ISSN 1469–9613 online/11/030245–20 q 2011 Taylor & Francis.

Alan Carter

Anarchism

some theoretical foundations

Abstract

This article considers two different, yet related, theoretical approaches that could be employed to ground the anarchist critique of Marxist- Leninist revolutionary practice, and thus of the state in general: the State-Primacy Theory and the Quadruplex Theory. The State-Primacy Theory appears to be consistent with several of Bakunin’s claims about the state. However, the Quadruplex Theory might, in fact, turn out to be no less consistent with Bakunin’s claims than the State-Primacy Theory. In addition, the Quadruplex Theory seems no less capable of supporting the anarchist critique of Marxism-Leninism than the State-Primacy Theory. The article concludes by considering two possible refinements that might be made to the Quadruplex Theory

I

Anarchists have, on the whole, been highly critical of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary practice, which has traditionally been willing to employ centralized and authoritarian means in order to bring about a post-capitalist society. [1] In its willingness to employ such means, Marxism-Leninism, of course, explicitly assumes that those means will not adversely shape the form taken by post-capitalism—an assumption that anarchists have consistently rejected. The reason Marxist-Leninists are so seemingly cavalier (at least from an anarchist perspective) in their attitude to post-revolutionary political power is their reliance on Karl Marx’s political theory—in particular, his theory of the state. But if anarchists are to provide a cogent critique of Marxism-Leninism, then they require a compelling political theory of their own in contradistinction to Marxist theory in order to ground that critique. They also require a cogent reason for rejecting Marx’s political theory.

In what follows, I adumbrate two different, yet related, political theories that may suffice to justify the anarchist rejection of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary practice and of the state in general: the State-Primacy Theory and the Quadruplex Theory. In addition, during the course of discussing those theories, a reason will emerge for rejecting Marx’s theory of the state.

II

The most famous anarchist critic of Marx is, without doubt, Mikhail Bakunin. [2] So allow me to begin by noting some of Bakunin’s arguments that are either direct or implied criticisms of Marx and his collaborator Friedrich Engels—fellow revolutionary figures whom Bakunin judged to be potentially authoritarian, centralist and elitist—for those criticisms can readily be deployed to target Marxist-Leninist revolutionary practice.

Now, it is worth observing first of all that, although Marx and Bakunin shared a similar ideal of an egalitarian post-capitalist society, there are certainly grounds for Bakunin’s suspicions regarding Marx’s and Engels’ authoritarianism, centralism and elitism, especially regarding the process of revolutionary transformation. For example, with respect to the Paris Commune, in a draft of a letter that Engels wrote to Carlo Terzaghi, he writes:

If there had been a little more authority and centralization in the Paris Commune, it would have triumphed over the bourgeoisie. After the victory we can organize ourselves as we like, but for the struggle it seems to me necessary to collect all our forces into a single band and direct them on the same point of attack. And when people tell me that this cannot be done without authority and centralization, and that these are two things to be condemned outright, it seems to me that those who talk like this either do not know what a revolution is, or are revolutionaries in name only. [3]

Engels’ lament, here, for what he clearly perceived to be a lack of authority and centralization within the course of a potentially revolutionary transformation of society assumes, of course, that such authority and centralization would pose no substantial political problems after the hoped-for revolution. But as Bakunin acutely asks: ‘Has it ever been witnessed in history that a political body ... committed suicide, or sacrificed the least of its interests and so-called rights for the love of justice and liberty?’ [4] In short, can it safely be assumed that those enjoying centralized and authoritarian power will simply relinquish it?

Moreover, Marx and Engels professed that their variety of socialism was scientific, rather than utopian. [5] Unfortunately, in Bakunin’s view:

A scientific body to which had been confided the government of society would soon end by devoting itself no longer to science at all, but to quite another affair; and that affair, as in the case of all established powers, would be its own eternal perpetuation by rendering the society confided to its care ever more stupid and consequently more in need of its government and direction. [6]

Yet, as Marx makes clear in his marginal notes to Bakunin’s Statism and Anarchy, the dictatorship of the proletariat, which Marx and Engels predicted and advocated, would utilize a form of centralized governmental power. [7] Bakunin, in contrast, regards any assumption that a centralized government would hand power to the masses after a revolution as itself highly utopian.

Furthermore, Marx quite clearly believed that he knew where the interests of the working class lay better than the working class itself, for as he explicitly admitted in 1850:

I have always defied the momentary opinions of the proletariat. If the best a party can do is just fail to seize power, then we repudiate it. If the proletariat could gain control of the government the measures it would introduce would be those of the petty bourgeoisie and not those appropriate to the proletariat. Our party can only gain power when the situation allows it to put its own measures into practice. [8]

Given such seeming elitism, it is hardly surprising, therefore, that Bakunin should observe:

it is clear why the dictatorial revolutionists, who aim to overthrow the existing powers and social structures in order to erect upon their ruins their own dictatorship, never are or will be the enemies of government, but, on the contrary, always will be the most ardent promoters of the government idea. They are the enemies only of contemporary governments, because they wish to replace them. They are the enemies of the present governmental structure, because it excludes the possibility of their dictatorship. At the same time they are the most devoted friends of governmental power. For if the revolution destroyed this power by actually freeing the masses, it would deprive this pseudo-revolutionary minority of any hope to harness the masses in order to make them the beneficiaries of their own government policy. [9]

What is more, according to Bakunin:

men who were democrats and rebels of the reddest variety when they were a part of the mass of governed people, became exceedingly moderate when they rose to power. Usually these backslidings are attributed to treason. That, however, is an erroneous idea; they have for their main cause the change of position and perspective. [10]

However, there is an alternative, or a supplementary, explanation that could be mooted to account for this phenomenon. Hierarchical state structures might be such that only those who are, at least to some degree, ruthless in their striving for political power will eventually succeed in attaining it or in retaining that power.

