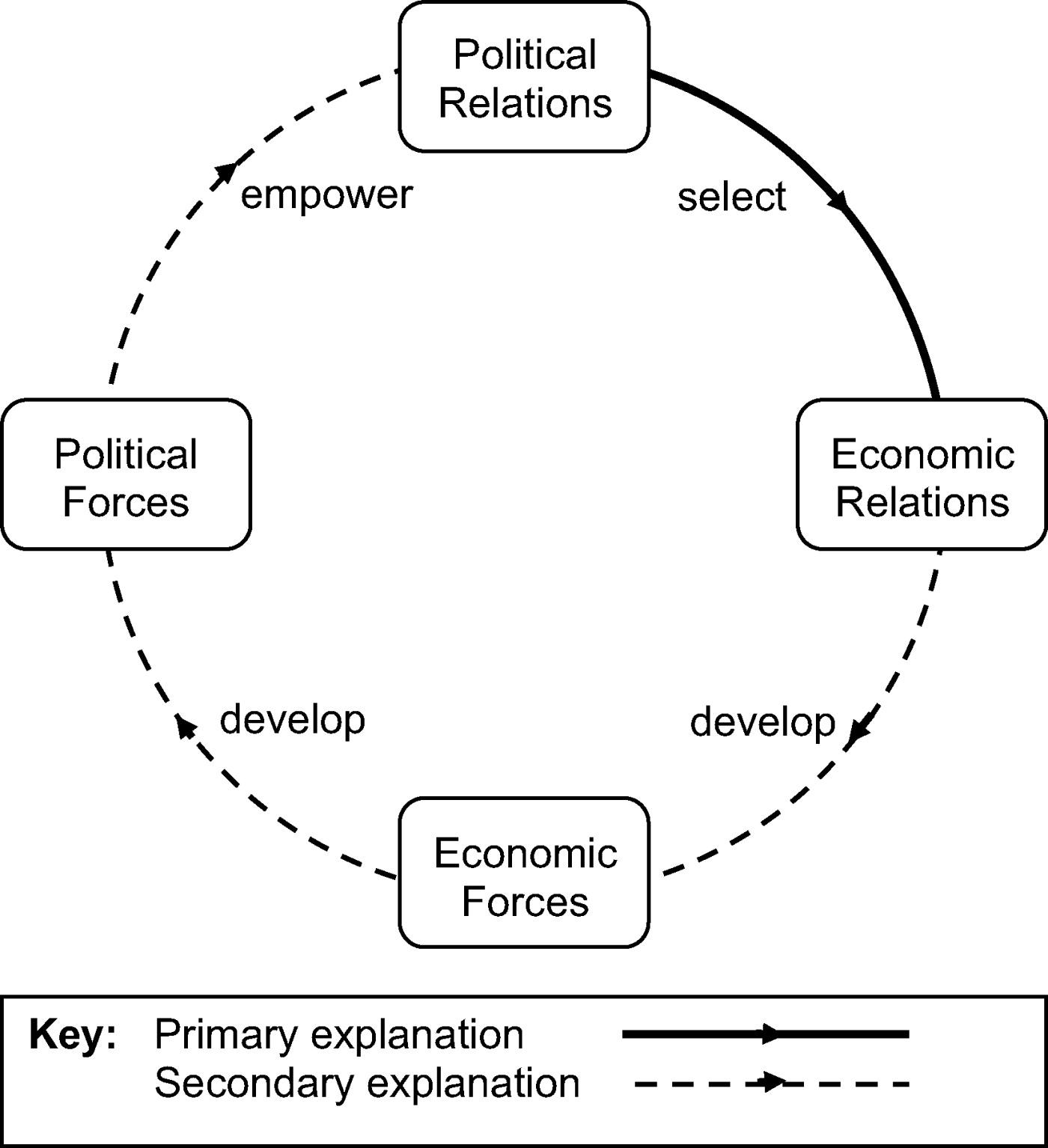

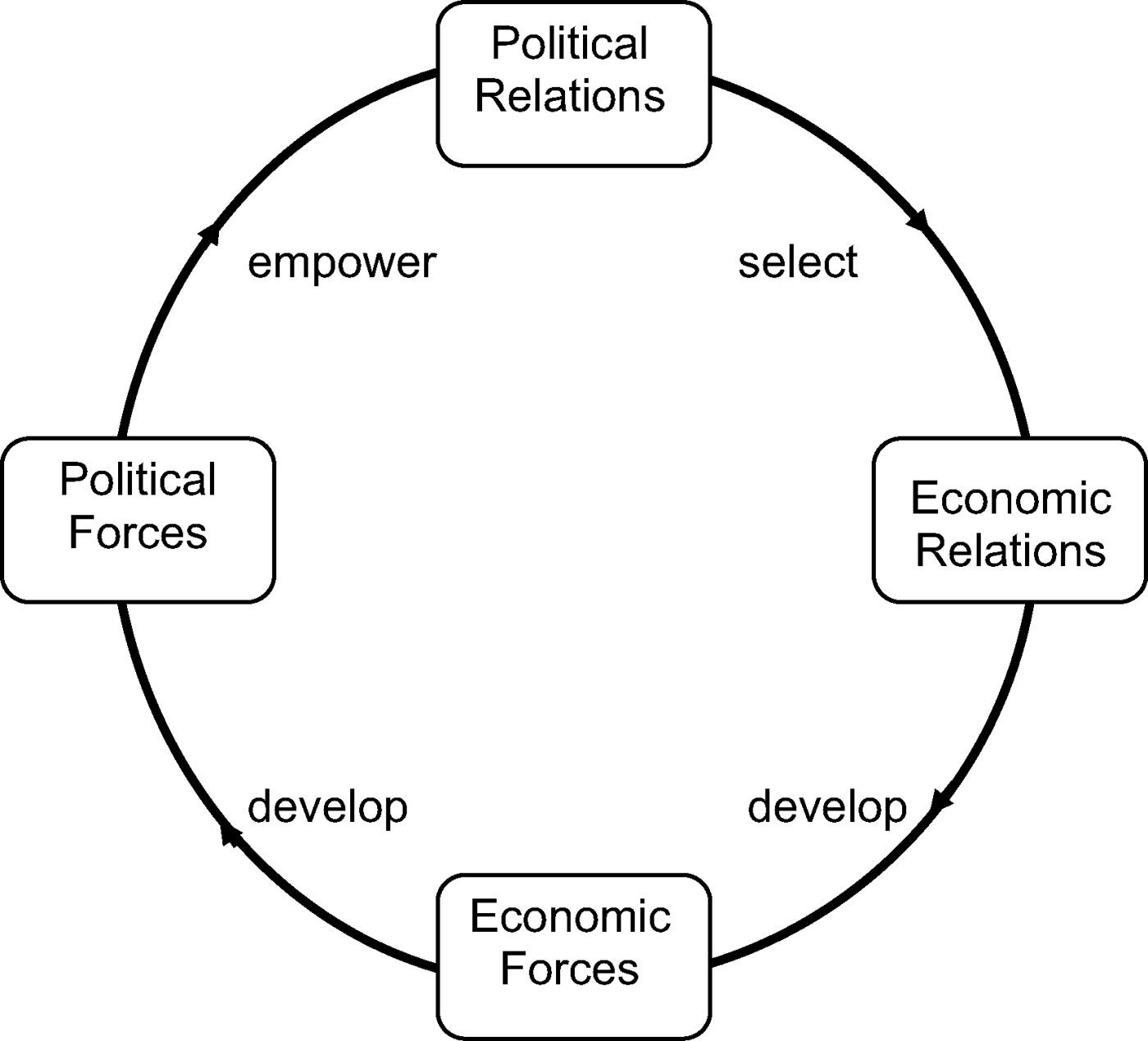

How might these four elements—the economic forces (the forces of production), the economic relations (the relations of production), the political relations (the structure of legal and political institutions) and the political forces (the forces of coercion and/or defence)—be plausibly situated within a weighted, bi-directional, explanatory model? Given the need that states have to develop their military capacity in order to remain militarily competitive with other, potentially threatening, states,[7] they need to develop the productive capacity that allows the development of their military capacity. But in order to develop their productive capacity, they need economic relations that are able to drive, rather than inhibit, that development. Hence, it can be argued that the political relations (the structure of legal and political institutions) select and stabilise economic relations (the relations of production) that are conducive to developing the economic forces (the forces of production) that facilitate the development of the political forces (the forces of coercion and/or defence), because the development of the political forces empowers those political relations. In short, it can be argued that political relations select and stabilise economic relations that are functional for them ( Figure 2).

Interestingly, an anarchist model of this general type possesses no less explanatory power than Cohen’s Marxist model. For just as with the Marxist model, it claims that when economic relations fail to develop the productive forces sufficiently, they will be replaced.[8] And just as the Marxist model can explain the development of the productive forces, so, too, can this particular anarchist model. However, it might be thought that the Marxist model explains the relatively laissez-faire nature of the liberal state, while an anarchist model of this type cannot. But such an anarchist model allows one to claim that the state can choose to remain in the background when capitalist economic relations are being stabilised because, due to their seemingly voluntary, contractual nature, their stabilisation requires less overt force than previous economic relations required. So this particular anarchist model is, in fact, at no disadvantage with respect to accounting for the ostensibly liberal nature of the state in capitalist societies.[9] But unlike Cohen’s Marxist model, such an anarchist model also allows one to understand how it is that certain economically unprofitable technologies, such as nuclear power, might come to be developed. Civil nuclear power programmes are required for the development of nuclear weapons, which are functional for the state insofar as they allow it to defend itself. But the development of such unprofitable technologies appears to make little, if any, sense on the Marxist model. Indeed, once it is realised that the state, directly or indirectly, selects the development of kinds of technology that are functional for preserving the power of the state, the core Marxist assumption that capitalism will develop the technology required for a communist society becomes highly implausible (see Carter 1988, passim).

