Eric Fleischmann

A History of Timebanking

The roots of timebanking can be found in what early economists of the late 1700s like Adam Smith and David Ricardo described as the “Labor Theory of Value” (LTV); which proposes that all commodities produced in a market system originate their value in human labor. As Ricardo writes:

In speaking then of commodities, of their exchangeable value, and of the laws which regulate their relative prices, we mean always such commodities only as can be increased in quantity by the exertion of human industry, and on the production of which competition operates without restraint.[1]

Born in the context of proto-industrial capitalism as an attempt to explicitly conceptualize the basic rules of the proto-global economy in the de-marcantilizing nations of Europe, socialists of various stripes would use this empirical axiom as an ethical basis for why workers are “entitled to all they create” (a common saying in militant labor circles). In this sense the LTV becomes a means to resist the logic of the factory—wherein workers create for the profit of bosses and owners and only receive back a fraction of the value they create—and as such it is no surprise that, beyond Marxian economics, the theory has been abandoned by most mainstream economists in favor of the “subjective theory of value.”[2] However, within many radical movements, time-based currencies became an application of the LTV to not just to production but to exchange; x hours of labor for x hours of labor.

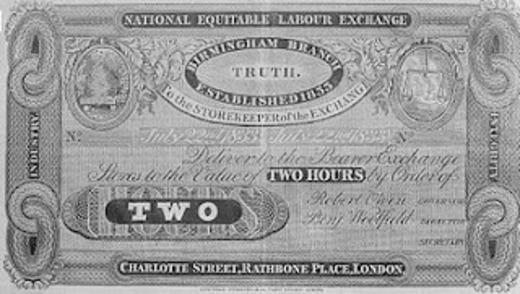

On this basis, the English-born Robert Owen—an early 19th century industrialist and a founder of the modern cooperative movement—worked for decades establishing and expanding trade unions, cooperatives, and intentional communities in North America and, in many ways set a precedent for socialists after Ricardo, held firmly to the LTV; believing, according to Edward J. Martin, that “workers ought to be compensated based on both human needs and effort.” After numerous failed attempts at “pure” communism—i.e. no property and no currency etc.—in many intentional communities throughout the 1820s, Owen—then entrenched in establishing trade unions and cooperative enterprises back in England—would advocate for the “development of labor exchanges where workmen and producers’ cooperatives could exchange products directly and thus dispense with both employers and merchants.” In 1832, he founded the “National Equitable Labor Exchange” which “sought to secure a wider market for cooperative groups and to enable them to exchange their products at an equitable valuation resting on labor time” through printed labor vouchers. This would lead to similar exchanges emerging in several other provincial cities.[3]

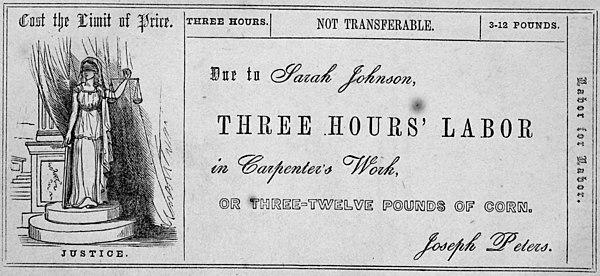

[4]The Bostonian anarchist Josiah Warren participated in several communistic Owenite communities in the United States and also left with the belief that a means of market exchange based on the LTV was a key part of a liberatory economic project. Based on that idea, in 1827 Warren would establish his “Time Store” in Cincinnati, Ohio, wherein, according to William Bailie in his 1906 book on Warren, compensation was “determined on the principle of the equal exchange of labor, measured by the time occupied, and exchanged hour for hour with other kinds of labor.”[5] The Time Store was apparently very successful—even resulting in several other stores coming to accept the labor-time vouchers alongside standard U.S. currency. After two years, Warren left the store to a friend and traveled throughout the midwest; helping establish time stores and entire communities based on the principles of the LTV and equitable exchange. He, like Owen before him, hoped that these efforts would birth a socialist society not based on governmental control but voluntary, cooperative production and exchange by producers. However both Owen’s exchanges in England and Warren’s many stores and “Equity Villages” in the U.S. had collapsed or faded away as the turn of the century neared, unable to match the competitive advantages of 19th century industrial capitalism.[6]

