Al Raven

Zapatista Autonomy and Stateless Participatory Democracy

The Zapatista Rebellion in Chiapas

Autonomy as Participatory Democracy from Below

The political organisation of Zapatista autonomy

Part One

This essay was first written in French collaboratively with a friend and fellow student, to which I’m grateful and who accepted for me to translate it into English

‘For us autonomy is the soul and heart of our resistance in our pueblos; it is a new way of doing politics in construction and in development in democracy, justice and liberty.’

~ Macario, a member of the Nueva Revolución community in the municipality of Diecisiete de Noviembre (Chiapas) (quoted in Mora 2017, 72)

Introduction

Since the end of the postwar boom, a range of economic and political factors have transformed Western democracies. With regard to the political system and democracy in particular, citizens’ trust in their leaders has declined, and a sense of mistrust expressed outside political institutions and parties has burgeoned (Chapdelaine 2010, 2). Some of the inherent limitations of representative democracy — including the growing gap between representatives and the represented, the over-centralisation of power, and the disempowerment of citizens — are leading to dissatisfaction with this type of political organisation and a desire to turn to new practices (Hatzfeld 2011). This is why, in recent decades, some groups have increasingly called for forms of ‘participatory’ or ‘deliberative’ democracy to remedy the limited level of participation by the public in most countries (Sintomer & Bacqué 2011, 15–16).

A subset of French political sociology — starting with scholars Pierre Bourdieu and Daniel Gaxie — has argued that one factor in the low democratic participation of dominated groups is ‘structural social inequalities in the face of politicisation’ (Blondiaux 2007, 762), i.e. their ‘social inability to enter into the categories of judgement and expression of opinions imposed by [the political order]’ (Lagroye et al. 2012, 350–351). Individuals ‘experience’ and ‘manifest’ this incompetence, ‘in particular through non-participation in “civic” activities’ (ibid, 348). However, this is ‘not an “absence of opinions,” but rather a sense of incompetence maintained by the socially authorised agents defining the language and schemas of the political’ (ibid, 351). The illegitimacy of taking part in political processes is therefore an individual feeling of incompetence that is also socially recognised.

The scientific literature lacks any consideration of whether, or to what extent, conventional attempts at participatory democracy might be limited by the very fact that they originate in the modern state framework. This framework is based in part on the differentiation between political specialists or professionals and laymen, defined by their inability to intervene according to the codes and patterns of the established political system. As Starr et al. (2011, 103) put it, the research dealing with more inclusive forms of participatory democracy generally views this kind of system as ‘a kind of advisory process to state decision making (…) The forms of “direct,” “deliberative,” and “decentralized” democracy discussed in these works are all ways of participating in the state.’ What happens in contexts where this separation is deconstructed or even abolished?

The Zapatista experience in the state of Chiapas in southern Mexico is an example of popular stateless self-organisation that has lasted for more than twenty-five years. Since the 1990s, and especially since 2003, this experience of democracy from below has persisted despite an unfavourable context, linked in particular to repression by the Mexican state and the violence of paramilitary organisations. Nevertheless, its radical character can be identified by its popular, peasant, and Indigenous base; its project of self-government outside the state; and its internationalist and anti-capitalist demands. The participation of lay citizens is thus a foundation of the Zapatista organisation, directly raising the question of their competence and capacity to organise and manage themselves. As they say in the Sixth Declaration of the Selva Lacandona:

‘This method of autonomous government was not simply invented by the EZLN, but rather it comes from several centuries of indigenous resistance and from the Zapatistas’ own experience. It is the self-governance of the communities. In other words, no one from outside comes to govern, but the peoples themselves decide, among themselves, who governs and how, and, if they do not obey, they are removed. If the one who governs does not obey the people, they pursue them, they are removed from authority, and another comes in.’

In her analysis of the democratic function from the armed uprising of January 1, 1994, to the “Other Campaign,” an initiative for citizen participation at the national level initiated in 2005, Monique Chapdelaine (2010) emphasises the singularity of the movement. Among other things, she examines the Zapatista conception of democracy. The Zapatistas adopt a radical perspective by positioning themselves against the State and advocating new methods of consultation and decision-making, including a diversity of social actors and a total decentralisation of power. According to them, power in a democratic society should be located at the base — that is, in civil society. In total opposition to the current functioning of the Mexican government, the Zapatistas engage in participatory democracy as a part of their political organisation.