But what is most important for our present concern is that Bakunin’s disagreement with Marx and Engels was fundamentally theoretical in nature. Marx tended to reduce political power to the power of an economic class—the dominant class—which is partly why he referred to it as the ruling class. [11] For example, in The Communist Manifesto, Marx confidently declares that ‘[p]olitical power, properly so called, is merely the organized power of one class for oppressing another’, [12] thereby deducing that

[i]f the proletariat during its contest with the bourgeoisie is compelled, by the force of circumstances, to organize itself as a class, if, by means of a revolution, it makes itself the ruling class, and, as such, sweeps away by force the old conditions of production, then it will, along with these conditions, have swept away the conditions for the existence of class antagonisms and classes generally, and will thereby have abolished its own supremacy as a class. [13]

And from this, Marx concludes that, with the establishment of a communist economic structure, ‘[i]n place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all’. [14] In a nutshell, the crucial implication of Marx’s conceptualization of political power is that once an egalitarian economic structure has arisen, all problems of political power will vanish. [15]

Later, we shall see that there seems to be historical evidence for holding Marx’s theory of the state to be woefully inadequate at this point. Bakunin, clearly, viewed acting on such a theoretical presumption as being fraught with danger; for reducing political power to economic power is to disregard the highly significant

and malign influence that the state can assert. As he writes:

To support his programme for the conquest of political power, Marx has a very special theory, which is but the logical consequence of [his] whole system. He holds that the political condition of each country is always the product and the faithful expression of its economic situation; to change the former it is necessary only to transform the latter. Therein lies the whole secret of historical evolution according to Marx. He takes no account of other factors in history, such as the ever-present reaction of political, juridical, and religious institutions on the economic situation. He says: ‘Poverty produces political slavery, the State’. But he does not allow this expression to be turned around, to say: ‘Political slavery, the State, reproduces in its turn, and maintains poverty as a condition for its own existence; so that to destroy poverty, it is necessary to destroy the State’! And strangely enough, Marx, who forbids his disciples to consider political slavery, the State, as a real cause of poverty, commands his disciples in the Social Democratic party to consider the conquest of political power as the absolutely necessary preliminary condition for economic emancipation. [16]

Bakunin is certainly being uncharitable in caricaturing Marx as taking no account of other historical factors, ‘such as the ever-present reaction of political, juridical, and religious institutions on the economic situation’. This notwithstanding, Bakunin offers a very interesting suggestion here, namely that ‘[p]olitical slavery, the State, reproduces ... and maintains poverty as a condition for its own existence’, for such a claim sounds very much like a functional explanation. In other words, Bakunin appears to be arguing that states choose economic inequality because it serves their interests—in short, because it is functional for them. This is especially interesting insofar as the most sophisticated defender of Marx’s theory of history—G. A. Cohen—found it necessary to deploy functional explanations in order to present Marx’s theory in a non–self-contradictory form. [17] And given that, with today’s hindsight, we can see how prescient were Bakunin’s observations regarding the course of an authoritarian revolution, it would surely be odd to see no merit whatsoever in his political theory.

III

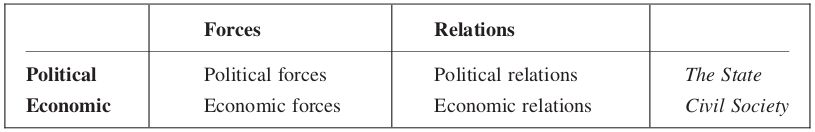

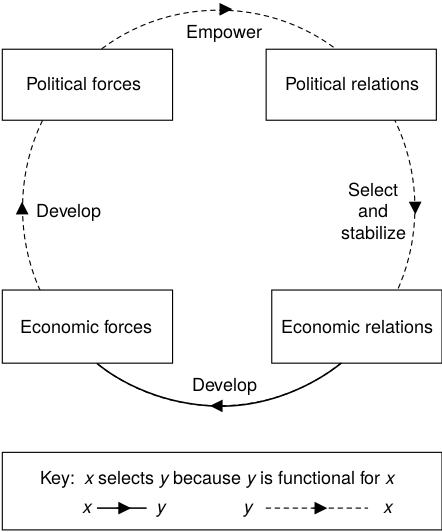

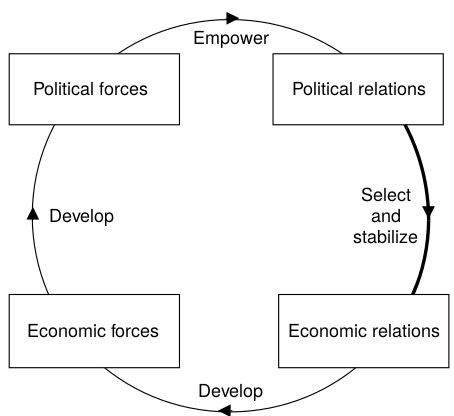

In order to develop Bakunin’s suggestion further, let us distinguish between, on the one hand, political and economic categories, and, on the other, between forces, and relations. From this pair of distinctions, we can derive four components of a modern society that can be combined to form a complex functional explanation. The four components are: the political forces, the political relations, the economic forces, and the economic relations (Table 1). The political forces and political relations together comprise the state, whereas the economic forces and economic relations together comprise what has, since Hegel’s time, been traditionally referred to as civil society.

Table 1. The state and civil society.