[7]After Warren’s death in 1874, time-based currencies fell to the wayside among anarchists in his vein (like Benjamin Tucker and William B. Greene) in favor of a focus on credit. Greene would go as far as to argue that it is the current “confused” organization of credit and its emergence from the “insufficiency of circulating medium which results from laws making specie the sole legal tender” that leads most immediately to “want of confidence, bad debts, expensive accommodation-loans, law-suits, insolvency, bankruptcy, separation of classes, hostility, hunger, extravagance, distress, riots, civil war, and, finally, revolution.”[8] As a result, these anarchists began to advocate for mutual credit through free banking, an open-ended system wherein, as members of the Voluntary Cooperation Movement (a contemporary anarchist group) outline,

[a]ny group of private individuals could cooperate to form a mutual bank, which would issue monetized credit in the form of private banknotes, against any form of marketable collateral the membership was willing to accept. Membership in the bank and receipt of credit were conditioned on willingness to accept the notes as tender.[9]

In fact, by the 1930s, anarchist writer Laurance Labadie—described by Herbert C. Roseman as the “heir of Warren”—would explicitly reject the idea of making “labor-time a standard for a monetary unit” as “a fallacy and bound to fail in practice” in favor of a free banking strategy.[10][11]

Looking back again a few decades, Marx, a year after Warren’s death, had in turn proposed that, at least in a transitional phase phase between capitalism and socialism, labor vouchers would function as such:

[T]he individual labor time of the individual producer is the part of the social working day contributed by him, his share in it. He receives a certificate from society that he has furnished such-and-such an amount of labor (after deducting his labor for the common funds), and with this certificate he draws from the social stock of means of consumption as much as the same amount of labor costs. The same amount of labor which he has given to society in one form he receives back in another.[12]

Marx would go on to seemingly abandon this idea and later critique Owen’s labor exchange in the footnotes of Capital Vol. 1, but the core idea would inspire heterodox Marxists for the next two centuries.[13] For example, 20th century Marxist-influenced autonomist Cornelius Castoriadis advocated for a similar structure wherein “[p]eople will receive a token [revenu] in return for what they put into society . . . allowing people to organize what they take out of society, spreading it out (1) in time, and (2) between different objects and services, exactly as they wish.”[14] Then in the 90s, Marxian economists Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell embraced the computer age in advocating for a socialist system wherein “some form of labour credit card . . . keeps track of how much work you have done” which can then be used to acquire goods from communal stores.[15]

This mirrors the kind of economics proposed within Marx’s lifetime by the anarchists of the Jura Federation—which Marx had worked hard to expel from the International Workingmen’s Association. Mikhail Bakunin and his associates, according to his friend James Guillaume in 1876, proposed that confederated communes would each establish their own “Banks of Exchange.” Then

[t]he workers’ association, as well as the individual producers (in the remaining privately owned portions of production), will deposit their unconsumed commodities in the facilities provided by the Bank of Exchange, the value of the commodities having been established in advance by a contractual agreement between the regional cooperative federations and the various communes, who will also furnish statistics to the Banks of Exchange. The Bank of Exchange will remit to the producers negotiable vouchers representing the value of their products; these vouchers will be accepted throughout the territory included in the federation of communes.[16]

Like the Marxist formulations above, it is somewhat vague if the vouchers in the Bakunist scheme are based solely on labor-time or other factors like type of work and intensity, but regardless, later communist and collectivist anarchists largely abandoned the idea of labor vouchers in favor gift economies or, as in the case of anarchists during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) according to Percy Hill, “money was abolished in Aragon, [but] no one system predominated to replace it, instead the various towns organised broadly under the principle of ‘free consumption.’”[17]

Around that same time in the United States, the Great Depression led to the emergence of literally countless local currencies (called scrips) in the face of the extremely devalued American dollar and lack of work opportunities.[18] It has been suggested by some (including one of my interviewees) that some of these scrips were time-based, but little information is available. Beyond this and some discussion of Warren’s experiments in obscure periodicals, the first contemporary timebank would not appear until it was founded in 1973 by Teruko Mizushima in Japan to give greater valuation to the work of housewives in particular. At almost the exact same time as [Sylvia] Federici and other autonomist and socialist feminists were campaigning for the productive/reproductive work of women in the household to be acknowledged and compensated, Mizushima was, according to Jill Miller, “recruiting housewives who, she believed, suffered from inadequate recognition of their abilities” into her “new currency to create a more caring society, through increasing the exchange of mutual assistance in the community, and to value everyday tasks, such as those of housewives and carers, which the wage system did not reward.” Of particular importance to this sorority was the care of elders, many of whom had served in the Pacific Theater of World War II and “were hospitalised or unable to look after themselves or their homes.”[19]