According to Sabrina Melenotte (2010), applying the notion of political governance to the practice of Zapatista autonomy allows for the inclusion of new actors in the analysis, and therefore, in civil society. Governance is a system of rules and institutions that implies a reorganisation of power and government (ibid 180). It allows us to think about citizen participation and the possibility of the emergence of organised power on the margins of the state, thanks to the diversity of actors it involves in the practice of power. Consequently, the governance approach makes it possible to link contestation and political reconfigurations through the self-governance of civil society.

Self-governance is the idea that the people are capable of governing themselves outside of a state system. It can be thought of as the outcome of the practice of autonomy, which, according to Jérôme Baschet (2019, 2021), represents the most important characteristic of the Zapatista experience. It is also through this concept that the Zapatistas themselves describe their practices and their modes of political and social organisation. Their emancipation project secedes from the institutions of the state and has relocated its form of self-government to another scale that does not include the state (Baschet 2021, 2).

This approach identifies how Zapatista autonomy operates in the areas of education, health, justice, and government. Their political organisation is characterised by what the Zapatistas call ‘mandar obedeciendo,’ which means ‘the people rule and the government obeys’ (Baschet 2019, 356). But this does not mean that the relationship between government — broken down into community, municipality, and zone — and people is strictly horizontal. On the contrary, it works both ways: ‘[…] the government obeys, because it has to consult and do what the people ask; the government commands because it has to implement and enforce what has been decided collectively […]’ (ibid, 360). Zapatista autonomy thus goes beyond the oppositions traditionally put forward between representative and direct democracy, and the analysis of the exchanges that exist within and between the three levels of Zapatista organisation are essential to understanding it.

Mariana Mora (Kuxlejal Politics, 2017) has carried out an ethnography of cultural and political practices in the Zapatista municipality Diecisiete de Novembre, based on materials collected between 2005 and 2008 through interviews, observations, and informal conversations (ibid, 5). Mora performed these investigations with the informed consent and review of the Zapatista assembly. She focuses on what she calls ‘everyday politics’ which she places at the centre of what Zapatista autonomy represents as a mode of socio-political organisation (ibid, 3–4):

‘The everyday politics of Zapatista indigenous autonomy simultaneously interacts with the state through what Pablo González (2011) terms a politics of refusal and enacts multilayered forms of engagement internal to the rebel autonomous project, including dialogue with vast webs of national and international political actors (…) From this double-pronged politics emerge particular Tseltal and Tojolabal cultural practices — concentrated in three central realms, knowledge production, ways of being, and the exercise of power — that partially unravel the colonial legacies of a racialized and gendered neoliberal Mexican state.’

This close analysis of the Zapatista ‘way of life’ touches on the theme of legitimacy in certain respects, but only indirectly. In other words, it is a valuable source of evidence of how self-governance can be socially constructed through the direct praxis involved in making that system work in people’s everyday lives. This approach does not need to rely on a formalised, academic approach to ‘participatory democracy’ that attempts to use political science to empirically measure variables involved in it, like confidence, legitimacy, or engagement. In short, the Zapatistas do not need to rely on bureaucrats, academics, or politicians to research, vote on, and administer their democracy for themselves.

While academics have broadly analysed how the Zapatista political system works, they have not done so through a lens of citizen competence. It is therefore necessary to ask what constitutes the legitimacy of ordinary citizens in such a system. How is the political competence of the communities of Chiapas — mostly peasants and Indigenous people — constructed? What is the relationship between ‘governed’ and ‘governing,’ between ‘political specialist’ and ‘layman’ in this case?

The Zapatista Rebellion in Chiapas

While the armed uprising of January 1, 1994, is generally identified as the beginning of the Zapatista movement as we know it today, it must be seen in the longer history of Indigenous and popular mobilisation in the country. That history goes back at least to the struggle of Emiliano Zapata during the Mexican Revolution of 1910 which aimed at restoring agricultural land to the local populations who had been managing it collectively since before Spanish colonisation. The predominantly agricultural state of Chiapas was plagued by poverty and inequality, and Indigenous people were highly marginalised and had no recognised rights. Peasant movements emerged in the 1970s in response to neoliberal immiseration, and it is out of that milieu that modern Zapatismo arose.