What is especially important, however, is that the complex functional explanation at the heart of this anarchist model does not support the Marxist conclusion that if revolutionaries were to transform the economic relations, then ‘the state will fall of itself’; for if egalitarian relations of production proved not to be functional for the state, then it would replace them with relations of production that were.[10] Thus, it is in a revolution aiming to bring in communism that this anarchist theory, which accords explanatory primacy to the state, can be tested against the Marxist theory, which instead accords explanatory primacy to the development of the productive forces, and explanatory priority to the relations of production over the structure of legal and political institutions.

Ironically, the revolution that is widely (if, perhaps, mistakenly) viewed as archetypically Marxist is the Russian Revolution that began in 1917. During the course of that revolution, the workers set up factory committees to run industry. But egalitarian economic relations did not lead to the withering away of the state, as Engels (1976, p. 363) had predicted. Instead, the factory committees were replaced by highly inegalitarian, ‘one-man’ management. And how did Lenin justify this authoritarian imposition upon the workers? As he wrote within a year of coming to power: ‘All our efforts must be exerted to the utmost to … bring about an economic revival, without which a real increase in our country’s defence potential is inconceivable’ (Lenin 1970, p. 6). In other words, perhaps fearing that workers’ control would be less productive, the Marxist state imposed inegalitarian economic relations that were functional, in offering the prospect of greater productivity, for the state’s military requirements.

This seems to provide a clear corroboration for an anarchist state-primacy theory, which claims that political relations choose economic relations that are conducive to developing the economic forces, which facilitate the development of the political forces, for the development of the political forces maintains the empowerment of those political relations. But it also seems, simultaneously, to falsify the Marxist technological-primacy theory. And such an anarchist, weighted bi-directional, explanatory model, as apparently corroborated by the Russian Revolution, would provide theoretical justification for the anarchist objection that, even if revolutionaries were to ‘abolish capital,’ it cannot simply be presumed that ‘the state will fall of itself.’

Transcending explanatory primacy

But is a theory that accords explanatory primacy to the state necessary for upholding this principal anarchist objection to Marxist revolutionary praxis? I shall argue that it is not. For as long as the state is able to replace egalitarian economic relations with inegalitarian ones, even if it is the case that the political relations lack overall explanatory primacy, the Marxist contention that ‘the state will fall of itself’ if revolutionaries were to abolish capital remains mistaken.