A few years after Mizushima’s project began, [Edgar S.] Cahn began promoting “time dollars” (known regionally sometimes as “time credits” or, especially at Hour Exchange Portland, “Hours”) in the United States. For Cahn, there are

at least three interlocking sets of problems: growing inequality in access by those at the bottom to the most basic goods and services; increasing social problems stemming from the need to rebuild family, neighborhood and community; and a growing disillusion with public programs designed to address these problems.[20]

The solution he proposed was, of course, timebanking; a scheme whereby neighbors could exchange labor with each other; x hours for x hours. One of the first communities to adopt this program was Grace Hill Settlement House, a mutual aid program founded in 1903 focused on helping immigrants in St. Louis neighborhoods. By the 1980s, it had become a more general social service provider and established their Member Organized Resource Exchange (MORE). This included community computer stations, the “Neighborhood College,” and more, but, as The Annie E. Casey Foundation argues, the “centerpiece of the MORE system is its Time Dollar Exchange,” which not only allowed for members to exchange services but “[a]t Grace Hill, Time Dollars also can be used at Time Dollar Stores, which offer donated goods such as food, toiletries, clothing, and furniture.”[21] Not only was this a practical success but, according to Stephen Beckett (who will be discussed momentarily), several of the women involved in Grace Hill helped lay out the first four “values of timebanking:” “1) Everyone is an Asset, 2) Redefining Work, 3) Reciprocity, and 4) Social Networks or Social Capita.l”[22] Then, with the addition of “5) Respect,” Cahn would go on to campaign for time dollars across the world, and, thanks to him and co-current projects like Ithaca HOURS in New York state, hundreds of timebanks now exist all across the world.[23][24]

A History of Hour Exchange Portland

The history of Hour Exchange Portland (“Hour Exchange” or, formerly, “HEP”) begins with Cahn and his campaign to popularize timebanking.[25] Their website states that “[i]n late 1995 Dr. Richard Rockefeller (the founder of Hour Exchange Portland) first heard Dr. Edgar Cahn speak” and

realized that we can’t expect people to take care of our environment, if we are not first taking care of each other. Compelled to bring the Time Dollar concept to Maine, Richard began to share his vision. In 1997 Maine hosted an International Time Dollar Congress in cooperation with Dr. Edgar Cahn . . . bringing together 40 Service Exchanges from all over the world. For many, it was the first opportunity to share their experiences about their programs and learn from others. For the Portland community, the Congress inspired a new vision and direction. It was time to grow a local Service Exchange, and the seed that became today’s Hour Exchange Portland was born.[26]

That seed would sprout into the 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization “Maine Time Dollar Network,” and originally it was one of an ecosystem of active timebanks in the various cities, towns, and counties of Maine. Over the years many of these have collapsed or been absorbed by other banks and new ones have sprung up again and again, but through it all the renamed “Hour Exchange Portland” persists.

Lucy [pseudonym] elaborated in length on the history of Hour Exchange and emphasized to me the important role that Rockefeller played both in its inception and ongoing maintenance. One of the heirs to his family’s fortune, Rockefeller utilized his resources (alongside numerous grants and an AmeriCorps VISTA contract) to support the timebank for nearly a decade. This funding allowed the timebank to initially employ multiple full-time and part-time paid administrative positions. One of the many documents Hour Exchange provided for this research included the following information:

Hour Exchange Portland’s annual expenses from 2007 through 2010 averaged around $300,000. Salary and benefit expenses for the paid employees comprised about 75%-80% of the budget in any given year. In 2011, the organization reduced its budget considerably by employing only one full-time staff person. Beginning in 2013 Hour Exchange Portland employed only part-time office assistance.

Throughout this time period (2007-2013), Rockefeller also, according to Lucy, “tried to encourage Hour Exchange to be more self-sufficient” by “providing less and less support over the years.” Though reorganization to account for this had started around 2011, this self-sufficiency was put to the test when Rockefeller died unexpectedly in 2014. From then onward, Hour Exchange has been “member run” in that its perpetuation is solely the responsibility of the board and general membership without any consistent paid staff.