The EZLN (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional), the organisation that emerged as the main figure in the 1994 insurgency), was founded in 1983. It emerged from a Marxist-Leninist group in the north of the country, the FLN (Fuerzas de Liberación Nacional), and initially resorted to an isolated and clandestine guerrilla war. As Jérôme Baschet points out, ‘it is important to understand that Zapatismo was not born on 1 January 1994, and that there was a broad social movement behind and around it, with at least twenty years of struggle and experience accumulated by the Indigenous peasants of Chiapas.’ (2019, 19). The violence of the government and paramilitary organisations brought together the EZLN and Indigenous communities. The initial uprising, in which ‘for the first time in history, an indigenous army seized San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Ocosingo, Las Margaritas, and Altamirano […] with cries of “Ya basta!”’ (ibid, 33), carried the priority and central demand of the Zapatista movement: autonomy and the recognition of the rights of the Indigenous populations.

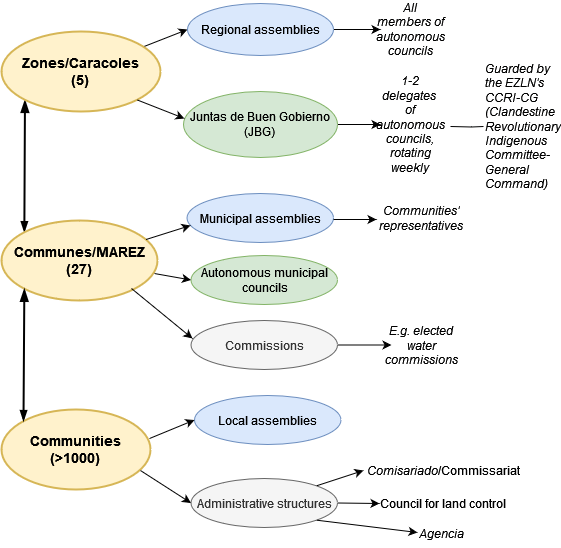

The initial phase of the uprising, from 1994 to 2003, was marked by a process of government repression, the transition from armed struggle to political struggle, and an attempt to negotiate with the Mexican authorities. The disillusionment of the Zapatistas with these negotiations led in August 2003 to the declaration of their autonomy in the seized territories, where they announced the unilateral application of the San Andrés Accords (providing for the constitutional recognition of Indigenous rights), which had not been respected by the Mexican government. They created ‘[…] five councils of good government, federating twenty-seven “autonomous Zapatista rebel municipalities” […]’ (Baschet 2021).

‘In Oventic the EZLN announced that the five Zapatista aguascalientes, regions created by the EZLN in January 1996, would be changed to caracoles and that five corresponding juntas de buen gobierno would be instituted as coordinating bodies for the multiple autonomous councils in the five Zapatista areas.’ (Mora 2017, 38)

According to Mora:

‘The San Andrés dialogues forged dynamic conditions for creative political endeavors at the margins of the state. Shortly thereafter, the Zapatista support bases, or community members who actively support the political-military structure of the EZLN but are not part of the rebel army’s military ranks, organized self governing bodies and administrative units to implement collective decisions and initiated their own education, justice, agrarian, and healthcare projects as part of their autonomous municipalities. Sympathizers of the movement also mobilized in support of these initiatives, myself included.’ (Mora 2017, 4)

A further expansion of autonomy was announced in August 2019 with the creation of four new autonomous municipalities and seven new ‘good government’ councils (Baschet 2021). Today, the Zapatistas have developed their own unique ideology not directly affiliated with any other, whether that be Marxism, Anarchism, or Maoism.

Autonomy as Participatory Democracy from Below

Today, participatory democracy refers to a wide variety of approaches in terms of formats, audiences, framing, and scale. It has its origins in criticism of representative democracy. In particular, these criticisms point to the dissociation between representatives and the represented, the excessive centralisation of power and the disempowerment of citizens, thus making ‘participatory democracy’ necessary (Hatzfeld 2011, 53). From then on, the development of participation was articulated around two distinct issues. If the aim was to make it a political tool available to leaders, it had to be able to correct and complement representation. With this in mind, governments sought to partially encourage the participation of actors traditionally excluded from the construction of public policies. But if it was to be a tool for challenging the political and social system, then participation had to be a political struggle. This last point makes it possible to understand participatory democracy as a means of producing a popular counter-power.