Following Cohen’s lead, we can define the economic structure of a society as consisting of the set of its economic relations; and we can specify those relations as comprising relations of, or relations presupposing, effective control over production. Such relations of production can be defined as relations of, or as relations that presuppose, effective control of the forces of production. These economic forces—the forces of production—can be defined as comprising economic labour-power (that capacity which the agents of production supply in return for wages) and the means of production (e.g. tools and machinery). We might also find it advantageous to go beyond the majority of Marxist theorists by including within the set of economic relations those relations of, or presupposing, effective control over economic exchange. [18]

Given that, at least in modern societies, the ability to control effectively the economic forces depends, in part, on the accepted legality of the economic relations and, perhaps even more importantly, on the ability of the political forces to preserve them, control of the forces of production requires relations of, or relations presupposing, political power—in short, political relations. We might then define the political structure of a society as consisting of the set of its political relations. And the relevant aspects of political power might be argued to include: the power to introduce legislation, especially legislation that is viewed by a sufficient number of people as legitimate; the power to enforce that legislation; and the power to defend the political community against external threats. [19]

These political relations are embodied in the various legal and political institutions of a society. To be more specific, political institutions comprise relations of, or relations presupposing, effective control of the society’s ‘defensive’ forces. In the modern state, these forces of ‘defence’ (which are usually more offensive than defensive) take a coercive form—such coercive forces comprising political labour-power (that capacity which the agents of coercion supply, namely the work offered by policemen and policewomen, military personnel, etc., in return for wages) and the means of coercion (e.g. weaponry and prisons). And political labour-power and the means of coercion together constitute a society’s political forces. [20]

Before fitting the political forces, the political relations, the economic forces and the economic relations into a complex functional explanation, we need to be clear about the nature of functional explanations. According to Cohen, [21] functional explanations are a subset of consequence explanations; and consequence explanations are justified by consequence laws. Consequence laws take the form:

(1) If (if Y at t1 , then X at t2 ), then Y at t3 ,

where ‘X’ and ‘Y’ are types of events, and where ‘t1 ’ is some time not later than t2, and where ‘t2’ is some time not later than time t3 . A consequence explanation such as

(2) b at t3 because (a at t2 because b at t1),

where ‘b’ is a token of type Y, and ‘a’ is a token of type X, is justified by (1). And if b is functional for a, then (2) is a functional explanation.

So, consider the following consequence law:

(3) If it is the case that if predators were to develop better camouflage then they would be able to hunt better, then they would come to develop better camouflage.

This would justify the following consequence explanation:

(4) Tigers developed stripes because they were better hunters as a result of having stripes.

Given that having stripes that provide better camouflage is functional for better hunting, (4) is a functional explanation.

Now, a consequence law such as (3) might seem implausible on its own. But with the addition of some elaboration it becomes extremely plausible. For if we add a theory of natural selection, where those most fitted to survive within their environment are the ones naturally selected, as well as adding a theory of genetics that allows chance variation, then something like the following story can be told: Due to chance variation, tigers will have some offspring that are better camouflaged than others. Those with better camouflage will be better hunters. And those that are better hunters will, because of competition for food, be the ones that tend to survive and have offspring, some of whom, due to chance variation, being better camouflaged than their parents and some having poorer camouflage. Those with even better camouflage than their parents will be even better hunters, and so on. In short, over time, tigers will become better camouflaged because better camouflage is functional for being a more successful hunter.

So, now consider this complex consequence law:

(5) If it is the case that if the political relations were to select economic relations that better develop the economic forces that better develop the political forces that better empower the political relations, then those economic relations would come to be selected.

This would justify the following consequence explanation:

(6) A particular set of economic relations was selected because the political

relations were better empowered as a result of having such economic

relations.

Given that having economic relations that better develop the economic forces that better develop the political forces that better empower the political relations is functional for the political relations, (6) is a functional explanation. Moreover, (5) could be elaborated by reference to the fact that states ordinarily exist within a world of competing states. [22] Because novel weaponry—a political force—is occasionally invented, those states that develop better weaponry will tend to be the ones that survive. But in order to develop better weaponry, a more productive economy is required. Hence, those states that tend to survive will be ones where their political relations selected economic relations that better developed the economic forces that better developed the political forces. The mooted revolutionary process from one epoch to another whereby political relations select new economic relations that develop the economic forces that develop the political forces that empower the political relations is represented in Figure 1. Figure 1 also models the stabilization of the economic relations by the political relations within an epoch because, in developing the economic forces that are required to

develop the political forces that empower the political relations, those economic relations are, at that time, functional for the political relations. It is when the prevailing economic relations become dysfunctional for the political relations that new economic relations are selected. But while they remain functional for the political relations, the prevailing economic relations are stabilized.

Figure 1. A State-Primacy Model.

Now, when the political relations display political inequality, as they ordinarily do, and when the economic relations also display economic inequality, as they, too, ordinarily do, then this can be hyperbolically described as a case where ‘[p]olitical slavery, the State, reproduces ... and maintains poverty as a condition for its own existence; so that to destroy poverty, it is necessary to destroy the State’. The complex functional explanation modelled in Figure 1 could thus be regarded as explicating Bakunin’s very interesting suggestion. And the terminological clarifications supplied above could be regarded as filling in the requisite detail to make adequate sense of the model. Call the political theory thus modelled—the theory, that is, which claims that political relations select and/or stabilize economic relations that develop the economic forces that develop the political forces that empower the political relations, because that is functional for the political relations—‘the State-Primacy Theory’. [23]

IV

But does the State-Primacy Theory actually provide a plausible explanation of epochal transitions? Well, consider the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Robert Brenner has pointed to the growing need of feudal political relations to develop their political forces. As he observes:

In view of the difficulty, in the presence of pre-capitalist property relations, of raising returns from investment in the means of production (via increases in productive efficiency), the lords found that if they wished to increase their income, they had little choice but to do so by redistributing wealth and income away from their peasants or from other members of the exploiting class. This meant they had to deploy their resources towards building up their means of coercion by investment in military men and equipment. Speaking broadly, they were obliged to invest in their politico-military apparatuses. To the extent they had to do this effectively enough to compete with other lords who were doing the same thing, they would have had to maximize both their military investments and the efficiency of these investments. They would have had, in fact, to attempt, continually and systematically, to improve their methods of war. Indeed, we can say the drive to political accumulation, to state building, is the pre-capitalist analogue to the capitalist drive to accumulate capital. [24]

And as Samuel Finer writes:

Military forces call for men, materials, and, once monetization has set in, for money, too. To extract these has often been very difficult. It has become easier and more generally acceptable as the centuries have rolled on .... Troops extract the taxes or the forage or the carts, and this contribution keeps them in being. More troops—more extraction—more troops: so a cycle of this kind could go on widening and deepening. [25]

And we might conjecture that when the state’s coercive capacity had been developed to a sufficient degree, the political relations would have been able to secure the capitalist economic relations that succeeded feudalism. Moreover, given the greater productivity of capitalism, it would be more functional for the political relations than the preceding feudal economic relations. [26]

In a similar vein, Samuel Huntington observes with respect to European history that

[t]he prevalence of war directly promoted political modernization. Competition forced the monarchs to build their military strength. The creation of military strength required national unity, the suppression of regional and religious dissidents, the expansion of armies and bureaucracies, and a major increase in state revenues. [27]

In a word: ‘War is the great stimulus to state building .... The need for security and the desire for expansion prompted the monarchs to develop their military establishments, and the achievement of this goal required them to centralize and to rationalize their political machinery’. [28] But this required new economic relations—more productive ones—in order that state revenues could be increased. So, as Huntington notes:

The centralization of power was necessary to smash the old order, break down the privileges and restraints of feudalism, and free the way for the rise of new social groups and the development of new economic activities. In some degree a coincidence of interest ... exist[ed] between the absolute monarchs and the rising middle classes. [29]

Now, as the selection and then preservation of new economic relations that offered greater revenue to the state would also serve the interests of whichever class most benefited from the new economic relations, there would be a correspondence of interests between what would become the new dominant class and those occupying dominant positions within the political relations. But that would not make a dominant economic class a ruling class. Rather, the contingent correspondence between state interests and those of any dominant economic class is the reason why that class has the appearance of being a ruling class. Importantly, the fact that states can act so as to facilitate the rise of a new class that better serves state interests shows the notion of a ‘ruling class’ to be misguided.

But even more interesting, perhaps, than the transition from pre-capitalism to capitalism is the transition from capitalism to post-capitalism. Recall the theoretical dispute between Marx and Bakunin, outlined in Section II, above. Engels characterizes the disagreement as follows:

Bakunin ... does not regard capital, and hence the class antagonism between capitalists and wage workers which has arisen through the development of society, as the main evil to be abolished, but instead the state. While the great mass of the Social-Democratic workers hold our view that state power is nothing more than the organization with which the ruling classes—landowners and capitalists—have provided themselves in order to protect their social privileges, Bakunin maintains that the state has created capital, that the capitalist has his capital only by the grace of the state. And since the state is the chief evil, the state above all must be abolished; then capital will go to hell of itself. We, on the contrary, say: abolish capital, the appropriation of all the means of production by the few, and the state will fall of itself. The difference is an essential one: the abolition of the state is nonsense without a social revolution beforehand; the abolition of capital is the social revolution and involves a change in the whole mode of production. [30]

In other words, the introduction of egalitarian economic relations will ostensibly suffice for problematic political relations to disappear, which is precisely what we would expect Engels to argue, given the theoretical difference between Bakunin and Marx. But the disappearance of problematic political relations following the introduction of egalitarian economic relations is certainly not what happened in the 1917 Russian Revolution. But this is not because egalitarian economic relations failed to arise. For they did: a form of egalitarian economic relations was introduced in 1917 when the workers set up their own factory committees. But after Lenin seized power late that year, he replaced those committees with ‘one-man management’. And in 1918 he explained why: ‘All our efforts must be exerted to the utmost to ... bring about an economic revival, without which a real increase in our country’s defence potential is inconceivable’. [31] In other words, the political relations selected inegalitarian economic relations (shaped by Lenin’s personal admiration for Taylorism) that developed the economic forces so as to develop the political forces, because that was functional for the political relations. But this is precisely what the State-Primacy Theory asserts. Moreover, also consistent with the State-Primacy Theory and wholly at odds with Marxist theory, the political relations themselves became increasingly authoritarian. [32]

Ironically, then, an actual historical event that is near-universally regarded as a Marxist revolution, by friend and foe of Marxism alike, seems patently to contradict Marx’s theory of history. And this can only be because of Marx’s inadequate theory of the state. It is far from surprising, therefore, that formerly committed Marxists should have given up on their ‘grand theory’ and embraced postmodernism. But given the explanatory power of the State-Primacy Theory, the relatively recent widespread rejection of theory building was surely premature. For the historical event that has proved so troubling to Marxist political theory simultaneously provides clear corroboration for an alternative, anarchist theory.

V

But does anarchism have to rely on a State-Primacy Theory if its rejection of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary practice is to be adequately grounded? As we have seen, it seems quite possible that the political relations select economic relations that develop the economic forces that develop the political forces, because that is functional for the political relations. But it seems, in principle, possible that, simultaneously, the economic relations develop economic forces that both increase returns to those dominant within the economic relations and develop the political forces that stabilize the political relations, because that is functional for the economic relations insofar as they require those particular political relations for support. Such a theory would incorporate two principal functional explanations. Call a theory that incorporates more than one functional explanation a ‘Multiple-Explanatory Theory’ or ‘Multiplex Theory’ for short. Call a theory that incorporates only two functional explanations a ‘Duplex Theory’. Would such a Duplex Theory provide adequate grounding for the anarchist rejection of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary practice?