Since its founding, Hour Exchange had largely functioned without printed “time dollars” and rather through written records and then basic spreadsheets introduced by Kent Gordon, but in 2006, Hour Exchange members Stephen V. Beckett, Terry Daniels, Linda Hogan, and, later, John Saare saw that “everything was getting on the Internet,” and started the hOurworld cooperative, through which they developed the software Time and Talents. I spoke to Stephen via video call in the early spring and he explained to me that previously, the Hour Exchange system was only partially digital for administrative purposes, with “first just a single computer, then a local area network, then a local area network with part of the database online.” Much of what was elaborated upon in Time and Talent after finishing the basic software elements was ways that these two databases, one local and one online, could be synced up. Other software for timebanking had existed before Stephen’s project such as Timekeeper and, more popularly, Community Weaver v1-3 (developed by Mark McDonough and Cahn’s organization Timebanks USA) but both had major bugs and ease of use issues, and additionally the latter required fees from member timebanks—in contrast to Time and Talents which is free to this day and funded primarily by contracts for specialized versions of the software. This matter of fees in particular brought on, as Paul Weaver writes, further disagreements “over the ownership and development of the software (open source versus proprietary), over data (who own the data, who has access to data, who has control and rights over information generated from data, etc.), over decision making, etc.”[27]

This tension between which software timebanks should use and, more fundamentally, over who would lead the western timebanking movement eventually led to a split between advocates of time dollars; with Hour Exchange Portland at the heart of it, both because of Stephen’s membership thereof and Rockefeller’s adamant opposition to fees. On the one hand, many timebanks stayed with the Community Weaver software and its reliable association with Cahn’s work, but numerous others switched to Time and Talents for its accessibility and affordability.[28] Today, Time and Talents helps coordinate and catalog exchanges in and between 388 timebanks, including its birthplace Hour Exchange Portland, across the planet and allows for anyone to set up a timebank with only a small group of people and a click of a button. However, the Covid-19 Pandemic in the 2020s did substantial damage to these timebanks and the activeness of their memberships. Such was the case of Hour Exchange Portland in particular, Lucy explained to me that she saw “a lot of people didn’t feel comfortable doing face-to-face exchanges, so the number of exchanges dropped precipitously.” She also emphasized to me that much of what kept the bank’s momentum was in-person community events like potlucks and the annual Bizarre Bazaar, where members gather to exchange crafts, second-hand items, and more with time dollars. Dorothy [pseudonym] added that many of the relationships Hour Exchange had with artistic institutions like Meryl Auditorium, Portland Stage, and various art exhibits pre-pandemic have lapsed, removing that incentive as well. And while it is in the process of recovering, it is in the context of the “pandemic aftermath” that I am doing my research on timebanking and its intersections with eldercare.

[1] David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (London, UK: John Murray, 1817), 15, Epub.

[2] Robert P. Murphy, “The Labor Theory of Value: a Critique of Carson’s Studies in Mutualist Political Economy,” Journal of Libertarian Studies 20, no. 1 (Winter 2006), accessed April 21, 2023, https://cdn.mises.org/20_1_3.pdf.

[3] Edward J. Martin, “The Origins of Democratic Socialism: Robert Owen and Worker Cooperatives,” Dissident Voice, last modified December 6, 2019, accessed April 14, 2023, https://dissidentvoice.org/2019/12/the-origins-of-democratic-socialism-robert-owen-and-worker-cooperatives/.

[4] Socialist Party of Great Britain, “Labour Time Vouchers,” Socialism or Your Money Back, last modified November 30, 2016, accessed April 14, 2023, https://socialismoryourmoneyback.blogspot.com/2016/11/labour-time-vouchers.html.

[5] William Bailie, Josiah Warren, the First American Anarchist: A Sociological Study(Boston, MA: Small, Maynard and Company, 1906), 9, accessed April 15, 2023, https://archive.org/details/josiahwarrenfirs00bailiala/page/n5/mode/2up.

[6] Steve Kemple, “The Cincinnati Time Store As An Historical Precedent For Societal Change” (Presented at CS13 Creative Economy exhibition, Cincinnati, OH, March 19, 2010), 5, 9, https://www.scribd.com/document/32919811/The-Cincinnati-Time-Store-As-An-Historical-Precedent-For-Societal-Change.

[7] “Cincinnati Time Store,” Wikipedia, accessed April 15, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cincinnati_Time_Store.