But, ‘[…] to think of participation only in terms of its mechanisms granted and designed according to the needs of public decision-makers is a dead end.’ (ibid, 27). Indeed, it is also possible to identify independent attempts that are taking place outside the state framework and that advocate new political practices based on participation, as the Zapatista experience of self-government shows. A self-governing political system is based on the idea of ‘[…] the capacity of all to govern themselves.’ (Baschet 2021, 11) All citizens therefore participate in policy-making and decision-making.

Self-management is a concept that is part of the tradition of the labour movement in which workers are encouraged to work autonomously for the establishment of socialism (ibid, 54). It is therefore a practice that aims at a radical transformation of society’s behaviours and ways of thinking: the relationship to work, consumption, and knowledge are then completely different, advocating an alternative organisational model to that of capitalism (ibid, 55).

The Zapatista movement is also characterised by this desire to effect a complete transformation of lifestyles. However, rather than talking about self-management, the Zapatistas use the term autonomy to characterise their modes of organisation:

‘Under this name of autonomy — by which the Zapatistas themselves synthesise their practice — one must understand both the implementation of modalities of self-government entirely dissociated from the institutions of the Mexican state and the reinvention of forms of life rooted in the Indigenous tradition and yet unprecedented, which escape as far as possible from capitalist determinations.’ (Baschet 2019, 323)

On the one hand, Zapatista autonomy thus represents a radical critique of the state, insofar as it rejects any form of political organisation that includes a centralisation of powers. Indeed, it implies a relocalisation of politics not only at the level of scale, with a shift from national to local, but also at the level of power hierarchies, with the state now absent (Baschet 2019). After the failure of the San Andrés Accords to recognise the rights of Indigenous peoples, autonomy appears to be a mode of organisation that can better respond to the needs of these populations (Melenotte 2010). The state is unable to do this unless it is completely transformed, reorganised, and abolished. The Zapatistas thus declared de facto autonomy for their territories in 2003 and have been self-governing ever since. More than a reflection of an inability to dialogue with the Mexican government, the declaration of autonomy is above all a form of resistance to state oppression.

‘They are afraid that we will discover that we can govern ourselves,’ said Maestra Eloisa at the Escuelita. She thus confirms the essential principle: we, the ordinary people, are capable of governing ourselves — a ‘discovery’ that has the unfortunate consequence, for those above and for all the self-proclaimed experts in politics, of demonstrating their harmful uselessness!’ (Baschet 2019, 372)

On the other hand, autonomy is also part of a long popular tradition of community organisation in which the collective exercise of power and consensus-building are essential: the authority of the community prevails over that of individuals (Baschet 2021). The ‘tradition’ is nevertheless undergoing transformations in power relations, through the integration of youth and women, who are usually excluded from community assemblies, as well as in the social structure and symbolic roles associated with women (Mora 2017). Women, for instance, were made an early priority in the Zapatista revolution and were fully included in autonomy arrangements.As identified by Jérôme Baschet in 2021, Zapatista autonomy is being implemented in the fields of education, health, justice and politics. It cuts across several facets of daily life, in a process of struggle for lekil kuxlejal, a dignified collective life associated with a specific territory (Mora 2017, 12). It represents a daily aspiration to live with dignity and is therefore expressed through everyday practices (ibid). The relationship to the land is essential in that it allows for the creation of a collective identity territorialised around autonomy, without the need for legal structures for its implementation (Guimont Marceau 2010). By living their ideas out in practice, the Zapatistas demonstrate how stateless participatory democracy is about much more than a change in political institutions: it is fundamentally rooted in a transformation of social relations and everyday life. It is, in a word, revolutionary.

Part Two

This is part two of an essay on Zapatista autonomy that I wrote with a friend and fellow student, which we both wanted to translate into English. In part one, we went over some of the basic history of the Zapatista rebellion, and started exploring the meaning of autonomy. In this post, we argue that their federal and non-dissociative political system, as well as their shared principle of “mandar obedeciendo”, have made a full despecialisation of politics possible.

The political organisation of Zapatista autonomy

The Zapatista political structure is a federal system with three interacting levels: the communities; the communes (or MAREZ), which bring several communities together; and the Caracoles, for the coordination of communes at a regional level. Each level has assemblies and authorities elected for two or three years. The link between these two elements is essential to the functioning of autonomy. For example, decisions can only be taken in consultation with every other assembly/authority level: in fact, there are regularly multiple back-and-forths between the municipal council, the regional assembly, and the communities (Baschet 2021).