It would appear that it would not. For even though inegalitarian political relations might be able to select inegalitarian economic relations that were functional for those particular political relations, if egalitarian economic relations were able to select political relations that were functional for them, then Marxist –Leninist revolutionary strategy might be justified after all. And this is because egalitarian economic relations might well select egalitarian political relations; and they might do so because they may well not require authoritarian political relations to stabilize them.

So, if such a Duplex Theory will not suffice, let us consider a different Multiplex Theory, for it also seems, in principle, possible that:

-

the political relations select and stabilize economic relations that develop the economic forces that develop the political forces, because that is functional for those political relations (as modelled in Figure 1); while, simultaneously,

-

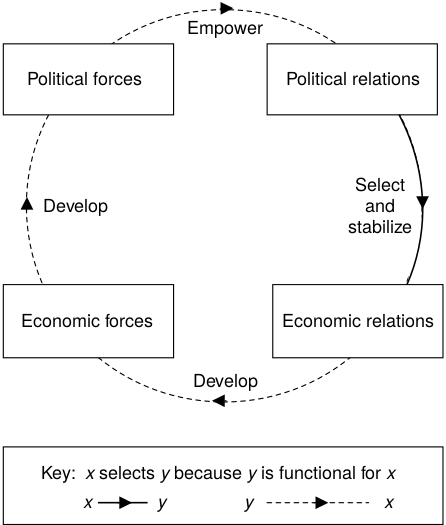

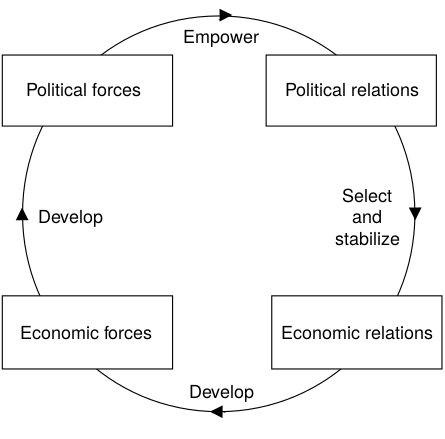

the political forces empower political relations that select and stabilize economic relations that develop the economic forces, because that is functional for the development of those political forces (as modelled in Figure 2); while, simultaneously,

-

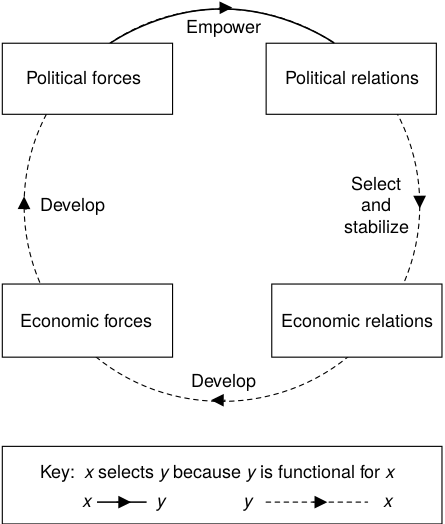

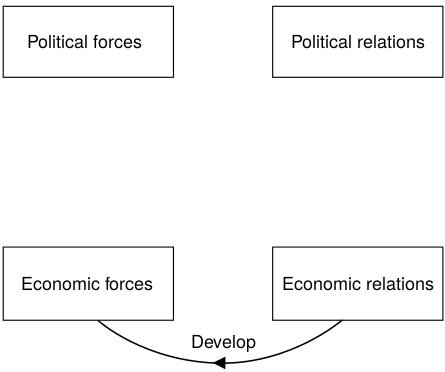

the economic forces develop political forces that empower political relations that select and stabilize certain economic relations, because that is functional for the development of the economic forces (as modelled in Figure 3); and, simultaneously,

-

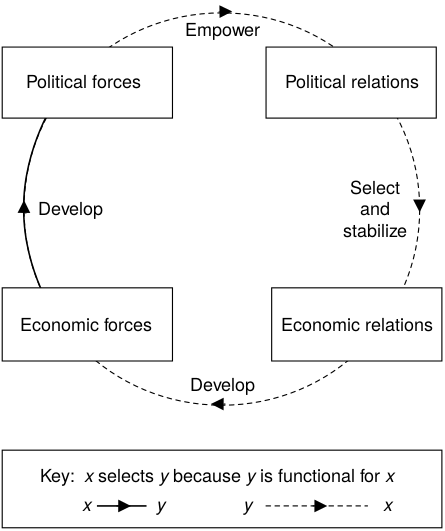

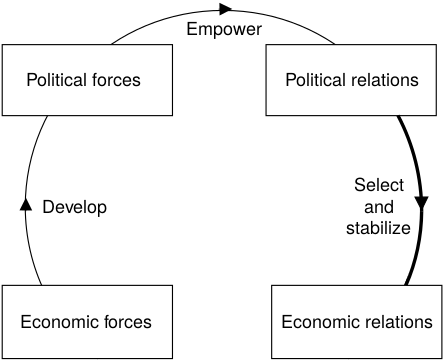

the economic relations develop economic forces that develop the political forces that empower certain political relations, because that is functional for those economic relations (as modelled in Figure 4).

Figure 2. A model emphasizing the explanatory role of the political forces.

Call such a Multiplex Theory containing four functional explanations a ‘Quadruplex Theory’. Such a theory is, at least in its effects, modelled in Figure 5, although it should be remembered that it is built out of the four complex functional explanations modelled in Figures 1 through 4. Would such a Quadruplex Theory provide adequate grounding for the anarchist rejection of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary practice?