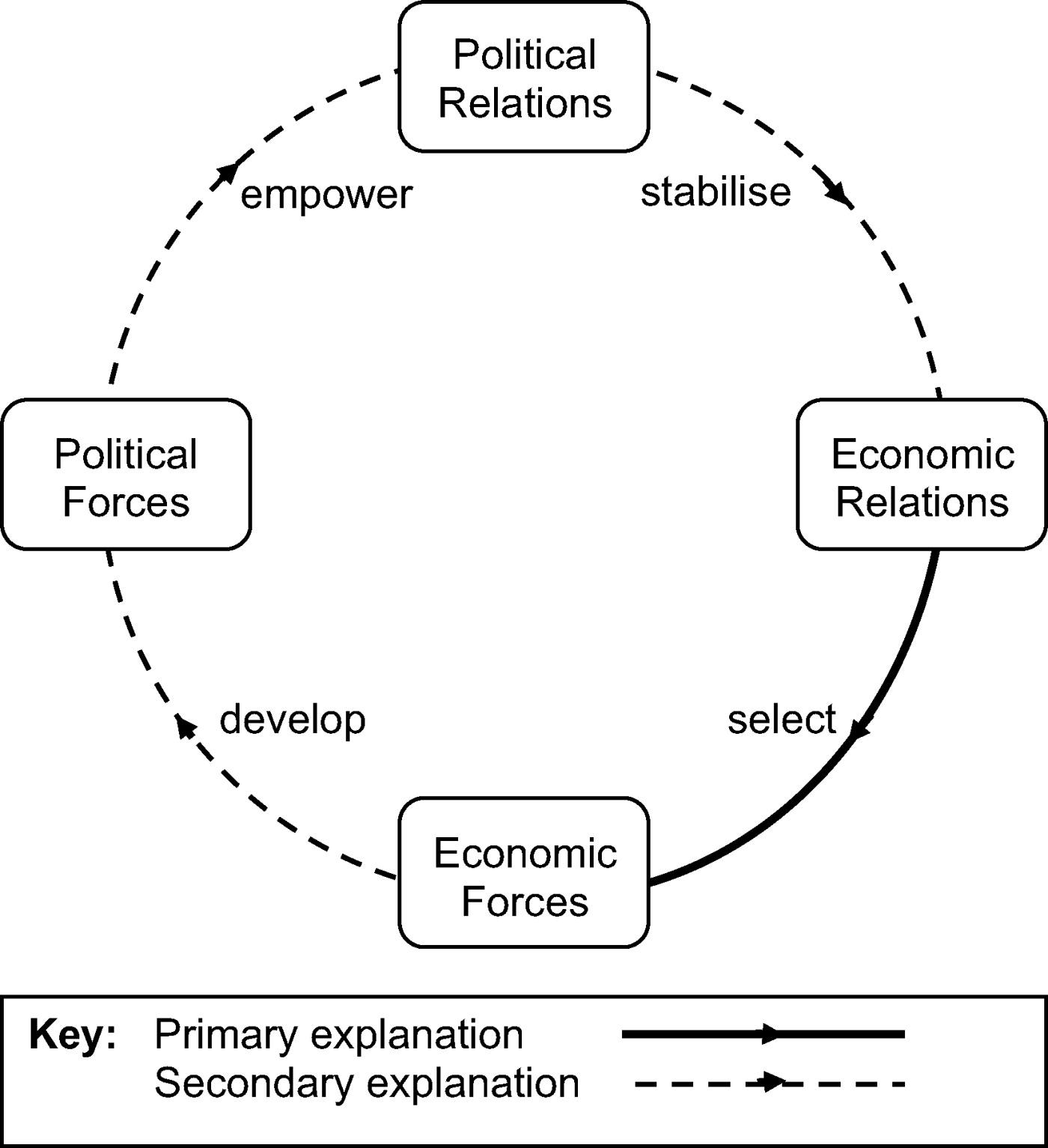

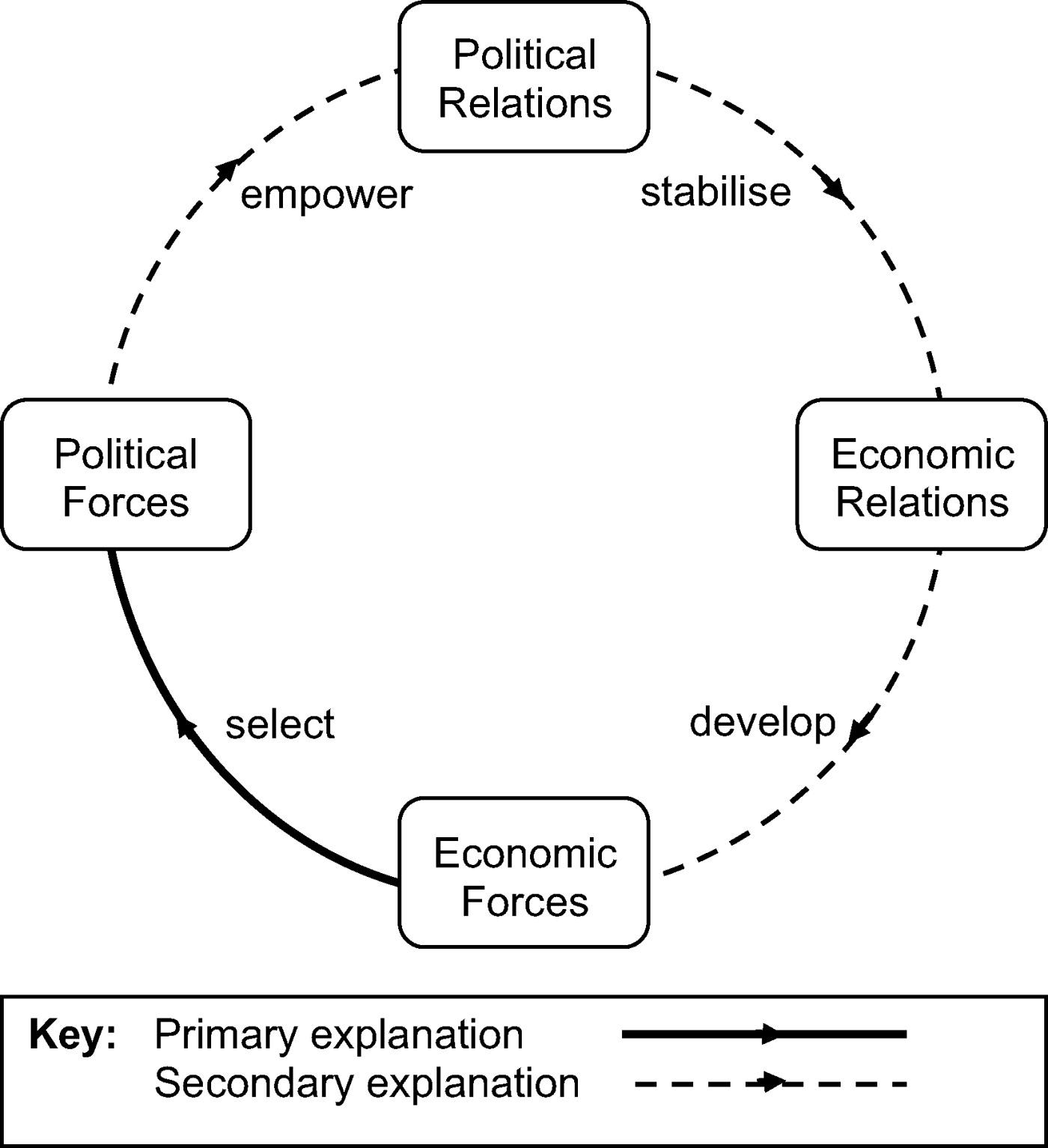

To see this, let us consider a complex of functional explanations that would support the anarchist objection, and which is also seemingly corroborated by the Russian Revolution that began in 1917, but which does not accord explanatory primacy to the state. Now, it may indeed be the case that the political relations (the structure of legal and political institutions) stabilise economic relations (the relations of production) that are conducive to developing the economic forces (the forces of production), which facilitate the development of the political forces (the forces of coercion and/or defence), because the development of the political forces is necessary for maintaining the empowerment of the political relations (as in Figure 2). But it may also be the case that the economic relations in part develop the economic forces, which facilitate the development of the political forces that empower the political relations, because, as those political relations are required to stabilise those economic relations, this is functional for the economic relations ( Figure 3). And it may also be the case that the development of the economic forces facilitates the development of the political forces, which, in turn, empowers the political relations which stabilise the economic relations, in part because that is functional for the development of the economic forces ( Figure 4). And it may also be the case that the political forces empower the political relations which stabilise the economic relations that develop the economic forces, because, with the latter’s facilitating the development of the political forces, the empowerment of the political relations is functional for the development of those political forces ( Figure 5).

If all of these functional explanations are combined, then what we have, in effect, is represented by Figure 6, where each element of the model ‘acts’ or ‘behaves’ as it does because that ‘action’ or ‘behaviour’ is functional for the element in question.