Other elements also intervene in the functioning of autonomy, such as the Supervisory Commission of each Zone, or the CCRI, i.e. the EZLN’s Clandestine Indigenous Revolutionary Committee (Baschet 2019). The decentralisation of political organisation and the involvement of ordinary people avoid certain problems inherent to the State and representation, such as the separation between the governors and the governed. The latter leads to the implementation of policies that do not necessarily meet the expectations of the citizens, but only the interests of those in power. In an autonomous system, on the other hand, everyone is able to govern themselves without the State. Therefore, members of the Zapatista community can provide a mandate to others to carry out political tasks, but that direct mandate is essential. There is no self-proclamation, no self-representation in elections, and no political specialists. Zapatista women and men are themselves involved in policymaking, which allows them to respond directly to the interests of their community.

Zapatista autonomy is thus a project of community participation that includes internal participation of citizens in the life of their community, but also external participation of the community in a broader political order (Dumoulin 2010). The Zapatistas interact with the Mexican State through a politics of refusal, and implement forms of engagement at several levels, including a dialogue with national and international political actors (Mora 2017). Here, therefore, participation is not reduced to a political tool that the government uses in the hope of renewing the legitimacy of the existing system. It aims to challenge the mode of political organisation and above all the social order that structures roles and hierarchical positions in all spheres of life, including political activity. Indeed, since the declaration of autonomy, the place of women in politics, but also in Zapatista society, has been positively transformed.

Moreover, autonomy is a constantly evolving process; it is a practice that has the capacity to adapt to social reality (Baschet 2019). It is not a system fixed by theoretical principles that must absolutely be applied to the letter. On the contrary, it is a policy situated in a concrete place, composed of concrete experiences, which must be able to adapt to the context it encounters. This conception opens up the possibility of applying autonomy worldwide (ibid).

‘In this sense, the political logic of autonomy is the same as the desire to build a world where there is room for many worlds: not only does it start from the singularity of experiences, but it invites us to recognise that there cannot be a single way of thinking about the exit from capitalism. It therefore calls for the recognition of the multiplicity of worlds, but also for the art of listening, translation and proportionality, so that these worlds are able to coordinate, learn from each other and master their possible divergences. (Baschet 2019, 378)’

According to the Zapatistas, in order to truly realise democracy in the radical sense of popular self-determination, power must be grounded at the grassroots level. That is, society — as opposed to the State, government, or any power-seeking parties and organisations — must be able to control and sanction those in leadership positions, as well as make them respond to popular interests (Chapdelaine 2010). This is what the movement strives to achieve through the politics of autonomy, which allows for the effective participation of all through the idea that the people are capable of organising and governing themselves.

The issue of political competence

From a sociological point of view, political competence is not defined as whether someone is able or unable to take part in politics, because the very idea of competence or legitimacy is socially constructed. In other words, analysing political competence implies identifying the process of social recognition of certain competences, namely whatever is considered necessary to take part in politics. We take up here the conception formulated (among others) by Bourdieu (1979, 465–466), who defines political competence as:

‘…the greater or lesser capacity to recognise the political question as political and to treat it as such by responding to it politically, i.e. on the basis of properly political (and not ethical, for example) principles, a capacity which is inseparable from a greater or lesser feeling of being competent in the full sense of the word, i.e. socially recognised as being entitled to deal with political affairs, to give one’s opinion on them or even to change their course.’

From this perspective, the social division of political activity is based on an unequal distribution of these socially-constructed competences, so that the degree of participation and politicisation of individuals is related to their position within the social structure. Their individual socioeconomic characteristics — in particular social class and (formal) level of education — are hence decisive in terms of their chance to acquire these competences, and thus become socially recognised as more ‘legitimate’ for formulating political opinions and intervening in the decisions or construction of public policies.

In the context not only of electoral or parliamentary politics, but also experiments of participatory democracy, proficiency in the ‘language and schemas of politics’ (Lagroye et al. 2012, 351) thus reinforces the participation of members of the middle and upper classes, whose socialisation and formal education led them to internalise the norms, rhetoric, and intellectual references of bourgeois culture. Conversely, the ‘incompetence’ of socially dominated individuals and groups — again, in terms of bourgeois norms, rather than objective inability — manifests itself through their ‘non-participation in “civic” activities’ (p. 348) within the bourgeois public sphere. This highlighting of inequalities in politicisation is therefore a possible way of explaining the low participation of workers and poor people in experiments in participatory democracy.