Here the answer would appear to be Yes. And this is because, while the economic relations would have some power to develop different economic forces, if those particular economic forces were dysfunctional either for the present political forces or for the present political relations, then they would receive support from neither (as represented in Figure 6). However, if the present political relations were functional for both the present political forces and the present economic forces, then they could expect support from both (as represented Figure 7). In other words, the political relations would likely have more power to transform altered economic relations into those more suited to their requirements than the economic relations would be of transforming the whole social structure. [33]

Figure 3. A model emphasizing the explanatory role of the economic forces.

Figure 4. A model emphasizing the explanatory role of the economic relations.

Figure 5. A Quadruplex Model.

Figure 6. Unsupported economic relations.

In addition, it would take a considerable period of time for the economic relations to develop and introduce new economic forces, whereas the political relations, by enacting a change in legislation, could transform the economic relations relatively quickly. This, too, indicates that the political relations would be more likely to transform effectively any altered economic relations into ones that are more suited to the needs of the political relations than the economic relations would be of transforming the rest of society. Thus, such a Quadruplex Theory provides clear grounding for the anarchist rejection of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary practice, given that if egalitarian economic relations fail to provide sufficient surplus to finance the development of the political forces that empower the political relations, then the political relations will effectively transform those economic relations into inegalitarian ones that would more likely provide sufficient surplus.

Figure 7. Multiply supported political relations.

It should also be noted that Bakunin can not only be interpreted as writing in a manner that is, to some degree, consistent with the State-Primacy Theory but also be interpreted as writing in a manner that is, to some degree, consistent with something like the Quadruplex Theory. For recall that he claims both that ‘[p]overty produces political slavery, the State’ and that the ‘[p]olitical slavery, the State, reproduces in its turn, and maintains poverty as a condition for its own existence’. [34]

VI

All this notwithstanding, there is a refinement that could be made to the Quadruplex Theory that would enable it to provide even stronger grounding for the anarchist rejection of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary practice. Thus far we have only considered a version of the Quadruplex Theory that accords equal weighting to the four component functional explanations (as modelled in Figures 1 through 4) that combine to produce the theory as a whole (whose effects are modelled in Figure 5). But if we had reason for according greater weight to the functional explanation deployed by the State-Primacy Theory (namely that modelled in Figure 1), then we would have even stronger reason for expecting the political relations to play a reactionary role in replacing egalitarian economic relations with inegalitarian ones that were more functional for the political relations than we would have for expecting egalitarian economic relations to succeed in transforming the whole social system into a truly egalitarian one. In short, it seems, in principle, possible that:

-

the political forces tend to empower political relations that select and stabilize economic relations that develop the economic forces, because that is functional for the development of those political forces (as modelled in Figure 2); while, simultaneously,

-

the economic forces tend to develop political forces that empower political relations that select and stabilize certain economic relations, because that is functional for the development of the economic forces (as modelled in Figure 3); while, simultaneously,

-

the economic relations tend to develop economic forces that develop the political forces that empower certain political relations, because that is functional for those economic relations (as modelled in Figure 4); while, simultaneously,

-

the political relations possess the greatest explanatory power within the system in selecting and stabilizing economic relations that develop the economic forces that develop the political forces, because that is functional for those political relations (as modelled in Figure 1).

Call such a complex of functional explanations a ‘Weighted Quadruplex Theory’. (Such a theory is roughly modelled in Figure 8.)

Figure 8. A Weighted Quadruplex Model.

One argument that might be marshalled in support of a Weighted Quadruplex Theory is an argument that also supports the State-Primacy theory—one which we encountered earlier, and which can now be developed further: Even if those holding dominant positions within the political relations were extremely conservative with respect to the economic forces, then, given that states are usually in military competition with other states, they will face considerable pressure to select and then stabilize new economic relations if they would be optimal for providing the state with the revenue it needs to remain militarily competitive. And any state that failed to introduce more productive economic relations would fail to survive against a competitor state that had succeeded in introducing economic relations which, at that period in history, were optimal for providing the state with revenue.

Hence, we can posit a Darwinian-style explanation for political relations selecting economic relations that develop the economic forces that develop the political forces not merely because only those states that, ultimately, succeed in so doing will eventually survive in an environment of competing states but, in addition, because states that are defeated by more militarily successful ones can expect to have their economic relations transformed by the political relations of the conquering state into ones similar to the economic relations selected and stabilized by that state. As this is an outcome that any state will want to avoid at all cost, even the most conservative of state personnel will have an interest in selecting economic relations that are at least as functional for their military requirements as the economic relations of competitor states are for their political relations. In other words, we might think of the functional component within a Quadruplex Theory that the State-Primacy Theory focuses upon exclusively as determining ‘in the last instance’ the shape taken by modern societies.

But we could also provide Darwinian-style explanations for the other three component functional explanations of the Quadruplex Theory. For if the political forces did not empower the right kind of political relations, then economic relations that developed the economic forces that developed those political forces would not be selected and stabilized. And such political forces would then fail to survive as independent entities in a world of competing states. (They may well end up being incorporated into the political forces of a conquering state, for example.) Moreover, if the economic forces did not develop the political forces that empowered the political relations that selected and stabilized economic relations that were functional for the development of the economic forces, then they would not survive in such an environment, either. (For example, they might be replaced by economic forces that were compatible with the requirements of a conquering state). Finally, if the economic relations did not develop the economic forces that developed the political forces that were capable of empowering the political relations, then those political relations would equally fail to survive in a world of competing states. (And they, too, might well be transformed by a conquering state into ones capable of selecting and stabilizing the economic relations that were functional for that conquering state). Thus, the economic relations that would tend to survive are those that are functional for the political relations in a world of competing states.

In a nutshell, the political relations, the economic relations, the economic forces and the political forces that survive will tend to be those that are such that, in the last instance, the political relations select and stabilize economic relations that develop the economic forces that develop the political forces that empower the political relations.