On this complex of functional explanations, there is no explanatory primacy; hence it is not, as it stands, a weighted explanatory model. But one could accord different weightings to each of the component functional explanations. Nevertheless, on a basic non-weighted model combining these four functional explanations, it remains the case that the state can select inegalitarian economic relations should egalitarian economic relations arise, and this seems sufficient to reject the Marxist assumption that egalitarian economic relations will inevitably lead to the withering away of the state. Indeed, were the economic relations the only element to be transformed by revolutionary action, then those relations, while having some power to transform the economic forces, would fail to obtain support from either the political relations or the political forces if it was not functional for the political relations or for the political forces to stabilise those new economic relations. But because the political relations are consistent with the prevailing political forces, which are themselves consistent with the prevailing economic forces, then the political relations would enjoy support from the political forces, which themselves would enjoy support from the economic forces. In which case, we might expect the political relations to be far more capable of replacing the transformed economic relations with ones more suited to the interests of those political relations than the economic relations would be of effecting a permanent, radical transformation of the economic forces (never mind of the whole system).

Consequently, even without the particular anarchist model discussed earlier, which accords explanatory primacy to the state, the principal anarchist objection to Marxist strategy can still be upheld. Call the new model presented here ‘a multiple functional explanatory model’ or ‘a multiplex model,’ for short.[11] A model of this kind is all that an anarchist needs to reject Marxist revolutionary praxis. Moreover, Lenin’s replacement of workers’ factory committees with ‘one-man’ management serves as seeming corroboration both for a state-primacy model and for such a multiplex model.