The particularly interesting dimension of the Zapatista experience is, in this respect, the absence of a specialisation (or professionalisation) of political activities and expertise (in the sense of technical competence). As Lascoumes (2002, 377) explains,

‘We can consider that the future of expert practices is linked to their capacity to become more democratic, i.e. to truly open up their approach to contrasting points of view and, in particular, to organise a plural expertise that does not stop at the networks of specialists alone and knows how to make a real place for lay people.’

However, the Zapatistas seem to emphasise the despecialisation of political tasks and public functions. According to Baschet (2019, 362–363),

‘The Zapatista experience allows us to insist on the following points: short, non-renewable mandates that can be revoked at any time; the absence of personalization and the collegial exercise of responsibilities; control by other bodies; limited concentration of a capacity to elaborate decisions that remains largely shared with the assemblies; the ethics of the collective and the capacity to listen. Above all, however, it is necessary to insist on the effective despecialisation of political tasks which, instead of being monopolised by a specific group (political class, caste based on money, personalities with particular prestige, etc.), are the object of a circulation that is as generalised as possible: ‘We must all, in our turn, be government’ (maestro Jacobo). As has been said, this implies, among other things, abandoning the idea of linking the choice of delegates to the evaluation of a particular individual competence: assuming that elected authorities do not know more about public affairs than others is the condition — oh so difficult to accept! — of a full despecialisation of politics.’

It is important then, as already mentioned above, not to conceive of the Zapatista mode of organisation as a form of complete or pure horizontalism. According to Baschet, the Zapatistas practise a ‘non-dissociative’ form or modality of delegation, as opposed to configurations of delegation based on a dissociation between the rulers and the ruled. This dissociation characterises, according to him, ‘political representation in the modern state,’ corresponding to ‘the methodical organisation of the effective absence of the represented’ (ibid, 362). He concludes that it is necessary to emphasise the sensitive balance represented by the Zapatista system, between ‘verticality of command’ and ‘horizontality of consensus’ (ibid, 74):

‘It is not a question, therefore, of a real power-over that one part of the collective manages to monopolise and exercise over others, nor is it a question of perfect horizontality, which runs the risk of dissolving for lack of initiatives or the capacity to put them into practice. Rather, the observation of the Zapatista experience invites us to recognise the articulation of two principles: on the one hand, the capacity to decide resides essentially in the assemblies, at their different levels; on the other hand, those who assume, in a rotational and revocable manner, a special role of initiative and impetus, as a mediation between the collectivity and its capacity for self-government, which does not go without opening up the twofold risk of a deficiency or excess in the exercise of this role. (ibid, 361)’

This potential risk, due to the existence of positions of authority/leadership, is however limited within Zapatista autonomy by a remarkable sense of collective responsibility: a community ethos of reciprocity, as documented for instance by Mora (2017) in her ethnography of the municipality Diecisiete de Noviembre. More concretely, it is a set of principles contained in the general phrase mandar obedeciendo (‘governing by obeying’). This general political principle, formulated at the outset of the Zapatista rebellion (Chapdelaine 2010, 41), seems to derive from older Indigenous cultural practices in the Tseltal and Tojolabal communities (Mora 2017: 191).

In its most concrete sense, mandar obedeciendo implies that those in authority are accountable to the people and organise what the people have decided in a general assembly: ‘the authorities are responsible for implementing those decisions reached by consensus in the assemblies, rather than taking decisions in the name of the people’ (Mora 2017, p. 191). This is similar to the longstanding principle of imperative mandate that has characterised a range of revolutionary movements or episodes since the 19th century. For instance, in the Paris Commune of 1871, not only representatives, but also people assigned to various public functions (e.g. magistrates and judges), derived their roles from such revocable mandates.