VII

Interestingly, just as strong a support for the anarchist rejection of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary practice could be provided by a Weighted Quadruplex Theory that accorded additional weighting to the political relations only periodically. This would be the case if there were reason to add weighting to the political relations at times of revolutionary transition from one epoch to another, for it is precisely in times of revolutionary transition that Marx believed that egalitarian economic relations would transform the whole social structure. [35] If, during periods of revolutionary transition, the political relations exercised the greatest power within the system in selecting and stabilizing economic relations that develop the economic forces that develop the political forces, because that is functional for those political relations, then egalitarian economic relations that were dysfunctional for the political relations would be unlikely to survive. Call such a complex of functional explanations that accords greatest weight to the political relations during periods of epochal transformation a ‘Temporarily Weighted Quadruplex Theory’. (Such a theory would be roughly represented by switching from Figure 5—roughly modelling stable historical epochs—to Figure 8—roughly modelling revolutionary periods—and back to Figure 5 once the new epoch had been established.)

Now, there are several reasons in favour of a Temporarily Weighted Quadruplex Theory, for according greater weight to the role of the political relations seems most appropriate at times of revolutionary transition than within a stable epoch. Why? Because of some of the ways in which revolutions can be of immense significance not only for the society that is revolutionized but also for neighbouring states.

First, if a country undergoes a popular revolution, then it might succumb to a revolutionary fervour to transform neighbouring countries in a similar fashion. [36] And even if it did not, a neighbouring state might very well fear that a revolutionary state on its borders would invade in order to transform the rest of the world into its own image. Hence, a revolutionary state, simply by its presence, provides reason for neighbouring states to militarize. But once its neighbours militarize, the revolutionary state will, itself, feel threatened, and it, too, will feel compelled to militarize. The development of the political forces will thus become especially crucial during times of revolutionary transition.

Second, even if a state did not fear an actual military invasion from a neighbouring state that had undergone a revolution, it might well still dread that its revolutionary ideals would invade its society. In order to safeguard itself from being infected by the ideals of its revolutionary neighbour, a state might arm insurgents within the revolutionary society, or assist an invasion by émigrés, or directly invade the revolutionary society. [37] This would provoke a revolutionary state to develop its military capacity. Again, we have reason to hold that the development of the political forces will become especially crucial during times of revolutionary transition.

Third, the course of a revolutionary transformation of a state might well leave it temporarily weakened. [38] If this were the case, then this would render a revolutionary state a more attractive target for invasion by its neighbours than it would ordinarily have been. But the fear of invasion by opportunistic neighbouring states would compel a temporarily weakened revolutionary state to develop its military capacity as fast as it could. Yet again, we have reason to hold that the development of the political forces will become especially crucial during times of revolutionary transition.

For reasons such as these, revolutionary transformations are likely to act as a spur to increased militarization, both within and outside the revolutionary state. But any such need to develop the political forces will require the development of the economic forces. But the development of the economic forces requires economic relations that are especially suited to developing them. Given a widely perceived need to develop the political forces at such momentous times, those located within the political forces, the economic forces and the economic relations are likely to be unusually supportive of the political relations selecting economic relations that develop the economic forces that, in turn, develop the political forces. Hence, revolutionary periods might well require that greater weighting be temporarily accorded to one of the four component functional explanations comprising the Quadruplex Theory. But that particular component, namely the one focused upon by the State-Primacy Theory, is precisely the one that best grounds the anarchist critique of Marxist-Leninist revolutionary practice.

VIII

We can thus see that there are at least two related political theories that might well prove to be independently compelling and that could be deployed by an anarchist to ground a cogent critique of Marxism-Leninism. The State-Primacy Theory performs that task well, but so, too, does the Quadruplex Theory, especially when it takes a weighted or a temporarily weighted form. Moreover, given its arguably greater explanatory power, the Quadruplex Theory might well come to command more widespread assent than the State-Primacy Theory.

[1] See, for example, V. I. Lenin, What is to be Done? (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1975) and V. I. Lenin, One Step Forward, Two Steps Back: The Crisis in Our Party (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1976). For a critique, see A. Carter, ‘Marxism/Leninism: the science of the proletariat?’ Studies in Marxism, 1 (1994), pp. 125– 141. On whether or not Marxism-Leninism constitutes a deviation from the politics of Marx and Engels, see A. Carter, ‘The real politics of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels’, Studies in Marxism, 6 (1999), pp. 1 –30.

[2] Bakunin’s politics developed, in part, in response to Marx, while Marx’s political thought developed, in part, as a response to the anarchists Max Stirner, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Bakunin. As Marx’s correspondence with Engels makes abundantly clear, he had a personal antipathy towards Bakunin that bordered on hatred.

[3] Frederick Engels to Carlo Terzaghi, draft written after 6th January 1872, in K. Marx and F. Engels, Collected Works, Vol. 44 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1989), p. 293. Clearly, Engels was not alone in holding this view, for Marx complained that ‘[t]he Central Committee surrendered its power too soon, to make way for the Commune’. Karl Marx to Ludwig Kugelmann, 12th April 1871, in D. McLellan (Ed.) Karl Marx: Selected Writings, 2nd edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 641. For one example of Marx’s authoritarianism, centralism and elitism, see K. Marx, ‘Address to the Communist League’, in McLellan, ibid., especially pp. 305– 311.

[4] M. Bakunin, The Political Philosophy of Bakunin: Scientific Anarchism, ed. G. P. Maximoff (New York: The Free Press, 1964), p. 217.

[5] See K. Marx and F. Engels, ‘The Communist Manifesto’, in McLellan, op. cit., Ref. 3, especially pp. 255– 256, 268–270. Also see F. Engels, Anti-Dühring, Herr Eugen Dühring’s Revolution in Science (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1976).