An environmentally hazardous dynamic

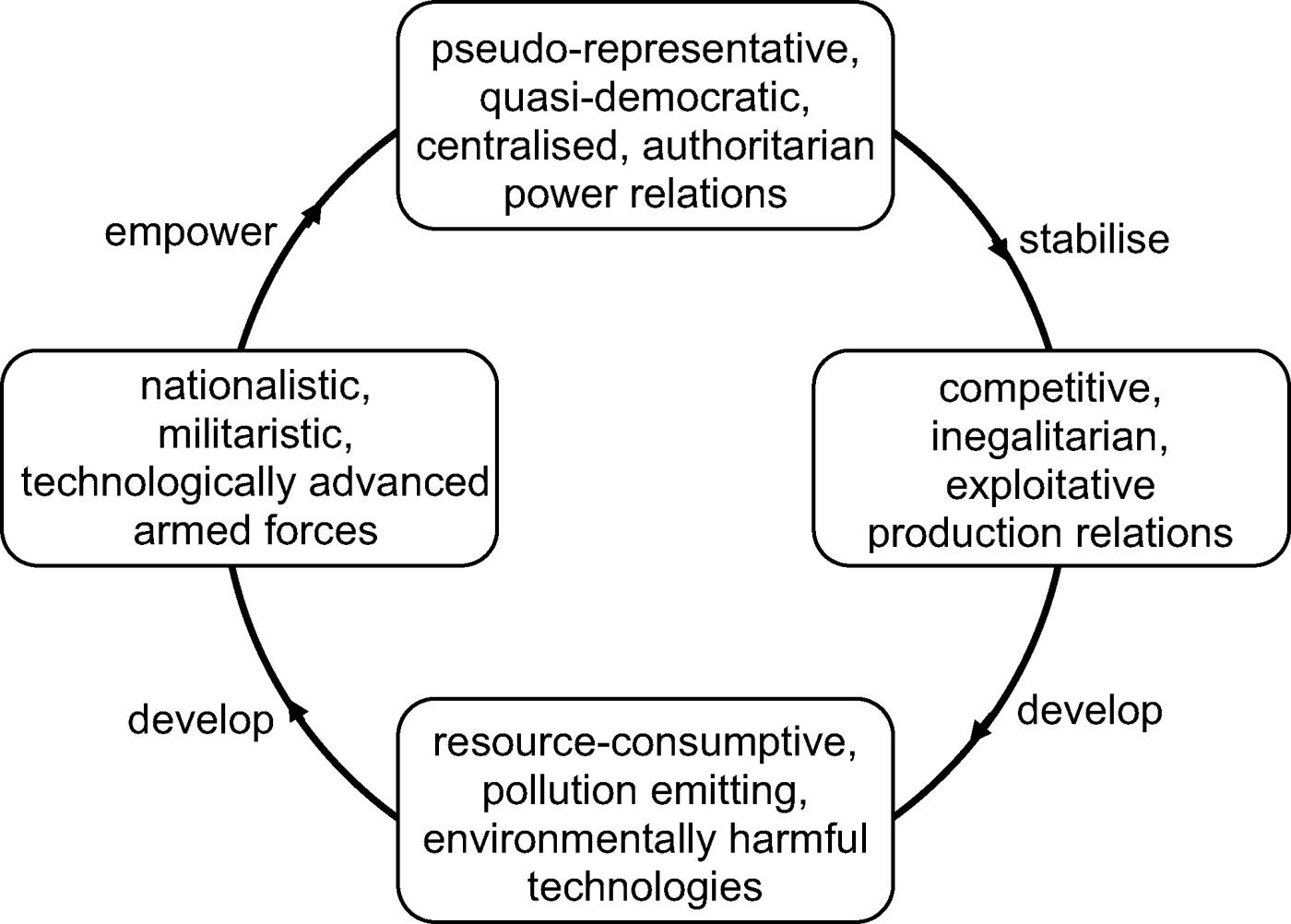

Now, while an anarchist state-primacy model is capable of grounding a genuinely radical, green political theory,[12] the multiplex model sketched above can equally provide such a grounding. In order for it to do so, all that is required is a particular spelling out of the current form of the political relations, the economic relations, the economic forces and the political forces. For what if the political relations actually comprise pseudo-representative, quasi-democratic,[13] centralised, authoritarian power relations? And what if the economic relations actually comprise competitive, inegalitarian, exploitative production relations? And what if the economic forces actually include highly resource-consumptive, environmentally damaging, pollution-emitting technology? And what if the political forces actually include nationalistic, militaristic armed forces wielding technologically advanced, nuclear weaponry?

First, authoritarian power relations of this type would tend to stabilise such production relations when they developed such environmentally damaging technology (for example, nuclear power) in order to supply their militaristic armed forces with nuclear weaponry and to generate the surplus that would fund those armed forces, because this is functional for such authoritarian power relations (given that all this would be required to preserve them in a world containing competing nuclear-armed states).

Second, such exploitative production relations would tend to develop such environmentally damaging technology in order not only to enrich those who exercise control within those relations but also to fund such militaristic armed forces and supply them with their weaponry so that they may preserve such authoritarian power relations, because this is functional for those economic relations (given that all this is necessary to stabilise them).

Third, the development of such environmentally damaging technology generates the surplus that funds such militaristic armed forces, and such technology (e.g. nuclear power) would also tend to supply them with their weaponry so that they may preserve such authoritarian power relations that empower such exploitative production relations, in part because this is functional for the development of such environmentally damaging technology.

Fourth, such militaristic armed forces, supplied with particular weaponry, would tend to empower such authoritarian power relations which stabilise such exploitative production relations that develop such environmentally damaging, pollution-emitting technology, because this is functional for those armed forces in generating the surplus that funds them and in supplying them with their particular weaponry.[14]

If all of this is put together, as in Figure 7, then what emerges is what we might label an environmentally hazardous dynamic.[15] Moreover, each of the four component functional explanations reveals just how difficult it would be to break free from such a dynamic, as we shall now see.

If one attempts merely to alter radically the economic relations (the relations of production) in a direction that is not functional for the political relations, then the political relations (the structure of legal and political institutions) can be expected to introduce or re-introduce economic relations that are more conducive to developing the economic forces (the forces of production), which facilitate the development of the political forces (the forces of coercion and/or defence), because the development of the political forces maintains the empowerment of the political relations (as in Figure 2).

But if one attempts, instead, merely to develop radically different economic forces—ones that are not functional for the economic relations—then the economic relations can be expected to introduce or re-introduce economic forces which better facilitate the development of the political forces that empower the political relations, because this is functional for those economic relations (as in Figure 3).

Alternatively, if, instead, one attempts merely to develop radically different political forces—ones that are not functional for the economic forces—then the economic forces can be expected to facilitate the introduction or re-introduction of political forces that empower the political relations which stabilise the economic relations, because that is functional for the development of those economic forces (as in Figure 4). For example, if a nation-state A feels threatened by the nuclear weapons possessed by another state (say, B), then A is likely to develop nuclear weapons itself if it has the civil nuclear power programme that would make their development possible.[16] Indeed, should a competitor state B have a civil nuclear power programme, but lack nuclear weapons at this time, state B‘s civil nuclear programme, because it might result in the development of nuclear weapons, would provide strong reason for state A to develop nuclear weapons.

Finally, if one attempts, instead, merely to alter radically the political relations in a direction that is not functional for the political forces, then the political forces can be expected to introduce or re-introduce political relations which stabilise the economic relations that develop certain economic forces, because that is functional for the development and maintenance of those political forces (as in Figure 5).

An environmentally benign interrelationship

Would this render all environmentally benign change impossible? No, but it does indicate that, if we are within such an environmentally hazardous dynamic, any effective solution to the environmental crisis that we face would have to be radical, indeed. For it would seem that the only way to stand a reasonable chance of preventing the functional explanatory components of the dynamic from inhibiting the requisite radical change would be to alter each and every one of them. This is because any remaining element could be expected to attempt to replace a second with one more functional for it, and that second element can be expected in turn to attempt to replace a third with one more functional for it, which can be expected in turn to attempt to replace the fourth with one more functional for that third element. And this suggests that green political theory, as surprising as this might initially seem, would need to be more radical than even traditional Marxist or traditional anarchist theory. Indeed, we might also suspect that revolutions have thus far failed not because of how radical they were, but, rather, because they were not radical enough.