According to Chapdelaine (2010), mandar obedeciendo allows ‘to overcome the professionalisation of politics, which has led to a systematic separation between the governors and the governed and to the loss of meaning of the forms of government.’ (ibid, 41). As Mora brilliantly demonstrates (see chap. 5 of her book), political competence is thus constructed, in the everyday social interactions and cultural practices of the Zapatistas, as explicitly resting on non-specialisation:

‘Of the members of the councils of good government, the Zapatistas have been able to say: “They are specialists in nothing, least of all in politics” (SDR). This non-specialisation leads to the admission that the exercise of authority is carried out from a position of non-knowledge. The members of the autonomous councils insist a lot on the initial feeling of being helpless in front of the task that falls to them (‘nobody is an expert in politics and we all have to learn’). But it is immediately emphasised that it is precisely by accepting not knowing that one can be a ‘good authority’, who tries to listen and learn from everyone, who knows how to recognise mistakes and accepts to be guided by the community in making decisions (GA1). In the Zapatista experience, entrusting the tasks of government to those who have no particular capacity to carry them out is the concrete ground from which the mandar obedeciendo can grow; and this is a solid defence against the risk of separation between governors and governed. (Mora 2017, 359)’

It is in this sense that we can understand her assertion that the principle of mandar obedeciendo inverts ‘the logic of command-obedience that we find in classical Westernised political theory’ (ibid, 192). She goes further than other authors by arguing that it is also necessary to look beyond the framework of assemblies to observe ‘how mandar obedeciendo forms part of the politicisation of social life in diverse daily spheres’ (ibid, 228). In her ethnography, she describes, for example, the politicised conversations she observed within the women’s production collectives of Diecisiete de Noviembre. The mandar obedeciendo, in this sense, is (also) related/equivalent to a political and cultural practice that the author calls ‘Kuxlejal politics’ (ibid, 19):

‘When I asked Mauricio what the Tseltal word for “life” is, he explained that its rough equivalent is kuxlejal, “life-existence.” Kuxlejal as a term is but a mere point of anchor granted meaning when used as part of the term for the concept of expressing living as a collective, stalel jkuxlejaltik, a way of being in the world as a people, and as part of the term for a daily aspiration to live in a dignified manner, lekil kuxlejal. The horizon of struggle for lekil kuxlejal, with its Tojolabal equivalent, sak’aniltik, as a good way of living refers not only to an individual being but to that being in relation to a communal connection to the earth, to the natural and supernatural world that envelops as well as nurtures social beings and is thus constantly honoured. Without land, without the ability to plant and harvest sufficient food, without the constant remembering of ancestors in connection to the future and as part of revering the earth, the elements that provide sustenant meaning to life dissipate.

When Zapatista community members associate the political practices of autonomy with creating a new life, they refer to lekil kuxlejal, to a life politics understood as involving these interconnected realms. Autonomy as the foundation of life politics thus is expressed in gathering fallen branches for firewood, in harvesting corn in the fields, in praying for abundant water-not too much, nor too little, just what is necessary for the corn and beans to flourish in the fields, in collecting edible leaves in the forest or picking vegetables in the backyard gardens, in taking care of the children and the elderly, in sharing memories of past events so as to produce knowledge effecting changes in the present. It is the sum of activities in such arenas that allows for the dignified reproduction of life, not only as a physical presence but as a series of cultural processes that allow for the perpetuation of kuxlejal in its collective form and as a collective force.’

Conclusion

In summary, for the Zapatistas ‘democracy is something that is built from below and with everyone’ (Chapdelaine 2010, 46). Their revolutionary autonomy has allowed for the total reorganisation of politics and society in parts of Chiapas, directly involving Mexico’s indigenous populations in the construction and implementation of policies and decisions that affect them directly.

The contrast between the respective contexts of the predominantly Indigenous and rural communities of Chiapas and that of the experiments of participatory democracy in (especially more urban) spaces in Europe should not prevent us from reflecting on the issues that run through all these forms of participation. While it is clear that the Zapatista experience is not as such transferable or strictly comparable to other contexts, its radical form of democracy ‘from below’ helps identify the potential limits or obstacles of so-called “participatory democracy” in other contexts. The non-separation between politics and the rest of society, and especially between the governors and the governed, seems to be one of the main aspects that distinguishes it from most other cases.

Among the Zapatistas, the construction of competence and legitimacy to participate lies, in our opinion, in a collective will — inscribed in the struggle for self-determination of the Indigenous populations in Chiapas — to achieve a form of communal democracy based on the non-specialisation of activities and responsibilities, as well as on the defence of one’s own way of life. Baschet (2021) suggests that the core of these Zapatista forms of life lies in the three words: community, land, and territory.

Note: this two-part article was written in the spirit of an open and ongoing discussion about the Zapatista revolution, thus the author invites any feedback or further dialogue about the claims/arguments presented here (including potential criticisms or corrections) and more generally about the Zapatista experience and what we can learn from it.