[6] M. Bakunin, God and the State (New York: Dover, 1970), pp. 31–32.

[7] See K. Marx, ‘On Bakunin’s Statism and Anarchy’, in McLellan, op. cit., Ref. 3.

[8] K. Marx, ‘Speech to the Central Committee of the Communist League’, in McLellan, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 327.

[9] M. Bakunin, Bakunin on Anarchy, ed. S. Dolgoff (London: Allen and Unwin, 1973), p. 329.

[10] Bakunin, op. cit., Ref. 4, p. 218.

[11] And this is why Marx emphasizes that ‘[t]he executive of the modern State is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie’. Marx and Engels, op. cit., Ref. 5, p. 247.

[12] Marx and Engels, ibid., p. 262.

[13] Marx and Engels, ibid. However, it has to be noted that Marx’s view underwent at least some revision later. See ‘The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte’, in McLellan, op. cit., Ref. 3.

[14] Marx and Engels, op. cit., Ref. 5, p. 262.

[15] Thus the end is strikingly different from the means, for as Marx counsels: ‘The workers ... must not only strive for a single and indivisible German republic, but also within this republic for the most determined centralization of power in the hands of the state authority. They must not allow themselves to be misguided by the democratic talk of freedom for the communities, of self-government, etc.’, Marx, ‘Address to the Communist League’, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 310.

[16] Bakunin, op. cit., Ref. 9, pp. 281–282.

[17] See G. A. Cohen, Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defence (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), passim.

[18] Why include control over economic exchange as well as control of production? One reason is that perhaps the most important exploitation today is that between the First World and the Third World. And that does not seem to be adequately theorized in terms of control of production. See A. Carter, ‘Analytical anarchism: some conceptual foundations’, Political Theory, 28(2) (2000), pp. 230 –253, here at p. 251, n. 9.

[19] Carter, ibid., p. 235.

[20] Carter, ibid., pp. 234–235.

[21] See Cohen, op. cit., Ref. 17, Ch. 9.

[22] See T. Skocpol, States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), pp. 30– 32.

[23] For the fullest explication and defence of the State-Primacy Theory, see A. Carter, A Radical Green Political Theory (London: Routledge, 1999).

[24] R. Brenner, ‘The social basis of economic development’, in J. Roemer (Ed.) Analytical Marxism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 32– 33.

[25] S. E. Finer, ‘State- and nation-building in Europe: the role of the military’, in C. Tilly (Ed.) The Formation of National States in Western Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975), p. 96. Also see I. Wallerstein, The Modern World-System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century (New York: Academic Press, 1974), p. 356.

[26] And it is worth noting that Marx himself accepts that the state, during the period of the absolute monarchy, ‘helped to hasten ... the decay of the feudal system’. Marx, ‘The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte’, in McLellan, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 345.

[27] S. P. Huntington, Political Order in Changing Societies (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1968), p. 122.

[28] Huntington, ibid., p. 123.

[29] Huntington, ibid., p. 126. For example, it has been argued that various European monarchies backed the cities (where capitalist economic relations were developing) in order to subvert the power of feudal lords. Put another way, the political relations backed a change in the economic relations because it was in their interests to do so. Moreover, Michael Taylor argues that it was state actors who were responsible for selecting new relations of economic control in France from the 15th century and this was due to their need to obtain increased tax revenue because of ‘geopolitical-military competition’. See M. Taylor, ‘Structure, culture and action in the explanation of social change’, Politics and Society, 17(2) (1989), pp. 115– 162, here at pp. 124–126.

[30] Frederick Engels to Theodor Cuno, 24th January 1872 in Marx and Engels, op. cit., Ref. 3, pp. 306–307. It is worth comparing Engels’ remarks here with the following statement he co-authored with Marx: ‘The material life of individuals, which by no means depends merely on their “will”, their mode of production and form of intercourse, which mutually determine each other—this is the real basis of the State and remains so at all the stages at which division of labour and private property are still necessary, quite independently of the will of individuals. These actual relations are in no way created by the State power; on the contrary they are the power creating it’. K. Marx and F. Engels, ‘The German ideology’, in McLellan, op. cit., Ref. 3, p. 200.

[31] V. I. Lenin, The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1970), p. 6.

[32] See, for example, M. Brinton, The Bolsheviks and Workers’ Control 1917–1921: The State and Counter-Revolution (Detroit, MI: Black and Red, 1975).

[33] See A. Carter, ‘Beyond primacy: Marxism, anarchism and radical green political theory’, Environmental Politics, 19(6) (2010), pp. 951 –972.

[34] Bakunin, op. cit., Ref. 9, pp. 281 –282.

[35] One reason why Marx presumed that egalitarian economic relations would succeed in transforming the rest of society is his belief that ‘the whole of human servitude is involved in the relations of the worker to production, and all relations of servitude are nothing but modifications and consequences of this relation’. K. Marx, ‘Economic and philosophical manuscripts’, in K. Marx, Early Writings, trans. R. Livingstone and G. Benton (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1975), p. 333. Put another way, ‘the economical subjection of the man of labour to the monopolizer of the means of labour, that is, the sources of all life, lies at the bottom of servitude in all its forms, of all social misery, mental degradation, and political dependence’. K. Marx, ‘Provisional rules of the International’, in K. Marx, The First International and After, ed. by D. Fernbach (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974), p. 82. It is also worth recalling at this point Engels to Cuno, 24th January 1872, op. cit., Ref. 30, pp. 306–307.

[36] Possible examples are the periods of the Napoleonic Wars and the rise of fascism.

[37] Candidate examples being Cuba, Nicaragua and Granada, respectively.

[38] Russia immediately following the 1917 Revolution presents itself as an obvious example.