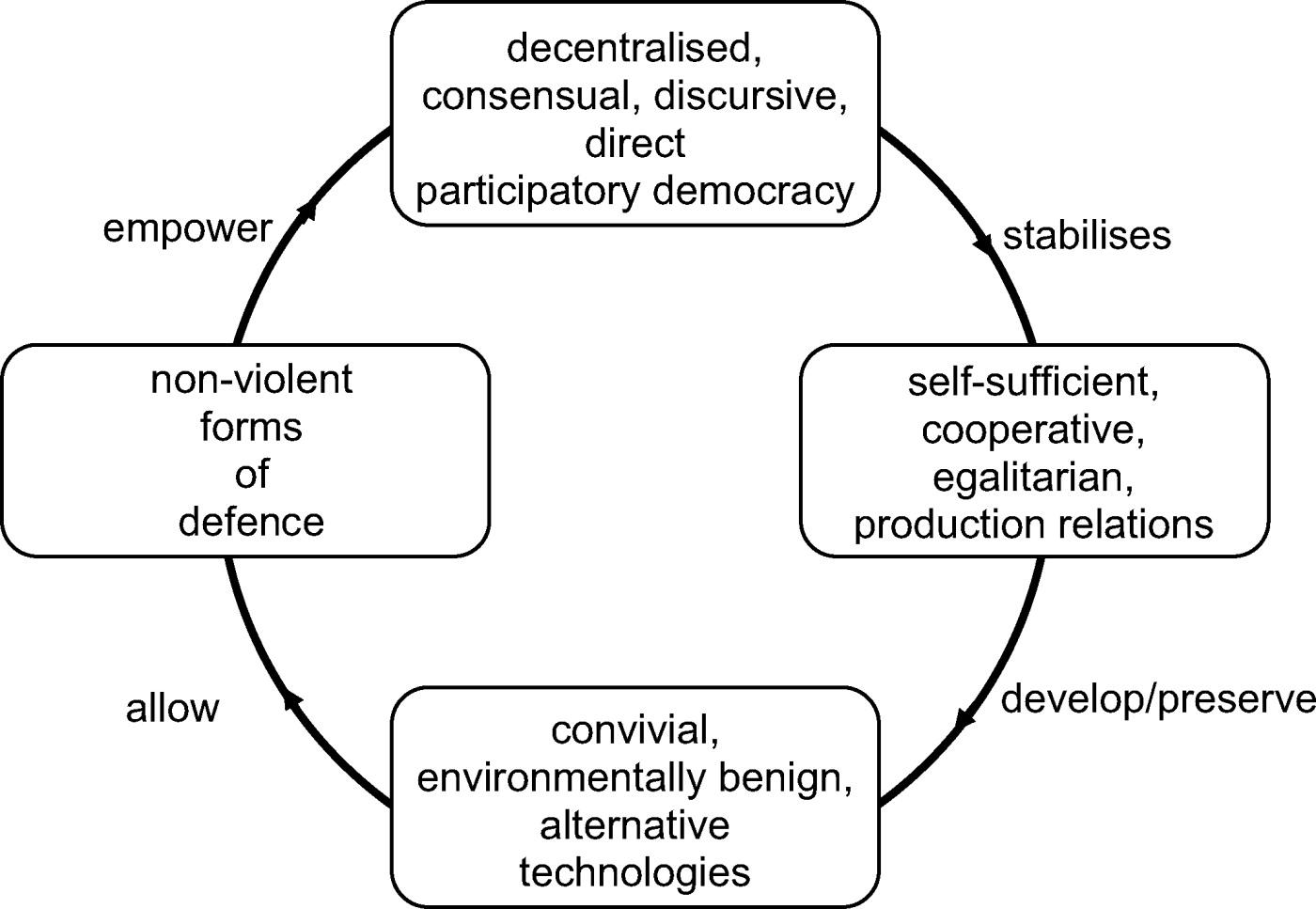

Now, were pseudo-representative, quasi-democratic, centralised, authoritarian power relations to be replaced by a decentralised, consensual, discursive,[17] direct participatory democracy, and were competitive, inegalitarian, exploitative production relations to be replaced by self-sufficient or self-reliant, cooperative, egalitarian production relations under workers’ and community control, and were highly resource-consumptive, environmentally damaging, pollution-emitting technology to be replaced by environmentally benign, convivial, alternative technologies, and were nationalistic, militaristic armed forces to be replaced by non-aggressive social control and nonviolent forms of defence, then, instead of the environmentally hazardous dynamic, we may find an environmentally benign interrelationship[18] ( Figure 8).

Such an interrelationship might be expected to be environmentally benign, because a participatory democracy of this kind would lack the pressing need for nationalistic, militaristic armed forces, and hence competitive, inegalitarian, exploitative production relations would not be functional for such a participatory democracy. The reason for this is that such exploitative production relations are required for highly resource-consumptive, environmentally damaging, pollution-emitting technology to be developed, and that technology is required for such militaristic armed forces to develop further. But without the need for such armed forces, neither they nor such environmentally damaging technology nor such exploitative production relations are functional for such a participatory democracy. (This is not, of course, to say that a decentralised, consensual, discursive, direct participatory democracy is sufficient for an environmentally benign social order. But it does strongly suggest that it might well be necessary for one.)

Moreover, such egalitarian production relations under workers’ and community control would have no need for pseudo-representative, quasi-democratic, centralised, authoritarian power relations, and hence highly resource-consumptive, environmentally damaging, pollution-emitting technology would not be functional for those egalitarian economic relations. Such environmentally damaging technology is required for militaristic armed forces to develop further, and those coercive forces are required to preserve such authoritarian power relations. But without any need for those authoritarian power relations, neither they nor such militaristic armed forces nor such environmentally damaging technology would be functional for self-sufficient or self-reliant, cooperative, egalitarian production relations under workers’ and community control.

Furthermore, the preservation[19] of environmentally benign, convivial, alternative technologies has no need of competitive, inegalitarian, exploitativeproduction relations. Hence, it has no need for nationalistic, militaristic armed forces or for the pseudo-representative, quasi-democratic, centralised, authoritarian power relations they preserve, which in turn stabilise such exploitative production relations. Neither such exploitative production relations nor such militaristic armed forces nor such authoritarian power relations are functional for the preservation of environmentally benign, convivial, alternative technologies.

In addition, non-aggressive social control and nonviolent forms of defence have no need for the highly resource-consumptive, environmentally damaging, pollution-emitting technology that is needed for nationalistic, militaristic armed forces; hence non-aggressive social control and nonviolent forms of defence have no need for competitive, inegalitarian, exploitative production relations to sustain and further develop such environmentally damaging technology. Consequently, non-aggressive social control and nonviolent forms of defence do not require pseudo-representative, quasi-democratic, centralised, authoritarian power relations to stabilise such exploitative production relations. Thus, neither such authoritarian power relations nor such exploitative production relations nor such environmentally damaging technology are functional for non-aggressive social control and nonviolent forms of defence.

The fundamental problem is that if we have, in fact, succeeded in identifying the core elements of any environmentally benign society, then none of them would be selected by any element, or combination of elements, within an environmentally hazardous dynamic. The multiplex model mooted here does not, of course, presume that each element of any such dynamic is inherently stable in the long run. For it would lead us to expect the economic relations to change if, in facilitating greater economic development, that would be functional for the other elements. And it would also lead us to expect the economic forces to change if, in being more productive, that would be functional for the rest of the dynamic. Further, it would lead us to expect the political forces to change if, in better empowering the political relations, that would be functional for the other elements. And it would, moreover, lead us to expect the political relations to change if that would be more conducive to stabilising certain economic relations, and was, thereby, functional for the rest of the dynamic. Tragically, because of what would be functional for the majority of the dynamic’s component elements, epochal transformations would, on this theory, be expected to consist in developments of new forces and relations that constitute new forms of authoritarian, centralised, inegalitarian and environmentally destructive societies.[20]

This means that, if a multiplex theory of this general sort were correct, and if we are presently situated within an environmentally hazardous dynamic, then we should rather expect that dynamic to accelerate than to shift into reverse. Every transformation motivated within the prevailing order that we would have reason to anticipate would take us in the wrong direction: namely, even further away from the environmentally benign.