[8] William Batchelder Greene, The Radical Deficiency of the Existing Circulating Medium: And the Advantages of a Mutual Currency (Boston, MA: B.H. Greene, 1857), 238-39, accessed April 15, 2023, https://books.google.com/books?id=RBkqAQAAIAAJ&source=gbs_book_other_versions.

[9] Voluntary Cooperation Movement, “A Mutualist FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions About Mutualism,” Anarchist Library, accessed April 15, 2023, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/mutualists-org-a-mutualist-faq.

[10] Herbert C. Roseman, “Laurance Labadie and His Critics” (1967), Union of Egoists, last modified April 1, 2018, accessed April 15, 2023, https://www.unionofegoists.com/2018/04/01/laurance-labadie-and-his-critics-by-herbert-c-roseman/.

[11] Laurance Labadie, “Letter to Mother Earth” (1933), The Anarchist Library, last modified 1 17, 2022, accessed April 15, 2023, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/laurance-labadie-letter-to-mother-earth.

[12] Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program, Foundations 16 (Paris, France: Foreign Language Press, 2021), 14, accessed April 15, 2023, https://foreignlanguages.press/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/C16-Critique-of-the-Gotha-Program-1st-Printing.pdf.

[13] Karl Marx, Capital: A Critical Analysis of Capitalist Production, ed. Frederick Engels, trans. Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling (Moscow, USSR: Progress Publishers, 1974), 1:97-8, accessed April 20, 2023, http://www.marx2mao.com/PDFs/Capital,%201.pdf.

[14] Cornelius Castoriadis, “On the Content of Socialism, II,” 1957, in Political and Social Writings Volume 2, 1955-1960: From the Workers’ Struggle Against Bureaucracy to Revolution in the Age of Modern Capitalism, trans. David Ames Curtis, vol. 2, Political and Social Writings(Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, n.d.), 2:125, accessed April 15, 2023, https://files.libcom.org/files/cc_psw_v2.pdf.

[15] Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell, Towards a New Socialism (Nottingham, UK: Spokesman Books, 1993), 25, accessed April 15, 2023, https://users.wfu.edu/cottrell/socialism_book/new_socialism.pdf.

[16] James Guillaume, “On Building the New Social Order,” in Bakunin on Anarchy: Selected Works by the Activist-Founder of World Anarchism, by Mikhail Bakunin and James Guillaume, ed. Sam Dolgoff (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), 222, PDF.

[17] Percy Hill, “Anarchist Communist Political Economy and the Spanish Revolution,” Red and Black Notes, last modified September 13, 2020, accessed April 15, 2023, https://www.redblacknotes.com/2020/09/13/anarchist-communist-political-economy-and-the-spanish-revolution/.

[18] Loren Gatch, “Local Money in the United States During the Great Depression,” Essays in Economic & Business History XXVI (2008), accessed April 15, 2023, https://scriplibraryhome.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/local-money.pdf.

[19] Jill Miller, “Teruko Mizushima: Pioneer Trader in Time as a Currency,” Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, last modified July 2008, accessed April 15, 2023, http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue17/miller.htm.

[20] Edgar S. Cahn, “Time dollars, work and community: from `why?’ to `why not?,'” Futures 31, no. 5 (1999): 499, accessed April 15, 2023, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016328799000099.

[21] Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Grace Hill’s MORE: Neighbors Helping Neighbors,” hOurworld.org, last modified February 2008, accessed April 16, 2023, https://hourworld.org/pdf/Grace_Hill_MORE_Study.pdf.

[22] [Edgar S. Cahn, No More Throw-Away People: The Co-Production Imperative (Washington, DC: Essential Books, 2000), 24.]

[23] “Goals & Core Values,” Waikato TimeBank, accessed April 20, 2023, https://waikato.timebanks.org/page/683-goals–core-values.

[24] “Ithaca HOURS: Community Currency since 1991,” paulglover.org, accessed April 16, 2023, https://www.paulglover.org/hours.html.

[25] Hour Exchange used to employ the abbreviation “HEP” until it was brought to the previous board’s attention that it resembled the “hep hep” rallying cry of antisemitic rioters in early 19th century Germany.

[26] “Mission,” Hour Exchange Portland, accessed April 16, 2023, https://hourxport.org/mission.htm.

[27] Paul Weaver, “Software development and arising governance tensions,” Transformative Social Innovation Theory, last modified 2017, accessed April 20, 2023, http://www.transitsocialinnovation.eu/sii/ctp/tb-usa-5.

[28] Ibid.