Concluding remarks

Previously, I have argued that a radical green political theory can be grounded on a state-primacy model (see Carter 1993, pp. 40–45 and p. 56, note 16). Because economistic thinking preponderates, it is not surprising that a political theory with such a grounding should have appeared wholly implausible to some.[21] However, as should now be clear, a state-primacy theory is not, in fact, a necessary grounding for the modelling of an environmentally hazardous dynamic; for we have seen that a multiplex theory can equally ground it. Thus, because a state-primacy model is unnecessary for grounding a radical green political theory, such a theory is not dependent upon the acceptance of any such model. Consequently, an opposition to state-primacy theory is no reason for rejecting the radical green political theory sketched here. Furthermore, if one doubts that the elements of the environmentally hazardous dynamic obtain in today’s world, then one could accept a multiplex model without being committed to the radical green political theory that it might otherwise be thought to ground.

This notwithstanding, many will recognise the elements of the environmentally hazardous dynamic at play in today’s world. And while the above has merely constituted the briefest of adumbrations,[22] hopefully it will suffice to show how a truly radical, green political theory, when it is premised upon a complex of functional explanations, can be seen to transcend both Marxist and anarchist political theory. And it does so in a manner that, surprising as it might initially seem, makes it more radical than both. To be precise, Marxist theory, in focusing on inequalities of economic power, has often served to justify the maintenance of inequalities in political power, at least during the course of the revolution (see Carter 1999b; also see Carter 1994). It is this aspect of Marxist revolutionary praxis that anarchists have most opposed. But in focusing on the exercise of political power, some self-styled anarchists have failed to analyse inequalities in economic power adequately. The radical green political theory proffered here justifies a fundamental opposition to the unequal exercise of both economic and political power, for it enables one to see both economic and political equality as essential prerequisites of an environmentally benign social order.

But to sidestep several objections at once, it should be noted that I have not claimed that all existing societies display all of the features of the environmentally hazardous dynamic to the full. Nor have I claimed that wecan simply move immediately to a fully environmentally benign socialorder. Both are ideal types.[23] And the environmentally hazardous dynamic could be thought to be instantiated in different places to different degrees. If so, the key political, economic, technological and social challenge would be to move progressively from the more hazardous to the more benign.

But would such a move even be possible, never mind likely? One thing is clear: if the above argument is roughly correct, then unless the connections between the elements of the environmentally hazardous dynamic are understood, ineffectual policies and counter-productive political activities will remain preponderant, and they will only serve to distract us from the real task ahead. And it is easy to see how such policies and political activities should have become our staple diet. For those dominant within the political relations have thus far benefited from their roles, as have those working as political forces. Those dominant within the economic relations have undoubtedly benefited. And even those working as economic forces might feel that they have done better than they would otherwise have done had a competing state succeeded in conquering them. So, while it might not have been wholly irrational for societies to have developed in accord with an environmentally hazardous dynamic up until now, the times they are rapidly a-changing. And while it might still be rational for elderly people in dominant positions to conduct business as usual, and while they might be unable to step outside of the old paradigms that constrain their thinking, if we are presently located within an environmentally hazardous dynamic, given the environmental crises before us, then it would now be highly irrational for the vast majority of us to remain entrapped there. But a precondition for escape would be to understand that dynamic’s complex nature.

So, by way of conclusion, if we are entrapped within an environmentally hazardous dynamic, and if, therefore, the only genuine, sustainable alternative is the environmentally benign interrelationship, then if one is to be an effective democrat, one also needs to be a decentralist, and if one is to be an effective decentralist, one also needs to be an egalitarian. Moreover, if one is to be an effective egalitarian, one also needs to be a promoter of convivial, alternative technologies. In addition, if one is to be an effective promoter of convivial, alternative technologies, one also needs to be a pacifist. And if one is to be an effective pacifist, one also needs to be an advocate of direct, participatory, discursive democracy. In a word, if the above argument is by and large correct, then whether one is a democrat, a decentralist, an egalitarian, a promoter of alternative technology or a pacifist, one has reason to strive for all of the components of the environmentally benign interrelationship. Put another way, democracy, decentralisation, equality, alternative technology and non-violence come packaged together or not at all.

References

Arblaster, A. 1987. Democracy, Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Bakunin, M. 1973. “Bakunin on anarchy”. Edited by: Dolgoff, S. London: Allen and Unwin.

Barry, J. 1999. Rethinking green politics: nature, virtue and progress, London: Sage. Bookchin, M. 1982. The ecology of freedom: the emergence and dissolution of hierarchy, Palo Alto, CA: Cheshire Books.

Carter, A. 1988. Marx: a radical critique, Brighton: Wheatsheaf Books.

Carter, A. 1992. “Functional explanation and the state”. In Marx’s theory of history: the contemporary debate, Edited by: Wetherly, P. 205–228. Aldershot: Avebury.

Carter, A. 1993. “Towards a green political theory”. In The politics of nature: explorations in green political theory, Edited by: Dobson, A. and Lucardie, P. 39–62. London: Routledge.

Carter, A. 1994. Marxism/Leninism: the science of the proletariat?. Studies in Marxism, 1: 125–141.

Carter, A. 1995. The nation-state and underdevelopment. Third World Quarterly, 16(4): 595–618.

Carter, A. 1998. Fettering, development and revolution. The Heythrop Journal, 39(2): 170–188. Carter, A. 1999a. A radical green political theory, London and New York: Routledge.

Carter, A. 1999b. The real politics of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. Studies in Marxism, 6: 1–30.

Carter, A. 2000. Analytical anarchism: some conceptual foundations. Political Theory, 28(2): 230–253.

Cohen, G. A. 1978. Karl Marx’s theory of history: a defence, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Dryzek, J. 1990. Green reason: communicative ethics for the biosphere. Environmental Ethics, 12(3): 195–210.

Dryzek, J. 1992. Ecology and discursive democracy: beyond liberal capitalism and the administrative state. Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 3(2): 18–42.

Dryzek, J. 1997. The politics of the earth: environmental discourses, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Engels, F. 1976. Anti-Dühring: Herr Eugen Dühring’s revolution in science, Peking: Foreign Languages Press.

Engels, F. 1989. “Letter to Theodor Cuno, 24th January, 1872”. In Collected works, Edited by: Marx, K. and Engels, F. 305–311. Moscow: Progress.

Graham, K. 1986. The battle of democracy: conflict, consensus and the individual, Brighton: Wheatsheaf Books.

Hailwood, S. 2004. How to be a green liberal: nature, value and liberal philosophy, Chesham: Acumen.

Huntington, S. P. 1968. Political order in changing societies, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lenin, V. I. 1970. The immediate tasks of the soviet government, Moscow: Progress.

Marx, K. 1974. “Provisional rules”. In K. Marx, The first international and after, Edited by: Fernbach, D. 82–84. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Marx, K. 2000a. “Critical remarks on the article ‘The King of Prussia and social reform’”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 134–137. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. 2000b. “Letter to Annenkov”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 209–211. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. 2000c. “On the Jewish question”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 46–69. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. 2000d. “Preface to A critique of political economy”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 424–427. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. 2000e. Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. 2000f. “The class struggles in France”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 313–324. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. 2000g. “The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 329–354. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. 2000h. “The poverty of philosophy”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 212–233. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. 2000i. “Theses on Feuerbach”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 171–173. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. 2000j. “Towards a critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of right: introduction”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 71–82. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. 2000k. “Wage labor and capital”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 273–293. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marx, K. and Engels, F. 2000b. “The Communist manifesto”. In K. Marx, Selected writings, Edited by: McLellan, D. 245–271. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Connor, J. 1998. “Capitalism, nature, socialism: a theoretical introduction”. In Debating the earth: the environmental politics reader, Edited by: Dryzek, J. and Schlosberg, D. 438–457. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Singer, P. 1973. Democracy and disobedience, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Skocpol, T. 1979. States and social revolutions: a comparative analysis of France, Russia and China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, M. 1989. Structure, culture and action in the explanation of social change. Politics and Society, 17(1): 115–162.

[1] For a discussion of this form of explanation, see Carter (1992).

[2] This view of the state is not peculiar to Engels, for it echoes what he and Marx hadjointly written over a quarter of a century earlier. See Marx and Engels (2000a, p. 200).

[3] The division at one level leading to the need for unity at a higher level directly mirrors Marx’s Feuerbachian analysis of religious alienation, of course.

[4] For a critical analysis of Marx’s theory of the state, see Carter (1988, ch. 5).

[5] As an explanation for the rise of the modern state, this might well be doubted. For some might argue, instead, that modern states appear, in many cases, to be more the result of (often far earlier) conquest.

[6] See Carter (2000).

[7] And, ordinarily, modern states do find themselves situated within an international structure of competing states. See Skocpol (1979, pp. 30–32).

[8] And it finds support in Michael Taylor’s contention that it was state actors who selected new economic relations in France from the fifteenth century and in Russia from the eighteenth century. Moreover, this was, argues Taylor, because of their need to obtain increased tax revenue as a result of ‘geopolitical-military competition.’ See Taylor (1989), especially, pp. 124–126 and 128–132. Also see Huntington (1968, pp. 122 and 126). Even Marx agrees that the state ‘helped to hasten’ within France ‘the decay of the feudal system.’ See Marx (2000g, p. 345).

[9] Such an anarchist model is also at no disadvantage in explaining underdevelopment in poor countries. And there is reason for thinking that it provides a superior account to that provided by the Marxist model. See Carter (1995).

[10] Clearly, the state needs subordinate classes to be kept at work in order to produce the wealth it must tax if it is to pay its personnel. See Skocpol (1979, p. 30). Hence, it can be argued that the state has its own interest in maintaining exploitative economic relations, and therefore it cannot simply be reduced to the instrument of a class. Rather, state and bourgeois interests ordinarily contingently correspond.

[11] In having four component functional explanatory elements, we might call this ‘a quadruplex model.’ However there is nothing, in principle, preventing us from adding further components, such as a functional explanation of ideology.

[12] For such an eco-anarchist theory, see Carter (1993, 1999a).

[13] For an indication of the extent to which the term ‘democracy’ has been usurped by those opposed to genuine democracy, see Arblaster (1987). Also see Graham (1986). For an indication of how undemocratic and illegitimate are contemporary societies, see Singer (1973).

[14] Note that all this is neutral with respect to the debate between explanatory collectivists and methodological individualists. On a structuralist reading of the above four functional explanations, the relations and forces would be construed as ‘making selections.’ But on a more methodological individualist reading, rational actors would be construed as engaged in the selecting. Moreover, on either approach, it is possible to tell a Darwinian story regarding which ‘selections’ survive. For one possible Darwinian mechanism, see Carter (1999a, §4.3.1.1).

[15] See Carter (1993).

[16] We would also expect two nuclear-armed states to pose such a threat to each other that they will both be compulsively driven to do what is necessary economically in order to remain militarily competitive.

[17] On discursive democracy and its appropriateness for environmentalism, see Dryzek (1990, 1992).

[18] See Carter (1993). For classic discussions of decentralisation, direct participatory democracy, convivial and alternative technologies, and non-violence, see the references in ibid.

[19] ‘Preservation’ rather than ‘development’ because the environmentally benign interrelationship, once in place, could be expected to constitute a relatively stationary order, not a dynamic en route to oblivion.

[20] Such a complex of functional explanations should therefore not be confused with structural functionalism. The latter is a theory focusing upon why societies tend to remain unchanged, while Cohen’s theory, the state-primacy theory, and the multiplex theory are each offered as an explanation of epochal change from one set of production relations to another.

[21] Though it is telling how little attention green liberal critics of the state-primacy theory have paid to the role of the military and to its highly distorting effects. Failing to examine in any detail military requirements within ostensibly ‘liberal democracies,’ whether existing or imagined, is more like simply ignoring an argument rather than answering it. See, for example, Barry (1999) and Hailwood (2004).

[22] Support for many of the claims made here, and answers to a number of possible objections to those claims, can be found in Carter (1999a, passim). Although the argument there rests on a state-primacy theory, many of the rebuttals of objections to such a theory constitute equally effective responses to objections to the multiplex theory sketched here.

[23] Although several pre-literate tribal peoples have displayed the features of the environmentally benign interrelationship; and they also managed to survive for a very long time compared to the short-lived, self-destructive societies of our day.